PCR Primer and Probe Design: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Validation for Researchers

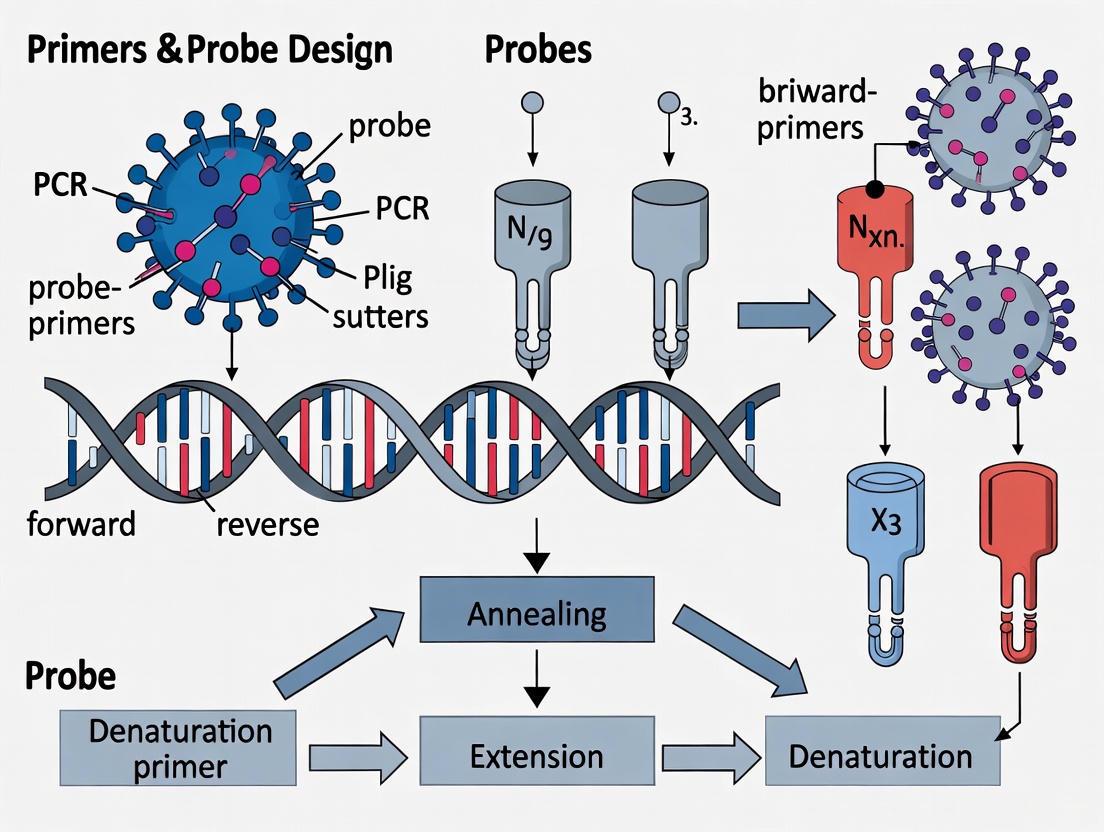

This article provides a complete framework for designing, optimizing, and validating primers and probes for PCR, qPCR, and dPCR assays.

PCR Primer and Probe Design: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Validation for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a complete framework for designing, optimizing, and validating primers and probes for PCR, qPCR, and dPCR assays. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, advanced methodologies for specific applications like bisulfite sequencing and multiplexing, systematic troubleshooting of common issues, and rigorous validation techniques adhering to MIQE guidelines. The guide synthesizes current best practices and tools to ensure the development of robust, specific, and efficient molecular assays for reliable research and diagnostic outcomes.

Core Principles of PCR Primer and Probe Design: Building a Solid Foundation

Within the broader context of primers and probe design for PCR assays, the meticulous optimization of physical and chemical parameters is fundamental to successful assay development. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) serves as a cornerstone technology in molecular biology, diagnostics, and drug development, with its efficacy critically dependent on the effective design of oligonucleotide primers. This application note details the three pivotal parameters—primer length, melting temperature (Tm), and GC content—providing researchers with structured data, detailed protocols, and practical tools to ensure robust and specific amplification in their experiments.

Parameter Specifications and Quantitative Summaries

Primer Length

Primer length directly influences both the specificity and the efficiency of primer binding. Excessively short primers can lead to nonspecific amplification, whereas overly long primers may reduce the hybridization rate and are not typically necessary for most applications [1] [2].

Table 1: Specifications for Primer Length

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Range | 18 - 30 nucleotides [1] | Balances binding efficiency with sufficient specificity for accurate targeting. |

| Typical Use | 20 - 24 nucleotides [2] | A standard length suitable for a wide array of PCR applications. |

| Impact of Short Primers | < 18 nucleotides | High risk of nonspecific amplification and inaccurate products [2]. |

| Impact of Long Primers | > 30 nucleotides | Can result in a slower hybridization rate [2]. |

Melting Temperature (Tm)

The melting temperature (Tm) is defined as the temperature at which half of the DNA duplex dissociates into single strands. It is crucial that the forward and reverse primers in a pair have closely matched Tms to ensure both bind to the template simultaneously during the annealing step [1] [3].

Table 2: Specifications for Melting Temperature (Tm)

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Tm Range | 65°C - 75°C [1] | Provides a sufficiently high temperature to promote specific hybridization. |

| Alternative Tm Range | 50°C - 60°C [2] | A common range for many standard PCR protocols. |

| Primer Pair Tm Match | Within 5°C of each other [1] [2] | Ensures both primers anneal with similar efficiency. |

| Key Influencing Factors | Primer length, nucleotide composition (GC vs. AT), and buffer conditions [1] [4] | G and C bases, which form three hydrogen bonds, result in a higher Tm than A and T bases [1]. |

GC Content

GC content refers to the percentage of nitrogenous bases in the primer that are either Guanine (G) or Cytosine (C). Since GC base pairs are stabilized by three hydrogen bonds (compared to two for AT pairs), the GC content directly affects the primer's stability and binding strength [5].

Table 3: Specifications for GC Content

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Range | 40% - 60% [1] [2] | Balances primer stability and specificity. |

| GC Clamp | 1-2 G or C bases at the 3' end [2] | Promotes stronger binding at the 3' end, which is critical for enzyme elongation. |

| Distribution | Balanced distribution of GC-rich and AT-rich domains [1] | Avoids stretches of a single base type. |

| High GC Content | >60% | May necessitate higher annealing temperatures and can promote non-specific binding or stable secondary structures [5] [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Determination

Protocol for Calculating GC Content

The GC content is a fundamental property derived directly from the primer sequence.

Procedure:

- Sequence Input: Obtain the nucleotide sequence of the primer (5' to 3').

- Base Count: Count the total number of Guanine (G) and Cytosine (C) bases within the sequence.

- Calculation: Apply the following formula:

% GC Content = (Number of G + Number of C) / Total Number of Bases in Primer) * 100 - Verification: Utilize online tools, such as the VectorBuilder GC Content Calculator, to verify manual calculations and visualize base distribution [5].

Protocol for Calculating Melting Temperature (Tm)

The Tm can be calculated using different formulas depending on the primer length. It is important to note that these are estimates, and empirical optimization may be required.

Procedure:

- Determine Primer Length (N):

N= Total number of nucleotides in the primer.

- Select the Appropriate Formula:

- For primers shorter than 14 nucleotides: Use the Wallace rule formula.

Tm = (wA + xT) * 2 + (yG + zC) * 4where w, x, y, z are the counts of A, T, G, and C bases, respectively [4]. - For primers 14 nucleotides or longer: Use the more sophisticated formula that accounts for salt concentration.

Tm = 64.9 + 41 * (yG + zC - 16.4) / (wA + xT + yG + zC)This formula assumes standard conditions of 50 nM primer and 50 mM Na+ [4].

- For primers shorter than 14 nucleotides: Use the Wallace rule formula.

- Use a Specialized Tm Calculator: For greater accuracy that incorporates specific reaction conditions (e.g., polymerase buffer composition, divalent cation concentration), use an online calculator such as the Thermo Fisher Tm Calculator [6] or the IDT OligoAnalyzer [7]. These tools employ advanced thermodynamic models for precise predictions.

Interrelationship of Primer Design Parameters

The core parameters of primer design do not function in isolation; they are intrinsically linked and must be balanced to achieve optimal PCR performance. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and primary design goals for these parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools and Reagents for Primer Design and Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Providers / Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Online Tm Calculators | Calculates primer melting temperature based on sequence and buffer conditions. Critical for determining annealing temperatures. | Thermo Fisher [6], NEB [8], IDT OligoAnalyzer [7] |

| GC Content Calculator | Determines the guanine-cytosine percentage of a primer or sequence. | VectorBuilder [5] |

| Primer Specificity Tool | Checks primer pairs for specificity against a database to minimize off-target amplification. | NCBI Primer-BLAST [9] |

| Secondary Structure Analyzer | Predicts potential hairpins or self-dimers within a primer sequence. | IDT OligoAnalyzer (Hairpin, Self-Dimer functions) [7] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzymes with proofreading activity for high-accuracy amplification of complex or GC-rich templates. | New England Biolabs (NEB), Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| HPLC-Purified Primers | High-purity oligonucleotides via High-Performance Liquid Chromatography; recommended for cloning and critical applications to reduce synthesis failure products [1] [3]. | Various oligo synthesis vendors |

Within the broader context of designing robust primers and probes for PCR assays, ensuring specificity is a cornerstone of reliable data in molecular biology research and drug development. A significant challenge to this specificity is the formation of primer secondary structures, such as hairpins, and inter-primer interactions, notably primer-dimers. These aberrant structures arise from complementary base pairing within a single primer or between two primers, effectively competing with the target DNA template during the annealing phase of the PCR [10] [11]. The consequences include reduced amplification efficiency, lower yield of the desired product, inaccurate quantification in quantitative PCR (qPCR), and potential false positives [12] [13]. This application note details the principles and protocols for designing primers that avoid these pitfalls and for experimentally troubleshooting their formation, providing essential knowledge for researchers and scientists focused on assay development.

Principles of Specific Primer Design

The foundation for avoiding secondary structures and dimerization lies in meticulous in silico primer design. Adherence to established design parameters drastically reduces the potential for non-specific interactions.

Key Design Parameters

The following parameters should be evaluated for every primer set before proceeding to experimental validation [1] [14] [15].

- Primer Length: Optimal primer length is generally 18–30 nucleotides [1] [14]. Shorter primers bind more efficiently but may lack specificity, while longer primers can hybridize too slowly.

- Melting Temperature (Tm): The Tm for both forward and reverse primers should be between 60°C and 75°C, and within 5°C of each other to ensure simultaneous and specific binding during the annealing step [1] [15].

- GC Content: Aim for a GC content of 40–60% [1] [11]. This provides sufficient sequence complexity and binding strength without promoting non-specific annealing. A maximum of 3 G or C bases in the last 5 nucleotides at the 3' end (a "GC clamp") is beneficial for specific initiation but avoid more than 3 to prevent mispriming [1] [11].

- Self-Complementarity: Primers must be screened for regions that are complementary to themselves (which can form hairpins) or to the other primer in the pair (which can form primer-dimers). The key is to minimize complementary regions, especially at the 3' end where the polymerase extends [1].

- Runs and Repeats: Avoid runs of four or more identical bases (e.g., AAAA) or dinucleotide repeats (e.g., ATATAT), as these can cause mispriming [1] [14].

Quantitative Design Thresholds

The table below summarizes the critical thresholds for key parameters to minimize secondary structures and dimer formation.

Table 1: Key Primer Design Parameters and Their Optimal Ranges

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale & Avoidance |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 18–30 nucleotides [1] [14] | Balances efficient binding and sufficient specificity. |

| Tm | 60–75°C; primers within 5°C of each other [1] [15] | Ensures simultaneous and specific annealing of both primers. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [1] [11] | Provides stable binding without excessive non-specific interactions. |

| GC Clamp | 2-3 G/C bases in the last 5 nucleotides at 3' end [1] [11] [14] | Promotes specific binding at the site of polymerase extension. |

| Self-Dimer/ Hairpin ΔG | > -9.0 kcal/mol [15] [16] | A less negative (more positive) ΔG value indicates a stable secondary structure is unlikely to form. |

| 3' Complementarity | Avoid complementarity of ≥ 3 bases between primers [1] | Prevents polymerase extension from a primer-dimer complex. |

In Silico Evaluation Workflow

A systematic workflow should be employed to design and evaluate primers prior to synthesis. The following diagram outlines the critical steps for in silico analysis.

Diagram 1: In silico primer design and evaluation workflow. Primers must pass checks for sequence composition, secondary structure potential, and specificity before being ordered.

Experimental Protocols for Detection and Optimization

Even with careful in silico design, experimental validation is crucial. This section provides protocols for detecting and troubleshooting secondary structures and primer-dimers.

Protocol: Identifying Primer-Dimers by Gel Electrophoresis

Primer-dimers can be visually identified and distinguished from the desired amplicon using agarose gel electrophoresis [10].

Key Characteristics of Primer-Dimers:

- Short Length: Typically appear below 100 bp due to the short length of the primers themselves.

- Smeary Appearance: Often manifest as a fuzzy, diffuse band rather than a sharp, well-defined one, indicating a heterogeneous mixture of nonspecific products.

Procedure:

- Prepare a standard PCR reaction mix including your primers, template, polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer.

- Critical Control: Include a No-Template Control (NTC). This reaction contains all components except the DNA template. Amplification in the NTC is almost certainly due to primer-dimer formation [10].

- Run the PCR using your initial thermal cycling parameters.

- Load the PCR products and an appropriate DNA ladder onto an agarose gel for electrophoresis.

- Run the gel longer than usual if necessary, to ensure small primer-dimer fragments are well-separated from the dye front and any specific, larger amplicons [10].

Interpretation: The desired amplicon should be a single, sharp band at the expected size, present only in the template-positive reactions. Primer-dimers will appear as a smeary band near the bottom of the gel in both test reactions and, tellingly, in the NTC.

Protocol: Using Free-Solution Conjugate Electrophoresis (FSCE) for Quantitative Dimer Analysis

For a more precise, quantitative analysis of dimerization, FSCE provides high-resolution data on primer-dimer stability under different conditions [17].

Principle: One primer is conjugated to a neutral "drag-tag" (e.g., a synthetic polyamide), which alters its electrophoretic mobility. When conjugated and non-conjugated primers form a dimer, the resulting duplex has a distinct mobility shift that can be separated and quantified using capillary electrophoresis without a sieving matrix [17].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Design primers with partial complementarity. Conjugate one primer (e.g., a 30-mer) at its 5' end with a drag-tag via a thiol-maleimide linkage [17].

- Annealing: Mix drag-tagged and non-drag-tagged primers. Heat-denature at 95°C for 5 minutes, then anneal at a defined temperature (e.g., 62°C for 10 minutes) before cooling [17].

- Electrophoresis: Load samples onto a capillary electrophoresis system using a suitable buffer (e.g., 1x TTE). Perform separations at a range of temperatures (18°C, 25°C, 40°C, 55°C, 62°C) to assess the temperature dependence of dimer formation [17].

- Analysis: Quantify the peak areas corresponding to free primers and primer-dimer complexes. The proportion of dimer formed provides a quantitative measure of dimerization risk.

Key Experimental Findings: FSCE studies have empirically demonstrated that stable primer-dimer formation requires more than 15 consecutive base pairs. Non-consecutive base pairing, even with up to 20 out of 30 possible bonds, does not typically form stable dimers. Dimerization is also inversely correlated with temperature [17].

Protocol: Optimization Strategies to Suppress Dimer Formation

If primer-dimers are detected, the following experimental optimization strategies can be employed.

- Adjust Primer Concentration: Lowering the primer concentration reduces the probability of primers encountering each other instead of the template. A typical starting range is 0.1–0.5 µM [10].

- Increase Annealing Temperature: Systematically increase the annealing temperature in 1–2°C increments. A higher temperature favors specific (perfect-match) binding and disrupts the weaker bonds in primer-dimers [10] [13].

- Utilize Hot-Start Polymerases: These enzymes remain inactive until a high-temperature activation step (e.g., 95°C), preventing non-specific extension and dimer formation during reaction setup and the initial thermal ramp [10] [13].

- Employ Touchdown PCR: This technique starts with an annealing temperature above the calculated Tm and gradually decreases it in subsequent cycles. This enriches for specific amplicons in the early cycles, which then out-compete non-specific products in later cycles.

The logical relationship between a detected problem and the available optimization strategies is outlined below.

Diagram 2: Experimental optimization strategies for troubleshooting primer-dimer formation. Strategies can be combined for greater effect.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials required for the experiments and evaluations described in this application note.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Primer Specificity Work

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that remains inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific extension and primer-dimer formation during PCR setup [10]. |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis System | Standard method for visualizing PCR products and identifying primer-dimers by size and band morphology [10]. |

| Capillary Electrophoresis System | Used for high-resolution, quantitative methods like FSCE to analyze dimer formation and purity of oligonucleotides [17]. |

| Synthetic Drag-Tags (e.g., NMEGs) | Neutral, water-soluble polymers conjugated to primers in FSCE to alter their hydrodynamic drag and enable mobility shift assays [17]. |

| Fluorophore-Labeled Nucleotides (FAM, ROX) | Used for fluorescent detection of DNA in capillary electrophoresis and real-time PCR applications [17]. |

| Primer Design Software (e.g., IDT OligoAnalyzer) | Online tools for calculating Tm, GC%, and analyzing self-dimers, hairpins, and cross-dimers via ΔG values [15] [16]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Essential for preparing all reaction mixes to prevent RNase and DNase contamination that could degrade primers and templates. |

The integrity of PCR-based data in research and diagnostic assays is fundamentally dependent on primer specificity. A rigorous, two-pronged approach combining stringent in silico design with empirical experimental validation is paramount for success. By adhering to the design principles outlined here—paying close attention to Tm, GC content, and especially complementarity—researchers can preemptively avoid the most common causes of secondary structure and dimer formation. When dimers persist, the provided experimental protocols offer a clear path for detection, from simple gel-based identification to sophisticated quantitative analysis, and for effective optimization through adjustments to reaction components and thermal cycling conditions. Integrating these strategies ensures the development of robust, specific, and efficient PCR assays, thereby solidifying the reliability of results in drug development and scientific discovery.

Melting Temperature (Tm) Calculations and the Importance of Primer Pair Matching

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, the melting temperature (Tm) is a fundamental thermodynamic property defined as the temperature at which 50% of DNA duplexes dissociate into single strands [18]. Accurate prediction and matching of primer Tm values is arguably the most critical parameter for successful experimental outcomes, influencing specificity, amplification efficiency, and yield across diverse PCR applications including quantitative PCR, multiplex PCR, and high-throughput genomic analyses [18] [19]. Proper primer pair design, grounded in robust Tm calculation methods, ensures efficient annealing while minimizing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation, thereby supporting the integrity of research in drug development and molecular diagnostics [20] [21]. This guide details the principles, calculation methods, and practical protocols for Tm determination and primer matching to support robust assay development.

Theoretical Foundations of Melting Temperature

DNA Melting Dynamics and Thermodynamic Principles

The DNA melting process involves the transition from a double-stranded helix to single-stranded random coils as temperature increases. At the Tm, an equilibrium exists where half of the duplex molecules remain hybridized and half are dissociated [18]. This transition is governed by the thermodynamics of base pairing, where GC base pairs (with three hydrogen bonds) contribute more significantly to duplex stability than AT base pairs (with two hydrogen bonds) [18].

The stability of DNA duplexes depends on several sequence and environmental factors. Sequence length directly influences Tm, with longer oligonucleotides forming more stable duplexes. The GC content significantly affects stability due to the stronger bonding in GC pairs. Additionally, nearest-neighbor interactions demonstrate that base pair stability is context-dependent, influenced by adjacent nucleotides [18]. Solution conditions such as salt concentration (Na⁺, K⁺, Mg²⁺) stabilize duplexes by shielding the negative charge of the phosphate backbone, while additives like DMSO and formamide disrupt hydrogen bonding, thereby reducing observed Tm values [18].

Evolution of Tm Calculation Methods

The accuracy of Tm prediction has evolved substantially from simple empirical formulas to sophisticated thermodynamic models [18]. The historical GC% method (Tm = 4°C × GC% + 2°C × AT%) provided rough estimates but incurred significant errors (5-10°C) due to its neglect of sequence context and terminal effects [18]. Modern approaches utilize the SantaLucia nearest-neighbor method, which accounts for all ten possible dinucleotide pairings with experimentally determined thermodynamic parameters (ΔH and ΔS), delivering precision within 1-2°C of experimental values [18]. This method calculates Tm using the formula:

Tm = ΔH / (ΔS + R × ln(C/4)) - 273.15

Where ΔH is enthalpy, ΔS is entropy, R is the gas constant, and C is the oligonucleotide concentration [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Tm Calculation Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Key Parameters Considered | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple GC% Formula | ±5-10°C error | GC content only | Rough estimations |

| Basic Nearest-Neighbor | ±3-5°C error | Sequence context | General laboratory use |

| SantaLucia Method | ±1-2°C error | Sequence context, terminal effects, salt corrections | PCR, qPCR, research applications |

Tm Calculation Methods and Protocols

Step-by-Step Protocol: Using a Modern Tm Calculator

This protocol utilizes the SantaLucia nearest-neighbor method for accurate Tm prediction, suitable for PCR primer design, qPCR optimization, and hybridization assay development [18].

Materials Required

- DNA or RNA sequence of the oligonucleotide

- Tm calculator (online or stand-alone software implementing SantaLucia method)

- Buffer composition data for your specific PCR system

Procedure

Sequence Input: Paste your oligonucleotide sequence (DNA: A, T, C, G; RNA: A, U, C, G) into the input field. The tool typically accepts sequences with or without spaces, numbers, or line breaks [18].

Sequence Type Selection: Designate whether the input sequence is DNA or RNA from the dropdown menu to ensure application of appropriate thermodynamic parameters [18].

Salt Concentration Adjustment: Set monovalent (Na⁺/K⁺) and divalent (Mg²⁺) cation concentrations according to your experimental buffer conditions [18].

- For standard PCR: 50 mM Na⁺, 1.5-2.5 mM Mg²⁺

- For high-fidelity PCR: 20-30 mM Na⁺, 1-2 mM Mg²⁺

- For qPCR: 50-100 mM Na⁺, 3-5 mM Mg²⁺

- Note: If your buffer contains both Na⁺ and K⁺, use the total monovalent cation concentration [18].

Oligonucleotide Concentration Specification: Set concentration appropriate for your application [18]:

- PCR primers: 0.1-0.5 µM (0.25 µM standard)

- qPCR primers: 0.1-0.3 µM

- Probes: 0.05-0.2 µM

Additive Adjustment (Optional): If using DMSO, input the percentage (typically 5-10% for GC-rich templates). DMSO reduces Tm by approximately 0.6-0.7°C per 1% concentration [18].

Calculation Initiation: Click "Calculate Tm" to generate results including Tm value, thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS), GC content percentage, and sequence length [18].

Experimental Validation of Calculated Tm

While computational predictions provide excellent guidance, empirical validation remains essential for critical applications. Several methods exist for experimental Tm determination:

UV Spectrophotometry with Temperature Ramp: Monitor absorbance at 260 nm while increasing temperature by 0.5-1°C per minute. The Tm corresponds to the midpoint of the hyperchromic shift [19].

SYBR Green I Fluorescence Melting Curves: After PCR amplification, slowly increase temperature while monitoring fluorescence decrease. Plot the negative derivative of fluorescence versus temperature (-dF/dT) to identify the Tm peak [21].

Calorimetric Methods: Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) provide direct thermodynamic parameter measurements but require specialized instrumentation [19].

Primer Pair Matching and PCR Optimization

The Critical Importance of Tm Matching

Successful PCR amplification requires forward and reverse primers with closely matched Tm values to hybridize simultaneously to the template during the annealing step. Significant Tm discrepancies (>5°C) between primer pairs result in inefficient amplification, where the higher-Tm primer may anneal preferentially while the lower-Tm primer exhibits reduced binding, diminishing product yield and specificity [18] [22].

Statistical analyses of PCR failure rates across 1,147 mammalian primer pairs revealed that the number of primer-template mismatches significantly impacts amplification success, with each mismatch decreasing success probability by 6-8% [22]. Furthermore, GC-content within the amplified region substantially influences outcomes, with regions exceeding 50% GC showing reduced amplification efficiency (56.9% success versus 74.2% for GC<50%) in cross-species applications [22].

Protocol for Primer Pair Evaluation and Selection

This protocol ensures selection of compatible primer pairs with matched Tm values for robust PCR amplification.

Materials Required

- Forward and reverse primer sequences

- Tm calculator

- Template sequence for specificity checking

- Primer analysis software (e.g., NCBI Primer-BLAST)

Procedure

Calculate Individual Primer Tm Values: Using the protocol in section 3.1, determine Tm for both forward and reverse primers under identical reaction conditions [18].

Assess Tm Compatibility: Select primer pairs with Tm values differing by no more than 5°C. The ideal range for both primers is 55-65°C, with 58-62°C being optimal for most applications [18] [23].

Determine Optimal Annealing Temperature: Calculate the experimental annealing temperature (Ta) as 3-5°C below the lower Tm of the two primers [18]. For touchdown PCR, begin 5-10°C above the expected Tm and decrease by 0.5-1°C per cycle until reaching the calculated Ta.

Verify Primer Specificity: Utilize NCBI Primer-BLAST to confirm primer pair specificity to the intended target sequence, checking for potential off-target binding [9].

Evaluate Secondary Structures: Analyze primers for potential hairpins, self-dimers, and cross-dimers using tools like OligoAnalyzer. Avoid primers with stable secondary structures (ΔG < -5 kcal/mol) [23].

Check 3'-End Stability: Ensure primers terminate with G or C bases (GC clamp) to enhance binding specificity at the critical 3' end where extension initiates [23].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Primer Tm Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Tm too low (<50°C) | Insufficient length, low GC content | Increase primer length to 25-30 nt, add G or C bases while maintaining 40-60% GC content |

| Tm too high (>70°C) | Excessive length, high GC content | Shorten primer to 18-22 nt, reduce GC content, or incorporate DMSO (5-10%) in reaction |

| Large Tm difference between pairs | Mismatched length or composition | Redesign one primer to match the other's Tm, adjusting length and GC content systematically |

| Non-specific amplification | Multiple binding sites, low Ta | Increase annealing temperature, verify specificity with Primer-BLAST, optimize Mg²⁺ concentration |

| Poor amplification efficiency | Secondary structures, 3' mismatches | Screen for hairpins and dimers, ensure 3' end stability, verify template quality and concentration |

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Specialized PCR Applications

Cross-Species Primer Design

When designing primers for amplification across species boundaries, additional considerations apply. Analysis of 1147 mammalian primer pairs demonstrated that amplification success significantly depends on the relatedness of the target species to the index species used for primer design [22]. The number of mismatches between index species in the primer binding region critically impacts success rates, with each mismatch decreasing amplification probability by 6-8% [22]. For cross-species applications, prioritize conserved genomic regions and verify amplification empirically across the intended species range.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Assays

qPCR applications demand exceptional primer precision to ensure accurate quantification. The MIQE guidelines emphasize the necessity of reporting primer sequences and validation data for publication [24]. For probe-based qPCR systems, the Tm of hybridization probes should be 5-10°C higher than the primer Tm to ensure probe binding precedes primer extension [21]. Statistical design of experiments (DOE) approaches can optimize probe configurations, significantly enhancing assay efficiency by up to 10% while reducing required optimization reactions [21].

High-Throughput and Multiplex PCR

In multiplex reactions employing multiple primer pairs, stringent Tm matching becomes exponentially more critical. All primers should exhibit Tm values within a 2-3°C range to ensure balanced amplification of all targets [18]. Computational prediction of PCR success using recurrent neural networks has demonstrated 70% accuracy in forecasting amplification outcomes from primer and template sequences alone, offering promising approaches for large-scale assay design [20].

Several software platforms implement robust Tm calculation algorithms suitable for research applications:

- Primer3 Plus/Primer3: Implements SantaLucia thermodynamics with comprehensive design capabilities [19]

- NCBI Primer-BLAST: Integrates Tm calculation with specificity verification against genomic databases [9]

- OligoAnalyzer Tool: Provides Tm calculation with secondary structure prediction

- Commercial primer design tools: Offer proprietary algorithms optimized for specific applications

Comparative analysis of 22 Tm calculator tools revealed that Primer3 Plus and Primer-BLAST provide the most accurate predictions, with minimal deviation from experimentally determined Tm values [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Tm Determination and PCR Optimization

| Reagent/Category | Function/Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostable DNA Polymerases | Enzymatic DNA synthesis | Selection influences buffer composition and optimal Mg²⁺ concentration |

| PCR Buffers with Mg²⁺ | Maintain pH and provide essential cofactors | Mg²⁺ concentration typically 1.5-2.5 mM; significantly impacts Tm |

| dNTP Mix | Nucleotide substrates for amplification | Standard concentration 200-250 µM each dNTP |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | Additive reducing DNA stability | Reduces Tm by 0.6-0.7°C per 1%; helpful for GC-rich templates (>60% GC) |

| Salt Solutions (KCl, (NH₄)₂SO₄) | Modifies ionic strength | Higher salt increases Tm; standard PCR: 50 mM K⁺ |

| SYBR Green I Dye | Fluorescent dsDNA binding | For melt curve analysis and experimental Tm validation |

| Commercial Tm Prediction Software | Computational Tm calculation | Implement SantaLucia method; essential for robust primer design |

Diagram 1: Primer Design and Tm Optimization Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the systematic process for designing PCR primers with optimized melting temperatures, including critical validation steps.

Annealing Temperature (Ta) Optimization for Maximum Efficiency

Within the broader context of primer and probe design research, the optimization of the annealing temperature (Ta) stands as a critical determinant for the success of any polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. Achieving maximum efficiency requires a meticulous balance, as an improperly optimized Ta can lead to nonspecific amplification, reduced yield, or complete amplification failure [15] [25]. This protocol details a systematic, stepwise approach to Ta optimization, integrating foundational principles with advanced strategies to ensure the development of robust, sensitive, and specific PCR assays suitable for demanding applications in research and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations of Annealing Temperature

The annealing temperature is defined as the temperature at which primers bind, or anneal, to the complementary target sequence in the template DNA during the PCR cycle. This step is paramount for determining the specificity and efficiency of the entire amplification reaction [26].

Relationship Between Tm and Ta

The optimal Ta is intrinsically linked to the melting temperature (Tm) of the primers. The Tm is the temperature at which 50% of the primer-template duplexes are dissociated [15]. A fundamental rule of thumb is to set the Ta 3–5°C below the calculated Tm of the primer with the lowest melting temperature [26]. This ensures sufficient stability for the primer to bind while minimizing the likelihood of non-specific binding.

- Ta Too Low: If the Ta is set excessively low, primers may tolerate mismatches and bind to non-target sequences, leading to non-specific amplification and a fuzzy background on an agarose gel [15] [25].

- Ta Too High: If the Ta is set too high, approaching or exceeding the primer's Tm, the probability of primer binding is significantly reduced. This leads to a sharp decrease in reaction efficiency and poor product yield [15].

Calculating Melting Temperature (Tm)

Accurate Tm calculation is the cornerstone of Ta optimization. Several formulas are commonly used, with varying levels of sophistication. Table 1 summarizes the most widely applied methods.

Table 1: Common Methods for Calculating Primer Melting Temperature (Tm)

| Method | Formula | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Rule of Thumb | ( Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T) ) | Quick estimation; ignores salt and primer concentration [26]. |

| Salt-Adjusted Formula | ( Tm = 81.5 + 16.6(log_{10}[Na^+]) + 0.41(\%GC) - 675/\text{primer length} ) | More accurate as it accounts for monovalent cation concentration [26]. |

| Nearest Neighbor Method | Uses thermodynamic stability of every adjacent dinucleotide pair. | Most accurate method; employed by modern online design tools (e.g., OligoAnalyzer, Primer3) [15] [26]. |

It is crucial to use the same Tm calculation method that your primer design software employs. Furthermore, the presence of PCR additives like DMSO or formamide can lower the effective Tm, necessitating a corresponding adjustment of the Ta [26].

Stepwise Optimization Protocol

A systematic approach to Ta optimization saves time and reagents while ensuring assay robustness. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive workflow, visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A systematic workflow for the stepwise optimization of annealing temperature (Ta).

Preliminary Calculations and Setup

- Tm Calculation: Use the Nearest Neighbor method within a reliable online tool (e.g., IDT OligoAnalyzer, Primer3Plus) to calculate the Tm for both the forward and reverse primer. Use your specific reaction buffer conditions (e.g., 50 mM K+, 3 mM Mg2+) for an accurate calculation [15] [27].

- Define Initial Ta and Range: The initial Ta should be set 3–5°C below the lowest Tm of the primer pair [26]. For a gradient PCR, define a range that typically spans from 8°C below to 2°C below the lowest Tm [26].

Empirical Testing via Gradient PCR

- Prepare Master Mix: Prepare a single, large-volume master mix containing all reaction components (buffer, dNTPs, MgCl2, DNA polymerase, primers, and template). Aliquot this master mix evenly across PCR tubes or a multi-well plate. This ensures that the only variable across reactions is the temperature.

- Run Gradient PCR:

- Use a thermal cycler with a verified temperature gradient capability across its block [26].

- Program the cycler with the standard steps: initial denaturation (94–98°C for 1–3 min), followed by 25–35 cycles of denaturation (94–98°C for 15–30 s), annealing (gradient range for 30–60 s), and extension (68–72°C for 1 min/kb).

- End with a final extension (72°C for 5–10 min) [26].

Analysis and Selection

- Gel Electrophoresis: Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis.

- The optimal Ta condition will typically show a single, sharp band of the expected size against a clear background with minimal to no primer-dimer formations [25].

- qPCR Efficiency Calculation (If Applicable): For quantitative PCR (qPCR), further validation is required.

- Using the selected Ta, run a qPCR reaction with a serial dilution (e.g., 1:10) of the template to generate a standard curve.

- Calculate the amplification efficiency (E) using the slope of the standard curve: ( E = (10^{-1/slope} - 1) \times 100\% ).

- Optimal efficiency falls within the range of 90–110% (with 100% being ideal), accompanied by a correlation coefficient (R²) of ≥ 0.99 [27]. This high efficiency is a prerequisite for accurate relative quantification using the 2−ΔΔCt method [27].

Fine-Tuning and Troubleshooting

- If non-specific bands are observed: Increase the Ta in increments of 1–2°C and re-run the reaction [26] [25].

- If yield is low or no product is formed: Decrease the Ta in increments of 2–3°C or verify the integrity and design of the primers and template [26].

Advanced Optimization Strategies

Design of Experiments (DOE) for Multiparameter Optimization

Annealing temperature does not function in isolation. Its interaction with other components, especially MgCl2 concentration and primer concentration, can be significant. A Design of Experiments (DOE) approach allows for the systematic evaluation of these multiple factors and their interactions simultaneously, reducing the total number of experiments required [21]. For instance, one study used DOE to optimize a probe-based qPCR assay, successfully identifying key factors and reducing the number of individual reactions from 320 to 180 [21].

The Role of MgCl2 in Ta Optimization

Magnesium ion (Mg2+) concentration is a critical cofactor for DNA polymerase and stabilizes the primer-template duplex. There is a logarithmic relationship between MgCl2 concentration and the melting temperature of DNA [28]. A meta-analysis found that for every 0.5 mM increment in MgCl2 within the 1.5–3.0 mM range, the DNA melting temperature increases, thereby influencing the optimal Ta [28]. Therefore, if Ta optimization alone fails, a complementary titration of MgCl2 concentration (typically from 1.5 mM to 5 mM) is recommended [25] [28].

Universal Annealing for High-Throughput Applications

Some specialized reaction buffers contain isostabilizing components that allow for a universal annealing temperature (e.g., 60°C) to be used with a wide range of primers with different Tms. This can circumvent the need for extensive Ta optimization in applications like high-throughput screening [26].

Experimental Validation and Case Studies

Case Study: Optimizing a TaqMan qPCR Assay for Pathogen Detection

A 2025 study on optimizing a TaqMan qPCR for diagnosing Entamoeba histolytica provides a robust example of rigorous optimization [29].

- Objective: To identify the most efficient and specific primer-probe set and establish a logical cut-off Ct value.

- Methodology: The researchers designed 20 different primer-probe sets. They evaluated amplification efficacy using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) by measuring absolute positive droplet counts and mean fluorescence intensity across different PCR cycles and annealing temperatures (59°C, 60°C, 61°C, and 62°C) [29].

- Key Finding: Of the initial five sets that showed high efficiency, only two maintained this efficiency at a higher annealing temperature of 62°C [29]. This highlights how empirical testing at different Ta values is critical for selecting the most robust assay, which may perform better under stricter thermal conditions.

Case Study: HRM Analysis for Malaria Speciation

Another 2025 study optimized a real-time PCR platform coupled with High-Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis for differentiating Plasmodium species [30].

- Protocol: The PCR was performed with an annealing temperature of 60°C.

- Outcome: The HRM method, building upon this optimized PCR, achieved a significant Tm difference of 2.73°C between P. falciparum and P. vivax, allowing for clear species differentiation. The results showed complete agreement with sequencing, validating the optimized protocol's accuracy [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Annealing Temperature Optimization

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Ta Optimization | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Provides robust activity and reduces mispriming at suboptimal Ta. | Enzymes from Archaea (e.g., Pfu) offer high thermostability for challenging conditions [26]. |

| Specialized PCR Buffers | Provides optimal pH and salt conditions; some enable universal annealing. | Buffers with isostabilizing components allow for a universal Ta (e.g., 60°C) [26]. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Critical cofactor; concentration directly influences Tm and primer binding. | Requires titration (0.5-5.0 mM) in conjunction with Ta optimization [25] [28]. |

| PCR Enhancers | Can alter Tm and facilitate amplification of difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich). | DMSO, betaine, glycerol. Note: These typically lower the effective Ta [26]. |

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Allows empirical testing of a temperature range in a single run. | Essential for efficient optimization. "Better-than-gradient" blocks provide precise well-level control [26]. |

| Online Tm Calculator | Calculates theoretical Tm using the Nearest Neighbor method. | IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool; use specific reaction conditions for accuracy [15]. |

| qPCR Standard Curve Materials | Validates amplification efficiency of the selected Ta. | Serial dilutions of a known template concentration are required [27]. |

The optimization of annealing temperature is a non-negotiable step in the development of a reliable PCR assay. By moving beyond simple calculations and adopting a systematic, empirical approach—starting with a temperature gradient and validating with efficiency calculations—researchers can achieve maximum amplification efficiency and specificity. Furthermore, considering the interplay of Ta with other reaction components, such as Mg2+ concentration, and leveraging advanced strategies like DOE, ensures the development of robust assays capable of meeting the stringent demands of modern scientific research and drug development.

The design of amplicons—the specific DNA sequences amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)—is a foundational step in developing robust molecular assays. Among design parameters, amplicon length is a critical determinant of success, directly influencing amplification efficiency, specificity, and sensitivity. This parameter becomes especially crucial when working with fragmented DNA, a common characteristic of samples derived from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, ancient DNA, and clinically relevant sources like cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from liquid biopsies [31]. In such contexts, the natural fragmentation of the DNA template imposes strict limitations on the maximum achievable amplicon size.

The relationship between amplicon length and template quality is not merely a technical consideration but a central principle in assay design. For instance, plasma cfDNA fragments exhibit a characteristic peak at approximately 167 base pairs (bp), reflecting nucleosomal protection [31]. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is often even shorter, presenting an opportunity for selective enrichment by designing shorter amplicons [31]. Failure to align amplicon length with the integrity of the source DNA can lead to drastic reductions in sensitivity or complete amplification failure. This application note details the strategic considerations and practical protocols for designing amplicons that are optimized for length, with a specific focus on challenging, fragmented DNA samples.

Core Principles of Amplicon Length Selection

General Guidelines for Different PCR Applications

The optimal amplicon length varies significantly depending on the specific PCR application and the quality of the starting template. The table below summarizes standard amplicon length recommendations for various common techniques.

Table 1: Recommended Amplicon Lengths for Various PCR Applications

| PCR Application | Recommended Amplicon Length | Key Considerations and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Standard PCR | 200 – 1000 bp [32] | Balances amplification efficiency with product specificity. Longer products may require increased extension times. |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | 75 – 150 bp [32] | Shorter lengths promote high amplification efficiency and robust kinetics essential for accurate quantification. |

| Assays on Fragmented DNA (e.g., cfDNA, FFPE) | 70 – 140 bp [33] | Maximizes the probability of amplifying an intact target sequence from a fragmented DNA population. |

| Bisulfite PCR | 70 – 300 bp [33] | Bisulfite conversion is a harsh process that fragments and damages DNA, making shorter amplicons more reliable. |

| Long-Range PCR | > 3-4 kb [34] | Requires specialized polymerases and optimized cycling conditions to overcome challenges like depurination. |

The Critical Impact of Fragmented DNA

Fragmented DNA necessitates a paradigm shift in amplicon design. In standard PCR with high-quality genomic DNA, longer amplicons are often feasible. However, when the DNA template is degraded, the effective template length is determined by the size of the fragments, not the original genome.

- Liquid Biopsies and cfDNA: In non-invasive diagnostics using plasma cfDNA, the average fragment size is ~167 bp. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has been reported to be even shorter than cfDNA from healthy cells [31]. Designing amplicons that are shorter than the average fragment length is therefore essential to ensure a high probability that a given molecule is intact and can be amplified. For qPCR assays on such samples, amplicons of 70-140 bp are generally ideal [33].

- Bisulfite-Converted DNA: The chemical process of bisulfite conversion, used for methylation analysis, causes significant DNA fragmentation and damage. Consequently, PCR from bisulfite-converted DNA is more successful with shorter amplicons, typically kept between 70-300 bp, and often requires an increased number of PCR cycles (35-40) to compensate for the damaged template [33].

- Fundamental Design Rule: The guiding principle is to keep the amplicon shorter than the average DNA fragment size in the sample. This increases the likelihood that the entire region between the two primer binding sites is intact, allowing for successful amplification.

Experimental Protocols for Fragmented DNA Targets

Protocol 1: qPCR Assay Design for Cell-Free DNA

This protocol is optimized for generating short amplicons from cfDNA, such as from blood plasma, for sensitive detection in liquid biopsy applications [31] [33].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Template Assessment:

- Quantify and qualify the cfDNA using a high-sensitivity instrument (e.g., Bioanalyzer, TapeStation). Confirm the peak fragment size distribution is around 150-200 bp.

- Critical Step: Use this size profile to define the maximum allowable amplicon length.

Primer and Probe Design:

- Amplicon Length: Design the amplicon to be between 70 and 140 bp [33]. This ensures the amplicon is shorter than the majority of cfDNA fragments.

- Primer Length: Keep primers between 18-22 base pairs.

- Melting Temperature (Tm): Maintain the Tm of each primer between 55–70°C, with forward and reverse primers within 2°C of each other [33].

- GC Content: Design primers with a GC content of 40–60% without long stretches (>4) of the same nucleotide.

- Probe Design (for TaqMan): If using a hydrolysis probe, its Tm should be 4–8°C higher than the primers, and its length should be 20-25 bp [33].

In Silico Validation:

- Check primer sequences for self-complementarity, hairpins, and primer-dimer formation using tools like Primer3.

- Verify primer specificity by performing a BLAST search against the host genome (e.g., hg38 for human) to ensure binding is unique to the target [33].

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a 20 µL reaction mix containing:

- 1X Hot-Start DNA Polymerase Master Mix (e.g., ZymoTaq)

- Forward and Reverse Primers: 0.3–1 µM each

- Probe (if applicable): 0.1–0.3 µM

- 5–20 ng of cfDNA template

- Use a high-sensitivity, hot-start polymerase to minimize nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation, which is critical for low-input samples.

- Prepare a 20 µL reaction mix containing:

Thermal Cycling:

- Use the following cycling conditions on a real-time PCR instrument:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2–5 minutes

- 40–45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 10–15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 30–60 seconds (acquire fluorescence here)

- The high cycle number compensates for the low abundance of the specific target in cfDNA.

- Use the following cycling conditions on a real-time PCR instrument:

Protocol 2: Long-Range Amplicon Sequencing for Structural Variation Analysis

This protocol is adapted for situations where longer amplicons are necessary, such as for sequencing to detect large deletions or structural variants, even from potentially compromised templates [35]. It emphasizes overcoming fragmentation challenges.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

DNA Extraction and Long-Range PCR:

- Extract genomic DNA from your sample source (e.g., cell lines, primary cells).

- Perform long-range PCR to amplify a target region of 10–15 kb.

- Polymerase Selection: Use a high-fidelity, proofreading polymerase with minimal length bias, such as KOD (Multi & Epi) DNA polymerase, which has been shown to perform well for this application [35].

- Reaction Composition: Follow the manufacturer's recommendations for long-range PCR. This often includes balanced dNTP and Mg²⁺ concentrations, and potentially additives like DMSO for GC-rich regions.

- Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes.

- 30-35 Cycles of:

- Final Extension: 68°C for 5–10 minutes.

Amplicon Purification and Quality Control:

- Purify the PCR product using a magnetic bead-based clean-up system (e.g., AMPure XP beads) to remove primers, enzymes, and salts.

- Quantify the purified amplicon using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) and check its integrity by agarose gel electrophoresis or a Fragment Analyzer.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Fragment the purified long-range amplicon to ~300 bp using mechanical or enzymatic fragmentation.

- Prepare a sequencing library using a standard kit for Illumina platforms, including end-repair, dA-tailing, adapter ligation, and PCR enrichment steps.

- Sequence the library on an Illumina platform (e.g., MiSeq, NextSeq) to generate high-accuracy short reads.

Data Analysis for Large Variants:

- Analyze the sequencing data using a specialized tool like the ExCas-Analyzer, a k-mer alignment algorithm developed to simultaneously detect both small indels and large deletions (>100 bp) from long-range amplicon sequencing data [35].

- Standard genome aligners like BWA-mem may not be as sensitive for this specific application when dealing with large, complex indels near the CRISPR-cut site or target region.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful amplicon generation, especially from fragmented DNA, relies on a carefully selected set of reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for this field.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Amplicon-Based Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Sensitivity DNA Polymerase | Enzyme engineered for robust amplification from low-input and suboptimal templates. | Essential for qPCR of rare targets in cfDNA. Reduces primer-dimer formation [33]. |

| Proofreading DNA Polymerase | Enzyme with 3' to 5' exonuclease activity for high-fidelity synthesis of long amplicons. | Critical for long-range PCR to correct nucleotide misincorporations and ensure sequence accuracy [34]. |

| AMPure XP Beads | Magnetic beads for solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) to purify and size-select DNA. | Used for post-PCR clean-up to remove primers and salts, and for library normalization in NGS workflows [36]. |

| ExCas-Analyzer Software | A dedicated k-mer alignment algorithm for analyzing long-range amplicon sequencing data. | Specifically detects both small indels and large deletions (>100 bp) with high accuracy and speed [35]. |

| Rapid Barcoding Kit (Oxford Nanopore) | Enables quick library preparation and multiplexing of amplicons for long-read sequencing. | Optimized for 500 bp to 5 kb amplicons; allows for sequencing of full-length fragments to check for mutations [36]. |

Strategic amplicon design, with length as a primary consideration, is a cornerstone of successful molecular assay development. The presented frameworks and protocols provide a roadmap for designing effective PCR-based assays across a spectrum of applications, from the highly sensitive detection of short cfDNA fragments in oncology to the sequencing of long amplicons for genetic variation studies. By aligning amplicon length with the biological and physical characteristics of the DNA template—especially its fragmentation profile—researchers and drug developers can significantly enhance the sensitivity, accuracy, and reliability of their genetic analyses. Adhering to these principles ensures that PCR assays are built on a robust foundation, ultimately leading to more dependable data and conclusions in both research and clinical settings.

Advanced Application-Specific Design: qPCR, RT-qPCR, Bisulfite, and Multiplexing

Within the broader context of PCR assay research, the design of TaqMan probes is a critical determinant for the success of quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). These hydrolysis probes leverage the 5' nuclease activity of Taq polymerase to provide exceptional specificity and sensitivity for detecting and quantifying nucleic acid targets [37]. The reliability of this technique in diverse fields, from clinical diagnostics to fundamental gene expression analysis, is contingent upon a meticulously optimized primer-probe set [38]. This document outlines comprehensive application notes and protocols for designing TaqMan assays, with a focused examination of fluorophore and quencher selection, strategies to ensure target specificity, and detailed experimental methodologies.

Core Principles of TaqMan Probe Design

A TaqMan assay consists of a forward primer, a reverse primer, and a single-stranded DNA probe that is complementary to a specific sequence located between the two primer binding sites [39]. The probe is dual-labeled with a reporter fluorophore at its 5' end and a quencher molecule at its 3' end [40]. When the probe is intact, the proximity of the quencher to the reporter suppresses the reporter's fluorescence through a mechanism called Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) [37].

During the PCR amplification process, the TaqMan probe anneals to its specific target. As the Taq polymerase extends the primer, it encounters the bound probe and cleaves it via its 5' exonuclease activity. This cleavage separates the reporter dye from the quencher, leading to a permanent increase in fluorescence that is proportional to the amount of amplicon synthesized [37]. This process repeats every cycle, generating a fluorescent signal that directly correlates with the accumulation of the PCR product, without inhibiting the amplification itself [40] [37].

Visualizing the TaqMan Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the step-by-step mechanism of the TaqMan probe hydrolysis during PCR amplification.

Fluorophore and Quencher Selection

The careful selection of the reporter fluorophore and quencher is paramount for achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio and for enabling multiplex assays where multiple targets are detected in a single reaction.

Reporter Fluorophores

Reporter dyes are characterized by their brightness, which is a product of their molar extinction coefficient and fluorescence quantum yield [41]. When selecting a fluorophore, researchers must balance optical performance with practical considerations like pH stability, photostability, and compatibility with the available real-time PCR instrument [41].

- Common Dyes: 6-FAM is the most frequently used reporter due to its high brightness [41]. Other common alternatives include VIC, TET, HEX, NED, ABY, and JUN [39] [42].

- Instrument Compatibility: Each qPCR instrument is equipped with a specific set of optical filters. It is essential to verify that the emission spectrum of the chosen reporter dye matches the instrument's detection capabilities. The table below summarizes compatible dyes for various common instruments [39] [42].

- Advanced Dyes: For challenging applications, dyes from the Alexa Fluor or ATTO series offer enhanced photostability and resistance to environmental factors like ozone, which can degrade traditional cyanine dyes (e.g., Cy5) [41].

Quenchers

The quencher's role is to absorb the energy from the reporter dye when they are in close proximity. Quenchers fall into two main categories: non-fluorescent quenchers (NFQs) and fluorescent quenchers.

- Non-Fluorescent Quenchers (NFQs): These are highly recommended because they do not emit background fluorescence, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio and making them ideal for multiplexing [39]. NFQs are often paired with specific modifications:

- MGB-NFQ: A Minor Groove Binder (MGB) moiety is conjugated to the NFQ. This stabilizes the probe's binding to the DNA, allowing for the use of shorter, more specific probes while maintaining a high melting temperature (Tm). This is especially beneficial for discriminating single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [39].

- QSY Quencher: This is a non-fluorescent quencher without an MGB group. It is particularly suited for multiplexing three or more targets, as it offers high quenching efficiency without fluorescence [39].

- Fluorescent Quenchers: An example is TAMRA, which is a weakly fluorescent quencher. Its use consumes one of the instrument's detection channels in a multiplex setup and is generally less favored than NFQs [39].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their functions essential for TaqMan assay design and execution.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for TaqMan Assays

| Reagent Solution | Function & Description |

|---|---|

| Custom TaqMan Assays | Pre-mixed solutions containing forward primer, reverse primer, and a TaqMan probe with a specified fluorophore and quencher [39]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme with both polymerase and 5' nuclease activity, essential for DNA amplification and probe hydrolysis [37]. |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for DNA synthesis. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Optimized buffer solution containing Taq polymerase, dNTPs, salts (MgCl₂, KCl), and a passive reference dye (e.g., ROX) [39]. |

| TE Buffer (pH 8.0) | Resuspension buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA) for lyophilized probes, ensuring stability and longevity [39] [42]. |

Instrument and Dye Compatibility

Selecting a fluorophore that is compatible with the detection system of your qPCR instrument is critical. The table below provides a reference for dye compatibility across common platforms.

Table 2: qPCR Instrument Dye Compatibility Guide

| qPCR Instrument | Number of Filters | Passive Reference Dye | Compatible Reporter Dyes |

|---|---|---|---|

| StepOnePlus | 4 | ROX | FAM, VIC, NED [39] |

| 7500/7500 Fast | 5 | ROX* | FAM, VIC, NED, ABY, JUN [39] |

| QuantStudio 7 Flex | 6 | ROX* | FAM, VIC, NED, ABY, JUN [39] |

| QuantStudio 5 | 5-6 | ROX* | FAM, VIC, NED, ABY, JUN [39] |

| Bio-Rad CFX 96 | - | - | 6-FAM, HEX, ROX, Texas Red, Cy5 [42] |

Note: If JUN is used as a custom probe, MUSTANG PURPLE dye should be used as the passive reference instead of ROX [39].

Ensuring Specificity and Sensitivity

A well-designed TaqMan assay must be highly specific for the intended target and highly sensitive to detect low-copy numbers.

Target Sequence Evaluation

- Sequence Uniqueness: The designed probe and primer sequences must be unique to the target gene to avoid cross-homology with other sequences, such as related genes or pseudogenes. Always perform a BLAST search to verify specificity against the relevant transcriptome or genome [38] [15].

- Avoiding Genomic DNA Amplification: To prevent false positives from genomic DNA (gDNA) contamination, design assays to span an exon-exon junction. Ideally, the probe itself should be placed across the junction, with primers binding in separate exons. This ensures the signal is generated only from correctly spliced cDNA [38] [40].

- Sequence Purity: The target region should be unambiguous, without known single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), repeat sequences, or secondary structures that could hinder probe binding [38].

Primer and Probe Design Parameters

Adherence to established design parameters is crucial for robust assay performance. The following workflow outlines the key steps and considerations for in-silico design.

Primer Design Guidelines

- Melting Temperature (Tm): The optimal Tm for both forward and reverse primers is 58–60°C, and their Tms should not differ by more than 1-2°C [38] [40] [43]. This ensures simultaneous and efficient binding.

- Length and GC Content: Primers should be 15-30 bases long with a GC content of 30-80% (ideal is 50%) [15] [43]. Avoid runs of four or more identical nucleotides, especially guanines [38].

- 3' End Stability: The last five nucleotides at the 3' end should contain no more than two G or C bases (a weak "GC clamp") to reduce non-specific priming [40] [43].

Probe Design Guidelines

- Melting Temperature (Tm): The probe Tm should be 8–10°C higher than the primer Tm (typically 68–70°C) [38] [43] [37]. This ensures the probe hybridizes to the template before the primers during the annealing phase.

- Length and Sequence: Probes are typically 18-30 bases long [40] [15]. They should not begin with a guanine (G) base, as it can quench the reporter dye even after cleavage [40] [15]. The probe should have more cytosines (C) than guanines (G) [40] [43].

- Amplicon Characteristics: The amplified product (amplicon) should be short, ideally 50–150 base pairs, to promote efficient amplification [38] [40]. The probe must be located between the primer binding sites without overlapping them [15].

Experimental Protocol: Design and Validation

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for designing and validating a custom TaqMan gene expression assay.

In-Silico Design Workflow

- Sequence Acquisition and Preparation: Obtain the full mRNA transcript sequence of your target gene from a reliable database (e.g., NCBI RefSeq). Annotate the exon boundaries if possible.

- Target Region Selection: Identify a candidate region of 50-150 bp that spans an exon-exon junction. Verify the uniqueness of this region using a nucleotide BLAST search against the appropriate genome to ensure no significant homology with other sequences [38] [44].

- Oligonucleotide Design: Utilize specialized software (e.g., Primer Express, Beacon Designer, or the built-in tools in Geneious Prime) to design the primer and probe set [38] [40] [43]. Input the following parameters:

- Primer Tm: 58–60°C

- Probe Tm: 68–70°C

- Amplicon Length: 50–150 bp

- GC Content: 30–80% for all oligonucleotides

- In-Silico Quality Control: Analyze the proposed oligonucleotide sequences for self-dimers, heterodimers, and hairpin secondary structures using tools like the IDT OligoAnalyzer. The ΔG for any secondary structure should be weaker (more positive) than –9.0 kcal/mol [15].

Wet-Lab Validation Procedures

After synthesizing and resuspending the oligonucleotides, empirical validation is essential.

- Reconstitution and Storage: Resuspend lyophilized primers and probes in TE buffer (pH 8.0 for FAM-labeled probes; pH 7.0 for Cy5-labeled probes) to a stock concentration of 100 µM [39] [42]. Aliquot the stock solutions into smaller, single-use volumes to minimize freeze-thaw cycles (recommended limit: no more than 10 cycles) and store at –20°C or lower in dark tubes to protect from light [39] [42].

- Assay Optimization: Perform a preliminary qPCR run using universal conditions (e.g., primer concentration at 900 nM and probe concentration at 250 nM) [38]. Use a serial dilution of a template with known concentration to generate a standard curve.

- Specificity and Sensitivity Assessment:

- Analyze the Standard Curve: The ideal assay will have a reaction efficiency between 90% and 110% (corresponding to a slope of -3.6 to -3.1) and a correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.99 [44].

- Include Controls: Always run a no-template control (NTC) to check for contamination and a no-reverse-transcriptase control (-RT control) to confirm the absence of genomic DNA amplification [38].

- Specificity Verification: The amplification plot should show a single, sharp logarithmic phase. Perform melt curve analysis only if using DNA-binding dyes; for TaqMan, the probe itself confers specificity, and a single peak confirms specific amplification.

The rigorous design of TaqMan probes, grounded in the principles outlined in this document, is fundamental to generating precise and reliable qPCR data. The synergistic selection of appropriate fluorophore-quencher pairs, combined with bioinformatic strategies to ensure absolute target specificity and adherence to established design parameters, forms the foundation of a robust assay. By following the detailed experimental protocols for in-silico design and wet-lab validation, researchers and drug development professionals can develop highly sensitive and specific TaqMan assays. These optimized assays are capable of meeting the stringent demands of modern molecular biology and clinical diagnostics, thereby contributing valuable and reproducible results to their research endeavors.

Within the broader context of primer and probe design research for PCR assays, the accurate quantification of gene expression via reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) remains a cornerstone of molecular biology and drug development. A fundamental challenge in this technique is ensuring that the amplification signal originates specifically from cDNA, without spurious amplification from contaminating genomic DNA (gDNA). The design of primers that span exon-exon junctions is a critical strategy to achieve this specificity, thereby guaranteeing the reliability of data used in basic research and clinical decision-making. This Application Note provides a detailed protocol for designing and validating such primers, incorporating robust experimental methodologies and current bioinformatic tools to support researchers in developing high-fidelity assays.

Principles of Exon-Exon Junction Targeting

In eukaryotic genes, the coding sequences (exons) are separated by non-coding introns. During transcription, introns are spliced out to form mature mRNA. A primer designed to span an exon-exon junction will find a complementary sequence only in the spliced, mature mRNA (cDNA after reverse transcription). It will not bind to genomic DNA, where the intron sequence is still present, thereby preventing its amplification [45]. This principle is visually summarized in the diagram below.

Primer Design Parameters and Criteria

Successful primer design hinges on adhering to strict biochemical parameters. The following table summarizes the critical quantitative criteria for designing effective exon-exon junction primers, as recommended by leading sources [46] [45] [47].

Table 1: Key Design Parameters for Exon-Exon Junction Primers

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Rationale & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Amplicon Length | 70–150 bp [46] [45] | Shorter amplicons maximize PCR efficiency and reduce amplification time. |

| Primer Length | 18–30 nucleotides [46] [45] | Balances specificity and efficient binding. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [46] [45] | Ideal for stable primer-template binding; avoid extremes. |

| Primer Melting Temperature (Tm) | 60–64°C [45] | Forward and reverse primer Tm should be within 2-3°C of each other [46]. |

| Junction Overlap | 5' and 3' sides of the junction [9] | Ensures the primer is specific to the spliced sequence; the 3' end should be placed on the junction for maximum specificity. |

| Amplicon GC Content | 40–60% [46] | Avoids excessive secondary structure in the amplicon. |

In addition to the parameters in Table 1, several qualitative rules must be followed:

- Avoid Secondary Structures: Primers must be screened to avoid hairpins, self-dimers, and cross-dimers [46] [47].

- 3'-End Stability: The 3' end should not be rich in G or C repeats (e.g., ≥4 Gs) to prevent mispriming [46] [45].

- Specificity Check: Primer sequences must be validated for target specificity using tools like BLAST to ensure they do not bind to unrelated sequences [47].

Bioinformatics Tools for Primer Design

Several software tools automate the complex process of primer design, integrating specificity checks and parameter validation. The following table compares the most relevant tools for designing exon-junction primers.

Table 2: Comparison of Bioinformatics Tools for Junction Primer Design

| Tool Name | Access | Key Features for Junction Design | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| ExonSurfer [48] [49] | Web tool | Automatically selects optimal exon junctions; avoids common SNPs; performs genomic DNA BLAST for specificity. | Researchers seeking a dedicated, end-to-end RT-qPCR primer design solution with variant avoidance. |

| NCBI Primer-BLAST [9] | Web tool | "Primer must span an exon-exon junction" option; integrates Primer3 with BLAST specificity check. | Users wanting a highly customizable, widely trusted tool with direct database integration. |

| PrimerQuest (IDT) [50] [45] | Web tool | Customizable design for qPCR with intercalating dyes; allows specification of primer locations. | Scientists who also need to order synthesized oligos from the same platform. |

| RealTimeDesign [51] | Web tool | Designs probes and primers for gene expression; offers both express and custom modes. | Users designing probe-based assays alongside SYBR Green. |

Workflow for Using Bioinformatics Tools

A generalized, effective workflow for using these tools is outlined in the diagram below.

Experimental Protocol: Validation of Exon-Exon Junction Primers

Once primers are designed in silico, rigorous wet-lab validation is essential. The following protocol uses a one-step RT-qPCR setup for efficiency.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA Template | Input material; purified RNA with A260/A280 ~1.8-2.1 and high RIN is crucial [52]. |

| One-Step RT-qPCR Kit | Integrates reverse transcription and PCR in a single tube, reducing variability [46] [52]. |

| DNase I Treatment | Digests residual genomic DNA in the RNA sample, providing an additional layer of specificity [46]. |

| No Template Control (NTC) | Contains water instead of template; controls for reagent contamination. |

| No Luna RT Control (-RT Control) | Reaction setup without reverse transcriptase; crucial for detecting gDNA contamination [46]. |

| Thermolabile UDG | Enzyme that prevents carryover contamination from previous PCR products; can be added to the reaction mix [46]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

RNA Preparation and Quality Control:

- Extract total RNA using a validated method (e.g., silica-column based kits like RNeasy Mini Kit).

- Treat RNA samples with DNase I to eliminate genomic DNA contamination [46].

- Assess RNA purity spectrophotometrically (A260/A280 ratio of ~1.8-2.1; A260/A230 > 2) and integrity (e.g., RIN > 8) using a microfluidic bioanalyzer [52].

One-Step RT-qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Perform reactions in triplicate in a 96-well or 384-well plate.

- Prepare a master mix for each primer set containing the following components. Gently mix and briefly centrifuge.

- Keep reactions on ice until thermocycling begins.

Table 4: Example 20 µL Reaction Setup using a Commercial Kit

Component Final Concentration/Amount 2X One-Step RT-qPCR Master Mix 10 µL Forward Primer (e.g., 10 µM stock) 0.8 µL (400 nM) Reverse Primer (e.g., 10 µM stock) 0.8 µL (400 nM) RNA Template 100 ng – 10 pg (e.g., 2 µL of 50 ng/µL) Nuclease-Free Water To 20 µL Thermocycling Conditions:

- Use the following cycling protocol, based on recommendations for the Luna One-Step RT-qPCR Kit [46]. The "Fast" ramp speed on compatible instruments is recommended.

Table 5: Standard Thermocycling Protocol

Step Temperature Time Cycles Purpose Reverse Transcription 55°C 10–30 min 1 cDNA synthesis Hot Start Activation 95°C 10 min 1 Polymerase activation Amplification 95°C 15 sec 40-45 Denaturation 60–68°C 15–30 sec Annealing/Extension* Melt Curve 65–95°C Increment 0.5°C 1 For SYBR Green assays Note: The annealing/extension temperature and time can be optimized. A combined step at 60–68°C for 15–30 sec is often sufficient for short amplicons [46] [52].

Data Analysis and Assay Validation:

- Specificity Check: Analyze the melt curve for SYBR Green assays. A single, sharp peak indicates specific amplification of a single product. The presence of multiple peaks or shoulders suggests primer-dimer formation or non-specific amplification [47].

- Efficiency Calculation: Perform a 10-fold serial dilution of the template (e.g., 100 ng to 0.1 ng total RNA) to generate a standard curve. The slope of the plot of Cq vs. log(quantity) is used to calculate PCR efficiency (E) using the formula: E = [10^(-1/slope)] - 1. An efficiency between 90–110% (slope of -3.1 to -3.6) is ideal, with a coefficient of determination (R²) ≥ 0.99 [46].

- -RT Control: The -RT control must show a significantly delayed Cq (ideally, no amplification) compared to the test reaction, confirming the absence of gDNA amplification.

Advanced Application: Quantifying Splice Variants

The principles of junction-targeting can be extended to precisely quantify alternative splice variants. A robust method involves using three primer pairs per gene [52]:

- Variant 1-specific pair: Amplifies only the first isoform.

- Variant 2-specific pair: Amplifies only the second isoform.

- Common pair: Amplifies a constitutive region present in both isoforms.

The common pair serves as an internal control for total transcript abundance and reverse transcription efficiency. The relative incidence of each variant is calculated by comparing its specific amplification to the common amplification, providing a highly reliable quantification that accounts for technical variations [52].

Troubleshooting Guide

- No Amplification or Late Cq: Check RNA integrity and purity; verify primer specificity and ensure the Tm is appropriate for the cycling conditions; test a wider range of RNA input concentrations.

- Multiple Peaks in Melt Curve: Redesign primers to avoid secondary structures and dimers; optimize primer concentration (typically 100–900 nM); consider using a hot-start polymerase to reduce non-specific amplification [46].

- Amplification in -RT Control: Re-treat RNA sample with DNase I; consider designing primers that span a larger intron or using a thermolabile UDG treatment to degrade carryover contamination [46].

- Low PCR Efficiency (<90% or >110%): Verify primer design, especially at the 3' ends; ensure amplicon is short (70–150 bp) and lacks complex secondary structure; prepare fresh template dilutions [46].