Troubleshooting Low Accuracy in Microbiological Method Verification: A Strategic Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing challenges with low accuracy during microbiological method verification.

Troubleshooting Low Accuracy in Microbiological Method Verification: A Strategic Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing challenges with low accuracy during microbiological method verification. It covers foundational principles from ISO, USP, and CLSI standards, explores methodological applications for qualitative and quantitative assays, details a systematic troubleshooting protocol to diagnose and correct accuracy issues, and outlines validation strategies to demonstrate method comparability and robustness. By integrating regulatory requirements with practical solutions, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to ensure data reliability, regulatory compliance, and patient safety.

Understanding Method Verification: Principles, Standards, and Common Pitfalls

Core Definitions: Verification vs. Validation

In pharmaceutical and clinical laboratory sciences, verification and validation are distinct but complementary processes essential for ensuring method and test reliability.

Verification confirms through objective evidence that specified requirements have been fulfilled. In laboratory practice, this means demonstrating that a method or test system performs according to its pre-defined specifications in your specific environment. For example, a laboratory performing CLIA-waived tests must verify that the test performs as stated by the manufacturer before implementing it for patient testing [1].

Validation establishes through objective evidence that a process consistently produces a result meeting its predetermined specifications and quality attributes. Validation provides a higher degree of assurance and is required for laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) or methods that are modified or created within the laboratory. For Rapid Microbiological Methods (RMMs), validation demonstrates the method is accurate, precise, specific, and robust for its intended purpose, proving equivalency or superiority to traditional compendial methods [2] [3].

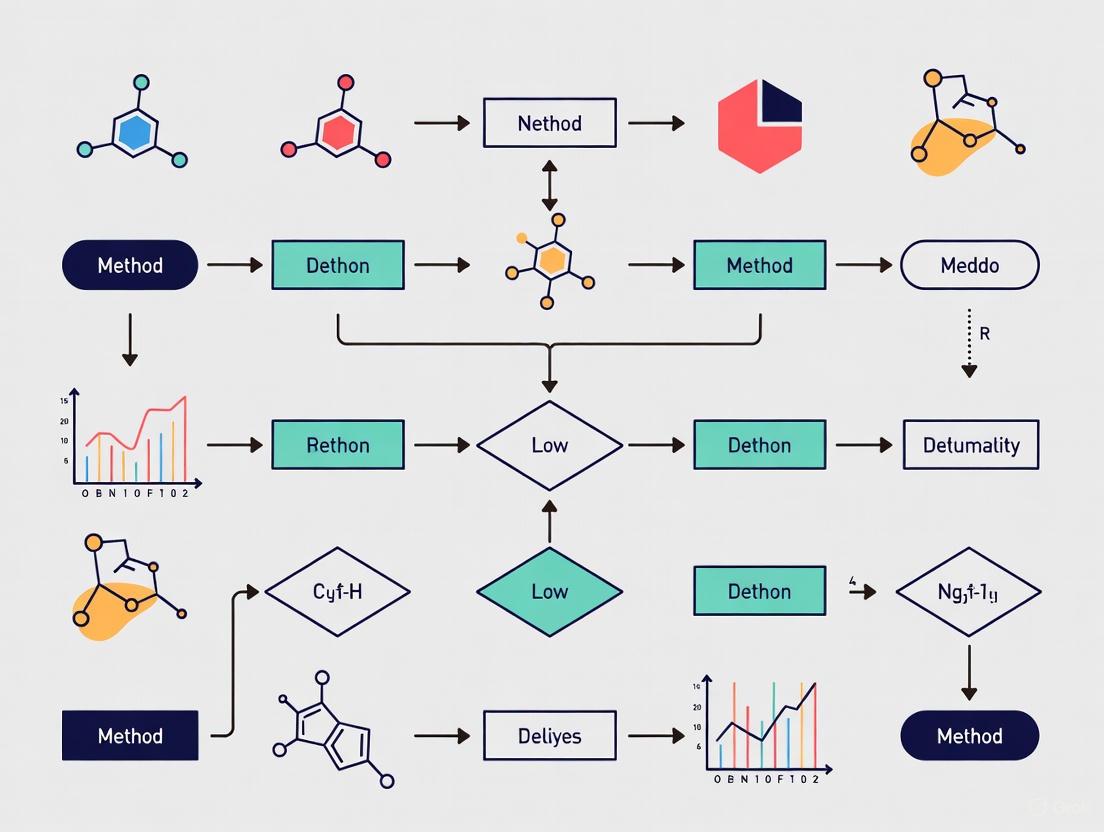

The relationship between these processes can be visualized as follows:

Regulatory Frameworks and Requirements

CLIA Proficiency Testing Requirements

The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) establish quality standards for laboratory testing. CLIA requires laboratories to enroll in Proficiency Testing (PT) programs for regulated analytes, with updated acceptance limits effective January 1, 2025 [4] [1].

PT evaluates a laboratory's testing performance compared to peer laboratories. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) enforces these regulations, with bolded analytes in the CAP Surveys catalog indicating CMS-regulated tests [1].

The table below summarizes selected 2025 CLIA acceptance limits for key analytes:

Table 1: Selected CLIA 2025 Proficiency Testing Acceptance Limits

| Analyte or Test | NEW 2025 CLIA Criteria | Previous Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Chemistry | ||

| Glucose | Target Value ± 6 mg/dL or ± 8% (greater) | Target Value ± 6 mg/dL or ± 10% (greater) |

| Creatinine | Target Value ± 0.2 mg/dL or ± 10% (greater) | Target Value ± 0.3 mg/dL or ± 15% (greater) |

| Hemoglobin A1c | Target Value ± 8% | None (Newly regulated) |

| Potassium | Target Value ± 0.3 mmol/L | Target Value ± 0.5 mmol/L |

| Toxicology | ||

| Digoxin | Target Value ± 15% or ± 0.2 ng/mL (greater) | None (Newly regulated) |

| Phenytoin | Target Value ± 15% or ± 2 mcg/mL (greater) | Target Value ± 25% |

| Hematology | ||

| Leukocyte Count | Target Value ± 10% | Target Value ± 15% |

| Hemoglobin | Target Value ± 4% | Target Value ± 7% |

| Immunology | ||

| Unexpected Antibody Detection | 100% accuracy | 80% accuracy |

Pharmaceutical Microbiology Validation Frameworks

For Rapid Microbiological Methods (RMMs) in pharmaceutical manufacturing, validation follows structured frameworks outlined in USP <1223> and Ph. Eur. 5.1.6 [2] [3]. These guidelines require demonstrating method equivalency to traditional compendial methods through defined validation parameters.

The complete RMM validation workflow encompasses multiple critical stages:

Key Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation

Successful method validation requires specific reagents and materials to generate scientifically sound evidence. The table below details essential reagents and their functions:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Microbiological Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides standardized benchmarks for accuracy assessment; verifies method calibration | Quantifying known microbial concentrations for accuracy studies [5] |

| Strain Collections (ATCC) | Well-characterized microorganisms for specificity and detection limit studies | Challenge studies to demonstrate method detection capabilities [2] |

| Culture Media | Supports microbial growth for compendial method comparison | Parallel testing for equivalency demonstration [5] |

| Validation Samples (Spiked) | Samples with known contaminant levels for recovery studies | Matrix interference testing and detection limit studies [2] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitors method performance precision and reproducibility | Routine system suitability testing [5] |

Troubleshooting Low Accuracy in Microbiological Methods

FAQ: How do I investigate low accuracy during method verification?

Q: Our microbiological method verification shows consistently low accuracy compared to reference methods. What systematic approach should we take to identify the root cause?

A: Troubleshoot low accuracy by investigating these key areas:

- Matrix Interference Effects: Product components can inhibit or enhance microbial detection. Conduct matrix interference studies by spiking product samples with known microbial levels and comparing recovery rates to control samples [2].

- Sample Preparation Consistency: Inconsistent sample handling directly impacts accuracy. Validate each preparation step and document any deviations. Automated systems can reduce variability [5].

- Reference Method Discrepancies: Ensure your reference method is properly validated. Discrepancies may reflect issues with the comparator method rather than your new method [2] [3].

- Instrument Calibration Status: Verify equipment calibration using certified reference materials. Document calibration dates and results [5].

- Operator Technique Variability: Implement robust training and competency assessment programs. Conduct intermediate precision studies with different operators [2].

FAQ: How do CLIA PT changes impact our verification processes?

Q: With the updated CLIA PT acceptance limits effective 2025, must we re-verify all our methods?

A: According to the College of American Pathologists, laboratories are not required to repeat prior verifications based solely on updated CLIA PT criteria. However, you should review performance goals used in subsequent verifications. CLIA PT acceptance limits are not intended as validation/verification performance goals, which should be based on clinical needs and manufacturer's FDA-approved labeling [1].

FAQ: What documentation is required for audit-ready validation?

Q: What essential documentation must we prepare to demonstrate RMM validation during regulatory audits?

A: Comprehensive documentation is crucial for audit readiness. Your validation package should include [2]:

- Validation Protocol: Pre-approved document defining scope, acceptance criteria, and experimental design

- Equivalency Study Data: Parallel testing results comparing RMM to compendial methods

- Risk Assessment: Documentation of potential failure modes and control strategies

- Standard Operating Procedures: Detailed instructions for method performance

- Training Records: Evidence of personnel competency on the new method

- Final Validation Report: Comprehensive summary with conclusions and management approval

Experimental Protocol: Demonstrating Method Equivalency

This protocol provides a standardized methodology for demonstrating equivalency between Rapid Microbiological Methods and traditional compendial methods, a common regulatory requirement [2] [3].

Materials and Equipment

- Reference method materials (agar plates, broth media, etc.)

- RMM system and associated reagents

- Certified microbial reference strains (at least 5-6 representative species)

- Product samples (for matrix studies)

- Diluents and neutralizers as appropriate

Procedure

- Study Design: Conduct parallel testing of samples using both RMM and the compendial reference method. Include appropriate controls.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare identical sample sets for both methods using aseptic technique.

- Inoculation: Inoculate samples with low, medium, and high concentrations of target microorganisms.

- Incubation/Analysis: Process samples according to both methods' standard procedures.

- Data Collection: Record quantitative results from both methods for statistical comparison.

- Statistical Analysis: Apply appropriate statistical tests (e.g., Student's t-test, F-test) to demonstrate equivalency.

Acceptance Criteria

Establish pre-defined acceptance criteria for accuracy (e.g., recovery rates within 70-130%), precision (e.g., CV ≤ 15%), and equivalency (e.g., no statistically significant difference between methods) [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the critical difference between method validation and method verification, and when is each required?

Method validation is a comprehensive process that proves an analytical method is acceptable for its intended use and is required when developing new methods. Method verification is the process of confirming that a previously validated method performs as expected under your specific laboratory conditions [6].

- Validation is essential for new drug applications, clinical trials, and novel assay development [6].

- Verification is acceptable and efficient for implementing standard or compendial methods (e.g., from USP, EPA, AOAC) in a laboratory [6].

Q2: Why are traditional, growth-based microbiological methods particularly challenging for accuracy and sterility testing?

Conventional growth-based methods, while compendial, have several inherent limitations that can impact accuracy [7]:

- Inability to Detect All Contamination: They are inefficient in detecting all microbial contaminants present in a sample [7].

- Inability to Discriminate Viability: They cannot distinguish between viable and non-viable microorganisms, which can lead to overestimation of viable bioburden [7].

- Lengthy Time-to-Result: They are time-consuming, delaying critical decisions in manufacturing and research [7].

- False Results: They are susceptible to both false-positive and false-negative results, compromising data reliability [7].

Q3: How should I handle non-detect (ND) results in microbial enumeration studies to ensure accurate concentration estimates?

A common misconception is to treat microbial non-detects as "censored" data less than a detection limit (e.g., <1 CFU), a practice borrowed from analytical chemistry. This is incorrect for discrete microbial data and can introduce bias [8].

- Correct Approach: Report the raw observation (e.g., 0 microorganisms) and the analytical sample size (e.g., volume tested). This preserves the probabilistic information needed for accurate statistical analysis and concentration estimation, consistent with how positive observations are handled [8].

- Underlying Science: Unlike chemistry, where signals come from vast numbers of molecules, microbiology deals with discrete objects. A non-detect means no microorganisms were observed in the specific volume tested, which is a probabilistic outcome related to the true concentration and recovery efficiency [8].

Q4: What special considerations are needed for methods used in low-microbial-biomass environments?

Samples with low microbial biomass (e.g., certain human tissues, purified water, cleanroom environments) are disproportionately affected by contamination, which can compromise accuracy and lead to false conclusions [9]. Key strategies include:

- Rigorous Contamination Controls: Use single-use, DNA-free consumables; decontaminate equipment with bleach or UV-C to remove DNA; and employ personal protective equipment (PPE) to limit human-derived contamination [9].

- Comprehensive Controls: Always include negative controls (e.g., empty collection vessels, swabs of the air, aliquots of preservation solution) that undergo the exact same processing as experimental samples. These are essential for identifying contaminating sequences [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Accuracy in Microbiological Method Verification

This guide addresses common pitfalls that compromise the accuracy of your verified method.

Problem 1: Inaccurate results due to poor specificity and interference.

- Potential Cause: The method cannot distinguish the target analyte from other components in the sample matrix, such as impurities, degradation products, or the sample background itself [10].

- Solution:

- Confirm Specificity: Demonstrate that the method can assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of these potential interferents. For microbial methods, this may involve testing the method with samples containing related but non-target microbial strains to ensure no cross-reactivity [10].

- Use Appropriate Controls: Include controls that mimic the sample matrix without the target analyte to identify any background signal.

Problem 2: High variability and poor precision undermining accuracy.

- Potential Cause: Uncontrolled variations in the testing procedure, including differences between analysts, equipment, reagents from different suppliers, or day-to-day operations [10].

- Solution:

- Assess Intermediate Precision: Design your verification study to include multiple runs by different analysts on different days using different equipment if possible. This evaluates the method's robustness in your lab [10].

- Standardize Reagents and Protocols: Use reagents from qualified suppliers and adhere strictly to the standard operating procedure (SOP). Investigate the robustness of the method by deliberately introducing small, validated changes to understand its tolerance [10].

Problem 3: Failure to detect low-level contaminants, leading to false negatives.

- Potential Cause: The method's Limit of Detection (LOD) is not suitable for the intended application, or contaminants are introduced during sample handling [10] [9].

- Solution:

- Verify the LOD: Confirm the method's LOD—the lowest concentration of analyte that can be reliably detected—under your laboratory's specific conditions. This is distinct from the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ), which is the lowest level that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [10].

- Implement Low-Biomass Precautions: If testing low-biomass samples, follow the stringent contamination control measures outlined in FAQ A4. The impact of contamination is magnified in these samples [9].

Problem 4: Non-detects (NDs) are handled incorrectly, biasing concentration estimates.

- Potential Cause: Reporting NDs as "<" values and treating them as censored data, which is a statistical approach misapplied from analytical chemistry [8].

- Solution:

- Report Raw Data: Always report the raw microbial count (zero) and the sample size tested. This allows for proper statistical modeling that accounts for the probabilistic relationship between the observation and the true concentration [8].

- Use Appropriate Statistical Models: Utilize methods like Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) that can correctly incorporate both positive and non-detect results based on the sample volume and method recovery efficiency [8].

Problem 5: The method is not robust under normal operating conditions in your lab.

- Potential Cause: The method's performance is highly sensitive to minor, inevitable variations in the analytical environment [10].

- Solution:

- Test Robustness During Verification: As part of verification, test the method's performance under deliberate, slight variations in operational parameters (e.g., incubation temperature fluctuations, reagent incubation times, different analyst techniques). This demonstrates the method's reliability in your hands [10].

Core Parameter Definitions and Experimental Protocols

The table below summarizes the core validation parameters, their definitions, and key verification experiments.

Table 1: Core Validation Parameters and Verification Experiments

| Parameter | Definition | Key Verification Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between the measured value and a reference value accepted as true [10]. | - Spike known concentrations of the target microorganism into the product or sample matrix.- Compare the results from the new method to those from a validated reference method.- Analyze certified reference materials (CRMs), if available. |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements from multiple sampling of the same homogenous sample. It has three tiers: repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility [10]. | - Repeatability: Analyze multiple replicates of the same sample by the same analyst under the same conditions in a single session.- Intermediate Precision: Analyze the same sample across different days, with different analysts, or using different equipment within the same lab. |

| Specificity | The ability to assess the target analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present (e.g., impurities, degradation products, sample matrix) [10]. | - Test the method with samples containing structurally similar or common contaminating microorganisms to ensure no cross-reactivity.- Test the method with the sample matrix without the target analyte to confirm the absence of interfering signals. |

| LOD / LOQ | LOD: The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified, under stated experimental conditions [10].LOQ: The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantified with acceptable levels of accuracy and precision [10]. | - For microbial methods, this often involves analyzing samples with progressively lower concentrations of the target microorganism.- LOD is typically the level at which the method transitions from intermittent detection to consistent non-detection.- LOQ is the lowest level where acceptable accuracy and precision (e.g., %CV) are consistently demonstrated. |

Method Verification and Troubleshooting Workflow

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for verifying a microbiological method and troubleshooting low accuracy issues.

Research Reagent and Material Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Microbiological Method Verification and Troubleshooting

| Item | Function in Verification/Research |

|---|---|

| Reference Microbial Strains | Certified strains used for spiking studies to establish accuracy, precision, LOD, and LOQ. They provide a known, quantifiable signal. |

| DNA-Free Reagents and Consumables | Specially treated reagents, water, and plasticware (e.g., tubes, filters) that minimize the introduction of contaminating DNA, which is critical for verifying methods for low-biomass samples [9]. |

| Negative Controls | Sterile samples or buffers that are processed alongside experimental samples. They are essential for identifying background contamination from reagents or the laboratory environment [9]. |

| Sample Preservation Solutions | Solutions (e.g., 95% ethanol, commercial kits like OMNIgene) that stabilize the microbial community in a sample from the moment of collection until analysis, preventing shifts that could affect accuracy [11]. |

| Culture Media | Growth substrates used in traditional compendial methods. Their quality, pH, and composition must be verified to ensure they support the growth of target and recovery microorganisms [7]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Low Accuracy in Method Verification

Q1: My method verification studies are consistently showing low accuracy against the reference method. What are the primary root causes I should investigate?

Low accuracy, indicating a systematic error or bias in your results, can stem from several sources. The following table outlines common causes and investigative actions based on principles from international standards.

| Root Cause Category | Specific Examples | Investigative Actions & Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Sample & Protocol Issues | Inconsistent sampling techniques or locations; improper sample homogenization; deviation from validated protocol timing [12]. | Audit aseptic techniques; implement timed protocols; verify sample mixing procedures; replicate sampling to assess inherent variability [12]. |

| Reagent & Equipment Problems | Contaminated plastic consumables (e.g., pipette tips, assay tubes); reagents not equilibrated to ambient temperature; incorrect pipette calibration [12]. | Perform background contamination checks on consumables; document reagent temperature equilibration; verify pipette calibration records and technician training [12]. |

| Method Suitability | Failure to demonstrate method suitability for the specific product (e.g., sample matrix interference) [13] [3]. | Re-run method suitability testing; spike product with known microorganisms to confirm recovery is not inhibited [13]. |

| Definition of 'Accuracy' | Applying an incorrect statistical model for the method type (qualitative vs. quantitative); attempting a direct statistical comparison of CFU to a non-growth-based signal where it is invalid [13]. | Consult USP <1223> and ISO 16140-2 for appropriate equivalence models (e.g., non-inferiority for qualitative methods, correlation curves for quantitative methods) [13] [14]. |

Q2: I am using a validated commercial test kit, but my in-house verification is failing. Is the kit faulty, or is my process wrong?

This common dilemma requires a structured investigation to isolate the problem. Follow the diagnostic workflow below to identify the most likely source of the failure.

Q3: The colony counts from my alternative method don't match the traditional CFU counts. Does this automatically mean my alternative method is inaccurate?

Not necessarily. A difference in counts does not automatically equate to inaccuracy. USP <1223> clarifies that the Colony-Forming Unit (CFU) itself is an estimate that can underreport the true number of microorganisms due to clumping, physiological state, and recovery limitations of growth-based methods [13]. Your alternative method (e.g., based on viability staining) might be providing a more accurate count of individual cells.

- Key Consideration: The core principle is to demonstrate equivalence or non-inferiority in assessing the product's microbiological quality and safety, not to achieve an identical count [13]. If the alternative method consistently detects microbial contamination and your validation data supports that it is as good as or better than the compendial method for its intended purpose, a numerical difference may be acceptable.

Q4: How do I handle highly variable results (poor repeatability) when performing ATP bioluminescence testing?

Poor repeatability in ATP tests is a frequent issue, often traced to procedural inconsistencies. The table below lists critical checkpoints.

| Checkpoint | Common Issue | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Homogeneity | Microorganisms distributed unevenly [12]. | Mix sample thoroughly before analysis; collect multiple samples from same location to assess variability [12]. |

| Reagent Handling | Luminase enzyme activity fluctuates [12]. | Allow enzyme to reach ambient temperature (e.g., 1 hour) before use [12]. |

| Pipetting Technique | Inaccurate or inconsistent liquid transfer [12]. | Ensure clean, calibrated pipettes; train analysts on technique; avoid reusing tips [12]. |

| Assay Timing | Reaction timing deviations between runs [12]. | Strictly adhere to protocol timing for reagent addition and measurement. |

| Background Contamination | Contaminated consumables inflating readings [12]. | Perform background checks on assay tubes; discard batches with high background RLU [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Verification Studies

Protocol 1: Equivalence Demonstration for a Quantitative Method

This protocol aligns with the "Results Equivalence" option in USP <1223> and the method comparison study in ISO 16140-2 [13] [14].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a set of samples (e.g., drug product placebo, buffer) contaminated with a low level of a representative microorganism (e.g., E. coli, S. aureus). Use a dilution series to obtain a range of microbial concentrations.

- Parallel Testing: Test each sample in parallel using both the alternative method and the compendial (reference) method. Ensure a sufficient number of replicates (e.g., n=3 per level) are performed to power the statistical analysis.

- Data Analysis: Plot the results from the alternative method (signal, count) against the results from the reference method (CFU). Generate a calibration curve or correlation curve.

- Statistical Evaluation: Evaluate the correlation for linearity, slope, and intercept. The alternative method is considered equivalent if the results show a consistent, predictable relationship with the reference method, demonstrating it is fit for its intended quantitative purpose [13].

Protocol 2: Verification of a Qualitative (Presence/Absence) Method

This protocol is critical for methods like sterility testing.

- Sample Inoculation: Prepare test samples by inoculating them with a low level of microorganisms (near the method's limit of detection). Also include uninoculated negative controls.

- Blinded Testing: Test the inoculated and control samples using the alternative method in a blinded fashion.

- Comparison to Reference: Compare the results (Positive/Negative) from the alternative method to those obtained from the compendial sterility test method.

- Calculation of Performance: Calculate the alternative method's Specificity (ability to correctly identify negative samples) and Sensitivity (ability to correctly identify positive samples). The method is considered non-inferior if its sensitivity meets or exceeds a pre-defined acceptance criterion relative to the compendial method [13] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Critical Function in Verification Studies |

|---|---|

| Strain Panel of Microorganisms | Used for challenging the method to demonstrate specificity and accuracy. Should include compendial strains, relevant environmental isolates, and stressed cells [15]. |

| Product-Specific Matrix | The actual product or placebo is essential for method suitability testing to prove the sample does not interfere with the alternative method's signal [13] [3]. |

| Reference Culture Media | Required for the compendial method and for the preparation and titration of the inoculum used in the study [15]. |

| Neutralizing Agents | Critical for testing sanitizers or biocide-containing products to ensure any antimicrobial activity is neutralized during the test, allowing for the recovery of viable microorganisms. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Used for instrument calibration and to provide a known value for establishing the accuracy and linearity of quantitative alternative methods. |

Identifying the Root Causes of Low Accuracy in Microbiological Contexts

FAQ: What are the most common root causes of low accuracy in microbiological method verification?

Low accuracy in microbiological method verification often stems from a range of factors, from sample-related issues to procedural errors. The table below summarizes the most frequent root causes and their impacts on data accuracy.

| Root Cause Category | Specific Issue | Impact on Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Sample & Matrix Effects | Presence of inhibitory substances in the product matrix [16] | Causes false negatives by preventing microbial growth, leading to underestimation of bioburden. |

| Method Suitability | Failure to perform or document suitability testing [16] [17] | Generates scientifically invalid data, as the method is not proven to work for the specific product. |

| Microbial Distribution | Low colony-forming unit (CFU) counts where Poisson distribution applies [18] [19] | Introduces significant inherent statistical variability, making counts less reliable and precise. |

| Culture Media | Use of media that fails Growth Promotion Tests (GPT) [17] | Compromises the ability to detect microorganisms, resulting in false negatives and invalidating tests. |

| Laboratory Technique | Improper sample handling, dilution errors, and incubation conditions [5] [19] | Introduces variability and bias, affecting both precision and accuracy of microbial enumeration. |

| Data Integrity | Incorrect colony counting and lack of a second-person verification [17] | Leads to transcription errors and unverified data, directly impacting the reported results' reliability. |

FAQ: How can I troubleshoot a "suitability test failure" for my product?

A suitability test failure indicates that your product's formulation inhibits the growth of the microorganisms you are testing for. The following workflow provides a step-by-step troubleshooting guide for this scenario.

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Confirm Failure: Verify that the failure is due to the non-recovery of the spiked organism in the presence of the product, not a laboratory error [16].

- Incorporate Inactivating Agents: Modify the method by adding suitable neutralizing agents to your dilution blank or enrichment medium. Common neutralizers include:

- Lecithin and Polysorbate 80 to neutralize quaternary ammonium compounds and phenolics.

- Sodium Thiosulfate to neutralize halogen-based disinfectants.

- Histidine to neutralize aldehyde-based disinfectants.

- Validate the effectiveness of the neutralizer by demonstrating the recovery of the spiked organism in the presence of both the product and the neutralizer [16] [19].

- Increase Diluent Volume: Substantially increase the volume of diluent used during the initial sample preparation. This dilutes the inhibitory substance to a level where it no longer affects microbial growth [16].

- Evaluate Alternative Methods: If the pour-plate method is used, switch to the membrane filtration method. This technique physically separates microorganisms from the inhibitory product, after which the membrane is transferred to a nutrient medium, thus bypassing the inhibition [16].

- Report Inherent Microbicidal Activity: If, despite all efforts, the spiked organism cannot be recovered, this demonstrates a powerful inherent antimicrobial property of the product. Per USP guidance, you can report that the product is not likely to be contaminated with the specified microorganism due to its pronounced microbicidal activity. Ongoing monitoring is still required [16].

FAQ: How does statistical variability at low microbial counts affect accuracy, and how can it be managed?

At low microbial counts (typically below 100 CFU), microorganisms are not evenly distributed in a suspension but follow a Poisson distribution. This is a fundamental source of variability that can lead to inaccurate counts [18] [19].

Experimental Protocol to Quantify Variability:

- Preparation: Create a suspension with a low, target concentration of a non-pathogenic microorganism (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538) at approximately 10 CFU/mL. Confirm the concentration using a validated method.

- Sample Plating: Independently plate one hundred 0.1 mL aliquots of this suspension onto soybean-casein digest agar plates.

- Incubation and Counting: Incubate the plates as per method requirements and count the CFUs on each plate.

- Data Analysis: Tabulate the results. You will observe that the counts are not uniform. A significant number of plates (theoretically ~37% at a mean of 1 CFU/plate) will have zero colonies, while others will have 1, 2, or more.

The table below illustrates the expected distribution from such an experiment, highlighting the inherent variability.

| Aliquot Number (Example) | CFU Count (per 0.1 mL) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 |

| ... | ... |

| 100 | 1 |

| Mean Calculated Concentration | ~10 CFU/mL |

Management Strategy: To manage this variability, increase the number of replicates and the sample volume tested. The root sum of squares approach can be used to estimate the total combined error from independent sources like CFU/plate variability, number of replicates, and dilution errors [18]. Averaging results from a larger number of replicates (e.g., 3-5 plates per sample) provides a more accurate and precise estimate of the true microbial concentration.

FAQ: What are the critical reagent and material solutions for successful method verification?

The reliability of your method verification is highly dependent on the quality and suitability of your reagents. The table below lists key materials and their critical functions.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Method Verification |

|---|---|

| Qualified Culture Media | Supports the growth of target microorganisms; must pass Growth Promotion Tests (GPT) with a recovery of ≥80% for each indicator organism [19] [17]. |

| Neutralizing Agents | Inactivates antimicrobial properties of the test product (e.g., lecithin, polysorbate 80, sodium thiosulfate) to enable recovery of microorganisms [16]. |

| Certified Reference Strains | Serves as positive controls for growth promotion and method suitability testing, providing a benchmark for expected recovery [5] [19]. |

| Environmental Isolates | Strains isolated from your own manufacturing environment; critical for proving the method can detect the organisms actually present in your context [19]. |

| Membrane Filters | Used in the membrane filtration method to separate microbes from inhibitory product matrices, thereby facilitating accurate enumeration [16]. |

FAQ: What are the regulatory consequences of inadequate method verification?

Regulatory agencies like the FDA consider inadequate method verification a serious violation of Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP). Recent warning letters highlight direct consequences [17]:

- Product Adulteration: Drugs released using methods with failed media Growth Promotion Tests (GPT) or without proper suitability testing are deemed "adulterated" [17].

- Inadequate Investigations: Citing "human error" for GPT failures without a specific, documented root cause analysis is unacceptable. This leads to a requirement for retrospective reviews and robust Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA) [17].

- Compromised Data Integrity: Allowing a single analyst to perform plate counting, data entry, and evaluation without a secondary check leads to incorrect counts and is a critical data integrity failure [17].

- Recommended External Audit: In severe cases, the FDA may recommend halting production and employing an external consultant with expertise in sterile manufacturing to conduct a comprehensive evaluation [17].

The Impact of Sample Matrix and Microbial Variability on Results

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do I get different results when testing the same microbial sample on different days? Microbiological systems possess numerous uncontrollable variables, leading to inherent experimental complexity and variability [20]. Key factors contributing to day-to-day differences include:

- Test System Variability: Minor fluctuations in incubation temperature, humidity, and the age/physiology of the microbial culture can significantly alter results [20].

- Operator Variability: Manual techniques like pipetting, inoculating surfaces, or applying a wipe can vary slightly between scientists and even from one repetition to the next by the same individual [20].

- Test Substance Variability: The age and storage conditions of disinfectants or antimicrobial agents can affect their stability and activity. Slight variations between production lots of a substance can also be a factor [20].

FAQ 2: What is a "matrix effect" and how does it impact my analytical results? The matrix refers to all components of your sample other than the analyte you are trying to measure [21]. Matrix effects occur when co-extracted components from the sample interfere with the detection of your target analyte, most commonly in techniques like LC-MS or GC-MS [21] [22]. This interference can cause either suppression or enhancement of the analyte signal, leading to inaccurate quantification [21]. For instance, matrix components can interfere with the ionization efficiency of an analyte in a mass spectrometer, causing a loss of signal [22].

FAQ 3: My method works perfectly with pure cultures, but fails with real-world samples. Why? This is a classic symptom of matrix effects or issues with sample preparation [21]. Real-world samples (e.g., food, clinical specimens, environmental samples) contain a complex mixture of components that are not present in pure solvent or culture standards. These matrix components can:

- Suppress or enhance analyte detection [21] [22].

- Interfere with the extraction of the target microbe or analyte from the sample [23].

- Be toxic to the microbes or inhibit their growth, leading to underestimation of counts [23].

FAQ 4: How can heterogeneous distribution of microbes in a sample affect my test results? Microbes are often not distributed uniformly in a sample (heterogeneity), which is a major source of test result variability [23]. This affects different stages of testing:

- Source Variability (VSOURCE): Biofilms form in localized patches on surfaces and interfaces, meaning two samples taken centimeters apart can have bioburdens that vary by an order of magnitude [23].

- Sample Variability (VSAMPLE): In viscous or non-aqueous fluids (like fuels or oils), microbes tend to clump, making replicate samples highly variable [23].

- Specimen Variability (VSPECIMEN): When you draw a small aliquot from a heterogeneous sample for testing, it may not be representative of the whole [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Quantifying Matrix Effects

Problem: Suspected matrix effect causing inaccurate quantification of an analyte.

Experimental Protocol: The following post-extraction addition method is a standard approach to quantify matrix effect [21] [22].

Prepare Samples: For a fixed concentration method, prepare at least five (n=5) replicates of each of the following [21]:

- Solvent Standard: The analyte dissolved in a neat solvent.

- Matrix-Matched Standard: A blank matrix extract (from the same type of sample, but known to be free of the analyte) spiked with the same concentration of analyte after the extraction process.

Analysis: Analyze all samples under identical instrument conditions within a single analytical run [21].

Calculation: Calculate the Matrix Effect (ME) factor for each analyte using the formula:

- ME (%) = [(B - A) / A] × 100

- Where A is the average peak response of the analyte in the solvent standard.

- Where B is the average peak response of the analyte in the matrix-matched standard [21].

- ME (%) = [(B - A) / A] × 100

Interpretation:

- ME ≈ 0%: No significant matrix effect.

- ME > 0%: Matrix-induced signal enhancement.

- ME < 0%: Matrix-induced signal suppression.

- As a rule of thumb, if the absolute ME value is greater than 20%, action should be taken to compensate for the effect to ensure accurate reporting [21].

Guide 2: Mitigating Microbial Heterogeneity in Samples

Problem: High variability in microbial counts between replicate samples or test specimens.

Solutions and Best Practices:

- Increase Sample Volume: For heterogeneous sources like fuels or oils, collecting a larger sample volume reduces the risk of missing microbial clumps and provides a more representative sample [23].

- Vigorous and Standardized Shaking: Use an adjustable, wrist-action shaker to disperse microbial flocs uniformly throughout the sample container before drawing a specimen for testing. This eliminates operator fatigue and ensures consistent force is applied to all samples [23].

- Use of Surfactants: Adding a surface-active agent (e.g., CTAB or Tween 80) can help break up clumps and improve the homogeneity of the bioburden in the sample [23].

- Separate Sample Phases: If a sample has multiple phases (e.g., oil, emulsion, and water), separate them into different containers and test each phase individually [23].

Diagram 1: Sources of Variability in Microbial Testing. This diagram traces the progression of variability from the original source to the final result, highlighting where errors are introduced [23].

Problem: General concerns about the reliability, reproducibility, and defensibility of microbiological method data.

Recommended Practices:

- Use Authenticated Biomaterials: Start experiments with traceable, authenticated, and low-passage reference microorganisms. Routinely evaluate biomaterials throughout the research workflow to ensure genotypic and phenotypic stability [24].

- Robust Calibration and Maintenance: Regularly calibrate and maintain all laboratory equipment, including pipettes, scales, and analytical instruments. Calibration is the most critical step for ensuring data accuracy [25].

- Operator Training and Standardization: Ensure all personnel are thoroughly trained on manual techniques. Use detailed, descriptive procedures to minimize inherent variability between scientists [20] [25].

- Publish and Share Negative Data: Contribute to the broader scientific community by making negative data (e.g., where a correlation was not found) accessible. This helps other researchers avoid dead ends and improves the overall efficiency of scientific progress [24].

Table 1: Common Sources of Variability in Antimicrobial Testing [20]

| Source Category | Specific Factor | Impact on Results |

|---|---|---|

| Test System | Temperature/Humidity fluctuations | Alters microbial physiology and reaction rates. |

| Microbial strain and age | Different strains and older cultures can react differently to antimicrobials. | |

| Growth media composition | Slight differences in brand or batch affect microbial physiology and metabolism. | |

| Operator | Pipetting technique | Affects the volume of inoculum or reagent added. |

| Inoculation of surfaces | Leads to uneven distribution of microbes on test carriers. | |

| Manipulation (e.g., wiping) | Differences in pressure and technique during manual steps. | |

| Test Substance | Age and storage conditions | Active ingredients degrade over time, reducing efficacy. |

| Variation between production lots | Slight differences in composition between batches. | |

| Dilution water hardness | High mineral content can decrease the efficacy of some antimicrobials. |

Table 2: Interpreting Matrix Effect Calculations [21]

| Matrix Effect (ME) Value | Interpretation | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| ± 10% | Minimal matrix effect | No action typically required. |

| ± 10% to ± 20% | Moderate matrix effect | Monitor closely; action may be needed for critical methods. |

| > ± 20% | Significant matrix effect | Action required. Use matrix-matched calibration, improve sample cleanup, or apply a correction factor. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Reliable Microbiological Testing

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Authenticated Reference Strains | Provides a standardized, traceable baseline for method verification and comparison. | Use ATCC or other recognized repository strains specified by regulatory guidelines (e.g., EPA) [24] [20]. |

| Standardized Growth Media | Supports consistent and reproducible microbial growth. | Follow recommended formulations (e.g., from EPA); be aware that different batches can introduce variability [20]. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Tween 80, CTAB) | Aids in dispersing microbial clumps in heterogeneous samples, improving homogeneity and representativeness [23]. | Optimize type and concentration for your specific sample matrix to avoid inhibiting microbial growth. |

| Matrix-Matched Blank Extracts | Serves as the baseline for quantifying and compensating for matrix effects in analytical methods [21] [22]. | Must be sourced from the same sample type (e.g., organic strawberries) known to be free of the target analyte. |

| Laboratory-Grade Hard Water | Used for diluting disinfectants to simulate real-world use conditions and test efficacy under standardized challenges [20]. | Hardness (PPM calcium) must be consistent, as it is known to decrease the efficacy of some antimicrobials. |

| Calibration Standards | Used to calibrate instruments and ensure the accuracy of quantitative measurements [25]. | Should be traceable to national or international standards. Prepare in both solvent and matrix for comparison. |

Implementing Robust Verification Protocols for Qualitative and Quantitative Assays

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common causes of low accuracy in a microbiological method verification? Low accuracy in microbiological method verification often stems from several key issues:

- Matrix Interference: The product itself (e.g., gels, creams, high-sugar solutions) can inhibit microbial growth or cause false positives/negatives, leading to poor recovery of microorganisms. [2]

- Improper Sample Handling: Inconsistent sample collection, storage, or preparation can compromise microbial viability and introduce errors. [5]

- Insufficient Method Equivalency Data: Failing to adequately demonstrate that the Rapid Microbiological Method (RMM) performs equivalently to the compendial method in accuracy, precision, and specificity. [2] [3]

- Incorrectly Defined Limits: The limits of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ) may not be suitably validated for the method's intended use, causing sensitivity issues. [2]

Q2: How many samples and replicates are sufficient to demonstrate method precision? The required number of samples and replicates depends on the validation parameter and the associated risk. The following table summarizes quantitative recommendations based on pharmacopeial guidance and best practices. [2] [26]

| Validation Parameter | Experimental Design (Samples & Replicates) | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Repeatability | A minimum of 6 valid replicates at a target concentration of 100% (or 3 concentrations, e.g., 50%, 100%, 150%, with 3 replicates each). [26] | Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) of not more than 10-15%, depending on the method's criticality. [2] |

| Intermediate Precision | Multiple analyses performed on different days, by different analysts, using different equipment. The number of replicates should mirror the repeatability study. [2] | The overall RSD from the combined intermediate precision data should be within 15-20%, demonstrating no significant variance between the different conditions. [2] |

Q3: What acceptance criteria should be used for accuracy (recovery) studies? Accuracy is measured by the percentage recovery of known concentrations of microorganisms from the product matrix. The table below outlines typical acceptance criteria. [2] [26]

| Microbial Concentration Level | Target Recovery Range | Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| High Concentration (e.g., for microbial enumeration) | 70% - 150% | Inoculate the product matrix or a placebo with a known, high concentration (e.g., 100 CFU) of a challenge organism. Recover and enumerate using the verified method. Compare the result to the inoculum count. |

| Low Concentration (e.g., at LOD/LOQ) | 50% - 200% | Inoculate the product matrix with a low concentration of a challenge organism (at or near the method's LOD/LOQ). The recovery rate at this level has a wider acceptable range due to higher inherent variability. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential materials for executing a robust microbiological method verification. [2] [5]

| Item | Function in Verification |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides standardized, traceable microbial strains with known characteristics for inoculum preparation, ensuring the accuracy and reproducibility of challenge studies. [5] |

| Neutralizing Agents | Inactivates antimicrobial properties of the product matrix or residual disinfectants in samples, allowing for accurate recovery of viable microorganisms. |

| Growth Media and Supplements | Supports the growth and recovery of microorganisms; used in compendial parallel testing and for the revival of challenge organisms. |

| Product-Specific Matrix (Placebo) | Allows for interference testing without the confounding variable of an active pharmaceutical ingredient, helping to isolate matrix-specific effects. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Demonstrating Method Equivalency through Parallel Testing This protocol is designed to validate a Rapid Microbiological Method (RMM) against a compendial method, as required by USP <1223> and Ph. Eur. 5.1.6. [2] [3]

- Define Scope: Clearly state the method's purpose (e.g., bioburden testing, sterility testing), sample type, and target microorganisms. [2]

- Select Challenge Strains: Choose appropriate compendial and product-specific isolates. [2]

- Prepare Inoculum: Create suspensions of challenge organisms at target concentrations in a product placebo and the actual product matrix. [2]

- Parallel Testing: Test each inoculated sample type in parallel using both the RMM and the compendial method (e.g., plate count). Use a statistically significant number of replicates (e.g., n≥3 per level). [2]

- Statistical Comparison: Analyze the results using statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, F-tests) to demonstrate equivalency. The RMM should show no significant difference from the compendial method in accuracy, precision, and specificity. [2] [3]

The workflow for this protocol is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Determining Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) This methodology aligns with the scientific, risk-based approach emphasized in modern pharmacopeias. [2] [26]

- Sample Preparation: Serially dilute a microbial suspension to very low concentrations in a product-specific matrix.

- Testing Dilutions: Test multiple replicates (recommended n≥5) at each dilution level using the verified method.

- Calculate LOD: The LOD is the lowest concentration level at which ≥95% of the replicates give a positive detection signal (for qualitative methods) or a measurable signal above background (for quantitative methods). [2]

- Calculate LOQ: The LOQ is the lowest concentration level that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy (e.g., 50-200% recovery) and precision (e.g., RSD ≤35%). This must be confirmed by direct experimental verification of recovery rates and precision at the claimed LOQ. [2] [26]

The logical relationship for establishing LOD and LOQ is as follows.

Troubleshooting Low Accuracy

If your verification study reveals low microbial recovery, investigate these areas:

- Conduct a Matrix Interference Study: Systematically spike the product with known microbes and compare recovery in the product versus a neutral buffer. If recovery is low in the product, optimize the sample preparation procedure, incorporate dilution, or use a neutralizing agent. [2]

- Verify Inoculum Viability and Count: The starting concentration of your challenge organism must be accurate. Use plate count methods to confirm the inoculum's viable count independently of the method being verified. [2]

- Review Sample Holding Conditions: Ensure that the time and temperature between sample inoculation and testing do not lead to microbial death or proliferation. [5]

Core Concepts: Accuracy and Precision

For qualitative microbiological assays, verifying accuracy and precision is a fundamental requirement before implementing a new, unmodified FDA-cleared test for clinical or research use [27].

- Accuracy confirms the acceptable agreement of results between the new method and a comparative method [27].

- Precision confirms acceptable reproducibility of results, assessing within-run, between-run, and operator variance [27].

The following workflow outlines the core process for planning and executing these verification studies:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Accuracy Testing

Accuracy testing demonstrates that your new method correctly identifies target organisms compared to a reference standard [27].

Detailed Methodology:

Sample Selection and Preparation:

Testing Procedure:

- Test all selected samples using the new qualitative assay.

- In parallel, test the same samples using a well-characterized comparative method. This could be the method currently in use in your lab or a reference method [27].

Data Analysis and Acceptance Criteria:

- Calculate the percentage agreement between the new method and the comparative method.

- Formula: (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100 [27].

- Compare the calculated percentage to the manufacturer's stated claims for accuracy or to a laboratory-defined acceptance criterion approved by the lab director [27].

Protocol for Precision Testing

Precision testing evaluates the reproducibility of your assay results under defined conditions, encompassing repeatability and intermediate precision [28] [27].

Detailed Methodology:

Sample Selection:

Testing Procedure for Intermediate Precision:

Data Analysis and Acceptance Criteria:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials required for conducting accuracy and precision studies:

| Item | Function in Verification |

|---|---|

| Reference Materials & Controls | Certified microbial strains or clinical samples with known status; serve as the benchmark for accuracy testing [27]. |

| De-identified Clinical Samples | Previously characterized patient samples used to verify accuracy and precision in a clinically relevant matrix [27]. |

| Proficiency Test Samples | Externally sourced samples of known, but blinded, identity; provide an unbiased assessment of assay accuracy [27]. |

| Culture Media | Supports growth and viability of challenge microorganisms; used in specificity and accuracy studies [28]. |

| Challenge Microorganisms | A panel of relevant microbial strains used to demonstrate the method's specificity and ability to detect the target in the presence of other organisms [28]. |

Troubleshooting Low Accuracy

FAQ: Why is my new assay showing low accuracy compared to my reference method?

Low accuracy typically manifests as a consistent discrepancy between the results from the new method and the reference method. The following diagram illustrates a logical troubleshooting path for this issue:

Specific Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm Sample Quality and Matrix: Ensure samples are stored correctly and are not degraded. For new sample matrices (e.g., different food types, swabs), assess for potential interferents like pectin (inhibits PCR) or high fat content (impedes microorganism access). A method validated for one matrix may not be accurate for another without a fitness-for-purpose study [29].

- Investigate Specificity: The method's ability to correctly identify the target analyte may be compromised. Challenge the assay with closely related non-target organisms to confirm it does not produce false positives. For molecular methods, verify primer/probe specificity [28].

- Re-evaluate the Reference Standard: The comparative method itself may have limitations or be imperfect. Investigate the performance characteristics of your reference method to ensure it is a reliable benchmark [27].

FAQ: My precision study shows high variation between runs and operators. What should I check?

High variation in precision studies points to issues with the method's reproducibility.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Standardize Operator Technique: This is a common source of variation. Ensure all personnel are thoroughly trained on the standardized protocol. Observe technicians performing the assay to identify deviations in technique [30] [27].

- Check Reagent and Equipment Consistency: Use the same lots of reagents and consumables throughout the study where possible. If different instruments are used, ensure they are properly calibrated and maintained. Document all reagent lots and equipment IDs [31].

- Review Environmental Controls: For methods involving microbial growth, small variations in incubation time or temperature can significantly impact results. Monitor and record environmental conditions to ensure they remain within the manufacturer's specified range throughout the study [28].

Sample Size Requirements for Verification Studies

The table below summarizes the minimum sample sizes and key parameters for accuracy and precision testing as recommended by guidelines:

| Parameter | Minimum Sample Size | Sample Types | Key Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy [27] | 20 isolates/samples | Combination of positive and negative samples; clinically relevant isolates. | % Agreement = (Results in Agreement / Total Results) × 100 |

| Precision (Intermediate) [27] | 2 positive + 2 negative samples | Tested in triplicate over 5 days by 2 operators. | % Agreement = (Concordant Results / Total Results) × 100 |

| Reportable Range [27] | 3 samples | Known positive samples (for qualitative); samples near upper/lower cutoff (for semi-quantitative). | Confirm result is within the established reportable range. |

| Reference Range [27] | 20 isolates/samples | De-identified clinical or reference samples representing the patient population. | Verify against manufacturer's claims or re-define for local population. |

Failure to properly verify and document performance specifications is a common regulatory citation. The table below lists frequent errors and their solutions:

| Pitfall | Consequence | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No verification performed; "out-of-the-box" use [30]. | Serious regulatory citation; risk to patient safety and data integrity [30]. | Perform and document full verification before clinical/research use [30]. |

| Only partial verification (e.g., accuracy but not precision) [30]. | Incomplete performance profile; unreliable results for one or more characteristics [30]. | Use a standardized protocol verifying all required parameters [30]. |

| Data exists but is not properly signed, dated, or stored [30]. | Citation during inspection; data may be considered invalid [30]. | Store signed/dated documents in an accessible, version-controlled location [30]. |

| Using a test for a sample matrix not specified by the manufacturer without a fitness-for-purpose study [29]. | Potential for inaccurate results due to matrix interference [29]. | Conduct a matrix extension study to confirm the test performs accurately in the new matrix [29]. |

Protocols for Quantitative and Semi-Quantitative Assay Verification

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between assay validation and verification? A1: Validation is a process to establish that a new or modified assay (such as a laboratory-developed test or a modified FDA-approved test) works as intended. In contrast, verification is a one-time study performed for unmodified, FDA-approved tests to demonstrate that the test performs according to established manufacturer specifications in your laboratory environment [32].

Q2: What are the core performance characteristics that must be verified for a semi-quantitative assay? A2: For semi-quantitative assays, the essential verification parameters are Accuracy, Precision, Reportable Range, and Reference Range [32]. These characteristics confirm the assay provides reliable and reproducible ordinal results (e.g., "negative," "low positive," "high positive").

Q3: My verification shows a high rate of false negatives. What could be the cause? A3: A high false-negative rate often indicates an issue with the assay's diagnostic sensitivity. Potential causes include [33] [34]:

- Improper sample storage or transport, leading to analyte degradation.

- Incorrect incubation times or temperatures.

- Reagent or equipment failure.

- The predefined cutoff value may not be optimal for your specific patient population.

Q4: What is the recommended sample size for verifying accuracy in a qualitative or semi-quantitative assay? A4: It is recommended to use a minimum of 20 positive and negative clinical samples or well-characterized isolates to verify accuracy. For semi-quantitative assays, these should cover a range from high to low values [32].

Q5: How do I handle discrepancies between my verification data and the manufacturer's claims? A5: First, repeat the experiment to rule out one-off operational errors. If discrepancies persist, investigate potential interfering substances in your sample matrix and confirm you are using the correct reference standard. Laboratory leaders, such as clinical microbiologists, should be consulted to review the data and determine if the method is acceptable for clinical use despite the discrepancy [32] [33].

Troubleshooting Low Accuracy in Method Verification

Low accuracy, indicating a failure to establish acceptable agreement with a reference method, is a common challenge. The following guide helps diagnose and resolve the underlying issues.

Troubleshooting Logic and Workflow

The diagram below outlines a systematic approach to troubleshooting low accuracy.

Detailed Investigation Steps

1. Check Sample Integrity & Handling

- Problem: Degraded samples, improper storage conditions, or use of an incorrect sample matrix can yield misleading results [34].

- Action: Verify that all samples were collected, transported, and stored according to the verification plan. Use certified reference materials or previously characterized clinical samples where possible [34].

2. Investigate Reagents & Equipment

- Problem: Expired or improperly reconstituted reagents, and poorly calibrated equipment are frequent sources of error [34].

- Action: Confirm that all reagents are within their expiry date and have been prepared correctly. Review equipment maintenance and calibration logs to ensure instruments are functioning within specified parameters.

3. Review Operator Technique & Protocol

- Problem: Deviations from the standard operating procedure (SOP), such as incorrect incubation times or pipetting errors, directly impact accuracy [34].

- Action: Ensure all personnel are thoroughly trained on the protocol. Implement a review of the technique and consider having a second operator perform the assay to rule out individual error.

4. Re-evaluate Reference Standard & Data Analysis

- Problem: An inappropriate reference standard or flawed statistical analysis can create a false impression of inaccuracy [33].

- Action: Confirm the reference method is the gold standard or a well-validated predicate method. Re-analyze the data using appropriate statistical tools for qualitative/semi-quantitative data, such as contingency tables and inter-rater agreement metrics [33].

Verification Protocols and Data Presentation

Core Verification Experiments and Sample Sizes

The table below summarizes the key experiments, their objectives, and the minimum sample sizes required for verifying qualitative and semi-quantitative assays [32].

| Performance Characteristic | Objective | Minimum Sample Sizes & Design |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | To confirm acceptable agreement with a comparative method. | Qualitative: 20+ clinical isolates (combination of positive and negative).Semi-quantitative: 20+ isolates with a range of high to low values [32]. |

| Precision | To confirm acceptable variance (within-run, between-run, between operators). | 2 positive and 2 negative samples, tested in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators [32]. |

| Reportable Range | To confirm the assay's upper and lower detection limits. | Minimum of 3 known positive samples. For semi-quantitative, include samples near the cutoff values [32]. |

| Reference Range | To confirm the expected "normal" result for the patient population. | Minimum of 20 isolates from the laboratory's typical patient population [32]. |

Example Protocol: Precision Verification for a Semi-Quantitative Assay

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for verifying the precision of a semi-quantitative assay, such as an ELISA-based microneutralization assay [35].

1. Experimental Design

- Samples: Select a minimum of two positive samples with high values and two with low values. Include negative controls [32].

- Replicates: Test each sample in triplicate.

- Duration & Operators: Perform testing over five days with two different analysts [32].

2. Materials and Equipment

- Pre-characterized sample panels (positive and negative).

- All assay reagents (buffers, substrates, etc.).

- calibrated pipettes, incubator, plate reader.

- Data recording sheets or LIMS.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Day 1: Operator 1 prepares all reagents and runs the first batch of triplicates for all samples. Records all raw data and results.

- Day 2-5: Operators 1 and 2 alternate running the assay in triplicate, ensuring independent preparation and execution where applicable.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of results in agreement for each sample level across all runs and operators. The formula is:

(Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) * 100[32]. - Acceptance Criterion: The calculated percentage of agreement should meet or exceed the manufacturer's stated claims or a pre-defined limit set by the laboratory director [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Well-characterized microorganisms or analytes with defined profiles used to validate testing methodologies and ensure accuracy [34]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Organisms | Strains with predictable biochemical reactions used to monitor the performance of test methods, reagents, and operators in routine testing [34]. |

| In-House Isolates | Organisms isolated from the laboratory's own environment or historical samples, critical for ensuring tests are validated against relevant, local strains [34]. |

| Clinical Isolates & Bioburden Samples | De-identified patient samples or product samples used to verify assay performance with real-world matrices and assess microbial load [32] [7]. |

| Proficiency Test (PT) Standards | Commercially provided samples used to benchmark laboratory performance against peers and ensure ongoing compliance and accuracy [34]. |

Best Practices for Inoculum Preparation and Standardization

In microbiological method verification research, the accuracy and reproducibility of results are fundamentally dependent on the quality of the initial inoculum. Inoculum preparation and standardization is a critical preliminary step in antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) and various microbiological assays. Inconsistent or inaccurate inoculum preparation is a frequent, yet often overlooked, source of error that can lead to incorrect Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) determinations, misleading susceptibility categorizations, and ultimately, compromised research conclusions. This guide addresses the core principles and common pitfalls of inoculum preparation to help researchers troubleshoot issues related to low accuracy in their experimental results.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Inoculum: A suspension of microorganisms prepared for introducing into culture media for testing purposes. Inoculum Effect (IE): A phenomenon where the observed MIC of an antimicrobial agent depends on the initial density of bacteria inoculated into the assay [36]. This effect is most pronounced for β-lactam antibiotics against strains expressing β-lactamase enzymes. Colony Forming Unit (CFU): A unit used to estimate the number of viable microorganisms in a sample. McFarland Standard: A scale used to standardize the approximate number of bacteria in a liquid suspension based on turbidity.

FAQs on Inoculum Preparation

Q1: Why is inoculum standardization so critical for antimicrobial susceptibility testing?

The initial density of bacteria in an AST directly influences the outcome, a phenomenon known as the inoculum effect (IE). For certain antibiotic-bacterium combinations, even small variations in the starting inoculum within the acceptable range can lead to major discrepancies in the MIC value. One study demonstrated that for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, each 2-fold reduction in inoculum resulted in a 1.26 log₂-fold reduction in meropenem MIC. This effect can be sufficient to change the categorical interpretation of an isolate from "resistant" to "susceptible," leading to potential errors in research conclusions and their clinical application [36].

Q2: What is the target inoculum density for standard broth microdilution tests?

For reference broth microdilution (BMD) AST, the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) mandates a standardized inoculum density of 5 × 10⁵ CFU/ml, with an allowable range of 2 × 10⁵ to 8 × 10⁵ CFU/ml [36]. Adherence to this range is essential for achieving reproducible and accurate results that are comparable across different laboratories and studies.

Q3: My prepared inoculum suspension is at the correct McFarland turbidity. Why is my final CFU/ml still inaccurate?

Turbidity standards provide an approximation, but several factors can cause a deviation from the expected cell density:

- Temperature Exposure: Exposing the inoculum suspension to increased temperature can lead to cell death or affect the cell division cycle, artificially altering the number of viable cells (CFU) [37].

- Culture Age and Viability: Using an culture that is too old or not in the optimal growth phase can result in a high proportion of non-viable cells, meaning the turbidity reflects both live and dead cells.

- Mixing and Technique: Inadequate mixing of the suspension before sampling or improper serial dilution techniques can lead to inconsistent cell distribution and inaccurate counts [38].

- Organism Characteristics: Clumping or chaining behavior in some bacterial species (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus) means that one colony may not originate from a single cell, making turbidity correlations less reliable.

Q4: What are the best sources for preparing a standardized inoculum?

The source of growth significantly impacts the final viable count. Studies comparing different methods have found that inocula prepared from broth suspensions of organisms harvested from 24- and 48-hour anaerobe blood agar plates yielded the most consistent and highest viable counts across various organisms when adjusted to the 0.5 McFarland standard. This method often produces higher counts than using overnight broth cultures adjusted to the same turbidity [39]. Using overnight agar cultures is an acceptable and often preferred alternative procedure [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Inconsistent Results in Susceptibility Tests

Problem: High variability in MIC readings or zone of inhibition diameters between replicate experiments. Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inoculum density outside the validated range.

- Solution: Consistently use viable count methods (pour or spread plate) to verify the actual CFU/ml of your working suspension, rather than relying solely on turbidity. Store verified dilutions at 2-8°C for short-term use [41].

- Cause: Uncontrolled Inoculum Effect.

- Solution: Be aware that for specific drug-bug combinations (e.g., β-lactams against ESBL-producers), the IE can be pronounced. If erratic results persist, test at both the standard and a higher inoculum to investigate the presence of a significant IE [36].

- Cause: Improper storage and handling of the inoculum.

Guide: Unexpected Quantitative Results in Culture-Based Assays

Problem: Microbial counts on plates are consistently higher or lower than theoretically calculated. Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Errors in serial dilution technique.

- Solution: Use fresh, sterile diluent (e.g., 0.1% peptone saline) for each dilution series. Ensure each dilution tube is mixed thoroughly before transferring to the next. Use a new pipette tip for each transfer to prevent carryover [41].

- Cause: Degradation or quality issues with the culture media.

- Solution: Check the expiry date of the media. Look for signs of degradation like color change, cracking, or excessive moisture. Avoid repeated melting and overheating of agar media, as this can degrade key components and affect growth [38].

- Cause: Incorrect pH of the culture medium.

- Solution: Measure the pH of the medium within the specified temperature range (e.g., 10-37°C) using a properly calibrated pH meter with a suitable electrode. Overheating during sterilization or contaminated water can alter the pH [38].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Inoculum Effect on MIC for Different Antibiotic Classes

| Antibiotic Class | Example Agent | Organism Type | Observed MIC Change with High Inoculum* | Clinical/Risk Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactams (Carbapenems) | Meropenem | Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) | 8.3 ± 1.8 log₂ dilutions (∼315-fold increase) | Major shift; can cause false susceptible (minor error) at low inoculum [36] |

| β-lactams (Cephalosporins) | Cefepime | ESBL-producing E. coli/Klebsiella (Resistant/SDD) | 1.6 log₂-fold increase per 2-fold inoculum increase | Significant shift affecting categorical interpretation [36] |

| β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor | Ceftazidime-Avibactam | CZA-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (non-NDM) | Modest IE (2.9 log₂ difference from highest to lowest inoculum) | Less pronounced effect compared to other β-lactams [36] |

Note: *High inoculum is typically 100-fold greater than the CLSI standard of 5 x 10⁵ CFU/ml, unless otherwise specified. SDD = Susceptible-Dose Dependent.

Table 2: Standardized Inoculum Preparation Protocols for Different Microorganism Types

| Microorganism Type | Recommended Growth Medium | Incubation Conditions | Expected Broth Density | Dilution Method for ~10-100 CFU | Enumeration Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Bacteria | Soybean Casein Digest Broth | 30-35°C for 24 hours | ~10⁹ CFU/ml | Serial dilution in 0.1% peptone saline [41] | Pour Plate or Spread Plate [41] |

| Anaerobic Bacteria | Cooked Meat Medium | 30-35°C for 24-48 hours | ~10⁸ CFU/ml | Serial dilution in 0.1% peptone saline [41] | Pour Plate (anaerobic conditions) |

| Yeast | Soybean Casein Digest Broth | 20-25°C for 48-72 hours | ~10⁸ CFU/ml | Serial dilution in 0.1% peptone saline [41] | Spread Plate |

| Mold | Soybean Casein Digest Broth | 30-35°C for 120 hours | ~10⁸ CFU/ml | Serial dilution in 0.1% peptone saline [41] | Spread Plate |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Inoculum Preparation and Standardization by Direct Colony Suspension

This is a standard method for preparing an inoculum from fresh agar plates.

Principle: To create a standardized suspension of microorganisms directly from isolated colonies on an agar plate, adjusted to a specific turbidity, which can then be diluted to the precise density required for testing [40] [41] [39].

Materials:

- Working culture slants or plates (18-24 hours old for bacteria; 48-72 hours for yeast)

- Sterile saline, phosphate-buffered saline, or 0.1% peptone water

- McFarland 0.5 turbidity standard or a photometric device

- Sterile swabs or inoculation loops

- Sterile test tubes

- Vortex mixer

- Spectrophotometer (optional, for precise turbidity)

Procedure:

- Harvest Colonies: Using a sterile loop or swab, gently select several well-isolated colonies of similar morphology from the agar plate.

- Prepare Initial Suspension: Transfer the colonies into a tube containing sterile saline or peptone water.

- Vortex: Vortex the suspension vigorously for 15-30 seconds to achieve a smooth, homogenous suspension without clumps.

- Adjust Turbidity: Compare the suspension's turbidity against the McFarland 0.5 standard under good light. Add more bacteria or diluent until the turbidity matches the standard. This results in a suspension of approximately 1-2 x 10⁸ CFU/ml for most bacteria.