Optimizing Microbial Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Comparison of Bacterial and Fungal DNA Sampling Methods

This article provides a systematic evaluation of DNA extraction methods for bacterial and fungal pathogens, crucial for molecular diagnostics in sepsis and microbiome research.

Optimizing Microbial Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Comparison of Bacterial and Fungal DNA Sampling Methods

Abstract

This article provides a systematic evaluation of DNA extraction methods for bacterial and fungal pathogens, crucial for molecular diagnostics in sepsis and microbiome research. It addresses foundational principles of cell lysis, applies methodologies to diverse clinical samples like blood, stool, and lung tissue, troubleshoots common issues of inhibition and bias, and delivers comparative performance data. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current evidence to guide method selection for accurate pathogen detection and microbial community analysis, ultimately impacting patient outcomes and therapeutic development.

Core Principles and Challenges in Microbial DNA Isolation

The cell wall serves as the primary interface between a microbial cell and its environment, providing critical functions including structural integrity, determination of cell shape, and protection from osmotic lysis. For researchers working with microbial DNA, the cell wall represents the first and most significant barrier to efficient nucleic acid extraction. Its composition varies dramatically across major microbial groups—Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, and Fungi—each possessing a unique architectural blueprint that necessitates specific lysis strategies. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these cell wall structures and presents the experimental data and methodologies essential for optimizing DNA yield and purity in downstream applications such as PCR and next-generation sequencing.

Architectural Blueprints: A Structural Comparison

The fundamental differences in cell wall composition and organization across these microbial groups directly influence the mechanical and chemical lysis requirements for effective DNA release. The following section breaks down these key structural variations.

Bacterial Cell Walls: Gram-Positive vs. Gram-Negative

Most bacteria are classified by their Gram-staining characteristics, a direct reflection of their cell wall architecture [1] [2].

Gram-Positive Bacteria: These organisms possess a thick, multilayered peptidoglycan shell (15-80 nm), which can constitute up to 90% of the cell wall dry weight [1] [3]. Embedded within this peptidoglycan matrix are teichoic and lipoteichoic acids, which contribute to the net negative charge of the cell and overall wall rigidity [1] [4]. They lack an outer membrane.

Gram-Negative Bacteria: Their cell wall is a more complex, double-layered structure [3]. It features a thin, single layer of peptidoglycan (about 10 nm thick, representing only 5-10% of the wall) and a unique outer membrane exterior to it [1] [3]. This outer membrane is studded with lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which act as potent endotoxins, and porins, which control the passage of molecules [1] [4]. The space between the inner and outer membranes is known as the periplasm.

Table 1: Comparative Summary of Bacterial Cell Wall Structures

| Characteristic | Gram-Positive Bacteria | Gram-Negative Bacteria |

|---|---|---|

| Gram Stain Reaction | Purple | Pink [3] |

| Peptidoglycan Layer | Thick (15-80 nm), multi-layered | Thin (10 nm), single-layered [3] |

| Outer Membrane | Absent | Present [3] [2] |

| Teichoic Acids | Present | Absent [3] [4] |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Absent | Present (Endotoxin) [1] [3] |

| Lipid Content | Low (2-5%) | High (15-20%) [3] |

| Porins | Absent | Present [1] [3] |

| Periplasmic Space | Small | Large [3] |

The Fungal Cell Wall: A Complex Carbohydrate Scaffold

Fungal cell walls are dynamic organelles composed primarily of polysaccharides, distinctly different from bacterial counterparts and absent in human hosts, making them excellent targets for antifungal therapy [5] [6].

- Core Skeleton: The inner wall is a conserved, load-bearing scaffold. In yeasts like Candida albicans, it consists of a chitin matrix linked to β-(1,3)-glucan and β-(1,6)-glucan, which in turn connects to cell wall proteins [6]. In filamentous fungi like Aspergillus fumigatus, β-(1,6)-glucan is absent, and the core is a branched β-(1,3)-glucan and chitin network [5] [6].

- Outer Layer and Variability: The outer layers are highly variable. In Candida and Saccharomyces, it is composed of highly mannosylated glycoproteins [5]. In pathogens like Histoplasma capsulatum and Cryptococcus neoformans, an outer layer of α-(1,3)-glucan or a massive capsule of glucuronoxylomannan (GXM), respectively, helps shield immunogenic inner wall components from host detection [5].

Table 2: Key Components of Model Fungal Pathogens' Cell Walls

| Fungal Species | Core Structural Scaffold | Key Linking Polysaccharide | Outer Layer/Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans | β-(1,3)-glucan, Chitin | β-(1,6)-glucan [6] | Mannoproteins [5] |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | β-(1,3)-glucan, Chitin | Galactomannan [5] | Rodlet layer (Hydrophobins), Galactosaminoglycan [5] |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | β-(1,3)-glucan, Chitin | α-(1,3)-glucan [5] | Gelatinous Capsule (GXM) [5] |

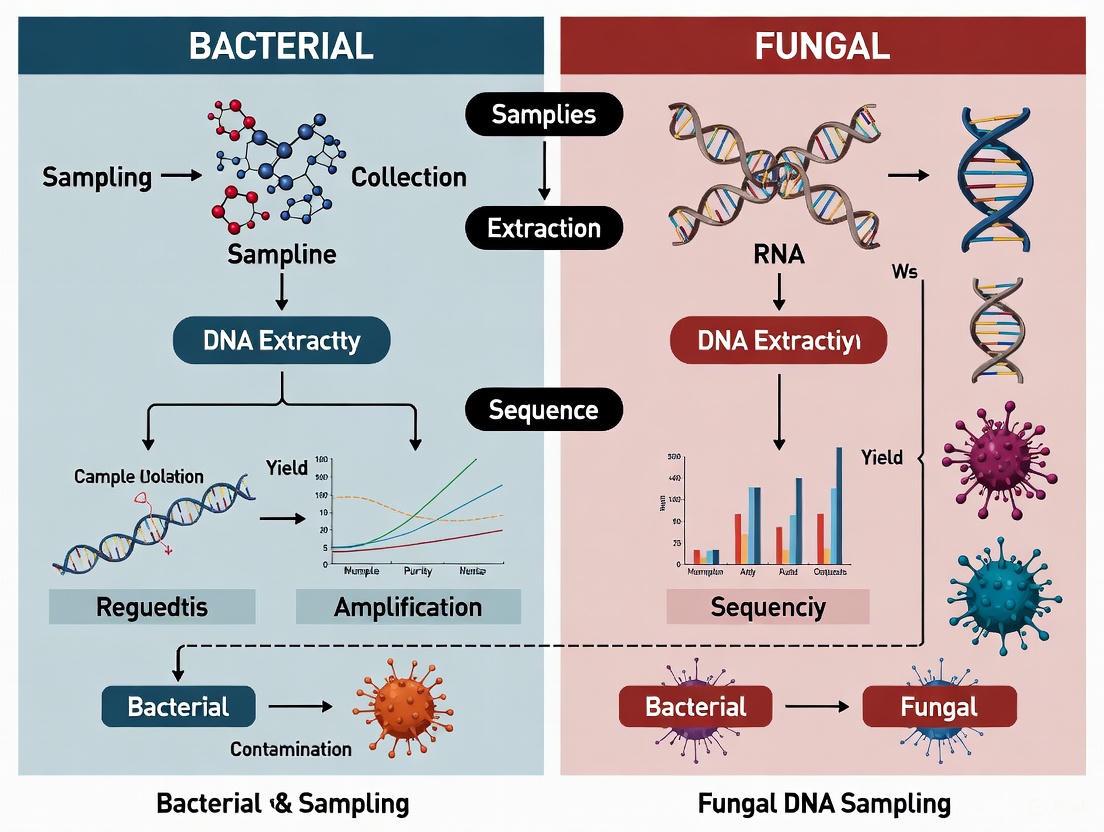

The following diagram synthesizes the structural components of these cell walls and the sequential barriers they present to DNA extraction, logically leading to the lysis strategies required.

Impact on DNA Extraction: Experimental Evidence and Protocols

The structural differences detailed above have a direct and quantifiable impact on the efficiency of DNA extraction, influencing yield, purity, and the relative abundance of taxa in metagenomic studies.

Key Experimental Findings

Research systematically comparing DNA extraction methods across microbial groups highlights the critical role of cell wall structure.

- Differential Lysis Efficiency: A study aiming to optimize DNA isolation from sepsis-causing pathogens demonstrated that a multi-step lysis procedure was necessary to handle the diversity of cell walls from Gram-negative (E. coli), Gram-positive (S. aureus), and fungal (C. albicans, A. fumigatus) organisms [7] [8]. The developed protocol sequentially employed mechanical disruption (with glass beads), chemical lysis, and thermal lysis to achieve sufficient DNA yield for all groups [7].

- Bias in Gram-Positive DNA Recovery: A 2024 meta-taxonomic study that included a mock community of known composition found that the efficiency of extracting DNA from Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., A. halotolerans) versus Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., I. halotolerans) varied significantly with the DNA extraction kit used [9]. The ratio of Gram-negative to Gram-positive ASV abundances was consistently lowest with the QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (QBT), indicating its superior efficiency in lysing the robust Gram-positive cell wall under the tested conditions [9].

- Kit Performance is Sample-Type Dependent: The same 2024 study concluded that no single DNA extraction kit performed best across all sample matrices (e.g., soil, feces, invertebrates) [9]. However, the NucleoSpin Soil kit (MNS) was associated with the highest alpha diversity estimates and made the highest contribution to overall sample diversity, making it a robust choice for complex environmental samples [9].

Table 3: Summary of Experimental Data from DNA Extraction Comparisons

| Experimental Focus | Key Finding | Implication for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Sepsis Pathogen DNA Isolation [7] [8] | A triple-step lysis (mechanical, chemical, thermal) was required for effective DNA release from all four microbial groups. | Protocols for samples containing mixed microbiology must employ sequential, complementary lysis methods. |

| Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative Lysis [9] | The QBT kit yielded a lower Gram-negative/Gram-positive ASV ratio (0.71) vs. other kits (~1.35-1.40), indicating better Gram-positive lysis. | The choice of kit can introduce bias; select kits with proven efficiency for your target microbes. |

| Kit Performance Across Ecosystems [9] | The NucleoSpin Soil kit (MNS) provided the most consistent and highest diversity estimates across terrestrial ecosystem samples. | For studies involving multiple sample types (e.g., soil, feces), a single, well-validated kit like MNS can minimize technical variation. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Isolation of Microbial DNA from Blood

The following is a summarized protocol based on the methodology from Kaczorowski et al. (2014), which was designed to handle the tough cell walls of diverse pathogens [7] [8]. This serves as a model for a rigorous, multi-step lysis procedure.

Objective: To isolate microbial DNA from blood samples spiked with representative pathogens (e.g., E. coli, S. aureus, C. albicans, A. fumigatus).

Sample Pre-processing:

- Erythrocyte Lysis: Treat 1.5 mL of blood with 0.17 M ammonium chloride solution to lyse red blood cells. This critical step reduces heme concentration, a potent PCR inhibitor, in the final DNA extract [7].

Microbial Cell Lysis (Core Steps):

- Mechanical Disruption: Resuspend the pellet in a lysis buffer containing glass beads (ϕ 710–1,180 μm) and disrupt cells using a homogenizer (e.g., FastPrep machine). This step is crucial for breaking the rigid walls of fungi and Gram-positive bacteria [7].

- Enzymatic Lysis: Incubate the sample with an enzyme cocktail at 37°C. A typical cocktail includes:

- Lysozyme (2 mg/mL): Targets the peptidoglycan layer of Gram-positive bacteria.

- Lysostaphin (0.2 mg/mL): Specifically degrades the peptidoglycan of Staphylococcus species.

- Lyticase (40 U): Degrades the β-glucan cell walls of fungi like C. albicans [7].

- Chemical & Thermal Lysis: Subject the sample to a chemical agent like 50 mM NaOH and incubate at 95°C. This step denatures proteins and disrupts membranes, ensuring complete lysis [7].

DNA Purification:

- Following the multi-step lysis, purify the DNA using a commercial kit (e.g., GeneMATRIX Quick Blood DNA Purification Kit, QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit) according to the manufacturer's protocol, which typically involves binding DNA to a silica membrane, washing, and elution [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Cell Wall Lysis

Successfully navigating the diverse defense mechanisms of microbial cell walls requires a strategic selection of reagents and kits. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Cell Lysis

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Target | Specific Application |

|---|---|---|

| Lysozyme [7] | Enzyme that hydrolyzes β-(1,4) linkages between N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) in peptidoglycan. | Primary lysis of Gram-positive bacterial cell walls; also active against Gram-negative bacteria after pretreatment. |

| Lysostaphin [7] | A glycyl-glycine endopeptidase that cleaves the pentaglycine cross-bridges in the peptidoglycan of Staphylococcus species. | Highly specific and efficient lysis of Staphylococci, including S. aureus. |

| Lyticase [7] | Enzyme complex with β-(1,3)-glucanase activity, degrading the primary structural polysaccharide of yeast cell walls. | Lysis of yeast cells (e.g., Candida albicans). |

| Glass Beads (710-1180 μm) [7] | Inert beads used in conjunction with vigorous shaking or vortexing to physically disrupt robust cell walls by abrasive force. | Mechanical disruption of fungal hyphae, spores, and Gram-positive bacterial clusters. |

| NucleoSpin Soil Kit (MNS) [9] | Commercial DNA extraction kit optimized for samples rich in PCR inhibitors (humic acids) and difficult-to-lyse microorganisms. | Recommended for diverse sample types (soil, feces, invertebrates) to maximize microbial diversity recovery. |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QBT) [9] | Commercial DNA extraction kit commonly used for tissue and blood samples; often includes proteinase K for digestion. | Effective for Gram-positive bacteria, as indicated by its high lysis efficiency for A. halotolerans in mock communities [9]. |

The structural dichotomy of microbial cell walls is not merely a taxonomic distinction but a fundamental factor that dictates experimental success in DNA-based research. The thick, sugar-based armor of Gram-positive bacteria, the complex double-membrane system of Gram-negatives, and the chitin-glucan scaffold of fungi each present unique challenges. As experimental data confirms, a one-size-fits-all approach to cell lysis leads to biased results and suboptimal DNA yields. A deep understanding of these cellular architectures empowers researchers to make informed decisions—selecting appropriate mechanical, chemical, and enzymatic lysis strategies and commercial kits—to ensure efficient, unbiased, and high-quality DNA recovery for advanced genomic applications.

The accuracy of microbial community analysis in various human body sites is critically dependent on the choice of sampling method and DNA extraction technique. In molecular microbiology, the optimal protocol for one sample type often performs poorly for another, creating significant challenges for researchers and clinicians aiming for reproducible, reliable results. This guide objectively compares sampling and extraction methodologies across four complex sample matrices—whole blood, stool, lung tissue, and swab-collected samples—by synthesizing current experimental evidence. The findings presented herein support a broader thesis in bacterial and fungal DNA research: that method standardization must be sample-specific to overcome the unique compositional challenges of each material.

Comparative Performance of Sampling and Extraction Methods

Whole Blood: Magnetic Bead-Based Automation Excels

Blood presents unique challenges for molecular detection of pathogens due to its low bacterial biomass and high concentration of PCR inhibitors like human DNA and hemoglobin. A 2025 study compared one column-based method (QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit) with two magnetic bead-based methods (K-SL DNA Extraction Kit and GraBon automated system) for detecting sepsis-causing pathogens in clinical whole blood samples [10].

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods for Whole Blood Samples

| Extraction Method | Technology | Accuracy for E. coli | Accuracy for S. aureus | Specificity | Sample Input/Elution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | Column-based | 65.0% (12/40) | 67.5% (14/40) | 100% | 200 µL / 200 µL |

| K-SL DNA Extraction Kit | Magnetic bead-based | 77.5% (22/40) | 67.5% (14/40) | 100% | 200 µL / 100 µL |

| GraBon System | Automated magnetic bead | 76.5% (21/40) | 77.5% (22/40) | 100% | 500 µL / 100 µL |

The magnetic bead-based methods demonstrated significantly higher accuracy for E. coli detection compared to the column-based method (p = 0.031 and p = 0.022, respectively) [10]. The superior performance of magnetic bead-based systems, particularly the GraBon automated platform, is attributed to their ability to isolate bacteria from whole blood before lysis, providing a cleaner sample for DNA extraction. Additionally, GraBon's unique motor-driven rotating tip enables more effective disruption of the tough peptidoglycan cell wall of Gram-positive S. aureus, explaining its superior performance with this pathogen [10].

For rapid bacterial separation from blood prior to DNA extraction, a 2025 study compared centrifugation, chemical lysis (Polaris), and enzymatic digestion (MolYsis) methods. Centrifugation achieved the lowest Ct values in qPCR detection, indicating highest bacterial recovery, and most efficient depletion of host DNA, making it a fast, robust, and cost-effective method for molecular diagnostics of bloodstream infections [11].

Stool Samples: Consistent Profiles Across Kits

Stool represents a high-biomass sample with its own challenges, including diverse microbial communities and potential PCR inhibitors. A 2023 comparison of four commercial DNA extraction kits for stool samples found that despite differences in DNA quality and quantity, all kits yielded similar diversity and compositional profiles for stool samples [12].

Table 2: DNA Extraction Kits for Stool Samples

| Extraction Kit | Mechanical Lysis | Enzymatic Lysis | Chemical Lysis | DNA Binding | Performance on Stool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | Yes (Bead-beating) | No | Yes | Silica membrane columns | Effective, similar profiles |

| Macherey Nucleospin Soil | Yes (Bead-beating) | No | Yes | Silica membrane columns | Effective, similar profiles |

| Macherey Nucleospin Tissue | No | Yes (Proteinase K) | Yes | Silica membrane columns | Effective, similar profiles |

| MagnaPure LC DNA Isolation Kit III | No | Yes (Proteinase K) | Yes | Magnetic beads | Effective, similar profiles |

The critical differentiator among kits was their effectiveness on low-biomass samples (chyme, bronchoalveolar lavage, and sputum), for which all kits showed insufficient sensitivity [12]. This highlights that while stool sampling is relatively forgiving, the same methods cannot be universally applied to low-biomass samples.

Lung Tissue: Superior to BAL Fluid in Murine Studies

Low-biomass samples like lung tissue present significant challenges due to vulnerability to contamination and sequencing stochasticity. A 2021 study compared homogenized whole lung tissue versus bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid for characterizing murine lung microbiota [13].

Table 3: Murine Lung Sampling Method Comparison

| Parameter | Whole Lung Tissue | BAL Fluid |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial DNA quantity | Greater | Lesser |

| Community composition | Distinct, biologically plausible | Minimal difference from controls |

| Sample-to-sample variation | Decreased | Increased |

| Vulnerability to contamination | Lower | Higher |

| Comparison to source communities | Greater biological plausibility | Minimal differentiation |

The study concluded that whole lung tissue contained greater bacterial signal and less evidence of contamination than BAL fluid, making it the preferred specimen type for murine lung microbiome studies [13]. This finding is particularly important given the anatomical limitations of murine models, where BAL fluid collection is severely limited by the small volume of murine lungs (~1 mL) [13].

Swab Sampling: Material and Solution Optimization

Swabbing is a common sampling technique for surfaces and skin, but efficiency varies considerably by swab material and moistening solution. A 2021 study compared bacterial DNA recovery from four swab types using Proteus mirabilis as a representative bacterium [14].

Swab Type and DNA Yield Comparison

Flocked swabs outperformed all other types with approximately 1240 ng of DNA recovery, compared to 184 ng for cotton swabs, 533 ng for dental applicators, and 430 ng for dissolvable swabs [14]. In surface sampling experiments, flocked swabs consistently outperformed cotton swabs across wood, glass, and tile surfaces, though they showed decreased recovery from plastic [14].

A 2025 pilot study on sensitive facial skin found that traditional swabbing consistently failed to recover detectable microbial DNA, while gentle scraping with a sterile No. 10 surgical blade yielded sufficient DNA for both bacterial and fungal sequencing [15]. This demonstrates that for low-biomass skin samples, scraping may be necessary to overcome the limitations of swabbing.

The optimal swabbing solution also affects recovery. A 2019 study found that a solution of 1% Tween20 + 1% glycerol in PBS (TG) showed the highest bacterial recovery rates for both E. coli and S. aureus compared to PBS alone or commercial GS solution [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Magnetic Bead-Based DNA Extraction from Whole Blood

The superior-performing GraBon system utilizes the following protocol [10]:

- Bacterial Separation: Magnetic beads isolate bacteria from 500 µL of whole blood before lysis

- Cell Lysis: Utilizes a motor-driven rotating plastic tip for vigorous vortexing, particularly effective for Gram-positive bacteria

- DNA Binding: Magnetic beads bind DNA in the presence of chaotropic salts

- Washing: Multiple wash steps remove PCR inhibitors including hemoglobin and human DNA

- Elution: DNA is eluted in 100 µL elution buffer, concentrating the original sample

This protocol's key advantage is the initial separation of bacteria from blood components, reducing co-extraction of PCR inhibitors [10].

Skin Scraping Protocol for Low-Biomass Samples

For sensitive facial skin where swabbing fails, the following scraping protocol has proven effective [15]:

- Patient Preparation: Participants avoid topical products for 24 hours and wash with plain water only

- Skin Stabilization: One hand gently stretches and stabilizes the skin above the target area

- Scraping Technique: A No. 10 sterile surgical blade held at 15-30° angle, using the curved portion (not the tip) to gently scrape with light, controlled pressure

- Sample Collection: Superficial stratum corneum fragments are transferred to a pre-moistened sterile cotton swab

- Preservation: Swab heads are placed in sterile 15 mL Falcon tubes containing 3 mL of PBS for DNA preservation

This method is well-tolerated even by patients with sensitive skin and yields sufficient DNA for both bacterial and fungal analysis [15].

Centrifugation-Based Bacterial Separation from Blood

For rapid bacterial separation prior to DNA extraction [11]:

- First Centrifugation: Spiked blood in serum collection tube centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 minutes

- Supernatant Collection: Supernatant collected without disturbing the middle layer

- Second Centrifugation: Supernatant centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 minutes

- Pellet Resuspension: Supernatant discarded, pellet resuspended in 200 μL of sterile PBS

- DNA Isolation: Standard DNA isolation performed on the resuspended pellet

This method achieves efficient host DNA depletion and high bacterial recovery in a cost-effective, rapid manner suitable for diagnostic applications [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Microbial DNA Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, K-SL DNA Extraction Kit, QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | Isolation of microbial DNA from various sample matrices using different technologies |

| Lysis Components | Proteinase K, Bead-beating matrices, Chaotropic buffers, Lysozyme | Cellular disruption and nucleic acid release, tailored to different cell wall types |

| Separation Technologies | Magnetic beads, Silica membranes, Centrifugation methods | Selective binding and purification of nucleic acids from complex samples |

| Sampling Materials | Flocked swabs, Cotton swabs, Sterile surgical blades (No. 10), Dissolvable swabs | Collection of microbial biomass from surfaces, skin, and tissues |

| Swabbing Solutions | PBS, 1% Tween20 + 1% glycerol in PBS (TG), Commercial GS solution | Enhancement of microbial recovery during swabbing procedures |

| Inhibition Removal | DNase treatments, Wash buffers, Host depletion techniques | Reduction of PCR inhibitors and host DNA background |

The experimental data comprehensively demonstrate that optimal sampling and DNA extraction methods must be carefully matched to specific sample types to ensure accurate microbial characterization. Magnetic bead-based automated systems outperform traditional column-based methods for whole blood. Flocked swabs and appropriate solutions maximize recovery from surfaces, while scraping may be necessary for low-biomass skin sites. For murine lung studies, whole tissue homogenates provide more reliable data than BAL fluid. Stool samples show more consistent results across methods but still require careful selection for low-abundance targets. These findings underscore the critical importance of validating methods for each specific sample matrix rather than applying universal protocols across diverse sample types.

The accurate characterization of microbial communities is paramount across biomedical research, drug development, and clinical diagnostics. However, the representation of these communities in study results is profoundly influenced by technical decisions made throughout the experimental workflow. Even with advanced sequencing technologies, methodological variations can introduce significant bias, potentially obscuring true biological signals and leading to misleading conclusions. This guide objectively compares key methodological alternatives in bacterial and fungal DNA sampling research, synthesizing experimental data to highlight how choices in sample collection, DNA extraction, and library preparation impact microbial community representation. By examining comparative performance data, we aim to provide researchers with evidence-based guidance for minimizing technical bias in microbiome studies.

Sample Collection and Storage: The First Critical Step

The initial handling of samples immediately upon collection sets the stage for all downstream analyses. Decisions made at this stage can preserve the native microbial community or introduce significant compositional shifts.

Experimental Evidence from Comparative Studies

Study 1: Wild Mammal (Bat) Microbiome Sampling A 2018 study directly compared guano (feces) and distal intestinal mucosa samples from 19 species of wild bats in Belize to determine if these common sampling methods were interchangeable [17].

- Methodology: Researchers collected both guano and distal intestinal mucosa from each specimen. Microbial DNA was extracted using the MO BIO PowerLyzer PowerSoil DNA Isolation kit with mechanical disruption. 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing was then used to compare the resulting microbial communities [17].

- Key Finding: The diversity and composition of intestine and guano samples differed substantially. Intestinal mucosal samples retained a stronger signal of host evolution, while fecal samples more strongly reflected host diet [17]. This indicates that the choice of sample type should align with the specific biological question.

Study 2: Human Fecal Sample Storage Conditions A 2023 study systematically compared storage methods for human fecal samples to address logistical challenges in large-scale studies [18].

- Methodology: Human fecal aliquots were subjected to different storage conditions: immediate freezing at -80°C (standard), storage at room temperature (RT) for 3-5 days without preservation, and storage at RT for 3-5 days in two commercial stabilization buffers (OMNIgene·GUT and Zymo Research). Microbiota composition was analyzed via 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing [18].

- Key Finding: While immediate freezing remains the gold standard, stabilization systems effectively limited the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae compared to unpreserved samples stored at room temperature. Samples stored in stabilization buffers at RT showed a limited bias compared to immediately frozen samples, presenting a viable alternative when cold-chain logistics are prohibitive [18].

Comparative Data on Storage Methods

Table 1: Impact of Sample Collection and Storage Methods on Microbial Community Composition

| Sample Type / Storage Method | Key Effect on Microbial Community | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Intestinal Mucosa (Bat study) [17] | Records stronger phylogenetic signal of host evolutionary history. | Studies of host evolution, host-microbe interactions, and mucosal immunology. |

| Feces/Guano (Bat study) [17] | Records stronger signal of host diet and environmental influx. | Nutritional ecology, dietary interventions, and large-scale observational studies. |

| Immediate Freezing (-80°C) (Human study) [18] | Considered the gold standard; minimizes compositional shifts post-collection. | Ideal for most studies where cold-chain logistics are feasible. |

| Stabilization Buffer + RT (e.g., OMNIgene·GUT, Zymo) (Human study) [18] | Limits overgrowth of specific taxa (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae); introduces limited bias vs. frozen. | Large-scale or remote studies where immediate freezing is logistically challenging. |

| Unpreserved at Room Temperature (Human study) [18] | Leads to significant compositional shifts, including overgrowth of certain bacteria. | Not recommended; introduces substantial bias. |

Nucleic Acid Extraction: A Major Source of Bias

The method used to extract DNA is consistently identified as one of the most significant variables affecting microbiome profiling results. The efficiency of cell lysis, particularly for tough-to-lyse organisms, varies dramatically between protocols.

Mechanical vs. Enzymatic Lysis

Study 1: Comprehensive Workflow Comparison (2023) This study highlighted cell disruption as a major contributor to variation in microbiota composition [18].

- Methodology: Researchers compared mechanical disruption (repeated bead-beating with zirconia/silica beads) to enzymatic lysis (using lysis buffer and Proteinase K with heat) for DNA extraction from human fecal samples [18].

- Key Finding: Mechanical disruption via bead-beating was superior to enzymatic lysis for achieving representative community profiles. Bead-beating is more effective at breaking open the tough cell walls of Gram-positive bacteria and fungal spores, preventing their under-representation [18].

Study 2: Fungal DNA Extraction Method Comparison A 2005 study quantitatively compared six DNA extraction methods for recovering DNA from the fungal pathogens Aspergillus fumigatus (filamentous fungus) and Candida albicans (yeast) [19].

- Methodology: Known quantities of A. fumigatus conidia/hyphae and C. albicans yeast cells were added to bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and subjected to six different DNA extraction methods. DNA yield was measured using quantitative PCR [19].

- Key Finding: Differences in DNA yields among the methods were highly significant. Methods employing mechanical agitation with beads (e.g., FastDNA kit, UltraClean soil DNA kit) produced the highest yields from A. fumigatus hyphae. In contrast, an enzymatic lysis method worked well for C. albicans but performed poorly for A. fumigatus. The study concluded that no single extraction method was optimal for all organisms [19].

Comparison of DNA Extraction Kits and Methods

Context: Sepsis Diagnostics and Food Safety Studies in clinical and food safety settings further support the impact of extraction choice.

- Magnetic Bead vs. Column-Based Kits: A 2025 study on sepsis diagnostics found that magnetic bead-based DNA extraction methods (K-SL DNA Extraction Kit, GraBon system) demonstrated higher accuracy (77.5% and 76.5%, respectively) for detecting E. coli in whole blood compared to a column-based method (QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, 65.0% accuracy). The magnetic bead methods, which included a bacterial isolation step prior to lysis, provided cleaner samples and reduced PCR inhibition [10].

- In-House vs. Commercial Methods: A 2021 food safety study developed a modified in-house phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol DNA extraction method. When used for detecting Salmonella and Listeria in spiked food samples, this method showed statistically similar sensitivity to commercial kits (Qiagen, Macherey-Nagel) but at a much lower cost, highlighting a cost-effective alternative for certain applications [20].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods Across Studies

| Extraction Method / Technology | Target Microbes | Reported Performance / Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Bead-Beating (e.g., FastDNA kit, PowerSoil kit) | General microbiome, Gram-positive bacteria, Fungi [19] [18] | Superior yield for tough-to-lyse cells; higher recovery of Gram-positive bacteria and fungal hyphae; considered essential for representative community profiles. |

| Enzymatic Lysis (e.g., Proteinase K + Heat) | Gram-negative bacteria, Yeasts [19] [18] | Simpler protocol but can under-represent microbes with robust cell walls (e.g., Gram-positives, fungal spores); lower overall community diversity. |

| Magnetic Bead-Based (e.g., K-SL Kit, GraBon) | Bloodstream pathogens [10] | Higher accuracy reported; reduces PCR inhibitors by isolating bacteria from sample matrix; amenable to automation. |

| Column-Based (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit) | Bloodstream pathogens, Tissue [10] | Established benchmark; but may co-purify inhibitors and show lower sensitivity in complex matrices like whole blood. |

| In-House (Phenol-Chloroform) | Foodborne pathogens [20] | Low-cost; performance comparable to commercial kits for specific applications; requires more hands-on time and hazardous chemicals. |

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Downstream steps following DNA extraction continue to introduce variability, affecting the sensitivity and specificity of microbial community detection.

PCR Cycle Number and Input DNA

The 2023 workflow comparison study also investigated parameters during the library preparation phase [18].

- Methodology: The study tested different input DNA amounts and the number of PCR cycles during the amplification step prior to sequencing.

- Key Finding: Using a high number of PCR cycles (e.g., 35) led to a marked increase in contaminants detected in the negative controls. The study suggested using approximately 125 pg input DNA and 25 PCR cycles as optimal parameters to reduce the effect of contaminants and improve the signal-to-noise ratio in fecal microbiota profiling [18].

Batch Effects

The same study investigated batch effects by processing 139 replicate positive controls (a mixed sample from multiple participants) across different DNA extraction rounds and sequencing runs [18].

- Finding: While no significant batch effect was observed between replicate sequencing runs, the specific Illumina barcode used during library preparation did have a small but significant impact on the observed microbial composition. This highlights an often-overlooked technical factor that should be considered in experimental design, for example, by randomizing samples across barcodes [18].

The following diagram summarizes the key stages of a typical microbiome study and pinpoints where the biases discussed in this guide are introduced.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Based on the experimental protocols cited, the following table details key reagents and materials critical for minimizing bias in microbial community studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Sampling Methods

| Item | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Stabilization Buffers | OMNIgene·GUT (DNA Genotek), Zymo Research DNA/RNA Shield [18] | Preserves microbial community DNA/RNA at room temperature by inhibiting nuclease activity and microbial growth; crucial for field studies and unreliable cold chains. |

| Bead-Beating Tubes | Tubes with Zirconia/Silica Beads (0.1 mm & 2.7 mm) [18] | Essential for mechanical cell disruption. The variation in bead sizes ensures efficient lysis of diverse microbes, including tough Gram-positive bacteria and fungal cells. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | MO BIO PowerSoil PowerLyzer DNA Isolation Kit [17], FastDNA Kit [19], DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit [20] | Standardized protocols for DNA purification. Kits optimized for soil/stool (e.g., PowerSoil) are often most effective for complex microbial communities due to robust inhibitor removal. |

| Lysis Buffers | S.T.A.R. Buffer [18], Lysis Buffer (Promega) with Proteinase K [18] | Chemical solutions designed to break down cell membranes and release nucleic acids, often used in conjunction with mechanical disruption. |

| Magnetic Bead Systems | K-SL DNA Extraction Kit, GraBon Automated System [10] | Enable purification and concentration of DNA while removing PCR inhibitors; especially useful for complex samples like whole blood. |

| PCR Master Mixes | OneTaq Hot Start Master Mix [20], WarmStart Colorimetric LAMP Master Mix [20] | Pre-mixed solutions containing enzymes, dNTPs, and buffers for DNA amplification. Hot-start enzymes improve specificity, reducing non-specific amplification and bias. |

The accurate representation of microbial communities is threatened by technical bias at every stage of the research workflow. Evidence consistently shows that the choice of sample type (e.g., mucosa vs. feces) captures different biological signals, while storage conditions can either preserve or distort community integrity. The DNA extraction method, particularly the use of mechanical bead-beating, is arguably the most critical factor for ensuring equitable lysis across diverse taxa. Finally, downstream parameters like PCR cycle number and even the choice of sequencing barcodes can introduce variability. There is no one-size-fits-all protocol; the optimal method depends on the sample type, target microorganisms, and research question. However, adherence to standardized, well-validated workflows that incorporate mechanical lysis and controlled library preparation, along with the inclusion of appropriate positive and negative controls, is fundamental for generating reliable and comparable data in microbial ecology.

Choosing an effective cell lysis method is a critical first step in molecular analysis, directly impacting the yield, quality, and reliability of downstream results. This guide provides a comparative analysis of mechanical and non-mechanical lysis techniques, supported by recent experimental data, to inform method selection for bacterial and fungal DNA sampling in research and drug development.

Cell lysis, the process of disrupting the cellular membrane to release intracellular components such as DNA, RNA, and proteins, is a foundational unit operation in biomolecular analysis [21]. The global market for cell lysis reflects its importance, having been valued at 2.35 billion U.S. dollars in 2016 [21]. The choice of lysis method is influenced by the target molecules, the type of cell (e.g., gram-positive bacteria, gram-negative bacteria, fungi), and the desired quality of the final product [21]. Methods are broadly classified into two categories: mechanical lysis, which uses physical force to break the cell membrane, and non-mechanical lysis, which employs chemical detergents or enzymes [22].

The structural differences between cell types are a primary consideration for selecting a lysis method. For instance, gram-positive bacteria possess a thick peptidoglycan cell wall that shows greater resistance to lysis than the thinner, multi-layered envelope of gram-negative bacteria like E. coli [10] [21]. Fungal cells present an even greater challenge due to their complex and diverse cell wall structures, which make finding a universal lysis method difficult [23].

◥ Comparative Performance of Lysis Methods

Recent comparative studies highlight how the choice of lysis method directly affects diagnostic accuracy and DNA recovery across different sample types and pathogens.

▍ Bacterial DNA Extraction from Whole Blood

A 2025 study compared DNA extraction methods for detecting sepsis-causing pathogens in clinical whole blood samples, a complex matrix containing numerous PCR inhibitors [10]. The research evaluated one column-based method and two magnetic bead-based methods.

Table 1: Diagnostic Accuracy for Sepsis Pathogen Detection in Whole Blood [10]

| Extraction Method | Core Lysis Mechanism | E. coli (Gram-negative) Detection Accuracy | S. aureus (Gram-positive) Detection Accuracy | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Column-based) | Chemical lysis directly in whole blood | 65.0% (12/40) | 67.5% (14/40) | 100% |

| K-SL DNA Extraction Kit (Magnetic bead-based) | Bead-based bacterial isolation + chemical lysis | 77.5% (22/40) | 67.5% (14/40) | 100% |

| GraBon System (Automated magnetic bead) | Bead-based isolation + vigorous mechanical lysis | 76.5% (21/40) | 77.5% (22/40) | 100% |

The magnetic bead-based methods, particularly the automated GraBon system, demonstrated superior performance. The study attributed this to more effective bacterial isolation from PCR inhibitors in blood prior to lysis. Furthermore, the GraBon system's "motor-driven rotating plastic tip for vigorous vortexing" provided a more effective mechanical disruption of the tough peptidoglycan cell wall of S. aureus, explaining its higher accuracy for this gram-positive bacterium [10].

▍ Fungal and Specialized Sample DNA Extraction

The influence of lysis method extends to other sample types and organisms:

- Gut Mycobiota Analysis: A comparative analysis of DNA extraction methods for fecal samples found that incorporating mechanical glass bead lysis significantly influenced results. Methods using bead beating (DNgb and MMgb) were enriched for filamentous fungal species, while methods without this step showed higher relative abundance of yeast fungi. The study concluded that bead beating favored the recovery of DNA more appropriate for fungal community analysis [24].

- Subgingival Biofilm Sampling: A 2025 pilot study comparing DNA extraction kits from single paper points highlighted different lysis approaches. The DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (enzymatic/chemical lysis) demonstrated the highest efficiency. In contrast, the ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit, which uses mechanical lysis by bead beating, required a longer processing time (~120 minutes) and had a higher cost per extraction [25].

- Long-Read Sequencing of Fungi: For long-read sequencing technologies like Oxford Nanopore, DNA integrity is paramount. A 2025 study found that chemical lysis with CTAB/SDS generated DNA from pure fungal cultures with high yields while preserving integrity, making it more suitable than physical methods like bead beating or grinding in liquid nitrogen, which carry a risk of DNA shearing [23].

◥ Experimental Protocols for Lysis Method Evaluation

To ensure reproducible and reliable results, standardized protocols for evaluating lysis methods are essential. The following are detailed methodologies adapted from recent comparative studies.

▍ Protocol 1: Comparative Evaluation of DNA Extraction Kits from Whole Blood

This protocol is adapted from the 2025 study evaluating sepsis diagnostics [10].

- Sample Preparation: Collect whole blood samples. For a controlled study, samples can be spiked with a known concentration of target pathogens (e.g., E. coli, S. aureus). Include negative controls (blood from healthy check-ups) to determine specificity.

- DNA Extraction:

- QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit: Follow the manufacturer's protocol for bacterial DNA from whole blood. This involves chemical lysis directly in the blood matrix.

- Magnetic Bead-Based Kits (K-SL and GraBon): These protocols typically involve a step to isolate bacteria from blood components using magnetic beads before the lysis and DNA purification steps are performed.

- Downstream Analysis: Perform real-time PCR using primers specific to the target pathogens. Quantify the results based on Cycle threshold (Ct) values.

- Data Analysis: Calculate diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy by comparing PCR results to the known status of the samples (spiked vs. negative).

▍ Protocol 2: Optimizing Fungal DNA Extraction for Long-Read Sequencing

This protocol is derived from the 2025 study on fungal DNA extraction [23].

- Lysis Method Comparison:

- Chemical Lysis: Suspend 10 mg of fungal pellet in a CTAB/SDS-based lysis buffer. Incubate at a defined temperature (e.g., 65°C) for a set period.

- Physical Lysis (Bead Beating): Add the fungal pellet to a tube with lysis buffer and sterile glass beads (e.g., 0.5 mm). Agitate on a bead beater at high speed for a specific duration (e.g., 5 minutes).

- Physical Lysis (Grinding): Grind the fungal pellet in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle.

- DNA Purification: For methods involving physical lysis or certain chemical buffers, a purification step using phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol may be necessary, followed by DNA precipitation with isopropanol and washing with ethanol.

- Quality Assessment:

- Quantity and Purity: Measure DNA concentration and assess purity using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop). Target 260/280 ratios of ~1.8 and 260/230 ratios of ~2.0-2.2.

- Integrity: Check DNA integrity by running samples on a 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis alongside a high molecular weight DNA ladder (e.g., 10 kb). Intact DNA should appear as a high molecular weight band.

- Functional Assessment: Perform downstream sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore Technology) and compare metrics like read length and percentage of active pores.

◥ A Guide to Lysis Method Selection

The decision tree below outlines a logical workflow for selecting an appropriate lysis method based on sample and experimental requirements.

◥ The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Lysis Reagents & Kits

The following table details key reagents, kits, and instruments used in the featured experiments, along with their primary functions in the lysis process.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Kits for Cell Lysis

| Item Name | Type/Classification | Primary Function in Lysis |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit [10] | Column-based / Chemical Lysis | Uses detergents to chemically disrupt cells and a silica membrane to bind DNA. |

| K-SL DNA Extraction Kit [10] | Magnetic Bead-based / Mechanical & Chemical | Uses magnetic beads to isolate bacteria, followed by chemical lysis. |

| GraBon System [10] | Automated / Mechanical & Chemical | Employs vigorous mechanical vortexing and magnetic beads for lysis and DNA capture. |

| CTAB/SDS Buffer [23] | Chemical Lysis Buffer | Detergents disrupt cell membranes and walls; CTAB helps separate polysaccharides from DNA. |

| Proteinase K [23] [25] | Enzyme / Enzymatic Lysis | Digests proteins and degrades nucleases, aiding in cell disruption and protecting nucleic acids. |

| Lysozyme [21] [26] | Enzyme / Enzymatic Lysis | Specifically degrades the peptidoglycan cell wall of gram-positive bacteria. |

| BashingBeads [25] | Mechanical Lysis Consumable | Ultra-high density beads for mechanical disruption of cells during vortexing. |

| Enhanced RIPA Lysis Buffer [26] | Chemical Lysis Buffer | A detergent-based buffer effective for tough applications like membrane protein extraction. |

| Phenol/Chloroform/Isoamyl Alcohol [23] | Purification Reagent | Used after initial lysis to separate DNA from proteins and other cellular debris. |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit [25] [24] | Column-based / Enzymatic & Chemical | Utilizes enzymatic (e.g., lysozyme) and chemical lysis for broad cell type applicability. |

Practical Protocols for Diverse Clinical and Environmental Samples

The extraction of high-quality microbial DNA from complex samples is a critical first step in metagenomic studies. This guide compares the performance of the manually-performed THSTI method, which integrates physical, chemical, and mechanical lysis, against other common DNA extraction technologies. Experimental data from direct comparisons demonstrate that this optimized manual workflow achieves superior DNA yield and quality across diverse sample types, including human-derived and environmental samples, making it a robust choice for demanding downstream applications like next-generation sequencing.

In microbiome research, the accuracy of community profiling is heavily influenced by the initial DNA extraction process. Efficient lysis of diverse microbial cells—from easily disrupted Gram-negative bacteria to tough-walled Gram-positive bacteria and fungal spores—without damaging their genetic material, presents a significant challenge. The THSTI method (named for the Translational Health Science and Technology Institute where it was developed) was specifically designed to address this bottleneck by combining multiple lysis modalities in a manual protocol [27] [28] [29].

This guide objectively evaluates the THSTI method against commercial kit-based and automated extraction systems, providing supporting experimental data on yield, purity, and suitability for downstream sequencing to inform researchers in their selection process.

Performance Comparison: THSTI Method vs. Alternative Systems

Direct comparative studies reveal significant differences in the efficiency of various DNA extraction methods. The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from the original THSTI method validation study, which compared it to a commercial kit (Qiagen) and an Automated Liquid Handling System (ALHS, MagNA pure, Roche) [28].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of DNA Yield and Purity Across Sample Types

| Sample Type | Method | Average Nucleic Acid Concentration (ng/μL) | Total Recovery (ng) | 260/280 Purity Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stool | THSTI | 543.3 ± 187.26 | 108,660 ± 37,520 | 1.85 ± 0.06 |

| Kit (Qiagen) | 202.29 ± 105.63 | 20,229.23 ± 10,563 | 1.94 ± 0.23 | |

| ALHS | 113.38 ± 62.26 | 11,338.46 ± 6,226 | 1.67 ± 0.07 | |

| Vaginal Swab | THSTI | 104.77 ± 39.61 | 20,955.38 ± 7,923.13 | 1.69 ± 0.12 |

| Kit (Qiagen) | 8.37 ± 5.66 | 836.15 ± 566.7 | 1.43 ± 0.58 | |

| ALHS | 22.79 ± 9.5 | 2,279.23 ± 906.02 | 2.47 ± 1.01 | |

| Soil | THSTI | 53.16 ± 36.77 | 10,633.84 ± 10,317.18 | 1.48 ± 0.04 |

| Kit (Qiagen) | 66.02 ± 70.13 | 6,602.30 ± 7,014 | 1.16 ± 0.05 | |

| ALHS | 93.91 ± 103.17 | 9,391.53 ± 7,355.84 | 1.44 ± 0.07 |

Key Performance Insights

- Superior Yield: The THSTI method consistently recovered a higher total mass of DNA from most sample types, particularly from complex human-derived samples like stool and vaginal swabs, where it outperformed the kit by 5.4-fold and 25-fold, respectively [28].

- High Molecular Weight DNA: Gel electrophoresis confirmed that the THSTI method reliably produced high molecular weight DNA fragments averaging ~20 kilobases, which is preferable for shotgun metagenomic sequencing [28].

- Robust Purity: The 260/280 absorbance ratios for DNA extracted with the THSTI method were generally within the acceptable range (1.6-1.9), indicating low protein contamination and pure nucleic acid preparations suitable for PCR and sequencing [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: The THSTI Method

The efficacy of the THSTI method stems from its comprehensive, multi-stage approach to cell lysis and DNA purification. The following workflow details the critical steps as described in the foundational protocol [27] [28].

Diagram 1: THSTI Method Workflow for Metagenomic DNA Extraction.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Enzymatic Pre-treatment (Spheroplast Formation):

- Samples are treated with a cocktail of enzymes including lysozyme, lysostaphin, and mutanolysin [28] [30].

- These enzymes target the glycoside-linkages and transpeptide bonds in the peptidoglycan layer of bacterial cell walls (both Gram-positive and Gram-negative), creating fragile spheroplasts that are highly susceptible to subsequent lysis [28].

Chemical Lysis:

- Spheroplasts are treated with Guanidinium Thiocyanate (GITC), a powerful chaotropic agent that disrupts cell membranes and simultaneously inactivates nucleases that could degrade exposed DNA [28].

Mechanical and Physical Lysis:

DNA Precipitation and Purification:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents used in the THSTI method and their specific functions in the lysis and purification process [28] [30].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents in the THSTI Workflow

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Role in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Lysozyme | Hydrolyzes 1,4-beta linkages in Gram-positive bacterial cell walls. |

| Lysostaphin | Cleaves glycine-glycine bonds in the peptidoglycan of Staphylococcus species. |

| Mutanolysin | Lyses Gram-positive bacteria by hydrolyzing the peptidoglycan. |

| Guanidinium Thiocyanate (GITC) | Chaotropic salt; denatures proteins, inactivates nucleases, and disrupts membranes. |

| Bead Beating | Mechanical disruption using beads to break tough cell walls (e.g., spores). |

| Salt (e.g., NaCl, NaAc) | Neutralizes DNA charge, facilitating aggregation during ethanol precipitation. |

| Organic Solvent (e.g., Ethanol, Isopropanol) | Reduces DNA solubility, causing precipitation out of solution for concentration. |

Discussion and Research Implications

The comparative data strongly supports the THSTI method as a highly effective manual workflow for comprehensive metagenomic DNA extraction. Its primary advantage lies in the combinatorial lysis strategy, which mitigates the bias introduced by methods that rely on a single lysis mechanism. This is particularly crucial for accurately representing the entire microbial community, including hard-to-lyse organisms [27] [28].

The choice of DNA extraction method can directly influence the observed microbial community structure. For instance, the inclusion of mechanical bead beating has been shown to influence the recovery of certain fungal groups; one study found it enriched for filamentous fungi, while methods without this step showed a higher relative abundance of yeasts [24]. Therefore, for studies aiming for a broad and unbiased profile of both bacterial and fungal communities, a rigorous method like THSTI is advantageous.

While automated systems offer higher throughput, the THSTI method provides researchers with full control over the protocol, which can be optimized for specific sample matrices. The trade-off is the hands-on time required, making it ideal for projects where maximizing DNA yield and quality from complex and limited samples is the highest priority.

In the context of benchmarking bacterial and fungal DNA sampling methods, the manually executed THSTI method stands out for its performance. By integrating enzymatic, chemical, mechanical, and physical lysis, it achieves higher DNA yields and better quality high molecular weight DNA compared to several commercial kit and automated alternatives. For research applications such as shotgun metagenomics that demand high-quality, unbiased genomic data, the THSTI protocol represents a robust and validated manual workflow worthy of strong consideration by scientists in basic research and drug development.

The advancement of molecular diagnostics and microbiome research is fundamentally reliant on the efficient and consistent extraction of microbial DNA. Effective purification methods maximize DNA yield and purity, which are critical determinants for the success of downstream analytical protocols such as PCR and sequencing [31]. Automated extraction platforms have emerged as powerful tools to address the challenges of throughput, reproducibility, and handling of low-abundance microbial targets in complex matrices like whole blood and tissues [32] [33]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of two automated systems—the GraBon system and the Maxwell systems—framed within the context of a broader thesis on bacterial and fungal DNA sampling methods. We summarize direct experimental data and methodologies to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in making informed platform selections.

Performance Comparison: GraBon vs. Alternative Methods

Quantitative Comparison of Diagnostic Accuracy

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics of the GraBon system compared to other DNA extraction methods, as established in a recent clinical study focused on pathogen detection in whole blood.

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of DNA Extraction Methods for Sepsis Pathogens [32]

| Pathogen | Extraction Method | Technology | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | Column-based | 30.0 (16.56–46.53) | 100 (91.19–100.0) | 65.0 |

| K-SL DNA Extraction Kit | Magnetic Bead-based (Manual) | 55.0 (38.49–70.74) | 100 (91.19–100.0) | 77.5 | |

| GraBon | Magnetic Bead-based (Automated) | 52.0 (36.13–68.49) | 100 (91.19–100.0) | 76.5 | |

| S. aureus | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | Column-based | 35.0 (20.63–51.68) | 100 (91.19–100.0) | 67.5 |

| K-SL DNA Extraction Kit | Magnetic Bead-based (Manual) | 35.0 (20.63–51.68) | 100 (91.19–100.0) | 67.5 | |

| GraBon | Magnetic Bead-based (Automated) | 55.0 (38.49–70.74) | 100 (91.19–100.0) | 77.5 |

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Features

Beyond diagnostic accuracy, the operational characteristics of a DNA extraction system are vital for laboratory workflow. The table below contrasts the core features of the GraBon system with a generalized profile for the Maxwell systems, which are also prominent automated, magnetic bead-based platforms.

Table 2: Methodological and Operational Comparison of Automated Platforms

| Feature | GraBon System [32] | Generalized Maxwell Systems Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Core Technology | Magnetic bead-based | Magnetic bead-based |

| Automation Level | Fully automated | Fully automated |

| Throughput | Not explicitly stated; utilizes robotic handling | Known for modular scalability (e.g., 16-48 samples per run) |

| Sample Input Volume | 500 µL | Typically up to 300-500 µL, depending on the specific cartridge |

| Elution Volume | 100 µL | Typically 50-100 µL |

| Key Differentiating Mechanism | Bacterial isolation pre-lysis; motor-driven rotating tip for vigorous vortexing | Pre-packaged, cartridge-based reagents for hands-off operation |

| Demonstrated Clinical Advantage | Superior accuracy for S. aureus; effective for Gram-positive bacteria due to vigorous lysis | Widely documented for circulating DNA and viral extraction; high consistency |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Detailed Methodology: GraBon System Evaluation

The performance data for the GraBon system presented in Table 1 was generated through the following experimental protocol, which highlights the critical steps for optimal results [32].

- Sample Preparation: Whole blood samples were spiked with known concentrations of E. coli (Gram-negative) and S. aureus (Gram-positive) to simulate bloodstream infections.

- DNA Extraction - GraBon Protocol:

- Bacterial Isolation: The automated process begins with the GraBon system using magnetic beads to isolate and separate bacteria from the whole blood matrix before the lysis step. This reduces co-purification of PCR inhibitors present in blood.

- Cell Lysis: The system employs a unique, motor-driven rotating plastic tip to create vigorous vortexing within the sample tube. This mechanical lysis is particularly effective at disrupting the tough peptidoglycan cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria like S. aureus.

- DNA Binding and Purification: The lysate is transferred, and bacterial DNA is bound to magnetic beads.

- Washing: Contaminants and impurities are removed through a series of wash steps while the DNA remains bound to the beads.

- Elution: Purified DNA is eluted in a final volume of 100 µL. Processing a 500 µL sample into a 100 µL elution provides a 5-fold concentration effect, enhancing detection sensitivity for low bacterial loads.

- Downstream Analysis: The extracted DNA was analyzed via real-time PCR using specific primers for E. coli and S. aureus to determine detection sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy.

Workflow Visualization: Automated DNA Extraction

The following diagram illustrates the generalized logical workflow for automated, magnetic bead-based DNA extraction, common to both GraBon and Maxwell systems, while highlighting the key differentiating step for GraBon.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful DNA extraction relies on a suite of specialized reagents and kits. The table below details essential solutions used in the studies cited, which are foundational to this field of research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial DNA Studies

| Research Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| K-SL DNA Extraction Kit [32] | Manual magnetic bead-based extraction of bacterial DNA from whole blood. | Serves as the manual counterpart and reagent base for the automated GraBon system. |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit [34] | Depletes host DNA to enrich for microbial DNA, improving sequencing depth for low-biomass samples. | Critical for microbiome studies from samples with high human-to-microbe DNA ratio (e.g., skin, tissues). |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit [33] | Efficiently extracts DNA from complex, tough-to-lyse environmental and sample types, including soil and stool. | Standard for gut microbiome and environmental microbial studies. |

| QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit [31] | Optimized for purifying short-fragment DNA and RNA from plasma, such as cell-free DNA. | Gold standard for liquid biopsy and circulating pathogen DNA studies. |

| E.Z.N.A. Bacterial DNA Kit [33] | Designed for the extraction of high-purity genomic DNA from bacterial cultures and tissues. | Commonly used for targeted DNA extraction from bacterial samples and tissue biopsies. |

The comparative data indicates that automated magnetic bead-based systems like GraBon offer significant advantages for clinical diagnostics, particularly for challenging applications like sepsis. The GraBon system demonstrates enhanced performance, especially for Gram-positive pathogens, attributable to its pre-lysis bacterial isolation and aggressive mechanical disruption [32]. While this guide provides data on GraBon, a complete direct comparison with the Maxwell systems under identical experimental conditions is a necessary area for future research.

The selection of an automated DNA extraction system must be guided by the specific research or clinical application. Key considerations include the sample matrix (whole blood, tissue, plasma), the type of microorganism (bacterial vs. fungal, Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative), and the required throughput and consistency for the intended workflow. The methodologies and data presented here provide a framework for this critical evaluation.

The accuracy of downstream molecular analyses in life science research is fundamentally dependent on the initial steps of sample preparation. Variations in protocols for handling different sample matrices can introduce significant bias, affecting data reliability and cross-study comparability. This guide objectively compares established and novel methods for processing three complex sample types: whole blood (requiring erythrocyte lysis), stool (requiring homogenization), and low-biomass lung tissue. The focus is on evaluating protocol performance based on DNA yield, microbial community fidelity, and practical implementation for research and drug development applications. Experimental data from controlled comparisons are synthesized to provide evidence-based recommendations.

Blood Sample Processing: Erythrocyte Lysis Protocols

The removal of red blood cells (RBCs) via osmotic lysis is a critical first step in analyzing peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) for flow cytometry or molecular assays. The choice of lysis buffer and incubation conditions must effectively lyse erythrocytes while preserving the viability and integrity of leukocytes.

Quantitative Comparison of RBC Lysis Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Red Blood Cell Lysis Protocols for Various Species

| Component/Parameter | Ammonium Chloride Lysis Buffer (1X) | 1-Step Fix/Lyse Solution | Species-Specific Variations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Components | 8.02g/L NH₄Cl, 0.84g/L NaHCO₃, 0.37g/L EDTA [35] | Proprietary formulation (combines fixative and lysing agents) [36] | |

| Lysis Mechanism | Osmotic shock [36] | Osmotic shock and chemical fixation [36] | |

| Typical Lysis Time (Whole Blood) | 10-15 minutes (Human) [35] [36] | 15-60 minutes [36] | Mouse/Rat: 4-10 minutes [36] |

| Recommended Buffer Volume to Sample | 10 mL buffer per 1 mL human blood [35] | 2 mL 1X solution per 100 µL blood [36] | |

| Key Advantage | Minimal effect on leukocyte viability; suitable for subsequent cell culture [36] | Simultaneously lyses RBCs and fixes leukocytes, stabilizing samples for analysis [36] | |

| Primary Application | Flow cytometric analysis or cell culture after staining [35] | Flow cytometric analysis, especially when sample storage is required post-staining [36] | Mouse/Rat Tissues: Use 1X RBC Lysis Buffer on single-cell suspensions from spleen/bone marrow; incubate 4-5 minutes [35] [36] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Bulk Lysis of Human Whole Blood

The following protocol is adapted for processing human whole blood using an ammonium chloride-based lysis buffer [35] [36].

- Step 1: Add 10 mL of room-temperature 1X RBC Lysis Buffer per 1 mL of human whole blood (collected using heparin or EDTA as an anti-coagulant).

- Step 2: Incubate for 10-15 minutes at room temperature. Critical: Do not exceed 15 minutes. Observe turbidity; the solution becomes clear when lysis is complete.

- Step 3: Centrifuge at 500 x g for 5 minutes at room temperature to pellet leukocytes. Decant the supernatant.

- Step 4: Resuspend the cell pellet in an appropriate volume of buffer (e.g., Flow Cytometry Staining Buffer or culture medium).

- Step 5: Perform a cell count and viability analysis. The cells are now ready for downstream applications like staining for flow cytometry or placing in culture. Note: If cells are destined for culture, all steps must be performed using aseptic techniques.

Stool Sample Processing: The Impact of Homogenization

Stool is a heterogeneous mixture, and the method of subsampling can greatly influence the observed microbial community and metabolite concentrations. Homogenization is a key strategy to address this spatial variability.

Experimental Data on Homogenization Efficacy

Table 2: Impact of Stool Homogenization on Microbiome and Metabolite Analysis

| Analysis Method | Effect of Homogenization (vs. Non-Homogenized Spot Sampling) | Supporting Experimental Data | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Sequencing (Bacteria) | Significantly reduces intra-individual variation in detected bacteria [37]. | One study showed homogenization by blending or pneumatic mixing reduced variation within a single stool sample [37]. | |

| ITS2 Sequencing (Fungi) | Reduces variability in the mycobiome profile, though fungal communities remain more challenging to characterize due to lower biomass and library preparation issues [38]. | ||

| Short-Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA) Profiling | Leads to more consistent metabolite concentrations. Non-homogenized spot sampling results in variable SCFA levels [38]. | Acetic and valeric acid were as variable in a single stool as across different days without homogenization [38]. | |

| Taxonomic Specificity | Alters the relative abundance of specific taxa. Frozen and homogenized stools showed higher proportions of Faecalibacterium, Streptococcus, and Bifidobacterium, and decreased Oscillospira, Bacteroides, and Parabacteroides compared to small, non-mixed samples [37]. | ||

| Differential Abundance | Non-homogenized aliquots can show significantly different abundance for specific ASVs. One study identified 12 bacterial and 16 fungal features with a log2 fold change > | 2.5 | between aliquots and homogenized whole stool [38]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Homogenization of Stool Samples

The following method is derived from studies comparing fecal processing techniques [37] [38].

- Step 1: Collection. Collect the complete stool specimen. For optimal consistency, collecting the first full bowel movement of the day is recommended [38].

- Step 2: Pre-treatment. For fresh homogenization, proceed immediately. For frozen homogenization, freeze the entire stool specimen at -80°C.

- Step 3: Homogenization.

- Step 4: Aliquoting. After full homogenization, subsample the required volume (e.g., 200 mg) for DNA extraction or metabolite analysis.

- Step 5: Storage. Immediately freeze the aliquots at -80°C until nucleic acid extraction or other downstream processing.

Low-Biomass Lung Tissue: DNA Extraction and Contamination Control

The lung presents a unique challenge due to its low microbial biomass, where signal can be easily overwhelmed by contaminating DNA from reagents or the environment. The DNA extraction method is therefore paramount.

Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods for Low-Biomass Lung Tissue

Table 3: Evaluation of DNA Extraction Protocols for Lung Tissue Microbiome Analysis

| Extraction Protocol Component | Impact on DNA Yield and Quality | Impact on Microbial Community Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Bead-Beating Step | Slightly increases DNA yield compared to basic protocols [39]. Essential for lysing tough cell walls (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria) [40]. | Increases the proportion of Gram-positive bacteria recovered; essential for a representative community profile [40]. |

| Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol Step | Significantly increases DNA concentration and improves purity (260/280 ratio) when combined with bead-beating [39]. | Changes the relative abundance of some bacterial and fungal taxa [39]. |

| Enzymatic Pre-treatment | Further increases microbial DNA concentration without increasing human DNA background, potentially by digesting non-viable cells [39]. | May make the microbial profile more representative of the actual living community by removing DNA from dead cells [39]. |

| PEG/NaCl Precipitation (vs. Silica Columns) | Higher DNA recovery efficiency from Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF); extracts are clearly distinguishable from negative controls [40]. | Reduces the pernicious effect of environmental contaminant DNA, providing a profile more reflective of the true low-biomass community [40]. |

| Contamination Mitigation (Negative Controls) | Critical for identifying background DNA. Common contaminants include Pseudomonadaceae, Streptococcaceae, and Aspergillaceae [39]. | Bioinformatic removal of contaminant sequences (e.g., those 100% identical to negative controls) is necessary for accurate analysis [39]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Optimized DNA Extraction for Lung Tissue

This protocol synthesizes methods from published comparisons to maximize recovery and minimize contamination [39] [40] [41].

- Step 1: Pre-processing. Centrifuge BALF (1 mL) at 20,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C. Discard supernatant and resuspend pellet in 100 µL PBS.

- Step 2: Enzymatic Lysis. Resuspend lung tissue homogenate or BALF pellet in a lysis buffer containing lysozyme and incubate with mixing (e.g., 500 rpm, 37°C, 30 min) [40].

- Step 3: Mechanical Lysis (Bead-Beating). Transfer the suspension to a tube containing zirconia/silica beads (0.1 mm diameter). Bead-beat using a cell disrupter (e.g., 4 pulses of 1 min each) to ensure complete mechanical disruption of robust cell walls [40].

- Step 4: DNA Purification (PEG Method). Purify DNA using a polyethylene glycol (PEG)/NaCl precipitation protocol instead of, or in combination with, silica columns to improve recovery of low-concentration DNA [40].

- Step 5: Contamination Control. Include negative control samples (containing only lysis buffer) throughout the entire DNA extraction and sequencing process to allow for bioinformatic identification and subtraction of contaminant sequences [39] [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Sample Preparation Protocols

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Chloride (NH₄Cl) Lysis Buffer | Lyses red blood cells via osmotic shock, sparing leukocytes [35] [36]. | Isolation of PBMCs from human whole blood for flow cytometry [35]. |

| 1-Step Fix/Lyse Solution | Simultaneously lyses RBCs and fixes leukocytes, stabilizing samples for later analysis [36]. | Staining of whole blood for flow cytometry when immediate analysis is not possible [36]. |

| Zirconia/Silica Beads (0.1 mm) | Mechanical disruption of tough microbial cell walls (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria, fungi) during DNA extraction [39] [40]. | Bead-beating step in DNA extraction from stool or low-biomass lung samples to ensure complete lysis [40]. |

| Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol | Organic solvent used to separate DNA from proteins and other cellular contaminants during nucleic acid purification [39]. | Purification step in DNA extraction protocols to increase yield and purity, especially from complex samples [39]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) with NaCl | Precipitates DNA molecules, providing an alternative or complementary purification method to silica columns [40]. | Enhanced recovery of microbial DNA from low-biomass samples like BALF [40]. |

| DNA/RNA Shield or Similar Stabilizing Reagents | Protects nucleic acids from degradation during sample storage and transport [41]. | Preservation of stool samples or microbial mock communities at ambient temperatures for short periods [41]. |

Visual Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams summarize the core experimental workflows for processing each sample type, highlighting critical steps that impact downstream results.

The selection of an optimal DNA extraction method is a critical foundational step in molecular research, directly influencing the reliability, accuracy, and reproducibility of downstream analyses. The choice between widespread technological platforms—specifically, column-based silica membranes and magnetic bead-based purification—presents a significant consideration for researchers designing experiments across fields from clinical diagnostics to environmental microbiology. Column-based methods, exemplified by the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, utilize a silica membrane in a spin-column format that binds DNA in the presence of high-salt buffers. In contrast, magnetic bead-based methods, such as the K-SL DNA Extraction Kit and systems leveraging PowerSoil chemistry, employ paramagnetic particles that bind nucleic acids when exposed to a magnetic field.

This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these technologies, framing them within a broader thesis on comparative bacterial and fungal DNA sampling methodologies. It synthesizes recent comparative studies to evaluate kit performance across critical parameters including DNA yield, purity, taxonomic bias, and diagnostic accuracy, providing researchers with evidence-based insights for protocol selection.

Performance Comparison in Clinical & Environmental Samples

The performance of DNA extraction technologies is highly dependent on sample matrix. The following tables summarize key experimental findings from direct comparisons in blood and diverse ecosystem samples.

Table 1: Performance Comparison in Clinical Whole Blood Samples for Sepsis Diagnosis [42]

| Extraction Method | Technology | Accuracy for E. coli Detection | Accuracy for S. aureus Detection | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-SL DNA Extraction Kit | Magnetic Bead-based | 77.5% (22/40) | 67.5% (14/40) | 100% |

| GraBon System | Magnetic Bead-based | 76.5% (21/40) | 77.5% (22/40) | 100% |

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | Column-based | 65.0% (12/40) | 67.5% (14/40) | 100% |

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Terrestrial Ecosystem Sample Matrices [9]

| Extraction Kit | Technology | Sample Types Tested | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| NucleoSpin Soil (MNS) | Column-based | Bulk soil, rhizosphere soil, invertebrate, mammalian feces | Highest alpha diversity estimates; highest contribution to overall sample diversity. |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Pro (QPS) | Column-based (Optimized for inhibitors) | Bulk soil, rhizosphere soil, invertebrate, mammalian feces | Consistently high performance; streamlined Inhibitor Removal Technology (IRT). |

| QIAamp DNA Stool Mini (QST) | Column-based | Mammalian feces | Best DNA yield for hare feces; significant yield variation for other sample types. |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue (QBT) | Column-based | All sample types | Lowest ratio in mock community Gram+/Gram- test, indicating bias. |

Table 3: Performance in Whole Metagenome Shotgun Sequencing of Human Microbiome [43]

| Extraction Kit | Technology | Performance with Mock Community | Performance in Clinical Swabs |

|---|---|---|---|

| PowerSoil Pro | Column-based (Optimized for inhibitors) | Best approximation of expected microbial proportions. | Representative microbial community profiling. |

| HostZERO | Magnetic Bead-based | Biased against Gram-negative bacteria; superior fungal DNA yield. | Biased community representation; highest fraction of bacterial reads; lowest human host DNA. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide clear insight into the data generation methods, the experimental protocols from key cited studies are detailed below.

- Sample Collection: Whole blood samples were obtained from patients with suspected sepsis.

- DNA Extraction Comparison:

- Column-based method: The QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. This process involves cell lysis, binding of DNA to the silica membrane in a spin column, multiple wash steps, and final elution.

- Magnetic bead-based methods: The K-SL DNA Extraction Kit and the automated GraBon system were used following their respective protocols. These methods involve lysing samples and binding DNA to functionalized magnetic beads. Beads are captured with a magnet, washed, and the DNA is eluted.