Striking the Balance: Optimizing Sensitivity and Specificity in Modern Regulon Prediction Algorithms

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on the critical challenge of balancing sensitivity and specificity in regulon prediction.

Striking the Balance: Optimizing Sensitivity and Specificity in Modern Regulon Prediction Algorithms

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on the critical challenge of balancing sensitivity and specificity in regulon prediction. We explore the foundational definitions of these metrics and their profound impact on the reliability of predicted gene regulatory networks. The content covers current methodologies, from comparative genomics to machine learning, and details practical strategies for algorithm optimization and threshold tuning. Through a comparative analysis of validation frameworks and performance benchmarks, we equip scientists with the knowledge to select, refine, and validate regulon prediction tools effectively, thereby enhancing the accuracy of downstream functional analyses and experimental designs in genomics and drug development.

The Core Concepts: Understanding Sensitivity, Specificity, and the Regulon Prediction Challenge

FAQs on Sensitivity and Specificity for Computational Research

1. What do Sensitivity and Specificity mean in the context of regulon prediction?

In regulon prediction, a "test" is the computational algorithm you use to identify genes that belong to a particular regulon.

- Sensitivity (True Positive Rate) is the ability of your algorithm to correctly identify the genes that are true members of the regulon. A high sensitivity means your model misses very few true members (it has a low false negative rate). This is crucial for ensuring the regulon you predict is complete [1].

- Specificity (True Negative Rate) is the ability of your algorithm to correctly exclude genes that are not members of the regulon. A high specificity means your model rarely incorrectly includes genes that do not belong (it has a low false positive rate). This is vital for ensuring the regulon you predict is not contaminated with spurious members [1] [2].

2. Why is there always a trade-off between Sensitivity and Specificity?

Sensitivity and specificity are often inversely related [3] [4]. This trade-off arises from the statistical decision threshold you set in your algorithm.

- If you lower the threshold for what constitutes a regulon member, you will catch more true positives (increasing sensitivity), but you also increase the risk of accepting false positives (decreasing specificity) [4].

- If you raise the threshold, you become more stringent, which reduces false positives (increasing specificity) but increases the risk of missing true members (decreasing sensitivity) [4].

The goal is to find a balance appropriate for your research. For instance, in an initial discovery phase, you might prioritize sensitivity to generate a comprehensive candidate list. For validation, you might prioritize specificity to obtain a high-confidence set of genes.

3. My regulon prediction has high sensitivity but very low specificity. What could be the cause?

This is a common problem in computational predictions, where algorithms generate numerous false positives [2]. Potential causes include:

- Overly Permissive Model Parameters: The thresholds or scoring systems used in your pattern discovery (e.g., for identifying transcription factor binding sites) may be too lenient [2].

- Reliance on a Single Data Source: Using only one type of evidence (e.g., only sequence motif analysis) can be misleading. Integrating multiple data sources is often necessary for accurate predictions [5].

- Lack of Evolutionary Conservation: Many true regulatory relationships are conserved across related organisms. Predictions based solely on one genome without considering conservation in others can lack specificity [2].

4. What strategies can I use to improve the Specificity of my predictions without sacrificing too much Sensitivity?

- Integrate Comparative Genomics: Tools like Regulogger use conservation of regulatory sequences across multiple genomes to eliminate spurious predictions. This can dramatically increase specificity with minimal impact on sensitivity [2].

- Combine Data Types: Integrate your sequence-based predictions with experimental data such as ChIP-seq (for binding) and time-course gene expression data (for co-regulation). Tools like Genexpi are designed for this kind of integration, improving overall accuracy [5].

- Apply Regularization: During model fitting, use regularization techniques to penalize overly complex models that may be fitting to noise in the data, thus reducing false positives [5].

- Utilize Advanced Machine Learning: Modern deep-learning models (e.g., CNNs, Enformer) trained on large genomic datasets can learn complex sequence determinants of regulation, leading to higher specificity than older methods like k-mer SVM [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Balancing Sensitivity and Specificity

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High number of false positive predictions (Low Specificity) | Overly permissive motif or pattern-matching threshold. | Adjust the prediction score threshold to be more stringent [4]. Implement a comparative genomics tool like Regulogger to filter non-conserved predictions [2]. |

| Model overfitting to training data noise. | Introduce regularization terms during model parameter fitting to discourage complexity [5]. | |

| High number of false negative predictions (Low Sensitivity) | Overly strict model parameters or thresholds. | Slightly lower the decision threshold for what is considered a positive prediction [4]. |

| Incomplete input data (e.g., missing co-regulated genes). | Expand the initial set of candidate genes using diverse sources, such as literature mining or multiple expression datasets [5]. | |

| Unacceptable performance on both metrics | The underlying model or algorithm is not suitable for the data. | Re-evaluate the choice of algorithm. Consider switching to a more advanced method (e.g., from k-mer SVM to a CNN-based model) [6]. Ensure input data (e.g., time-series expression) is properly smoothed to reduce noise before analysis [5]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Regulon Predictions Using an Integrated Approach

This protocol outlines a method to predict and validate a regulon by combining sequence analysis with gene expression data, directly addressing the sensitivity-specificity trade-off.

1. Objective: To identify the high-confidence regulon of a specific transcription factor in a bacterial species.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Genomic Sequences: Genome sequences of the target organism and several closely related species.

- Gene Expression Data: Time-course RNA-seq or microarray data under conditions where the transcription factor is active.

- Candidate Gene List: A set of genes suspected to be under the transcription factor's control, derived from ChIP-seq experiments or literature curation [5].

- Software Tools: Genexpi (as a Cytoscape plugin, command-line tool, or R package) [5], Regulogger or a similar comparative genomics tool [2].

3. Methodology:

Step 1: Data Preparation and Smoothing

- Extract the regulatory region (e.g., promoter upstream sequences) for all genes in your target genome.

- Smooth the time-course expression data to reduce high-frequency noise. Linear regression of B-spline basis with degrees of freedom equal to roughly half the number of measurement points has been shown to be effective for this [5].

Step 2: Initial Regulon Inference with Genexpi

- Input the smoothed expression profiles and the candidate regulator (your transcription factor) expression profile into Genexpi.

- Genexpi uses an ordinary differential equation (ODE) model to fit the regulatory relationship. The model parameters are estimated by minimizing the squared error between predicted and observed expression, plus a regularization term to prevent overfitting [5].

- Output: An initial list of predicted regulon members with a statistical score.

Step 3: Enhance Specificity with Comparative Genomics (Regulogger)

- Take the initial list of predicted regulon members from Genexpi.

- Using Regulogger, identify orthologous genes in related species and check for conservation of the predicted regulatory sequence motif.

- Regulogger calculates a Relative Conservation Score (RCS) for each gene. Genes with a low RCS (non-conserved regulation) are considered false positives and filtered out [2].

- Output: A high-confidence "regulog" – a set of genes with conserved sequence and regulatory signals.

Step 4: Model Evaluation and Threshold Selection

- The final output is a list of genes and their associated scores. You can adjust the final score threshold to dial in the desired balance between sensitivity and specificity for your downstream application [7].

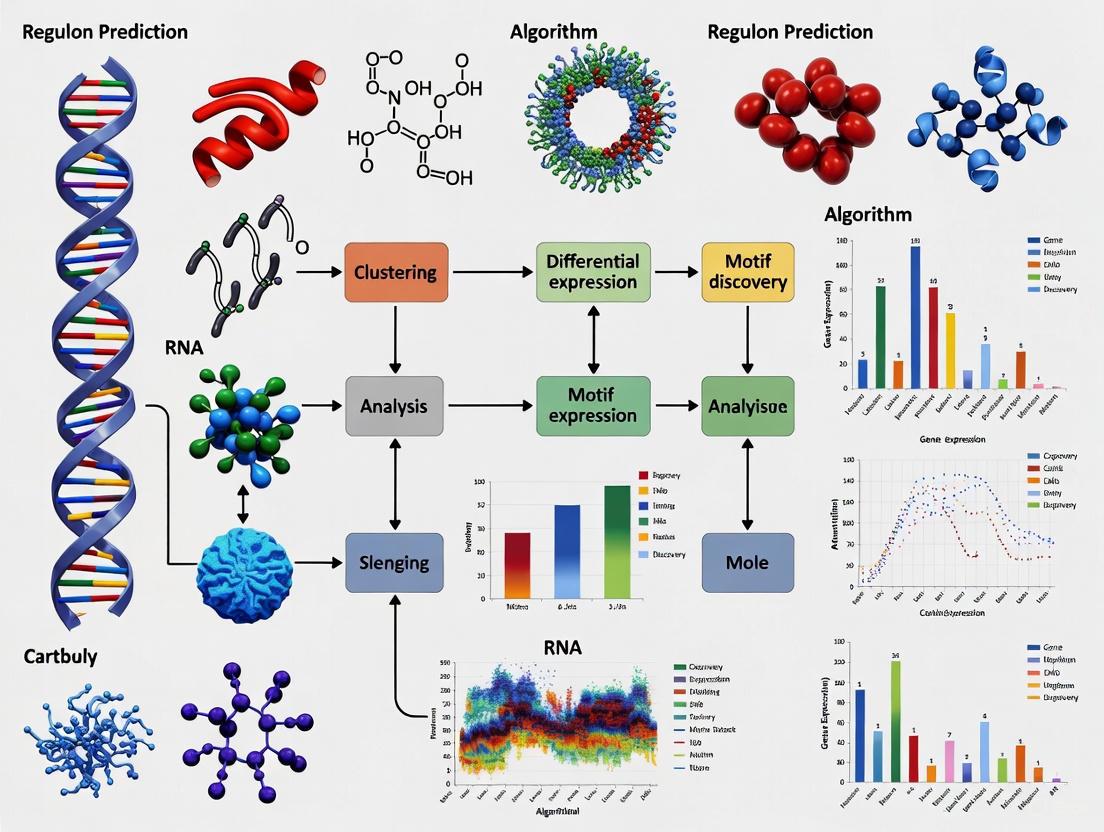

The workflow below visualizes this integrated experimental protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions for Regulon Analysis

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Genexpi Toolset | A core software tool that uses an ODE model to infer regulatory interactions from time-series expression data and candidate gene lists. It is available as a Cytoscape plugin (CyGenexpi), a command-line tool, and an R package [5]. |

| Regulogger Algorithm | A computational method that uses comparative genomics to eliminate false-positive regulon predictions by requiring conservation of the regulatory signal across multiple species [2]. |

| Cytoscape with CyDataseries | A visualization platform for biological networks. The CyGenexpi plugin operates within it, and the CyDataseries plugin is essential for handling time-series data within the Cytoscape environment [5]. |

| ChIP-seq Data | Experimental data identifying in vivo binding sites of a transcription factor, used to generate a high-quality list of candidate regulon members for input into tools like Genexpi [5]. |

| Time-Course Expression Data | RNA-seq or microarray data measuring gene expression across multiple time points under a specific condition. This is the primary dynamic data used by Genexpi to fit its model of regulation [5]. |

| Ortholog Databases | Curated sets of orthologous genes across multiple genomes, which are a prerequisite for running comparative genomics analyses with tools like Regulogger [2]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts of Sensitivity and Specificity

What are sensitivity and specificity, and why are they crucial for regulon prediction algorithms?

Sensitivity and specificity are two fundamental statistical measures that evaluate the performance of a binary classification system, such as a diagnostic test or, in your context, a computational algorithm for predicting regulons [1].

- Sensitivity (True Positive Rate): This is the proportion of true positives that are correctly identified by your algorithm. In regulon prediction, it measures how well your method can correctly identify all the true target genes of a transcription factor. A highly sensitive algorithm minimizes false negatives, meaning it misses very few genuine regulatory relationships [4] [3]. The formula is: Sensitivity = True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives) [8]

- Specificity (True Negative Rate): This is the proportion of true negatives that are correctly identified. It measures your algorithm's ability to correctly reject genes that are not true targets of the transcription factor. A highly specific algorithm minimizes false positives, reducing the number of spurious predictions you need to validate experimentally [4] [3]. The formula is: Specificity = True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives) [8]

For regulon prediction, this means a sensitive algorithm is good for discovering a comprehensive set of potential targets (avoiding missed discoveries), while a specific algorithm is good for producing a highly reliable, precise list (avoiding costly follow-ups on false leads).

What is the fundamental reason for the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity?

The trade-off arises because most prediction algorithms are based on a quantitative biomarker or a scoring function—such as a binding affinity score, correlation coefficient, or p-value—rather than a perfect binary signal [9]. To classify results as positive or negative, you must set a threshold on this continuous value.

- Lowering the threshold makes the test less strict. It classifies more cases as positive, which captures more true positives (increasing sensitivity) but also inevitably captures more false positives (decreasing specificity).

- Raising the threshold makes the test more strict. It classifies fewer cases as positive, which correctly excludes more false positives (increasing specificity) but also misses more true positives (decreasing sensitivity).

This inverse relationship is intrinsic to the process of setting any classification boundary on a continuous scale. You cannot simultaneously expand the set of predicted positives to catch all true targets and contract it to exclude all non-targets [4] [1] [9].

How does this trade-off manifest in real-world genomic research?

A clear example comes from a study on Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) density for detecting prostate cancer, which is analogous to using a score to predict a biological state [4]. The study showed how different thresholds lead to dramatically different performance:

Table 1: Impact of Threshold Selection on Test Performance

| PSA Density Threshold (ng/mL/cc) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Clinical Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 0.05 | 99.6% | 3% | Misses very few cancers, but many false biopsies |

| ≥ 0.08 (Intermediate) | 98% | 16% | A balance between missing cancers and false alarms |

| ≥ 0.15 | Lower | Higher | Fewer unnecessary biopsies, but more cancers missed |

In regulon prediction, this translates directly: a lower statistical threshold for linking a gene to a transcription factor will yield a more comprehensive regulon (high sensitivity) but one contaminated with false targets (low specificity), and vice-versa [10].

What are SnNOUT and SpPIN, and how can I use them?

These are useful clinical mnemonics that can be adapted for interpreting computational results [11]:

- SnNOUT: A highly Sensitive test, when Negative, helps to Out The condition. If your algorithm is known to be highly sensitive for detecting a specific regulon, and it returns a negative result (finds no association) for a particular gene, you can be confident that gene is not part of that regulon.

- SpPIN: A highly Specific test, when Positive, helps to In The condition. If your algorithm is highly specific, and it returns a positive result for a gene-regulator link, you can be confident that this link is genuine.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My regulon prediction algorithm has a high false discovery rate.

Description: Your predictions contain many false positives, meaning your results lack specificity. This leads to wasted time and resources on validating incorrect targets.

Solution:

- Increase the Score Threshold: The most direct action is to raise the cutoff for your binding score, correlation value, or statistical significance (e.g., make your p-value threshold more stringent) [4].

- Incorporate Additional Data Filters: Use orthogonal data to filter your initial predictions. For example:

- Integrate chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) data to ensure binding events occur in open chromatin regions [12] [10].

- Use ChIP-seq data for the transcription factor to validate binding sites directly [12] [10].

- Leverage Hi-C or other 3D genome interaction data to prioritize genes that are in physical proximity to the binding site [10].

- Validate with a Gold Standard: Compare your predictions against a small set of experimentally validated, high-confidence regulon members to recalibrate your threshold.

Problem: My algorithm is failing to identify known members of a regulon.

Description: Your predictions have a high false negative rate, indicating low sensitivity. You are missing genuine regulatory relationships.

Solution:

- Lower the Score Threshold: Relax your statistical or score thresholds to capture a wider net of potential targets [4].

- Use More Sensitive Functional Assays: If based on expression correlation, consider using more sensitive single-cell multiomics approaches (like Epiregulon) that can detect activity decoupled from expression levels [12].

- Check Data Quality and Integration: Low sensitivity can stem from poor-quality input data. Ensure your gene expression and chromatin accessibility data are of high depth and quality. Algorithms that co-analyze paired multiomics data from the same cells can improve sensitivity by providing a more integrated view of regulation [12].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Benchmarking a New Regulon Prediction Algorithm

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of a new regulon prediction method against a known gold standard dataset.

Materials:

- A gold standard set of positive controls (known TF-target gene pairs) and negative controls (non-target genes).

- Your dataset (e.g., scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data).

- Computational environment to run your algorithm.

Methodology:

- Run the Algorithm: Execute your regulon prediction tool on your test dataset.

- Compare to Gold Standard: Create a confusion matrix by comparing your algorithm's predictions to the gold standard [3] [11]:

- True Positives (TP): Gold standard pairs correctly predicted by your algorithm.

- False Positives (FP): Pairs predicted by your algorithm that are not in the gold standard.

- True Negatives (TN): Non-pairs correctly ignored by your algorithm.

- False Negatives (FN): Gold standard pairs missed by your algorithm.

- Calculate Metrics:

- Sensitivity = TP / (TP + FN)

- Specificity = TN / (TN + FP)

- Generate an ROC Curve: Systematically vary the prediction score threshold of your algorithm from low to high. For each threshold, calculate the resulting sensitivity and (1 - specificity). Plot these points to create a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) provides a single metric of overall performance [8] [9].

Workflow Visualization: The following diagram illustrates the logical process of the trade-off and its analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Regulon Prediction Research

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function in Regulon Analysis |

|---|---|

| Single-cell Multiomics Data (e.g., paired scRNA-seq + scATAC-seq) | Provides simultaneous measurement of gene expression and chromatin accessibility in single cells, enabling inference of regulatory activity. [12] |

| ChIP-seq Data (from ENCODE, ChIP-Atlas) | Provides direct evidence of transcription factor binding to genomic DNA, used to validate and refine predicted binding sites. [12] [10] |

| Hi-C or Chromatin Interaction Data | Maps the 3D architecture of the genome, helping to link distal regulatory elements (like enhancers) to their target gene promoters. [10] |

| Gold Standard Validation Sets (e.g., from knockTF, CRISPRi/a screens) | Serves as a benchmark for true positive and true negative TF-target interactions, essential for calculating sensitivity and specificity. [12] |

| ROC Curve Analysis | A standard graphical plot and methodology for visualizing the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity at all possible classification thresholds. [8] [9] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between an operon and a regulon?

An operon is a set of neighboring genes on a genome that are transcribed as a single polycistronic message under the control of a common promoter. In contrast, a regulon is a broader concept; it is a maximal group of co-regulated operons (and sometimes individual genes) that may be scattered across the genome. A regulon encompasses all operons regulated by a single transcription factor (TF) or a specific regulatory mechanism [13] [14].

FAQ 2: Why is balancing sensitivity and specificity critical in regulon prediction algorithms?

Achieving a balance between sensitivity (the ability to identify all true member operons of a regulon) and specificity (the ability to exclude non-member operons) is a core challenge. Over-prioritizing sensitivity can lead to false positives, where operons are incorrectly assigned to a regulon, diluting the true biological signal and complicating downstream analysis. Conversely, over-prioritizing specificity can lead to false negatives, resulting in an incomplete picture of the regulatory network. This trade-off is central to developing reliable models, as features that increase predictive power for one can diminish the other [15] [16].

FAQ 3: What are the main computational approaches for predicting regulons ab initio?

The primary ab initio approaches are:

- Co-expression and Motif Analysis: This method identifies sets of co-expressed genes or operons from transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-seq or microarrays) and then searches for statistically enriched, conserved regulatory motifs in their promoter regions. Clusters of operons sharing a significant motif are predicted to form a regulon [13] [14].

- Phylogenetic Footprinting: This approach leverages comparative genomics by using reference genomes to identify orthologous operons. The upstream regulatory regions of these orthologs are analyzed to find conserved motifs, which are then used to infer co-regulation and define regulons in the target organism [13].

- Machine Learning-Based Prediction: This involves building classifiers (e.g., logistic regression models) that use promoter sequence features—such as TF motif scores, DNA shape parameters, and sigma factor binding information—to predict whether a gene or operon belongs to a specific, data-inferred regulon [15].

FAQ 4: My predicted regulon has a high-coverage motif, but validation shows weak regulatory activity. What could be the cause?

This discrepancy often points to an activity-specificity trade-off encoded in the regulatory system. The motif may be suboptimal by design. In enhancers and transcription factors, suboptimal features (like weaker binding motifs) can reduce transcriptional activity but increase specificity, ensuring the gene is only expressed in the correct context. Optimizing these features for activity can lead to promiscuous binding and loss of specificity. Your prediction may have correctly identified the binding site, but its inherent submaximal strength results in weaker observed activity [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Number of Promoter Sequences for Motif Discovery

Problem: Reliable motif discovery requires a sufficient number of promoter sequences. For a regulon with only a few known operons, the dataset may be too small for statistically robust motif identification.

Solutions:

- Utilize Phylogenetic Footprinting: Expand your promoter set by identifying orthologous operons for your query operon in other, closely related bacterial species. This can dramatically increase the number of informative promoters. For example, one study increased the percentage of operons with over 10 regulatory sequences from 40.4% to 84.3% using this strategy [13].

- Leverage Integrated Databases: Use servers like DMINDA, which have pre-computed operon predictions and orthology relationships for thousands of bacterial genomes, to automatically extract orthologous promoter sets [13].

Issue 2: Poor Performance of Machine Learning Models in Predicting Regulon Membership

Problem: A classifier trained solely on a transcription factor's primary motif score fails to accurately predict membership in an inferred regulon (e.g., low AUROC score).

Solutions:

- Incorporate Advanced Sequence Features: Move beyond simple motif scores. Engineer your feature set to include:

- DNA Shape Features: Parameters like minor groove width and propeller twist can refine binding site predictions.

- Extended Motif Context: Account for potential multimeric binding of the TF by searching for extended or dimeric motifs.

- Sigma Factor Features: Include information about the -10/-35 box sequences and spacer length for the relevant sigma factor [15].

- Investigate Model Interpretability: Use tools like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to identify which features your model deems important. This can reveal if the regulon structure depends on features you haven't yet considered, guiding further investigation [15].

Issue 3: Validating the Biological Reality of a Computationally Inferred Regulon

Problem: You have a set of operons inferred to be co-regulated through a top-down approach (e.g., Independent Component Analysis of RNA-seq data), but need to confirm this has a biochemical basis.

Solutions:

- Build a Quantitative Promoter Model: Develop a machine learning model to predict regulon membership based solely on promoter sequence features, as described in the solution to Issue 2. The ability to build an accurate model (e.g., cross-validation AUROC >= 0.8) strongly suggests the regulon's structure is encoded in the genome via TF binding sites [15].

- Benchmark Against High-Confidence Resources: Compare your inferred regulon to high-quality, manually curated meta-resources like CollecTRI or DoRothEA. These collections integrate signed TF-gene interactions from multiple sources and have been benchmarked for accurate TF activity inference in perturbation experiments [18].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ab Initio Regulon Prediction Using Co-expression and Comparative Genomics

This protocol outlines the RECTA pipeline for identifying condition-specific regulons by integrating transcriptomic and genomic data [14].

1. Input Data Preparation:

- Genome Sequence: Obtain the target bacterial genome sequence.

- Transcriptomic Data: Collect gene expression data (e.g., microarray or RNA-seq) from experiments under the condition of interest and appropriate controls.

2. Identify Co-expressed Gene Modules (CEMs):

- Process the expression data using a clustering package (e.g., the

hclusterpackage in R). - Group genes with highly correlated expression patterns across the experimental conditions into CEMs.

3. Predict Operon Structures:

- Use a computational tool like DOOR2 to identify the operon structures throughout the genome [13] [14].

- Map the co-expressed genes from Step 2 to their respective predicted operons. An entire operon is assigned to a CEM if one or more of its genes are members.

4. Motif Discovery:

- For each CEM, extract the DNA sequence upstream of the transcription start site (e.g., 300 bp) for every operon in the module.

- Use a de novo motif finding tool (e.g., BOBRO or tools within the DMINDA server) on this set of promoter sequences to identify significantly enriched and conserved regulatory motifs [13].

5. Predict and Annotate Regulons:

- Compare the top significant motifs from all CEMs based on similarity and cluster them. Each cluster of similar motifs, associated with a set of operons, represents a candidate regulon.

- Compare the predicted motifs to known transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) in databases (e.g., JASPAR, RegTransBase) using the MEME suite to hypothesize the identity of the governing TF [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the RECTA pipeline:

Protocol 2: Validating Regulons with Machine Learning on Promoter Sequences

This protocol uses machine learning to validate that the structure of an inferred regulon is specified by its members' promoter sequences [15].

1. Define Regulon Membership:

- Obtain a set of genes/operons belonging to a specific regulon from a top-down inference method (e.g., Independent Component Analysis) or a database (e.g., RegulonDB).

2. Engineer Promoter Sequence Features:

- For each gene in the genome, create a feature vector from its promoter region. Key features include:

- TF Binding Motif Score: The match score of the position weight matrix (PWM) for the regulator of interest.

- DNA Shape Features: Calculated structural properties of the DNA helix.

- Sigma Factor Features: Motif scores and Hamming distances for -10/-35 boxes, plus spacer length.

- Genomic Context: Strand direction and distance from the binding site to the transcription start site.

3. Train a Classification Model:

- Label genes as positive (in the regulon) or negative (not in the regulon).

- Train a logistic regression classifier using the engineered features to predict regulon membership.

4. Evaluate Model Performance:

- Use cross-validation and calculate the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC). An AUROC >= 0.8 is typically considered good performance and indicates that the regulon membership can be explained by promoter sequence features, supporting its biochemical reality [15].

Key Reagent and Resource Tables

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools for Regulon Prediction

| Tool Name | Function | Key Feature | Reference/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOOR2 | Operon prediction | Database of predicted and known operons for >2,000 bacteria | [13] [14] |

| DMINDA | Motif discovery & analysis | Integrates phylogenetic footprinting and multiple motif finding algorithms | [13] |

| iRegulon | Motif discovery & regulon prediction | Uses motif and track discovery on co-regulated genes to infer TFs and targets | [19] |

| RECTA | Condition-specific regulon prediction | Pipeline integrating co-expression data with comparative genomics | [14] |

| CollecTRI/DoRothEA | Curated TF-regulon database | Meta-resource of high-confidence, signed TF-gene interactions | [18] |

Table 2: Performance of Sequence Features in Regulon Prediction Models

This table summarizes the contribution of different feature types to the accuracy of machine learning models predicting regulon membership in E. coli, based on a study that achieved AUROC >= 0.8 for 85% of tested regulons [15].

| Feature Category | Specific Features | Utility & Context | Approx. Model Improvement* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary TF Motif | ChIP-seq or ICA-derived motif score | Sufficient for ~40% of regulons (e.g., ArgR) | Baseline |

| Extended TF Binding | Dimeric or extended motifs | Accounts for multimeric TF binding (e.g., hexameric ArgR) | Critical for specific cases |

| DNA Shape Features | Minor groove width, propeller twist | Provides structural context beyond the primary sequence | Contributes to improved accuracy |

| Sigma Factor Features | -10/-35 box score, spacer length | Defines core promoter context | Lower individual contribution |

Note: *The median improvement in AUROC when using the full set of engineered features versus using the primary TF motif alone was 0.15 [15].

In the field of computational biology, regulon prediction algorithms are essential for deciphering the complex gene regulatory networks that control cellular processes. These algorithms aim to identify sets of genes (regulons) that are co-regulated by transcription factors, forming the foundational building blocks for understanding systems-level biology. However, the accuracy of these predictions is fundamentally governed by the balance between two critical statistical measures: sensitivity (the ability to correctly identify true regulon members) and specificity (the ability to correctly exclude non-members) [20] [21].

When this balance is disrupted, two types of errors emerge that significantly skew biological interpretations: false positives (incorrectly predicting a gene is part of a regulon) and false negatives (failing to identify true regulon members) [22] [23]. In therapeutic development contexts, these errors can have profound consequences—from misidentifying drug targets to developing incomplete understanding of disease mechanisms. This technical support document examines the sources and impacts of these errors and provides actionable troubleshooting guidance for researchers working with regulon prediction algorithms.

Understanding the Core Concepts: Definitions and Relationships

Key Error Types and Their Definitions

In the context of regulon prediction, evaluation metrics are essential for quantifying algorithm performance and understanding potential error types [22] [23].

| Term | Definition | Biological Research Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| False Positive (FP) | A gene incorrectly predicted as a regulon member | Wasted resources validating non-existent relationships; incorrect network models |

| False Negative (FN) | A true regulon member missed by the algorithm | Incomplete regulatory networks; missed therapeutic targets |

| Sensitivity (Recall) | Proportion of true regulon members correctly identified: TP/(TP+FN) | High value ensures comprehensive regulon mapping |

| Specificity | Proportion of non-members correctly excluded: TN/(TN+FP) | High value ensures efficient use of validation resources |

| Precision | Proportion of predicted members that are true members: TP/(TP+FP) | High value indicates reliable predictions for experimental follow-up |

| F1 Score | Harmonic mean of precision and sensitivity | Balanced measure of overall prediction quality |

The Sensitivity-Specificity Trade-Off in Algorithm Design

The relationship between sensitivity and specificity is typically inverse—increasing one often decreases the other [20] [21]. This fundamental trade-off manifests in regulon prediction through classification thresholds. A higher threshold for including genes in a regulon increases specificity but reduces sensitivity, while a lower threshold has the opposite effect. Optimal threshold setting depends on the research goal: drug target identification may prioritize specificity to reduce false leads, while exploratory network mapping may prioritize sensitivity to ensure comprehensive coverage [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Prediction Errors

FAQ: Addressing False Positives in Regulon Prediction

Q: Our experimental validation consistently fails to confirm predicted regulon members. How can we reduce these false positives?

A: False positives frequently arise from over-reliance on single evidence types or insufficient evolutionary conservation analysis. Implement these strategies:

- Integrate phylogenetic footprinting: Use tools like Regulogger to identify and exclude predictions where regulatory motifs aren't conserved across related species. This approach can improve specificity up to 25-fold compared to methods using cis-element detection alone [2].

- Apply motif clustering: Implement co-regulation scoring (CRS) between operons based on motif similarity, which has demonstrated superior performance over gene functional relatedness scores and partial correlation scores [13].

- Utilize protein fusion evidence: Identify functional relationships between non-homologous proteins by detecting fusion events in other organisms, but apply tighter BLAST cutoffs (E-value < 10⁻⁵) to reduce false links [24].

Q: Our predicted regulons contain many apparently unrelated genes. How can we improve functional coherence?

A: This indicates potential false positives from non-specific motif matching:

- Exclude homologous upstream regions: Remove motifs where >33% of instances occur upstream of homologous genes to avoid confounding by sequence similarity rather than true co-regulation [24].

- Implement ensemble methods: Combine predictions from multiple algorithms (conserved operons, protein fusions, phylogenetic profiles) to require convergent evidence [24].

- Validate with expression correlation: In bacterial systems, test predictions against microarray gene-expression datasets from diverse conditions (e.g., 466 conditions for E. coli) using Fisher's Exact Test to verify co-expression patterns [13].

FAQ: Addressing False Negatives in Regulon Prediction

Q: We suspect our regulon predictions are missing key members based on experimental evidence. How can we improve sensitivity?

A: False negatives often result from overly stringent thresholds or insufficient ortholog information:

- Expand ortholog sets for motif discovery: For prokaryotic systems, include orthologous operons from multiple reference genomes (average 84 orthologs per operon in E. coli studies) to improve signal detection for regulons with few members [13].

- Adjust classification thresholds: Implement methods like Regression Optimal (RO) or Threshold Bayesian GBLUP (BO) that optimize thresholds to balance sensitivity and specificity, potentially improving sensitivity by 145-250% over standard approaches [20].

- Include divergently transcribed genes: Use broader operon definitions that include divergent transcription units, which can reveal additional co-regulated genes missed by strict operon definitions [24].

Q: Our single-cell regulatory network analysis misses known cell-type-specific regulators. How can we improve detection?

A: For single-cell data, specific technical factors can increase false negatives:

- Optimize feature selection: Use genes detected in at least 10% of all single cells as a cutoff to ensure sufficient signal while maintaining cell type representation [25].

- Apply SCENIC framework: Utilize this pipeline which combines GRNBoost (TF-target identification), RcisTarget (direct target validation via motif analysis), and AUCell (regulon activity scoring) to improve comprehensive regulon detection [25].

- Address platform-specific dropouts: Account for technology differences (e.g., full-length Smart-seq2 vs. 3'-end 10X Chromium) that create systematic detection gaps across cell types [25].

Experimental Protocols for Error Assessment and Validation

Protocol: Quantitative Assessment of Prediction Accuracy

This protocol adapts methodologies from validated regulon prediction studies to evaluate algorithm performance [13]:

Materials Required:

- Reference regulon set (e.g., RegulonDB for E. coli)

- Genome-scale expression data across multiple conditions

- Ortholog databases for phylogenetic footprinting

Procedure:

- Calculate co-regulation scores between all operon pairs based on motif similarity

- Construct regulatory network using graph model with operons as nodes and CRS values as edge weights

- Apply modified Fisher's Exact Test to assess overlap between predictions and co-expressed gene modules from expression data

- Compute regulon coverage score by measuring overlap with documented regulons in reference databases

- Compare against known benchmarks - for E. coli, evaluate performance on the 12 largest regulons (each containing ≥20 operons) as rigorous test cases

Interpretation: Well-performing algorithms should show statistically significant enrichment (p < 0.05) for both co-expression overlap and reference regulon coverage, with balanced sensitivity and specificity metrics.

Protocol: Single-Cell Regulon Validation Workflow

This protocol validates regulon predictions in single-cell RNA-seq data using the SCENIC framework [25]:

Materials Required:

- Single-cell expression matrix (loom format)

- Transcription factor list for target organism (e.g., allTFs_hg38.txt for human)

- Motif databases for RcisTarget

Procedure:

- Preprocess data: Subset to highly variable genes while preserving all transcription factors

- Run GRNBoost2: Identify potential TF-target relationships from expression covariation

- Execute RcisTarget: Prune indirect targets by requiring presence of cognate motifs in regulatory regions

- Calculate AUCell scores: Quantify regulon activity in individual cells

- Validate specificity: Confirm that identified regulons distinguish cell types in embedding visualizations

Troubleshooting: If validation fails, check TF coverage in your dataset (>50% of TFs in reference list should be detected), adjust minimum gene detection thresholds, and verify appropriate species-specific parameters.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Regulon Analysis

| Category | Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motif Discovery | AlignACE [24] | Discovers regulatory motifs in upstream regions | Prokaryotic and eukaryotic regulon prediction |

| BOBRO [13] | Identifies conserved cis-regulatory motifs | Bacterial phylogenetic footprinting | |

| Network Inference | SCENIC [25] | Infers regulons from single-cell data | Single-cell RNA-seq analysis |

| GRNBoost [25] | Identifies TF-target relationships | Expression-based network construction | |

| Conservation Analysis | Regulogger [2] | Filters predictions by regulatory conservation | Specificity improvement across species |

| Reference Databases | RegulonDB [13] | Curated database of known regulons | Benchmarking bacterial predictions |

| DoRothEA [26] | TF-regulon resource for eukaryotes | Prior knowledge incorporation | |

| Evaluation Metrics | AUCell [25] | Scores regulon activity in single cells | Single-cell validation |

| F1 Score Optimization [20] | Balances precision and sensitivity | Algorithm performance assessment |

The accurate prediction of regulons requires careful attention to the balance between sensitivity and specificity throughout the analytical workflow. By understanding the specific sources of false positives and false negatives—from initial motif discovery through final network validation—researchers can implement appropriate troubleshooting strategies to refine their predictions. The integration of evolutionary conservation evidence, multi-algorithm approaches, and systematic validation protocols provides a robust framework for minimizing both error types. As regulon prediction continues to evolve, particularly with the expansion of single-cell datasets, maintaining this critical balance will remain essential for generating biologically meaningful insights that reliably inform therapeutic development.

What is a regulon and why is its inference important?

A regulon is a set of genes transcriptionally regulated by the same protein, known as a transcription factor (TF) [27]. Accurately reconstructing these regulatory networks is a fundamental challenge in genomics, essential for understanding how cells control gene expression, respond to environmental changes, and how non-coding genetic variants influence disease [28]. Regulon inference allows researchers to move from a static genome sequence to a dynamic understanding of cellular control systems.

Why is balancing sensitivity and specificity crucial in regulon prediction?

In regulon prediction, sensitivity measures the ability to correctly identify all true members of a regulon (true positive rate), while specificity measures the ability to correctly exclude genes that are not part of the regulon (true negative rate) [1]. There is an inherent trade-off between these two measures: increasing sensitivity often decreases specificity and vice versa [29].

This balance is critical because:

- High sensitivity is important for identifying all potential regulon members to avoid missing biologically important relationships [29].

- High specificity is essential for classifying regulatory outcomes accurately and avoiding false leads in experimental validation [29].

- The optimal balance depends on the research goal: exploratory studies may prioritize sensitivity to generate hypotheses, while focused mechanistic studies may prioritize specificity to obtain high-confidence interactions.

Core Computational Methods for Regulon Inference

What are the primary comparative genomics methods for regulon prediction?

Three foundational methods form the basis of many regulon inference approaches, particularly in prokaryotes where experimental data may be limited [24]:

Conserved Operon Method: Predicts functional interactions based on genes that are consistently found together in operons across multiple organisms. Genes maintained in the same operonic structure across evolutionary distances are likely coregulated [24].

Protein Fusion Method: Identifies functional relationships between proteins that appear as separate entities in one organism but are fused into a single polypeptide chain in another organism [24].

Phylogenetic Profiles (Correlated Evolution): Based on the observation that functionally related genes tend to be preserved or lost together across evolutionary lineages. If homologs of two genes are consistently present or absent together across genomes, they are likely functionally related [24].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Comparative Genomics Methods for Regulon Prediction

| Method | Basic Principle | Key Strength | Common Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conserved Operons | Genes consistently located together in operons across species are likely coregulated | Most useful for predicting coregulated sets of genes [24] | Prokaryotic regulon prediction, especially in closely related species |

| Protein Fusions | Separate proteins in one organism fused into single chain in another indicate functional relationship | Reveals functional interactions not obvious from genomic context alone [24] | Identifying functionally linked proteins in metabolic pathways |

| Phylogenetic Profiles | Genes with similar presence/absence patterns across genomes are functionally related | Does not require proximity in genome; works for dispersed regulons [24] | Reconstruction of ancient regulatory networks and pathways |

How have regulon inference methods evolved with new technologies?

Modern approaches have integrated multiple data types to improve accuracy:

Machine Learning Integration: Methods like LINGER use neural networks pretrained on external bulk data (e.g., from ENCODE) and refined on single-cell multiome data, achieving 4-7× relative increase in accuracy over previous methods [28].

Multi-Omics Data Fusion: Contemporary tools combine chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq), TF binding (ChIP-seq), and gene expression data to infer TF-gene regulatory relationships [28].

Lifelong Learning: Leveraging knowledge from large-scale external datasets to improve inference from limited single-cell data, addressing the challenge of learning complex regulatory mechanisms from sparse data points [28].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

What is a standard workflow for comparative genomics-based regulon inference?

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for regulon inference integrating comparative genomics approaches:

What is the detailed protocol for regulon inference using known regulatory motifs?

For researchers with prior knowledge of transcription factor binding motifs, the following workflow provides a systematic approach:

Input Requirements:

- Position Weight Matrix (PWM) for the transcription factor of interest

- Genomic sequences for target organisms

- Operon predictions and orthology information

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Genome Scanning: Scan all upstream regions in target genomes using the PWM to identify candidate TF binding sites [27].

- CRON Construction: Automatically compute Clusters of co-Regulated Orthologous operons (CRONs) by grouping orthologous operons with candidate TF binding sites [27].

- Cluster Ranking: Rank CRONs by conservation level (number of genomes with candidate sites) and site scores [27].

- Manual Curation: Use interactive tools (e.g., RegPredict web interface) to examine genomic context and functional annotations for each CRON [27].

- Regulon Assembly: Combine all accepted CRONs to build the final reconstructed TF regulon [27].

How is de novo regulon inference performed without prior motif information?

When no prior information about regulatory motifs is available, researchers can apply this ab initio approach:

Input Requirements:

- Set of potentially co-regulated genes (from pathway analysis, expression data, or genomic context)

- Multiple related genomes from the same taxonomic group

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Training Set Construction: Compile upstream regions of potentially co-regulated genes from one or multiple related genomes [27].

- Motif Discovery: Identify candidate TF binding motifs using iterative algorithms (e.g., MEME-like approaches) [27].

- PWM Construction: Build Position Weight Matrix profiles from discovered motifs [27].

- Comparative Validation: Scan for similar motifs upstream of orthologous genes in related genomes to assess conservation [27].

- Regulon Expansion: Use refined PWM to scan genomes for additional instances, expanding the regulon beyond initial training sets [27].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

How can researchers address poor specificity in regulon predictions?

Problem: Prediction algorithm identifies too many false positive regulon members, reducing experimental validation efficiency.

Solutions:

- Increase Evolutionary Distance Threshold: Use more distantly related genomes for comparative analysis; conservation across larger evolutionary distances provides stronger evidence for true regulatory relationships [24].

- Incorporate Motif Evidence: Refine predicted regulons to include only genes with significant regulatory motifs in their upstream regions [24].

- Adjust Score Cutoffs: Implement stricter clustering cutoffs (e.g., evolutionary distance score >0.1) to exclude links found only in very closely related organisms [24].

- Exclude Homologous Sequences: Set interaction matrix values to zero for homologous proteins (BLAST E-value <10⁻⁶) to prevent clusters from being dominated by homologous genes rather than coregulated genes [24].

What approaches improve sensitivity for detecting weak regulatory relationships?

Problem: Algorithm misses genuine regulon members, particularly those with weak binding sites or condition-specific regulation.

Solutions:

- Use Close Homologs: Rather than strict orthologs, use close homologs to identify conserved operons, increasing sensitivity despite potential false positives [24].

- Relax Operon Definitions: Include divergently transcribed genes in operon definitions to capture more potential regulatory relationships [24].

- Integrate Multiple Evidence Types: Combine predictions from conserved operons, protein fusions, and phylogenetic profiles rather than relying on a single method [24].

- Leverage External Data: Use lifelong learning approaches that incorporate atlas-scale external data to enhance detection of regulatory patterns [28].

How can researchers validate computational regulon predictions?

Problem: Uncertainty about which experimental methods best validate computational regulon predictions.

Solutions:

- ChIP-seq Validation: Use chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing to experimentally verify TF binding at predicted sites [28].

- eQTL Consistency Check: Compare cis-regulatory predictions with expression quantitative trait loci studies to assess biological relevance [28].

- Motif Conservation Analysis: Verify that predicted regulatory motifs are evolutionarily conserved across related species [30].

- Functional Enrichment Testing: Assess whether predicted regulon members show enrichment for specific biological functions or pathways.

Research Reagents and Tools

What are the essential computational tools for regulon inference?

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Regulon Inference and Their Applications

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Data Input Requirements | Typical Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| RegPredict | Comparative genomics reconstruction of microbial regulons [27] | Genomic sequences, ortholog predictions, operon predictions | Predicted regulons, CRONs, regulatory motifs |

| LINGER | Gene regulatory network inference from single-cell multiome data [28] | Single-cell multiome data, external bulk data, TF motifs | Cell type-specific GRNs, TF activities |

| AlignACE | Discovery of regulatory motifs in upstream sequences [24] | DNA sequences from upstream regions of candidate regulons | Identified regulatory motifs, position weight matrices |

| MicrobesOnline | Operon predictions and orthology relationships [27] | Genomic sequences from multiple organisms | Predicted operons, phylogenetic trees, ortholog groups |

| ENCODE | Reference annotations of functional genomic elements [31] | N/A (database) | Registry of candidate regulatory elements (cREs) |

| RefSeq Functional Elements | Curated non-genic functional elements [32] | N/A (database) | Experimentally validated regulatory regions |

What genomic databases are essential for regulon inference?

MicrobesOnline: Provides essential data on operon predictions and orthology relationships critical for comparative genomics approaches [27].

ENCODE Encyclopedia: Offers comprehensive annotations of candidate regulatory elements, including promoter-like, enhancer-like, and insulator-like elements across multiple cell types [31].

RefSeq Functional Elements: Contains manually curated records of experimentally validated regulatory elements with detailed feature annotations [32].

RegPrecise Database: Captures predicted TF regulons reconstructed by comparative genomics across diverse prokaryotic genomes [27].

Advanced Topics: Integrating Multiple Data Types

How do modern methods integrate single-cell and bulk data?

Contemporary approaches like LINGER use a three-step process:

- Bulk Data Pretraining: Neural network models are pretrained on external bulk data from resources like ENCODE, which contains hundreds of samples across diverse cellular contexts [28].

- Single-Cell Refinement: Elastic Weight Consolidation applies regularization that preserves knowledge from bulk data while adapting to single-cell data, using Fisher information to determine parameter sensitivity [28].

- Regulatory Strength Estimation: Shapley values estimate the contribution of each TF and regulatory element to target gene expression [28].

What is the role of motif information in regulon inference?

TF binding motifs serve as critical prior knowledge that can be integrated through:

- Manifold Regularization: Enriching for TF motifs binding to regulatory elements that belong to the same regulatory module [28].

- Binding Site Prediction: Using Position Weight Matrices to scan genomic sequences for potential TF binding sites [27].

- Evolutionary Conservation: Identifying motifs conserved upstream of orthologous genes across multiple species [30].

The following diagram illustrates how different data types are integrated in modern regulon inference approaches:

Frequently Asked Questions

How many genomes are needed for reliable comparative genomics-based regulon prediction?

There is no fixed number, but studies suggest analyzing up to 15 genomes simultaneously provides reasonable coverage [27]. The key consideration is phylogenetic distribution—genomes should be sufficiently related to show conservation but sufficiently distant to avoid spurious conservation due to recent common ancestry.

Can these methods be applied to eukaryotic systems?

While many foundational methods were developed for prokaryotes, the core principles extend to eukaryotes with modifications. Eukaryotic methods must account for more complex genome organization, including larger intergenic regions, alternative splicing, and chromatin structure. Approaches like LINGER have been successfully applied to human data [28].

What evidence supports the accuracy of computational regulon predictions?

Accuracy is typically assessed using:

- ChIP-seq Validation: Comparison with experimentally determined TF binding sites [28].

- eQTL Consistency: Overlap with expression quantitative trait loci [28].

- Functional Enrichment: Enrichment of predicted regulon members for specific biological functions or pathways.

- Evolutionary Conservation: Preservation of regulatory relationships across related species [30].

How does single-cell data improve regulon inference compared to bulk data?

Single-cell data enables:

- Cell Type-Specific Networks: Inference of distinct regulatory networks for different cell types within heterogeneous samples [28].

- Enhanced Resolution: Identification of regulatory relationships that may be obscured in bulk data averaging [28].

- Rare Cell Population Analysis: Detection of regulatory programs in minority cell populations not observable in bulk data.

What are common pitfalls in regulon inference and how can they be avoided?

Over-reliance on Single Evidence Types: Use integrated approaches combining multiple lines of evidence [24].

Ignoring Evolutionary Distance: Account for phylogenetic relationships between species to distinguish meaningful conservation from recent common ancestry [24].

Inadequate Handling of Common Domains: Exclude proteins linked to many partners through common domains to avoid false connections [24].

Poor Quality Motif Information: Use carefully curated position weight matrices and validate motif predictions experimentally where possible [27].

From Theory to Practice: Key Algorithms and Workflows for Effective Regulon Inference

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Conceptual Foundations

FAQ 1.1: What is the fundamental difference between an operon and a regulon?

An operon is a physical cluster of genes co-transcribed into a single mRNA molecule under the control of a single promoter. Classically described in prokaryotes, like the lac operon in E. coli, it represents a basic unit of transcription [33] [34].

A regulon is a broader functional unit encompassing a set of operons (or genes) that are co-regulated by the same transcription factor, even if they are scattered across the genome. Elucidating regulons is key to understanding global transcriptional regulatory networks [13].

FAQ 1.2: How does comparative genomics help in balancing sensitivity and specificity in regulon prediction?

Sensitivity (finding all true members) and specificity (excluding false positives) are often in tension. Comparative genomics helps balance them by using evolutionary conservation as a filter.

- Increasing Specificity: Methods like Regulogger assign confidence scores to predicted regulon members based on whether orthologous genes in other species share similar cis-regulatory motifs. Predictions without this conserved regulatory signal are considered likely false positives, which can increase specificity up to 25-fold over methods that use motif detection alone [2].

- Maintaining Sensitivity: Phylogenetic footprinting uses upstream sequences of orthologous genes from multiple related genomes to identify conserved, and thus likely functional, regulatory motifs. This provides a larger, more informative dataset for motif finding, especially for regulons with few members in the host genome, thereby supporting sensitivity [13].

FAQ 1.3: What are the primary sources of false positives and false negatives in these methods?

- False Positives:

- Motif Prediction: De novo motif prediction can have a high false positive rate due to randomly matching sequences that are not biologically significant [13].

- Functional Unrelatedness: Some operons contain genes with no obvious functional relationship but are co-regulated because they are required under the same environmental conditions [33].

- False Negatives:

- Insufficient Data: For regulons with very few operons, there is not enough signal for accurate motif detection without leveraging orthologous sequences from other genomes [13].

- Evolutionary Divergence: If the regulatory mechanism is not conserved across the reference genomes used for comparison, the signals will be missed [2].

FAQ 1.4: What is a fusion protein in the context of genomics and proteomics?

A fusion protein (or chimeric protein) is created through the joining of two or more genes that originally coded for separate proteins. Translation of this fusion gene results in a single polypeptide with functional properties derived from each original protein [35].

They can be:

- Naturally Occurring: Often result from chromosomal translocations in cancer cells (e.g., BCR-ABL in chronic myelogenous leukemia) [35] [36].

- Artificially Engineered: Created for research (e.g., GFP-tagged proteins for visualization) or therapeutics (e.g., Etanercept) [35] [37].

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Regulon Prediction

Problem: Abnormally high rate of false-positive regulon predictions.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Many predicted regulon members have no functional connection. | Spurious matches from low-specificity motif detection [13]. | Implement a conservation-based filter like a Regulog analysis. Use tools like Regulogger to calculate a Relative Conservation Score (RCS) and retain only predictions where the regulatory motif is conserved in orthologs [2]. |

| Predicted regulons are too large and contain incoherent functional groups. | Poor motif similarity thresholds and clustering parameters [13]. | Use a more robust co-regulation score (CRS) that integrates motif similarity, orthology, and operon structure instead of clustering motifs directly [13]. |

| General poor performance and lack of precision. | Using a single, poorly chosen reference genome for phylogenetic footprinting [2]. | Select multiple reference genomes from the same phylum but different genera to ensure sufficient evolutionary distance and reduce background conservation noise [13]. |

Experimental Protocol: Building a Conserved Regulog

Aim: To identify high-confidence, conserved regulon members for a transcription factor of interest.

- Input Data Preparation: Collect upstream regulatory sequences (e.g., 500 bp) for all operons in your target genome.

- Ortholog Identification: For each operon, identify orthologous operons in a carefully selected set of reference genomes (e.g., from the same phylum but different genus) [13].

- Motif Discovery: Use a phylogenetic footprinting tool (e.g., a Gibbs sampler) on the sets of orthologous upstream sequences to identify conserved cis-regulatory motifs [2].

- Genome Scanning: Scan the target genome's upstream regions with the discovered motif pattern to generate an initial, broad list of putative regulon members.

- Conservation Scoring: For each putative member, calculate a conservation score (e.g., RCS) based on the fraction and number of its orthologs that also contain the same cis-regulatory motif [2].

- High-Confidence Set Definition: Apply a threshold to the conservation score to generate a final set of high-confidence regulon members, the regulog.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this protocol:

Troubleshooting Phylogenetic Profile Generation

Problem: Phylogenetic profiles lack power, failing to identify known functional linkages.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Profiles are too sparse (mostly zeros). | Reference genome set is too small or phylogenetically too close [38]. | Expand the set of reference genomes to cover a broader evolutionary range. This increases the information content of the presence/absence patterns. |

| Profiles are too dense (mostly ones). | Reference genome set is too narrow or contains many closely related strains. | Curate reference genomes to ensure they are non-redundant and represent a meaningful evolutionary distance [13]. |

| High background noise, many nonsensical linkages. | Using only presence/absence without quality filters. | Incorporate quality measures, such as requiring a minimum bitscore or alignment quality for defining "presence" [38]. |

Troubleshooting Fusion Protein Detection

Problem: Failure to detect known or validate novel fusion proteoforms.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-Seq fusion finders do not report an expected fusion. | Low sensitivity of a single fusion finder algorithm [36]. | Use a multi-tool approach. Pipelines like FusionPro can run several fusion finders (e.g., SOAPfuse, TopHat-Fusion, MapSplice2) and integrate their results for greater sensitivity [36]. |

| Fusion transcript is detected but no corresponding peptide is identified via MS/MS. | Custom database does not contain the full-length fusion proteoform sequence [36]. | Use a tool like FusionPro to build a customized database that includes all possible fusion junction isoforms and full-length sequences, not just junction peptides, for MS/MS searching [36]. |

| High false-positive fusion transcripts. | Limitations of individual fusion finders when used in isolation [36]. | Apply stringent filtering based on the number of supporting reads, and use integrated results from multiple algorithms to improve specificity. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Methodology | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Regulogger [2] | A computational algorithm that uses comparative genomics to eliminate spurious members from predicted gene regulons. | Critical for enhancing the specificity of regulon predictions. Produces regulogs—sets of coregulated genes with conserved regulation. |

| FusionPro [36] | A proteogenomic tool for sensitive detection of fusion transcripts from RNA-Seq data and construction of custom databases for MS/MS identification. | Improves sensitivity in fusion proteoform discovery by integrating multiple fusion finders and providing full-length sequences for MS. |

| Phylogenetic Profiling [38] | A method that encodes the presence or absence of a protein across a set of reference genomes into a bit-vector (profile). | Used to infer functional linkages; proteins with similar profiles are likely to be in the same pathway. Balance between sensitivity/specificity is tuned by the choice of reference genomes. |

| Co-Regulation Score (CRS) [13] | A novel score measuring the co-regulation relationship between a pair of operons based on motif similarity and conservation. | Superior to scores based only on co-expression or phylogeny. Foundation for accurate, graph-based regulon prediction that improves both sensitivity and specificity. |

| DOOR Database [13] | A resource containing complete and reliable operon predictions for thousands of bacterial genomes. | Provides high-quality operon structures, which is a prerequisite for accurate motif finding and regulon inference. |

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Comparative Genomics Methods

| Method | Key Metric | Reported Value / Effect | Impact on Sensitivity/Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulogger [2] | Increase in Specificity | Up to 25-fold increase over cis-element detection alone. | Dramatically improves specificity without significant loss of sensitivity. |

| Co-Regulation Score (CRS) [13] | Prediction Accuracy | Consistently better performance than other scores (PCS, GFR) when validated against known regulons. | Improves overall accuracy, leading to more reliable regulon maps. |

| Phylogenetic Footprinting for Regulon Prediction [13] | Data Sufficiency | Percentage of operons with >10 orthologous promoters increased from 40.4% (using only host genome) to 84.3% (using reference genomes). | Greatly enhances sensitivity, especially for small regulons, by providing more data for motif discovery. |

Table 2: Common Sequencing Preparation Issues Affecting Genomic Analyses

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Impact on Downstream Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Input / Quality [39] | Low starting yield; smear in electropherogram; low library complexity. | Poor data quality leads to reduced sensitivity in all subsequent comparative genomics methods. |

| Fragmentation / Ligation [39] | Unexpected fragment size; inefficient ligation; adapter-dimer peaks. | Biases in library construction can create artifacts mistaken for biological signals (e.g., fusions), harming specificity. |

| Amplification / PCR [39] | Overamplification artifacts; high duplicate rate. | Reduces complexity and can skew quantitative assessments, affecting phylogenetic profiling and expression analyses. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section provides direct answers to common technical and methodological challenges encountered during cis-regulatory motif discovery, framed within the research objective of balancing algorithmic sensitivity and specificity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My motif discovery tool runs very slowly on large ChIP-seq datasets. What can I do to improve efficiency? A: Computational runtime is a significant challenge, particularly with large datasets from ChIP-chip or ChIP-seq experiments, which can contain thousands of binding regions [40]. Some tools, like Epiregulon, have been designed with computational efficiency in mind and may offer faster processing times [12]. Furthermore, consider AMD (Automated Motif Discovery), which was developed to address efficiency concerns while maintaining the ability to find long and gapped motifs [40]. For any tool, check if you can adjust parameters such as the motif search space or use a subset of your data for initial parameter optimization.

Q2: How can I improve the accuracy of my motif predictions and reduce false positives? A: Accuracy is a central challenge in regulon prediction. The BOBRO algorithm addresses this through the concept of 'motif closure', which provides a highly reliable method for distinguishing actual motifs from accidental ones in a noisy background [41]. Using a discriminative approach that incorporates a carefully selected set of background sequences for comparison can also substantially improve specificity. Tools like AMD and Amadeus have shown improved performance by using the entire set of promoters in the genome of interest as a background model, rather than simpler models based on pre-computed k-mer counts [40].

Q3: My tool is struggling to identify long or gapped motifs. Are some algorithms better suited for this? A: Yes, this is a known limitation. Many algorithms are primarily designed for short, contiguous motifs (typically under 12 nt) [40]. For long or gapped motifs (which can constitute up to 30% of human promoter motifs), you may need specialized tools. AMD was specifically developed to handle such motifs through a stepwise refinement process [40]. While tools like MEME and MDscan allow adjustable motif lengths, their effectiveness can be low for this specific task [40].

Q4: What is the best way to benchmark the performance of different motif discovery tools on my data? A: The Motif Tool Assessment Platform (MTAP) was created to automate this process. MTAP automates motif discovery pipelines and provides benchmarks for many popular tools, allowing researchers to identify the best-performing method for their specific problem domain, such as data from human, mouse, fly, or bacterial genomes [42]. It helps map a method M to a dataset D where it has the best expected performance [42].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: Low Recall of Known Target Genes

- Problem: The motif discovery method fails to identify a significant portion of previously validated target genes for a transcription factor.

- Solution: Consider using the Epiregulon method, which is designed for high recovery (recall) of target genes, albeit with a potential, modest trade-off in precision [12]. Ensure your input sequence set (e.g., promoters) is correctly defined and that you are using appropriate background sequences to maximize signal-to-noise ratio.

Issue: Inability to Detect Motifs in Specific Biological Contexts

- Problem: The tool fails to infer transcription factor activity when that activity is decoupled from mRNA expression, such as after drug treatment that affects protein function or complex formation.

- Solution: Methods that rely solely on the correlation between TF mRNA and target gene expression will fail here. Epiregulon's default "co-occurrence method" weights target genes based on the co-occurrence of TF expression and chromatin accessibility at its binding sites, making it less reliant on TF expression levels and capable of handling post-transcriptional modulation [12].

Issue: Tool Performance is Inconsistent Across Different Genomes

- Problem: A tool that works well on yeast data performs poorly on data from higher organisms like humans or mice.

- Solution: This is a common problem, as the regulatory sequences of metazoans are more complex [40]. Use benchmarking platforms like MTAP to identify tools validated on your organism of interest. Tools like Amadeus and AMD have been developed with a focus on improving performance on metazoan datasets [40].

Quantitative Performance Data

To make informed choices about motif discovery tools, it is essential to compare their performance on standardized metrics. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from the literature.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Motif Discovery Tools on Prokaryotic Data

| Tool | Performance Coefficient (PC) | Key Strengths | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BOBRO | 41% | High sensitivity and selectivity in noisy backgrounds; uses "motif closure" | [41] |

| Best of 6 Other Tools | 29% | Varies by tool and specific dataset | [41] |

| AMD | Substantial improvement over others | Effective identification of gapped and long motifs | [40] |

Table 2: Benchmarking Results on Metazoan and Perturbation Data

| Tool / Aspect | Recall (Sensitivity) | Precision | Context of Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epiregulon | High | Moderate | PBMC data; prediction of target genes from knockTF database [12] |

| SCENIC+ | Low (failed for 3/7 factors) | High | PBMC data; prediction of target genes [12] |

| Epiregulon | Successful | N/A | Accurate prediction of AR inhibitor effects across different drug modalities [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: De Novo Motif Finding with BOBRO

Purpose: To identify statistically significant cis-regulatory motifs at a genome scale from a set of promoter sequences [43].

Materials and Inputs:

- Promoter file: A file containing DNA sequences in standard FASTA format.

- Background file (optional): A file containing background genomic sequences in standard FASTA format for comparative analysis [43].

Methodology:

- Command Execution: Run the BOBRO tool from the command line.

- For basic de novo motif finding:

perl BBR.pl 1 <promoters.fa> - For motif finding with a custom background:

perl BBR.pl 2 <promoters.fa> <background.fa>[43]

- For basic de novo motif finding:

- Algorithmic Process: The BOBRO algorithm employs two key ideas:

- It assesses the possibility of each position in a promoter being the start of a conserved motif.

- It uses the concept of 'motif closure' to reliably distinguish actual motifs from accidental ones, enhancing both sensitivity and specificity [41].

- Output Analysis: The primary output file will be named

promoters.closures. This file contains:- A summary of the input data and commands.

- For each motif candidate, detailed information including:

- Motif seed (the core sequence used to find the motif).

- Motif position weight matrix and consensus sequence.

- A table showing all aligned motif instances [43].

Protocol: Workflow for the AMD Algorithm

Purpose: To perform de novo discovery of transcription factor binding sites, including long and gapped motifs, from a set of foreground sequences compared to background sequences [40].

Materials and Inputs:

- Foreground sequences: A set of DNA sequences (e.g., from co-expressed genes or ChIP-seq peaks) in FASTA format.

- Background sequences: A set of control DNA sequences for statistical comparison (e.g., shuffled sequences or genomic promoters) [40].

Methodology: The AMD method is a multi-step refinement process, as illustrated in the workflow below:

AMD Motif Discovery Workflow

- Step 1: Initial Core Motif Filtering. The algorithm starts with 61,440 potential core motifs defined as two triplets of specified bases with a gap of 0-14 unspecified bases. Each motif is scored based on fold enrichment and a Z-score. The top 50 motifs are selected for the next step [40].

- Step 2: Core Motif Degeneration. The selected primary core motifs are made more degenerate by enumerating all possible motifs differing in at most 4 of the 6 core positions. The most significant degenerate motif is chosen for each primary core [40].

- Step 3: Core Motif Extension. The core motifs are extended by adding non-informative flanks (N characters) to each side. The extended motifs are evaluated, and the one with the largest Z-score is selected [40].

- Step 4: Motif Refinement. The extended motifs are refined using a Maximum A Posteriori (MAP) probability score, which incorporates a third-order Markov model calculated from the background sequences to account for genomic composition [40].

- Step 5: Redundancy Removal. The final step involves removing redundant motifs from the candidate pool to produce a non-redundant set of predictions [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Motif Discovery Experiments

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example or Note |

|---|---|---|