Optimizing MAG Quality: A Researcher's Guide to Troubleshooting Genome Completeness and Contamination

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and bioinformatics professionals tackling the critical challenges of metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) quality.

Optimizing MAG Quality: A Researcher's Guide to Troubleshooting Genome Completeness and Contamination

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and bioinformatics professionals tackling the critical challenges of metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) quality. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, we detail the sources and impacts of low completeness and high contamination in MAGs. The guide offers actionable strategies for sample preparation, sequencing, assembly, and binning to optimize genome quality. It further explores validation techniques and comparative analyses using curated databases to ensure MAGs meet the stringent standards required for robust microbial discovery, functional annotation, and downstream biomedical research, ultimately enhancing the reliability of genomic insights from uncultured microorganisms.

Understanding MAG Quality: Why Completeness and Contamination Matter

The Minimum Information about a Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MIMAG) standards were established by the Genomic Standards Consortium (GSC) to provide consistent guidelines for reporting bacterial and archaeal genome sequences recovered from metagenomic data. These standards represent an extension of the Minimum Information about Any (x) Sequence (MIxS) framework and include specific criteria for assessing assembly quality, genome completeness, and contamination [1].

As metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) have revolutionized microbial ecology by enabling genome-resolved study of uncultured microorganisms, the MIMAG standards ensure that genomic data deposited in public databases meets minimum quality requirements for robust comparative analyses. The standards facilitate more accurate assessments of bacterial and archaeal diversity across diverse environments, from human gut microbiomes to extreme habitats [1] [2].

MIMAG Quality Classification Table

The MIMAG standard establishes clear, quantitative thresholds for classifying MAG quality based on completeness, contamination, and the presence of key genetic elements [3].

Table 1: MIMAG Quality Standards for Metagenome-Assembled Genomes

| Quality Tier | Completeness | Contamination | rRNA Genes | tRNA Genes | Assembly Quality Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality draft | >90% | <5% | Presence of 23S, 16S, and 5S | At least 18 tRNAs | Multiple fragments where gaps span repetitive regions [3] |

| Medium-quality draft | ≥50% | <10% | Not required | Not required | Many fragments with little to no review of assembly [3] |

| Low-quality draft | <50% | <10% | Not required | Not required | Many fragments with little to no review of assembly [3] |

Understanding Completeness and Contamination Metrics

How Completeness and Contamination are Calculated

The standard method for assessing MAG quality relies on universal single-copy genes (SCGs) - genes that are typically found in all known life and in only one copy per genome [4]. Several lists of these genes exist, with common sets containing 139-150 bacterial marker genes [5].

- Completeness Score: The ratio of observed single-copy marker genes to the total number of unique SCGs in the chosen marker gene set, expressed as a percentage [3].

- Contamination Score: The ratio of observed single-copy marker genes present in two or more copies to the total number of unique SCGs in the chosen marker gene set, expressed as a percentage [3].

Important Limitations and Biases

A critical consideration when working with these metrics is that SCG-based assessments only work well when genomes are relatively complete [4]. There is a known bias where:

- Completeness is overestimated in incomplete bins

- Contamination is underestimated in incomplete bins [4]

This occurs because marker genes residing on foreign DNA that are otherwise absent in a genome can be mistakenly interpreted as increased completeness rather than contamination. This bias is minimal (<2%) in genomes over 70% complete with <5% contamination, but becomes more significant in lower-quality assemblies [4].

Experimental Protocols for Quality Assessment

Standard Workflow for MAG Quality Control

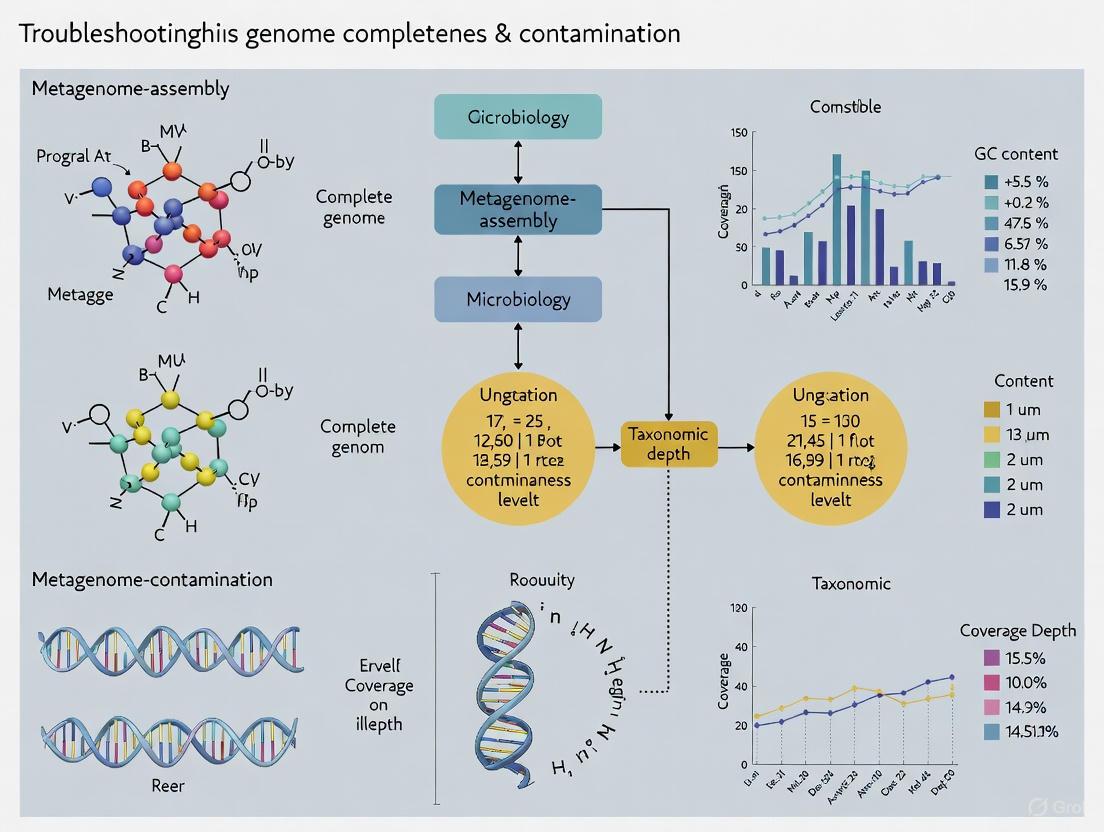

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for assessing MAG quality according to MIMAG standards:

Recommended Tools and Software

Table 2: Essential Bioinformatics Tools for MAG Quality Assessment

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CheckM | Completeness/contamination estimation | Uses single-copy marker genes; provides lineage-specific workflows | [5] [4] |

| Anvi'o | Genome bin refinement & visualization | Interactive bin refinement; uses term "redundancy" instead of contamination | [5] |

| GTDB-Tk | Taxonomic classification | Standardized taxonomy based on Genome Taxonomy Database | [6] |

| metaWRAP | Bin refinement & integration | Combines multiple binning tools; improves bin quality | [6] |

| ProDeGe | Automated decontamination | Implements protocol for automated decontamination of genomes | [1] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the practical difference between contamination and redundancy?

While often used interchangeably, some experts distinguish these terms:

- Redundancy: An objective observation of multiple copies of typically single-copy genes

- Contamination: A suggestion that foreign DNA from different organisms is present in the bin

As one researcher notes: "If a bacterial genome that did not end up in our cultivars has multiple copies of one of those many so-called single copy genes, it wouldn't mean it is 'contaminated'" [5]. This distinction emphasizes that high redundancy requires evidence before labeling a bin as contaminated.

My bin has >10% contamination/redundancy. What should I do?

You have two primary options:

- Refine the bin using interactive tools like Anvi'o or metaWRAP to remove contaminating contigs

- Remove the bin from your analysis if refinement produces fragmented, low-completeness genomes

As a general rule: "You must try to clean it up. This can be your golden rule, and maximum 10% redundancy would be a way to make sure you are not shooting yourself in the foot" [5].

Why does my MAG show high contamination even after careful binning?

High contamination estimates can result from several biological and technical factors:

- Strain heterogeneity: Multiple closely related strains in the same sample

- Horizontal gene transfer: Naturally occurring gene transfers between organisms

- Binning errors: Misgrouping of contigs from different organisms

- Assembly artifacts: Chimeric contigs formed during assembly

Are there specific considerations for archaeal genomes?

Yes, standard bacterial single-copy gene sets may not accurately assess archaeal genomes. For archaeal MAGs, ensure you're using domain-specific marker gene sets rather than bacterial-centric tools [5].

How does sequencing technology affect MAG quality?

Both short-read (Illumina) and long-read (PacBio, Nanopore) technologies impact MAG quality:

- Short-reads: Higher accuracy but more fragmented assemblies

- Long-reads: Better continuity but higher error rates

Hybrid approaches often yield the best results, with HiFi reads particularly valuable for improving assembly quality [7].

Key Recommendations for Researchers

- Always use multiple quality assessment tools to cross-validate your results

- Be cautious with low-completeness bins (<70%) due to inherent biases in SCG analysis

- Document your quality thresholds clearly in publications and database submissions

- Use the MIMAG standard consistently to enable comparative analyses across studies

- Consider biological context when interpreting contamination estimates—some organisms naturally have multiple copies of "single-copy" genes

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MAG Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Single-copy gene sets | Reference markers for quality assessment | Campbell et al. set (139 genes) is widely used; ensure appropriate taxonomic scope |

| CheckM database | Lineage-specific marker sets | Provides more accurate completeness estimates for specific taxonomic groups |

| GTDB database | Taxonomic classification | Standardized taxonomy framework for MAG classification |

| NCBI Genome Database | Reference genomes | Essential for comparative genomics and validation |

| MIMAG checklist | Standardized reporting | Ensures complete metadata and comparable data reporting |

Metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) have revolutionized microbial ecology by enabling the genome-resolved study of uncultured microorganisms directly from environmental samples [2]. However, the completeness and contamination levels of reconstructed MAGs are profoundly influenced by the sample type from which they are derived. Soil, gut, and aquatic environments present distinct biochemical compositions, microbial densities, and community complexities that introduce unique methodological challenges. This technical support center addresses these sample-specific obstacles within the broader context of troubleshooting MAG completeness and contamination, providing targeted guidance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does sample type fundamentally impact MAG quality and recovery?

The sample origin directly influences every stage of MAG generation, from DNA extraction to genome binning, due to intrinsic properties such as microbial density, diversity, and the presence of inhibitory substances [2].

- Soil presents the greatest challenge due to its extreme microbial diversity and the presence of humic acids that inhibit downstream molecular applications. This often results in a low yield of high-quality MAGs relative to the true diversity.

- Gut samples typically have high microbial biomass but contain host DNA that can contaminate assemblies. The community is less diverse than soil, often facilitating the recovery of more complete MAGs.

- Aquatic environments, particularly oligotrophic ones, are low-biomass systems. The low microbial density means that contamination from reagents and sampling equipment can constitute a significant portion of the sequenced DNA, severely impacting MAG contamination metrics [8].

Q2: What are the best practices for preventing contamination in low-biomass aquatic samples?

Preventing contamination in low-biomass samples requires a vigilant, multi-layered approach [8]:

- Decontaminate Equipment: Thoroughly decontaminate all tools and vessels. A two-step process using 80% ethanol (to kill organisms) followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution like sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or UV-C irradiation is recommended to remove trace DNA.

- Use Appropriate Controls: It is critical to include multiple negative controls during sampling. These can include an empty collection vessel, a swab of the air, or an aliquot of the preservation solution. These controls must be processed alongside your samples to identify contaminating sequences for later removal.

- Employ Physical Barriers: Use personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves, masks, and cleanroom suits to limit sample contact with operators, who are a significant source of human-derived contaminants and aerosols.

Q3: Why is MAG recovery from soil particularly challenging, and how can it be improved?

Soil is one of the most complex environments on Earth, with immense microbial diversity where a single gram can contain thousands of species [9]. This high complexity means that sequencing efforts must be distributed across many genomes, making it difficult to assemble longer, uncontiguous sequences (contigs) for any single organism. Consequently, soil MAGs often have lower completeness and higher fragmentation.

Improvement strategies include:

- Increased Sequencing Depth: Allocating significantly more sequencing reads per soil sample is necessary to probe the "rare biosphere" and improve genome coverage.

- Multi-sample Binning: Using advanced binning tools like SemiBin2 that co-assemble and bin sequences across multiple samples can help recover more complete genomes from complex communities [9].

- Hybrid Sequencing: Combining long-read and short-read sequencing technologies can help resolve repetitive regions and produce more complete assemblies.

Q4: How can I handle host DNA contamination in gut microbiome studies?

Host DNA from human or animal cells can dominate sequencing libraries in gut samples, reducing the number of microbial reads and thus MAG quality.

- Differential Lysis: Use extraction protocols that incorporate steps to lyse microbial cells selectively while leaving larger host cells intact.

- Commercial Kits: Employ host depletion kits that are designed to selectively bind and remove host DNA (e.g., mammalian DNA) from the sample.

- Bioinformatic Filtration: After sequencing, align reads to the host genome (e.g., human, mouse) and remove those that match before proceeding with de novo assembly.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Contamination Levels in MAGs from All Sample Types

- Problem: Reconstructed MAGs show high contamination (e.g., >10%), indicated by the presence of multiple single-copy marker genes.

- Diagnosis: Contamination can be introduced during sampling (cross-contamination between samples), from reagents (kit-borne microbial DNA), or during bioinformatic binning (merging of sequences from different organisms).

- Solutions:

- Wet Lab: Use DNA-free reagents and collection tubes. Include negative extraction controls. For low-biomass samples, adopt cleanroom techniques and decontaminate surfaces with bleach or UV light [8].

- Bioinformatic: Utilize tools like

MetaWRAPto refine bins and remove contaminant contigs. Always subtract contaminants identified in your negative controls from your dataset [10].

Issue 2: Low Completeness of MAGs from Soil Samples

- Problem: Soil-derived MAGs are predominantly of low or medium quality, with completeness below 90%.

- Diagnosis: This is typically due to the high microbial diversity and uneven abundance of organisms in soil, leading to fragmented assemblies and insufficient coverage for rare taxa.

- Solutions:

- Sequencing: Drastically increase sequencing depth per sample. Consider using long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio or Nanopore) to generate longer contigs.

- Binning: Implement multi-sample or co-assembly binning strategies. Tools like

SemiBin2have been shown to improve binning performance in complex environments like soil [9]. - Analysis: Focus on recovering population-level genomes instead of chasing single, near-complete MAGs for all taxa.

Issue 3: Dominance of Non-Target DNA in Aquatic or Host-Associated Samples

- Problem: In aquatic samples, reagent contamination is prevalent. In gut samples, host DNA dominates the sequencing library.

- Diagnosis: The signal-to-noise ratio is poor because the target microbial DNA is vastly outnumbered by contaminating or host DNA.

- Solutions:

- Aquatic: Sequence your negative controls (e.g., blank water) to create a "background contamination" profile. Subtract these contaminants bioinformatically from your actual samples [8].

- Gut: Use a host DNA depletion protocol during DNA extraction. Bioinformatically, map all reads to the host genome and discard matching reads prior to assembly.

The following tables summarize key quantitative challenges and outcomes associated with different sample types, based on recent large-scale studies.

Table 1: Sample Type Characteristics and Their Impact on MAG Generation

| Sample Type | Typical Microbial Density | Diversity (Species per gram/sample) | Major Contaminants | Typical MAG Yield & Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | Very High (10^8-9 cells/g) | Extremely High (Thousands) | Humic acids, fungal DNA | Low yield of high-quality MAGs relative to true diversity [9]. |

| Human Gut | High (10^10-11 cells/g) | Moderate (Hundreds) | Host DNA | High yield of high-quality MAGs is possible [11] [10]. |

| Aquatic (Ocean) | Low (10^5-6 cells/mL) | Variable | Reagent DNA, co-assembled contaminants | Yield is highly dependent on biomass; high risk of contamination [8]. |

Table 2: Common Reagents and Materials for Contamination Control

| Research Reagent / Material | Function | Sample Type Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) | Degrades environmental DNA on surfaces and equipment. | All, especially critical for low-biomass (aquatic) and sterile site sampling [8]. |

| UV-C Light | Sterilizes surfaces and plasticware by damaging DNA. | All, used to pre-treat plasticware and work surfaces before use [8]. |

| DNA-Free Water & Reagents | Ensures no external microbial DNA is introduced during extraction. | All, a fundamental requirement for reliable results in any microbiome study. |

| RNAlater / OMNIgene.GUT | Preserves nucleic acid integrity during sample storage and transport. | Gut, tissue, and other samples where immediate freezing is not feasible [2]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Creates a barrier to prevent contamination from operators (skin, hair, breath). | All, with strictness scaled to sample biomass (critical for cleanrooms and low-biomass samples) [8]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standardized Workflow for MAG Generation Across Sample Types

The diagram below outlines a generalized workflow for generating MAGs, highlighting critical sample-specific troubleshooting points.

Detailed Protocol: Contamination-Aware Sampling for Low-Biomass Environments

This protocol is critical for aquatic samples, cleanrooms, or any low-biomass study [8].

Pre-sampling Preparation:

- Decontamination: Wipe all sampling equipment (cores, filters, bottles) with 80% ethanol, followed by a DNA-degrading solution (e.g., 0.5% bleach). Rinse with DNA-free water if necessary.

- Controls: Prepare multiple negative controls: a "blank" sample with DNA-free water processed through collection, and a "field blank" where a swab is exposed to the air or a sterile container is opened and closed at the sampling site.

During Sampling:

- PPE: Wear full PPE (gloves, mask, hair net, clean suit) to minimize human-derived contamination.

- Aseptic Technique: Use sterile, single-use tools whenever possible. Avoid touching any surface that is not the sample itself.

Sample Storage:

- Store samples immediately at -80°C or in an appropriate DNA/RNA stabilization buffer. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Bioinformatic Protocol: MAG Refinement and Contamination Removal

- Quality Control and Adapter Trimming: Use tools like

FastQCandTrimmomaticorfastp. - Metagenomic Assembly: Perform assembly using a suitable tool like

MEGAHIT(for complexity/diversity) ormetaSPAdes. - Binning: Use multiple binning tools (e.g.,

MetaBAT2,MaxBin2,SemiBin2) and consolidate outputs using a refiner likeMetaWRAP[9] [10]. - Quality Assessment: Evaluate bins using

CheckM2or similar based on MIMAG standards [10]:- High-quality: >90% completeness, <5% contamination.

- Medium-quality: ≥50% completeness, <10% contamination.

- Contamination Removal:

- Subtract reads/contigs that align to genomes found in your negative controls.

- Use

CheckMto identify bins with anomalous marker gene sets indicating mixed populations.

- Taxonomic Classification: Classify your high-quality MAGs using

GTDB-Tkto place them in a phylogenetic context [9] [10].

Table 3: Key Bioinformatics Tools and Databases for MAG Research

| Tool / Database | Category | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| SemiBin2 | Binning | Recovers MAGs from complex environments using semi-supervised binning. | Particularly effective for soil and other high-diversity samples [9]. |

| MetaWRAP | Pipeline | A wrapper that consolidates and refines bins from multiple binning tools. | Crucial for improving bin quality and reducing contamination [10]. |

| CheckM2 | Quality Assessment | Rapidly assesses MAG quality (completeness/contamination). | Faster and more user-friendly than the original CheckM. |

| GTDB-Tk | Taxonomy | Assigns taxonomy to MAGs based on the Genome Taxonomy Database. | Standard for classifying novel diversity uncovered by MAGs [9]. |

| MAGdb | Database | A curated repository of >99,000 high-quality MAGs from clinical, environmental, and animal samples [10]. | Invaluable for comparative analysis and placing new MAGs in context. |

Critical DNA Extraction Considerations for Preserving Genomic Integrity

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MAG) Completeness

Problem: Recovered MAGs show low completeness scores based on single-copy core gene (SCG) analysis.

Solutions:

- Verify Extraction Method Efficiency: For low-biomass samples, consider electric field-induced DNA capture methods, which can yield equivalent or superior results compared to commercial silica-based kits, as demonstrated by threshold cycles of 21.22 for microtip devices versus 22.10 for commercial kits with 50μL buccal swab samples [12].

- Optimize Lysis Conditions: Implement forceful lysis with precise temperature control (55°C to 72°C) and optimized pH buffers. For tough samples like plant material, use specialized kits with PVP to reduce polyphenol inhibition [13].

- Prevent DNA Degradation: Add antioxidants to storage solutions, maintain stable pH to prevent hydrolysis, and use nuclease inhibitors like EDTA during extraction [14].

- Evaluate Sample Input: Increase sample input volume where possible, as studies show higher tissue input generally yields higher DNA output [13].

Guide 2: Managing Contamination in MAG Bins

Problem: MAG bins show high redundancy in single-copy core genes, indicating potential contamination.

Solutions:

- Establish Quality Thresholds: Use the "golden rule" of ≤10% redundancy for bacterial MAGs based on Campbell et al.'s 139 bacterial single-copy core genes. Analysis of 4,021 closed genomes shows 94% have redundancy below 10% [5].

- Implement Rigorous Binning: Use differential coverage and tetranucleotide frequency patterns across multiple samples rather than hand-picking contigs to perfect SCG metrics [5].

- Leverage Multiple Binning Tools: Employ tools like DAS Tool that test multiple binning methods and select the best outcome for each population [15].

- Clean Compromised Bins: For MAGs with >10% redundancy, either refine through rebinning or discard to prevent contaminating databases. A bin with C63%/R16% refined into C44%/R4% and C40%/R7% represents proper handling of a contaminated bin [5].

Guide 3: DNA Degradation Across Sample Types

Problem: Extracted DNA is fragmented, compromising downstream assembly and binning.

Solutions:

- Sample-Type Specific Preservation:

- Eukaryotic cells: Centrifuge cultures, remove buffer, store at -20°C or -80°C [16].

- Tissue: Flash-freeze with liquid nitrogen or use ethanol stabilizers [16].

- Plant material: Store at -80°C or dehydrate with silica gel for long-term storage [16].

- Blood: Refrigerate for up to one week or freeze at -20°C/-80°C long-term [16].

- Control Mechanical Homogenization: Use instruments like Bead Ruptor Elite with optimized speed, cycle duration, and temperature to minimize DNA shearing [14].

- Avoid Repeated Freeze-Thaw: Aliquot DNA extracts to prevent degradation from temperature cycling.

Guide 4: Challenging Sample Types

Problem: Specific sample types present unique extraction challenges that compromise genomic integrity.

Solutions:

- FFPE Samples: Use adapted protocols with increased number of sections (4-6 sections of 10μm each), extended proteinase K digestion (overnight at 56°C), and heat deparaffinization instead of organic solvents [17].

- Plant Tissues: Employ specialized kits with PVP to reduce polyphenol inhibition and use mechanical disruption methods optimized for rigid cell walls [13].

- Buccal Swabs & Saliva: Use two swabs per isolation, extend lysis time, and consider magnetic bead-based methods with optimized chemistries to remove inhibitors [13].

- Microbial Communities: Implement bead beating with specialized bead types (ceramic, stainless steel) optimized for tough bacterial cell walls [14].

Quality Assessment Standards for MAGs

Table 1: MAG Quality Classification Standards

| Quality Category | Completeness | Contamination | rRNA Genes | tRNA Genes | Additional Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Draft | ≥90% | ≤5% | Complete 5S, 16S, 23S | ≥18 amino acids | N50 ≥10 kb, ≤500 scaffolds [18] [19] |

| Medium-Quality Draft | ≥50% | ≤10% | Partial | Any | Assembly possible [19] |

| Low-Quality Draft | <50% | >10% | None detected | Any | Useful for specific gene mining [19] |

| Near-Complete | ≥90% | ≤5% | Complete set | ≥20 amino acids | ≤200 scaffolds, N50 ≥136 kb [18] |

Table 2: DNA Extraction Quality Metrics by Sample Type

| Sample Type | Optimal Yield Indicator | Common Inhibitors | Specialized Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buccal Swabs | Threshold cycle ~21.22 (100μL sample) [12] | Bacterial contaminants, mucin | Two-swab method, extended lysis [13] |

| Saliva | Threshold cycle ~25.95 (nuclear DNA) [12] | Mucin, food particles | SDS pretreatment (0.08 g/mL final concentration) [12] |

| Plant Tissue | A260/A280 ≥1.6 [13] | Polysaccharides, polyphenols | PVP-containing buffers, CTAB methods [13] [16] |

| FFPE Tissue | DIN ≥1.60 [17] | Formalin cross-linking, paraffin | Slide scraping, extended proteinase K digestion [17] |

| Blood | Stable at room temperature up to 1 week [16] | Heparin, heme | Magnetic bead workflows, heparin-resistant kits [13] [16] |

| Stool | Flexible input volume adjustment | Complex inhibitors, bile salts | Mechanical homogenization, inhibitor removal steps [13] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Electric Field DNA Extraction from Buccal and Saliva Samples

Methodology based on microtip device research [12]:

Sample Preparation:

- Buccal swabs: Immerse in 1mL TE buffer (pH 7.5), vortex 30 seconds

- Saliva: Add SDS to 0.08 g/mL final concentration, vortex 10 seconds

Cell Lysis:

- Add proteinase-K (600 AU/L) and SDS (0.28 g/mL)

- Heat at 60°C for 10 minutes

DNA Capture:

- Apply 5μL sample to metallic ring suspension system

- Immerse gold-coated microtips into sample

- Apply AC voltage of 20 Vpp at 5 MHz for 30 seconds

- Withdraw chips at 100 μm/s with continuous AC potential

- Air dry for 2 minutes for DNA preservation

DNA Elution:

- Immerse chips in 30μL TE buffer (pH 8.5)

- Heat at 70°C for 4 minutes

Validation: qPCR analysis with 100bp and 1500bp amplicons shows equivalent performance to commercial kits with fewer processing steps [12].

Protocol 2: Adapted FFPE DNA Extraction for Lung Tissue

Modified from Qiagen GeneRead DNA FFPE protocol [17]:

Sample Preparation:

- Cut 4-6 sections of 10μm from FFPE blocks

- For small samples (<4cm²), use 6 sections; for larger samples, use 4 sections

Deparaffinization:

- Omit organic deparaffinization solution

- Rely on heat-based deparaffinization

Lysis and Digestion:

- Add mixture of 55μL RNase-free water, 25μL FTB buffer, 20μL proteinase K

- Vortex and centrifuge at 15,093g for 1 minute

- Incubate at 56°C for 16 hours (overnight)

Heat Treatment:

- Incubate at 90°C for 1 hour

DNA Purification:

- Continue with standard QIAamp MinElute column purification

- Elute in 30μL ATE buffer

Performance: This adapted protocol yielded median DNA concentrations of 2.82 (tumor) and 4.34 (lymph node) with DIN of 1.60, superior to standard protocol [17].

Visualization of Methodologies

Diagram 1: Electric Field DNA Extraction Workflow

Diagram 2: MAG Quality Assessment Pipeline

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for DNA Extraction Integrity

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K | Enzymatic digestion of proteins | Optimal concentration: 600 AU/L; Extended digestion (16 hours) improves FFPE DNA yield [12] [17] |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelating agent, nuclease inhibitor | Use in extraction buffers to prevent enzymatic DNA degradation [14] |

| CTAB (Cetyl Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide) | Surfactant for plant extraction | Separates polysaccharides from DNA in plant tissues [16] |

| PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | Polyphenol binding | Essential for plant DNA extraction to remove inhibitory compounds [13] |

| Magnetic Beads | DNA binding and purification | High-throughput processing; optimized chemistries available for different sample types [13] |

| TE Buffer (Tris-EDTA) | DNA storage and elution | Optimal pH 8.5 for DNA stability; used in electric field extraction protocols [12] |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic detergent for lysis | Final concentration 0.08 g/mL for saliva viscosity reduction [12] |

| Silica Columns | DNA binding matrix | Standard in commercial kits; potential for contaminant carryover in plant samples [16] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the critical thresholds for MAG quality in publication? A: For bacterial MAGs, aim for >50% completeness with <10% contamination. High-quality drafts require ≥90% completeness, ≤5% contamination, with complete rRNA genes and ≥18 tRNAs. These standards are based on analysis of 4,021 closed genomes showing 94% have <10% redundancy [5] [18].

Q2: How can I improve DNA yield from low-biomass samples? A: Electric field-induced capture methods can efficiently extract DNA from small volumes (5μL). For swab samples, use two swabs per isolation and extend lysis time. Consider increasing FFPE sections from 1 to 4-6 sections with extended proteinase K digestion [12] [13] [17].

Q3: What preservation methods best maintain DNA integrity for metagenomics? A: Flash freezing in liquid nitrogen with -80°C storage is optimal. For field collection, chemical preservatives or specialized stabilization media prevent degradation. Blood samples can be refrigerated up to one week, while plant tissue requires freezing or desiccation [16].

Q4: How does DNA extraction method impact MAG completeness? A: Methods that cause shearing or fragmentation create assembly challenges. Electric field extraction preserves longer fragments. Mechanical homogenization must balance efficient lysis with DNA preservation—overly aggressive processing causes fragmentation that manifests as reduced MAG completeness [12] [14].

Q5: What tools are available for automated MAG quality assessment? A: CheckM assesses completeness/contamination using single-copy marker genes. MAGISTA uses alignment-free distance distributions. MAGqual provides a Snakemake pipeline for MIMAG standard compliance, generating comprehensive quality reports [20] [19].

Selecting the appropriate sequencing technology is a critical first step in metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) research that fundamentally impacts genome completeness, contamination levels, and downstream biological interpretations. The choice between short-read (Illumina, Ion Torrent) and long-read (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) technologies involves balancing multiple factors including project goals, sample type, budget, and bioinformatic considerations. This guide provides a structured framework to help researchers navigate these decisions and troubleshoot common issues that arise from technology selection.

Technical Comparison: Short-Read vs. Long-Read Sequencing

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of short-read and long-read sequencing technologies

| Parameter | Short-Read (NGS) | Long-Read (TGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 50-300 bp [21] | 5,000-30,000+ bp [21] |

| Accuracy | High (Q30+), ~99.9% [21] | Variable: PacBio HiFi >99.9% [21], ONT improving [22] |

| DNA Input | Low (ng scale) [23] | Higher quantity/quality required [23] |

| Cost per Gb | Lower | Higher |

| Primary Strengths | High accuracy, low input DNA, established protocols [23] | Resolves repeats, structural variants, haplotype phasing [22] |

| Main Limitations | Struggles with repetitive regions, complex genomes [23] | Historically higher error rates, lower throughput [23] |

| Best Applications | High-coverage sequencing, variant calling, low-biomass samples | De novo assembly, complex regions, structural variants [22] |

Table 2: Impact on metagenome-assembled genome quality metrics

| Quality Metric | Short-Read Impact | Long-Read Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Completeness | Often incomplete, especially in repetitive regions [23] | More complete genomes, spans repetitive regions [23] |

| Contamination | Binning errors due to fragmented assemblies | More accurate binning from longer contigs |

| Functional Inference | Underestimates functional capacity [24] | More complete functional profiles [24] |

| Mobile Elements | Frequently misses viruses, plasmids [23] | Better recovery of mobile genetic elements [23] |

| Strain Resolution | Limited by read length | Improved through longer haplotype blocks |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Poor Genome Completeness in MAGs

Q: My metagenome-assembled genomes show low completeness scores (<90%) despite adequate sequencing depth. What could be causing this and how can I address it?

A: Low genome completeness typically stems from technology limitations or sample-specific challenges:

- Sequencing Technology Mismatch: Short-read technologies systematically fail to assemble repetitive regions, including ribosomal RNA operons, transposons, and integrated viral elements [23]. This creates artificial gaps in genomes that reduce completeness scores.

Solution: Implement hybrid assembly approaches or supplement with long-read data. Studies show long-read sequencing specifically recovers the "missing" 5-30% of genomic content that short-read approaches consistently fail to assemble [23].

Coverage Inconsistency: Low-abundance community members may not achieve sufficient coverage for complete assembly regardless of technology.

Solution: Perform sequencing depth calculations specific to your community complexity. For highly diverse environments like soil, >50Gbp of data may be required for adequate coverage of rare taxa.

DNA Quality Issues: Degraded DNA or contaminants can create biases in library preparation and sequencing.

- Solution: Verify DNA quality using multiple metrics (Qubit, Nanodrop, fragment analyzer). For long-read sequencing, high molecular weight DNA is essential [2].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Technology-Specific Completeness Bias

- Subsample Analysis: Take a complete reference genome and computationally fragment it to simulate short-read (150bp) and long-read (5kb) datasets.

- Assembly Comparison: Assemble both datasets using appropriate assemblers (metaSPAdes for short-read, metaFlye for long-read).

- Completeness Calculation: Compare BUSCO scores and CheckM completeness between assemblies.

- Functional Impact Assessment: Annotate both assemblies with DRAM or PROKKA to quantify missing metabolic pathways in the short-read assembly [24].

This protocol reveals that genome completeness directly impacts functional inference, with 70% complete MAGs showing approximately 15% lower functional fullness compared to 100% complete genomes [24].

Problem 2: High Contamination in Genome Bins

Q: My genome bins show high contamination metrics (>10%), but I've followed standard quality control procedures. What are potential sources of this contamination?

A: Contamination can originate from wet lab and computational sources:

- Reference Database Issues: Public databases contain mislabelled sequences and contaminants that propagate through analyses [25]. Taxonomic misannotation affects approximately 3.6% of prokaryotic genomes in GenBank and 1% in RefSeq [25].

Solution: Use curated databases like GTDB or perform additional filtering of public databases before analysis. Implement database testing with known control samples to identify false positives.

Sample Cross-Contamination: During library preparation, samples can cross-contaminate, especially in high-throughput workflows.

Solution: Include negative controls (water blanks) in every library preparation batch. Sequence these controls and subtract contaminant reads found in controls from your samples.

Human DNA Contamination: Host DNA can be particularly problematic in host-associated metagenomes.

Solution: Remove human reads by mapping to the human reference genome before assembly. Be aware that Y-chromosome fragments often mismap to bacterial genomes, creating sex-associated contamination artifacts [26].

Bioinformatic Binning Errors: Short, ambiguous contigs from short-read assemblies are difficult to bin accurately.

- Solution: Long-read sequencing produces longer contigs that improve binning accuracy. Tools like SemiBin2 show better performance with long-read assemblies [23].

Experimental Protocol: Contamination Source Identification

- Negative Control Sequencing: Include extraction blanks and library preparation blanks in your sequencing run.

- Contamination Profiling: Use Kraken2 to taxonomically classify all reads, identifying potential contaminants [26].

- Metadata Correlation: Test for associations between contaminant abundance and metadata (sequencing plate, DNA extraction kit lot, technician) [26].

- Sex-Linked Artifact Check: For human-associated samples, verify that bacterial abundances aren't correlated with sample sex, which indicates Y-chromosome mismapping [26].

Problem 3: Inadequate Resolution of Complex Genomic Regions

Q: I'm studying microbial communities where mobile genetic elements and repetitive regions are biologically important, but my current methods are failing to resolve these regions. What approaches can improve resolution?

A: Complex genomic regions represent a fundamental limitation of short-read technologies:

- Mobile Genetic Elements: Viruses, plasmids, and defense islands are frequently missed by short-read assemblies due to their repetitive nature and strain-level variation [23] [27].

Solution: Long-read sequencing has been shown to recover 4.83-21.7× more viral genomes compared to short-read approaches alone [27]. For virome studies, combine multiple assemblers (MEGAHIT for short-read, metaFlye for long-read, hybridSPAdes for hybrid) as they recover complementary sets of viral genomes [27].

Repetitive Elements: Tandem repeats, transposons, and rRNA gene clusters collapse in short-read assemblies.

Solution: Long-read technologies excel at spanning repetitive elements. PacBio HiFi provides high accuracy for resolving complex haplotypes, while Oxford Nanopore provides the longest reads for spanning massive repeats [22].

Structural Variation: Large-scale genomic rearrangements and copy number variants are invisible to short-read approaches.

- Solution: Implement specialized structural variant callers designed for long-read data (cuteSV, pbsv, Sniffles) [22].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Complex Region Recovery

- Spike-In Controls: Add a known virus or plasmid to your sample before DNA extraction.

- Multi-Technology Sequencing: Sequence the same sample with both short-read and long-read technologies.

- Assembly Comparison: Assemble each dataset separately and compare recovery of the spike-in element.

- Validation: Use PCR and Sanger sequencing to validate the structure of problematic regions identified in the assemblies.

Decision Framework: Technology Selection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table 3: Key reagents and tools for sequencing technology selection and troubleshooting

| Category | Item | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Quality Assessment | Qubit Fluorometer | Quantifies DNA concentration; more accurate for NGS than UV spectrophotometry [28] |

| Fragment Analyzer/ Bioanalyzer | Assesses DNA size distribution; critical for long-read sequencing success [2] | |

| Library Preparation | PacBio SMRTbell Prep | Library prep for PacBio long-read sequencing; requires high molecular weight DNA |

| ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit | Library prep for Nanopore sequencing; more flexible DNA input requirements | |

| Illumina DNA Prep | Library prep for Illumina short-read sequencing; compatible with low input DNA | |

| Control Materials | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | Mock community for validating sequencing and assembly performance [24] |

| Lambda Phage DNA | Positive control for library preparation; also common contaminant [26] | |

| Computational Tools | CheckM2 [24] | Assesses MAG completeness and contamination using marker genes |

| metaFlye [23] | Long-read metagenomic assembler; effective for complex communities | |

| MEGAHIT [27] | Efficient short-read metagenomic assembler for diverse environments | |

| SemiBin2 [23] | Binning tool that performs better with long-read assemblies |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can I combine short-read and long-read data if I have limited budget for comprehensive long-read sequencing?

A: Yes, targeted hybrid approaches are effective. Sequence most samples with short-read technology for breadth, and select subset representatives for deep long-read sequencing. Hybrid assembly tools like OPERA-MS and hybridSPAdes can integrate these datasets [27]. This balanced approach provides cost-effective access to long-read benefits while maintaining sample size.

Q: How has long-read accuracy improved in recent years, and does it now match short-read fidelity?

A: Significant improvements have been made. PacBio HiFi reads now achieve Q30 (99.9%) accuracy, comparable to short-read technologies [21]. Oxford Nanopore has also dramatically improved basecalling accuracy through new models (Dorado) and chemistry updates. However, accuracy profiles differ - PacBio errors are random while ONT errors may be systematic. For clinical applications requiring maximum reproducibility, consider these differences in your technology selection [22].

Q: What are the specific advantages of long-read sequencing for metagenome-assembled genomes?

A: Long-read sequencing provides three key advantages for MAG generation: (1) Improved contiguity - contigs are 10-100× longer, simplifying binning and reducing fragmentation [23]; (2) Better repetitive element resolution - spans rRNA operons, transposons, and viral integration sites that collapse in short-read assemblies [23]; (3) More complete functional profiles - recovers metabolic pathways that are artificially truncated in short-read MAGs [24].

Q: How does sequencing technology choice impact functional inference from MAGs?

A: Technology choice directly impacts functional predictions. Research shows that 70% complete MAGs (typical for short-read assemblies) underestimate functional capacity by approximately 15% compared to complete genomes [24]. This bias affects all metabolic domains, with nucleotide metabolism and secondary metabolite biosynthesis being most severely impacted. The relationship between completeness and functional fullness varies by bacterial phylum, making cross-phylum comparisons particularly problematic with incomplete MAGs [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the definitive standards for a high-quality MAG, and why do they matter for my research conclusions? Adhering to standardized quality thresholds is fundamental for ensuring the biological validity of your findings. The field widely accepts the "Minimum Information about a Metagenome-Assembled Genome" (MIMAG) standard, which defines a high-quality MAG as having >90% completeness and <5% contamination [6]. These metrics are typically assessed using tools that check for the presence of universal single-copy marker genes.

Using MAGs that fall below these standards can severely bias your research:

- Ecological Inferences: In wastewater studies, high-quality MAGs were crucial for accurately identifying microbial hosts of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs). Shifts in ARG-host associations between treatment stages were only discernible with a reliable, genome-resolved approach [29].

- Clinical Inferences: A study on Klebsiella pneumoniae found that over 60% of MAGs from gut samples belonged to new sequence types missed by isolate collections. Using low-quality MAGs would have failed to reveal this vast, uncharacterized diversity and its potential implications for public health surveillance and understanding pathogen evolution [11].

FAQ 2: My short-read assemblies are missing key genomic regions. What is the cause and solution? This is a common limitation of short-read sequencing, especially in complex environments like soil. Research has identified that low coverage and high sequence diversity (strain heterogeneity) are the two primary factors causing short-read assemblers to fail in these regions [23].

The "missed" regions are often biologically significant, including:

- Integrated viruses and defense system islands [23].

- Mobile genetic elements like plasmids [23] [2].

- Biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [2] [30].

Solution: Complement your data with long-read sequencing. Long-read technologies (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) generate reads that are thousands of bases long, allowing them to span repetitive and complex regions that fragment short-read assemblies. This has been proven to improve assembly contiguity and the recovery of variable genome regions [23] [30].

FAQ 3: How does the choice of sequencing technology directly impact the quality of my MAGs and downstream analysis? The sequencing technology choice is a critical upstream decision that dictates downstream outcomes. The table below compares their key characteristics.

Table 1: Impact of Sequencing Technology on MAG Quality and Research Outcomes

| Feature | Short-Read (e.g., Illumina) | Long-Read (e.g., PacBio, Nanopore) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical MAG Quality in Complex Samples | Often fragmented; struggles with repeats and strain variation [23]. | Higher contiguity; more complete genes and operons [23] [30]. |

| Recovery of Variable Regions | Poor recovery of mobile elements, viral sequences, and defense islands [23]. | Superior recovery of plasmids, integrated viruses, and BGCs [23] [2]. |

| Impact on Diversity Estimates | Can underestimate true phylogenetic diversity and miss novel lineages [11] [30]. | Expands known microbial diversity; uncovers novel genera and species [11] [30]. |

| Data Requirement for Complex Samples | Requires extreme depth (Terabases) for modest MAG yield from soil [30]. | More cost-effective MAG recovery from complex environments like soil at ~100 Gbp/sample [30]. |

FAQ 4: What are the concrete risks of using MAGs with elevated contamination levels? Using contaminated MAGs (where contigs from multiple organisms are incorrectly binned together) leads to false functional assignments and erroneous biological conclusions. Specifically:

- Misattribution of Gene Function: A virulence factor from a contaminating organism could be incorrectly assigned to your MAG of interest, leading to false conclusions about its pathogenic potential [11].

- Inflated Metabolic Capabilities: The metabolic pathway of your target organism may appear artificially complete or may contain enzymes from a different organism, distorting ecological role inferences [2].

- Compromised Taxonomic Classification: Contamination can confuse taxonomic classifiers, leading to incorrect phylogenetic placement [6].

FAQ 5: Where can I find curated, high-quality MAGs for comparative analysis? Publicly available repositories provide access to rigorously vetted MAGs. A key resource is MAGdb, a comprehensive database containing 99,672 high-quality MAGs from clinical, environmental, and animal samples, all manually curated to meet MIMAG standards [6]. These genomes are linked to their source metadata, enabling robust comparative studies.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Incomplete MAGs from Complex Metagenomes

Issue: Your assembled MAGs have low completeness scores, failing to meet the >90% high-quality threshold, which limits their utility for robust ecological or clinical inference.

Diagnosis: This is frequently encountered in highly diverse environments like soil or sediment, where microbial complexity leads to fragmented assemblies, especially with short-read technologies [30].

Solution: Implement a Long-Read Sequencing and Advanced Binning Strategy

Step-by-Step Protocol: The mmlong2 Workflow for Complex Terrestrial Samples This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully recovered 15,314 novel species from soil and sediment using deep long-read sequencing and a sophisticated binning workflow [30].

- DNA Extraction: Use a method that yields high-molecular-weight DNA to preserve long fragments suitable for long-read sequencing.

- Sequencing: Perform deep long-read sequencing (e.g., ~100 Gbp per sample) on a platform like Oxford Nanopore [30].

- Assembly: Assemble the reads using a long-read assembler like metaFlye.

- Binning with mmlong2: Employ the mmlong2 workflow, which enhances MAG recovery through several key steps [30]:

- Circular MAG (cMAG) Extraction: Identify and extract circular contigs as separate, high-confidence bins.

- Differential Coverage Binning: Use read mapping information from multiple related samples to improve bin separation.

- Ensemble Binning: Run multiple binning tools on the same assembly and integrate the results.

- Iterative Binning: Bin the metagenome multiple times to capture sequences missed in initial rounds.

The following workflow diagram outlines this process:

Diagram 1: Workflow for MAG recovery from complex samples.

Problem 2: Contamination from Host DNA or Multiple Organisms

Issue: Your MAGs have high contamination (>5%), meaning they contain genetic material from co-assembled organisms or host DNA, risking false functional predictions.

Diagnosis: This is a major concern in host-associated samples (e.g., gut content) or when using aggressive binning parameters that incorrectly group contigs.

Solution: Apply Rigorous Pre- and Post-Assembly Filtration

Experimental Protocol: Genome-Resolved Metagenomics for Host-Associated Samples

- Sample Preparation:

- Bioinformatic Filtering:

- Pre-assembly: Map sequencing reads to the host genome (e.g., human, mouse) and remove all matching reads before assembly.

- Post-assembly: Classify assembled contigs using tools like GTDB-Tk against a reference database. Contigs classified as non-target domains (e.g., Eukaryota, Archaea in a bacterial bin) should be removed from the MAG.

- Bin Refinement: Use bin refinement tools (e.g., within metaWRAP) to identify and remove contaminating contigs from your bins based on sequence composition and coverage depth discrepancies [6].

Problem 3: Failure to Assemble Variable or Repetitive Genomic Regions

Issue: Your MAGs are fragmented and miss biologically critical elements like virulence genes, antimicrobial resistance genes, or biosynthetic gene clusters.

Diagnosis: Short-read assemblers cannot resolve long repetitive sequences or regions of high strain-level variation, leading to assembly breaks and gene loss [23].

Solution: Use Hybrid Sequencing or Long-Read-Only Approaches

Experimental Protocol: Targeted Recovery of Variable Genomic Regions

- Sequencing Strategy:

- Option A (Hybrid): Generate both deep short-read data (for base accuracy) and long-read data (for scaffold continuity) from the same sample. The short reads can be used to polish the long-read assembly [31].

- Option B (Long-Read only): Use high-accuracy long-reads (e.g., PacBio HiFi) which provide both length and accuracy, simplifying the assembly process [23].

- Focused Assembly Analysis:

The diagram below illustrates why long-reads are superior for this task:

Diagram 2: Long-reads resolve complex genomic regions.

Table 2: Key Resources for High-Quality MAG Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function in MAG Research |

|---|---|---|

| metaFlye [23] [30] | Software | A long-read metagenomic assembler for reconstructing contiguous sequences from complex communities. |

| SemiBin2 [23] | Software | A metagenomic binning tool that uses semi-supervised learning to recover high-quality MAGs from complex environments. |

| GTDB-Tk [6] | Software | A toolkit for assigning objective taxonomic classifications to MAGs based on the Genome Taxonomy Database. |

| MAGdb [6] | Database | A curated repository of high-quality MAGs for comparative analysis and contextualizing new findings. |

| Canu & Flye [31] | Software | Robust long-read assemblers used in reproducible workflows for both prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes. |

| PacBio HiFi/ONT | Technology | Long-read sequencing platforms essential for resolving repetitive regions and obtaining complete genes. |

| CheckM / CheckM2 | Software | Standard tools for assessing MAG quality by estimating completeness and contamination using marker genes. |

Building Better MAGs: A Methodological Pipeline from Sample to Genome

Optimal Sample Handling and Storage Protocols to Minimize Degradation

In metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) research, sample integrity is the foundation of data reliability. The pre-analytical phase represents the most vulnerable stage of laboratory testing, with improper handling potentially compromising genomic completeness and increasing contamination risk [32]. This guide provides evidence-based troubleshooting protocols to maintain nucleic acid integrity from collection through storage, specifically addressing challenges in MAG generation and analysis.

Fundamental Principles of Sample Integrity

FAQ: What are the primary mechanisms of DNA degradation in biological samples?

DNA degradation occurs through several chemical and physical pathways that fragment nucleic acids and compromise downstream analyses [14]:

- Oxidation: Caused by exposure to reactive oxygen species, heat, or UV radiation, leading to modified nucleotide bases and strand breaks.

- Hydrolysis: Results from water molecules breaking phosphodiester bonds in the DNA backbone, causing depurination and fragmentation.

- Enzymatic breakdown: Nucleases naturally present in biological samples rapidly degrade nucleic acids if not properly inactivated.

- Mechanical shearing: Overly aggressive homogenization or pipetting creates fragment sizes unsuitable for sequencing.

FAQ: How does sample degradation specifically impact MAG quality and completeness?

Degraded DNA directly reduces MAG quality by creating fragmented sequences that hamper assembly algorithms [33]. Short fragments cannot span repetitive regions, leading to:

- Genome fragmentation into more contigs

- Reduced completeness scores

- Increased contamination from mis-binned sequences

- Loss of strain variation data Incomplete MAGs derived from degraded templates provide unreliable metabolic reconstructions and taxonomic classifications [2].

Troubleshooting Common Sample Handling Issues

FAQ: Our team observes inconsistent MAG completeness scores between sample batches. Could pre-analytical variables be responsible?

Yes, this pattern frequently originates from inconsistent handling practices. Key variables to standardize include:

- Time-to-preservation: Maximize nucleic acid integrity by minimizing this interval

- Freeze-thaw cycles: Implement single-use aliquots to avoid repetitive cycling [32]

- Homogenization intensity: Standardize mechanical disruption parameters across batches

- Storage temperature fluctuations: Monitor and document storage conditions continuously

FAQ: We suspect bacterial contamination in our samples. How does this affect MAG analysis, and how can we prevent it?

Environmental contamination significantly distorts MAG analyses by introducing foreign genomic material that can be mis-binned as novel taxa [32]. Prevention strategies include:

- Sterile technique: Use DNA-free containers and sterile tools during collection

- Environmental controls: Sequence extraction blanks to identify contaminant signatures

- Spatial separation: Physically separate sample processing from amplification areas

- Verification: Implement 16S rRNA screening to detect bacterial introduction [32]

Sample Storage & Preservation Protocols

Temperature Guidelines for Various Sample Types

Table 1: Evidence-based storage conditions for different biological materials

| Sample Type | Optimal Temperature | Preservation Method | Maximum Recommended Storage | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh Tissue | -80°C | Flash freezing in liquid N₂ | 2-5 years | Rapid freezing prevents ice crystal formation |

| Plasma/Serum | -80°C | With appropriate anticoagulants | 1-3 years | Multiple freeze-thaw cycles drastically reduce stability [32] |

| Bacterial DNA | -80°C | TE buffer (pH 8.0) | 5+ years | EDTA chelates Mg²⁺ inhibiting DNases |

| Gut Content | -80°C or liquid N₂ | RNAlater or specialized buffers | Varies | Immediate freezing critical for microbiome integrity [2] |

| Extracted DNA | -20°C | Low TE buffer, neutral pH | 10+ years | Avoid acidic conditions that promote hydrolysis |

FAQ: What is the impact of multiple freeze-thaw cycles on DNA quality for MAG generation?

Repeated freeze-thaw cycles progressively fragment DNA, creating shorter segments that hamper genome assembly. Research demonstrates:

- Concentration reduction: Up to 25% DNA loss after 4 freeze-thaw cycles in plasma samples [32]

- Fragment size reduction: Sheared DNA produces contigs below 10kb, insufficient for quality MAGs

- Solution: Aliquot samples before initial freezing; record thaw history for quality control

Experimental Protocols for Quality Assessment

Protocol 1: Quantitative PCR for DNA Quality Assessment

This protocol evaluates DNA degradation levels before metagenomic sequencing [33].

Materials:

- SD quants or similar qPCR assay targeting multiple fragment lengths

- Quantitative PCR instrument

- DNA samples and appropriate dilution buffers

Methodology:

- Dilute DNA extracts to working concentration using low TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0)

- Perform qPCR with targets of different sizes (e.g., 69 bp and 143 bp mitochondrial targets)

- Calculate degradation index (DI) = DNA amount (long target) / DNA amount (short target)

- Interpret results: DI < 1.0 indicates degradation; lower values suggest more severe fragmentation

Troubleshooting:

- If DI values exceed 1.5, consider inhibition issues rather than degradation

- If amplification fails for long targets but succeeds for short ones, sample is severely degraded

Protocol 2: UV-C Degradation for Method Validation

Artificially degraded DNA controls help validate MAG protocols with challenged samples [33].

Materials:

- UV-C irradiation unit (254 nm wavelength)

- DNA samples in microtubes

- Protective equipment for UV exposure

Methodology:

- Prepare DNA aliquots (10-20 μL) at concentrations between 1-14 ng/μL

- Position samples ~11 cm from UV-C light source

- Expose for timed intervals (0-5 minutes)

- Remove aliquots at 30-second intervals for degradation gradient

- Assess degradation using qPCR and STR profiling

Applications:

- Validate performance of new marker panels with degraded DNA

- Establish quality thresholds for sample acceptance in MAG projects

- Optimize assembly parameters for fragmented sequences

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential reagents for maintaining sample integrity in MAG research

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Notes | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDTA | Chelates divalent cations; inhibits nucleases | DNA extraction buffers; storage solutions | Can inhibit PCR if not properly removed; balance concentration for demineralization vs. inhibition [14] |

| RNAlater & Similar Buffers | Stabilizes nucleic acids; arrests degradation | Field collections; temporary storage | Enables room temperature storage for days/weeks; particularly valuable for gut microbiome studies [2] |

| Proteolytic Enzymes | Digests cellular proteins; inactivates nucleases | Tissue lysis; DNA extraction | Optimization required to balance complete lysis with DNA preservation |

| Antioxidants | Reduces oxidative damage | Long-term storage; extraction buffers | Protects against ROS-induced damage during processing |

| Specialized Beads (ceramic, steel) | Mechanical disruption | Homogenization of tough samples | Bead selection critical: ceramic for standard tissues, steel for bacterial cells [14] |

Advanced Preservation Technologies

FAQ: What novel preservation methods show promise for metagenomic studies?

Emerging technologies address limitations of conventional freezing:

- Chemical stabilization: Advanced preservatives that maintain nucleic acid integrity at room temperature

- Sample dehydration: DNA-based analyses increasingly utilize dry storage, enabling room temperature preservation with reduced costs [34]

- Automated cryopreservation: Robotic systems minimize handling errors and improve reproducibility

- RFID tracking: Integrated monitoring maintains chain of custody and documents storage conditions [34]

Quality Control Implementation

Integrated Workflow for Sample Quality Assurance

Implementing robust quality control checkpoints throughout the workflow enables early detection of compromised samples before significant resources are invested in sequencing and analysis. This integrated approach includes:

- Pre-extraction assessment: Visual inspection and documentation

- Post-extraction quantification: Spectrophotometric and fluorometric methods

- Quality verification: Fragment analysis, qPCR amplification efficiency

- Process validation: Include control samples with known characteristics

Optimal sample handling is not merely a preliminary step but a fundamental determinant of success in MAG research. By implementing these standardized protocols, troubleshooting guides, and quality control measures, researchers can significantly enhance genomic recovery from complex samples. The reproducibility of MAG studies directly correlates with consistency in these pre-analytical phases, ultimately determining the accuracy and biological relevance of genomic insights derived from microbial communities.

Hybrid Sequencing Approaches to Overcome Assembly Gaps and Improve Continuity

Core Concepts: Why Use a Hybrid Sequencing Approach?

What is hybrid genome assembly and what fundamental problem does it solve?

Hybrid genome assembly is a bioinformatics method that utilizes multiple sequencing technologies—typically combining short-read (e.g., Illumina) and long-read (e.g., Oxford Nanopore or PacBio) data—to reconstruct a genome from fragmented DNA sequences [35]. The fundamental problem it solves is the inherent limitation of using any single technology: short-reads are highly accurate but produce fragmented assemblies, while long-reads span repetitive regions but have higher raw error rates [36] [37]. This approach synergistically leverages the high accuracy of short-reads with the long-range connectivity of long-reads to generate more complete and contiguous genomic reconstructions [36].

What are the primary technical advantages of a hybrid approach over long-read-only or short-read-only strategies?

The primary advantage is the creation of a more complete and accurate genome assembly by using each technology's strengths to compensate for the other's weaknesses. Specifically:

- Overcomes Repetitive Regions: Long-reads can span complex, repetitive DNA segments (e.g., centromeres, telomeres, transposable elements) that short-reads cannot resolve, thereby "bridging" gaps in the assembly [36] [35].

- Improves Base-Level Accuracy: The high base-level accuracy of short-read data is used to computationally "polish" and correct errors (such as small insertions and deletions) that are common in raw long-read data [36] [37]. One study on a bird genome found that this hybrid correction achieved more accurate assemblies than using either technology alone [37].

- Optimizes Cost-Effectiveness: Hybrid sequencing can reduce the financial and computational burden of generating a high-quality assembly by lowering the required coverage of expensive long-read data, making it a practical solution for many labs [36].

Table 1: Comparison of Sequencing Strategies for Genome Assembly

| Feature | Short-Read Only | Long-Read Only | Hybrid Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 50–300 bp [36] | 5,000–100,000+ bp [36] | Combines both |

| Per-Read Accuracy | High (≥99.9%) [36] | Moderate (85–98% raw) [36] | High (≥99.9%; after correction) [36] |

| Best for Repetitive Regions | Poor; leads to fragmentation [36] | Excellent; spans repeats [36] | Excellent with high accuracy |

| Cost per Base | Low [36] | Higher [36] | Moderate [36] |

| Typical Assembly Result | Fragmented assemblies, gaps likely [36] | Near-complete, but may contain small errors [36] | Highly contiguous and accurate assemblies [36] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Computational Challenges

How do I troubleshoot poor hybrid assembly metrics (e.g., low N50, high contig count)?

Poor assembly continuity often stems from issues with input data quality or computational strategy. Follow this diagnostic workflow to identify and correct the problem.

- Assess Long-Read Data: The length and coverage of long-reads are critical for assembly continuity. Verify that the long-read N50 is sufficiently high to span common repeats in your target genome. Additionally, ensure you have adequate coverage (often ≥50X for long-reads) for robust assembly [36]. If metrics are low, consider increasing sequencing depth or improving DNA extraction to obtain higher molecular weight DNA.

- Inspect Library Quality: A common wet-lab failure is the presence of adapter dimers or an unexpected fragment size distribution in your final library [28]. Check the electropherogram (e.g., from a BioAnalyzer) for a sharp peak around 70–90 bp, which indicates adapter dimers. This can be caused by suboptimal adapter-to-insert molar ratios or inefficient purification [28]. Re-optimize ligation conditions and use appropriate bead-based cleanup ratios to remove these artifacts.

- Review Computational Pipeline: The choice of assembly software significantly impacts results. A 2025 benchmarking study identified that certain hybrid assemblers, when combined with specific polishing schemes, outperformed others [38]. The study found that the Flye assembler performed particularly well, especially when long-reads were first error-corrected with tools like Ratatosk, followed by polishing with Racon and Pilon [38]. Ensure you are using a modern, benchmarked pipeline.

My assembly shows high duplication of BUSCO genes. What does this indicate and how can I resolve it?

A high duplication of BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) genes is a key indicator of assembly redundancy and potential haplotypic duplication [37]. This occurs when the assembler fails to collapse heterozygous regions or recent duplications into a single locus, instead representing them as separate contigs.

- Primary Cause: For diploid organisms, this often reflects the assembler's difficulty in handling high levels of heterozygosity (natural differences between the two copies of chromosomes) [36]. The assembler may interpret the two different haplotypes as separate genomic regions.

- Solutions:

- Utilize Haplotype-Aware Assemblers: Employ modern assemblers like

hifiasmorverkkothat are specifically designed to separate haplotypes during assembly, resulting in a more accurate primary assembly and a separate haplotype-resolved assembly [39]. - Apply Haplotypic Purging: Tools like

Purge_Dupscan be used post-assembly to identify and remove redundant contigs that likely represent overlapped haplotypes or duplicates. - Leverage Reference-Guided Tools: For population-scale projects, tools like RAGA (Reference-Assisted Genome Assembly) have been shown to effectively reduce genome redundancy in plant populations while improving contiguity [39].

- Utilize Haplotype-Aware Assemblers: Employ modern assemblers like

What are the best practices for preventing contamination in MAGs from complex samples like soil?

Preventing contamination in Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) from high-complexity environments like soil begins with rigorous wet-lab procedures and is reinforced bioinformatically.

- Wet-Lab Controls:

- Sample Handling: Use sterile tools and DNA-free containers. For gut content or soil, store samples at -80°C immediately or use nucleic acid preservation buffers (e.g., RNAlater) to prevent microbial community shifts and DNA degradation [2].

- DNA Extraction: Choose extraction kits validated for environmental samples to maximize lysis of tough cells while minimizing co-extraction of contaminants like humic acids, which can inhibit downstream enzymes [28] [2].

- Bioinformatic Cleaning:

- Critical Step: Always run your final assembly through the NCBI's Foreign Contamination Screening (FCS) tool before public deposition. This is a standard practice for identifying and removing common contaminants [37].

- Genome Quality Metrics: Use established criteria to classify MAGs. Check for abnormal coding densities (e.g., <75%) which can indicate problematic assemblies or contamination [30]. Rely on completeness and contamination estimates from tools like

CheckMandBUSCO.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: A Standard Workflow for Hybrid Genome Assembly and Polishing

This protocol outlines a general workflow for eukaryotic genome assembly, based on benchmarking studies and successful applications [38] [37].

- DNA Extraction & QC: Isolate high-molecular-weight (HMW) genomic DNA. Confirm integrity via pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and quantify using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit).

- Library Preparation & Sequencing:

- Long-Read Library: Prepare a library from HMW DNA for either Oxford Nanopore (e.g., PromethION) or PacBio (HiFi) sequencing. Target a coverage of >50X.

- Short-Read Library: Prepare a paired-end Illumina library (e.g., NovaSeq X Plus) from the same sample. Target a coverage of >30X for effective polishing.

- Basecalling & QC: Convert raw signal data to FASTQ files. Use

NanoPlot(for Nanopore) orpbccs(for PacBio HiFi) for initial quality assessment. - Error Correction of Long Reads (Optional but Recommended): Correct raw long-reads using the high-accuracy short-reads. Tools like

Ratatoskhave been benchmarked for this purpose and can improve downstream assembly [38]. - Hybrid De Novo Assembly: Perform the primary assembly using a hybrid or long-read assembler.

- Recommended Tool:

Flyehas been shown to outperform other assemblers in benchmarks, particularly with pre-corrected reads [38]. - Command (example):

flye --nano-corr corrected_reads.fastq --genome-size 1g --out-dir flye_assembly --threads 32

- Recommended Tool:

- Assembly Polishing: This step is critical for correcting small indels.

- First Polish with Long Reads: Use

Raconfor one or more rounds of long-read-based polishing. - Final Polish with Short Reads: Use

Pilonwith the Illumina reads for a final, high-accuracy polish. The benchmarked optimal approach is two rounds ofRaconfollowed byPilon[38].

- First Polish with Long Reads: Use

- Assembly QC: Evaluate the final assembly using

QUAST(contiguity),BUSCO(completeness), andMerqury(quality value) [38].

Protocol: The mmlong2 Workflow for MAG Recovery from Complex Terrestrial Samples

For highly complex samples like soil, a specialized workflow is required. The mmlong2 pipeline, which recovered over 15,000 novel species from soil and sediment, provides a robust framework [30].

- Deep Long-Read Sequencing: Perform deep Nanopore sequencing (~100 Gbp per sample) to ensure sufficient coverage for low-abundance species [30].

- Metagenome Assembly and Polishing: Assemble the metagenome using a long-read assembler. Contigs are then polished.

- Eukaryotic Contig Removal: Filter out contigs of eukaryotic origin to focus on prokaryotic MAGs.

- Iterative, Multi-Feature Binning: This is the core innovation.

- Circular MAG Extraction: Identify and extract circular elements (plasmids, small chromosomes) as separate bins.

- Differential Coverage Binning: Use read mapping information from multiple related samples to bin contigs based on co-abundance patterns.

- Ensemble Binning: Run multiple binning algorithms (e.g.,

MetaBAT2,MaxBin2) on the same metagenome and aggregate the results. - Iterative Binning: Repeat the binning process on the unbinned reads/contigs from the first round to recover additional MAGs. This step alone recovered 14% of the total MAGs in the Microflora Danica project [30].

- Dereplication and Quality Control: Cluster the MAGs at a species level (e.g., 95% ANI) and assess quality using standard metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Resources for Hybrid Sequencing Projects

| Category | Item / Tool | Specific Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | High-Molecular-Weight (HMW) DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., Qiagen MagAttract, Nanobind) | Provides long, intact DNA strands essential for long-read library prep. |

| Nucleic Acid Preservation Buffers (e.g., RNAlater, OMNIgene.GUT) | Stabilizes community DNA/RNA for later extraction, critical for field or clinical samples [2]. | |

| Size Selection Beads (e.g., AMPure, Solid Phase Reversible Immobilization (SPRI) beads) | Purifies and selects for DNA fragments of a desired size, removing adapter dimers and small fragments [28]. | |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina (NovaSeq X Plus, etc.) | Generates high-accuracy short-reads for polishing and error correction [36]. |

| Oxford Nanopore (PromethION) / PacBio (Revio, Sequel II) | Generates long-reads for spanning repeats and resolving complex regions [36]. | |

| Bioinformatics Software | Flye (Assembler) | A long-read assembler that benchmarked as a top performer for hybrid assembly [38]. |

| Racon & Pilon (Polishers) | Used in sequence for long-read and subsequent short-read polishing, respectively [38]. | |

| BUSCO / QUAST / Merqury (QC Tools) | Standard tools for assessing assembly completeness, contiguity, and base-level quality [38] [37]. | |

| mmlong2 (Workflow) | A specialized workflow for recovering MAGs from highly complex environments using long-reads [30]. | |

| RAGA (Tool) | A reference-assisted tool for improving population-scale genome assemblies [39]. |

Glossary of Key Terms

- Contig N50: A measure of assembly continuity. It is the length of the shortest contig such that 50% of the total assembly length is contained in contigs of that size or longer. A higher N50 indicates a more contiguous assembly.

- BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs): A tool that assesses the completeness of a genome assembly based on the presence of evolutionarily conserved, single-copy genes.

- MAG (Metagenome-Assembled Genome): A genome reconstructed from complex microbial communities directly from environmental sequencing data, without the need for culturing [2].

- Polishing: The computational process of correcting small errors (SNPs, indels) in a draft genome assembly using the original sequencing reads.

- Read Depth / Coverage: The average number of times a given nucleotide in the genome is represented by sequencing reads. Higher coverage generally leads to more accurate assemblies.

Advanced Assembly Algorithms and Binning Techniques for Strain Deconvolution

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary algorithmic approaches for de novo strain-resolved metagenomic assembly?

Several distinct algorithmic strategies exist for de novo strain resolution:

- De Bruijn Graph with Flow Algorithms: Tools like Haploflow use de Bruijn graphs but employ a novel flow algorithm that uses differential coverage between strains to deconvolute the assembly graph into strain-resolved genomes, without requiring reads to span multiple variable sites [40].

- Assembly Graph with Bayesian Haplotyping: STRONG performs co-assembly and bins contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs). It then extracts subgraphs for single-copy core genes and uses a Bayesian algorithm (BayesPaths) to determine the number of strains, their haplotypes, and their abundances directly on the assembly graph [41].