Overcoming the Hurdle: Why Gram-Positive Bacteria Are Tough to Lyse and Modern Solutions

The efficient lysis of Gram-positive bacteria remains a significant challenge in microbiology, molecular biology, and drug development due to their thick, multi-layered peptidoglycan cell wall.

Overcoming the Hurdle: Why Gram-Positive Bacteria Are Tough to Lyse and Modern Solutions

Abstract

The efficient lysis of Gram-positive bacteria remains a significant challenge in microbiology, molecular biology, and drug development due to their thick, multi-layered peptidoglycan cell wall. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and industry professionals, exploring the structural foundations of this resilience and examining a suite of methodological approaches—from enzymatic and mechanical to electrochemical and chemical. It offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance lysis efficiency and includes a comparative validation of different techniques. The content synthesizes current research and emerging technologies, including engineered endolysins and hybrid methods, to present a clear path forward for improving diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes.

The Structural Fortress: Understanding the Gram-Positive Bacterial Cell Wall

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why is my protocol ineffective for lysing Gram-positive bacteria? The primary challenge is the thick, multi-layered peptidoglycan wall in Gram-positive envelopes, which acts as a formidable physical barrier [1] [2]. The peptidoglycan layer in Gram-positive bacteria is significantly thicker than in Gram-negatives, making it more resistant to mechanical disruption and standard lytic enzymes [1]. Furthermore, the presence of teichoic acids woven into the peptidoglycan matrix adds structural integrity and a negative charge, further increasing resistance to enzymatic degradation [1] [3].

FAQ 2: How can I enhance lysozyme efficacy against Gram-negative cells? Lysozyme alone is often insufficient for Gram-negative bacteria because its access to the thin peptidoglycan layer is blocked by the outer membrane [1]. Research shows that the enzymatic lysis of Gram-negative bacteria like E. coli by lysozyme is significantly increased in the presence of glycine and basic amino acids (e.g., histidine, lysine, arginine) [4]. These additives are thought to help disrupt the outer membrane, thereby permitting lysozyme to reach and degrade the underlying peptidoglycan. Pre-treatment with a chelating agent like EDTA is also a common strategy to disrupt the divalent cation-stabilized outer membrane.

FAQ 3: What is the impact of covalent immobilization of lysozyme? Covalent immobilization of lysozyme alters its interaction with bacterial cells. Immobilized lysozyme shows a broader pH optimum for activity and increased Michaelis constant (Km) values, indicating a lower binding affinity for bacterial cell wall substrates. The Km increase is more pronounced for lysis of Gram-positive Micrococcus luteus (4.6-fold increase) than for Gram-negative E. coli (1.5-fold increase) [4]. Additionally, the beneficial effects of amino acids like glycine on lysis kinetics are significantly reduced when using the immobilized enzyme, which may be due to external diffusion limitations at lower bacterial concentrations[cite:2].

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Data

Table 1: Structural Composition of Bacterial Cell Envelopes

| Feature | Gram-Positive Envelope | Gram-Negative Envelope |

|---|---|---|

| Peptidoglycan Layer | Thick (multi-layered) [1] [2] | Thin (single-layer or few layers) [1] [2] |

| Outer Membrane | Absent [1] | Present (asymmetric bilayer with LPS) [1] |

| Teichoic Acids | Present (embedded in peptidoglycan) [1] | Absent [1] |

| Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) | Absent [2] | Present (in outer leaflet of outer membrane) [1] [3] |

| Periplasmic Space | Absent or minimal [1] | Present (between inner and outer membranes) [1] |

| Representative Model Organisms | Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis [1] | Escherichia coli, Salmonella [1] |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Immobilized vs. Native Lysozyme*

| Parameter | Native Lysozyme | Covalently Immobilized Lysozyme |

|---|---|---|

| pH Optimum | Narrow [4] | Broadened [4] |

| Michaelis Constant (K |

Baseline (1x) | 1.5x increase [4] |

| Michaelis Constant (K |

Baseline (1x) | 4.6x increase [4] |

| Effect of Glycine/Basic Amino Acids | Significant rate enhancement for E. coli [4] | Significantly reduced effect [4] |

| Diffusion Mode | Not applicable | External diffusion limitations observed at low cell densities [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Lysis Optimization

Protocol 1: Augmented Lysozyme Lysis for Gram-Negative Bacteria This protocol uses glycine to potentiate lysozyme activity against Gram-negative cells [4].

- Reagents: Lysozyme, Glycine, Tris-HCl Buffer (pH 7.0-8.0), bacterial cell suspension.

- Procedure:

- Suspend the Gram-negative cell pellet (e.g., E. coli) in Tris-HCl buffer.

- Add glycine to the suspension at a final concentration of 100-150mM.

- Add lysozyme to a final concentration of 100 µg/mL.

- Incubate the mixture at 37°C with gentle agitation for 30-60 minutes.

- Monitor lysis by measuring the decrease in optical density at 600nm (OD600).

Protocol 2: Sequential Disruption for Stubborn Gram-Positive Bacteria This multi-step protocol mechanically and enzymatically disrupts the robust Gram-positive envelope.

- Reagents: Lysozyme, Lysostaphin (for staphylococci), Mutanolysin (for streptococci), TE Buffer, Sucrose, EDTA.

- Procedure:

- Harvest Gram-positive cells and wash with TE buffer.

- For initial weakening, resuspend cells in a hypertonic buffer containing sucrose (e.g., 0.5M) and incubate with lysozyme and species-specific enzymes (e.g., Lysostaphin) at 37°C.

- Follow with osmotic shock by rapidly diluting the protoplasts into a hypotonic buffer or distilled water.

- For complete disruption, combine enzymatic pre-treatment with mechanical methods like bead-beating or sonication on ice.

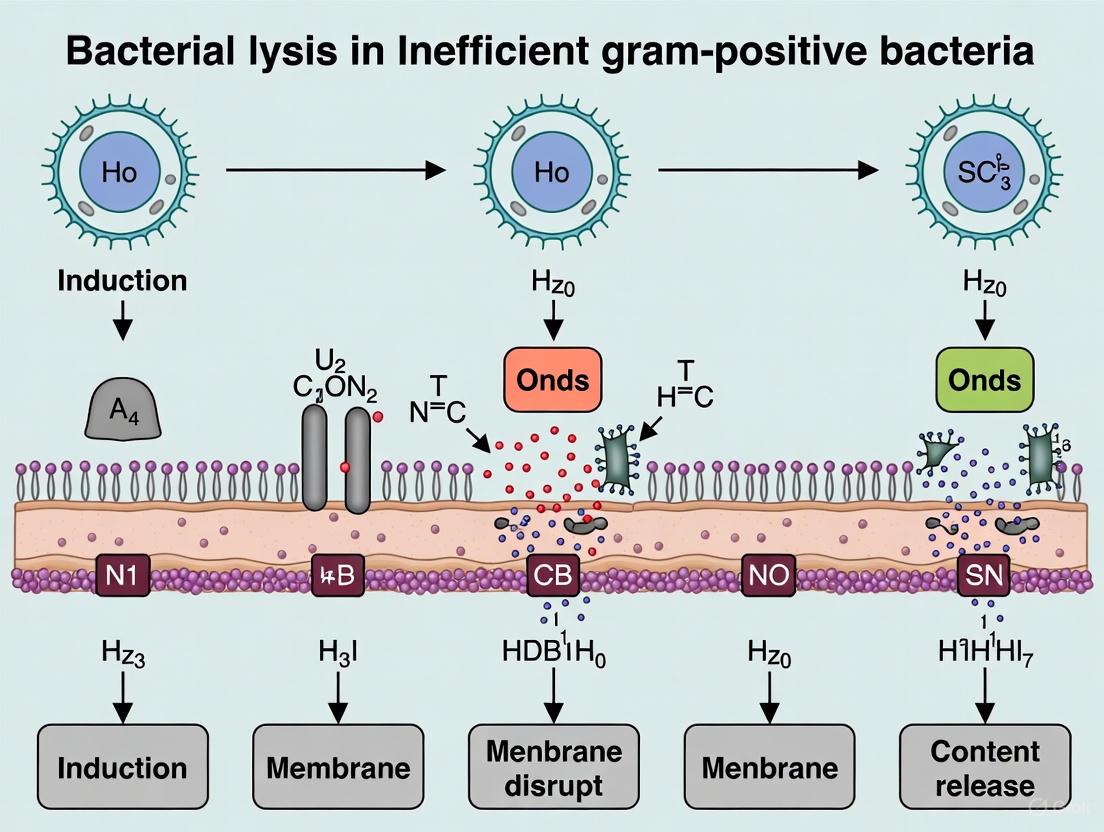

Structural and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Bacterial Cell Envelope Structures

Experimental Lysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Bacterial Cell Envelope Lysis Research

| Research Reagent | Function & Mechanism | Specific Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Lysozyme | Hydrolyzes β-(1,4) linkages between N-acetylmuramic acid and N-acetylglucosamine in peptidoglycan [4]. | Core enzyme for digesting the peptidoglycan layer; effectiveness is enhanced by pre-treatments, especially for Gram-negatives [4]. |

| Glycine | A basic amino acid that incorporates into peptidoglycan during synthesis, disrupting cross-linking and integrity. | Significantly increases the lysis rate of Gram-negative bacteria like E. coli when used with soluble lysozyme [4]. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelates divalent cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺), destabilizing the LPS layer of the Gram-negative outer membrane [1]. | Used as a pre-treatment to permeabilize the outer membrane, allowing lysozyme access to the underlying peptidoglycan. |

| Lysostaphin | A glycyl-glycine endopeptidase that cleaves the pentaglycine cross-bridges in the peptidoglycan of Staphylococcus species. | Critical for the efficient lysis of Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus; often used in combination with lysozyme. |

| Mutanolysin | A muramidase that lyses the cell walls of a broad range of Gram-positive bacteria by hydrolyzing peptidoglycan. | Highly effective for lysing difficult Gram-positive bacteria like streptococci and lactobacilli. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Provides a stable pH environment (typically 7.0-8.5) optimal for the activity of many lytic enzymes. | Standard buffering system for most lysis reactions; ensures enzyme stability and activity. |

Fundamental Concepts: Peptidoglycan Structure and Gram Classification

What is the basic chemical structure of the peptidoglycan monomer?

The peptidoglycan (PG) monomer, or muropeptide, is a disaccharide-pentapeptide complex that serves as the fundamental building block of the bacterial cell wall [5] [6]. Each monomer consists of:

- A disaccharide unit: Formed by alternating sugars, N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc), linked by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds [5] [7] [6].

- A pentapeptide stem: Attached to the D-lactyl group of each MurNAc residue via an amide bond [5] [7]. In Escherichia coli, a canonical Gram-negative organism, the peptide sequence is L-Ala-γ-D-Glu-meso-DAP-D-Ala-D-Ala, where meso-DAP is meso-diaminopimelic acid [5] [8]. In most Gram-positive bacteria, the third residue is typically L-Lysine instead of meso-DAP [9] [7].

These monomers are polymerized into a massive, mesh-like sacculus that surrounds the cytoplasmic membrane, providing structural integrity and counteracting internal osmotic pressure [5] [6] [8].

How does peptidoglycan architecture differ between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria?

The key distinction lies in the thickness and complexity of the peptidoglycan layers, which directly influences the Gram-staining reaction [10] [7].

Table: Key Architectural Differences in Peptidoglycan

| Feature | Gram-Positive Bacteria | Gram-Negative Bacteria |

|---|---|---|

| Peptidoglycan Thickness | Thick, multilayered (30-100 nm) [7] [8] | Thin, predominantly monolayered (2-7 nm) [5] [8] |

| Structural Complexity | Multiple layers of peptidoglycan sheets [10] | Single, mesh-like network [5] |

| Additional Components | Often contains covalently bound anionic polymers like wall teichoic acids [5] [7] | Peptidoglycan is covalently tethered to the outer membrane via Braun's lipoprotein (Lpp) [5] |

| Overall Dry Weight | Peptidoglycan can constitute ~20% of cell wall dry weight [11] | Peptidoglycan constitutes ~10% of cell wall dry weight [11] |

The thick, multi-layered PG of Gram-positive bacteria retains the crystal violet-iodine complex during decolorization, resulting in a purple stain. The thin PG of Gram-negative bacteria, located in the periplasm, does not retain the complex and instead takes up the counterstain (safranin), appearing pink [7].

Experimental Analysis & Methodologies

What are the established protocols for analyzing peptidoglycan cross-linking?

Analyzing cross-linking is crucial for understanding cell wall mechanics and resistance to lysis. The following workflow outlines a standard approach for PG purification and analysis, which can be adapted for studying inefficient lysis in Gram-positive bacteria.

Detailed Methodology:

- PG Sacculus Purification: Grow bacterial culture to the desired phase. Harvest cells by centrifugation. To inactivate autolytic enzymes, resuspend the cell pellet in boiling 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and incubate for 30 minutes [12]. Wash the resulting insoluble sacculi repeatedly with warm buffer and water to remove SDS, proteins, and other non-PG components.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Digest the purified sacculi with a muramidase such as Cellosyl (lysozyme can also be used, but it hydrolyzes bonds, unlike the lytic transglycosylase activity of Cellosyl which produces anhydromuropeptides) [12]. This enzyme cleaves the β-1,4-glycosidic bonds between GlcNAc and MurNAc, breaking the sacculus into its constituent muropeptides.

- Sample Preparation for HPLC: Reduce the muropeptides with sodium borohydride to convert the MurNAc residues from their ring form to a linear one, improving chromatographic resolution.

- Separation and Analysis: Separate the reduced muropeptides by Reverse-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) with a C18 column, typically using a phosphate buffer and methanol gradient. Detect the eluting muropeptides by their absorbance at 205-210 nm.

- Identification and Quantification: Identify individual muropeptide peaks by Mass Spectrometry (MS) [12]. The cross-linking percentage is calculated as the ratio of the total area of cross-linked muropeptides to the total area of all muropeptides, multiplied by 100.

How can synthetic peptidoglycan probes be used to study cross-linking in live bacteria?

Recent advances utilize synthetic, fluorescently-labeled PG stem peptide analogs to dissect transpeptidation kinetics and substrate specificity directly in live bacterial cells [9]. These probes are designed to mimic either the acyl-donor or acyl-acceptor strand in the cross-linking reaction catalyzed by transpeptidases.

Table: Synthetic Peptidoglycan Probes for Live-Cell Analysis

| Probe Type | Design Strategy | Primary Application | Key Experimental Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acyl-Donor Probe [9] | Mimics the stem peptide as a tetrapeptide; the nucleophilic site on the acyl-acceptor strand is blocked. | Tracks incorporation into PG scaffold exclusively as a donor strand for transpeptidases. | Reveals parameters for cross-linking based on the acyl-donor strand. |

| Acyl-Acceptor Probe [9] | Installs the cross-bridging amino acids but removes the terminal D-Ala-D-Ala motif recognized by the acyl-donor site. | Tracks incorporation exclusively as an acyl-acceptor strand. | Demonstrates that amidation of the crossbridge (e.g., d-iAsp to d-iAsn) can significantly increase crosslinking levels. |

Protocol for Probe Utilization:

- Synthesis: Synthesize tripeptide or tetrapeptide probes using solid-phase peptide chemistry, incorporating a fluorescent tag (e.g., carboxy-fluorescein, FAM) at the N-terminus [9].

- Live-Cell Incubation: Treat live bacterial cells (e.g., Enterococcus faecium) with the individual probes and incubate overnight to allow for incorporation into the growing PG scaffold.

- Detection and Analysis: Measure cellular fluorescence levels using a microplate reader or analyze by confocal microscopy to visualize probe localization within the PG [9]. Quantification of fluorescence provides a direct measure of cross-linking efficiency under different conditions or in mutant strains.

Troubleshooting Inefficient Lysis in Gram-Positive Bacteria

Why is lysing Gram-positive bacteria particularly challenging?

Inefficient lysis of Gram-positive bacteria is a common hurdle in research, primarily due to their robust cell wall architecture. The challenges stem from several structural factors:

- Extreme Peptidoglycan Thickness: The 30-100 nm thick, multilayered PG network presents a formidable physical barrier to lytic enzymes, unlike the thin, single-layer PG of Gram-negative bacteria [10] [7] [8].

- High Cross-Linking Density: The dense mesh of cross-linked glycan strands significantly increases the mechanical strength of the wall, requiring more extensive bond cleavage for lysis to occur.

- Chemical Modifications: Structural variations in the PG stem peptide, such as the amidation of D-isoGlutamate (D-iGlu) to D-isoGlutamine (D-iGln), have been shown to critically enhance PG cross-linking levels and stability, further increasing resistance to enzymatic degradation [9]. In Streptococcus pneumoniae, this amidation is essential [7].

- Regulation of Autolysins: The activity of the bacterium's own PG-degrading enzymes (autolysins) is tightly controlled. Recent research shows that LD-crosslinks can act as inhibitors of lytic transglycosylases (LTs), a major class of autolysins [12]. An increase in LD-crosslinking can therefore suppress autolytic activity, making exogenous lysis more difficult.

What strategies can enhance lysis efficiency for Gram-positive cells?

To overcome the robust cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria, a combination of mechanical, chemical, and enzymatic methods is often required.

Table: Reagents for Enhanced Lysis of Gram-Positive Bacteria

| Reagent / Method | Category | Mode of Action | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysozyme [6] | Enzymatic | Hydrolyzes β-1,4-glycosidic bonds between GlcNAc and MurNAc in peptidoglycan. | Often insufficient alone; requires combination with other agents. |

| Lysostaphin [11] | Enzymatic | Glycyl-glycine endopeptidase that specifically cleaves pentaglycine cross-bridges in Staphylococcus spp. PG. | Highly specific; check target organism compatibility. |

| Mutanolysin | Enzymatic | A muramidase derived from Streptomyces globisporus, effective against a broad range of Gram-positive bacteria. | |

| Penicillins [11] | Antibiotic (Chemical) | Inhibit transpeptidases (PBPs), preventing new cross-link formation. Weakens the wall during active growth. | Use at sub-MIC levels to weaken the wall without completely inhibiting growth. |

| Glycine | Chemical (Amino Acid) | Incorporated into PG in place of L-Alanine, disrupting proper cross-linking and leading to a weakened cell wall. | |

| Bead Beating | Mechanical | Uses high-speed shaking with small beads to physically shear cells. | Highly effective but can generate heat and damage cellular components. |

| Sonication | Mechanical | Uses high-frequency sound waves to disrupt cell walls. | Effective for small volumes; can also generate heat. |

Recommended Workflow for Troubleshooting:

- Pre-treatment: Grow bacteria in media supplemented with sub-inhibitory concentrations of penicillin or 1-2% glycine to weaken the PG during growth.

- Enzymatic Lysis: Harvest cells and resuspend in an isotonic buffer. Use a cocktail of lytic enzymes (e.g., lysozyme with mutanolysin) rather than a single enzyme. Increase enzyme concentration and extend incubation time at 37°C.

- Chemical Permeabilization: Include a detergent like Triton X-100 or SDS in the lysis buffer to help solubilize membranes after the PG barrier is compromised.

- Mechanical Disruption: If enzymatic lysis remains inefficient, employ mechanical methods such as bead beating or sonication. For bead beating, optimize the duration and speed to balance lysis efficiency against macromolecular degradation.

Advanced Research Visualizations

How do different cross-linking modes regulate autolysin activity?

The type of cross-link in the peptidoglycan sacculus not only provides structural integrity but also actively regulates the enzymes that remodel it. This regulatory mechanism is key to understanding PG homeostasis and lysis efficiency.

As illustrated, LD-crosslinks, formed by L,D-transpeptidases (LDTs), act as structural inhibitors of lytic transglycosylases (LTs), a major class of autolysins [12]. Conditions that promote LD-crosslinking (e.g., minimal media) result in reduced LT activity, lower release of PG fragments (anhydromuropeptides), and enhanced resistance to lysis. Conversely, when DD-crosslinks (formed by PBPs) dominate or when LDTs are inhibited (e.g., by copper), LT activity is increased, leading to higher PG degradation and susceptibility to lysis [12]. This explains how modulating the cross-linking mode can be a bacterial strategy to enhance resilience.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Peptidoglycan Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Cellosyl (Muramidase) | Purified lytic transglycosylase used for digesting purified PG sacculi into muropeptides for HPLC analysis [12]. |

| Lysozyme | N-acetylmuramidase that hydrolyzes PG glycosidic bonds; used for cell lysis and PG digestion [5] [6]. |

| Synthetic PG Probes (e.g., TriQN) | Fluorescently-labeled stem peptide analogs (e.g., acyl-acceptor probes) used to interrogate cross-linking parameters in live bacterial cells [9]. |

| Penicillin G | Beta-lactam antibiotic that inhibits D,D-transpeptidases (PBPs); used to study cell wall synthesis and to weaken the PG layer [5] [11]. |

| CuSO₄ (Copper Sulfate) | Specific inhibitor of L,D-transpeptidases (LDTs); used to manipulate LD-crosslinking levels in vivo to study its physiological role [12]. |

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBH₄) | Reducing agent used to convert the ring form of MurNAc in muropeptides to a linear form, improving HPLC chromatographic resolution. |

| Sub-MIC Glycine | Amino acid that disrupts PG cross-linking when incorporated; used as a pretreatment to sensitize bacterial cells to lysis. |

The Role of Teichoic Acids and Lipoteichoic Acids in Structural Integrity

FAQs: Teichoic Acids and Bacterial Lysis Challenges

1. Why is bacterial lysis particularly inefficient for Gram-positive bacteria, and what role do Teichoic Acids play in this? The rigid, multi-layered cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria presents a significant physical barrier. This wall is composed of a thick peptidoglycan layer that is densely functionalized with Wall Teichoic Acids (WTAs), which can account for up to 60% of the cell wall's dry mass [13] [14]. The combination of peptidoglycan and anionic glycopolymers like WTAs and Lipoteichoic Acids (LTAs) makes the cell wall highly resistant to standard mechanical and enzymatic lysis methods used in the lab [15].

2. What are the fundamental structural differences between Wall Teichoic Acid (WTA) and Lipoteichoic Acid (LTA)? The key difference lies in their attachment points within the cell envelope, as illustrated in Table 1. WTAs are covalently linked to the peptidoglycan layer, while LTAs are anchored into the cytoplasmic membrane via a glycolipid anchor [13] [16] [14]. This distinction defines their location and influences their specific functions in maintaining structural integrity.

Table 1: Core Structural and Functional Differences between WTA and LTA

| Feature | Wall Teichoic Acid (WTA) | Lipoteichoic Acid (LTA) |

|---|---|---|

| Anchor Point | Covalently bound to peptidoglycan's N-acetylmuramic acid [13] | Anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane via a glycolipid (e.g., diacylglycerol) [14] |

| Primary Structure | Diverse; poly-glycerol phosphate (GroP) or poly-ribitol phosphate (RboP) repeats [13] | Typically, a poly-glycerol phosphate (GroP) backbone [14] |

| Overall Polarity | Hydrophilic [14] | Amphipathic (has both hydrophilic and hydrophobic parts) [14] |

| Key Biosynthetic Enzymes | TagO, TarA, TarB, TarF (for GroP) [13] [16] | Primarily uses a different set of enzymes from the LTA synthesis pathway [16] |

3. How do tailoring modifications on Teichoic Acids, like D-alanylation, affect bacterial physiology and resistance to host defenses? Teichoic acids are often chemically modified, which fine-tunes their physical and chemical properties. A key modification is the esterification of D-alanine to the polyol repeats [13] [14]. This introduces positive charges, creating a zwitterionic polymer that reduces the overall negative charge of the cell wall. This modulation of charge is critical for:

- Cation Homeostasis: Regulating the binding of divalent cations like Mg²⁺ [14].

- Resistance to Antimicrobials: Helping the bacterium resist cationic antimicrobial peptides from the host immune system [13] [14].

- Control of Autolysins: Regulating the activity of autolytic cell wall enzymes to prevent self-digestion [16].

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Lysis Inefficiency

Problem: Low yield and poor quality of nucleic acids or proteins from Gram-positive bacteria.

Solution: Implement an optimized mechanical homogenization protocol. The standard enzymatic or chemical lysis methods are often insufficient for robust Gram-positive species. An optimized bead-beating method has been shown to significantly improve RNA yields by physically disrupting the resilient cell wall [15].

Table 2: Optimized Bead-Beating Protocol for Gram-Positive Bacterial Lysis

| Step | Parameter | Details & Specification |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cell Homogenization | Method | Glass Bead Beating (superior to zirconium beads or high-pressure lysis in tested methods) [15] |

| Cycles | Three (3) full cycles [15] | |

| 2. Performance Outcome | Yield Improvement | >15-fold increase for Lactococcus lactis; >6-fold increase for Enterococcus faecium [15] |

| RNA Integrity | Maintains RNA Integrity Number (RIN) >7.0 [15] | |

| 3. Important Note | Species Variability | Method had minimal added benefit for Staphylococcus aureus, which lysed efficiently without homogenization [15] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying Teichoic Acid Biosynthesis and Function

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) | Essential nucleotide sugar precursor for the initiation of WTA linkage unit synthesis by TagO [13]. |

| UDP-N-acetylmannosamine (UDP-ManNAc) | Nucleotide sugar donor used by TarA to form the conserved disaccharide linkage unit of WTA [13]. |

| CDP-glycerol | Activated glycerol phosphate donor for the addition of the first glycerol phosphate (by TagB) and for the polymerization of the poly(GroP) chain (by TagF) [13]. |

| Undecaprenyl Phosphate (C55-P) | Lipid carrier molecule embedded in the cytoplasmic membrane; serves as the anchor for the synthesis of both WTA and peptidoglycan precursors [13] [16]. |

| Anti-Lipoteichoic Acid Antibodies | Used to detect, localize, and quantify LTA in cell fractions or on the bacterial surface; crucial for studying LTA's role in host-pathogen interactions [17] [18]. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: WTA Biosynthesis and Lysis Challenge Workflow

Diagram 2: Teichoic Acid Structural Localization in Cell Envelope

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my purified recombinant autolysin showing unexpectedly low lytic activity against live S. aureus cells? This is a common issue. Native autolysins often have suboptimal cell wall binding domains (CWBDs) that target them to specific locations like the septal cross-wall, limiting their effectiveness when applied exogenously [19]. Their potency can be 10 to 1000 times lower than bacteriolytic enzymes like lysostaphin [19]. Solution: Consider replacing the native CWBD with a high-affinity domain, such as the SH3b domain from lysostaphin, which binds ubiquitously to the pentaglycine crosslinks in the S. aureus cell wall. This chimeragenesis approach has been shown to enhance lytic activity by up to 140-fold [19].

Q2: How can I enhance the activity of lysozyme against Gram-negative bacteria? The activity of native lysozyme against Gram-negative bacteria can be significantly increased by the addition of certain amino acids. Glycine and basic amino acids (e.g., histidine, lysine, arginine) have been shown to significantly increase the lysis rate of E. coli [4]. Furthermore, acidic amino acids (glutamate, aspartate) can enhance the lysis of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [4].

Q3: My bacterial culture is not lysing efficiently with the expressed lysin. Could the bacteria have an active defense system? Yes, bacteria possess stress-sensing systems that protect against murein hydrolase activity. For example, in Streptococcus pneumoniae, the LiaFSR system is activated by damage from murein hydrolases like CbpD, LytA, and LytC [20]. This system upregulates genes that provide a layer of protection against fratricide-induced self-lysis. Ensuring your lysin is potent and adequately delivered is key to overcoming these defenses.

Q4: What is a key difference between phage endolysins and bacterial autolysins? The primary difference often lies in their cell wall binding domains (CWBDs) and resulting targeting efficiency. Phage endolysins like lysostaphin possess CWBDs that bind ubiquitously across the cell wall, leading to rapid lysis [19]. In contrast, many autolysins have CWBDs that target them to specific sites like the division septum, which is crucial for their physiological role but results in poor performance as exogenous lytic agents [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inefficient Lysis of Gram-Positive Bacteria by Autolysins

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Suboptimal Cell Wall Targeting.

- Solution: Engineer chimeric lysins. Fuse the catalytic domain of your autolysin to a high-performance CWBD, such as the SH3b domain from lysostaphin [19].

- Protocol: Molecular Engineering of a Chimeric Lysin

- Amplify Domains: PCR-amplify the DNA sequence of your autolysin's catalytic domain and the lysostaphin SH3b CWBD with compatible overhangs.

- Ligate: Use Gibson Assembly or similar methods to ligate the catalytic domain upstream of the CWBD in an expression vector.

- Express and Purify: Transform the plasmid into an E. coli expression host. Induce protein expression and purify the chimeric protein using a suitable tag (e.g., His-tag).

- Assay Activity: Compare the lytic activity of the chimera against the native autolysin using a turbidity reduction assay with live target bacteria [19].

Cause: Suboptimal Reaction Conditions.

- Solution: Characterize the environmental optima of your enzyme. Note that upon covalent immobilization, the pH optimum of lysozyme activity broadens for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [4]. The Michaelis constant (Km) can also change significantly after immobilization, indicating altered substrate affinity [4].

- Protocol: Determining pH Optimum

- Prepare buffers covering a pH range (e.g., pH 5.0 to 8.0).

- Add a fixed amount of enzyme to a bacterial suspension in each buffer.

- Measure the decrease in optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) over time.

- Plot the maximum lysis rate against pH to identify the optimum.

Problem: Low Activity of Immobilized Lysin Preparations

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Mass Transfer Limitation (Diffusion Barrier).

- Solution: Be aware that at bacterial concentrations below a certain threshold (e.g., 4 × 10⁸ CFU·mL⁻¹), the kinetics of immobilized lysozyme can be governed by external diffusion, which may limit its apparent activity [4]. Agitation can help mitigate this. Furthermore, the effects of enhancers like amino acids are significantly reduced with immobilized enzymes compared to their soluble counterparts [4].

Quantitative Data on Lysozyme Activity Enhancement

Table 1: Effect of Amino Acids on the Lysis Rate of Bacteria by Soluble Lysozyme [4]

| Amino Acid Added | Effect on Gram-negative E. coli | Effect on Gram-positive M. luteus |

|---|---|---|

| Glycine | Significant increase | No substantial effect |

| Basic Amino Acids (Histidine, Lysine, Arginine) | Significant increase | No substantial effect |

| Acidic Amino Acids (Glutamate, Aspartate) | Significant increase | Significant increase |

Table 2: Changes in Enzymatic Properties of Lysozyme upon Covalent Immobilization [4]

| Property | Change for E. coli Lysis | Change for M. luteus Lysis |

|---|---|---|

| pH Optimum | Broadened | Broadened |

| Michaelis Constant (Kₘ) | Increased 1.5-fold | Increased 4.6-fold |

Visualizing Key Concepts and Protocols

Bacterial Stress Response to Murein Hydrolase Attack

The following diagram illustrates the LiaFSR stress-sensing system in Streptococcus pneumoniae, which is activated by murein hydrolase activity [20].

Workflow for Enhancing Autolysin Activity via Chimeragenesis

This flowchart outlines the process of creating and testing a chimeric lysin with enhanced activity [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Murein Hydrolase Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Lysostaphin SH3b Domain | A high-affinity cell wall binding domain (CWBD) used in chimeragenesis to drastically improve the targeting and lytic activity of autolysins against S. aureus [19]. |

| Charged Amino Acids (Basic & Acidic) | Used as activity enhancers in lysis assays, particularly to boost the effectiveness of lysozyme against Gram-negative bacteria [4]. |

| Covalent Immobilization Supports (e.g., activated beads, resins) | Used to create immobilized enzyme preparations for developing antimicrobial surfaces or reusable enzymatic treatments. Alters enzyme properties like pH profile and Kₘ [4]. |

| Turbidity Reduction Assay Components (Microplate reader, culture broth, buffer) | The standard method for quantifying the lytic activity of enzymes by measuring the decrease in optical density (OD₆₀₀) of a bacterial suspension over time [19]. |

| Bioinformatic Tools (SMART, NCBI CDD) | Used to identify and annotate catalytic and cell wall binding domains within autolysin sequences from genomic data [21]. |

For researchers battling inefficient bacterial lysis, the formidable architecture of the Gram-positive cell wall represents a significant technical hurdle. Unlike Gram-negative bacteria with their thin peptidoglycan layer, Gram-positive species possess a thick, multi-layered cell wall that acts as a robust physical barrier, complicating DNA extraction, protein purification, and other essential laboratory procedures [22] [23]. This technical support article dissects the structural foundations of this inherent resistance and provides evidence-based troubleshooting guidance to optimize your lysis protocols. The core challenge lies in the peptidoglycan scaffold—a single, massive macromolecule that surrounds the cell, acting as a primary constraint against internal turgor pressure [22]. Recent structural insights reveal that the mature surface of bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus is a disordered gel of peptidoglycan characterized by large pores, while the inner, more nascent surface is significantly denser, influencing how lytic agents penetrate and degrade the wall [22]. Understanding this architecture is paramount for developing effective lysis strategies in drug development and basic research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is lysing Gram-positive bacteria particularly challenging compared to Gram-negative species?

The challenge stems from fundamental differences in cell wall architecture and composition. Gram-positive bacteria have a thick (20-40 nm), multi-layered peptidoglycan shell that constitutes up to 90% of the cell wall material, extensively cross-linked by peptide bridges [23]. This creates a dense, three-dimensional fabric that is difficult for enzymes and chemicals to penetrate. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have a much thinner (approximately 10 nm) peptidoglycan layer (only two to five layers thick) sandwiched between an inner and outer phospholipid membrane, making them more susceptible to many lysis methods [23].

Q2: What is the role of autolysins and murein hydrolases in bacterial lysis?

Murein hydrolases are a diverse family of enzymes produced by bacteria themselves that specifically cleave structural bonds within the peptidoglycan [23]. Those that lead to the destruction of the cell wall and subsequent cell lysis are termed autolysins. They play critical roles in normal bacterial physiology, including daughter cell separation, cell wall growth, and peptidoglycan turnover [23]. In a laboratory context, we can exploit these enzymes or their bacteriophage-derived equivalents (lysins) to disrupt the cell wall. Their activity is highly specific, targeting various structural components such as the glycan backbone or the peptide cross-links [23].

Q3: How does the peptidoglycan structure differ between species like Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus, and why does this matter for lysis?

While both are Gram-positive, their peptidoglycan architecture exhibits distinct organizational patterns that influence lysis efficiency. In B. subtilis, the inner peptidoglycan surface of the cylinder has a dense circumferential orientation. In contrast, S. aureus peptidoglycan is dense but randomly oriented [22]. This architectural difference means that enzymes with specific cleavage activities may demonstrate varying efficacy against different bacterial species. Furthermore, S. aureus peptidoglycan is notably more extensively cross-linked, with greater than 90% of the stem peptides linked together, forming a denser network compared to other species [23].

Q4: Can tuning the binding affinity of a lysin improve its efficacy?

Yes, recent research indicates that binding affinity is a dominant driver of lysin efficacy, sometimes more so than inherent catalytic power. For example, a systematic analysis of lysostaphin revealed that a single point mutation in its cell wall-binding domain (CBD) that reduced binding affinity paradoxically enhanced its processivity and lysis kinetics [24]. The engineered variant (F12) with a 4-fold reduction in binding affinity manifested 60-70% faster lysis kinetics and significantly improved in vivo efficacy against MRSA, despite having a higher MIC in vitro [24]. This suggests that finely tuned affinity allows for more efficient turnover and dispersal of the enzyme across the cell surface.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Lysis Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Cell Lysis [25] | Cell density is too high. | Reduce the culture volume to ensure effective lysis. |

| Insufficient alkaline lysis or enzymatic treatment. | Check lysis solutions for precipitates; ensure correct concentration and activity of enzymatic supplements (e.g., lysozyme, lysostaphin) [26]. | |

| Genomic DNA Contamination [25] | Vigorous vortexing during lysis. | Avoid vortexing too vigorously after lysis and neutralization steps. |

| Overloaded reaction or column. | Reduce the bacterial culture volume to not overload the system. | |

| Low or No Yield [25] | Plasmid did not propagate. | Use freshly streaked bacterial cells for inoculation. |

| Loss of selective pressure. | Use an appropriate concentration of antibiotics during cultivation to prevent overgrowth of non-transformed cells. | |

| Reduced effectiveness of lytic enzymes. | Store enzymes and kit components under recommended conditions; use fresh aliquots. | |

| Poor Performance in Downstream Processes [25] | Additional plasmid forms present. | Avoid denaturation of plasmid DNA by not prolonging cell lysis beyond the recommended time. |

| Ethanol carryover in the resuspended DNA. | Increase the drying time of the pellet after washing to ensure all ethanol has evaporated. |

Quantitative Data: Comparing Lysis Efficiencies

The following tables consolidate quantitative data on the performance of various lysis methods and architectural features to aid in experimental planning and analysis.

Table 1: Lysis Efficiency Across Different Methodologies

| Lysis Method / Agent | Target Bacteria | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Lysis (ECL) [27] | Gram-positive (E. durans, B. subtilis) & Gram-negative | Lysis Efficiency (via cell counting) | Up to ~99% (Gram-neg) & ~80% (Gram-pos) at ~5V, 1 min | [27] |

| Porous Polymeric Monolith (PPM) Biochip [28] | Gram-positive & Gram-negative | Lysis time per cycle (for 10^5 CFU/mL) | ~35 min (including regeneration) | [28] |

| Engineered Lysostaphin (F12 variant) [24] | S. aureus (MRSA) | Lysis Kinetics (TOD₅₀) | 60-70% faster than wild-type | [24] |

| Homogeneous Chemical Lysis [27] | Gram-positive & Gram-negative | DNA Extraction Efficiency | Lower than ECL and commercial kits | [27] |

Table 2: Architectural Features of Gram-Positive Bacterial Cell Walls

| Architectural Feature | Measurement / Characteristic | Experimental Method | Significance for Lysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptidoglycan Thickness [23] | 20 - 40 nm | Electron Microscopy | Defines the physical barrier thickness that lytic agents must penetrate. |

| Peptidoglycan Cross-linking (S. aureus) [23] | >90% of stem peptides | Biochemical Analysis | Determines the density and mechanical strength of the cell wall network. |

| Surface Pore Diameter (S. aureus) [22] | Up to 60 nm | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Impacts initial access and penetration of lytic enzymes into the wall structure. |

| Surface Pore Depth (S. aureus) [22] | Up to 23 nm | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | - |

| Inner Wall Glycan Strand Spacing [22] | Typically <7 nm | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | A denser inner layer may require more processive or targeted enzymatic activity for complete disruption. |

Experimental Protocols for Efficient Lysis

Protocol: Electrochemical Lysis (ECL) for DNA Extraction

This protocol is adapted from a method demonstrated to efficiently lyse both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria for DNA extraction from environmental samples [27].

Principle: The application of a low voltage (~5 V) across electrodes in a bacterial suspension leads to the local generation of hydroxide ions at the cathode surface. The resulting high pH disrupts microbial cell membranes by breaking fatty acid-glycerol ester bonds in phospholipids [27].

Materials:

- ECL device (with IrO₂/Ti anode, Ti cathode, and Nafion 117 cation exchange membrane)

- Potentiostat

- Centrifuge

- Sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄)

- Bacterial suspension washed and resuspended in 50 mM Na₂SO₄

Procedure:

- Preparation: Inject 50 mM Na₂SO₄ into the anodic chamber (1.6 mL) of the ECL device. Inject the bacterial suspension (~10⁸ cells/mL in 50 mM Na₂SO₄) into the cathodic chamber (0.8 mL).

- Lysis: Apply a constant direct current of 40 mA (16 mA/cm²) for 1 minute. This is the identified optimal duration for effective lysis with minimal processing time [27].

- Collection: Collect the cathodic effluent, which now contains the lysed cellular material and released DNA.

- Analysis: The effluent can be used directly for downstream PCR applications. The device should be washed three times with DI water between experimental runs [27].

Protocol: Enzymatic Lysis Using Specific Glycosidases and Peptidases

This protocol outlines the use of enzyme cocktails to target specific bonds in the Gram-positive cell wall.

Principle: Different enzymes hydrolyze specific bonds within the peptidoglycan matrix. Using enzymes with complementary activities can lead to synergistic and more efficient lysis [29] [23].

Materials:

- Labiase (from Streptomyces fulvissimus): Targets many Gram-positive bacteria like lactobacilli; has N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase and lysozyme activity. Optimal activity at pH ~4 [29].

- Lysostaphin: A zinc endopeptidase that specifically cleaves the pentaglycine cross-bridges in the peptidoglycan of Staphylococcus species. Optimal activity at pH ~7.5 [29].

- Lysozyme: Hydrolyses the β(1-4) linkage between N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid in the peptidoglycan backbone. Active in a broad pH range (6.0-9.0) [29].

- Achromopeptidase: A lysyl endopeptidase useful for lysing Gram-positive bacteria resistant to lysozyme. Optimal activity at pH ~8.5-9.0 [29].

- Mutanolysin: An N-acetylmuramidase that cleaves the peptidoglycan polymer gently, suitable for isolating labile biomolecules. Effective against Listeria and other Gram-positives [29].

- Appropriate resuspension and reaction buffers.

Procedure:

- Harvesting: Pellet bacterial cells by centrifugation (e.g., 5,000 rpm) and discard the supernatant.

- Resuspension: Resuspend the cell pellet thoroughly in an appropriate buffer matched to the optimal pH of the chosen enzyme(s). Incomplete resuspension is a common cause of inefficient lysis [25].

- Enzymatic Treatment: Add the selected enzyme(s). For example, to lyse S. aureus, use 25 µL of a 500,000 units/mL lysostaphin solution per 1 mL of cell suspension resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) with 0.1 M NaCl and 1 mM EDTA [29].

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at 37°C for 30-60 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Verification: Check for lysis by a decrease in the optical density of the suspension. Proceed to nucleic acid or protein purification.

Visualizing Key Concepts

Gram-Positive Cell Wall Architecture and Lytic Targets

The following diagram illustrates the complex, multi-layered structure of the Gram-positive cell wall and the primary cleavage sites for different classes of lytic enzymes.

Diagram Title: Gram-Positive Cell Wall and Enzyme Targets

The Affinity-Efficiency Relationship in Engineered Lysins

This diagram outlines the logical relationship discovered between cell wall-binding domain (CBD) affinity, enzyme processivity, and overall lysis efficacy, which can guide protein engineering efforts.

Diagram Title: How Tuned Affinity Enhances Lysin Performance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Enzymatic Reagents for Gram-Positive Bacterial Lysis

| Reagent | Source | Primary Mechanism of Action | Key Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysostaphin [29] [24] | Staphylococcus simulans | Zinc endopeptidase that cleaves pentaglycine cross-bridges in Staphylococcus peptidoglycan. | Highly specific for Staphylococcus species. Key tool for anti-MRSA research. Efficacy can be tuned via CBD affinity [24]. |

| Lysozyme [29] | Chicken Egg White | Hydrolyses β(1-4) linkages between N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid in the glycan backbone. | Broad-spectrum activity against many Gram-positive bacteria. Less effective on its own against highly cross-linked species. |

| Mutanolysin [29] | Streptomyces globisporus | N-acetylmuramidase that cleaves the peptidoglycan backbone. Similar mechanism to lysozyme but with different specificity. | Gentler lysis; suitable for isolating labile bacterial biomolecules and RNA. Effective against Listeria, lactobacilli. |

| Labiase [29] | Streptomyces fulvissimus | Exhibits N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase and lysozyme activity. | Effective for lysing many Gram-positive bacteria, including lactobacilli, aerococci, and streptococci. Optimal at pH ~4. |

| Achromopeptidase [29] | Bacterial Source | Lysyl endopeptidase (endopeptidase that cleaves at lysine residues). | Used for lysing Gram-positive bacteria that are resistant to lysozyme. Optimal at alkaline pH (8.5-9.0). |

Breaking Down the Wall: A Toolkit of Lysis Methods for Gram-Positive Bacteria

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: My protocol calls for lysozyme, but I'm working with a Staphylococcus aureus strain. The lysis is inefficient. What is the issue?

Lysozyme is most effective against Gram-positive bacteria with peptidoglycan rich in β(1→4) linkages between N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) and N-acetylglucosamine (NAG). However, some Gram-positive bacteria like S. aureus have peptidoglycan modified with O-acetyl groups or complex cross-linking that makes them resistant to lysozyme [30]. For S. aureus, the specialist enzyme lysostaphin is recommended. It is an endopeptidase that specifically cleaves the pentaglycine bridges unique to staphylococcal peptidoglycan [31] [32].

Q2: I am trying to extract DNA from Lactobacillus. Which enzyme should I use for effective lysis?

For lactic acid bacteria like Lactobacillus, lysozyme is often insufficient. Labiase is a highly effective enzyme for this application. It possesses β-N-acetyl-D-glucosamidase and muramidase activities, giving it broad-spectrum bacteriolytic activity against many Gram-positive bacteria, including Lactobacillus and Streptococcus [33] [32].

Q3: My lab uses mutanolysin for lysis, but my DNA yields are low. How can I optimize this?

Mutanolysin is a gentle enzyme, and its efficiency can be influenced by the preparation and lysis conditions.

- Confirm Preparation and Storage: Ensure the enzyme is stored correctly and is not expired.

- Optimize Incubation: Increase the enzyme concentration or extend the incubation time. Gentle agitation during incubation can improve contact between the enzyme and cells.

- Combine with a Detergent: Follow the mutanolysin treatment with a detergent-based lysis step to ensure complete disruption of the cell membrane and release of intracellular components [32].

Q4: What is the key difference between Zymolyase and Lyticase for yeast cell lysis?

Both are enzyme complexes used for yeast lysis, but they have different activity profiles. Zymolyase contains a primary enzyme (β-1,3-glucan laminaripentaohydrolase), protease, and mannanase, which work synergistically to strongly and efficiently degrade yeast cell walls. Lyticase, derived from a similar organism, has a different activity profile and is sometimes reported to be less effective for the complete cellular lysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae [33].

Table 1: Specialist Enzymes for Bacterial Lysis

| Enzyme | Target Bond / Specificity | Primary Bacterial Targets | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysozyme [30] | Hydrolyzes β(1→4) linkages between NAM & NAG in peptidoglycan. | Many Gram-positive & some Gram-negative bacteria. | Most common; ineffective against lysozyme-resistant strains. |

| Lysostaphin [31] | Endopeptidase; cleaves pentaglycine bridges in peptidoglycan. | Staphylococcus species (e.g., S. aureus). | Highly specific and effective for staphylococci. |

| Labiase [33] [32] | Glycosidase (β-N-acetyl-D-glucosamidase) and muramidase. | Broad-spectrum Gram-positive (e.g., Lactobacillus, Streptococcus). | Used for DNA extraction and lysis of resistant Gram-positive bacteria. |

| Mutanolysin [33] | Muramidase (cleaves peptidoglycan). | Listeria, Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus. | Known for being a gentle lysis enzyme; ideal for DNA isolation and protoplast formation. |

| Achromopeptidase [33] | Endopeptidase with specificity for Lys/- bonds. | Lysozyme-resistant Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Staphylococcus). | Retains activity in 0.1% SDS and 5M urea. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Lysis Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Lysis | Incorrect enzyme for the bacterial strain. | Confirm strain's peptidoglycan structure and switch to a specialist enzyme (e.g., use lysostaphin for S. aureus). |

| Low DNA/Protein Yield | Insufficient enzyme activity or harsh physical lysis. | Optimize enzyme concentration and incubation time; use gentler enzymatic lysis over physical methods [32]. |

| Lysis of Gram-negative Bacteria | Outer membrane blocks enzyme access to peptidoglycan. | Pre-treat cells with a detergent (e.g., SDS) or a chelating agent (e.g., EDTA) to permeabilize the outer membrane [33]. |

Experimental Protocols

General Protocol for Bacterial Lysis Using Specialist Enzymes

This protocol is adapted for enzymes like lysostaphin, labiase, and mutanolysin for Gram-positive bacteria [33].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: Bacterial cell pellet, Specialist lytic enzyme (e.g., lysostaphin, labiase), Lysis buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, with 20% sucrose), Osmotic stabilizer (e.g., sucrose or mannitol for protoplast formation), Detergent (e.g., 1% SDS for complete lysis), Protease-free water.

- Equipment: Centrifuge, Water bath or incubator, Vortex mixer, Microcentrifuge tubes.

Method:

- Cell Harvesting: Grow bacteria to the desired growth phase (e.g., log-phase). Harvest cells by centrifugation (e.g., 5,000 rpm for 10 minutes). Wash the cell pellet twice and resuspend in an appropriate lysis buffer containing an osmotic stabilizer to prevent premature lysis.

- Enzyme Addition: Add the selected lytic enzyme to the cell suspension. Typical working concentrations are 20-100 µg/mL for lysostaphin and mutanolysin, but this should be optimized for your specific strain and application.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at 37°C for 30-60 minutes with gentle agitation. For particularly resilient strains, incubation time may be extended.

- Complete Lysis: After enzymatic weakening of the cell wall, complete lysis can be achieved by adding a detergent (e.g., SDS) and/or transferring the solution to a hypotonic buffer, which will cause the protoplasts to lyse.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate (e.g., 12,000g for 10 minutes) to remove intact cells and debris. The supernatant contains the released intracellular components.

Protocol for DNA Extraction via Electrochemical Lysis (ECL)

This protocol offers a reagent-free, rapid alternative to enzymatic lysis, particularly useful for environmental samples [27].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: Sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄) solution (50 mM), Bacterial suspension in Na₂SO₄, Cation exchange membrane (e.g., Nafion 117).

- Equipment: ECL device (with IrO₂/Ti anode and Ti cathode), Potentiostat, Syringes.

Method:

- Device Setup: Inject 50 mM Na₂SO₄ into the anodic chamber and the bacterial suspension into the cathodic chamber of the ECL device, which is separated by a cation exchange membrane.

- Lysis: Apply a constant direct current (e.g., 40 mA, corresponding to ~5 V) for an optimal duration of 1 minute. This locally generates hydroxide (high pH) at the cathode surface, disrupting the microbial cell membranes.

- Collection: Collect the cathodic effluent, which contains the lysed cells and released DNA. The ECL method has been shown to have DNA extraction efficiencies similar to commercial kits for various waterborne bacteria [27].

Visualization: Enzyme Lysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting and applying the appropriate lysis method for bacterial research.

Diagram 1: Enzyme Selection Workflow. This chart outlines the decision-making process for choosing a lysis strategy based on bacterial cell wall structure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Enzymatic Bacterial Lysis

| Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Lysostaphin | Endopeptidase that specifically cleaves pentaglycine cross-bridges in the peptidoglycan of Staphylococcus species. [31] | Highly efficient lysis of S. aureus for DNA extraction or protein purification. |

| Labiase | Enzyme complex with broad-spectrum lytic activity against many Gram-positive bacteria. [32] | Lysis of hard-to-lyse bacteria like Lactobacillus and Streptococcus. |

| Mutanolysin | A gentle muramidase that hydrolyzes peptidoglycan. [33] | Generation of protoplasts and DNA isolation from sensitive bacterial strains. |

| Achromopeptidase | A broad-spectrum endopeptidase active in SDS and urea. [33] | Lysis of lysozyme-resistant Gram-positive bacteria under denaturing conditions. |

| Zymolyase | Enzyme complex containing β-1,3-glucanase, protease, and mannanase for yeast cell wall degradation. [33] | Efficient lysis of yeast cells for nucleic acid extraction or protoplast formation. |

| Osmotic Buffers | Solutions containing sucrose or mannitol to maintain osmotic pressure and prevent premature lysis of protoplasts. [33] | Used during enzymatic digestion to generate intact protoplasts. |

| Electrochemical Cell | Device using low voltage (~5 V) to generate localized high pH at the cathode for reagent-free cell lysis. [27] | Rapid DNA extraction from both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in environmental samples. |

For researchers focused on inefficient lysis of Gram-positive bacteria, selecting and optimizing mechanical disruption techniques is a critical step in sample preparation. Gram-positive bacteria, with their thick, multi-layered peptidoglycan cell walls, present a significant challenge compared to Gram-negative species [34] [29]. This guide provides detailed troubleshooting and methodological support for the three primary mechanical lysis technologies, framing them within the context of robust Gram-positive bacteria research.

FAQs on Mechanical Lysis Technologies

1. How do the core mechanisms of different mechanical lysis methods affect their efficiency on Gram-positive bacteria?

The effectiveness of a lysis method is directly tied to how its mechanical force overcomes the robust peptidoglycan structure of Gram-positive cell walls [29].

- Bead Milling primarily utilizes shear forces. The grinding action between beads, the sample, and the mill's internal components physically grinds down the tough cell wall [35].

- High-Pressure Homogenization (HPH) relies heavily on cavitation forces, along with shear and impact. As the bacterial suspension is forced through a narrow valve at high pressure, sudden pressure drops cause bubbles to form and implode, generating shockwaves that rupture the cell wall [35].

- Microfluidic Shearing employs a combination of mechanical shearing and contact killing. As bacteria are pumped through a porous polymeric monolith, they experience shear stress. The polymeric material itself also has an antibacterial ("contact killing") effect that contributes to cell disruption [28].

2. What are the key performance differences when lysing Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative bacteria?

Efficiency varies significantly between bacterial types due to fundamental differences in cell wall structure. The table below summarizes these performance differences based on the lysis mechanism.

Table 1: Lysis Performance Comparison for Gram-Positive vs. Gram-Negative Bacteria

| Lysis Method | Core Mechanism | Gram-Positive Efficiency | Gram-Negative Efficiency | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bead Milling | Shear forces [35] | High (Physically grinds thick peptidoglycan) | High | Effective for nano-crystalline suspensions, implying robust particle disruption [35]. |

| High-Pressure Homogenization | Cavitation and shear forces [35] | Moderate to High | High | Cavitation forces are effective, but thick cell walls may require higher pressure/cycles [35]. |

| Microfluidic Shearing | Mechanical shearing & contact killing [28] | Moderate (Less efficient than for Gram-negative) | High | Study showed "more efficient lysis for gram-negative than for gram-positive bacteria." [28] |

| Enzymatic (Lysozyme) | Hydrolyzes peptidoglycan bonds [29] | High (Due to high peptidoglycan content) | Low (Requires pre-treatment to permeate outer membrane) [29] | Activity against Gram-negative bacteria is enhanced by additives like EDTA and glycine [29] [4]. |

3. Can these mechanical methods be integrated with other lysis approaches for more stubborn Gram-positive species?

Yes, a hybrid approach is often highly effective. Pre-treating a bacterial suspension with enzymes like lysozyme or lysostaphin can weaken the peptidoglycan layer [29]. Following this with a mechanical method like bead milling or HPH can drastically improve lysis efficiency and reduce the processing time and energy required. This is particularly useful for difficult-to-lyse species like Bacillus subtilis or Lactobacillus.

Troubleshooting Guides

Bead Mill Troubleshooting

Table 2: Common Bead Mill Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Grinding Performance | Incorrect grinding media size/type; Worn components (impeller, chamber) [36]. | Select smaller or denser beads for tougher cells; Inspect and replace worn parts regularly [36]. |

| Overheating | Excessive friction; Inadequate cooling; High operating temperatures [36]. | Optimize bead loading and material; Ensure cooling system is unclogged and functional; Monitor and control processing temperature [36]. |

| Sample Leakage | Worn seals or gaskets; Loose connections [36]. | Regularly inspect and replace seals with chemically compatible parts; Tighten all connections to manufacturer's specifications [36]. |

| Blockage | Processing high-viscosity samples or samples with large aggregates [36]. | Pre-homogenize or sieve the sample; Ensure thorough cleaning between runs to prevent residue buildup [36]. |

High-Pressure Homogenizer Troubleshooting

Table 3: Common High-Pressure Homogenizer Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Homogenization Pressure | Leaking homogenizing valve or check valves; Worn plunger seals [37]. | Inspect and replace worn O-rings, homogenizing valve seat, or check valve components [37]. |

| Reduced Flow Rate | Leaking plunger seal; Broken valve spring; Airlock in the system [37]. | Replace plunger seals; Inspect and replace valve springs; Purge air from the feed line and pump [37]. |

| Main Motor Overload | Homogenizing pressure set excessively high; Worn or damaged transmission components [37]. | Reduce operating pressure to within specified limits; Inspect drive assembly for wear and damage [37]. |

| Abnormal Noise/Vibration | Unbalanced components; Loose connections; Worn bearings [36]. | Have components professionally balanced; Tighten all connections; Replace worn bearings promptly [36]. |

Microfluidic Shearing Chip Troubleshooting

Table 4: Common Microfluidic Shearing Chip Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Lysis Efficiency | Flow rate is too low or too high; Clogged porous polymeric monolith (PPM); Incompatible chip surface. | Optimize flow rate as per experimental validation (e.g., ~35 min/cycle [28]); Back-flush the chip to clear debris [28]. |

| Clogging of Microchannels | High cell concentration; Presence of cell debris or other particulates. | Dilute sample to an appropriate concentration (e.g., 10^5 CFU/mL used in validation [28]); Pre-filter the sample to remove large aggregates. |

| DNA Carryover Between Samples | Inadequate cleaning and regeneration of the PPM between runs [28]. | Implement a strict back-flushing and regeneration protocol between samples. The validated design allowed 20 reuse cycles without carryover [28]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mechanical Lysis

| Item | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Lysozyme | Hydrolyzes β(1-4) linkages between N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid in peptidoglycan [29]. | Weakening Gram-positive cell walls prior to mechanical lysis; used in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) with EDTA and Triton X-100 [29]. |

| Lysostaphin | Zinc metalloendopeptidase that specifically cleaves the pentaglycine cross-links in Staphylococcus peptidoglycan [29]. | Highly specific lysis of Staphylococcus species, either alone or in combination with mechanical methods. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelates divalent cations (Mg2+, Ca2+), disrupting the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and stabilizing released nucleic acids [29]. | Used in lysozyme buffers to enhance the lysis of Gram-negative bacteria by compromising their outer membrane integrity [29]. |

| Glycine & Charged Amino Acids | Enhances the bacteriolytic activity of lysozyme, particularly against Gram-negative bacteria [4]. | Adding glycine, histidine, or arginine to lysis buffers can significantly increase the rate of E. coli lysis by soluble lysozyme [4]. |

| Grinding Beads (Ceramic, Glass, Zirconia) | Media for bead milling; different sizes and materials impart varying degrees of shear force and impact energy [36]. | Zirconia beads (0.1-0.5 mm) are often used for efficient bacterial cell lysis due to their high density and effectiveness. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Protocol: Microfluidic Shearing for On-Chip Lysis

This protocol is adapted from the validation of a porous polymeric monolith (PPM) microfluidic biochip [28].

- Chip Fabrication: The biochip is fabricated from cross-linked poly(methyl methacrylate) (X-PMMA) via laser micromachining. A porous polymeric monolith (PPM) is formed within the structure, providing the mechanical and contact-killing surface [28].

- Sample Preparation: Suspend bacterial cells (e.g., Enterococcus saccharolyticus or Bacillus subtilis) in an appropriate buffer at a concentration of approximately 10^5 CFU/mL [28].

- Lysis Procedure:

- Load the bacterial suspension into a syringe pump system connected to the biochip.

- Pump the suspension through the PPM at the optimized flow rate. The study indicated that the contribution of contact killing was more important than that of mechanical shearing in the PPM [28].

- Collect the lysate effluent from the chip outlet. The biochip acts as a filter, retaining cell debris while allowing PCR-amplifiable DNA to pass through [28].

- Regeneration and Reuse:

- Between cycles, back-flush the chip with a cleaning buffer to remove trapped debris and prevent DNA carryover.

- The validated system efficiently completed a lysis and regeneration cycle in about 35 minutes and was reused for 20 cycles without significant performance degradation [28].

Workflow Diagram: Decision Framework for Lysis Method Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting and optimizing a mechanical lysis method based on bacterial sample type and research objectives.

Chemical and detergent-based lysis is a fundamental technique for breaking open bacterial cells to release their internal components for analysis. The efficiency of this process is highly dependent on the complex structure of the bacterial cell wall. Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis, present a particular challenge for researchers. Their cell walls feature a thick, multilayered peptidoglycan structure that is extensively cross-linked, providing significant strength and rigidity [38]. This robust barrier makes gram-positive bacteria inherently more resistant to standard lysis methods compared to gram-negative bacteria, which possess a thinner peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane [38] [39]. Overcoming this structural integrity is crucial for efficient DNA extraction, protein purification, and other downstream applications in research and drug development.

Standardized Lysis Protocol for Gram-Positive Bacteria

The following table summarizes a detailed methodology for the chemical lysis of gram-positive bacteria, adapted from a sucrose-mediated detergent lysis protocol that has been successfully applied to both Staphylococcus aureus (gram-positive) and Escherichia coli (gram-negative) organisms [40].

Table: Detailed Protocol for Sucrose-Mediated Detergent Lysis of Gram-Positive Bacteria

| Protocol Step | Reagents & Formulations | Conditions & Parameters | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Osmotic Shock | Trizma buffer (pH 8.0) containing 100% sucrose [40]. | Incubate bacterial pellet with sucrose solution to form osmotically sensitive cells [40]. | Creates a hypertonic environment, causing the protoplasm to shrink and detach from the rigid cell wall [40]. |

| 2. Detergent Lysis | Lysis mixture containing Brij 58 (non-ionic detergent) and Sodium Deoxycholate (ionic detergent) [40]. | Mix thoroughly and incubate. Avoid vortexing too vigorously to prevent genomic DNA shearing [40] [25]. | Detergents solubilize lipids and proteins in the cell membrane, creating pores and disrupting membrane integrity [41]. |

| 3. Debris Removal | - | Centrifuge at 15,000 rpm for 30 minutes to pellet cell debris and chromosomal DNA [40]. | The supercoiled plasmid DNA remains in the supernatant while larger cellular components are pelleted. |

| 4. Nucleic Acid Precipitation | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) or Isopropanol [40]. Use Sodium Acetate as a co-precipitant [25]. | Precipitate on ice for 20 mins at -20°C to -40°C; for low yield, extend to 30-60 mins [25]. | Reduces the solubility of nucleic acids, causing them to come out of solution. |

| 5. Protein Removal | Buffer containing Tris, EDTA, NaCl, and Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) [40]. | Dissolve the precipitate in the buffer to denature and remove proteins [40]. | SDS denatures proteins, while EDTA chelates metal ions required for many enzyme activities. |

| 6. RNA Removal | RNase treatment [40]. | Ensure lyophilized RNase is completely dissolved in the resuspension buffer before first use [25]. | Degrades contaminating RNA, which would otherwise co-purify with the target DNA. |

This protocol offers a cost-effective alternative to methods using high-priced enzymes like lysostaphin or lysozyme, replacing them with a sucrose-mediated osmotic shock [40]. The resulting plasmid DNA is of high quality, suitable for restriction enzyme digestion, cloning, transformation, and electron microscopy [40].

Workflow Diagram of the Lysis Process

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key mechanisms involved in the chemical lysis of gram-positive bacteria.

Troubleshooting Common Lysis Problems: FAQs

FAQ 1: I am getting low DNA yield from my gram-positive bacterial cultures. What could be the cause? Low yield is a common issue with hard-to-lyse gram-positive bacteria. The causes and solutions are multifaceted:

- Cause: Incomplete cell lysis due to insufficient resuspension of the cell pellet or an overly dense culture [25].

- Solution: Ensure the cell pellet is fully and gently resuspended in the initial buffer before adding lysis detergents. Reduce the culture volume to avoid overloading the lysis reaction [25].

- Cause: The culture is too old and the bacteria have entered the death phase [25].

- Solution: Always use freshly grown cultures, not exceeding 24 hours. If you must pause, pellet the cells and store them at -70°C [25].

- Cause: The alkaline lysis step is inefficient due to precipitates in the lysis solution [25].

- Solution: Check your lysis solution (e.g., NaOH/SDS) for salt precipitates and ensure it is fresh and properly prepared [25].

FAQ 2: My lysate is contaminated with a large amount of genomic DNA. How can I prevent this? Genomic DNA contamination often arises from overly vigorous mechanical disruption during lysis.

- Cause: Vortexing or pipetting too vigorously during the lysis and neutralization steps [25].

- Solution: After adding the lysis detergents, mix the contents by inverting the tube gently several times instead of vortexing. This shears the cells without excessively breaking the larger genomic DNA strands [25].

FAQ 3: My lysis buffer doesn't seem to be working effectively on my gram-positive strain. How can I optimize it? The effectiveness of your lysis buffer is critical for gram-positive bacteria.

- Cause: The detergent concentration may be too low, or the ratio of detergent to membrane mass may be insufficient [42].

- Solution: For non-ionic detergents, ensure the concentration is around 1.0%. If you are preparing your own buffer, this can be tricky; consider using a commercial lysis buffer or kit to ensure optimal concentrations of all reagents [42].

- Cause: The thick peptidoglycan layer of gram-positive bacteria is not being adequately disrupted [38] [39].

- Solution: Consider a hybrid chemical/mechanical approach. One effective method is to pass the bacteria through a porous polymer monolith under pressure in the presence of detergents, which combines shear forces with chemical lysis [38]. Alternatively, supplement your lysis buffer with higher amounts of specific enzymes like lysozyme or mutanolysin that hydrolyze the peptidoglycan layer [38] [39].

FAQ 4: The purified plasmid DNA performs poorly in downstream applications like cloning or transformation. What might be wrong? Poor downstream performance often indicates the presence of contaminants or plasmid damage.

- Cause: Denaturation of the plasmid DNA due to prolonged incubation in the alkaline lysis step [25].

- Solution: Strictly adhere to the recommended incubation times for lysis and neutralization. Do not extend these times.

- Cause: Carry-over of ethanol from the wash steps [25].

- Solution: Increase the drying time of the pellet or column after the final wash to ensure all ethanol has evaporated before elution.

- Cause: Residual salts or contaminants from the lysis process.

- Solution: Use a salt like sodium acetate during precipitation, as it is particularly effective for plasmid DNA purification [25]. Ensure all supernatant is removed after precipitation steps.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Lysis

The following table catalogs key reagents and their specific functions in chemical and detergent-based lysis protocols, providing a quick reference for researchers.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bacterial Lysis

| Reagent Name | Category | Function in Lysis Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Sucrose | Osmotic Agent | Creates a hypertonic solution for the initial osmotic shock, detaching the protoplasm from the cell wall [40]. |

| Brij 58 | Non-ionic Detergent | Solubilizes membrane lipids and proteins during the lysis step, working in concert with other detergents [40]. |

| Sodium Deoxycholate | Ionic Detergent | Disrupts lipid bilayers and solubilizes membranes, enhancing the lysis of osmotically sensitive cells [40]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic Detergent | Strongly denatures proteins and solubilizes membranes; crucial for protein removal and alkaline lysis protocols [40] [41]. |

| Sodium Acetate | Salt / Precipitant | The positively charged sodium ions neutralize the negative charge of the DNA backbone, making plasmids hydrophobic and less soluble during alcohol precipitation [25]. |

| Lysozyme | Enzymatic Agent | Hydrolyzes the β-(1,4) glycosidic linkages between N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid in the peptidoglycan layer, specifically weakening the cell wall [38]. |

| RNase A | Nuclease | Degrades contaminating RNA molecules after lysis, ensuring they do not co-purify with the target plasmid DNA [40]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Alkaline Agent | Key component of alkaline lysis; denatures DNA and contributes to membrane disruption at high pH (11.5-12.5) [41] [43]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Encountered Issues and Solutions

Q1: My electrochemical lysis protocol works well for E. coli but is inefficient for gram-positive bacteria like Bacillus subtilis. What could be the issue?

A: This is a common challenge due to structural differences in bacterial cell walls. Gram-positive bacteria possess a thick, multi-layered peptidoglycan structure that provides greater structural resistance to breakage compared to the thinner envelope of gram-negative bacteria [44]. To enhance lysis efficiency for gram-positive strains:

- Increase treatment duration: While gram-negative bacteria may lyse completely within 1 minute, gram-positive species might require extended exposure times [27].

- Optimize electrical parameters: Consider slightly increasing the voltage (within the 5-7.5V range) to enhance hydroxide generation [45].

- Combine methods: Pre-treatment with lysozyme (5-10 mg/mL in TRIS-HCl buffer with polyethylene glycol) can weaken the peptidoglycan layer, making gram-positive cells more susceptible to subsequent electrochemical lysis [46].

Q2: I'm observing inconsistent lysis efficiency between experiments with the same parameters. How can I improve reproducibility?

A: Inconsistent results often stem from electrode-related issues or solution conditions [47]:

- Electrode maintenance: Regularly inspect and clean electrode surfaces between experiments. Fouling can significantly alter the local pH generation at the cathode. Use electrochemical cleaning techniques or gentle mechanical polishing to restore surface activity [47].

- Solution conductivity: Maintain consistent electrolyte composition (e.g., 50 mM Na₂SO₄) and concentration across experiments, as this directly affects current flow and hydroxide generation [27].

- Standardize bacterial preparation: Ensure consistent bacterial growth phase (log-phase cells are typically more susceptible) and washing procedures to minimize contaminating media components that might buffer pH changes [27].

Q3: The DNA yield from my lysed samples is low or degraded. What optimization steps can I take?

A: This issue may result from excessive lysis conditions or nuclease activity:

- Optimize lysis duration: Over-exposure to high pH can damage nucleic acids. Perform a time-course experiment to identify the minimum duration needed for efficient lysis without significant DNA degradation [27].

- Control temperature: Electrochemical processes can generate heat. Implement cooling (ice bath or Peltier cooling) to maintain samples at 4-10°C during lysis to preserve nucleic acid integrity [27].

- Add nuclease inhibitors: Include DNase inhibitors in your suspension buffer, especially for longer processing times [48].

Performance Comparison of Electrochemical Lysis Across Bacterial Types

Table 1: Lysis efficiency of electrochemical methods across different bacterial classifications

| Bacterial Type | Example Species | Optimal Voltage | Optimal Duration | Relative Efficiency | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative | Escherichia coli, Salmonella Typhi | ~5 V | 1 minute | High [27] [49] | Minimal; thin cell envelope |

| Gram-negative | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 5-25 V | 60-6000 s (energy-dependent) | Moderate to High [45] | Variable resistance patterns |

| Gram-positive | Enterococcus durans, Bacillus subtilis | ~5 V | 1+ minutes | Moderate [27] [49] | Thick peptidoglycan layer |

| Gram-positive | Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis | 2.5-25 V | 60-6000 s (energy-dependent) | Lower than gram-negative [45] | Enhanced structural resistance |

Table 2: Electrical energy effects on bacterial viability and resistance

| Electrical Energy | Gram-negative Reduction | Gram-positive Reduction | Metabolic Activity Suppression | Antibiotic Resistance Impairment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 J | ~20-30% | ~10-20% | Not significant | Not significant |

| 60 J | ~40-50% | ~25-35% | 20-30% | ~20% |

| 140 J | >78% | 47-73% | 41-75% | >64.2% |

| 240-562.5 J | >90% | 70-85% | >80% | >80% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Electrochemical Lysis for DNA Extraction

Application: DNA extraction from both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria in environmental water samples [27] [49]

Materials:

- Electrochemical cell: Custom polycarbonate reactor with IrO₂/Ti anode and Ti cathode