Waking Up Silent Code: Modern Methods for Activating Cryptic Prokaryotic Gene Clusters in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary strategies for activating cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in prokaryotes, with a focus on applications in natural product discovery and drug development.

Waking Up Silent Code: Modern Methods for Activating Cryptic Prokaryotic Gene Clusters in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary strategies for activating cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in prokaryotes, with a focus on applications in natural product discovery and drug development. It covers the foundational principles of genome mining, details a suite of genetic, chemical, and synthetic biology methods for cluster activation, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and outlines validation and comparative frameworks for evaluating success. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes the latest advances—including CRISPR-based tools like ACTIMOT and ribosome engineering—to equip the scientific community with practical knowledge for unlocking the vast hidden biosynthetic potential of bacteria.

The Hidden Treasure: Understanding Cryptic Gene Clusters and Their Potential

Defining Cryptic Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) in Prokaryotes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between 'cryptic' and 'silent' BGCs? The terms are often used interchangeably, but a precise definition is crucial for clear scientific communication. A silent biosynthetic gene cluster refers specifically to a BGC that is not expressed under standard laboratory conditions [1]. In contrast, a cryptic biosynthetic gene cluster describes a BGC for which the encoded natural product is hidden or unknown [1]. This can occur in two main scenarios: either a natural product has been observed but its cognate BGC has not been identified, or a BGC has been expressed but its predicted product cannot be detected under laboratory conditions [1].

2. Why is activating cryptic BGCs important for drug discovery? Microbial natural products underpin the majority of clinically used antibiotics [1]. Genome sequencing has revealed that prolific producers, like filamentous actinobacteria, typically harbor 20 to 50 natural product BGCs, but express very few under standard lab conditions [1] [2]. This vast reservoir of unexpressed biochemical diversity represents a promising source for novel therapeutic leads, potentially ushering in a new era of antibiotic discovery to combat antimicrobial resistance [1] [3].

3. What are the first experimental steps when a cryptic BGC is identified bioinformatically? After identifying a BGC of interest, the initial step is often to attempt to induce its expression in the native host. A common and straightforward first approach is to manipulate culture conditions (the OSMAC approach), which can include varying media composition, aeration, or the addition of chemical elicitors [4] [5]. Simultaneously, you should analyze the BGC's genetic structure for pathway-specific regulators that can be genetically manipulated, such as by promoter replacement [4].

4. When should I consider heterologous expression for a cryptic BGC? Heterologous expression is a powerful strategy when the native producer is difficult to cultivate genetically, when specific activation in the native host fails, or when you need to simplify the genetic background for easier product detection [2]. This involves transferring the entire BGC into a well-characterized and genetically tractable host like Streptomyces coelicolor or S. lividans [2] [5]. The main disadvantage is that it can be technically challenging to clone large BGCs, and the biosynthetic machinery may not function optimally in a foreign cellular environment [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: BGC Shows No Expression Under Standard Lab Conditions

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Repressive regulation.

- Solution: Identify and disrupt genes encoding transcriptional repressors within or outside the BGC. Alternatively, introduce chemical inducers. For example, in Burkholderia thailandensis, the global repressor MftR controls several BGCs, and its inhibition by urate can activate these clusters [6].

- Protocol: To test for urate induction, cultivate the producer strain in a suitable medium supplemented with a physiologically relevant concentration of urate (e.g., 200 µM to 5 mM). Use RNA sequencing or a reporter gene system to monitor BGC expression [6].

Cause 2: Lack of the necessary environmental trigger.

- Solution: Employ co-cultivation. Cultivate the producer strain in the presence of another microbe to simulate ecological interactions.

- Protocol:

- Select an interaction partner (e.g., from a library of actinomycetes).

- Co-culture the strains on solid agar, either in direct contact or separated by a membrane (to determine if physical contact is required).

- Use HPLC-MS or imaging mass spectrometry to compare the metabolome of the co-culture with monoculture controls [4].

Cause 3: Incompatible culture medium.

- Solution: Systematically alter cultivation parameters using the OSMAC (One Strain Many Compounds) approach.

- Protocol: Ferment the same strain in at least 5-10 different media with varying carbon/nitrogen sources, pH, and salinity. Extract metabolites after different incubation periods and analyze by HPLC-MS to detect condition-specific metabolites [4] [5].

Problem: BGC is Expressed, but No Expected Product is Detected

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: The product is truly novel and falls outside standard detection parameters.

- Solution: Use advanced, untargeted metabolomics.

- Protocol: Perform high-resolution LC-MS/MS analysis of the culture extract. Use computational tools like molecular networking (e.g., with GNPS) to visualize the entire metabolome and identify unique ions that are upregulated when the BGC is activated. This can help prioritize unknown features for isolation [7].

Cause 2: The cluster requires specific precursors or cofactors not present in the medium.

- Solution: Supplement the medium with predicted precursors.

- Protocol: Based on the bioinformatic prediction of the natural product class (e.g., PKS, NRPS), supplement the fermentation medium with potential starter units or amino acid precursors. For example, feed isotope-labeled precursors (e.g., ¹³C-acetate) and use isotope-guided fractionation to track the cryptic metabolite [4].

Problem: Native Producer is Uncultivable or Genetically Intractable

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inability to manipulate the host or achieve adequate growth.

- Solution:

- Ribosome Engineering: Isolate spontaneous antibiotic-resistant mutants. This is a genetics-light approach that alters cellular physiology.

- Protocol: Plate a dense cell suspension on agar containing a sub-lethal concentration of streptomycin (to target ribosomal protein S12) or rifampicin (to target RNA polymerase). Screen resistant mutants for enhanced or new antibiotic production [5].

- Heterologous Expression: Clone the entire BGC into a model host.

- Protocol: This is a multi-step process: (a) Clone the large BGC into a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) or use transformation-associated recombination (TAR) in yeast. (b) Introduce the assembled construct into a heterologous host such as S. lividans or S. albus via intergeneric conjugation. (c) Screen exconjugants for production of the target compound [2] [4].

- Ribosome Engineering: Isolate spontaneous antibiotic-resistant mutants. This is a genetics-light approach that alters cellular physiology.

- Solution:

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Ribosome Engineering via Streptomycin Selection

This protocol outlines a method to generate antibiotic-overproducing mutants in Streptomyces by inducing ribosomal mutations [5].

- Culture Preparation: Grow the target Streptomyces strain in a rich liquid medium until late-exponential phase.

- Mutant Selection: Plate a concentrated suspension of spores or mycelium onto agar plates containing streptomycin at a concentration of 2-10 µg/mL (this must be pre-determined as the minimal concentration that inhibits growth).

- Isolation: Incubate plates until spontaneous resistant mutants form colonies (typically 3-7 days).

- Fermentation and Screening: Inoculate the mutant strains into production media and cultivate alongside the wild-type strain.

- Analysis: Extract metabolites from culture broths and analyze via HPLC-MS or bioassay against a sensitive indicator strain to identify mutants with activated or enhanced antibiotic production.

- Validation: Confirm the mutation by sequencing the rpsL gene (encoding ribosomal protein S12), where a common Lys-88 to Glu or Arg mutation is often responsible [5].

Protocol 2: Reporter-Guided Mutant Selection (RGMS)

This protocol uses a fluorescent or antibiotic resistance reporter to screen for mutants where a cryptic BGC has been activated [2].

- Reporter Construction: Fuse the promoter of a key biosynthetic gene from the target BGC to a reporter gene (e.g., gfp for fluorescence or neo for kanamycin resistance) on a plasmid.

- Strain Engineering: Introduce the reporter construct into the wild-type producer strain.

- Mutagenesis: Create a random mutant library of the engineered reporter strain using UV mutagenesis or transposon (Tn) insertion.

- Mutant Selection: Screen or select for mutants based on the reporter signal. For Tn mutagenesis, the insertion site can be easily mapped to identify the inactivated gene responsible for activation.

- Metabolite Analysis: Ferment the selected mutants and analyze their metabolome to discover the cryptic natural product(s) produced by the activated BGC [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Cryptic BGC Activation Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [1] [8] | Bioinformatic tool for BGC identification and annotation. | The primary tool for initial BGC discovery; results should be manually curated. |

| Streptomycin / Rifampicin [5] | Antibiotics for ribosome engineering selection. | Use sub-inhibitory concentrations to select for spontaneous resistant mutants with altered metabolism. |

| Urate (Sodium Salt) [6] | Chemical inducer for MftR-regulated BGCs in Burkholderia. | A physiologically relevant signaling molecule encountered during host infection. |

| HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid) [4] | Epigenetic modifiers to alter chromatin structure and activate silent genes in fungi. | Can lead to global metabolic changes, not just activation of a single target cluster. |

| Heterologous Hosts (e.g., S. coelicolor, S. lividans) [2] [5] | Genetically tractable platform strains for BGC expression. | Choose a host with a minimized native metabolome to reduce background interference. |

| Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) Vectors [2] | Cloning system for large DNA fragments (>100 kb). | Essential for capturing and transferring entire BGCs for heterologous expression. |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

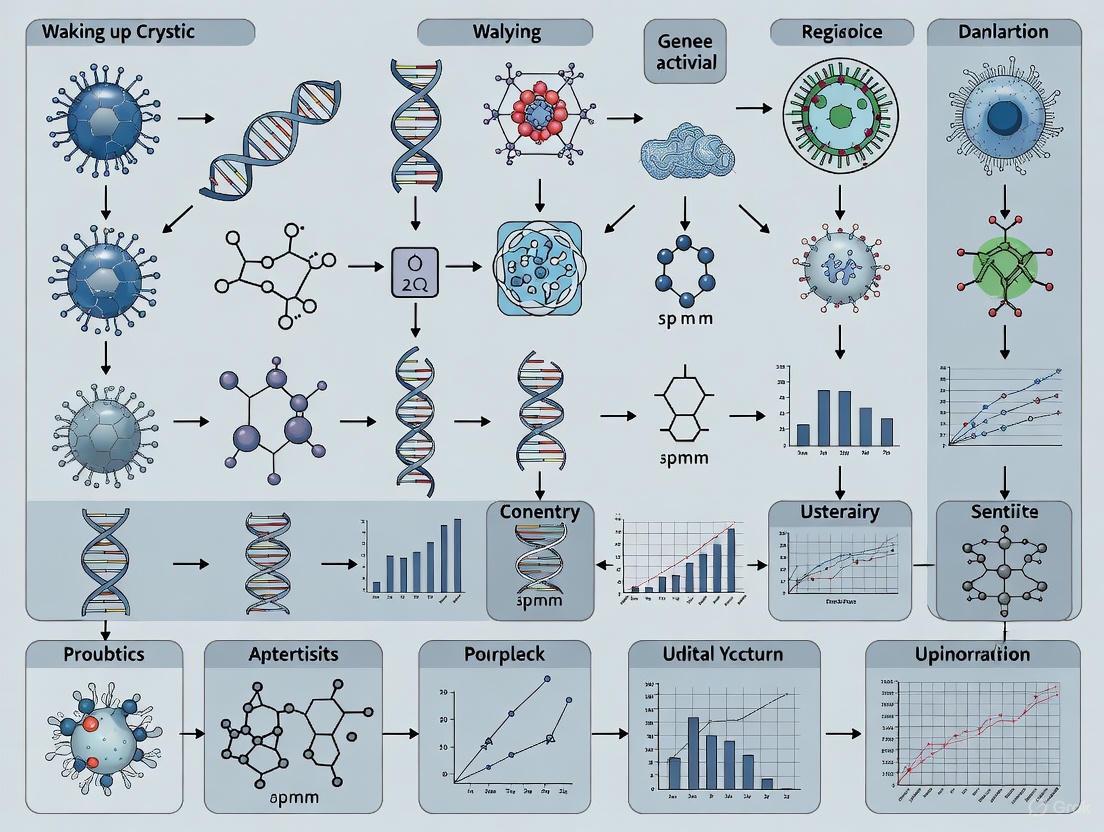

Diagram 1: BGC Classification and Experimental Strategy

Diagram 2: Cryptic BGC Activation Workflow

In the genomes of prokaryotes, and most famously in gifted actinomycetes, lies a vast, untapped treasure trove of potential new natural products, including novel antibiotics. Bioinformatic analyses of sequenced microbial genomes routinely reveal a remarkably large number of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs)—sets of genes responsible for the synthesis of a natural product—for which the corresponding metabolites are unknown [4] [9]. These are known as orphan clusters. A significant subset of these clusters are "silent" or "cryptic," meaning they are not expressed, or are expressed only at very low levels, under standard laboratory growth conditions [4] [10].

The silent nature of these BGCs presents a major challenge and opportunity for natural product discovery. It is estimated that silent clusters outnumber the constitutively active ones by a factor of 5–10, suggesting a hidden realm of microbial chemistry waiting to be discovered [9]. Unlocking these clusters is critical for accessing new therapeutic leads and for understanding microbial chemical ecology [9].

FAQs: Understanding Silent Gene Clusters

Q1: What is the fundamental genomic reason why a gene cluster is "silent"? A1: A gene cluster is classified as silent when its genes are not transcribed, or are transcribed at very low levels, under typical laboratory fermentation conditions. This is not due to a defect in the DNA sequence but because the chemical or environmental signals necessary for triggering the pathway are absent in the lab setting [4]. The cluster is essentially in a state of transcriptional repression.

Q2: Beyond the absence of a trigger, what are the specific molecular mechanisms enforcing this silence? A2: Research has identified several key regulatory mechanisms that can silence a BGC:

- Lack of Cluster-Specific Activation: Many BGCs contain genes for pathway-specific transcription factors. In the absence of the required inducing signal, these activators are not produced, keeping the entire cluster off [4].

- Epigenetic Silencing: In eukaryotic microbes like fungi, DNA can be packaged into a closed chromatin structure through modifications like histone deacetylation. This structure makes the DNA physically inaccessible to the transcription machinery, effectively silencing the genes within that region [4].

- Global Regulatory Control: Master regulatory proteins, such as LaeA in fungi, control the expression of many secondary metabolite gene clusters simultaneously. Deletion or disruption of such global regulators can lead to the silencing of multiple BGCs [4].

- Ribosomal and Transcriptional Fidelity: In bacteria, the efficiency of transcription and translation can globally impact secondary metabolism. Mutations in ribosomal proteins or RNA polymerase can surprisingly lead to the activation of silent clusters, indicating that the native state of these machineries can contribute to their repression [4].

Q3: Are there bioinformatic tools to identify silent clusters? A3: Yes. The primary method is genome mining. Sequencing a microbial genome allows researchers to use bioinformatic tools (e.g., antiSMASH) to scan for hallmark genes of secondary metabolism, such as polyketide synthases (PKSs) and nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs). Any identified BGC for which no product is detected under laboratory growth conditions is a candidate silent or orphan cluster [4] [11].

Q4: What is the evolutionary advantage for a microbe to maintain silent gene clusters? A4: It is generally accepted that secondary metabolites provide a biological advantage in response to the environment, for instance, to compete against other organisms or to respond to specific stresses [4] [9]. Maintaining silent clusters allows a microbe to retain a large "chemical arsenal" that can be deployed only when needed, which is likely more energy-efficient than constitutively producing all possible compounds. The clusters are often evolutionarily conserved and can be horizontally transferred, facilitating the spread of these adaptive functions [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Overcoming Silence

When your experiment to express a silent BGC fails, follow this guide to diagnose and address the problem.

Common Failure Modes and Corrective Actions

| Problem Area | Specific Failure Mode | Recommended Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Manipulation | Failed promoter replacement or heterologous expression. | Optimize transformation protocol; use CRISPR-Cas9 for more precise editing; verify promoter strength and compatibility in the host [9]. |

| Culture Conditions | Standard lab media do not induce the cluster. | Employ the OSMAC (One Strain-Many Compounds) approach: systematically vary media composition, aeration, and culture vessel type [4]. |

| Environmental Cues | Missing biological or chemical interactions. | Use co-culture: cultivate the producer strain with other microorganisms to simulate natural competition and interaction [4]. |

| Epigenetic Block | Closed chromatin structure (in eukaryotes). | Cultivate the strain in the presence of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (e.g., suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid) to open chromatin [4]. |

| Regulatory Complexity | The cluster is under complex, multi-layer repression. | Combine strategies: use "ribosome engineering" (select for antibiotic-resistant mutants) to introduce global regulatory changes while also optimizing culture conditions [4]. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Heterologous Expression of a Silent BGC

- Principle: Clone the entire silent BGC and express it in a genetically tractable host (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor or Aspergillus oryzae).

- Methodology:

- Identify and clone the target BGC, often using BAC (Bacterial Artificial Chromosome) or TAR (Transformation-Associated Recombination) cloning.

- Introduce the cloned cluster into a suitable heterologous host via transformation.

- If the native promoters are weak, replace them with strong, inducible promoters functional in the host.

- Screen for metabolite production in the heterologous host through LC-MS or biological activity assays [4].

Protocol 2: Promoter Replacement via CRISPR-Cas9

- Principle: Precisely replace the native promoter of a silent BGC with a strong, constitutive promoter to drive expression.

- Methodology:

- Design a CRISPR guide RNA (gRNA) to target the sequence immediately upstream of the BGC's first gene.

- Construct a donor DNA template containing the new promoter.

- Co-transform the gRNA, Cas9 protein, and donor DNA into the producer strain.

- Screen for successful promoter replacement via antibiotic selection or PCR [9].

Protocol 3: High-Throughput Elicitor Screening (HiTES)

- Principle: Identify small molecule "elicitors" that naturally induce the silent cluster.

- Methodology:

- Integrate a reporter gene (e.g., GFP, lacZ) into the silent BGC to provide an expression read-out.

- Expose the reporter strain to libraries of small molecules, such as supernatants from other microbes.

- Use high-throughput screening (e.g., fluorescence activation) to identify molecules that induce the reporter.

- Isolate and characterize the inducing molecule, then use it to activate the cluster in the wild-type strain [9].

Key Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Logic

The decision to activate a silent gene cluster often integrates multiple environmental and internal signals. The following diagram illustrates the core regulatory logic and major pathways that control the expression of silent biosynthetic gene clusters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Research Reagent | Function in Waking Up Silent Clusters |

|---|---|

| HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid) | Blocks histone deacetylase activity, leading to an open chromatin configuration and activation of epigenetically silenced clusters in fungi [4]. |

| DNMT Inhibitors (e.g., 5-Azacytidine) | Inhibits DNA methyltransferases, preventing DNA methylation and potentially reactivating genes silenced by this mechanism [4]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Enables precise genome editing for promoter replacement, activation, or deletion of repressors within silent BGCs in genetically tractable organisms [9]. |

| Inducible Promoters (e.g., tetO, PtipA) | Used in genetic constructs to place the expression of a cluster-specific transcription factor or the entire BGC under external control (e.g., by adding an antibiotic) [4] [9]. |

| Antibiotics for Ribosome Engineering (e.g., Streptomycin, Rifampicin) | Selection on sub-inhibitory concentrations yields mutants with altered ribosomal protein S12 or RNA polymerase, leading to pleiotropic activation of silent metabolism [4]. |

The explosion of microbial genome sequencing has revealed a hidden treasure trove of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) – sets of genes responsible for producing natural products like antibiotics, antifungals, and other bioactive compounds. In prolific secondary metabolite producers, these silent or cryptic BGCs outnumber the constitutively active ones by a factor of 5-10, representing an immense, largely untapped resource for drug discovery [9]. Bioinformatics genome mining, defined as the computational analysis of nucleotide sequence data based on the comparison and recognition of conserved patterns, provides the key to unlocking this potential [12]. This technical support center addresses the practical challenges researchers face when using antiSMASH and other genome mining tools to identify hidden BGCs, providing troubleshooting guidance and methodological frameworks to advance cryptic gene cluster research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is genome mining and what can it discover? Genome mining involves analyzing genomes with specialized algorithms to find BGCs that encode diverse natural products. These include polyketides (PKs), non-ribosomal peptides (NRPSs), ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), terpenes, saccharides, and alkaloids [12]. Each class has distinct biosynthetic machinery and potential pharmaceutical applications, from antibiotics like erythromycin to immunosuppressants like cyclosporine [12].

Why should I use antiSMASH over other tools? antiSMASH (antibiotics and Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell) is one of the most comprehensive tools for identifying and annotating secondary metabolite gene clusters across both bacterial and fungal genomes [13]. It provides integrated analysis of multiple BGC types, comparative genomics features against the MIBiG database, and predictive structural biology insights that make it particularly valuable for initial genome surveys [14] [13].

Can antiSMASH detect all types of gene clusters? No. antiSMASH specifically targets secondary metabolite BGCs and does not detect clusters involved in primary metabolism, such as those for fatty acid or cofactor biosynthesis [15]. If you believe a true secondary metabolite BGC is escaping detection, the antiSMASH developers encourage researchers to contact them to add the necessary detection models [15].

What input formats does antiSMASH support? antiSMASH accepts both annotated genomes in GenBank or EMBL format and unannotated genome sequences in FASTA format. For FASTA inputs, it offers integrated gene prediction using Prodigal or GlimmerHMM, though using a dedicated annotation pipeline like RAST first typically yields higher-quality results [15].

How are antiSMASH results organized and interpreted? antiSMASH results are organized by regions containing detected gene clusters. The visualization shows genes color-coded by function (biosynthetic genes in red, transport-related in blue, regulatory in green) [14]. Key elements include protoclusters (core biosynthetic machinery with neighborhoods) and candidate clusters (which may contain multiple protoclusters and are useful for identifying hybrid systems) [16]. The tool also provides comparisons with known clusters in the MIBiG database to help characterize novelty [16].

Troubleshooting Common antiSMASH Issues

Input File Problems

Error: "All records skipped" or "All input records smaller than minimum length"

- Causes: Records shorter than the 1,000 nucleotide default minimum length [17] or records containing no gene features when submitting GBK files to the web service [17].

- Solutions:

- Ensure at least one record exceeds the minimum length requirement

- Run genefinding tools prior to submission and verify genes are annotated as

CDSfeatures (notgenefeatures, which don't contain sufficient information) [17] - Adjust the

--minlengthparameter in the stand-alone version to suit your input data [17]

Error: "Multiple CDS features have the same name for mapping"

- Cause: Duplicate identifiers in CDS features, which may cause misleading results [17].

- Solution: Locate features with the duplicated identifier provided in the error message and either remove exact duplicates or change identifiers to be unique [17].

Error: "Record contains no sequence information"

- Cause: Valid record identifiers and annotations are present but no actual sequence data is included [17].

- Solution: Remove records lacking sequence information or include the missing sequence data in the input file [17].

General formatting errors in GenBank files

- Common Issues: Incorrectly formatted LOCUS lines, unusual character sets, or missing record terminators [17].

- Solutions:

- Ensure LOCUS lines are correctly formatted with all required fields

- Remove non-ASCII or non-UTF-8 characters

- Verify GBK files contain the record terminator

//at the end of each record [17]

Result Interpretation Challenges

Unexpectedly large gene clusters spanning multiple systems

- Cause: antiSMASH uses conservative border detection, sometimes including extra upstream/downstream genes rather than risk excluding key biosynthetic elements [15].

- Interpretation Guidance: Carefully examine comparative gene cluster analysis results (available in the "Homologous gene clusters" tab) to determine whether a large cluster represents a true hybrid or multiple separate clusters located close together [15].

Low similarity to known clusters in MIBiG

- Interpretation: This potentially indicates novel chemistry. The MIBiG comparison completion score is calculated as: Completion = (Number of genes with BLAST hits in both antiSMASH predicted region and MIBiG region) / (Number of all genes in the MIBiG curated region) [16].

- Recommended Action: Proceed with cluster characterization through additional analytical tools (e.g., PRISM, BAGEL, RODEO) depending on the BGC type [13].

Missing domain predictions or structural information

- Potential Causes:

- Running antiSMASH without all analysis modules enabled

- Low sequence similarity to characterized systems

- Novel biosynthetic mechanisms

- Solutions:

- Ensure all relevant prediction options are selected when configuring analysis

- Use complementary tools like PRISM for structural prediction of nonribosomal peptides, type I/II polyketides, and RiPPs [13]

- Consult specialized tools for specific BGC classes (e.g., BAGEL for bacteriocins and RiPPs, RODEO for RiPP precursor prediction) [13]

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Genome Mining Pipeline for BGC Discovery

Step 1: Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Extract high-quality genomic DNA from microbial cultures or environmental samples

- For metagenomic approaches, co-assemble reads from similar sample types using MEGAHIT with

--presets meta-sensitivefor improved BGC recovery [18]

Step 2: Genome Assembly and Quality Assessment

- Assemble quality-controlled reads using metaSPAdes (for individual samples) or MEGAHIT (for co-assembly) [18]

- Filter contigs (<1500 bp) using seqtk to reduce computational burden in downstream analysis [18]

- Assess assembly completeness and contamination with CheckM/CheckM2, retaining MAGs with ≥50% completeness and ≤10% contamination [18]

Step 3: BGC Prediction with antiSMASH

- Run antiSMASH with comprehensive parameters:

-taxon bacteria -genefinding-tool prodigal -cb-knownclusters -cc-mibig -cb-general -cb-subclusters -fullhmmer[18] - For bacterial genomes, use the "Bacteria" taxonomic classification option [19]

- Process results to extract key information: number of BGCs, types (NRPS, PKS, RiPPs, etc.), and locations

Step 4: Cluster Analysis and Prioritization

- Use BiG-SCAPE to analyze BGC families and classify antiSMASH outputs into gene cluster families with parameters:

--cutoffs 0.3 --include_singletons --mode auto[18] - Extract nucleotide sequences of promising BGCs from antiSMASH GBK outputs for further analysis [18]

- Query predicted compounds against specialized databases (MIBiG) using cheminformatic tools [19]

Step 5: Experimental Validation

- Select activation strategy based on genetic tractability of host (heterologous expression, promoter engineering, elicitor screening)

- For genetically amenable strains, consider CRISPR-Cas9 for promoter replacement [9]

- For non-model organisms, implement HiTES (high-throughput elicitor screening) to identify small molecule inducers [9]

Specialized Workflow for NRPS/PKS Clusters

Domain Analysis and Substrate Prediction

- For NRPS clusters: Identify adenylation (A), condensation (C), and peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) domains [14]

- For PKS clusters: Identify ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), and ketoreductase (KR) domains [14]

- Predict A-domain specificities using NRPSPredictor2 and Minowa methods [14]

- Predict PKS AT-domain specificities using signature sequence analysis and pHMMs [14]

Structure Prediction and Analysis

- Generate predicted core structures by combining domain analysis results [14]

- Extract SMILES representations from antiSMASH results for chemical analysis and database queries [19]

- Important: Recognize that predictions represent core structures only - final molecules often undergo additional modifications [14]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Bioinformatics Tools for BGC Discovery and Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Specific Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | BGC identification & annotation | Comprehensive detection of secondary metabolite BGCs; comparative analysis | [19] [13] |

| PRISM | Structural prediction of NPs | Prediction of NRPs, type I/II PKS, and RiPP chemical structures | [13] |

| BAGEL4 | RiPP & bacteriocin mining | Identification of ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides | [13] |

| ARTS | Antibiotic target prediction | Genome mining based on antibiotic resistance targets for novel compound discovery | [13] |

| BiG-SCAPE | BGC classification & networking | Analysis of BGC families across multiple genomes; gene cluster family classification | [13] |

| RODEO | RiPP precursor prediction | Identification of biosynthetic gene clusters and prediction of RiPP precursor peptides | [13] |

| RiPPER | RiPP genome mining | Exploration of thioamidated ribosomal peptides in Actinobacteria | [13] |

Table 2: Key Databases and Resources

| Resource | Content Type | Applications in BGC Research | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIBiG | Curated BGC database | Comparison of predicted clusters to experimentally characterized gene clusters | [19] [16] |

| NCBI SRA | Sequencing data repository | Access to raw sequencing data for metagenomic and transcriptomic analysis | [18] |

| GTDB | Taxonomic database | Standardized taxonomic classification of microbial genomes | [18] |

Advanced Applications: Activating Silent BGCs

CRISPR-Cas9 Promoter Insertion

- Replace native promoters of silent BGCs with constitutive or inducible variants in genetically tractable organisms [9]

- Particularly valuable for Streptomyces and other actinomycetes with complex genetics [9]

- Enables targeted activation of specific silent clusters for product characterization

High-Throughput Elicitor Screening (HiTES)

- Insert reporter genes (e.g., GFP) into silent BGCs to monitor expression [9]

- Screen libraries of small molecules to identify potential inducers of silent clusters [9]

- Effective for non-model organisms where genetic manipulation is challenging

Reporter-Guided Mutant Selection (RGMS)

- Combine genome-wide mutagenesis with reporter systems to select for hyperproducing mutants [9]

- Provides insights into regulatory networks controlling BGC expression

- Identifies indirect regulators that may silence multiple BGCs simultaneously

One Strain Many Compounds (OSMAC) Approach

- Systematic variation of cultivation parameters (media, temperature, aeration)

- Co-culture with potential microbial interactors to simulate ecological interactions

- Metatranscriptomic analysis to link BGC expression to specific growth conditions [18]

The end of the Golden Age of antibiotic discovery in the 1970s, marked by frequent rediscovery of known compounds, led to a critical gap in the antibiotic development pipeline [1]. However, the genomics revolution has revealed a vast, unexplored reservoir of potential novel drugs. Genome sequencing has shown that a single strain of filamentous Actinobacteria typically harbors 20 to 50 natural product biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), yet expresses very few under standard laboratory conditions [1]. This disparity highlights a universe of "hidden" biochemical diversity, with one study of 830 actinobacterial genomes identifying over 11,000 natural product BGCs representing more than 4,000 distinct chemical families [1]. Accessing these cryptic or silent clusters is now a primary imperative for modern drug discovery, offering a path to usher in a second Golden Era and combat the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance.

Defining the Terminology

Inconsistent use of the terms "cryptic" and "silent" has created confusion in the field. To ensure clarity:

- Cryptic describes BGCs and/or natural products that are hidden or unknown. This applies when a natural product has been observed but its cognate BGC has not been identified (Unknown Knowns), or when a BGC is expressed but its predicted product cannot be observed (Known Unknowns) [1].

- Silent describes BGCs that are not expressed under given laboratory conditions. Their expression may be induced by specific environmental cues or genetic manipulation [1].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common experimental challenges in the activation and characterization of cryptic gene clusters.

FAQ 1: Why is my bacterial strain not producing the expected novel compound under standard laboratory culture conditions?

Answer: This is a fundamental challenge in the field. Your BGC of interest is likely silent under the conditions you are using. Standard laboratory media and conditions often do not replicate the precise environmental or physiological signals required to trigger the expression of these clusters [1]. Furthermore, the compound itself may be cryptic, meaning it is produced at levels below the detection limit of your analytical methods or is modified in a way that masks its detection.

FAQ 2: After confirming expression of the target BGC via RT-qPCR, I cannot detect the compound. What could be the cause?

Answer: This scenario points to a cryptic product. The issue likely lies downstream of gene expression. Possible explanations include:

- Post-translational Regulation: The biosynthetic enzymes may not be active.

- Rapid Degradation: The compound is produced but is chemically unstable or is being degraded by other enzymes in the culture.

- Sequestration: The compound is being bound to cellular components or exported and adsorbed to the culture vessel.

- Incorrect Structural Prediction: Bioinformatic tools may have mispredicted the final chemical structure of the compound, leading you to look for the wrong molecule [1].

FAQ 3: What is the most efficient strategy to prioritize which cryptic BGCs to investigate from genome mining data?

Answer: Prioritization should be based on a combination of bioinformatic and strategic factors:

- Novelty: Focus on BGCs that show low similarity to clusters encoding known compounds using tools like antiSMASH and the MIBiG database [1].

- Taxonomic Origin: Prioritize BGCs from under-explored or unique microbial genera isolated from novel environments.

- Presence of Resistance Genes: Co-localization of putative self-resistance genes can indicate biological activity and a specific cellular target.

- Evolutionary Mining: Use algorithms like EvoMining, which can identify BGCs that have been missed by standard prediction tools, potentially revealing entirely novel chemistries [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: No Detectable Product After Heterologous Expression

Problem: After cloning and expressing a target BGC in a heterologous host (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor), no expected compound is detected.

Resolution: Follow this systematic troubleshooting process, adapted from general laboratory principles [20]:

Table: Troubleshooting Heterologous Expression

| Step | Possible Cause | Experimentation & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify Problem | Heterologous expression fails to produce compound. | Confirm the problem is specific to the compound, not host growth. |

| 2. List Explanations | - Cloning/Sequence Error- Poor Transcription- Poor Translation- Incompatible Host Physiology- Post-biosynthetic Modification | List all possible causes from start (DNA) to finish (compound). |

| 3. Collect Data | - Controls: Check growth of positive control host.- Storage: Verify integrity of genetic constructs.- Procedure: Review cloning and culture protocols. | Collect data on the easiest explanations first [20]. |

| 4. Eliminate & Experiment | - Sequence: Re-sequence the cloned cluster to check for errors.- Transcription: Use RT-qPCR to confirm mRNA is present.- Translation: Use Western blot (if antibodies are available) to check for enzyme production.- Host: Test different heterologous hosts or cultivation conditions. | Design experiments to test remaining explanations [20]. |

| 5. Identify Cause | The cause is the one remaining explanation after all others are eliminated. | Based on experimental results, implement a fix (e.g., re-clone, change host, optimize culture conditions) [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Activation and Characterization

Protocol 1: OSMAC-Based Activation of Silent BGCs

The One Strain Many Compounds (OSMAC) approach is a fundamental method to induce the expression of silent BGCs by varying culture conditions [1].

Methodology:

- Media Variation: Cultivate the producer strain in a panel of 5-10 different liquid and solid media (e.g., R2A, ISP2, SFM, Xylose-Tryptone). Viate carbon and nitrogen sources.

- Physical Parameters: Incubate parallel cultures at different temperatures (e.g., 20°C, 28°C, 30°C, 37°C) and agitation speeds.

- Co-cultivation: Introduce another microbial strain (bacterial or fungal) onto the same agar plate or in a divided co-culture system to simulate microbial competition.

- Chemical Elicitors: Supplement media with sub-inhibitory concentrations of potential elicitors such as heavy metals, histone deacetylase inhibitors (e.g., sodium butyrate), or antibiotics.

- Extraction and Analysis: After 3-7 days of incubation, extract culture broths and mycelia with organic solvents like ethyl acetate or methanol-dichloromethane (1:1) [21]. Analyze extracts using HPLC-MS and compare chromatographic profiles across conditions to identify unique metabolites.

Protocol 2: Extraction and Bioactivity-Guided Fractionation

This protocol outlines the process for extracting and isolating a bioactive compound from a microbial culture.

Methodology:

- Extraction: Separate the culture broth from the biomass via centrifugation or filtration. Extract the broth separately with a polar solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) and the biomass with a more non-polar solvent (e.g., dichloromethane/methanol 1:1) to cover a wide range of compound polarities [21].

- Concentration: Combine the organic extracts and concentrate them to dryness under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator.

- Initial Phytochemical Screening: Perform preliminary thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on the crude extract, spraying with specific reagents (e.g., anisaldehyde for sugars, Dragendorff's for alkaloids) or viewing under UV light to gain initial information on the chemistry [21].

- Bioactivity-Guided Fractionation:

- Use preparative TLC or column chromatography (e.g., silica gel, Sephadex LH-20) to separate the crude extract into fractions.

- Test all fractions for the desired bioactivity (e.g., antimicrobial, anticancer).

- Take the active fraction and subject it to further, higher-resolution separation using techniques like HPLC.

- Repeat the cycle of separation and bioassay until a pure, active compound is isolated [21].

- Characterization: Identify the structure of the pure compound using spectroscopic methods including NMR (1D and 2D), high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Cryptic Gene Cluster Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| antiSMASH Software | The primary bioinformatic tool for the genomic identification and annotation of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) [1]. |

| Ethyl Acetate | A medium-polarity solvent optimally used for the extraction of a broad range of medium-polarity bioactive compounds from culture broth [21]. |

| Dichloromethane-Methanol (1:1) | A versatile, relatively non-polar solvent mixture used for the efficient extraction of compounds from microbial biomass [21]. |

| Silica Gel (for Column Chromatography) | A standard stationary phase for the primary fractionation of crude natural product extracts based on compound polarity [21]. |

| Sephadex LH-20 | A size-exclusion chromatography medium used for de-salting and fractionating extracts, particularly useful for separating compounds from pigments. |

| MIBiG Database | A curated database of known BGCs, used as a reference for comparing and prioritizing newly identified clusters based on novelty [1]. |

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

Diagram 1: Cryptic Cluster Research Workflow

Diagram 2: Bioactivity-Guided Fractionation

The Activation Toolkit: Genetic, Environmental, and Synthetic Biology Strategies

A significant challenge in modern natural product discovery is the prevalence of cryptic or silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in prokaryotic genomes. Single Streptomyces genomes have been found to encode 25-50 BGCs, approximately 90% of which remain silent under standard laboratory cultivation conditions [22]. These clusters have the potential to encode novel antibiotics, anticancer agents, and other pharmaceuticals, but their silent nature poses a major barrier to discovery. Within the broader thesis on methods for awakening cryptic prokaryotic gene clusters, this technical support guide focuses specifically on in situ activation approaches—namely promoter engineering and transcription factor manipulation—to activate these silent genetic treasures within their native hosts.

Technical FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the primary molecular mechanisms that keep a gene cluster silent?

Silent BGCs are typically transcriptionally repressed through complex regulatory networks. The key mechanisms include:

- Lack of Inducer Signal: Many clusters require specific environmental or chemical elicitors that are not present in standard lab media [23].

- Repressive Chromatin State: In some cases, DNA may be in a transcriptionally inactive conformation.

- Absence of Specific Activators: Essential pathway-specific transcription factors may not be expressed under test conditions.

- Presence of Specific Repressors: Clusters may be actively silenced by dedicated repressor proteins that bind to promoter regions and block transcription [22].

FAQ 2: When should I choose in situ activation over heterologous expression?

In situ activation is generally preferable when:

- The native host has complex or unknown growth requirements that are difficult to replicate in a heterologous system.

- The gene cluster is extremely large (>100 kb), making cloning and manipulation challenging.

- The biosynthetic pathway relies on host-specific primary metabolism or cofactors.

- You have limited knowledge of cluster boundaries.

Heterologous expression is advantageous when the native host is uncultivatable, grows extremely slowly, or lacks genetic tools [22].

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Low Activation Efficiency After Promoter Replacement

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No detectable expression | Incorrect promoter integration | Verify integration via PCR and sequencing |

| New promoter is too weak | Use a stronger constitutive promoter (e.g., ermE*P) | |

| Critical regulatory elements missing | Include native 5' UTR and RBS with the new promoter | |

| Low expression level | Suboptimal promoter strength | Test a library of promoters with varying strengths |

| Metabolic burden on host | Use inducible promoter to control expression timing | |

| Toxic effects on host | Constitutive expression of toxic proteins | Switch to a tightly regulated inducible system |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Transcription Factor Manipulation Yields No Product

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No activation after TF overexpression | TF requires post-translational activation | Co-express potential modifying enzymes; add suspected effector molecules |

| TF is not the master regulator | Identify and co-express additional pathway-specific regulators | |

| Partial activation only | Insufficient TF expression level | Increase TF gene dosage; use stronger promoters |

| Multiple TFs regulate the cluster | Identify and manipulate all relevant regulators in the network | |

| Unpredictable results | TF has pleiotropic effects | Use cluster-specific TF mutants to avoid global regulation |

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Promoter Replacement via CRISPR-Cas9

This protocol enables targeted replacement of native promoters with strong constitutive or inducible variants in the native host [22].

Materials Required:

- CRISPR-Cas9 system (plasmid expressing Cas9 and guide RNA)

- Donor DNA containing new promoter with homology arms (60-80 bp)

- Host-specific transformation materials

- Selection antibiotics

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Design gRNA: Select a 20-nucleotide guide RNA sequence immediately upstream of the native promoter region of the target gene.

Construct Donor DNA: Synthesize a linear donor DNA fragment containing:

- Strong promoter (e.g., ermEP, *kasO*p, or rpsLp)

- Appropriate 5' UTR and RBS sequences

- 60-80 bp homology arms flanking the target site

Transform Host: Co-transform the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid and donor DNA into the native host.

Screen and Validate: Screen for successful recombinants via antibiotic selection and verify by colony PCR and sequencing.

Ferment and Analyze: Cultivate engineered strains under appropriate conditions and analyze metabolite production via LC-MS.

Protocol 2: Transcription Factor Activation Strategies

This protocol outlines multiple approaches to manipulate transcription factors for cluster activation [24] [22].

Materials Required:

- Vectors for TF overexpression (high-copy number plasmids)

- Chemicals for ribosome engineering (antibiotics)

- Potential elicitor molecules

Approach Selection Table:

| Method | Key Advantage | Typical Timeframe | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| TF Overexpression | Direct activation | 2-3 weeks | Variable (cluster-dependent) |

| Ribosome Engineering | Simple, no genetic manipulation required | 3-4 weeks | Moderate to high |

| Effector Addition | Non-genetic approach | 1-2 weeks | Low to moderate |

| Repressor Deletion | Removes negative regulation | 4-5 weeks | High (when repressor identified) |

Detailed Workflow for TF Overexpression:

Identify Target TF: Use bioinformatics tools to identify pathway-specific regulators within or near the target BGC.

Clone TF Gene: Amplify the TF coding sequence and clone into an expression vector with a strong, constitutive promoter.

Express TF in Native Host: Introduce the construct into the native host and confirm TF expression.

Analyze Metabolite Profile: Use HPLC and LC-MS to compare metabolite profiles of engineered versus wild-type strains.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for successful in situ activation experiments:

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pIJ10257, pSET152, pKC1139 | Shuttle vectors for TF overexpression and promoter delivery [22] |

| Promoter Libraries | ermEP, *kasO*p, rpsLp, tipAp | Provide a range of expression strengths for fine-tuning |

| CRISPR Systems | pCRISPomyces series | Enable precise genome editing for promoter replacement [22] |

| Ribosome Engineering Antibiotics | Streptomycin, Rifampicin, Gentamicin | Select for ribosomal mutations that activate ppGpp-mediated stress response [23] |

| Chemical Elicitors | N-Acetylglucosamine, Rare Earth Elements | Mimic natural environmental signals to trigger cluster activation |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Transcription Factor Activation Mechanism

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for In Situ Activation

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance Comparison of In Situ Activation Methods

| Method | Typical Time Investment (weeks) | Relative Cost | Technical Difficulty | Success Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter Replacement | 4-6 | $$-$$$ | High | Activation of jadomycin, pikromycin [22] |

| TF Overexpression | 3-5 | $-$$ | Medium | Activation of actinorhodin, streptomycin [23] |

| Repressor Deletion | 5-8 | $-$$ | Medium-High | Activation of scl BGC [22] |

| Ribosome Engineering | 3-4 | $ | Low | Activation of >20 cryptic clusters [23] |

Table 2: Common Constitutive Promoters for Streptomyces

| Promoter | Relative Strength | Origin | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ermE*P | High | Saccharopolyspora erythraea | Very strong, constitutive; ideal for strong overexpression [22] |

| rpsLp (XylR) | Medium-High | Mutant ribosomal protein S12 | Strong, constitutive; linked to ribosome engineering [23] |

| tipAp | Inducible | S. lividans | Thiostrepton-inducible; tight regulation when needed |

| kasO*p | Medium | S. coelicolor | Medium strength, constitutive; balanced expression |

In the field of natural product research, a significant challenge is that the vast majority of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in prokaryotes are silent or cryptic, meaning they are not expressed under standard laboratory conditions [9]. Heterologous expression—cloning and expressing BGCs in genetically tractable model hosts—has emerged as a powerful strategy to "wake up" these cryptic clusters. This approach bypasses the genetic intractability of native hosts and allows researchers to convert genetic potential into chemical reality, facilitating the discovery of novel compounds with potential pharmaceutical applications [25] [26]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and detailed methodologies to overcome common obstacles in these experiments.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Why is my heterologous expression host not producing the expected natural product, even after successful BGC cloning?

This is a common challenge often stemming from issues with cluster recognition, expression, or functionality in the new host environment.

- A1: Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect Cloning or Missing Regulatory Elements: The cloned fragment might be incomplete or lack native promoters and regulatory genes essential for expression.

- Solution: Verify the integrity of the cloned insert by sequencing and confirm it contains all necessary genes, including potential regulatory elements. Consider using vectors with strong, constitutive, or inducible promoters (e.g., using CRISPR-Cas9 to insert a strong promoter upstream of the BGC) to drive expression [9].

- Incompatibility with the Heterologous Host: The host may lack necessary precursors, post-translational modification machinery, or compatible tRNA pools for efficient synthesis, or it may express proteases that degrade the heterologous enzymes.

- Solution: Screen a panel of different, well-characterized heterologous hosts (e.g., various Streptomyces species, Pseudomonas putida, Bacillus subtilis) to find one that is more compatible [25]. Consider engineering the host to supply limiting precursors or delete problematic proteases.

- Silent Cluster in the New Context: The BGC may remain silent even in the new host due to lack of specific induction signals.

- Solution: Employ strategies like High-throughput Elicitor Screening (HiTES), where a reporter gene is inserted into the BGC and small molecule libraries are screened for inducers of cluster expression [9]. Alternatively, use Reporter-Guided Mutant Selection (RGMS) to select for host mutants that activate the cluster [9].

- Incorrect Cloning or Missing Regulatory Elements: The cloned fragment might be incomplete or lack native promoters and regulatory genes essential for expression.

Q2: What can I do if I encounter difficulties cloning a large BGC (>50 kb) into a vector system?

Large BGCs are fragile and difficult to clone using traditional restriction enzyme-based methods.

- A2: Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Inefficient In Vitro Assembly: Large fragments are prone to breakage and can be difficult to ligate efficiently.

- Solution: Utilize Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) cloning in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. This method leverages the high homologous recombination efficiency of yeast to directly capture large genomic fragments (up to 300 kb) into a yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) vector [25]. Ensure the TAR vector contains:

- Homology arms (typically 200-500 bp) specific to the ends of the target BGC.

- A counter-selectable marker (e.g., URA3) to prevent high background from empty vector recircularization via non-homologous end joining [25].

- Appropriate origins of replication and selection markers for your downstream heterologous hosts.

- Solution: Utilize Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) cloning in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. This method leverages the high homologous recombination efficiency of yeast to directly capture large genomic fragments (up to 300 kb) into a yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) vector [25]. Ensure the TAR vector contains:

- Inefficient In Vitro Assembly: Large fragments are prone to breakage and can be difficult to ligate efficiently.

Q3: How do I choose the right vector and host system for my heterologous expression experiment?

The choice of vector and host is critical and depends on the source of the BGC and the desired product.

- A3: Selection Guide:

- For Actinobacterial BGCs (e.g., from Streptomyces): Use integration vectors like pCAP01 that contain a ΦC31 attP site for stable chromosomal integration into specific host strains [25].

- For Expression in Bacillus subtilis: Use vectors like pCAPB02, which is designed for integration into the B. subtilis chromosome via double-crossover recombination at the amyE locus, ensuring stable maintenance [25].

- For Gram-Negative Proteobacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas putida): Select shuttle vectors that are stable and can replicate in these hosts [25].

- General Consideration: For very large clusters, Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs), which can maintain inserts of 150-350 kbp in E. coli, are a valuable tool for initial cloning and storage before shuttling into the expression host [27] [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below summarizes key reagents and vectors used in heterologous expression of BGCs.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Heterologous BGC Expression

| Reagent/Vector Name | Type | Key Features & Function | Compatible Hosts |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCAP01/pCAP03 [25] | Shuttle Vector (YAC) | Contains ΦC31 attP for chromosomal integration; TAR cloning; URA3 for counter-selection (pCAP03). | S. cerevisiae (cloning), E. coli, Streptomyces spp. |

| pCAPB02 [25] | Integration Vector | Contains homology arms for amyE locus; allows stable integration via double-crossover. | S. cerevisiae (cloning), E. coli, Bacillus subtilis |

| BAC (Bacterial Artificial Chromosome) [27] [28] | Cloning Vector | Based on F-plasmid; stable maintenance of very large DNA inserts (150-350 kb). | E. coli |

| TAR Vector System [25] | Cloning Platform | Uses yeast homologous recombination for direct capture of large genomic fragments. | Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System [9] | Genome Editing Tool | For precise promoter insertion upstream of silent BGCs to activate expression. | Various genetically tractable hosts |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for TAR Cloning of a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster

This protocol outlines the method for capturing a large BGC directly from genomic DNA using Transformation-Associated Recombination in yeast [25].

- Principle: The method uses homologous recombination in S. cerevisiae to co-recombine genomic DNA fragments with linearized TAR vectors containing homologous ends, resulting in a circular yeast artificial chromosome containing the entire BGC.

Materials:

- TAR Vector (e.g., pCAP01 or pCAP03 [25])

- Genomic DNA from the source organism (high molecular weight)

- S. cerevisiae strain (e.g., VL6-48N)

- Spheroplasting solutions (sorbitol, zymolyase)

- Selective media (e.g., SD/-Trp, with 5-FOA if using pCAP03)

Step-by-Step Method:

- Design and Prepare TAR Vector:

- Design a TAR vector (e.g., pCAP01 derivative) containing 200-500 bp homology arms that match the 5' and 3' ends of the target BGC.

- Linearize the circular TAR vector using appropriate restriction enzymes to expose the homology arms. Gel-purify the linearized fragment.

Prepare Genomic DNA:

- Extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from the source organism. Gently fragment the DNA by pipetting or brief sonication to an average size of 50-150 kb.

Prepare Yeast Spheroplasts:

- Grow a culture of the recipient yeast strain to mid-log phase.

- Treat the cells with zymolyase in a sorbitol buffer to enzymatically remove the cell wall, creating spheroplasts.

Co-transformation and Recombination:

- Mix the linearized TAR vector and the fragmented genomic DNA.

- Add the DNA mixture to the prepared yeast spheroplasts in the presence of PEG and calcium ions to facilitate DNA uptake.

- Allow homologous recombination to occur, which circularizes the vector and captures the BGC.

Selection and Screening:

- Plate the transformation mixture onto selective agar plates lacking tryptophan (to select for the TRP1 marker on the vector). If using pCAP03, include 5-FOA to counter-select against vectors that recircularized without an insert.

- Incubate plates for 3-5 days until colonies form.

Validation:

- Pick yeast colonies and screen for the presence of the correct recombinant by colony PCR.

- Isolate the Yeast Artificial Chromosome (YAC) DNA from positive clones and transform it into E. coli for amplification.

- Validate the final plasmid by restriction digest analysis and sequencing across the junctions.

Protocol for Activating Silent BGCs Using CRISPR-Cas9 Promoter Insertion

This protocol describes a genetic approach to activate a silent BGC by inserting a strong, constitutive promoter upstream of its biosynthetic genes [9].

- Principle: The CRISPR-Cas9 system creates a site-specific double-strand break near the target site of the silent BGC. A donor DNA template containing a strong promoter is provided, and the host's repair machinery incorporates it via homologous recombination, leading to constitutive expression of the downstream genes.

Materials:

- CRISPR-Cas9 system (plasmid expressing Cas9 and the sgRNA, or a ribonucleoprotein complex)

- Donor DNA template containing a strong promoter (e.g., ermE*p) flanked by homology arms (~1 kb) matching the sequence upstream and downstream of the Cas9 cut site.

- Standard molecular biology reagents for transformation and selection.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Target Selection and gRNA Design:

- Identify a target site for Cas9 immediately upstream of the core biosynthetic gene (e.g., the NRPS or PKS gene) of the silent BGC.

- Design and synthesize a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) specific to this target site.

Donor DNA Construction:

- Synthesize a linear donor DNA fragment containing a strong, constitutive promoter. This fragment must be flanked by homology arms (typically 500-1000 bp) that are homologous to the regions immediately upstream and downstream of the planned Cas9 cut site.

Delivery and Transformation:

- Introduce the CRISPR-Cas9 system (as DNA or pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein complexes) and the donor DNA fragment into the host organism using the appropriate method (e.g., protoplast transformation, electroporation for actinomycetes).

Selection and Screening:

- Allow the cells to recover and then plate them on medium containing the appropriate antibiotic to select for cells that have incorporated the donor DNA (which should include a selectable marker).

- Screen the resulting colonies for correct promoter insertion using colony PCR and confirm by DNA sequencing.

Metabolite Analysis:

- Ferment the engineered strain alongside the wild-type control under various conditions.

- Analyze the culture extracts using HPLC or LC-MS to detect the production of new secondary metabolites that are specific to the engineered strain.

The table below compares several key strategies for accessing the products of silent biosynthetic gene clusters, extending beyond heterologous expression.

Table 2: Strategies for Activation of Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

| Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Expression [25] | Cloning and expressing BGCs in a genetically tractable model host. | Bypasses host-specific regulation; applicable to uncultured microbes. | Cloning large fragments; host compatibility (precursors, folding). |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Promoter Insertion [9] | Site-specific insertion of a strong promoter to drive BGC expression. | Precise and targeted; can be applied to native hosts. | Requires genetic tractability and efficient transformation. |

| High-Throughput Elicitor Screening (HiTES) [9] | Using a reporter system to screen libraries of small molecules for BGC inducers. | Does not require genetic manipulation; can reveal ecological signals. | Requires construction of a reporter strain; hit molecules may be unknown. |

| Reporter-Guided Mutant Selection (RGMS) [9] | Coupling random mutagenesis with a reporter to select for activating mutants. | Can reveal novel regulatory genes and mechanisms. | Mutations may be complex and difficult to characterize. |

| Ribosome Engineering | Using sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics to perturb cellular physiology and activate secondary metabolism. | Simple to implement; can be highly effective. | Mechanism is indirect and often strain-specific. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Ribosome Engineering

FAQ 1: My bacterial strains treated with sub-inhibitory antibiotics are not showing activated cryptic gene clusters. What could be wrong?

- Potential Cause & Solution: The concentration of the inducing antibiotic is critical. Using a concentration that is too high will kill the cells, while a concentration that is too low will not generate the selective pressure needed to induce resistance mutations in ribosomal components.

- Protocol Adjustment: Perform a preliminary experiment to determine the sub-inhibitory concentration of antibiotics like streptomycin, rifampicin, or paromomycin for your specific bacterial strain. This is the highest concentration of antibiotic that does not visibly inhibit growth. Treatment with this concentration can induce mutations in genes like

rpsL(ribosomal protein S12) orrpoB(RNA polymerase β-subunit), leading to pleiotropic effects that activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [29] [23].

- Protocol Adjustment: Perform a preliminary experiment to determine the sub-inhibitory concentration of antibiotics like streptomycin, rifampicin, or paromomycin for your specific bacterial strain. This is the highest concentration of antibiotic that does not visibly inhibit growth. Treatment with this concentration can induce mutations in genes like

FAQ 2: I am not detecting new secondary metabolites after successful ribosome engineering. What steps should I check?

- Potential Cause & Solution: The activation of a BGC is only the first step. The secondary metabolite may be produced in very low titers, or your fermentation conditions may not be optimal for its production and detection.

- Protocol Adjustment: Review and optimize your fermentation protocol. Consider:

- Extended Incubation: Some metabolites are produced only in late stationary phase. Extend your fermentation time [29].

- Multiple Media: Use a panel of different culture media (e.g., varying carbon/nitrogen sources) to provide different physiological cues that can dramatically affect the yield of the awakened metabolite [29] [23].

- Metabolite Extraction: Ensure your extraction protocol (solvent polarity, pH) is suitable for the chemical class of the expected metabolite.

- Protocol Adjustment: Review and optimize your fermentation protocol. Consider:

FAQ 3: My engineered ribosome strain has a severe growth defect, hindering metabolite production. How can this be mitigated?

- Potential Cause & Solution: Mutations in core translational machinery (e.g.,

rpsL) can impose a fitness cost, slowing growth. This is a common trade-off.- Protocol Adjustment:

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution: Passage the slow-growing mutant strain sequentially in liquid culture to allow it to adapt and potentially acquire compensatory mutations that restore fitness while maintaining the activated phenotype [29].

- Use of Elicitors: Instead of, or in addition to, ribosome engineering, add chemical elicitors (e.g., rare earth metals, histone deacetylase inhibitors, or sub-inhibitory concentrations of other antibiotics) to the culture. These can activate cryptic clusters without genetically altering the ribosome, potentially avoiding severe growth defects [23].

- Protocol Adjustment:

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Ribosome Engineering via Antibiotic Selection

This protocol is used to generate antibiotic-resistant mutants with altered ribosomes or RNA polymerase, leading to the activation of cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters [29] [23].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Streptomycin Sulfate | Selective agent inducing mutations primarily in rpsL (ribosomal protein S12) [29]. |

| Rifampicin | Selective agent inducing mutations in rpoB (RNA polymerase β-subunit) [29]. |

| Paromomycin / Gentamicin | Alternative aminoglycoside antibiotics for inducing ribosomal mutations, sometimes with higher efficiency [29]. |

| R2YE Agar Plates | A common complex medium for the cultivation and selection of Streptomyces and other actinomycetes. |

| HT-2 (High-Throughput) Fermentation Media | A set of multiple liquid media with varied compositions used to screen for metabolite production under different conditions [23]. |

Methodology:

- Strain Preparation: Grow your target bacterial strain (e.g., a Streptomyces species) in an appropriate liquid medium to mid-exponential phase.

- Plating and Selection: Spread the cell suspension onto solid agar plates containing a sub-inhibitory concentration of your selected antibiotic (e.g., streptomycin at 1-5 μg/mL for Streptomyces; concentration must be determined empirically).

- Mutant Isolation: Incubate the plates until single colonies form. Resistant mutants will arise spontaneously.

- Purification: Pick and re-streak isolated resistant colonies onto fresh antibiotic plates to purify the mutant strains.

- Fermentation and Screening:

- Inoculate the mutant strains into a set of HT-2 fermentation media.

- Incubate with shaking for an extended period (e.g., 5-14 days).

- Analyze the culture extracts using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and compare the metabolic profiles to the wild-type strain to identify newly produced compounds [29] [23].

Protocol for Analyzing Ribosome Hibernation States

This protocol is used to identify and characterize the formation of hibernating ribosomes (e.g., 100S dimers or Balon-bound ribosomes) under stress conditions, which is crucial for understanding cellular survival mechanisms [30] [31].

Methodology:

- Stress Induction: Subject the bacterial culture to a specific stressor relevant to your study.

- Nutrient Starvation: Harvest cells in stationary phase.

- Cold Shock: Rapidly shift a growing culture to 0-4°C for 30-60 minutes [31].

- Other Stressors: Apply oxidative stress, acid stress, or antibiotic treatment.

- Ribosome Isolation: Lyse the cells gently using a bead beater or lysozyme treatment in a buffer containing Mg²⁺. Clarify the lysate by centrifugation. The ribosomes can be purified from the supernatant via ultracentrifugation through a sucrose cushion.

- Sucrose Density Gradient Centrifugation:

- Layer the ribosome extract on a 10-40% linear sucrose gradient.

- Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 150,000 x g for 2-4 hours) to separate ribosomal particles based on their mass and shape.

- Fractionation and Analysis:

- Fractionate the gradient and monitor the absorbance at 254 nm.

- Identify the peaks corresponding to 70S monosomes, polysomes, and hibernation complexes (e.g., 100S dimers or 70S particles with bound hibernation factors) [30] [31].

- For identification of specific hibernation factors like Balon, analyze the ribosomal fractions by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting or mass spectrometry [31].

Data Presentation: Efficiency of Ribosome Engineering

Table 1: Activation of Cryptic Gene Clusters via Antibiotic-Induced Ribosome Engineering [29]

| Antibiotic Used | Target Gene / Protein | Example Activated Compound(s) | Reported Fold-Increase in Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomycin | rpsL / Ribosomal Protein S12 |

Actinorhodin (in S. coelicolor) | Significant activation (from silent) |

| Rifampicin | rpoB / RNA Polymerase β-subunit |

Fredericamycin (in S. somaliensis) | Significant activation (from silent) |

| Paromomycin | rsmG / 16S rRNA methyltransferase |

Toyocamycin, Tetramycin A (in S. diastatochromogenes) | 4.1 to 12.9-fold |

| Gentamicin | Ribosomal Proteins | Antibiotics in S. coelicolor | Enhanced in double/triple mutants |

Table 2: Bacterial Stress Responses and Resulting Ribosome Heterogeneity [30]

| Stress Condition | Bacterial Species | Ribosomal Alteration | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Stress | E. coli | Formation of 61S ribosomes (lacking bS1, bS21) | Selective translation of leaderless mRNAs |

| Toxin Activation (MazF) | E. coli | 70SΔ43 ribosomes (cleaved 16S rRNA) | Selective translation of leaderless mRNAs |

| Growth Arrest | E. coli | Dimerization into 100S particles | Translational inactivation (hibernation) |

| Cold Shock / Stationary Phase | Psychrobacter urativorans | Binding of Balon protein to A-site | Ribosome hibernation, even on translating ribosomes |

| Zinc Starvation | E. coli | Replacement of Zn-binding L31/L36 with paralogs YkgM/YkgO | Zinc mobilization; maintained translation |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Bacterial Stress Response via Ribosome Remodeling. This workflow illustrates how different environmental stressors lead to specific ribosomal modifications, which in turn drive distinct cellular responses that enhance survival and can activate cryptic metabolic pathways.

Diagram 2: Formation and Role of Specialized Ribosomes. This diagram details the pathways through which specific stresses trigger the formation of specialized ribosomes, which perform distinct translational functions to facilitate rapid adaptation.

Microorganisms, particularly bacteria, are a prolific source of natural products with potential pharmaceutical applications, such as antibiotics and anti-cancer drugs. The blueprints for these molecules are encoded in Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) within the bacterial genome [32] [33]. However, a significant challenge in natural product discovery is that many of these BGCs are "cryptic" or "silent," meaning they are not activated under standard laboratory conditions, leaving a vast reservoir of chemical diversity untapped [34] [32].

Focusing on the prolific bacterium Streptomyces, researchers have developed ACTIMOT (Advanced Cas9-mediaTed In vivo MObilization and mulTiplication of BGCs), a groundbreaking CRISPR-Cas9-based method that artificially simulates the natural process of antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) mobilization to activate these cryptic clusters [34] [33]. This technical support center provides a detailed guide to implementing and troubleshooting the ACTIMOT system for unlocking new natural products.

Key Concepts: BGCs and the ACTIMOT Workflow

Prokaryotic Gene Clusters: A Rich Toolbox for Synthetic Biology

In bacteria, genes required for a specific, complex function—such as the synthesis of a natural product—are often grouped together in prokaryotic gene clusters [32] [35]. This organization facilitates the coordinated expression of these genes and allows for the horizontal transfer of the entire function between different bacterial species, a key evolutionary driver [32]. ACTIMOT leverages this natural principle for biotechnological ends.

The ACTIMOT Mechanism

The ACTIMOT system mimics the widespread dissemination of ARGs, which are mobilized by mobile genetic elements [34]. It uses a CRISPR-Cas9-based "release plasmid" (pRel) to make precise double-strand breaks in the chromosome, excising the target BGC. A separate "capture plasmid" (pCap), equipped with a multicopy replicon, then relocates and multiplies the freed BGC [34]. This multiplication creates a gene dosage effect, often sufficient to wake up the cryptic pathway and lead to the production of the encoded natural compound directly in the native strain or in a heterologous host [34] [33].

Visual summary of the core ACTIMOT workflow for activating cryptic gene clusters.

Experimental Protocols

Core ACTIMOT Workflow for BGC Activation

The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing the ACTIMOT system in Streptomyces.

Step 1: Target Selection and gRNA Design

- Identify Target BGC: Use genome mining software to identify a cryptic BGC of interest in the bacterial chromosome.

- Design gRNA Sequences: Design two single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) that bind to the flanking regions of the target BGC. The target sites must be adjacent to a 5'-NGG-3' PAM (Protospacer Adjacent Motif) [36].

- Check Specificity: Ensure the 12-nucleotide "seed" region adjacent to the PAM has minimal similarity to other genomic regions to reduce off-target effects [36].

Step 2: Plasmid Construction

- Build the Release Plasmid (pRel): Clone the expression cassettes for Cas9 and the two sgRNAs into a plasmid containing the SG5 Streptomyces replicon.

- Build the Capture Plasmid (pCap): Clone upstream and downstream homologous arms (corresponding to the regions just outside the BGC excision points) into a plasmid containing a multicopy Streptomyces replicon and a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC). A PAM cassette should be placed between the homologous arms [34].

Step 3: Plasmid Transfer and BGC Mobilization

- Co-transfer Plasmids: Introduce both the pRel and pCap plasmids into the native Streptomyces host strain via conjugation or protoplast transformation.

- Induce Excision and Capture: The expressed Cas9/sgRNA complex from pRel creates double-strand breaks, excising the target BGC. The pCap plasmid then acts as a template for homologous recombination, capturing and circularizing the mobilized BGC [34].

Step 4: Screening and Product Detection

- Select for Exconjugants: Plate transformations on appropriate antibiotics to select for strains that have successfully incorporated the plasmids.

- Screen for Product: Use liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to analyze culture extracts of exconjugants for the production of new or enhanced natural products.

- Validate BGC Capture: Isolate plasmid DNA from productive strains and use PCR or sequencing to confirm the successful relocation of the BGC to pCap.

Single-Plasmid ACTIMOT System

An optimized, single-plasmid version of ACTIMOT that combines the essential functions of pRel and pCap has also been developed, which simplifies the genetic manipulation and improves competence for natural product discovery [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: ACTIMOT Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential reagents and components for implementing the ACTIMOT system.

| Reagent/Component | Function in ACTIMOT |

|---|---|

| Release Plasmid (pRel) | Carries CRISPR-Cas9 system and sgRNAs to create double-strand breaks for precise BGC excision from the chromosome [34]. |