Overcoming PCR Inhibition and Difficult Templates: A Comprehensive Optimization Guide for Researchers

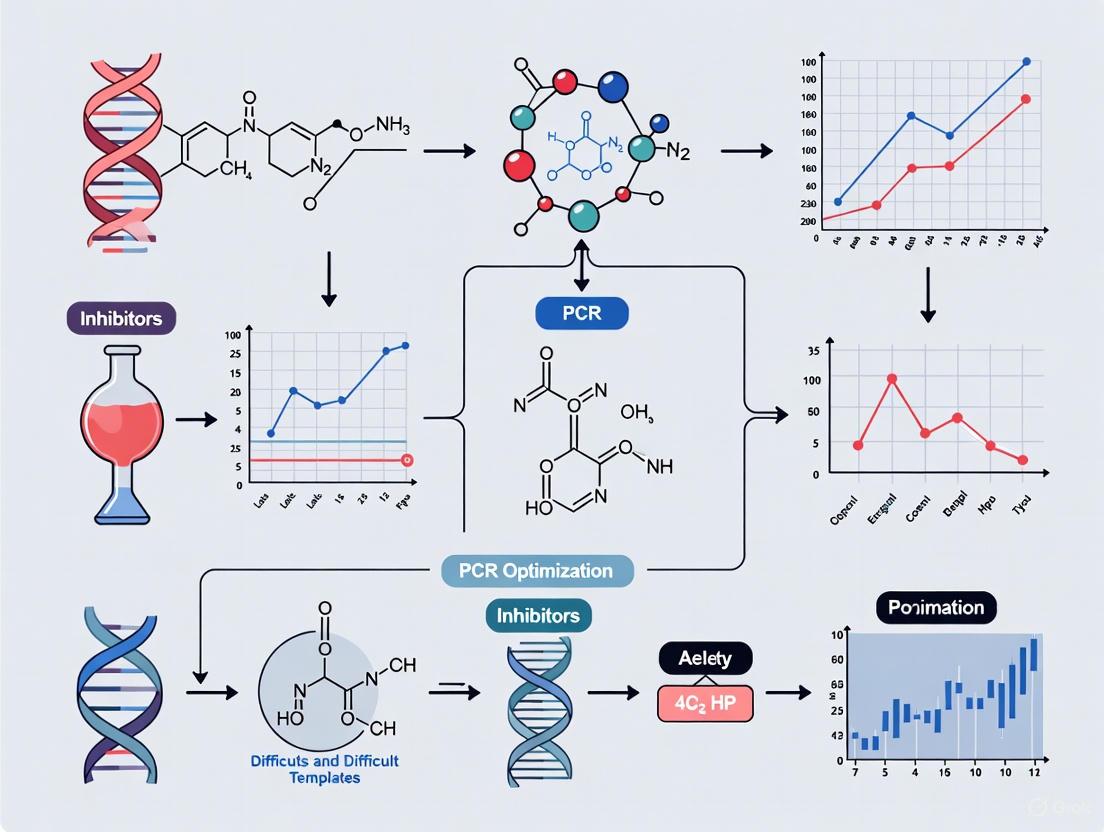

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing challenges in PCR amplification due to inhibitors and difficult templates.

Overcoming PCR Inhibition and Difficult Templates: A Comprehensive Optimization Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing challenges in PCR amplification due to inhibitors and difficult templates. It covers the foundational science behind amplification failures, explores advanced methodological strategies for sample preparation and reagent selection, offers a detailed troubleshooting framework for optimization, and discusses validation techniques to ensure data reliability. By synthesizing current knowledge and practical solutions, this guide aims to equip scientists with the tools to achieve robust, specific, and efficient PCR results even with the most challenging samples in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding the Enemies of Amplification: A Deep Dive into PCR Inhibitors and Difficult Templates

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a cornerstone technique in molecular biology, enabling the amplification of specific DNA sequences. However, the presence of PCR inhibitors in various sample types can severely compromise reaction efficiency, leading to reduced sensitivity, false negatives, and inaccurate quantification. Understanding the sources and mechanisms of these inhibitors is essential for developing effective countermeasures and ensuring reliable results in research and diagnostics [1]. This guide provides a detailed overview of PCR inhibitors, presented in a troubleshooting format for researchers and scientists.

PCR inhibitors originate from a wide array of sources, including the sample matrix itself, reagents used in sample preparation, and components of the sample's biological origin. The table below summarizes the principal sources and examples of common inhibitors.

Table 1: Common Sources and Examples of PCR Inhibitors

| Source Category | Specific Sources | Example Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Samples | Blood, tissues, feces | Hemoglobin, immunoglobulin G (IgG), lactoferrin, bile salts [2] [1] |

| Environmental Samples | Soil, sediment, wastewater | Humic acid, fulvic acid, humin, tannins, heavy metals [3] [1] |

| Food Samples | Spices, dairy, meat | Complex polysaccharides, lipids, proteins, secondary metabolites [4] |

| Laboratory Reagents | Extraction chemicals | Phenol, EDTA, proteinase K, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) [2] [5] |

How do PCR inhibitors exert their effects?

Inhibitors interfere with the PCR process through diverse mechanisms, primarily targeting the DNA polymerase enzyme, the nucleic acid template, or the fluorescence detection system. The diagram below illustrates the primary mechanisms of action and their effects on the PCR workflow.

The following table provides a more detailed breakdown of these mechanisms for specific inhibitors.

Table 2: Mechanisms of Action for Specific PCR Inhibitors

| Inhibitor | Primary Mechanism of Action | Impact on PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Humic Acid | Binds directly to DNA polymerase, blocking its active site; can also chelate Mg²⁺ and quench fluorescence [1] | Reduced amplification efficiency; inaccurate quantification in qPCR/dPCR |

| Hemoglobin / Hematin | Interacts with and inhibits DNA polymerase activity [5] [1] | Suppression of amplification, leading to false negatives |

| Heparin | Highly negatively charged; interacts with the positively charged DNA polymerase and Mg²⁺ cofactors [1] | Prevents polymerase from functioning and disrupts primer annealing |

| EDTA | Chelates Mg²⁺ ions, which are essential cofactors for DNA polymerase [2] [1] | Impairs enzyme activity and halts the extension step |

| Polysaccharides & Polyphenols | Can bind to nucleic acids, making the template inaccessible for polymerization [4] | Prevents primer annealing and elongation |

| Urea | Denatures DNA polymerase enzyme [5] | Disrupts enzyme structure and function |

What experimental strategies can mitigate PCR inhibition?

A multi-faceted approach is often required to overcome PCR inhibition, ranging from sample pre-treatment to optimization of the amplification reaction itself. The workflow below outlines a systematic strategy for dealing with inhibitory samples.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Strategies

A. Use of PCR Enhancers and Additives

Adding specific compounds to the PCR mixture can counteract inhibitors. The optimal type and concentration must be determined empirically [6] [3].

- Procedure:

- Prepare a standard PCR master mix.

- Aliquot the master mix into separate tubes.

- Add a different enhancer to each tube. Common enhancers and their tested concentrations include:

- Run the PCR with the same template and cycling conditions.

- Compare the amplification efficiency (e.g., Cq values, band intensity) to a control reaction without enhancers.

B. Sample Dilution

Diluting the nucleic acid extract reduces the concentration of inhibitors below a critical threshold.

- Procedure:

- Perform a standard DNA/RNA extraction.

- Prepare a series of dilutions (e.g., 1:2, 1:5, 1:10) of the extracted nucleic acids in nuclease-free water or TE buffer.

- Use each dilution as a template in parallel PCR or qPCR reactions.

- Identify the dilution that yields optimal amplification. Note that excessive dilution can also reduce the target concentration below the detection limit [3].

C. Advanced Polymerase and Platform Selection

Switching to inhibitor-tolerant enzyme formulations or digital PCR can provide a robust solution.

- Procedure for Evaluating Polymerases:

- Select several commercial DNA polymerases known for inhibitor tolerance (e.g., those blended with proteins that bind inhibitors or engineered for stability).

- Set up identical PCR reactions with the inhibitory sample template using each polymerase according to their respective optimized protocols.

- Compare the yield, specificity, and Cq values. Inhibitor-tolerant polymerases often maintain performance where standard Taq fails [5] [1].

- Consider Digital PCR (dPCR): For quantification, dPCR is often more resistant to inhibitors than qPCR because it relies on end-point measurement and partitioning, which effectively reduces the local concentration of inhibitors in positive partitions [3] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents and materials used to combat PCR inhibition.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Overcoming PCR Inhibition

| Reagent/Material | Function in Overcoming Inhibition |

|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerase | Specialized enzyme blends (e.g., containing affinity mutants or competitor proteins) designed to remain active in the presence of common inhibitors like humic acid or hematin [5] [1] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Binds to and neutralizes a wide range of inhibitors, including polyphenols, tannins, and humic acids, preventing them from interacting with the polymerase or DNA [6] [3] |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Destabilizes DNA secondary structures, which is crucial for amplifying GC-rich templates; also helps overcome inhibition by improving reaction stringency [6] [3] |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) | A single-stranded DNA-binding protein that stabilizes denatured DNA, prevents secondary structure formation, and can relieve inhibition from complex matrices [3] |

| Inhibitor Removal Kits | Silica-based columns or chemical matrices specifically designed to bind and remove inhibitory compounds (e.g., humic substances, polyphenols) during nucleic acid purification [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My positive control amplifies, but my sample does not. Is this a sign of inhibition? Yes, this is a classic indicator of PCR inhibition. The successful amplification of the positive control confirms that your PCR reagents and thermal cycler are functioning correctly, pointing to an issue within the sample itself, likely the presence of inhibitors [7].

Q2: Why does diluting my DNA sample sometimes restore amplification? Dilution reduces the concentration of both the template DNA and the inhibitors. If the inhibitors are diluted below their effective concentration while the target DNA remains above the detection limit of the assay, amplification can proceed. This is a practical, though not always optimal, test for and solution to inhibition [3].

Q3: Are some PCR methods more susceptible to inhibitors than others? Yes. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is highly susceptible because inhibitors can affect the amplification efficiency, which directly skews the quantification cycle (Cq) and leads to inaccurate results. Digital PCR (dPCR) is generally more tolerant because it is an end-point measurement and the partitioning step can reduce the local concentration of inhibitors in individual droplets or wells [1].

Q4: How can I confirm that my sample contains PCR inhibitors? You can perform a spike-in experiment. Take an aliquot of your sample DNA and add a known quantity of a control DNA template (with its own specific primers). Run a PCR targeting this control. If the amplification of the control is suppressed or delayed compared to a reaction where it is spiked into clean water, then your sample contains inhibitors [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: PCR Inhibition

The tables below summarize common symptoms, their causes, and recommended solutions to help you identify and overcome inhibition in your PCR experiments.

Table 1: Troubleshooting No or Weak Amplification

| Possible Cause | Specific Examples of Inhibitors | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Inhibitors in Template | Phenol, EDTA, heparin, hemoglobin, polysaccharides, humic acids, urea, ethanol, detergents (SDS) [8] [9]. | Dilute template 100-fold; purify template via ethanol precipitation or commercial clean-up kit; use inhibitor-tolerant polymerases [8] [9]. |

| Complex Template DNA | High GC-content (>65%) leading to secondary structures [8] [9]. | Use a polymerase formulated for high-GC templates; add PCR co-solvents like DMSO or GC Enhancer; increase denaturation temperature/time [8] [9]. |

| Suboptimal Reaction Components | Insufficient Mg2+ concentration; excess EDTA chelating Mg2+; unbalanced dNTP concentrations [8] [9]. | Optimize Mg2+ concentration (ensure it exceeds total dNTP concentration); use equimolar dNTP concentrations [8] [9]. |

| Insufficient Enzyme or Template | Low abundance target; enzyme quantity too low for conditions [8] [10]. | Increase number of PCR cycles (up to 40); increase amount of DNA polymerase, especially with additives; choose high-sensitivity enzymes [8] [10]. |

Table 2: Addressing Nonspecific Products, Smearing, and Errors

| Symptom & Cause | Underlying Reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Nonspecific Bands / Primer-Dimers | Primers binding nonspecific sites; low annealing temperature; excessive primer concentration [8] [9]. | Increase annealing temperature; use hot-start DNA polymerase; optimize primer concentration (0.1-1 µM); use touchdown PCR [8] [9]. |

| Smearing | Over-cycling; excess template; poor primer design; contamination [9]. | Reduce number of cycles; decrease template amount; redesign primers; use nested primers; decontaminate workspace [9]. |

| High Error Rate (Low Fidelity) | Low-fidelity DNA polymerase; excess Mg2+; unbalanced dNTPs; over-cycling; UV-damaged DNA [8] [9]. | Use high-fidelity polymerase; optimize Mg2+ and use balanced dNTPs; reduce cycle number; limit UV exposure during gel extraction [8] [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Inhibitors can originate from your sample or reagents. Common sources include:

- Sample-Derived: Hemoglobin (blood), heparin (anticoagulant), humic acids (plants, soil), polysaccharides (bacteria, plants), collagen (tissues), and melanin [9].

- Reagent-Derived: Phenol, EDTA, SDS, ethanol, or salts carried over from template purification protocols [8] [9].

- Contamination: Cross-contamination from previous PCR products (amplicons) or exogenous DNA from the lab environment [9].

My template has high GC content. How can I amplify it successfully?

GC-rich sequences (>65%) form stable secondary structures that polymerases cannot unwind. To overcome this:

- Use a specialized polymerase designed for high-GC templates [9] [10].

- Include additives or co-solvents like DMSO, formamide, or GC Enhancer in your reaction mix to help denature these structures [8].

- Adjust thermal cycler parameters: Increase denaturation temperature and/or time to ensure complete strand separation [8].

I suspect my reaction is contaminated. How do I decontaminate my workspace?

Contamination manifests as smearing or false-positive amplification in your negative (no-template) control [9].

- Physically Separate Work Areas: Maintain distinct, dedicated pre-PCR (reaction setup) and post-PCR (amplification, analysis) areas. Never bring equipment or reagents from the post-PCR area back to the pre-PCR area [9].

- Decontaminate Surfaces and Equipment: Wipe down workstations and pipettes with 10% bleach. Leave pipettes under UV light in a laminar flow hood overnight [9].

- Use Dedicated Reagents: Aliquot reagents for pre-PCR use only. Always include a negative control reaction to monitor for contamination [9].

How does a hot-start DNA polymerase prevent nonspecific amplification?

Nonspecific amplification and primer-dimers often form during reaction setup at low temperatures when non-hot-start polymerases are partially active. Hot-start polymerases are inactive at room temperature, either via an antibody or chemical modification. They only become active after a high-temperature activation step (e.g., 95°C for 2-5 minutes), preventing enzymatic activity during setup and ensuring specificity [8] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Overcoming PCR Challenges

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Prevents nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation by remaining inactive until a high-temperature activation step [8] [9]. | Standard PCR to improve specificity; complex templates. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Reduces misincorporation of nucleotides due to 3'→5' exonuclease (proofreading) activity [8]. | PCR for cloning, sequencing, or mutagenesis where sequence accuracy is critical. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant Polymerase | Engineered to maintain activity in the presence of common PCR inhibitors carried over from sample preparation [8] [9]. | Amplification from crude samples (e.g., blood, soil, plant tissue). |

| GC Enhancer / DMSO | Additives that lower the melting temperature of DNA, helping to denature GC-rich sequences and secondary structures [8] [9]. | Amplification of difficult templates with high GC content or stable hairpins. |

| PCR Clean-up Kit | Purifies DNA fragments or template to remove salts, proteins, and other enzymatic inhibitors [9]. | Post-amplification purification or template cleanup before PCR. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Detailed Methodology: Screening for Novel Polymerase Inhibitors

This protocol is adapted from recent research using computational and biochemical methods to identify SARS-CoV-2 RdRp inhibitors [11].

Objective: To identify small-molecule inhibitors targeting a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) through in silico docking and biochemical validation.

Workflow:

Key Steps:

- In Silico Docking:

- Target Preparation: Obtain the 3D crystal structure of the target polymerase complex (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 nsp12/7/8, PDB: 7BV2). Define binding sites: the orthosteric site (active site) and potential allosteric sites (e.g., Palm, Thumb domains) [11].

- Library Screening: Screen extensive libraries (e.g., >10,000 "Safe-In-Man" compounds for repurposing, >249,000 natural compounds) against the defined sites using molecular docking software [11].

- Hit Selection:

- Filter results based on docking score significance (e.g., >2 standard deviations above mean).

- Prioritize compounds with novelty (not previously reported as inhibitors) and favorable clinical safety profiles (e.g., passed Phase I trials) [11].

- Biochemical Validation (RTC Assay):

- Assay Setup: Use a purified polymerase complex. A common method is a primer-elongation assay with a Cy5-labeled RNA primer and an unlabeled RNA template, resolved by PAGE [11].

- Optimization: Determine optimal buffer pH, NaCl, and MgCl₂ concentrations, reaction time (e.g., 45 min at 37°C), and enzyme concentration [11].

- Inhibition Testing: Incolate candidate compounds with the polymerase complex and substrates. Calculate IC₅₀ values (concentration for 50% inhibition of enzymatic activity) [11].

- Cell-Based Validation:

- Test efficacy of hits in a cellular context using a viral replication assay (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 infected cells) to determine EC₅₀ values (concentration for 50% reduction in viral replication) [11].

Methodology: Machine Learning for DNA Polymerase Inhibitor Discovery

This protocol outlines a modern computational approach to discover and optimize small-molecule inhibitors, as demonstrated for human DNA polymerase η (hpol η) [12].

Objective: To use machine learning (ML)-enhanced QSAR modeling to predict the inhibitory activity of novel chemical compounds against a target DNA polymerase.

Workflow:

Key Steps:

- Dataset Curation:

- Compile a library of compounds with experimentally validated inhibition data (e.g., percent reduction in polymerase activity). Remove outliers to ensure data integrity [12].

- Descriptor Calculation and Feature Engineering:

- Convert chemical structures to SMILES format and generate 3D molecular models.

- Calculate a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors (1D-4D), including molecular weight, topological indices, dipole moment, and electronic properties like HOMO/LUMO energies [12].

- Model Training and Validation:

- Train multiple ML algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost, Neural Networks) on a training subset (e.g., 80% of data).

- Use k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) and hyperparameter optimization to ensure model robustness and prevent overfitting [12].

- Model Interpretation and Prediction:

- Use tools like SHAP analysis to identify which molecular descriptors (e.g., lipophilicity, specific atomic distances) are the strongest predictors of inhibition, guiding chemical optimization [12].

- Employ the best-performing model to screen virtual chemical libraries and prioritize novel compounds for synthesis and experimental testing [12].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

No PCR Product or Low Yield

Q: My PCR reaction is failing to produce a visible product on a gel, or the yield is very low. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A: This common issue, often called "PCR failure," can stem from problems with the template, reagents, or cycling conditions. The table below outlines systematic solutions.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Supporting Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Template | - Increase template amount; for low-copy targets, use 10-100 ng of genomic DNA or up to 1 µg for complex genomes [13] [8].- Increase cycle number to 35-40 [14] [6]. | Protocol for Low-Copy Targets: Use a high-sensitivity polymerase. Set up a 50 µL reaction with 34-40 cycles. Include an initial denaturation at 98°C for 1 min, followed by cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 60 s/kb, with a final extension of 5 min [6]. |

| PCR Inhibitors Present | - Dilute template DNA 10- to 100-fold [14] [3].- Purify template using silica-column kits or ethanol precipitation [13].- Use an inhibitor-tolerant DNA polymerase blend [15] [16].- Add PCR enhancers like BSA (100-400 ng/µL) or TWEEN-20 (0.1-1%) to the master mix [6] [3]. | Inhibitor Removal Protocol: For a contaminated sample, perform ethanol precipitation: add 0.1 volumes of 3M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 2 volumes of 100% ethanol to your DNA sample. Incubate at -20°C for 1 hour, centrifuge at >12,000 g for 15 min, wash with 70% ethanol, and resuspend in nuclease-free water [8]. |

| Suboptimal Primer Design/Annealing | - Recalculate primer Tm and test an annealing temperature gradient starting 5°C below the lower Tm [13].- Ensure primers are 15-30 nucleotides long with 40-60% GC content [6].- Check for primer-dimer formation and re-design if necessary [16]. | Annealing Temperature Optimization Protocol: Design a gradient PCR with annealing temperatures ranging from 50°C to 70°C. Use a standardized reaction mix and analyze products on an agarose gel to identify the temperature that gives the strongest specific band [13] [8]. |

| Denaturation or Extension Issues | - For GC-rich templates, increase denaturation temperature to 98°C and/or time to 5 minutes initially [8] [6].- Ensure extension time is sufficient; generally 1 min/kb is standard, but increase for long amplicons [14]. | Enhanced Denaturation Protocol: For a stubborn GC-rich template, use a "long initial denaturation" step of 98°C for 3-5 minutes before cycling. During cycling, use a denaturation temperature of 98°C for 20 seconds [6]. |

Nonspecific Amplification and Multiple Bands

Q: My PCR produces multiple bands or a smear on the gel instead of a single, clean product. How can I improve specificity?

A: Nonspecific amplification occurs when primers bind to incorrect sequences. The key is to increase the reaction stringency.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Supporting Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Annealing Temperature Too Low | - Increase annealing temperature in 2°C increments [14].- Use a touchdown PCR protocol [8] [14]. | Touchdown PCR Protocol: Start cycles 10°C above the calculated Tm, then decrease the annealing temperature by 1°C every cycle until a "touchdown" temperature is reached. Continue with the remaining cycles at this lower temperature. This ensures only the specific primer-template hybrids form initially [14]. |

| Excess Enzyme, Primers, or Mg²⁺ | - Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration in 0.2-1 mM increments [13].- Reduce primer concentration to 0.1-0.5 µM [8] [6].- Use a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent activity at room temperature [13] [16]. | Mg²⁺ Optimization Protocol: Set up a series of reactions with a fixed template and primer concentration, varying the MgCl₂ concentration from 1.0 mM to 3.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments. Analyze the results by gel electrophoresis to find the concentration that gives the strongest specific product with the least background [13]. |

| Too Much Template | - Reduce the amount of template DNA by 2- to 5-fold [14]. | Template Titration Protocol: Set up identical reactions with template amounts of 10 ng, 25 ng, 50 ng, and 100 ng. Often, lower amounts of template reduce competition for primers and decrease nonspecific binding [14]. |

PCR-Induced Sequence Errors

Q: My sequenced PCR product contains mutations not present in the original template. How can I improve fidelity?

A: Sequence errors are often introduced by the DNA polymerase and can be minimized by using high-fidelity enzymes and optimizing reaction conditions.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Supporting Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | - Use a high-fidelity polymerase with 3'→5' exonuclease (proofreading) activity, such as Q5 or Phusion [13] [6]. | High-Fidelity PCR Protocol: Use a proofreading polymerase according to manufacturer's instructions. A typical 50 µL reaction may contain 1X HF buffer, 200 µM dNTPs, 0.5 µM primers, 50 ng template, and 1 unit of polymerase. Cycle using a minimal number of cycles [13] [6]. |

| Unbalanced dNTPs or Excess Mg²⁺ | - Use fresh, equimolar dNTP mixes (200 µM of each dNTP) [13] [8].- Avoid excessive Mg²⁺ concentrations, as this can reduce proofreading efficiency [14]. | dNTP/Mg²⁺ Balancing Protocol: Prepare a master mix with balanced dNTPs and an optimized, minimal concentration of Mg²⁺ as determined by a prior optimization experiment. This reduces the chance of base misincorporation [14]. |

| Too Many Cycles | - Reduce the number of PCR cycles (e.g., from 35 to 25-30) to minimize accumulation of errors [17] [14]. | Cycle Minimization Protocol: Perform a PCR with a series of cycle numbers (e.g., 25, 28, 30, 35). Use the lowest number of cycles that still produces a sufficient yield for your downstream application [17]. |

Specialized Focus: Optimizing Challenging Templates

GC-Rich Regions

GC-rich templates (>60% GC content) form stable secondary structures that prevent efficient denaturation and primer annealing.

Solutions and Protocols:

- Use PCR Enhancers: Additives like DMSO (1-10%), formamide (1.25-10%), or glycerol help destabilize secondary structures by interfering with hydrogen bonding [8] [6] [3].

- Protocol: Add 3-5% DMSO to the master mix. Note that DMSO also lowers the effective primer Tm, so a slight decrease in annealing temperature may be needed.

- Choose a Specialized Polymerase: Use polymerases with high processivity, specifically formulated for GC-rich templates [13] [14].

- Apply a High Denaturation Temperature: Use a polymerase that remains stable at 98°C and employ a higher denaturation temperature throughout the cycling process [8].

- Utilize a GC-Rich Enhancer Solution: Some manufacturers provide proprietary GC enhancer solutions that can be added to the reaction [13].

Long Amplicons

Amplifying long DNA fragments (>5 kb) is challenging due to the increased likelihood of polymerase dissociation and the accumulation of replication errors.

Solutions and Protocols:

- Blend Polymerases: Use a mix of a high-fidelity, proofreading polymerase (e.g., Pfu) with a high-processivity polymerase (e.g., Taq). This combines accuracy with the ability to synthesize long stretches of DNA [6].

- Extend Extension Time: Increase the extension time to 1-2 minutes per kilobase to allow the polymerase to complete synthesis of long strands [14].

- Reduce Annealing and Extension Temperatures: Slightly lower temperatures (e.g., 68°C for extension) can help maintain polymerase stability and processivity over long periods [8].

- Optimize Template Quality: Ensure template DNA is high-molecular-weight and intact, as sheared DNA will not support long-range PCR.

Low-Copy Number Targets

Amplifying targets present in very few copies (e.g., single-copy genes in complex genomic DNA, or pathogens in early infection) requires maximizing sensitivity while avoiding false positives from contamination.

Solutions and Protocols:

- Increase Cycle Number: Run up to 40 cycles to increase the probability of amplifying rare targets [14] [6].

- Use a High-Sensitivity Polymerase: Select polymerases engineered for high sensitivity and robust performance with minimal template [8].

- Apply Nested PCR: Perform two consecutive PCRs. The first uses an outer primer pair to amplify a larger region. A small aliquot of this first reaction is then used as the template for a second PCR with primers that bind inside the first amplicon. This dramatically increases specificity and yield [14].

- Prevent Contamination: Use strict laboratory practices, including separate pre- and post-PCR work areas, aerosol-resistant pipette tips, and incorporating Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG) to degrade PCR products from previous reactions [16] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following reagents are critical for successfully troubleshooting and optimizing PCR for difficult templates.

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in PCR Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerases | Q5 High-Fidelity, Phusion Flash, OneTaq Hot Start, PrimeSTAR GXL [13] [16] [14] | Provide high fidelity, inhibitor tolerance, processivity for long targets, or hot-start capability for improved specificity. |

| PCR Enhancers & Additives | DMSO, Formamide, Glycerol, BSA, Tween-20, Betaine [6] [3] | Destabilize secondary structures in GC-rich templates, protect enzyme activity, or bind to inhibitors present in the sample. |

| Hot-Start Enzymes | OneTaq Hot Start, Platinum Taq, Hot Start Taq [13] [8] [16] | Remain inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup. |

| dNTPs & Buffers | Balanced dNTP Mix (200 µM each), Mg²⁺-Free Buffers, GC Enhancer Buffers [13] [14] [6] | Provide optimized co-factors (Mg²⁺) and nucleotide building blocks. Specialized buffers are formulated for specific challenges like high GC content. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making pathway for selecting the right optimization strategy based on the observed PCR problem.

This workflow provides a systematic approach for researchers to diagnose and resolve the most common PCR issues associated with difficult templates.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What makes GC-rich DNA sequences so difficult to amplify?

GC-rich sequences (typically defined as over 60% GC content) present two major biochemical challenges that hinder amplification:

- Thermal and Structural Stability: Guanine (G) and cytosine (C) form base pairs with three hydrogen bonds, unlike adenine (A) and thymine (T) pairs, which form only two. This results in greater thermostability, requiring more energy (higher temperatures) to denature the double-stranded DNA [18] [19]. This increased stability is also significantly contributed to by base-stacking interactions between adjacent GC pairs [19].

- Formation of Stable Secondary Structures: GC-rich regions readily fold into stable intramolecular secondary structures, such as hairpin loops. These structures can form faster than the primers can anneal to the template. When the DNA polymerase encounters these structures, it can stall, resulting in truncated, incomplete amplification products [18] [20].

Besides GC-content, what other template features can cause PCR failure?

Several other template characteristics can lead to amplification failure or poor yield:

- Long Amplicons: Amplifying long DNA targets requires polymerases with high processivity and may need extended extension times [8].

- PCR Inhibitors: Substances co-purified with the template DNA can inhibit the polymerase. Common inhibitors include:

- Degraded Template: Sheared or nicked DNA template may not amplify efficiently [8].

My gel shows multiple bands or a smear. Is this related to secondary structures?

Not necessarily. While secondary structures can cause a smear of truncated products, multiple bands or smears are most often a sign of non-specific amplification [22] [8]. This occurs when your primers anneal to incorrect, off-target sites on the DNA template. This is typically addressed by:

- Increasing the annealing temperature to enhance primer stringency [18] [8].

- Using a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent enzyme activity during reaction setup at lower temperatures [8] [23].

- Optimizing Mg²⁺ concentration, as excess Mg²⁺ can reduce specificity [18] [8].

What is a "primer-dimer," and how does it form?

Primer-dimer is an amplification artifact where the two primers anneal to each other via complementary 3' ends and are extended by the polymerase. This results in a short, non-target product that can be seen on a gel as a low molecular weight band [24] [23]. It consumes reagents and competes with the desired amplification, reducing yield. It is promoted by low annealing temperatures, high primer concentrations, and primers designed with complementarity at their 3' ends [24] [23].

Troubleshooting Guide: Optimizing PCR for Difficult Templates

Step 1: Reagent Optimization

The choice of polymerase and buffer system is the most critical factor for amplifying challenging templates.

Table 1: Polymerase and Buffer Systems for Difficult Templates

| Reagent | Function & Mechanism | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerase Blends | Engineered for high processivity and affinity to unwind stable templates; often have higher tolerance to inhibitors [18] [8]. | OneTaq DNA Polymerase, Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, AccuPrime GC-Rich DNA Polymerase [18] [19]. |

| GC Enhancer / Additives | Chemical additives that destabilize secondary structures by reducing the melting temperature of GC-rich DNA, helping to keep the template accessible [18] [19]. | OneTaq High GC Enhancer, Q5 High GC Enhancer, DMSO, Betaine, Formamide [18]. |

| Magnesium Ion (Mg²⁺) Optimization | Mg²⁺ is an essential cofactor for polymerase activity. Its concentration must be optimized; too little reduces activity, and too much promotes non-specific binding [18] [24]. | Typically tested in 0.5 mM increments from 1.0 mM to 4.0 mM [18]. |

Step 2: Cycling Condition Modifications

Adjusting the thermal cycler protocol can help overcome thermodynamic barriers.

Table 2: Modified Cycling Parameters for GC-Rich Templates

| Parameter | Standard Approach | Optimization for GC-Rich Templates |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 94-95°C for 2-5 minutes. | 98°C for 5-10 minutes for complete denaturation of stable structures [19]. |

| Denaturation Cycle | 94-95°C for 15-30 seconds. | 98°C for 10-20 seconds. Use with a polymerase stable at high temperatures [19]. |

| Annealing Temperature (Ta) | 3-5°C below primer Tm. | Use a temperature gradient to determine the highest possible Ta that still yields product. Start 5-7°C below Tm [18] [8]. |

| Extension | 68-72°C; time based on polymerase speed. | May require slight extension time increases if polymerase stalls [8]. |

| Final Extension | 5-10 minutes. | 10-15 minutes to ensure all products are fully extended [8]. |

| Cycle Number | 25-35 cycles. | Up to 40 cycles for low-yield targets [8]. |

Step 3: Advanced Techniques

For persistently difficult targets, consider these advanced methods:

- Slow-down PCR: This method incorporates a dGTP analog (7-deaza-2′-deoxyguanosine) into the reaction. This analog reduces the strength of hydrogen bonding without affecting base-pairing specificity, thereby lowering the melting temperature of GC-rich regions. The protocol also uses slow ramp rates between cycling steps and an increased number of cycles [19] [20].

- Touchdown PCR: This technique starts with an annealing temperature higher than the calculated Tm and gradually decreases it in subsequent cycles. This ensures that only the most specific primer-template hybrids (formed in the initial, high-stringency cycles) are amplified, improving specificity for complex templates [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Challenging Amplifications

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Processivity DNA Polymerase | Polymerases with high affinity for the template DNA and the ability to add many nucleotides without dissociating are crucial for navigating through regions with stable secondary structures [18] [8]. |

| GC Enhancer / Betaine | Betaine is a biologically compatible solute that equalizes the thermal stability of AT and GC base pairs. It reduces the formation of secondary structures by lowering the melting temperature of GC-rich DNA, making it easier to denature [18] [21]. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | An organic solvent that disrupts the base-pairing of DNA, helping to prevent the formation of secondary structures like hairpins. It can also influence the thermal activity profile of the DNA polymerase [21] [19] [20]. |

| Hot-Start Taq Polymerase | A modified polymerase that is inactive until a high-temperature activation step. This prevents non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup at room temperature, greatly improving amplification specificity and yield [8] [23]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A protein additive that acts as a "molecular sponge," binding to and neutralizing common PCR inhibitors that may be present in the sample, such as phenolics or humic acids [21] [23]. |

| dUTP/UNG Carryover Prevention System | A contamination control system where dTTP is replaced with dUTP in PCR mixes. Prior to amplification, the reaction is treated with Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG), which degrades any uracil-containing contaminants from previous PCRs, but leaves the natural thymine-containing template DNA intact [25]. |

Experimental Protocol: Amplifying a GC-Rich Promoter Region

This protocol is adapted from methodologies cited in the literature for robust amplification of difficult templates [18] [24].

Objective: To amplify a 1.2 kb GC-rich (75% GC) promoter region from human genomic DNA.

Materials:

- Template: 50 ng of high-quality human genomic DNA.

- Polymerase: Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB #M0491) or equivalent high-processivity enzyme.

- Buffers: Q5 Reaction Buffer (5X) and Q5 High GC Enhancer (5X) supplied with the polymerase.

- Primers: 10 µM each of forward and reverse primers, designed with Tms of ~72°C.

- dNTPs: 10 mM mixture.

- Nuclease-free water.

Method:

- Prepare Reaction Mix (50 µL total volume) on ice:

- Nuclease-free water: To 50 µL final volume.

- Q5 Reaction Buffer (5X): 10 µL.

- Q5 High GC Enhancer (5X): 10 µL.

- dNTPs (10 mM): 1 µL.

- Forward Primer (10 µM): 2.5 µL.

- Reverse Primer (10 µM): 2.5 µL.

- Template DNA: 2 µL (50 ng).

- Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase: 0.5 µL (1 unit).

- Thermal Cycling Program:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 5 minutes.

- 35 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 98°C for 20 seconds.

- Annealing: 72°C for 20 seconds (Note: This is high; optimize with a gradient).

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute 30 seconds.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 10 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C forever.

- Analysis:

- Run 5-10 µL of the PCR product on a 1% agarose gel to check for a single, sharp band of the expected size (1.2 kb).

Biochemical Pathways of PCR Inhibition by Secondary Structures

The following diagram illustrates the mechanisms by which stable intramolecular secondary structures in the DNA template lead to PCR failure.

FAQ: Recognizing and Troubleshooting PCR Inhibition

What are the primary signs that my PCR reaction is inhibited?

The table below summarizes the common signs of PCR inhibition and their manifestations in different PCR methods.

| Sign of Inhibition | Manifestation in Standard PCR | Manifestation in qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced or No Amplification | Faint or absent band on agarose gel [23] | Significantly higher quantification cycle (Cq) value, or complete absence of amplification (Cq ≥ 40) [3] [26] |

| Altered Amplification Kinetics | Not directly observable | Abnormal amplification curve shape; delayed signal increase or a flattened curve [26] |

| Inconsistent Replicate Results | Variable band intensity between identical samples | High variation in Cq values between technical replicates [27] |

| Low Signal Intensity | Faint bands even with adequate template input | Low fluorescence intensity, making accurate baseline and threshold setting difficult [26] |

How can I conclusively confirm the presence of an inhibitor?

The most definitive method is to use an internal control (IC) or spike-in assay [27]. This involves adding a known quantity of a non-target DNA sequence (e.g., from a plasmid or a different species) to your sample. If the amplification of this internal control is delayed or absent compared to its performance in a clean reaction, it confirms that the sample contains PCR inhibitors. Alternatively, you can perform a sample dilution test. A dilution series of your sample (e.g., 1:2, 1:5, 1:10) may show improved amplification at higher dilutions, as the inhibitors become less concentrated [3] [28].

What are the most effective strategies to overcome PCR inhibition?

Multiple strategies can be employed to mitigate inhibition, often in combination.

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Dilution | Reduces concentration of inhibitors below a critical threshold [3] [28] | Simplest approach; may reduce sensitivity; a 10-fold dilution is common [3]. |

| Additives & Enhancers | Binds to or neutralizes inhibitory substances [23] [3] | Additives are effective against specific inhibitor types; see Table 2 for details. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant Enzymes | Use of specialized polymerases less susceptible to common inhibitors [3] | Many commercial "robust" or "direct" PCR polymerases are available. |

| Improved Nucleic Acid Purification | Physical removal of inhibitors during extraction [23] [2] | Use of inhibitor removal kits or switching to more rigorous extraction protocols [3]. |

Which PCR enhancers should I use for my specific sample type?

The efficacy of an enhancer depends on the type of inhibitor present. The following table summarizes common additives and their applications based on experimental data.

| Enhancer | Recommended Concentration | Primary Function & Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | 200–400 ng/µL [27] | Binds to phenolic compounds and humic acids; useful for plant, soil, and fecal samples [3] [27]. |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) | Varies by manufacturer | Binds single-stranded DNA, prevents polymerase obstruction; effective against humic acids in wastewater [3]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 2–10% [28] | Disrupts secondary structures; ideal for GC-rich templates [3] [28]. |

| TWEEN 20 | Varies by manufacturer | Detergent that counteracts inhibitors in fecal samples [3]. |

| Betaine | 1–2 M [28] | Homogenizes base-pair stability; beneficial for GC-rich templates and long-range PCR [28]. |

My positive control is amplifying, but my sample is not. Is this always inhibition?

Not necessarily. While this is a classic sign of inhibition, other factors can cause the same result. You must also rule out:

- Degraded or insufficient template DNA in the sample [23] [27].

- Poor primer binding due to sequence polymorphisms or suboptimal annealing temperature [28] [29].

- Human error, such as forgetting to add the DNA template to the reaction [23]. Always verify that all necessary reagents were added correctly.

Experimental Protocols for Identifying and Overcoming Inhibition

Protocol 1: Internal Control (Spike-in) Assay for Inhibition Detection

This protocol provides a definitive test for the presence of PCR inhibitors in your sample.

- Prepare the Internal Control: Select a control amplicon (e.g., a plasmid or synthetic oligo) that is not present in your sample and for which you have validated primers and probe [27].

- Set Up Reactions:

- Test Sample Reaction: Prepare a PCR containing the patient's sample DNA and primers/probe for the internal control.

- Control Reaction: Prepare an identical PCR containing a known, inhibitor-free template (like water) spiked with the same amount of internal control.

- Run qPCR: Amplify both reactions using the same cycling conditions.

- Interpret Results: A significant delay (ΔCq > 2-3 cycles) or failure in the Cq value for the internal control in the test sample compared to the control reaction confirms the presence of inhibitors [27] [26].

Protocol 2: Systematic Evaluation of PCR Enhancers

This methodology, adapted from research on wastewater samples, allows for the direct comparison of different enhancers [3].

- Master Mix Preparation: Create a standard PCR master mix according to your established protocol.

- Aliquot and Supplement: Divide the master mix into several tubes. To each tube, add a single PCR enhancer from Table 2 at its recommended concentration. Keep one tube as an unsupplemented control.

- Run Amplification: Use the same sample and cycling conditions across all reactions.

- Analyze Performance: Compare the Cq values, amplification curve shapes, and end-point yields (e.g., gel electrophoresis) of the supplemented reactions to the control. The enhancer that yields the lowest Cq and strongest specific amplification is the most effective for that sample type [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Polymerase is inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [23] [28]. | Critical for improving assay specificity and sensitivity, especially with low-abundance targets. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Acts as a "molecular sponge," binding and neutralizing a range of inhibitors like humic acids and polyphenolic compounds [23] [3] [27]. | A versatile and inexpensive first-line defense against inhibition in complex biological and environmental samples. |

| dNTP Mix | Provides the essential nucleoside triphosphate building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for DNA synthesis [29]. | Imbalanced or degraded dNTPs are a common source of PCR failure; use fresh, high-quality aliquots. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Serves as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity; concentration critically affects enzyme fidelity, specificity, and yield [23] [28] [29]. | Requires optimization for each new primer-template system; typically tested between 0.5-5.0 mM [28] [29]. |

| Inhibitor Removal Kits | Silica-column or magnetic-bead based kits designed to selectively bind nucleic acids while washing away common inhibitors [3]. | Essential for samples known to be challenging, such as feces, soil, or formalin-fixed tissues. |

Workflow: A Systematic Path to Identify and Resolve PCR Inhibition

The following diagram illustrates a logical troubleshooting workflow to diagnose and address PCR inhibition in your experiments.

Strategic Sample Prep and Reagent Selection: Building a Robust PCR Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: How can I regenerate and reuse silica columns from PCR purification kits to reduce waste?

Silica columns, key components of commercial PCR purification and gel extraction kits, can be effectively regenerated and reused multiple times, significantly reducing plastic laboratory waste [30].

- Primary Cause of Failure: Residual DNA from previous purifications remains bound to the silica membrane, leading to potential carryover contamination in subsequent uses and a reduction in DNA-binding capacity [30].

- Recommended Solution: A regeneration protocol using phosphoric acid effectively removes contaminating DNA. A study shows that used columns regenerated with 1 M phosphoric acid perform comparably to fresh new columns and can be reused at least five times without sacrificing DNA purification quality or subsequent gene cloning efficiency [30].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Wash: Pass 1 mL of 1 M phosphoric acid through the used silica column.

- Rinse: Wash the column with 1 mL of molecular-grade water to remove the acid.

- Dry: Centrifuge the column briefly to remove residual liquid.

- Store: The regenerated column is now ready for reuse and can be stored at room temperature [30].

- Comparison of Regeneration Reagents: The following table summarizes the efficacy of different reagents in eliminating residual DNA, as measured by qPCR of the eluate from regenerated columns [30].

| Regeneration Reagent | Concentration | Residual DNA (pg/μL) |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphoric Acid | 1.0 M | 0.0031 |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | 1.0 M | 0.026 |

| SDS | 2% | 0.1356 |

| Triton X-100 | 0.5% | 0.1538 |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | 1.0 M | 0.we need to find a number |

| Deionized Water (ddH₂O) | - | 0.4712 |

| DNase I | 1X solution | >0.1356 (varies with incubation time) |

| Acidic Phenol | - | >0.026 |

FAQ: My PCR fails due to inhibitors in my sample (e.g., from wastewater, soil, or blood). What are my options?

Inhibition is a common problem when analyzing complex samples. Inhibitors such as humic acids, polysaccharides, phenols, or heparin can co-purify with nucleic acids and interfere with polymerase activity [28] [3] [31].

- Primary Cause: Inhibitors can interfere with PCR through various mechanisms, including binding to the DNA polymerase, degrading or sequestering nucleic acid templates, or chelating essential divalent cations like Mg²⁺ [3].

- Recommended Solutions: A multi-faceted approach is often required.

- Dilution: A simple 10-fold dilution of the DNA template can dilute inhibitors to a sub-critical concentration. However, this also dilutes the target DNA and may reduce sensitivity [28] [3].

- Additives: Adding PCR enhancers to the reaction mix can counteract inhibitors.

- Polymerase Selection: Using DNA polymerases engineered for high tolerance to inhibitors found in specific sample types (e.g., blood, plants, soil) [28] [8].

- Purification: Using commercial inhibitor removal kits or ethanol precipitation to purify the nucleic acid sample further [3] [31].

- Experimental Protocol for Evaluating PCR Enhancers: When dealing with a new type of inhibitory sample, systematically test additives in the PCR mixture. The table below lists common enhancers and their applications, particularly for challenging wastewater samples [3].

| PCR Enhancer | Typical Final Concentration | Mechanism of Action | Effectiveness in Wastewater |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | 400 ng/μL | Binds to inhibitors like humic acids, preventing them from interacting with the polymerase [3] [6]. | Moderate to High |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) | 50-100 ng/μL | Binds to single-stranded DNA, stabilizing it and preventing the action of inhibitors [3]. | Moderate to High |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 2-10% | Lowers the DNA melting temperature (Tm), helping to denature GC-rich secondary structures [28] [6]. | Low to Moderate |

| Tween 20 | 0.1-1% | A non-ionic detergent that can counteract inhibition of Taq DNA polymerase [3] [6]. | Low to Moderate |

| Glycerol | 5-10% | Stabilizes enzymes and can help with amplification of long templates [3] [6]. | Low |

| Formamide | 1.25-10% | Destabilizes DNA helices, increasing primer annealing specificity for GC-rich templates [3] [6]. | Low |

FAQ: How do I handle difficult PCR templates, such as those with high GC content or complex secondary structures?

GC-rich sequences (over 65%) form stable secondary structures that prevent efficient denaturation and primer annealing, leading to poor or failed amplification [8] [32] [6].

- Primary Cause: Strong hydrogen bonding in GC-rich regions creates stable intramolecular structures that are not fully denatured at standard temperatures, blocking polymerase progression [6].

- Recommended Solution: A combination of specialized reagents and adjusted thermal cycling parameters.

- Reagents: Use PCR additives like DMSO, formamide, or commercial GC enhancers. These compounds destabilize DNA secondary structures [8] [32] [6].

- Polymerase: Choose a polymerase with high processivity, which has a stronger affinity for the template and is better at amplifying through difficult regions [8].

- Cycling Conditions: Increase the denaturation temperature and/or time to ensure complete separation of DNA strands [8].

- Experimental Protocol for GC-Rich PCR:

- Prepare a 50 μL PCR reaction with a polymerase known for high processivity.

- Include an additive such as DMSO at a final concentration of 5% (v/v) or a commercial GC enhancer as per the manufacturer's instructions.

- Use the following modified thermal cycling profile:

Troubleshooting at a Glance: Common PCR Issues

This table provides a quick reference for identifying and resolving common PCR problems related to sample preparation and reaction components [8] [32] [31].

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Product | PCR inhibitors present in template | Dilute template; re-purify using ethanol precipitation or a cleanup kit; use inhibitor-tolerant polymerase [8] [32]. |

| Low template quality or quantity | Check DNA integrity by gel electrophoresis; increase amount of input DNA [8]. | |

| Multiple Bands or Smearing | Non-specific priming | Increase annealing temperature in 2°C increments; use a hot-start polymerase; optimize Mg²⁺ concentration [32] [31]. |

| Too much template or enzyme | Reduce template amount by 2–5 fold; reduce enzyme units [33] [31]. | |

| Low Yield | Suboptimal cycling conditions | Increase number of cycles (e.g., from 30 to 35); extend extension time for longer amplicons [8] [31]. |

| Primer-dimers or secondary structures | Redesign primers; use touchdown PCR; check for primer self-complementarity [28] [31]. | |

| High Error Rate (Low Fidelity) | Low-fidelity polymerase (e.g., standard Taq) | Switch to a high-fidelity polymerase with proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity (e.g., Pfu, Q5) [28] [32]. |

| Unbalanced dNTP or excessive Mg²⁺ | Use equimolar dNTP concentrations; titrate Mg²⁺ concentration to optimal level [32] [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Silica Columns | The core of many commercial kits for binding and purifying DNA from PCR reactions or gel slices [30]. |

| Phosphoric Acid (1 M) | Effective reagent for regenerating used silica columns by removing residual DNA contaminants [30]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Engineered to be inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [28] [32]. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Enzymes with proofreading ability (e.g., Pfu, Q5) that significantly reduce error rates in amplified products, essential for cloning and sequencing [28] [32]. |

| PCR Enhancers (BSA, DMSO, etc.) | Additives used to overcome inhibition or amplify difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich sequences) by various mechanisms [3] [6]. |

| QuEChERS Kits | A sample preparation method (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) originally developed for pesticide analysis in food, useful for complex matrices [34]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | A technique for cleaning and concentrating analytes from complex mixtures like biological fluids or environmental samples prior to analysis [34]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Sample to Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for processing complex samples, integrating purification, inhibition removal, and PCR optimization strategies.

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) optimization research, the selection of an appropriate DNA polymerase is a critical foundational step that directly determines the success or failure of an experiment. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this choice extends beyond mere amplification—it represents a strategic balance between the often-competing demands of sequence accuracy, amplification efficiency, and robustness to challenging sample conditions. Inhibitors in complex biological samples, difficult templates with high GC content or secondary structures, and the stringent requirements of downstream applications like cloning and sequencing make this balance particularly crucial. This technical support center article provides detailed troubleshooting guides and FAQs to address specific experimental challenges, framed within the broader context of PCR optimization research confronting today's life science laboratories.

Core Concepts: The DNA Polymerase Triad

Understanding the fundamental properties of DNA polymerases is essential for making an informed selection. Three characteristics are particularly vital for experimental success with challenging samples.

Fidelity: The Accuracy of Amplification

Fidelity refers to the accuracy with which a DNA polymerase replicates the template sequence. It is quantifiably expressed as the inverse of the error rate (e.g., number of errors per base pair duplicated) [35]. High-fidelity polymerases are indispensable for applications where sequence integrity is paramount, such as cloning, sequencing, and site-directed mutagenesis.

The proofreading capability, conferred by a dedicated 3'→5' exonuclease domain, is the primary mechanism for high fidelity. When a mismatched nucleotide is incorporated, the polymerase stalls due to unfavorable base-pairing kinetics. This delay allows the excision of the incorrect nucleotide by the exonuclease domain before synthesis resumes [35]. Naturally occurring proofreading enzymes like Pfu DNA polymerase possess approximately 10-fold higher fidelity than Taq polymerase, while engineered "next-generation" enzymes can achieve fidelity >50–300x that of Taq [35].

Processivity: The Efficiency of Amplification

Processivity is defined as the number of nucleotides a polymerase adds to a growing DNA chain in a single binding event [35] [36]. A highly processive enzyme remains bound to the template for longer, incorporating more nucleotides per encounter.

This property directly impacts synthesis speed and the ability to amplify long templates, GC-rich sequences, and targets with secondary structures [35]. Furthermore, high processivity often confers better performance in the presence of PCR inhibitors commonly found in blood, plant tissues, and soil samples (e.g., heparin, xylan, humic acid) [35]. Early proofreading polymerases often suffered from low processivity, but engineering solutions, such as fusing the polymerase with a strong DNA-binding domain, have successfully enhanced processivity 2- to 5-fold without compromising other functions [35].

Inhibitor Tolerance: Amplification in Complex Samples

Inhibitor Tolerance is the polymerase's ability to perform amplification even in the presence of substances that typically impede PCR. Such inhibitors include hemoglobin and immunoglobulin G in blood, humic acid in soil, and laboratory carryover agents like phenol and EDTA [37] [8] [38].

The effect of inhibitors is primarily upon the DNA polymerase itself [37]. Research has shown that mutational alteration of polymerases can overcome this inhibition. For instance, an N-terminal deletion mutant (Klentaq1) was found to be 10–100 times more resistant to whole blood inhibition than wild-type Taq polymerase [37]. This property is crucial for developing extraction-free "direct PCR" protocols, which simplify workflows, reduce contamination risk, and minimize template loss [39].

Technical Selection Guide

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of different polymerase types to guide your selection. A detailed comparison of polymerase properties helps in making an informed decision based on experimental needs.

Table 1: DNA Polymerase Selection Guide

| Polymerase Type | Key Features | Primary Applications | Fidelity (Relative to Taq) | Inhibitor Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Taq | No proofreading; high speed | Routine screening, genotyping, diagnostic assays [28] | 1x | Low |

| High-Fidelity (e.g., Pfu, Q5) | Possesses 3'→5' proofreading exonuclease [28] | Cloning, sequencing, site-directed mutagenesis [35] [28] | ~10x for natural enzymes; >50x for engineered [35] | Low to Moderate |

| Engineered/Chimeric | Often blends or fusions for enhanced performance | Forensic analysis, direct PCR from crude samples [38] [39] | Variable (often high) | High [38] [39] |

| Hot-Start | Inactive at room temperature; requires heat activation [28] | All applications, especially high-throughput setups; increases specificity [35] [8] | Varies (can be combined with fidelity) | Varies |

The decision-making process for selecting the right polymerase involves evaluating several key aspects of your experimental design. The workflow below outlines the critical questions to guide your selection strategy.

Troubleshooting Common PCR Issues

This section addresses specific problems researchers encounter, their likely causes, and evidence-based solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Common PCR Problems

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Product | PCR Inhibitors from crude samples (blood, soil) [8] | Use an inhibitor-tolerant polymerase [37], further purify template, or dilute extract [8]. |

| Poor Template Quality (degraded DNA) [8] | Re-purify template; use integrity gels for assessment; store DNA properly [8]. | |

| Complex Template (e.g., high GC, secondary structures) [8] | Use a polymerase with high processivity; add co-solvents like DMSO or betaine [8] [28]. | |

| Multiple or Non-Specific Bands | Primer Annealing Temperature Too Low [28] [40] | Increase annealing temperature; optimize using a gradient cycler [8] [28]. |

| Premature Replication during reaction setup [40] | Use a hot-start polymerase [35] [8]; set up reactions on ice [8]. | |

| Excess Mg2+ Concentration [8] [40] | Optimize Mg2+ concentration in 0.2–1 mM increments [40]. | |

| Sequence Errors in Product | Low Fidelity Polymerase [8] [40] | Switch to a high-fidelity polymerase with proofreading activity [35] [40]. |

| Unbalanced dNTP Concentrations [8] | Ensure equimolar concentrations of all four dNTPs; prepare fresh dNTP mixes [8] [40]. | |

| Excessive Number of Cycles [8] | Reduce the number of PCR cycles without drastically compromising yield [8]. |

Advanced Solutions for Demanding Applications

Engineered Polymerases for Superior Performance

For the most challenging research scenarios, such as forensic analysis or direct detection from crude samples, standard polymerases may be insufficient. Advanced solutions include:

- Polymerase Blends: Combining different polymerases can create a synergistic effect. One study validated a 1:1 blend of ExTaq Hot Start and PicoMaxx High Fidelity for forensic DNA profiling, which detected at least as many STR markers as AmpliTaq Gold across normal samples and produced significantly more complete profiles from severely inhibitory samples [38].

- Chimeric Polymerases: Engineering novel enzymes by fusing domains from different polymerases can yield superior properties. A recent study created a chimeric B-family polymerase (KUpF) by combining domains from KOD and Pfu polymerases and fusing it with a flap endonuclease (pFEN1) to confer 5'→3' exonuclease activity for probe-based qPCR. This enzyme demonstrated high inhibitor tolerance, enabling an extraction-free qPCR assay for African swine fever virus detection directly from blood and tissue samples without nucleic acid purification [39].

Optimizing Reaction Components

Even with the right polymerase, reaction composition is critical.

- Magnesium Ion (Mg2+) Optimization: Mg2+ is an essential cofactor. Its concentration must be carefully titrated, typically between 1.5 and 4.0 mM [28]. Low Mg2+ leads to reduced enzyme activity and poor yield, while high Mg2+ promotes non-specific amplification and lowers fidelity [28].

- Use of Additives:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PCR Optimization

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Polymerase (e.g., Pfu, Q5) | Accurate DNA synthesis for cloning and sequencing | Check for proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity and fidelity rating [35] [40]. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant Polymerase (e.g., Klentaq mutants, KUpF) | Amplification from crude samples (blood, soil) without DNA extraction | Enables "direct PCR" workflows, saving time and reducing template loss [37] [39]. |

| Hot-Start Polymerase | Prevents nonspecific amplification during reaction setup | Activated by high temperature; crucial for specificity and room-temperature setup [35] [8]. |

| MgCl2 or MgSO4 | Essential cofactor for polymerase activity | Concentration requires optimization; significantly affects specificity, yield, and fidelity [8] [28]. |

| PCR Additives (DMSO, Betaine) | Assist in denaturing complex templates | Use the lowest effective concentration; may require adjustment of annealing temperature [8] [28]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most common cause of non-specific amplification, and how can I fix it? The most common cause is an annealing temperature that is too low, which reduces the stringency of primer binding [28]. The solution is to increase the annealing temperature incrementally, ideally using a gradient thermal cycler. Furthermore, using a hot-start polymerase can prevent the synthesis of nonspecific products that form during reaction setup at room temperature [35] [8].

Q2: How does a high-fidelity polymerase actually work? High-fidelity polymerases possess a proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity that occurs in a domain separate from the polymerase active site [35]. After a mismatched nucleotide is incorporated, DNA synthesis stalls. This delay allows the exonuclease domain to excise the incorrect nucleotide before the polymerase resumes DNA synthesis with the correct nucleotide [35]. This corrective mechanism drastically reduces the error rate.

Q3: My PCR works with purified DNA but fails with crude blood/soil samples. What should I do? This is a classic sign of PCR inhibition. Instead of extensive re-purification, consider using a polymerase engineered for high inhibitor tolerance [37]. Mutants of Taq polymerase and certain chimeric B-family polymerases have been specifically developed to resist potent inhibitors like hemoglobin (from blood) and humic acid (from soil), often enabling successful amplification without any DNA purification [37] [39].

Q4: When should I use a buffer additive like DMSO or betaine? Consider these additives when amplifying difficult templates, such as those with high GC content (above 65%) or strong secondary structures [28]. DMSO helps denature these stable structures, while betaine equalizes the melting temperature across the template. Remember to use the lowest effective concentration, as high concentrations can inhibit the polymerase and may necessitate an adjustment to the annealing temperature [8] [28].

Q5: Can I improve my PCR results without changing the polymerase? Yes. Several parameters can be optimized:

- Primer Design: Ensure primers have a matched Tm (55–65°C), avoid self-complementarity, and have a stable 3' end [28].

- Thermal Cycling: Optimize annealing temperature and ensure adequate denaturation and extension times [8].

- Template Quality: Re-purify degraded DNA or dilute samples to reduce carryover inhibitors [8] [28].

- Mg2+ Concentration: Titrate Mg2+ in small increments, as it is a critical variable [28] [40].

Polymersse Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, yet the amplification of difficult templates—such as those with high GC-content, complex secondary structures, or the presence of inhibitors—remains a significant challenge in research and diagnostic applications. The optimization of PCR efficiency and specificity is particularly crucial in drug development, where reliable genetic data is paramount. A key strategy for overcoming these challenges involves the use of PCR additives. This guide focuses on four common additives—Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO), Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Betaine, and Formamide—detailing their mechanisms, applications, and integration into robust experimental protocols. By harnessing these reagents, researchers can significantly enhance the performance of their PCR assays, ensuring success with even the most recalcitrant templates.

Understanding the Additives: Mechanisms and Applications

PCR additives enhance amplification through distinct biochemical mechanisms, primarily by facilitating DNA denaturation, reducing secondary structures, or neutralizing inhibitors. The following table provides a comparative overview of the key additives discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Essential PCR Additives: Mechanisms and Applications

| Additive | Primary Mechanism of Action | Ideal For | Recommended Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | Disrupts base pairing by interacting with water molecules, reducing DNA melting temperature (Tm) and secondary structure stability [41] [42]. | GC-rich templates [41] [43]. | 2% - 10% (v/v); requires optimization [41] [42]. |

| Betaine | Equalizes the stability of GC and AT base pairs by interacting with DNA strands, eliminating base composition dependence of DNA melting; an osmoprotectant that reduces DNA secondary structures [41] [43] [42]. | GC-rich templates; reduces non-specific amplification [41]. | 0.5 M - 2.5 M (often used at 1-1.7M) [41] [43]. |

| Formamide | Lowers DNA Tm by binding to the grooves of the DNA double helix, destabilizing hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions [41] [42]. | Improving specificity; reducing non-specific priming [41]. | 1% - 5% (v/v); effective concentration range can be narrow [41] [44]. |

| BSA | Binds and neutralizes PCR inhibitors (e.g., phenolic compounds); reduces adhesion of reactants to tube walls [41] [44] [42]. | Reactions with inhibitor carryover (e.g., from soil, blood, plant tissues); can co-enhance with solvents [41] [44]. | 0.1 - 1.0 µg/µL (or 10-100 µg/mL) [44] [24]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs and Solutions

This section addresses common experimental challenges, providing targeted solutions involving PCR additives.

How do I amplify a GC-rich DNA template?

GC-rich sequences (GC content >60%) are problematic due to their propensity to form stable secondary structures and require higher denaturation temperatures [44].

Solution:

- Use a combination of additives: A synergistic approach is often most effective.

- Primary Choice: Incorporate Betaine (0.5 M - 2.5 M). It is particularly effective for GC-rich templates as it promotes a more uniform melting of the DNA [41] [43].

- Co-Additive: Use DMSO (2% - 10%). It helps destabilize secondary structures but can inhibit polymerase activity at higher concentrations, so optimization is critical [41].

- Co-Enhancer: Add BSA (0.1 - 1.0 µg/µL). Research shows BSA can further enhance yields when used with DMSO or formamide, especially for GC-rich targets [44].

- Optimize thermal cycling parameters: Increase the denaturation temperature (e.g., to 98°C) and/or time [8].

- Consider the polymerase: Choose a DNA polymerase with high processivity and affinity for complex templates [8].

Diagram: Strategic workflow for optimizing PCR amplification of GC-rich templates

My PCR shows multiple non-specific bands. How can I improve specificity?

Non-specific amplification occurs when primers bind to unintended sites, often due to low annealing stringency or enzyme activity at low temperatures [8] [23].

Solution:

- Employ a hot-start DNA polymerase: This prevents polymerase activity during reaction setup at low temperatures, drastically reducing non-specific products and primer-dimer formation [8] [45].

- Optimize reaction conditions:

- Increase annealing temperature: Use a gradient thermal cycler to find the optimal temperature, typically 3–5°C below the primer Tm [8] [46].

- Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration: Excess Mg²⁺ can reduce specificity. Titrate Mg²⁺ in 0.2–1.0 mM increments [8] [46].

- Lower primer concentration: High primer concentrations promote mispriming. Optimize within 0.1–1 µM [8] [10].

- Use specificity-enhancing additives:

- Formamide (1-5%) can increase stringency by lowering the Tm, promoting specific primer binding [41].

- Tetramethylammonium chloride (TMAC; 15-100 mM) is particularly useful with degenerate primers, as it increases hybridization specificity [41] [42].

- Betaine can also help by reducing non-specific amplification [41].

I suspect my sample contains PCR inhibitors. What can I do?

Inhibitors can be carried over from sample preparation (e.g., phenol, EDTA, heparin, or humic acids) and directly inhibit DNA polymerases [8] [23].

Solution:

- Purify the template DNA: Re-purify the sample using alcohol precipitation, drop dialysis, or a commercial PCR cleanup kit [8] [46].

- Use a robust DNA polymerase: Select polymerases known for high tolerance to common inhibitors found in blood, soil, or plant tissues [8].

- Add Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA): BSA (0.1 - 1.0 µg/µL) is highly effective at binding a wide range of inhibitors, preventing them from inactivating the polymerase [41] [44] [42]. It is a standard additive for amplifying templates from environmental or complex biological samples.

How can I increase the yield of a long or difficult PCR product?

Amplification of long targets (>5 kb) or those with complex secondary structures is inefficient with standard protocols.

Solution:

- Use a polymerase mix: Employ a blend of a non-proofreading polymerase (e.g., Taq) and a proofreading polymerase (e.g., Pfu). This combination enhances processivity and corrects misincorporations that halt elongation [45].

- Apply PCR enhancer cocktails: Use a mixture of optimized additives. A classic cocktail for difficult templates includes Betaine, DMSO, and 7-deaza-dGTP [43].

- Adjust cycling conditions:

Experimental Protocols

Basic PCR Protocol with Additives

This is a standard method for setting up a 50 µL PCR reaction, adaptable for the inclusion of additives [24].

- Thaw and mix all reagents thoroughly on ice. Assemble reactions in sterile, nuclease-free tubes.

- Prepare a Master Mix when setting up multiple reactions to minimize pipetting error and ensure consistency.

- Add reagents in the following order:

- Sterile Nuclease-Free Water (Q.S. to 50 µL)

- 10X PCR Buffer (5 µL)

- dNTPs (10 mM each) (1 µL)

- Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂, 25 mM) (variable, e.g., 0-8 µL) [Note: Omit if already in buffer] [24]

- PCR Additive(s) (e.g., DMSO, Betaine, BSA) [See Table 1 for volumes] [24]

- Forward Primer (20 µM) (1 µL)

- Reverse Primer (20 µM) (1 µL)

- DNA Template (variable, e.g., 1-1000 ng)

- DNA Polymerase (0.5-2.5 U) (e.g., 0.5 µL)

- Gently mix the reaction by pipetting up and down. Briefly centrifuge to collect all liquid.

- Transfer tubes to a thermal cycler and start the appropriate program.

Protocol: Optimizing Amplification of GC-Rich Templates

This protocol provides a specific framework for challenging GC-rich targets [41] [44] [43].

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare the Basic PCR Master Mix as above.

- Include 1 M Betaine (final concentration).

- Include 5% DMSO (final concentration).

- Include 0.8 µg/µL BSA (final concentration).

- Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 2-5 minutes.

- 35-40 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 98°C for 20-30 seconds.

- Annealing: Temperature gradient from 55°C to 65°C for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1-2 minutes per kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C.

- Analysis:

- Analyze 5-10 µL of the PCR product by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Based on the results, fine-tune the additive concentrations and annealing temperature.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for PCR Optimization with Difficult Templates

| Reagent Category | Specific Example(s) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerases | Hot-Start Taq, Q5 High-Fidelity, Polymerase Blends (e.g., Taq + Pfu) | Provides specific amplification, high fidelity, or efficient long-range amplification [8] [46] [45]. |

| Essential Cofactor | Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) or Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO₄) | Absolute requirement for DNA polymerase activity; concentration critically affects yield and specificity [41] [8]. |

| Additives for GC-Rich DNA | Betaine, DMSO | Destabilizes secondary structures, promotes uniform DNA melting [41] [43]. |

| Additives for Specificity | Formamide, TMAC | Increases stringency of primer annealing, reduces mispriming [41] [42]. |

| Inhibitor Neutralizers | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Binds to and neutralizes a wide array of PCR inhibitors [41] [44]. |

| Specialized Kits | GC Enhancer Kits, Long-Range PCR Kits | Proprietary, pre-optimized formulations for specific challenging applications [8] [43]. |

Primer Design Fundamentals

Proper primer design is the foundation of successful Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), especially when working with challenging templates or under optimized conditions for inhibitor research. Adherence to core thermodynamic and structural rules ensures specific amplification, high yield, and reliable results for downstream applications [47] [28].

The table below summarizes the critical parameters for effective primer design.

| Design Parameter | Optimal Value or Characteristic | Rationale & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length [47] [48] | 18–25 nucleotides | Balances specificity (long enough) and efficient binding (short enough). |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) [47] [28] | 55–65°C; forward & reverse primers within 1–2°C | Ensures both primers anneal to the template simultaneously and efficiently. |

| GC Content [47] [48] | 40–60% | Provides stable primer-template binding without promoting secondary structures. |

| 3'-End Stability (GC Clamp) [47] [24] | Presence of G or C bases; avoid >3 G/C in last 5 bases | Strengthens the critical initiation point for polymerase while preventing non-specific binding. |