The Complete PCR Protocol Guide: From DNA Amplification Fundamentals to Advanced Optimization & Validation

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an in-depth understanding of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for DNA amplification.

The Complete PCR Protocol Guide: From DNA Amplification Fundamentals to Advanced Optimization & Validation

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an in-depth understanding of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for DNA amplification. It covers foundational principles, including the history and mechanics of PCR, and delivers detailed, step-by-step standard protocols. The article systematically addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to overcome common experimental pitfalls and enhance specificity and yield. Furthermore, it explores advanced validation techniques, quantitative methods, and cutting-edge applications such as multiplex assays and pathogen detection, providing a complete framework for implementing robust, reproducible PCR in both research and clinical settings.

Understanding PCR: The Fundamental Principles of DNA Amplification

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) represents one of the most transformative methodological breakthroughs in modern molecular biology. This technique, which enables the exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences from minimal starting material, has fundamentally reshaped scientific research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development. From its conceptual origins to its current status as a foundational tool in laboratories worldwide, PCR's evolution demonstrates how a simple concept can revolutionize entire fields. This article details the historical development of PCR, outlines core protocols essential for DNA amplification research, and explores its advanced applications, particularly within drug development. Framed within the context of a broader thesis on PCR methodology, this review provides researchers with both the technical protocols and the historical understanding necessary to leverage this powerful technology in their scientific pursuits.

Historical Development of PCR

The development of PCR was not a single event but a convergence of scientific discoveries spanning several decades, culminating in a technique that would democratize genetic analysis.

Foundational Discoveries (1953-1983)

The groundwork for PCR was laid by fundamental advances in molecular biology. In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick elucidated the double-helix structure of DNA, noting in their publication that the structure "immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material" [1] [2]. This was followed by Arthur Kornberg's isolation of the first DNA polymerase from E. coli in 1957, for which he received a Nobel Prize in 1959 [1] [2]. A critical conceptual precursor emerged from the work of Gobind Khorana and his team in the early 1970s, who investigated "repair synthesis" using primers and DNA polymerase to copy gene segments [1]. Notably, researcher Kjell Kleppe in Khorana's lab envisioned a two-primer system that could lead to the replication of a specific DNA segment, describing a process strikingly similar to PCR [2]. Despite these conceptual advances, the technique for exponential amplification remained unrealized for over a decade.

The Invention and Development at Cetus Corporation

In 1983, Kary Mullis, a chemist at Cetus Corporation, conceived of PCR while working on oligonucleotide synthesis [1] [2]. Mullis was inspired by Frederick Sanger's DNA sequencing method, which used a single primer. Mullis's key innovation was adding a second primer to the opposite strand and realizing that repeated cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension using DNA polymerase could create a chain reaction yielding exponential amplification of a specific DNA segment [1]. The initial experiments in 1983-1984 were challenging. The early process used the Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase, which was heat-labile and had to be replenished after each denaturation step [2]. The first successful amplification of a genomic DNA target—a 110 bp fragment from the β-hemoglobin gene—was confirmed via Southern blotting in November 1984, as the product was not initially visible on agarose gels [1] [2].

Critical Innovation: Thermostable Enzymes

A major breakthrough came with the introduction of a thermostable DNA polymerase. In 1969, Thomas Brock had reported the isolation of Thermus aquaticus (Taq), a thermophilic bacterium from Yellowstone National Park's hot springs [1]. The DNA polymerase from this bacterium (Taq polymerase) was isolated in 1976 and could withstand the high temperatures required for DNA denaturation [2]. In the fall of 1985, Susanne Stoffel and David Gelfand at Cetus successfully isolated Taq polymerase, and Randy Saiki soon demonstrated its superior performance in PCR [1] [2]. This innovation eliminated the need to add fresh enzyme after each cycle, enabling the automation of PCR in thermal cyclers [1]. The first paper describing PCR with Taq polymerase was published in 1985, and the enzyme was later named "Molecule of the Year" by the journal Science in 1989 [1].

Commercialization and Widespread Adoption

The partnership between Cetus Corporation and Perkin-Elmer was instrumental in commercializing PCR technology. Their joint venture led to the development of automated thermal cyclers and the commercial release of "AmpliTaq DNA Polymerase" in November 1987 [1]. As the technique spread, its impact was recognized with the highest scientific honors. Kary Mullis was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993, less than a decade after PCR's invention, underscoring its profound and rapid impact on science [1]. The subsequent development of real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) further expanded the applications of the technology from qualitative detection to precise quantification [3] [4].

Table 1: Key Milestones in the History of PCR

| Year | Event | Key Figure(s)/Entity | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | DNA Structure Discovery | Watson & Crick | Elucidated the double-helix structure and its copying mechanism [1]. |

| 1957 | First DNA Polymerase Isolated | Arthur Kornberg | Identified the enzyme central to DNA replication [1]. |

| 1971 | Concept of Two-Primer Replication | Kjell Kleppe | Envisioned a process similar to PCR for replicating a specific DNA segment [2]. |

| 1983 | Invention of PCR | Kary Mullis | Conceptualized the use of two primers and repeated cycles for exponential amplification [1]. |

| 1985 | First Clinical Application | Cetus Team | Used PCR to analyze sickle cell anemia mutation [1]. |

| 1985 | Use of Taq Polymerase | Stoffel, Gelfand, & Saiki | Introduced a thermostable enzyme, enabling automation [1]. |

| 1987 | First Commercial PCR Machine | Perkin-Elmer & Cetus | Made PCR technology accessible to labs worldwide [1]. |

| 1993 | Nobel Prize in Chemistry | Kary Mullis | Recognized the profound importance of the PCR method [1]. |

Core PCR Methodology and Protocols

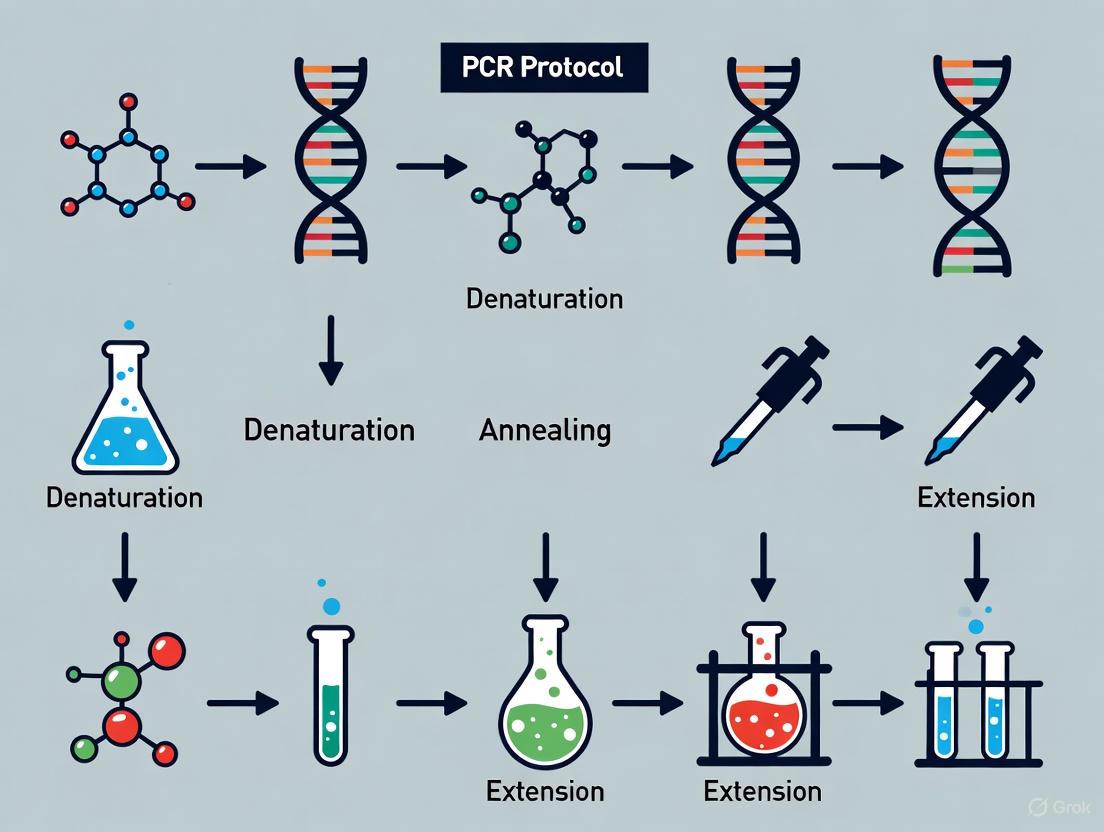

The fundamental principle of PCR is the enzymatic amplification of a specific DNA sequence defined by two oligonucleotide primers. The process involves three core steps repeated for 25-40 cycles.

Basic Principle and Reaction Components

PCR mimics the natural process of DNA replication but is confined to a short, targeted region of the genome. The core steps are:

- Denaturation: The double-stranded DNA template is heated to 94-98°C to separate it into two single strands.

- Annealing: The temperature is lowered to 50-65°C to allow the sequence-specific primers to bind (anneal) to their complementary sequences on the template strands.

- Extension: The temperature is raised to 72°C (the optimal temperature for many DNA polymerases), and the polymerase synthesizes new DNA strands by extending the primers in the 5' to 3' direction [3].

The exponential amplification occurs because the products of one cycle serve as templates for the next, theoretically doubling the amount of the target sequence with each cycle.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A standard PCR reaction requires a precise mixture of key components, each playing a critical role. The table below details these essential reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for a Standard PCR

| Reagent | Function | Typical Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | The DNA sequence to be amplified. | 1 pg - 1 µg (depending on source and complexity) |

| DNA Polymerase (e.g., Taq) | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands by adding nucleotides. | 0.5 - 2.5 units per 50 µL reaction |

| Primers (Forward & Reverse) | Short, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides that define the start and end of the target sequence. | 0.1 - 1.0 µM each |

| Deoxynucleotides (dNTPs) | The building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for the new DNA strands. | 200 µM each |

| Reaction Buffer | Provides optimal chemical conditions (pH, salts) for polymerase activity. | 1X concentration |

| Divalent Cations (MgCl₂) | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. Concentration is a key optimization parameter. | 1.5 - 2.5 mM |

Protocol: Standard Endpoint PCR for DNA Amplification

This protocol is designed for the amplification of a specific DNA fragment for downstream applications such as cloning, sequencing, or gel analysis.

I. Pre-PCR Setup

- Laboratory Preparation: Designate separate, clean areas for reagent preparation, sample addition, and post-PCR analysis to prevent contamination. Use aerosol-resistant pipette tips.

- Reagent Thawing: Thaw all reagents (except the polymerase) on ice or a cold block. Mix by gentle vortexing and briefly centrifuge to collect contents at the bottom of the tube.

- Master Mix Preparation: Prepare a master mix on ice for all reactions plus a 10% excess to account for pipetting error. This ensures consistency across samples.

- For a 50 µL reaction: 5.0 µL of 10X Reaction Buffer, 2.0 µL of 25 mM MgCl₂ (2.0 mM final), 1.0 µL of 10 mM dNTP mix (200 µM each final), 1.25 µL of 10 µM Forward Primer (0.25 µM final), 1.25 µL of 10 µM Reverse Primer (0.25 µM final), 0.25 µL of Taq DNA Polymerase (1.25 units), and 33.25 µL of Nuclease-Free Water.

- Aliquot and Add Template: Aliquot the appropriate volume of master mix into each PCR tube. Then, add the template DNA to each respective tube. Include a negative control containing nuclease-free water instead of template.

II. Thermal Cycling

- Load Thermocycler: Place the tubes in a pre-heated thermal cycler (or start the block at the initial denaturation temperature).

- Run the Following Program:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes (ensures complete separation of complex genomic DNA).

- Amplification (25-35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: X°C for 30 seconds (X is primer-specific; calculate Tm and optimize).

- Extension: 72°C for Y seconds (Y is ~1 minute per 1 kb of amplicon).

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes (ensures all amplicons are fully extended).

- Hold: 4-10°C indefinitely.

III. Post-PCR Analysis

- Analyze Product: Analyze the PCR product by agarose gel electrophoresis. A successful reaction will show a single, bright band of the expected size when compared to a DNA ladder. The negative control should show no bands, indicating the absence of contamination.

Evolution of PCR Technologies

The basic PCR methodology has been extensively refined and adapted, leading to a family of specialized techniques that cater to diverse research needs.

Diagram 1: The Evolution of PCR Technologies

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and Digital PCR (dPCR)

Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR) allows for the detection and quantification of a specific DNA sequence in real time as the amplification occurs, unlike traditional "endpoint" PCR. This is achieved by using fluorescent dyes or probes that intercalate with the double-stranded DNA or bind specifically to the target sequence. The cycle threshold (Ct), the point at which fluorescence crosses a background threshold, is used for quantification [3] [5]. qPCR is further divided into relative quantification, which compares expression levels between samples, and absolute quantification, which determines the exact copy number using a standard curve [6].

Digital PCR (dPCR) is a more recent refinement that provides absolute quantification without the need for a standard curve. The reaction mixture is partitioned into thousands of individual nanoliter-volume reactions, so that each contains either zero or one (or a few) target molecules. After PCR amplification, the number of positive partitions is counted, allowing for precise, absolute quantification of the target nucleic acid using Poisson statistics. dPCR is particularly valuable for detecting rare mutations, copy number variations, and viral load quantification due to its high sensitivity and precision [3] [4].

Advanced PCR Formats and Applications

Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) is a fundamental technique for gene expression analysis. It involves first converting RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the enzyme reverse transcriptase. This cDNA then serves as the template for a standard PCR reaction. When combined with qPCR, it becomes RT-qPCR, the gold standard for quantifying levels of gene expression [3] [5].

Multiplex PCR enables the simultaneous amplification of multiple targets in a single reaction by using multiple pairs of primers, each specific to a different DNA sequence. This is highly efficient for pathogen identification, genotyping, and high-throughput screening. The primers must be carefully designed to have similar annealing temperatures and to produce amplicons of distinct sizes or with different fluorescent labels to be distinguishable [1].

PCR Chips and Microfluidics represent a significant technological leap by miniaturizing and automating PCR processes onto microfluidic devices. These chips, often made of silicon, glass, or polymers like PDMS, contain microchannels and reaction chambers that handle nanoliter to picoliter volumes. This miniaturization offers substantial advantages, including reduced reagent consumption, faster thermal cycling due to low thermal mass, potential for portability, and high-throughput parallel processing. PCR chips are instrumental in applications ranging from point-of-care diagnostics to high-throughput biomarker validation in drug development [4].

Table 3: Comparison of Key PCR Variants

| Technique | Primary Function | Key Advantage | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard PCR | Amplification of a specific DNA sequence | Simplicity and low cost | Cloning, genotyping, sequencing template preparation |

| Real-Time PCR (qPCR) | Quantification of nucleic acids | Real-time monitoring and high sensitivity | Gene expression analysis, viral load monitoring, SNP detection |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Absolute quantification of nucleic acids | Highest precision and sensitivity, no standard curve needed | Detection of rare mutations, copy number variation, liquid biopsies |

| Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) | Amplification of RNA sequences | Converts RNA into a DNA template for amplification | Gene expression studies, RNA virus detection |

| Multiplex PCR | Simultaneous amplification of multiple targets | High efficiency and throughput | Pathogen identification, genetic disease screening, forensic analysis |

PCR in Modern Drug Development

PCR has become an indispensable tool in the pharmaceutical industry, accelerating and refining multiple stages of drug discovery and development.

Biomarker Discovery and Validation

Biomarkers are biological molecules that indicate a biological state, and are crucial for explaining disease mechanisms, stratifying patients, and monitoring therapeutic responses [4]. The limitations of traditional biomarker discovery methods (e.g., ELISA, Western blotting)—such as low throughput, large sample volume requirements, and suboptimal sensitivity—are effectively addressed by modern PCR technologies [4]. PCR chips, in particular, have revolutionized this field by enabling high-throughput, parallel processing of samples with minimal reagent consumption, allowing researchers to identify and validate novel biomarkers with greater accuracy and reproducibility [4]. Furthermore, single-cell PCR chips allow for biomarker detection at a single-cell resolution, revealing heterogeneity within cell populations that is often masked in bulk analyses [4].

Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Medicine

PCR is fundamental to pharmacogenetics, which studies how genetic variations affect an individual's response to drugs. By detecting specific genetic polymorphisms (e.g., in genes coding for drug-metabolizing enzymes), PCR-based tests can predict therapeutic efficacy and the likelihood of adverse events, aiding in dose selection and personalized treatment plans [3]. This forms the basis for companion diagnostics, where a specific PCR test is developed alongside a drug to identify the patient population most likely to benefit from the treatment [4]. This approach is a cornerstone of personalized medicine, ensuring "that the right patient receives the right treatment" [4].

Supporting Gene and Small Molecule Therapies

PCR plays multiple critical roles in the development of advanced therapies. For Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV)-based gene therapies, PCR is used in biodistribution studies to track where AAV vectors localize in tissues after administration and to monitor vector-derived RNA levels in patients, thereby assessing the therapy's delivery and activity [3]. In the development of small molecule drugs, qPCR and RT-qPCR are used to measure changes in gene expression in response to drug treatment. This helps identify molecular biomarkers linked to drug efficacy or toxicity and track the downstream effects of small molecule inhibitors, such as kinase inhibitors on signal transduction pathways [3].

Protocol: Analytical Validation of a qPCR Assay for Transcriptional Biomarkers

The use of qPCR assays in clinical drug development requires rigorous analytical validation to ensure the generated data is reliable and meaningful [5]. This protocol outlines the key steps for validating an external standard qPCR assay.

I. Reagent Preparation and Calibration

- Standard Curve Generation: Produce a high-quality RNA standard via in vitro transcription of the target sequence from a linearized cloning vector. Purify the transcript to ensure uniformity and accurately determine its concentration (e.g., by absorbance at 260 nm). Calculate the copy number based on the known size and concentration.

- Prepare Serial Dilutions: Generate a calibration curve using 6-10 concentrations of the standard, typically via 10-fold serial dilutions, in replicates.

II. Assay Validation and QC Establishment

- Define Analytical Parameters: Perform a minimum of five independent analytical runs to assess:

- Precision (Imprecision): Calculate the intra-assay and inter-assay Coefficient of Variation (%CV).

- Accuracy (Bias): Determine the percentage difference (% bias) between the measured concentration and the "true" known concentration of the standard.

- Determine Quantification Limits:

- Lower Limit of Quantification (LLQ): The lowest copy number measurable with a %CV and % bias ≤ ±30%, and which generates a Ct value < 36 cycles.

- Upper Limit of Quantification (ULQ): The highest concentration measurable with a %CV and % bias ≤ ±30%.

- The range between LLQ and ULQ defines the assay's quantitative range.

- Quality Control (QC) Samples: Prepare validation samples (e.g., low, mid, and high-range concentrations) by spiking the transcript into a relevant matrix (e.g., total RNA). These should be used in large batches to serve as long-term QC samples for future clinical sample runs.

III. Clinical Sample Analysis

- Run Clinical Samples: With the validated assay and established QC acceptance criteria, analyze clinical samples. Include the calibration curve and QC samples in every analytical run to monitor and ensure consistent performance [5].

Diagram 2: The Role of PCR in Clinical Drug Development Decision-Making

From its conceptualization in the early 1980s to its current status as a bedrock of molecular biology, PCR has undergone a remarkable evolution. The journey from a manual, labor-intensive process using a heat-labile enzyme to automated, quantitative, and miniaturized platforms reflects continuous innovation. The development of qPCR, dPCR, and microfluidic PCR chips has expanded the technique's utility from simple DNA amplification to sensitive quantification, single-cell analysis, and high-throughput biomarker screening. Within drug development, PCR now provides critical insights that guide decision-making, from target identification and patient stratification to monitoring therapeutic efficacy. As PCR technology continues to converge with fields like artificial intelligence and multi-omics, its role in accelerating drug discovery and advancing personalized medicine is poised to grow even further, solidifying its legacy as one of science's most transformative tools.

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology that allows for the exponential amplification of a specific DNA sequence. At its core, the process relies on the precise repetition of three temperature-dependent steps: denaturation, annealing, and extension. These steps form one cycle, which is typically repeated 25-40 times to generate millions to billions of copies of a target DNA fragment from a minimal starting amount. Understanding the mechanics of each step is critical for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize assays, develop diagnostics, and ensure reproducible results in DNA amplification research. This application note details the quantitative parameters, molecular interactions, and experimental protocols that govern these core mechanics, providing a framework for robust PCR experimental design.

The Three-Step Cycling Process

The power of PCR hinges on the cyclic repetition of three fundamental steps. The table below summarizes the core function and typical conditions for each step.

Table 1: Core Steps of the PCR Cycle

| Step | Core Function | Typical Temperature | Typical Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturation | Separates double-stranded DNA into single strands | 94–98°C | 15 seconds to 2 minutes |

| Annealing | Allows primers to bind to their complementary sequences on the template | 45–72°C (typically 3–5°C below primer Tm) | 30 seconds to 1 minute |

| Extension | Synthesizes a new DNA strand complementary to the template | 70–75°C (depending on the polymerase) | 1 minute per kilobase (varies with polymerase) |

Denaturation

The cycle begins with the denaturation step, where the reaction mixture is heated to a high temperature, typically between 94°C and 98°C. This heat input provides the kinetic energy necessary to break the hydrogen bonds holding the two complementary strands of the DNA template together, resulting in single-stranded DNA molecules. These single strands serve as the templates for the subsequent copying process. The initial denaturation at the start of the PCR program is often longer (1-3 minutes) to ensure complete separation of all complex double-stranded DNA, such as genomic DNA [7]. For subsequent cycles, a shorter duration of 15-60 seconds is usually sufficient [7]. Factors such as high GC content ((>)65%) may require higher denaturation temperatures or longer incubation times to ensure complete strand separation [7].

Annealing

Immediately following denaturation, the reaction temperature is rapidly lowered to a defined annealing temperature, typically between 50°C and 65°C. This temperature is critical for specificity, as it determines how selectively the primers bind to their complementary sequences on the single-stranded DNA templates. Primers are short, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides (usually 15-30 nucleotides long) that are designed to flank the target region [8].

The annealing temperature is calculated based on the melting temperature (Tm) of the primers, which is the temperature at which 50% of the primer-DNA duplexes are dissociated. A common starting point is to set the annealing temperature 3–5°C below the lowest Tm of the primer pair [7]. The simplest formula for estimating Tm is: Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T), where G, C, A, and T represent the number of each nucleotide in the primer [7] [9]. If the temperature is too high, primers may not bind efficiently, leading to low yield. If it is too low, primers may bind non-specifically to incorrect sites, resulting in amplification of non-target products [7]. The annealing step typically lasts 30 seconds to 1 minute [9].

Extension

The final step in the cycle is extension or elongation, during which the DNA polymerase synthesizes a new DNA strand. The temperature is raised to the optimal temperature for the DNA polymerase's activity, which is often 72°C for commonly used enzymes like Taq polymerase [9] [10]. At this temperature, the polymerase binds to the 3' end of the primer-template hybrid and begins adding free deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) in a 5' to 3' direction, synthesizing a new DNA strand complementary to the template [11].

The duration of the extension step is directly proportional to the length of the amplicon and the synthesis rate of the DNA polymerase. A common rule of thumb is 1 minute per kilobase for Taq DNA Polymerase, though "fast" enzymes may require less time [7]. For instance, Pfu DNA polymerase, known for its high fidelity, typically requires 2 minutes per kilobase [7]. After the final cycle, a final extension step of 5-15 minutes is often included to ensure all amplicons are fully extended and to allow for proper 3'-dA tailing if the PCR product is intended for TA cloning [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for a Standard PCR

This protocol is designed for a conventional three-step PCR using a thermostable DNA polymerase and is scalable for multiple reactions.

Reagent Preparation and Master Mix

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 2: Essential Reagents for a Standard PCR

| Reagent | Final Concentration/Amount | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | 1–1000 ng (10^4–10^7 molecules) | The DNA sample containing the target sequence to be amplified. |

| Forward & Reverse Primers | 0.1–1.0 µM each (20–50 pmol per reaction) | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences that define the start and end points of the target region. |

| DNA Polymerase (e.g., Taq) | 0.5–2.5 units per 50 µL reaction | Heat-stable enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands by adding dNTPs. |

| dNTP Mix | 200 µM each (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) | The building blocks (nucleotides) used by the polymerase to synthesize new DNA. |

| PCR Buffer (10X) | 1X concentration | Provides the optimal pH and salt conditions (including Mg²⁺) for polymerase activity. |

| Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | 1.5–2.5 mM (if not in buffer) | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. Concentration requires optimization. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Q.S. to final volume | Solvent that maintains reaction volume and ionic strength. |

Procedure:

- Design Primers: Design forward and reverse primers (15–30 nucleotides) with comparable melting temperatures (Tm within 5°C), 40–60% GC content, and avoid self-complementarity or primer-dimer formation [8]. Use tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST for specificity.

- Thaw Reagents: Thaw all PCR reagents (except the polymerase) on ice or a cold block. Mix each reagent by gentle vortexing and brief centrifugation.

- Prepare Master Mix: Calculate the volumes required for a single 50 µL reaction (see Table 3). To minimize pipetting error and ensure consistency between samples, prepare a Master Mix for all reactions plus 10% extra. Add reagents in the following order to a sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube: water, buffer, dNTPs, MgCl₂ (if needed), primers, and DNA polymerase [8] [11].

- Aliquot and Add Template: Mix the Master Mix thoroughly by pipetting. Aliquot the appropriate volume of Master Mix into individual PCR tubes or a multi-well plate. Then, add the required volume of template DNA to each tube. Include a negative control (replace template with nuclease-free water).

- Seal and Centrifuge: Cap the tubes or seal the plate. Briefly centrifuge to collect all contents at the bottom and eliminate air bubbles.

Table 3: Sample Pipetting Scheme for a 50 µL Reaction

| Reagent | Final Concentration | Volume per 50 µL Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease-Free Water | - | 33.0 µL |

| 10X PCR Buffer | 1X | 5.0 µL |

| 10 mM dNTP Mix | 200 µM | 1.0 µL |

| 25 mM MgCl₂ | 1.5–2.5 mM | 2.0 µL (varies) |

| 20 µM Forward Primer | 0.4 µM | 1.0 µL |

| 20 µM Reverse Primer | 0.4 µM | 1.0 µL |

| DNA Polymerase (5 U/µL) | 1.25 U | 0.25 µL |

| Template DNA | Variable (e.g., 100 ng) | 6.75 µL (example) |

| Total Volume | 50.0 µL |

Thermal Cycler Programming

- Program the Thermal Cycler: Before assembling the reaction, program the thermal cycler with the following standard protocol [7] [9] [8]:

- Initial Denaturation: 94–95°C for 2–5 minutes (activates hot-start polymerases and ensures full DNA denaturation).

- Cycling (25–40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94–95°C for 15–30 seconds.

- Annealing: X°C (primer-specific, see optimization below) for 30–60 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase of the target amplicon.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5–10 minutes.

- Hold: 4–10°C indefinitely.

- Load and Run: Place the PCR tubes/plate in the thermal cycler and start the run.

Post-Amplification Analysis

- Analyze PCR Product: Once cycling is complete, analyze the amplified DNA by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Visualize: Use an intercalating dye to visualize the DNA under UV light. A single, sharp band of the expected size should be visible. A smear or multiple bands indicate non-specific amplification, requiring protocol optimization.

Optimization and Troubleshooting Strategies

Despite its robustness, PCR often requires optimization for each new primer-template pair. Key parameters to optimize are annealing temperature and MgCl₂ concentration.

Annealing Temperature Optimization

The calculated Tm is only a starting point. Empirical optimization is crucial for specificity and yield.

Protocol:

- Method: Use a thermal cycler with a gradient function. Set the annealing step to a temperature gradient across the block (e.g., from 50°C to 65°C) for the same primer pair and template.

- Analysis: Run the PCR and analyze the products by gel electrophoresis. The optimal temperature is the highest one that produces a strong, specific band with no non-specific products [7]. If no product is observed, lower the temperature in increments of 2–3°C. If non-specific products are present, raise the temperature similarly [7].

MgCl₂ Concentration Optimization

Mg²⁺ is a critical cofactor for polymerase activity, and its optimal concentration depends on the specific buffer, dNTP, and primer combination.

Protocol:

- Method: Set up a series of reactions where the concentration of MgCl₂ is varied, typically between 1.0 mM and 4.0 mM in increments of 0.5 mM.

- Analysis: Analyze the products by gel electrophoresis. The concentration that yields the strongest specific product with the least background is chosen for future experiments.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- No Product: Check primer design and concentration, lower the annealing temperature, increase MgCl₂ concentration, or ensure the polymerase is active.

- Non-specific Bands/Background Smear: Increase the annealing temperature, reduce cycle number, reduce primer or MgCl₂ concentration, or use a hot-start polymerase.

- Primer-Dimer Formation: Redesign primers to avoid 3'-end complementarity, increase annealing temperature, or use higher-quality primers.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology that enables the enzymatic amplification of specific DNA sequences from a complex template. The success and fidelity of this process are critically dependent on the precise formulation of the reaction mixture. This application note details the function, optimization, and interplay of four essential PCR components—DNA polymerase, primers, deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and reaction buffer—within the context of DNA amplification research for drug development and scientific discovery. A thorough understanding of these components is paramount for designing robust and reproducible experimental protocols.

Core Components and Their Functions

DNA Polymerase

DNA polymerase is the core enzymatic driver of PCR, responsible for synthesizing new DNA strands by incorporating nucleotides complementary to the template strand. The thermostable Taq DNA polymerase, isolated from Thermus aquaticus, revolutionized PCR by surviving the high denaturation temperatures required for each cycle, with a half-life of approximately 40 minutes at 95°C [12]. It incorporates nucleotides at a rate of about 60 bases per second at 70°C and can typically amplify targets up to 5 kb in length [12].

Modern PCR utilizes a range of engineered DNA polymerases with enhanced properties. Key characteristics for selection include:

- Thermal Stability: Essential for withstanding prolonged exposure to denaturing temperatures (95-98°C). Polymerases from hyperthermophiles, such as Pfu from Pyrococcus furiosus, offer superior stability [13].

- Fidelity: Refers to the accuracy of nucleotide incorporation. Proofreading polymerases with 3'→5' exonuclease activity, common in archaeal enzymes, possess higher fidelity and lower error rates (e.g., 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁷ errors/base) compared to non-proofreading enzymes like Taq (2 × 10⁻⁴ to 2 × 10⁻⁵ errors/base) [13]. This is critical for applications like cloning and sequencing.

- Processivity: The number of nucleotides incorporated per polymerase-binding event. Enhanced processivity is beneficial for amplifying long or complex templates [13].

- Extension Rate: The speed of DNA synthesis, typically one minute per 1000 bases for many polymerases, though this can vary [13].

Hot-start PCR, achieved through antibody-based or chemical modification of the enzyme, is a common technique to inhibit polymerase activity at low temperatures, thereby preventing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation prior to the first denaturation step [13].

Table 1: Common DNA Polymerases and Their Properties

| Polymerase | Source | Proofreading | Typical Application | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | Thermus aquaticus | No | Standard PCR, genotyping | Thermostable, relatively low fidelity |

| Pfu | Pyrococcus furiosus | Yes | High-fidelity PCR, cloning | High fidelity, thermostable |

| Engineered Blends | Recombinant | Varies | Long-range, GC-rich, fast PCR | Enhanced processivity, speed, and/or fidelity |

Primers

PCR primers are short, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides (typically 15-30 nucleotides) that define the start and end points of the amplification target by binding flanking sequences via complementary base pairing [12] [14]. The forward primer anneals to the antisense (template) strand, and the reverse primer anneals to the sense strand, enabling DNA polymerase to extend the region between them.

Proper primer design is arguably the most critical factor for PCR specificity and efficiency. The following design principles should be adhered to [12] [15] [14]:

- Length: 15–30 nucleotides.

- GC Content: 40–60%, with uniform distribution of G and C bases.

- Melting Temperature (Tm): 55–70°C, with the Tm of the forward and reverse primers within 5°C of each other.

- 3' End: Should end with a C or G base (GC clamp) to promote stronger anchoring due to stronger hydrogen bonding, but avoid runs of more than three G or C bases, which can promote mispriming.

- Specificity: Avoid self-complementarity (hairpins), complementarity between primers (primer-dimers), and direct repeats.

Primer concentration in the reaction is typically between 0.1–1 μM. Higher concentrations can lead to nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation, while lower concentrations may result in low yield or no amplification [12] [13].

Deoxynucleoside Triphosphates (dNTPs)

dNTPs (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) are the essential building blocks from which DNA polymerase synthesizes new DNA strands [12]. They are typically added to the PCR reaction in equimolar concentrations to ensure balanced incorporation.

The recommended final concentration of each dNTP is generally 0.2 mM (200 μM) for standard PCR [12] [13]. This concentration is maintained well above the estimated Km of DNA polymerase (0.010–0.015 mM) to ensure efficient incorporation, while avoiding inhibition that can occur at excessively high concentrations [12]. The concentration of dNTPs is intrinsically linked to the Mg²⁺ concentration, as Mg²⁺ binds to dNTPs to form the active substrate for the polymerase. Unbalanced dNTP concentrations can be intentionally used in certain applications, such as random mutagenesis [12].

Modified nucleotides, such as deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP), can be substituted for dTTP. When used in conjunction with Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG) pre-treatment, this strategy can prevent carryover contamination from previous PCR reactions [12]. Other modified dNTPs (e.g., biotin- or fluorescein-labeled) are used to incorporate labels for downstream detection and analysis.

Reaction Buffer

The PCR buffer provides the optimal chemical environment for DNA polymerase activity and primer-template hybridization. Its most critical component is Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺), which act as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase [12]. Mg²⁺ facilitates the formation of the complex between primers and the DNA template by stabilizing the negative charges on their phosphate backbones and catalyzes phosphodiester bond formation during polymerization [12].

The final concentration of Mg²⁺ usually ranges between 0.5–5.0 mM, with 1.5 mM being a common starting point [13] [14]. Optimization is often required, as the concentration affects reaction specificity, fidelity, and yield. Excess Mg²⁺ can reduce specificity and, for proofreading enzymes, may impact fidelity, while insufficient Mg²⁺ can result in low yield [12] [16]. The Mg²⁺ concentration must be higher than the total dNTP concentration [16].

Beyond MgCl₂, PCR buffers may contain other components such as Tris-HCl (to maintain a stable pH, usually around 8.0-8.5), potassium salt (K⁺, typically 35-100 mM to promote primer annealing), and additives like detergents to stabilize the enzyme [13] [14].

Component Interplay and Reaction Optimization

The four core components do not function in isolation; their concentrations are interdependent and must be balanced for a successful reaction. The relationship between Mg²⁺ and dNTPs is a prime example, as Mg²⁺ chelates dNTPs, making them unavailable for the polymerase. If the dNTP concentration is increased, the Mg²⁺ concentration may need to be proportionally increased to ensure an adequate supply of free Mg²⁺ for the enzyme [12]. Furthermore, the fidelity of non-proofreading DNA polymerases can be improved by using lower dNTP concentrations (0.01–0.05 mM) with proportionally reduced Mg²⁺ [12].

Table 2: Standard 50 μL PCR Reaction Setup

| Reagent | Standard Final Concentration | Stock Solution | Example Volume for 1 Reaction | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sterile Water | - | - | Variable (to 50 µL) | Q.S. to final volume |

| 10X PCR Buffer | 1X | 10X | 5 µL | May contain 15 mM MgCl₂ |

| MgCl₂ | 0.5 - 5.0 mM (often 1.5 mM) | 25 mM | 0 - 3 µL | Omit if already in buffer; requires titration |

| dNTP Mix | 200 µM (each) | 10 mM (each) | 1 µL | |

| Forward Primer | 0.1 - 1 µM | 20 µM | 0.5 µL | |

| Reverse Primer | 0.1 - 1 µM | 20 µM | 0.5 µL | |

| DNA Template | 10⁴ - 10⁷ molecules | Variable | 1 µL (e.g., 100 ng gDNA) | Amount depends on source & complexity |

| DNA Polymerase | 0.5 - 2.5 Units | e.g., 5 U/µL | 0.5 µL | Follow manufacturer's recommendations |

| Total Volume | 50 µL |

Workflow for PCR Setup

The following experimental workflow outlines a standard protocol for setting up a conventional PCR, from primer design to analysis.

Thermal Cycling Protocol

After assembling the reaction, it is placed in a thermal cycler. A typical 3-step cycling protocol is as follows [15] [17]:

- Initial Denaturation: 94–98°C for 3–5 minutes. One cycle.

- Amplification Cycles (25–35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94–98°C for 10–60 seconds.

- Annealing: 52–65°C (typically 5°C below the primer Tm) for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 70–80°C (72°C for Taq) for 1 minute per 1000 bp.

- Final Extension: 70–80°C for 5–10 minutes. One cycle.

- Hold: 4°C indefinitely.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCR

| Item | Function/Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Engineered to be inactive at room temperature, reducing off-target amplification. | Critical for high-specificity applications. Available as antibody-mediated or chemically modified [13]. |

| PCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed, optimized solution containing buffer, dNTPs, Mg²⁺, and polymerase. | Saves time, reduces pipetting errors and contamination risk [15] [17]. |

| dNTP Mix | An equimolar mixture of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP. | Sourced as a ready-to-use solution at a defined concentration (e.g., 10 mM each) [14]. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | A separate, standardized Mg²⁺ source for fine-tuning reaction conditions. | Essential for optimization when the buffer's Mg²⁺ concentration is not optimal for a specific primer/template [14]. |

| PCR Additives | Reagents like DMSO (1-10%), formamide (1.25-10%), or BSA (10-100 μg/mL). | Used to enhance amplification of difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich) or counteract inhibitors [13] [14]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Sterile, purified water guaranteed to be free of nucleases and contaminants. | Prevents degradation of reagents and template, and avoids introduction of exogenous DNA [14]. |

Advanced Applications and Concluding Remarks

The foundational components described herein are the bedrock upon which specialized PCR applications are built. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) leverages fluorescent dyes or probes to monitor amplification in real-time, requiring precise reagent concentrations for accurate quantification [18] [19] [20]. Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) first converts RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) using a reverse transcriptase enzyme, before proceeding with standard PCR amplification [15]. Other advanced formats, such as multiplex PCR (amplifying multiple targets simultaneously) and long-range PCR (amplifying large fragments >10 kb), rely on specialized polymerases and meticulously optimized buffer systems to achieve their goals [13].

In conclusion, a deep and practical understanding of the roles and optimal conditions for DNA polymerase, primers, dNTPs, and buffer is non-negotiable for successful DNA amplification research. Systematic optimization of these components, guided by the principles and protocols outlined in this note, will empower researchers and drug development professionals to achieve specific, efficient, and reliable PCR results.

Within the broader context of developing robust Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) protocols for DNA amplification research, the design of oligonucleotide primers stands as a critical foundational step. Proper primer design directly determines the success, specificity, and efficiency of PCR, which is a cornerstone technique in molecular biology, diagnostics, and drug development [21]. Optimal primers are paramount for achieving maximal specificity and efficiency, making them a cornerstone of accurate molecular biology experiments [22]. This guide details the essential rules and methodologies for designing high-quality primers, providing researchers with a structured framework to enhance experimental reproducibility and accuracy in DNA amplification research.

Core Principles of Primer Design

The quality of oligonucleotide primers is the most significant determinant of reaction specificity and efficiency in PCR [23]. Adherence to established thermodynamic and structural rules during the design phase is non-negotiable for robust amplification. The following parameters are fundamental to designing primers that minimize off-target binding and ensure stable annealing.

Length, Melting Temperature, and GC Content

The physical characteristics of a primer—its length, melting temperature, and base composition—are interconnected properties that govern its hybridization behavior.

- Primer Length: For standard PCR applications, optimal primer length is typically between 18 and 30 nucleotides [22] [24]. This range provides a balance between specificity and efficient annealing; shorter primers may reduce specificity, while longer primers can form secondary structures that hinder annealing [23] [25].

- Melting Temperature (Tm): The Tm is the temperature at which 50% of the DNA duplex dissociates into single strands. The ideal Tm for primers generally falls between 55°C and 65°C [23] [24]. Crucially, the forward and reverse primers in a pair should have closely matched Tms, ideally within 1–2°C of each other, to ensure synchronous binding to the template DNA during the annealing step [23] [14].

- GC Content: The proportion of Guanine (G) and Cytosine (C) bases in the primer should be between 40% and 60%, with an ideal content of around 50% [22] [24] [14]. This provides sufficient sequence complexity while avoiding overly stable GC-rich regions that can promote non-specific binding.

Table 1: Optimal Ranges for Key Primer Design Parameters

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 nucleotides [22] [24] | Balances specificity and binding efficiency. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [22] [24] | Ensures stable hybridization; avoids high Tm or secondary structures. |

| Tm | 55–65°C [23] [24] | Determines optimal annealing temperature. |

| Tm Difference (Primer Pair) | ≤ 2–5°C [24] [14] | Ensures both primers bind efficiently and simultaneously. |

Sequence Composition and 3'-End Stability

Beyond general parameters, the specific sequence of the primer, particularly at its 3' end, is vital for accurate initiation of DNA synthesis.

- 3'-End Stability (GC Clamp): The last five bases at the 3' end of the primer, often called the "core," should be rich in G and C bases [23]. The presence of G or C residues creates a GC clamp, which strengthens binding through their three hydrogen bonds and helps prevent "breathing" (fraying) of the primer ends, thereby enhancing priming efficiency [14] [26]. However, avoid runs of three or more G or C bases at the very 3' end, as this can lead to non-specific binding [22] [26].

- Avoiding Repetitive Sequences: Primer sequences should not contain runs of the same nucleotide (homopolymers, e.g., AAAAA) or consecutive di-nucleotide repeats (e.g., ATATAT). These repeats can cause the polymerase to slip, resulting in mispriming and heterogeneous products [14].

- Template Specificity: The primer sequence must be unique to the intended target. Using bioinformatics tools like NCBI BLAST to check for the target specificity of the primers is a critical step to avoid amplification of related pseudogenes or homologous sequences [24] [14].

Avoiding Secondary Structures

Primers must be screened for self-complementarity, which can lead to secondary structures that sequester the primer and prevent it from binding to the template DNA [23].

- Hairpins: Intramolecular folding within a single primer can create stem-loop structures. The ΔG (free energy) for any hairpin should be weaker (more positive) than -3 kcal/mol for internal hairpins and -2 kcal/mol for hairpins at the 3' end [25].

- Self-Dimers and Cross-Dimers: Self-dimers form when two copies of the same primer anneal to each other, while cross-dimers form when the forward and reverse primers anneal. These structures are preferentially amplified, consuming reagents and lowering the yield of the desired product [23] [14]. The ΔG for any dimer should be weaker than -5 kcal/mol for the 3' end and -6 kcal/mol for internal dimers [25].

Table 2: Guidelines for Avoiding Primer Secondary Structures

| Structure | Description | Acceptable ΔG Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Hairpin | Intra-primer folding into a stem-loop. | > -3 kcal/mol (internal); > -2 kcal/mol (3' end) [25] |

| Self-Dimer | Inter-molecular annealing between two identical primers. | > -5 kcal/mol (3' end); > -6 kcal/mol (internal) [25] |

| Cross-Dimer | Inter-molecular annealing between forward and reverse primers. | > -5 kcal/mol (3' end); > -6 kcal/mol (internal) [25] |

Optimization Strategies and Experimental Protocols

Once primers are designed according to the core principles, meticulous experimental setup and optimization are required to achieve high-fidelity amplification.

Calibrating the Annealing Temperature

The annealing temperature (Ta) is perhaps the most critical thermal parameter, directly controlling the stringency of primer-template binding [23].

- Relationship between Tm and Ta: For most standard PCR protocols, the optimal annealing temperature is typically 3–5°C below the calculated Tm of the primers [22] [23]. A Ta that is too low permits primers to bind to sequences with imperfect complementarity, leading to non-specific amplification. Conversely, a Ta that is too high reduces reaction efficiency, as the primers cannot anneal to the template effectively, resulting in low or no product yield [23].

- Gradient PCR: The most efficient method for determining the optimal Ta is to perform a gradient PCR experiment. This involves running the same reaction across a range of annealing temperatures (e.g., 50–68°C) in a thermal cycler with a gradient function. The optimal Ta is identified as the highest temperature that yields a strong, specific product [23].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Annealing Temperature Optimization

Reaction Component Optimization

The chemical environment of the PCR significantly impacts specificity and yield.

- Magnesium Ion Concentration: Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) are an essential cofactor for all thermostable DNA polymerases [23]. The typical optimal concentration ranges from 1.5 to 2.5 mM, but fine-tuning is often necessary [17] [14]. Low Mg²⁺ concentrations result in reduced enzyme activity and poor yield, while high concentrations promote non-specific amplification and lower fidelity [23]. A titration of Mg²⁺ concentration (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0 mM) is recommended for optimization.

- Polymerase Selection: The choice of DNA polymerase depends on the application. Standard Taq polymerase is robust for routine screening but lacks proofreading activity. For applications requiring high fidelity, such as cloning or sequencing, use a high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., Pfu, KOD), which possesses 3'→5' exonuclease (proofreading) activity and can reduce error rates significantly [23].

- Enhancers and Additives: For challenging templates, such as those with high GC content (>65%), additives can be invaluable. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), used at 2–10%, helps resolve secondary structures by lowering the Tm of DNA [23] [14]. Betaine, at a final concentration of 1–2 M, homogenizes the thermodynamic stability of GC- and AT-rich regions, improving the amplification of long or GC-rich targets [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Primer Design and Preparation Workflow

Diagram 2: Primer Design and Preparation Workflow

Standard PCR Protocol

The following is a detailed methodology for setting up a conventional PCR reaction [17] [14].

Materials and Reagents Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Standard PCR

| Reagent | Final Concentration/Amount | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | 1–1000 ng (10^4–10^7 molecules) [14] | The target DNA to be amplified. |

| Forward & Reverse Primers | 0.1–1.0 µM (typically 20–50 pmol per reaction) [22] [14] | Bind complementary sequences to define amplicon. |

| dNTP Mix | 200 µM (50 µM of each dNTP) [14] | Building blocks for new DNA strands. |

| PCR Buffer (10X) | 1X | Provides optimal pH and salt conditions. |

| MgCl₂ (25 mM) | 1.5–2.5 mM (if not in buffer) [17] | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | 0.5–2.5 units per 50 µL reaction [17] | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands. |

| Sterile Water | Q.S. to final volume | - |

Procedure

Reaction Assembly: Thaw all reagents on ice. Assemble the reaction in a sterile, thin-walled 0.2 mL PCR tube on ice, in the following order to prevent premature reaction initiation:

- Sterile Water (to a final volume of 50 µL)

- 10X PCR Buffer: 5 µL

- dNTP Mix (10 mM): 1 µL

- Forward Primer (20 µM): 1 µL

- Reverse Primer (20 µM): 1 µL

- Template DNA: variable volume (e.g., 0.5 µL of 2 ng/µL genomic DNA)

- MgCl₂ (25 mM): variable volume (e.g., 2 µL for 2 mM final concentration, if needed)

- Taq DNA Polymerase: 0.5–1 µL

Note: For multiple reactions, prepare a Master Mix of all common components to minimize pipetting errors and ensure consistency [14].

Thermal Cycling: Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run the following standard program:

- Initial Denaturation: 94–95°C for 2–5 minutes (activates hot-start enzymes, fully denatures complex DNA).

- Amplification (25–40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94–95°C for 15–30 seconds.

- Annealing: X°C for 15–60 seconds (set 3–5°C below primer Tm; optimize via gradient PCR).

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per 1 kb of amplicon.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5–10 minutes to ensure all amplicons are fully extended.

- Hold: 4–10°C indefinitely.

Product Analysis: Analyze the PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. Mix 5–10 µL of the reaction with a DNA loading dye and load onto an agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide or a safer alternative. Visualize under UV light to confirm the presence of a single, sharp band of the expected size [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PCR

| Item | Category | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzyme | Reduces error rates for cloning/sequencing (e.g., Pfu, KOD) [23]. |

| Hot-Start Taq Polymerase | Enzyme | Prevents non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by requiring heat activation [23] [27]. |

| DMSO | Buffer Additive | Disrupts secondary structures in GC-rich templates [23] [14]. |

| Betaine | Buffer Additive | Equalizes DNA melting temperatures, aiding in long-range or GC-rich PCR [23]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent | Prevents degradation of primers and template. |

| dNTP Mix | Nucleotides | Provides the essential nucleotides for DNA synthesis. |

| Optimized MgCl₂ Solution | Cofactor | Titratable source of Mg²⁺ for fine-tuning reaction specificity and yield [23]. |

Executing PCR: A Step-by-Step Protocol and Diverse Applications

Within the broader scope of DNA amplification research, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) remains a foundational technique, enabling the exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences from minimal starting material [14] [21]. First introduced by Kary Mullis in 1983, this method leverages a thermostable DNA polymerase and thermal cycling to achieve millions of copies of a target DNA fragment, which is indispensable for subsequent genetic analysis [21] [28]. The reliability and sensitivity of standard PCR make it a cornerstone in diverse fields, including clinical diagnostics, forensic science, biomedical research, and drug development [21] [29]. This application note provides a detailed, actionable protocol for researchers, focusing on precise reagent formulation and optimized thermal cycling parameters to ensure robust and reproducible amplification results.

Principles of PCR

The core principle of PCR involves a repetitive, three-step cyclic process that leads to the exponential amplification of a target DNA sequence located between two primer binding sites [28]. The process begins with denaturation, where the double-stranded DNA template is heated to a high temperature (typically 94–98°C) to separate it into two single strands [7] [28]. Next, during annealing, the temperature is lowered to allow short, single-stranded DNA primers to bind (anneal) to their complementary sequences on either side of the target DNA [21] [28]. Finally, in the extension step, a thermostable DNA polymerase synthesizes a new DNA strand complementary to the template strand by adding nucleotides in the 5' to 3' direction [17] [28]. The power of PCR lies in the chain reaction; the newly synthesized DNA strands themselves become templates for subsequent cycles, leading to a theoretical doubling of the target sequence with each cycle, resulting in millions of copies after 25-35 cycles [28].

The following diagram illustrates this cyclical process and the exponential growth of DNA products.

Materials and Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A standard PCR reaction requires a specific set of components, each playing a critical role in the amplification process [14] [28]. The table below details these essential reagents, their specific functions, and their final concentrations in a typical 50 µL reaction.

| Reagent | Function | Final Concentration/Amount |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Template | Contains the target sequence to be amplified. | 1–1000 ng (104–107 molecules) [14] [21] |

| DNA Polymerase (e.g., Taq) | Thermally stable enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands. | 0.5–2.5 units per 50 µL reaction [17] [14] |

| Primers (Forward & Reverse) | Short oligonucleotides that define the start and end of the target sequence. | 20–50 pmol each (0.1–1.0 µM) [14] |

| Deoxynucleotides (dNTPs) | Building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for new DNA strands. | 200 µM of each dNTP [14] [28] |

| PCR Buffer | Provides optimal chemical environment (pH, salts) for polymerase activity. | 1X concentration (often supplied as 10X) [14] |

| Divalent Cations (MgCl₂) | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. | 1.5–2.0 mM (must be optimized) [14] [28] |

| Sterile Water | Solvent to bring the reaction to the final volume. | Q.S. to 50 µL [14] |

Reagent Setup and Optimization

For consistent results, it is crucial to prepare reactions carefully. When setting up multiple reactions, creating a Master Mix—a cocktail containing all common reagents except the template DNA—is highly recommended to minimize pipetting errors and ensure uniformity across samples [14]. The reagents should be thawed completely and kept on ice during setup [14]. A positive control (with a known, amplifiable template) and a negative control (with water instead of template) should always be included to verify reagent functionality and rule out contamination [14] [16].

Standard PCR Protocol and Cycling Conditions

Experimental Protocol: Reaction Setup and Thermal Cycling

Procedure:

- Reagent Preparation: On ice, assemble the following components in a sterile, thin-walled 0.2 mL PCR tube in the order listed, according to the volumes in Table 2 for a 50 µL reaction [14].

- Mixing: Gently mix the reaction by pipetting up and down 20 times. If using a thermal cycler without a heated lid, overlay the reaction mixture with 50 µL of mineral oil to prevent evaporation [17].

- Thermal Cycling: Place the tube in a thermal cycler and run the program based on the parameters in Table 3.

Table 2: Reagent Table for a Standard 50 µL PCR Reaction This table provides a detailed breakdown for setting up a single reaction. For multiple reactions, prepare a master mix.

| Component | Final Concentration/Amount | Volume for 1x Reaction (µL) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sterile Nuclease-free Water | Q.S. to 50 µL | 33.0 | Added first to ensure proper mixing. |

| 10X PCR Buffer | 1X | 5.0 | Supplied with enzyme; may contain Mg²⁺. |

| MgCl₂ (25 mM) | 1.5–2.0 mM | 0–2.0 | Omit if already in buffer; requires optimization [14]. |

| dNTP Mix (10 mM) | 200 µM each | 1.0 | Mixture of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP. |

| Forward Primer (20 µM) | 0.4 µM | 1.0 | Sequence-specific to target. |

| Reverse Primer (20 µM) | 0.4 µM | 1.0 | Sequence-specific to target. |

| DNA Template | 1–1000 ng | Variable (e.g., 0.5–5.0) | Amount depends on template complexity. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase (5 U/µL) | 1.25 U | 0.25 | Add last to avoid degradation. |

| Total Volume | 50.0 |

Table 3: Standard PCR Thermal Cycling Conditions These parameters are typical for Taq DNA polymerase and a 0.1–1.0 kb amplicon. Optimization may be required [17] [7].

| Step | Temperature | Time | Cycles | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 94–95 °C | 2–5 minutes | 1 | Complete separation of dsDNA template; activation of hot-start enzymes. |

| Cycling | 25–35 | |||

| Denaturation | 94–95 °C | 20–30 seconds | Melts DNA before each cycle. | |

| Annealing | 50–65 °C* | 20–40 seconds | Primer binding to template. | |

| Extension | 72 °C | 1 minute per kb | DNA synthesis. | |

| Final Extension | 72 °C | 5–10 minutes | 1 | Ensures all amplicons are full-length. |

| Final Hold | 4–15 °C | ∞ | 1 | Short-term storage of products. |

*The annealing temperature is critical and is typically calculated 3–5°C below the primer's melting temperature (Tm). A gradient thermal cycler is ideal for optimization [7].

Post-Amplification Analysis

Following PCR, analyze the amplified products (amplicons) by agarose gel electrophoresis [17] [21].

- Prepare a 1–2% agarose gel in an appropriate buffer containing a DNA-intercalating dye.

- Mix a portion of the PCR product with a loading dye and load into the gel alongside a DNA molecular weight ladder.

- Run the gel at a constant voltage until sufficient separation is achieved.

- Visualize the DNA bands under ultraviolet light. A single, sharp band of the expected size indicates specific amplification.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Even with a standard protocol, PCR can fail. The table below outlines common problems, their potential causes, and solutions [14] [16].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Product | Inhibitors in template, insufficient cycles, incorrect annealing temperature. | Purify template DNA; increase cycles (up to 40); lower annealing temperature in 2°C increments [16]. |

| Non-specific Bands/Smearing | Annealing temperature too low, excess primers/template, too many cycles. | Increase annealing temperature; reduce amount of primers/template; reduce cycle number [16]. |

| Primer-Dimer Formation | Primer 3' ends complementary, annealing temperature too low. | Redesign primers to avoid 3' complementarity; increase annealing temperature [14] [16]. |

For challenging templates like GC-rich sequences (>65% GC content), additives such as DMSO (1–10%), formamide (1.25–10%), or betaine (0.5 M to 2.5 M) can be included in the reaction to facilitate denaturation and improve yield and specificity [14] [7] [16].

The standard PCR protocol detailed herein provides a reliable framework for the robust amplification of target DNA sequences. The critical factors for success are the use of high-quality, optimized reagents and precisely controlled thermal cycling parameters. By understanding the function of each component and systematically troubleshooting common issues, researchers can adapt this foundational protocol to a wide array of applications, from basic gene analysis to advanced clinical and drug development research. The reproducibility and sensitivity of PCR solidify its status as an indispensable tool in the molecular biologist's arsenal.

The evolution of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) from a simple DNA amplification technique to a sophisticated quantitative and analytical tool has revolutionized molecular biology and clinical diagnostics. While conventional end-point PCR provides qualitative analysis by detecting the final amplified product via gel electrophoresis, advanced PCR variations offer greater precision, quantification, and multiplexing capabilities essential for contemporary research and diagnostic applications [30]. These advanced methods include Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR), quantitative PCR (qPCR), multiplex PCR, and long-range PCR, each addressing specific experimental needs across diverse scientific disciplines.

The selection of an appropriate PCR method depends on multiple factors including the starting material (DNA or RNA), required quantification precision, number of targets, and amplicon length. This article provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for these advanced PCR variations, framed within the context of optimizing DNA amplification research for drug development and clinical diagnostics. We present standardized protocols, troubleshooting guidelines, and comparative analyses to facilitate implementation of these techniques in research settings.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and Real-Time PCR

Principles and Applications

Quantitative PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, enables researchers to measure DNA amplification as it occurs through fluorescent detection systems. Unlike conventional PCR that provides results only after completion of all amplification cycles, qPCR monitors fluorescence after each cycle, allowing precise quantification of initial template amounts [30]. The fundamental principle involves tracking the fluorescence intensity that reflects the current amount of DNA amplicons throughout the amplification process. During initial cycles, fluorescence remains at background levels, but eventually reaches a point where it increases above detectable levels—termed the quantification cycle (Cq) or threshold cycle (Ct)—which correlates proportionally with the initial number of template molecules in the sample [30].

qPCR provides either absolute quantification using standard curves constructed from serial dilutions of samples with known concentrations, or relative quantification when comparing expression levels between samples. The technique has become indispensable for gene expression analysis, pathogen detection, genetic testing, and disease research [31]. Its superior quantification capabilities, higher resolution, and faster processing compared to end-point PCR make it particularly valuable for applications requiring precise measurement of nucleic acid concentrations [30].

Detailed qPCR Protocol and Optimization

Stepwise Optimization Protocol: Achieving accurate and reproducible qPCR results requires meticulous optimization of several parameters. A stepwise optimization approach should include primer sequence refinement, annealing temperature calibration, primer concentration titration, and cDNA concentration range determination [32]. The optimal conditions are achieved when a standard cDNA concentration curve demonstrates R² ≥ 0.9999 and amplification efficiency (E) = 100 ± 5% for the best primer pair of each gene [32] [33]. This level of optimization is prerequisite for reliable application of the 2–ΔΔCT method for data analysis.

Primer Design Considerations: Primers for qPCR should ideally span an exon-exon junction, with one amplification primer potentially spanning the actual exon-intron boundary [31]. This design strategy reduces false positives from contaminating genomic DNA, as intron-containing genomic sequences would not be amplified efficiently. When primers cannot be designed across exon boundaries or exon-intron junctions, treatment of RNA samples with RNase-free DNase I or dsDNase is necessary to remove contaminating genomic DNA [31].

Essential Controls: All qPCR experiments should include a minus reverse transcriptase control ("no RT" control) containing all reaction components except the reverse transcriptase [31]. This control tests for contaminating DNA, as no amplification should occur without reverse transcription. If amplification is detected in this control, it indicates presence of contaminating DNA that must be addressed before proceeding with experimental samples.

qPCR Troubleshooting Guide

Common qPCR issues and their solutions include:

- Poor Amplification Efficiency: Often caused by PCR inhibitors or suboptimal primer design. Dilute template prior to standard curve generation to find ideal Ct range. Verify primer specificity using BLAST and include a melt curve to confirm single product formation [34].

- Inconsistent Biological Replicates: May indicate RNA degradation or minimal starting material. Check RNA concentration and quality with spectrophotometry (ideal 260/280 ratio: 1.9-2.0) and run on agarose gel to detect degradation [34].

- Amplification in No Template Control (NTC): Caused by reagent contamination or primer-dimer formation. Clean work area and pipettes with 70% ethanol, prepare fresh primer dilutions, and add a dissociation curve to detect primer-dimer formation [34].

- Unexpected Ct Values: May result from incorrect thermal cycling conditions or sample evaporation. Verify thermal cycling protocol before runs and ensure tube caps are properly sealed to prevent evaporation during storage [34].

Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

Principles and Applications

Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) combines reverse transcription of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) with amplification of specific cDNA targets. The key difference from standard PCR is the starting material—RT-PCR uses purified RNA as a template to generate cDNA, which is then amplified [30]. This technique enables detection and quantification of RNA molecules, making it invaluable for gene expression analysis, viral load detection, and studying RNA virus infections.

RT-PCR can be performed using either one-step or two-step approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations [31]. The decision between these approaches depends on experimental requirements, including throughput, sensitivity needs, and number of targets to be analyzed from each sample.

Detailed RT-PCR Protocol

One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-PCR: The one-step approach combines reverse transcription and PCR in a single tube and buffer, using both reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase [31]. This method utilizes only sequence-specific primers, resulting in less experimental variation, fewer pipetting steps (reducing contamination risk), and higher reproducibility, making it suitable for high-throughput applications [31]. However, it offers less flexibility as reaction conditions represent a compromise between the two enzymatic steps, potentially reducing sensitivity and the number of detectable targets per sample.

In the two-step approach, reverse transcription and PCR are performed in separate tubes with different optimized buffers and reaction conditions [31]. This method generates stable cDNA pools that can be stored for extended periods and used for multiple reactions, allows amplification of both target and reference genes from the same cDNA pool without multiplexing, and provides flexible priming options [31]. The main disadvantages include increased risk of contamination due to additional handling steps, longer processing time, and greater optimization requirements.

Reverse Transcription Primer Selection: Four different priming strategies are available for cDNA synthesis:

- Oligo(dT) Primers: Stretches of thymine residues that anneal to the poly(A) tail of mRNA, producing full-length cDNA but with bias toward the 3' end [31].

- Random Primers: Short (6-9 base) oligonucleotides that anneal at multiple points along RNA transcripts, enabling amplification of all RNA types including those without poly(A) tails but potentially producing truncated cDNA [31].

- Sequence-Specific Primers: Custom primers targeting specific mRNA sequences, generating specific cDNA pools with increased sensitivity but limited to one gene of interest [31].

- Combined Approaches: Often, mixtures of oligo(dT) and random primers are used to diminish generation of truncated cDNAs and improve reverse transcription efficiency [31].

Template Considerations: Researchers must decide whether to use total RNA or mRNA as the starting material. While mRNA may provide slightly greater sensitivity, total RNA is often preferred because it requires fewer purification steps (ensuring more quantitative recovery), facilitates better normalization to starting cell numbers, and avoids skewed results from differential mRNA recovery yields [31].

Table 1: Comparison of One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-PCR Approaches

| Parameter | One-Step RT-PCR | Two-Step RT-PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Procedure | Reverse transcription and PCR in single tube | Separate tubes for reverse transcription and PCR |

| Handling Time | Faster with fewer pipetting steps | More time-consuming with additional steps |

| Risk of Contamination | Lower | Higher due to multiple handling steps |

| cDNA Stability | Not applicable - direct amplification | Stable cDNA pool stored for future use |

| Flexibility | Limited - conditions compromised for both reactions | High - optimized conditions for each step |

| Throughput | Suitable for high-throughput applications | Lower throughput |

| Sensitivity | Potentially lower due to compromised conditions | Higher with optimized conditions for each step |

| Priming Options | Limited to sequence-specific primers | Multiple options: oligo(dT), random, or gene-specific |

Multiplex PCR

Principles and Applications

Multiplex PCR enables simultaneous amplification of multiple targets in a single reaction tube, using different primer pairs targeting distinct sequences. This approach conserves precious samples, reduces reagent costs, and increases throughput—particularly beneficial when sample material is limited [35]. The technique requires careful optimization to ensure comparable amplification efficiency for all targets while minimizing primer-dimer formation and nonspecific amplification.

Advanced multiplex PCR applications now achieve remarkable multiplicity, with some systems capable of amplifying over 100 targets simultaneously [36]. For example, optimized multiplex PCR-next-generation sequencing (NGS) approaches have been developed for comprehensive HLA genotyping, simultaneously targeting HLA-A, -B, -C, -DPB1, -DQB1, and -DRB1 loci in a single reaction [37]. Such high-plex applications require sophisticated primer design tools and careful optimization to ensure uniform coverage across all targets.

Detailed Multiplex PCR Protocol

Primer Design and Compatibility: Successful multiplex PCR requires primers that work harmoniously without forming secondary structures or primer-dimers. Ultiplex, a web-based multiplex primer design tool, facilitates batch design and compatibility checking by excluding mutual secondary structures and false alignments across the genome [36]. This tool offers flexible parameters for users to define references, primer Tm values, product lengths, plex numbers, and tag oligos, significantly simplifying the primer design process for complex multiplex assays.

Reaction Optimization: Commercial multiplex PCR kits, such as the QIAGEN Multiplex PCR Kit, incorporate specialized components to enhance performance. These include HotStarTaq DNA Polymerase for reduced nonspecific amplification during setup, and unique PCR buffers containing additives like Factor MP that increase local primer concentration at the template and stabilize specifically bound primers [35]. The kit also provides Q-Solution, a proprietary additive that facilitates amplification of difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich sequences) by modifying DNA melting behavior, used at a single working concentration without toxicity concerns [35].

Thermal Cycling Conditions: Standard thermal cycling parameters for multiplex PCR begin with a 15-minute incubation at 95°C to activate the hot-start polymerase, followed by 30-35 cycles of denaturation (98°C for 20 seconds), annealing (63°C for 1 minute), and extension (72°C for 5 minutes), with a final extension at 72°C for 5-10 minutes [35] [37]. These conditions may require adjustment based on specific primer characteristics and target sequences.

Application-Specific Implementation: In HLA genotyping applications, multiplex PCR primers are designed to target specific loci with varying concentrations in the primer mix (e.g., HLA-A: 0.04 μM, HLA-B: 0.1 μM, HLA-C: 0.15 μM, HLA-DQB1: 0.18 μM, HLA-DRB1: 0.07 μM, HLA-DPB1: 0.04 μM) to balance amplification efficiency across targets [37]. This careful balancing ensures uniform coverage across all loci despite sequence differences and varying amplification efficiencies.

Long-Range PCR

Principles and Applications

Long-range PCR enables amplification of significantly longer DNA fragments than conventional PCR—up to 20 kb from human genomic DNA and up to 40 kb from λDNA [38]. This capability is particularly valuable for applications requiring analysis of large genomic regions, including genetic disorder diagnostics, haplotype phasing, and structural variant detection. The technique employs specialized enzyme mixtures, typically combining thermostable Taq DNA polymerase with a proofreading DNA polymerase to enhance processivity and accuracy over extended templates [38].