The Prokaryotic Pan-Genome and Core Genome: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of prokaryotic pan-genome and core genome concepts, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Prokaryotic Pan-Genome and Core Genome: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of prokaryotic pan-genome and core genome concepts, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It begins by establishing foundational principles, including the definitions of core, accessory, and strain-specific genes, and the critical distinction between open and closed pan-genomes. The content then progresses to methodological approaches, detailing the latest bioinformatics tools and pipelines for pan-genome inference, and showcases their practical applications in vaccine development, antimicrobial discovery, and tracking antimicrobial resistance. The article further addresses common analytical challenges and optimization strategies for handling large-scale genomic datasets, and concludes with a comparative evaluation of current software and validation techniques. By synthesizing established knowledge with cutting-edge advancements, this review serves as a vital resource for leveraging pan-genomics to answer pressing questions in microbial evolution and clinical research.

Deconstructing the Prokaryotic Pan-Genome: Core, Accessory, and Unique Genes

The pan-genome represents the entire set of genes found across all individuals within a clade or species, capturing the complete genetic repertoire beyond what is present in any single organism [1] [2]. This concept was formally defined in 2005 by Tettelin et al. through their groundbreaking work on Streptococcus agalactiae, which revealed that a single genome sequence fails to capture the full genetic diversity within a bacterial species [1] [3]. The pan-genome is partitioned into distinct components: the core genome containing genes shared by all individuals, the shell genome comprising genes present in multiple but not all individuals, and the cloud genome (also called accessory or dispensable genome) consisting of genes unique to single strains [1] [4]. This classification provides a critical framework for understanding genomic dynamics, particularly in prokaryotes where horizontal gene transfer significantly shapes genetic diversity [5].

The fundamental value of pan-genome analysis lies in its ability to reveal the complete genetic potential of a species, moving beyond the limitations of single reference genomes that often obscure biologically significant variation [3] [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this comprehensive perspective enables more accurate associations between genetic elements and phenotypic traits, including pathogenicity, antimicrobial resistance, and metabolic capabilities [5] [6]. The pan-genome concept has evolved from its prokaryotic origins to find application in eukaryotic species, including plants and humans, revolutionizing our approach to studying genetic diversity and its functional implications across the tree of life [3] [7].

Core, Shell, and Cloud Genomes: Components and Functional Significance

The architectural division of the pan-genome into core, shell, and cloud components provides critical insights into the evolutionary pressures and functional specialization within bacterial species. Each compartment exhibits distinct evolutionary patterns and functional associations that reflect their differential importance for bacterial survival, adaptation, and niche specialization.

Table 1: Characteristics of Pan-Genome Components

| Component | Definition | Typical Functional Associations | Evolutionary Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Genome | Genes present in 100% of strains [1] | Housekeeping functions, primary metabolism, essential cellular processes [1] | Highly conserved, vertical inheritance, slow evolution |

| Shell Genome | Genes shared by majority (e.g., 50-95%) of strains [1] | Niche adaptation, metabolic specialization | Intermediate conservation, partial selection |

| Cloud Genome | Genes present in minimal subsets or single strains [1] | Ecological adaptation, stress response, antimicrobial resistance [1] | Rapid turnover, horizontal gene transfer |

The core genome represents the genetic backbone of a species, encoding functions so essential that their loss would be lethal or severely disadvantageous under most conditions [1]. While often conceptualized as comprising 100% of strains, some implementations use thresholds such as >95% for a "soft core" to account for annotation errors or genuine biological variation [1]. Core genes are frequently employed for phylogenetic reconstruction and molecular typing due to their stable presence across the species [6].

The shell genome occupies an intermediate position, containing genes that provide selective advantages in specific environments but are not universally essential. These genes may represent transitions in evolutionary trajectory—either recent acquisitions moving toward fixation or former core genes being lost from some lineages [1]. For instance, the tryptophan operon in Actinomyces shows a shell distribution pattern due to lineage-specific gene losses [1].

The cloud genome (accessory genome) demonstrates the most dynamic evolutionary pattern, characterized by rapid gain and loss through horizontal gene transfer [1] [5]. This component often contains genes associated with mobile genetic elements, including plasmids, phages, and transposons, which facilitate rapid adaptation to new environmental challenges [5]. While sometimes described as "dispensable," this terminology has been questioned as these genes frequently play crucial roles in niche specialization and environmental interaction [1].

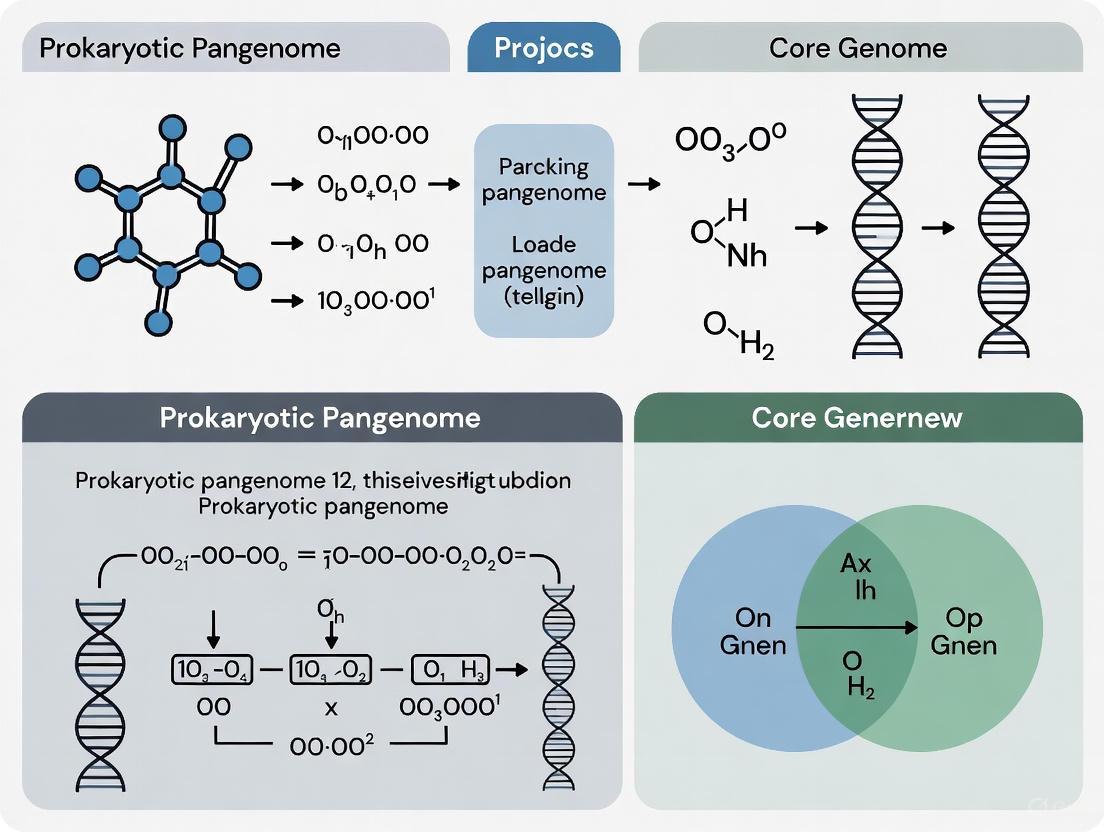

Figure 1: Pan-Genome Components and Their Characteristics. The diagram illustrates the three main compartments of the pan-genome and their representative functional associations.

Quantitative Analysis of Pan-Genome Dynamics

The classification of pan-genomes as "open" or "closed" provides a quantitative framework for understanding the genetic diversity and evolutionary trajectory of bacterial species. This distinction is formally characterized using Heaps' law, which models the relationship between newly sequenced genomes and the discovery of novel genes [1]. The formula ( N = kn^{-\alpha} ) describes this relationship, where ( N ) represents the number of new genes discovered, ( n ) is the number of genomes sequenced, ( k ) is a constant, and ( \alpha ) is the exponent determining the pan-genome type [1]. When ( \alpha \leq 1 ), the pan-genome is considered open, indicating that each additional genome continues to contribute substantial novel genetic material [1]. Conversely, when ( \alpha > 1 ), the pan-genome is closed, signifying that new genomes contribute diminishing returns in terms of novel gene discovery [1].

Table 2: Open vs. Closed Pan-Genome Characteristics

| Feature | Open Pan-Genome | Closed Pan-Genome |

|---|---|---|

| Heaps' Law α value | α ≤ 1 [1] | α > 1 [1] |

| New genes per additional genome | Continues to add significant novel genes [1] | Few new genes added [1] |

| Theoretical size | Difficult or impossible to predict [1] | Asymptotically predictable [1] |

| Typical ecological associations | Large population size, niche versatility [1] | Specialists, parasitic lifestyle [1] |

| Representative species | Escherichia coli (89,000 gene families from 2,000 genomes) [1] | Staphylococcus lugdunensis [1] |

Empirical studies demonstrate remarkable variation in pan-genome sizes across bacterial species. Escherichia coli, a species with an open pan-genome, exhibits approximately 4,000-5,000 genes per individual strain but encompasses approximately 89,000 different gene families across 2,000 genomes [1]. In contrast, Streptococcus pneumoniae displays a closed pan-genome where the discovery of new genes effectively plateaus after sequencing approximately 50 genomes [1]. Recent research has expanded these concepts to eukaryotic systems; a peanut pangenome study identified 17,137 core, 5,085 soft-core, 22,232 distributed, and 5,643 private gene families across eight high-quality genomes [7].

The determination of pan-genome openness has significant implications for research strategies. Species with open pan-genomes require substantially greater sampling efforts to capture their full genetic repertoire, while closed pan-genomes can be effectively characterized with fewer sequenced genomes [1]. Population size and niche versatility have been identified as key factors influencing pan-genome size, with generalist species typically exhibiting more open pan-genomes than specialist or parasitic species [1].

Methodological Framework for Pan-Genome Analysis

The computational reconstruction of pan-genomes requires sophisticated bioinformatics workflows that integrate multiple analytical steps from data acquisition to final visualization. Current methodologies can be broadly categorized into reference-based, phylogeny-based, and graph-based approaches, each with distinct strengths and limitations [8]. The emergence of integrated software suites has significantly streamlined this process, enabling researchers to conduct comprehensive analyses even for large datasets comprising thousands of genomes [8].

PGAP2: A Modern Analytical Pipeline

The PGAP2 pipeline represents a state-of-the-art approach for prokaryotic pan-genome analysis, employing a four-stage workflow that encompasses data reading, quality control, homologous gene partitioning, and post-processing analysis [8]. This toolkit addresses critical challenges in large-scale pan-genomics by implementing fine-grained feature analysis within constrained regions, enabling more accurate identification of orthologous and paralogous genes compared to previous tools [8].

The quality control module in PGAP2 implements sophisticated outlier detection using both Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) similarity thresholds and comparisons of unique gene counts between strains [8]. Strains exhibiting ANI similarity below 95% to the representative genome or possessing anomalously high numbers of unique genes are flagged as potential outliers [8]. Following quality control, the ortholog inference engine constructs dual networks—a gene identity network and a gene synteny network—to resolve homologous relationships through a dual-level regional restriction strategy [8]. This approach significantly reduces computational complexity while maintaining analytical precision.

Gene Family Clustering and Orthology Determination

The core computational challenge in pan-genome analysis involves accurate clustering of genes into orthologous groups. The MICFAM (MicroScope gene families) framework exemplifies this process using a single-linkage clustering algorithm implemented in the SiLiX software [4]. This approach operates on the principle that "the friends of my friends are my friends," clustering genes that share amino-acid alignment coverage and identity above defined thresholds [4]. Typical parameter sets include stringent (80% identity, 80% coverage) and permissive (50% identity, 80% coverage) thresholds, allowing researchers to balance precision and sensitivity according to their research goals [4].

Figure 2: Computational Workflow for Pan-Genome Analysis. The diagram outlines key steps in modern pan-genome analysis pipelines, highlighting the iterative process of ortholog inference.

Orthology determination represents a particularly challenging aspect, as algorithms must distinguish between true orthologs (genes separated by speciation events) and paralogs (genes related by duplication events) [8] [6]. PGAP2 addresses this through a three-criteria evaluation system assessing gene diversity, gene connectivity, and application of the bidirectional best hit (BBH) criterion to duplicate genes within the same strain [8]. This multi-faceted approach significantly improves the accuracy of orthologous cluster identification, particularly for rapidly evolving gene families.

Essential Research Tools and Reagents for Pan-Genome Studies

The successful implementation of pan-genome research requires a comprehensive toolkit encompassing computational resources, specialized software, and curated databases. These resources enable researchers to navigate the complex workflow from raw sequence data to biological insights.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Pan-Genome Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGAP2 [8] | Integrated Pipeline | Pan-genome analysis with quality control and visualization | Prokaryotic pan-genome construction from large datasets (thousands of genomes) |

| Roary [8] | Gene Clustering | Rapid large-scale pan-genome analysis | Standardized prokaryotic pan-genome workflows |

| Panaroo [8] [5] | Gene Clustering | Error-aware pan-genome analysis with graph-based methods | Identification/correction of annotation errors in prokaryotic datasets |

| Prokka [8] | Genome Annotation | Rapid annotation of prokaryotic genomes | Consistent gene calling and functional prediction |

| Bakta [5] | Genome Annotation | Database-driven rapid and consistent annotation | High-quality, standardized genome annotations |

| vg toolkit [9] | Graph Construction | Creation and manipulation of genome variation graphs | Graph-based pangenome representation and analysis |

| ODGI [9] | Graph Manipulation | Optimization, visualization, and interrogation of genome graphs | Handling large pangenome graphs |

| Seqwish [9] | Graph Induction | Variation graph induction from sequences and alignments | Efficient graph construction from genome collections |

| SiLiX [4] | Gene Family Clustering | Single-linkage clustering of homologous genes | Orthology detection and gene family construction |

The selection of appropriate tools must align with research objectives and data characteristics. Reference-based methods such as eggNOG and COG provide efficiency for well-annotated taxa but perform poorly for novel species [8]. Phylogeny-based methods offer robust evolutionary inference but face computational constraints with large datasets [8]. Graph-based approaches excel at capturing structural variation but may struggle with highly diverse accessory genomes [8]. Emerging methodologies such as metapangenomics integrate environmental metagenomic data with reference genomes, enabling researchers to contextualize gene distribution patterns within ecological frameworks [1].

Quality control remains paramount throughout the analytical process, as errors in gene annotation and clustering significantly impact downstream interpretations [5] [6]. Fragmented assemblies often inflate singleton counts and artificially expand pan-genome size estimates [6]. Tools such as Panaroo and PGAP2 implement error-correction mechanisms that identify fragmented genes, missing annotations, and contamination events, substantially improving result accuracy [8] [5].

Research Applications and Future Directions

Pan-genome analysis has transcended its initial application in bacterial genomics to become a cornerstone approach across diverse biological disciplines. In clinical microbiology, pan-genome studies facilitate the identification of virulence factors, antimicrobial resistance genes, and vaccine targets by distinguishing core conserved elements from strain-specific adaptations [5] [6]. Agricultural research has leveraged pan-genomics to uncover agronomically important genes frequently located in the dispensable genome, enabling crop improvement through identification of valuable traits absent from reference sequences [3] [7].

A landmark peanut pangenome study exemplifies the power of this approach, identifying 1,335 domestication-related structural variations and 190 variations associated with seed size and weight [7]. Functional characterization revealed that a 275-bp deletion in the gene AhARF2-2 disrupts interaction with AhIAA13 and TOPLESS, reducing inhibitory effects on AhGRF5 and consequently promoting seed expansion [7]. This finding demonstrates how pan-genome analysis can connect structural variations to phenotypic traits of economic importance.

In human genomics, graph-based pan-genome representations are addressing critical limitations of linear reference genomes, which poorly capture genetic diversity in underrepresented populations [10]. Recent research demonstrates that variation graphs significantly improve the accuracy of effective population size estimates in Middle Eastern Bedouin populations compared to the standard hg38 reference [10]. This approach reduces reference bias and enables more equitable genomic medicine by better capturing global genetic diversity.

Future developments in pan-genomics will likely focus on enhanced visualization tools, standardized analysis protocols, and integration with multi-omics datasets. Current challenges include the development of computationally efficient methods for eukaryotic pan-genome construction, improved annotation of intergenic regions, and standardized classification of paralogous genes [5] [6]. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and datasets expand, pan-genome analysis will remain an indispensable approach for comprehensively characterizing species' genetic diversity and its functional consequences.

The core genome comprises the set of genes shared by all individuals within a studied population or species, representing the fundamental genetic blueprint that defines a taxonomic group [8]. This concept is central to prokaryotic pangenome research, which classifies the entire gene repertoire of a species into three components: the core genome (shared by all strains), the accessory genome (present in some strains), and the unique genes (specific to single strains) [8]. The core genome is particularly valuable for understanding essential bacterial functions and establishing robust phylogenetic relationships because these genes are vertically inherited and undergo limited horizontal gene transfer [11].

Molecular analyses of conserved sequences reveal that the universal core genes predominantly encode proteins involved in central information processing mechanisms. Most of these genes interact directly with the ribosome or participate in genetic information transfer, forming the ancestral genetic core of cellular life that traces back to the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) [11]. This evolutionary conservation makes the core genome particularly valuable for understanding essential bacterial functions and establishing robust phylogenetic relationships.

Essential Functions of the Core Genome

Universal Gene Families and Cellular Functions

Research analyzing universally conserved genes across the three domains of life (Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya) has identified a small set of approximately 50 genes that share the same phylogenetic pattern as ribosomal RNA and can be traced back to the universal ancestor [11]. These genes constitute the genetic core of cellular organisms and are overwhelmingly involved in transfer of genetic information.

Table 1: Functional Classification of Universal Core Genes

| Functional Category | Number of Genes | Primary Functions | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal Proteins & Translation Factors | 29 + 4 factors | Protein synthesis, ribosomal structure | rpsL, rpsG, rplK, rplA, elongation factors [11] |

| Transcription & Replication | 8 | DNA replication, RNA transcription, aminoacylation | rpoB, rpoC, trpS, recA, dnaN [11] |

| Ribosome-Associated Proteins | 6 | Protein targeting, secretion, metabolism | secY, ffh, ftsY, map, glyA [11] |

| Proteins of Unknown Function | 2 | Unknown fundamental cellular processes | ychF, mesJ [11] |

The predominance of translation-related proteins in the core genome highlights the evolutionary ancient nature of the protein synthesis machinery. Of the 80 universally present COGs (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) identified across all cellular life, 37 are physically associated with the ribosome in modern cells, with most of the remaining universal genes involved in transcription, replication, or other information-processing activities [11].

Core Genome in Pathogen Surveillance and Epidemiology

In clinical microbiology, the core genome provides the foundation for highly discriminatory typing methods like core genome Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (cgMLST). This approach indexes variations in hundreds to thousands of core genes, offering superior resolution for epidemiological investigations compared to traditional methods that examine only 5-7 housekeeping genes [12] [13].

Studies on Pseudomonas aeruginosa have demonstrated that cgMLST correlates strongly with SNP-based phylogenetic analysis (R² = 0.92-0.99), making it a reliable tool for outbreak investigation [13]. Epidemiologically linked isolates typically show 0-13 allele differences in cgMLST analysis, providing a clear threshold for distinguishing outbreak-related strains from unrelated isolates [12] [13]. This precision makes core genome analysis particularly valuable for healthcare-associated infection surveillance and understanding transmission dynamics in hospital settings [14].

Quantitative Analysis of Essential Genes

Essential Gene Content Across Bacterial Species

Systematic studies using transposon mutagenesis and targeted gene deletions have quantified essential genes across diverse bacterial species. Essential genes are defined as those indispensable for growth and reproduction under specific environmental conditions, though this definition is context-dependent [15].

Table 2: Essential Gene Statistics Across Bacterial Species

| Organism | Total ORFs | Essential Genes | Percentage Essential | Primary Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma genitalium | 482 | 265-382 | 55%-79% | Transposon mutagenesis [15] |

| Escherichia coli K-12 | 4,308 | 620 | 14% | Transposon footprinting [15] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 3,989 | 614-774 | 15%-19% | Transposon sequencing [15] |

| Bacillus subtilis | 4,105 | 261 | 7% | Targeted deletion [15] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2,600-2,892 | 168-658 | 6%-23% | Transposon mutagenesis [15] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 5,570-5,688 | 335-678 | 6%-12% | Transposon sequencing [15] |

The variation in essential gene numbers reflects both biological differences and methodological approaches. Bacteria with smaller genomes like Mycoplasma species have higher percentages of essential genes, while those with larger genomes have more genetic redundancy. The experimental method also influences results—transposon mutagenesis may identify conditionally essential genes, while targeted deletion provides more definitive essentiality data [15].

Functional Categories of Essential Genes

Single-celled organisms primarily rely on essential genes encoding proteins for three basic functions: genetic information processing, cell envelope formation, and energy production [15]. These functions maintain central metabolism, DNA replication, gene translation, basic cellular structure, and transport processes. In contrast to viruses, which lack essential metabolic genes, bacteria require a core set of metabolic genes for autonomous survival [15].

Experimental Methodologies for Core Genome Analysis

Determining Gene Essentiality

Two primary strategies are employed to identify essential genes on a genome-wide scale:

Directed Gene Deletion This method involves systematically deleting annotated individual genes or open reading frames (ORFs) from the genome [15]. The process includes:

- Designing deletion constructs with selectable markers flanked by sequences homologous to the target gene

- Transforming the constructs into the bacterial strain

- Selecting for successful deletion mutants

- Verifying deletions through PCR and sequencing

- Testing the resulting mutants for viability and growth defects under standard conditions

Random Mutagenesis Using Transposons This approach involves random insertion of transposons into as many genomic positions as possible to disrupt gene function [15]:

- Generating mutant libraries through transposon delivery

- Selecting viable mutants under optimal growth conditions

- Identifying insertion sites through hybridization to microarrays or transposon sequencing (Tn-seq)

- Mapping insertion sites to determine which genes tolerate disruptions

- Classifying genes with no insertions as potentially essential

More recently, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) has been employed to inhibit gene expression and assess essentiality without altering the DNA sequence [15].

Figure 1: Computational workflow for core genome analysis, illustrating key steps from quality control to ortholog identification [8].

Computational Approaches for Core Genome Identification

PGAP2 Pipeline Methodology The PGAP2 toolkit implements a comprehensive workflow for core genome analysis through four successive steps [8]:

Data Reading and Validation

- Input acceptance in multiple formats (GFF3, genome FASTA, GBFF)

- Format identification based on file suffixes

- Organization of input data into structured binary files

Quality Control and Visualization

- Representative genome selection based on gene similarity

- Outlier identification using Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) thresholds

- Generation of interactive HTML reports for codon usage, genome composition, and gene completeness

Homologous Gene Partitioning

- Construction of gene identity and synteny networks

- Application of dual-level regional restriction strategy to reduce search complexity

- Orthologous gene inference using three reliability criteria: gene diversity, gene connectivity, and bidirectional best hit (BBH)

Postprocessing and Visualization

- Generation of rarefaction curves and homologous cluster statistics

- Application of distance-guided construction algorithm for pan-genome profiles

- Integration with phylogenetic tree construction and population clustering tools

Core Genome Scheme Comparison Different methods exist for defining core genomes in comparative analyses [14]:

- Conserved-gene core genome: Uses housekeeping genes identified through comparison of publicly available genomes

- Conserved-sequence core genome: Selects conserved sequences in the reference genome by comparing k-mer content across assemblies

- Intersection core genome: Computes SNV distances across nucleotides unambiguously determined in all samples (problematic for prospective studies)

The conserved-sequence approach demonstrates better performance in distinguishing same-patient samples, with higher sensitivity in confirming outbreak samples (44/44 known outbreaks detected versus 38/44 with conserved-gene method) [14].

Research Reagent Solutions for Core Genome Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Core Genome Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Transposon Mutagenesis Libraries | Genome-wide identification of essential genes through random insertion mutations [15] | Identification of 620 essential genes in E. coli K-12 [15] |

| CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) | Targeted gene repression for essentiality testing without DNA alteration [15] | Essentiality screening in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [15] |

| PGAP2 Software Toolkit | Pan-genome analysis pipeline with ortholog identification and visualization [8] | Analysis of 2,794 Streptococcus suis strains [8] |

| BioNumerics cgMLST | Commercial software for core genome MLST analysis and outbreak investigation [12] [13] | Pseudomonas aeruginosa outbreak analysis in hospital settings [13] |

| Roary/Panaroo | Rapid large-scale pan-genome analysis tools for ortholog clustering [8] | Comparative genomics of bacterial populations [8] |

| Conserved-Sequence Genome Method | Sample set-independent core genome definition using k-mer conservation [14] | Prospective monitoring of S. aureus transmissions [14] |

The core genome represents the fundamental genetic foundation shared across bacterial strains, encoding essential functions primarily related to information processing, translation, and central metabolism. Through both experimental and computational methodologies, researchers can delineate this core genome to understand essential biological processes, track bacterial evolution, and investigate disease outbreaks. Quantitative analyses reveal that typically 5-20% of genes in bacterial genomes are essential, with substantial variation across species. As pan-genome research evolves, the core genome continues to provide critical insights for comparative genomics, phylogenetic studies, and clinical epidemiology, serving as an anchor point for understanding both universal biological functions and adaptive specialization in prokaryotic organisms.

In the fields of genomics and molecular biology, the pangenome represents a comprehensive framework that captures the total repertoire of genes found across all strains within a clade or species [1]. This concept arose from the recognition that a single reference genome cannot capture the full genetic diversity of a species [16]. The pangenome is partitioned into two primary components: the core genome, which comprises genes shared by all individuals, and the accessory genome, which contains genes present in some but not all individuals [1] [17]. The accessory genome is further categorized into shell and cloud genes based on their frequency of occurrence across strains [1] [16]. This classification provides critical insights into evolutionary dynamics, niche adaptation, and functional specialization [1].

The pioneering work by Tettelin et al. in 2005 first established the pangenome concept through analysis of Streptococcus agalactiae isolates, revealing that each newly sequenced strain contributed unique genes to the overall gene pool [1]. This finding fundamentally challenged the notion that a single genome could represent a species' entire genetic content. Subsequent research has demonstrated that the proportion of accessory genomes varies significantly across microbial species, influenced by factors including population size, niche versatility, and evolutionary history [1] [17]. Species with extensive horizontal gene transfer typically maintain open pangenomes, where new genes continue to be discovered with each additional sequenced genome, while species with closed pangenomes quickly reach a plateau in gene discovery [1] [16].

Defining the Shell and Cloud Genomes

The Shell Genome

The shell genome constitutes the intermediate frequency component of the accessory genome, consisting of genes present in a majority but not all strains of a species [1] [16]. While no universal threshold exists, most studies classify genes with presence in 15% to 95% of strains as shell genes [16]. These genes often encode functions related to environmental adaptation, including transporters, surface proteins, and specialized metabolic pathways that enable specific groups to thrive in particular niches [16]. The dynamic nature of shell genes reflects their role in bacterial evolution, where they may represent genes on their way to fixation in the population or genes being lost through reductive evolutionary processes [1].

Shell genes can originate through two primary evolutionary pathways: (1) gene loss in a lineage where the gene was previously part of the core genome, or (2) gene gain and fixation of a gene that was previously part of the dispensable genome [1]. For example, in Actinomyces, enzymes in the tryptophan operon have been lost in specific lineages, transitioning from core to shell genes, while in Corynebacterium, the trpF gene has been gained and fixed in multiple lineages, transitioning from cloud to shell status [1]. This fluidity makes the shell genome a dynamic interface between the highly conserved core and the highly variable cloud genome.

The Cloud Genome

The cloud genome represents the most variable component of the accessory genome, encompassing genes present in only a minimal subset of strains, typically less than 15% of the population [16]. This category includes singletons – genes found exclusively in a single strain [1]. Cloud genes are often associated with recent horizontal acquisition through mobile genetic elements, including phages, plasmids, and transposons [1]. While sometimes described as 'dispensable,' this terminology has been questioned as cloud genes frequently encode functions critical for ecological adaptation and survival under specific conditions [1] [18].

Functional analyses consistently reveal that cloud genes are enriched for activities related to environmental sensing, stress response, and niche-specific adaptation [1] [19]. In barley, for instance, cloud genes are significantly enriched for stress response functions, demonstrating their conditional importance despite their limited distribution [18] [19]. The phenomenon of "conditional dispensability" describes situations where cloud genes become essential under specific environmental stresses, even though they may be unnecessary under standard laboratory conditions [18]. This highlights the ecological relevance of cloud genes and their role in evolutionary innovation.

Quantitative Analysis of Shell and Cloud Genomes

Statistical Distribution Across Species

The relative proportions of core, shell, and cloud genomes vary substantially across bacterial species, reflecting their distinct evolutionary histories and ecological strategies. Table 1 summarizes the pangenome characteristics and shell/cloud distributions for several prokaryotic species as revealed by recent genomic studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Distribution of Shell and Cloud Genes Across Prokaryotic Species

| Species | Total Gene Families | Core Genome (%) | Shell Genome (%) | Cloud Genome (%) | Pangenome Status | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex | ~4,000-5,000 per genome | ~76% | Not specified | Not specified | Closed | [17] |

| Acinetobacter baumannii (Asian clinical isolates) | Not specified | 5.34-10.68% | Not specified | Not specified | Open | [20] |

| Streptococcus suis (2,794 strains) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | [8] |

| Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | 79,600 | 21.85% | 40.47% | 37.68% | Not specified | [18] |

Functional Enrichment Patterns

Comparative functional analyses reveal distinct enrichment patterns between shell and cloud genes. Table 2 summarizes the characteristic functional categories associated with each genomic compartment based on Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses from multiple studies.

Table 2: Functional Enrichment in Shell vs. Cloud Genomes

| Genomic Compartment | Enriched Functional Categories | Biological Examples | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shell Genome | Transporters, surface proteins, metabolic modules, defense response | Stress response genes in barley; Metabolic adaptation in Mycobacterium abscessus | [16] [19] [21] |

| Cloud Genome | Stress response, niche-specific adaptation, mobile genetic elements, conditional essentials | Biotic/abiotic stress responses in barley; Antibiotic resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii | [18] [19] [20] |

| Core Genome | DNA replication, transcription, translation, primary metabolism | Ribosomal proteins, DNA polymerase, essential metabolic enzymes | [16] [19] |

The functional specialization evident in these compartments reflects their distinct evolutionary roles. Core genes maintain essential cellular functions, shell genes facilitate adaptation to common environmental variations, and cloud genes provide capabilities for niche-specific challenges and evolutionary innovation [16] [19].

Methodologies for Shell and Cloud Genome Analysis

Pangenome Construction Workflow

The accurate identification and classification of shell and cloud genes requires a systematic bioinformatic workflow. The following diagram illustrates the standard pipeline for pangenome construction and analysis:

Figure 1: Pangenome Analysis Workflow. The standard bioinformatics pipeline for constructing pangenomes and classifying genes into core, shell, and cloud compartments.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Genome Annotation and Orthology Clustering

The foundation of accurate shell and cloud classification lies in consistent gene annotation and orthology inference. Modern pangenome analysis tools like PGAP2 employ sophisticated algorithms that combine sequence similarity and genomic synteny to identify orthologous genes [8]. The process involves:

Data Abstraction: PGAP2 organizes input data into two distinct networks: a gene identity network (where edges represent similarity between genes) and a gene synteny network (where edges denote adjacent genes) [8].

Feature Analysis: The algorithm applies a dual-level regional restriction strategy, evaluating gene clusters within predefined identity and synteny ranges to reduce computational complexity while maintaining accuracy [8].

Orthology Inference: Orthologous clusters are identified by traversing all subgraphs in the identity network while applying three reliability criteria: (1) gene diversity, (2) gene connectivity, and (3) the bidirectional best hit (BBH) criterion for duplicate genes within the same strain [8].

For the specific case of Mycobacterium abscessus analysis, researchers typically employ the following protocol:

- Assembly: Draft genomes are assembled using SPAdes in careful mode with read correction and automatic k-mer sizing [21].

- Annotation: Genomes are annotated using Prokka to identify protein-coding genes [21].

- Pangenome Construction: The pangenome is reconstructed using Panaroo in "clean mode" set to "moderate" to handle potential annotation errors [21].

- Frequency Classification: Genes are classified based on their distribution across strains using standard thresholds (core: >95%, shell: 15-95%, cloud: <15%) [16] [21].

Gene Presence-Absence Variation Analysis

The identification of shell and cloud genes fundamentally relies on detecting presence-absence variations (PAVs) across genomes. The following protocol is adapted from multiple recent studies:

Input Data Preparation:

Orthologous Gene Cluster Identification:

Frequency-Based Classification:

- Calculate the prevalence of each gene cluster across all strains

- Apply standard thresholds: core (>95%), shell (15-95%), cloud (<15%) [16]

- Generate a presence-absence matrix for downstream analysis

Functional Validation:

- Perform Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis using tools like topGO or clusterProfiler

- Identify statistically overrepresented functional categories in shell and cloud compartments [19]

- Validate findings through experimental approaches when feasible

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pangenome Analysis

| Reagent/Software | Function | Application Example | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prokka | Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation | Gene prediction in Acinetobacter baumannii pangenome study | [20] [21] |

| PGAP2 | Orthology clustering and pangenome analysis | Identification of core and accessory genes in Streptococcus suis | [8] |

| Roary/Panaroo | Rapid large-scale prokaryotic pangenome analysis | Pangenome construction of Mycobacterium abscessus clinical isolates | [21] |

| FastANI | Average Nucleotide Identity calculation | Genome similarity assessment in quality control | [21] |

| ABRicate | Antimicrobial resistance gene identification | Detection of resistance genes in accessory genome | [20] |

| CheckM | Assess genome completeness and contamination | Quality control of genome assemblies | [21] |

Biological Significance and Research Applications

Evolutionary Dynamics

The shell and cloud genomes serve as dynamic reservoirs of genetic innovation that drive bacterial evolution and adaptation. In the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC), the accessory genome is primarily shaped by genome reduction through divergent and convergent deletions, creating lineage-specific regions of difference (RDs) that influence virulence, drug resistance, and metabolic capabilities [17]. This reductive evolution contrasts with organisms like Mycobacterium abscessus, where recombination and horizontal gene transfer contribute significantly to accessory genome diversity [21].

The evolutionary trajectory of shell and cloud genes can be tracked using tools like Panstripe, which applies generalized linear models to compare phylogenetic branch lengths with gene gain and loss events [21]. Recent studies of M. abscessus have revealed that coordinated gain and loss of accessory genes contributes to different metabolic profiles and adaptive capabilities, particularly in response to oxidative stress and antibiotic exposure [21]. This dynamic nature of the accessory genome enables rapid bacterial adaptation to changing environmental conditions and therapeutic interventions.

Clinical and Pharmaceutical Implications

In clinical microbiology and drug development, understanding shell and cloud genomes provides critical insights into pathogen evolution and antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. Studies of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii have demonstrated that newly emerging resistance genes (including blaNDM-1, blaOXA-58, and blaPER-7) frequently reside in the accessory genome, particularly the cloud compartment [20]. Similarly, in Mycobacterium abscessus, 24 accessory genes have been identified whose gain or loss may increase the likelihood of macrolide resistance [21]. These genes are involved in diverse processes including biofilm formation, stress response, virulence, biotin synthesis, and fatty acid metabolism [21].

The conservation of virulence factors across lineages further highlights the importance of accessory genome analysis. In A. baumannii, key virulence genes involved in biofilm formation, iron acquisition, and the Type VI Secretion System (T6SS) remain conserved despite reductions in overall genetic diversity, indicating their fundamental role in pathogenicity [20]. This understanding directly informs drug discovery efforts by identifying potential targets that are either lineage-specific for narrow-spectrum approaches or conserved across strains for broad-spectrum interventions.

Agricultural and Biotechnological Applications

Beyond clinical applications, shell and cloud genome analysis has proven valuable in agricultural genomics and crop improvement. The barley pan-transcriptome study revealed that shell and cloud genes, previously classified as 'dispensable,' are significantly enriched for stress response functions [18] [19]. This phenomenon of "conditional dispensability" means these genes become essential under specific environmental conditions, providing a genetic reservoir for adaptation to abiotic and biotic stresses [18].

Network analyses of the barley pan-transcriptome identified 12,190 core orthologs that exhibited contrasting expression across genotypes, forming 738 co-expression modules organized into six communities [18]. This genotype-specific expression divergence demonstrates how regulatory variation in conserved genes can contribute to phenotypic diversity. Furthermore, copy-number variation (CNV) in stress-responsive genes like CBF2/4 correlates with elevated basal expression, potentially enhancing frost tolerance [18]. These insights enable more precise molecular breeding strategies that leverage natural variation in shell and cloud genes to develop improved crop varieties.

The classification and analysis of shell and cloud genomes represent a critical advancement in our understanding of prokaryotic evolution and diversity. These components of the accessory genome, once considered merely 'dispensable,' are now recognized as essential reservoirs of genetic innovation that drive adaptation, specialization, and evolutionary success. Through sophisticated bioinformatic tools and comparative genomic approaches, researchers can now systematically identify and characterize these genetic elements across diverse species, from bacterial pathogens to crop plants. The functional enrichment of shell and cloud genes in stress response, niche adaptation, and antimicrobial resistance highlights their practical significance in addressing pressing challenges in human health, agriculture, and biotechnology. As pangenome approaches continue to evolve, incorporating long-read sequencing, graph-based references, and multi-omics integration, our ability to decipher the complex functional and evolutionary dynamics of shell and cloud genomes will further enhance, providing unprecedented insights into the fundamental principles of biological diversity.

The pan-genome represents a transformative concept in genomics that captures the total complement of genes across all individuals within a species or clade, moving beyond the limitations of single reference genomes [1] [16]. First defined by Tettelin et al. in 2005 through studies of Streptococcus agalactiae, the pan-genome comprises both the core genome shared by all strains and the accessory genome that varies between strains [1] [22]. This framework has revealed that the genetic repertoire of a bacterial species often far exceeds the gene content of any single strain, with profound implications for understanding genetic diversity, evolutionary dynamics, and niche adaptation [1].

The pan-genome is conceptually divided into distinct layers based on gene distribution patterns [1] [16]. The core genome contains genes present in all individuals and typically encompasses essential cellular functions and primary metabolism [1]. The accessory genome includes genes present in some but not all strains, further categorized as shell genes (found in most strains) and cloud genes (rare or strain-specific) [1]. This classification provides critical insights into the evolutionary forces shaping bacterial populations and their adaptive capabilities [16].

Defining Open and Closed Pan-Genomes

Mathematical Framework and Classification

Pan-genomes are formally classified as open or closed based on their behavior as additional genomes are sequenced, quantified using Heaps' law with the formula ( N = kn^{-\alpha} ) [1]. In this equation, ( N ) represents the expected number of new gene families, ( n ) is the number of sequenced genomes, ( k ) is a constant, and ( \alpha ) is the key parameter determining pan-genome openness [1].

Table 1: Mathematical Classification of Pan-Genome Types

| Pan-Genome Type | α Value | Behavior with Added Genomes | Genetic Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open Pan-Genome | α ≤ 1 | New gene families continue to be discovered indefinitely | High rates of horizontal gene transfer, extensive accessory genome |

| Closed Pan-Genome | α > 1 | New gene discoveries quickly plateau after limited sampling | Minimal horizontal gene transfer, limited accessory genome |

Ecological and Evolutionary Drivers

The classification of a species' pan-genome as open or closed reflects fundamental aspects of its biology and ecology [1]. Species with open pan-genomes typically exhibit larger supergenomes (the theoretical total gene pool accessible to a species), frequent horizontal gene transfer, and niche versatility [1]. Escherichia coli represents a classic example, with any single strain containing 4,000-5,000 genes while the species pan-genome encompasses approximately 89,000 different gene families and continues to expand with each newly sequenced genome [1].

Conversely, species with closed pan-genomes often specialize in specific ecological niches and demonstrate limited genetic exchange with other populations [1]. Staphylococcus lugdunensis provides an example of a commensal bacterium with a closed pan-genome, where sequencing additional strains yields diminishing returns in novel gene discovery [1]. Similarly, Streptococcus pneumoniae exhibits a closed pan-genome, with the number of new genes discovered approaching zero after approximately 50 sequenced genomes [1].

Methodological Approaches for Pan-Genome Analysis

Experimental Workflows and Computational Tools

Robust pan-genome analysis requires systematic approaches combining consistent genome annotation, orthology clustering, and quantitative assessment [22]. The critical first step involves homogenized genome annotation using standardized tools such as GeneMark or RAST to ensure comparable gene predictions across all strains [22]. Subsequent orthology clustering groups genes into families based on sequence similarity and evolutionary relationships, forming the foundation for presence-absence matrices that quantify gene distribution patterns [16] [22].

Table 2: Computational Tools for Pan-Genome Analysis

| Tool | Primary Methodology | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGAP2 | Fine-grained feature networks with dual-level regional restriction | Rapid ortholog identification; quantitative cluster parameters; handles thousands of genomes [8] | Large-scale prokaryotic pan-genome analysis; genetic diversity studies |

| Roary | OrthoFinder algorithm for clustering | Pan-genome matrix construction; core/accessory genome statistics [23] | Bacterial pathogen evolution; antibiotic resistance tracking |

| Panaroo | Advanced clustering and alignment | Gene presence/absence matrix; annotation error correction [23] | Bacterial population genetics; virulence factor identification |

| Anvi'o | Integrated visualization and analysis | Metapangenome capability; interactive visualizations [1] [23] | Microbial community analysis; functional genomics |

Recent methodological advances address the challenges of analyzing thousands of genomes while balancing computational efficiency with accuracy [8]. Next-generation tools like PGAP2 employ fine-grained feature analysis and dual-level regional restriction strategies to improve ortholog identification, particularly for paralogous genes and mobile genetic elements that complicate traditional analyses [8]. These approaches organize genomic data into gene identity networks and gene synteny networks, enabling more precise characterization of homology relationships through quantitative parameters such as gene diversity, connectivity, and bidirectional best hit criteria [8].

Figure 1: Pan-genome Analysis Workflow. The process begins with quality-controlled input genomes, progresses through annotation and orthology clustering, and culminates in pan-genome classification based on rarefaction curve behavior.

Key Reagents and Research Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Pan-Genome Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Long-read Sequencing (Nanopore/PacBio) | Resolves structural variants and repetitive regions | Genome assembly for pan-genome construction [24] |

| Prokka/RAST | Automated genome annotation | Consistent gene prediction across strains [22] |

| OrthoFinder | Orthology clustering across multiple genomes | Gene family identification and classification [23] |

| KhufuPAN | Graph-based pangenome construction | Agricultural breeding programs; trait discovery [25] |

| Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) | Genomes reconstructed from environmental sequencing | Studying unculturable species; environmental adaptation [26] |

Implications for Genetic Diversity and Niche Adaptation

Evolutionary Dynamics and Population Genetics

The structure of a species' pan-genome profoundly influences its evolutionary trajectory and adaptive potential [1] [26]. Species with open pan-genomes maintain extensive genetic diversity through several mechanisms, including higher rates of horizontal gene transfer, reduced selection pressure on accessory genes, and increased phylogenetic distance of recombination events [26]. These characteristics enable rapid adaptation to new environmental challenges and ecological niches by allowing beneficial genes to spread through populations while maintaining core biological functions [1].

In contrast, species with closed pan-genomes often employ different evolutionary strategies [26]. Recent research on freshwater genome-reduced bacteria reveals extended periods of adaptive stasis, where secreted proteomes exhibit remarkably high conservation due to low functional redundancy and strong selective constraints [26]. These species demonstrate significantly different patterns of molecular evolution, with their secreted proteomes showing near absence of positive selection pressure and reduction in genes evolving under negative selection compared to their cytoplasmic proteomes [26].

Ecological Specialization and Niche Adaptation

The pan-genome structure directly correlates with a species' ecological flexibility and niche adaptation capabilities [1] [27]. Open pan-genomes facilitate niche versatility by providing access to diverse genetic material that can be rapidly mobilized in response to environmental changes [1]. This pattern is particularly evident in generalist species that inhabit diverse environments and face fluctuating selective pressures [1].

Conversely, closed pan-genomes typically reflect specialist lifestyles with optimization for specific, stable ecological niches [1]. These species often exhibit genomic reductions that eliminate non-essential functions while retaining highly optimized pathways for their particular environment [26]. The relationship between pan-genome structure and niche adaptation represents a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy, with many species occupying intermediate positions based on their ecological context and evolutionary history [1] [26].

Figure 2: Ecological Implications of Pan-genome Types. Open and closed pan-genomes correlate with distinct evolutionary strategies and ecological adaptations, influencing niche breadth and adaptive dynamics.

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Biotechnological Research

Drug Discovery and Vaccine Development

Pan-genome analysis has revolutionized approaches to drug discovery and vaccine development by identifying potential targets conserved across pathogenic strains [22]. Reverse vaccinology approaches leveraging pan-genome data have successfully identified highly antigenic cell surface-exposed proteins within core genomes of pathogens such as Leptospira interrogans [22]. These conserved targets represent promising vaccine candidates with broad coverage across diverse strains [22].

Additionally, pan-genome studies facilitate tracking of antibiotic resistance genes and virulence factors that often reside in the accessory genome [16] [23]. Understanding the distribution patterns of these elements across bacterial populations enables more effective surveillance of emerging threats and informs the development of countermeasures that target conserved essential functions while accounting for strain-specific variations [16].

Microbial Community Engineering and Bioremediation

The principles of pan-genome dynamics inform strategies for engineering microbial communities for biotechnological applications [28] [27]. Recent research on anaerobic carbon-fixing microbiota demonstrates how tracking strain-level variation through metapangenomics can identify genetic changes that optimize metabolic functions such as methane production [28]. These approaches revealed that amino acid changes in mer and mcrB genes serve as key drivers of archaeal strain-level competition and methanogenesis efficiency [28].

Furthermore, studies of aquatic prokaryotes reveal that populations can function as fundamental units of ecological and evolutionary significance, with their shared flexible genomes forming a public good that enhances community resilience and functional capacity [27]. This perspective enables more effective bioengineering of microbial consortia for environmental applications including bioremediation, waste processing, and sustainable energy production [28] [27].

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The field of pan-genomics continues to evolve with several emerging frontiers promising to enhance our understanding of prokaryotic diversity and adaptation [8] [24]. Metapangenomics, which integrates pangenome analysis with metagenomic data from environmental samples, enables researchers to study genomic variation in uncultivated microorganisms and understand gene prevalence in natural habitats [1] [28]. This approach reveals how environmental filtering shapes the pan-genomic gene pool and provides insights into microbial ecosystem functioning [1].

Technological advances in long-read sequencing and graph-based genome representations are overcoming previous limitations in detecting structural variation and accessory genome elements [24] [25]. These improvements enable more comprehensive pan-genome constructions that capture the full spectrum of genomic diversity, particularly in complex regions inaccessible to short-read technologies [24]. Additionally, machine learning approaches are being integrated into pan-genome analysis pipelines to enhance pattern recognition, predict gene essentiality, and identify genotype-phenotype associations [24].

As these methodologies mature, pan-genome analysis will increasingly inform predictive models of microbial evolution, outbreak trajectories, and adaptive responses to environmental changes, with significant implications for public health, agriculture, and environmental management [8] [24].

The Impact of Horizontal Gene Transfer on Genomic Plasticity

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) represents a fundamental evolutionary mechanism that profoundly shapes genomic architecture and plasticity in prokaryotes. This technical review examines how HGT drives genetic innovation, facilitates rapid environmental adaptation, and expands the functional capabilities of microbial pangenomes. Through multiple molecular mechanisms—conjugation, transformation, and transduction—prokaryotes continuously acquire and integrate foreign genetic material, creating dynamic gene pools that operate beyond traditional vertical inheritance patterns. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of HGT detection methodologies, quantitative impacts on genome structure, and implications for antimicrobial resistance and drug development. We present standardized frameworks for analyzing HGT dynamics and discuss how the interplay between core and accessory genomes governs prokaryotic evolution and ecological specialization.

Horizontal gene transfer encompasses the movement of genetic material between organisms by mechanisms other than vertical descent. In prokaryotes, HGT is not merely a supplementary evolutionary process but a primary driver of genomic plasticity—the capacity of genomes to undergo structural and compositional changes in response to selective pressures [29]. Comparative genomic analyses reveal that a significant fraction of prokaryotic genes has been acquired through HGT, with estimates suggesting up to 17% of the Escherichia coli genome derives from historical transfer events [30]. The genomic plasticity afforded by HGT enables prokaryotes to rapidly access genetic innovations, allowing colonization of new niches and response to environmental challenges.

The prokaryotic pangenome concept provides a crucial framework for understanding HGT's impact. A species' pangenome comprises the core genome (genes shared by all individuals) and the flexible genome (genes present in some individuals) [5]. HGT primarily expands this flexible genome, creating remarkable genetic diversity within populations. Recent studies of marine prokaryotes reveal that even single populations can maintain thousands of rare genes in their flexible gene pool, with variants of related functions collectively termed "metaparalogs" [27]. This diversity enables prokaryotic populations to function as collective units with expanded metabolic capabilities, where the flexible genome operates as a public good enhancing ecological resilience.

Molecular Mechanisms of Horizontal Gene Transfer

Conjugation: Plasmid-Mediated Gene Transfer

Conjugation involves the direct cell-to-cell transfer of DNA, primarily plasmids and integrative conjugative elements (ICEs), through specialized contact apparatus. This mechanism dominates the spread of antibiotic resistance genes due to the high prevalence of broad-host-range plasmids carrying resistance cassettes [30]. Conjugative plasmids contain all necessary genes for transfer machinery assembly, while mobilizable plasmids rely on conjugation systems provided in trans. A global analysis of over 10,000 plasmids revealed they organize into discrete genomic clusters called Plasmid Taxonomic Units (PTUs), with more than 60% capable of crossing species barriers [31]. Plasmid host range follows a six-grade scale from species-restricted (Grade I) to cross-phyla transmission (Grade VI), determining their impact on HGT dissemination.

Transformation and Transduction

Transformation entails uptake and incorporation of environmental DNA, occurring either naturally in competent bacteria or through artificial laboratory induction. The process requires a transient physiological state triggered by environmental cues like nutrient availability [30]. While bioinformatic analyses indicate most bacteria possess competence gene homologs, the ecological significance of natural transformation remains uncertain compared to conjugation.

Transduction involves bacteriophage-mediated DNA transfer between bacteria. Though transduction typically exhibits narrower host ranges than conjugation due to phage receptor specificity, it can transfer diverse sequences including antibiotic resistance cassettes [30]. Transduction efficiency depends on phage-host interactions and the packaging specificity of the phage system.

Quantitative Dynamics of HGT

The population-level dynamics of conjugation can be mathematically modeled as a biomolecular reaction where transconjugant formation rate depends on donor and recipient densities [30]. The conjugation efficiency (η) is calculated as:

Table 1: HGT Mechanisms and Their Characteristics

| Mechanism | Genetic Elements | Host Range | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conjugation | Plasmids, ICEs, Conjugative transposons | Broad (up to cross-phyla) | Demonstrated transfer of antibiotic resistance in gut microbiota; plasmid classification by Inc groups and PTUs |

| Transformation | Environmental DNA fragments | Variable (species with competence) | Natural transformation in Streptococcus, Bacillus; bioinformatic detection of competence genes |

| Transduction | Bacteriophage-packaged DNA | Narrow (phage-specific) | Transfer of antibiotic resistance cassettes; phage receptor specificity studies |

Detection and Analysis Methodologies

Computational Identification of HGT

Bioinformatic detection of historical HGT events relies on identifying genomic regions with atypical sequence characteristics compared to the host genome. Primary detection criteria include:

- Phylogenetic Incongruity: Discordance between gene trees and species trees [29]

- Sequence Composition Bias: Deviations in GC content, codon usage, or oligonucleotide frequencies [29]

- Unexpected Similarity: Best BLAST hits to phylogenetically distant taxa rather than close relatives [29]

Recent pangenome analysis tools like PGAP2 implement fine-grained feature analysis with dual-level regional restriction strategies to improve ortholog identification accuracy [8]. These tools employ gene identity networks and synteny networks to distinguish vertically inherited from horizontally acquired genes despite annotation inconsistencies that complicate clustering.

Experimental Measurement of HGT Rates

Quantifying HGT dynamics requires carefully controlled experiments that distinguish actual transfer efficiency from selective effects. For conjugation studies, the rate of transconjugant formation follows:

[ \frac{dT}{dt} = \eta R D ]

Where T, R, and D represent transconjugant, recipient, and donor densities, respectively, and η is the conjugation efficiency [30]. Experimental designs must account for population growth dynamics and selection pressures to avoid confounding transfer rates with fitness effects. Antibiotic exposure, for instance, may appear to "promote" HGT by selectively enriching transconjugants rather than increasing fundamental transfer rates.

Figure 1: Computational Workflow for HGT Detection in Pan-genome Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions for HGT Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for HGT Investigation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| PGAP2 | Pan-genome analysis pipeline | Orthologous gene clustering in 2,794 Streptococcus suis strains; identifies HGT-derived regions [8] |

| AcCNET | Accessory genome analysis | Plasmidome network construction; identified 276 PTUs across bacterial domain [31] |

| Panaroo | Pangenome graph inference | Error-aware gene clustering accounting for annotation fragmentation [5] |

| Balrog/Bakta | Consistent gene annotation | Universal prokaryotic gene prediction without genome-specific training bias [5] |

| ANI/AF algorithms | Nucleotide identity analysis | Plasmid taxonomic unit classification; host range determination [31] |

Impact on Pangenome Architecture and Evolution

Quantitative Expansion of Genetic Repertoire

HGT dramatically expands prokaryotic pangenomes, creating "open" pangenomes where gene content increases indefinitely with each new genome sequenced. In the zoonotic pathogen Streptococcus suis, analysis of 2,794 strains revealed extensive accessory genome content driven by HGT [8]. This expansion follows characteristic distributions where a small core genome is complemented by numerous rare genes present in only subsets of strains.

The flexible genome compartment, predominantly composed of HGT-derived genes, exhibits functional biases toward niche adaptation. Environmental studies show HGT-enriched functions include specialized metabolic pathways, stress response systems, and antimicrobial resistance genes [27]. This functional specialization enables rapid population-level adaptation without requiring de novo mutation in individual genomes.

Evolutionary Dynamics and Selective Constraints

HGT creates complex evolutionary dynamics where genes experience different selective pressures depending on their origin and function. Horizontally acquired genes initially face compatibility challenges with recipient genomes, creating barriers to stable integration [32]. Successful HGT events typically involve:

- Adaptive Value: Genes providing immediate fitness benefits (e.g., antibiotic resistance in clinical environments)

- Integration Compatibility: Genetic elements with minimal disruptive impact on existing regulatory networks

- Functional Cooperation: Gene clusters that operate semi-autonomously (e.g., "selfish operons")

The fitness effects of HGT events vary spatially and temporally, exemplified by antibiotic resistance genes that confer advantages during drug treatment but impose fitness costs in antibiotic-free environments [32]. This context dependency creates complex evolutionary dynamics where HGT prevalence reflects both historical selection and current selective pressures.

Implications for Antimicrobial Resistance and Drug Development

HGT as a Primary Driver of Resistance Dissemination

Conjugative plasmid transfer represents the dominant mechanism for disseminating antibiotic resistance genes across bacterial populations [30]. Molecular epidemiology studies demonstrate identical resistance cassettes distributed across diverse phylogenetic backgrounds, indicating extensive horizontal spread. The gut microbiota serves as a particularly active HGT environment, where antibiotic exposure enriches resistant strains and promotes further transfer events [30].

Notable examples of HGT-mediated resistance spread include:

- β-lactamase enzymes (e.g., CTX-M, NDM-1) on conjugative plasmids across Enterobacteriaceae

- Vancomycin resistance (VanA) via Tn1546 transposition between enterococci and staphylococci

- Fluoroquinolone resistance (Qnr proteins) on multi-resistance plasmids

Table 3: Clinically Significant HGT-Mediated Resistance Mechanisms

| Resistance Mechanism | Genetic Element | Transfer Method | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) | Plasmids (e.g., blaCTX-M, blaNDM-1) | Conjugation | Carbapenem resistance; treatment failure in critical infections |

| Glycopeptide resistance | Transposon Tn1546 (vanA) | Conjugation, transposition | Vancomycin-resistant MRSA emergence |

| Quinolone resistance | Plasmid (qnr genes) | Conjugation | Reduced fluoroquinolone efficacy in Gram-negative infections |

| Multi-drug resistance cassettes | Integrons, genomic islands | Conjugation, transduction | Pan-resistant bacterial pathogens |

Therapeutic Interventions Targeting HGT

Understanding HGT mechanisms enables novel therapeutic approaches targeting resistance dissemination rather than bacterial viability. Potential strategies include:

- Conjugation Inhibition: Compounds disrupting mating pair formation or DNA transfer machinery

- Curing Agents: Agents promoting plasmid loss from bacterial populations

- CRISPR-Based Treatments: Phage-delivered systems targeting specific resistance genes

Experimental models demonstrate that precise quantification of conjugation rates is essential for evaluating intervention efficacy [30]. Combination therapies incorporating HGT inhibition with traditional antibiotics may prolong drug efficacy by slowing resistance dissemination.

Horizontal gene transfer represents a fundamental biological process that extensively reshapes prokaryotic genomes, driving adaptation through rapid acquisition of pre-evolved genetic traits. The impact of HGT on genomic plasticity manifests through expanded pangenomes, accelerated evolution of pathogenicity, and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. Future research directions include quantifying HGT rates in complex microbial communities, predicting fitness effects of transferred genes, and developing therapeutic strategies that target gene transfer processes. As sequencing technologies advance and pangenome analyses incorporate more diverse strains, our understanding of HGT's role in microbial evolution will continue to deepen, revealing new insights into life's fundamental evolutionary processes.

From Sequences to Solutions: Pan-Genome Analysis Tools and Biomedical Applications

The pan-genome represents the complete complement of genes within a species, encompassing both core genes present in all individuals and dispensable (or accessory) genes absent from one or more individuals [33] [34]. This conceptual framework has revolutionized genomic studies by moving beyond the limitations of a single reference genome to capture the full extent of genetic diversity within species [35] [36]. The accessory genome is typically further categorized into shell genes (found in most but not all individuals) and cloud genes (present in only a few individuals) [33]. For prokaryotic species, which often exhibit remarkable genomic plasticity, pan-genome analysis has become an indispensable method for studying genomic dynamics, ecological adaptability, and evolutionary trajectories [8] [27]. The construction of a pan-genome involves multiple computational steps, from initial sequence data processing to final gene clustering and annotation, with methodological choices significantly impacting the biological interpretations derived from the analysis [35].

Key Methodologies for Pan-Genome Construction

Primary Construction Approaches

Three primary methodologies have emerged for constructing pan-genomes, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate use cases [33] [35].

Table 1: Comparison of Pan-Genome Construction Methods

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Novo Assembly & Comparison | Individual genomes assembled separately followed by whole-genome or gene annotation comparison [33] | Most comprehensive approach; identifies novel sequences without reference bias; accurate structural variant detection [33] [34] | Computationally intensive; requires high-quality assemblies; challenging for large, repetitive genomes [33] [35] | MUMmer, Minimap2, SyRI, GET_HOMOLOGUES [33] |

| Reference-Based Iterative Assembly | Uses reference genome; unmapped reads assembled and annotated to identify novel sequences [33] [35] | Reduced computational requirements; leverages existing reference annotations; efficient for large datasets [33] | Reference bias may miss divergent sequences; depends on reference quality [33] [34] | Iterative mapping and assembly tools [33] |

| Graph-Based Pan-Genome | Represents genetic variants as nodes and edges in a graph structure [33] | Captures structural variations effectively; emerging as advanced reference; excellent visualization capabilities [33] [34] | Computational complexity increases with diversity; lack of standardized protocols for gene content inference [33] [35] | PanTools, graph genome builders [33] [37] |

Methodological Impact on Results

Studies have demonstrated that the choice of construction method significantly impacts the resulting gene pool and gene presence-absence variation (PAV) detections [35]. Different procedures applied to the same dataset can yield substantially different gene content inferences, with low agreement between methods. This highlights the importance of methodological decisions and the need for careful consideration of approach based on research objectives, available computational resources, and data characteristics [35]. The quality of input data, including sequencing depth and annotation consistency, further influences the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the resulting pan-genome [35] [38].

Pan-Genome Construction Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

Data Preparation and Quality Control

The initial phase involves gathering and validating input data, typically consisting of genome sequences in FASTA format and annotated gene structures in Genbank or GFF3 format [38] [37]. Quality control assesses sequencing data quality and filters low-quality reads. The EUPAN toolkit incorporates FastQC for quality assessment and Trimmomatic for filtering and trimming, implementing a iterative quality control process: preview overall qualities, trim/filter reads, review qualities, and re-trim with selected parameters as needed [39]. For prokaryotic genomes, additional quality measures include calculating average nucleotide identity (ANI) to identify outliers and assessing genome composition features [8].

Genome Assembly Strategies

For de novo approaches, individual genomes must be assembled from sequencing reads. EUPAN provides two strategies: direct assembly with a fixed k-mer size or iterative assembly with optimized k-mer selection [39]. The iterative approach uses a linear model of sequencing depth to estimate the optimal k-mer size, potentially yielding better assemblies though requiring more computation time. Assembly quality is evaluated using metrics such as assembly size, N50, and genome fraction (percentage of reference genome covered) [39]. For large-scale prokaryotic pan-genomes, recent tools like PGAP2 implement efficient assembly processing pipelines capable of handling thousands of genomes [8].

Pan-Genome Sequence Construction

Two primary strategies exist for constructing the comprehensive pan-genome sequences: reference-based and reference-free construction [39]. The reference-based approach, recommended when a high-quality reference genome exists, involves aligning contigs to the reference genome, retrieving unaligned contigs, merging unaligned contigs from multiple individuals, removing redundancies, checking for contaminants, and finally merging reference sequences with non-redundant unaligned sequences [39]. This approach benefits from existing high-quality reference annotations while still capturing novel sequences from other individuals.

Gene Annotation and Annotation Standardization

Gene annotation identifies functional elements within the pan-genome, including protein-coding genes, non-coding RNAs, and regulatory elements [36]. Consistent annotation across all genomes is critical for meaningful comparative analysis, as annotations derived from different methods or parameters can introduce technical biases that obscure biological signals [36] [38]. Tools like Mugsy-Annotator use whole genome multiple alignment to identify orthologs and evaluate annotation quality, detecting inconsistencies in gene structures such as translation initiation sites and pseudogenes [38]. For prokaryotic genomes, PGAP2 performs quality control and generates visualization reports for features like codon usage and genome composition [8].

Homology Clustering and Ortholog Identification

The final critical step groups genes into homology clusters representing orthologous relationships. PGAP2 implements a sophisticated approach using fine-grained feature analysis under a dual-level regional restriction strategy [8]. This method organizes data into gene identity and gene synteny networks, then infers orthologs through iterative regional refinement and feature analysis. The reliability of orthologous gene clusters is evaluated using three criteria: gene diversity, gene connectivity, and the bidirectional best hit (BBH) criterion for duplicate genes within the same strain [8]. PanTools similarly provides protein grouping functionality based on sequence similarity to connect homologous sequences in the pangenome database [37].