Microbial Ecology and Environmental Interactions: From Molecular Tools to Drug Discovery

This article synthesizes current advances in microbial ecology to provide a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Microbial Ecology and Environmental Interactions: From Molecular Tools to Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article synthesizes current advances in microbial ecology to provide a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of microbial interactions in diverse environments, from oceans to the human microbiome. The review details cutting-edge methodological approaches, including next-generation sequencing and metabolic modeling, for analyzing complex microbial communities. It further addresses key challenges in data interpretation and optimization, and validates the translational potential of microbial ecology through case studies in drug discovery and clinical applications, highlighting paths for biomedical innovation.

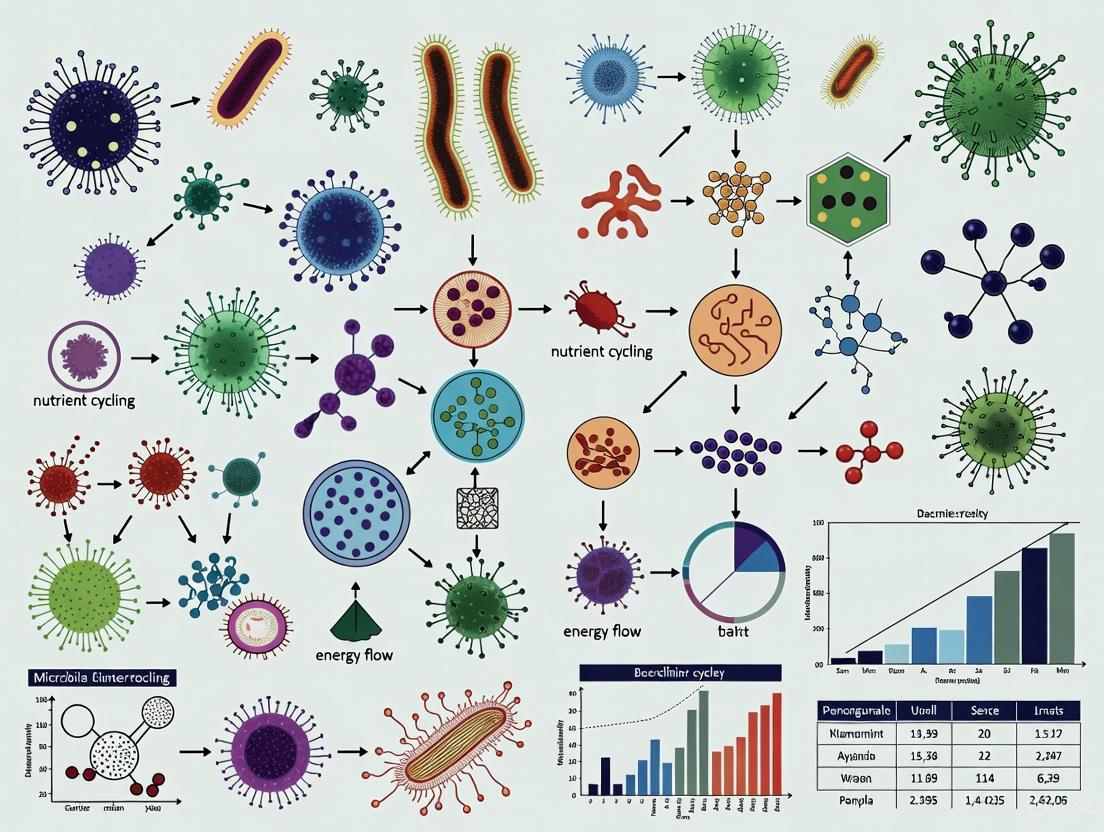

The Unseen World: Foundational Principles of Microbial Interactions and Ecosystem Function

Microbial ecology is the scientific discipline dedicated to the study of the relationships and interactions within microbial communities, as well as their interactions with the surrounding environment and hosts within a defined space [1]. This field moves beyond the study of individual microbial species in isolation to understand the complex, dynamic networks they form in diverse habitats, from the human gut to global ecosystems. These microbial communities, known as microbiomes, are ubiquitous, found on and in people, animals, plants, and throughout the environment [1]. A core tenet of microbial ecology is that the activities of these complex communities are responsible for fundamental biogeochemical transformations in natural, managed, and engineered ecosystems [2]. The structure and function of these communities are governed by a delicate balance of interactions, which can be cooperative, antagonistic, or neutral, ultimately influencing the health of their hosts and the stability of ecosystems.

Core Principles of Microbial Interactions

Microbial interactions form the foundation of community structure and function. These relationships, categorized below, dictate nutrient flow, population dynamics, and overall ecosystem stability.

Table 1: Types of Microbial Interactions in Ecological Communities

| Interaction Type | Description | Ecological Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Symbiosis / Mutualism | Interaction where each species derives a benefit; can be intermittent, permanent, or cyclic [2]. | Enhances nutrient availability and stress resistance for partners; critical for ecosystem function [2]. |

| Antagonism | Characterized by competition, amensalism, and predation [2]. | Shapes community composition by inhibiting or excluding certain species [2]. |

| Competition | Microorganisms vie for the same limited resources, such as nutrients or space [2]. | Leads to the exclusion or suppression of less competitive species. |

| Amensalism | One organism produces substances that inhibit or kill another (e.g., antibiotic production by fungi/bacteria) [2]. | Provides a competitive advantage to the inhibitor. |

| Predation | One microorganism actively consumes another (e.g., bacteriophages infecting bacteria) [2]. | Controls population sizes and drives evolutionary adaptation. |

| Host-Pathogen | How microbes or viruses sustain themselves within host organisms, potentially causing disease [2]. | Impacts host health and fitness; a key focus in medical microbiology. |

These interactions are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously within a community. For instance, the indigenous flora on mucous membranes provides protection against pathogens by competing for space and nutrients and by producing inhibitors, a form of antagonism that benefits the host [2]. Similarly, in soil ecosystems, plant-soil-microbe interactions involve a complex network where plants exude organic compounds through their roots to feed microbes, which in return enhance plant nutrient availability and offer protection from pathogens [2].

Methodologies in Microbial Ecology Research

Understanding microbial community structure and its functional consequences requires a combination of conventional and modern molecular techniques. The workflow typically involves sampling, genetic analysis, and statistical comparison.

Statistical Comparison of 16S rRNA Gene Libraries

A critical methodology for comparing the taxonomic composition of different microbial communities involves the statistical analysis of 16S rRNA gene libraries. The program ∫-LIBSHUFF is used to determine whether differences in library composition are due to sampling artifacts or reflect true underlying differences between the communities from which they were derived [3].

- Objective: To test the null hypothesis that two or more 16S rRNA gene libraries are samples from the same underlying microbial community.

- Principle: The method uses the Cramér-von Mises statistic to compare the coverage curves of the libraries. It measures the number of sequences unique to one library when two libraries are compared across all phylogenetic levels [3].

- Procedure:

- Sequence Alignment and Distance Calculation: Nucleic acid sequences from the different libraries are aligned. The genetic distance between all pairs of sequences is calculated, often using the DNADIST program from the PHYLIP package [3].

- Coverage Calculation: For each library (X), the coverage, CX(D), is calculated as the percentage of sequences in X that are not singletons at a given distance D. The coverage of library X by library Y, CXY(D), is the percentage of sequences in X that have a close relative (within distance D) in library Y [3].

- Test Statistic Calculation: The integral form of the Cramér-von Mises statistic is calculated as the integral of [CX(D) - CXY(D)]² over all possible evolutionary distances D [3].

- Significance Testing via Monte Carlo Randomization: The sequences from all libraries are pooled and randomly reassigned into new libraries of the same sizes as the originals. The test statistic is recalculated for these randomized libraries. This process is repeated many times (e.g., 1,000-10,000) to build a null distribution. The P-value is the proportion of the randomized statistics that are larger than the observed statistic [3].

The following diagram illustrates this statistical workflow:

Quantitative Analysis of Community Function

To quantitatively assess how microbial community composition mediates ecosystem function, researchers employ controlled experiments. A key approach is the sterilized plant litter inoculation experiment [4].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Litter Sterilization: Plant litter is collected and sterilized (e.g., via gamma irradiation or autoclaving) to eliminate its native microbial community.

- Inoculum Preparation: Microbial assemblages are collected from different environmental sources (e.g., different soil types, or different treatment conditions).

- Inoculation and Incubation: The sterilized litter is inoculated with the different microbial assemblages. Control treatments may receive a sterile inoculum.

- Monitoring: The litter is incubated under controlled conditions, and the decay rate is monitored over time by measuring mass loss or CO₂ respiration.

- Analysis: The decay rates between different inoculum treatments are compared. A meta-analysis of such studies has shown that the influence of microbial community composition on litter decay is strong, rivaling the influence of litter chemistry itself [4].

Quantitative Data and Key Findings

Recent research has provided quantitative evidence for the critical role of microbial community structure in driving ecological processes.

Table 2: Quantitative Insights from Microbial Ecology Studies

| Study Focus | Key Quantitative Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Litter Decomposition | The influence of microbial community composition on litter decay is strong, rivaling in magnitude the influence of litter chemistry on decomposition [4]. | Community structure is a primary determinant of carbon cycling rates in soils. |

| Agricultural Productivity | Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and mycorrhizae enhance plant resistance to biotic (diseases) and abiotic (salinity, drought, pollution) stresses [2]. | Microbial management can reduce agricultural losses and improve food security. |

| Antimicrobial Resistance | In 2004, more than 70% of pathogenic bacteria were estimated to be resistant to at least one of the currently available antibiotics [5]. | Highlights the critical need for new antimicrobials and ecological approaches to combat resistance. |

Applications and Research Directions

The principles of microbial ecology are being applied to solve pressing global challenges, particularly in human health and environmental sustainability.

Microbial Ecology in Human Health

The CDC recognizes that treatments focused on microbial ecology and protecting a person's microbiome can protect people from infections [1]. When antibiotics disrupt the microbiome, antimicrobial-resistant pathogens can dominate, increasing the risk of life-threatening infections [1]. Intervention strategies include:

- Pathogen Reduction: A strategy that decreases the number of bacterial or fungal pathogens.

- Decolonization: A type of pathogen reduction that eliminates colonizing pathogens from specific body sites like the skin or nose using topical treatments like chlorhexidine gluconate or nasal mupirocin ointment [1]. Emerging strategies include fecal microbiota transplantation, live biotherapeutic products, and the use of bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) to rebalance microbial communities and combat resistant pathogens [1].

Predicting Microbial Evolutionary Dynamics

Understanding microbial evolution is crucial for anticipating responses to selective pressures like antibiotics and environmental change [6]. Current research topics in this area include:

- Drivers and dynamics of (pan)genome evolution.

- Evolution within complex microbial communities.

- Developing predictive models of microbial evolution for applications in public health and biotechnology [6].

The following diagram conceptualizes the dynamics of microbial community assembly and its functional outcomes:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research in microbial ecology relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials in Microbial Ecology

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| ∫-LIBSHUFF Software | A computer program that uses the Cramér-von Mises statistic to provide rigorous statistical comparison of 16S rRNA gene libraries, determining if communities are significantly different [3]. |

| Chlorhexidine Gluconate (CHG) | A topical antiseptic agent used in pathogen reduction and decolonization strategies, particularly for skin surfaces in healthcare settings to prevent infections [1]. |

| Mupirocin Nasal Ointment | A topical antibiotic used for nasal decolonization of pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus to prevent surgical site infections [1]. |

| Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) | Defined, live microbial products (e.g., Rebyota, VOWST) used to restore a healthy gut microbiome and treat recurrent C. difficile infection, also shown to reduce antimicrobial-resistant pathogens [1]. |

| Sterilized Plant Litter | Serves as a standardized organic substrate in decomposition experiments to isolate and quantify the functional effect of different microbial inocula on carbon cycling [4]. |

Ecological niches, defined by an organism's potential to occupy a particular space and its behavioral adaptations, are fundamental to structuring biological communities [7]. In microbial ecology, these niches are critical in two seemingly disparate yet fundamentally connected realms: the vast, low-oxygen regions of the ocean known as Oxygen Minimum Zones (OMZs) and the intricate host-associated microbial ecosystems. In OMZs, niches are defined by steep physicochemical gradients that create distinct habitats with specific metabolic requirements [8]. In host-associated environments, niches are shaped by host factors through a process termed "host-filtering," which includes physical conditions, nutrient availability, and immune pressures [7]. Understanding the microbial community assembly, adaptation, and function within these niches is essential for comprehending global biogeochemical cycles, host health, and the responses of these systems to environmental change.

The concept of the "metaorganism" – the host and its associated microbiome functioning as a collective unit with shared fitness – provides a unifying framework for studying these systems [9]. In both OMZs and host environments, microorganisms provide essential functions. In OMZs, they mediate crucial biogeochemical processes, including nitrogen cycling and greenhouse gas production [8]. In host systems, they facilitate digestion, nutrient production, and pathogen resistance [9]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on the microbial ecology of these key niches, highlighting methodological approaches, core findings, and future directions for researchers and scientists investigating microbial ecology and environmental interactions.

Oceanic Oxygen Minimum Zones (OMZs): Microbial Hotspots in a Expanding Habitat

OMZ Formation and Global Significance

Oxygen Minimum Zones (OMZs) are extensive oceanic regions where oxygen concentrations are at their minimum in the water column. They occur globally and vary in magnitude from hypoxic (low oxygen) to anoxic (functionally zero oxygen) conditions, as found in the Eastern Tropical North and South Pacific (ETNP and ETSP) and the Arabian Sea [8]. OMZs are formed through a combination of abiotic and biotic factors. Abiotically, they develop in areas with limited ocean ventilation, low lateral transport, and minimal wind-driven circulation, often at midwater depths where oxygen from surface mixing is depleted [8]. Biotically, high surface productivity in regions like upwelling zones leads to substantial export of organic matter to mid-depths, where microbial respiration consumes oxygen [8].

The global significance of OMZs is twofold. First, they are hotspots for microbially driven biogeochemical cycling, accounting for up to 50% of the ocean's nitrogen removal through processes like denitrification and anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) [8]. Second, OMZs have expanded over the past 60 years and are predicted to continue expanding due to climate change. Rising ocean temperatures decrease oxygen solubility and strengthen stratification, reducing oxygen supply to the interior ocean [8]. This expansion has profound implications for marine ecosystems, including altering the biogeographic ranges of marine organisms and creating feedback loops that may further influence climate through the production of greenhouse gases like nitrous oxide [8].

Microbial Community Structure and Function in OMZs

The distinct physicochemical conditions of OMZs structure unique microbial communities dominated by bacteria and archaea specializing in anaerobic metabolisms. The Yongle Blue Hole (YBH) in the South China Sea, the world's deepest underwater cavern at 301 meters, serves as a natural model system for studying OMZ microbial ecology due to its sharply stratified oxic, chemocline, and anoxic zones [10]. A 2025 metagenomic study of the YBH revealed a diverse viral community, with over 70% of 1,730 identified viral operational taxonomic units (vOTUs) affiliated with the classes Caudoviricetes and Megaviricetes, particularly within the families Kyanoviridae, Phycodnaviridae, and Mimiviridae [10]. This viral community exhibited significant niche separation, with the deeper anoxic layers containing a high proportion of novel viral genera not found in the oxic layer or open ocean [10].

The prokaryotic hosts for these viruses predominantly belonged to the phyla Patescibacteria, Desulfobacterota, and Planctomycetota – groups known for their roles in sulfur cycling and anaerobic metabolism [10]. A key finding was the detection of putative auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) in viral genomes, suggesting viruses influence key biogeochemical pathways, including photosynthetic and chemosynthetic processes, as well as methane, nitrogen, and sulfur metabolisms. Particularly high-abundance AMGs were potentially involved in prokaryotic assimilatory sulfur reduction, highlighting a potentially important role for viruses in sulfur cycling in these anoxic environments [10].

Table 1: Key Microbial and Viral Groups in the Yongle Blue Hole OMZ

| Group | Taxonomic Affiliation | Ecological Role/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant Viruses | Classes: Caudoviricetes, MegaviricicetesFamilies: Kyanoviridae, Phycodnaviridae, Mimiviridae | Cell lysis and mortality, horizontal gene transfer, potential influence on host metabolism via AMGs [10] |

| Prokaryotic Hosts | Phyla: Patescibacteria, Desulfobacterota, Planctomycetota | Sulfur cycling, anaerobic metabolism, nitrogen transformation [10] |

| Viral AMGs Identified | Genes linked to sulfur, nitrogen, methane, and carbon cycles | Potential viral reprogramming of host metabolic pathways during infection, particularly assimilatory sulfur reduction [10] |

Host-Associated Microbiomes: Assembly, Dynamics, and Host Interactions

Ecological Theory Applied to Microbiome Assembly

The assembly of host-associated microbiomes is governed by a combination of deterministic and stochastic processes, concepts borrowed from classical macro-ecology [7]. Deterministic processes are directional forces that shape community structure predictably, driven by factors like host selection, environmental conditions, and species interactions. In contrast, stochastic processes are random events like dispersal and ecological drift that create variation in species abundance and presence [7].

Initial colonization is a critical phase where the host environment, initially free of microbes, exerts strong selective pressure. This aligns with the Grinnellian niche concept, where an organism's potential to occupy a space depends on its adaptations [7]. In the human infant gut, for example, initial colonization begins with aerotolerant bacteria like Enterobacteriaceae, reflecting an aerobic environment that subsequently shifts to dominance by anaerobes like Bacteroidaceae as the gut matures [7]. Hosts further refine these physical niches through host-filtering mechanisms, including immune responses like antimicrobial peptide production and physiological factors, leading to phylosymbiosis – where a host's microbial community more closely resembles that of its species than distantly related hosts [7].

Priority Effects and Niche Modification

The concept of priority effects posits that the order and timing of species arrival during community assembly can significantly influence the resulting composition and function [7]. Early colonizers can shape the trajectory of the microbiota through two main mechanisms:

- Niche preemption: Early-arriving species consume available resources, limiting the establishment and success of later-arriving species.

- Niche modification: Early colonizers alter the environment (e.g., by changing pH, oxygen availability, or host immunity), creating new niches that later-arriving species can exploit [7].

The significance of priority effects is evident across host systems. In healthy human infants, microbiome maturation follows a reproducible sequence, and disruptions to this order are linked to disease states [7]. In neonatal chicks, early-colonizing Enterobacteriaceae utilize resources to outcompete pathogenic Salmonella [7]. Furthermore, early colonizers can induce lasting changes in host phenotype, as demonstrated by germ-free animal studies where colonization during critical developmental windows reverses altered immune gene expression and function [7].

The Metaorganism: Joint Adaptation of Host and Microbiome

A central question in microbial ecology is how hosts and their microbiomes jointly contribute to adaptation, particularly in novel or changing environments. Microbiomes may be especially important for rapid adaptation because they can change more quickly through compositional shifts and horizontal gene transfer than host genomes, which have longer generation times [9]. An experimental model system using the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and its microbiome demonstrated this joint adaptation in a novel compost environment [9].

After approximately 30 host generations (100 days) in the compost mesocosms, different replicate lines showed divergent fitness trajectories. A common garden experiment, where final host populations and their associated microbiomes were reassembled in all combinations, revealed that host-microbiome interactions were critical to these fitness outcomes [9]. The adaptation was interdependent: specific changes in the microbiome composition (both bacteria and fungi) and genetic changes in the host nematode (evidenced by altered gene expression) were both associated with the observed fitness changes. This provides direct experimental evidence that adaptation to a novel environment is a joint effort of the host and microbiome – a metaorganism adaptation [9].

Table 2: Experimental Evidence for Metaorganism Adaptation in C. elegans

| Experimental Component | Description | Outcome/Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Model System | Nematode C. elegans with a defined microbial community (CeMbio43) in a novel compost environment [9] | Established a reproducible system for studying host-microbiome evolution |

| Experimental Design | ~30 generations of evolution in compost mesocosms, followed by common garden experiments with cross-inoculation of hosts and microbiomes [9] | Allowed disentanglement of host genetic and microbiome contributions to fitness |

| Key Results | 1. Divergent fitness trajectories in different mesocosm lines.2. Interaction between host and microbiome was key to fitness outcome.3. Associated changes in microbiome composition and host transcriptome [9] | Demonstrated that adaptation is jointly influenced by host and microbiome, forming a co-adapted metaorganism |

Methodologies for Investigating Microbial Niches

Metagenomic and Viromic Approaches

Cut-edge molecular techniques are essential for unraveling the complexity of microbial communities in their niches. The study of the Yongle Blue Hole exemplifies a comprehensive metagenomic and viromic approach [10]. The methodology involved collecting seawater samples from different depths (oxic and anoxic zones) and processing them to obtain both a "cellular fraction" (>0.22 μm) and a "viral fraction" (<0.22 μm, concentrated via iron chloride flocculation) [10]. Metagenomic DNA was extracted from both fractions and sequenced on an Illumina platform.

Diagram: Metagenomic Workflow for Viral and Microbial Analysis

Bioinformatic processing is crucial. After assembly, viral contigs were identified using a multi-tool approach (VirSorter2, VIBRANT, DeepVirFinder) to ensure high confidence [10]. Identified viral contigs were then processed with CheckV to remove host-derived regions from integrated proviruses, and high-quality contigs were clustered into viral operational taxonomic units (vOTUs) at the species level [10]. This rigorous pipeline allows for the comprehensive characterization of both viral and microbial components of an ecosystem.

Common Garden Experiments for Disentangling Host and Microbiome Effects

To experimentally determine the relative contributions of host evolution and microbiome changes to metaorganism adaptation, common garden experiments are powerful tools. The C. elegans compost study provides a clear protocol [9]. After a period of experimental evolution in a novel environment, nematode populations and their associated microbial communities are harvested. These are then cross-inoculated in a common garden setting – for instance, the original host population is paired with the evolved microbiome, and the evolved host population is paired with the original microbiome [9].

The fitness of these reassembled metaorganisms is then measured using relevant proxies. In the case of C. elegans, population growth rate is a key fitness trait, as rapid expansion is crucial in its short-lived habitats [9]. Body size, which correlates with fecundity, can serve as an additional proxy [9]. By comparing the fitness outcomes across the different host-microbiome combinations, researchers can attribute adaptation to changes in the host, changes in the microbiome, or, crucially, to an interaction between the two.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CeMbio43 Bacterial Community | A defined set of 43 bacterial strains representative of the native C. elegans microbiome [9] | Serves as a standardized, synthetic starting microbiome for experimental evolution studies in nematodes [9] |

| Iron Chloride (FeCl₃) | A flocculating agent used to concentrate viral particles from large volumes of water [10] | Enables virome collection from aquatic environments (e.g., seawater from OMZs) for subsequent metagenomic sequencing [10] |

| Polycarbonate Membrane Filter (0.22µm) | Used to separate microbial cells (retained on filter) from free-living viruses (in filtrate) [10] | Collection of the "cellular fraction" and "viral fraction" for parallel metagenomic analysis of both communities [10] |

| VirSorter2, VIBRANT, DeepVirFinder | Bioinformatics tools for identifying viral sequences from metagenomic assemblies [10] | High-confidence identification of viral contigs in complex environmental samples through a consensus approach [10] |

The study of key ecological niches, from OMZs to host-associated microbiomes, reveals common principles of microbial community assembly and function. In both systems, environmental conditions – whether abiotic factors like oxygen concentration or host-derived factors like immune pressure – create distinct niches that filter for specially adapted microorganisms. Furthermore, interactions, including virus-host dynamics and priority effects among microbes, play a pivotal role in shaping these communities and their metabolic outputs.

A critical insight from recent research is the concept of the metaorganism as a unit of adaptation. The experimental evidence from model systems shows that hosts and microbiomes can co-adapt to novel environments, with both partners contributing to improved fitness [9]. This has profound implications for understanding how complex organisms will respond to environmental change, including climate change and habitat alteration.

Future research should focus on:

- Integrating Multi-Omics Data: Combining metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metabolomics, and host genomics to build a mechanistic picture of metaorganism function.

- Linking Laboratory and Field Studies: Validating findings from controlled model systems with observations in natural environments, such as the Yongle Blue Hole [10].

- Understanding Climate Change Impacts: Systematically investigating how deoxygenation, warming, and acidification will alter microbial community structure and function in OMZs and host ecosystems [8].

- Translating Ecological Theory: Further adapting and applying macro-ecological theories to predict the dynamics and stability of microbial communities across different niches [7].

By deepening our understanding of these fundamental ecological niches, researchers can better predict ecosystem responses to global change, harness microbiomes for therapeutic interventions, and elucidate the rules of life that govern complex biological systems from the global ocean to within our own bodies.

Chemical ecology explores the complex roles of natural chemicals that mediate interactions within and between species, influencing ecosystem structure and function. This whitepaper examines the core signaling compounds—allelochemicals, infochemicals, and defense metabolites—that constitute this chemical language, with particular focus on their mechanisms within microbial ecology and environmental interactions. These specialized metabolites regulate critical biological processes including competition, predation, symbiosis, and defense across terrestrial and aquatic systems. Recent advances in analytical techniques and molecular biology have unveiled sophisticated communication networks with significant implications for pharmaceutical discovery, sustainable agriculture, and ecosystem conservation. This technical guide synthesizes current research on the biosynthesis, function, and ecological significance of these compounds, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding and manipulating chemical signaling in natural systems.

Chemical ecology represents the scientific discipline dedicated to understanding the chemical basis of organismal interactions and the ecological consequences of these exchanges [11]. Organisms produce and release a diverse array of specialized metabolites that serve as molecular messages in their environment, facilitating communication, defense, and resource competition [12]. These interactions occur across the biological spectrum, from microorganisms to higher plants and animals, creating a complex web of chemical dependencies and responses.

The field intersects multiple disciplines including organic chemistry, molecular biology, ecology, and evolutionary biology. Three principal classes of compounds form the core vocabulary of this chemical language: allelochemicals, which influence interactions between different species; infochemicals, which convey information between organisms; and defense metabolites, which protect against predators, pathogens, and competitors [11] [13]. In marine and terrestrial environments, these compounds structure populations, communities, and entire ecosystems by determining survival, reproduction, and distribution patterns [11].

Within microbial ecology, chemical signaling governs population dynamics, biofilm formation, virulence, and symbiotic relationships. Microbes both produce and respond to these chemical cues, creating intricate feedback loops that influence ecosystem stability and function [2]. The study of these interactions provides not only fundamental insights into ecological processes but also practical applications in drug discovery, agricultural management, and environmental conservation [11].

Allelochemicals: Chemical Mediators in Interspecific Interactions

Definition and Ecological Significance

Allelochemicals are bioactive chemicals released from donor organisms into the environment that affect the growth, development, survival, and distribution of receiver organisms [12]. The term "allelopathy" originates from the Greek words allelon (of each other) and pathos (to suffer), describing the biochemical interactions between all types of plants, microorganisms, and other organisms [14]. These compounds represent a subset of secondary metabolites that have evolved specifically for ecological functions, primarily as agents of interference competition.

These chemical mediators are released through various pathways including volatile emissions, root exudates, leaf leachates, and decomposition of plant residues [12]. Their effects are typically concentration-dependent, exhibiting hormesis—where low concentrations may stimulate biological processes while higher concentrations inhibit them [15]. This biphasic response adds complexity to understanding their ecological impacts, as the same compound can function differently depending on environmental context and concentration.

Major Classes and Functions

Allelochemicals are categorized based on their chemical structures and biosynthesis pathways, with major classes outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Major Classes of Allelochemicals and Their Functions

| Class | Chemical Characteristics | Producer Organisms | Ecological Functions | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Compounds | Contain benzene ring; widely distributed | Cereals, sunflower, trees | Inhibit seed germination, root growth, nutrient uptake | p-hydroxybenzoic acid, syringic acid, caffeic acid [14] |

| Terpenoids | Derived from isoprene units; >22,000 known structures | Conifers, aromatic plants, cereals | Antimicrobial, herbivore deterrent, soil ecosystem modulation | Momilactones, oryzalexins [16] [17] |

| Alkaloids | Nitrogen-containing compounds; basic properties | Various medicinal plants, crops | Defense against herbivores, antimicrobial activity | Macckian, pisatin [14] [12] |

| Glucosinolates | Sulfur- and nitrogen-containing glycosides | Brassica species | Form bioactive isothiocyanates upon hydrolysis | Benzyl isothiocyanate, allyl isothiocyanate [14] |

| Benzoxazinoids | Cyclic hydroxamic acids | Rye, wheat, maize | Activated after hydrolysis; broad-spectrum activity | DIBOA, DIMBOA, MBOA [14] [12] |

| Coumarins | Benzene-α-pyrone structure | Umbelliferae, Rutaceae, Leguminosae | Inhibit seed germination and lateral root development | Scopoletin, fraxetin [15] |

These compounds employ diverse physiological mechanisms to exert their effects. Phenolic acids interfere with membrane permeability and nutrient uptake, while terpenoids often disrupt mitochondrial functions and hormone regulation [14]. Glucosinolates and their breakdown products can inhibit key enzymes and impair thyroid function in animals, providing defense against herbivory [14]. The structural diversity of allelochemicals reflects the evolutionary arms race between organisms competing for limited resources.

Molecular Mechanisms and Microbial Interactions

At the molecular level, allelochemicals exert their effects through multiple mechanisms. They can inhibit enzyme function, disrupt membrane integrity, interfere with hormone regulation, and generate reactive oxygen species [14] [15]. For instance, coumarin inhibits root growth by interfering with auxin transport and reactive oxygen species homeostasis, while DADS (diallyl disulfide) from garlic influences cucumber root development by regulating hormone levels and modulating cell cycling [15].

Allelochemicals significantly influence soil microbial communities, which in turn modify the compounds' availability and activity [14]. Soil microbes can detoxify allelochemicals, activate prodrug forms, or convert them into more potent derivatives. This complex interplay creates a dynamic rhizosphere environment where the final allelopathic effect depends on both the producing plant and the microbial consortium present. Some allelochemicals also function as molecular signals in plant-microbe interactions, influencing symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi and nitrogen-fixing bacteria [12].

Infochemicals: Chemical Messaging Systems

Conceptual Framework

Infochemicals represent a broader category of chemicals that convey information between organisms, evoking behavioral or physiological responses [13]. The term encompasses allelochemicals but extends to all information-carrying chemicals regardless of their ecological function. These semiochemicals (from the Greek semeion, meaning signal) are classified based on the relationship between emitter and receiver:

- Allomones: Benefit the emitter (e.g., repellents)

- Kairomones: Benefit the receiver (e.g., prey location cues)

- Synomones: Benefit both emitter and receiver (e.g., plant volatiles that attract predator of herbivores)

- Apneumones: Originate from non-living material [13] [12]

Infochemicals operate at extremely low concentrations, typically in the nanomolar to micromolar range, and exhibit high specificity in their actions [13]. Their perception involves sophisticated biochemical reception systems that have evolved to detect these subtle chemical cues amidst environmental noise.

The Infochemical Effect in Ecotoxicology

A significant advancement in chemical ecology has been the recognition of the infochemical effect—the disruption of natural chemical communication by anthropogenic contaminants [13] [18]. Environmental pollutants, including synthetic fragrances and other organic compounds, can interfere with chemical signaling at multiple levels:

- Competitive binding to olfactory receptors

- Desensitization of chemosensory tissues

- Alteration of signal transduction pathways

- Masking of natural infochemicals through background contamination

This interference can produce cascading ecological consequences, as inappropriate responses to chemical cues may reduce foraging efficiency, impair predator avoidance, disrupt mating behaviors, and ultimately decrease population viability [13]. The infochemical effect represents a subtle but potentially widespread impact of chemical pollution that standard ecotoxicological tests often overlook.

Defense Metabolites: Chemical Protection Systems

Secondary Metabolites as Defense Compounds

Defense metabolites constitute a functional category of specialized compounds that protect organisms against biotic and abiotic stresses. These secondary metabolites differ from primary metabolites in that they are not essential for basic metabolic processes but confer ecological advantages [16] [17]. Plants produce over 100,000 such compounds through various biosynthetic pathways, with major classes including terpenes, phenolics, alkaloids, and glucosinolates [16].

These defense compounds have evolved in response to selective pressures from herbivores, pathogens, and environmental stresses. Their production involves significant metabolic costs, which are offset by the survival benefits they provide. Defense metabolites often occur as inactive precursors that are activated upon tissue damage, or are sequestered in specialized structures to prevent autotoxicity [16].

Biosynthetic Pathways and Regulation

The production of defense metabolites is governed by sophisticated biosynthetic pathways and regulatory networks, as illustrated below:

Diagram: Defense metabolite biosynthesis involves complex signaling networks that activate transcription factors regulating specialized metabolic pathways. These pathways draw precursors from primary metabolism to produce diverse compound classes with ecological functions.

Key signaling molecules that regulate defense metabolite production include nitric oxide (NO), hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), methyl jasmonate (MeJA), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), ethylene (ETH), melatonin (MT), and calcium (Ca²⁺) [16] [17]. These signaling molecules activate transcription factors such as WRKY, MYC, and MYB, which in turn regulate the expression of genes encoding biosynthetic enzymes [16].

Stress-Induced Metabolic Changes

Defense metabolite production is frequently induced by environmental stresses, creating a dynamic response system that minimizes metabolic costs while providing protection when needed. Abiotic stresses including drought, salinity, heavy metals, and temperature extremes trigger specific metabolic adjustments through defined signaling cascades [16] [19]. For instance:

- Terpenoid biosynthesis increases under high temperature and oxidative stress, with isoprene serving to stabilize thylakoid membranes and quench reactive oxygen species [16].

- Phenolic and flavonoid accumulation rises under various stress conditions, providing antioxidant protection through free radical scavenging [16].

- Glucosinolate profiles shift in response to herbivory, pathogen attack, and nutrient deficiency, enhancing specific defense responses [14].

This inducibility allows plants to allocate resources efficiently while maintaining readiness for potential threats, representing an evolutionary optimization of defense strategies.

Experimental Methodologies in Chemical Ecology Research

Standard Bioassay Protocols

Research in chemical ecology relies on standardized bioassays to identify and characterize bioactive compounds. Table 2 summarizes key experimental approaches for studying allelochemicals and infochemicals.

Table 2: Standard Experimental Protocols in Chemical Ecology Research

| Assay Type | Experimental Setup | Key Parameters Measured | Applications | Limitations/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed Germination Bioassay | Petri dishes with filter paper moistened with test solution; controlled conditions | Germination percentage, germination rate, radicle length | Initial screening for phytotoxic effects | May not reflect field conditions; soil interactions absent [14] |

| Plant Growth Bioassay | Hydroponic or sand culture with treatment solutions; growth chamber settings | Root/shoot length, fresh/dry weight, chlorophyll content, nutrient uptake | Dose-response studies, mode of action analysis | Requires careful control of environmental variables [14] [15] |

| Soil-Based Bioassay | Pot experiments with natural or artificial soil; field microcosms | Emergence rate, seedling vigor, biomass accumulation, soil microbial analysis | Ecologically relevant assessment | Soil properties significantly influence results [14] |

| Microbial Community Analysis | Culture-based and molecular techniques (DNA sequencing, metagenomics) | Microbial diversity, population dynamics, functional gene expression | Understanding microbial role in allelopathy | Complex data interpretation; correlation vs. causation [2] [14] |

| Volatile Collection & Analysis | Headspace sampling with adsorption traps; GC-MS analysis | Compound identification, quantification, emission dynamics | Study of volatile infochemicals | Technical challenges in collection and quantification [11] |

Analytical Techniques for Compound Identification

Advanced analytical methods are essential for characterizing chemical signals in complex environmental samples:

- Extraction and Purification: Sequential extraction with solvents of increasing polarity; chromatographic techniques (HPLC, CC, TLC) for fractionation [14].

- Structure Elucidation: Mass spectrometry (MS) coupled with gas or liquid chromatography (GC-MS, LC-MS); nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [11] [14].

- Localization and Visualization: Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI); fluorescent tagging; histochemical techniques [11].

- Metabolomic Profiling: High-resolution MS with multivariate statistical analysis to identify biomarker metabolites [16].

These techniques enable researchers to move from biological activity to chemical identity, a crucial step in understanding the molecular basis of ecological interactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Chemical Ecology

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Allelochemical Standards | Juglone, DIMBOA, sorgoleone, caffeic acid | Bioassay positive controls; quantification standards; structure-activity relationship studies | Commercially available or purified from natural sources [14] [15] |

| Signaling Molecule Modulators | Sodium nitroprusside (NO donor), NaHS (H₂S donor), MeJA, ethylene inhibitors | Elucidating signaling pathways; manipulating defense responses | Concentration and timing critical for specific effects [16] [17] |

| Metabolic Pathway Inhibitors | Fosmidomycin (MEP pathway), mevinolin (MVA pathway), PAL inhibitors | Determining biosynthetic routes; functional characterization of pathways | Specificity varies; multiple inhibitors recommended [16] |

| Soil Modification Agents | Activated charcoal, ion-exchange resins, microbial inhibitors | Distinguishing direct vs. indirect effects; modifying rhizosphere chemistry | Charcoal non-specific; resins more selective [14] |

| Molecular Biology Kits | RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, qPCR reagents | Gene expression analysis of biosynthetic pathways | Requires tissue-specific sampling [14] [16] |

Applications and Future Directions

Pharmaceutical Discovery

Marine and terrestrial chemical ecology research has significantly impacted drug discovery, with numerous allelochemicals and defense metabolites serving as lead compounds for pharmaceutical development [11]. Ecological function often predicts biological activity against human pathogens and disease targets. For instance, compounds evolved to deter fungal pathogens may show activity against human fungal infections, while those developed against herbivores may reveal novel mechanisms for cancer treatment [11].

Chemical ecology-driven approaches including activated defense, organismal interaction studies, spatio-temporal variation analyses, and phylogeny-based approaches have enhanced the discovery of novel therapeutic agents [11]. Mapping surface metabolites and understanding metabolite translocation within marine holobionts provides additional strategies for identifying valuable compounds [11].

Sustainable Agriculture

Allelochemicals and related compounds offer environmentally friendly alternatives to synthetic agrochemicals [14] [15]. Applications include:

- Cover cropping with allelopathic species for weed suppression

- Intercropping systems that leverage natural chemical interactions

- Bioherbicides and biopesticides based on plant-derived compounds

- Crop rotation strategies that utilize allelopathic residues to manage soil pathogens

The hormetic effects of many allelochemicals—where low concentrations stimulate growth—further enable their development as natural plant growth regulators [15]. However, challenges remain in standardization, formulation, and field application under varying environmental conditions.

Climate Change Implications

Climate change factors including elevated CO₂, temperature increases, and altered precipitation patterns significantly influence the production, functionality, and perception of chemical signals [11]. These changes may disrupt established ecological relationships and community structures, with potential consequences for ecosystem stability and function. Understanding how chemical communication responds to environmental change represents a critical research frontier with implications for conservation and ecosystem management.

Future research directions include developing high-throughput bioassay systems, integrating multi-omics approaches, establishing ecological relevance in laboratory studies, and exploring the evolutionary dynamics of chemical signaling systems. As analytical capabilities continue to advance and ecological understanding deepens, chemical ecology promises continued insights into the fundamental processes shaping biological systems, with valuable applications across multiple sectors.

Microbial interactions are the fundamental architects of ecosystem functioning, health, and stability. These relationships—ranging from synergistic cooperation to intense rivalry—govern community assembly, drive biogeochemical cycles, and shape the metabolic networks that sustain life [20]. For researchers and drug development professionals, deciphering these interactions is paramount, not only for understanding natural systems but also for manipulating microbiomes for therapeutic and biotechnological ends. A core challenge in microbial ecology has been determining whether competitive or cooperative interactions are more prevalent. Emerging evidence from high-throughput computational studies reveals that this binary question may be outdated; the majority of microbial pairs can exhibit both competition and cooperation, with the outcome being exquisitely dependent on environmental context [21]. This plasticity underscores the complexity of predicting microbial community behavior and highlights the need for sophisticated models that integrate ecological and evolutionary dynamics. This guide provides a technical framework for dissecting these interactions, offering current methodologies, quantitative data, and visual tools to advance research in this rapidly evolving field.

Defining Core Interaction Types

Microbial interactions are traditionally classified based on the fitness effect each partner has on the other. Table 1 summarizes these core types, their mechanisms, and ecological impacts.

Table 1: Core Types of Microbial Interactions

| Interaction Type | Effect on Partner A | Effect on Partner B | Key Mechanism(s) | Ecological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | + (Beneficial) | + (Beneficial) | Cross-feeding of metabolites, co-metabolism, syntrophy, provision of protective environments [20]. | Enhanced ecosystem productivity, stability, and nutrient cycling [22]. |

| Competition | - (Detrimental) | - (Detrimental) | Exploitative competition for limited resources (e.g., nutrients, space); Interference competition via secretion of inhibitory compounds [20]. | Competitive exclusion or niche partitioning, shaping community structure [21]. |

| Amensalism | 0 (Neutral) | - (Detrimental) | Chemical warfare (e.g., antibiotic production) or environmental modification that incidentally harms another organism [20]. | Suppression of susceptible species, potentially freeing resources for others. |

| Predation | + (Beneficial) | - (Detrimental) | Active hunting, engulfment, and digestion of prey organism (e.g., protists consuming bacteria) [23]. | Top-down control of population densities, influencing community composition and evolution. |

| Commensalism | + (Beneficial) | 0 (Neutral) | One organism utilizes waste products or modified environments created by another without affecting it [20]. | Expansion of metabolic niches and community diversity. |

| Neutralism | 0 (Neutral) | 0 (Neutral) | Co-existence without measurable interaction. | Theoretical; rarely observed in resource-limited natural environments. |

The direction and strength of these interactions are not fixed but are highly plastic. A seminal study modeling 10,000 pairs of bacteria across thousands of environments found that most pairs were capable of both competitive and cooperative interactions depending on the availability of environmental resources [21]. This environmental plasticity is a critical consideration for any experimental design or interpretation.

Quantitative Frameworks and Experimental Data

Plasticity of Interactions Across Environments

Large-scale computational simulations using genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) like AGORA and CarveMe have quantified the context-dependency of microbial interactions. The following table synthesizes key findings from an analysis of 10,000 bacterial pairs:

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Interaction Plasticity from Metabolic Modeling [21]

| Parameter | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of Neutralism | 49% (AGORA) to 59% (CarveMe) in default "joint" environments. | Highlights the potential for coexistence without strong, direct pairwise interactions in permissive conditions. |

| Prevalence of Cooperation | 2% (AGORA) to 0% (CarveMe) in default environments. | Suggests obligate mutualism is rare in standard conditions but can emerge under stress. |

| Environmental Switching | On average, removal of at least one environmental compound could switch an interaction from competition to facultative cooperation, or vice versa. | Demonstrates high environmental sensitivity and the potential for rapid community state changes. |

| Resource Availability | Cooperative interactions, especially obligate ones, were most common in less diverse (resource-poor) environments. | Challenges the assumption that cooperation is a luxury of abundant environments; suggests it is a strategy for survival in scarcity. |

| Interaction Robustness | As compounds were removed, interactions tended to degrade towards obligacy, where species become dependent on each other. | Environmental degradation can force interdependent relationships, reducing community resilience. |

Eco-evolutionary Dynamics in pH-Modified Interactions

Theoretical models demonstrate how ecological interactions and evolutionary adaptations are intertwined. In a model system where one bacterial species increases environmental pH (alkaline-producing) and another decreases it (acid-producing), the evolutionary changes in pH preference ("pH niche") fundamentally alter ecological outcomes [24].

Table 3: Outcomes of Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics in a pH-Modification Model [24]

| Initial Physiological Optima | Evolutionary Outcome | Ecological Outcome | System Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|

| p̄₁ > p̄₂ (Acid-producer prefers higher pH than Alkaline-producer) | Traits converge; each evolves to prefer the pH environment created by the other species (p₁* > 0 > p₂*). | Uniquely stable coexistence at an intermediate pH. Both species maintain high population sizes. | High and stable resilience. |

| p̄₁ < p̄₂ (Acid-producer prefers lower pH than Alkaline-producer) | Traits diverge; each evolves to prefer the pH environment created by its own products (p₁* < p₂*). | Bistable coexistence: system converges to either an acidophilic or alkaliphilic equilibrium, depending on initial conditions. | Asymmetrical and generally low resilience. |

This framework shows that ecological theory alone may inaccurately predict outcomes unless it accounts for the capacity of microbes to adaptively evolve their niche preferences in response to interaction-driven environmental changes [24].

Experimental Protocols for Deciphering Interactions

Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling (GSMM) for Predicting Interactions

Objective: To computationally predict the metabolic basis of pairwise microbial interactions (e.g., cross-feeding, competition) under defined environmental conditions.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Protocol:

- Model Acquisition & Curation: Obtain high-quality, genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) for the target microorganisms from curated databases such as AGORA (for human-associated bacteria) or CarveMe (for broader taxa) [21]. Standardize models to ensure consistency in reaction and metabolite annotation.

- Define the Joint Environment: Construct a simulated in silico environment that contains all essential compounds required for the growth of both organisms. This often involves combining the default environments of the two individual models [21].

- Simulate Growth: Use constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods, such as Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), to simulate the growth of each organism in isolation and as a co-culture within the joint environment. Algorithms like SteadyCom can be used for robust community simulation [25].

- Classify Interaction:

- Cooperation/Mutualism: Growth rates of both organisms are higher in the co-culture than in isolation.

- Competition: The growth rate of at least one organism is lower in the co-culture.

- Commensalism: One organism benefits while the other is unaffected.

- Neutralism: No change in growth rates for either organism [21].

- Identify Key Metabolites: Analyze the flux of metabolites through the simulated community. Metabolites secreted by one organism and consumed by the other indicate potential cross-feeding. Overlap in nutrient uptake profiles indicates potential competition [25].

- Experimental Validation: Validate computational predictions using controlled co-culture experiments in chemostats or batch cultures, measuring actual growth yields and metabolite concentrations via mass spectrometry or other analytical techniques [25].

Validating Predator-Prey Interactions via Trait-Based Network Analysis

Objective: To move beyond correlation in co-occurrence networks and experimentally confirm putative predator-prey interactions.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Protocol:

- Community Profiling: Perform cross-kingdom, high-throughput amplicon sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA for bacteria, 18S rRNA for protists, or specific markers for algal groups) on environmental samples (e.g., soil, water, host-associated) [23].

- Network Construction: Use statistical tools like FlashWeave or SpiecEasi to infer a co-occurrence network. Nodes represent microbial taxa, and edges represent significant positive or negative correlations in abundance across samples [23].

- Trait-Based Filtering: Apply ecological trait data to filter the list of putative interactions. For example, when investigating cercozoan predators, filter the network to only include correlations between cercozoans and known suitable prey (e.g., green algae, ochrophytes), dramatically increasing the predictive confidence from ~5% to over 80% [23].

- Food Range Experiments:

- Isolation: Establish axenic cultures of the putative predator and prey from the same environment.

- Co-culturing: Inoculate the predator with a single putative prey type in a controlled medium.

- Monitoring: Track the population dynamics of both organisms over time using cell counting (microscopy, flow cytometry) or qPCR. A successful predation event is indicated by the decline of the prey population concurrent with an increase in the predator population [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Microbial Interaction Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Foundational in silico frameworks (e.g., from AGORA or CarveMe databases) for predicting metabolic interactions and growth capabilities [21]. |

| Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) Toolbox | A MATLAB/SciPy software suite for simulating metabolism and predicting interactions using GEMs via methods like Flux Balance Analysis [25]. |

| Synthetic Media for Co-culture | Defined growth media (e.g., lignin-MB medium, M9 minimal medium) essential for controlling nutrient availability and tracing metabolite exchanges in experimental validation [25]. |

| Cross-Kingdom Sequencing Primers | Specialized primer sets for amplifying taxonomic markers from different microbial kingdoms (e.g., bacteria, protists, fungi) from the same sample for network construction [23]. |

| Axenic Microbial Cultures | Purified and isolated cultures of individual microbial species, serving as the fundamental building blocks for constructing synthetic communities and validating interactions [23]. |

The study of microbial interactions has progressed from simple, static classifications to a dynamic field that embraces environmental plasticity and eco-evolutionary feedbacks. The integration of computational modeling, network analysis, and rigorous experimental validation provides a powerful, multi-faceted approach to dissecting the complex relationships that underpin microbial communities. For researchers in drug development, these tools are indispensable for understanding how microbiomes respond to perturbations, including antibiotic treatments, and for designing effective probiotic or live biotherapeutic consortia. As we continue to refine these methodologies and integrate multi-omics data, our ability to predict, manipulate, and harness the power of microbial interactions for human and environmental health will be fundamentally transformed.

Nitrite (NO₂⁻) is a crucial intermediate in the marine nitrogen cycle, and its accumulation in oceanic oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) represents a significant decoupling of nitrogen transformation pathways. This phenomenon has long served as a diagnostic feature of functionally anoxic marine waters, yet the underlying mechanisms have remained elusive. Traditional explanations suggested that nitrite accumulation resulted simply from a lack of nitrite consumers, but emerging research reveals a more complex story driven by dynamic microbial interactions and competition. Understanding these processes is critical for accurately assessing the global nitrogen budget and predicting its future changes in response to ocean deoxygenation.

This case study examines the paradoxical finding that nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB), despite being nitrite consumers, actively contribute to nitrite accumulation through complex interactions with other microorganisms, primarily denitrifiers [26] [27]. The research synthesizes findings from both environmental systems and engineered bioreactors to elucidate the universal principles governing these microbial community dynamics. By integrating evidence from mechanistic ecosystem modeling, three-dimensional ocean simulations, and experimental wastewater treatment studies, this analysis provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how competition between aerobic and anaerobic microbes shapes nitrogen cycling in anoxic environments.

Core Mechanism: Microbial Interactions Driving Nitrite Accumulation

The Paradox of Nitrite-Oxidizing Bacteria

The conventional understanding of nitrite accumulation in anoxic waters attributed the phenomenon primarily to the suppression of nitrite-reducing microorganisms due to organic matter limitation [27]. However, recent research reveals a counterintuitive mechanism: nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB) actually contribute to nitrite accumulation through their competitive interactions with other microbes [26] [27]. This discovery fundamentally shifts our perspective on nitrogen cycling in oxygen-deficient environments.

The mechanistic explanation lies in the microbial community's response to pulses of organic matter over time. When organic substrates are supplied to anoxic waters, nitrate-reducing denitrifiers initially bloom because their substrate (nitrate) is abundant in deep ocean waters [27]. This bloom produces nitrite as a metabolic byproduct. NOB, which possess higher affinity for nitrite than nitrite-reducing denitrifiers, initially outcompete these organisms for the available nitrite, particularly when trace oxygen is present [27]. This early competitive exclusion prevents nitrite-reducing denitrifiers from building substantial biomass. As NOB grow, they consume the available oxygen, which eventually limits their own growth. With NOB oxygen-limited and nitrite-reducers suppressed, the continued activity of nitrate-reducers leads to significant nitrite accumulation [27].

Ecological and Environmental Dynamics

This accumulation mechanism manifests through what researchers term "ecological accumulation" - nitrite concentrations reaching levels well above the resource subsistence concentrations (R) that limit microbial growth [27]. In practical terms, this means nitrite accumulates to concentrations (~2 μM) approximately one order of magnitude higher than the highest R of all nitrite-consuming populations (0.21 μM) [27]. The resulting nitrite shows high temporal variability due to dynamic microbial interactions driven by the time-varying nature of organic matter pulses [27].

The presence and activity of NOB in ostensibly anoxic zones is sustained by oxygen intrusions into OMZ layers [27]. Genomic studies have revealed substantial metabolic flexibility in NOB, enabling them to capitalize on periodic oxygen availability [26]. This adaptability allows NOB to maintain populations in these environments and play their unexpected role in nitrite accumulation. The dynamic nature of this process is further amplified by mesoscale eddies and submesoscale fronts that create heterogeneity in the vertical supply of organic substrates from surface productivity, leading to variations in the intensity and frequency of organic matter pulses to anoxic zones [27].

Quantitative Evidence and Experimental Data

Nitrogen Transformation Metrics in Environmental and Engineered Systems

Table 1: Comparative nitrite accumulation parameters across different environments

| Environment/System | Nitrite Concentration | Key Controlling Factors | Primary Microbial Actors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic OMZs (SNM) | ~2 μM (ecological accumulation) | Dynamic OM pulses, trace O₂ intrusions | NOB, nitrate-reducers, nitrite-reducers [27] |

| Low-strength wastewater | Influent TN: 81.5 ± 5.6 mg/L | Acetate addition, DO < 0.4 mg/L | DNB, NOB, AOB, AnAOB [28] |

| SAD system (optimal) | TN removal: 86.2 ± 1.2% | Mid-level inlet, biofilm carriers | HDB, AnAOB [29] |

| Tetracycline-affected SAD | Enhanced TN removal: 95.6-95.9% | TC (0.05-0.5 mg/L), TB-EPS secretion | HDB (temporarily inhibited), AnAOB [29] |

Performance Metrics in Engineered Systems

Table 2: Performance parameters of anammox-based systems under various conditions

| System Condition | Nitrogen Loading Rate | Removal Efficiency | Critical Microbial Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rare earth tailings leachate | 1.38 ± 0.01 kg/m³·d (stable) | NRR: 1.15 ± 0.02 kg/m³·d | AnAOB abundance: 5.85-11.43% [30] |

| Excessive nitrogen loading | >3.68 kg/m³·d | Performance deterioration | Reduced AnAOB abundance [30] |

| Acetate-regulated PN/A | Start-up: 47 days | Simultaneous initiation achieved | Negative NOB-DNB correlation [28] |

| Starvation conditions | Nitrogen starvation | Performance deterioration | Modularity index: 0.545 [30] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Marine Microbial Ecology Studies

Research elucidating the nitrite accumulation mechanism in oceanic OMZs employed a multi-scale modeling approach. The methodology began with a zero-dimensional ecosystem model configured to represent conditions at the top of the anoxic layer where abundant organic matter and low oxygen coexist [27]. This model incorporated redox-informed parameterizations for diverse metabolic functional types and supplied pulses of organic matter to mimic time-varying productivity resulting from small-scale ocean circulation patterns [27].

The experimental framework was validated through eddy-resolving three-dimensional regional ocean modeling of the Eastern Tropical South Pacific OMZ [27]. This sophisticated approach captured spatial and temporal heterogeneity in surface primary productivity that leads to realistic variability in sinking organic matter flux to anoxic zones. The model simulated microbial functional types and their interactions across realistic oceanographic gradients, enabling researchers to compare patterns and relative quantities with observational data from both the ETSP and ETNP OMZs [27].

Engineered System Experimental Designs

Partial Nitrification and Anammox Configuration

A key experimental system for investigating these microbial interactions employed series-connected partial nitrification and anammox bioreactors for municipal sewage treatment with low-strength nitrogen (20-60 mg/L) [28]. The partial nitrification stage utilized a sequencing batch reactor with an effective working volume of 12 L, employing high-frequency aeration (12 times/hour) and micro-aeration periods with dissolved oxygen concentration maintained below 0.4 mg/L [28].

The experimental design incorporated a short-range bio-screening phase using acetate as a regulatory factor to induce double-advantage mechanisms: inhibition of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria activity and induction of mixotrophic anammox [28]. Following bio-screening, researchers investigated partial nitrification performance, anammox efficiency, and overall wastewater treatment effectiveness through systematic monitoring of nitrogen species transformation and microbial community structure analysis.

Simultaneous Anammox and Denitrification System

Another methodological approach employed a simultaneous anammox and denitrification filter column reactor with mid-level inlet configuration to integrate anammox with biofilm denitrification [29]. This design enabled gradient carbon supply and spatially regulated microbial communities. The rising-flow filter column reactor (1.1 L effective volume) was filled to approximately 50% capacity with polyethylene K1 biofilm carriers and operated in dual inlet-single outlet mode [29].

The experimental protocol involved introducing ammonium chloride and sodium nitrite through the bottom inlet while supplying organic carbon source (sodium acetate) through the middle inlet port. This created differentiated redox zones within a single reactor system: the lower section favoring anammox metabolism and the upper section facilitating denitrification activity [29]. System performance was assessed through long-term monitoring of nitrogen transformation efficiency under varying tetracycline stress (0.05-0.5 mg/L).

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for microbial nitrogen cycling studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium acetate (CH₃COONa) | Organic carbon source for denitrifiers; regulatory factor for NOB inhibition | Low-strength wastewater treatment; microbial interaction studies [28] |

| Polyethylene K1 biofilm carriers | 15 mm nominal diameter; provide attachment surface for biofilm formation | SAD reactor configuration; enhanced biomass retention [29] |

| Tetracycline (TC) | Antibiotic stressor (0.05-0.5 mg/L); induces EPS secretion | Microbial community response studies; stress tolerance mechanisms [29] |

| Trace element Solutions I & II | I: EDTA and FeSO₄·7H₂O; II: EDTA with Mo, Ni, Cu, Co, Zn, Mn salts | Essential micronutrients for anammox and denitrifying bacteria [30] |

| Sequencing Batch Reactor (SBR) | 12 L working volume; high-frequency aeration (12 times/h) | Partial nitrification studies; NOB activity control [28] |

| Expanded Granular Sludge Bed (EGSB) | 10 L Plexiglas reactor; insulated against light and temperature fluctuations | Anammox process studies; nitrogen loading fluctuation experiments [30] |

Visualization of Microbial Interaction Pathways

Nitrite Accumulation Mechanism in Oxygen Minimum Zones

Microbial Competition Driving Nitrite Accumulation - This diagram illustrates the sequence of microbial interactions following organic matter pulses that lead to nitrite accumulation in anoxic waters, highlighting the paradoxical role of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria.

Engineered System Microbial Community Dynamics

Engineered System Microbial Responses - This workflow depicts how acetate regulation induces dual advantages in engineered systems: inhibiting NOB while stimulating denitrifying bacteria and anammox bacteria through different mechanisms.

Discussion and Research Implications

The discovery that nitrite-oxidizing bacteria contribute to nitrite accumulation represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of nitrogen cycling in anoxic environments. This mechanism, validated across both natural oceanic systems and engineered bioreactors, highlights the universal importance of dynamic microbial interactions in shaping biogeochemical pathways. The consistent observation of this phenomenon across disparate environments suggests these competitive interactions represent a fundamental ecological principle in nitrogen-transforming microbial communities.

From an applied perspective, these insights offer novel approaches for optimizing wastewater treatment systems. The use of acetate as a regulatory factor to manipulate microbial competition demonstrates how ecological principles can be translated into engineering strategies [28]. Similarly, the finding that tetracycline stress can enhance rather than diminish nitrogen removal efficiency in certain configurations reveals the remarkable resilience of microbial communities and their capacity to adapt to environmental stressors [29]. These findings have significant implications for designing more robust, efficient biological treatment systems, particularly for low-strength wastewater and antibiotic-containing effluents.

Future research directions should focus on quantifying the rates and thresholds of these competitive interactions under varying environmental conditions. Additionally, investigation into the genomic underpinnings of the metabolic flexibility exhibited by NOB and anammox bacteria would provide deeper insights into the evolutionary adaptations that enable these unusual ecological dynamics. As climate change and anthropogenic pressures continue to expand oceanic oxygen minimum zones, understanding these complex microbial interactions becomes increasingly critical for predicting changes in global nitrogen cycling and its consequences for marine productivity and greenhouse gas emissions.

From Sample to Insight: Modern Methodologies and Their Applications in Microbial Ecology

The study of microbial communities has been revolutionized by culture-independent molecular techniques that allow researchers to investigate microorganisms in their natural environments. 16S rRNA gene sequencing, metagenomics, and metatranscriptomics form a core toolkit for exploring microbial diversity, functional potential, and active functional roles within complex ecosystems [31]. These methods have transformed our understanding of microbial ecology and environmental interactions by revealing the vast diversity of unculturable microorganisms and their complex community dynamics [32] [31].

Each technique provides a different lens through which to view microbial communities: 16S rRNA sequencing profiles community composition, metagenomics reveals the collective genetic potential, and metatranscriptomics captures the actively expressed functions [33] [34]. When integrated, these approaches provide a comprehensive picture of microbial community structure and function, enabling researchers to connect taxonomic identity with metabolic capability and activity in diverse environments from human body sites to extreme ecosystems [32] [35].

Methodological Foundations

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

The 16S ribosomal RNA gene is a conserved genetic marker found in all bacteria and archaea that contains both highly conserved regions, useful for primer binding, and variable regions that provide taxonomic resolution [36]. 16S rRNA gene sequencing involves amplifying and sequencing this gene to identify and compare microbial taxa present in a sample [33]. This approach is particularly valuable for its cost-effectiveness and robust protocols for microbial profiling and phylogenetic studies [33].

Traditional short-read sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene often targets specific hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4 or V4-V5), which limits taxonomic resolution to genus or family level [36]. However, long-read sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore, can sequence the entire ~1.5 kb 16S rRNA gene, spanning V1-V9 regions in a single read, enabling more accurate species-level identification even from polymicrobial samples [36] [37]. The wet lab process involves DNA extraction, PCR amplification with 16S-specific primers, library preparation, and sequencing, followed by bioinformatic analysis using tools like EPI2ME wf-16s or QIIME2 [36].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Target | 16S ribosomal RNA gene (~1.5 kb) |

| Primary Application | Taxonomic profiling, microbial diversity, phylogenetic analysis |

| Resolution | Species-level with full-length sequencing; genus-level with partial gene sequencing |

| Key Strength | Cost-effective for large cohort studies; well-established bioinformatics tools |

| Limitation | Does not directly provide functional information; potential PCR amplification biases |

Shotgun Metagenomics

Shotgun metagenomics involves randomly shearing all DNA in a sample—bacterial, archaeal, viral, and eukaryotic—into short fragments that are sequenced and then computationally reassembled [31]. This approach provides a comprehensive view of the genetic material present in an environment, allowing researchers to assess both the taxonomic composition and the functional potential of microbial communities [33] [31].

Unlike 16S sequencing, shotgun metagenomics enables the study of unculturable microorganisms and allows for the identification of specific functional genes and metabolic pathways [33]. The method involves DNA extraction, library preparation without target-specific amplification, and high-throughput sequencing [33] [35]. The resulting data can be analyzed for taxonomic composition using tools like Kraken 2 or MetaPhlAn, and for functional potential using HUMAnN 3 or similar pipelines [35] [34]. Sequencing depth is a critical consideration, with higher depth enabling more complete genome recovery and better detection of rare taxa [31].

Table 2: Shotgun Metagenomics Workflow Components

| Workflow Step | Technologies & Methods |

|---|---|

| Sample Homogenization | Omni homogenizers, bead mills (e.g., Omni Bead Ruptor) [33] |

| Nucleic Acid Isolation | chemagic technology, kits for complex samples [33] |

| Library Preparation | NEXTFLEX Rapid XP kits, automated liquid handling systems [33] |

| Sequencing | Illumina, Oxford Nanopore, PacBio platforms [31] |

| Bioinformatic Analysis | CosmosID-HUB, Kraken 2, HUMAnN 3 [33] [34] |

Metatranscriptomics

Metatranscriptomics focuses on sequencing the total RNA from a microbial community to profile gene expression patterns and identify actively expressed metabolic pathways [34]. This approach provides insights into the functional activities of microbial communities under specific environmental conditions, revealing how microorganisms respond to their environment and interact with each other and their hosts [34].

The metatranscriptomics workflow involves RNA extraction, removal of ribosomal RNA (which can constitute >90% of total RNA), library preparation, and sequencing [34]. A major challenge, particularly for human tissue samples with low microbial biomass, is the high background of host RNA which can consume most of the sequencing capacity [34]. Effective analysis of metatranscriptomic data requires specialized computational workflows that integrate optimized taxonomic classification (e.g., Kraken 2/Bracken) with functional analysis (e.g., HUMAnN 3) to accurately identify microbial species while minimizing false positives [34].