PCR Troubleshooting Guide: Solving Inefficient Reactions for Robust and Reproducible Results

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose and resolve inefficient PCR reactions.

PCR Troubleshooting Guide: Solving Inefficient Reactions for Robust and Reproducible Results

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose and resolve inefficient PCR reactions. Covering foundational principles to advanced optimization strategies, it details systematic troubleshooting for common issues like no amplification, non-specific products, and smeared bands. The article also explores specialized PCR methods, reagent validation techniques, and best practices to ensure high yield, specificity, and fidelity for critical biomedical applications.

Understanding PCR Fundamentals: How Reaction Components and Conditions Govern Efficiency

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, enabling researchers to amplify specific DNA sequences from minimal starting material. The core PCR workflow consists of three essential steps—denaturation, annealing, and extension—that are repeated in cycles to achieve exponential amplification [1] [2]. While the process is robust, its efficiency is highly dependent on precise reaction conditions. This guide addresses common troubleshooting issues within the context of this core workflow to help researchers and drug development professionals optimize their experiments and resolve inefficient reactions efficiently.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the temperature and time specifications for the three core PCR steps?

The typical temperature and time ranges for each step in a standard PCR cycle are summarized in the table below. Note that these can vary based on the DNA polymerase used and the specific target [2] [3].

| PCR Step | Typical Temperature Range | Typical Time | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturation | 94–98°C | 15–30 seconds | Separates double-stranded DNA into single strands [4] [2]. |

| Annealing | 50–65°C | 10–30 seconds | Allows primers to bind to their complementary sequences on the single-stranded DNA templates [4] [5]. |

| Extension | 68–72°C | 1 minute per 1 kb | Enables DNA polymerase to synthesize a new DNA strand by adding nucleotides to the 3' end of the primer [4] [2]. |

2. Why am I getting no PCR product or a very low yield?

A lack of amplification can be attributed to several factors related to the core workflow and reaction components. Please follow the troubleshooting workflow below to diagnose the issue.

3. My gel shows multiple bands or a smear instead of one clean band. How can I improve specificity?

Non-specific amplification is often a direct result of suboptimal conditions during the annealing step or problematic reaction components [6] [7].

- Increase Annealing Temperature: The most common fix is to increase the annealing temperature in increments of 1–2°C. The optimal temperature is typically 3–5°C below the calculated Tm (melting temperature) of the primers [7] [8]. Use a gradient thermal cycler if available.

- Use a Hot-Start DNA Polymerase: These enzymes are inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [6] [7].

- Optimize MgCl₂ Concentration: Excess Mg²⁺ can reduce specificity. Titrate the Mg²⁺ concentration downward in 0.2–1.0 mM increments to find the optimal level [7] [8].

- Check Primer Design and Concentration: Ensure primers are specific and do not have complementary regions, especially at their 3' ends. High primer concentrations can promote mispriming; optimize concentration within the 0.1–1 µM range [7] [5].

- Reduce Cycle Number: An excessive number of cycles can lead to the accumulation of non-specific products. Try reducing the number of cycles [7].

4. How can I prevent primer-dimer formation?

Primer-dimer occurs when primers anneal to each other rather than to the template DNA, resulting in short, unwanted products [6].

- Optimize Primer Design: Carefully design primers to minimize complementarity, especially at the 3' ends. Avoid long runs of a single nucleotide (e.g., GGGG) [5].

- Adjust Reaction Conditions: Increase the annealing temperature and/or reduce the primer concentration [6] [7].

- Use a Hot-Start Polymerase: This prevents the polymerase from extending primers that anneal non-specifically at low temperatures during reaction setup [6].

5. How do I amplify difficult templates like GC-rich regions?

GC-rich sequences can form stable secondary structures that prevent efficient denaturation and primer annealing [7].

- Use PCR Additives or Co-solvents: Additives like DMSO (1-10%), formamide (1.25-10%), or betaine (0.5 M to 2.5 M) can help denature stable GC-rich templates and are included in many commercial enhancer solutions [7] [5].

- Increase Denaturation Temperature and Time: A higher denaturation temperature (e.g., 98°C) or a longer denaturation time may be necessary [7].

- Choose a Specialized DNA Polymerase: Use a polymerase with high processivity, which displays high affinity for DNA templates and is better suited for amplifying difficult targets [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential PCR Reagents

A successful PCR reaction requires a precise mix of key components. The table below details the function and critical considerations for each essential reagent.

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations & Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Template | The target DNA sequence to be amplified. | Purity & Integrity: Contaminants (phenol, EDTA, proteins) or degraded DNA can inhibit PCR. Re-purify if necessary [7] [9].Quantity: Use 1 pg–1 µg depending on template complexity (e.g., plasmid vs. genomic DNA) [8]. |

| Primers | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences that define the start and end of the amplified region. | Design: Length of 15-30 bases; 40-60% GC content; avoid self-complementarity and primer-dimer formation [5].Concentration: Typically 0.1–1 µM each primer. Too high can cause non-specific binding [7]. |

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands by adding dNTPs to the 3' end of the primers. | Choice: Taq polymerase is common but lacks proofreading. Use high-fidelity enzymes (e.g., Q5, Pfu) for cloning [1] [4].Hot-Start: Recommended to suppress non-specific amplification during setup [6] [7]. |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for new DNA. | Concentration: Typically 200 µM of each dNTP. Unbalanced concentrations can increase error rate [7] [5].Quality: Use fresh, high-quality stocks to prevent degradation [8]. |

| Reaction Buffer | Provides the optimal chemical environment (pH, salts) for the polymerase to function. | Mg²⁺: A critical cofactor for polymerase activity. The concentration often requires optimization (e.g., 1.5–2.5 mM) [7] [4].Other Components: May include additives like (NH₄)₂SO₄ or KCl to enhance specificity and yield [5]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Conventional PCR

This protocol provides a standardized methodology to set up a 50 µL conventional PCR reaction, which can be scaled as needed [5].

1. Primer Design and Preparation

- Design forward and reverse primers specific to your target sequence using software tools (e.g., NCBI Primer-BLAST).

- Follow best practices: primer length of 15-30 nucleotides, Tm of 55-65°C for both primers (within 5°C of each other), and GC content of 40-60% [5].

- Resuspend primers in sterile, nuclease-free water or TE buffer to create a concentrated stock (e.g., 100 µM). Prepare a working aliquot (e.g., 20 µM) to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

2. Reaction Setup

- Master Mix: When running multiple samples, prepare a master mix to ensure consistency. Combine the following components in a sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube on ice. Gently mix by pipetting up and down or brief vortexing followed by a quick spin [5].

| Component | Final Concentration/Amount | Volume for 1x 50 µL Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease-free Water | Q.S. to 50 µL | (36 - X) µL |

| 10X PCR Buffer | 1X | 5 µL |

| dNTP Mix (10 mM total) | 200 µM (each) | 1 µL |

| MgCl₂ (25 mM) | 1.5 mM (or as optimized) | 3 µL (variable) |

| Forward Primer (20 µM) | 0.4 µM | 1 µL |

| Reverse Primer (20 µM) | 0.4 µM | 1 µL |

| DNA Template | Variable (e.g., 1-100 ng) | X µL (e.g., 0.5-5 µL) |

| DNA Polymerase (5 U/µL) | 1.25 U | 0.25 µL |

| Total Volume | 50 µL |

- Aliquot and Add Template: Dispense the appropriate volume of master mix into individual PCR tubes. Then, add the required volume of each DNA template to its respective tube. Include a negative control (replace template with nuclease-free water).

3. Thermal Cycling

| Step | Temperature | Time | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 94–95°C | 2–5 minutes | 1 |

| Denaturation | 94–95°C | 15–30 seconds | |

| Annealing | Tm of primers -5°C* | 15–30 seconds | 25–35 |

| Extension | 68–72°C | 1 minute per 1 kb | |

| Final Extension | 68–72°C | 5–10 minutes | 1 |

| Hold | 4–10°C | ∞ | 1 |

*Note: The annealing temperature must be determined empirically. Start 3–5°C below the lower Tm of your primer pair and optimize using a gradient cycler [7] [5].

4. Product Analysis

- Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. A successful reaction should show a single, sharp band of the expected size when compared to a DNA ladder.

Core Components and Their Functions

The success of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) hinges on the precise function and balance of its core components. Understanding the role of each is the first step in effective troubleshooting.

Template DNA

Template DNA is the source material that contains the target sequence to be amplified. Its quality, quantity, and complexity are paramount for successful PCR [10].

- Function: Provides the blueprint that the primers and DNA polymerase use to synthesize new DNA strands.

- Key Considerations: The optimal amount of template DNA depends on its source and complexity [10]. Using too much DNA can lead to nonspecific amplification, while too little can result in low yield or no product [10] [7]. For genomic DNA, 1 ng–1 µg per 50 µL reaction is common, whereas only 0.1–1 ng of plasmid DNA may be sufficient [10] [11]. The template must be of high integrity and free of inhibitors such as phenol, EDTA, or proteases that can co-purify during extraction [7].

Primers

Primers are short, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides (typically 15–30 bases) that are complementary to the sequences flanking the target region [10]. They are the most common source of PCR failure if not properly designed or used.

- Function: To provide a starting point, or primer, for the DNA polymerase to begin synthesis of the new DNA strand.

- Key Considerations: Primer design is critical for specificity. They should have a melting temperature (Tm) between 55–70°C, with the Tm of each primer in a pair within 5°C of each other [10] [5]. The GC content should be 40–60%, and the 3' end should avoid runs of identical bases and should not be complementary to the other primer to prevent "primer-dimer" formation [10] [5]. In a reaction, primer concentrations of 0.1–1 µM are typical; higher concentrations can promote mispriming and nonspecific amplification [10] [7].

Deoxynucleoside Triphosphates (dNTPs)

dNTPs are the building blocks—dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP—from which the DNA polymerase synthesizes a new DNA strand [12].

- Function: To provide the necessary nucleotides for the DNA polymerase to incorporate into the newly synthesized DNA strand.

- Key Considerations: The four dNTPs should be added in equimolar concentrations [10] [7]. A typical final concentration for each dNTP is 0.2 mM [10]. Unbalanced dNTP concentrations can increase the error rate of the polymerase [7]. Excessively high dNTP concentrations can be inhibitory, and they can also chelate Mg²⁺, making it unavailable for the polymerase [10].

Buffer and Magnesium Ions (Mg²⁺)

The reaction buffer provides a stable chemical environment, with Mg²⁺ acting as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity [12].

- Function: The buffer stabilizes the reaction pH, while Mg²⁺ facilitates primer binding to the template and catalyzes the phosphodiester bond formation during nucleotide incorporation [10].

- Key Considerations: Mg²⁺ concentration is a critical variable that often requires optimization. The presence of chelators (like EDTA) or high dNTP concentrations can affect the amount of free Mg²⁺ available [7]. A final concentration of 1.5–2.0 mM is a common starting point, but adjusting this in 0.2–1.0 mM increments can resolve issues with specificity and yield [11] [5]. Excessive Mg²⁺ can reduce fidelity and promote nonspecific binding [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common PCR Problems

This guide addresses frequent issues, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Product [11] [7] | Incorrect annealing temperature | Recalculate primer Tm and test a temperature gradient 5°C below the lower Tm [11]. |

| Poor template quality or quantity | Re-purify template DNA to remove inhibitors; check concentration and integrity by gel electrophoresis [11] [7]. | |

| Missing reaction component | Carefully repeat reaction setup; use a master mix to ensure consistency [11] [12]. | |

| Insufficient number of cycles | Increase cycles to 35–40, especially for low-copy-number templates [7]. | |

| Multiple or Nonspecific Bands [11] [7] | Annealing temperature too low | Increase annealing temperature stepwise by 1–2°C [11] [7]. |

| Excess Mg²⁺, primers, or DNA polymerase | Lower Mg²⁺ concentration; optimize primer concentrations (0.1–1 µM); reduce enzyme amount [10] [11] [7]. | |

| Nonspecific priming | Use a hot-start DNA polymerase; review primer design for specificity and secondary structures [11] [7]. | |

| Too much template DNA | Reduce the amount of input DNA [7]. | |

| Smear of Bands [7] | Degraded template DNA | Assess DNA integrity on a gel; minimize shearing during isolation [7]. |

| Excess PCR cycles | Reduce the number of cycles [7]. | |

| Primer-Dimer Formation [10] [7] | Primer 3' end complementarity | Redesign primers to avoid 3' end complementarity between the forward and reverse primers [10] [5]. |

| Excess primer concentration | Lower the primer concentration in the reaction [10] [7]. | |

| Low annealing temperature | Increase the annealing temperature [7]. | |

| Sequence Errors (Low Fidelity) [11] [7] | Low-fidelity DNA polymerase | Switch to a high-fidelity, proofreading polymerase [11] [7]. |

| Unbalanced dNTP concentrations | Use fresh, equimolar dNTP mixes [11] [7]. | |

| Excess Mg²⁺ | Optimize and potentially lower the Mg²⁺ concentration [11] [7]. |

PCR Component Relationships

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My PCR worked but the yield is very low. What can I do to improve it? A: Low yield can be addressed by several methods:

- Template and Enzymes: Ensure sufficient template DNA is being used and consider using a DNA polymerase engineered for high sensitivity and yield [7].

- Cycle Optimization: Increase the number of cycles up to 40, particularly if the starting template copy number is low [7].

- Component Re-optimization: Re-visit the concentration of Mg²⁺, primers, and dNTPs, as suboptimal levels can limit efficiency [10] [11].

- Extension Time: Ensure the extension time is sufficient for the length of your amplicon (typically 1–2 minutes per kilobase) [12].

Q2: How do I troubleshoot a PCR that has no product and where should I start? A: Begin with a systematic approach:

- Controls: Verify your negative control (no template) is clean and your positive control (known working primers/template) works. This determines if the issue is with your reaction or your specific primers/template [5].

- Primer Design: Re-check your primer sequences for specificity, secondary structures, and correct Tm. Use online design tools like Primer-BLAST [11] [5].

- Annealing Temperature: Test an annealing temperature gradient from 5°C below to 5°C above the calculated Tm of your primers [11].

- Template Quality: Re-purify your template DNA to remove potential inhibitors and check its integrity by running it on a gel [11] [7].

Q3: I have a GC-rich template that is difficult to amplify. What are my options? A: GC-rich sequences can form stable secondary structures. To overcome this:

- Specialized Reagents: Use a DNA polymerase with high processivity, designed for difficult templates [7].

- Additives: Include PCR enhancers like DMSO (1–10%), formamide (1.25–10%), or Betaine (0.5 M to 2.5 M) in the reaction to help denature the stable structures [7] [5].

- Cycling Conditions: Increase the denaturation temperature and/or time to ensure full separation of the DNA strands [7].

Q4: How can I prevent primer-dimer formation in my reactions? A: Primer-dimer is often due to complementarity between the 3' ends of your primers.

- Redesign: The most effective long-term solution is to redesign primers to eliminate 3' complementarity [10].

- Optimize Concentrations: Lower the primer concentration in the reaction [10] [7].

- Use Hot-Start: A hot-start DNA polymerase, which is inactive until the initial denaturation step, can prevent primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [7].

- Increase Temperature: A higher annealing temperature can reduce the chance of primers annealing to each other [7].

PCR Troubleshooting Path

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

A successful PCR experiment relies on high-quality reagents and proper techniques. The following table details key components for your toolkit.

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands. | Choose based on application: standard (Taq), high-fidelity (Q5, Phusion), or for difficult templates (high processivity) [10] [11] [7]. |

| 10X Reaction Buffer | Provides optimal pH, ionic strength, and cofactors. | Often contains KCl and may contain MgCl₂. The composition is typically optimized by the enzyme manufacturer [12]. |

| MgCl₂ / MgSO₄ Solution | Source of Mg²⁺, an essential cofactor for polymerase activity. | Concentration must be optimized; it is a common variable for troubleshooting. MgSO₄ is preferred for some proofreading enzymes [7] [5]. |

| dNTP Mix | A solution containing equimolar amounts of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP. | Use a balanced, high-quality stock to prevent incorporation errors. Typical final concentration is 0.2 mM of each dNTP [10] [12]. |

| Oligonucleotide Primers | Short DNA sequences that define the start and end of the amplification. | Must be well-designed, specific, and resuspended at a standardized concentration (e.g., 10 µM stock) [10] [12]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent for the reaction. | Must be free of nucleases to prevent degradation of primers and template. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., DMSO, BSA) | Enhancers that help with difficult templates like GC-rich sequences. | Use at recommended concentrations (e.g., DMSO at 1-10%) as they can inhibit the reaction if overused [7] [5]. |

| Template DNA | The DNA source containing the target sequence. | Can be genomic, plasmid, or cDNA. Must be pure, intact, and at an appropriate concentration [10]. |

Core Concepts: Thermostability, Fidelity, and Processivity

Thermostability is a fundamental property of DNA polymerases used in PCR, referring to the enzyme's ability to withstand the high temperatures (typically 90-95°C) required for DNA denaturation without permanent loss of activity. This characteristic is inherent to polymerases isolated from thermophilic organisms. Engineered versions often exhibit enhanced thermostability for better performance during repeated thermal cycling [13] [14].

Fidelity describes the accuracy of DNA synthesis, quantified as the error rate per base incorporated. High-fidelity polymerases incorporate fewer errors during amplification, which is crucial for applications like cloning and sequencing. Fidelity is often expressed relative to Taq polymerase (e.g., 280x higher fidelity for Q5 polymerase) or as an error rate (e.g., 5 × 10⁻⁶ errors per base) [15]. Polymerases with 3'→5' exonuclease ("proofreading") activity typically exhibit higher fidelity by correcting misincorporated nucleotides [15] [14].

Processivity indicates the average number of nucleotides a polymerase adds per binding event. High-processivity enzymes can amplify longer DNA fragments more efficiently and are better suited for complex templates with secondary structures or high GC content. Processivity can be enhanced through protein engineering, such as fusion to DNA-binding domains like Sso7d [15] [16].

DNA Polymerase Troubleshooting FAQs

No or Low Amplification Yield

- Problem: No band or faint band observed on gel after PCR.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Template Quality/Degradation: Verify template integrity by gel electrophoresis. Re-purify if degraded or contaminated with inhibitors [7] [17].

- Suboptimal Reaction Conditions: Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration (typically 0.2-1 mM increments) and annealing temperature (use gradient PCR). Ensure correct primer concentrations (0.1-1 µM) [6] [17].

- Insufficient Enzyme Activity: Increase polymerase amount or switch to a more processive enzyme. Confirm enzyme is added and hasn't been inactivated [7].

- Insufficient Denaturation: Increase denaturation temperature or duration, especially for GC-rich templates [7].

Non-Specific Amplification/Multiple Bands

- Problem: Multiple unexpected bands appear on the gel.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Low Annealing Stringency: Increase annealing temperature incrementally (1-2°C steps). Use hot-start polymerases to prevent primer-dimer formation and non-specific amplification at lower temperatures [6] [7] [17].

- Excess Reaction Components: Reduce primer, Mg²⁺, or polymerase concentrations. High primer concentrations promote mispriming [7] [17].

- Primer Design Issues: Verify primer specificity using design software. Avoid primers with complementary regions or GC-rich 3' ends [7] [17].

- Template Contamination: Use dedicated pre-PCR workspace and reagents. Employ uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG) treatment with dUTP-containing reactions to prevent carryover contamination [17] [16].

High Error Rate in Cloned PCR Products

- Problem: Sequencing reveals unexpected mutations in cloned amplicons.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Low-Fidelity Polymerase: Switch to high-fidelity proofreading enzymes (e.g., Q5, Pfu) with error rates 10-100x lower than Taq [17] [15].

- Unbalanced dNTPs: Use fresh, equimolar dNTP mixtures. Unbalanced concentrations increase misincorporation [7] [17].

- Excessive Cycle Number: Reduce PCR cycles to minimize cumulative errors. Increase initial template amount if possible [7].

- UV Damage: Limit UV exposure during gel extraction; use long-wavelength (360 nm) when possible [7].

DNA Polymerase Selection Guide

Table 1: DNA Polymerase Properties and Applications

| Polymerase | 3'→5' Exonuclease (Proofreading) | Fidelity (Relative to Taq) | Strand Displacement | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | No | 1x (Baseline) | No | Routine PCR, genotyping |

| Q5 High-Fidelity | Yes (++++)) | 280x Taq | No | High-fidelity PCR, cloning, NGS |

| Phusion High-Fidelity | Yes (++++)) | 39-50x Taq | No | High-fidelity PCR, cloning |

| OneTaq | Yes (++)) | 2x Taq | No | Routine PCR, colony PCR |

| Bst DNA Polymerase, Large Fragment | No | Not specified | Yes (++++)) | Isothermal amplification (LAMP, SDA) |

| phi29 DNA Polymerase | Yes (++++)) | 5 (Error rate x 10⁻⁶) | Yes (++++)) | Rolling circle amplification, WGA |

| T4 DNA Polymerase | Yes (++++)) | <1 (Error rate x 10⁻⁶) | No | Blunting ends, fill-in reactions |

Table 2: Polymerase Selection by Template Type

| Template Challenge | Recommended Polymerase Type | Key Features | Example Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC-Rich Sequences | High-processivity with GC enhancer | Improved strand separation, tolerance to secondary structures | Q5 High-Fidelity, OneTaq with GC Buffer [7] |

| Long Amplicons (>10 kb) | Long-range polymerases | High processivity, robust strand displacement | LongAmp Taq, Q5 High-Fidelity [7] [15] |

| High-Fidelity Requirements | Proofreading polymerases | 3'→5' exonuclease activity, low error rates | Q5, Phusion, Pfu [17] [15] |

| Rapid Diagnostics | Fast polymerases | Rapid extension rates, quick activation | Engineered variants with enhanced speed [16] |

| Isothermal Amplification | Strand-displacing polymerases | Strong strand displacement, works at constant temperature | Bst DNA polymerase large fragment [13] [15] |

| Direct Blood PCR | Inhibitor-tolerant polymerases | Resistance to PCR inhibitors in blood | Hemo KlenTaq, Q5 Blood Direct [15] |

Advanced Applications and Engineering Strategies

Engineered Polymerases for Advanced Applications

Protein engineering has created specialized DNA polymerases with enhanced capabilities:

Reverse Transcriptase Activity: Engineered DNA polymerases like novel Taq and Pfu variants can perform both reverse transcription and DNA amplification in a single enzyme, eliminating the need for separate viral reverse transcriptases in RT-PCR [18] [14]. These engineered polymerases maintain thermostability while gaining the ability to utilize RNA templates effectively under standard PCR conditions.

Enhanced Processivity via Fusion Proteins: Fusion of DNA polymerases with DNA-binding domains like Sso7d from Sulfolobus solfataricus significantly increases processivity. For example, the Neq2X7 polymerase demonstrates approximately 8-fold higher activity and can amplify long, GC-rich templates with dramatically reduced extension times compared to non-fused versions [16].

Uracil Tolerance: Natural polymerases like Neq and engineered variants (e.g., PfuX7, Q5U) can efficiently incorporate dUTP and bypass uracil in templates. This enables applications such as USER cloning and contamination control through UNG treatment [15] [16].

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating DNA Polymerase Performance

Objective: Compare processivity and efficiency of different DNA polymerases using standardized amplification conditions.

Materials:

- Test DNA polymerases (e.g., standard vs. high-processivity variants)

- Control template DNA (e.g., lambda DNA, plasmid with known insert)

- Primer sets for various amplicon sizes (0.5kb, 3kb, 10kb)

- dNTP mix (including dUTP for uracil tolerance testing)

- Appropriate reaction buffers for each polymerase

- Thermal cycler with gradient capability

- Gel electrophoresis equipment and DNA staining

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare master mixes for each polymerase according to manufacturer recommendations, maintaining consistent buffer conditions where possible.

- Amplification Protocol:

- Standard conditions: 98°C for 30s; 35 cycles of 98°C for 10s, optimized Tm for 30s, 72°C for varying extension times (15s/kb vs. 1min/kb); 72°C for 5min final extension [16].

- Include GC-rich templates and additives (e.g., DMSO, betaine) for challenging templates.

- Efficiency Analysis:

- Evaluate amplification yield by gel electrophoresis and quantitative methods.

- Compare performance across different template types, lengths, and nucleotide compositions (dTTP vs. dUTP).

- Fidelity Assessment:

- Use established fidelity assays (e.g., magnification via nucleotide imbalance) to determine error rates [16].

- Sequence cloned products to verify mutation frequencies.

Expected Outcomes: High-processivity enzymes (e.g., Sso7d-fused variants) should successfully amplify longer fragments with shorter extension times and maintain activity with challenging templates compared to standard polymerases.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for DNA Polymerase Applications

| Reagent/Chemical | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start Polymerases | Remains inactive at room temperature, activates at high temperatures | Prevents non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation [6] [19] |

| Proofreading Polymerases | Contains 3'→5' exonuclease activity for error correction | High-fidelity applications like cloning and sequencing [15] [14] |

| Betaine (PCR Enhancer) | Reduces secondary structure in GC-rich templates | Improved amplification of high-GC content regions [7] |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Binds inhibitors and stabilizes enzymes | Counteracts PCR inhibition in difficult samples (e.g., blood, soil) [6] |

| dUTP/dNTP Mixes | Replaces dTTP with dUTP for contamination control | Enables UNG treatment to prevent amplicon carryover [15] [16] |

| Mg²⁺ Solutions (MgCl₂/MgSO₄) | Cofactor essential for polymerase activity | Optimization of reaction conditions for specific templates [7] [17] |

| Sso7d Fusion Domain | Non-specific DNA binding domain | Enhances polymerase processivity when fused to polymerase [16] |

Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) is a critical component of every Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) master mix. It is not a passive ingredient but an essential cofactor that directly enables the enzymatic activity of DNA polymerase [20]. In its absence, the polymerase enzyme remains largely inactive, and DNA amplification fails to occur. The Mg²⁺ ion facilitates the formation of the catalytically active structure of the DNA polymerase enzyme and is directly involved in the chemical reaction of DNA synthesis [20]. Beyond its role as a cofactor, MgCl₂ also critically influences the reaction's stringency and specificity by stabilizing the double-stranded DNA structure and affecting the melting temperature (Tm) of the primers, thereby guiding the specificity of primer annealing [21]. Consequently, the precise concentration of this cofactor is one of the most common and vital parameters requiring optimization to achieve efficient and specific amplification of any target DNA template.

Core Functions and Mechanisms: How MgCl₂ Governs PCR Efficiency

The magnesium ion (Mg²⁺) from MgCl₂ performs two non-redundant, essential functions during the PCR process.

Cofactor for DNA Polymerase: The Mg²⁺ ion is a fundamental part of the DNA polymerase's active site. During the extension phase of PCR, the ion binds to a deoxynucleotidetriphosphate (dNTP) at its alpha phosphate group. This binding event is crucial as it facilitates the removal of the beta and gamma phosphates, allowing the resulting dNMP to form a phosphodiester bond with the 3' hydroxyl group of the growing DNA chain. This catalytic role makes Mg²⁺ indispensable for the DNA synthesis activity of the polymerase enzyme [20].

Modulator of Nucleic Acid Stability: Mg²⁺ influences the physical interaction between the primer and the template DNA. It binds to the negatively charged phosphate backbone of the DNA, effectively reducing the electrostatic repulsion between the two complementary DNA strands. This action increases the stability of the primer-template duplex, which is experimentally observed as an increase in the primer's melting temperature (Tm). A meta-analysis of PCR optimization studies quantified this relationship, showing that within the common working range, every 0.5 mM increase in MgCl₂ concentration raises the DNA melting temperature by approximately 1.2 °C [22] [23]. This dual role makes MgCl₂ a master regulator of PCR success, impacting both enzyme kinetics and hybridization thermodynamics.

Optimization Protocol: A Systematic Approach to Defining MgCl₂ Concentration

Optimizing MgCl₂ concentration is a fundamental step in developing a robust PCR assay. The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for empirically determining the ideal concentration for any specific reaction.

Materials and Reagents

- Template DNA: Purified genomic DNA, plasmid, or cDNA.

- Primers: Forward and reverse primers, resuspended in sterile water or TE buffer.

- PCR Master Mix Components: 10X PCR Buffer (often supplied Mg²⁺-free), dNTP Mix (e.g., 10 mM), MgCl₂ stock solution (e.g., 25 mM or 50 mM), Thermostable DNA Polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase), Nuclease-free Sterile Water.

- Equipment: Thermal Cycler, Microcentrifuge Tubes and PCR Tubes, Micropipettes and Sterile Tips, Ice Bucket.

Experimental Procedure

This procedure outlines setting up a MgCl₂ titration series to identify the optimal concentration.

Step 1: Prepare a Master Mix To minimize pipetting error and ensure reaction uniformity, create a master mix containing all components except the MgCl₂ and the template DNA. Calculate volumes for one more reaction than needed to account for pipetting loss. The table below outlines the components for a single 50 µL reaction.

Table 1: Master Mix Components for MgCl₂ Optimization

| Component | Final Concentration | Example Volume per 50 µL Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| 10X PCR Buffer (Mg²⁺-free) | 1X | 5 µL |

| dNTP Mix (10 mM total) | 200 µM (each) | 1 µL |

| Forward Primer (20 µM) | 0.2 - 1 µM | 0.5 - 2.5 µL |

| Reverse Primer (20 µM) | 0.2 - 1 µM | 0.5 - 2.5 µL |

| DNA Polymerase (e.g., 5 U/µL) | 0.5 - 2.5 U/50 µL | 0.1 - 0.5 µL |

| Nuclease-free Water | Q.S. to 50 µL | Variable |

| Template DNA | To be added separately | X µL |

Step 2: Set Up the Titration Series Aliquot the master mix into individual PCR tubes. Then, add a different volume of the MgCl₂ stock solution to each tube to create a concentration gradient. A standard range is from 0.5 mM to 5.0 mM. Finally, add the template DNA to each tube. Include a negative control (no template DNA) for one of the MgCl₂ concentrations.

Table 2: Example MgCl₂ Titration Setup for a 50 µL Reaction

| Tube | Master Mix (µL) | MgCl₂ (25 mM Stock) (µL) | Template DNA (µL) | Final [MgCl₂] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45 - X | 0.0 | X | 0.0 mM |

| 2 | 45 - X | 1.0 | X | 0.5 mM |

| 3 | 45 - X | 2.0 | X | 1.0 mM |

| 4 | 45 - X | 3.0 | X | 1.5 mM |

| 5 | 45 - X | 4.0 | X | 2.0 mM |

| 6 | 45 - X | 5.0 | X | 2.5 mM |

| 7 | 45 - X | 6.0 | X | 3.0 mM |

| 8 | 45 - X | 7.0 | X | 3.5 mM |

| 9 | 45 - X | 8.0 | X | 4.0 mM |

| 10 | 45 - X | 9.0 | X | 4.5 mM |

| 11 | 45 - X | 10.0 | X | 5.0 mM |

Step 3: Execute PCR Amplification Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run the appropriate PCR protocol. The cycling conditions will be specific to your primer set and template, but a standard three-step protocol is used.

Step 4: Analyze the Results After amplification, analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. The optimal MgCl₂ concentration will be the one that yields a single, intense band of the expected size with minimal to no background smearing or non-specific bands.

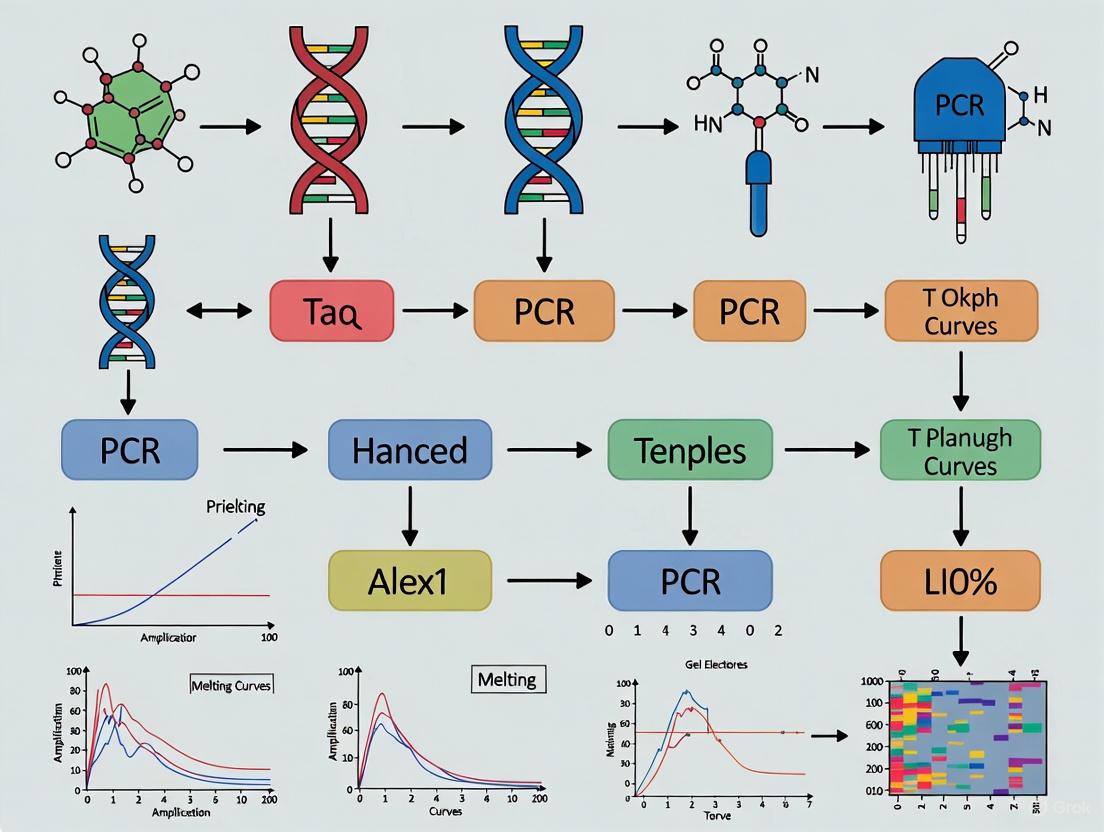

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for MgCl₂ optimization.

Quantitative Data and Troubleshooting Guide

Optimal Concentration Ranges and Effects

The optimal concentration of MgCl₂ is template- and primer-specific, but general ranges and their effects are well-established. The following table synthesizes quantitative data from multiple studies.

Table 3: Effects of MgCl₂ Concentration on PCR Outcomes

| MgCl₂ Status | Typical Concentration Range | Observed Effect on PCR | Gel Electrophoresis Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Too Low | < 1.0 - 1.5 mM | Primer fails to bind efficiently; low or no DNA yield due to insufficient DNA polymerase activity [20] [21]. | Faint or absent target band. |

| Optimal | 1.5 - 4.0 mM | Specific amplification with high yield. This range suits most templates; a meta-analysis found 1.5-3.0 mM optimal for standard templates [22] [23] [21]. | Single, intense band of expected size. |

| Too High | > 4.0 mM | Non-specific primer binding; increased error rate (lowered fidelity) of DNA polymerase [7] [21]. | Multiple bands, smearing, or primer-dimers. |

Advanced Troubleshooting FAQs

This section addresses specific experimental challenges related to MgCl₂.

FAQ 1: My PCR yield is low or non-existent. Could MgCl₂ be the cause? Yes, insufficient Mg²⁺ is a common cause of PCR failure.

- Possible Cause: The MgCl₂ concentration is too low, or its availability is reduced. Mg²⁺ ions can be sequestered by other reaction components, notably dNTPs and chelating agents like EDTA (often present in DNA template storage buffers) [7] [21].

- Solutions:

- Systematically Increase MgCl₂: Perform a titration experiment as described in Section 3, testing concentrations from 1.0 mM to 5.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments [24].

- Account for Chelators: If your DNA template is in TE buffer (containing EDTA) or your dNTP mix is at an atypically high concentration, you will need to add extra MgCl₂ to compensate for the chelated ions. A major change in dNTP concentration requires a corresponding change in MgCl₂ [7] [21].

- Check Template Purity: Re-purify the template DNA if you suspect carryover of PCR inhibitors that might bind Mg²⁺ [7].

FAQ 2: My reaction produces multiple non-specific bands. How can MgCl₂ help? Excessive MgCl₂ reduces reaction stringency, leading to spurious amplification.

- Possible Cause: The MgCl₂ concentration is too high. This stabilizes even weak, non-specific primer-template interactions, allowing primers to bind to incorrect sites on the DNA template [7] [21].

- Solutions:

- Decrease MgCl₂ Concentration: Titrate down the MgCl₂ concentration in 0.2 - 0.5 mM increments. Lowering Mg²⁺ increases stringency, requiring more perfect base pairing for primer annealing [24] [21].

- Combine with Annealing Temperature Optimization: Simultaneously, try increasing the annealing temperature by 1-2°C increments. Using a thermal cycler with a gradient function is highly recommended for this [7].

- Use Hot-Start Polymerases: Switch to a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation that can occur during reaction setup, which can be exacerbated by high Mg²⁺ levels [7] [24].

FAQ 3: How do I optimize MgCl₂ for challenging templates like GC-rich sequences? Complex templates have unique requirements.

- Background: Genomic DNA and GC-rich templates (which form stable secondary structures) generally require higher optimal MgCl₂ concentrations than simple plasmids [22] [23]. The increased Mg²⁺ helps destabilize these structures and stabilizes the DNA polymerase on a more difficult template.

- Protocol Adjustment:

- Start Higher: Begin your MgCl₂ titration at a higher baseline, for example, from 2.0 mM to 6.0 mM.

- Use Enhancers: Incorporate PCR enhancers like DMSO (1-10%), formamide (1.25-10%), or betaine (0.5 M to 2.5 M). These additives help denature GC-rich structures. Note that some enhancers can affect primer binding, so you may need to re-optimize the annealing temperature and potentially increase the amount of DNA polymerase [5] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for PCR and MgCl₂ Optimization

A successful PCR experiment relies on a suite of carefully selected reagents. The following table details key materials and their functions, with a special emphasis on components that interact with MgCl₂.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PCR Optimization

| Reagent | Typical Final Concentration | Critical Function | Interaction with MgCl₂ |

|---|---|---|---|

| MgCl₂ | 1.5 - 4.0 mM (standard) | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase; stabilizes nucleic acid duplexes [5] [20]. | The central parameter for optimization. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | 0.5 - 2.5 U/50 µL reaction | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands. | Absolutely requires Mg²⁺ for activity. Fidelity can be reduced by excess Mg²⁺ [7]. |

| dNTPs (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) | 40 - 200 µM (each) | The building blocks for new DNA synthesis. | dNTPs chelate Mg²⁺ ions. A major change in dNTP concentration necessitates a proportional adjustment of MgCl₂ [21]. |

| Primers | 0.1 - 1.0 µM (each) | Short oligonucleotides that define the start and end of the target sequence. | Their annealing stability (Tm) is directly increased by Mg²⁺ [22]. |

| PCR Buffer | 1X | Provides optimal pH and salt conditions (e.g., Tris-HCl, KCl). | Often supplied with or without MgCl₂. KCl concentration can influence the effective stringency and may require MgCl₂ re-optimization [5] [21]. |

| Additives (e.g., DMSO, Betaine) | Varies (e.g., DMSO 1-10%) | Assist in denaturing complex DNA secondary structures (GC-rich targets). | Can alter the effective Mg²⁺ requirement. Optimization is often needed when adding them [5] [7]. |

Diagram 2: Key interactions of Mg²⁺ with core PCR components.

Within the context of a broader thesis on PCR troubleshooting, the dynamics of magnesium chloride concentration emerge as a foundational element. Moving beyond a simple "one-size-fits-all" recipe, a deep understanding of Mg²⁺'s dual role as an enzymatic cofactor and a modulator of DNA stability is what separates inefficient reactions from robust, publication-grade assays. The quantitative relationships and systematic protocols provided here offer a clear pathway for researchers to rationally optimize this essential cofactor. By mastering the careful titration of MgCl₂ and understanding its interactions with other reagents, scientists and drug development professionals can effectively overcome a significant majority of PCR-related challenges, ensuring specificity, efficiency, and success in their genetic analyses.

The following table consolidates the key numerical parameters for designing effective PCR primers, as established by leading molecular biology resources.

| Design Parameter | Optimal or Accepted Range | Key Considerations & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 nucleotides (nt) [25] [26] [27] | Shorter primers (18-24 nt) bind more efficiently [28], while longer primers (25-30 nt) increase specificity for complex templates (e.g., genomic DNA) [25]. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [25] [26] [29] | Maintains a balance in duplex stability. Content below 40% may require longer primers for optimal Tm, while >60% increases risk of non-specific binding [25] [28]. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 50–75°C [25] [26]; Optimal: 60–64°C [30] | Primer pairs should have Tms within 2–5°C of each other for simultaneous and efficient annealing [25] [30] [28]. |

| GC Clamp | At least 2 G or C bases in the last 5 bases at the 3' end [26] [31] | The stronger hydrogen bonding of G and C bases stabilizes the primer-template binding at the critical point where DNA polymerase initiates synthesis [26] [28]. Avoid more than 3 G/Cs in this region [29]. |

| Annealing Temperature (Ta) | Typically 3–10°C below the primer Tm [27] [31] | The optimal Ta can be calculated using formulas such as Ta = 0.3 x Tm(primer) + 0.7 Tm(product) – 14.9 [29] [31] and should be determined empirically [32]. |

Experimental Protocol: Primer Design and Validation Workflow

This detailed methodology outlines the key steps for designing and experimentally validating PCR primers.

Step 1: In Silico Primer Design

- Sequence Selection: Identify a unique template sequence for your target amplicon. For qPCR or reverse transcription PCR, design primers to span an exon-exon junction to avoid genomic DNA amplification [27] [30].

- Parameter Application: Using primer design software, apply the quantitative parameters from the table above. Ensure the amplicon length is appropriate for your application (e.g., ~100 bp for qPCR, ~500 bp for standard PCR) [29].

- Specificity Check: Perform an in silico specificity check using a tool like NCBI BLAST to confirm your primers are unique to the intended target and avoid regions of cross-homology [29] [30] [31].

Step 2: Secondary Structure Analysis

Before ordering primers, analyze them using oligonucleotide analysis tools (e.g., OligoAnalyzer Tool) [30] to check for:

- Hairpins: Intramolecular folding. Avoid 3' end hairpins with ΔG < -2 kcal/mol and internal hairpins with ΔG < -3 kcal/mol [29].

- Self-Dimers and Cross-Dimers: Intermolecular binding between identical primers or the forward/reverse pair. The ΔG of any dimer should be weaker (more positive) than -9.0 kcal/mol [30]. Dimers at the 3' ends are particularly detrimental [31].

Step 3: Empirical Validation and Optimization

- Annealing Temperature Gradient: Upon receipt of synthesized primers, perform a PCR using an annealing temperature gradient, starting at approximately 5°C below the calculated Tm of your primers [32]. This is the most effective way to determine the optimal Ta for specificity and yield [31].

- Primer Concentration Titration: If amplification efficiency remains suboptimal, titrate the primer concentration within the recommended range of 0.05–1.0 µM [25] [27]. For many applications, 0.2 µM is sufficient [27].

The logical relationship between design principles, common pitfalls, and experimental outcomes is summarized in the following workflow.

PCR Primer Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: My PCR reaction shows no product or a very faint band. What are the primary primer-related causes?

- Annealing Temperature is Too High: If the Ta exceeds the primer Tm, primers cannot bind to the template. Solution: Perform a temperature gradient PCR, starting at 5°C below the calculated Tm of your primers [32] [31].

- Poor Primer Design or Specificity: Primers may not match the target sequence. Solution: Verify primer sequence complementarity to the template. Check for single-base mismatches, especially at the 3' end [32] [27].

- Insufficient Primer Concentration: Typically, a final concentration of 0.1–1.0 µM is used. Solution: Ensure primers are resuspended correctly and use a concentration within, or titrate, this range [25] [32] [27].

Q2: I get multiple bands or the wrong size product. How can I improve specificity?

- Annealing Temperature is Too Low: A low Ta permits primers to bind to non-specific, partially homologous sequences. Solution: Incrementally increase the annealing temperature. Use the highest Ta that gives a robust, specific product [32].

- Primers Have Low Melting Temperature or Poor GC Clamp: This reduces binding specificity. Solution: Redesign primers to have a Tm of at least 60°C and include a GC clamp (G or C at the 3' end) for more stable binding [26] [30] [31].

- Mispriming: Solution: Use software to check for complementary regions within the template and avoid primers with long runs of a single base or dinucleotide repeats [32] [31].

Q3: How can I prevent primer-dimer formation?

- Check for Complementarity: Avoid complementarity, especially in the 2–3 bases at the 3' ends of the primer pairs [27]. Use software tools to screen for self-dimers and cross-dimers [30].

- Optimize Reaction Conditions: Solution: Use hot-start polymerase to prevent premature replication during reaction setup [32]. Ensure primer concentration is not excessively high [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and their functions for successful PCR setup and troubleshooting.

| Reagent or Material | Function in PCR | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5, Phusion) | Catalyzes DNA synthesis with very low error rates. | Essential for cloning or sequencing applications to avoid sequence errors in the final amplicon [32]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Polymerase is inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific amplification during reaction setup. | Critical for improving specificity and reducing primer-dimer formation, especially in multiplex PCR [32]. |

| GC Enhancer / Additives | Additives that disrupt secondary structures in GC-rich templates. | Required for efficient amplification of GC-rich targets (>60%). Often included in specialized buffer systems [32]. |

| dNTP Mix | The building blocks (A, dT, G, C) for DNA synthesis. | Use balanced concentrations of each dNTP. Unbalanced mixes can reduce polymerase fidelity and amplification efficiency [32]. |

| Template DNA | The target DNA sequence to be amplified. | Quality and quantity are critical. For genomic DNA, use 1 ng–1 µg per 50 µL reaction. Poor quality template is a common cause of PCR failure [32]. |

Advanced PCR Methods and Techniques for Challenging Applications

Conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a fundamental technique in molecular biology, but it often faces challenges with specificity. A significant issue is that DNA polymerases, including thermostable varieties, retain some enzymatic activity at room temperature [33] [34]. When reaction mixtures are prepared at lower temperatures, this can lead to nonspecific amplification, such as primer-dimers and misprimed sequences, which drastically impact PCR performance by reducing target yield and sensitivity [35].

Hot-Start PCR is a modified technique designed to overcome these limitations by inhibiting DNA polymerase activity during reaction setup. The polymerase is kept inactive until the first high-temperature denaturation step, which prevents the extension of nonspecific primers and primer-dimers that form at lower temperatures [33] [34]. This results in increased specificity, higher yield of the desired product, and more reliable results for downstream applications [35].

How Hot-Start Technology Works

Hot-Start PCR employs various mechanisms to reversibly inactivate the DNA polymerase or separate essential reaction components until a high-temperature activation step is reached. The table below summarizes the common methods and their key characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Hot-Start Technologies

| Method | Mechanism of Action | Activation Requirement | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-based [35] [36] | A neutralizing monoclonal antibody binds to the polymerase's active site, blocking activity. | Initial denaturation (e.g., 95°C for 2-5 min) denatures the antibody. | Short activation time; animal-origin components; full enzyme activity restored [35]. |

| Chemical Modification [35] | Polymerase is covalently modified with chemical groups that block activity. | Extended pre-incubation at high temperature (often >10 min). | Stringent inhibition; longer activation time; can affect long amplicons (>3 kb) [35]. |

| Affibody/Aptamer-based [35] | Engineered peptides (Affibody) or oligonucleotides (Aptamer) bind and inhibit the polymerase. | Initial denaturation step. | Short activation time; animal-free; may be less stringent than antibody methods [35]. |

| Physical Separation [34] | A wax barrier physically separates polymerase from other reaction components. | High temperature melts the wax, allowing components to mix. | Requires no enzyme modification; adds a procedural step. |

| Controlled Magnesium [34] | Magnesium (a essential cofactor) is precipitated and unavailable. | High temperature during thermal cycling dissolves the precipitate. | Magnesium becomes available automatically as the reaction heats. |

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and logic of a typical Hot-Start PCR process, contrasting it with conventional PCR.

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Common PCR Issues

This section addresses frequent problems in PCR experiments and how Hot-Start methods and other optimization strategies can provide solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common PCR Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Hot-Start & Optimization Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No Product or Weak Yield | • Low template quality/quantity [37] [7]• Suboptimal cycling conditions [7]• Insufficient Mg²⁺ [7] | • Use high-quality, intact DNA [37] [7]. For genomic DNA, use 10-1000 ng [5].• Ensure full activation of hot-start polymerase with adequate initial denaturation [33].• Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration (e.g., 0.5-5.0 mM) [5] [37] [7]. |

| Nonspecific Bands/Smearing | • Primer misprinting at low temps [35] [34]• Low annealing temperature [38] [7]• Excess enzyme, primers, or Mg²⁺ [7] | • Use a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent pre-cycling amplification [35] [33].• Increase annealing temperature [38] [7]. Use a gradient cycler to find the optimum [7].• Optimize primer concentration (typically 0.1-1 μM) [7] and reduce primer concentration if too high [38]. |

| Primer-Dimer Formation [38] | • High 3'-end complementarity between primers• High primer concentration• Polymerase activity during setup | • Use a hot-start DNA polymerase—this is one of the most effective solutions [35] [38].• Redesign primers to minimize 3' complementarity [5] [38].• Lower primer concentration and increase annealing temperature [38]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does Hot-Start PCR specifically prevent primer-dimer formation? Primer-dimers primarily form when primers interact and are extended by the polymerase at the low temperatures present during reaction setup [38]. Hot-Start polymerases are inactive at these temperatures. By the time the enzyme is activated during the initial denaturation step, the reaction temperature is too high for the weak primer-primer interactions to remain stable, thereby preventing their extension [33] [38].

Q2: My Hot-Start PCR still shows nonspecific bands. What should I check first? First, verify that the initial denaturation step was of sufficient duration and temperature to fully activate the enzyme, as per the manufacturer's instructions [33]. Next, optimize the annealing temperature by trying a temperature 3-5°C below the calculated Tm of your primers or using a gradient thermocycler [39] [7]. Also, check that your primer concentrations are not too high (optimize between 0.1-1 μM) [7].

Q3: Can I set up Hot-Start PCR reactions at room temperature? Yes, one of the key benefits of Hot-Start PCR is that it allows for reaction setup at room temperature without compromising specificity, making it suitable for high-throughput automated systems [35]. The inhibitors (antibodies, chemicals, etc.) keep the polymerase inactive until the first heating step [35] [34].

Q4: When is Hot-Start PCR particularly recommended? Hot-Start PCR is highly beneficial in the following scenarios: when amplifying low-copy-number targets, when using complex templates (e.g., genomic DNA), when multiple primer pairs are used in a single reaction (multiplex PCR), and for all diagnostic or quantitative applications where high specificity and sensitivity are critical [35] [34].

Essential Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standard Hot-Start PCR Setup

This protocol provides a generalized method for setting up a Hot-Start PCR reaction. Always refer to the specific instructions for your chosen polymerase.

Prepare Reaction Mixture on Ice: Thaw all reagents (except template DNA) and mix them on ice. A typical 50 μL reaction may contain [5]:

- Sterile distilled water (Q.S. to 50 μL)

- 5 μL of 10X PCR buffer

- 1 μL of 10 mM dNTP mix (final 200 μM each)

- 1 μL of each primer (20 μM stock, final 0.4 μM)

- 0.5-2.5 units of Hot-Start DNA Polymerase

- Template DNA (e.g., 1-1000 ng, depending on source [5])

Run Thermal Cycler Program:

- Initial Denaturation/Activation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes (duration depends on hot-start method; see Table 1) [35] [33].

- Amplification (25-35 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 15-30 seconds.

- Anneal: 55-65°C for 15-30 seconds (optimize for your primers).

- Extend: 72°C for 60 seconds per 1 kb of amplicon [39].

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C ∞.

Protocol 2: Touchdown PCR for Enhanced Specificity

Touchdown PCR is an excellent complementary technique to Hot-Start for increasing specificity, especially with suboptimal primer pairs [39].

- Set up the reaction as in Protocol 1 using your Hot-Start polymerase.

- Program the thermal cycler to start with an annealing temperature (Ta) 5-10°C above the calculated Tm of your primers.

- Over the next 10-15 cycles, decrease the annealing temperature by 1°C per cycle until it reaches the final, calculated Ta.

- Continue with an additional 15-25 cycles at this final Ta.

This method ensures that the first, most specific amplifications occur when the Ta is high, creating a pool of the correct product that out-competes nonspecific targets in later, less stringent cycles [39].

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Hot-Start PCR and Troubleshooting

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | The core component; prevents nonspecific amplification during reaction setup [35] [33]. | Choose based on need for speed, fidelity, and amplicon length (e.g., antibody-based for quick activation) [35]. |

| Primers | Specifically anneal to the target DNA sequence for amplification. | Design with 40-60% GC content, Tm of 52-65°C, and avoid 3' end complementarity [5]. Use tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST. |

| dNTPs | The building blocks (A, dTTP, dCTP, dGTP) for new DNA synthesis. | Use balanced concentrations (typically 50-200 μM each). Excess reduces specificity; too little reduces yield [7]. |

| Magnesium (Mg²⁺) | An essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity [34]. | Critical optimization parameter. Start at 1.5 mM and titrate (0.5 mM steps) from 0.5-5.0 mM [5] [37] [7]. |

| PCR Additives/Enhancers | Help amplify difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich regions). | DMSO (1-10%), formamide (1.25-10%), or Betaine (0.5-2.5 M) can help denature secondary structures [5] [37]. |

Integrating Hot-Start PCR into your molecular biology workflow is a powerful strategy for mitigating the pervasive challenges of nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation. By understanding the different mechanisms of hot-start technologies and applying the targeted troubleshooting and optimization protocols outlined in this guide, researchers can achieve significantly improved PCR results, with higher yields, greater sensitivity, and enhanced reliability for downstream applications.

Core Concept and Principle of Touchdown PCR

Touchdown (TD) PCR is a modified polymerase chain reaction technique designed to enhance specificity and sensitivity, particularly for challenging targets. It systematically addresses the common problem of non-specific amplification, where primers bind to non-target sequences, leading to unwanted products like primer-dimers or false-positive bands on a gel. [40]

The core principle involves starting with an annealing temperature higher than the calculated melting temperature ((Tm)) of the primer pair. Over successive cycles, this annealing temperature is progressively lowered—like an airplane touching down—until it reaches the optimal, more permissive (Tm). This initial high-stringency phase favors the accumulation of only the most perfectly matched primer-template complexes. The desired amplicons, amplified in these early cycles, then have an exponential advantage and outcompete non-specific products in the later, lower-stringency cycles. [40] [41]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: When should I use touchdown PCR instead of standard PCR? Use touchdown PCR when you encounter persistent non-specific amplification or smeared bands, when amplifying difficult templates (e.g., those with complex secondary structures), when your primer pair has suboptimal characteristics, or when you need to rapidly optimize a PCR without lengthy temperature gradient tests. [40] [41]

FAQ 2: My touchdown PCR still shows non-specific bands. What can I do? This is a common issue. Please refer to the troubleshooting table below for a systematic guide to resolving this and other problems.

FAQ 3: How do I calculate the starting and ending annealing temperatures? Begin by calculating the (Tm) of your primers. A simple formula is: (Tm = 2(A+T) + 4(G+C)), where A, T, G, and C are the number of each base in the primer. [39] The initial annealing temperature in the touchdown phase should be set approximately 10°C above this calculated (Tm). The temperature is then decreased by 1°C per cycle until the final, target (Tm) is reached. [40] For example, if your primer (T_m) is 55°C, you would start at ~65°C and decrease by 1°C per cycle for 10 cycles until you reach 55°C.

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common Touchdown PCR Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No Product [42] | Overly stringent initial temperature; insufficient cycles; low template quality/quantity. | Verify template integrity and concentration [7] [43]; Increase number of cycles (up to 40) [42]; Ensure final annealing temperature is not too high; Add an extra denaturation cycle for difficult templates [40]. |

| Non-specific Bands or Smearing [40] [42] | Insufficient stringency; too many cycles; high primer concentration. | Increase the initial touchdown temperature [40]; Reduce total cycle number (keep below 35) [40]; Lower primer concentration (0.1-0.5 µM) [43] [39]; Use a hot-start polymerase [40] [7]. |

| Primer-Dimer Formation [44] | Primer 3'-end complementarity; low annealing temperature; excess primers. | Redesign primers to avoid 3'-end complementarity [45]; Optimize primer concentration; Use a hot-start setup to prevent activity at room temperature [40] [45]. |

| Low Yield | Poor primer efficiency; inefficient polymerase; suboptimal Mg²⁺ concentration. | Check primer design (e.g., 40-60% GC content) [45]; Use a high-performance polymerase master mix [43]; Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration (e.g., 1.5-2.0 mM for Taq) [39]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol is adapted from the method described in Nature Protocols by Korbie and Mattick (2008). [40] [41]

Step-by-Step Touchdown PCR Procedure

Reaction Setup

- Assemble all components on ice to prevent non-specific priming. [40]

- Use a hot-start DNA polymerase to further minimize pre-cycling activity. [40] [7]

- A sample 50 µL reaction mixture is suggested below. Always follow the specific manufacturer's instructions for your polymerase.

Table 2: Recommended Reaction Setup

Component Final Concentration Volume (for 50 µL) 2X PCR Master Mix* 1X 25 µL Forward Primer (10 µM) 0.4-0.5 µM 2 µL Reverse Primer (10 µM) 0.4-0.5 µM 2 µL Template DNA Variable x µL Nuclease-free Water - Up to 50 µL *Master Mix typically contains buffer, dNTPs, Mg²⁺, and hot-start polymerase. *Use ~10-40 ng genomic DNA, 1-10 ng plasmid DNA, or 1-5 µL cDNA. [43] [39]*

Thermal Cycling Conditions

- Program your thermocycler using the parameters below. This example is based on a primer (T_m) of 57°C.

Table 3: Example Thermal Cycler Program for Touchdown PCR

Step Temperature Time Cycles Initial Denaturation 95°C 3-5 min 1 Touchdown Phase (Stage 1) 10-15 > Denature 95°C 20-30 sec > Anneal Start: (T_m)+10°C (e.g., 67°C)Decrease: -1°C/cycle 30-45 sec > Extend 72°C 30-60 sec/kb Standard Amplification (Stage 2) 20-25 > Denature 95°C 20-30 sec > Anneal Use final temp from Stage 1 (e.g., 57°C) 30-45 sec > Extend 72°C 30-60 sec/kb Final Extension 72°C 5-10 min 1 Hold 4-10°C ∞ 1

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The success of touchdown PCR relies on high-quality reagents. The following table lists essential materials and their critical functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Touchdown PCR

| Item | Function & Importance | Recommendations & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Critical for specificity. Remains inactive at room temperature, preventing mispriming and primer-dimer formation before cycling begins. [40] [7] | Choose enzymes with high processivity for long or complex targets. For high-fidelity needs (e.g., cloning), use proofreading enzymes like Pfu. [37] [45] |

| Optimized PCR Buffer | Provides the optimal chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) for polymerase activity and stability. | Use the buffer supplied with your polymerase. Be aware that Mg²⁺ concentration (a common buffer component) is crucial and may require optimization between 1.5-2.5 mM. [7] [39] |

| High-Purity Primers | Specifically designed oligonucleotides that define the target sequence. | Aliquot after resuspension to avoid freeze-thaw degradation [7]. Design with 40-60% GC content and avoid 3'-end complementarity to prevent primer-dimers. [45] |

| PCR Additives | Enhances amplification efficiency for difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich sequences). [40] [7] | DMSO, formamide, or betaine can help denature secondary structures. Use at the lowest effective concentration as they can inhibit the polymerase. [7] [37] |

Amplifying long, GC-rich DNA templates presents significant challenges in molecular biology, often leading to reaction failure, non-specific products, or truncated amplicons. These difficult templates are common in promoter regions of housekeeping and tumor suppressor genes, making their reliable amplification crucial for genetic research and drug development. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting strategies and optimized protocols to overcome the unique obstacles posed by complex templates, enabling researchers to achieve specific, efficient amplification of even the most challenging targets.

Understanding the Challenges

Why are GC-rich and long templates problematic? GC-rich DNA sequences (typically ≥60% GC content) exhibit greater thermal stability due to three hydrogen bonds in G-C base pairs versus two in A-T pairs, requiring higher denaturation temperatures [46]. This increased stability promotes formation of stable secondary structures like hairpin loops that block polymerase progression [46] [47]. Additionally, GC-rich regions resist complete denaturation, preventing primer access and causing inefficient amplification [48].

Long-range PCR (amplifying products >5 kb) demands polymerases with high processivity and proofreading capability. Standard Taq polymerase lacks 3'→5' exonuclease activity, resulting in higher error rates and inability to efficiently amplify long fragments [49]. The combination of length and high GC content compounds these difficulties, requiring specialized approaches for successful amplification.

Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ: My PCR results show smearing or multiple bands. What should I do?

This indicates non-specific amplification, commonly caused by insufficient primer annealing stringency [5] [37].

- Increase annealing temperature: Raise temperature by 2-3°C increments to improve specificity [48]

- Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration: Test 0.5 mM increments between 1.0-4.0 mM [48]

- Shorten annealing times: For GC-rich templates, optimal annealing may be as brief as 3-6 seconds [47]

- Use hot-start polymerase: Prevents non-specific priming during reaction setup [49]

FAQ: I get no amplification product with GC-rich templates. How can I improve yield?

This results from incomplete denaturation or polymerase stalling at secondary structures [46].

- Add destabilizing agents: Include DMSO (1-10%), formamide (1.25-10%), or betaine (0.5-2.5 M) to reduce secondary structure formation [5] [49]

- Use specialized polymerases: Select enzymes specifically designed for GC-rich amplification [50] [48]

- Increase denaturation temperature: Raise to 95-98°C, but limit time to prevent polymerase damage [46]

- Incorporate 7-deaza-dGTP: A dGTP analog that improves amplification yield of GC-rich regions [47]

FAQ: How can I improve success with long-range PCR (>10 kb)?

Long amplification requires optimized conditions to maintain polymerase processivity [51].

- Use polymerase mixes: Combine Taq with proofreading enzymes (Pfu, KOD) for fidelity and processivity [49]

- Extend extension times: Calculate based on polymerase speed (e.g., 1-2 minutes per kb for most high-fidelity polymerases)

- Optimize template quality: Ensure high-molecular-weight, pure DNA without inhibitors [37]

- Apply two-step PCR: Combine annealing and extension steps under a single set of conditions [50]

FAQ: How do I calculate the correct annealing temperature?

- Determine primer Tm: Use the formula Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T) or computational tools [5]

- Set initial Ta: Start 3-5°C below the calculated Tm of your primers [48]

- Apply gradient PCR: Test a temperature range (typically 55-72°C) to identify optimal conditions [49]

- Use online calculators: NEB Tm Calculator incorporates enzyme and buffer specifics [48]

Optimization Tables

Polymerase Selection Guide

| Polymerase Type | Key Features | Error Rate | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Taq | No proofreading, fast | ~1 x 10⁻⁵ | Routine screening, genotyping |

| High-Fidelity (Pfu, KOD) | 3'→5' exonuclease activity | ~1 x 10⁻⁶ | Cloning, sequencing, complex templates |

| Hybrid Systems | Taq + proofreading enzyme | ~1 x 10⁻⁷ | Long-range, high-GC amplification |

| Specialty GC-Rich | Enhanced secondary structure resolution | Varies | GC-rich promoters, difficult amplicons |

Buffer Additives and Their Functions

| Additive | Recommended Concentration | Mechanism of Action | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | 2-10% | Disrupts secondary structures, lowers Tm | Can inhibit polymerase at >10% |

| Betaine | 0.5-2.5 M | Homogenizes DNA thermal stability | Compatible with most polymerases |

| Formamide | 1.25-10% | Increases primer stringency | Optimize concentration carefully |

| 7-deaza-dGTP | Substitute for dGTP | Reduces secondary structure formation | Poor ethidium bromide staining |

| BSA | 10-100 μg/mL | Binds inhibitors, stabilizes enzymes | Helps with inhibitory samples |

Experimental Protocols

Optimized Protocol for GC-Rich Templates

This protocol has been successfully used to amplify a 660 bp fragment of the human ARX gene (78.72% GC content) from genomic DNA [47].

Reaction Setup:

- Template: 100 ng genomic DNA

- Primers: 0.75 μM each (ARX example: forward 5'-CCAAGGCGTCGAAGTCTG-3', reverse 5'-TCATCTTCTTCGTCCTCCAG-3')

- dNTPs: 200 μM each

- MgSO₄: 4 mM (optimize between 1.0-4.0 mM)

- Polymerase: 0.5 units KOD Hot-Start Polymerase

- Buffer: 1X manufacturer's buffer

- Additives: 11% DMSO (v/v), 400 μg/mL non-acetylated BSA

- Total Volume: 25 μL with sterile water [47]

Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds

- Amplification (35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94°C for 2 seconds

- Annealing: 60°C for 3 seconds (critical for specificity)

- Extension: 72°C for 4 seconds

- Final Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds [47]

Key Optimization Notes:

- Annealing times beyond 10 seconds produced smeared products in ARX amplification [47]

- Optimal annealing temperature was precisely 60°C for this template [47]

- Higher denaturation temperatures (95-98°C) may be needed for extremely GC-rich targets [46]

Long-Range PCR Protocol

Reaction Setup:

- Template: 1-1000 ng DNA (high purity, avoid inhibitors)

- Primers: 0.2-1.0 μM each (Tm within 1-2°C)

- dNTPs: 200-250 μM each

- Mg²⁺: 1.5-2.5 mM (optimize for each template)

- Polymerase: Polymerase mix with proofreading capability (e.g., PrimeSTAR GXL)

- Buffer: Manufacturer's recommended buffer with additives

- Additives: Betaine (1-1.5 M) often beneficial [49]

Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 1-2 minutes

- Amplification (30-35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10-20 seconds

- Annealing: 60-65°C for 15-30 seconds

- Extension: 68°C for 1-2 minutes per kb (adjust based on polymerase speed)

- Final Extension: 68-72°C for 5-10 minutes

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty Polymerases | PrimeSTAR GXL (Takara), Q5 High-Fidelity (NEB), OneTaq GC (NEB) | Optimized for complex templates | PrimeSTAR GXL handles GC-rich targets up to 30 kb [50] |

| GC Enhancers | OneTaq GC Enhancer, Q5 High GC Enhancer | Suppresses secondary structures | Enables amplification up to 80% GC content [48] |

| Additive Kits | DMSO, betaine, formamide, 7-deaza-dGTP | Modifies DNA thermal properties | Test individually and in combination [47] |

| Optimization Tools | Gradient thermal cyclers, Mg²⁺ titration kits | Systematic parameter optimization | Essential for method development |

Systematic Optimization Workflow

The following workflow outlines a logical, step-by-step approach to troubleshooting challenging PCR amplifications:

Key Technical Tips

Primer Design for GC-Rich Templates:

Template Quality Considerations:

Thermal Cycler Adjustments:

Successful amplification of long-range and GC-rich templates requires systematic optimization of multiple parameters. The most critical factors include polymerase selection, annealing time and temperature optimization, Mg²⁺ concentration titration, and strategic use of additives. By following the structured troubleshooting approach outlined in this guide and methodically testing optimization strategies, researchers can overcome the challenges posed by complex templates and achieve reliable, specific amplification for their experimental needs.

Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is an advanced molecular technique that enables the simultaneous amplification of multiple distinct DNA targets in a single reaction tube. This powerful methodology offers significant advantages over conventional single-plex PCR, including increased throughput, reduced reagent costs, conservation of precious sample material, and streamlined assay workflows [53]. The technique has found diverse applications across molecular biology, including infectious disease diagnostics, where it allows for the comprehensive detection of multiple pathogens from a single sample [54] [55], gene expression analysis, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping, and copy number variation (CNV) studies [53].

However, the development of a robust multiplex PCR assay presents considerable technical challenges. The simultaneous presence of multiple primer pairs in a single reaction dramatically increases the complexity of reaction dynamics and the potential for undesirable interactions. Researchers often encounter issues such as false negatives, false positives, uneven amplification efficiency across targets, and the formation of primer-dimers [56]. Success hinges on careful experimental design, meticulous optimization of reaction components and cycling conditions, and thorough validation. This guide addresses these challenges by providing detailed troubleshooting advice and optimized protocols to help researchers achieve efficient and reliable multiplex PCR results.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: I am not getting any amplification for one or more of my targets in the multiplex reaction, even though they work fine in single-plex. What could be causing these false negatives?

False negatives in multiplex PCR can arise from several factors that compromise assay sensitivity [56].

- Cause A: Target Secondary Structure: The formation of stable secondary structures in the DNA template can physically block primer binding sites, preventing primers from annealing and initiating amplification [56].

- Cause B: Primer-Dimer Formation: Primers may anneal to each other due to complementary sequences, particularly at their 3' ends. The polymerase can then extend these hybridized primers, depleting dNTPs and primers, and reducing the resources available for the intended amplification [56] [6].

- Cause C: Primer-Amplicon Interactions: A primer designed for one target might inadvertently bind to and amplify a non-target amplicon from another primer pair in the mix. This can produce shorter, unintended products and deplete reagents [56].

- Cause D: Suboptimal Reaction Conditions: The "one-size-fits-all" conditions from single-plex may not be optimal for the more complex multiplex environment. This includes incorrect annealing temperature, insufficient polymerase, or imbalanced MgCl₂ concentration [6] [57].

Solutions:

- Verify Template Quality and Quantity: Ensure your DNA template is of high quality, free of inhibitors, and used in an appropriate concentration. If inhibitors are suspected, dilute the template or re-purify it [6] [57].

- Optimize Primer Design: Redesign primers to avoid self-complementarity and secondary structures. Use software tools that can solve for coupled equilibria to predict and minimize these interactions [56].

- Re-balance Primer Concentrations: Empirically test different ratios of primer pairs. Some targets may require higher or lower primer concentrations to achieve balanced amplification. For instance, one optimized protocol used a primer ratio of 1:1:1:1.5:1:1 for one Cas subtype [58].

- Optimize PCR Conditions: Systematically adjust the annealing temperature (typically in 2°C increments), increase the number of PCR cycles (e.g., up to 40 cycles), or increase the amount of polymerase and dNTPs [6] [57].

Q2: My multiplex PCR produces unexpected bands or signals not corresponding to my target amplicons. What is causing these false positives and non-specific amplification?

Non-specific amplification occurs when primers bind to unintended regions on the template DNA.