Predictive Modeling of Microbial Community Dynamics: From Machine Learning to Clinical and Biotechnological Applications

This article explores the transformative potential of predictive modeling for microbial community dynamics, a field critical for addressing challenges from antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to bioprocess optimization.

Predictive Modeling of Microbial Community Dynamics: From Machine Learning to Clinical and Biotechnological Applications

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of predictive modeling for microbial community dynamics, a field critical for addressing challenges from antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to bioprocess optimization. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview of foundational concepts, cutting-edge methodologies like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), and practical optimization strategies. By comparing model validation techniques and showcasing real-world applications in clinical and environmental settings, this review serves as a guide for developing robust, predictive tools to harness the power of complex microbial ecosystems for advancing human health and biotechnology.

The Why and How: Foundations of Microbial Community Prediction

The growing understanding of microbial community dynamics is driving significant scientific and commercial progress. The tables below summarize key quantitative data, highlighting market projections and public awareness metrics.

Table 1: Global Microbiomes Market Forecast and Segmentation (2025-2029)

| Metric | Value | Details/Segmentation |

|---|---|---|

| Market Growth (2025-2029) | USD 824.3 million | - |

| Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | 18.3% | - |

| Regional Contribution | North America (53%) | Key Countries: US, Canada, Germany, France, UK, Japan, China, India, South Korea, Italy |

| Product Segmentation | Probiotics, Foods, Prebiotics, Medical Food, Others | - |

| Application Segmentation | Therapeutics, Diagnostics | - |

| Key Market Trends | Collaborations for therapeutic development, AI-powered market evolution, focus on GI and metabolic disorders | - |

Table 2: Global Public Awareness of Microbiomes (2025 Survey Data)

| Awareness Metric | Result | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Heard the term "Microbiota" | 71% of respondents | +8 pts vs. 2023 |

| Know exactly what "Microbiota" means | 24% of respondents | +4 pts vs. 2023 |

| Awareness of "Dysbiosis" | 34% of respondents | No evolution since 2023 |

| Changed behavior to protect microbiota | 56% of respondents | -1 pt vs. 2024 |

| Most Trusted Information Source | Healthcare Professionals (81%) | +3 pts vs. 2024 |

Predictive Modeling of Microbial Community Dynamics

Understanding and predicting the behavior of complex microbial ecosystems is a central goal in modern microbial ecology. The following section outlines a advanced computational workflow for this purpose.

Application Note: Predicting Species-Level Abundance with Graph Neural Networks

Background: Accurately forecasting the temporal dynamics of individual microbial species in a community is a major challenge with critical applications in biotechnology and health. Traditional models often fail to capture the complex, non-linear interactions between species. A graph neural network (GNN)-based model has been developed to overcome this, using historical relative abundance data to predict future community structure [1].

Key Workflow and Findings: The model was trained and tested on individual time-series from 24 full-scale Danish wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), comprising 4709 samples collected over 3–8 years. The GNN architecture was designed to learn relational dependencies between amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). The workflow involves several critical steps: data pre-processing and clustering of ASVs, model training on moving windows of 10 consecutive samples, and prediction of 10 future time points [1]. The model demonstrated high accuracy, successfully predicting species dynamics up to 2–4 months into the future, and in some cases up to 8 months [1]. This approach, implemented as the "mc-prediction" workflow, is generic and has been successfully tested on other longitudinal datasets, including the human gut microbiome [1].

Protocol: Implementing the mc-prediction Workflow

Objective: To predict the future relative abundance of individual microbial taxa in a longitudinal dataset using a graph neural network model.

Materials:

- Software: The "mc-prediction" workflow, available at https://github.com/kasperskytte/mc-prediction [1].

- Data Input: A time-series of microbial relative abundances (e.g., from 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing), organized with samples as rows and taxonomic features (e.g., ASVs) as columns.

Procedure:

- Data Pre-processing:

- Filter the dataset to retain the top N most abundant features (e.g., top 200 ASVs) to reduce computational complexity.

- Perform a chronological split of the data into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 70%/15%/15%).

Pre-clustering of Taxa:

- Cluster the taxonomic features into smaller groups (e.g., 5 ASVs per cluster) to model local interactions efficiently.

- The original study found that clustering by graph network interaction strengths or by ranked abundances yielded the best prediction accuracy, outperforming clustering by biological function [1].

Model Training and Configuration:

- Configure the GNN model. The core architecture consists of:

- A graph convolution layer to learn and extract interaction features between microbial taxa.

- A temporal convolution layer to extract temporal features across the time-series.

- An output layer with fully connected neural networks to generate predictions.

- Train the model using moving windows of 10 consecutive historical samples from each cluster. The model's task is to predict the 10 consecutive samples following each window.

- Configure the GNN model. The core architecture consists of:

Prediction and Validation:

- Use the trained model on the held-out test dataset to generate future abundance predictions.

- Validate the model's accuracy by comparing predictions to the true historical data using metrics such as the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index, mean absolute error, and mean squared error [1].

Experimental Models for Studying Polymicrobial Communities

Many infections and natural environments harbor complex multi-species communities. This section details strategies for building and analyzing simplified model systems to study these interactions.

Application Note: Building Synthetic Microbial Communities for Antimicrobial Research

Background: Current antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) typically relies on pure cultures of a single pathogen, which fails to replicate the polymicrobial nature of many human infections. In these complex communities, interspecies interactions (e.g., metabolic cross-feeding, quorum sensing) can significantly alter a pathogen's susceptibility to antibiotics, often leading to treatment failure [2]. To address this, there is a push to develop defined synthetic microbial communities that model key aspects of in vivo environments for more relevant drug screening [2].

Key Workflow and Findings: The design of such communities often employs a bottom-up approach, adding complexity step-by-step. A prominent example is the Oligo-Mouse-Microbiota (OMM12), a consortium of 12 bacterial species that mimics the functional and compositional traits of the murine gut microbiota and provides colonization resistance against pathogens [2]. These models have revealed that microbial interactions can either increase or decrease antibiotic tolerance. For instance, Pseudomonas aeruginosa can increase Staphylococcus aureus tolerance to vancomycin, while metabolites from P. aeruginosa can paradoxically increase the potency of norfloxacin against S. aureus biofilms [2].

Protocol: Assembly and Testing of a Synthetic Skin Microbial Community (SkinCom)

Objective: To construct a defined, reproducible synthetic microbial community representing dominant human skin bacteria for studying microbe-microbe and host-microbe interactions [3].

Materials:

- Strains: Nine bacterial strains dominant on human skin (e.g., Staphylococcus epidermidis, Cutibacterium acnes, Corynebacterium species).

- Growth Media: Appropriate broths and solid agars for each strain (e.g., Brain Heart Infusion, Reinforced Clostridial Medium).

- Equipment: Automated liquid handling system, anaerobic chamber, spectrophotometer, equipment for DNA extraction.

- Reagents: DNA extraction kits, library preparation kits for shotgun metagenomic and metatranscriptomic sequencing.

Procedure:

- Individual Strain Preparation:

- Revive each of the nine bacterial strains from frozen stocks on their respective solid media.

- Inoculate liquid media and incubate under required atmospheric conditions (aerobic/anaerobic) until they reach mid-logarithmic growth phase.

- Measure the optical density (OD) of each culture and calculate growth metrics.

Community Assembly:

- Use an automated liquid handler to combine the nine strains in precise proportions based on their individual growth rates and desired starting inoculum.

- This automated process ensures high reproducibility in community construction.

Community Challenge and Sampling:

- The assembled SkinCom community can be applied to an ex vivo or in vivo model, such as an epicutaneous murine model.

- Incubate for the desired period and sample the community at multiple time points.

Downstream Multi-omics Analysis:

- Extract total DNA and RNA from community samples.

- Perform library preparation for shotgun metagenomic sequencing (for community composition) and metatranscriptomic sequencing (for community gene expression).

- Process the resulting FASTQ files through a bioinformatic pipeline for quality control, trimming, and taxonomic/functional profiling [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Microbial Community Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MiDAS 4 Database | Ecosystem-specific 16S rRNA taxonomic database | Provides high-resolution species-level classification for wastewater microbial communities [1]. |

| Synthetic Microbial Communities | Defined, reproducible model systems for studying microbial interactions | SkinCom model for skin microbiome research; OMM12 for gut microbiome studies [3] [2]. |

| Disease-Mimicking Culture Media | In vitro growth media that reflect the nutritional composition of infection sites | Synthetic Cystic Fibrosis Medium (SCFM2) for studying pathogens in CF-relevant conditions [2]. |

| Graph Neural Network Models | Machine learning for predicting multivariate time-series data | "mc-prediction" workflow for forecasting microbial community dynamics [1]. |

| Predictive Microbiology Software | Integrated platforms for modeling microbial growth and inhibition | Software combining classical models with machine learning for food safety risk assessment [4]. |

| Human Microbiome Compendium | Large, uniformly processed dataset of gut microbiome samples | Resource for identifying global patterns in microbiome composition and function [5]. |

Predicting the dynamics of complex microbial communities is a cornerstone of advancing microbial ecology and its applications in biotechnology, medicine, and environmental engineering. The inherent complexity of microbial interactions, coupled with the stochasticity of individual species' fluctuations, presents a substantial challenge to accurate forecasting. Traditional models often fail to capture the non-linear and multivariate nature of these ecosystems. However, recent breakthroughs in machine learning (ML) and deep learning are now providing the tools necessary to build predictive frameworks that can inform decision-making and process optimization. This Application Note details the specific challenges and provides structured protocols for implementing state-of-the-art graph neural network (GNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) models for microbial community forecasting, contextualized within a broader thesis on predictive modeling.

Key Challenges in Predictive Modeling

Complexity of Microbial Ecosystems

Microbial communities, such as those found in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and the human gut, consist of hundreds to thousands of interacting taxa. The structure of these communities influences critical functional outcomes, from pollutant removal efficiency to human health. Understanding the cause-effect relationships within these communities is difficult because their structure is shaped by a combination of deterministic factors (e.g., temperature, nutrients) and stochastic factors (e.g., immigration), the relative contributions of which can vary significantly [1]. This complexity makes it challenging to develop mechanistic models that accurately predict future states.

Stochasticity and Fluctuations

A major obstacle in prediction is the dynamic and often non-recurring fluctuation of individual species. As noted in a study of 24 full-scale WWTPs, "individual species can fluctuate without recurring patterns" [1]. This stochasticity is not just noise; it is a fundamental property of the system that must be distinguished from significant, signal-carrying shifts that may indicate a critical transition, such as the onset of a disease state in a host or process failure in an engineered system [6]. Reliably detecting these critical shifts requires models that can learn the bounds of "normal" temporal fluctuations.

Data Limitations and Resolution

While high-throughput 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing allows for detailed community characterization, it often results in highly discretized data due to cost constraints, leading to the loss of crucial information about continuous succession processes [7]. Furthermore, microbial data is inherently noisy and sparse, represented as matrices with dozens to hundreds of time points and hundreds of thousands of entities, requiring sophisticated computational pipelines for normalization and analysis [6].

Advanced Forecasting Approaches and Experimental Protocols

To overcome these challenges, ML models that leverage temporal dependencies and relational structures within the data have been developed. The following section outlines protocols for two such powerful approaches.

Graph Neural Network (GNN) Based Prediction

This protocol, adapted from Andersen et al., describes a method for predicting species-level abundance dynamics using only historical relative abundance data [1] [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | Provides high-resolution taxonomic data at the species level (e.g., Amplicon Sequence Variant - ASV). |

| Ecosystem-Specific Database (e.g., MiDAS 4) | Allows for high-resolution classification of ASVs into known species and functional groups [1]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Model | A machine learning architecture designed to learn interaction strengths and relational dependencies between different ASVs in a community [1]. |

mc-prediction Workflow |

A publicly available software workflow for implementing the GNN model, ensuring reproducibility and best practices [1]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Collect longitudinal samples from the ecosystem of interest (e.g., WWTP, human gut). The model in the cited study used 4709 samples collected over 3–8 years, 2–5 times per month from 24 WWTPs [1].

- Perform 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and process the sequences into ASVs.

- Classify ASVs using an ecosystem-specific taxonomic database (e.g., MiDAS 4 for wastewater) to obtain species-level relative abundances [1].

- Select the top N most abundant ASVs (e.g., top 200) for analysis, as these typically represent a majority of the biomass and system function.

Pre-clustering of ASVs:

- To maximize prediction accuracy, pre-cluster ASVs into smaller, interacting groups before model training. The study evaluated several methods [1]:

- Graph-based Clustering: Cluster ASVs based on inferred graphical network interaction strengths from the GNN model itself. This method achieved the best overall accuracy.

- Ranked Abundance: Cluster ASVs simply by ranking them by abundance and grouping in sets of five.

- Biological Function: Cluster ASVs into known functional groups (e.g., PAOs, GAOs, AOB). This method generally resulted in lower prediction accuracy.

- IDEC Algorithm: Use the Improved Deep Embedded Clustering algorithm, which can achieve high accuracy but may produce inconsistent results between clusters.

- To maximize prediction accuracy, pre-cluster ASVs into smaller, interacting groups before model training. The study evaluated several methods [1]:

Model Training and Architecture:

- Chronologically split the data from each individual site (e.g., each WWTP) into training, validation, and test sets.

- Design a GNN model for each cluster. The architecture should include [1]:

- A Graph Convolution Layer to learn and extract interaction features between ASVs.

- A Temporal Convolution Layer to extract temporal features across time.

- An Output Layer with fully connected neural networks to predict future relative abundances.

- Use moving windows of 10 consecutive historical samples as input to predict the next 10 consecutive time points.

Prediction and Validation:

- Use the trained model on the test set to generate predictions.

- Validate model accuracy by comparing predicted abundances to true historical data using metrics such as the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index, Mean Absolute Error, and Mean Squared Error.

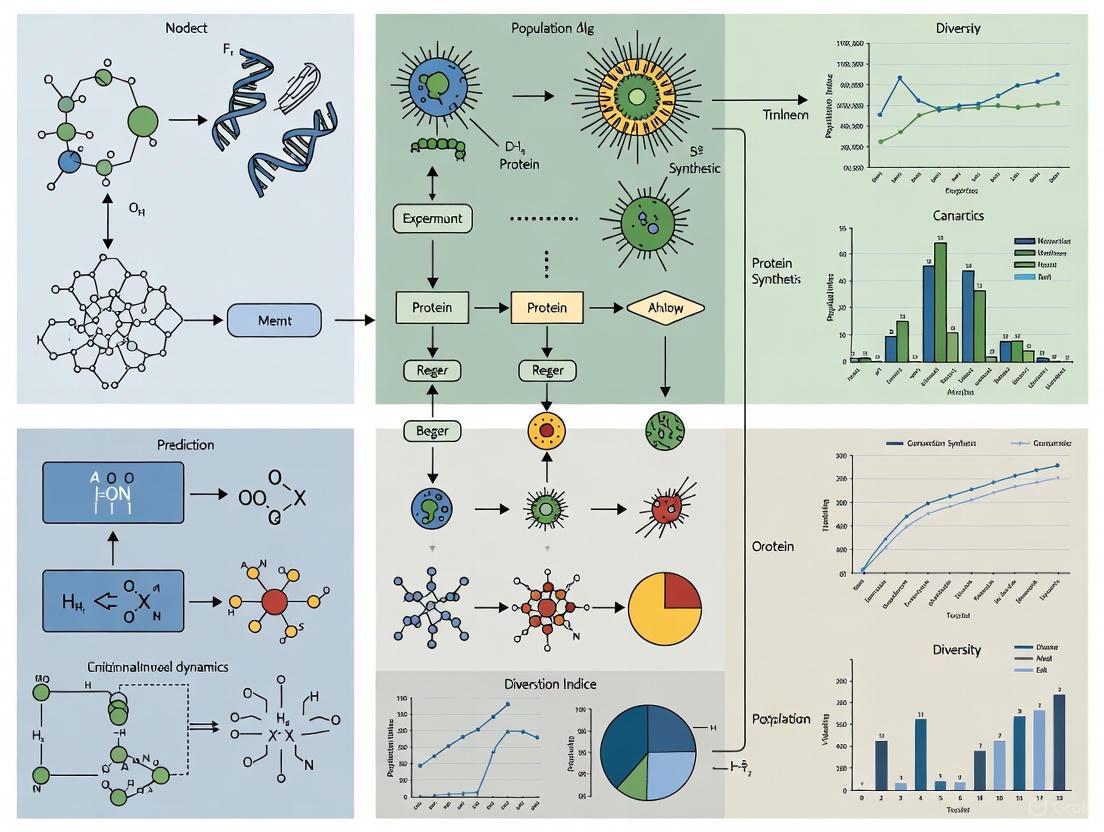

The workflow for this protocol can be visualized as follows:

LSTM-Based Forecasting for Outlier Detection

This protocol, based on the work described in, focuses on using LSTMs to model typical abundance trajectories and identify significant anomalies that may serve as early warnings for critical changes [6].

Step-by-Step Protocol

Data Compilation and Curation:

- Compile a longitudinal 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing dataset with frequent time points. Publicly available datasets from human microbiome studies or environmental monitoring (e.g., wastewater inlets) can be used.

- Address missing data points and normalize the data using established computational pipelines (e.g., RiboSnake, Natrix, Tourmaline) to handle technical noise and variability [6].

- Format data according to the BIOM standard for efficient storage and exchange.

Model Selection and Benchmarking:

- Select a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network as the primary model, as it has been shown to consistently outperform other models like Vector Autoregressive Moving-Average (VARMA) and Random Forest in predicting bacterial abundances and detecting outliers [6].

- Train the LSTM model on the time-series data for each bacterial genus. LSTMs are particularly suited for this task due to their ability to retain past information over long sequences to inform future predictions.

Prediction Interval Calculation and Outlier Detection:

- Generate prediction intervals for the abundance of each genus at each future time point.

- Identify significant changes and outliers by comparing the actual observed abundance to the model's prediction interval. A data point falling outside the interval signals a statistically significant shift that is unlikely to be part of normal fluctuations [6].

The logical flow for this analytical approach is outlined below:

Quantitative Performance and Model Comparison

The performance of advanced forecasting models has been quantitatively evaluated across multiple studies and ecosystems. The table below summarizes key metrics and findings.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Advanced Forecasting Models

| Model / Approach | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics | Prediction Horizon | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | 24 Danish WWTPs (4709 samples) | Accurate prediction of species dynamics; Best accuracy with graph-based pre-clustering. | Up to 10 time points (2-4 months), sometimes 20 points (8 months) | [1] |

| Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) | Human gut & wastewater microbiomes | Consistently outperformed VARMA and Random Forest in predicting abundances and detecting outliers. | N/S (Long-term time series) | [6] |

| Two-stage ML Model | Algae-Bacteria Granular Sludge (ABGS) | R² > 0.94 for predicting microbial community succession and pollutant removal efficiency. | N/S | [7] |

A comparison of different model architectures highlights the relative strengths of various approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of Predictive Modeling Architectures

| Model Type | Key Principle | Advantages for Microbial Data | Cited Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Learns relational dependencies between variables in a graph. | Captures complex species-species interactions. Well-suited for multivariate community data. | Achieved best overall prediction accuracy for WWTP community dynamics [1]. |

| Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) | A recurrent neural network with memory cells for long-term dependencies. | Effectively handles sequential, time-series data and retains long-term temporal patterns. | Consistently outperformed other models (VARMA, RF) in abundance prediction and outlier detection [6]. |

| Random Forest (RF) | An ensemble of decision trees. | Handles non-linear relationships; provides feature importance. | Effective but was outperformed by LSTM in a direct comparison [6]. |

| VARMA | A multivariate extension of the ARIMA model. | Models linear interdependencies between multiple time series. | Used as a baseline model; outperformed by machine learning approaches like LSTM [6]. |

Understanding the temporal patterns of microbial communities is crucial for predicting ecosystem behavior, managing human health, and optimizing biotechnological processes. Microbial communities are highly dynamic systems where species abundances fluctuate in response to environmental conditions, interspecies interactions, and stochastic events [1]. The ability to accurately predict these dynamics from relative abundance data represents a significant advancement in microbial ecology with applications ranging from wastewater treatment management to therapeutic development [1] [9]. Relative abundance data, typically derived from 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing or shotgun metagenomics, provides a compositional snapshot of microbial communities but presents unique analytical challenges due to its sparse, high-dimensional, and compositionally constrained nature [10].

Recent methodological innovations have demonstrated that temporal microbial community structure can be predicted with substantial accuracy using historical relative abundance data alone. Graph neural network-based models have successfully predicted species dynamics up to 10 time points ahead (2-4 months) in wastewater treatment plants, and sometimes up to 20 time points (8 months) into the future [1]. Similarly, the Microbial Temporal Variability Linear Mixed Model (MTV-LMM) has shown that a considerable portion of the human gut microbiome, in both infants and adults, displays temporal structure predictable from previous community composition [9]. These advancements highlight the strong autoregressive nature of microbial communities, where current composition significantly influences future states.

Analytical Frameworks for Temporal Pattern Analysis

Foundational Statistical Approaches

Traditional statistical methods for analyzing microbial time-series data have evolved to address the unique characteristics of microbiome data. The Sparse Vector Autoregression (sVAR) model identifies two dynamic regimes in microbial communities: autoregressive taxa whose abundance depends on previous community composition, and non-autoregressive taxa that appear randomly [9]. This approach has revealed that microbial community composition at a given time point is a major factor in defining future composition.

Poisson regression fit with elastic-net regularization represents another powerful approach that utilizes raw count data rather than transformed compositional data [11]. This method incorporates ARIMA (AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average) modeling to accommodate various autocorrelation structures, stationarity conditions, and seasonality in time-series data. The model structure can be represented as:

log(μ_t) = O + φ_1 x_{t-1} + ... + φ_p x_{t-p} + ... + ε_t + θ_1 ε_{t-1} + ... + θ_q ε_{t-q}

Where μ_t is the mean observation at time t, O is the offset (total read count), X is the vector of predictor variables, and φ and θ are estimated model parameters [11]. The elastic-net regularization helps manage the high dimensionality of microbiome data by penalizing both the ℓ1 and ℓ2 norms of parameter vectors, effectively selecting robust interaction models with minimal parameters.

Machine Learning and Neural Network Approaches

Modern machine learning approaches have significantly advanced predictive capabilities in microbial temporal dynamics. Graph Neural Network (GNN) models have demonstrated remarkable performance in predicting future species abundances from historical relative abundance data [1]. These models employ several specialized layers: graph convolution layers learn interaction strengths between microbial taxa, temporal convolution layers extract temporal features across time, and fully connected neural networks integrate these features to predict future relative abundances [1].

The MTV-LMM (Microbial Temporal Variability Linear Mixed Model) framework represents another sophisticated approach that leverages concepts from statistical genetics [9]. This method models temporal changes in taxon abundance as a time-homogeneous high-order Markov process, correlating similarity between microbial community composition across different time points with similarity of taxon abundance at subsequent time points. MTV-LMM simultaneously analyzes multiple hosts, increasing power to detect temporal dependencies while accounting for host-specific effects.

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Frameworks for Microbial Temporal Dynamics

| Method | Underlying Principle | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network [1] | Deep learning with graph-based relationships | Historical relative abundance time-series | Captures complex species interactions; High prediction accuracy (2-4 months ahead) | Requires substantial training data; Computationally intensive |

| MTV-LMM [9] | Linear mixed model with Markov process assumption | Longitudinal abundance data across multiple hosts | Accounts for host effects; Computationally efficient; Good for feature selection | Assumes linear dynamics; May miss nonlinear interactions |

| Poisson ARIMA with Elastic-Net [11] | Regularized regression with time-series structure | Raw count data with temporal sequencing | Handles compositional data appropriately; Robust to overfitting | Limited with highly sparse data; Requires careful parameter tuning |

| sVAR Model [9] | Sparse vector autoregression | Time-series abundance data | Identifies autoregressive vs. non-autoregressive taxa; Interpretable results | May underestimate autoregressive components |

Experimental Protocols for Temporal Pattern Analysis

Protocol 1: Graph Neural Network for Microbial Community Prediction

Principle: This protocol uses graph neural networks (GNNs) to predict future microbial community structure based solely on historical relative abundance data, without requiring environmental parameters [1].

Materials:

- Historical relative abundance data (minimum 90 samples collected over time)

- High-performance computing resources with GPU acceleration

- "mc-prediction" software workflow (https://github.com/kasperskytte/mc-prediction)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Compile amplicon sequence variant (ASV) table from 16S rRNA sequencing data. Filter to include the top 200 most abundant ASVs, which typically represent >50% of sequence reads.

- Data Splitting: Chronologically split data into training (60%), validation (20%), and test (20%) sets. Maintain temporal order to avoid data leakage.

- Pre-clustering: Cluster ASVs into groups of approximately 5 using graph network interaction strengths or ranked abundances. Avoid biological function-based clustering, which typically reduces prediction accuracy.

- Model Training:

- Input: Moving windows of 10 consecutive samples from each ASV cluster

- Architecture: Implement graph convolution layer to learn ASV interactions, temporal convolution layer to extract temporal features, and fully connected output layer

- Output: Predict relative abundances for 10 future time points

- Model Validation: Evaluate prediction accuracy using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, mean absolute error, and mean squared error metrics.

- Prediction: Apply trained model to predict future microbial community dynamics.

Technical Notes: Sampling intervals should preferably be consistent (7-14 days ideal). For WWTP datasets, models trained on 3-8 years of data with 2-5 samples per month showed best performance [1].

Protocol 2: Microbial Temporal Variability Linear Mixed Model (MTV-LMM)

Principle: MTV-LMM uses a linear mixed model framework to identify time-dependent microbes and predict future community composition based on previous microbial profiles [9].

Materials:

- Longitudinal microbiome data from multiple hosts

- Computing environment with R or Python

- MTV-LMM implementation (https://github.com/)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Organize relative abundance data into a taxa × time × host matrix. Normalize using robust methods to address compositionality.

- Quantile Binning: Transform relative abundance of non-focal taxa into quantile-binned values for input to the model.

- Model Specification: Implement the linear mixed model that correlates microbial community similarity across time points with similarity of taxon abundance at subsequent time points.

- Parameter Estimation: Optimize model parameters using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) or similar approaches.

- Time-Explainability Calculation: For each taxon, compute the fraction of temporal variance explained by previous community composition.

- Feature Selection: Identify time-dependent taxa based on time-explainability metrics.

- Prediction: Use fitted model to forecast future abundance of time-dependent taxa.

Technical Notes: MTV-LMM significantly outperforms commonly used methods for microbiome time series modeling and reveals that the autoregressive component of gut microbiome dynamics is substantially larger than previously estimated [9].

Visualization and Interpretation of Temporal Patterns

Effective visualization is essential for interpreting complex temporal patterns in microbial communities. Standard approaches include:

Ordination Plots: Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) plots visualize overall variation between sample groups over time, allowing identification of trajectories and community state transitions [12]. These are particularly valuable for visualizing how microbial communities move through multivariate space over time.

Heatmaps with Clustering: Heatmaps display relative abundance patterns across samples and time, with accompanying dendrograms showing hierarchical relationships between samples [12] [13]. These visualizations help identify co-varying taxa and community structural changes.

Line Plots of Key Taxa: Plotting abundance of specific taxa over time reveals population dynamics, seasonal patterns, and response to perturbations [14]. Adding smoothing trends helps identify underlying patterns amidst noise.

Network Diagrams: Visualizing inferred microbial interactions as networks reveals the underlying ecological relationships driving community dynamics [12]. Nodes represent taxa, and edges represent significant interactions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Temporal Microbiome Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | Amplification of target regions for sequencing | Selection of hypervariable region (V3-V4 common) affects taxonomic resolution |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of microbial genomic DNA | Mechanical lysis important for diverse cell wall types; minimize bias in representation |

| Sampling Preservation Buffers | Stabilization of microbial community at collection | RNAlater or similar buffers prevent community changes between sampling and processing |

| Sequence Indexing Adapters | Multiplexing samples for sequencing | Unique dual indexes recommended to minimize index hopping in Illumina platforms |

| Quantitative PCR Reagents | Absolute abundance assessment | Helps address compositionality issues when combined with relative abundance data |

| Graph Neural Network Frameworks | Model implementation | PyTorch Geometric or Deep Graph Library for GNN implementation [1] |

| Elastic-Net Regularization Software | Parameter estimation | GLMNet or scikit-learn for regularized regression [11] |

Workflow Diagram for Temporal Pattern Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for analyzing temporal patterns from relative abundance data:

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for analyzing temporal patterns in microbial communities

Implementation Considerations and Best Practices

Data Quality and Preprocessing

Robust temporal analysis requires careful attention to data quality and appropriate preprocessing steps. Key considerations include:

Addressing Compositional Effects: Microbial relative abundance data is inherently compositional, meaning that changes in one taxon inevitably affect the apparent abundances of others [10]. Methods like ANCOM-BC, Aldex2, and robust normalization approaches help mitigate these effects. When absolute abundance data is unavailable, assumptions about sparsity (few truly differential taxa) are often necessary for meaningful inference.

Handling Zero Inflation: Microbial datasets typically contain >70% zeros, representing either physical absence (structural zeros) or undetected presence (sampling zeros) [10]. Different statistical approaches address this challenge: over-dispersed count models (e.g., negative binomial in DESeq2) treat all zeros as sampling zeros, while zero-inflated mixture models (e.g., metagenomeSeq) account for both types. The choice depends on the biological context and taxonomic prevalence.

Batch Effect Management: Longitudinal studies are particularly vulnerable to batch effects from sequencing runs, DNA extraction kits, or personnel changes [15]. Including appropriate controls, randomizing processing order, and using statistical correction methods are essential for obtaining reliable temporal patterns.

Method Selection Guidelines

Selecting the appropriate analytical approach depends on several factors:

For High-Dimensional Prediction: Graph neural networks excel when predicting multiple taxa ahead in systems with suspected complex interactions, given sufficient data (>90 samples) [1].

For Identifying Time-Dependent Taxa: MTV-LMM is particularly effective for identifying which taxa depend on previous community composition and quantifying their "time-explainability" [9].

For Sparse Data with Clear Hypotheses: Regularized regression approaches (e.g., Poisson ARIMA with elastic-net) work well with smaller datasets and when testing specific hypotheses about interactions [11].

Reporting Standards: Adherence to standardized reporting guidelines such as STORMS (Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies) improves reproducibility and comparative analysis [15]. This includes detailed documentation of sampling procedures, DNA extraction methods, sequencing parameters, and computational workflows.

The transition from relative abundance data to temporal patterns represents a paradigm shift in microbial ecology, enabling predictive understanding of community dynamics. Methodological advances in graph neural networks, regularized regression, and linear mixed models have demonstrated that microbial communities exhibit substantial predictable temporal structure based on historical composition alone. While analytical approaches must accommodate the unique characteristics of microbiome data—including compositionality, sparsity, and high dimensionality—established protocols now enable researchers to extract meaningful temporal patterns and predict future states. As these methods continue to evolve and integrate with emerging technologies, they hold significant promise for advancing microbial forecasting in human health, environmental management, and biotechnological applications.

Predictive modeling is transforming microbial ecology from a descriptive science into a quantitative, forecast-oriented discipline. The overarching goal is to predict the dynamics of microbial communities: who is where, with whom, doing what, why, and when [16]. Achieving this predictive capability is critical for managing microbial ecosystems in contexts ranging from human health to environmental biotechnology. This Application Note defines three core predictive goals—forecasting species abundance, anticipating antimicrobial resistance (AMR) emergence, and predicting community function—and provides detailed protocols for achieving them. These goals are framed within a broader thesis on predictive modeling of microbial community dynamics, emphasizing the integration of computational models with multiscale experimental data to generate testable hypotheses and guide interventions.

Forecasting Species Abundance

Predictive Goal and Significance

Accurately forecasting the future abundance of individual microbial species is a fundamental prerequisite for managing community dynamics. In engineered ecosystems like wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), predicting the abundance of process-critical bacteria enables operators to prevent failures and optimize performance. More broadly, predicting changes in species abundance in response to environmental drivers is a cornerstone of microbial ecology [1] [17].

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Species Abundance Forecasting Models

| Model Type | Data Input | Prediction Horizon | Performance Metric & Value | Key Predictors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) [1] | Historical relative abundance (16S rRNA time-series) | Up to 20 time points (up to 8 months) | Good to very good prediction accuracy (Bray-Curtis, MAE, MSE) | Historical abundance, Graph-based interaction strengths between ASVs |

| Empirical Dynamic Modelling (EDM) [18] | Lagged time-series of species and environmental parameters | One-step ahead forecasts | RMSE <1 indicates prediction better than mean abundance | Lagged abundance of target & interacting species, Dissolved oxygen, Temperature |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: mc-prediction Workflow

I. Experimental Setup and Data Collection

- Sampling Strategy: Collect longitudinal samples from the ecosystem of interest (e.g., WWTP, host gut). For a robust model, aim for a minimum of 90-100 samples collected consistently (e.g., 2-5 times per month) over multiple years [1].

- Sequence and Preprocess: Perform 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing on all samples. Process sequences to resolve Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) and create a species (ASV) by time-point relative abundance table.

- Data Curation: Filter the ASV table to retain the top 200 most abundant ASVs, which typically capture >50% of the community biomass and are essential for model stability [1].

II. Computational Analysis using mc-prediction

- Software Installation: Install the

mc-predictionworkflow from the public GitHub repository: https://github.com/kasperskytte/mc-prediction [1]. - Data Splitting: Chronologically split the abundance table into training (first ~60-70% of time points), validation (next ~15-20%), and test (latest ~15-20%) datasets.

- Pre-clustering of ASVs: Cluster the top ASVs into small groups (~5 ASVs per cluster) to enhance model performance. The recommended methods are:

- Model Training and Prediction:

- For each cluster, train a Graph Neural Network model using moving windows of 10 consecutive historical samples as input.

- The model architecture should sequentially include:

- A graph convolution layer to learn interaction strengths between ASVs.

- A temporal convolution layer to extract temporal features.

- An output layer with fully connected neural networks to predict future abundances [1].

- Use the model to predict abundances for the next 10-20 time points.

III. Validation

- Compare predicted abundances against the held-out test dataset (true historical data) using metrics like Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Squared Error (MSE) [1].

Workflow Visualization

Predicting Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Emergence

Predictive Goal and Significance

The predictive goal is to forecast the evolution and emergence of AMR in bacterial pathogens, encompassing both genetic mutations and the acquisition of resistance genes. This is a complex, system-level phenomenon, and accurate prediction is vital for developing "evolution-proof" treatment strategies and guiding antibiotic stewardship [19] [20].

Table 2: Machine Learning Approaches for AMR Prediction

| Model Input / Type | Example Pathogens | Reported Performance | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Features (Genes, SNVs) [21] | Non-typhoidal Salmonella, Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 95% accuracy for MIC prediction (±1 dilution); Sensitivity up to 96.3% for MDR | Generalizability, Population structure confounding, Explainability |

| Quantitative Systems-Biology Models (Metabolic fitness landscapes) [19] [20] | E. coli, M. tuberculosis | Prediction of evolutionary trajectories and resistance mutations | Incorporating epistasis, nongenetic resistance, and resource competition |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Systems Biology Framework for AMR Prediction

I. Data Acquisition and Curation

- Genome Collection: Assemble a large dataset of whole-genome sequences (WGS) for the target pathogen from public databases (e.g., NARMS) or institutional sequencing efforts. Studies have used datasets ranging from ~100 to over 7,000 genomes [21].

- Phenotypic Data: Obtain corresponding, high-quality antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) profiles, preferably quantitative Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values, for each isolate.

- Feature Engineering: Annotate genomes to extract features including:

- Known AMR genes (e.g., from CARD, ResFinder).

- Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) from a pangenome analysis.

- Population structure covariates to control for confounding.

II. Model Building, Training, and Interpretation

- Model Selection: For genotype-to-phenotype prediction, employ supervised machine learning models such as Random Forests or Gradient Boosting, which can handle the high-dimensionality of genomic data [21].

- Training and Validation:

- Split data into training and test sets, ensuring that closely related strains are not split across sets to avoid over-optimistic performance.

- Use cross-validation on the training set for hyperparameter tuning.

- Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set using metrics like accuracy, precision, and area under the ROC curve.

- Model Interpretation: Use explainable AI (XAI) techniques (e.g., SHAP, feature importance) to identify the genetic drivers of resistance predictions and validate these against known biological mechanisms [21].

III. Predicting Evolutionary Trajectories

- Define Predictability and Repeatability:

- Incorporate Physiological Constraints: For a more mechanistic prediction, build models grounded in bacterial growth laws and resource allocation principles. This allows prediction of how resistance mutations impact fitness and emerge under antibiotic stress [20].

Workflow Visualization

Integrating Predictions for Community Function

Predictive Goal and Significance

The ultimate predictive goal in microbial ecology is to forecast the emergent function of an entire community, such as pollutant degradation in a bioreactor or the production of metabolites in the gut. This requires moving beyond predicting single species or traits and integrating knowledge to model the community as a system [16].

Conceptual and Technical Framework

The core challenge is that community function is an aggregate of interacting parts. The recommended approach is a nested modeling framework:

- Bottom-Up (Mechanistic) Approach: Use constrained metabolic models to predict the functional potential and interactions of individual taxa. These predictions are then integrated to simulate community-level metabolite exchange and function.

- Top-Down (Statistical) Approach: Use machine learning models to directly learn the complex, non-linear mapping between community composition data (and/or environmental parameters) and measured functional outcomes.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Linking Structure to Function

I. For Controlled Laboratory Systems (e.g., bioreactors)

- System Manipulation: Establish replicated bioreactors. Systematically vary operational parameters (e.g., temperature, substrate input) to create different environmental conditions.

- Multi-Omic Monitoring: Over time, collect samples for:

- Genomics: 16S rRNA amplicon or metagenomic sequencing to track taxonomic structure.

- Metatranscriptomics/Proteomics: To assess community-wide gene expression or protein synthesis.

- Metabolomics: To measure substrate consumption and product formation (the functional output) [16].

- Data Integration: Build integrative models (e.g., using General Linear Models or Neural Networks) that use the time-series taxonomic and -omic data as inputs to predict the functional metabolomics data.

II. For Natural or Complex Engineered Systems (e.g., WWTPs)

- Extensive Longitudinal Sampling: Collect a dense time-series of samples, as described in Section 2.3, paired with high-quality functional process measurements (e.g., nitrogen removal rates, chemical oxygen demand removal).

- Hybrid Modeling: Employ the species abundance forecasting model (Section 2.3) to first predict the future community composition. Then, use a separately trained function-prediction model that maps composition to process rates, thereby creating an end-to-end forecast of community function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Predictive Microbial Ecology

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MiDAS 4 Database [1] | Ecosystem-specific taxonomic database for high-resolution (species-level) classification of 16S rRNA sequences from WWTPs and related ecosystems. | Essential for obtaining biologically meaningful taxonomic labels from ASVs in environmental samples. |

| GeoChip [16] | A comprehensive functional gene array for high-throughput profiling of microbial community functional structure and potential activities. | Used for linking community composition to genetic functional potential in a variety of environments. |

| rEDM R Package [18] | Software package for Empirical Dynamic Modelling (EDM) and convergent cross-mapping. Used for forecasting species abundance and inferring causal interactions. | Implements multiview embedding and other EDM techniques for nonlinear time-series analysis. |

| PROBAST Tool [22] | Prediction model Risk Of Bias ASsessment Tool. A critical tool for evaluating the methodological quality and risk of bias in developed prediction models. | Should be used during model development and systematic review to ensure model robustness. |

| DeepChem Framework [23] | An open-source framework for computational biology and chemistry that integrates pre-trained Protein Language Models (PLMs). | Allows for function prediction and protein engineering tasks with reduced computational resources. |

Building the Predictive Toolbox: From Mechanistic Models to AI

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most pressing global health threats, with projections estimating millions of annual deaths by 2050 if left unaddressed [24]. Mechanistic modeling provides a powerful framework for quantitatively understanding the complex dynamics of bacterial growth, death, and resistance development. These computational approaches integrate known biological processes into mathematical formulations, enabling researchers to simulate bacterial population dynamics under various environmental conditions and antibiotic exposures. Within predictive microbial community dynamics research, mechanistic models serve as in silico laboratories for testing hypotheses about resistance emergence and evaluating potential intervention strategies before embarking on costly experimental work.

This protocol details the implementation of mechanistic models for studying AMR dynamics, with a specific focus on ordinary differential equation (ODE)-based frameworks that capture population-level behaviors and incorporate key resistance mechanisms such as chromosomal mutations and horizontal gene transfer.

Mathematical Framework for AMR Dynamics

Core Model Structure

The mechanistic model for bacterial growth under antibiotic pressure can be represented as a system of ordinary differential equations that track susceptible (S) and resistant (R) bacterial populations along with antibiotic concentration (A) dynamics [25]:

Population Dynamics Equations:

- dS/dt = αS · S · (1 - (S+R)/K) - δmax,S · (A/(A+EC50,S)) · S - μS · S + γ · R

- dR/dt = αR · R · (1 - (S+R)/K) - δmax,R · (A/(A+EC50,R)) · R + μS · S - γ · R

- dA/dt = -ke · A - (βS · S + β_R · R) · A

Parameter Definitions:

- α: Maximum growth rate (hr⁻¹)

- K: Carrying capacity (cells/mL)

- δ_max: Maximum kill rate (hr⁻¹)

- EC_50: Antibiotic concentration for half-maximal effect (μg/mL)

- μ: Mutation rate to resistance (hr⁻¹)

- γ: Reversion rate to susceptibility (hr⁻¹)

- k_e: Antibiotic clearance rate (hr⁻¹)

- β: Antibiotic uptake coefficient (mL/cell·hr)

Key Resistance Mechanisms

The model incorporates two primary resistance acquisition pathways [25]:

- Chromosomal Mutations: Represented by the transition from susceptible to resistant populations via mutation rate parameter μ

- Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT): Modeled through conjugation events that transfer resistance genes between bacterial populations

Table 1: Critical Parameters for AMR Mechanistic Modeling

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range | Units | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum growth rate | α | 0.1-15.0 | hr⁻¹ | Determines population expansion potential |

| Carrying capacity | K | 10⁷-10¹⁰ | cells/mL | Environmental limitation factor |

| Mutation rate | μ | 10⁻⁹-10⁻⁵ | hr⁻¹ | Rate of spontaneous resistance emergence |

| HGT rate | γ_HGT | 10⁻¹⁰-10⁻⁶ | mL/cell·hr | Plasmid-mediated resistance spread |

| Antibiotic kill rate | δ_max | 0.5-30.0 | hr⁻¹ | Maximum efficacy of antibiotic |

| EC_50 | EC_50 | 0.1-100.0 | μg/mL | Concentration for half-maximal effect |

Experimental Protocol: Model Parameterization and Validation

Parameter Estimation Using Continuous Culture Systems

Objective: Determine growth and kill rate parameters for specific bacterial strain-antibiotic combinations using the eVOLVER continuous culture platform [25].

Materials:

- eVOLVER continuous culture system or similar chemostat setup

- Bacterial strains of interest (e.g., Escherichia coli MG1655)

- Antibiotic stock solutions (e.g., rifampicin at 10 mg/mL in DMSO)

- Sterile growth medium appropriate for bacterial strain

- Spectrophotometer for OD600 measurements

- Colony plating equipment and materials

Procedure:

- System Setup: Calibrate eVOLVER vessels with desired media and set temperature control to 37°C with continuous mixing at 250 RPM.

- Inoculation: Dilute overnight bacterial culture to OD600 = 0.001 in fresh medium and load 15 mL into each eVOLVER vessel.

- Baseline Growth: Allow bacteria to grow without antibiotic pressure until OD600 stabilizes (typically 8-12 hours), monitoring growth every 30 minutes.

- Antibiotic Exposure: Introduce antibiotic at predetermined concentrations (e.g., 0.5×, 1×, 2×, 4× MIC) during exponential growth phase.

- Continuous Monitoring: Track OD600 every 30 minutes for 24-48 hours post-antibiotic exposure.

- Viable Counts: Sample culture (100 μL) at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours, performing serial dilutions and plating on antibiotic-free agar to determine CFU/mL.

- Resistance Screening: Plate additional samples on agar containing the test antibiotic at 4× MIC to quantify resistant subpopulations.

- Data Collection: Repeat experiment in triplicate for each antibiotic concentration.

Data Analysis:

- Growth Rate Calculation: Fit exponential phase data to N(t) = N₀·exp(α·t) to determine α.

- Kill Rate Estimation: Fit kill phase data to dN/dt = -δmax·(A/(A+EC50))·N to determine δmax and EC50.

- Mutation Rate Estimation: Use fluctuation analysis or maximum likelihood estimation from resistant colony counts.

The experimental workflow for this protocol is summarized in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: Workflow for model parameterization using continuous culture.

Model Implementation and Simulation Protocol

Computational Implementation:

- Equation Definition: Code the ODE system in Python using NumPy and SciPy

- Parameter Initialization: Load experimentally determined parameters

- Numerical Integration: Solve ODE system using

scipy.integrate.solve_ivp()with method='RK45' - Sensitivity Analysis: Perform parameter sweeps on critical parameters (α, δ_max, μ)

- Model Validation: Compare simulation output to experimental data not used for parameterization

Python Code Snippet:

Advanced Applications: Integrating Machine Learning with Mechanistic Models

Recent advances have demonstrated the power of combining mechanistic models with machine learning approaches. Graph neural networks (GNNs) can predict microbial community dynamics by learning from historical abundance data [1]. The GNN architecture processes multivariate time series data by:

- Graph Construction: Representing microbial species as nodes and their interactions as edges

- Feature Extraction: Using graph convolution layers to learn interaction strengths between species

- Temporal Processing: Applying temporal convolution layers to capture dynamic patterns

- Prediction: Generating forecasts of future species abundances through fully connected layers

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for AMR Mechanistic Modeling

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Example | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| eVOLVER Continuous Culture System | Precise control of growth conditions | High-throughput parameter estimation | [25] |

| Community Simulator Python Package | Simulation of microbial community dynamics | Modeling multi-species interactions | [26] |

| MiDAS 4 Database | Ecosystem-specific taxonomic classification | Species-level identification in WWTPs | [1] |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Models | Predicting microbial community dynamics | Forecasting species abundance | [1] |

| BARDI Framework | Holistic approach to AI in AMR research | Priority-setting for research directions | [24] |

The integration of mechanistic modeling with machine learning creates a powerful framework for AMR research, as illustrated in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Integration of mechanistic and machine learning approaches.

Case Study: Modeling Wastewater as an AMR Reservoir

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) represent significant reservoirs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, where low levels of antibiotic residues can promote resistance development [25]. Implementing the mechanistic modeling approach for WWTPs involves:

Model Adaptation:

- Additional Compartments: Include wastewater and sludge phases

- Resource Dynamics: Model carbon sources, nutrients, and multiple antibiotic residues

- Horizontal Gene Transfer: Incorporate plasmid-mediated conjugation rates

- Multi-Species Interactions: Account for community effects using the MicroCRM framework [26]

Key Findings from WWTP Modeling:

- Horizontal gene transfer, rather than chromosomal mutation, dominates resistance acquisition in wastewater environments [25]

- Synergistic interactions between antibiotic residues at low concentrations accelerate resistance development

- Microbial community structure predictions remain accurate for 2-4 months using GNN approaches [1]

Mechanistic modeling provides an essential toolset for unraveling the complex dynamics of bacterial growth, death, and resistance development. The protocols outlined here enable researchers to parameterize, implement, and validate mathematical models of AMR dynamics that can generate testable predictions and inform intervention strategies. The integration of these mechanistic approaches with emerging machine learning methods represents a promising frontier in the fight against antimicrobial resistance, particularly through frameworks like BARDI that emphasize brokered data-sharing, AI-driven modeling, rapid diagnostics, and drug discovery [24]. As these computational approaches continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly critical role in predicting microbial community dynamics and developing effective strategies to combat the global AMR threat.

The predictive modeling of microbial community dynamics represents a major challenge in microbial ecology, with significant implications for environmental biotechnology, drug development, and human health. Microbial communities are complex systems where individual species fluctuate without recurring patterns, making accurate forecasting essential for preventing system failures and guiding process optimization [27]. The advent of machine learning (ML), particularly Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), has introduced a powerful paradigm for addressing the multivariate forecasting challenges inherent in this domain. These models are uniquely suited to capture the relational dependencies and complex interplay among microbial species, physical, chemical, and biological factors that simpler models cannot adequately represent [28]. This Application Note details the implementation, performance, and protocols for applying GNNs to forecast microbial community dynamics, providing researchers and scientists with a framework for translational application.

GNN-based models have demonstrated high forecasting accuracy in predicting species-level abundance dynamics in complex microbial communities. In a comprehensive study utilizing data from 24 full-scale Danish wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs)—comprising 4,709 samples collected over 3–8 years—a GNN model accurately predicted species dynamics up to 10 time points ahead (equivalent to 2–4 months), with some cases extending to 20 time points (8 months) [27]. The approach, implemented as the "mc-prediction" workflow, has also been successfully tested on human gut microbiome datasets, confirming its suitability for any longitudinal microbial dataset [27].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of GNN Forecasting in Microbial Ecology

| Forecasting Metric | Performance Value | Conditions / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction Horizon | Up to 10 time points (2-4 months) | Standard performance; sometimes extended to 20 time points (8 months) [27] |

| Dataset Scale | 4,709 samples | Collected over 3-8 years from 24 full-scale WWTPs [27] |

| Sampling Interval | 7-14 days | 2-5 times per month [27] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) level | Highest possible resolution [27] |

| Key Performance Finding | Forecasting accuracy is closely related to interactions within ecosystem dynamics | Increasing the number of nodes does not always enhance model performance [28] |

The core strength of GNNs lies in their ability to learn interaction strengths and extract interaction features between variables (e.g., microbial species or ASVs). The model design typically consists of a graph convolution layer that learns these interaction strengths, a temporal convolution layer that extracts temporal features across time, and an output layer with fully connected neural networks that uses all features to predict the relative abundances of each variable [27]. This architecture allows the model to forecast multivariate features and define correlations among input variables, providing deep insights into the structural relationships within the microbial community [28].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The initial step involves the collection and preparation of microbial community data. For high-resolution taxonomic profiling, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing is commonly used, with ASVs classified using ecosystem-specific taxonomic databases like MiDAS 4 to provide species-level classification [27]. For studies requiring functional information and higher taxonomic resolution, shotgun metagenomics is employed, though it is more expensive and generates complex datasets [29].

Protocol: Data Preprocessing for Microbial Forecasting

- Sequence Data Processing: Process raw sequencing reads to generate a feature table quantifying ASVs, OTUs, or metagenomic species.

- Feature Selection: Filter the feature table to focus on the most abundant and relevant taxa. For instance, select the top 200 most abundant ASVs, which often represent more than half of the biomass in samples [27].

- Data Splitting: Perform a chronological 3-way split of each dataset into training, validation, and test datasets. The test dataset is used for final evaluation against true historical data [27].

- Pre-clustering (Optional): To maximize prediction accuracy, pre-cluster ASVs before model training. Methods include clustering by biological function, graph network interaction strengths, or ranked abundances. Evidence suggests that clustering based on graph network interaction strengths or ranked abundances generally yields better prediction accuracy than clustering by biological function [27].

GNN Model Architecture and Training

The GNN model is designed to handle the multivariate time series nature of microbial community data.

Protocol: GNN Model Implementation

- Input Structure: Use moving windows of consecutive samples (e.g., 10 historical consecutive samples) from multivariate clusters of ASVs as the model input [27].

- Graph Convolution Layer: This layer learns the interaction strengths and extracts interaction features among the ASVs, effectively defining a relational structure within the community [27].

- Temporal Convolution Layer: This layer extracts temporal features across the time series data, capturing patterns and trends over time [27].

- Output Layer: Employ fully connected neural networks that use all extracted features (interaction and temporal) to predict the future relative abundances of each ASV. The output is typically the next 10 consecutive samples after each input window [27].

- Model Training and Validation: Train the model iteratively on the training dataset, using the validation set for hyperparameter tuning. The model's forecasting accuracy is evaluated on the held-out test dataset using metrics such as Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Squared Error (MSE) [27].

Diagram 1: GNN forecasting workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of GNNs for microbial forecasting relies on a suite of computational and data resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for GNN-based Microbial Forecasting

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Microbial Dataset | Serves as the foundational input for training and validating the predictive model. Requires high temporal resolution. | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing or shotgun metagenomics time-series data [27] [29]. |

| Taxonomic Classification Database | Provides high-resolution, accurate classification of sequence variants to species level. | MiDAS 4 database for WWTPs; other ecosystem-specific databases for human gut, marine, etc. [27]. |

| Pre-clustering Algorithm | Groups ASVs to maximize prediction accuracy before model training. | Graph network interaction strength clustering, ranked abundance clustering, Improved Deep Embedded Clustering (IDEC) [27]. |

| GNN Software Workflow | The core computational engine for model training, testing, and prediction. | "mc-prediction" workflow (https://github.com/kasperskytte/mc-prediction) [27]. |

| Model Evaluation Metrics | Quantifies the forecasting accuracy and performance of the trained model. | Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE) [27]. |

Graph Neural Networks represent a significant advancement in the multivariate forecasting of microbial community dynamics. Their ability to model complex relational dependencies between species over time enables accurate predictions over biologically relevant horizons of weeks to months. The protocols and tools outlined herein provide a foundation for researchers in environmental microbiology, drug development, and related fields to implement these powerful models, ultimately supporting better microbial ecosystem management and translational applications.

Predictive modeling of microbial community dynamics represents a frontier in microbial ecology, enabling researchers to forecast complex biological behaviors and interactions. The ability to accurately predict future species abundances based on historical data has profound implications for managing microbial ecosystems across wastewater treatment, human health, and biotechnological applications [1]. Microbial communities function as complex adaptive systems where coherent behavior arises from networks of spatially distributed agents responding concurrently to each other's actions and their local environment [30]. Understanding these dynamics requires sophisticated mathematical approaches that can capture the nonlinear interactions and emergent properties that characterize these communities.

Data-driven approaches have emerged as powerful tools for predicting microbial dynamics without requiring complete mechanistic understanding of all underlying processes. These methods leverage historical abundance data to identify patterns and relationships that can be extrapolated into future projections. The fundamental premise is that historical relative abundance data contain sufficient information to forecast future community states, even when detailed environmental parameters or mechanistic understandings of biotic interactions are unavailable [1]. This approach has demonstrated remarkable predictive power across diverse ecosystems, from wastewater treatment plants to human gut microbiomes.

Key Methodological Frameworks

Graph Neural Network Models

Graph neural network (GNN) models represent a cutting-edge approach for predicting microbial community dynamics. These models are specifically designed for multivariate time series forecasting that considers relational dependencies between individual variables, making them well-suited for predicting complex microbial community dynamics [1]. The GNN architecture typically consists of multiple specialized layers: a graph convolution layer that learns interaction strengths and extracts interaction features among amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), a temporal convolution layer that extracts temporal features across time, and an output layer with fully connected neural networks that uses all features to predict relative abundances of each ASV [1].

In practice, these models utilize moving windows of historical consecutive samples from multivariate clusters of ASVs as inputs, with future consecutive samples after each window as outputs. This approach has demonstrated accurate prediction of species dynamics up to 10 time points ahead (approximately 2-4 months), with some systems maintaining accuracy up to 20 time points (approximately 8 months) [1]. The method has been implemented as the publicly available "mc-prediction" workflow, facilitating broader adoption and application across diverse microbial ecosystems [1].

Time-Series Decomposition and Forecasting

An alternative methodology combines singular value decomposition (SVD) with time-series algorithms to forecast microbial community dynamics. This approach decomposes gene abundance or expression data over time into temporal patterns and gene loadings, which are then clustered into fundamental signals [31]. These signals are integrated with environmental parameters to build forecasting models such as:

- Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA): Computes cyclical (seasonality), autoregressive (temporal self-dependence), differencing (difference between consecutive timepoints), and moving-average (averaging of consecutive timepoints) components of a time series [31].

- Prophet Models: Flexible models capable of modeling time-dependent evolution of ARIMA parameters [31].

- NNETAR Neural Network Models: All-purpose powerful forecasting models that can capture complex nonlinear relationships [31].

This framework has demonstrated remarkable predictive power, correctly forecasting gene abundance and expression with a coefficient of determination ≥0.87 for subsequent three-year periods in biological wastewater treatment plant communities [31].

Consumer-Resource Models

Consumer-resource (CR) models provide a mechanistic framework for predicting microbial dynamics based on resource competition. These models simulate how consumer species grow by consuming environmental resources, with dynamics described by equations that capture these relationships:

Where Xi denotes the abundance of consumer i, Yj the amount of resource j, and R_ij the consumption rate of resource j by consumer i [32]. This approach adopts a coarse-grained perspective where resources represent effective groupings of metabolites or niches, and model parameters are randomly drawn from a common statistical ensemble. This formulation generates statistics that quantitatively match those observed in experimental time series across diverse microbiotas without requiring specification of exact resource competition parameters [32].

Table 1: Comparison of Modeling Approaches for Microbial Community Prediction

| Model Type | Key Features | Data Requirements | Prediction Horizon | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network | Learns relational dependencies between species | Historical relative abundance time-series | 2-8 months | WWTPs, human gut microbiome |

| ARIMA/SVD Framework | Decomposes temporal patterns and gene loadings | Time-series multi-omics data + environmental parameters | Up to 3 years | Biological wastewater treatment |

| Consumer-Resource | Models competition for fluctuating resources | Species consumption rates, resource fluctuations | Varies with system | Human gut, saliva, vagina, mouse gut |

| Generalized Lotka-Volterra | Pair-wise species interactions | Time-series abundance data + interaction parameters | Short-term dynamics | Laboratory communities, in vitro systems |

Experimental Protocols

Microbial Community Time-Series Data Collection

Longitudinal sampling forms the foundation for data-driven prediction of microbial dynamics. The following protocol outlines standardized procedures for generating high-quality time-series data:

Sample Collection: Collect samples at consistent intervals (e.g., 2-5 times per month) over extended periods (years) to capture both short-term fluctuations and long-term trends [1]. For wastewater treatment plants, sample activated sludge from the same location each time. For human microbiomes, standardize collection time relative to host activities.

DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Perform DNA extraction using standardized kits optimized for environmental samples. For 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, target the V4 region using 515F/806R primers. For metagenomic sequencing, use Illumina platforms with minimum 5 Gb sequencing depth per sample [1] [31].

Sequence Processing and ASV Calling: Process raw sequences through standardized pipelines (DADA2 for 16S data, metaSPAdes for metagenomic assemblies). For 16S data, generate amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) rather than operational taxonomic units (OTUs) for higher taxonomic resolution [33]. Classify ASVs using ecosystem-specific taxonomic databases (e.g., MiDAS 4 for wastewater communities) [1].

Data Filtering and Normalization: Filter ASVs to include the top 200 most abundant variants (typically representing >50% of sequence reads). Normalize using relative abundance transformation or rarefaction to account for sequencing depth variation [1].

Data Partitioning: Chronologically split datasets into training (60%), validation (20%), and test (20%) sets. Maintain temporal order to avoid data leakage from future to past observations [1].

Graph Neural Network Implementation Protocol

The following protocol details the implementation of graph neural networks for microbial community prediction:

Data Preprocessing:

- Organize data into multivariate time series with dimensions [number of time points × number of ASVs]

- Apply Z-score normalization to each ASV across time points

- Structure data into sliding windows with 10 historical time points as input and 10 future points as output [1]

ASV Clustering:

- Apply graph-based clustering to group ASVs into functional clusters (typically 5 ASVs per cluster)

- Alternative clustering methods include:

- Biological function clustering (grouping by metabolic capabilities)

- Improved Deep Embedded Clustering (IDEC) algorithm

- Abundance-ranked clustering [1]

- Validate clustering effectiveness using silhouette scores

Model Architecture Specification:

- Graph Convolution Layer: Implement using ChebNet or GraphSAGE architectures to learn inter-ASV interaction strengths

- Temporal Convolution Layer: Employ 1D convolutional layers with dilation factors to capture multi-scale temporal patterns

- Output Layer: Use fully connected neural networks with softmax activation to predict relative abundances [1]

Model Training:

- Initialize model with He normal weight initialization

- Optimize using Adam optimizer with learning rate 0.001

- Implement early stopping with patience of 50 epochs based on validation loss

- Train for maximum 1000 epochs with batch size 32 [1]

Model Evaluation:

- Assess prediction accuracy using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, mean absolute error, and mean squared error

- Compare predicted vs. actual relative abundances across the test dataset

- Perform ablation studies to determine contribution of model components [1]

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Microbial Community Prediction Studies

| Research Reagent | Specifications | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen) or equivalent | Standardized microbial DNA extraction from complex samples |

| 16S rRNA Primers | 515F (5'-GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3') and 806R (5'-GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT-3') | Amplification of V4 region for bacterial/archaeal community profiling |

| Sequencing Kit | Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600-cycle) | Generate paired-end reads for amplicon or metagenomic sequencing |

| Quality Control Reagents | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit, Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit | Quantification and qualification of nucleic acids pre-sequencing |

| PCR Master Mix | Platinum Hot Start PCR Master Mix (2X) | High-fidelity amplification with minimal bias |

| Normalization Buffers | Mag-Bind TotalPure NGS Cleanup System | Normalization and purification of sequencing libraries |

Workflow Visualization

Microbial Prediction Workflow

GNN Model Architecture

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Performance Metrics and Validation

Rigorous validation is essential for assessing predictive model performance. The following metrics and approaches provide comprehensive evaluation:

Dissimilarity Measures: Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between predicted and actual community compositions provides an intuitive measure of prediction accuracy, with values closer to 0 indicating better performance [1].

Error Metrics: Calculate mean absolute error (MAE) and mean squared error (MSE) for individual ASV predictions to quantify deviation from actual values [1].

Temporal Validation: Assess how prediction accuracy decays with increasing forecast horizon. Competent models typically maintain accuracy for 2-4 months, with some systems showing predictive power up to 8 months [1].

Cluster-wise Analysis: Evaluate performance across different ASV clusters. Models typically show variable performance across functional groups, with some clusters being more predictable than others [1].

External Validation: Test model transferability by applying models trained on one system to similar but distinct ecosystems (e.g., different wastewater treatment plants) [1].

Optimization Strategies