Microbial Taxonomy and Phylogeny: Genomic Foundations for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles and modern methodologies shaping microbial taxonomy and phylogeny.

Microbial Taxonomy and Phylogeny: Genomic Foundations for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles and modern methodologies shaping microbial taxonomy and phylogeny. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the revolutionary shift from phenotype-based classification to genome-driven systematics. The content spans foundational concepts, cutting-edge genomic techniques, challenges in classification, and the critical application of these frameworks in validating microbial identity for biomedical and industrial applications. By synthesizing exploratory, methodological, troubleshooting, and validation intents, this article serves as a foundational guide for leveraging microbial systematics in advanced research and development.

From Linnaean Roots to Genomic Revolution: Exploring the Core Principles of Microbial Systematics

In the era of high-throughput sequencing, the scientific disciplines of microbial taxonomy, phylogeny, and systematics have become foundational to modern microbiology research and its applications in drug development and biotechnology. These interconnected fields provide the essential framework for identifying, naming, classifying, and understanding the evolutionary relationships among microorganisms. For researchers and scientists working with microbial biologicals, precise classification is not merely academic—it directly impacts regulatory pathways, risk assessment, and the commercial development of microbial-based products [1]. The rapid expansion of genomic databases has fundamentally transformed our understanding of microbial diversity and evolution, revealing that natural microbial innovation occurs primarily through horizontal gene transfer, blurring traditional distinctions between "natural" and "genetically modified" organisms in regulatory contexts [1]. This technical guide examines the core principles, current methodologies, and practical applications of these organizing sciences within the framework of microbial research.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Taxonomy: The Identification and Classification System

Microbial taxonomy is the theoretical and practical framework for the identification, classification, and nomenclature of microorganisms [2]. It provides a systematic approach to organizing microbial diversity based on shared characteristics and evolutionary relationships. Taxonomy operates within a hierarchical structure that ranges from broad, inclusive categories to specific, exclusive ones, with species as the fundamental unit of classification [3]. A species is typically defined as a collection of microbial strains that share key characteristics and exhibit a high degree of genetic similarity, often quantified through metrics such as Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) [1]. The naming of microorganisms follows the binomial system of genus and species, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis [3].

The practice of microbial taxonomy has evolved significantly from early phenotypic characterizations (morphology, biochemical testing) to modern genome-based classification systems [1]. This shift has been driven by the recognition that phenotypic approaches are limited in their ability to elucidate true evolutionary relationships, as distantly related microbes can share features due to convergent evolution or habitat-specific adaptations [1]. The pangenome concept has further refined our understanding of microbial species by distinguishing between the core genome (genes universal to a lineage) and the accessory genome (variable genes that reflect functional adaptations) [1].

Phylogeny: The Evolutionary History

Phylogeny represents the evolutionary history and relationships among species, genes, and populations, typically visualized through phylogenetic trees [4]. This field uses comparative genomics to reconstruct the evolutionary pathways that have led to the diversification of microbial life. Phylogenetic analyses rely on the comparison of genetic sequences, with the 16S rRNA gene serving as a cornerstone for bacterial and archaeal phylogeny due to its slow evolutionary rate and universal distribution across these domains [1].

The construction of phylogenetic trees involves multiple steps, including sequence alignment, model selection, and tree inference, with the resulting trees being described as either rooted (showing evolutionary direction) or unrooted (showing only relationships) [4]. Key concepts in phylogeny include homologous sequences (genes shared through common ancestry), clades (groups of organisms descended from a common ancestor), and genetic distance (the degree of genetic divergence between taxa) [4]. For microbiomes, phylogenetic trees can be constructed from 16S rRNA sequencing data or whole genome shotgun sequencing, with each approach having distinct strengths and limitations for analyzing microbial community structures and functions [5].

Systematics: The Comprehensive Study of Diversity

Systematics encompasses the comprehensive study of organismal diversity and evolutionary relationships, integrating data from taxonomy, phylogeny, morphology, ecology, and genomics [6]. The field is dedicated to advancing microbial systematics through research, collaboration, and knowledge dissemination, as exemplified by organizations like the Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology and the International Society for Microbial Systematics (BISMiS) [6] [3].

Microbial systematics employs a polyphasic approach that combines genotypic, phenotypic, and phylogenetic information to classify microorganisms [3]. This integrated methodology is particularly important for reconciling the challenges posed by extensive horizontal gene transfer in microbes, which can result in discordance between evolutionary histories of different genes within the same organism [1]. Systematics provides the theoretical foundation for taxonomic frameworks and nomenclatural systems that enable researchers to communicate consistently about microbial diversity.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Disciplines in Microbial Organization

| Discipline | Primary Focus | Key Methods | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomy | Identification, classification, and nomenclature of microorganisms | Phenotypic characterization, DNA-DNA hybridization, Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) | Hierarchical classification (species, genus, family, etc.), Binomial names |

| Phylogeny | Evolutionary history and relationships | Sequence alignment, phylogenetic tree construction, comparative genomics | Phylogenetic trees, evolutionary models, genetic distances |

| Systematics | Comprehensive study of organismal diversity | Integrated polyphasic approach (genotypic, phenotypic, phylogenetic) | Taxonomic frameworks, nomenclatural systems, evolutionary hypotheses |

Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Taxonomic Classification Techniques

Modern microbial taxonomy employs a suite of genomic tools and computational approaches for taxonomic classification, which are essential for binning and metagenomic analysis [2]. The development of novel algorithms and databases continues to enhance the precision and scalability of microbial classification systems. Current methods include:

- Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI): A standard metric for species delineation based on whole-genome comparisons, with thresholds typically set at 95-96% for species boundaries [1].

- Multi-Locus Sequence Analysis (MLSA): Utilizes sequences of multiple housekeeping genes to provide better resolution than single-gene approaches.

- Pangenome Analysis: Distinguishes between core and accessory genomes to understand the genetic diversity within taxonomic groups [1].

- Digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH): A computational alternative to traditional laboratory-based DNA hybridization methods.

The Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology remains a cornerstone resource for prokaryotic taxonomy, providing comprehensive descriptions of bacterial and archaeal taxa [3]. However, the field faces ongoing challenges, including the fact that an estimated 85% of microbial life remains unculturable, limiting phenotypic characterization [1]. For these uncultured lineages, taxonomy must rely solely on sequence-based classifications from metagenome-assembled genomes and single-cell genomics [1].

Phylogenetic Tree Construction

Phylogenetic reconstruction from microbiome data presents distinct challenges and opportunities based on the sequencing approach employed. For 16S rRNA sequencing, established tools leverage the highly conserved nature of this marker gene, while whole-genome shotgun sequencing requires more complex approaches due to the vast diversity of genomic regions [5]. The phylogenetic tree construction workflow typically involves:

- Sequence Acquisition: Obtaining 16S rRNA or whole-genome sequences from microbial isolates or metagenomic samples.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Aligning homologous sequences using tools such as PASTA, MUSCLE, or MAFFT [7].

- Model Selection: Identifying the most appropriate evolutionary model for the dataset.

- Tree Inference: Constructing trees using methods like maximum likelihood, Bayesian inference, or neighbor-joining.

- Tree Evaluation: Assessing tree robustness through bootstrap analysis or posterior probabilities.

Recent innovations have demonstrated that citizen science approaches integrated into video games can significantly improve multiple sequence alignment quality, leading to enhanced phylogenetic estimates for microbial communities [7]. Such crowd-sourced approaches have solved millions of alignment puzzles, achieving improvements over state-of-the-art computational methods alone [7].

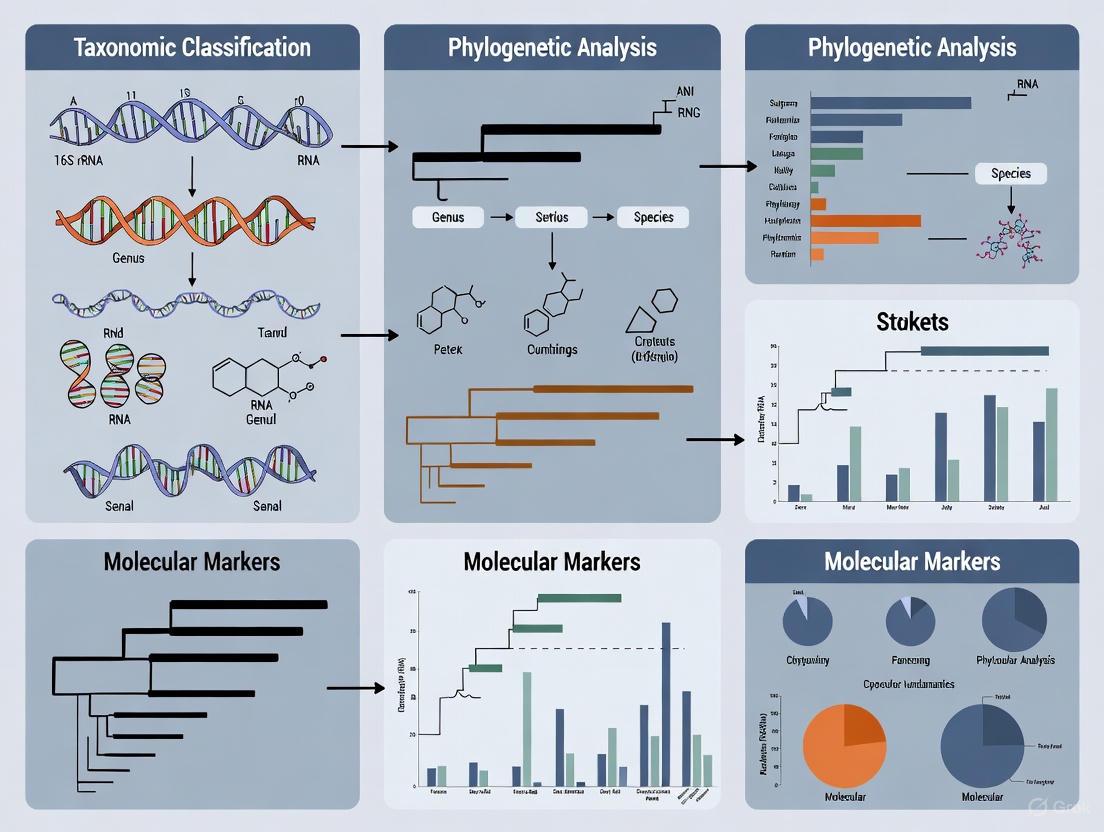

Figure 1: Workflow for Phylogenetic Tree Construction from Microbial Sequence Data

Integrated Systematic Frameworks

Systematics employs integrated frameworks that combine data from multiple sources to develop robust classifications that reflect evolutionary history. Key approaches include:

- Polyphasic Taxonomy: Combines phenotypic, genotypic, and phylogenetic data to delineate taxonomic groups.

- Phylogenomic Analysis: Uses large-scale genomic datasets to infer evolutionary relationships with greater accuracy than single-gene phylogenies.

- Comparative Genomics: Identifies shared and unique genomic features across taxa to understand functional and evolutionary relationships.

The dynamic nature of microbial genomes, particularly the prevalence of horizontal gene transfer (HGT), presents both challenges and opportunities for systematics. HGT is now recognized as a dominant mechanism of genetic innovation in bacteria and archaea, facilitating the natural exchange of genetic material between distantly related taxa [1]. This reality complicates phylogenetic reconstruction, as different genes within the same organism may have distinct evolutionary histories. Modern systematics must therefore account for these complex patterns of gene flow when reconstructing microbial evolutionary history.

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Microbial Discovery and Characterization

The systematic organization of microbial life enables the discovery and characterization of novel microorganisms with potential applications in drug development and biotechnology. Recent discoveries highlight the importance of robust taxonomic and phylogenetic frameworks:

- Bacteriovorax antarcticus: A novel bacterial predator isolated from Potter Cove, Antarctica, representing a group (BALOs) that is underrepresented in current taxonomic frameworks [8].

- Streptomyces cavernicola, S. solicavernae, S. luteolus: New Streptomyces species discovered in cave soil samples with potential for producing biologically active compounds, including antibiotics [8].

- Methanochimaera problematica: A novel hydrogenotrophic methanoarchaeon isolated from deep-sea cold seep sediments [8].

- Exophiala zingiberis: A novel cellulase-producing black yeast-like fungus isolated from ginger tubers [8].

The integration of citizen science initiatives with professional research has accelerated microbial discovery and classification. Projects like Borderlands Science have engaged millions of participants in solving multiple sequence alignment puzzles, resulting in improved phylogenetic trees for microbiome data [7]. This approach demonstrates how massive public participation can address computational challenges that are intractable for individual researchers or conventional algorithms.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Taxonomy and Phylogeny

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA PCR Primers | Amplification of 16S rRNA gene for phylogenetic analysis | Bacterial and archaeal identification, microbial community profiling |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Kits | Comprehensive genomic data acquisition | Pangenome analysis, phylogenomics, taxonomic delineation |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tools | Alignment of homologous sequences for phylogenetic analysis | PASTA, MUSCLE, MAFFT for tree construction [7] |

| Phylogenetic Tree Inference Software | Construction of evolutionary trees from sequence data | FastTree, RAxML, MrBayes for phylogenetic estimation [7] |

| Taxonomic Reference Databases | Reference sequences for taxonomic classification | Greengenes, Rfam, SILVA for sequence placement [7] |

Implications for Biotechnology and Regulatory Science

The principles of microbial taxonomy, phylogeny, and systematics have direct implications for biotechnology development and regulatory frameworks. Current risk assessment paradigms for microbial products often intensify scrutiny for organisms classified as genetically modified (GM) or containing novel combinations of genetic material (NCGM) [1]. However, genomic analyses reveal that horizontal gene transfer between different taxa is a natural and frequent occurrence in microbial evolution, suggesting that many microbes could be considered "naturally occurring GM organisms" [1].

This understanding has prompted calls for more science-based regulatory approaches that focus on the actual functions and phenotypic characteristics of microbes rather than their classification as GM or non-GM [1]. Such approaches would better align with the biological realities of microbial evolution and facilitate the development of effective microbial solutions for agricultural, industrial, and therapeutic applications. For drug development professionals, accurate taxonomic identification and phylogenetic placement are essential for understanding the functional potential, safety profile, and ecological roles of microbial isolates.

Future Directions and Challenges

The fields of microbial taxonomy, phylogeny, and systematics continue to evolve rapidly, driven by technological advances and new conceptual frameworks. Future developments include:

- Integration of Machine Learning: Application of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches to taxonomic classification and phylogenetic inference, potentially bridging paleontology and biology through advanced pattern recognition [9].

- Resolution of the Unculturables: Development of novel cultivation techniques and single-cell genomics approaches to access the vast diversity of currently unculturable microorganisms [1].

- Dynamic Classification Systems: Implementation of more flexible, dynamic taxonomic systems that can accommodate the fluid nature of microbial genomes and extensive horizontal gene transfer [1].

- Standardization and Collaboration: Enhanced international collaboration and standardization in microbial systematics, as promoted by organizations like BISMiS, which holds regular meetings and disseminates knowledge through publications and seminars [6].

The ongoing revision of microbial taxonomy in light of expanding genomic data will continue to reshape our understanding of the tree of life, with implications for all areas of microbiology and microbial biotechnology [1]. As these fields progress, they will provide increasingly powerful frameworks for organizing microbial life and harnessing microbial diversity for the benefit of human health, agriculture, and environmental sustainability.

Figure 2: Interrelationship Between Taxonomy, Phylogeny, Systematics, and Their Applications

The field of microbial taxonomy has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from a foundation built on observable phenotypic characteristics to one rooted in molecular and genomic data. This paradigm shift has fundamentally reshaped how researchers identify, classify, and understand the evolutionary relationships between microorganisms. The initial phenotypic approach, which relied on morphological, biochemical, and physiological characteristics, has been progressively supplemented and ultimately superseded by sequence-based methods that provide a more objective and quantitative framework for microbial classification [10] [1]. This transition began with the adoption of single-marker genes, most notably the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene, and has accelerated dramatically with the advent of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) technologies [10] [11]. The resulting genomic taxonomy framework now enables researchers to delineate species with unprecedented precision and reconstruct phylogenetic relationships with greater accuracy, thereby refining our understanding of microbial evolution and diversity [12] [11].

The Era of Phenotypic Classification

Initially, microbial taxonomy was grounded almost exclusively in phenotypic characterizations. These included observable traits such as cellular morphology, Gram staining, biochemical capabilities (e.g., nutrient utilization and metabolic byproducts), growth conditions, and other cultural properties [1] [11]. This polyphasic approach was pragmatic for its time but inherently limited. A significant drawback was that distantly related microbes could share similar phenotypic traits due to convergent evolution or adaptation to similar niches, while closely related organisms might appear dissimilar [10] [1]. This often led to misclassification, as illustrated by the historical grouping of the genus Clostridium, which was united by common morphology and sporulation ability but was later found via molecular methods to represent dozens of phylogenetically distinct groups within the Firmicutes phylum [10]. The heavy reliance on the ability to culture microorganisms in the laboratory created a major bottleneck, leaving the vast majority (>80%) of microbial diversity—often referred to as "microbial dark matter"—unexplored and unclassified [10] [1].

The Molecular Revolution: Single Gene Markers and Beyond

The discovery of the 16S rRNA gene as a phylogenetic marker by Carl Woese in the 1970s marked a pivotal turning point [10] [13]. This gene offered several ideal properties: it is universally present across Bacteria and Archaea, its function is constant, and its sequence contains both highly conserved regions (useful for alignment) and variable regions (useful for distinguishing taxa) [10]. The comparison of 16S rRNA sequences led to the fundamental reorganization of the tree of life into three domains—Bacteria, Archaea, and Eucarya—overturning the previous phenotype-based schema that placed all microbes at the base of the tree [10] [13].

The use of DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) became the gold standard for delineating bacterial species, with a threshold of ≥70% similarity used to define a species [11]. However, DDH was labor-intensive, difficult to standardize, and not easily scalable. The development of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Sanger sequencing subsequently enabled the wider use of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for microbial identification and phylogenetic inference, forming the backbone of microbial molecular ecology for decades [10]. Despite its revolutionary impact, 16S rRNA gene sequencing had limitations, including poor phylogenetic resolution at the species level, inadequate reference databases, and the susceptibility of the gene to horizontal gene transfer and recombination events, which sometimes obscured true evolutionary relationships [10].

Table 1: Key Transitions in Microbial Taxonomy

| Era | Primary Tools & Data | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotypic | Morphology, biochemistry, growth requirements | Low-tech, functional insights | Low resolution, culture-dependent, subjective |

| Single-Gene Molecular | 16S rRNA sequencing, DDH | Culture-independent, objective, universal marker | Poor species-level resolution, single gene history |

| Genomic | Whole Genome Sequencing, ANI, dDDH, Core Genome Analysis | High resolution, comprehensive, digital, reproducible | Cost, computational demands, data management |

The Genomic Era: A New Taxonomy Framework

The advent of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has launched microbial taxonomy into a new era, enabling a systematics framework based on the comprehensive information retrieved from complete genomes [11]. This genomic taxonomy is not merely an enriched version of the polyphasic approach but is fundamentally framed on a robust genomic backbone.

Genomic Species Delineation Metrics

A key development has been establishing computational metrics to replace traditional methods like DDH. The most widely adopted of these is Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI), which provides a robust, digital measure of genomic relatedness. Studies have shown that an ANI of approximately 95% corresponds to the traditional 70% DDH threshold for species demarcation [11]. Average Amino Acid Identity (AAI), which calculates the average identity of all orthologous protein-coding genes shared between two genomes, serves a similar purpose for functional genomic relatedness [11]. Complementing these, the Karlin genomic signature (δ), which measures the difference in dinucleotide relative abundance between genomes, provides a species-specific compositional signature reflecting underlying differences in DNA structure and repair mechanisms [11]. Finally, *in silico Genome-to-Genome Distance Hybridization (GGDH or dDDH) calculates genome-to-genome distances based on high-scoring segment pairs (HSPs) from whole-genome comparisons, effectively digitalizing the wet-lab DDH process [11].

Table 2: Genomic Standards for Species and Genus Delineation

| Taxonomic Rank | Genomic Standard | Typical Threshold | Method Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) | >95% [11] | Average nucleotide identity of all orthologous genes shared between two genomes. |

| In silico DDH (GGDH/dDDH) | >70% [11] | Computational simulation of DNA-DNA hybridization using genome sequences. | |

| Karlin Genomic Signature (δ*) | <10 [11] | Measure of dissimilarity in dinucleotide relative abundance between two genomes. | |

| Genus | 16S rRNA Gene Identity | >95% [11] | Historically used, but now supplemented by genome-based phylogenies. |

| Multilocus Sequence Analysis (MLSA) | Monophyletic Group [11] | Phylogenetic analysis based on concatenated sequences of multiple core protein-coding genes. | |

| Supertree / Core Genome Phylogeny | Monophyletic Group [11] | Phylogenetic tree constructed from the alignment of all genes in the core genome. |

The Pangenome Concept and Phylogenomics

The genomic era has also introduced the pangenome concept, which divides the total gene content of a lineage into the core genome (genes shared by all strains) and the accessory genome (genes present in some but not all strains) [1]. The core genome, comprising genes essential for basic cellular functions, is typically vertically inherited and is therefore highly suitable for constructing robust phylogenies for taxonomic ranking (phylogenomics) [1]. In contrast, the accessory genome, which can constitute over 80% of a lineage's gene content, is often acquired through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and confers adaptive traits for specific lifestyles [1]. This dynamic nature of microbial genomes, with constant genetic flux through HGT, challenges traditional taxonomic views and risk assessment frameworks that rely on fixed genetic definitions [1].

Advanced Genomic Workflows and Marker Selection

For modern phylogenomic studies, especially those involving non-cultivable microorganisms, the process begins with obtaining genomes from metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) or single-cell genomics [12] [10]. Metagenomic binning strategies that leverage differential abundance patterns of populations across multiple samples have proven highly effective, routinely producing high-quality population genomes (>80% complete, <10% contaminated) [10]. These MAGs, however, seldom contain the full genomic repertoire of a population and can lack standard marker genes due to assembly errors, necessitating flexible methods for phylogenetic analysis [12].

To address the limitations of using a fixed set of universal marker genes, advanced computational tools like TMarSel (Tailored Marker Selection) have been developed [12]. This software performs an automated, tailored selection of phylogenetic marker genes from the entire pool of gene families (e.g., from KEGG and EggNOG databases) present in an input genome collection. It builds a copy-number matrix of gene families across genomes and employs an algorithm to iteratively select k markers that maximize the generalized mean number of markers per genome, thereby improving the accuracy of downstream phylogenetic trees, even with taxonomically imbalanced or incomplete MAGs [12]. The selected markers are then used to infer a species tree using summary methods like ASTRAL-Pro2, which can handle multi-copy gene families [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Genomic Taxonomy

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High-Quality DNA Extraction Kits | To obtain pure, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from microbial cultures or environmental samples for WGS and MAG generation. |

| Metagenomic DNA Library Prep Kits | For preparing sequencing libraries from complex environmental DNA, enabling the reconstruction of MAGs. |

| 16S rRNA Gene PCR Primers | For amplifying and sequencing the 16S rRNA gene from bacterial and archaeal isolates, providing initial phylogenetic placement. |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Services | Providing high-throughput sequencing platforms (e.g., Illumina, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) to generate raw genomic data. |

| Bioinformatics Software (KEGG, EggNOG) | Databases and tools for functional annotation of open reading frames (ORFs) into gene families, essential for marker selection [12]. |

| Phylogenetic Software (ASTRAL-Pro2) | Summary method software for inferring species trees from a set of gene trees, accounting for gene duplication and loss [12]. |

| Taxonomic Classification Databases (GTDB) | Genome-centric databases providing a standardized microbial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny for accurate classification [14]. |

| Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) Calculator | Computational tool for calculating ANI between genome pairs to determine species boundaries [11]. |

The historical shift from phenotypic characteristics to molecular and genomic data represents a fundamental maturation of microbial taxonomy into a more objective, quantitative, and robust scientific discipline. This transition, driven by technological advances in sequencing and bioinformatics, has resolved long-standing taxonomic errors and unveiled the vast, previously hidden diversity of the microbial world. The modern framework of genomic taxonomy, with its standardized metrics like ANI and its ability to leverage entire genome sequences for phylogenetics, provides an unprecedented capacity to delineate species and reconstruct evolutionary history. As genomic databases continue to expand and computational methods become more sophisticated, the integration of taxonomic classification with functional and ecological data will further deepen our understanding of microbial evolution and its practical applications in medicine, biotechnology, and environmental science.

This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of the hierarchical framework of biological classification, with a specialized focus on its application in microbial taxonomy and phylogeny. We detail the core taxonomic ranks—from domain to strain—contextualized within modern molecular methodologies essential for researchers in drug development and microbial science. The document integrates structured data summaries, standard experimental protocols for phylogenetic analysis, and visual workflows to serve as a foundational resource for fundamental research in microbial systematics.

Biological taxonomy is the scientific discipline of classifying organisms into a hierarchical system that reflects evolutionary relationships. The relative or absolute level of a group of organisms (a taxon) in this hierarchy is known as its taxonomic rank [15]. This system organizes life from the most inclusive groups, such as domains, down to the most specific, like species and strains, providing a standardized framework for scientific communication. The science of naming and classifying organisms is rooted in the work of Carl Linnaeus, who established the binomial nomenclature system in the 18th century [16].

Within the context of microbial research, accurate classification is paramount. It enables researchers to identify pathogens, understand microbial ecology in the human microbiome, and trace the origins of antibiotic resistance. The transition from phenomenological classification based on appearance to methods grounded in cladistics and molecular systematics has revolutionized taxonomy, particularly for prokaryotes, which often lack distinguishing morphological traits [15] [17]. For drug development professionals, a precise understanding of this hierarchy is not merely academic; it informs target selection, vaccine development, and the tracking of disease outbreaks at a molecular level.

The Core Taxonomic Ranks

The modern taxonomic system is built upon a series of obligatory ranks. The seven main ranks, from most general to most specific, are: kingdom, phylum/division, class, order, family, genus, and species [15] [16]. The introduction of genetic analysis led to the addition of the domain as the highest rank, a fundamental division that supersedes the kingdom level [16]. The principle underlying this hierarchy is that each subsequent level represents a group of organisms sharing a more recent common ancestor and, consequently, a greater number of shared characteristics.

Table 1: Primary Taxonomic Ranks and Their Characteristics

| Rank | Latin Term | Key Characteristics | Microbial Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Dominium | Most fundamental cellular organization; separates Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya [15] [16] | Bacteria |

| Kingdom | Regnum | Major divisions within a domain (e.g., metabolic diversity) [18] | Monera (in traditional systems) |

| Phylum | Phylum | General body plan or fundamental genetic divergence [16] | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes |

| Class | Classis | Groups of related orders sharing common traits [18] | Bacilli, Clostridia |

| Order | Ordo | Groups of related families [16] | Lactobacillales, Bacillales |

| Family | Familia | Groups of related genera; often has standard suffix (e.g., -aceae) [15] |

Lactobacillaceae |

| Genus | Genus | Group of very closely related species [16] | Lactobacillus, Bacillus |

| Species | Species | Group of individuals that can interbreed (concept applied conceptually to microbes); basic unit of classification [16] | Lactobacillus acidophilus |

As one ascends the taxonomic hierarchy from species to domain, the number of organisms within each group increases, while the number of shared, specific characteristics decreases [18]. The species is the most fundamental unit, classically defined by the ability of members to successfully interbreed and produce fertile offspring—a concept adapted for prokaryotes through genetic and genomic criteria [16].

The Microbial Context: Domains Bacteria and Archaea

The classification of microbes operates within the same hierarchical framework but faces unique challenges due to their lack of complex morphology and the prevalence of horizontal gene transfer. The domain level, proposed by Carl Woese, is critical in microbiology. It separates all life into three groups: Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya, based on fundamental genetic and biochemical differences in cellular organization [17] [16]. This division established that the prokaryotes are not a single, monophyletic group, but are split into two fundamentally distinct domains.

Historically, bacterial classification was problematic and relied on phenotypic traits like Gram staining, leading to groups such as Gracilicutes (gram-negative) and Firmacutes (gram-positive) [17]. The advent of molecular phylogenetics, particularly the use of the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene as a molecular chronometer, provided a robust, quantitative method for determining evolutionary relationships and assigning taxonomic ranks to microbes [17] [19]. This allows for a classification that more accurately reflects evolutionary history.

Subranks and Strain-Level Classification

To address the need for finer resolution within major ranks, the taxonomic system allows for the creation of subranks. These are denoted by prefixes such as "sub-" or "super-". For example, between the family and genus ranks, one may find subfamily, tribe, and subtribe [15]. In botany, additional secondary ranks like section and series are used [15]. These subranks are essential for organizing biologically complex groups, providing granularity without altering the core seven-tiered system.

For microbial researchers, the most critical level of granularity is below the species, at the strain level. A strain represents a genetic variant or subtype of a species. Strains are often designated by alphanumeric codes and can differ in pathogenic potential, antibiotic resistance, or metabolic capabilities. For instance, Escherichia coli O157:H7 is a specific strain known for causing severe foodborne illness. While not a formal rank in the Linnaean hierarchy, the strain is a functional unit in laboratory and clinical settings, enabling precise communication about microbial isolates for diagnostics and therapy development.

Table 2: Common Subranks and Infraspecific Levels in Taxonomy

| Level | Prefix/Suffix | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superfamily | super- |

Grouping of related families | In zoology: Canoidea |

| Subfamily | -oideae (bot.), -inae (zoo.) |

Subdivision of a family | Pantherinae (big cats) |

| Tribe | -eae (bot.), -ini (zoo.) |

Subdivision of a subfamily | Heliantheae (sunflowers) |

| Subspecies | subsp. or ssp. |

Geographically isolated variants | Panthera tigris altaica (Siberian tiger) [16] |

| Strain | N/A | Genetic variant within a species; crucial for microbiology | Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM |

Methodologies for Phylogenetic Analysis in Microbiology

Experimental protocols for determining taxonomic placement and constructing phylogenetic trees for microbes rely heavily on molecular data. The following methodologies are foundational to the field.

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

Principle: The 16S ribosomal RNA gene is a component of the 30S small subunit of the prokaryotic ribosome. It contains highly conserved regions (for primer binding) and variable regions (for discrimination between taxa), making it an ideal marker gene for identifying and classifying bacteria and archaea [19].

Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from a pure bacterial culture or directly from an environmental sample (e.g., gut microbiome).

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the 16S rRNA gene using universal or domain-specific primers targeting the conserved regions.

- Sequencing: Purify the PCR product and perform Sanger sequencing for pure isolates or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for complex communities.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Filtering: Remove low-quality sequences and primers.

- Clustering: Cluster sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) based on similarity (e.g., 97% for species-level OTUs).

- Alignment: Align sequences against a reference database (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes).

- Tree Construction: Infer a phylogenetic tree using methods like Maximum Likelihood or Neighbor-Joining.

- Taxonomic Assignment: Assign taxonomy to each sequence or cluster by comparing it to a curated database of known 16S sequences.

Whole-Genome Shotgun (WGS) Metagenomics and Phylogenomics

Principle: This approach involves randomly shearing and sequencing all DNA from a sample, providing access to all genes, not just a single marker. Phylogenomics uses information from multiple genes or entire genomes to infer evolutionary relationships, offering much higher resolution than single-gene analysis [5].

Protocol:

- Library Preparation: Fragment total community DNA, ligate adapters, and prepare a sequencing library without a PCR amplification step targeting a specific gene.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence the library using an Illumina, Ion Torrent, or other NGS platform.

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Assembly: De novo assemble reads into longer contigs, or map reads to a reference database.

- Binning: Group contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) based on sequence composition and abundance.

- Gene Calling & Annotation: Predict open reading frames and annotate their function.

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction:

- Identify a set of single-copy core genes present in the MAGs and reference genomes.

- Concatenate the protein or nucleotide sequences of these genes.

- Construct a phylogenetic tree from the concatenated alignment using robust methods like Maximum Likelihood.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Microbial Phylogenetics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Universal 16S rRNA Primers | PCR amplification of the 16S gene from a broad range of prokaryotes [19] | Initial amplification for community profiling or isolate identification. |

| DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., for stool, soil) | Standardized protocols for lysing diverse cell types and purifying nucleic acids. | Extracting high-quality, inhibitor-free DNA from complex microbial samples. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification of DNA templates with low error rates. | Critical for PCR steps prior to sequencing to avoid introduction of errors. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | Library preparation and sequencing reagents for platforms like Illumina. | Generating the raw sequence data for WGS metagenomics or 16S amplicon sequencing. |

| Bioinformatic Databases (e.g., SILVA, GTDB) | Curated collections of reference sequences and taxonomic information. | Taxonomic assignment of query sequences and phylogenetic tree rooting. |

| Bioinformatic Software (e.g., QIIME 2, Mothur, PhyloPhlAn) | Integrated suites for processing raw sequence data, building OTU/ASV tables, and constructing phylogenetic trees [5]. | Performing end-to-end analysis from raw sequences to ecological statistics and phylogenies. |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite advances, microbial taxonomy faces significant challenges. The species concept remains problematic for prokaryotes, leading to the use of operational definitions like the 95-96% average nucleotide identity (ANI) threshold [19]. Furthermore, the vast majority of microbial diversity is uncultured, meaning taxonomic classifications are often based solely on sequence data from environmental samples. The lack of robust tools for constructing phylogenetic trees from WGS data, compared to the well-established 16S pipeline, also presents a hurdle for researchers, particularly those in downstream fields like statistics and machine learning [5].

Future progress will depend on standardizing methods for phylogenomic analysis and integrating them into user-friendly pipelines. The expansion of comprehensive reference databases like the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) is crucial for accurate taxonomic placement. For drug development, the move towards strain-level analysis will be essential for understanding virulence and developing targeted therapies. The integration of phylogenetic information into statistical models of microbiome data is an active area of research, promising improved accuracy in linking microbial communities to host health and disease states [19] [5].

The taxonomy of prokaryotes has long presented a fundamental challenge to microbiologists. Unlike animals and plants, where sexual reproduction provides a natural framework for defining species through genetic cohesion, prokaryotes do not engage in sexual reproduction stricto sensu, making species definition more elusive [20]. This discrepancy has even led some to suggest that bacteria cannot and need not be organized into species, instead representing a series of organisms with different divergence levels reflecting their evolutionary history [20]. However, in practice, microbiologists can consistently recognize and designate bacterial isolates based on phenotypic characteristics, and genomic comparisons reveal that bacteria form clear clusters of highly related individuals rather than showing a scattered distribution [20]. This paradox highlights the complexity of establishing a biologically relevant species concept for prokaryotes that accommodates their unique genomic architectures and evolutionary mechanisms.

The development of prokaryotic taxonomy has been delayed relative to macroscopic organisms, due in part to technical limitations and the historical focus of evolutionary biologists on sexual organisms [20]. Early microbiologists relied exclusively on phenotypic traits to characterize and classify bacteria, similar to approaches used by naturalists for animals and plants [20]. However, the discovery that phenotypic traits could be transmitted horizontally between bacterial cells revealed a profound difference from macroscopic organisms, where traits are almost exclusively inherited vertically [20]. This early observation foreshadowed our current understanding of the extensive role horizontal gene transfer plays in bacterial evolution and the challenges it presents for species definition.

Theoretical Frameworks: From Phenotype to Genotype

Historical Concepts and Their Limitations

Initial approaches to prokaryotic classification relied heavily on phenotypic observations, drawing parallels with early taxonomic methods for animals and plants. This phenotypic approach presented immediate challenges, as demonstrated by the seminal work of Oswald Avery and colleagues, which not only identified DNA as the support of heredity but also showed that phenotypic traits could be transmitted horizontally between bacterial cells [20]. This fundamental difference from macroscopic organisms, where traits are primarily inherited vertically, underscored the need for alternative classification frameworks.

Before the genomic era, species membership was established through DNA-DNA hybridization assays, which compared newly isolated strains to reference strains [20]. The recommended threshold for species membership was set at 70% genomic hybridization [20]. While pragmatic, this approach offered limited insight into the evolutionary processes maintaining species boundaries. The method was technically demanding and not easily scalable, restricting its utility for comprehensive taxonomic studies across diverse prokaryotic lineages.

The Rise of Sequence-Based Thresholds

The emergence of sequencing technologies led to the development of more scalable, sequence-based approaches for species designation. The 16S rRNA subunit, identified as a universal gene shared by all bacteria and archaea, offered the possibility of assessing prokaryotic species membership with a standardized marker across all lineages [20]. Analysis revealed that the 70% identity threshold from DNA-DNA hybridization assays corresponded approximately to 97% identity when using the 16S rRNA subunit [20]. This method became particularly popular with the rise of metagenomic sequencing, enabling taxonomic profiling without cultivation.

A more recent and powerful approach utilizes entire genomes to calculate Average Nucleotide Identity across all shared genes relative to a reference genome [20]. The ANI threshold for species membership has been empirically defined as 95%, based on correlations with established sequence thresholds [20]. This method provides higher resolution than 16S rRNA sequencing and has emerged as a robust standard for species delineation in the genomic era.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Species Delineation Methods in Prokaryotic Taxonomy

| Method | Genetic Basis | Threshold | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-DNA Hybridization | Whole-genome similarity | 70% hybridization | Established standard; phenotypic correlation | Technically demanding; not scalable |

| 16S rRNA Identity | Single gene sequence | 97% identity | Universal marker; enables metagenomic analysis | Limited resolution; conserved nature |

| Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) | Whole-genome comparison | 95% identity | High resolution; scalable; portable | Requires genome sequencing; computational resources |

The Genomic Revolution: Pangenomes and Species Boundaries

The Pangenome Concept

The development of genomic techniques revealed profound differences between prokaryotic genomes and those of animals and plants. Related bacteria can differ dramatically in their gene content, with a typical bacterial species comprising both a set of ubiquitous, highly similar core genes and a set of accessory genes with a scattered distribution [20]. The pangenome represents the total gene diversity of a population, encompassing all distinct orthologs, including both core and accessory genes [20].

Escherichia coli provides a compelling illustration of prokaryotic genomic versatility. The model strain K12 MG1655 contains approximately 4,400 genes, while other strains may contain up to an additional 1,000 genes encoding diverse functions [20]. Comparisons of just 20 E. coli strains reveal a core genome of approximately 2,000 genes, while the pangenome approaches 18,000 genes [20]. Remarkably, over 50% of genes in a single E. coli strain consist of accessory genes lacking orthologs in most other strains. These accessory genes are frequently exchanged between strains and often determine specific lifestyles and ecologies, ranging from environmental to commensal or pathogenic [20].

Resolving Taxonomic Ambiguity Through Genomics

Genomic approaches have revealed instances where phenotype-based classifications misrepresent evolutionary relationships. The case of Shigella provides a particularly illustrative example. This bacterial "genus" comprises four recognized species (S. flexneri, S. boydii, S. sonnei, and S. dysenteriae) grouped based on shared phenotypic properties as obligate pathogens [20]. However, genomic analyses demonstrate that Shigella shares the same core genome as E. coli with >98% sequence identity across core genes, and core-genome phylogenies reveal that Shigella does not form a monophyletic clade [20]. What unites Shigella is the presence of shared virulence genes acquired through horizontal gene transfer, along with characteristic serology and metabolic capabilities [20]. Genomically, Shigella constitutes a subset of E. coli strains with a shared phenotype conferred by independent gains of common accessory genes. While taxonomically still recognized as separate, this example highlights the challenge of reconciling phenotypic and genomic classifications.

Clear Species Boundaries Revealed by Large-Scale Genomic Analysis

Comprehensive analyses of prokaryotic genomes have fundamentally addressed the question of whether genetic continua or clear species boundaries prevail in the microbial world. A landmark study performing high-throughput ANI analysis of 90,000 prokaryotic genomes revealed clear genetic discontinuities, with 99.8% of approximately 8 billion genome pairs conforming to >95% intra-species and <83% inter-species ANI values [21]. This striking pattern demonstrates that despite horizontal gene transfer, discrete clusters of genetically related individuals prevail across diverse prokaryotic lineages.

The development of FastANI, a rapid algorithm for ANI estimation using alignment-free approximate sequence mapping, has enabled this unprecedented scale of analysis [21]. FastANI achieves near-perfect linear correlation with alignment-based ANI methods while being orders of magnitude faster, making large-scale taxonomic analyses feasible [21]. This approach maintains accuracy for both complete and draft genomes, facilitating the classification of metagenome-assembled genomes that may lack universal marker genes [21]. The robustness of these genetic discontinuities, manifested with or without the most frequently sequenced species, provides compelling evidence for the existence of clear species boundaries in prokaryotes.

Figure 1: Workflow for Genomic Species Delineation Using Average Nucleotide Identity

Methodological Framework: Experimental Approaches and Protocols

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) Determination Protocol

The ANI method has emerged as a robust standard for species delineation, closely reflecting the traditional concept of DNA-DNA hybridization relatedness while offering portability and reproducibility [21]. The following protocol outlines the key steps for ANI-based species classification:

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Cultivate microbial isolates under appropriate conditions ensuring purity

- Extract high-quality genomic DNA using standardized kits or protocols

- Assess DNA quality and quantity through spectrophotometry and fluorometry

- For draft genomes, proceed with library preparation and sequencing

Genome Sequencing and Assembly

- Perform whole-genome sequencing using Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore platforms

- Ensure sufficient coverage (typically 50-100x) for high-quality assembly

- Assemble reads into contigs using appropriate assemblers (SPAdes, Canu, Flye)

- Assess assembly quality through metrics (N50, completeness, contamination)

FastANI Analysis

- Download and install FastANI from GitHub repository

- Prepare query and reference genomes in FASTA format

- Run FastANI with command:

fastANI -q query_genome.fna -r reference_genome.fna -o output_file - For database comparisons:

fastANI -q query_genome.fna -r genome_directory/ -o output_file - Interpret results: ≥95% ANI indicates species-level relatedness

Validation and Quality Control

- Compare results with alignment-based methods for validation

- Verify anomalous results through genome synteny visualization

- Cross-reference with phenotypic data when available

- For controversial assignments, supplement with phylogenetic analysis of core genes

Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Taxonomy

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Genomic Taxonomy Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | High-quality genomic DNA isolation | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN), Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega) |

| Library Preparation Kits | Sequencing library construction | Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina), SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit (PacBio) |

| Sequence Assemblers | Genome assembly from sequencing reads | SPAdes (Illumina), Canu (PacBio), Flye (Oxford Nanopore) |

| ANI Calculation Tools | Fast genome comparison | FastANI, OrthoANI, PYANI |

| Quality Control Tools | Assessment of genome completeness and contamination | CheckM, BUSCO, QUAST |

| Culture Media Components | Prokaryotic cultivation for DNA isolation | Tryptic Soy Broth, Luria-Bertani Medium, specific selective media |

Integration and Future Directions

Advancing Taxonomy Through Multi-Omic Data Integration

The future of prokaryotic taxonomy lies in the integration of multi-omic data, combining genomic information with transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles to create a comprehensive understanding of microbial diversity and function [22]. The exponential increase in sequenced genomes - with over 1.9 million bacterial genomes now available - provides unprecedented resolution of prokaryotic genetic diversity [22]. This wealth of data enables comparative analyses that reveal evolutionary relationships and functional adaptations across diverse lineages.

Substantial opportunities exist to enhance taxonomic frameworks through improved data standardization and annotation practices [22]. Current challenges include errors in gene annotation, inconsistent metadata collection, and difficulties in cross-platform comparisons [22]. Addressing these limitations through centralized, automated systems for annotation updates and standardized metadata reporting would significantly advance the field. Machine learning and artificial intelligence offer promising approaches for managing the scale and complexity of prokaryotic genomic data, potentially enabling real-time taxonomy updates as new information emerges [22].

Technological Advances and Computational Innovation

The development of novel computational tools has been instrumental in advancing prokaryotic taxonomy. Methods like FastANI have reduced computational barriers to large-scale genomic comparisons, enabling analyses that were previously impractical [21]. These advances are particularly crucial as the number of available genomes continues to grow exponentially, encompassing both cultivated isolates and metagenome-assembled genomes from diverse environments.

Future taxonomic frameworks will likely incorporate functional genomics approaches connecting genotypic diversity to phenotypic traits [22]. Techniques such as RB-TnSeq (randomly barcoded transposon sequencing) and CRISPRi-seq enable high-throughput functional characterization of genes, providing insights into the genetic basis of ecological specialization and adaptation [22]. Integrating these functional data with genomic taxonomy will create a more nuanced understanding of prokaryotic diversity that reflects both evolutionary relationships and ecological roles.

Figure 2: Multi-Dimensional Data Integration for Modern Prokaryotic Taxonomy

The prokaryotic species concept has evolved substantially from its initial reliance on phenotypic observations to contemporary genomic frameworks. The pangenome paradigm, recognizing the fluid nature of prokaryotic genomes with core and accessory components, has transformed our understanding of microbial diversity [20]. Large-scale genomic analyses have demonstrated that despite this fluidity, clear genetic discontinuities exist among prokaryotic populations, supporting the existence of species-like clusters [21]. The development of robust, scalable methods like ANI analysis has provided practical tools for species delineation that reflect both evolutionary relationships and practical taxonomic needs.

Moving forward, the integration of multi-omic data and continued computational innovation will further refine prokaryotic taxonomy [22]. Standardization of data collection, annotation practices, and metadata reporting will enhance the consistency and utility of taxonomic frameworks [22]. These advances will support diverse applications, from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring, by providing a more precise and biologically meaningful classification of prokaryotic diversity. The ongoing synthesis of genomic, functional, and ecological perspectives promises to yield an increasingly comprehensive understanding of prokaryotic species, bridging the gap between operational definitions and biological reality.

The three-domain system represents a fundamental paradigm in modern biological classification, categorizing cellular life into Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya based on evolutionary relationships [23]. This model, introduced by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler, and Mark Wheelis in 1990, was revolutionary because it split the previously unified prokaryotes into two distinct domains, Archaea and Bacteria, by emphasizing major differences in their 16S rRNA genes, membrane lipid structure, and antibiotic sensitivity [23] [24]. The system refuted the long-held concept of a unified prokaryotic kingdom and proposed that these three lineages arose separately from an ancestral organism with poorly developed genetic machinery, often termed the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) [23] [24]. While this hypothesis is considered by some to be obsolete due to more recent findings suggesting eukaryotes arose from a fusion within Archaea, it remains a critical framework for discussing the fundamentals of microbial taxonomy and phylogeny [23].

Comparative Analysis of the Three Domains

The distinction between the three domains is grounded in a suite of molecular, biochemical, and structural characteristics. The following table provides a detailed comparison of their defining features.

Table 1: Defining Characteristics of the Three Domains of Life

| Characteristic | Domain Bacteria | Domain Archaea | Domain Eukarya |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Membrane | Absent (Prokaryotic) | Absent (Prokaryotic) | Present (Eukaryotic) |

| Membrane Lipid Structure | Unbranched chains; Ester linkages | Branched hydrocarbon chains; Ether linkages | Unbranched chains; Ester linkages |

| Cell Wall Composition | Contains peptidoglycan | No peptidoglycan | Variable (e.g., cellulose, chitin) or absent |

| RNA Markers | Distinct bacterial rRNA | Unique archaeal rRNA; more similar to eukaryotes | Distinct eukaryotic rRNA |

| Sensitivity to Antibiotics | Sensitive | Not sensitive | Sensitive |

| Initial Habitat Association | Moderate environments | Extreme environments (e.g., methanogens, halophiles, thermoacidophiles) | Flexible, cooperative colonies |

| Pathogenic Members | Many known pathogens | Few known pathogens | Includes pathogens |

A key piece of evidence supporting this classification comes from comparing the nucleotide sequences of ribosomal RNAs (rRNA), as these molecules are universal and their structure changes very little over time, making them excellent molecular clocks for phylogeny [24]. The three-domain hypothesis posits that Archaea and Eukarya are sister clades, more closely related to each other than to Bacteria [23]. However, a growing body of phylogenomic analyses now suggests that Eukarya may have branched off from within the Archaea, specifically from a group like the Lokiarchaeota, which encodes an expanded repertoire of eukaryotic signature proteins. This has led to the proposal of a competing two-domain system [23].

Experimental Foundations and Key Methodologies

The establishment of the three-domain system was driven by rigorous methodological advances. Below is a detailed protocol for the foundational experiment of rRNA sequencing.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogenetic Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| 16S/18S rRNA Primers | Target conserved regions of rRNA genes for PCR amplification and sequencing. |

| PCR Reagents (Polymerase, dNTPs, Buffers) | Amplify specific rRNA gene fragments from genomic DNA extracts. |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis System | Visualize and verify the size and quantity of amplified PCR products. |

| Sanger Sequencing Kit | Determine the precise nucleotide sequence of the amplified rRNA genes. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Software (e.g., ClustalW, MUSCLE) | Align sequences from different organisms to identify conserved and variable regions. |

| Phylogenetic Tree Construction Software (e.g., PHYLIP, RAxML) | Infer evolutionary relationships and calculate phylogenetic trees from aligned sequences. |

Protocol 1: rRNA Gene Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis This methodology was central to Woese's work and remains a gold standard in microbial phylogenetics [23] [24].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Isolate total genomic DNA from pure cultures of the target bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic cells. Ensure DNA is free of contaminants.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Amplify the 16S rRNA gene (for prokaryotes) or 18S rRNA gene (for eukaryotes) using universal primers that bind to highly conserved regions of the gene.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Confirm the success and specificity of the PCR reaction by running the products on an agarose gel. A single, bright band of the expected size should be visible.

- Sequencing: Purify the PCR product and subject it to Sanger sequencing to determine the exact order of nucleotides.

- Sequence Alignment: Compile the sequences from diverse organisms and use multiple sequence alignment software to line them up, identifying regions of similarity and variation.

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Use computational software to analyze the aligned sequences. The software calculates evolutionary distances and constructs a phylogenetic tree, grouping organisms based on the similarities in their rRNA sequences.

The resulting phylogenetic tree visually represents the evolutionary distances between organisms, providing the quantitative data that underpins the three-domain classification. The stark difference in rRNA sequences between Archaea and Bacteria was the definitive evidence that split the prokaryotes [23].

Visualizing Evolutionary Relationships

The following diagram, created using Graphviz, illustrates the phylogenetic relationships as proposed by the three-domain system and the more recent two-domain system, highlighting the evolutionary position of the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA).

Diagram 1: Competing models of life's evolutionary history.

Data Presentation and Synthesis

The three-domain system organizes the previously established kingdoms into a new, phylogenetically grounded hierarchy. The following table synthesizes this classification and provides representative organisms from each group.

Table 3: Taxonomic Classification within the Three Domains

| Domain | Representative Kingdoms / Groups | Key Examples | Distinctive Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archaea | Methanogens, Halophiles, Thermoacidophiles | Methanobacterium, Halobacterium | Exotic metabolisms; thrive in extreme environments; no known pathogens [23] [24]. |

| Bacteria | Cyanobacteria, Spirochaetota, Actinomycetota | Synechococcus, Treponema pallidum | Include many pathogens; more extensively studied than Archaea [23]. |

| Eukarya | Protista, Fungi, Plantae, Animalia | Amoeba, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Homo sapiens | Cells contain a membrane-bound nucleus; all known non-microscopic organisms [23]. |

The three-domain system has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of life's diversity, providing a robust phylogenetic framework that highlights the profound evolutionary separation between Archaea and Bacteria. Its core principles continue to guide research in microbial taxonomy and evolution. However, the paradigm is dynamic. Genomic evidence increasingly points to a two-domain system, where Eukarya is embedded within the Archaea, suggesting a complex origin involving cellular fusion or endosymbiosis between an archaeal and bacterial species [23]. This ongoing debate underscores that the tree of life is not a static diagram but a hypothesis that is continually tested and refined with new data, driving forward the fundamentals of phylogeny and microbial research.

Genomic Toolkits and Analytical Pipelines: Modern Methods Defining Microbial Classification

The advent of whole-genome sequencing has revolutionized microbial taxonomy, shifting the paradigm from phenotype-based classification to a genome-based phylogenetic framework. Core genomic metrics—Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI), Average Amino acid Identity (AAI), and Genomic GC content—have emerged as the cornerstone for prokaryotic species delineation and phylogeny. These quantitative measures provide a robust, standardized approach to define taxonomic boundaries, refine the tree of life, and uncover true microbial diversity. This in-depth technical guide elucidates the principles, methodologies, and applications of these core metrics, contextualized within the fundamental research on microbial taxonomy and phylogeny. Designed for researchers and scientists, this document provides detailed experimental protocols, data interpretation guidelines, and practical tools to integrate genomic metrics into modern taxonomic workflows.

Microbial systematics is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the accessibility of whole-genome sequencing. Traditional methods reliant on morphological, physiological, and biochemical characteristics are now supplemented and often replaced by genomic analyses that offer unparalleled resolution [25]. This shift enables a taxonomy based firmly on evolutionary relationships, substantially revising the tree of life by conservatively removing polyphyletic groups and normalizing taxonomic ranks based on relative evolutionary divergence [26]. In this genomic framework, Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI), Average Amino acid Identity (AAI), and Genomic GC content have become indispensable tools. They provide the numerical foundation for species definition, genus delimitation, and the exploration of genomic adaptation, thereby forming the essential toolkit for researchers engaged in microbial taxonomy, drug discovery, and biodiversity studies.

Core Genomic Metrics: Definitions and Thresholds

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI)

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) is a computational substitute for wet-lab DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH). It calculates the average nucleotide identity of orthologous genomic sequences shared between two organisms. A key strength is its correlation with traditional DDH, with an ANI of 95-96% corresponding to the standard 70% DDH threshold for species delineation [27] [28]. Methods like KmerFinder, which examines co-occurring k-mers, have demonstrated high accuracy (93-97%) in species identification using whole-genome data [27].

Average Amino acid Identity (AAI)

Average Amino acid Identity (AAI) extends the concept of identity to the protein level. It measures the average identity of amino acids in orthologous protein-coding genes between two organisms. AAI is particularly valuable for delineating genera and higher taxonomic ranks. Similar to ANI, a cutoff of 95% AAI is often used as a boundary for species definition [29]. Furthermore, genomic studies routinely use digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH), with a value below 70% supporting the designation of distinct species [29].

Genomic GC Content

Genomic GC content—the percentage of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) nucleotides in a genome—is a traditional taxonomic character given new context by genomics. While useful, GC content alone is not a definitive metric for species delineation due to its variability. However, significant differences in GC content can support the separation of taxa, and it is a critical factor in understanding genomic adaptation and bias in sequencing techniques [30] [31]. For instance, the Nesterenkonia genus displays a high genomic GC content range of 64–72%, and within it, the polar-adapted NES-AT subclade shows significantly different GC content, indicating adaptation to extreme environments [32].

Table 1: Standard Thresholds for Genomic Species Delineation

| Metric | Species Boundary | Typical Genus-Level Range | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) | 95-96% | ~80-95% | Primary species delineation |

| Average Amino acid Identity (AAI) | 94-95% | ~70-95% | Species & genus delineation |

| digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH) | 70% | <70% | Species delineation (gold standard) |

| 16S rRNA Gene Identity | 98.65-99% | ~94-98% | Preliminary genus/species screening |

| Gene Content Dissimilarity | 0.2 | 0.2-0.4 | Subspecies & strain classification [28] |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

A high-quality genome assembly is the foundational requirement for accurate calculation of genomic metrics.

- DNA Extraction & Library Preparation: Use kits designed for Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., MasterPure Gram Positive DNA Purification Kit) [29]. Assess DNA quality and quantity via Nanodrop spectrophotometry and agarose gel electrophoresis. For library construction, genomic DNA is fragmented (e.g., via Covaris S2 sonication), end-repaired, adenylated, and ligated to sequencing adaptors.

- Sequencing & Assembly: Sequencing is performed on platforms like Illumina NovaSeq or HiSeq X Ten [32] [29]. Adapter sequences and low-quality reads are removed using tools like Trimmomatic [32]. High-quality reads are assembled into scaffolds using assemblers such as SPAdes [32].

- Quality Control & Annotation: Assess assembly completeness and contamination with CheckM [32] [29]. Annotate the assembled genome using pipelines like PROKKA or the RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology) server to identify protein-coding genes, tRNAs, and rRNAs [32] [29].

Figure 1: Workflow for Genome Sequencing and Analysis for Taxonomy.

Calculating Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and Average Amino acid Identity (AAI)

ANI Calculation: ANI is typically calculated using tools such as FastANI [32] or the ANI calculator from the enveomics collection [33]. These tools compare two genome sequences by breaking them into fragments, finding the best matches between them, and calculating the average nucleotide identity of these orthologous regions.

AAI Calculation: AAI is computed using the AAI calculator [33] or the AAI-Matrix tool for all-vs-all comparisons within a dataset [33]. This involves comparing the proteomes (predicted protein sequences) of two organisms. Orthologous proteins are identified, and the average identity of their amino acid sequences is calculated.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Genomic Taxonomy

| Tool Name | Function | Key Feature | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastANI | ANI calculation | Fast, alignment-free; reference-based | https://github.com/ParBLiSS/FastANI |

| Enveomics (ANI/AAI) | ANI/AAI calculator | Distribution of identity; fragment-based | http://enve-omics.ce.gatech.edu/ [33] |

| OrthoFinder | Orthologous groups identification | Infers orthogroups for AAI/phylogeny | https://github.com/davidemms/OrthoFinder |

| CheckM | Genome completeness/contamination | Uses lineage-specific marker genes | https://github.com/Ecogenomics/CheckM |

| KmerFinder | Species identification from WGS | k-mer based; high accuracy | https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/KmerFinder/ |

| MyTaxa | Taxonomy assignment | Handles metagenomic fragments | http://enve-omics.ce.gatech.edu/mytaxa [33] |

Accounting for GC Content and Sequencing Bias

GC content can be calculated from the assembled genome using basic bioinformatics scripts or toolkits like seqkit [32]. However, it is crucial to recognize that GC content bias is a major issue in whole-genome sequencing. Regions with extremely high or low GC content are often underrepresented in sequencing data due to challenges in PCR amplification and sequencing enzyme efficiency [34] [31]. This can lead to gaps in coverage and inaccurate GC content measurement.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Library Preparation: Use PCR-free workflows or polymerases engineered for high GC content to reduce amplification bias [31].

- Bioinformatic Correction: Employ tools like Picard or MultiQC to assess coverage uniformity and GC bias. Bioinformatics normalization algorithms can computationally correct for these biases after sequencing [31].

A Practical Case Study: Genomic Delineation ofSchaaliaSpecies

A recent study on oral Actinomyces provides a exemplary model for the application of these core metrics [29]. Strains NCTC 9931 and C24, previously classified as Actinomyces odontolyticus, were re-evaluated using a genomic approach.

- Genome Features: Both strains had a genome size of ~2.3 Mbp and a GC content of 65.5%.

- Phylogenetic Analysis: A core genome SNPs phylogenetic tree was constructed using the PGAP pangenome pipeline, placing NCTC 9931 and C24 within the genus Schaalia but as distinct from known species.

- Overall Genome Relatedness Index: This was the crucial step for species delineation. The study calculated:

- dDDH: Values below 70% when compared to the nearest type strain (S. odontolytica NCTC 9935^T^).

- ANI and AAI: Values below 95% when compared to S. odontolytica NCTC 9935^T^.

- Taxonomic Proposal: Based on these genomic metrics, strain NCTC 9931 was proposed as the novel species Schaalia dentiphila sp. nov., and the highly similar yet distinct strain C24 was proposed as a novel subspecies, Schaalia dentiphila subsp. denticola subsp. nov.

This case underscores how ANI, AAI, and dDDH provide the quantitative evidence required for robust taxonomic decisions, even for closely related organisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Kits and Reagents for Genomic Taxonomy Workflows

| Reagent / Kit | Function in Workflow | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| MasterPure Gram Positive DNA Purification Kit | High-quality DNA extraction from bacterial cells. | Critical for difficult-to-lyse Gram-positive bacteria [29]. |

| NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries for Illumina platforms. | Standardized protocol for consistent library construction [32]. |

| Covaris S2 Sonication System | Mechanical fragmentation of genomic DNA. | Provides more uniform fragmentation compared to enzymatic methods, reducing bias [31]. |

| Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) & Yeast Extract | Routine cultivation and maintenance of bacterial strains. | BHYE broth (BHI + Yeast Extract) used for growing Schaalia strains anaerobically [29]. |

| PCR Bias-Reduction Kits | Polymerases and kits designed for uniform amplification. | Kits with enzymes engineered to amplify GC-rich templates improve coverage [31]. |

The standardization of microbial taxonomy around genome-based phylogeny has fundamentally revised our understanding of the bacterial tree of life [26]. Within this framework, ANI, AAI, and GC content stand as the core genomic metrics for definitive species delineation and phylogenetic placement. While ANI and dDDH provide the primary species boundary definitions, and AAI helps delineate higher taxa, GC content remains a valuable descriptive and diagnostic character. As sequencing technologies evolve and bioinformatic tools become more sophisticated, the precise and quantitative application of these metrics will continue to be paramount for researchers in microbiology, ecology, and drug development, enabling the discovery and correct classification of the vast, uncharted microbial diversity.

The accurate classification and phylogenetic reconstruction of microorganisms are fundamental to advancing research in microbial ecology, pathogenesis, and drug development. For decades, 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing has served as the cornerstone of microbial taxonomy and phylogeny. However, the limitations of this single-gene approach in discriminating closely related species have prompted the development of more robust methods. Multilocus Sequence Analysis (MLSA) has emerged as a powerful alternative, leveraging the concatenated sequences of multiple housekeeping genes to provide superior phylogenetic resolution [35]. This technical guide examines the enduring role of 16S rRNA sequencing while highlighting the transformative potential of MLSA in modern microbial systematics.

The 16S rRNA Gene: Workhorse of Microbial Identification

Fundamental Principles and Historical Context

The 16S rRNA gene is approximately 1,500 nucleotides long and is an integral component of the 30S small subunit of prokaryotic ribosomes [36]. Its utility as a phylogenetic marker stems from its universal distribution across bacteria and archaea, combined with a mosaic of highly conserved regions alternating with hypervariable regions. The conserved regions facilitate universal primer binding and alignment across diverse taxa, while the variable regions provide species-specific signature sequences that enable differentiation [37]. Carl Woese and George Fox pioneered the use of 16S rRNA for phylogenetic studies in the 1970s, establishing the three-domain system of life (Bacteria, Archaea, and Eucarya) that revolutionized our understanding of evolutionary relationships [36] [37].

Methodological Approach and Protocol

Standard 16S rRNA gene sequencing for phylogenetic analysis involves several critical steps that must be meticulously optimized for reliable results:

- DNA Extraction and Purification: Cell lysis followed by nucleic acid purification to obtain high-quality, inhibitor-free DNA suitable for amplification [36].

- PCR Amplification: Using universal primers targeting conserved regions flanking the V3-V4 hypervariable regions. A typical reaction includes:

- Template DNA: 1-10 ng

- Primers: 0.2-0.5 µM each

- PCR Mix: Standard Taq polymerase, dNTPs, buffer with MgCl₂

- Cycling Conditions: Initial denaturation (95°C for 3 min); 30-35 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 30 s), annealing (55°C for 30 s), extension (72°C for 1 min); final extension (72°C for 5 min) [36]