Supertree vs. Supermatrix Methods for Prokaryotic Phylogeny: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

The reconstruction of accurate prokaryotic phylogenies is fundamental for understanding microbial evolution, tracing pathogen outbreaks, and identifying new drug targets.

Supertree vs. Supermatrix Methods for Prokaryotic Phylogeny: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

The reconstruction of accurate prokaryotic phylogenies is fundamental for understanding microbial evolution, tracing pathogen outbreaks, and identifying new drug targets. This article provides a systematic comparison of two primary phylogenetic approaches: the supertree method, which combines pre-calculated gene trees, and the supermatrix method (combined analysis), which concatenates multiple sequence alignments. We explore the foundational principles, methodological workflows, and specific applications of both strategies for analyzing prokaryotic genomes, which are often complicated by horizontal gene transfer. Drawing on current literature and simulation studies, we evaluate their relative performance in accuracy, computational efficiency, and robustness to systematic error. This guide is tailored for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to select and optimize phylogenetic methods for genomic studies, pathogen evolution tracking, and the discovery of novel antimicrobial agents.

The Foundations of Prokaryotic Phylogeny: Why Genomic Data Poses Unique Challenges

The Shift from Phenotype to Genotype in Prokaryotic Classification

The classification of prokaryotes has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from a foundation based on observable phenotypic characteristics to one rooted in genomic data. This paradigm shift has moved microbial taxonomy from a system heavily reliant on morphological, biochemical, and physiological traits to one that utilizes conserved, information-bearing macromolecules to reveal evolutionary relationships [1]. The early classification system, exemplified by Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, initially categorized bacteria into nested hierarchical classifications based on keys and tables of distinguishing characteristics [1]. However, phenotypic properties provided little insight into deep evolutionary relationships, creating a classification impasse that persisted for decades [1].

The breakthrough came with the recognition that informational macromolecules could act as molecular clocks, inspired by the work of Zuckerkandl and Pauling [1]. Carl Woese's pioneering use of small subunit ribosomal RNA (16S/18S rRNA) as a molecular chronometer provided the first objective evolutionary framework across the tree of life, leading to the revolutionary discovery of Archaea as a distinct domain [1]. The 16S rRNA gene became instrumental not only in revealing deep phylogenetic relationships but also in highlighting the enormous microbial diversity missed by traditional culturing methods [1]. We now stand at a turning point where genome sequences form the basis of a robust phylogenetic framework, enabling a comprehensive classification of prokaryotes that reflects their evolutionary history with unprecedented resolution [1].

Methodological Framework: Supermatrix vs. Supertree Approaches

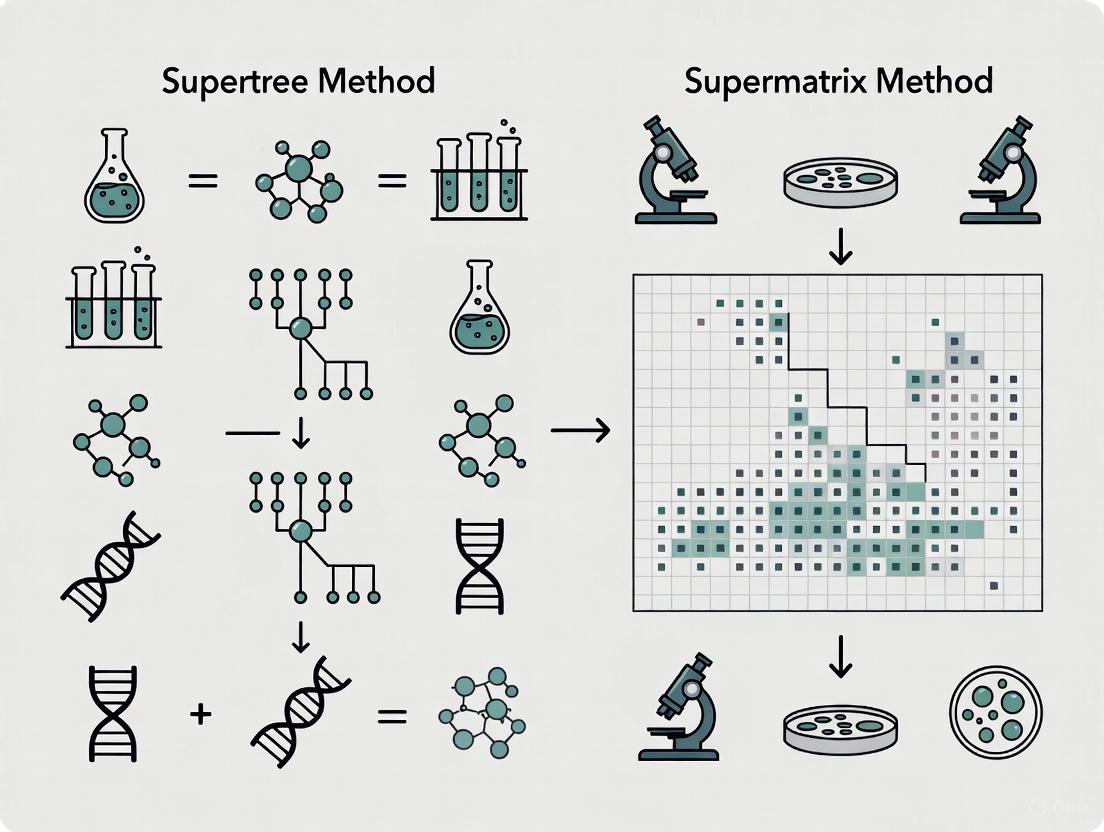

In the genomic era, two primary computational approaches have emerged for reconstructing evolutionary relationships from large gene collections: the supermatrix (SM) and supertree (ST) methods [2]. Both represent distinct philosophical and methodological frameworks for handling the complex data generated by modern genomics.

The supermatrix approach, also known as the concatenation approach, involves combining multiple gene sequences into a single aligned data matrix [3]. This method reduces stochastic errors by combining weak phylogenetic signals from different genes, effectively generating a large, unified dataset for phylogenetic analysis [2]. The supermatrix method typically employs heuristic tree searches on the combined dataset, often producing significantly shorter trees under the parsimony criterion compared to supertree approaches [4].

The supertree approach takes a different strategy, first inferring phylogenetic trees from individual genes and then deriving an optimal consensus tree from these individual phylogenies [3] [2]. This method prevents the combination of genes with incompatible phylogenetic histories and can be easily parallelized in practice, requiring less memory than the supermatrix approach [2]. However, supertree methods can suffer from limitations including the misinterpretation of secondary phylogenetic signals and unclear logical basis for node robustness measures [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Supermatrix and Supertree Methodological Approaches

| Feature | Supermatrix (SM) | Supertree (ST) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Handling | Concatenates genes into single alignment | Analyzes genes separately then combines trees |

| Computational Demand | Higher memory requirements | Lower memory needs, easily parallelized |

| Handling Conflicting Signals | May combine genes with incompatible histories | Prevents combination of incompatible phylogenetic histories |

| Primary Advantage | Reduces stochastic errors by combining weak signals | Does not require all genes to be present in every genome |

| Typical Tree Search Method | Heuristic search on combined dataset (e.g., TNT) | Consensus tree from individual gene trees |

| Reported Tree Length | Significantly shorter trees under parsimony criterion [4] | Longer trees under parsimony criterion [4] |

Experimental Comparisons: Performance and Accuracy Metrics

Several empirical studies have directly compared the performance of supermatrix and supertree methods using both simulated and organismal datasets. These comparisons have evaluated multiple criteria including topological accuracy, computational efficiency, and sensitivity to different phylogenetic methods.

In one significant study using twenty multilocus datasets, supermatrix searches produced significantly shorter trees than either supertree approach (SuperFine or SuperTriplets; p < 0.0002 in both cases) when using the parsimony criterion [4]. Moreover, the processing time of supermatrix search was significantly lower than SuperFine combined with locus-specific search (p < 0.01) but roughly equivalent to that of SuperTriplets with locus-specific search (p > 0.4, not significant) [4]. This research concluded that for real organismal data rather than simulated data, there was no basis in either time tractability or tree length for using supertrees over heuristic tree search with a supermatrix for phylogenomics [4].

The SuperTRI approach, a supertree method that incorporates branch support analyses of independent datasets, has shown less sensitivity to different phylogenetic methods (Bayesian inference, maximum likelihood, and unweighted and weighted maximum parsimony) compared to supermatrix approaches [3]. This method assesses node reliability using three measures: the supertree Bootstrap percentage, mean branch support from separate analyses, and a reproducibility index [3]. When applied to a data matrix including seven genes for 82 taxa of the family Bovidae, SuperTRI proved more accurate for interpreting relationships among taxa and provided insights into introgression and radiation phenomena [3].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Supermatrix vs. Supertree Methods

| Performance Metric | Supermatrix | Supertree | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tree Length (Parsimony) | Significantly shorter [4] | Longer [4] | 20 multilocus datasets |

| Computational Time | Significantly faster than SuperFine [4] | Slower (SuperFine) [4] | Real organismal data |

| Method Sensitivity | Higher sensitivity to phylogenetic methods [3] | Lower sensitivity (SuperTRI) [3] | Bovidae family (82 taxa, 7 genes) |

| Handling Incomplete Data | Requires complete data or imputation | Naturally handles missing data [2] | Prokaryotic phylogenomics |

| Topological Accuracy | High with dominant species-tree signal [3] | More accurate with conflicting signals (SuperTRI) [3] | Simulation and empirical studies |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Core Gene Identification and Alignment (EasyCGTree Pipeline)

The EasyCGTree pipeline provides a standardized workflow for prokaryotic phylogenomic analysis based on core gene sets [2]. The protocol begins with input preparation, requiring FASTA or multi-FASTA-formatted amino acid sequences from prokaryotic genomes as input [2]. The pipeline then performs gene calling using profile hidden Markov models (HMMs) of core gene sets, with several pre-prepared HMM databases available including bac120 (120 ubiquitous bacterial genes), ar122 (122 archaeal genes), UBCG (92 up-to-date bacterial core genes), and essential (107 essential single-copy bacterial core genes) [2].

Homolog searching is conducted using hmmsearch from the HMMER package with a default E-value threshold of 1e-10 [2]. The top hit for each gene is screened based on the E-value threshold, followed by filtration to exclude genomes with insufficient detected genes and genes with low prevalence [2]. Multiple sequence alignment is then performed using MUSCLE (Windows) or Clustal Omega (Linux), followed by alignment trimming using trimAl with automatic methods (gappyout, strict, or strictplus) for conserved segment selection [2].

Supermatrix Construction and Analysis

For supermatrix inference, the EasyCGTree pipeline generates a concatenation of each trimmed alignment, which is then used to reconstruct a maximum-likelihood phylogeny using either FastTree or IQ-TREE [2]. FastTree is recommended for initial analysis due to its faster speed and lower memory requirements, while IQ-TREE is preferred for accuracy when computational resources permit [2]. The supermatrix approach allows the combination of weak phylogenetic signals from different genes, reducing stochastic errors through concatenation [2].

Supertree Construction Methods

For supertree construction, EasyCGTree employs wASTRAL to derive an optimal tree from individual gene trees [2]. This approach does not require all genes to be present in every genome, making it particularly suitable for datasets with uneven gene representation [2]. The supertree method prevents the combination of genes with incompatible phylogenetic histories, which is valuable when analyzing genomes with different evolutionary histories due to horizontal gene transfer [2].

Alternative supertree methods like the BUILD algorithm, used by the Open Tree of Life (OToL) project, determine compatibility of different phylogenetic groupings through iterative assessment [5]. The BUILD algorithm is a recursive approach that determines if a set of rooted triplets or splits are jointly compatible by creating cluster graphs at each recursive level [5]. Recent optimizations include an incrementalized version (BuildInc) that shares work between successive calls, providing up to 550-fold speedup for supertree algorithms [5].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Prokaryotic Phylogenomics

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| EasyCGTree [2] | Software Pipeline | Infers genome-scale maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees using SM and ST | User-friendly, cross-platform prokaryotic phylogenomics |

| HMMER [2] | Software Package | Homolog searching using profile hidden Markov models | Identifying core genes in genomic datasets |

| IQ-TREE [2] | Phylogenetic Software | Maximum-likelihood tree inference | High-accuracy phylogeny reconstruction from supermatrix |

| FastTree [2] | Phylogenetic Software | Approximately maximum-likelihood tree inference | Rapid phylogeny reconstruction for large datasets |

| trimAl [2] | Alignment Tool | Automated alignment trimming and conserved segment selection | Preprocessing alignments for phylogenetic analysis |

| wASTRAL [2] | Supertree Software | Consensus tree construction from individual gene trees | Supertree inference in EasyCGTree pipeline |

| Bac120/Ar122 [2] | HMM Profile Database | Core gene sets for Bacteria and Archaea | Phylogenomic analysis across prokaryotic domains |

| UBCG [2] | HMM Profile Database | 92 up-to-date bacterial core genes | Standardized bacterial phylogenomics |

| BUILD/BuildInc [5] | Algorithm | Determines compatibility of phylogenetic groupings | Supertree construction in Open Tree of Life project |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

The shift to genotype-based prokaryotic classification has profound implications for drug discovery and biomedical research. Genomic approaches enable the identification and targeting of specific microbial pathogens with unprecedented precision, facilitating the development of highly specific therapeutic agents [6]. phage display technology, which allows the selection of peptides that bind to biologically relevant sites on target proteins, has become a powerful tool for identifying receptor agonists and antagonists [6] [7].

Membrane receptors, which comprise more than 60% of drug targets, are particularly amenable to phage display approaches [6]. The technique enables the screening of combinatorial peptide libraries against membrane receptors to discover novel pharmacologically active compounds, even without previous knowledge of the target structure [6]. Peptides derived from phage display screenings often modulate target protein activity and can serve as lead compounds in drug design [6]. Furthermore, the identification of tumor antigens through phage display has advanced cancer diagnosis and therapeutic targeting [7].

Antibody phage display has revolutionized antibody drug discovery, enabling the rapid selection and evolution of human antibodies for therapeutic applications [7]. This approach has led to the development of fully human antibodies like adalimumab, which achieved annual sales exceeding $1 billion, demonstrating the commercial and therapeutic impact of these technologies [7]. The combination of precise prokaryotic classification and targeted therapeutic development represents a powerful synergy for addressing microbial pathogenesis and other disease processes.

The shift from phenotype to genotype in prokaryotic classification has fundamentally transformed microbial taxonomy, enabling a comprehensive evolutionary framework that reflects the true relationships between organisms. Both supermatrix and supertree approaches offer distinct advantages for different research contexts, with supermatrix methods generally providing greater computational efficiency and supertree approaches offering better handling of conflicting phylogenetic signals and incomplete datasets.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between these methods should be guided by specific research questions, data characteristics, and computational resources. Supermatrix approaches may be preferable for standardized analyses with complete datasets, while supertree methods offer flexibility for integrating diverse data types and handling genomic complexity. As computational methods continue to advance, particularly with optimized algorithms like BuildInc providing orders-of-magnitude speed improvements, the integration of these approaches will likely yield even more powerful tools for unraveling prokaryotic evolutionary history and leveraging this knowledge for therapeutic development.

Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT), the non-vertical transmission of genetic material between organisms, presents a fundamental challenge to accurate phylogenetic tree reconstruction, particularly in prokaryotes. Unlike vertical inheritance, which follows a tree-like pattern of descent, HGT creates complex networks of evolutionary relationships that can obscure the true evolutionary history of species. When significant HGT occurs between lineages, different genomic regions can exhibit conflicting phylogenetic histories, making it difficult to infer a single, representative species tree. This challenge is especially acute in microbiology, where HGT is pervasive and serves as a major mechanism for niche adaptation and phenotypic innovation, such as the acquisition of antibiotic resistance and pathogenicity determinants [8]. Consequently, phylogenetic methods must effectively reconcile these conflicting signals to produce accurate evolutionary frameworks.

The two predominant approaches for large-scale phylogenetic inference—supertree (ST) and supermatrix (SM) methods—differ fundamentally in how they handle data and, by extension, how they cope with the discordance caused by HGT. The supermatrix approach concatenates multiple gene alignments into a single large matrix from which a phylogeny is inferred, effectively combining weak phylogenetic signals across genes. In contrast, the supertree approach first infers trees from individual genes or data sets and then combines these source trees into a consensus supertree [3] [2]. This critical difference in methodology leads to varying performance and suitability when facing data sets characterized by extensive HGT.

Performance Comparison: How Supertree and Supermatrix Methods Handle HGT

Theoretical and empirical studies reveal distinct performance characteristics for supertree and supermatrix methods under conditions of gene tree discordance, including that caused by HGT. The table below summarizes the key attributes of each approach relevant to managing HGT-induced conflict.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Supertree and Supermatrix Methods in the Context of HGT

| Feature | Supertree (ST) Methods | Supermatrix (SM) Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Combines independent gene trees into a consensus species tree [2]. | Concatenates gene alignments into a single matrix before tree inference [2]. |

| Handling Gene Discordance | Does not force a single history on all genes; can reveal conflicting signals [3]. | Assumes a dominant, single tree signal for all concatenated genes [3]. |

| Theoretical Robustness | Quartet-based methods (e.g., ASTRAL) are statistically consistent under both ILS and bounded HGT models [9]. | Concatenation can be inconsistent under multi-species coalescent models with ILS; less robust to high HGT rates [9]. |

| Key Advantage | Prevents combining genes with incompatible phylogenetic histories [2]. | Reduces stochastic errors by combining weak phylogenetic signals [2]. |

| Key Limitation | Early methods often ignored secondary phylogenetic signals [3]. | Can be misleading if the species-tree signal is not dominant after data combination [3]. |

| Computational Memory | Generally requires less memory than SM approaches [2]. | Often requires more memory, especially with large concatenated alignments [2]. |

A significant theoretical advantage of some modern supertree methods, particularly quartet-based approaches like ASTRAL, is their proven statistical consistency not only under the Multi-Species Coalescent (MSC) model of Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS) but also under models of phylogenomics that include bounded amounts of HGT [9]. This means that as more data is added, the method will converge on the correct species tree even when HGT is present, provided the rate of transfer is not unlimited. In contrast, concatenation-based supermatrix analyses, while often accurate under low HGT rates, have been shown to be less robust and can produce misleading results when HGT rates are high [9].

Experimental Data: Benchmarking Methods with Simulated and Empirical Data

Benchmarking studies using simulated and empirical datasets provide quantitative evidence for the performance of these methods under realistic evolutionary scenarios. The following table compiles key findings from such evaluations, offering a data-driven perspective.

Table 2: Experimental Accuracy of Phylogenetic Methods Under HGT and ILS

| Study Focus | Test Conditions | Method(s) | Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenomics with HGT/ILS [9] | Simulated data with moderate ILS & varying HGT. | ASTRAL-2, wQMC | "Highly accurate, even on datasets with high rates of HGT." |

| NJst, Concatenation (ML) | "Highly accurate under low HGT," but "less robust to high HGT rates." | ||

| SuperTRI Assessment [3] | 7 genes, 82 Bovidae taxa. | SuperTRI (ST-based) | Showed "less sensitivity" to four phylogenetic methods (Bayesian, ML, MP). More accurate for taxon relationships. Enabled conclusions on introgression/radiation. |

| Chrono-STA [10] | Input trees with minimal species overlap. | ASTRAL-III, ASTRID, FastRFS | Could not recover true topology due to "minimal taxonomic overlap." |

| Chrono-STA (time-based ST) | Successfully produced correct supertree using divergence times. |

The experimental data underscores that no single method is universally superior, but the context is critical. For datasets where HGT is a major factor, quartet-based supertree methods demonstrate a clear advantage in robustness. Furthermore, novel supertree approaches like SuperTRI, which incorporates branch support analyses from multiple independent datasets, provide a more nuanced framework for assessing node reliability and identifying evolutionary processes like introgression that cause gene tree conflict [3].

Protocols for Phylogenetic Comparison and HGT Detection

To objectively compare supertree and supermatrix methods or to investigate HGT, researchers can follow established experimental workflows. The diagram below outlines a generalized protocol for a comparative phylogenomic study.

Figure 1: A general workflow for comparing supertree and supermatrix methods.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

- Core Gene Identification: Input proteomes (FASTA-formatted amino acid sequences) are searched against a Profile HMM Database (PHD) using

hmmsearchfrom the HMMER suite. Common bacterial core gene sets includebac120(120 genes) orUBCG(92 genes) [2]. An E-value threshold (e.g.,1e-10) is used to identify significant hits, and the top hit for each gene per genome is retained. - Multiple Sequence Alignment & Trimming: Homologous sequences for each core gene are aligned using tools like MUSCLE or Clustal Omega. The resulting multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) are then trimmed to remove poorly aligned regions using trimAl. The

strictplusalgorithm is often recommended as it automatically selects conserved blocks based on the MSA's features, improving phylogenetic signal [2]. - Phylogenetic Inference:

- Supermatrix Pathway: The individual, trimmed gene alignments are concatenated into a single supermatrix. A maximum-likelihood tree is then inferred from this matrix using programs like IQ-TREE (recommended for accuracy) or FastTree (recommended for speed on very large datasets) [2].

- Supertree Pathway: A maximum-likelihood tree is inferred from each individual, trimmed gene alignment. These gene trees are then used as input to a consensus supertree method. wASTRAL is a commonly used implementation for this purpose [2].

- HGT Detection Protocol: To identify HGT events that cause the discordance assessed above, a phylogenetic approach is robust. This involves reconstructing a trusted species tree (e.g., using a quartet-based method) and then comparing it to the phylogenies of individual genes. Genes whose trees show a statistically significant conflict with the species tree (e.g., assessed using likelihood-based tests) are considered HGT candidates [8]. Parametric methods, which scan for deviations in genomic signatures like GC content, can complement this by identifying recent transfers without the need for a reference species tree [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Successful phylogenomic analysis relies on a suite of computational tools and databases. The following table lists key resources for implementing the protocols described above.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Phylogenomics

| Item Name | Type/Category | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Core Gene Sets (bac120, UBCG) [2] | Profile HMM Database | Pre-defined sets of conserved, single-copy genes used as phylogenetic markers for initial homolog searching. |

| HMMER [2] | Software Suite | Contains hmmsearch, used to identify homologous sequences in proteomes against a Profile HMM Database. |

| trimAl [2] | Bioinformatics Tool | Trims multiple sequence alignments to remove poorly aligned positions and select conserved blocks, improving phylogenetic signal. |

| IQ-TREE [2] | Phylogenetic Software | Infers maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees from alignments; noted for high accuracy and model selection. |

| ASTRAL/wASTRAL [9] [2] | Supertree Software | Estimates a species tree from a set of input gene trees using quartet coalescent methods. Robust to ILS and some HGT. |

| EasyCGTree [2] | Integrated Pipeline | An all-in-one pipeline that automates the workflow from proteome input to both supermatrix and supertree inference. |

| Reference Timetrees (TimeTree) [10] | Data Resource | Databases of published divergence times; can be used for calibration or as input for chronological supertree methods like Chrono-STA. |

The central challenge of HGT in tree reconstruction has significantly shaped the development and evaluation of phylogenetic methods. While the supermatrix approach remains a powerful and widely used tool, evidence from theoretical proofs and empirical benchmarks indicates that supertree methods, particularly quartet-based approaches like ASTRAL, offer superior robustness in the face of gene tree discordance caused by HGT and ILS [9]. The choice between methods should be informed by the biological context—specifically the expected rate of HGT in the taxa under study.

Future progress will likely come from enhanced supertree algorithms that more explicitly model the processes causing discordance, such as the SuperTRI framework which integrates branch support to better assess node reliability [3]. Furthermore, the integration of chronological data, as seen in Chrono-STA, offers a promising avenue for building comprehensive trees of life from datasets with limited taxonomic overlap [10]. As phylogenomics continues to mature, the synergy between sophisticated supertree methods and scalable, automated pipelines like EasyCGTree [2] will empower researchers to reconstruct increasingly accurate and meaningful evolutionary histories, even in the complex web of life woven by horizontal gene transfer.

Single-gene phylogenies, which reconstruct evolutionary relationships based on one genetic locus, present fundamental limitations for understanding prokaryotic evolution. These phylogenies often yield conflicting topologies due to factors like horizontal gene transfer (HGT), incomplete lineage sorting, and differential evolutionary rates across genes [11]. The inherent conflict between individual gene histories and the organismal lineage creates a central challenge for reconstructing a coherent evolutionary history, particularly in prokaryotic systems where HGT is prevalent [11].

The inadequacy of single-gene approaches has driven the development of methods that incorporate information from multiple genetic loci. Two primary methodologies have emerged: the supermatrix approach (concatenating multiple gene sequences into a single alignment) and the supertree approach (combining individual gene trees into a comprehensive phylogeny) [12] [11]. This article objectively compares the performance of these two methods within prokaryotic phylogeny research, providing experimental data and analytical frameworks to guide researchers in selecting appropriate methodologies for their specific research contexts.

Supermatrix vs. Supertree Methods: A Systematic Comparison

Core Conceptual Differences

The supermatrix and supertree methods represent philosophically distinct approaches to reconciling gene tree discordance. Supermatrix methods involve concatenating multiple gene alignments into a single large alignment from which a species tree is directly inferred, effectively averaging phylogenetic signals across all included loci [11]. In contrast, supertree methods first infer individual trees from each gene or locus separately, then use various algorithms to combine these separate trees into a comprehensive species tree [12].

Each approach carries different implications for handling genomic data. Supermatrix approaches typically require complete or nearly complete data across all taxa, which can limit dataset size, while supertree methods can accommodate datasets with missing sequences for some genes in some taxa [12]. However, this flexibility comes with potential costs to accuracy, as the initial separate analyses may propagate errors into the final combined tree.

Performance Comparison with Organismal Datasets

Empirical comparisons using real organismal datasets provide critical insights into the relative performance of these methods. A systematic evaluation of 20 multilocus datasets compared tree length under the parsimony criterion and computational time for supertree (SuperFine and SuperTriplets) and supermatrix (heuristic search in TNT) approaches [12].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Supermatrix and Supertree Methods on 20 Multilocus Datasets

| Method | Tree Length (Parsimony) | Processing Time | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supermatrix (TNT) | Significantly shorter trees | Lower than SuperFine + locus-specific search | P < 0.0002 for tree length superiority |

| SuperFine | Longer trees | Higher than supermatrix | P < 0.01 for time difference |

| SuperTriplets | Longer trees | Roughly equivalent to supermatrix | Not significant for time difference |

The results demonstrated that supermatrix searches produced significantly shorter trees than either supertree approach, with strong statistical support (P < 0.0002) [12]. In terms of computational tractability, supermatrix processing time was significantly lower than SuperFine with locus-specific search but roughly equivalent to SuperTriplets with locus-specific search [12]. These findings challenge the assertion that supertree approaches offer superior computational tractability for large multilocus datasets.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Supermatrix Construction and Analysis Protocol

The supermatrix approach begins with identifying orthologous genes across the target prokaryotic taxa. The following protocol ensures methodological rigor:

Gene Family Identification: Use tools like PGAP2, which employs fine-grained feature analysis within constrained regions to rapidly and accurately identify orthologous and paralogous genes [13]. PGAP2 organizes data into gene identity networks (edges represent similarity between genes) and gene synteny networks (edges denote adjacent genes) [13].

Sequence Alignment: Align sequences for each orthologous gene family using robust alignment algorithms (e.g., MAFFT, Muscle). Manually inspect alignments for quality and remove ambiguous regions [14].

Concatenation: Concatenate aligned sequences into a supermatrix, ensuring proper positional homology across taxa. Use appropriate partitioning strategies to account for different evolutionary models for different genes.

Model Selection: Select best-fit evolutionary models for each partition using tools like ModelFinder or jModelTest [14].

Tree Inference: Perform heuristic tree search under maximum likelihood or Bayesian inference criteria using software such as RAxML, IQ-TREE, or MrBayes [14].

Support Assessment: Assess statistical support using bootstrap resampling (for maximum likelihood) or posterior probabilities (for Bayesian inference) [14].

Supertree Construction Protocol

Supertree methods employ a different workflow that emphasizes individual gene tree analysis prior to combination:

Locus-Specific Tree Inference: Infer separate phylogenetic trees for each gene or locus using appropriate evolutionary models. This step parallels single-gene phylogeny reconstruction.

Tree Combination: Apply supertree algorithms (e.g., Matrix Representation with Parsimony (MRP), SuperTriplets, or SuperFine) to combine individual gene trees into a comprehensive species tree [12].

Topology Refinement: Resolve conflicts between gene trees using various consensus or optimization criteria.

Support Evaluation: Assess support for bipartitions in the supertree through specific supertree support measures or by examining congruence among source trees.

The Ribosomal Tree Scaffold: A Reference-Based Framework

A hybrid approach that addresses the limitations of both single-gene phylogenies and purely algorithmic combinations is the Rooted Net of Life (RNoL) framework, which uses a ribosomal tree scaffold [11]. This method constructs a well-resolved and rooted tree scaffold inferred from a supermatrix of combined ribosomal RNA and protein sequences, then superimposes unrooted phylogenies of other gene families over this scaffold [11].

Ribosomal genes provide an ideal scaffold because they exhibit high sequence conservation with infrequent horizontal transfer between distantly related groups, offering a robust vertical evolutionary signal [11]. When conflicts between gene trees and the scaffold are sufficiently supported, reticulations are formed in the network, representing potential horizontal transfer events or other evolutionary processes causing discordance [11].

Table 2: Ribosomal Scaffold Approach for Reconstructing Prokaryotic Evolutionary History

| Component | Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal Supermatrix | Concatenated ribosomal RNA and protein sequences | Provides robust, conserved vertical signal with minimal HGT |

| Scaffold Tree | Well-resolved, rooted phylogeny from ribosomal data | Serves as reference framework for additional gene families |

| Gene Family Trees | Unrooted phylogenies for all other gene families | Captures individual gene histories |

| Reticulations | Network connections formed at incongruent nodes | Represents HGT, endosymbiosis, or other non-vertical events |

This approach acknowledges that organisms consist of discrete evolutionary units (open reading frames, operons, plasmids, chromosomes) with potentially different histories, while providing a structured framework for integrating these multiple histories into a coherent representation [11].

Research Reagent Solutions for Prokaryotic Phylogenomics

Table 3: Essential Bioinformatics Tools for Prokaryotic Phylogenetic Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PGAP2 | Pan-genome analysis pipeline identifying orthologs/paralogs via fine-grained feature networks | Handles thousands of prokaryotic genomes; quantitative cluster characterization [13] |

| RAxML/IQ-TREE | Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic inference | Supermatrix analysis; single-gene tree inference for supertrees [14] |

| MrBayes | Bayesian phylogenetic inference | Supermatrix analysis with complex evolutionary models [14] |

| FigTree | Phylogenetic tree visualization | Visualization and annotation of final trees; publication-ready figures [15] |

| MAFFT/Muscle | Multiple sequence alignment | Alignment of orthologous sequences for supermatrix construction [14] |

| Roary/Panaroo | Pan-genome analysis | Alternative pan-genome analysis for identifying core and accessory genes [13] |

The inadequacy of single-gene phylogenies necessitates sophisticated multilocus approaches for reconstructing prokaryotic evolutionary history. Empirical evidence from organismal datasets indicates that supermatrix methods generally produce superior trees (shorter under parsimony criterion) with comparable or better computational efficiency than supertree approaches [12]. However, the rooted network approach incorporating a ribosomal scaffold offers a promising framework for acknowledging the complex evolutionary histories of prokaryotic genomes while maintaining a structured analytical approach [11].

For researchers navigating these methodological choices, the decision between supermatrix and supertree approaches should be guided by dataset characteristics, research questions, and computational resources. Supermatrix methods appear preferable for achieving optimal tree quality with manageable computational requirements, while supertree approaches may offer advantages for certain dataset structures with extensive missing data. Future methodological developments will likely continue to bridge the gap between these approaches, providing more powerful tools for unraveling the complex evolutionary history of prokaryotes.

The Limitations of 16S rRNA and the Rise of Whole-Genome Methods

For decades, the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene has served as the cornerstone of microbial phylogeny and classification. Its utility stems from its universal presence in prokaryotes, functional constancy, and a structure featuring highly conserved regions interspersed with variable segments that serve as molecular clocks [1]. This gene single-handedly revealed the existence of the three domains of life—Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukaryota—and enabled the first large-scale surveys of uncultured microbial diversity [1]. However, technological advances have revealed fundamental limitations that constrain its resolution and accuracy. The 16S rRNA gene represents only about 0.05% of a typical prokaryotic genome, providing limited phylogenetic signal compared to approaches utilizing complete genomic information [1]. Furthermore, different variable regions of the 16S gene provide substantially different taxonomic resolution and exhibit distinct taxonomic biases [16]. For instance, the V4 region fails to confidently classify approximately 56% of sequences at the species level, while the V1-V3 region performs poorly for Proteobacteria [16]. Perhaps most critically, many bacterial genomes contain multiple polymorphic copies of the 16S gene that vary within a single genome, complicating strain-level discrimination [16].

Whole-genome approaches overcome these limitations by utilizing significantly more genetic information, providing greater resolution for both ancient and recent evolutionary relationships [1]. These methods can be broadly categorized into supermatrix approaches (which concatenate genes into a single alignment for tree inference) and supertree approaches (which combine independent gene trees into a consensus tree) [1]. The transition to whole-genome sequencing has been facilitated by dramatic improvements in sequencing technologies and computational power, enabling researchers to move beyond a single gene to comprehensive genome-level analysis [1] [17].

Core Whole-Genome Methodologies: Supermatrix vs. Supertree Approaches

The Supermatrix Approach

The supermatrix method involves concatenating multiple aligned gene sequences from a set of organisms into a single combined alignment matrix, from which a phylogenetic tree is then inferred [1]. This approach effectively increases the amount of data available for phylogenetic reconstruction, potentially improving statistical support for branching patterns. The supermatrix approach has been successfully used to infer phylogenies across the tree of life, with studies demonstrating high taxonomic congruence between supermatrix and supertree methods despite utilizing different sets of marker genes [1].

Key Advantages:

- Maximizes the use of sequence data in a single analysis

- Generally provides higher resolution for closely related taxa

- Allows application of complex evolutionary models to the entire dataset

Common Implementation Challenges:

- Requires complete or nearly complete data for all selected genes across all taxa

- Vulnerable to missing data, which can lead to systematic errors

- Computationally intensive for large datasets

The Supertree Approach

The supertree method involves constructing separate phylogenetic trees for individual genes or gene families and then combining these independent trees into a single consensus tree that represents the overall evolutionary relationships [1]. This approach provides a framework for integrating phylogenetic information from diverse sources, including datasets with different taxonomic samplings.

Key Advantages:

- Can incorporate data from partially overlapping gene sets

- Allows different evolutionary models for different genes

- More flexible for combining published phylogenetic trees

Common Implementation Challenges:

- Potential loss of information from individual gene sequences during the combination process

- Complex relationships between genes can be difficult to reconcile

- May produce less resolved trees compared to supermatrix approaches

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Supermatrix vs. Supertree Methods

| Feature | Supermatrix Approach | Supertree Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Data Structure | Concatenated gene alignments | Multiple individual gene trees |

| Data Requirements | Requires complete data for all genes | Can work with partially overlapping data |

| Computational Demand | High for alignment and tree building | Moderate for individual trees, high for combination |

| Handling Missing Data | Problematic, can introduce bias | More robust to missing data |

| Resolution | Generally higher resolution | May have lower resolution in consensus tree |

| Common Software | RAxML, IQ-TREE, MrBayes | ASTRAL, MRP, Clann |

Methodological Workflow Comparison

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural differences between supermatrix and supertree construction methods:

Performance Comparison: Whole-Genome vs. 16S rRNA Approaches

Taxonomic Resolution and Accuracy

Whole-genome approaches demonstrate superior performance across multiple metrics compared to single-gene methods. The following table summarizes key comparative findings from empirical studies:

Table 2: Resolution and Accuracy Comparison of Phylogenetic Methods

| Method | Species-Level Resolution | Strain-Level Resolution | Reference Standard | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-Length 16S rRNA | Moderate (varies by region) | Limited due to intragenomic variation | 16S rRNA database | Different variable regions have taxonomic biases [16] |

| 16S Sub-regions (V4) | Poor (∼44% accurate species assignment) | Not achievable | Greengenes database | Fails to discriminate closely related taxa [16] |

| Feature Frequency Profile (FFP) | High | Moderate | NCBI taxonomy | Requires optimal feature length selection [18] |

| 20 Validated Bacterial Core Genes (VBCG) | High (validated fidelity) | High | 16S rRNA tree congruence | Requires complete genomes [19] |

| 92 Universal Bacterial Core Genes (UBCG) | High | Moderate | Presence/single-copy ratio | Some genes may have discordant evolutionary signals [19] |

A critical evaluation of 16S rRNA sequencing demonstrated that targeting sub-regions represents a historical compromise due to technological limitations. The V4 region performs particularly poorly, with 56% of in-silico amplicons failing to confidently match their sequence of origin at the species level. By contrast, full-length 16S sequences could correctly classify nearly all sequences to their correct species [16]. Whole-proteome phylogeny using Feature Frequency Profiles (FFP) clearly separates the three domains of life (Archaea, Bacteria, Eukaryota) and positions Planctomycetes at the basal position of the Bacteria domain [18].

Phylogenomic Core Gene Sets

Various core gene sets have been developed for bacterial phylogenomic analysis, with differing performance characteristics:

Table 3: Comparison of Bacterial Core Gene Sets for Phylogenomic Analysis

| Gene Set | Number of Genes | Selection Criteria | Phylogenetic Fidelity Assessment | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBCG (Validated Bacterial Core Genes) | 20 | Presence ratio >95%, single-copy ratio >95%, high phylogenetic fidelity | Explicitly evaluated using Robinson Foulds distance against 16S trees | High-fidelity strain tracking and evolution studies [19] |

| UBCG2 (Universal Bacterial Core Genes) | 81 | Presence ratio >95%, single-copy ratio >95% | Not evaluated for individual gene fidelity | Broad taxonomic applications [19] |

| bcgTree | 107 | Single-copy in >95% of bacterial genomes | Not evaluated for individual gene fidelity | Automated phylogenomic pipeline [19] |

| AMPHORA | 31 | Functional conservation | Not evaluated for individual gene fidelity | Phylogenomic analysis of genomes and metagenomes [19] |

The 20-gene VBCG set represents a significant advancement as it incorporates phylogenetic fidelity as a selection criterion in addition to presence and single-copy ratios. This validation against 16S rRNA tree congruence ensures the selected genes provide congruent evolutionary signals, resulting in phylogenies with higher topological accuracy [19].

Experimental Protocols for Whole-Genome Phylogenetics

Feature Frequency Profile (FFP) Protocol

The FFP method represents an alignment-free approach to whole-proteome phylogeny construction [18]:

Proteome Preparation: Obtain whole proteome sequences (WPS) consisting of all predicted protein sequences from an organism's chromosome(s)

Feature Extraction:

- Represent each WPS as a profile of feature frequencies

- Features are l-mers (subsequences) of amino acids

- Critical step: identify optimal feature lengths for phylogeny inference

Distance Matrix Construction: Calculate distances between organisms based on their feature frequency profiles

Tree Building: Construct phylogenetic trees from the distance matrix using standard algorithms (BIONJ or neighbor-joining)

This method has been applied to 884 prokaryotes, 16 unicellular eukaryotes, and random sequence outgroups, successfully separating the three domains of life and providing well-supported branch arrangements [18].

Validated Bacterial Core Genes (VBCG) Pipeline

The VBCG pipeline provides a validated approach for high-fidelity phylogenomic analysis [19]:

Genome Selection and Preparation:

- Input complete bacterial genomes

- Extract protein sequences and 16S rRNA genes

Core Gene Annotation:

- Use HMMER hmmscan to identify and annotate core genes

- Apply trusted score cutoffs for gene assignment

Gene Selection and Validation:

- Calculate presence ratio and single-copy ratio for each candidate gene

- Select genes with both ratios >95%

- Evaluate phylogenetic fidelity using Robinson Foulds distance comparison with 16S rRNA trees

Phylogenomic Tree Construction:

- Align core gene sequences using MUSCLE

- Trim alignments to remove terminal gaps

- Select conserved blocks using Gblocks

- Concatenate alignments, removing taxa with >1 missing gene

- Reconstruct tree using maximum likelihood methods

This protocol has been validated on 30,522 complete genomes covering 11,262 species and demonstrates superior performance for strain-level tracking of bacterial pathogens [19].

Advanced Techniques: Strain-Level Resolution and Population Genetics

Leveraging Intragenomic Variation for Strain Discrimination

Many bacterial genomes contain multiple polymorphic copies of the 16S gene that vary within a single genome. Modern sequencing platforms (PacBio CCS and Oxford Nanopore) can resolve these subtle nucleotide substitutions, enabling strain-level discrimination [16]. The RoC-ITS method combines full-length 16S sequencing with the neighboring internally transcribed spacer (ITS) region, providing both species-level information (from 16S) and strain-level information (from the more variable ITS) [20]. This approach enables monitoring of subtle shifts in microbial community composition that would be missed by conventional 16S sequencing.

Phylogenetic and Population Genetic Analysis with RoC-ITS

The RoC-ITS protocol utilizes rolling-circle amplification and nanopore sequencing to generate high-fidelity circular consensus sequences [20]:

PCR Amplification: Amplify the 16S-ITS region using primers targeting conserved regions of the 16S and 23S genes

Molecular Barcoding: Add unique barcodes to both ends of the amplicon through sequential PCR steps

Circularization: Circularize linear products using splint oligonucleotides that match the unique primer sequences

Rolling Circle Amplification: Generate concatenated repeats of the circular template

Nanopore Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence long concateners and computationally derive circular consensus sequences

This method provides unprecedented resolution for tracking microbial population dynamics and has been validated on artificial communities with comparison to Illumina sequencing results [20].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Whole-Genome Phylogenetics

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore Q20+ | Full-length 16S and whole-genome sequencing | Long reads (>15 kb), high accuracy (≥99%) [21] [16] |

| Primer Systems | 27F-II degenerate primer set | Full-length 16S rRNA gene amplification | Improved coverage of diverse bacterial communities [21] |

| Reference Databases | Greengenes, RDP, NCBI Genome | Taxonomic classification and reference | Curated collections of 16S and whole-genome sequences [16] [19] |

| Alignment Tools | MUSCLE, MAFFT | Multiple sequence alignment | Essential for supermatrix construction [19] |

| Tree Building Software | FastTree, RAxML, ASTRAL | Phylogenetic inference | Implements maximum likelihood and supertree methods [19] |

| Core Gene Sets | VBCG, UBCG2, bcgTree 107 genes | Phylogenomic analysis | Validated marker genes for different applications [19] |

| Computational Pipelines | VBCG Python pipeline, bcgTree | Automated phylogenomic analysis | Streamlined workflow from genomes to trees [19] |

Whole-genome approaches have fundamentally transformed prokaryotic phylogenetics by providing unprecedented resolution and evolutionary context. The supermatrix and supertree methods offer complementary strengths—the former providing maximum sequence utilization and resolution, while the latter offers flexibility in combining diverse datasets. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and computational methods become more sophisticated, the integration of these approaches will further refine our understanding of microbial evolution and diversity. The development of validated core gene sets like VBCG represents a significant step toward standardized, high-fidelity phylogenomic analysis that can be widely adopted across research communities studying bacterial evolution, ecology, and pathogenesis.

A Practical Guide to Supertree and Supermatrix Methodologies

The supermatrix approach to phylogenomics involves concatenating multiple sequence alignments from numerous genes into a single data matrix, which is then used to infer a species tree [22]. This method often provides greater phylogenetic accuracy by leveraging a larger number of sites compared to single-gene analyses [22]. The process can be broken down into several key stages, from data preparation to final tree inference, and can be automated by various software tools.

The diagram below illustrates the logical sequence of this workflow, highlighting the two primary analysis paths (gene trees and the supermatrix) that lead to the final species tree.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Data Preparation and Orthologous Group Selection

The initial phase requires gathering sequences into Orthologous Groups (OGs), where each species is ideally represented by a single sequence per OG [23]. This is typically defined in a tab-delimited text file. The set of target species is automatically determined from the sequences, but can be manually curated [23]. A critical step is OG selection, which filters OGs based on species coverage (e.g., cog_100 uses only OGs containing sequences from all species, while cog_90 uses OGs with at least 90% species coverage) [23]. This ensures the concatenated matrix is derived from genes with sufficient phylogenetic information.

Sequence Alignment and Trimming

Sequences within each OG must be aligned. Any standard multiple sequence alignment tool can be used via a selected gene-tree workflow [23]. For example, a workflow like clustalo_default-trimal01-none-none specifies alignment with Clustal Omega, followed by trimming with trimAl [23]. If the gene-tree workflow includes a trimming step, the trimmed alignment is used for concatenation, which helps remove poorly aligned regions and improves phylogenetic signal [23].

Alignment Concatenation and Partitioning

Aligned OGs are concatenated into a single supermatrix. Tools like PhyKIT can automate this process [24]. The command pk_create_concat -a alignments.txt -p concat generates three key files [24]:

concat.fa: The concatenated supermatrix in FASTA format.concat.partition: A RAxML-style partition file defining the position and length of each gene within the supermatrix.concat.charset: A file describing the character sets.

The partition file is crucial for allowing different models of sequence evolution to be applied to different gene regions in subsequent steps [24].

Model Testing and Partition Scheme Optimization

Determining the best-fit model of sequence evolution is vital for accurate tree inference. IQ-TREE2 is widely used for this purpose [24]. Two key strategies are:

TESTMERGEONLY: Tests and potentially merges partitions that share a similar best-fit model, simplifying the partition scheme. The best-fit model is selected using criteria like BIC, AIC, or AICc [24].MF+MERGE: Uses the ModelFinderPlus scheme to find the best partition model, which can be more computationally intensive but may identify more complex models like free-rate models (LG+R3) [24].

For a simpler approach, testing a single model for the entire supermatrix with -m TESTONLY is also possible [24].

Species Tree Inference

The final step is inferring the species tree from the concatenated supermatrix. This is typically done with maximum likelihood programs like IQ-TREE2 or FastTree [23] [24]. The command specifies the supermatrix, the partition file, and the selected model. For example, using a pre-determined model looks like iqtree2 -s concat.fa -spp concat.partition.nex -m LG+I+G4 -pre concat_final_tree [24].

Comparative Analysis of Supermatrix Tools

Various software tools automate the supermatrix construction pipeline, each with different capabilities regarding alignment and handling of missing data.

Table 1: Comparison of phylogenomic tools supporting supermatrix construction

| Tool | Primary Approach | Last Update | Automates Alignment? | Handles Missing Data? | Key Features and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPLACE [22] | Supermatrix | Aug 2022 | Yes | Yes | Fully automated split-align-concatenate pipeline; uses Docker for dependency management; open-source. |

| ROADIES [25] | Discordance-aware (Reference-free) | 2025 | N/A | Yes | Does not rely on pre-defined genes; randomly samples genomic loci; uses ASTRAL-Pro3 on multicopy genes; annotation-free and orthology-free. |

| ETE3 Build [23] | Supermatrix & Gene Trees | Active | Yes | Via OG selection | Highly configurable workflow system; allows detailed control over OG selection and alignment/trimming steps. |

| TREEasy [22] | Supermatrix & Supertree | Jul 2020 | Yes | No | Provides both supermatrix and supertree outputs; requires installation of numerous dependencies. |

| SequenceMatrix [22] | Supermatrix | May 2021 | No | No | GUI-based concatenation of pre-aligned files; susceptible to manual error during file preparation. |

| Phyutility [22] | Supermatrix | Sep 2012 | No | Yes | Manages trees, sequences, and alignments; can trim regions with high missing data. |

| TaxMan [22] | Supermatrix | Sep 2006 | Yes | No | Deprecated; automated sequence acquisition and alignment required multiple prerequisites. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key software and data components for supermatrix analysis

| Item Name | Category | Function / Purpose | Example Tools / Formats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthologous Groups (OGs) | Input Data | Defines sets of genes shared across species descended from a common ancestral gene; the fundamental unit for concatenation. | COGs (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) [23] |

| Multiple Sequence Aligner | Software | Aligns nucleotide or amino acid sequences within each OG to identify homologous positions. | Clustal Omega, MAFFT [23] |

| Alignment Trimmer | Software | Removes poorly aligned or gappy regions from multiple sequence alignments to improve phylogenetic signal. | trimAl [23] |

| Sequence Concatenator | Software | Merges individual gene alignments into a single supermatrix file. | PhyKIT, SPLACE, ETE3 Build [23] [24] [22] |

| Partition File | Data File | Defines the boundaries and locations of each gene within the concatenated supermatrix. | RAxML format, NEXUS format [24] |

| Model Testing Software | Software | Identifies the best-fit model of sequence evolution for the entire supermatrix or for specific partitions. | IQ-TREE2 (ModelFinder) [24] |

| Maximum Likelihood Phylogenetic Inferencer | Software | Infers the final species tree from the concatenated supermatrix under the selected model of evolution. | IQ-TREE2, RAxML, FastTree [23] [24] |

Matrix Representation with Parsimony (MRP) is a foundational supertree technique designed to reconstruct a comprehensive phylogeny from multiple smaller, overlapping source trees. Developed independently by Baum (1992) and Ragan (1992), MRP has become one of the most widely used supertree methods in systematics [26] [27]. In the context of prokaryotic phylogeny research, where achieving complete taxonomic sampling across all genetic markers remains challenging, MRP offers a pragmatic solution for integrating phylogenetic information from diverse gene trees into a unified species tree. The method operates by encoding the topological information from source trees into a binary matrix representation, which is subsequently analyzed using parsimony algorithms to generate a supertree containing the complete set of taxa [28]. This approach stands in contrast to supermatrix (or total evidence) methods, which concatenate sequence alignments prior to phylogenetic analysis. The ongoing methodological debate between these two paradigms centers on their relative abilities to accurately reconstruct evolutionary relationships, particularly when dealing with complex evolutionary processes like horizontal gene transfer that frequently complicate prokaryotic phylogenetics [28] [29].

Methodological Framework: How MRP Works

Core Algorithm and Computational Process

The MRP algorithm transforms a collection of input trees with partially overlapping taxon sets into a single comprehensive supertree through a multi-step process. First, each internal branch within every source tree is encoded as a partial binary character in a matrix. For a given split in a source tree, taxa in one partition are assigned '1', those in the other partition receive '0', and taxa missing from that source tree are coded as '?' to indicate missing data [27]. This matrix representation effectively captures the hierarchical information contained across all source trees.

The resulting matrix is then analyzed using maximum parsimony criteria to find the tree (or trees) that requires the fewest evolutionary steps to explain the distribution of these binary characters. This optimization problem is typically solved using heuristic search algorithms due to the computational complexity of finding the most parsimonious tree for large datasets [27]. The computational implementation of MRP is available in various software packages, including the mrp.supertree function in the R package phytools, which offers options for optimization using either pratchet or optim.parsimony algorithms [27].

Variants and Extensions

Several methodological variants of MRP have been developed to enhance its performance:

Weighted MRP: This extension incorporates branch support values from source trees by weighting the matrix elements according to bootstrap frequencies or posterior probabilities [30]. This approach gives greater influence to more robustly supported nodes during the parsimony analysis.

Matrix Representation with Compatibility (MRC): An alternative approach that seeks to maximize the number of compatible source tree splits in the supertree, though it is less frequently implemented than MRP [31].

The following diagram illustrates the complete MRP workflow from source trees to supertree estimation:

Performance Comparison: MRP Versus Alternative Approaches

Comparative Accuracy Under Simulation Studies

Multiple simulation studies have evaluated the topological accuracy of MRP against supermatrix methods and other supertree approaches. The evidence consistently demonstrates that while MRP provides a reasonable approximation of the true phylogeny, it generally underperforms compared to supermatrix (total evidence) approaches, especially when maximum likelihood is used for the combined analysis [30].

A key simulation study using the SMIDGen methodology, which incorporates more biologically realistic conditions including gene birth-death processes and varied taxonomic sampling strategies, found that "combined analysis based upon maximum likelihood outperforms MRP and weighted MRP, giving especially big improvements when the largest subtree does not contain most of the taxa" [30]. This pattern held across datasets ranging from 100 to 1000 taxa, indicating the robustness of the results across different tree sizes.

Table 1: Comparative Accuracy of MRP Against Alternative Methods Under Simulation Conditions

| Method | Taxa Number | Data Partitions | Accuracy Rate (Homogeneous) | Accuracy Rate (Heterogeneous) | Key Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Evidence (ML) | 10 | 10 | 78.7% | 76.8% | [26] |

| Average Consensus | 10 | 10 | 76.1% | 75.1% | [26] |

| MRP | 10 | 10 | 66.8% | 65.5% | [26] |

| Total Evidence (ML) | 30 | 10 | 33.3% | 31.7% | [26] |

| Average Consensus | 30 | 10 | 26.5% | 26.1% | [26] |

| MRP | 30 | 10 | 11.8% | 12.5% | [26] |

| Combined Analysis (ML) | 100-1000 | Mixed | Significantly higher than MRP | - | [30] |

| Weighted MRP | 100-1000 | Mixed | Intermediate between MRP and Combined | - | [30] |

Impact of Data Characteristics on Performance

The performance of MRP relative to alternative methods is influenced by several data characteristics:

Taxonomic Overlap: MRP performance degrades significantly when source trees have limited taxonomic overlap. One study found that "when source studies were even moderately nonoverlapping (i.e., sharing only three-quarters of the taxa), the high proportion of missing data caused a loss in resolution that severely degraded the performance for all methods" [32].

Number of Partitions: All methods, including MRP, show improved accuracy with increasing numbers of data partitions, though the performance gap between MRP and total evidence persists [26].

Data Heterogeneity: MRP is particularly sensitive to heterogeneous data, with performance dropping more significantly compared to total evidence methods when source trees conflict due to different evolutionary histories [26].

Taxon Sampling Strategy: MRP performs better when source trees include a scaffold tree with broad taxonomic sampling alongside clade-focused trees with dense sampling [33].

Experimental Protocols and Assessment Methodologies

Standard Simulation Framework

Simulation studies comparing phylogenetic methods typically follow a standardized protocol to ensure reproducible and biologically meaningful results:

Model Tree Generation: Trees are generated under a pure birth (Yule) process, with branch lengths modified to deviate from ultrametricity, reflecting realistic evolutionary scenarios [30].

Sequence Evolution: DNA sequences are evolved along model trees using programs like Seq-Gen under substitution models such as GTR+Γ, with site-specific rate variation [26].

Data Partitioning: Sequences are partitioned to mimic biological realities, with different genes potentially having distinct evolutionary histories or rates [26].

Tree Estimation: Source trees are estimated from individual partitions using methods like maximum likelihood or parsimony, followed by supertree construction using MRP and its variants [26].

Accuracy Assessment: Reconstructed trees are compared to the known model tree using topological distance measures, such as the Robinson-Foulds distance, to quantify accuracy [26].

Novel Simulation Approaches

Recent advances in simulation methodology have introduced more biologically realistic elements:

SMIDGen (Super-Method Input Data Generator): This approach incorporates gene birth-death processes to determine presence/absence patterns and uses clade-based taxon sampling strategies that reflect systematists' practices [30].

Heterogeneous Data Simulation: Some studies explicitly model heterogeneous data by evolving sequences on trees with identical topologies but different branch lengths [26].

Emerging Alternatives and Methodological Innovations

Quartet-Based Methods

Quartet-based supertree methods have emerged as promising alternatives to MRP. These methods operate by decomposing source trees into their constituent quartet trees (four-taxon subtrees) and then assembling these quartets into a comprehensive supertree. The Quartets MaxCut (QMC) method has shown particular promise, with simulation studies indicating that it "usually outperform[s] MRP and five other supertree methods... under many realistic model conditions" [33]. However, QMC methods face scalability challenges with large datasets, potentially limiting their utility in prokaryotic phylogenomics with extensive taxonomic sampling.

Majority-Rule Supertrees

Majority-rule supertree methods generalize the familiar majority-rule consensus to the supertree setting. These methods aim to find trees that contain splits present in a majority of the source trees, minimizing the Robinson-Foulds distance to the input trees. Variants include:

- MR(-) supertrees: Compare the pruned supertree to each input tree [31]

- MR(+) supertrees: Extend input trees to include missing taxa before comparison [31]

Studies have shown that MR(-) supertrees "performed well" when combining incompatible input trees, suggesting potential advantages over MRP in certain challenging phylogenetic contexts [31].

Integrated Approaches

Novel approaches that combine strengths from different methodologies are emerging. The SuperTRI method incorporates branch support analyses from independent datasets and assesses node reliability using multiple measures: "supertree Bootstrap percentage... the mean branch support... and the reproducibility index" [3]. This approach demonstrates "less sensitivity to different phylogenetic methods" and provides "more accurate interpretation of the relationships among taxa" compared to standard supermatrix approaches [3].

Table 2: Key Supertree Methods and Their Characteristics

| Method | Core Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRP | Matrix representation with parsimony | Widely implemented; handles incompatible trees | Lower accuracy than supermatrix; potential bias | [26] [30] |

| Weighted MRP | MRP with branch support weighting | Incorporates node confidence measures | Still underperforms vs. likelihood supermatrix | [30] [32] |

| QMC | Quartet amalgamation | High accuracy under many conditions | Scalability issues with large taxon sets | [33] |

| Majority-Rule | Generalization of majority-rule consensus | Theoretically appealing properties | Multiple variants with different behaviors | [31] |

| SuperTRI | Branch support integration | Robust across analysis methods; assesses reliability | Complex implementation | [3] |

Successful implementation of MRP and related supertree methods requires familiarity with both conceptual frameworks and practical computational tools. The following table outlines key resources mentioned in methodological studies:

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Supertree Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Key Features | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAUP* | Phylogenetic analysis | Source tree estimation; parsimony analysis | Industry standard; multiple algorithms | Commercial software |

| RAxML | Maximum likelihood analysis | Source tree estimation; combined analysis | Efficient likelihood implementation; handles large datasets | [30] |

| PHYLIP | Phylogenetic package | Distance-based tree estimation | Comprehensive suite; includes FITCH algorithm | [26] |

| phytools | R package | MRP supertree estimation | mrp.supertree function; multiple optimization options |

[27] |

| Seq-Gen | Sequence simulation | Data simulation under evolutionary models | Implements various substitution models | [26] |

| PluMiST | Python program | Majority-rule supertree computation | Implements MR(-) and related methods | [31] |

The extensive comparative studies on MRP and alternative phylogenetic methods yield several strategic insights for prokaryotic phylogeny research. First, when sequence data are available and computationally manageable, supermatrix approaches using maximum likelihood generally provide superior topological accuracy compared to MRP supertrees [30]. This advantage appears particularly pronounced in prokaryotic systems where heterogeneous evolutionary processes like horizontal gene transfer can create substantial conflict between gene trees.

However, MRP and its weighted variant remain valuable approaches in several scenarios: when analyzing very large taxon sets that exceed computational limits of supermatrix methods; when combining trees derived from different data types (e.g., morphological and molecular); or when working with published phylogenies where original sequence data may be unavailable [30]. Weighted MRP, which incorporates branch support values, consistently outperforms unweighted MRP and in some studies has been shown to "usually out-perform total evidence slightly" under specific conditions [32].

For researchers pursuing MRP supertree construction, methodological best practices include: (1) utilizing weighted MRP whenever possible to incorporate branch support information; (2) ensuring adequate taxonomic overlap between source trees, potentially through strategic inclusion of scaffold trees with broad sampling; and (3) applying multiple supertree methods as a robustness check when analytical circumstances permit [30] [32]. As supertree methodology continues to evolve, methods like QMC and SuperTRI show promise for addressing specific limitations of MRP, particularly in handling topological conflict and providing more nuanced assessments of node reliability [33] [3].

The ongoing methodological development in this field suggests that while MRP established a foundational framework for supertree construction, next-generation methods incorporating more sophisticated statistical frameworks and efficient algorithms will likely shape the future of comprehensive phylogenetic synthesis in prokaryotic systems and beyond.

Reconstructing the evolutionary history of prokaryotes is fundamental to microbiology, with applications ranging from tracing the emergence of pathogenic strains to understanding the diversification of early life. However, this task is profoundly complicated by Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT), a process where genes are transferred between organisms outside of vertical descent. HGT is not a mere nuisance; it is a major evolutionary force that can obscure the vertical phylogenetic signal, leading some to question whether a single, tree-like representation of prokaryotic evolution is even possible [34]. Within this challenging context, two primary computational strategies have been developed for building phylogenies from genome-scale data: the supermatrix and supertree approaches. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, focusing on their application in prokaryotic phylogeny and their capacity to handle the pervasive influence of HGT, with a specific case study on core gene set-based phylogeny (CGCPhy).

The fundamental difference between these approaches lies in how they combine data from multiple genes.

The Supermatrix (Concatenation) Approach: This method involves concatenating multiple sequence alignments from numerous genes into a single, large alignment [35]. This supermatrix is then used to infer a phylogenetic tree in a simultaneous analysis. Its main strength is that it combines phylogenetic signals directly from every character site across all genes, which can help overcome stochastic error and reveal emergent support for relationships that are weakly supported in individual gene analyses [35] [36]. A significant practical advantage is the relative simplicity of estimating branch lengths and assessing confidence using standard bootstrapping techniques.

The Supertree Approach: This method first infers individual phylogenetic trees for each gene or dataset separately. These source trees are then combined using a specific algorithm to create a summary "supertree" [37] [3]. A key advantage is its ability to incorporate data from genes that are not present in all taxa, thus potentially utilizing a broader range of genomic data. However, a major limitation is that most supertree methods lose information from the primary sequence data during the synthesis process and can be sensitive to the way conflicts between source trees are resolved [3].

The Critical Workflow: From Genomes to Phylogeny

The process of building a genome-scale phylogeny, whether supermatrix or supertree, involves several key steps. The workflow below illustrates the shared and divergent paths these methods take, from raw genomic data to a final reconstructed phylogeny.

Case Study: Core Gene Sets for Phylogeny (CGCPhy) in Practice

The use of Core Gene Sets for Phylogeny (CGCPhy) is a widely adopted strategy to mitigate the challenges of HGT. The underlying principle is that a carefully selected set of universal, single-copy genes is less likely to have been horizontally transferred and thus retains a stronger vertical signal [37] [38]. Several standardized core gene sets have been developed, and pipelines like EasyCGTree have been created to automate the process of identifying these genes, building alignments, and inferring both supermatrix and supertree phylogenies [2].

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking CGCPhy Pipelines

To objectively compare the performance of phylogenetic methods, a typical experiment involves benchmarking different pipelines or data sets on a common set of genomes. The following protocol outlines the key steps, using a published analysis of the EasyCGTree pipeline as an example [2].

- Genome Selection and Input: A defined set of prokaryotic genomes is selected. For instance, a study might use 43 genomes from the genus Paracoccus to compare methods at the genus level. The input data is the proteome (all amino acid sequences) of each genome in FASTA format.

- Core Gene Identification with Profile HMMs: A profile Hidden Markov Model (HMM) database is used to search each proteome for homologs of core genes. Standardized gene sets like bac120 (120 bacterial genes), UBCG (92 bacterial core genes), or essential (107 essential genes) are typically employed [2]. Homologs are identified using

hmmsearch(from the HMMER package) with a strict E-value cutoff (e.g., 1e-10). - Sequence Alignment and Trimming: For each core gene, homologous sequences are aligned using tools like Clustal Omega or MUSCLE. The resulting multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) are then trimmed with a tool like trimAl (using methods such as "gappyout" or "strict") to remove poorly aligned regions and select conserved blocks [2].

- Phylogenetic Inference (Supermatrix vs. Supertree):

- Supermatrix: The trimmed alignments for all core genes are concatenated into a single supermatrix. A Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree is then inferred from this matrix using programs like IQ-TREE or FastTree [2] [38].

- Supertree: An ML tree is inferred from each individual trimmed gene alignment. These gene trees are then synthesized into a single supertree using a method like BUCKy (for Bayesian Concordance Analysis) or ASTRAL [2] [38].

- Performance Evaluation: The resulting phylogenies are compared using topological metrics. Common measures include:

- Robinson-Foulds (RF) distance: Measures the topological distance between two trees. A lower RF distance indicates more similar topologies.

- Cophenetic Correlation Coefficient (CCC): Assesses how well branch lengths in the tree represent the original evolutionary distances in the data. A value closer to 1.0 indicates higher accuracy [2].

Quantitative Comparison of Method Performance

The table below summarizes experimental data from benchmark studies that have compared supermatrix and supertree approaches in prokaryotic phylogenomics.

Table 1: Performance comparison of supermatrix and supertree methods based on experimental benchmarks

| Study & Data Set | Comparison Metric | Supermatrix Performance | Supertree Performance | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EasyCGTree Pipeline [2](43 Paracoccus genomes) | Topological Distance (RF) | Nearly identical (distance < 0.1) to reference trees from UBCG/bcgTree | Not specified for supertree | Supermatrix approach produced highly consistent and accurate topologies |

| Tree Accuracy (CCC) | High accuracy (CCC > 0.99) | Not specified for supertree | Concatenation reliably reproduced expected evolutionary relationships | |