Navigating the Maze: Strategies for Overcoming Regulatory Complexity in Prokaryotic Gene Cluster Engineering

The engineering of prokaryotic gene clusters holds immense potential for drug discovery and biotechnology, yet its path is fraught with technical and regulatory challenges.

Navigating the Maze: Strategies for Overcoming Regulatory Complexity in Prokaryotic Gene Cluster Engineering

Abstract

The engineering of prokaryotic gene clusters holds immense potential for drug discovery and biotechnology, yet its path is fraught with technical and regulatory challenges. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, synthesizing foundational science, advanced engineering methodologies, optimization tactics, and validation frameworks. We explore the inherent complexity of clusters, from their natural evolution as modular systems to the synthetic biology tools used for their refactoring. Critically, the article addresses the global regulatory landscape, offering strategies for navigating diverse compliance requirements to successfully translate engineered biosynthetic pathways into approved biomedical applications.

Deconstructing Nature's Blueprint: The Structure and Natural Evolution of Prokaryotic Gene Clusters

FAQs: Understanding Prokaryotic Gene Clusters

What is a prokaryotic gene cluster? A prokaryotic gene cluster is a contiguous region of the genome where genes associated with a particular function are located near each other. Sometimes, these clusters contain all the genes necessary and sufficient for a discrete function, such as nutrient scavenging, energy production, chemical synthesis, or environmental sensing [1] [2].

What is the evolutionary advantage of gene clusters? The organization of genes into clusters facilitates the horizontal transfer of complete functions between species. This is evidenced by phylogenetic trees that differ from ribosomal RNA, varying G+C content, and the presence of flanking transposon or integron genes. This allows a mobile element to confer a novel function and a fitness advantage to its host [1] [2].

Why are some gene clusters called "cryptic"? Cryptic gene clusters are those for which there are no known conditions under which the genes are expressed. Homology analysis can predict the general class of molecules they might produce, such as novel antibiotics. These clusters can sometimes be "woken up" by engineering their regulatory circuitry [1] [2].

What are the main challenges in engineering gene clusters? Engineering native gene clusters is often hindered by their inherent regulatory complexity, the need to balance the expression of many genes, and a historical lack of tools to design and manipulate DNA at this scale. Furthermore, transferring a cluster to a new host can fail if the cluster relies on regulatory interactions or host dependencies not present in the new organism [1] [2].

How is synthetic biology advancing gene cluster engineering? Synthetic biology provides a growing toolbox of genetic parts (e.g., promoters, RBS) and devices (e.g., genetic circuits) that enable programmable control. Advances in DNA synthesis and assembly now allow for the construction of large DNA fragments, moving the field toward an era of genome engineering where gene clusters can be refactored, optimized, and mixed-and-matched to create designer organisms [1] [2].

Troubleshooting Guides for Gene Cluster Experiments

Problem: Few or No Transformants After Clustering

After transformation and incubation, few or no colonies are observed on the selective agar plate [3].

| Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal transformation efficiency | Use best practices for competent cells: store at -70°C, avoid freeze-thaw cycles, thaw on ice, and do not vortex. Ensure the transforming DNA is free of contaminants like phenol or ethanol [3]. |

| Suboptimal DNA quality/quantity | For ligated DNA, do not use more than 5 µL of ligation mixture for 50 µL of chemically competent cells. For electroporation, purify DNA from the ligation reaction first. Use recommended DNA amounts (e.g., 1–10 ng per 50 µL cells) [3]. |

| Toxicity of cloned DNA/protein | Use a tightly regulated expression strain. Consider a low-copy number plasmid and grow cells at a lower temperature (e.g., 30°C) to mitigate toxicity [3]. |

| Incorrect antibiotic selection | Verify the antibiotic corresponds to the vector's resistance marker. For plasmids with both ampicillin- and tetracycline-resistance, select on ampicillin as tetracycline is unstable and can become toxic [3]. |

Problem: Transformants with Incorrect or Truncated DNA Inserts

Analysis of selected colonies reveals the vector contains an incorrect or truncated DNA fragment [3].

| Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Unstable DNA | For sequences with direct repeats, tandem repeats, or retroviral sequences, use specialized strains like Stbl2 or Stbl3. Pick colonies from fresh plates (<4 days old) for DNA isolation [3]. |

| DNA mutation | If mutations occur during propagation, pick a sufficient number of colonies for screening. Use a high-fidelity polymerase if the mutation originated from PCR [3]. |

| Cloned fragment truncated | When using restriction enzymes, check for additional, overlapping restriction sites in the fragment. For Gibson Assembly, consider using primers with longer overlaps [3]. |

Problem: Many Colonies with Empty Vectors

After selection and analysis, the vector is found to be empty, lacking the DNA insert [3].

| Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Toxicity of cloned DNA | Use a tightly regulated expression system to ensure no basal expression. Consider vectors with tighter control elements or a low-copy number plasmid [3]. |

| Improper colony selection | For blue/white screening, ensure the host strain carries the lacZΔM15 marker. For positive selection with a lethal gene, ensure the host strain is not resistant to that specific lethal gene product [3]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for working with prokaryotic gene clusters.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Competent Cells | Genetically engineered host cells (e.g., E. coli) that can uptake foreign DNA. Strains like Stbl2/Stbl3/Stbl4 are recommended for stabilizing unstable DNA like direct repeats [3]. |

| Cloning Vectors | Plasmids to shuttle DNA of interest. Low-copy number vectors are recommended to mitigate toxicity of cloned genes [3]. |

| SOC Medium | A rich recovery medium used after the heat-shock or electroporation step in transformation to allow cells to recover and express the antibiotic resistance gene [3]. |

| Selection Antibiotics | Added to growth media to select for cells that have successfully taken up the plasmid vector. Common examples are ampicillin, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol [3]. |

| locus_tag | A systematic gene identifier required for all genes in a genome submission. It is a unique alphanumeric identifier that must be applied to all genes within a genome [4]. |

| protein_id | An identification number assigned to all proteins for internal tracking by databases like NCBI. The format is gnl|dbname|string, where dbname is a unique lab identifier [4]. |

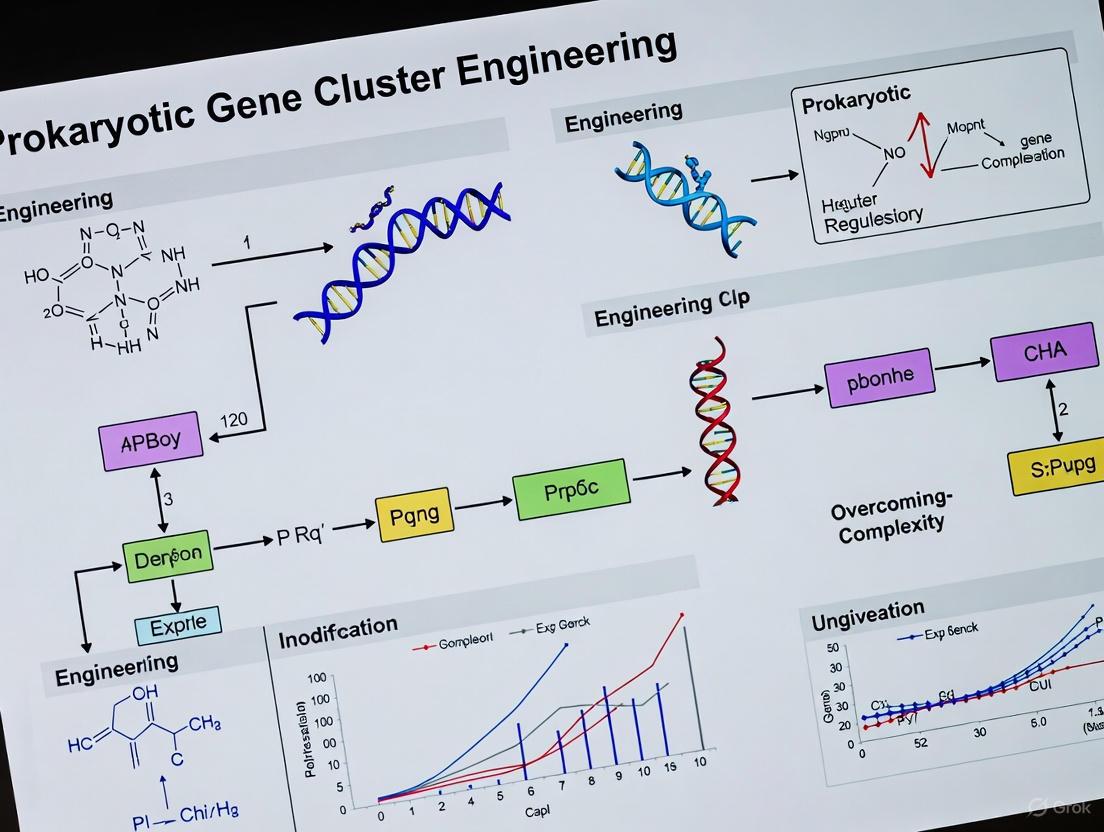

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Gene Cluster Engineering Workflow

Regulatory Complexity in Native Clusters

Refactored Cluster for Predictable Expression

Engineering prokaryotic gene clusters is fraught with challenges stemming from their mosaic architecture—a direct result of horizontal gene transfer (HGT). This natural process, responsible for the patchwork, or mosaic, composition of prokaryotic genomes, is a fundamental driver of adaptation and evolution [5] [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this mosaic structure introduces significant regulatory complexity when attempting to predict, reconstruct, or modify these clusters for industrial or therapeutic applications. This technical support center is designed to help you troubleshoot the specific issues that arise from this complexity, providing clear methodologies and solutions to advance your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

1. FAQ: Our phylogenetic analysis for a putative gene cluster shows severe incongruence with the species tree. How can we confirm this is due to Horizontal Gene Transfer and not another factor?

- Issue: Incongruent phylogenetic trees can stem from HGT, but also from analytical artifacts like uneven evolutionary rates or hidden paralogy.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Step 1 - Verify Sequence Quality: Ensure your sequence data is high-quality and free from contamination, which can create false signals of transfer. Refer to the "Sequencing Preparation Troubleshooting" table below for common issues.

- Step 2 - Apply Multiple Detection Methods: Rely on more than one bioinformatics method to confirm HGT.

- Parametric Methods: Analyze the sequence for atypical nucleotide composition, codon usage, or GC content compared to the host genome core genes [5] [6].

- Phylogenetic Methods: Use tree-reconciliation software (e.g., RANGER-DTL) to compare the gene tree against a trusted species tree. A well-supported transfer event will show the gene clustering with homologs from a distant taxon with high similarity [7].

- Step 3 - Check Functional Context: A gene with a function entirely novel to its recipient lineage (e.g., a eukaryotic-like gene in a bacterium) is a strong candidate for HGT [5].

2. FAQ: We are attempting to express a horizontally acquired gene cluster in a new microbial host, but see very low or no expression. What are the potential causes?

- Issue: Horizontally acquired genes often fail to express in new hosts due to incompatibilities with the host's regulatory machinery.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Root Cause 1 - Promoter/Regulatory Recognition: The native promoter and regulatory elements of the transferred cluster may not be recognized by the host's transcription factors and RNA polymerase.

- Solution: Replace the native promoter with a host-specific, well-characterized promoter. Conduct a promoter library screen to identify optimal expression strength.

- Root Cause 2 - Codon Usage Bias: The codon usage of the acquired gene may be suboptimal for the host's tRNA pool, leading to inefficient translation and ribosome stalling.

- Solution: Use gene synthesis to optimize the coding sequence for the host's codon preference without altering the amino acid sequence.

- Root Cause 3 - Toxic Effects: The expression of the gene product may be toxic to the new host, even at low levels.

- Solution: Use a tightly inducible expression system and carefully titrate the inducer concentration. Consider using a lower-copy-number plasmid.

- Root Cause 1 - Promoter/Regulatory Recognition: The native promoter and regulatory elements of the transferred cluster may not be recognized by the host's transcription factors and RNA polymerase.

3. FAQ: When analyzing metagenomic data, how can we best detect and validate potential HGT events, particularly recent ones?

- Issue: Shotgun metagenomics can suggest HGT, but distinguishing true integration from co-occurrence of donor and recipient DNA is challenging.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Step 1 - Identify Mismatches: Use tools designed for metagenomic analysis to find phylogenetic mismatches within contiguous DNA regions (contigs) [6].

- Step 2 - Look for Mobility Elements: Scan the genomic region flanking the candidate gene for signatures of mobile genetic elements (e.g., plasmid origins of replication, transposase genes, phage integrases). Their presence supports the mechanistic feasibility of HGT [6].

- Step 3 - Experimental Validation: If possible, use PCR to amplify across the proposed integration junctions from purified DNA or perform functional assays to confirm the acquired trait is linked to the recipient organism.

Summarized Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol 1: Detecting HGT via Phylogenetic Tree Reconciliation

This methodology uses comparative genomics to infer HGT events by modeling gene duplication, transfer, and loss (DTL) [7].

- 1. Pangenome Construction: Collect all available genomes for the species of interest. Cluster all genes into families based on a high nucleotide identity threshold (e.g., 80% identity over 50% of the sequence length).

- 2. Species Tree Construction: Build a robust species phylogeny using a set of universal, single-copy marker genes that are rarely transferred (e.g., ribosomal proteins).

- 3. Gene Tree Construction: For each gene family that is present in multiple species, build a phylogenetic tree.

- 4. Tree Reconciliation: Use software like RANGER-DTL to reconcile each gene tree with the species tree. The software will infer the most parsimonious series of DTL events that explain the differences between the trees.

- 5. Filtering: Apply conservative thresholds to accept only well-supported transfer events, filtering out events with low statistical support.

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of a Transferred Gene Cluster

This protocol confirms that a putative horizontally acquired gene cluster is functional in its recipient host.

- 1. Cluster Isolation: Clone the entire gene cluster, including potential native regulatory sequences, into an appropriate vector (e.g., a BAC for large inserts).

- 2. Heterologous Expression: Introduce the construct into a model host (e.g., E. coli) that lacks the cluster and the associated function.

- 3. Phenotypic Assay: Design an assay to test the proposed function of the gene cluster (e.g., growth on a specific carbon source, resistance to an antibiotic, production of a detectable compound).

- 4. Complementation Test: If a knockout mutant of the recipient species is available, introduce the cloned cluster to see if it restores the lost function.

Quantitative Data on HGT Trends

Table 1: Functional Enrichment in Horizontal Gene Transfer Events [7]

| Event Type | Enriched Functional Categories | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Recent Transfers | Transcription, Replication & Repair, Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Genes | Often classified as accessory (cloud) genes in pangenomes; high turnover rate. |

| Old Transfers | Amino Acid Metabolism, Carbohydrate Metabolism, Energy Metabolism | More likely to become ubiquitous (core) genes within a species over time. |

Table 2: Ecological Drivers of Horizontal Gene Transfer [7]

| Ecological Factor | Impact on HGT Rate |

|---|---|

| Co-occurrence | Species that co-occur in the same environment show significantly higher gene exchange. |

| Interaction | Interacting species (e.g., symbiotic, parasitic) transfer more genes. |

| High Abundance | High-abundance species in a community tend to be involved in more HGT. |

| Habitat | Host-associated specialists most frequently exchange genes with other host-associated specialists. |

Table 3: Troubleshooting Sequencing Preparation for HGT Analysis [8]

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Common Root Causes & Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Input/Quality | Low yield; smear in electropherogram. | Cause: Degraded DNA or contaminants (salts, phenol). Fix: Re-purify input; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) over UV absorbance. |

| Fragmentation/Ligation | Unexpected fragment size; high adapter-dimer peaks. | Cause: Over-/under-shearing; improper adapter ratio. Fix: Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter:insert ratio. |

| Amplification/PCR | High duplicate rate; amplification bias. | Cause: Too many PCR cycles. Fix: Use minimal PCR cycles; optimize polymerase and primer conditions. |

Essential Visualization for HGT Workflows

Diagram: HGT Detection via Phylogenetic Reconciliation

This diagram illustrates the core bioinformatics workflow for detecting Horizontal Gene Transfer by reconciling gene trees with a species tree, leading to the identification of a mosaic genome.

Diagram: Mechanisms of Horizontal Gene Transfer

This graph outlines the three primary mechanisms by which Horizontal Gene Transfer occurs in prokaryotes, contributing to mosaic genomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for HGT and Gene Cluster Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Brief Protocol Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification of gene clusters for cloning and functional validation. | Essential for PCR of large, complex regions with high GC content to avoid errors. |

| Broad-Host-Range Cloning Vector (e.g., BAC) | Stable maintenance and manipulation of large gene cluster inserts in diverse prokaryotic hosts. | Use for heterologous expression to test cluster functionality and regulation. |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Software (e.g., RANGER-DTL) | Reconciliation of gene and species trees to infer HGT events. | Requires a pre-computed, trusted species tree and gene alignments as input [7]. |

| Metagenomic Assembly & Binning Tools | Reconstructing genomes and identifying HGT directly from complex environmental samples. | Critical for studying HGT in natural, non-lab-cultivated microbial communities. |

| Restriction-Free Cloning Kit | Seamless cloning of native gene clusters without introducing unwanted restriction sites. | Preferred for assembling complex constructs where maintaining native sequence is critical. |

| Inducible Promoter Systems | Controlled expression of potentially toxic, horizontally acquired genes in new hosts. | Allows titration of expression levels to find a balance between function and host viability. |

Core Concepts: Defining the Sub-Cluster

What is a biosynthetic sub-cluster?

A biosynthetic sub-cluster is a group of co-evolving genes within a larger Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (BGC) that encodes a specific, transferable functional unit. Research shows these sub-clusters are "independent evolutionary entities" that encode key building blocks for complex molecules, operating like modular "bricks" within the larger genetic "mortar" of the BGC [9]. These units often correspond to the synthesis of a specific chemical moiety or a discrete functional step in a pathway.

What is the core evidence supporting their role as independent evolutionary entities?

Systematic computational analysis of BGC evolution provides quantitative evidence for sub-clusters as independent evolutionary entities. Key findings include [9]:

- Widespread Sharing: The same sub-cluster commonly appears in otherwise unrelated BGCs.

- Functional Modularity: Multiple unrelated sub-clusters can combine within a single parent gene cluster.

- Structural Significance: Over 60% of the coding capacity of some complex BGCs (e.g., vancomycin, rubradirin) is composed of individually conserved sub-clusters.

Table: Documented Examples of Functional Sub-Clusters

| Sub-Cluster Function | Parent BGC(s) | Evidence for Independence |

|---|---|---|

| AHBA biosynthesis | Ansamycin-type PKS BGCs (e.g., rifamycin) | Co-evolves as unit; found in diverse macrolactam BGCs [9] |

| Deoxysugar biosynthesis | Everninomicin, Simocyclinone, Polyketomycin | Different variants lead to structural variations in final product [9] |

| MSAS/OSAS production | Various iterative PKS BGCs | Phylogenetic trees show transfer between multiple BGC types [9] |

| Microcompartment formation | Propanediol (pdu) utilization | Core structural components conserved and propagate with pathway enzymes [2] [1] |

Troubleshooting Guides for Sub-Cluster Engineering

Failed Heterologous Expression of Engineered Sub-Clusters

Problem: After transferring or engineering a sub-cluster into a new host, the expected product is not detected.

Solution:

- Verify Regulatory Context: "The cluster may rely on regulatory interactions that are not present in the new host" [2] [1]. Screen native regulators or implement orthogonal control systems [10].

- Check Codon Optimization: Use host-optimized codons for all genes, particularly for specialized enzymatic components.

- Confirm Cofactor Availability: Ensure necessary cofactors and precursor molecules are available in the heterologous host.

- Test Sub-Cluster Functionality: Before transfer, verify the sub-cluster is functional in its native context by knocking out key genes and confirming loss of the specific chemical moiety.

Table: Quantitative Analysis of Evolutionary Events in BGCs [9]

| Evolutionary Event Type | Relative Rate in BGCs | Implication for Sub-Cluster Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Insertions/Deletions | Exceptionally high | Supports modular "cut and paste" approach |

| Horizontal Transfer | High frequency | Validates heterologous expression strategy |

| Large Indels (≥10 kb) | 195 identified | Confirms transfer of substantial sub-clusters is evolutionarily feasible |

| Domain Duplications | Elevated rates | Encourages domain swapping for pathway diversification |

Low Product Yield from Synthetic Sub-Cluster Combinations

Problem: Engineered pathways containing synthetic sub-cluster combinations produce target compounds at very low yields.

Solution:

- Balance Gene Expression: "The genes do not express or express at the wrong ratios" in new contexts [2] [1]. Use RNA-based regulatory tools with large dynamic ranges to fine-tune expression [10].

- Implement Metabolic Insulation: Apply design principles that "enable robust and scalable circuit performance such as insulating a gene circuit against unwanted interactions with its context" [10].

- Monitor Intermediate Toxicity: For pathways with toxic intermediates, consider co-expressing microcompartment sub-clusters that "encapsulate enzymes that participate in metabolic pathways where an intermediate is toxic" [2] [1].

- Apply Rapid Debugging Strategies: Use "efficient strategies for rapidly identifying and correcting causes of failure and fine-tuning circuit characteristics" [10].

Genetic Instability in Refactored Sub-Clusters

Problem: Engineered sub-clusters show genetic instability or rearrangements during cultivation.

Solution:

- Eliminate Repetitive Sequences: Remove or break up long repetitive sequences that facilitate homologous recombination.

- Implement Orthogonal Parts: Use "versatile components and tools available for engineering gene circuits" that exhibit orthogonality to minimize cross-talk and instability [10].

- Stabilize with Different Genetic Contexts: Test the sub-cluster in different plasmid or genomic contexts to identify more stable configurations.

- Apply Continuous Evolution Pressure: Maintain selection pressure for the desired function throughout cultivation to suppress non-producing mutants.

Experimental Protocols for Sub-Cluster Analysis and Engineering

Protocol: Computational Identification of Sub-Clusters in BGCs

Purpose: To identify potential sub-clusters within a biosynthetic gene cluster of interest using bioinformatic approaches.

Methodology (based on systematic analysis principles from [9]):

- Collect BGC Homologs: Gather sequences of homologous BGCs from public databases (e.g., MIBiG, antiSMASH).

- Perform Phylogenetic Profiling: Identify co-evolving gene sets using χ2 tests or similar statistical approaches.

- Identify Conserved Domain Motifs: Scan for adjacent Pfam domains that consistently appear together across multiple BGCs.

- Construct Sharing Networks: Build networks where nodes represent BGCs and edges denote shared sub-clusters.

- Validate Functional Association: Correlate identified sub-clusters with specific chemical moieties in the final natural product.

Expected Results: The original study identified "884 different motifs of adjacent Pfam domains (out of 7,641 found) that were shown to co-evolve significantly more often than not (P<0.001)" [9].

Protocol: Modular Sub-Cluster Swapping for Pathway Diversification

Purpose: To replace a sub-cluster in a parent BGC with an alternative sub-cluster to produce novel compounds.

Methodology:

- Select Compatibility Domains: Focus on domains that "evolve by concerted evolution, which generates sets of sequence-homogenized domains that may hold promise for engineering efforts since they exhibit a high degree of functional interoperability" [9].

- Design Flanking Homology Regions: Include 500-1000 bp homology arms for precise recombination at sub-cluster boundaries.

- Implement in Chassis Strain: Use established synthetic biology DNA assembly methods to construct the hybrid BGC [2] [10].

- Screen for Product Diversity: Analyze metabolites for the presence of both the original and novel chemical moieties.

Visualization: Sub-Cluster Relationships and Engineering Workflow

Diagram: Sub-Cluster Engineering Workflow from Discovery to Application

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sub-Cluster Engineering

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Regulatory Parts (Promoters, RBS) | Enable predictable gene expression in new hosts | Balancing expression in synthetic sub-cluster combinations [10] |

| RNA-based Regulatory Tools | Provide large dynamic ranges for fine-tuning | Optimizing sub-cluster gene expression ratios [10] |

| Modular DNA Assembly Systems | Facilitate hierarchical construction of large DNA fragments | Assembling synthetic sub-clusters and hybrid BGCs [2] [1] |

| Heterologous Host Chassis | Provide clean genetic background for expression | Testing sub-cluster functionality without native regulatory interference [2] |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Software | Identify co-evolving gene sets | Computational identification of potential sub-clusters [9] |

| Metabolite Profiling Platforms | Characterize chemical outputs | Validating function of engineered sub-cluster combinations |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do sub-clusters differ from the broader concept of modularity in NRPS/PKS systems?

While NRPS/PKS modularity typically refers to domain and module organization within mega-synthases, sub-clusters represent a higher level of organization - groups of co-evolving genes that encode for discrete chemical moieties or functional units. As research shows, "BGCs for complex molecules often evolve through the successive merger of smaller sub-clusters, which function as independent evolutionary entities" [9]. This represents evolutionary modularity at the genetic level rather than just the enzymatic level.

Are there particular types of BGCs where the sub-cluster hypothesis is most applicable?

Yes, distinct "BGC families evolve in distinct ways" [9]. The hypothesis is particularly well-supported for:

- Hybrid BGCs: Such as the "multi-hybrid rubradirin gene cluster" which appears to have "arisen from a rifamycin-like ancestor... which then acquired new sub-clusters" [9].

- Glycopeptide BGCs: Which show "complex mosaic patterns of sub-cluster sharing" [9].

- BGCs containing microcompartments: Where "sub-clusters also occur within metabolic pathways" for specific modifications [2] [1].

What are the major challenges in applying sub-cluster engineering to awaken cryptic clusters?

The primary challenges include:

- Regulatory Complexity: Cryptic clusters may have complex native regulation that is difficult to reconstruct [2] [1].

- Host Dependencies: There may be "auxiliary interactions with or dependencies on the host" that are not transferred with the sub-cluster [2] [1].

- Expression Balancing: Successful activation requires "the need to balance the expression of many genes" which is particularly challenging for sub-clusters in new genomic contexts [2] [1].

How can we identify which sub-cluster combinations are most likely to be functionally compatible?

Focus on sub-clusters that:

- Share Evolutionary History: As seen in ansamycin-type PKS where "KS domains of the diverse range of ansamycin type I PKS BGCs that harbor AHBA sub-clusters are almost completely monophyletic" [9].

- Exhibit Concerted Evolution: "An important subset of polyketide synthases and nonribosomal peptide synthetases evolve by concerted evolution, which generates sets of sequence-homogenized domains that may hold promise for engineering efforts since they exhibit a high degree of functional interoperability" [9].

- Appear in Multiple Contexts: Sub-clusters that naturally appear in diverse BGC backgrounds are more likely to be portable.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Heterologous Expression of BGCs

Problem: Few or no transformants after introducing a cryptic BGC into a heterologous host.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations & Solutions |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal Transformation Efficiency | Use high-efficiency competent cells, avoid freeze-thaw cycles, and ensure DNA is free of contaminants like phenol or detergents [3]. For large constructs (>10 kb), use electroporation [11]. |

| Toxicity of Cloned DNA | Use a tightly regulated expression strain (e.g., NEB 5-alpha F´ Iq), a low-copy-number plasmid, and grow cells at a lower temperature (25–30°C) to minimize basal expression [3] [11]. |

| Very Large Construct Size | Select specialized competent cells like NEB 10-beta or NEB Stable for large DNA constructs. Remember that larger constructs require adjusting the DNA mass to achieve optimal molar concentrations for cloning [11]. |

| Inefficient Ligation | Ensure at least one DNA fragment has a 5´ phosphate. Vary the vector-to-insert molar ratio (1:1 to 1:10). Use fresh ligation buffer to prevent ATP degradation [11]. |

Problem: Transformants contain incorrect or truncated DNA inserts.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations & Solutions |

|---|---|

| Unstable DNA Repeats | Use specialized strains like Stbl2 or Stbl4 for sequences with direct or tandem repeats. Pick colonies from fresh plates (<4 days old) for DNA isolation [3]. |

| Internal Restriction Sites | Re-analyze the insert sequence for the presence of unrecognized internal restriction enzyme recognition sites that may have been partially cleaved [11]. |

| Mutation During Cloning | Use a high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase) during PCR amplification of cluster fragments. Pick multiple colonies for screening [11]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Endogenous Activation of Silent BGCs

Problem: A silent BGC fails to activate after genetic manipulation in the native host.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations & Solutions |

|---|---|

| Complex Regulatory Networks | The cluster may be under the control of uncharacterized, multi-layer regulation. Implement Reporter-Guided Mutant Selection (RGMS) to identify key regulatory genes via transposon mutagenesis [12]. |

| Insufficient Precursor Supply | The host may lack necessary metabolic precursors. Supplement the growth medium with potential precursors or co-express key metabolic pathway genes to augment the metabolic flux [12]. |

| Incorrect Culture Modality | The environmental or co-culture signals required for induction are absent. Systematically test a wide range of culture conditions, including various media, and co-culture with potential microbial interactors [12]. |

Problem: A BGC is successfully activated, but the product yield is too low for detection or isolation.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations & Solutions |

|---|---|

| Weak Promoters | Replace native promoters within the BGC with strong, inducible synthetic promoters to boost the expression of all biosynthetic genes simultaneously, an approach known as refactoring [2]. |

| Imbalanced Gene Expression | The expression of genes within the cluster is not optimal. Re-engineer ribosome binding sites (RBSs) to balance the translation rates of individual enzymes in the pathway [2]. |

| Product Degradation or Export | The host may be degrading or actively exporting the product. Knock out genes encoding putative efflux pumps or degrading enzymes identified in the genome [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between endogenous and exogenous strategies for activating silent BGCs?

A: The key difference lies in the host organism used.

- Endogenous Strategies perform activation within the native producer. The main advantage is physiological relevance, as the intended metabolite is produced in its authentic context, simplifying studies on its biological role [12].

- Exogenous (Heterologous) Strategies involve transferring and expressing the BGC in a foreign, easily culturable host (e.g., E. coli or S. albus). This is crucial for studying BGCs from unculturable organisms or those that are difficult to manipulate genetically. However, it can be laborious and may fail if the host lacks necessary precursors or post-translational modifications [12].

Q2: My genome sequence reveals a cryptic BGC, but I don't know where to start. What is a systematic first approach?

A: A highly effective and genetics-agnostic first step is to explore diverse culture modalities. This involves growing the native producer under a wide array of conditions it might encounter in its natural habitat, such as:

- Varying nutrient sources, pH, and temperature.

- Using solid versus liquid media.

- Introducing stress factors (e.g., oxidative stress, sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics).

- Employing co-culture with other microorganisms that might be ecological competitors or collaborators, as their interactions can trigger silent clusters [12].

Q3: What computational tools can I use to identify and prioritize cryptic BGCs in a bacterial genome?

A: Several powerful tools are available, each with strengths. You can use the following table for comparison:

| Tool | Primary Methodology | Key Features / Best For |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [12] [13] | Rule-based (pHMMs and heuristics) | The gold standard for broad-spectrum detection of over 100 BGC classes; provides detailed annotations. |

| DeepBGC [13] | Deep Learning (Bi-LSTM networks) | Improved generalization for detecting BGCs with atypical sequences; uses sequence context. |

| RFBGCpred [13] | Machine Learning (Random Forest) | High-accuracy classification of five major classes (PKS, NRPS, RiPPs, terpenes, hybrids); good for atypical hybrids. |

Q4: I am submitting a metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) containing a novel BGC to a database. What are key requirements?

A: When submitting a MAG to NCBI, ensure it meets these criteria [14]:

- Completeness: The assembly must have a CheckM or CheckM2 completeness estimate of at least 90%.

- Size: The total assembly size must be at least 100,000 nucleotides.

- Origin: The sequence must be your own data, not only downloaded from a public repository.

- Registration: You will need to register a BioProject and a BioSample for the MAG, and submit the raw reads to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Reporter-Guided Mutant Selection (RGMS) for Endogenous Activation

This protocol uses a genetic reporter to screen for mutants that activate a silent BGC [12].

1. Reporter Construction:

- Fuse a promoterless reporter gene (e.g.,

xylEfor a colorimetric assay orneofor kanamycin resistance) to a strong, constitutive promoter within the target silent BGC. - Integrate this reporter construct into the native host's chromosome, ensuring it does not disrupt the BGC itself.

2. Mutant Library Generation:

- Create a random mutant library of the reporter strain using UV mutagenesis or Transposon (Tn) mutagenesis. Tn mutagenesis is preferred as it allows for later identification of the inactivated gene.

3. Mutant Selection:

- Plate the mutant library on solid media and screen for colonies that express the reporter phenotype (e.g., turn brown upon catechol treatment for

xylE, or show increased resistance to kanamycin forneo).

4. Metabolite Analysis:

- Cultivate the selected mutant strains in liquid culture and extract metabolites using an appropriate solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- Analyze the extracts using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS) to compare the metabolic profile with the wild-type strain and identify newly produced compounds.

5. Gene Identification (if Tn mutagenesis was used):

- Locate the site of the transposon insertion in the activated mutant using techniques like arbitrary PCR or sequencing. This identifies the gene whose disruption awakened the cluster.

Protocol 2: Heterologous Expression of a Refactored BGC

This protocol involves redesigning and synthesizing a BGC for expression in a heterologous host like E. coli or S. albus [2].

1. Cluster Refactoring:

- In Silico Design: Analyze the native BGC sequence. Remove all native regulatory elements (native promoters, terminators). Replace them with well-characterized, orthogonal synthetic parts (promoters, RBSs, terminators) to create a simplified, modular genetic circuit.

- DNA Synthesis: The refactored cluster sequence is synthesized de novo in fragments (e.g., ~10 kb each).

2. Hierarchical DNA Assembly:

- Assemble the synthesized ~10 kb fragments into larger multi-100kb pieces using advanced DNA assembly methods like Gibson Assembly or Golden Gate Assembly [2] [11].

- Clone the fully assembled BGC into a suitable expression vector (e.g., a bacterial artificial chromosome, BAC).

3. Transformation and Screening:

- Introduce the vector containing the refactored BGC into the chosen heterologous host using high-efficiency transformation (e.g., electroporation).

- Screen transformants for the vector's antibiotic resistance marker.

- Induce expression of the BGC by adding the inducer specific to the synthetic promoters.

4. Metabolite Detection and Purification:

- Culture the positive clones and extract metabolites.

- Use analytical techniques (HPLC-MS) to detect the target compound. Scale up fermentation for compound purification and structural elucidation (NMR).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| NEB 10-beta Competent E. coli [11] | A heterologous host strain ideal for large or unstable DNA constructs; deficient in restriction systems (McrA, McrBC, Mrr) that degrade methylated DNA from other organisms. |

| Stbl2 / Stbl4 Competent E. coli [3] | Specialized strains for stabilizing DNA sequences containing direct or tandem repeats (e.g., those found in some PKS clusters), reducing recombination during propagation. |

| Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [11] | Used for accurate PCR amplification of BGC fragments or subcloning with a very low error rate, preventing mutations during cloning steps. |

| T4 DNA Ligase [11] | Essential for joining DNA fragments with compatible ends during the cloning of BGC segments into plasmid vectors. |

| pLATE Vectors [3] | Vectors with tightly regulated, inducible promoters to control the expression of potentially toxic genes cloned from BGCs, minimizing basal leakage. |

| antiSMASH Software [12] [13] | The primary computational tool for the genome-wide identification and annotation of BGCs in a sequenced genome. |

Engineering biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in prokaryotes is often frustrated by the intricate and multi-layered nature of gene regulatory mechanisms [15]. Natural regulatory systems exhibit remarkable complexity, typically employing a combination of diverse mechanisms operating at different levels—transcription, translation, and post-translation—to generate precisely adapted regulatory responses [15]. This complexity creates significant bottlenecks for synthetic biology approaches attempting to engineer new pathways, as unlike modular engineering components, biological parts do not universally 'fit' together and often function effectively only in specific pathway contexts [16].

However, nature itself provides a blueprint for overcoming these challenges through evolutionary processes that have successfully generated thousands of distinct biosynthetic gene cluster families [16]. By studying these natural engineering strategies, particularly concerted evolution and the principles of interoperability, researchers can develop more effective approaches for BGC engineering. Concerted evolution generates sets of sequence-homogenized domains through internal recombinations, while interoperability principles guide how these domains can be productively combined [16]. Understanding these mechanisms provides a roadmap for mimicking nature's success in engineering biosynthetic pathways.

Theoretical Foundation: Principles from Natural Evolution

Concerted Evolution in Natural Systems

Systematic computational analyses of BGC evolution reveal that an important subset of polyketide synthases (PKS) and nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) evolve through concerted evolution [16]. This process generates sets of sequence-homogenized domains that show a high degree of functional interoperability. Concerted evolution is driven by internal recombination events that create modules and domains with compatible interfaces, enabling them to work effectively together in biosynthetic pathways [16].

The evolutionary trajectory of complex BGCs often occurs through the successive merger of smaller, functionally independent sub-clusters [16]. These sub-clusters represent coherent functional units that encode specific sub-functionalities within larger pathways. This modular evolutionary strategy provides critical insights for engineering approaches, suggesting that sub-clusters rather than individual genes may represent the most productive units for cluster engineering [16].

Quantitative Analysis of BGC Evolutionary Dynamics

Table 1: Evolutionary Patterns in Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

| Evolutionary Characteristic | Observation | Implication for Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Rate | Exceptionally high rates of insertions, deletions, duplications and rearrangements compared to primary metabolic clusters [16] | Engineering attempts can embrace greater sequence and structural flexibility than traditionally assumed |

| Sub-cluster Co-evolution | 884 different motifs of adjacent Pfam domains show significant co-evolution (P<0.001) with average length of 5.3 domains [16] | Identified sub-clusters represent natural engineering units with proven interoperability |

| Family-Specific Evolution | Distinct BGC families evolve in specialized modes that differ significantly from each other [16] | Engineering strategies should be tailored to specific BGC families rather than using one-size-fits-all approaches |

| Domain Interoperability | Concerted evolution creates sets of sequence-homogenized domains with high functional compatibility [16] | Domain swapping is most likely to succeed when using domains from the same concerted evolution group |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Sequence-to-Expression Model Building for Fitness Landscape Analysis

Objective: Construct accurate fitness landscapes that map promoter DNA sequences to expression levels, enabling evolutionary studies and sequence design [17].

Methodology:

- Sequence Library Generation: Measure expression driven by millions of random 80 bp promoter DNA sequences cloned into an episomal low copy number YFP expression vector in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [17]

- Expression Assaying: Culture transformed yeast in both complex (YPD) and defined media (SD-Ura), sort cells into 18 expression bins, and sequence promoters from each bin to estimate expression levels [17]

- Model Training: Train convolutional neural network models using sequence-expression pairs, with models generalizing to predict expression from sequence with high accuracy (Pearson's r = 0.960 for native yeast promoters) [17]

- Evolutionary Simulation: Use trained models as "oracles" to simulate evolutionary scenarios including genetic drift, stabilizing selection, and directional selection under various mutation regimes [17]

Validation: Experimental verification of model predictions shows strong correlation between predicted and measured expression (Pearson's r: 0.869-0.973 across conditions) [17].

Computational Analysis of BGC Evolutionary Patterns

Objective: Systematically identify evolutionary patterns in biosynthetic gene clusters to derive engineering principles [16].

Methodology:

- Dataset Curation: Compile known and predicted prokaryotic BGCs from public databases (732 known and 10,724 predicted clusters) [16]

- Evolutionary Event Quantification: Mutually compare all gene clusters to quantify horizontal transfer events, insertion/deletion rates, duplication frequencies, and rearrangement patterns [16]

- Co-evolution Analysis: Apply phylogenetic profiling to identify significantly co-evolving domain motifs using χ² tests (P<0.001) [16]

- Concerted Evolution Detection: Identify sequence homogenization patterns through internal recombination analysis using domain sequence alignment and phylogenetic reconstruction [16]

Key Parameters: Analysis of 7,641 Pfam domain motifs identified 884 with significant co-evolution patterns [16].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Gene Cluster Engineering

Troubleshooting DNA Assembly and Transformation

Table 2: Common Experimental Issues in DNA Assembly and Transformation

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Few or no transformants | Suboptimal transformation efficiency, toxic cloned DNA/protein, incorrect antibiotic concentration [3] | Use high-efficiency competent cells; avoid freeze-thaw cycles; use low-copy number vectors for toxic genes; verify antibiotic selection [3] |

| Transformants with incorrect/truncated inserts | Unstable DNA repeats, mutation during propagation, restriction site issues [3] | Use specialized strains (e.g., Stbl2/Stbl4 for repeats); pick fresh colonies; verify restriction sites; use high-fidelity polymerase [3] |

| Many empty vectors | Toxic insert, improper selection method, issues in upstream cloning [3] | Use tightly regulated promoters; employ appropriate selection systems (blue/white screening); review upstream cloning steps [3] |

| Slow cell growth or low DNA yield | Wrong media, improper growth conditions, old colonies [3] | Use enriched media (TB for pUC vectors); ensure proper aeration; use fresh starter cultures [3] |

Addressing Sequencing Preparation Failures

Problem: Low library yield in NGS preparation [8]

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Cause: Poor input quality/contaminants inhibiting enzymes

- Solution: Re-purify input sample; ensure wash buffers are fresh; target high purity (260/230 > 1.8, 260/280 ~1.8) [8]

- Cause: Inaccurate quantification/pipetting error

- Solution: Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) rather than UV; calibrate pipettes; use master mixes [8]

- Cause: Fragmentation/tagmentation inefficiency

- Solution: Optimize fragmentation parameters; verify distribution before proceeding [8]

- Cause: Suboptimal adapter ligation

- Solution: Titrate adapter:insert molar ratios; ensure fresh ligase and buffer [8]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Gene Cluster Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Network Models | Predict gene expression from promoter sequences; serve as fitness landscape oracles [17] | Enable in silico evolution experiments; achieve Pearson's r = 0.96 prediction accuracy [17] |

| Specialized E. coli Strains (Stbl2, Stbl4) | Stabilize DNA sequences with direct repeats, tandem repeats, or retroviral sequences [3] | Essential for cloning unstable DNA elements; reduces recombination events [3] |

| Orthogonal Sigma Factors | Enable specific promoter recognition without cross-reactivity with endogenous systems [15] | Critical for synthetic circuits; provides functional insulation from host machinery [15] |

| Non-redundant Protein Accessions (WP_) | Standardized protein records representing identical sequences across multiple genomes [18] | Facilitates comparative genomics and evolutionary analysis of protein families [18] |

| Gaussian Bayesian Network Algorithms | Reconstruct Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) from high-dimensional gene expression data [19] | Effectively models complex hub-based interaction structures in GRNs [19] |

Computational Tools and Workflows

BGC Engineering Analysis Workflow

RNA Switch Design Principle

The principles of concerted evolution and interoperability derived from natural systems provide a powerful framework for overcoming the challenges of regulatory complexity in prokaryotic gene cluster engineering. By identifying naturally co-evolving sub-clusters and leveraging sequence-homogenized domains generated through concerted evolution, researchers can develop more successful engineering strategies that mimic nature's proven approaches [16]. The experimental protocols and troubleshooting guides presented here offer practical pathways for implementing these principles, while the computational workflows enable systematic analysis of evolutionary patterns to inform engineering design.

As synthetic biology continues to advance, embracing these natural engineering principles will be crucial for developing more predictable and effective methods for biosynthetic pathway engineering. The integration of AI-guided design with evolutionary insights promises to accelerate both fundamental research and industrial applications in this rapidly advancing field [20].

The Synthetic Biology Toolkit: Methodologies for Engineering and Refactoring Gene Clusters

In the pursuit of overcoming regulatory complexity in prokaryotic gene cluster engineering, the limitations of traditional genetic tools become starkly apparent. Engineering organisms like Streptomyces—prolific producers of antibiotics and other natural products—requires manipulating large, intricate biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Conventional vector systems, often restricted to operating on single genes, are incompatible with advanced assembly methods and pose a significant bottleneck for refactoring multi-gene pathways [21]. Modern DNA assembly toolkits address this by providing flexible, modular, and versatile platforms. These systems are designed to be compatible with various DNA assembly approaches, such as BioBrick, Golden Gate, CATCH, and yeast homologous recombination, offering researchers the adaptability needed to handle multiple genetic parts or refactor large gene clusters efficiently [21]. This adaptability is crucial for activating silent BGCs and optimizing the production of novel natural products, thereby accelerating drug discovery.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common DNA Assembly Issues

This section addresses specific, high-impact problems researchers may encounter when working with DNA assembly toolkits for large constructs, along with evidence-based solutions.

Problem: Few or No Transformants

This is a common failure point, especially when handling large genetic constructs.

| Problem Cause | Evidence-Based Solution |

|---|---|

| General Cell Viability | Transform an uncut plasmid to check viability and transformation efficiency. If efficiency is low (<10⁴ CFU/μg), remake competent cells or use commercial high-efficiency cells [22]. |

| Large Construct Size (>10 kb) | Use competent cell strains specifically designed for large constructs, such as NEB 10-beta or NEB Stable Competent E. coli. For very large constructs, use electroporation. Adjust the DNA mass to achieve 20-30 fmol for ligation [22]. |

| Toxic DNA Fragment | Incubate transformation plates at a lower temperature (25–30°C). Use a strain with tighter transcriptional control, such as NEB 5-alpha F´ Iq Competent E. coli [22]. |

| Inefficient Ligation | Ensure at least one DNA fragment has a 5´ phosphate. Vary the vector-to-insert molar ratio from 1:1 to 1:10. Purify DNA to remove contaminants like salt or EDTA. Use fresh ligation buffer, as ATP degrades with freeze-thaw cycles [22]. |

Problem: Colonies Contain the Wrong Construct

Obtaining colonies that do not harbor the desired plasmid is a frequent setback.

| Problem Cause | Evidence-Based Solution |

|---|---|

| Plasmid Recombination | Use a recA– strain such as NEB 5-alpha, NEB 10-beta, or NEB Stable Competent E. coli to prevent unwanted recombination events [22]. |

| Internal Restriction Site | Use sequence analysis tools (e.g., NEBcutter) to scan the insert for internal recognition sites for the restriction enzymes used in the assembly [22]. |

| Mutation in Sequence | Use a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase) during PCR amplification of parts to minimize introduction of errors [22]. |

Problem: Excessive Background (Non-Recombinant Colonies)

A high number of false-positive colonies can complicate screening.

| Problem Cause | Evidence-Based Solution |

|---|---|

| Inefficient Vector Digestion | Check the methylation sensitivity of restriction enzymes. Use the recommended reaction buffer and clean up DNA before digestion to remove potential inhibitors [22]. |

| Inefficient Dephosphorylation | Heat-inactivate or remove restriction enzymes prior to vector dephosphorylation. Ensure active kinase from a prior phosphorylation step is inactivated, as it can re-phosphorylate the vector [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of a modular DNA assembly toolkit over traditional vectors for gene cluster engineering? Traditional vectors (e.g., pIJ family) are often limited to single-gene operations and are incompatible with standard modular assembly approaches like Golden Gate or BioBrick. A modern toolkit offers flexibility in assembly methods, allows easy exchange of plasmid backbones (copy number, integration site, selection marker), and is specifically designed for cloning and editing large gene clusters using advanced methods like CATCH and yeast recombination [21].

Q2: How can CRISPR/Cas9 be integrated into a DNA assembly toolkit to simplify metabolic engineering? CRISPR/Cas9 can be harnessed to enable high-efficiency, marker-free chromosomal integration, eliminating laborious marker recovery steps. A well-designed toolkit can facilitate this by allowing quick swapping between marker-free and marker-based integration constructs, easy redirection of donor DNA to new genomic loci via Golden Gate assembly of homology arms, and a rapid method for assembling guide RNA sequences [23].

Q3: My assembly involves a very large gene cluster. What specific methods should my toolkit support? For large gene clusters, your toolkit should be compatible with methods like Cas9-Assisted Targeting of CHromosome segments (CATCH) for cloning directly from genomic DNA, and yeast homologous recombination-based assembly (e.g., TAR, mCRISTAR) for editing large clusters in a single step [21]. These methods are essential for handling sequences that exceed the capacity of standard plasmid propagation.

Q4: How can I quantitatively characterize regulatory parts like promoters within a defined genomic context? A CRISPR/Cas9-facilitated toolkit allows for the single-copy integration of promoter constructs into a specific genomic locus. This standardizes the genetic context, allowing for accurate comparison. The promoter strength can then be quantified by measuring the output of a reporter gene like sfGFP [21] [23].

Experimental Protocol: Cloning and Refactoring a Gene Cluster

The following detailed methodology, adapted from a study on the act gene cluster in Streptomyces, demonstrates the application of a flexible toolkit for handling large constructs [21].

Method: CATCH Cloning and Yeast Recombination-Based Editing of a Gene Cluster

1. Cloning the Gene Cluster via CATCH

- Materials: Source strain (e.g., S. coelicolor M145), CHEF genomic DNA plug kit, Cas9 enzyme, sgRNAs, linearized capture vector (e.g., pPAB-HR), Gibson assembly mix, electrocompetent E. coli EPI300.

- Procedure:

- Prepare Genomic DNA: Cultivate the source strain and prepare high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA embedded in plugs.

- In Vitro Cas9 Digestion: Design sgRNAs flanking the target gene cluster. Incubate genomic DNA plugs with purified Cas9 enzyme and the sgRNAs to excise the linear gene cluster fragment.

- Prepare Vector: Linearize the capture vector using an appropriate restriction enzyme (e.g., AarI) to create ends with homology to the excised gene cluster.

- Assemble and Transform: Recover the digested gene cluster fragment and assemble it with the linearized vector using Gibson assembly. Introduce the assembly reaction into electrocompetent E. coli.

- Verification: Verify correct recombinant plasmids by PCR and restriction digestion (e.g., using I-SceI) [21].

2. Refactoring the Cluster via Yeast Recombination

- Materials: Cloned gene cluster plasmid (e.g., pPAB-act), Cas9 enzyme, sgRNAs targeting promoter regions, promoter cassettes, yeast autotrophic marker (URA), S. cerevisiae VL6-48, Frozen-EZ Yeast Transformation II Kit.

- Procedure:

- Digest Plasmid: Digest the cloned gene cluster plasmid (pPAB-act) in vitro with Cas9 complexed with sgRNAs that target specific promoter regions for replacement.

- Prepare Donor DNA: Amplify the new promoter cassettes and the yeast selection marker (URA) by PCR, ensuring the amplicons have ends homologous to the regions flanking the Cas9 cut sites.

- Yeast Transformation: Co-transform the Cas9-digested plasmid and the donor DNA fragments into yeast. The yeast's homologous recombination machinery will repair the breaks by integrating the new promoters.

- Screen and Recover: Screen yeast colonies for correct integration by PCR. Isolate the engineered plasmid from yeast for subsequent transformation into the production host [21].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and their functions for executing DNA assembly toolkit experiments, particularly for large constructs [21] [22] [23].

| Research Reagent | Function & Application in DNA Assembly |

|---|---|

| High-Efficiency Competent E. coli (e.g., NEB 10-beta, NEB Stable) | Essential for transforming large DNA constructs (>10 kb); these strains are recA– and deficient in restriction systems (McrA, McrBC, Mrr), improving transformation efficiency and plasmid stability [22]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Used for both cloning (CATCH method) and subsequent editing of gene clusters. Enables precise double-strand breaks to excise genomic fragments or linearize plasmids for recombination [21] [23]. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | An enzyme mix that allows simultaneous assembly of multiple DNA fragments with overlapping ends in a single, isothermal reaction. Ideal for building constructs and inserting large fragments into vectors [21]. |

| Golden Gate Assembly Mix (e.g., BsaI-HFv2) | A restriction-ligation method that allows for the modular, one-pot assembly of multiple genetic parts from a library. Crucial for part standardization and toolkit versatility [21] [23]. |

| Yeast Strain (e.g., VL6-48) | Used as a host for assembling very large DNA constructs via homologous recombination, which is more efficient and tolerant of large sizes than traditional E. coli-based methods [21]. |

| T4 DNA Ligase | The standard enzyme for joining DNA fragments with compatible cohesive or blunt ends. Critical for many traditional and modern ligation-based assembly protocols [22]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5) | Used for the accurate amplification of genetic parts and modules without introducing mutations, which is vital for maintaining sequence integrity [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

Low or Undetectable Protein Expression

Q: I have replaced a native promoter with a standardized, high-strength part, but my protein expression is still very low or undetectable. What could be wrong?

A: Low expression after promoter replacement is a common issue. The table below summarizes potential causes and solutions.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Translation Initiation [15] [24] | Check the Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) strength using computational tools (e.g., RBS Calculator). | Replace the native RBS with a synthetic, well-characterized RBS from a library of parts with varying strengths [15] [24]. |

| mRNA Instability [15] | Analyze the 5' and 3' UTRs for native sequences that may trigger rapid degradation. | Engineer the 5' and 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) to include stabilizing sequences [24]. |

| Tight Native Regulation Still Active [15] | Check for internal promoters, transcription factors, or attenuator mechanisms within the coding region. | Perform a full operon refactoring, replacing all native regulatory elements with synthetic counterparts [15]. |

| Codon Usage Bias | Compare the codon usage of your gene with the host's preferred codons. | Perform whole-gene synthesis to optimize the coding sequence for your expression host [24]. |

Experimental Protocol: RBS Strength Tuning

- Select an RBS Library: Choose a set of well-characterized RBS parts with a range of predicted translation initiation strengths [15].

- Clone Constructs: Assemble your gene of interest, downstream of a consistent promoter, with each RBS variant from the library. Using a modular cloning system (e.g., Golden Gate, MoClo) is ideal for this [24].

- Transform and Cultivate: Transform the constructs into your expression host and grow cultures under inducing conditions.

- Measure Output: Quantify protein expression using a method like SDS-PAGE with densitometry or a functional enzyme assay. Correlate the expression level with the specific RBS part to select the optimal one.

Inconsistent Expression and Population Heterogeneity

Q: My refactored system shows high cell-to-cell variability in expression, leading to inconsistent performance. How can I make expression more uniform across the population?

A: Population heterogeneity often stems from unpredictable interactions with the host. The following table outlines the troubleshooting steps.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Context Effects from Flanking DNA [15] | Sequence the regions upstream and downstream of the integrated construct. | Insulate the synthetic circuit by flanking it with strong transcriptional terminators and insulator elements [15]. |

| Host Regulation Interference | Use RNA-seq to identify unexpected sRNA or transcription factor binding. | Employ orthogonal regulatory parts, such as orthogonal RNA polymerases or sigma factors, that do not cross-react with the host's machinery [15]. |

| Metabolic Burden [15] [24] | Monitor host cell growth rate; a significant slowdown indicates burden. | Use tunable promoters to find an expression level that balances protein yield with host fitness. Consider dynamic regulation [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Expression Heterogeneity

- Clone a Reporter: Fuse your gene of interest to a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) on an expression plasmid.

- Analyze via Flow Cytometry: Grow your culture and analyze the cells using flow cytometry.

- Calculate Heterogeneity: The coefficient of variation (CV = Standard Deviation / Mean) of the fluorescence histogram is a measure of population heterogeneity. A lower CV indicates more uniform expression.

- Test Interventions: Repeat the measurement after implementing a solution (e.g., adding insulator parts) to see if the CV decreases.

Host Toxicity and Genetic Instability

Q: My refactored gene cluster is toxic to the host, or the construct is frequently mutated or lost from the population over time. How can I stabilize it?

A: Toxicity and instability are major challenges in metabolic engineering. The troubleshooting guide is below.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Toxic Intermediate Accumulation | Use metabolomics to identify buildup of pathway intermediates. | Implement a dynamic control system that delays expression of toxic genes until necessary, or use a lower-copy number plasmid [15]. |

| Resource Overconsumption [24] | Monitor levels of key cellular resources like ATP, NADPH, and tRNAs. | Fine-tune the expression of each enzyme in the pathway using promoters and RBSs of different strengths to balance flux and reduce burden [15] [24]. |

| Genetic Instability | Sequence plasmids from evolved populations to find common mutations. | Switch from plasmid-based to genome-integrated systems, or use advanced host strains with reduced recombination frequency [25]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Cloning Toolkits [24] | Provide standardized, interchangeable genetic parts (promoters, RBS, coding sequences, terminators) for rapid and predictable assembly. | Fast combinatorial testing of different regulatory element combinations to optimize pathway expression [24]. |

| Orthogonal Sigma Factors [15] | Bacterial transcription factors that recognize specific promoter sequences without cross-talking with the host's native regulation. | Creating insulated synthetic circuits that operate independently of the host's physiological state [15]. |

| CRISPR-Cas Genome Editing [24] | Enables precise deletion, replacement, or insertion of genetic sequences into the host genome. | Replacing native promoters or entire gene clusters with refactored synthetic versions at their native chromosomal locus [24]. |

| Riboswitch Libraries | Synthetic RNA elements that regulate gene expression in response to specific small molecules or environmental cues. | Implementing dynamic, metabolite-responsive control without relying on native protein transcription factors. |

| Genomically Recoded Organisms (GROs) [25] | Host organisms with reassigned codons that allow for genetic isolation and incorporation of non-standard amino acids. | Creating biocontained strains resistant to viral infection and horizontal gene transfer, enhancing experimental stability [25]. |

Experimental Workflows & Pathway Diagrams

Diagram: Native vs. Refactored Gene Cluster

Diagram: Troubleshooting Workflow for Low Expression

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Problems and Solutions in Host Transfer Experiments

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Host Transfer and Chassis Selection

| Problem | Common Symptoms | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Transfer Efficiency | Low conjugation frequency, failed plasmid establishment. | Incompatible origin of replication, restriction-modification systems [26]. | Use broad-host-range vectors (e.g., SEVA plasmids); confirm optimal conjugation temperature (e.g., 14-30°C for HI plasmids) [27]. |

| Unstable Genetic Construct | Plasmid loss over generations, inconsistent expression. | Resource competition, metabolic burden, genetic incompatibility [26] [28]. | Implement selective pressure; optimize genetic parts (promoters, RBS) for new host; reduce metabolic burden [24]. |

| Chassis-Specific Expression Variation | Different output signal strength, response time, or growth burden in new host [26]. | The "chassis effect": host-specific resource allocation, regulatory crosstalk [26]. | Treat chassis as a tunable module; systematically test circuit performance across multiple hosts during design [26]. |

| High Mutational Burden | Probiotic strains acquire numerous mutations in complex microbial environments [28]. | Keen microbial competition as a predominant evolutionary force [28]. | Pre-adapt probiotics to relevant metabolic environments; use chassis with high genetic stability. |

| Unintended Genetic Changes | Off-target effects in genetically engineered hosts [29] [30]. | CRISPR-Cas9 off-target activity, imperfect specificity [30]. | Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants; employ CIRCLE-seq for off-target screening; optimize gRNA design [30]. |

FAQs: Addressing Specific Experimental Issues

Q1: What is the "chassis effect" and how can I account for it in my experimental design?

The "chassis effect" refers to the phenomenon where the same genetic construct exhibits different behaviors depending on the host organism it operates within. This is influenced by host-specific factors like resource allocation, metabolic interactions, and regulatory crosstalk [26]. To account for this:

- Treat the chassis as a design parameter: Select hosts based on innate traits (e.g., photosynthesis, thermotolerance) that align with your application [26].

- Systematic Testing: Characterize your genetic device (e.g., inducible switches) across multiple bacterial species to understand how host selection influences performance metrics like output strength and response time [26].

- Use Modular Tools: Employ broad-host-range genetic tools, such as the Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA), which are designed for better cross-species predictability [26].

Q2: How does the native gut microbiome influence the genetic evolution of an engineered probiotic strain?

The native microbiome is a dominant force. In one study, the host's own factors (e.g., stomach acidity, immune response) contributed to less than 0.25% of the potentially adaptive mutations observed in probiotic strains. In contrast, microbial ecological factors and resource competition accounted for over 99.75% of the mutations, driving rapid and divergent genetic evolution within just seven days of colonization [28]. This indicates that microbial competition is a far more significant selective pressure than host-derived factors.

Q3: What are the key genetic elements to engineer for improved cross-species compatibility?

Table 2: Key Genetic Elements for Cross-Species Compatibility

| Genetic Element | Function | Engineering Consideration for Broad-Host-Range |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter | Initiates transcription. | Use host-agnostic or synthetic promoters that function across diverse taxonomic groups [26] [24]. |

| Origin of Replication (ori) | Controls plasmid copy number and host range. | Select from broad-host-range incompatibility groups (e.g., HI, M, N, Pα, T, W) [27]. |

| Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) | Initiates translation. | Optimize sequence for compatibility with the translational machinery of the target host [24]. |

| Terminator | Ends transcription. | Ensures proper transcription termination and prevents read-through in the new host [24]. |

| Signal Peptides | Directs protein secretion. | Must be recognized by the host's secretion machinery (Sec or Tat pathways) [24]. |

Q4: Which genome-editing tool is most suitable for precise modifications in non-model prokaryotes?

The CRISPR-Cas system is widely regarded as the most efficient tool due to its high precision, simplicity of assembly, and broad target selection compared to older technologies like ZFNs and TALENs [30]. For non-model prokaryotes, consider:

- CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): For reversible gene knockdown without DNA cleavage.

- CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa): To upregulate gene expression, useful for activating dormant biosynthetic gene clusters [30].

- High-Fidelity Cas Variants: To minimize off-target effects in new host environments [30].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Quantifying Host and Microbiome Contribution to Probiotic Evolution

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating the genetic evolution of probiotics Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HNU082 (Lp082) and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis V9 (BV9) [28].

Objective: To separate and quantify the selection pressures exerted by host factors versus the native microbiome on ingested probiotic strains.

Workflow:

Key Steps:

- Model Setup: Use two groups of mice: Germ-Free (GF) and Specific Pathogen-Free (SPF). The GF mice experience selection pressure only from host factors, while the SPF mice experience pressure from both host factors and a complex native microbiome [28].

- Probiotic Administration: Orally administer a defined dose (e.g., 10⁸ CFU/day) of the probiotic strain to both mouse groups for seven days [28].

- Sampling and Isolation: Collect fecal samples every two days. Isolate the probiotic strains from the feces using strain-specific antibiotics and primers to confirm identity [28].

- Genomic Analysis: Perform whole-genome sequencing on the isolated probiotic colonies. Map the sequences against the genome of the original probiotic strain to identify Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) and other mutations [28].

- Data Interpretation:

- Mutations found in isolates from GF mice are attributed to host factors.

- Mutations found in isolates from SPF mice are attributed to both host and microbial factors.

- The relative contribution can be calculated quantitatively. For example, if GF isolates have 15 mutations and SPF isolates have 21,600 mutations, the host contribution is ~0.07% [28].

Quantitative Data on Evolutionary Pressures

Table 3: Mutations in Probiotics from Different Selective Pressures [28]

| Probiotic Strain | Total Mutations (SPF Mice) | Mutations from Host Factors (GF Mice) | Calculated Host Contribution | Calculated Microbiome Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. plantarum HNU082 | 840 | 10 | 1.19% | 98.81% |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis V9 | 21,579 | 13 | 0.06% | 99.94% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| SEVA (Standard European Vector Architecture) Plasmids | Modular, broad-host-range vector system for genetic construct design and transfer [26]. | Standardized parts, facilitates swapping of origins of replication for different host ranges. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System (with high-fidelity variants) | Precision genome editing for pathway optimization and gene knockout/activation in new chassis [30]. | Enables targeted modifications; high-fidelity variants reduce off-target effects. |

| Broad-Host-Range Conjugative Plasmids (e.g., Inc HI, M, N) | Facilitate plasmid transfer between diverse bacterial species, especially at sub-optimal temperatures [27]. | Thermosensitive conjugation (optimal at 14-30°C); can encode multiple antibiotic resistance. |

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) & Machine Learning (ML) Tools | Predict metabolic network interactions, optimize genetic part function (promoters, RBS), and design biosynthetic pathways [24] [30]. | Accelerates the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle; improves prediction accuracy. |

| Biofoundry Automation | Integrated, high-throughput facility to automate the DBTL cycle for strain engineering and characterization [31]. | Uses robotic automation and computational analytics to rapidly prototype and test genetic designs across multiple hosts. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

The Host Transfer and Optimization Workflow

The Biofoundry DBTL Cycle for Systematic Engineering

Bacterial Microcompartments (MCPs) are protein-based organelles found in many bacteria, functioning as nanobioreactors to enhance metabolic pathways. They consist of a protein shell that encapsulates a core of metabolic enzymes. This structure allows bacteria to sequester toxic or volatile metabolic intermediates, increase local enzyme and substrate concentrations, and create private cofactor pools, thereby improving pathway efficiency and cellular fitness [32]. The 1,2-propanediol utilization (Pdu) MCP is one of the best-characterized metabolosomes. It natively encapsulates the pathway for degrading 1,2-propanediol, sequestering the toxic intermediate propionaldehyde to prevent cellular damage [32] [33]. For metabolic engineers, MCPs offer a powerful strategy to optimize heterologous pathways, mitigate toxicity, and divert flux toward desired products by creating a specialized, controlled environment within the cell [32] [33].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary benefits of encapsulating a metabolic pathway within a bacterial microcompartment? Encapsulation within an MCP provides three major benefits:

- Sequestration of Toxic Intermediates: The protein shell acts as a selective diffusion barrier, preventing harmful intermediates from escaping and damaging the cell while allowing substrates to enter [32] [33].

- Increased Local Concentrations: Confining enzymes and intermediates within a small volume enhances reaction rates and pathway flux [32].

- Cofactor Pool Isolation: MCPs can encapsulate enzymes that recycle essential cofactors (e.g., NAD+, CoA), creating a private pool that minimizes competition with host metabolism [32].

Q2: How can I engineer an MCP to encapsulate a heterologous pathway of interest? Heterologous enzyme encapsulation is typically achieved by fusing a targeting signal from a native MCP cargo protein to your enzyme of interest. For the Pdu MCP, short peptide sequences from core enzymes are sufficient to direct heterologous proteins to the lumen [32]. These fusion proteins are then co-expressed with the genes for the MCP shell proteins.