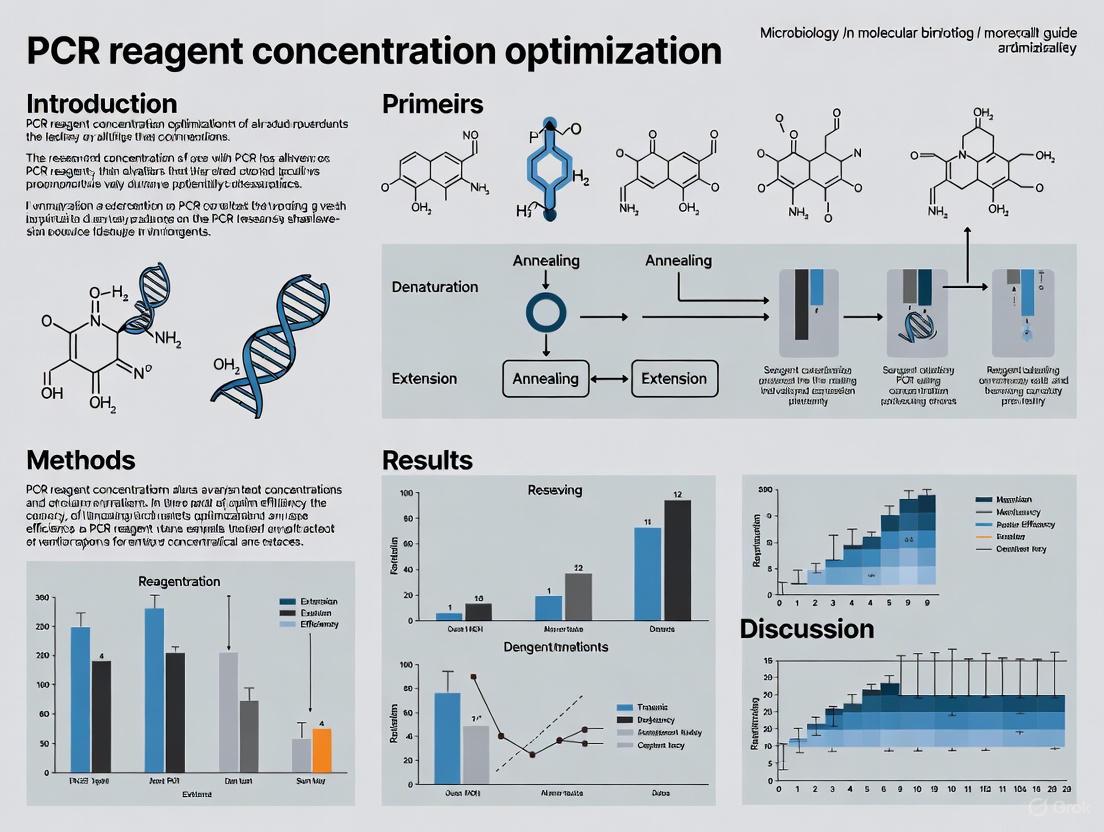

PCR Reagent Concentration Optimization: A Complete Guide for Robust and Reproducible Results

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for optimizing PCR reagent concentrations.

PCR Reagent Concentration Optimization: A Complete Guide for Robust and Reproducible Results

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for optimizing PCR reagent concentrations. It covers the foundational role of each reaction component, presents systematic methodological approaches for fine-tuning concentrations, details advanced troubleshooting strategies for common amplification challenges, and outlines rigorous validation and comparative techniques to ensure assay specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical application, this article serves as an essential resource for achieving reliable PCR performance in diverse research and diagnostic contexts.

The Building Blocks of PCR: Understanding the Role and Rationale of Each Reagent

The template DNA provides the blueprint that the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifies. Its quality, quantity, and source are fundamental to experimental success. Template DNA can be derived from various sources, including genomic DNA (gDNA), complementary DNA (cDNA), and plasmid DNA, each with specific considerations for optimal amplification [1] [2]. Proper management of this critical reagent minimizes amplification failures, reduces nonspecific products, and ensures the reliability of downstream results. This guide details the optimal use of template DNA within the broader context of PCR reagent concentration optimization.

Optimal Template Amounts by Source

Using the correct amount of template DNA is crucial. Insufficient template leads to no product or low yield, while excess template can increase nonspecific amplification and background [1] [3]. The optimal quantity depends on the complexity and source of the DNA.

Table 1: Recommended Template DNA Amounts for a Standard 50 µL PCR Reaction

| Template Source | Recommended Amount | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA | 0.1 - 10 ng [1] [3] | Lower complexity requires less input. ~104 copies of target DNA are often sufficient [3]. |

| Genomic DNA (gDNA) | 1 ng - 1 µg [3]; 5 - 50 ng [1] | Higher complexity requires more input. A series of concentrations may be tested if the optimal amount is unknown [2]. |

| cDNA | 1 - 5 µL of reverse transcription reaction [4] | Amount depends on transcript abundance. May require optimization via dilution series. |

| PCR Amplicon (Re-amplification) | 1 - 5 µL of a 1:10 to 1:100 dilution of the initial reaction [1] | Dilution is necessary to reduce carryover of primers, dNTPs, and salts from the first PCR. |

Assessing Template DNA Quality

Template quality is as important as quantity. Degraded or impure DNA is a common cause of PCR failure.

Quality Assessment Methods

- Spectrophotometry (A260/A280 Ratio): Assesses protein contamination. Pure DNA has a ratio of ~1.8 [5]. Significant deviation may indicate impurities that can inhibit PCR.

- Agarose Gel Electrophoresis: Evaluates DNA integrity and isoform distribution [6] [7]. For plasmid DNA, a high percentage (>80%) of supercoiled DNA is often considered a marker of quality, though this does not always guarantee performance in all applications like in vitro transcription [7]. Genomic DNA should appear as a tight, high-molecular-weight band; smearing indicates degradation.

- Capillary Electrophoresis (CE): Provides higher resolution than agarose gels for detecting fragmentation and quantifying DNA species [7].

- Functionality Testing: The most reliable test is performance in a control PCR reaction with a well-characterized, high-quality template and primers [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for DNA Quality Control

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Handling and Quality Control

| Reagent / Tool | Function |

|---|---|

| TE Buffer (pH 8.0) | Storage buffer for DNA to prevent degradation by nucleases [6]. |

| PCR Clean-up Kits | Purify PCR products to remove salts, enzymes, and unincorporated nucleotides before re-amplification [1] [5]. |

| Ethanol Precipitation | Method to concentrate DNA and remove certain inhibitors like salts [6]. |

| Phenol/Chloroform | Used in traditional extraction protocols to separate DNA from proteins and other cellular components [9]. |

| UDG (Uracil DNA Glycosylase) | Enzyme used in pre-treatment to prevent carryover contamination from previous PCR reactions [1]. |

Source-Specific Template Considerations

Different DNA sources present unique challenges and requirements for successful PCR amplification.

Genomic DNA (gDNA)

gDNA is highly complex. Its isolation must minimize shearing and nicking to ensure integrity [6]. Common inhibitors include phenol, EDTA, heparin, and heme from blood samples [6] [8]. If inhibitors are suspected, dilute the template 10- to 100-fold, or re-purify it using ethanol precipitation or a commercial clean-up kit [5] [8]. For large genomes, ensure an adequate number of target copies are present; nanogram amounts of mammalian gDNA can contain thousands of copies of a single-copy gene.

Plasmid DNA

Plasmids are low-complexity templates, requiring minimal input. They are typically purified in supercoiled, open circular, and linear isoforms. While a high supercoiled percentage is a common quality metric, note that for PCR, the template is denatured, so isoform may be less critical than for other applications like in vitro transcription [7]. Plasmid DNA for PCR is often linearized, but this is not always required [2].

cDNA

cDNA is synthesized from mRNA via reverse transcription. Its quality directly reflects the quality and integrity of the starting mRNA. The abundance of the specific target transcript should guide the amount of cDNA used. For low-abundance targets, more cDNA or additional PCR cycles may be necessary.

Diagram 1: Template DNA source decision guide.

Template DNA Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My PCR shows no product. Could the template be the problem? Yes. Possible template-related causes and solutions include:

- Cause: Insufficient template quantity or degradation [6] [5].

- Solution: Check DNA integrity by gel electrophoresis. Increase the amount of template, or use a fresh, high-quality preparation.

- Cause: Presence of PCR inhibitors [6] [8].

- Solution: Dilute the template to reduce inhibitor concentration. Re-purify the DNA via ethanol precipitation or a commercial clean-up kit. Use a DNA polymerase known for high tolerance to inhibitors.

- Cause: Overly stringent PCR conditions [8].

- Solution: Reduce the annealing temperature in 2°C increments. Increase the number of PCR cycles (up to 40) for low-copy targets.

Q2: I get nonspecific bands or smears. How can I fix this? Nonspecific amplification is often linked to template quality and amount.

- Cause: Excess template DNA [6] [3] [8].

- Solution: Reduce the amount of template by 2- to 5-fold.

- Cause: Impure or degraded template [6].

- Solution: Re-purify the template DNA to remove contaminants and use intact DNA.

- Cause: Low annealing temperature [5] [8].

- Solution: Increase the annealing temperature stepwise. Use a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent activity at room temperature [6].

Q3: My PCR results are inconsistent, even with the same DNA preparation. Why? Inconsistency can stem from several factors:

- Cause: Variable DNA quality post-linearization [7]. For applications requiring linearized DNA (e.g., for in vitro transcription), nicking or low-level degradation not detectable by standard gels can cause variability.

- Solution: Use high-resolution analysis like capillary electrophoresis. Consider next-generation sequencing to detect nicks and damage [7].

- Cause: Non-homogeneous reagents [6].

- Solution: Mix the template stock and the entire PCR reaction thoroughly before cycling to eliminate density gradients.

- Cause: Inconsistent thermocycler block temperature [5].

- Solution: Check the calibration of the heating block.

Q4: How can I prevent contamination of my template DNA? Contamination with foreign DNA, especially previous PCR products (carryover contamination), is a major issue [8].

- Physical Separation: Establish physically separated "pre-PCR" and "post-PCR" areas with dedicated equipment, lab coats, and pipettes [8].

- UDG Treatment: Incorporate dUTP in PCR mixes and treat subsequent reactions with Uracil DNA Glycosylase (UDG) to degrade carryover amplicons [1].

- Workflow: Always include a negative control (no template DNA) to monitor for contamination.

Diagram 2: Template DNA troubleshooting flowchart.

Core Principles of PCR Primer Design

Successful Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) assays depend fundamentally on well-designed primers. Poorly designed primers are a leading cause of non-specific amplification, low yield, and failed experiments. The core parameters—primer length, melting temperature (Tm), and GC content—work in concert to determine the specificity and efficiency of your PCR reaction [10].

Primer length is a primary determinant of specificity. Generally, primers should be 18-30 nucleotides long [11] [12] [13]. Shorter primers within this range (18-24 bases) anneal more efficiently, while longer primers (up to 30 bases) are better for ensuring specificity in complex templates like genomic DNA [11] [12].

The melting temperature (Tm), the temperature at which half of the primer-DNA duplex dissociates, is critical for setting the correct annealing temperature. Primer pairs should have Tms within 1-5°C of each other to ensure both bind to the template simultaneously with similar efficiency [11] [12] [13]. The ideal Tm generally falls between 55-75°C [11] [10] [14].

GC content should be balanced, ideally between 40-60% [11] [10] [12]. This provides stable primer-template binding without promoting secondary structures. A GC clamp—one or more G or C bases at the 3' end—strengthens binding due to stronger hydrogen bonding, but avoid runs of several G or C bases consecutively [12] [15] [14].

3' End Design and Specificity Checks

The 3' end of the primer is the most critical for PCR success. DNA polymerase initiates synthesis from this point, so it must be perfectly complementary to the template to prevent mispriming [12]. Avoid complementarity between the 3' ends of your forward and reverse primers, as this promotes the formation of primer-dimers [11] [14].

Always check for self-complementarity within a primer (which can form hairpins) and cross-complementarity between primers (which can form dimers) [12] [14]. Also, verify primer specificity by running a sequence similarity search (e.g., BLAST) against your template database to ensure it binds only to the intended target [16].

The table below summarizes the key parameters and their optimal ranges for standard PCR primer design.

Table 1: Optimal Ranges for Key Primer Design Parameters

| Parameter | Optimal Range/Guideline | Rationale & Impact of Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 nucleotides [11] [13] [14] | Shorter primers anneal efficiently; longer primers increase specificity. |

| Melting Temp (Tm) | 55–75°C; primers within 1–5°C of each other [11] [10] [13] | Ensures simultaneous binding of both primers to the template. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [11] [10] [13] | Balances stable binding and prevents secondary structures. |

| 3' End Stability | End with a G or C base (GC clamp); avoid 3' complementarity [10] [15] [14] | Ensures efficient extension initiation and prevents primer-dimer formation. |

Troubleshooting Primer-Dimers and Non-Specific Amplification

What is a primer-dimer and how does it form?

A primer-dimer is a small, unintended DNA fragment that forms when primers anneal to each other instead of to the target DNA template [17]. This can happen through:

- Self-dimerization: A single primer contains regions complementary to itself.

- Cross-dimerization: The forward and reverse primers have complementary regions, especially at their 3' ends, and bind to each other [17].

Once primers bind, DNA polymerase extends them, creating a short product that can be amplified efficiently in subsequent cycles, competing with the target amplicon and reducing PCR yield and sensitivity [17].

How can I prevent primer-dimer formation?

The best strategies focus on reducing opportunities for primers to interact with each other.

- Optimize Primer Design: Use design software to check for and minimize inter-primer complementarity. Pay close attention to the 3' ends to ensure they are not complementary [17] [14].

- Lower Primer Concentration: High primer concentration increases the chance of primers meeting and forming dimers. Optimize the final concentration, typically between 0.1–0.5 µM [11] [17] [15].

- Increase Annealing Temperature: Using an annealing temperature that is too low allows primers to bind imperfectly to each other. Increase the temperature incrementally (e.g., in 1–2°C steps) to find the highest possible temperature that still allows specific primer-template binding [17] [10].

- Use a Hot-Start DNA Polymerase: These enzymes are inactive until a high-temperature activation step. This prevents the polymerase from extending misprimed primers or primer-dimers during reaction setup and the initial heating phase [17] [6] [13].

- Increase Denaturation Time: Longer denaturation times help ensure primers bound to each other are fully separated [17].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Primer-Related PCR Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Primer-Dimers | Complementary 3' ends; High primer concentration; Low annealing temperature [17]. | Redesign primers; Lower primer concentration (0.1–0.5 µM); Increase annealing temperature; Use hot-start polymerase [17] [6] [15]. |

| No Amplification | Tm mismatch between primers; Poor 3' end complementarity; Degraded primers [6]. | Redesign primers with closely matched Tms; Ensure perfect 3' end match to template; Aliquot and store primers correctly [11] [6]. |

| Non-Specific Bands/ Smearing | Low annealing temperature; High Mg2+ concentration; Primers binding off-target [10] [6]. | Increase annealing temperature (gradient PCR); Optimize/titrate Mg2+; Check primer specificity (BLAST); Use touchdown PCR [10] [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol 1: Gradient PCR for Annealing Temperature Optimization

The optimal annealing temperature (Ta) is often determined empirically, as it is usually 3–5°C below the calculated Tm of the primers [10] [6].

- Prepare a standard PCR master mix containing all components: buffer, dNTPs, MgCl₂, template DNA, primers, and DNA polymerase.

- Aliquot the mix into multiple PCR tubes or wells.

- Program your thermal cycler with a gradient across the annealing step. Set the gradient to cover a range of about 10°C, centered on the predicted optimal Ta. For example, if the average primer Tm is 60°C, set a gradient from 55°C to 65°C.

- Run the PCR.

- Analyze the results using agarose gel electrophoresis. The optimal Ta is the highest temperature that produces a strong, specific band with the least non-specific product or primer-dimer [10] [6].

Protocol 2: Magnesium Concentration Titration

Magnesium ion (Mg2+) is an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase, and its concentration directly affects enzyme activity, fidelity, and primer annealing [10] [18].

- Prepare a base master mix without Mg2+.

- Aliquot the mix into several tubes.

- Add MgCl₂ or MgSO₄ to each tube to create a series of final concentrations, typically from 0.5 mM to 5.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments. The specific salt used depends on the polymerase [10] [18].

- Run the PCR using the established or optimized annealing temperature.

- Analyze the products by gel electrophoresis. Identify the Mg2+ concentration that yields the highest amount of the correct product with the least background [10].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected workflow for designing and optimizing primers, integrating both in silico checks and wet-lab experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCR Optimization

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Prevents non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by being inactive until a high-temperature activation step [17] [6]. | Essential for complex templates and multiplex PCR. Available in antibody-based or chemically modified forms. |

| Magnesium Salts (MgCl₂/MgSO₄) | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. Concentration affects enzyme processivity, fidelity, and primer annealing [10] [18]. | Must be titrated for each primer-template system. The type of salt (MgCl₂ vs. MgSO₄) can be polymerase-specific [10]. |

| PCR Additives (DMSO, BSA, Betaine) | Assist in amplifying difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich). DMSO disrupts secondary structures; Betaine equalizes Tm [10] [13] [18]. | Use at optimized concentrations (e.g., DMSO at 2-10%). Can inhibit some polymerases if overused [10] [13]. |

| In Silico Primer Design Tools | Software and online platforms to design and analyze primers based on key parameters and specificity checks [12] [16]. | Critical for checking for secondary structures, dimer potential, and off-target binding before synthesis. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the single most important rule for the 3' end of a primer? The 3' end must have perfect complementarity to the target template and should ideally end in a G or C base (a GC clamp) for stable binding. Most critically, the 3' ends of the forward and reverse primers must not be complementary to each other, as this is a primary cause of primer-dimer formation [12] [15] [14].

Q2: My primers have a high Tm (>75°C). Is this a problem? Yes, primers with a Tm higher than 65-75°C can be problematic because they tend to promote secondary annealing and can be difficult to work with standard PCR protocols. It is better to shorten the primer length or adjust the sequence to reduce the Tm into the optimal range [12] [14].

Q3: How can I definitively identify primer-dimer in my gel? Primer-dimers have two key characteristics: 1) Short length, typically below 100 bp, and 2) A smeary or fuzzy appearance rather than a sharp, defined band [17]. Running a no-template control (NTC) is the best way to confirm it; if a product appears in the NTC lane, it is almost certainly a primer-dimer or other artifact, as it formed without any template DNA [17].

Q4: When should I use a two-step PCR protocol instead of a three-step one? Consider a two-step PCR (combining annealing and extension into one step, often at 68°C) when the melting temperature (Tm) of your primers is high and close to the standard extension temperature (e.g., 68-72°C). This protocol is also often recommended for amplifying longer templates (>4 kb) and for some GC-rich targets [18].

The selection of an appropriate DNA polymerase is a critical foundational step in the optimization of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) protocols. The enzyme's properties directly determine the success of experiments in cloning, sequencing, and diagnostic assay development. Four key characteristics—thermostability, fidelity, processivity, and the incorporation of hot-start technology—form the cornerstone of effective polymerase selection, guiding researchers to match the enzyme's capabilities with the specific demands of their experimental and downstream applications [19]. A thorough understanding of these properties, framed within the broader context of PCR reagent concentration optimization, enables scientists to systematically troubleshoot amplification issues, enhance reproducibility, and achieve high-quality results.

Core Characteristics of DNA Polymerases

Thermostability: Withstanding the Heat

Thermostability refers to a DNA polymerase's ability to retain its structural integrity and catalytic activity through repeated exposure to the high temperatures required for DNA denaturation (typically 94–98°C) [19] [20]. This property is essential for the automated cycling inherent to PCR. While Taq polymerase from Thermus aquaticus is sufficiently stable for many routine applications, its half-life decreases significantly above 90°C [19]. For protocols requiring prolonged high-temperature incubation, such as amplifying templates with robust secondary structures or high GC-content, more thermostable enzymes are advantageous. Polymerases derived from hyperthermophilic archaea, such as Pfu (Pyrococcus furiosus), exhibit superior stability. Pfu polymerase, for instance, is approximately 20 times more stable at 95°C than Taq polymerase [19].

Fidelity: The Accuracy of Replication

Fidelity defines the accuracy with which a DNA polymerase synthesizes a new DNA strand complementary to the template, and it is a paramount concern for applications like cloning and sequencing where sequence integrity is critical [19]. Fidelity is often expressed as the inverse of the error rate (e.g., number of errors per base synthesized) [19]. The primary mechanism for high fidelity is proofreading activity, which is mediated by a dedicated 3′→5′ exonuclease domain that recognizes and excizes misincorporated nucleotides [19]. Standard Taq polymerase lacks this proofreading activity, resulting in a relatively high error rate. In contrast, proofreading enzymes like Pfu polymerase demonstrate significantly higher fidelity. Through protein engineering, "next-generation" high-fidelity polymerases have been developed with error rates up to 50–300 times lower than that of Taq polymerase [19].

Processivity: Efficiency of Synthesis

Processivity measures the number of nucleotides a DNA polymerase adds to a growing DNA chain in a single binding event [19]. A highly processive enzyme can synthesize long stretches of DNA without dissociating from the template, which directly impacts synthesis speed and efficiency. High processivity is particularly beneficial for:

- Amplifying long DNA targets (long-range PCR)

- Copying through templates with complex secondary structures or high GC-content

- Achieving robust amplification in the presence of common PCR inhibitors found in samples like blood or plant tissues [19] [6]

Early proofreading polymerases often exhibited lower processivity because the exonuclease activity could slow the overall rate of synthesis [19]. This limitation has been overcome by engineering polymerases to include strong DNA-binding domains, enhancing processivity 2- to 5-fold without compromising fidelity [19].

Hot-Start Enzymes: Enhancing Specificity from the Start

Nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation are common challenges in PCR, often originating from enzymatic activity at room temperature during reaction setup [19]. Hot-start technology addresses this by rendering the DNA polymerase inactive until a high-temperature activation step is applied. In one common method, a specific antibody is bound to the polymerase, inhibiting its activity at lower temperatures [19]. During the initial PCR denaturation step (e.g., >90°C), the antibody is irreversibly denatured, releasing active polymerase. This ensures that the enzyme only becomes functional after the reaction mixture has reached a temperature that discourages nonspecific primer binding [19]. Hot-start polymerases provide a significant improvement in specificity and yield, facilitate room-temperature setup for high-throughput workflows, and are available in various fidelity and processivity profiles [19].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Common DNA Polymerases

| Polymerase | Thermostability | Fidelity (Relative to Taq) | Proofreading (3'→5' Exo) | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | Good | 1x | No | Routine PCR, genotyping [20] |

| Pfu | Excellent | ~7x | Yes | High-fidelity applications (cloning, sequencing) [19] [20] |

| Engineered High-Fidelity | Excellent | 50x – 300x | Yes | Ultra-precise applications (NGS library prep, mutagenesis) [19] |

| Hot-Start (various) | Varies by base enzyme | Varies by base enzyme | Varies by base enzyme | All applications requiring high specificity and low background [19] [20] |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This section addresses common experimental challenges related to DNA polymerase function and selection, providing targeted solutions to improve PCR outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My PCR yields no product. What should I check first related to my enzyme choice?

- Verify Enzyme Activity: Always include a positive control reaction to confirm that all components, especially the polymerase, are functional [21].

- Assess Template Complexity: If your template is GC-rich, long, or contains secondary structures, switch to a polymerase with high processivity or one that is specifically recommended for such difficult templates [6].

- Check for Inhibitors: If you suspect inhibitors are present in your sample (e.g., from blood or plant tissue), dilute the template or re-purify it. Alternatively, use a polymerase known for high inhibitor tolerance [6] [21].

- Review Thermal Cycling Parameters: Ensure the denaturation temperature and time are sufficient for your template and that the extension time is appropriate for the amplicon length [6].

Q2: I get multiple bands or a smear on the gel instead of a single, specific product. How can I improve specificity?

- Use a Hot-Start Polymerase: This is one of the most effective steps to prevent nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation that occurs during reaction setup [19] [22].

- Optimize Annealing Temperature: Increase the annealing temperature in 2°C increments to enhance stringency. Use a gradient thermal cycler for systematic optimization [6] [10].

- Reduce Template Amount: Excess template can lead to nonspecific binding. Try reducing the template amount by 2- to 5-fold [21].

- Optimize Mg²⁺ Concentration: High Mg²⁺ concentration can reduce specificity. Titrate Mg²⁺ in 0.2–1 mM increments to find the optimal concentration [22] [10].

Q3: My downstream sequencing reveals mutations in the cloned PCR product. How can I reduce errors?

- Switch to a High-Fidelity Polymerase: Use a proofreading enzyme (e.g., Pfu or an engineered high-fidelity polymerase) for applications requiring high sequence accuracy [19] [22].

- Reduce Cycle Number: Higher numbers of PCR cycles increase the chance of accumulating errors. Use the minimum number of cycles necessary to obtain sufficient yield [22].

- Ensure Balanced dNTPs: Use fresh, equimolar dNTP mixtures. Unbalanced nucleotide concentrations increase the error rate of all DNA polymerases [22] [21].

- Avoid Overcycling: Overcycling can lead to pH shifts, dNTP depletion, and accumulation of damaged DNA, all of which promote misincorporation [21].

Q4: Why is Mg²⁺ concentration so critical, and how does it interact with the DNA polymerase? Mg²⁺ is an essential cofactor for all DNA polymerases. It is directly involved in the catalytic reaction and stabilizes the interaction between the primer, template, and enzyme [23] [10].

- Low Mg²⁺ concentrations lead to poor enzyme activity and low or no yield.

- High Mg²⁺ concentrations stabilize non-specific primer-template interactions, leading to spurious amplification, and can also decrease fidelity by promoting misincorporation [10]. The optimal concentration is often dependent on the specific polymerase, the primer-template system, and the presence of chelators like EDTA. Therefore, titration is a fundamental part of PCR optimization [23] [22].

Troubleshooting Table

Table 2: Common PCR Problems and Solutions

| Observation | Possible Causes Related to Polymerase | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No Product | • Enzyme inactive or insufficient• Enzyme unsuitable for complex template | • Include positive control; increase enzyme amount [21]• Switch to high-processivity enzyme [6] |

| Multiple Bands or Smear | • Non-specific initiation at low temp• Low reaction stringency | • Use hot-start polymerase [19] [22]• Increase annealing temperature; optimize Mg²⁺ [6] |

| Primer-Dimer Formation | • Polymerase activity during setup | • Use hot-start polymerase [19] |

| Low Yield of Long Amplicons | • Low processivity• Insufficient extension time | • Use polymerase engineered for long-range PCR [19] [6]• Increase extension time per kb [6] |

| High Error Rate (Poor Fidelity) | • Low-fidelity polymerase• Excessive Mg²⁺ or cycles | • Use high-fidelity/proofreading polymerase [19] [22]• Optimize Mg²⁺; reduce cycle number [22] [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol: Magnesium Titration for Specificity and Fidelity

Objective: To determine the optimal Mg²⁺ concentration for a specific primer-template pair to maximize yield and specificity while maintaining high fidelity [23] [10].

Background: Mg²⁺ concentration is a key variable in PCR optimization. This protocol provides a systematic approach to titrate Mg²⁺, which is crucial for the broader goal of reagent concentration optimization.

Materials:

- 10X PCR Buffer (without MgCl₂)

- 50 mM MgCl₂ stock solution

- dNTP Mix (10 mM each)

- Forward and Reverse Primers (10 µM each)

- DNA Template

- Selected DNA Polymerase

- Nuclease-free Water

Method:

- Prepare a master mix containing all PCR components except the MgCl₂ and template. Aliquot the master mix into 8 PCR tubes.

- Spike each tube with a different volume of the 50 mM MgCl₂ stock to create a final concentration series (e.g., 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 5.0 mM). Adjust volumes with nuclease-free water.

- Add the template to each tube, mix gently, and centrifuge briefly.

- Run the PCR using the recommended thermal cycling conditions for your polymerase and amplicon.

- Analyze the results by agarose gel electrophoresis. Assess for:

- Maximum yield of the desired product.

- Minimal nonspecific bands or primer-dimer.

- The Mg²⁺ concentration that produces the highest yield of the specific product with the cleanest background is optimal for that reaction [23] [10].

Protocol: Annealing Temperature Gradient for Specificity

Objective: To empirically determine the optimal annealing temperature (Ta) for a primer set to achieve specific amplification.

Background: The theoretical melting temperature (Tm) of a primer is a guide, but the optimal Ta must be determined experimentally. An annealing temperature that is too low causes mispriming, while one that is too high reduces yield [10].

Materials:

- Optimized PCR master mix (including optimized Mg²⁺ from previous protocol, if known)

- DNA Template

- Primers

Method:

- Prepare a single PCR master mix containing all components.

- Aliquot the master mix into 8 PCR tubes.

- Place the tubes in a thermal cycler equipped with a gradient function across the block.

- Program the cycler with an annealing temperature gradient that spans a relevant range (e.g., 5°C below to 5°C above the calculated Tm of your primers).

- Run the PCR and analyze the products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Identify the highest annealing temperature that still produces a strong, specific amplicon. This temperature represents the optimal trade-off between specificity and yield [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCR Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Key Considerations for Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Engineered enzyme with proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity for accurate DNA synthesis. | Select based on required fidelity, processivity, and thermostability for the application (e.g., cloning vs. diagnostics) [19] [20]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme chemically modified or antibody-bound to be inactive at room temperature, preventing nonspecific amplification. | Crucial for high-specificity applications and high-throughput workflows where reactions are set up at room temperature [19]. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Source of Mg²⁺ ions, an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. | Concentration must be optimized for each primer-template pair; dramatically affects specificity, yield, and fidelity [23] [10]. |

| PCR Buffer (with/without Mg²⁺) | Provides optimal pH and salt conditions for polymerase activity and primer-template binding. | Specific buffer formulations are often paired with specific polymerases; using the manufacturer's recommended buffer is critical [10]. |

| dNTP Mix | Equimolar solution of the four deoxynucleotides (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP), the building blocks for DNA synthesis. | Use fresh, balanced mixtures to prevent incorporation errors. Unbalanced dNTPs increase PCR error rate [22] [21]. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., DMSO, Betaine) | Co-solvents that help denature complex DNA secondary structures, particularly in GC-rich templates. | Use at recommended concentrations (e.g., 2-10% DMSO, 1-2 M Betaine). Titration may be necessary [10]. |

Visual Summaries

Polymerase Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical decision process for selecting the appropriate DNA polymerase based on experimental requirements.

Figure 1: A decision workflow to guide the selection of a DNA polymerase based on key experimental requirements such as fidelity, template difficulty, and specificity.

Mechanism of Hot-Start Activation

This diagram visualizes the mechanism of antibody-based hot-start DNA polymerase activation, a key feature for improving PCR specificity.

Figure 2: The mechanism of antibody-based hot-start activation. The polymerase is inhibited at room temperature during setup but is activated by a high-temperature denaturation step, preventing nonspecific amplification.

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) optimization, the synergistic relationship between deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) and magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) is a critical determinant of success. Mg²⁺ acts as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase enzyme activity, while simultaneously serving as a crucial bridge for the incorporation of dNTPs into the newly synthesized DNA strand [24]. The concentration balance between these two reagents is paramount; Mg²⁺ binds to dNTPs in the reaction mixture, meaning the effective, free concentration of Mg²⁺ available for the polymerase is directly influenced by the total dNTP concentration [1] [10]. Understanding this interaction is fundamental for researchers aiming to troubleshoot failed amplifications, enhance specificity, and achieve high-fidelity results in genetic analysis, cloning, and diagnostic assay development.

Troubleshooting Common PCR Problems

The following section addresses frequent issues related to dNTP and Mg²⁺ concentrations, providing diagnostic guidance and solutions.

1. Problem: No PCR product or very low yield observed on a gel.

- Potential Cause: Excessively low Mg²⁺ concentration, or dNTP concentration below the Km of the DNA polymerase.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Check dNTP Concentration: Ensure the final concentration of each dNTP is at least 0.2 mM. The concentration should not fall below 0.010–0.015 mM, the estimated Km for free dNTPs, to ensure efficient incorporation [1].

- Optimize Mg²⁺: Titrate the MgCl₂ concentration upward in 0.5 mM increments from a baseline of 1.0 mM up to 4.0 mM. Too little Mg²⁺ results in reduced or no polymerase activity [25] [26].

- Verify Component Quality: Ensure dNTPs have not degraded due to improper storage or repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

2. Problem: Multiple non-specific bands or a smear of DNA products.

- Potential Cause: Excessive Mg²⁺ concentration, leading to non-specific primer binding and reduced amplification fidelity.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Reduce Mg²⁺ Concentration: Titrate MgCl₂ downward in 0.5 mM increments. High Mg²⁺ concentrations stabilize non-specific primer-template interactions, causing spurious amplification [25] [24].

- Increase Annealing Stringency: Raise the annealing temperature in 1-2°C increments to improve primer specificity [26] [10].

- Lower dNTPs (for non-proofreading enzymes): For applications requiring high fidelity, reducing dNTP concentrations to 0.01–0.05 mM can improve accuracy when using non-proofreading DNA polymerases [1].

3. Problem: PCR failure with GC-rich templates.

- Potential Cause: The formation of stable secondary structures that impede polymerase progression. Standard Mg²⁺ concentrations may be insufficient.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Titrate Mg²⁺: GC-rich templates often require higher-than-standard MgCl₂ concentrations. Perform a gradient from 1.5 mM to 4.0 mM to find the optimal level [26].

- Incorporate Additives: Use buffer enhancers like DMSO (at 2-10%), betaine (0.5 M to 2.5 M), or commercial GC enhancers. These additives help destabilize secondary structures and can homogenize the stability of DNA regions with varying GC content [26] [10].

- Select a Specialized Polymerase: Use DNA polymerases specifically engineered or supplied with optimized buffers for amplifying GC-rich sequences [26].

Quantitative Data and Optimization Guidelines

The tables below summarize key concentration ranges and their effects to guide systematic optimization.

Table 1: Standard and Optimization Ranges for dNTPs and Mg²⁺

| Reagent | Standard Final Concentration | Optimization Range | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| dNTPs (each) | 0.2 mM (200 µM) [25] | 0.01 - 0.2 mM [1] [27] | Building blocks for new DNA strand synthesis. |

| MgCl₂ | 1.5 - 2.0 mM [25] | 1.0 - 4.0 mM [25] [4] | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase; stabilizes primer binding. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting the dNTP-Mg²⁺ Interaction

| Symptom | Probable Imbalance | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| No amplification / low yield | [Mg²⁺] too low or [dNTP] below Km | Increase MgCl₂ in 0.5 mM increments; ensure dNTP ≥ 0.2 mM. |

| Non-specific bands / smearing | [Mg²⁺] too high | Decrease MgCl₂ in 0.5 mM increments; increase annealing temperature. |

| Poor fidelity / misincorporation | High [dNTP] and/or high [Mg²⁺] | Lower both dNTP (to 0.01-0.05 mM) and Mg²⁺ concentrations proportionally [1]. |

| Inconsistent results with GC-rich DNA | Standard [Mg²⁺] is suboptimal | Titrate MgCl₂ (1.0-4.0 mM) and include additives like DMSO or betaine [26]. |

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol 1: MgCl₂ Concentration Titration

This protocol is fundamental for optimizing any new PCR assay, especially with challenging templates [25] [26].

- Prepare a Master Mix: Create a standard master mix containing all PCR components (buffer without Mg²⁺, template, primers, dNTPs, polymerase) except for MgCl₂.

- Aliquot the Master Mix: Dispense equal volumes of the master mix into 8 separate PCR tubes.

- Spike with MgCl₂: Add MgCl₂ stock solution to each tube to create a final concentration gradient (e.g., 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0 mM).

- Run PCR: Perform amplification using standard or recommended cycling conditions.

- Analyze Results: Resolve the PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. The condition with the strongest specific band and least background is the optimal Mg²⁺ concentration.

Protocol 2: Optimizing PCR for GC-Rich Templates

This protocol combines Mg²⁺ titration with the use of chemical enhancers [26].

- Polymerase and Buffer Selection: Begin with a DNA polymerase known for robust performance on difficult templates (e.g., Q5 or OneTaq DNA Polymerase) and its corresponding GC buffer if available.

- Set Up Reaction Tubes: Prepare reactions with a constant, slightly elevated MgCl₂ concentration (e.g., 2.5 mM) and varying additives:

- Tube A: No additive (control).

- Tube B: 5% DMSO.

- Tube C: 1 M Betaine.

- Tube D: Manufacturer's GC Enhancer (at recommended starting concentration).

- Use a Touchdown PCR Program: Employ an initial annealing temperature 5-10°C above the calculated Tm for the first 5-10 cycles, followed by a lower temperature for the remaining cycles. This increases initial specificity.

- Analyze and Refine: Identify the most effective additive and then fine-tune its concentration and/or the Mg²⁺ level in a subsequent experiment.

Visualizing the Critical Interaction

The following diagram illustrates the cofactor role of Mg²⁺ in the phosphodiester bond formation during DNA synthesis, highlighting its direct interaction with dNTPs.

Diagram 1: Mg²⁺ Role in dNTP Incorporation. Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) are essential cofactors that bind directly to incoming dNTPs and activate the DNA polymerase enzyme. This interaction is crucial for catalyzing the formation of a phosphodiester bond between the 3'-hydroxyl group of the primer and the α-phosphate of the dNTP, enabling DNA strand elongation [1] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in PCR | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| dNTP Mix | Provides the four nucleotides (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) as building blocks for new DNA synthesis. | Use equimolar concentrations of all four dNTPs. Store at -20°C in small aliquots to avoid degradation [1] [27]. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Serves as a source of Mg²⁺ ions, an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity and primer annealing. | Concentration is critical and must be optimized. It chelates with dNTPs, so the free Mg²⁺ concentration is key [1] [24]. |

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that catalyzes the template-directed synthesis of new DNA strands. | Choice depends on application (e.g., standard Taq for speed, high-fidelity enzymes for cloning). All require Mg²⁺ as a cofactor [1] [25]. |

| PCR Buffers | Provides a stable chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) for the reaction. | Often supplied with MgCl₂, or as a Mg-free buffer to allow for flexible optimization of Mg²⁺ concentration [25] [4]. |

| Buffer Additives | Chemicals like DMSO, Betaine, or Formamide that assist in challenging amplifications. | Help denature GC-rich secondary structures or increase primer annealing stringency. Their use may require re-optimization of Mg²⁺ levels [26] [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it critical to balance dNTP and Mg²⁺ concentrations? The interaction is stoichiometric: Mg²⁺ ions bind to the phosphate groups of dNTPs to form a substrate complex that the DNA polymerase can utilize. If the dNTP concentration is too high, it chelates all available Mg²⁺, leaving none to act as a cofactor for the enzyme, which halts the reaction. Conversely, if Mg²⁺ is in large excess, it can reduce fidelity and promote non-specific binding [1] [10].

Q2: What is a typical starting point for Mg²⁺ concentration when dNTPs are at 0.2 mM each? A final concentration of 1.5 mM to 2.0 mM MgCl₂ is the standard and recommended starting point for most PCR assays when using standard dNTP concentrations [25]. This provides a sufficient excess of free Mg²⁺ after accounting for binding to dNTPs.

Q3: How do I adjust concentrations for high-fidelity PCR? To maximize fidelity, use lower concentrations of both dNTPs and Mg²⁺. Reduce the concentration of each dNTP to the 0.01–0.05 mM range and proportionally lower the MgCl₂ concentration. This strategy increases the polymerase's discrimination against misincorporated nucleotides [1].

Q4: My template has high GC content. How should I adjust my approach? GC-rich templates are prone to forming stable secondary structures. Begin by selecting a polymerase and buffer system designed for GC-rich targets. You will likely need to increase the MgCl₂ concentration beyond 2.0 mM (test up to 4.0 mM) and incorporate a reagent like DMSO (2-10%) or betaine (0.5-2.5 M) to help denature these structures [26].

Q5: What are the visual signs on a gel of too much or too little Mg²⁺?

- Too little Mg²⁺: Results in a complete absence of product or an extremely faint band.

- Too much Mg²⁺: Manifests as multiple non-specific bands, a smear of DNA, or the presence of primer-dimers [25] [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: My PCR consistently fails to amplify a DNA template with very high GC content (>80%). Which additives should I try first?

A: For extremely GC-rich templates, a combination of additives is often most effective. You should first titrate DMSO at concentrations between 3-10% or betaine at 0.5 M to 2.5 M [28] [29]. These additives destabilize DNA secondary structures by reducing the melting temperature (Tm) of GC-rich sequences, facilitating strand separation during the denaturation and annealing steps [28] [30]. If non-specific amplification or sensitivity to inhibitors is a concern, add BSA at 10-100 µg/mL to stabilize the polymerase and bind potential inhibitors [4] [31].

Q2: I am performing long-range PCR (>5 kb) and getting smeared or non-specific bands. How can additives help?

A: Long-range PCR is susceptible to truncated products and nonspecific amplification. Using betaine (1.0-1.3 M) is highly recommended as it helps to amplify through complex secondary structures and stabilizes the DNA polymerase [28]. DMSO (1-10%) can also be beneficial, but its concentration must be carefully optimized as high levels can inhibit some polymerases [4] [28]. A proofreading polymerase mixed with a non-proofreading polymerase is often used in long-range PCR to correct misincorporated nucleotides, and additives like betaine further enhance this process [32] [28].

Q3: After adding BSA to my reaction, I see no improvement. What could be the reason?

A: The enhancing effect of BSA is most pronounced in the first 10-15 cycles of PCR, as it can denature at high temperatures over many cycles [31]. For reactions with high cycle numbers, you may need to supplement with fresh BSA partway through the run. Furthermore, BSA's primary benefit is to relieve inhibition from contaminants in the sample or reaction mixture [31] [30]. If your template is pure, you may not observe a significant effect from BSA alone. It often shows the strongest effect when used as a co-additive with DMSO or formamide [31].

Q4: Can I use multiple additives together in a single PCR?

A: Yes, using enhancer "cocktails" is a common and effective strategy, as different additives can act through complementary mechanisms [28]. A typical and powerful combination for GC-rich templates is betaine and DMSO [28]. Research has also demonstrated that BSA can be used synergistically with organic solvents like DMSO to further boost yields across a broad range of amplicon sizes [31]. When combining additives, it is crucial to re-optimize their concentrations, as their effects can be interdependent.

Q5: What is the most critical parameter to optimize when first introducing an additive?

A: The concentration of the additive is paramount. Nearly all PCR enhancers, including DMSO, betaine, and BSA, exhibit bell-shaped response curves [28]. This means that while an optimal concentration will significantly improve the reaction, too little will have no effect, and too much can become inhibitory. A titration series should always be performed to find the ideal concentration for your specific template and primer set.

Quantitative Data on Common PCR Additives

The following tables summarize key information for the three primary additives, including their mechanisms, optimal concentrations, and considerations for use.

Table 1: Overview of Key PCR Additives

| Additive | Primary Mechanism of Action | Optimal Concentration Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | Destabilizes DNA double helix, reduces Tm, prevents secondary structure formation [28] [29] | 1 - 10% (v/v) [4] [29] | GC-rich templates, long-range PCR, reduction of non-specific bands [28] |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Binds to PCR inhibitors (e.g., phenols, polysaccharides), stabilizes DNA polymerase [31] [30] | 10 - 100 µg/mL [4] [31] | Inhibitor-prone samples (e.g., soil, blood, plants), co-additive with solvents [31] |

| Betaine | Equalizes Tm of GC and AT base pairs, disrupts secondary structure, stabilizes enzymes [28] | 0.5 M - 2.5 M [4] [28] | GC-rich templates, long-range PCR, used in combo with DMSO [28] |

Table 2: Additive Compatibility and Synergistic Combinations

| Combination | Reported Synergistic Effect | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| BSA + DMSO | BSA further enhances yield gains from DMSO; co-enhancing effect broadens effective DMSO concentration range [31] | Challenging GC-rich templates (>65% GC) of various sizes (0.4 kb to 7.1 kb) [31] |

| Betaine + DMSO | Powerful mixture for denaturing and amplifying very stable GC-rich sequences [28] | Extremely GC-rich DNA (>80%); a classic and highly effective combo [28] [29] |

| BSA + Formamide | BSA acts as a co-enhancer with formamide, improving yields [31] | An alternative to DMSO-based combinations |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Titration of DMSO, BSA, and Betaine

This protocol provides a methodology for systematically determining the optimal concentration of additives for a specific PCR assay [4].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Taq DNA Polymerase with recommended 10X Reaction Buffer

- dNTP Mix (10 mM each)

- Forward and Reverse Primers (20 µM each)

- Template DNA

- Sterile Nuclease-Free Water

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- DMSO (Molecular Biology Grade)

- BSA (Molecular Biology Grade, e.g., 10 µg/µL stock)

- Betaine (5M stock solution, molecular biology grade)

2. Master Mix Preparation:

Prepare a master mix for n+1 reactions (where n is the number of titration points) to ensure volume consistency. A typical 50 µL reaction is outlined below. Note that the additive will replace an equivalent volume of water.

| Component | Volume per 50 µL Reaction | Final Concentration (without additive) |

|---|---|---|

| 10X PCR Buffer | 5 µL | 1X |

| dNTP Mix (10 mM) | 1 µL | 200 µM |

| Forward Primer (20 µM) | 1 µL | 0.4 µM |

| Reverse Primer (20 µM) | 1 µL | 0.4 µM |

| Template DNA | Variable | 1-100 ng |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | 0.5 - 1.25 U | As per mfr. |

| Additive Stock | Variable | See titration series |

| Nuclease-Free Water | To 50 µL | - |

3. Additive Titration Series: Dispense the master mix into individual PCR tubes, then add the additives to achieve the following final concentrations:

- DMSO: 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, 10% (v/v) [4] [29]

- BSA: 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0 µg/µL (i.e., 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 µg/mL) [4] [31]

- Betaine: 0 M, 0.5 M, 1.0 M, 1.5 M, 2.0 M, 2.5 M [4] [28]

4. Thermal Cycling: Run the PCR using your standard cycling parameters. If possible, use a gradient thermal cycler to simultaneously optimize the annealing temperature.

5. Analysis: Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. The optimal condition will be the one that produces the brightest specific band with the least or no non-specific amplification or primer-dimer.

Protocol 2: Optimizing PCR for GC-Rich Templates Using a Combinatorial Approach

This protocol is specifically designed for challenging, high-GC content targets based on proven synergistic combinations [31] [28] [29].

1. Reagent Setup: Include all reagents from Protocol 1. Prepare a special enhancer cocktail containing 3% DMSO and 5% Glycerol as a base solvent, which has been shown to aid in the dispersion of certain additives and improve amplification of GC-rich sequences [29].

2. Experimental Design: Test the following conditions in a 50 µL reaction volume, using the master mix table from Protocol 1 as a base.

- Condition A: Base reaction (no additives).

- Condition B: 3% DMSO + 5% Glycerol only.

- Condition C: 3% DMSO + 5% Glycerol + 1.0 M Betaine.

- Condition D: 3% DMSO + 5% Glycerol + 40 µg/mL BSA.

- Condition E: 3% DMSO + 5% Glycerol + 1.0 M Betaine + 40 µg/mL BSA.

3. Thermal Cycling with a Touchdown Protocol: For highly structured templates, use a touchdown program to increase specificity.

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes.

- 10 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: Start at 65°C and reduce by 0.5°C per cycle for 10 cycles (down to 60°C) for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb.

- 25 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: 60°C for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

Experimental Workflow and Additive Mechanism Diagrams

Diagram 1: Additive Selection Workflow

Diagram 2: Mechanism of Action of PCR Additives

Systematic Optimization Protocols: A Step-by-Step Guide to Fine-Tuning Your Reaction

Master Mix Calculations and Component Formulation

Accurate calculation and formulation of the PCR master mix are fundamental to experimental reproducibility. The process involves determining the correct volume and concentration of each component for a single reaction, then scaling this up for the total number of reactions.

Standardized Component Concentrations

The table below outlines the typical stock concentrations and desired final concentrations for key reagents in a standard 50 µl PCR reaction [4] [33] [13].

Table 1: Standard PCR Component Concentrations for a 50 µl Reaction

| Reagent | Common Stock Concentration | Final Concentration (C~F~) | Dilution Factor (Stock / C~F~) | Volume per 50 µl Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer | 10X | 1X | 10 | 5 µl |

| dNTPs | 10 mM | 200 µM (each) | 50 | 1 µl |

| MgCl~2~ | 25 mM | 1.5 mM | 16.66 | 3 µl |

| Forward Primer | 10 µM | 250 nM | 40 | 1.25 µl |

| Reverse Primer | 10 µM | 250 nM | 40 | 1.25 µl |

| DNA Polymerase | 5 U/µl | 1.25 U | - | 0.25 µl |

| Template DNA | Variable (e.g., 1 µg/µl) | ~10^5^ molecules | - | Variable (e.g., 0.5 µl) |

| PCR-Grade Water | - | - | - | Q.S. to 50 µl |

Master Mix Scaling Calculations

To prepare a master mix for multiple reactions, the per-reaction volumes are multiplied by the total number of reactions, including controls. It is critical to include an overtage of at least 10% to account for pipetting errors, evaporation, and liquid adherence to tips [33].

The formula for calculating the total volume of any master mix component is: Total Volume = (Volume per reaction × Number of reactions) + Overage

For example, to calculate the total buffer needed for 10 reactions with a 10% overage:

- Volume per reaction = 5 µl

- Number of reactions = 10

- Overage = (5 µl × 10) × 0.10 = 5 µl

- Total Buffer Volume = (5 µl × 10) + 5 µl = 55 µl

Best Practices for Master Mix Assembly

A standardized workflow for assembling the master mix is essential for minimizing variability and preventing contamination.

Diagram: Optimal Master Mix Assembly Workflow

Pipetting and Contamination Prevention

- Pipetting Order: Always add components to the master mix in order of increasing cost. This minimizes financial loss if an error occurs and the mix must be discarded [33].

- Mixing: After assembly, mix the master mix gently but thoroughly by pipetting up and down at least 20 times. Incomplete mixing can create density gradients, leading to reaction failure [4] [6].

- Physical Segregation: Perform master mix preparation, template addition, and post-PCR analysis in physically separated areas with dedicated equipment and lab coats to prevent amplicon contamination [34].

- Consumables: Use sterile, low-retention, aerosol-filter tips to minimize cross-contamination and ensure accurate volume transfer [33] [34].

Minimizing Variability and Troubleshooting Common Issues

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Master Mix Optimization and Their Functions

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Brief Notes on Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme inactive at room temperature, requires heat activation. | Prevents non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup, enhancing yield and specificity [6] [13]. |

| PCR Additives (DMSO, BSA, Betaine) | Modifies DNA melting temperature, reduces secondary structures, neutralizes inhibitors. | Use to optimize amplification of difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich sequences). Concentration must be optimized (e.g., DMSO at 1-10%) [4] [6] [13]. |

| MgCl~2~ Solution | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. | Concentration is critical; too little causes no yield, too much promotes non-specific products. Optimize in 0.2-1.0 mM increments [4] [35] [1]. |

| Molecular-Grade Water | Solvent for the reaction, free of nucleases and PCR inhibitors. | Essential for reproducibility. Never use lab-pure water systems, as they can introduce contaminants [6] [34]. |

| dNTP Mix | Provides the four nucleotide building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for new DNA strands. | Use balanced, equimolar concentrations (typically 200 µM each). Unbalanced dNTPs increase polymerase error rates [6] [35] [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

FAQ 1: My PCR shows no product or very low yield. What are the first parameters to check?

- Possible Cause: Incorrect Annealing Temperature.

- Possible Cause: Suboptimal Mg²⁺ Concentration.

- Possible Cause: Too Few Cycles or Insufficient Template.

FAQ 2: I see multiple bands or a smear on the gel instead of a single, specific product. How can I improve specificity?

- Possible Cause: Primer Annealing at Low Temperature.

- Possible Cause: Excess Primer, Template, or Enzyme.

- Solution: Optimize reagent concentrations. Primer concentrations are typically optimal between 0.1–1 µM. High primer concentrations promote primer-dimer formation and non-specific binding. Similarly, reducing the amount of template DNA or DNA polymerase can reduce non-specific products [6] [13] [1].

FAQ 3: How can I prevent contamination in my master mix and reactions?

- Solution: Establish separate, physically isolated pre- and post-PCR work areas with dedicated equipment, lab coats, and consumables [34]. Always include a negative control (master mix + water instead of template) to detect contamination. Use UV irradiation and 10% bleach to decontaminate workstations and pipettes. Aliquot all reagents to avoid contaminating stock solutions [33] [34].

FAQ 4: My PCR results are inconsistent from one run to the next, even with the same protocol.

- Possible Cause: Pipetting Inaccuracies and Improper Mixing.

- Possible Cause: Improper Reagent Storage and Handling.

- Solution: Store all reagents according to manufacturers' specifications. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles by creating single-use aliquots. Keep reagents on ice during setup, but note that some polymerases are sensitive to "cold-activation" and should be handled according to specific guidelines [6] [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues and Solutions Related to Primer Concentration

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Product or Low Yield | Primer concentration too low [36] | Increase primer concentration within the 0.1-1.0 µM range. Test increments of 0.1-0.2 µM [6]. |

| Multiple Bands or Non-Specific Amplification | Primer concentration too high, leading to off-target binding and primer-dimer formation [13] [6] | Decrease primer concentration. Use hot-start DNA polymerases to prevent non-specific amplification at lower temperatures [6] [10]. |

| Primer-Dimer Formation | Excess primers facilitate self-annealing, especially with non-optimal 3' ends [13] [6] | Lower primer concentration (e.g., to 0.1-0.3 µM). Ensure primers do not have complementary 3' ends [13] [37]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Different Primer Pairs | Suboptimal primer concentration for a specific primer set's characteristics [38] | Re-optimize primer concentration for each new primer pair. For multiplex PCR, individually adjust each pair's concentration to balance amplification efficiency [38]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Primer Concentration

A stepwise protocol to determine the optimal primer concentration for your PCR assay.

1. Prepare a Master Mix Create a master mix containing all common reagents for your number of reactions plus 10% extra to account for pipetting error [13]. The table below outlines the components for a standard 50 µL reaction.

Table: Reagents for a Standard 50 µL Optimization Reaction

| Reagent | Stock Concentration | Final Concentration (Starting Point) |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Buffer | 10X | 1X |

| dNTPs | 10 mM | 200 µM |

| MgCl₂ | 25 mM | 1.5 mM |

| DNA Template | Variable | ~105 molecules (e.g., 10-100 ng genomic DNA) [13] |

| DNA Polymerase | 5 U/µL | 1.25 U (e.g., 0.25 µL) [13] |

| Forward Primer | 10 µM | Variable (See Step 2) |

| Reverse Primer | 10 µM | Variable (See Step 2) |

| Nuclease-Free Water | - | To 50 µL |

2. Set Up the Primer Concentration Gradient Aliquot the master mix into separate tubes. Prepare a dilution series of your primers to test a range of final concentrations from 0.1 µM to 1.0 µM [36] [37]. A typical gradient is shown below.

Table: Example Primer Concentration Gradient Setup

| Reaction Tube | Final Primer Concentration | Volume of 10 µM Primer Stock to Add (per 50 µL reaction) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.1 µM | 0.5 µL |

| 2 | 0.2 µM | 1.0 µL |

| 3 | 0.4 µM | 2.0 µL |

| 4 | 0.6 µM | 3.0 µL |

| 5 | 0.8 µM | 4.0 µL |

| 6 | 1.0 µM | 5.0 µL |

3. Execute PCR and Analyze Results

- Run the PCR using previously optimized or standard cycling conditions [13].

- Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Interpretation:

- The optimal concentration produces a single, strong band of the expected size.

- A concentration yielding high specificity but low yield may require slight increases.

- A concentration causing smearing or multiple bands is too high and should be decreased.

This workflow visualizes the key decision points in the optimization process:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the typical starting point for primer concentration optimization? A final concentration of 0.2-0.5 µM for each primer is a common and effective starting point for many standard PCR reactions [15] [37]. From there, you can test a broader range to fine-tune the balance between yield and specificity.

Q2: How does high primer concentration cause non-specific amplification? When primer concentration is too high (e.g., at the upper end of the 1.0 µM range), it increases the chance that primers will bind to partially complementary, off-target sequences on the DNA template with lower stringency. This leads to the amplification of unwanted products, visible as multiple bands or a smear on a gel [13] [10].

Q3: Why is my PCR yield low even with a 1.0 µM primer concentration? Low yield at high primer concentration often indicates a different underlying issue. Consider checking the following:

- Template DNA Quality/Quantity: Re-quantify and ensure it is not degraded [15] [6].

- Primer Design: Verify primer specificity and the absence of strong secondary structures [39] [37].

- Annealing Temperature: The temperature may be too high, preventing even specific primers from binding efficiently. Optimize the annealing temperature using a gradient PCR block [36] [6].

Q4: How do I optimize primer concentration for multiplex PCR? In multiplex PCR, where multiple targets are amplified in one tube, balancing primer concentrations is critical. Primer pairs often have different inherent efficiencies. The recommended strategy is to:

- Test each primer pair individually to find its optimal concentration.

- Systemically test different ratios of these optimal concentrations in the multiplex reaction.

- Adjust concentrations until all targets are amplified with relatively equal efficiency, which may require reducing the concentration of a highly efficient pair and increasing that of a less efficient one [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for PCR and Primer Optimization

| Reagent | Function in Optimization | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by inhibiting enzyme activity until the high-temperature denaturation step [13] [10]. | Crucial for achieving high specificity when using lower primer concentrations. |

| dNTP Mix | Provides the nucleotide building blocks for new DNA strands [13]. | Use balanced, equimolar concentrations of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP to prevent incorporation errors and maintain polymerase fidelity [6]. |

| MgCl₂ / MgSO₄ Solution | Serves as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. Concentration directly affects primer annealing, enzyme efficiency, and fidelity [13] [10]. | Requires co-optimization with primer concentration, as Mg²⁺ stabilizes the primer-template duplex. Typical optimal range is 1.5-2.5 mM [6]. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., DMSO, Betaine) | Assist in amplifying difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich sequences) by disrupting secondary structures and lowering the template's effective melting temperature [13] [10]. | May require re-optimization of primer annealing temperature and concentration, as they affect hybridization stringency. |

| Standardized Template DNA | Provides a known, consistent number of template molecules for robust optimization, especially critical in multiplex PCR [38]. | Helps distinguish between issues caused by primer concentration and those caused by variable template quality or quantity. |

Why Magnesium Concentration is Critical for PCR

In Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) experiments, magnesium ion (Mg²⁺) concentration is a vital component. It serves as a essential cofactor for thermostable DNA polymerases, such as Taq DNA polymerase, influencing enzyme activity, fidelity, and specificity [4]. An incorrect Mg²⁺ concentration is a common source of PCR failure, potentially leading to no product, non-specific amplification (seen as multiple bands or smears on a gel), or the unintentional introduction of mutations [4]. Titrating Mg²⁺ concentration is therefore a fundamental step in PCR optimization to establish the optimal range for any new assay.

Mg2+ Effects and Titration Range

The optimal Mg²⁺ concentration is determined empirically for each primer-template combination. The following table summarizes the typical effects of Mg²⁺ concentration on PCR performance:

| Mg²⁺ Concentration | PCR Efficiency | Band Specificity | Common Artifacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Too Low (< 1.0 mM) | Low or None | N/A | No amplification, faint or absent bands on a gel. |

| Optimal (1.5 - 2.5 mM) | High | High | A single, sharp band of the expected size. |

| Sub-Optimal (3.0 - 4.0 mM) | Moderate | Reduced | Increased non-specific bands and primer-dimer formation. |

| Too High (> 4.0 mM) | High (with errors) | Very Low | A smear of non-specific DNA products and potential introduction of mutations. |

Note: A typical starting titration range is 0.5 mM to 5.0 mM [4]. The required Mg²⁺ is often supplied with the PCR buffer by the manufacturer (e.g., at 1.5 mM), but many optimization protocols require additional MgCl₂ to achieve the final optimal concentration [4].

Experimental Protocol: Mg2+ Concentration Titration

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for establishing the optimal Mg²⁺ concentration for your PCR assay.

Materials and Reagents

Organize the following reagents in a freshly filled ice bucket and allow them to thaw completely before use [4].

| Reagent | Typical Stock Concentration | Function in PCR |

|---|---|---|

| 10X PCR Buffer | 10X | Provides pH and salt conditions for the reaction. May contain initial Mg²⁺. |

| dNTP Mix | 10 mM (2.5 mM each) | Building blocks for new DNA strands. |

| Forward Primer | 20 μM | Binds to the minus strand of the DNA template. |

| Reverse Primer | 20 μM | Binds to the plus strand of the DNA template. |

| Template DNA | Variable (e.g., 2 ng/μL) | The target DNA sequence to be amplified. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | 0.5-5 U/μL | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | 25 mM | Source of free Mg²⁺ ions for reaction optimization. |

| Sterile Water | N/A | Brings the reaction to its final volume. |

Reaction Setup

- Label Tubes: Label a series of 0.2 ml thin-walled PCR tubes for your Mg²⁺ titration series (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 mM) and negative control [4].

- Prepare Master Mix: To minimize pipetting error and ensure consistency across tubes, create a Master Mix in a sterile 1.8 ml microcentrifuge tube containing all common reagents. Scale volumes according to the number of reactions plus ~10% extra [4].

Reagent Volume per 50 μL Reaction Final Concentration Sterile Water Q.S. to 50 μL - 10X PCR Buffer 5 μL 1X dNTP Mix (10 mM) 1 μL 200 μM (50 μM each) Forward Primer (20 μM) 1 μL 20 pmol per reaction Reverse Primer (20 μM) 1 μL 20 pmol per reaction Template DNA 0.5 μL ~10⁴-10⁷ molecules Taq DNA Polymerase 0.5 μL 0.5-2.5 units per reaction - Aliquot Master Mix: Gently mix the Master Mix by pipetting up and down. Dispense equal volumes into each of your labeled PCR tubes [4].

- Add MgCl₂: Add the appropriate volume of 25 mM MgCl₂ stock solution to each tube to achieve your desired final concentration series. For the negative control, add the volume of MgCl₂ corresponding to the most promising concentration and replace the template DNA with sterile water [4].

- Mix and Centrifuge: Cap the tubes and gently mix the contents. Briefly centrifuge to collect all liquid at the bottom of the tube.

Thermal Cycling and Analysis

- Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run the standard cycling program for your specific primer set [4].

- After cycling, analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Visualize the DNA bands under UV light. The optimal Mg²⁺ concentration will produce a single, bright band of the expected size with minimal to no non-specific products or primer-dimer [4].

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My PCR reaction produced no product across all Mg²⁺ concentrations. What should I check? First, verify the integrity and concentration of your template DNA. Ensure your thermal cycler block is calibrated to the correct temperatures. Confirm that all reaction components were added, and check the activity of your DNA polymerase. Running a positive control with known working primers and template is essential to isolate the problem [4].

Q2: I see a smear of non-specific DNA products on my gel. How can I improve specificity? A smear often indicates overly high Mg²⁺ concentration or non-specific primer binding. Re-run your gel to identify the tube with the least smear—this is likely closest to the optimal concentration. You can also try a hot-start DNA polymerase or increase the annealing temperature in your cycling program by 1-2°C to enhance stringency [4].

Q3: What can I do if my primers are forming dimers or secondary structures? Primer-dimer is a common issue that can be exacerbated by high Mg²⁺ concentrations. Ensure your primers are well-designed: they should be 18-25 bases long, have a G-C content of 40-60%, and not have complementary 3' ends. Using a primer design tool like NCBI Primer-BLAST can help avoid these problems. Increasing the annealing temperature can also reduce primer-dimer formation [4].

Q4: Are there any additives that can help with difficult templates? Yes, for templates with high G-C content or complex secondary structures, PCR enhancers can be added. These include DMSO (1-10%), formamide (1.25-10%), or Betaine (0.5 M to 2.5 M). These additives help to destabilize secondary structures and can significantly improve yield and specificity when used alongside optimal Mg²⁺ [4].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the most common reason for non-specific amplification (multiple bands) in a standard PCR assay? The most frequent cause is an annealing temperature that is too low, which reduces the stringency of primer-template binding and allows primers to anneal to off-target sites [10]. Other common causes include excessive magnesium ion concentration, high primer concentration, or insufficiently pure template DNA [6] [40].

How can I quickly find the optimal annealing temperature for a new primer set? The most efficient method is to use a gradient thermal cycler, which allows you to test a range of annealing temperatures simultaneously in a single run [41]. A typical initial temperature gradient spans 8–12°C, centered on the calculated melting temperature (Tm) of the primers [41].

My PCR reaction produced no product. What are the first things I should check? First, confirm that all reaction components were added correctly and that there is no contamination of reagents [40]. Then, verify the quality and quantity of your template DNA [6]. The next steps are to optimize the annealing temperature and ensure the Mg²⁺ concentration is sufficient, as low concentrations can prevent amplification [42] [40].

What does a "smeared" band on an agarose gel indicate? A smeared band typically indicates non-specific amplification or the presence of degraded DNA [43]. This often occurs when the annealing temperature is too low, leading to primers binding to non-target sequences [6]. It can also be caused by excessive template DNA or too many PCR cycles [6].

Troubleshooting Common PCR Problems

| Observation | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No Product / Low Yield [6] [40] [43] | - Poor template quality/degradation- Incorrect annealing temperature (too high)- Insufficient Mg²⁺ concentration- Missing reaction component- Too few cycles | - Re-purity template DNA; check concentration [6]- Lower annealing temperature; use gradient PCR [40]- Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration in 0.5 mM increments [42]- Verify all reagents are added [40]- Increase cycle number to 35-40 for low-copy templates [6] |

| Multiple or Non-Specific Bands [6] [40] | - Annealing temperature too low- Excess Mg²⁺, primers, or enzyme- Poor primer design- Non-hot-start polymerase | - Increase annealing temperature in 1-2°C increments [6]- Titrate Mg²⁺; lower primer concentration (0.1-0.5 µM) [42] [40]- Check primer specificity and secondary structures [10]- Use a hot-start DNA polymerase [6] |

| Primer-Dimer Formation [6] [43] | - High primer concentration- Complementary sequences in primers- Low annealing temperature- Long annealing time | - Optimize primer concentration (typically 0.1-1 µM) [6]- Re-design primers to avoid 3'-end complementarity [10]- Increase annealing temperature [43]- Shorten annealing time [6] |

| Low Fidelity (Sequence Errors) [10] [40] | - Low-fidelity polymerase (e.g., standard Taq)- Unbalanced dNTP concentrations- Excess Mg²⁺- Too many cycles | - Switch to high-fidelity enzyme (e.g., Pfu, Q5) [10] [40]- Use fresh, equimolar dNTP mix [40]- Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration [10]- Reduce number of cycles [40] |

Optimization Parameters and Protocols

Quantitative Data for PCR Optimization

Table 1: Optimization of Critical Reaction Components [10] [6] [42]

| Component | Typical Concentration Range | Optimization Guidelines | Effect of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg²⁺ | 1.5 - 2.0 mM (for Taq) [42] | Optimize in 0.2 - 1.0 mM increments [40]. Presence of EDTA or high dNTPs may require higher [Mg²⁺] [6]. | Too Low: No product [42].Too High: Non-specific products, reduced fidelity [10]. |

| Primers | 0.1 - 1 µM each [42]; Often optimal at 0.4-0.5 µM [15] | For long or degenerate primers, use ≥ 0.5 µM [6]. | Too Low: Low or no yield [6].Too High: Primer-dimers, non-specific binding [6] [42]. |

| dNTPs | 200 µM of each dNTP [42] | 50-100 µM can enhance fidelity but reduce yield [42]. | Unbalanced concentrations increase error rate [40]. |

| DNA Template | Genomic: 1 ng - 1 µg; Plasmid: 1 pg - 10 ng [42] | Higher concentrations can decrease specificity [42]. For low-copy targets, increase amount and/or cycle number [6]. | Too Low: No amplification.Too High: Non-specific amplification [6]. |

| Taq Polymerase | 0.5 - 2.0 units/50 µL reaction [42] | Increase amount if additives (e.g., DMSO) are used [6]. | Too Low: Reduced yield.Too High: Increased non-specific products [6]. |

Table 2: Standard Thermal Cycling Conditions and Adjustments [6] [42] [43]

| Step | Typical Temperature | Typical Time | Adjustments for Specific Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 95°C [42] | 2 minutes [42] | For GC-rich templates: Increase time or temperature [6]. |

| Denaturation | 95°C [42] | 15 - 30 seconds [42] | Avoid longer times to preserve polymerase activity [42]. |

| Annealing | 5°C below primer Tm (50-60°C) [42] | 15 - 30 seconds [42] | Critical for specificity. Optimize using a gradient cycler. If spurious products, increase temperature [42]. |

| Extension | 68-72°C (for Taq) [42] | 1 min/kb [42] | For products <1 kb: 45-60 seconds. For long targets (>3 kb) or high cycle numbers, increase time [42]. |

| Final Extension | 68-72°C [42] | 5 minutes [42] | Ensures all amplicons are fully replicated [6]. |