Sequencing Platform Showdown: Evaluating Illumina, PacBio, and Oxford Nanopore for Advanced Microbial Ecology

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of modern DNA sequencing platforms—Illumina, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)—for microbial ecology research.

Sequencing Platform Showdown: Evaluating Illumina, PacBio, and Oxford Nanopore for Advanced Microbial Ecology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of modern DNA sequencing platforms—Illumina, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)—for microbial ecology research. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of short- and long-read technologies, their methodological applications in 16S rRNA and metagenomic studies, and strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. Through a critical validation of recent comparative studies on soil, respiratory, and aquatic microbiomes, we synthesize key performance metrics on taxonomic resolution, error rates, and diversity assessments. The review concludes with a forward-looking perspective on integrating artificial intelligence and hybrid sequencing approaches to overcome current limitations and unlock novel discoveries in clinical and environmental microbiology.

From Short to Long Reads: Understanding Sequencing Technologies for Microbial Diversity

The field of DNA sequencing has undergone a revolutionary transformation, evolving from a laborious, low-throughput process to a powerful, high-throughput technology that has become a cornerstone of modern biological research. This evolution is categorized into distinct generations, each marked by significant technological leaps. First-generation sequencing, dominated by the Sanger method, enabled the decoding of initial genomes but was limited by its scalability [1] [2]. The advent of second-generation sequencing (NGS), or next-generation sequencing, introduced massively parallel sequencing, dramatically reducing cost and time while increasing output, thus enabling large-scale genome studies [1]. Most recently, third-generation sequencing (TGS) technologies have emerged, characterized by their ability to sequence single molecules in real-time and generate exceptionally long reads, overcoming some of the fundamental limitations of previous generations [3] [1].

This progression is particularly impactful for microbial ecology research. The ability to rapidly and cost-effectively sequence complex microbial communities from environmental samples has revolutionized our understanding of microbial diversity, function, and dynamics [4] [5]. While NGS platforms like Illumina provide high accuracy for profiling microbial composition, TGS platforms from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) are proving invaluable for assembling complete genomes and resolving complex genomic regions directly from metagenomic samples [6] [5]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these sequencing platforms, framing their performance within the specific context of microbial ecology.

The core distinction between sequencing generations lies not just in output, but in their underlying biochemistry and data characteristics. The table below summarizes the fundamental properties of each major platform type.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Sequencing Platform Generations

| Platform Type | Example Technologies | Key Sequencing Principle | Read Length | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Generation | Sanger Sequencing | Dideoxy chain-termination with capillary electrophoresis [1] [2] | 500-1000 bp [2] | Very high accuracy (~99.99%); long reads for its era [2] | Very low throughput; high cost per base |

| Second-Generation (NGS) | Illumina MiSeq | Sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible dye-terminators [1] [6] | 36-300 bp [1] | High throughput; low cost per base; high accuracy (error rate 0.1-1%) [4] | Short reads; PCR amplification bias [4] [3] |

| Third-Generation (TGS) | PacBio SMRT | Real-time sequencing of single molecules via fluorescence in zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) [3] [1] | Average 10,000-25,000 bp [1] | Very long reads; detects epigenetic modifications [3] | Higher cost; historically higher error rates (addressed with HiFi mode) [3] [7] |

| Third-Generation (TGS) | Oxford Nanopore | Real-time detection of electrical current changes as DNA strands pass through protein nanopores [1] [7] | Average 10,000-30,000 bp [1] | Extremely long reads; portability; direct epigenetic detection [3] [7] | Variable error rates, though improving with new chemistries (e.g., R10, Q20+) [8] [7] |

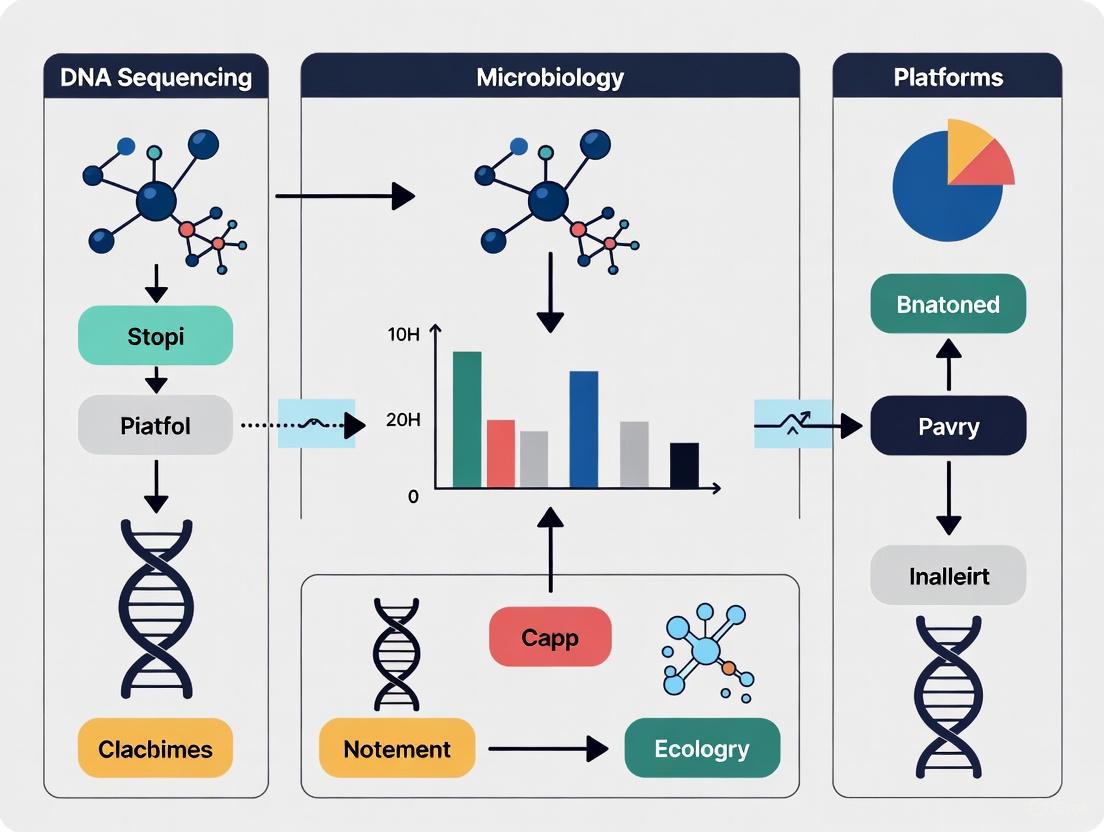

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and logical relationship of the different sequencing technologies within a research context.

Performance Comparison in Microbial Ecology Applications

Accuracy and Read Length

Accuracy and read length are often a trade-off. Sanger sequencing remains the gold standard for accuracy for single, targeted sequences, making it ideal for validating genetic variants discovered by other methods [9] [2]. NGS platforms like Illumina provide high per-base accuracy, which is excellent for detecting single-nucleotide variations in amplicon studies (e.g., 16S rRNA sequencing) [4]. However, their short reads struggle to resolve repetitive regions or distinguish between closely related species [3] [6].

TGS platforms have historically had higher error rates, but recent chemistry improvements have been substantial. PacBio's HiFi mode generates circular consensus sequences (CCS) with accuracies exceeding 99.8% by sequencing the same molecule multiple times [3] [7]. ONT's latest R10.4.1 flow cell and Q20+ chemistry have also significantly improved raw read accuracy, with one study finding ONT R10 & Q20+ achieved the highest sample success rate for DNA barcoding [8] [7]. The defining feature of TGS is its long read length, which is transformative for metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), enabling the recovery of near-complete genomes from complex environments like soil [5].

Throughput, Cost, and Efficiency

The cost-effectiveness of a platform depends heavily on the project's scale and goals. Sanger sequencing is cost-prohibitive for sequencing entire genomes or many samples [8] [2]. NGS drastically reduced the cost per base, making large-scale projects like whole-genome sequencing feasible. However, for targeted sequencing of hundreds of samples, benchtop NGS sequencers can be efficient [9].

A direct comparison study estimated the cost-effectiveness of DNA barcoding relative to Sanger sequencing. It found that TGS platforms become more cost-effective when a study requires barcoding more than 61 samples for ONT Flongle, 183 for ONT MinION, or 356 for PacBio [8]. In terms of workflow, ONT protocols were noted as the quickest for library preparation [8]. For large-scale metagenomic projects, deep long-read sequencing (e.g., ~100 Gbp per sample), while a significant investment, has proven capable of recovering thousands of novel microbial genomes from complex terrestrial habitats, a task that is exceptionally challenging with short-read technologies alone [5].

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Key Microbial Ecology Applications

| Application | Best-Suited Platform | Experimental Support & Performance Data |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | Illumina MiSeq (for high-throughput, cost-effective profiling) [4] | Standard for microbiome studies; provides high-depth, accurate short reads suitable for amplicons [4]. |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing of Isolates | PacBio HiFi/Revio (for complete, closed genomes) [3] [6] | PacBio generated two contigs covering the entire 5-Mb, two-chromosome Vibrio parahaemolyticus genome, while NGS produced dozens of fragmented contigs [6]. |

| Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) from Complex Samples | Oxford Nanopore (for high-quality MAG recovery) [5] | Deep Nanopore sequencing of 154 soil/sediment samples yielded 15,314 novel microbial species genomes, expanding the prokaryotic tree of life by 8% [5]. |

| Detection of DNA Modifications (e.g., 6mA) | PacBio SMRT & Oxford Nanopore (for direct epigenetic detection) [7] | Both platforms can natively detect DNA modifications. A 2025 study found SMRT and ONT's Dorado tool consistently delivered strong performance for bacterial 6mA profiling [7]. |

| Rapid In-Field Pathogen Surveillance | Oxford Nanopore (for portability and real-time analysis) [7] | ONT's portability enables sequencing outside traditional labs. Used for rapid sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 and norovirus [2] [7]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Metagenomic Sequencing for MAG Recovery Using Long-Reads

This protocol is adapted from the large-scale soil microbiome study that recovered over 15,000 novel genomes using Nanopore sequencing [5].

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Collect environmental samples (e.g., soil, sediment). Use a robust DNA extraction kit designed for complex environmental samples to obtain high-molecular-weight (HMW) genomic DNA. DNA integrity is critical for long-read sequencing.

- Library Preparation (ONT Ligation Sequencing): The MFD-LR MAG catalogue was built using this standard ONT workflow [5].

- DNA Repair and End-Prep: Repair DNA damage and blunt the ends of the HMW DNA fragments.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate ONT-specific adapters to the prepared DNA ends. These adapters facilitate attachment to the nanopores and prime the sequencing reaction.

- Purification: Use solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads to purify the adapter-ligated library from excess reagents.

- Sequencing: Load the library onto a Nanopore flow cell (R9.4.1 or R10.4.1). Sequence with a high-output device like the GridION or PromethION to achieve deep coverage (~100 Gbp per sample) [5]. Basecalling can be performed in real-time.

- Bioinformatic Analysis (mmlong2 workflow): The custom mmlong2 workflow was pivotal for high-quality MAG recovery [5].

- Assembly: Perform metagenome assembly using a long-read assembler (e.g., Flye).

- Binning: Recover MAGs using an ensemble of binners, incorporating differential coverage (using multi-sample data), iterative binning, and extraction of circular MAGs (cMAGs).

- Quality Assessment: Check MAG completeness and contamination using tools like CheckM.

Protocol 2: Diagnostic Gene Validation via Sanger Sequencing

This protocol outlines the use of Sanger sequencing for validating mutations in a diagnostic context, as used for primary hyperoxaluria [9].

- Target Amplification: Design primers flanking the genomic region of interest (e.g., a specific exon). Perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify the target from purified genomic DNA.

- PCR Cleanup: Purify the PCR product to remove excess primers, nucleotides, and enzymes that could interfere with the sequencing reaction.

- Sanger Sequencing Reaction: This is a cycle sequencing reaction using dye-terminator chemistry [10] [2].

- Set up a reaction containing the purified PCR product, a sequencing primer, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and fluorescently labeled ddNTPs.

- Run the reaction in a thermal cycler. The incorporation of a ddNTP randomly terminates the growing DNA chains, producing a ladder of fragments.

- Purification: Remove unincorporated dye terminators from the reaction.

- Capillary Electrophoresis: Load the purified products onto an automated DNA sequencer (e.g., ABI 310 Genetic Analyzer). The fragments are separated by size via capillary electrophoresis, and a laser detects the fluorescent dye at the end of each fragment [9].

- Data Analysis: Software (e.g., Phred) converts the fluorescence data into a chromatogram and a text sequence. Visual inspection of the chromatogram is crucial to verify base calls, especially around areas of poor resolution [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sequencing Workflows

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Molecular-Weight (HMW) DNA Extraction Kit | To isolate long, intact DNA strands from complex samples, minimizing shearing. | Essential for preparing libraries for TGS to maximize read lengths from soil or sediment samples [5]. |

| PacBio SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 | Prepares DNA fragments by ligating hairpin adapters to create circular templates for SMRT sequencing. | Used for generating HiFi reads for de novo genome assembly or isoform sequencing (Iso-Seq) [3]. |

| Oxford Nanopore Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK109) | A standard kit for preparing genomic DNA libraries for Nanopore sequencing via ligation of adapters. | The primary kit used for large-scale metagenomic surveys like the Microflora Danica project [5]. |

| Illumina TruSeq DNA Custom Amplicon Kit | Designed for targeted sequencing of specific genomic regions by creating amplicon libraries. | Used in diagnostic validation studies to screen for mutations in multiple genes simultaneously via NGS [9]. |

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | A reliable method for extracting high-quality DNA from small volumes of blood or cell cultures. | Used to obtain template DNA from patient blood samples for Sanger sequencing of disease-associated genes like AGXT, GRHPR, and HOGA1 [9]. |

| Agencourt AMPure XP Beads | SPRI magnetic beads used for efficient purification and size selection of DNA fragments in library prep. | A universal reagent for cleaning up enzymatic reactions and selecting appropriate fragment sizes in NGS and TGS workflows [9] [5]. |

The evolution from Sanger to third-generation sequencing has provided microbial ecologists with a powerful suite of tools, each with distinct strengths. The choice of platform is not a matter of identifying a single "best" technology, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific biological question.

For high-throughput, low-cost profiling of microbial communities via 16S rRNA or shotgun metagenomics, Illumina-based NGS remains the workhorse. For applications where long-range genomic context is paramount—such as assembling complete genomes from complex metagenomes, resolving structural variations, or phasing haplotypes—PacBio and Oxford Nanopore TGS are unparalleled. The latest improvements in accuracy have made these technologies suitable for an ever-broadening range of applications. Sanger sequencing continues to hold value as an orthogonal method for validating key findings with its exceptional base-level accuracy.

The future of sequencing in microbial ecology lies in the intelligent integration of these technologies. Hybrid approaches, using Illumina for breadth and cost-efficiency and TGS for depth and resolution in complex regions, will become standard. Furthermore, as TGS continues to mature in accuracy, throughput, and cost-effectiveness, it is poised to become the dominant technology for comprehensive genomic and epigenomic characterization of the vast, uncultured microbial diversity on our planet.

In the field of microbial ecology research, selecting the appropriate DNA sequencing platform is a critical foundational decision. The choice primarily revolves around a central divide: the established dominance of second-generation short-read sequencing (exemplified by Illumina) and the rapidly advancing capabilities of third-generation long-read sequencing (championed by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)). Each technology offers a distinct set of strengths and trade-offs in accuracy, read length, cost, and application suitability. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these platforms, framing their performance within the specific context of analyzing complex microbial communities, such as those found in soil and other environmental samples.

The fundamental difference between these platforms lies in their method of determining the sequence of DNA bases.

- Illumina (Short-Read): Utilizes Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS). DNA fragments are amplified on a flow cell to create clusters, and fluorescently labeled nucleotides are incorporated. As each nucleotide is added, a camera captures its specific fluorescent color, determining the base identity. This process generates vast volumes of highly accurate but short reads (50-300 bases) [11].

- PacBio (Long-Read): Employs Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing. A single DNA molecule is sequenced by a polymerase enzyme fixed at the bottom of a tiny well called a Zero-Mode Waveguide (ZMW). The polymerase incorporates fluorescent nucleotides, and the light pulse from each incorporation is detected in real-time. Its key innovation is HiFi (High Fidelity) sequencing, where a circularized DNA template is read multiple times, producing long reads (15-20 kb) with exceptional accuracy (>99.9%) by generating a consensus sequence [12] [13].

- Oxford Nanopore (Long-Read): Based on the nanopore sensing system. A single strand of DNA or RNA is electrophoretically driven through a protein nanopore embedded in a membrane. As each nucleotide passes through the pore, it causes a characteristic disruption in the electric current. This change in current is decoded to determine the DNA sequence. This technology can produce the longest reads, sometimes exceeding a megabase, and can directly detect base modifications [12] [14].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each technology.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Sequencing Technologies

| Feature | Illumina (Short-Read) | PacBio (HiFi Long-Read) | ONT (Long-Read) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology Basis | Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) [11] | Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing [12] | Nanopore Sensing [12] |

| Typical Read Length | 50-300 bp [12] | 15,000-20,000 bp [12] [13] | 20 bp -> 1 Mb+ [12] |

| Typical Raw Read Accuracy | >Q30 (99.9%) [11] | ~Q30 (99.9%) [13] [15] | ~Q20 (99%) with latest chemistry [16] [17] |

| Primary Error Type | Low, predominantly substitutions | Random errors reduced via HiFi consensus [14] | Systematic indels, especially in homopolymers; improved with R10.4.1 flow cell [12] [14] |

| DNA Modification Detection | Requires bisulfite treatment | Direct detection of 5mC, 6mA without bisulfite treatment [12] | Direct detection of a wide range of DNA and RNA modifications [12] [17] |

The following diagram illustrates the core technological principles of each platform.

Performance Evaluation in Microbial Ecology

For microbial ecologists, the theoretical principles of a technology are less important than its performance in real-world applications like 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing for taxonomic profiling and shotgun metagenomics for functional insight and genome reconstruction.

Taxonomic Profiling with 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

A 2025 study directly compared Illumina (V4 and V3-V4 regions), PacBio (full-length), and ONT (full-length) for sequencing bacterial diversity in soil microbiomes. After normalizing sequencing depth, the key finding was that ONT and PacBio provided comparable assessments of bacterial diversity, with PacBio showing a slight edge in detecting low-abundance taxa [16]. Crucially, the study concluded that despite ONT's inherently higher error rate, it did not significantly distort the interpretation of well-represented microbial taxa, and all technologies enabled clear clustering of samples by soil type [16].

Table 2: Performance in 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing for Microbial Ecology

| Metric | Illumina (V3-V4) | PacBio (Full-Length) | ONT (Full-Length) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Region | Hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4) [16] | Full-length 16S rRNA gene [16] | Full-length 16S rRNA gene [16] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Limited to genus level, ambiguous due to short length [16] [15] | High, species- and often strain-level [16] [15] | High, species- and often strain-level [16] |

| Community Profile Accuracy | Reliable for overall structure | Comparable to ONT, slightly better for low-abundance taxa [16] | Comparable to PacBio for well-represented taxa [16] |

| Primary Advantage | Low cost per sample, high throughput | High accuracy with long read length | Real-time data, long reads, lower instrument cost |

Shotgun Metagenomics and Genome Reconstruction

Long-read technologies excel in shotgun metagenomics by producing contiguous sequences that span repetitive regions, which are a major challenge for short-read assemblers.

- Genome Assembly Quality: A comprehensive 2022 benchmarking study using complex synthetic microbial communities found that PacBio Sequel II generated the most contiguous assemblies, reconstructing 36 out of 71 full genomes from a mock community, followed by ONT MinION (22 genomes) [18]. The same study noted that PacBio provided the most accurate assemblies, while Illumina and MGI platforms had the lowest indel rates [18].

- Recovery of Novel Diversity: A landmark 2025 study leveraged deep ONT sequencing of 154 complex terrestrial samples, recovering 15,314 previously undescribed microbial species [5]. This demonstrates the unique power of long-read sequencing to access the vast "microbial dark matter" in highly complex environments like soil, a task that is exceptionally difficult with short-read technology alone [5].

- Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs): A 2022 clinical microbiome study compared Illumina and PacBio HiFi metagenomics and found that while both methods produced compositionally similar MAGs, long-read assemblies yielded a greater number and more complete MAGs [15]. The study also found approximately twice the proportion of long reads could be assigned functional annotations compared to short reads [15].

Table 3: Performance in Shotgun Metagenomics and Genome Assembly

| Metric | Illumina (Short-Read) | PacBio (HiFi Long-Read) | ONT (Long-Read) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly Contiguity | Low; fragmented due to repeats [18] | High; produces contiguous assemblies [18] | High; produces contiguous assemblies [18] |

| Number of Recovered MAGs | Lower | Higher [15] | Higher (dependent on depth and workflow) [5] |

| MAG Quality (Completeness) | Lower | Higher [15] | High (e.g., >15,000 MQ/HQ MAGs recovered [5]) |

| Variant Detection | Strong for SNVs, small indels | Strong for all variant types: SNVs, indels, SVs [12] | Strong for SNVs and SVs; historically weaker for indels in homopolymers [12] [14] |

| Functional Annotation | Standard | Improved recovery of functional sequences [15] | Improved recovery of functional sequences [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Platform Comparison

To ensure a fair and reproducible comparison between sequencing platforms, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following workflow, adapted from a 2025 soil microbiome study [16] and a 2022 benchmarking study [18], outlines a robust methodology.

Detailed Methodology:

Sample Selection and DNA Extraction:

- Use a well-characterized, complex sample. Synthetic mock communities with known strain compositions are ideal for absolute accuracy assessment [18]. Environmental samples (e.g., soil) are necessary for evaluating performance on novel diversity [16] [5].

- Perform High-Molecular-Weight (HMW) DNA extraction using kits designed to preserve long DNA fragments (e.g., Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep Kit) [16]. DNA quality and length are critical for long-read sequencing performance.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- For 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, amplify the full-length 16S rRNA gene using universal primers for long-read platforms (PacBio, ONT) and the V3-V4 or V4 region for Illumina [16].

- For shotgun metagenomics, follow the manufacturer's recommended protocols for each platform without size selection where possible to avoid bias [18] [15].

- Sequence the same DNA sample across all platforms. For a fair comparison, it is critical to normalize sequencing depth during bioinformatic analysis (e.g., by subsampling all datasets to the same number of reads) [16].

Bioinformatic Analysis and Metric Comparison:

- Process data from each platform using optimized, platform-specific bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., DADA2 for Illumina 16S, EMU for ONT 16S) [16].

- For metagenomics, use assemblers designed for the respective read type (e.g., metaSPAdes for Illumina, metaFlye for long reads) and standard binning tools (e.g., MetaBAT2) [5] [18].

- Compare the following key metrics:

- Taxonomic Profiling: Alpha and beta diversity, sensitivity for low-abundance taxa, and accuracy against a mock community ground truth [16] [18].

- Assembly and Binning: Contig N50, number of high-quality MAGs recovered, genome completeness and contamination [18] [15].

- Variant Calling: Precision and recall for identifying single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), and structural variants (SVs) [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists essential reagents and materials used in the comparative experiments cited in this guide.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Comparative Sequencing Studies

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevant Study / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep Kit (Zymo Research) | HMW DNA extraction from complex environmental samples like soil. | Used for soil DNA extraction in 16S rRNA sequencing platform comparison [16]. |

| SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 (PacBio) | Library preparation for PacBio HiFi sequencing on Sequel IIe/Revio systems. | Used for preparing 16S and metagenomic libraries [16] [15]. |

| Ligation Sequencing Kit (Oxford Nanopore) | Standard library prep for ONT DNA sequencing on MinION/PromethION. | Used in multiple metagenomic studies for library construction [5] [18]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard (Zymo Research) | Defined synthetic microbial community with known composition, used as a positive control and for benchmarking platform accuracy. | Used as a validation standard in multiple studies [16] [18]. |

| Native Barcoding Kit 96 (Oxford Nanopore) | Allows for multiplexing of up to 96 samples in a single ONT sequencing run. | Used for multiplexing samples in 16S sequencing study [16]. |

| MAS-ISO-seq for 10x Genomics (PacBio) | Library prep for high-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing with PacBio, enabling full-length transcriptome analysis. | Used in single-cell RNA sequencing protocol comparison [19]. |

The choice between Illumina, PacBio, and ONT is not about finding a single "best" technology, but rather selecting the right tool for the specific research question and context.

- Choose Illumina Short-Read Sequencing when: Your primary needs are high-throughput, low-cost per sample for large-scale cohort studies, and your analysis is focused on taxonomic profiling at the genus level or SNV calling where the highest base-level accuracy is required for variant detection [11] [16] [18].

- Choose PacBio HiFi Long-Read Sequencing when: Your research requires high accuracy (Q30) combined with long read lengths. This is ideal for resolving complex microbial communities to the species/strain level with 16S sequencing, generating high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), and comprehensively detecting all variant types (SNV, indel, SV) and base modifications in a single assay [12] [13] [15].

- Choose ONT Long-Read Sequencing when: Your priorities are maximal read length to span extremely long repeats, real-time data streaming for rapid pathogen identification or in-field sequencing, portability (MinION), or the direct detection of a broad range of DNA/RNA modifications. It is also a cost-effective option for generating long reads for assembly, though often requiring greater depth or computational polishing for highest consensus accuracy [12] [5] [17].

For many research groups, a multi-platform approach is becoming the most powerful strategy. A common paradigm is to use Illumina for broad, deep population screening and then employ long-read technology on a subset of key samples for deep investigation, genome resolution, and validation of complex genomic regions. As long-read technologies continue to reduce costs and improve throughput, they are poised to become the default choice for an increasing number of microbial genomics applications.

In microbial ecology, the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene serves as a foundational genetic marker for profiling complex bacterial and archaeal communities. This gene, approximately 1,500 base pairs in length, contains a unique mosaic of nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) interspersed with conserved areas [20]. The conserved regions enable the design of universal PCR primers, while the variable regions accumulate nucleotide changes over evolutionary time, providing signatures for taxonomic differentiation [21]. For decades, the selection of specific variable regions for amplification and sequencing has represented a critical methodological compromise, dictated by technological limitations and research objectives. While short-read sequencing platforms (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) have historically constrained researchers to target one or several hypervariable regions (~300-600 bp), the emergence of third-generation sequencing technologies (e.g., Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore) now enables routine high-throughput sequencing of the full-length 16S rRNA gene [22] [23]. This technological evolution necessitates a re-evaluation of historical practices, compelling researchers to understand precisely how the length and choice of targeted 16S regions directly impact the taxonomic resolution achievable in their microbiome studies.

The Compromise of Short Reads: Variable Region Performance

The inability of earlier high-throughput platforms to sequence the entire 16S rRNA gene forced researchers to target specific sub-regions, a practice that significantly influences downstream taxonomic results. Different variable regions possess varying degrees of discriminatory power, and their performance is not uniform across the bacterial kingdom.

In Silico Evidence of Differential Performance

In silico experiments, which extract sub-regions from full-length 16S sequences, starkly reveal the limitations of short-read approaches. One such analysis demonstrated that the V4 region performed poorest, with a striking 56% of in-silico amplicons failing to achieve confident species-level classification when matched to their correct sequence of origin. In contrast, using the full V1-V9 sequence allowed nearly all sequences to be accurately classified at the species level [21]. Furthermore, the choice of sub-region introduces taxonomic bias. For instance, the V1-V2 region performs poorly in classifying sequences from the phylum Proteobacteria, whereas the V3-V5 region struggles with classifying Actinobacteria [21]. This indicates that polymorphisms critical for distinguishing certain taxa are confined to specific variable regions.

Empirical Validation in Skin Microbiome Research

These computational findings are reinforced by empirical studies. A 2024 analysis of 141 skin microbiome samples sequenced on the PacBio platform concluded that while full-length sequencing provides superior taxonomic resolution, the V1-V3 region offers a resolution comparable to full-length 16S when compared to other common sub-regions like V3-V4 or V4 alone [22]. The study also confirmed that even full-length 16S sequencing cannot achieve 100% species-level resolution for complex skin communities, highlighting an inherent limitation of the 16S marker itself [22]. This makes the choice of the best possible sub-region all the more critical for studies using short-read technologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Common 16S rRNA Sub-Regions

| Target Region | Approximate Length | Species-Level Classification Efficacy | Taxonomic Biases / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1-V3 | ~500 bp | Good, reasonable approximation of diversity [21]. | Poor for Proteobacteria [21]. Superior for Escherichia/Shigella; best compromise for skin microbiome [22] [21]. |

| V3-V4 | ~600 bp | Variable performance. | Poor for Actinobacteria [21]. Good for Klebsiella [21]. |

| V4 | ~300 bp | Poor (56% failure rate in in-silico experiment) [21]. | Worst-performing region in clustering experiments [21]. |

| V6-V9 | ~400 bp | Moderate. | Best sub-region for Clostridium and Staphylococcus [21]. |

| Full-Length (V1-V9) | ~1500 bp | Excellent (near-universal species-level classification) [21]. | Provides the highest taxonomic resolution and avoids regional biases [22] [21]. |

The Advantage of Full-Length Sequencing: Maximizing Resolution

The primary advantage of sequencing the entire 16S rRNA gene is the dramatic increase in taxonomic resolution. By capturing the entirety of the gene's sequence variation, full-length sequencing provides the maximum amount of phylogenetic information available from this marker, enabling more precise classification.

Direct Comparisons in Human Microbiome Studies

A direct comparative study on human saliva, subgingival plaque, and fecal samples demonstrated this advantage clearly. The research showed that while both Illumina (V3-V4) and PacBio (V1-V9) platforms assigned a similar proportion of reads to the genus level (~95%), PacBio full-length sequencing assigned a significantly higher proportion of reads to the species level (74.14% vs. 55.23%) [23]. This confirms that the additional sequence information in the full-length gene directly translates to improved discriminatory power at the species level, which is often crucial for understanding the functional roles of microbes in health and disease. Notably, the overall community profiles clustered by sample type rather than by sequencing platform, indicating that both methods capture similar broad-scale community structures despite the difference in resolution [23].

Resolving Intragenomic Variation

Another critical benefit of accurate full-length sequencing is the ability to resolve intragenomic 16S copy number variation. Many bacterial genomes contain multiple copies of the 16S rRNA gene, and these copies can contain subtle nucleotide polymorphisms within the same organism [21]. Modern PacBio Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) generates highly accurate long reads (HiFi reads) that are sufficiently precise to distinguish these subtle differences. Rather than being mere noise, these intragenomic 16S gene copy variants can provide strain-level information [21]. Appropriate bioinformatic treatment of this variation allows researchers to move beyond species-level identification to potentially discriminate between closely related strains, which can exhibit vastly different phenotypic properties [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Short-Read vs. Long-Read 16S Sequencing Platforms

| Factor | Short-Read (e.g., Illumina) | Long-Read (e.g., PacBio SMRT) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Region | Single or multiple variable regions (e.g., V4, V3-V4) [24] | Full-length 16S rRNA gene (V1-V9) [23] |

| Typical Read Length | ≤ 300 bp (paired-end) [21] | >1,500 bp [21] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus-level (sometimes species) [24] | Species-level and strain-level (via copy variants) [21] [23] |

| Species-Level Assignment | Lower (e.g., 55%) [23] | Higher (e.g., 74%) [23] |

| Ability to Resolve 16S Copy Variants | Limited | Yes, with high accuracy [21] |

| Primary Limitation | Limited phylogenetic information; regional taxonomic bias [21] | Higher cost per sample for equivalent read depth [23] |

Experimental Protocols for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

To generate the data supporting the comparisons above, standardized but platform-specific laboratory protocols are essential.

Laboratory Workflow for Full-Length 16S Sequencing

The following workflow is adapted from studies that successfully compared full-length and partial 16S sequencing [22] [23]:

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from samples (e.g., skin swabs, feces, saliva) using a kit designed for microbial lysis, such as the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit [22]. DNA quality and quantity should be rigorously assessed.

- Full-Length 16S Amplification: Amplify the ~1,500 bp full-length 16S rRNA gene using universal primers. A common primer pair is:

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare the PCR amplicons for sequencing using the platform-specific protocol. For PacBio, this involves damage repair, end repair, and adapter ligation with the SMRTbell Template Prep Kit. The library is then sequenced on a platform like the PacBio Sequel II using SMRT cell technology [22].

In Silico Extraction of Sub-Regions

To directly compare the performance of full-length sequences against sub-regions, an in silico extraction can be performed [22] [21]:

- Begin with a high-quality dataset of full-length 16S rRNA sequences.

- Identify the primer binding sites in the conserved regions that flank the target variable regions (e.g., primers for V1-V3, V3-V4, V4).

- Using bioinformatic tools (e.g., Cutadapt), extract the sequence between each pair of primer sites, thereby generating in silico amplicons for each sub-region from the full-length data.

- Analyze both the full-length and extracted sub-region sequences using the same bioinformatics pipeline (e.g., DADA2 for Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or the RDP classifier) and compare the resulting taxonomic assignments [21].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality microbial genomic DNA from complex samples. | PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit [22]; QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit [25]. Designed to lyse tough microbial cell walls. |

| Universal 16S Primers | PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene or specific sub-regions. | Full-length: 27F/1492R [22] [23]. V3-V4: 341F/805R [25]. V4: 515F/806R [24]. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix | Accurate amplification of the 16S target with low error rates. | KOD One PCR Master Mix [22]. Critical for minimizing PCR-induced errors in amplicons. |

| Library Prep Kit | Preparation of amplicon libraries for sequencing on a specific platform. | SMRTbell Template Prep Kit (PacBio) [22] [25]; Nextera XT Kit (Illumina) [25]. |

| Curated Reference Database | Taxonomic classification of sequenced 16S reads. | Greengenes [21], SILVA, RDP [21]. Database choice and curation impact annotation accuracy [20]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Processing raw sequences, error-correction, taxonomic assignment, and diversity analysis. | DADA2 [23] (for ASVs), QIIME 2, MOTHUR. Essential for deriving biological insights from sequence data. |

The evidence is clear: the length and choice of the targeted 16S rRNA region are fundamental determinants of taxonomic resolution in microbiome studies. While targeting specific hypervariable regions with short-read platforms remains a practical choice under budget or DNA quality constraints, this approach entails significant compromises in species-level discrimination and introduces regional taxonomic biases [22] [21]. The emergence of third-generation sequencing technologies has made high-throughput, full-length 16S sequencing a reality, providing a level of resolution that begins to approach the full discriminatory potential of this genetic marker [23]. This allows researchers not only to achieve more accurate species-level classification but also to explore the implications of intragenomic 16S copy variation for strain-level ecology [21]. As long-read sequencing technologies continue to decline in cost and improve in accuracy, the routine use of full-length 16S sequencing is poised to become the new gold standard for amplicon-based microbial community profiling, enabling deeper and more precise insights into the composition and dynamics of microbial ecosystems across human health, biotechnology, and environmental sciences.

The selection of an appropriate DNA sequencing platform is a critical first step in microbial ecology research, as it directly influences the resolution, accuracy, and depth of microbial community characterization. The field now offers researchers a choice between second-generation short-read and third-generation long-read sequencing technologies, each with distinct performance profiles. This guide provides an objective comparison of current sequencing platforms based on key metrics—read depth, accuracy, and taxonomic resolution—to inform experimental design and platform selection for microbial ecology studies.

Sequencing Platform Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of major second and third-generation sequencing platforms based on benchmarking studies using complex synthetic microbial communities [18].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Sequencing Platforms for Microbial Ecology

| Sequencing Platform | Read Length | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Short (150-300 bp) | High accuracy (>99.9%), high throughput [4] | Limited taxonomic resolution at species level [16] [26] | 16S rRNA amplicon studies, shallow shotgun metagenomics [16] [18] |

| PacBio (Sequel II) | Long (full-length 16S) | High accuracy (>99.9%) with CCS, enables species-level ID [16] | Lower throughput, requires DNA size filtering [18] | High-resolution taxonomic profiling, genome assembly [16] [18] |

| Oxford Nanopore (MinION) | Long (full-length 16S) | Real-time sequencing, portability for field use [26] | Higher error rates than other platforms [16] [18] | In-field monitoring, rapid pathogen detection [26] |

| MGI DNBSEQ | Short (100-150 bp) | High quality, low indel rates, cost-effective [18] | Similar limitations to Illumina short-read technology | Large-scale metagenomic surveys where cost is a factor [18] |

The Impact of Sequencing Depth on Microbial Community Analysis

Sequencing depth, or the number of reads generated per sample, profoundly impacts the detection and quantification of microbial diversity. The required depth varies significantly depending on the complexity of the microbial community and the specific research question.

Table 2: Recommended Sequencing Depth for Different Microbial Study Types

| Study Type | Recommended Depth | Rationale | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Taxonomy | 1 million reads | Sufficient for stable taxonomic composition at higher ranks [27] | Achieves <1% dissimilarity to full depth profile [27] |

| Shotgun Metagenomics for AMR Genes | 80+ million reads | Necessary to capture full richness of AMR gene families [27] | Rarefaction curves plateau at ~80M reads for diverse environments [27] |

| Shallow Shotgun Metagenomics | 100,000-500,000 reads | Accurate abundance estimation for cost-effective large studies [18] | Spearman correlations >0.9 for community composition [18] |

Deeper sequencing reveals greater microbial diversity, particularly for detecting rare taxa and specific genetic elements like antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes. One study found that while 1 million reads per sample was sufficient to achieve a stable taxonomic profile (with less than 1% dissimilarity to the full profile), at least 80 million reads were required to recover the full richness of different AMR gene families in complex environmental samples [27]. Furthermore, additional allelic diversity was still being discovered in effluent samples even at 200 million reads, indicating that very deep sequencing is necessary to capture the complete genetic diversity of complex environments [27].

Experimental Protocols for Platform Comparison

Protocol 1: Comparative Evaluation of Sequencing Platforms for Soil Microbiomes

This protocol outlines the methodology for a direct comparison of Illumina, PacBio, and Oxford Nanopore technologies for 16S rRNA gene sequencing [16].

Sample Preparation:

- Sample Type: Three distinct soil types with three biological replicates each.

- DNA Extraction: Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep kit (Zymo Research).

- 16S Amplification:

- Illumina: Targeting V4 and V3-V4 regions.

- PacBio & ONT: Full-length 16S rRNA gene amplification with universal primers 27F and 1492R.

Sequencing & Analysis:

- Sequencing Depth: Normalized across platforms (10k, 20k, 25k, and 35k reads/sample).

- Bioinformatics: Standardized pipelines tailored to each platform.

- Analysis Metrics: Alpha and beta diversity, taxonomic resolution at different levels.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Sequencing Platforms Using Synthetic Microbial Communities

This approach uses constructed synthetic communities of known composition to objectively evaluate platform performance [18].

Community Construction:

- Complexity: 64-87 microbial genomic DNAs per mock community.

- Diversity: Spanning 29 bacterial and archaeal phyla.

- Design: Uneven abundance distribution spanning three orders of magnitude.

Performance Evaluation:

- Taxonomic Profiling: Comparison of observed vs. theoretical abundances.

- Assembly Metrics: Contiguity and accuracy of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs).

- Error Analysis: Substitution and indel rates by platform.

Workflow for Sequencing Platform Selection

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points for selecting an appropriate sequencing platform based on research goals:

Taxonomic Resolution Across Sequencing Platforms

The choice of sequencing platform and approach significantly impacts the level of taxonomic classification achievable.

Table 3: Taxonomic Resolution by Sequencing Approach

| Sequencing Approach | Optimal Taxonomic Level | Key Determinants of Resolution | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Read 16S | Genus to Family Level | Hypervariable region selection, reference database quality [16] | Use for large cohort studies focusing on community structure shifts |

| Long-Read 16S | Species Level | Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing [16] [26] | Ideal for identifying specific pathogens or key taxa |

| Shotgun Metagenomics | Species to Strain Level | Sequencing depth, genome completeness, binning algorithms [18] [4] | Required for functional potential and strain-level differentiation |

Long-read sequencing technologies significantly improve taxonomic resolution. A study comparing full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing with short-read approaches found that long-read sequencing "enables more robust classification at the species level" and "helps mitigate PCR biases and allows for better detection of rare or novel taxa" [26]. This enhanced resolution is particularly valuable for distinguishing between closely related microbial species that play different ecological roles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below details key laboratory reagents and their applications in microbial ecology sequencing studies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Sequencing Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Application | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep Kit | DNA Extraction | Efficient lysis and purification of microbial DNA from complex samples [16] | Soil and fecal sample preparation for 16S sequencing [16] |

| ZymoBIOMICS Gut Microbiome Standard | Quality Control | Defined microbial community for evaluating extraction and sequencing biases [16] | Protocol validation and cross-study comparisons |

| SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 | Library Preparation | Preparation of SMRTbell libraries for PacBio sequencing [16] | Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing [16] |

| Native Barcoding Kit 96 | Library Preparation | Multiplexing samples for Oxford Nanopore sequencing [16] | High-throughput amplicon sequencing on MinION platform [16] |

| Ion Plus Fragment Library Kit | Library Preparation | Preparation of libraries for ThermoFisher sequencing platforms [18] | Shotgun metagenomic sequencing of synthetic communities [18] |

The optimal choice of sequencing platform for microbial ecology research involves careful consideration of trade-offs between read depth, accuracy, taxonomic resolution, and cost. Short-read platforms like Illumina offer high accuracy and are sufficient for community-level analyses, while long-read technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore provide superior taxonomic resolution and are better suited for species-level identification and complex gene families. Sequencing depth requirements vary significantly based on the complexity of the microbial community and the specific research goals, with deeper sequencing needed for comprehensive analysis of gene families and rare taxa. By aligning platform capabilities with research objectives and following standardized experimental protocols, researchers can maximize the insights gained from microbial ecology studies.

Long-read sequencing technologies have historically been constrained by higher error rates compared to their short-read counterparts. However, recent advancements in flow cell chemistry and sophisticated basecalling algorithms are dramatically reshaping this landscape. This guide objectively compares the performance of Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) platforms, focusing on their application in microbial ecology research. Data from recent soil microbiome studies and technology evaluations demonstrate that these improvements are enabling unprecedented accuracy and resolution in profiling complex environmental samples, making long-read sequencing an increasingly powerful tool for ecologists.

For researchers in microbial ecology, accurately deciphering the immense diversity of microbial communities has been a persistent challenge, largely due to the limitations of sequencing technologies. While short-read Illumina platforms offer high base-level accuracy, their limited read length struggles to resolve complex genomic regions and often fails to provide complete genomic assemblies from metagenomic samples [5]. Long-read sequencing from ONT and PacBio overcome the length limitation but have traditionally been hampered by higher per-base error rates. This trade-off has forced researchers to choose between accuracy and context.

Recent breakthroughs are systematically dismantling this compromise. Innovations in flow cell chemistry, such as ONT's dual-reader-head R10.4.1 pore and PromethION Plus flow cells, are producing data with fundamentally higher fidelity [28] [29]. Concurrently, the development of advanced basecallers like Dorado, which leverage powerful neural networks, and specialized tools like Uncalled4 are translating raw signals into sequences with dramatically improved accuracy [30] [28]. For microbial ecologists, these advances are not incremental; they are transformative, enabling the recovery of high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from highly complex environments like soil, which was once considered the 'grand challenge' of metagenomics [5].

Breakthrough 1: Next-Generation Flow Cell Chemistry

The physical hardware of sequencing—the flow cell and its chemistry—forms the foundation of data quality. Recent updates in this domain have been targeted at increasing raw data accuracy, yield, and consistency.

The Nanopore R10.4.1 Pore and PromethION Plus

A key advancement from Oxford Nanopore is the R10.4.1 flow cell, which features a dual-reader head. Unlike the single reader of the previous R9.4.1 pore, this design captures a longer stretch of DNA nucleotides simultaneously, resulting in a more distinctive electrical signal for each k-mer (a sequence of k nucleotides). This reduces ambiguity, particularly in homopolymer regions (repeats of the same base), which were a traditional source of error for nanopore sequencing [16] [28]. The enrichment of purines and pyrimidines at specific positions within the pore's reader head creates a more predictable and interpretable signal pattern [28].

Building on this, Oxford Nanopore has announced the PromethION Plus Flow Cell, an ultra-high-output flow cell incorporating improved chemistry. Designed for high-throughput applications, it promises significantly increased data output with enhanced consistency for long fragment libraries (>15 kb), without the need for wash protocols. This is a critical development for population-scale studies in microbial ecology, as it directly reduces the cost per genome while maintaining data richness, including epigenetic information [31] [29].

Comparative Performance in Microbial Ecology

The tangible impact of these chemistry improvements is evident in direct comparative studies. A 2025 study evaluating sequencing platforms for soil microbiome profiling found that ONT (using full-length 16S rRNA sequencing) and PacBio provided comparable assessments of bacterial diversity. The study, which normalized sequencing depth across platforms, concluded that despite ONT's historically higher error rate, its latest iterations produce results that closely match PacBio's efficiency in interpreting well-represented taxa in complex soil samples [16].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Sequencing Platforms for Soil Microbiome Profiling [16]

| Platform | Chemistry/Kit | Target Region | Key Finding | Relevance to Microbial Ecology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford Nanopore | R10.4.1 Flow Cell | Full-length 16S rRNA | Results closely matched PacBio; community analysis showed clear clustering by soil type. | Enables accurate species-level identification and differentiation of microbial habitats. |

| PacBio | Sequel IIe System | Full-length 16S rRNA | Slightly higher efficiency in detecting low-abundance taxa; clear clustering by soil type. | Powerful for discovering rare members of the microbial community. |

| Illumina | MiSeq | V4 & V3-V4 regions | V3-V4 region enabled soil-type clustering; V4 region did not (p=0.79). | Limited taxonomic resolution with the V4 region can obscure ecological differences. |

Breakthrough 2: Advanced Basecalling Algorithms

Raw electrical signals from a sequencer are useless without sophisticated software to decode them. This process, known as basecalling, has become a frontier of innovation, primarily driven by machine learning.

From HAC to SUP: The Dorado Basecaller

ONT's production-grade basecaller, Dorado, offers multiple basecalling models that represent a trade-off between speed and accuracy: Fast, High Accuracy (HAC), and Super Accurate (SUP). The SUP model provides the highest raw read accuracy but requires the most computational resources [30]. These basecallers use bi-directional Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) that consider the context of the signal both before and after the current point, leading to more accurate base identification [30].

The machine learning pipeline for developing these models is rigorous. Training datasets incorporate diverse genomic samples, including the ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard, which is highly relevant for ecologists. The resulting models are validated on metrics including alignment accuracy, homopolymer sequencing, and—crucially—de novo genome assembly quality [30].

Specialized Tools and Signal Alignment with Uncalled4

Beyond generic basecallers, specialized tools are pushing the boundaries of accuracy further. Uncalled4 is a recently developed toolkit that improves the detection of nucleotide modifications via fast and accurate signal alignment [28]. Its basecaller-guided Dynamic Time Warping (bcDTW) algorithm aligns raw nanopore signals to a nucleotide reference much more efficiently than previous tools like Nanopolish or Tombo, being 1.3-2.7x faster than f5c (a GPU-accelerated tool) [28].

This accurate signal alignment is foundational for detecting DNA and RNA modifications, which can interfere with standard basecalling. By providing a more precise mapping between signal and sequence, Uncalled4 enables better modification detection, identifying 26% more RNA m6A modification sites than Nanopolish when used with the m6Anet detection tool, while maintaining equivalent precision [28].

Furthermore, for specific applications, iterative basecalling approaches have been shown to significantly improve the accuracy of reading modification-rich sequences, such as therapeutic RNAs or transfer RNAs (tRNAs). This method polishes initial basecalls by aligning them to a reference and iteratively retraining the basecaller, which has been proven to enhance mappability and alignment accuracy even for canonical RNAs [32].

Direct Comparison for Microbial Ecology Applications

The ultimate test of these technologies is their performance in real-world, complex applications like soil and sediment microbiome analysis.

MAG Recovery from Complex Terrestrial Habitats

A landmark 2025 study in Nature Microbiology demonstrated the power of deep long-read Nanopore sequencing for microbial ecology. Using a custom mmlong2 workflow featuring iterative binning on deep long-read Nanopore data (~100 Gbp per sample) from 154 soil and sediment samples, the study recovered 23,843 medium- and high-quality Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs). After dereplication, this yielded 15,314 previously undescribed microbial species, expanding the phylogenetic diversity of the prokaryotic tree of life by 8% [5]. This success was directly attributed to the long-read data, which enabled the recovery of complete ribosomal RNA operons and improved species-level classification in public databases.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for High-Throughput MAG Recovery from Soils [5]

| Protocol Step | Detailed Methodology | Purpose & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | 125 soil and 28 sediment samples from 15 distinct habitats in Denmark (Microflora Danica project). | To capture a wide breadth of microbial diversity across different terrestrial ecosystems. |

| DNA Sequencing | Deep long-read sequencing on Nanopore platform (median ~95 Gbp/sample). Library prep with ligation kits for native sequencing. | To generate sufficient data depth for assembling genomes from highly complex communities. |

| Bioinformatic Analysis (mmlong2) | 1. Assembly & Polishing: Metagenome assembly and removal of eukaryotic contigs.2. Multi-feature Binning: Differential coverage, ensemble binning, and iterative binning. 3. Dereplication: Clustering of MAGs at species level. | To maximize the number and quality of recovered prokaryotic genomes from complex metagenomic data. Iterative binning alone recovered an additional 3,349 MAGs. |

The Emerging Case for Hybrid Sequencing

While long-read technology is advancing rapidly, a hybrid approach that leverages both long and short reads can offer a superior solution. A 2025 study showed that joint processing of Illumina and Nanopore data with a hybrid DeepVariant model could match or surpass the germline variant detection accuracy of state-of-the-art single-technology methods [33]. The motivation is clear: short reads excel at detecting small variants with high precision, while long reads resolve complex regions and structural variants. By integrating both, a "shallow hybrid sequencing" approach can yield competitive performance to deep sequencing with a single technology, potentially lowering costs for large-scale studies [33]. For microbial ecologists, this hybrid strategy could be ideal for achieving both high-fidelity single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling and complete genome assembly from metagenomes.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting a sequencing strategy based on common research goals in microbial ecology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

For researchers designing experiments based on these breakthroughs, the following reagents and materials are critical.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Long-Read Sequencing [5] [16] [30]

| Item Name | Function & Application | Specific Example/Product |

|---|---|---|

| R10.4.1 Flow Cells | The core consumable for Nanopore sequencing; provides improved raw accuracy via a dual-reader-head pore. | MinION & PromethION flow cells (Oxford Nanopore). |

| PromethION Plus Flow Cells | Ultra-high-output flow cells for cost-effective, large-scale genomic and epigenomic studies. | PromethION 24 device flow cells (Oxford Nanopore). |

| Native Sequencing Kits | Library preparation kits that preserve native DNA/RNA, enabling direct detection of base modifications. | Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK114), Direct RNA Sequencing Kit (SQK-RNA004) (Oxford Nanopore). |

| Microbial Community Standards | Defined control communities used to validate sequencing protocols, basecaller training, and bioinformatic pipelines. | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard (Zymo Research). |

| High-Accuracy Basecallers | Software that converts raw electrical signals to nucleotide sequences using advanced machine learning models. | Dorado basecaller with SUP model (Oxford Nanopore). |

| Signal Alignment & Modification Detection Tools | Specialized software for aligning raw signals to a reference, crucial for accurate modification detection. | Uncalled4 toolkit (github.com/skovaka/uncalled4). |

The paradigm that long-read sequencing is inherently less accurate than short-read sequencing is no longer tenable. Breakthroughs in flow cell chemistry, such as the ONT R10.4.1 and PromethION Plus cells, have fundamentally improved the quality of raw data. Simultaneously, advanced basecallers like Dorado and specialized algorithms like Uncalled4 are leveraging machine learning to extract unprecedented accuracy and epigenetic information from this data. For microbial ecologists, the evidence is clear: these advancements are already enabling the genomic exploration of previously intractable environments, leading to a massive expansion of the known microbial tree of life [5]. While the choice between PacBio and ONT may depend on specific project needs—with PacBio sometimes showing a slight edge in detecting low-abundance taxa [16]—the overall trajectory is toward more accurate, cheaper, and more information-rich long-read sequencing, empowering researchers to finally answer fundamental questions about the vast diversity of microbial ecosystems.

From Lab to Data: Practical Protocols for 16S rRNA and Metagenomic Sequencing

Standardized DNA Extraction Protocols for Complex Environmental Samples

In microbial ecology research, the accurate characterization of community structure and function hinges on the initial and critical step of DNA extraction. The choice of DNA extraction method can significantly influence downstream sequencing results, impacting the assessment of microbial diversity, abundance, and functional potential [34]. For complex environmental samples—such as soil, feces, feed, and water—this step presents particular challenges due to the presence of inhibitory substances, varying biomass, and the structural rigidity of different microbial cells. The move towards method standardization is therefore essential for ensuring reproducibility and comparability of data, especially in large-scale or multinational ecological studies [35]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various DNA extraction protocols and their interaction with different sequencing platforms, providing a foundation for robust experimental design in microbial ecology.

DNA Extraction Method Performance: A Comparative Analysis

Key Performance Metrics for Extraction Methods

The efficiency of a DNA extraction method is evaluated based on its DNA yield, purity, and its ability to provide an unbiased representation of the microbial community. Inhibitors co-extracted from environmental matrices can also affect subsequent molecular analyses like PCR or sequencing. Furthermore, the suitability of a method may vary depending on the sample type (e.g., soil vs. water) and the target organisms (e.g., bacteria vs. viruses).

Experimental Comparison of Extraction Methods

A 2025 study on detecting African swine fever virus (ASFV) in feed and environmental samples provides a direct comparison of four DNA extraction methods: two automated magnetic bead-based methods (taco Mini and MagMAX Pathogen RNA/DNA Kit), one column-based method (PowerSoil Pro Kit), and one point-of-care system (M1 Extraction) [36]. The results, derived from quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis, are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods for ASFV Detection in Environmental Samples

| Extraction Method | Underlying Technology | Relative Performance (Cq Values) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| taco Mini | Automated Magnetic Bead-based | Best (Significantly lower Cq) | Higher sensitivity, able to detect ASFV DNA in feed mill surface samples. |

| MagMAX Pathogen | Automated Magnetic Bead-based | Best (Significantly lower Cq) | Higher sensitivity, able to detect ASFV DNA in feed mill surface samples. |

| PowerSoil Pro | Spin Column-based | Intermediate (Higher Cq) | Successfully detected ASFV DNA but with lower sensitivity. |

| M1 Extraction | Point-of-Care | Intermediate (Higher Cq) | Successfully detected ASFV DNA but with lower sensitivity. |

The study concluded that while all methods could detect the viral DNA, the magnetic bead-based extraction methods demonstrated significantly higher sensitivity (p < 0.05), as indicated by lower Cq values in qPCR. This enhanced performance was also evident in their ability to detect ASFV DNA on feed mill surface samples, where other methods struggled [36].

Another study comparing DNA extraction methods for metagenomic DNA from diverse human and environmental samples, including stool, fish gut, and soil, highlighted that while manual extraction methods can be effective for many sample types, broad-range commercial kits often provide higher purity and quality of DNA, which is crucial for sequencing [34].

The Importance of Standardization: Inter-Laboratory Ring Tests

The challenge of reproducibility across different laboratories was directly addressed in a 2025 inter-laboratory ring test for environmental DNA (eDNA) focused on marine megafauna detection [35]. Four laboratories, each using their established DNA extraction method (primarily column-based kits from Qiagen and Macherey-Nagel, albeit with lab-specific modifications), processed aliquots from the same set of eDNA samples.

Table 2: Extraction Protocols from an Inter-Laboratory Ring Test [35]

| Laboratory | Extraction Kit/Instrument | Key Protocol Modifications |

|---|---|---|

| UIBK | Qiagen BioSprint 96 Workstation | Elution with 100 µL TE buffer instead of AE buffer. |

| INRAE | Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin Tissue Kit | Added 25 µL proteinase K at lysis; heated elution buffer and performed two elutions. |

| UCC & IMR | Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit | Used a vacuum system (IMR) or specific incubation times (UCC) for spin column steps. |

The findings revealed that while total DNA concentrations were similar, there was a significant reduction in targeted qPCR performance for one laboratory, leading that lab to modify its protocol for the remainder of the project. The study also found a significant interaction between the laboratory/extraction method and the target species, indicating that no single method is universally optimal and that protocol efficiency can be taxon-dependent [35]. This underscores the necessity of cross-validation in collaborative projects.

Interaction of DNA Extraction with Sequencing Platforms

The choice of DNA extraction method is intrinsically linked to the performance of downstream sequencing technologies. The quality, fragment length, and purity of the extracted DNA can influence sequencing accuracy, read depth, and the ability to perform certain analyses like metagenomic assembly.

Comparison of Second and Third-Generation Sequencing Platforms

A comprehensive 2022 benchmarking study compared seven second and third-generation sequencing platforms using complex, synthetic microbial communities [18]. The platforms included second-generation sequencers (Illumina HiSeq 3000, MGI DNBSEQ-G400, MGI DNBSEQ-T7, ThermoFisher Ion GeneStudio S5, and Ion Proton P1) and third-generation sequencers (Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION and Pacific Biosciences Sequel II).

Key findings included:

- Read Accuracy: Second-generation platforms generally provided high base-level accuracy (>99%). Among third-generation platforms, PacBio Sequel II offered a very low substitution error rate, while ONT MinION had a lower identity rate (~89%) due to higher indel and substitution errors, though its accuracy has improved with newer chemistries [18].

- Taxonomic Profiling: All technologies showed high Spearman correlations (>0.9) between observed and theoretical genome abundances when sufficient sequencing depth was achieved. However, correlations were more affected by higher microbial richness in long-read technologies (MinION and PacBio) [18].

- Metagenomic Assembly: Third-generation sequencers, particularly PacBio, generated the most contiguous assemblies, reconstructing 36 full genomes from a 71-strain mock community, compared to 22 for MinION and fewer for short-read platforms. Hybrid assemblies, combining long and short reads, can further improve accuracy and contiguity [18].

Long-Read Sequencing for Improved Resolution

A 2025 study comparing sequencing platforms for soil microbiome profiling confirmed the advantages of long-read sequencing. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing provide superior taxonomic resolution compared to Illumina short-read sequencing of hypervariable regions (e.g., V4 or V3-V4) [16]. Full-length sequences help resolve ambiguous taxonomic assignments common with short reads. The study noted that PacBio demonstrated slightly higher efficiency in detecting low-abundance taxa, but ONT results closely matched PacBio, indicating that its inherent error rate does not preclude robust community-level analysis [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Kits

The following table lists key reagents and kits commonly used in DNA extraction from complex environmental samples, as cited in the reviewed literature.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Extraction from Environmental Samples

| Product Name/Type | Function | Example Use-Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Beads | Bind nucleic acids in the presence of a binding buffer/chaotropic salt, allowing for washing and elution; amenable to automation. | Automated pathogen detection in feed and environmental samples [36]. |

| Silica Spin Columns | Nucleic acids bind to the silica membrane in the presence of high salt, are washed, and eluted in low-salt buffer or water. | Extraction from marine eDNA filters, soil, and stool samples [35] [34]. |

| AL Lysis Buffer | A chaotropic salt-based buffer that facilitates cell lysis and denatures contaminants, promoting binding of DNA to silica. | Initial lysis step for various sample types before DNA extraction [36]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease that degrades proteins and inactivates nucleases. | Added during lysis to digest tough tissues and microbial cell walls [35]. |

| DNA/RNA Shield | A reagent that immediately stabilizes nucleic acids at the point of collection, preventing degradation. | Used to pre-moisten swabs for environmental sampling [36]. |

| Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microprep Kit | A commercial kit optimized for efficient lysis of difficult-to-lyse microbes in soil and fecal matter. | Standardized DNA extraction from soil for microbiome studies [16]. |

Decision Workflow for Method Selection and Validation

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting and validating a DNA extraction protocol for complex environmental samples, based on the insights from the comparative studies.

The journey towards fully standardized DNA extraction protocols for complex environmental samples is ongoing. Current evidence strongly indicates that magnetic bead-based automated methods offer superior sensitivity and efficiency for many applications, though column-based methods remain reliable and widely used. The choice of an extraction method must be guided by the sample type, the target of interest, and the downstream analytical application, particularly the choice of sequencing platform. Long-read sequencing technologies are overcoming earlier limitations and, when paired with high-quality DNA extracts, provide unparalleled resolution for microbial community analysis. For the scientific community, the path forward involves rigorous cross-validation of methods, as demonstrated by inter-laboratory ring tests, and a flexible, evidence-based approach to protocol selection to ensure data are both robust and comparable across studies.

In microbial ecology research, the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene serves as a gold standard marker for taxonomic identification of bacterial communities due to its presence in all prokaryotes and its combination of highly conserved and variable regions [37]. The gene contains nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) that provide the sequence diversity necessary for phylogenetic differentiation, flanked by conserved regions that enable primer binding for PCR amplification [22] [37]. Researchers face a fundamental methodological decision: whether to sequence the full-length 16S rRNA gene (~1,500 bp) using third-generation sequencing platforms or to target specific hypervariable regions (typically ~300-600 bp) using second-generation sequencing technologies [23] [38]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two approaches, supported by recent experimental data, to inform researchers in selecting the most appropriate strategy for their specific research context.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

PacBio SMRT Sequencing Protocol: Multiple studies have utilized similar methodologies for full-length 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing. The standard approach involves:

- Primer Selection: Primers 27F (AGRGTTTGATYNTGGCTCAG) and 1492R (TASGGHTACCTTGTTASGACTT) targeting the beginning and end of the 16S rRNA gene are most commonly used [22] [23].

- PCR Amplification: Typically 25-30 cycles of amplification using high-fidelity polymerases, with annealing temperatures around 55°C [22].

- Library Preparation: The SMRTbell template prep kit is used for library construction, followed by sequencing on the PacBio Sequel II system with a minimum of 5 passes and predicted accuracy ≥0.99 [22].

- Bioinformatic Processing: Circular consensus sequencing (CCS) reads are generated using SMRT Link Analysis software, followed by demultiplexing with lima v1.7.0 and primer removal with Cutadapt v1.9.1 [22].

Oxford Nanopore Technology Protocol: For nanopore-based full-length sequencing:

- Primer Design: Either standard primers (27F-I: AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG) or more degenerate variants (27F-II) can be used, with the latter showing improved coverage of diverse bacterial taxa [39] [40].

- Library Preparation: The 16S barcoding kit (SQK-RAB204) is typically employed with 50 ng of genomic DNA [39].

- Sequencing: Conducted on MinION Mk1C flow cells (R9.4.1 or newer) with real-time basecalling [40] [41].

- Optimization Considerations: Critical parameters include limiting PCR cycles (15-25) to reduce bias, selecting appropriate annealing temperatures (48-52°C), and using optimized polymerases like LongAmp Hot Start Taq [41].

Hypervariable Region-Targeted Sequencing

Illumina MiSeq Protocol: The most common approach for hypervariable region sequencing involves:

- Region Selection: Primers targeting V3-V4 (341F-805R), V1-V2 (27F-338R), or V4 (515F-806R) regions are selected based on the research application [42] [43] [44].

- PCR Amplification: Typically 25-30 cycles with region-specific annealing temperatures [43] [38].

- Library Preparation: Using kits such as the QIASeq 16S/ITS screening panel or Zymo Quick-16S Plus Library Prep methods [42] [44].

- Sequencing: Conducted on Illumina MiSeq with 2×250 bp or 2×300 bp paired-end reads [43] [23].

- Bioinformatic Processing: Denoising with DADA2 or Deblur in QIIME2 to generate amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), followed by taxonomic classification using databases like SILVA, Greengenes, or Greengenes2 [42] [43].

Table 1: Commonly Used Primer Sets for Hypervariable Region Amplification

| Target Region | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Approximate Amplicon Size | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1-V2 | 27F (AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG) | 338R (TGCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT) | ~510 bp | Skin, respiratory microbiomes [42] [43] |

| V3-V4 | 341F (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) | 805R (GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC) | ~428 bp | Gut, oral microbiomes [23] [44] |

| V4 | 515F (GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA) | 806R (GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT) | ~252 bp | General environmental samples [38] [37] |

| V5-V7 | 799F (AACMGGATTAGATACCCKG) | 1193R (ACGTCATCCCCACCTTCC) | ~394 bp | Respiratory samples [42] |

Performance Comparison: Taxonomic Resolution and Diversity Metrics

Species-Level Taxonomic Resolution

Multiple studies have demonstrated the superior species-level classification capability of full-length 16S rRNA sequencing compared to hypervariable region approaches. A 2024 study comparing PacBio full-length sequencing versus Illumina V3-V4 sequencing for human microbiome samples found that with both platforms, a similar percentage of reads was assigned to the genus level (94.79% and 95.06% respectively), but with PacBio, a significantly higher proportion of reads were further assigned to the species level (74.14% vs. 55.23%) [23]. This enhanced resolution is particularly valuable for distinguishing between highly similar species within genera such as Streptococcus or the Escherichia/Shigella group, which have minimal sequence differences in their 16S genes [23].