Plasmid vs. Chromosome: Regulatory Dynamics of Gene Clusters in Bacterial Adaptation and Pathogenesis

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the regulatory mechanisms governing gene clusters on plasmids versus bacterial chromosomes.

Plasmid vs. Chromosome: Regulatory Dynamics of Gene Clusters in Bacterial Adaptation and Pathogenesis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the regulatory mechanisms governing gene clusters on plasmids versus bacterial chromosomes. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles that distinguish these genetic elements, from the mobile, accessory nature of plasmid-borne clusters to the stable, core genomic context of chromosomal ones. We delve into advanced methodologies like Hi-C and long-read sequencing for studying plasmid-host interactions, address key challenges in plasmid biology, and present comparative genomic evidence of shared and distinct regulatory strategies. Synthesizing findings from recent large-scale genomic studies, this review highlights the implications of these dual regulatory systems for the rapid dissemination of antibiotic resistance and virulence traits, offering insights for future antimicrobial strategies.

Fundamental Principles: Contrasting the Biology of Plasmid and Chromosomal Gene Clusters

The genetic blueprint of a bacterium is partitioned between its chromosome and its plasmids, a division that represents one of the most fundamental aspects of bacterial genomics and regulation. The chromosome houses the core genes essential for basic cellular processes and survival, while plasmids typically carry accessory genes that provide specialized functions for niche adaptation. This genomic separation is not merely physical but extends to gene content, regulatory mechanisms, and evolutionary behavior. Understanding the distinction between these genomic compartments is crucial for research in antimicrobial resistance, bacterial pathogenesis, and evolutionary biology, as the differential regulation of plasmid-borne versus chromosomal genes directly impacts bacterial adaptation and trait dissemination.

The functional implications of this genomic divide are profound. Plasmid-encoded genes facilitate rapid horizontal gene transfer (HGT), enabling bacterial populations to acquire complex traits such as antibiotic resistance and virulence factors in single transfer events. In contrast, chromosomal genes evolve primarily through vertical descent and point mutations, providing stable genetic foundations for cellular life. This review systematically compares these genomic elements through analysis of their structural characteristics, regulatory behaviors, and experimental approaches for their study, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for investigating bacterial genome biology and evolution.

Comparative Analysis: Fundamental Characteristics

The structural and functional differences between core chromosomal and accessory plasmid genes create a fundamental genomic landscape that governs bacterial evolution and regulation. These differences span physical properties, genetic content, inheritance patterns, and evolutionary dynamics, collectively defining how bacteria maintain essential functions while retaining adaptive potential.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Core Chromosomal and Accessory Plasmid Genes

| Feature | Core Chromosomal Genes | Accessory Plasmid Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Nucleoid region [1] | Cytoplasm, extrachromosomal [1] |

| Structure | Linear (eukaryotes) or circular (prokaryotes); part of main chromosome [1] | Circular or linear; separate from main chromosome [1] |

| Copy Number | Usually single copy per cell [1] | Multiple copies per cell possible [1] |

| Size | Larger, containing vast numbers of genes [1] | Smaller, with limited genes [1] |

| Inheritance | Vertical inheritance through cell division [1] | Horizontal gene transfer possible [1] |

| Essentiality | Essential for survival and basic functions [1] | Non-essential, accessory functions [1] |

| Replication Origin | Single origin of replication [1] | Own origin of replication [1] |

| Genetic Content | Essential cellular function genes [1] | Specialized function genes (e.g., antibiotic resistance) [1] |

| Evolutionary Role | Long-term evolutionary changes [1] | Rapid adaptation and trait sharing [1] |

The compartmentalization of genetic information creates distinct evolutionary trajectories for chromosomal versus plasmid genes. Chromosomal genes exhibit evolutionary stability with conservation of essential operons and metabolic pathways, while plasmid genes demonstrate evolutionary flexibility with high recombination rates and mosaic structures. This fundamental divide enables bacteria to maintain robust core functionalities while rapidly acquiring adaptive traits in response to environmental pressures, including antibiotics, heavy metals, and novel nutrient sources [2].

Quantitative Genomic Studies: Distribution Patterns of Antibiotic Resistance Genes

Large-scale genomic analyses have revealed distinctive patterns in how genes are distributed between chromosomal and plasmid compartments, with profound implications for the spread of antibiotic resistance. These studies employ bioinformatic approaches on thousands of bacterial genomes to identify the mobilization patterns of clinically significant genes and the factors influencing their transferability.

Table 2: Distribution of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Enterobacteriaceae Genomes

| Gene Category | Prevalence in Chromosomes | Prevalence in Plasmids | Transferability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accessory Chromosomal ABR Genes | <10% of chromosomes [3] | Higher abundance [3] | High [3] |

| Core Chromosomal ABR Genes | ≥90% of chromosomes [3] | Lower abundance [3] | Low [3] |

| Shared ABR Genes | 33% of all ABR genes [3] | 33% of all ABR genes [3] | Evidence of LGT [3] |

Analysis of 2,635 Enterobacteriaceae isolates revealed that 33% of the 416 identified antibiotic resistance (ABR) genes are shared between chromosomes and plasmids, with phylogenetic reconstruction supporting their evolution through lateral gene transfer [3]. This gene sharing creates a dynamic genetic pool where resistance traits can transition between chromosomal and plasmid locations based on selective pressures. The functional complexity of the resistance mechanism appears to be an important determinant of transferability, with less complex biochemical resistance mechanisms (e.g., drug inactivation) more readily transferring between genomic compartments compared to complex multi-component systems (e.g., efflux pumps) [3].

Network analyses of over 10,000 bacterial plasmids have further elucidated the population structure of plasmid-borne genes, revealing that plasmids form distinct cliques based on shared k-mer content that correlate with gene content, host range, and GC content [2]. This large-scale analysis demonstrated that transposable elements serve as the main drivers of HGT at broad phylogenetic scales, facilitating the movement of ABR genes between different plasmid backbones and bacterial hosts [2]. The mosaic structure of plasmids enables the accumulation of multiple resistance genes on single transferable elements, creating multidrug-resistant plasmids that can rapidly disseminate resistance across bacterial populations.

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Genomic Analysis Protocols

Comprehensive genomic analysis provides insights into the distribution and transfer patterns of genes between chromosomal and plasmid compartments. The following methodology, derived from large-scale genomic studies, allows researchers to characterize the genomic landscape of bacterial isolates:

Genome Assembly and Annotation: Isolate high-quality DNA and perform both short-read (Illumina) and long-read (Nanopore) sequencing. Assemble reads using hybrid assembly approaches with tools like Unicycler, followed by annotation using Prokka with custom databases for comprehensive gene identification [4].

Replicon Classification: Use tools such as PlasmidFinder and MOB-suite to classify replicon types and mobility groups, distinguishing chromosomal from plasmid sequences based on replication and partitioning systems [2].

ABR Gene Identification: Annotate antibiotic resistance genes using the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) with the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) tool, applying thresholds of ≥70% protein identity and ≥90% coverage to identify homologs [3] [4].

Phylogenetic Reconstruction: For genes present on both chromosomes and plasmids, perform multiple sequence alignment using MAFFT and reconstruct phylogenetic trees with IQ-TREE under appropriate substitution models (e.g., LG or LG4X) to infer evolutionary relationships and lateral transfer events [3].

Comparative Genomic Analysis: Identify genomic islands and plasmid transfer regions using tools like Treasure Island and perform whole-genome alignments with ProgressiveMauve to identify structural variations and horizontal transfer events [4].

This integrated genomic approach enables researchers to track the movement of genes between chromosomal and plasmid compartments across bacterial populations and identify key drivers of antimicrobial resistance dissemination.

Plasmid Transformation Assays

Experimental studies of plasmid transfer mechanisms provide critical insights into how accessory genes move between bacterial cells. The following transformation assay methodology evaluates the efficiency of plasmid uptake under different environmental conditions:

Microcosm Setup: Prepare either Single Species Microcosms (SSM) using specific E. coli strains or Bacterial Consortium Microcosms (BCM) using environmental isolates to simulate natural conditions. Expose microcosms to different transformation-enhancing treatments including soil, CaCl₂ solution, cell-free extracts, and plastic debris [5].

Plasmid Selection: Utilize well-characterized plasmids such as pACYC:Hyg (5433 bp, carrying chloramphenicol and hygromycin resistance genes) or pBAV-1k for transformation experiments. These plasmids should contain selectable markers for detecting successful transformation events [5].

Transformation Conditions: Incubate plasmids with bacterial cells under different environmental conditions, with particular attention to plastic polymers that have been shown to significantly enhance transformation efficiency compared to other conditions [5].

Selection and Validation: Plate transformation mixtures on selective media containing appropriate antibiotics. Confirm transformation success through colony PCR and plasmid extraction, then sequence validated transformations to confirm plasmid integrity [5].

This experimental approach demonstrates that environmental factors, particularly plastic debris, can significantly enhance natural transformation frequencies, facilitating the spread of plasmid-encoded antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial populations [5].

Regulatory Coordination: Core and Accessory Gene Integration

The functional efficacy of plasmid-encoded accessory genes depends on their successful integration with core chromosomal regulatory networks. Research on multipartite genomes in bacteria like Sinorhizobium fredii has revealed that successful bacterial strains exhibit coordinated regulation between core chromosomal genes and accessory plasmid genes during niche adaptation [6]. Transcriptomic analyses demonstrate that core genes show higher average expression levels and greater connectivity in co-expression networks compared to accessory genes, reflecting their fundamental cellular roles [6].

This regulatory integration occurs despite significant organizational differences between genomic compartments. Chromids (secondary chromosomes with plasmid-like maintenance) show proportionally more genes co-expressed with primary chromosomes compared to plasmids, suggesting an intermediate role in regulatory integration [6]. However, key adaptive genes on plasmids, such as nitrogen fixation genes on symbiosis plasmids in rhizobia, exhibit high connectivity in both within- and between-replicon co-expression analyses, indicating their successful integration into core regulatory networks [6]. This integration enables bacteria to deploy accessory functions in a coordinated manner while maintaining essential cellular homeostasis.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) studies further illuminate the integration between chromosomal and plasmid-encoded components. Surprisingly, plasmid-encoded proteins exhibit more protein-protein interactions than chromosomal proteins, counter to the traditional hypothesis that highly mobile genes should have fewer molecular interactions to facilitate horizontal transfer [7]. However, topological analysis reveals that plasmid-encoded proteins have limited overall impact on global PPI network structure, with plasmid-related PPIs constituting only 0.136% of all interactions [7]. This suggests that while plasmid-encoded proteins can integrate with host networks, the core chromosomal proteins maintain the fundamental architecture of cellular interactomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Databases

Investigating the genomic landscape of core chromosomal and accessory plasmid genes requires specialized bioinformatic tools and experimental reagents. The following table compiles essential resources for researchers in this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Chromosomal and Plasmid Gene Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Prokka | Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation [3] [4] | Genome annotation for chromosomal and plasmid genes |

| CARD/RGI | Antibiotic resistance gene identification [3] [4] | Detection of ABR genes in both chromosomes and plasmids |

| PlasmidFinder | Plasmid replicon typing [4] [2] | Classification of plasmid incompatibility groups |

| MOB-suite | Plasmid mobility classification [2] | Prediction of conjugation potential |

| STRINGdb | Protein-protein interaction data [7] | Analysis of chromosomal-plasmid protein interactions |

| Unicycler | Hybrid genome assembly [4] | Complete assembly of both chromosomal and plasmid sequences |

| IQ-TREE | Phylogenetic reconstruction [3] | Evolutionary analysis of gene transfer events |

| pACYC:Hyg | Model plasmid for transformation assays [5] | Experimental studies of plasmid transfer efficiency |

These resources enable comprehensive analysis of the complex interactions between chromosomal and plasmid compartments, facilitating research into horizontal gene transfer, antibiotic resistance dissemination, and bacterial genome evolution. The integration of multiple tools is often necessary to fully characterize the dynamic nature of bacterial genomes and their role in adaptation and pathogenesis.

The distinction between core chromosomal and accessory plasmid genes represents a fundamental paradigm in bacterial genomics with profound implications for antimicrobial resistance and bacterial evolution. The physical and functional separation of these genetic compartments creates a dual evolutionary strategy: chromosomal genes provide evolutionary stability through conserved essential functions, while plasmid genes enable evolutionary flexibility through horizontal transfer and rapid adaptation. This genomic architecture facilitates the global spread of antimicrobial resistance, as evidenced by the widespread distribution of ABR genes across chromosomal and plasmid compartments in clinical isolates [3] [8].

Understanding the regulatory coordination between these genomic compartments provides crucial insights for addressing the antimicrobial resistance crisis. Future research should focus on elucidating the molecular mechanisms that facilitate the successful integration of transferred plasmid genes into host regulatory networks, as this process enables the stable acquisition of new traits including antibiotic resistance. Additionally, investigating how environmental factors such as plastic pollution enhance gene transfer [5] may inform strategies to mitigate the spread of resistance genes in natural and clinical environments. The continued development of computational tools and experimental approaches will further illuminate this complex genomic landscape, potentially identifying novel targets for disrupting the dissemination of virulence and resistance genes while preserving the adaptive potential of beneficial microorganisms.

The regulatory and functional dichotomy between plasmid-borne and chromosomally encoded genes is a cornerstone of bacterial evolution and adaptation. Plasmids, as autonomously replicating DNA elements, are fundamental drivers of horizontal gene transfer, disseminating traits that enable rapid bacterial responses to environmental pressures. While chromosomes typically encode core housekeeping functions, plasmids often carry accessory genes—including those for secondary metabolites, antibiotic resistance, and virulence—that provide conditional advantages. Understanding the nuanced differences in how these genetic elements are regulated, expressed, and maintained is critical for foundational microbiology and applied drug development. This guide objectively compares the content and functional governance of plasmid-borne versus chromosomal gene clusters, synthesizing current research to elucidate their distinct biological and evolutionary logic.

Comparative Analysis of Genetic Content and Regulation

Quantitative Comparison of Gene Content and Properties

The table below summarizes key differences in the content and properties of plasmid-borne and chromosomal genes, based on large-scale genomic studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Plasmid-Borne and Chromosomal Gene Properties

| Feature | Plasmid-Borne Genes | Chromosomal Genes | Supporting Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representative Functions | Antibiotic resistance, anti-defence systems, virulence factors, toxin-antitoxin systems | Core metabolism, DNA replication, transcription, translation | [9] [10] [11] |

| Anti-Defence System Enrichment | Highly enriched in the leading region of conjugative plasmids (hotspot for anti-CRISPR, anti-restriction, SOS inhibitors) | Not typically enriched for dedicated anti-defence functions | [11] |

| Protein Interaction Network Connectivity | Have more protein-protein interactions (PPIs) on average | Have fewer PPIs on average | [10] |

| Impact on PPI Network | Limited overall impact on host PPI network structure in >96% of samples | Form the stable core of the host PPI network | [10] |

| Presence in Bacterial Genome | ~0.65% of the total number of genes per bacterial sample | Constitutes the majority of the bacterial genome | [10] |

Distinct Regulatory Logic and Lifestyles

The fundamental differences in mobility and evolutionary trajectory between plasmids and chromosomes have given rise to distinct regulatory paradigms.

Plasmid Regulatory Strategies: Host Manipulation and Defence Evasion

A key regulatory strategy employed by plasmids is the encoding of homologs of host regulatory proteins to rewire bacterial gene expression for plasmid benefit. A landmark study identified a plasmid-encoded global translational regulator, RsmQ, on the plasmid pQBR103 in Pseudomonas fluorescens [12]. RsmQ interacts directly with host mRNAs, causing large-scale proteomic changes that alter bacterial metabolism and trigger a lifestyle switch from motile to sessile, thereby promoting plasmid transmission [12].

Conjugative plasmids also exhibit a strategic enrichment of anti-defence systems in the "leading region," the first segment of DNA to enter a new host cell during conjugation [11]. This region acts as an "anti-defence island," encoding proteins such as anti-CRISPRs, anti-restriction proteins (e.g., ArdA), SOS inhibitors (e.g., PsiB), and orphan DNA-methyltransferases. This localization ensures rapid protection against host defences, facilitating successful plasmid establishment [11].

Chromosomal Regulation: Coordination and Dosage Balance

In contrast, chromosomal gene regulation often prioritizes coordinated expression and dosage balance, particularly for genes encoding subunits of macromolecular complexes. Chromosomes achieve coexpression through several strategies, including operons, bidirectional promoters, and the clustering of functionally related genes [13] [14]. This organization minimizes expression variability and ensures the correct stoichiometry of protein complexes, which is critical for efficient cellular function [14].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Representative Regulatory Systems

| Regulatory Feature | Plasmid-Mediated Example | Chromosomal Example | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Regulator Homolog | RsmQ translational regulator | Chromosomal RsmA/CsrA proteins | Plasmid subverts host network for its own benefit [12] |

| Anti-Defence Localization | Leading region hotspot | Not applicable | Plasmid ensures survival in new host [11] |

| Gene Organization | Accessory gene arrays | Operons, gene clusters, TADs | Chromosome optimizes core function coordination [13] |

| Context-Sensitive Expression | Promoter sensitivity to supercoiling | Stable chromosomal context | Plasmid expression more responsive to host physiology [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Investigating Plasmid-Host Crosstalk via a Plasmid-Encoded Translational Regulator

This protocol is based on research characterizing the RsmQ protein from plasmid pQBR103 [12].

- Objective: To determine how a plasmid-encoded regulatory homologue globally alters the host's transcriptome and proteome, and consequent phenotypic outcomes.

- Materials:

- Bacterial strains: Isogenic Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 with and without pQBR103 plasmid; rsmQ knockout mutant.

- Growth media appropriate for the bacterial strain.

- RNA extraction kit and equipment for RNA-Seq library preparation and sequencing.

- Equipment for proteomic sample preparation and mass spectrometry.

- Motility agar plates (swimming and swarming).

- Conjugation assay materials (filters, mating media).

- Methodology:

- Comparative Omics: Grow the wild-type plasmid-carrying strain, a plasmid-free strain, and an rsmQ knockout mutant in biological triplicates to mid-exponential phase.

- Harvest cells for simultaneous RNA and protein extraction.

- Perform RNA-Seq to profile the transcriptome and mass spectrometry-based proteomics to profile the proteome.

- Biochemical Characterization:

- Perform RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) or Cross-linking Immunoprecipitation (CLIP) using a tagged RsmQ protein to identify direct mRNA targets.

- Use synthesized single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) motifs for Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSAs) to confirm direct binding of RsmQ to specific sequences.

- Phenotypic Assays:

- Motility: Perform swimming and swarming assays on semi-solid and soft agar plates, respectively.

- Conjugation Rate: Conduct filter mating assays to measure the conjugation frequency of the plasmid from different genetic backgrounds.

- Metabolic Profiling: Utilize Biolog plates or similar phenotyping arrays to assess carbon source utilization differences.

- Expected Outcome: The plasmid-encoded RsmQ will cause significant changes in the host proteome without proportionate changes in the transcriptome, directly bind to host mRNAs, and induce a switch from a motile to a sessile lifestyle, thereby increasing plasmid conjugation rates.

Protocol 2: Profiling Anti-Defence Systems in Plasmid Leading Regions

This protocol is based on the computational and experimental validation of anti-defence islands [11].

- Objective: To identify and characterize anti-defence genes enriched in the leading region of conjugative plasmids.

- Materials:

- Data: Public genomic and metagenomic assemblies (e.g., from NCBI, EBI).

- Software: Profile hidden Markov model (pHMM) databases for known anti-defence genes (anti-CRISPRs, anti-restriction, SOS inhibitors), oriT prediction tools, and genome annotation pipelines.

- Strains: Conjugative plasmids with and without candidate leading region anti-defence genes; recipient strains with active defence systems (e.g., specific CRISPR-Cas or restriction systems).

- Methodology:

- Computational Identification:

- Extract all sequences annotated as plasmids or contigs containing relaxase/traM genes.

- Identify the origin of transfer (oriT) adjacent to the relaxase gene to define the leading and lagging regions.

- Scan all open reading frames (ORFs) for homology to known anti-defence genes using pHMMs.

- Calculate the relative abundance and position of anti-defence genes relative to the oriT. Statistically test for enrichment in the leading region.

- Experimental Validation:

- Gene Clustering: Cluster enriched genes from the leading region to identify novel gene families.

- Conjugation Assay: Construct plasmid variants where a candidate anti-defence gene is deleted or moved to the lagging region.

- Measure conjugation efficiency of these variants into recipient strains with relevant active defence systems (e.g., a specific CRISPR-Cas spacer or a restriction system).

- Computational Identification:

- Expected Outcome: A significant enrichment of anti-defence genes will be found in the first ~30 ORFs of the leading region. Plasmid variants with deleted or relocated anti-defence genes will show reduced conjugation efficiency into hosts with the corresponding defence system, confirming their functional importance.

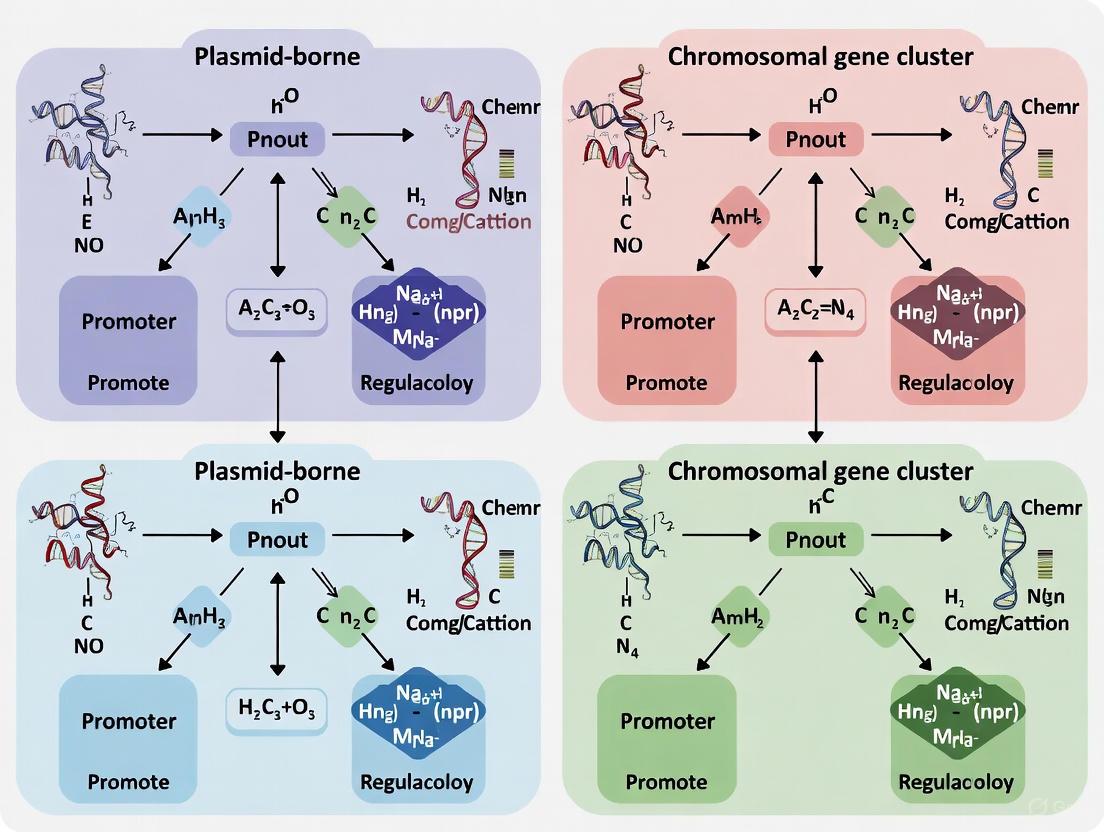

The following diagram illustrates the logic and workflow for profiling anti-defence systems in plasmids.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and methodologies essential for conducting research in plasmid biology and gene regulation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies for Plasmid vs. Chromosome Studies

| Research Reagent / Method | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-Seq & Proteomics (MS) | Global profiling of transcriptome and proteome | Identifying discordance between mRNA and protein levels upon plasmid RsmQ expression [12] |

| CLIP/RIP-Seq | Identifies direct RNA-protein interactions | Mapping direct mRNA targets of plasmid-encoded translational regulators like RsmQ [12] |

| Profile HMM (pHMM) | Computational identification of protein families based on sequence homology | Discovering anti-defence genes (anti-CRISPR, anti-restriction) in plasmid leading regions [11] |

| Filter Mating Conjugation Assay | Measures plasmid transfer frequency between donor and recipient cells | Testing the functional impact of leading region anti-defence genes on plasmid establishment [11] |

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks | Maps physical interactions between proteins within a cell | Comparing connectivity and centrality of plasmid-encoded vs. chromosomal proteins [10] |

| Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH) | Compares gene presence/absence across strains | Linking plasmid vs. chromosomal gene carriage to metabolic differences and epidemiology [16] |

The comparative analysis of plasmid-borne and chromosomal genetic elements reveals a fundamental biological division of labor: chromosomes provide stability and coordinated regulation for core cellular functions, while plasmids serve as nimble, adaptive vehicles for niche-specific traits. The regulatory interference caused by plasmids, through mechanisms like RsmQ, demonstrates that their impact extends beyond simple gene addition to active reconfiguration of host physiology. For drug development, this paradigm is critical. Understanding that antibiotic resistance genes on plasmids are often coupled with anti-defence systems and are subject to distinct, context-sensitive regulation compared to their chromosomal counterparts suggests the need for novel strategies. Future therapeutic approaches could target plasmid-specific maintenance, transfer, or anti-defence functions to disarm pathogens without applying direct selective pressure that drives chromosomal evolution. The distinct rules governing these two genomic compartments offer a richer, more nuanced target for combating the spread of antibiotic resistance and virulence.

In molecular biology and biotechnology, the control of gene expression is a foundational pillar. Achieving predictable and robust output is critical for applications ranging from recombinant protein production to advanced cell and gene therapies. A central question in this endeavor is the choice of genetic location: should a gene of interest be placed on an extrachromosomal plasmid or stably integrated into the host's chromosome? This guide objectively compares the performance of plasmid-based versus chromosome-based gene expression systems, drawing on recent experimental data to delineate their distinct advantages, limitations, and regulatory behaviors.

The core of this comparison lies in the fundamental regulatory independence of plasmids from the host chromosome. This independence influences every aspect of genetic control, from gene copy number and expression stability to the metabolic burden on the host cell. The following sections provide a detailed, data-driven comparison of these two engineering strategies, summarizing key performance metrics, explaining foundational experimental protocols, and visualizing the logical relationships that govern their function.

Performance Comparison: Plasmid vs. Chromosomal Gene Expression

Direct comparative studies and platform-specific investigations reveal consistent differences in the performance of plasmid-based and chromosomal gene expression systems. The tables below summarize key quantitative findings.

Table 1: Direct Comparative Performance of Plasmid vs. Chromosomal Systems

| Performance Metric | Plasmid-Based System | Chromosome-Based System | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| BGLS Production Yield | 0.07 μmol/L [17] | 0.59 μmol/L (8.4-fold higher) [17] | S. cerevisiae benzylglucosinolate pathway [17] |

| Expression Level Variability | High cell-to-cell variation; wide standard deviation in copy number [18] | More stable and consistent gene expression [17] | Single-cell measurements in E. coli [18] |

| Basal (Leaky) Expression | Significant leaky activity without induction [19] | Tightly regulated; no detectable phenotype without induction [19] | CRISPRi repression in L. lactis [19] |

| dCas9-sfGFP Expression Level | High (reference level) [19] | ~20-fold lower than plasmid [19] | Chromosomal integration at pseudo29 locus in L. lactis [19] |

Table 2: Characteristics of Plasmid and Chromosomal Systems

| System Characteristic | Plasmid-Based System | Chromosome-Based System |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Copy Number | Varies by origin: pSC101 (~4), p15A (~9), pColE1 (~18), pUC (~61) [18] | Single copy (by design) [17] |

| Genetic Stability | Prone to segregational loss without selection [18] | Highly stable; mitotically inherited [17] |

| Metabolic Burden | Higher, due to replication and high gene dosage [17] | Generally lower [17] |

| Engineering Speed | Fast; simple transformation [20] | Slower; requires integration [19] |

| Tunability of Expression | Often modulated by copy number and inducible promoters [20] | Relies on promoter strength and genomic context [21] |

Experimental Insights and Methodologies

Direct Comparison of Metabolic Pathway Production

A seminal study directly engineered the same seven-gene pathway for benzylglucosinolate (BGLS) production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using both stable genome integration and high-copy plasmid introduction [17].

- Experimental Protocol: The eight required genes (seven biosynthetic genes plus ATR1) were introduced into the yeast strain CEN.PK 113-11C. For the genome-engineered strain (BGLSg), the genes were pairwise integrated into four well-characterized sites on chromosome XII using strong constitutive promoters (TEF1 or PGK1). For the plasmid-engineered strain (BGLSp), the same genes and promoters were placed on two 2μ-derived high-copy plasmids [17].

- Key Findings: Despite the plasmid system showing a tendency for higher expression levels for most individual pathway enzymes, the genome-engineered strain produced 8.4-fold higher BGLS yield. The plasmid system also showed large variations in protein levels and production yields across biological replicates, indicating poor orchestration of the pathway. In contrast, the single-copy genome integration resulted in more stable and balanced expression, leading to superior performance [17].

Controlling Unwanted Expression in CRISPRi Systems

The problem of leaky expression is clearly demonstrated in the development of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) platforms in Lactococcus lactis [19].

- Experimental Protocol: Researchers placed a nisin-inducible dCas9-sfGFP gene on either a plasmid or the chromosome. A constitutively expressed sgRNA targeted the acmA gene, whose repression causes a distinct long-chain cellular phenotype. Phenotype and fluorescence were observed with and without the nisin inducer [19].

- Key Findings: The plasmid-based system showed leaky repression, resulting in the long-chain phenotype even without induction, due to basal dCas9 expression. In contrast, the chromosome-based system showed no detectable phenotype without induction and required induction for repression. Chromosomal integration reduced dCas9 expression levels by approximately 20-fold, ensuring tight regulation and eliminating background activity [19].

Single-Cell Dynamics of Plasmid Copy Number

The inherent variability of plasmid systems was quantified using a sophisticated method to count plasmid DNA and RNA transcripts in single living E. coli cells [18].

- Experimental Protocol: The target plasmid was engineered with an array of 14 operator repeats. A second plasmid expressed a PhlF repressor protein fused to red fluorescent protein (RFP). When bound to the operator array, each plasmid spot fluoresced, allowing copy number quantification via fluorescence microscopy. This was combined with PP7-based systems for counting mRNA transcripts [18].

- Key Findings: Plasmid copy number distributions across a population were extremely wide, with standard deviations on the order of the mean. For example, the p15A origin had a mean of 9 copies per cell, but a significant fraction of cells had far fewer or more. This fundamental heterogeneity in gene dosage directly contributes to cell-to-cell variation in gene expression, a problem largely avoided by single-copy chromosomal integrations [18].

Visualizing Regulatory Independence and Workflows

The diagrams below illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows that differentiate plasmid and chromosomal gene regulation.

Regulatory Independence of Plasmid and Chromosomal Systems

Experimental Workflow for Direct Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting comparative studies of plasmid and chromosomal gene expression.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Expression Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Copy Plasmid Backbones | Provide high gene dosage for expression. Origins include pUC (500-700 copies), pColE1 (15-20 copies), p15A (10-12 copies) [18]. | Driving high-level protein expression when precise regulation is not critical [20]. |

| Low-Copy/Integrative Vectors | Maintain low, stable copy number or facilitate genomic integration. Origins include pSC101 (~5 copies) [18]. | Stable expression with minimal metabolic burden; essential gene study [19]. |

| Constitutive Promoters | Drive constant gene expression. Examples: TEF1 (yeast), PGK1 (yeast), J23105 (bacteria) [17] [22]. | Provides consistent transcriptional drive in comparative studies [17]. |

| Inducible Promoters | Allow external control of gene expression. Examples: Nisin-inducible (PnisA), Tetracycline-responsive (TRE), Arabinose-inducible (araBAD) [19] [20]. | Studying essential genes; testing dose-response; minimizing leaky expression [19]. |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Enable quantification of gene expression and localization. Examples: sfGFP, mScarlet-I, RFP, CFP [18] [22]. | Single-cell expression analysis; measuring cell-to-cell variation; promoter activity assays [18]. |

| DNA-Binding Protein Fusions | Label specific DNA loci in live cells. Example: PhlF-RFP [18]. | Visualizing and counting plasmid copies in single cells [18]. |

| RNA-Binding Protein Fusions | Label specific RNA transcripts in live cells. Example: PP7-CFP [18]. | Visualizing and counting mRNA transcripts in single cells [18]. |

The choice between plasmid and chromosomal gene expression systems is not a matter of which is universally superior, but which is optimal for a specific application. Plasmid-based systems offer speed, flexibility, and high potential output, making them ideal for small-scale protein production, transient transfections, and initial proof-of-concept experiments. However, their inherent variability, metabolic burden, and issues with leaky expression can be significant liabilities.

In contrast, chromosome-based systems provide superior stability, predictable and tunable expression, and minimal cell-to-cell variation. These attributes are indispensable for large-scale industrial bioprocesses, advanced synthetic biology circuits requiring precise logic, and therapeutic applications where safety and consistent dosing are paramount. As the field advances, the strategic integration of both platforms—using plasmids for rapid prototyping and chromosomes for stable production—will continue to drive progress in genetic engineering and drug development.

The dissemination of gene clusters is a fundamental process driving microbial evolution and adaptation, occurring primarily through two distinct mechanisms: horizontal gene transfer and vertical inheritance. Horizontal gene transfer enables the rapid acquisition of new traits, such as antimicrobial resistance and virulence factors, across diverse taxonomic boundaries [23]. In contrast, vertical inheritance ensures the faithful transmission of genetic information from parent to offspring, preserving core genomic functions across generations [24]. The strategic comparison of these dissemination pathways provides crucial insights for understanding bacterial evolution, with significant implications for public health, particularly in combating the spread of antibiotic resistance [25] [8].

This guide objectively compares these evolutionary trajectories, focusing specifically on the regulatory and functional distinctions between plasmid-borne versus chromosomal gene clusters. We present synthesized experimental data and standardized methodologies to equip researchers with the tools necessary to dissect the contributions of each mechanism to pathogen evolution.

Comparative Analysis of Dissemination Mechanisms

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Horizontal Transfer vs. Vertical Inheritance

| Feature | Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) | Vertical Inheritance |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Movement of genetic material between organisms other than from parent to offspring [23]. | Transmission of DNA from parent to offspring during reproduction [23]. |

| Primary Mechanisms | Transformation, transduction, conjugation, gene transfer agents [23]. | Chromosomal replication and cell division. |

| Evolutionary Role | Rapid adaptation, spread of antibiotic resistance, acquisition of new metabolic functions [24] [23]. | Preservation of core genomic functions, species stability, gradual evolution [24]. |

| Impact on Phylogeny | Creates network-like evolutionary relationships; can obscure phylogenetic signals [24]. | Results in tree-like, divergent evolution [24]. |

| Typical Genetic Carriers | Plasmids, transposons, bacteriophages, genomic islands [23] [25]. | Bacterial chromosome. |

| Control by Cell | Can be regulated (e.g., competence induction, restriction systems) but is often controlled by mobile element genes [24]. | Tightly controlled by cellular replication machinery. |

| Inheritance Stability | Often unstable, can be gained or lost from a lineage without affecting core fitness [26]. | Highly stable, essential for defining the organism. |

Table 2: Plasmid-Borne vs. Chromosomal Gene Cluster Regulation

| Aspect | Plasmid-Borne Gene Clusters | Chromosomal Gene Clusters |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Context | Located on extrachromosomal, replicating plasmids [27] [28]. | Integrated into the main bacterial chromosome. |

| Transfer Potential | High, especially if on conjugative or mobilizable plasmids [25] [8]. | Low, typically requires mobilization via phages, transposons, or natural transformation. |

| Regulatory Independence | Often possess their own regulatory systems and promoters [27]. | Frequently integrated into the host's native regulatory networks. |

| Copy Number Effect | Variable copy number can influence gene dosage and expression levels [28]. | Typically single-copy, with stable gene dosage. |

| Evolutionary Dynamics | Highly dynamic, can be transferred across broad host ranges [28] [8]. | More stable, primarily evolves through mutation and intra-genomic recombination. |

| Functional Examples | Capsular polysaccharide (cps) clusters [27], antimicrobial resistance (AMR) cassettes [25] [8]. | Enterotoxin operons (e.g., nheABC) in Bacillus cereus [26], core metabolic pathways. |

Experimental Data and Case Studies

Quantifying the Impact of Plasmid-Borne Gene Clusters

Table 3: Experimental Data on Plasmid-Borne Capsular Polysaccharide (CPS) Cluster Function

| Experimental Measure | Wild-Type L. plantarum YC41 | YC41-rmlA− Mutant | YC41-cpsC− Mutant |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPS Yield | Baseline (100%) | Reduced by 93.79% | Reduced by 96.62% |

| Survival Under Acid Stress | Baseline (100%) | Decreased by 56.47% - 93.67% | Decreased by 56.47% - 93.67% |

| Survival Under NaCl Stress | Baseline (100%) | Decreased by 56.47% - 93.67% | Decreased by 56.47% - 93.67% |

| Survival Under H₂O₂ Stress | Baseline (100%) | Decreased by 56.47% - 93.67% | Decreased by 56.47% - 93.67% |

| Colony Phenotype | Ropy (>80 mm strand) | Non-ropy | Non-ropy |

Source: Adapted from [27]. The study demonstrated that the plasmid-borne cps cluster was directly responsible for CPS production and conferred critical stress resistance.

Case Study: Horizontal vs. Vertical Evolution of Enterotoxin Operons

Research on Bacillus cereus sensu lato reveals how HGT and vertical inheritance differentially shape the evolution of virulence. Analysis of 142 genomes showed that the enterotoxin operons nheABC and hblCDAB followed distinct evolutionary paths [26].

- Frequent Horizontal Transfer: The hbl and cytK operons showed ample evidence of HGT, as well as frequent deletion and duplication events. This allows for rapid diversification and spread of these virulence factors among strains [26].

- Strict Vertical Inheritance: In contrast, the nhe operon was found to be primarily vertically inherited. Evidence for stable horizontal transfer of nhe was rare, and no evidence for its deletion was found, suggesting that fitness loss may be associated with losing this operon [26].

This case study highlights that the evolution of even functionally related gene clusters within the same organism can be shaped unexpectedly differently by these two dissemination mechanisms.

Essential Methodologies for Analysis

Protocol 1: Tracking HGT via Conjugal Plasmid Transfer

Objective: To experimentally demonstrate the horizontal transfer of a plasmid-borne antimicrobial resistance (AMR) gene cluster between bacterial strains [25].

Workflow:

Strain Preparation:

- Donor: E. coli NS30, a multi-drug resistant (MDR) strain harboring a conjugative plasmid (pNS30-1) with an AMR cassette.

- Recipient: E. coli J53AziR, a sodium-azide resistant and plasmid-free strain.

Broth Mating:

- Mix 500 µl of exponentially growing cultures of both donor and recipient strains (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.6).

- Incubate the mixture for 12 hours at 37°C without shaking to allow cell-to-cell contact and conjugation.

Selection of Transconjugants:

- Plate the mixture onto selective MacConkey agar containing Ampicillin (100 µg/ml), Ciprofloxacin (8 µg/ml), and Sodium Azide (100 µg/ml).

- The antibiotics select for the transferred AMR genes from the donor, while sodium azide selects against the donor strain, allowing only transconjugants (successful recipient cells) to grow.

Confirmation:

- Sub-culture selected transconjugant colonies in LB broth with the same antibiotics.

- Extract DNA and perform Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) to confirm the transfer of the plasmid and AMR genes into the recipient strain's genome.

Protocol 2: Comparative Genomics for Identifying Vertical Inheritance

Objective: To determine whether a gene cluster is vertically inherited or acquired via HGT by analyzing its phylogenetic consistency [26].

Workflow:

Dataset Curation:

- Compile a set of whole-genome sequences for a group of closely related bacteria (e.g., Bacillus cereus sensu lato).

Core Genome Phylogeny:

- Identify a set of core housekeeping genes present in all strains.

- Concatenate the sequences and construct a master phylogenetic tree (species tree) using tools like IQ-TREE [26].

Gene Tree Construction:

- Extract the sequence of the gene cluster of interest from all genomes.

- Construct a separate phylogenetic tree for this specific cluster.

Incongruence Analysis:

- Compare the topology of the gene tree to the core genome phylogeny.

- Vertical Inheritance: The gene tree topology is congruent with the species tree.

- Horizontal Transfer: Significant incongruence is observed, where the gene tree shows close relatedness between strains that are distantly related in the species tree.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Gene Cluster Dissemination Pathways

Conjugal Plasmid Transfer Experiment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Studying Gene Cluster Dissemination

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Growth Media | Selects for or against specific strains based on their genotype (antibiotic resistance, nutrient auxotrophy). | Selecting transconjugants after conjugation experiments [25]. |

| Competent Cells | Cells treated to be capable of uptaking foreign DNA via transformation. | Studying transformation as a mechanism of HGT in the lab [23]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality genomic DNA, plasmid DNA, or metagenomic DNA from samples. | Whole Genome Sequencing, plasmid analysis [27] [25]. |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Services | Provides complete genetic information of an organism for comparative analysis. | Identifying genomic islands, SNPs, and plasmid content [25] [26]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | For genome assembly, annotation, phylogenetic tree construction, and HGT detection. | Tools like Prokka (annotation), Unicycler (assembly), IQ-TREE (phylogeny) [25] [26]. |

| Conjugative Donor/Recipient Strains | Well-characterized strains used as partners in conjugation experiments to study plasmid transfer. | E. coli J53AziR is a common recipient for AMR plasmid studies [25]. |

Ecological and Evolutionary Significance of Plasmid-Borne Clusters in Niche Adaptation

Plasmids, as mobile genetic elements, are fundamental drivers of bacterial evolution and niche adaptation. This review systematically compares the functional roles and regulatory dynamics of plasmid-borne versus chromosomal gene clusters, synthesizing evidence from diverse ecological niches and clinical settings. We highlight how plasmid-borne clusters facilitate rapid horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of adaptive traits including antimicrobial resistance, biosynthetic capabilities, and stress tolerance mechanisms. Through analysis of current datasets and experimental findings, we demonstrate that plasmid-mediated adaptation operates on fundamentally different evolutionary timescales and network connectivity patterns compared to chromosomal integration, with significant implications for microbial ecology, pathogen evolution, and therapeutic development.

Gene clusters encoding adaptive traits can reside either on chromosomes or plasmids, yet their evolutionary trajectories and functional impacts differ substantially. Chromosomal gene clusters typically represent stable, vertically inherited genetic elements that evolve through gradual mutation and selection within a specific lineage. In contrast, plasmid-borne gene clusters exhibit dynamic horizontal transfer across diverse taxonomic boundaries, enabling rapid dissemination of adaptive traits through microbial populations [10] [29]. This fundamental difference in inheritance mechanism creates distinct selective pressures and evolutionary outcomes that shape microbial adaptation across environments.

The ecological significance of plasmid-borne clusters stems from their mobility, which allows for rapid response to environmental pressures. Plasmid-mediated horizontal gene transfer serves as a bacterial innovation engine, permitting immediate acquisition of pre-adapted genetic modules without the waiting time for spontaneous mutation [29]. This review integrates comparative analysis of plasmid versus chromosomal gene regulation, functional specialization, and evolutionary dynamics across diverse biological systems, from clinical pathogens to environmental microbiomes, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding their distinct yet complementary roles in microbial adaptation.

Comparative Analysis of Plasmid-Borne Versus Chromosomal Clusters

Transmission Patterns and Evolutionary Dynamics

Table 1: Comparative Features of Plasmid-Borne vs. Chromosomal Gene Clusters

| Feature | Plasmid-Borne Clusters | Chromosomal Clusters |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission Mechanism | Horizontal gene transfer across species boundaries [10] | Vertical inheritance within lineage |

| Evolutionary Rate | Rapid dissemination through conjugation, transformation [30] | Gradual evolution through mutation and selection |

| Host Range | Broad, often crossing taxonomic families [31] | Restricted to specific bacterial lineage |

| Genetic Stability | Dynamic gain and loss from populations [10] | Relatively stable maintenance |

| Network Connectivity | Higher protein-protein interaction connectivity [10] | Lower protein-protein interaction connectivity |

Analysis of protein interaction networks reveals that plasmid-encoded proteins surprisingly exhibit greater connectivity compared to chromosomal proteins, countering the hypothesis that highly mobile elements should have fewer molecular interactions [10]. This enhanced connectivity suggests sophisticated integration into host cellular networks despite their mobility. Additionally, plasmid-borne genes constitute approximately 0.65% of the total gene complement per bacterial sample but disproportionately influence adaptive evolution through their transfer capabilities [10].

Functional Roles in Niche Adaptation

Table 2: Documented Adaptive Functions of Plasmid-Borne Gene Clusters

| Adaptive Function | Genetic Elements | Environmental Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial Resistance | blaNDM, blaKPC, blaOXA, blaIMP [32] [33] | Clinical settings, healthcare environments | [31] [33] |

| Capsular Polysaccharide Biosynthesis | cps gene clusters [27] | Food fermentation, gastrointestinal tract | [27] |

| Secondary Metabolite Production | Biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [30] | Marine oxygen-depleted water columns | [30] |

| Heavy Metal Detoxification | Heavy metal resistance genes [33] | Industrial, wastewater environments | [33] [34] |

| Stress Tolerance | Stress response genes [27] | Multiple extreme environments | [27] [29] |

Plasmids disproportionately carry clinically significant genes, harboring 39% of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) and 12% of virulence genes despite comprising only ~2.79% of the total genome content in bloodstream infection isolates [31]. This enrichment highlights their specialized role in encoding accessory functions that provide immediate fitness benefits under specific conditions. The functional differentiation of plasmid cargo by habitat is particularly evident in extremophiles like 'Fervidacidithiobacillus caldus,' where plasmid gene content reflects environmental pressures including temperature, pH, and nutrient availability [29].

Experimental Approaches and Methodological Frameworks

Computational Identification and Analysis

Database Resources and Genome Mining: The PLSDB database represents a cornerstone resource for plasmid research, containing 72,360 curated plasmid records as of its 2025 update [28]. Computational identification of plasmid-borne clusters typically begins with tools like antiSMASH for biosynthetic gene cluster prediction [30] and PlasmidFinder for replicon typing [31]. For example, in studying plasmid diversity in 'F. caldus,' researchers identified >30 distinct plasmids representing five replication-mobilization families through systematic genome mining [29].

Clustering and Classification Methods: Large-scale plasmid comparison employs k-mer similarity networks, where plasmids are clustered based on pairwise k-mer (21 bp) similarity with a Jaccard similarity threshold ≥ 0.90 [33]. This approach successfully classified 92.5% of 1,115 carbapenemase-producing plasmids into distinct plasmid clusters, revealing the predominance of specific genotypes like PC1 (blaKPC-2-positive) and PC2 (blaNDM-1-positive) in healthcare environments [33].

Experimental Validation Protocols

Functional Characterization of Capsular Polysaccharide Clusters: In Lactiplantibacillus plantarum YC41, researchers identified a novel plasmid pYC41 carrying the cpsYC41 gene cluster responsible for capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis [27]. The experimental protocol included:

- Insertional Inactivation: Creation of mutant strains through disruption of rmlA and cpsC genes via insertional inactivation

- Phenotypic Assessment: Quantitative measurement of CPS yields showing reductions of 93.79% and 96.62% in respective mutants

- Functional Complementation: Restoration of CPS production in complemented strains

- Stress Challenge Assays: Comparison of survival rates under acid, NaCl, and H2O2 stresses, with mutants showing 56.47-93.67% reduced survival [27]

Metagenomic Assembly and Validation in Environmental Samples: Analysis of plasmid-borne biosynthetic gene clusters (smBGCs) in the Cariaco Basin redoxcline employed:

- Size-Fractionated Sampling: Sequential filtration through 2.7µm (particle-associated) and 0.22µm (free-living) filters

- Co-assembly and Binning: MetaSPAdes assembly followed by MetaBAT2 binning to reconstruct metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs)

- Quality Filtering: Retention of MAGs with ≥75% completeness and ≤5% contamination

- BGC Prediction and Annotation: antiSMASH analysis with manual curation to identify smBGCs on plasmid contigs [30]

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing plasmid-borne gene clusters, integrating computational and functional approaches.

Regulation and Molecular Interactions

Network Integration and Host Compatibility

The complexity hypothesis of horizontal gene transfer suggests that genes encoding products with many molecular interactions are less likely to be successfully transferred because they require complex integration into existing cellular networks [10]. Surprisingly, systematic analysis of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks across 4,363 bacterial samples revealed that plasmid-encoded proteins exhibit higher connectivity than chromosomal proteins, challenging straightforward applications of this hypothesis [10].

Plasmid-borne genes demonstrate remarkable adaptability to diverse genetic backgrounds, as evidenced by the identification of 15 distinct incompatibility types carrying blaNDM carbapenemase genes across multiple continents [32]. This adaptability stems in part from the modular architecture of plasmids, where backbone genes essential for replication and maintenance are conserved, while cargo genes carrying adaptive functions demonstrate considerable flexibility [31] [33].

Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics and Host Defensome Interactions

The persistence and spread of plasmid-borne clusters are shaped by an ongoing arms race with host defense systems. In 'F. caldus' populations, an inverse relationship exists between defensome complexity and plasmidome abundance/diversity, highlighting how restriction-modification systems, CRISPR-Cas, and abortive infection mechanisms constrain plasmid dissemination [29]. This dynamic interaction creates selective environments where successful plasmid genotypes must either evade host defenses or provide sufficient fitness benefits to outweigh their costs.

Figure 2: Eco-evolutionary dynamics of plasmid-borne clusters, illustrating interactions between selective pressures, horizontal transfer, and host defense systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Plasmid Cluster Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLSDB Database | Curated plasmid reference database | 72,360 plasmid records (2025 update) | [28] |

| antiSMASH | Biosynthetic gene cluster identification | Version 6.0+ with strict mode | [30] |

| STRING Database | Protein-protein interaction analysis | Score threshold >400 recommended | [10] |

| BiG-SCAPE | BGC similarity network analysis | Correlates chemical diversity | [30] |

| Mineral Salt Medium | Acidophile cultivation | pH 2.5, sulfur/tetrathionate sources | [29] |

| Hybrid Assembly | Complete plasmid reconstruction | Illumina + Oxford Nanopore/PacBio | [31] [33] |

Plasmid-borne gene clusters represent dynamic and powerful vehicles for microbial niche adaptation, operating through evolutionary mechanisms distinct from their chromosomal counterparts. Their capacity for horizontal transfer across taxonomic boundaries enables rapid response to environmental pressures, from clinical antibiotic exposure to extreme natural environments. The experimental and computational frameworks summarized here provide researchers with robust methodologies for investigating these systems, while the comparative tables offer clear reference points for evaluating functional significance.

Future research directions should prioritize understanding how plasmid-cluster interactions scale to community-level dynamics, particularly in complex microbiomes where multiple plasmids coexist and interact. Additionally, integration of machine learning approaches with the expanding plasmid databases like PLSDB may enable prediction of emerging resistance trajectories and preemptive therapeutic design. As methodological advances continue to enhance our resolution of plasmid biology, their fundamental role in microbial evolution and adaptation across the biosphere becomes increasingly evident.

Advanced Tools and Techniques for Deconvoluting Plasmid and Chromosome Regulation

For decades, genetic analysis has relied heavily on short-read sequencing technologies, which provide excellent base-level accuracy but fragment genomic landscapes into small pieces. This approach has proven particularly limiting for studying complex genetic architectures including plasmid structures and chromosomal gene clusters, where repetitive elements, long-range interactions, and structural variations play crucial functional roles. The emergence of long-read sequencing (LRS) technologies has fundamentally transformed our capacity to resolve these complex biological systems in their native context.

Within comparative studies of plasmid-borne versus chromosomal gene cluster regulation, long-read sequencing provides unprecedented resolution. Plasmids often harbor mobile genetic elements, antibiotic resistance genes, and regulatory modules that interact dynamically with chromosomal content. Traditional short-read approaches frequently miss structural variations, epigenetic modifications, and phasing information essential for understanding how gene regulation differs between plasmid and chromosomal contexts. This technological advancement enables researchers to move beyond fragmented views toward comprehensive understanding of genetic regulation across cellular compartments.

Technology Comparison: Long-Read Sequencing Platforms

Platform Performance Metrics

The two dominant long-read sequencing platforms—Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)—employ fundamentally different approaches to generate long sequencing reads, each with distinct strengths and limitations for plasmid and chromosomal analysis [35] [36].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major Sequencing Platforms

| Technology | Platform Examples | Read Length (Max) | Accuracy | Key Applications | Major Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi | Sequel II, Revio | >20 kb | >99.9% (Q30+) | Plasmid validation, haplotype phasing, structural variant detection | High accuracy circular consensus reads, epigenetic detection |

| ONT | MinION, GridION, PromethION | >100 kb, up to several Mb | 87-98% (raw), >99% with correction | Rapid plasmid sequencing, metagenomics, large structural variants | Ultra-long reads, real-time analysis, portability |

| Illumina (Short-read) | NovaSeq, NextSeq | 150-300 bp | >99.9% (Q30+) | Variant validation, RNA-seq, targeted sequencing | High throughput, low cost per base for targeted applications |

PacBio's single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing utilizes circularized DNA templates and fluorescent nucleotide detection to generate high-fidelity (HiFi) reads through circular consensus sequencing [36]. This approach provides the exceptional accuracy needed for confident variant detection while maintaining long read lengths. Oxford Nanopore technology employs a fundamentally different method, measuring changes in electrical current as DNA strands pass through protein nanopores [35] [36]. This enables extremely long reads—sometimes exceeding 1 megabase—and direct detection of epigenetic modifications without additional processing.

Technical Specifications and Output

Table 2: Technical Specifications and Throughput Capacity

| Parameter | PacBio Sequel II | ONT PromethION | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput per flow cell | 50-100 Gb | 50-100 Gb | 3000 Gb |

| Typical Read Length | 10-30 kb (HiFi) | 10-60 kb (long), >100 kb (ultra-long) | 150 bp (paired-end) |

| Error Profile | Random errors | Higher in homopolymer regions | Low, random errors |

| Epigenetic Detection | Native detection of methylation | Native detection of base modifications | Requires bisulfite conversion |

| Time to Results | 1-2 days | 1-3 days (or real-time) | 1-3 days |

| Cost per Gb (USD) | $13-26 [35] | $21-42 [35] | $10-35 [35] |

For comprehensive plasmid and chromosomal analysis, each technology offers distinct advantages. PacBio HiFi provides exceptional consensus accuracy ideal for confirming plasmid sequences without amplification bias [37]. ONT delivers ultra-long reads capable of spanning even large plasmids in single reads, enabling complete assembly without fragmentation [37] [38]. Illumina short-read technology still plays a valuable role in polishing long-read assemblies through hybrid approaches that combine the advantages of both technologies [37].

Experimental Design for Plasmid and Chromosomal Analysis

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

Robust experimental design begins with high-quality DNA extraction and thorough quality control measures. For plasmid studies, this requires standardized extraction protocols using alkaline lysis followed by column purification to maintain plasmid integrity while minimizing host DNA contamination [37].

Critical steps for optimal sample preparation:

- Use recA⁻ strains like DH5α during plasmid propagation to maintain structural stability

- Implement gentle mixing during lysis (P2 buffer for no more than 5 minutes) to prevent genomic DNA fragmentation

- Employ enzymatic digestion with Benzonase or salt-tolerant nucleases to degrade contaminating host DNA

- Verify DNA quality via spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ≥ 1.8) and gel electrophoresis to confirm supercoiled structure

- For challenging samples, use ddPCR validation (e.g., Bio-Rad Vericheck) to quantify trace host DNA down to 0.001% [37]

For chromosomal studies focusing on gene clusters, high-molecular-weight DNA extraction is essential. This often involves agarose plug embedding or similar approaches to prevent mechanical shearing of DNA, preserving long fragments necessary for spanning repetitive regions and structural variants.

Platform Selection Guide

Table 3: Platform Selection Based on Research Application

| Research Goal | Recommended Platform | Sequencing Strategy | Coverage Depth | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete plasmid validation | PacBio HiFi | Single library, circular consensus | 20-50x | Optimal for GC-rich regions, repetitive elements |

| Large plasmid characterization (>50 kb) | ONT | Ultra-long reads | 30-100x | Can span entire megaplasmids in single reads |

| Hybrid assembly | ONT + Illumina or PacBio + Illumina | Hybrid correction | 50x (long) + 30x (short) | Maximizes both contiguity and accuracy |

| Plasmid-chromosome interactions | ONT with adaptive sampling | Targeted enrichment | Varies by target | Enables focusing on specific genomic regions |

| Antimicrobial resistance plasmid surveillance | ONT | Multiplexed libraries | 50-100x | Rapid turnaround for clinical applications |

Matching the sequencing platform to the biological question is essential for efficient resource utilization. For small plasmids (<10 kb), either Sanger sequencing or Illumina approaches remain cost-effective. For medium-sized plasmids (10-20 kb), PacBio HiFi provides an optimal balance of read length and accuracy. For large plasmids (>20 kb) or those with complex architectures including inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) or high GC-content islands, ONT ultra-long reads become indispensable [37].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Whole Plasmid Sequencing Workflow

The complete plasmid sequencing workflow enables comprehensive characterization of plasmid structure, including detection of mutations, rearrangements, and contaminations that often evade traditional verification methods [39] [37].

Protocol: Comprehensive Plasmid Validation Using Long-Read Sequencing

Plasmid Preparation: Isolate plasmid DNA using alkaline lysis followed by column purification. For low-copy number plasmids, scale up culture volume accordingly [37].

Library Preparation (ONT):

- Use transposome complex to randomly fragment plasmid DNA, creating amplification-free library of full-length linear molecules

- Attach motor proteins and sequencing adapters without amplification bias

- Load onto flow cell without size selection to preserve structural heterogeneity information [39]

Library Preparation (PacBio):

Sequencing Run:

- For ONT: Perform 24-72 hour runs depending on plasmid size and complexity

- For PacBio: Generate HiFi reads using circular consensus sequencing (CCS) with multiple passes per molecule

Data Analysis:

- Base calling with platform-specific tools (Guppy for ONT, SMRT Link for PacBio)

- Read quality assessment and filtering

- De novo assembly or reference-based mapping

- Variant detection and structural annotation

- Generation of consensus sequence in standard formats (.fasta, .gbk) [39]

This protocol typically delivers results within 24-48 hours, significantly faster than traditional Sanger-based approaches that require multiple primer walks and weeks of turnaround time [39] [40].

Chromosomal Gene Cluster Analysis

Protocol: Resolving Complex Chromosomal Loci Using Long Reads

High-Molecular-Weight DNA Extraction:

- Culture cells under appropriate conditions

- Embed in agarose plugs to prevent mechanical shearing

- Perform in-gel lysis and protein removal

- Electroelute DNA from plugs, minimizing pipetting-induced fragmentation

Library Preparation for Ultra-Long Reads:

- Use ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit with minimal fragmentation

- Optimize cleanup steps to retain longest fragments (>100 kb)

- Employ size selection if necessary, but prioritize length retention

Sequencing with Coverage Considerations:

- For complex regions with repeats, aim for >30x coverage with long reads

- Consider adaptive sampling for targeted enrichment of specific gene clusters [36]

- Perform multiplexing if analyzing multiple strains or conditions

Hybrid Assembly Approach:

- Perform initial assembly using long-read focused assemblers (Canu, Flye)

- Polish assembly with complementary data (Illumina short reads or PacBio HiFi)

- Validate assembly quality using checkM, BUSCO, or similar metrics

- Annotate using combined evidence and curated databases

This approach has proven particularly powerful for studying antibiotic resistance clusters, virulence gene islands, and biosynthetic gene clusters where structural configuration significantly impacts function and regulation [41] [8].

Data Analysis Frameworks

Hybrid Assembly Implementation

For the most challenging plasmid and chromosomal analyses, hybrid assembly approaches that combine long-read and short-read data provide optimal results by balancing the advantages of each technology [37].

Figure 1: Hybrid assembly workflow combining long and short reads for optimal results. The process leverages long reads for scaffolding and short reads for base-level accuracy.

Key hybrid correction strategies include:

Homopolymer compression alignment (as implemented in LSC) improves mapping sensitivity of short reads to long-read sequences.

Localized reassembly tools (e.g., CoLoRMap) construct overlap graphs from short reads to fill uncorrected regions with high resolution, though this approach is computationally intensive.

Dual-channel correction (exemplified by FMLRC) combines FM-index technology with k-mer scaling, using short k-mers (21-mers) to correct simple errors followed by longer k-mers (59-mers) for refining complex or repetitive zones [37].

For challenging repetitive elements—including tandem direct repeats, palindromic structures, and high-GC repeat islands—specialized approaches are required. Long reads physically span these problematic regions, while short reads provide base-level accuracy for polishing. Additional validation using PCR and Sanger sequencing confirms difficult regions, while qPCR validates copy number variations in repetitive zones [37].

Plasmid-Specific Bioinformatic Tools

Specialized tools have emerged for plasmid-specific analysis, addressing challenges such as plasmid-chromosome recombination, multi-plasmid communities, and horizontal gene transfer events.

PlasmidFocus: Identifies and characterizes plasmids in complex samples using sequence composition and coverage depth variation.

MOB-suite: Reconstructs and types plasmid sequences while predicting mobility and host range.

AMRFinderPlus: Identifies antibiotic resistance genes, particularly useful for tracking plasmid-borne resistance mechanisms [41].

These tools have revealed fascinating biological insights, such as the existence of plasmid communities where multiple plasmids co-exist within bacterial hosts, enabling non-AMR plasmids to survive antimicrobial selection through co-existence with resistant partners [8].

Comparative Analysis: Plasmid vs. Chromosomal Contexts

Structural and Regulatory Differences

Long-read sequencing has enabled direct comparison of genetic elements in plasmid versus chromosomal contexts, revealing significant differences in organization, regulation, and evolutionary dynamics.

Table 4: Plasmid vs. Chromosomal Gene Regulation Characteristics

| Feature | Plasmid Context | Chromosomal Context | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Organization | Often clustered with mobile elements | More dispersed, operonic structures | WPS shows co-localized ARGs on plasmids [8] |

| Regulatory Elements | Compact, efficient promoters | Complex, multi-level regulation | LRS reveals minimal promoters on AMR plasmids |

| Copy Number Effects | Variable (1->100+ copies/cell) | Fixed (1-2 copies/cell) | Coverage depth analysis shows plasmid copy number variation |

| Evolutionary Rate | Rapid adaptation via HGT | Slower, mutation-driven | Comparative genomics shows plasmid recombination hotspots |

| Epigenetic Regulation | Targeted methylation silencing | Chromatin-level organization | Native LRS detects distinct methylation patterns |

Studies of multi-drug resistant pathogens have demonstrated that plasmid-borne resistance genes often exist in complex clusters containing multiple resistance mechanisms, metal resistance genes, and mobile genetic elements that facilitate rapid horizontal transfer [8]. In contrast, chromosomal resistance genes typically show more stable integration with host regulatory networks.

Functional Implications for Drug Development

Understanding the distinctions between plasmid and chromosomal gene regulation has profound implications for antibiotic development, resistance management, and therapeutic strategy.

Key insights from comparative analyses:

Plasmid-borne resistance demonstrates higher mobility between bacterial species, necessitating containment strategies that target conjugation mechanisms.

Chromosomal resistance mutations develop more slowly but prove more stable once established, requiring different therapeutic approaches.

Gene dosage effects differ significantly between contexts, with plasmid amplification enabling immediate high-level resistance versus chromosomal integration providing more moderate but stable resistance.

Recent research on E. coli strain S3 from poultry farms in Nigeria demonstrated the coexistence of multiple plasmids carrying extensive resistance genes ((bla{CTX-M-15}), (bla{OXA-1}), (aac(6')-Ib-cr)), alongside chromosomal virulence factors, highlighting the complex interplay between plasmid and chromosomal elements in clinical settings [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Plasmid and Chromosomal Analysis

| Category | Specific Products/Tools | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit, Promega Wizard Plus SV | High-quality plasmid DNA | Selective host DNA removal, maintains supercoiled structure |

| Long-Recad Library Prep | ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit, PacBio SMRTbell Express | Library preparation | Minimal bias, compatible with long fragments |

| Quality Control | Agilent TapeStation, Qubit Fluorometer | DNA quantification and quality assessment | Accurate concentration, integrity number |

| Computational Tools | Flye, Canu, Unicycler | Genome assembly | Handles long reads, resolves repeats |

| Specialized Analysis | AMRFinderPlus, PlasmidFinder, MOB-suite | Plasmid characterization | Database-driven annotation, mobility prediction |

| Validation | Sanger sequencing, PCR reagents | Targeted confirmation | High accuracy for specific regions |

This toolkit enables end-to-end analysis from sample preparation through computational interpretation. For clinical applications or rapid diagnostics, streamlined versions of these workflows can generate results in as little as 24 hours, enabling timely intervention for outbreak management [40].

Long-read sequencing technologies have fundamentally transformed our ability to resolve complete plasmid structures and their chromosomal contexts, enabling unprecedented insights into genetic regulation across cellular compartments. By providing continuous sequence information across complex genomic regions, these approaches reveal structural variations, epigenetic modifications, and organizational patterns that were previously inaccessible through short-read methodologies.

The comparative analysis of plasmid-borne versus chromosomal gene regulation highlights fundamental differences in how genetic information is organized, expressed, and evolved in different cellular contexts. These insights prove particularly valuable for understanding antimicrobial resistance mechanisms, virulence pathways, and bacterial evolution in clinical and environmental settings.

As long-read technologies continue to evolve toward higher throughput, improved accuracy, and lower costs, their application will expand further into routine clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and therapeutic development. The integration of these approaches with single-cell analysis, spatial transcriptomics, and real-time surveillance will provide increasingly comprehensive understanding of genetic systems in their native contexts, driving innovations across basic research, clinical medicine, and public health.