Microbial DNA Extraction Mastery: A Comprehensive Guide to Sample Preparation for Accurate Sequencing and Diagnostics

This article provides a complete guide to microbial DNA sample preparation, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Microbial DNA Extraction Mastery: A Comprehensive Guide to Sample Preparation for Accurate Sequencing and Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a complete guide to microbial DNA sample preparation, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of why sample quality dictates sequencing success, details specialized protocols for diverse sample types like blood, urine, and stool, and offers advanced troubleshooting for challenging matrices. The guide also presents rigorous validation data comparing extraction technologies and methods, empowering scientists to achieve high-yield, inhibitor-free microbial DNA for reliable downstream molecular analysis in both research and clinical diagnostics.

The Critical Role of Sample Preparation in Microbial Genomics

Why Sample Quality is the Cornerstone of Sequencing Success

In next-generation sequencing (NGS), the quality of the input sample is the most significant determinant of success or failure. Even with advanced sequencers and optimized library preparation kits, compromised DNA or RNA can derail an entire sequencing run, leading to inconclusive results, wasted resources, and delayed research outcomes [1]. For microbial DNA extraction, this is particularly crucial, as the genetic material must be pure, intact, and representative of the microbial population for accurate downstream analysis in diagnostics, drug development, and genomic research.

The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" is acutely applicable to sequencing. Enzymatic efficiency in library preparation depends on sample purity, as contaminants inhibit the enzymes responsible for end repair, adapter ligation, and amplification [1]. Furthermore, fragment integrity directly affects sequencing yield and read mapping; highly fragmented DNA leads to inefficient cluster generation and poorer assembly, especially critical when sequencing microbial isolates for antimicrobial resistance profiling or outbreak tracing [1] [2]. Empirical evidence underscores this: an extensive analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues demonstrated that samples with high DNA integrity yielded NGS success rates of ~94%, compared to a mere ~5.6% for low-integrity samples [1]. This result highlights that no downstream rescue can fully compensate for poor starting material, making rigorous quality control (QC) the non-negotiable first step in any robust sequencing workflow.

Essential Quality Control Metrics and Assessment Methods

A disciplined, stepwise QC workflow is required to reliably convert raw biological material into sequencing-ready nucleic acids. Post-extraction validation of nucleic acid concentration, purity, and integrity is mandatory before proceeding to library preparation [1]. The following metrics provide a comprehensive picture of sample quality.

Table 1: Essential Quality Control Metrics for Sequencing Sample Preparation

| QC Metric | Assessment Method | Ideal Value/Range | Impact of Deviation from Ideal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration/Mass | Fluorometry (e.g., Qubit with dsDNA BR/HS Assay) [1] [3] | Varies by protocol & sample type | Underloading wastes sequencer capacity; overloading reduces cluster quality [1] |

| Purity (A260/280) | UV Spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) [1] [3] | ~1.8 (DNA), ~2.0 (RNA) [1] [4] | Ratio <1.8 indicates protein/phenol contamination; >1.8 suggests RNA contamination [3] |

| Purity (A260/230) | UV Spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) [1] [3] | 2.0–2.2 [3] | Ratio <2.0 indicates salt or organic solvent carryover [3] |

| DNA Integrity/Size | Gel Electrophoresis, Bioanalyzer/TapeStation, Pulsed-Field Gel (>10 kb) [1] [3] [5] | Sharp, high molecular weight band [3] | Fragmentation/shearing leads to inefficient clustering, poorer read mapping, and assembly gaps [1] |

| RNA Integrity (RIN) | Bioanalyzer/TapeStation [4] | 10 (High Integrity) [4] | Low RIN indicates degradation, compromises gene expression analysis [4] |

Practical Assessment of QC Metrics

Quantification: Fluorometric assays (Qubit) are preferred over spectrophotometry for precise quantification because they specifically measure DNA and are not influenced by contaminants like residual RNA or nucleotides [1] [3]. For long-read sequencing platforms like PacBio HiFi, requiring high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA, a minimum of >500 ng to >2 µg of HMW DNA is recommended for whole-genome sequencing [5].

Purity Checks: The A260/280 and A260/230 ratios are a first screen for contaminants. A low A260/230 ratio, for instance, necessitates additional purification steps, as the sample may contain salts or organic compounds that will inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions [3]. If additional purification is not feasible, PCR amplification can sometimes improve quality for downstream applications [3].

Integrity and Size Assessment: Verifying that DNA is of high molecular weight is critical, especially for long-read sequencing. Conventional agarose gels cannot resolve fragments >15–20 kb, so pulsed-field gel electrophoresis or the Agilent Femto Pulse System is recommended for large fragments [3] [5]. For RNA, the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) provides a standardized score from 1 (degraded) to 10 (intact) [4].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Microbial DNA Extraction and QC

The following protocols provide methodologies for extracting DNA from microbial isolates and conducting thorough quality control, ensuring the sample is suitable for high-quality sequencing.

Protocol: DNA Extraction from Microbial Isolates using a Universal Bead-Beating Method

This protocol, adapted from the Nanopore NO-MISS workflow, is designed for robust lysis of diverse bacteria and fungi/yeast and is scalable for automation [2].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Harvest 1 ml of a liquid overnight microbial culture (approximately 1 x 10^8 – 10^9 CFU/ml) by centrifugation [2].

- Resuspend the cell pellet thoroughly in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

2. Cell Lysis:

- Transfer the resuspended cells to a bead-beating tube (e.g., PowerBead Pro tube).

- Add lysis buffer. For broad-spectrum applications, BashingBead Buffer can be used [2].

- Securely cap the tube and lyse the cells using a vortex adapter or a dedicated bead-beating instrument for a defined duration (e.g., 5-10 minutes).

- For hard-to-lyse organisms like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the protocol must be tailored. This involves using specialized lysing matrix tubes with glass beads and incorporating lysozyme and achromopeptidase into the lysis buffer to break down tough cell walls [2].

3. DNA Binding and Purification:

- Following bead-beating, centrifuge the tube to pellet debris.

- Transfer the supernatant containing the nucleic acids to a new tube.

- Perform DNA binding, washing, and elution using a commercial column-based or magnetic bead-based kit, such as the NEB Monarch Spin gDNA Extraction Kit or the Promega Maxwell RSC PureFood Pathogen Kit [2].

- Elute the purified genomic DNA (gDNA) in a low-EDTA elution buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0-8.5) compatible with downstream enzymatic steps [1].

Protocol: Quality Control Assessment for Extracted DNA

This procedure outlines the critical checks to perform on the eluted DNA before proceeding to library preparation.

1. Fluorometric Quantification (e.g., Qubit):

- Use the Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity (HS) or Broad Range (BR) Assay Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions [3] [6].

- This provides an accurate measurement of the double-stranded DNA concentration, which is crucial for calculating the required input for library preparation.

2. Spectrophotometric Purity Assessment (e.g., NanoDrop):

- Dilute 1-2 µL of the eluted DNA in nuclease-free water for the blank measurement.

- Measure the absorbance at 230 nm, 260 nm, and 280 nm.

- Record the A260/280 and A260/230 ratios. Acceptable ranges are ~1.8 for DNA (A260/280) and >1.8 for A260/230 [1] [3]. Significant deviations indicate the need for an additional clean-up step, such as a SPRI bead purification [1].

3. Integrity Analysis (e.g., Gel Electrophoresis or TapeStation):

- For a quick integrity check, run 100-200 ng of the DNA on a 0.8% - 1% agarose gel.

- Intact genomic DNA should appear as a tight, high-molecular-weight band with minimal smearing toward the lower molecular weight region, which would indicate degradation [3] [6].

- For a more quantitative assessment, use an automated electrophoresis system like the Agilent TapeStation or Bioanalyzer, which provides a digital sizing and quantification profile [1].

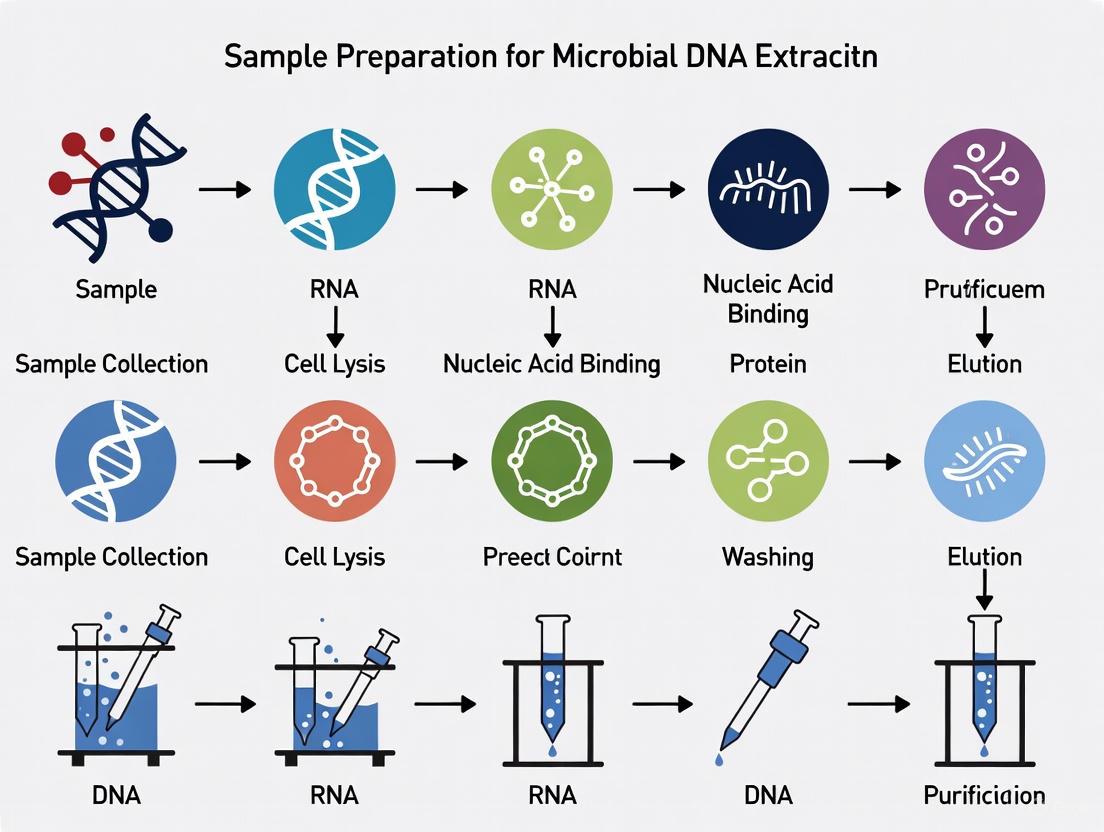

Diagram 1: Microbial DNA extraction and quality control workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Equipment

Successful sequencing begins with the right tools. The following table details essential reagents, consumables, and equipment for microbial DNA extraction and quality control.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial DNA Extraction and QC

| Category | Item | Specific Example | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Kits | Nanobind PanDNA Kit [5] | PacBio (PN 103-260-000) | Delivers ultra-clean, high-molecular-weight DNA from blood, tissue, insects, plants, cultured cells, and bacteria. |

| Maxwell RSC PureFood Pathogen Kit [2] | Promega (AS1660) | Automated bead-beating gDNA extraction for high-throughput requirements and universal applications. | |

| QC Instruments | Qubit Fluorometer [1] [3] | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Precisely quantifies dsDNA mass; unaffected by contaminants like RNA. |

| Automated Electrophoresis System [1] [4] | Agilent TapeStation / Bioanalyzer | Assesses DNA/RNA integrity and size distribution (e.g., provides RIN for RNA). | |

| Specialty Reagents | Agencourt AMPure XP Beads [2] | Beckman Coulter (A63881) | SPRI beads for post-extraction clean-up and size selection to remove short fragments. |

| Short Read Eliminator (SRE) Kit [5] | PacBio | Selectively removes DNA fragments below 10 kb, crucial for long-read sequencing. | |

| Enzymes for Lysis | Lysozyme [2] | Sigma (L1667) | Breaks down bacterial cell walls (e.g., for E. coli, K. pneumoniae). |

| MetaPolyzyme [2] | Sigma (MAC4L-5MG) | Enzyme blend for digesting fungal/yeast cell walls. | |

| Consumables | Bead-Beating Tubes [2] | PowerBead Pro Tubes (Qiagen) | Contains ceramics/silica for mechanical disruption of tough cell walls. |

Troubleshooting: Common Sample Quality Issues and Solutions

Even with optimized protocols, challenges can arise. The table below outlines common problems, their potential causes, and evidence-based solutions.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Microbial DNA Extraction

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA Yield | Incomplete cell lysis, low starting material, or inefficient elution. | Optimize lysis conditions (e.g., use bead-beating for tough cells, extend lysis time). Use warm elution buffer and incubate on the matrix for 2-3 minutes before centrifuging [1]. |

| Low A260/230 Ratio (Salt Contamination) | Incomplete removal of wash buffer or residual ethanol [3]. | Ensure complete removal of supernatant after ethanol wash steps. Do not overdry the pellet, as this can make re-dissolution inefficient. Perform an additional 70% ethanol wash [1]. |

| Low A260/280 Ratio (Protein Contamination) | Incomplete protein digestion or phenol carryover from organic extraction. | Ensure sufficient Proteinase K digestion during lysis. For column-based kits, ensure complete buffer exchange during washing steps [1] [7]. |

| Fragmented DNA / Low Integrity | Overly vigorous pipetting, vortexing of HMW DNA, or nuclease activity [3] [5]. | Use wide-bore pipette tips. Avoid vortexing DNA samples; instead, mix by gentle flicking or inversion. Aliquot samples to minimize freeze-thaw cycles. Store long-term at -80°C in TE buffer [1] [3]. |

| Presence of Inhibitors | Carryover of polysaccharides (plants), humic acids (soil), or heme (blood) [1] [7]. | Tailor extraction to the sample. For challenging matrices, use additional cleanup steps, specialized buffers (e.g., CTAB for plants), or inhibitor removal columns [1]. |

| High Host (Human) DNA in Microbial Samples | Failure to enrich for microbial cells or lyse human cells. | For metagenomic samples, consider differential lysis steps or probe-based host depletion methods to increase the proportion of microbial sequences [8]. |

Diagram 2: Common sample quality issues and their solutions.

The path to successful sequencing data is paved long before the sample is loaded onto the sequencer. It begins at the very first step: the extraction and rigorous quality control of the nucleic acids. As demonstrated, sample quality is not a peripheral consideration but the very cornerstone of sequencing success, directly impacting enzymatic efficiency, library complexity, and the ultimate accuracy and reliability of the results. By adopting the detailed protocols, standardized QC metrics, and troubleshooting strategies outlined in this application note, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly enhance the reproducibility and quality of their microbial genomics work. Investing time and rigor in sample preparation is the most effective strategy to ensure that a sequencing project is built on a solid foundation, ultimately saving valuable time and resources while generating robust, actionable data.

The efficacy of microbial detection, genotyping, and metagenomic analysis is fundamentally contingent upon the initial quality of the extracted DNA. Effective DNA extraction is the cornerstone of molecular biology research, diagnostics, and forensic applications worldwide [7]. The process is fraught with sample-specific challenges that, if not adequately addressed, can lead to significant bias in downstream results, including false negatives in pathogen detection or distorted representations of microbial community structures [9] [10]. These challenges range from the physical disruption of robust cellular structures to the chemical mitigation of co-purified compounds that inhibit enzymatic reactions. This application note delineates the predominant obstacles encountered during DNA isolation from diverse sample types and provides detailed protocols and solutions tailored to overcome these hurdles, ensuring the acquisition of high-quality genetic material for sensitive downstream applications.

Sample-Specific Challenges and Solutions

The journey to high-quality DNA begins with recognizing and addressing the unique biochemical and physical properties of each sample type. The following sections detail the most common challenges and the strategic approaches required for different categories of samples.

Rigid Cell Walls

The robust structural components of many microbial and plant cells present a primary barrier to efficient DNA extraction.

- Microbial Cell Walls: Gram-positive bacteria, spores, and yeast feature tough cell walls that resist standard lysis methods. For instance, the rigidity of Bacillus cereus spores and the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae necessitates rigorous mechanical disruption for efficient DNA recovery [9]. Similarly, the green microalga Chlorella vulgaris is notorious for its resilient cell walls, often cited as a major impediment to DNA extraction [11].

- Plant Tissues: Plant materials are challenging due to their rigid cellulose-based cell walls and the presence of secondary metabolites like polysaccharides and polyphenols, which can co-purate with DNA and interfere with downstream applications such as PCR [7].

Solutions:

- Mechanical Disruption: Bead beating is a widely used method to physically break open tough cell walls. The use of homogenizers, such as the Fisherbrand 850 Homogenizer, can yield higher DNA quantities from tough tissues than bead beating alone [7].

- Chemical and Enzymatic Lysis: Specialized kits, such as the Thermo Scientific GeneJET Plant Genomic DNA Purification Kit, often incorporate polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to bind and remove polyphenolic compounds [7]. For microalgae like C. vulgaris, research indicates that accumulated lipids, rather than the cell wall itself, can be the primary impediment for colony PCR. A simple extraction with TE or SDS buffer, followed by a hexane or phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol step to remove lipids, enables effective PCR amplification [11].

PCR Inhibitors

Various biological samples contain endogenous or exogenous compounds that can co-purify with DNA and potently inhibit the polymerases used in PCR and other enzymatic assays.

- Sources and Types: Blood and other bodily fluids contain inhibitors like heme (from hemoglobin) and mucin. Stool samples are complex matrices rich in bilirubin, bile salts, and complex polysaccharides. Plant tissues contain polysaccharides and polyphenols, while formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples can carry over formalin and paraffin [7] [9].

- Impact: These inhibitors can bind directly to the DNA or interact with the DNA polymerase, leading to reduced amplification efficiency, increased cycle threshold (Ct) values in qPCR, or complete amplification failure, resulting in false negatives [9] [12].

Solutions:

- Specialized Lysis and Washing: Protocols for inhibitor-rich samples often incorporate focused lysis and digestion steps. For blood, this involves "forceful but focused lysis and digestion" to break open cells without damaging the DNA, while simultaneously digesting contaminating proteins [7].

- Magnetic Bead Purification: Bead-based chemistries, such as those in the MagMAX product line, are designed to efficiently bind DNA while allowing stringent washes that remove a wide array of PCR inhibitors. These workflows increase throughput and uniformity, promoting high-quality genomic DNA results [7].

- Validation with Inhibition Assays: Incorporating an internal positive control (IPC) in qPCR reactions is critical for detecting the presence of inhibitors. An IPC involves adding a known quantity of exogenous DNA template; a delay in its amplification signal (higher Ct) indicates the presence of inhibitors in the sample [12].

Low Biomass and Complex Samples

Samples with low microbial load or those comprising complex communities present unique challenges for representative and efficient DNA recovery.

- Low Biomass: Samples like potable water or certain clinical swabs may contain very few bacterial cells, making concentration a necessary pre-step to DNA extraction [13].

- Microbiome Studies: Complex communities, such as those found in the human gut or vagina, contain a diverse mix of species with differing cell wall structures. DNA extraction methods must lyse all species equally to avoid biasing the apparent community structure [14] [10].

Solutions:

- Sample Concentration: For water samples, concentrating bacterial cells via membrane filtration prior to DNA extraction is a common and effective strategy [13].

- Method Selection for Representativeness: Studies comparing DNA extraction methods for microbiome research have shown that the choice of method significantly impacts the observed microbial diversity. For example, one study found that the Qiagen DNeasy kit provided the highest DNA yield from vaginal swabs, but a modified MoBio PowerSoil protocol detected a significantly higher alpha diversity, indicating better lysis of a broader range of bacterial species [14]. Phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction often provides the highest DNA yield from a mock microbial community, but may not always provide the most representative profile [10].

Specialized and Fixed Samples

Some samples require specific handling due to their unique preservation or structural properties.

- Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Samples: These are among the most challenging samples due to the DNA-protein crosslinks formed by formalin and the embedding paraffin that must be removed. Traditional methods use multiple xylene and ethanol washes, which are tedious and environmentally harmful [7].

- Solution: Automated, safer alternatives are recommended. Systems like the Applied Biosystems AutoLys M Tubes and Caps for deparaffinization, combined with MagMAX FFPE DNA/RNA Isolation chemistry, use heating steps and proteinase K digestion instead of hazardous solvents, streamlining the workflow [7].

Table 1: Summary of Sample-Specific DNA Extraction Challenges and Strategic Solutions

| Sample Type | Primary Challenges | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Blood & Bodily Fluids | PCR inhibitors (heme, mucin) [7] | Focused lysis/digestion; magnetic bead purification [7] |

| Plant Tissues | Rigid cell walls; polysaccharides/polyphenols [7] | Mechanical homogenization; kits with PVP [7] |

| Gram-positive Bacteria & Spores | Tough cell walls resistant to lysis [9] | Intensive mechanical disruption (e.g., bead beating) [9] |

| Microalgae (C. vulgaris) | Accumulated lipids impede DNA release [11] | Lipid removal with organic solvents (e.g., PCI) [11] |

| FFPE Tissues | DNA-protein crosslinks; paraffin embedding [7] | Dewaxing; proteinase K digestion; automated systems [7] |

| Stool & Complex Microbiomes | Diverse inhibitors; mixed community lysis bias [7] [10] | Inhibitor removal technology; method validated for representativeness [7] [14] |

| Low Biomass (Water) | Low concentration of bacterial cells [13] | Cell concentration via filtration [13] |

Quantitative Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods

The performance of DNA extraction methods can be quantitatively evaluated based on yield, purity, and suitability for downstream applications. Different measurement techniques also have varying limits of detection, which is critical for low-concentration extracts.

Performance Across Sample Types

A study evaluating six DNA extraction methods on a mock microbial community found significant variance in DNA yield. The phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (organic) method consistently produced the highest DNA yields for most bacterial species, significantly outperforming several commercial kits—yielding over 5 times more DNA for Staphylococcus aureus and Propionibacterium acnes [10]. However, high yield does not always correlate with accurate community representation. The same study calculated the Euclidean distance between the observed and expected microbial community structure, finding that some commercial kits (Method 1 & 2) provided a significantly better representation than the organic method and others [10].

DNA Quantification and Purity Analysis

Accurate DNA quantification is vital, and the choice of method depends on the sample concentration and required specificity.

- UV Spectroscopy: Measures absorbance at 260 nm. The A260/A280 ratio indicates protein contamination (pure DNA ~1.8-2.0), and the A260/A230 ratio indicates contamination from salts or organic compounds (pure DNA ~1.8-2.2). Its reproducibility decreases significantly for concentrations below ~17.5 ng/μL [9].

- Fluorometry: More specific for DNA than UV spectroscopy and far more sensitive, with a typical limit of detection as low as 0.00025 ng/μL. It is less affected by contaminants like RNA [9].

- qPCR: The most specific method, as it only quantifies the target sequence that is intact and accessible. It is also the most sensitive, with limits of quantification (LOQ) reported as low as 0.000767 ng/μL for S. cerevisiae. It is the only method that can directly detect the presence of PCR inhibitors via an internal positive control [9].

Table 2: Limits of Quantification (LOQ) for DNA Concentration Measurement Methods

| Measurement Method | Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| UV Spectroscopy | ~3.5 ng/μL [9] | Affected by RNA, free nucleotides, and other contaminants [9]. |

| Fluorometry | ~0.25 ng/μL [9] | More DNA-specific than UV spectroscopy; sensitive [9]. |

| qPCR | Varies by target; e.g., 7.67x10-4 ng/μL for S. cerevisiae [9] | Target-specific; confirms amplifiability and detects inhibitors [9]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In-House Guanidinium Thiocyanate DNA Extraction for Water Samples

This protocol is designed as a cost-effective and reproducible method for extracting DNA from bacterial cells concentrated from water samples [13].

Materials and Reagents:

- Lysis Buffer: 120 g guanidinium thiocyanate dissolved in 100 mL of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.4), with 22 mL of 0.2 M EDTA (pH 8.0) and 2.6 mL Triton X-100 added after heating to 60°C.

- Washing Buffer: 120 g guanidinium thiocyanate in 100 mL of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.4).

- Celite suspension, 100% Ethanol, 70% Ethanol.

- Prepared spin columns (0.5 mL tube with silica membrane).

Procedure:

- Cell Concentration: Filter the water sample through a polycarbonate membrane. Place the membrane in a cryovial with 2.5 mL sterile distilled water and vortex for 2 minutes. Transfer the suspension to a 2 mL tube.

- Pellet Cells: Centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 10 minutes. Discard the supernatant.

- Cell Lysis: Add 1000 μL of lysis buffer to the pellet. Incubate at 70°C for 10 minutes.

- DNA Binding: Add 200 μL of 100% ethanol to the tube and mix gently. Incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes.

- Silica Binding: Transfer 400 μL of the lysate to a prepared spin column. Centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 1 minute to bind DNA to the silica membrane. Discard the flow-through.

- Wash: Add 500 μL of wash buffer to the column and centrifuge as before. Discard the flow-through. Repeat with 500 μL of 70% ethanol.

- Elution: Centrifuge the empty column for 1 minute to dry the membrane. Transfer the column to a clean 1.5 mL tube and elute DNA by adding 50-100 μL of pre-warmed (70°C) elution buffer (e.g., TE) or nuclease-free water. Centrifuge for 1 minute. The eluate contains the purified DNA.

Protocol 2: Thermo-Osmotic DNA Extraction for Contingency and Field Use

This minimalist protocol uses only boiling water to lyse cells and is suitable for highly enriched, uncomplicated samples (e.g., fungal mycelia, buccal swabs) in resource-limited settings [15].

Materials and Reagents:

- Commercially available distilled water.

- 70% Ethanol (for surface sterilization).

- 1.5 mL and 0.2 mL microtubes.

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect the sample (e.g., by swabbing the inner cheek or excising a piece of fungal mycelium) and place it in a 1.5 mL microtube.

- Heat Lysis: Fill a 50 mL Falcon tube halfway with distilled water and place it in a beaker half-filled with tap water acting as a water bath. Boil the water bath. Use a Pasteur pipette to add 200-500 μL of boiling water to the sample tube. Close the lid and stir vigorously.

- Incubation: Place the sample tube in the floating rack within the boiling water bath. Incubate for 20-30 minutes.

- Crude Lysate and Dilution: The resulting crude lysate can be directly used for PCR. To optimize the DNA-to-inhibitor ratio, prepare two decimal serial dilutions (1:10 and 1:100) of the lysate using distilled water.

- Direct PCR: Use 2–5 μL of the crude lysate and each dilution as a template in direct PCR to determine which provides the best amplification.

Workflow and Strategic Selection

The following workflow diagram outlines the logical process for selecting an appropriate DNA extraction strategy based on sample properties and research goals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Overcoming DNA Extraction Challenges

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Guanidinium Thiocyanate | Chaotropic salt; denatures proteins, promotes nucleic acid binding to silica [13]. | Core component of in-house and kit-based lysis/binding buffers [13]. |

| PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | Binds and removes polyphenolic compounds from plant extracts [7]. | Added to plant-specific DNA extraction protocols to improve purity [7]. |

| Magnetic Beads (e.g., MagMAX kits) | Solid phase for DNA binding; enables efficient washing to remove inhibitors [7]. | High-throughput purification from diverse samples (blood, tissue, microbes) [7]. |

| Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol | Organic extraction; denatures and removes proteins and lipids [11] [10]. | Effective for lipid-rich samples (e.g., microalgae) [11]; yields high DNA [10]. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease; digests proteins and nucleases [7]. | Essential for lysis of protein-rich tissues and de-crosslinking FFPE samples [7]. |

| RNase A | Degrades RNA to prevent contamination of DNA extracts [7]. | Used in tissue DNA extraction to reduce RNA contamination and improve quality ratios [7]. |

| Spin Columns with Silica Membrane | Solid phase for DNA binding, washing, and elution in a simple format [13]. | Foundation of many commercial kits; suitable for most sample types [13]. |

Navigating the landscape of sample-specific challenges in DNA extraction is a critical first step in any robust molecular biology pipeline. As demonstrated, a one-size-fits-all approach is ineffective. Success hinges on selecting a tailored strategy that accounts for the sample's physical structure, biochemical composition, and the specific requirements of the downstream application. By understanding the nature of challenges such as rigid cell walls, PCR inhibitors, and low biomass, and by leveraging the appropriate tools and protocols—from mechanical homogenization and specialized kits to minimalist field protocols—researchers can consistently obtain high-quality DNA. This ensures the reliability, accuracy, and reproducibility of their data, from clinical diagnostics and forensic analysis to groundbreaking microbial ecology research.

Within the broader context of sample preparation for microbial DNA extraction research, the success of downstream applications—from quantitative PCR (qPCR) to next-generation sequencing (NGS)—is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the isolated nucleic acids. For researchers and drug development professionals, accurately assessing DNA quality is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant of data reliability and experimental reproducibility. This protocol outlines the essential quality control (QC) metrics—yield, purity, and integrity—for evaluating microbial DNA. We provide detailed methodologies for their measurement, supported by structured data and practical workflows, to ensure that extracted DNA meets the stringent requirements of modern molecular analyses.

Key Quality Metrics: Definition and Significance

The quality of microbial DNA can be deconstructed into three primary, measurable metrics. A comprehensive understanding of each is vital for interpreting QC results and ensuring sample suitability.

DNA Yield

DNA yield refers to the total quantity of DNA recovered from a sample. It is a primary indicator of extraction efficiency.

- Measurement Techniques: Yield is most commonly quantified using spectrophotometry (absorbance at 260 nm) or the more sensitive and DNA-specific fluorometry [16] [17].

- Spectrophotometric Considerations: Absorbance measurements are reliable only within a specific range (A260 between 0.1 and 1.0). Highly concentrated samples require dilution, whereas measurements at low concentrations can be skewed by contaminants or dust [16].

- Comparative Performance: A recent study comparing quantification methods found that qPCR (using Cycle Threshold values) demonstrated the highest precision (CV of 4.0%), followed by fluorometry (CV of 17.54%). Spectrophotometry showed the highest variability (CV of 21.28%), making it less reliable for precise yield determination despite its convenience [17].

DNA Purity

DNA purity assesses the presence of contaminants that can inhibit enzymatic reactions in downstream applications. It is evaluated using absorbance ratios [18] [16] [19].

Table 1: Spectrophotometric Purity Ratios and Their Interpretation for Microbial DNA

| Purity Ratio | Ideal Value for Pure DNA | Significance | Common Contaminants Indicated by Low Ratios |

|---|---|---|---|

| A260/A280 | ~1.8 [16] [19] | Indicates protein or phenol contamination. A ratio ≤1.6 suggests significant contamination [18] [16]. | Proteins, Phenol [18] [19] |

| A260/A230 | 2.0 - 2.2 [16] [19] | A sensitive indicator of organic compound contamination. Values below the ideal range suggest the presence of salts or reagents [18]. | Chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine HCl), EDTA, carbohydrates, detergents (e.g., Triton X-100) [18] [16] |

- Critical Considerations:

- The pH and ionic strength of the solvent can affect A260/A280 values. Acidic solutions may under-represent the ratio by 0.2–0.3, while basic solutions may over-represent it [16] [19].

- The A260/230 ratio is particularly sensitive and can be unstable when DNA is eluted in a saline buffer, as salts absorb strongly at 230 nm [16].

DNA Integrity

DNA integrity refers to the degree of fragmentation of the DNA molecules. Intact, high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA is essential for applications like long-read sequencing.

- Assessment Methods:

- Gel Electrophoresis: The traditional method where genomic DNA appears as a tight, high-molecular-weight band. Degradation is visualized as a smear of lower molecular weight fragments [16] [20].

- Automated Electrophoresis: Systems like the Agilent TapeStation provide a standardized DNA Integrity Number (DIN), which is an objective score for qualifying DNA samples for NGS workflows. A higher DIN (scale of 1-10) indicates better integrity [21].

- Fluorometric Correlation: Similar results for DNA quantification by both spectrophotometry and fluorometry (PicoGreen assay) suggest high DNA integrity, as the PicoGreen measurement is strongly affected by fragmentation [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Quality Control

Protocol 1: Purity and Yield Measurement via Microvolume Spectrophotometry

This protocol, adapted from established nucleic acid purity measurement assays, details the use of a Nanodrop spectrophotometer for the analysis of microbial DNA samples [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Spectrophotometric Measurement

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Nanodrop 2000/8000 Spectrophotometer | Microvolume spectrophotometer for measuring sample absorbance using minimal volume (0.5–5.0 μL) [18]. |

| Nuclease-free Water | Used for blanking the instrument and cleaning pedestals. Serves as a zero-reference [18]. |

| Lint-free Lab Wipes | For cleaning the upper and lower measurement pedestals without introducing fibers or contaminants [18]. |

| Elution Buffer | The buffer used to dissolve the DNA during extraction. It is used as the blanking solution for accurate baseline measurement [18]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Initialization and Cleaning:

- Open the Nanodrop software and select the appropriate measurement type (e.g., "Nucleic Acid," then "dsDNA").

- Pipette 2 µL of nuclease-free water onto the lower measurement pedestal and lower the arm. After one minute, wipe both pedestals dry with a lint-free wipe [18].

Blank Measurement:

- Load 2 µL of the elution buffer (the blank) onto the pedestal and lower the arm. Click "Blank" to measure and store the reference spectrum.

- After measurement, clean both pedestals thoroughly.

- To verify the baseline, load another 2 µL of blank and click "Measure." The absorbance at 260 nm should not vary more than 0.04 from the baseline. If it does, repeat the cleaning and blanking process [18].

Sample Measurement:

- Enter the sample ID in the software.

- Pipette 2 µL of the microbial DNA sample onto the pedestal and lower the arm. Click "Measure."

- After the measurement, wipe the pedestals clean before proceeding to the next sample.

- Record the concentration (yield, in ng/µL), A260/A280, and A260/230 ratios for each sample [18].

Data Interpretation:

- Review the spectral overlay for abnormal patterns. A pure DNA sample typically shows a peak at 260 nm.

- Compare the recorded purity ratios against the ideal values in Table 1 to assess sample quality.

The following workflow summarizes the key steps for assessing microbial DNA quality:

Protocol 2: Integrity Analysis Using Automated Electrophoresis

For a more objective and quantitative assessment of DNA integrity, automated electrophoresis systems are recommended.

Research Reagent Solutions

- Agilent TapeStation System with Genomic DNA ScreenTape Assay: Provides automated electrophoretic separation, sizing, quantification, and integrity analysis via the DNA Integrity Number (DIN) [21].

- PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit: A fluorometric method that uses an intercalating dye for highly sensitive quantification of dsDNA; significant discrepancies with spectrophotometric concentration can indicate fragmentation or contamination [16].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample and Reagent Preparation:

- Follow the manufacturer's instructions for preparing the Genomic DNA ScreenTape assay reagents and samples. Typically, a small volume of DNA (e.g., 1 µL) is mixed with a specific loading buffer.

Instrument Operation:

- Load the prepared samples and the ScreenTape into the TapeStation instrument.

- Initiate the run through the controlling software. The system automatically performs electrophoresis, data capture, and analysis.

Data Analysis:

- The software generates an electrophoretogram and assigns a DIN score (1-10) to each sample.

- Interpreting DIN Scores: A high DIN (e.g., >7) indicates intact genomic DNA, ideal for long-read sequencing. A lower DIN suggests fragmentation, which is common in samples from challenging sources like formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) material but may still be suitable for certain NGS applications like amplicon sequencing [21].

- Visually inspect the electrophoretogram for a single, sharp high-molecular-weight band and the absence of a low-molecular-weight smear.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Equipment

The following table catalogs key solutions used in the protocols above and other relevant reagents for microbial DNA extraction and QC.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial DNA Extraction and Quality Control

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| MGIEasy Stool Microbiome DNA Extraction Kit II | Extracts microbial genomic DNA from complex samples like human stool, saliva, and swabs. Designed for low-bias extraction of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, and protozoa [22]. |

| Chelating Resin | A non-toxic, cost-effective resin used in DNA isolation methods. It purifies nucleic acids by binding metal ions and positively charged proteins [23]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease used to digest cellular proteins and facilitate cell lysis during DNA extraction, improving yield [23]. |

| Prelysis Bleaching (2.5% NaOCl) | A chemical treatment used to degrade external contaminants on insect or specimen bodies prior to DNA extraction, reducing environmental DNA contamination for microbiome studies [23]. |

| NIBSC WC-Gut RR (Whole Cell Reference Reagent) | A standardized whole cell reagent comprising 20 gut bacterial strains. Used to evaluate and benchmark the performance and bias of DNA extraction kits specific to gut microbiome research [20]. |

| Phenol-Chloroform | Used in purification to hydrolyze and remove proteins from the nucleic acid solution during extraction. Proteins collect at the interphase between the organic and aqueous phases [24]. |

The rigorous assessment of microbial DNA yield, purity, and integrity is a non-negotiable prerequisite for generating robust and reproducible data in genomics research. As demonstrated, a combination of spectrophotometric, fluorometric, and electrophoretic methods provides a comprehensive picture of DNA quality. Adopting standardized protocols and utilizing appropriate controls, such as whole cell reference reagents, allows researchers to accurately qualify their starting material, benchmark their methods, and confidently select samples fit for purpose. This disciplined approach to quality control is foundational to advancing research and development in microbiology and drug discovery.

The choice of starting material is a critical foundational step in microbial genomics that profoundly influences the success of all downstream molecular analyses. While fresh, pure cultures represent the gold standard for DNA extraction, research increasingly requires direct analysis of complex matrices such as clinical specimens, environmental samples, and preserved archives to understand microbial communities in their native contexts [10] [25]. This application note examines the technical challenges and methodological considerations for DNA extraction across this spectrum of starting materials, providing structured experimental data, optimized protocols, and decision frameworks to guide researchers and drug development professionals in their sample preparation strategies.

The fundamental challenge lies in the vastly different compositional characteristics of these materials. Fresh cultures of laboratory-adapted strains offer homogeneous cells with intact walls, suspended in a defined, contaminant-free medium. In contrast, complex samples like soil, feces, or clinical tissues contain diverse microbial populations with varying cell wall structures, embedded within matrices rich in inhibitors such as humic acids, polyphenols, polysaccharides, and proteins that can compromise DNA yield, purity, and representativeness [10] [26] [27]. Recognizing and methodologically addressing these differences is paramount for obtaining DNA that accurately represents the microbial community for subsequent applications including sequencing, PCR, and genotyping.

Comparative Performance of DNA Extraction Methods Across Sample Types

The efficacy of DNA extraction methods varies significantly depending on the starting material. Key performance metrics include DNA yield, purity, degree of shearing, and most critically, how well the extracted DNA represents the original microbial community structure without introducing bias.

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Extraction Method Performance Across Sample Types

| Extraction Method | Optimal Starting Material | DNA Yield | Community Representativeness | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform-Isoamyl Alcohol | Human microbiome mock community [10] | Highest (5.7-fold higher for some species) [10] | Moderate [10] | Use of hazardous organic solvents; more variable between experimenters [10] |

| Commercial Kit (Method 1 & 2) | Human microbiome mock community [10] | Moderate [10] | Good (Significantly better representation) [10] | Standardized protocols may not suit all sample types [10] |

| CTAB-Based Protocol | Plant materials (high polysaccharide/polyphenol content) [27] | High [27] | N/A (For single organisms) | Requires optimization for different plant orders [27] |

| Exogenous Plasmid Isolation | Broiler cecal samples (Complex microbiota) [25] | N/A (Functional capture) | Good for conjugative plasmids | Captures only mobile plasmids; relies on conjugation efficiency [25] |

| Magnetic Bead-Based (SafeCAP 2.0) | Plasma (Cell-free DNA) [28] | High (LoD: 0.3 pg/µL) [28] | N/A (For fragmented cfDNA) | Optimized for short, fragmented DNA [28] |

The selection of an extraction method inevitably introduces bias. For instance, a systematic evaluation of six DNA extraction methods for human microbiome studies found that the observed microbial community structure significantly differed from the expected composition regardless of the method used [10]. Some methods consistently over-represented certain species like L. iners DSMZ 13335, while others under-represented species like C. tuberculostearicum and P. acnes [10]. This underscores the critical importance of matching the extraction methodology not just to the sample type, but to the specific research question.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Diverse Sample Types

Modified CTAB Protocol for Complex Plant Materials

Principle: The CTAB (cetyl trimethylammonium bromide) method effectively separates DNA from polysaccharides and polyphenols that are abundant in plant seeds and crops, which can co-precipitate with DNA using standard protocols [27].

Reagents:

- 3× CTAB Extraction Buffer: 3% CTAB (w/v), 1.4 M NaCl, 0.8 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0)

- 0.3% 2-β-Mercaptoethanol (added fresh)

- Chloroform:Isoamyl alcohol (24:1 v/v)

- 6 M NaCl

- 3 M Potassium acetate

- Ice-cold 100% Isopropyl alcohol

- 70% Ethanol

- 1× TE buffer

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Grind 50 mg of plant sample in liquid nitrogen. Add 800 μL of pre-heated CTAB extraction buffer (65°C) containing 0.3% 2-β-mercaptoethanol. Incubate at 60-65°C for 1 hour, mixing by inversion every 20 minutes [27].

- Deproteinization: Add an equal volume of Chloroform:Isoamyl alcohol (24:1), mix by inversion, and centrifuge at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube. Repeat until the interface is clear [27].

- Precipitation: To the aqueous phase (~700 μL), add 350 μL of 6 M NaCl and 70 μL of 3 M potassium acetate. Simultaneously add 500 μL of ice-cold 100% isopropyl alcohol and invert gently until DNA threads form. Incubate at -20°C for 30 minutes [27].

- Wash and Resuspend: Centrifuge at 13,000 rpm for 5 minutes. Discard supernatant, wash the pellet with 500 μL of 70% ethanol, air-dry, and resuspend in 50 μL of TE buffer. Incubate at 50°C for 1-2 hours to ensure complete resuspension [27].

Validation: The isolated DNA should be suitable for PCR amplification (e.g., with RAPD primers) and complete digestion with restriction enzymes like HindIII, confirming its quality for downstream molecular applications [27].

Protocol for Plasmid DNA Extraction from Complex Microbiomes

Principle: Exogenous plasmid isolation captures mobile genetic elements directly from complex samples through conjugation, enabling the study of antibiotic resistance gene transfer in a One Health context [25].

Reagents:

- Broiler cecal samples (lyophilized)

- Non-selective Muller-Hinton agar

- Muller-Hinton broth

- Recipient bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli)

- Antibiotics for selection

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Resuspend 0.01 g of lyophilized cecal sample in 0.85% NaCl [25].

- Exogenous Mating: Mix the sample suspension with a recipient bacterium (e.g., E. coli). This can be performed on a filter placed on non-selective agar or in a liquid medium to allow conjugative plasmid transfer [25].

- Selection: After a suitable mating period, plate the mixture on selective media containing antibiotics to select for transconjugants that have received resistance plasmids [25].

- Plasmid Analysis: Isect plasmids from transconjugants using a commercial plasmid miniprep kit. Analyze plasmids through restriction digestion and electrophoresis to profile the captured resistance plasmids [25].

Advantages and Limitations: This method functionally captures conjugative plasmids that are mobile within the complex microbial community, providing insight into transferable antibiotic resistance. However, it may miss non-conjugative plasmids and those that cannot be maintained in the recipient host [25].

Optimized Protocol for Degraded Archival Clinical Samples

Principle: Adapting ancient DNA techniques enables the recovery of genetic material from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples where DNA is highly fragmented and cross-linked [29].

Reagents:

- FFPE tissue sections

- Xylene or other deparaffinization agents

- Proteinase K

- Optimized lysis buffer

- Magnetic bead-based purification system

- Reagents for short-fragment library preparation

Procedure:

- Deparaffinization: Remove paraffin wax with xylene followed by ethanol washes to rehydrate the tissue [29].

- Lysis and Digestion: Incubate tissues in a lysis buffer containing high concentrations of proteinase K to reverse formaldehyde cross-links and digest proteins. This may require extended incubation times (up to 24-48 hours) [29].

- DNA Purification: Use magnetic bead-based clean-up systems specifically designed for short fragments. Avoid size selection steps that might discard the target degraded DNA [29].

- Library Preparation: Employ library preparation protocols that preserve and repair ultra-short DNA fragments, including modified end-repair and adapter ligation chemistries that accommodate damaged ends [29].

Downstream Analysis: Sequence the resulting libraries and analyze with a bioinformatics pipeline designed for ancient/damaged DNA, which can accurately align fragmented sequences and account for damage patterns like cytosine deamination [29].

Workflow Visualization and Decision Framework

The selection of an appropriate DNA extraction strategy depends on the starting material and research objectives. The following workflow provides a systematic decision path for method selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful DNA extraction from challenging samples requires specific reagents tailored to overcome particular obstacles. The following table details key solutions for different sample types.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Extraction from Diverse Sample Types

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB (Cetyl Trimethylammonium Bromide) | Precipitates DNA while leaving polysaccharides in solution; disrupts cell membranes [27]. | Plant materials rich in polysaccharides and polyphenols [27]. |

| 2-β-Mercaptoethanol | Powerful reducing agent that denatures proteins and inhibits polyphenol oxidation by neutralizing tannins [27]. | Plant and environmental samples with high phenolic content [27]. |

| Magnetic Beads (Functionalized) | Solid-phase support for DNA binding under high-salt conditions; enables efficient washing and elution [28] [30]. | Cell-free DNA extraction, automated workflows; ideal for short, fragmented DNA [28]. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease that digests histones and other cellular proteins; crucial for reversing cross-links [29]. | Archival FFPE tissues and samples with hard-to-lyse organisms [2] [29]. |

| Guanidine Hydrochloride/Salt | Powerful chaotropic agent that denatures proteins, inhibits nucleases, and promotes DNA binding to silica/magnetic beads [28]. | Lysis and binding buffer component for most commercial kits; critical for cfDNA isolation [28]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Precipitant for large DNA molecules and plasmids; used in differential precipitation to separate plasmid from genomic DNA [25]. | Plasmid isolation from complex samples; concentration of large nucleic acids [25]. |

The impact of starting material on DNA extraction success cannot be overstated. While fresh cultures allow for standardized, high-yield DNA isolation, the future of microbial research lies in navigating the complexity of direct clinical and environmental samples. The methodologies detailed herein—from the CTAB protocol for inhibitor-rich plants to exogenous isolation for mobile plasmids and ancient DNA techniques for archival tissues—provide a toolkit for researchers to overcome these challenges. The consistent themes across all protocols are the need for method validation and the recognition that no single method is universally optimal. The choice of extraction strategy must be guided by the sample matrix, the target nucleic acid, and the specific downstream analytical applications. By applying these principles and protocols, researchers can generate more reliable, representative genomic data, advancing our understanding of microbial communities in health, disease, and the environment.

Optimized DNA Extraction Protocols for Diverse Microbial Samples

Sample preparation is a critical upstream step in molecular analytical workflows for microbial research, directly impacting the quality and reliability of downstream results such as PCR, sequencing, and cloning [31]. The choice of DNA extraction method can influence DNA yield, purity, process time, and suitability for automation. Among the available solid-phase extraction techniques, silica-based methods dominate modern laboratories, primarily implemented through two key technologies: spin columns and magnetic beads. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these two chemistries, supported by quantitative data and standardized protocols, to guide researchers in selecting the optimal method for their specific microbial DNA extraction needs.

Principles of Silica-Based DNA Binding

Both column-based and magnetic bead-based methods operate on the same fundamental principle: the selective binding of negatively charged DNA molecules to a silica surface in the presence of a chaotropic salt-based binding buffer [32] [31]. These high-salt conditions disrupt the hydrogen-bonding network of water molecules, allowing nucleic acids to bind preferentially to the silica matrix while proteins and other contaminants remain in solution. The bound DNA is subsequently washed to remove residual impurities, followed by elution in a low-salt buffer or water, which rehydrates the nucleic acids and releases them from the silica surface [33].

Technology Comparison: Performance and Applications

Direct Performance Metrics

Recent studies provide quantitative comparisons between magnetic bead and spin column-based extraction methods across critical performance parameters.

Table 1: Direct Performance Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods

| Performance Parameter | Magnetic Bead Method | Spin Column Method | Reference/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Yield | 94–96% recovery [34] | 70–85% recovery [34] | PCR cleanup protocols |

| Typical Extraction Time | 6–7 minutes (SHIFT-SP method) [31] | ~25 minutes [31] | Optimized silica-based protocols |

| Sensitivity in Clinical Samples | 29-fold more satDNA detected at 100 Par. Eq./mL [35] | Baseline detection | Chagas disease diagnosis (qPCR) |

| Purity (A260/280) | 1.88 ± 0.02 [35] | 1.69 ± 0.03 [35] | Blood samples spiked with T. cruzi |

| Processed Sample Volume | High (easily scalable) [32] | Limited by column size [36] | General workflow suitability |

| Automation Compatibility | Excellent (96-well & automation) [34] | Poor (manual only) [34] | Throughput requirements |

Method Selection Guide

The optimal choice between magnetic bead and spin column methods depends heavily on the specific application requirements and laboratory context.

Table 2: Method Selection Guide Based on Application Needs

| Application Requirement | Recommended Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening | Magnetic Beads | Superior automation compatibility; processes 96 samples simultaneously [36] [34] |

| Low Parasitemia/Precision Dx | Magnetic Beads | Higher sensitivity and better recovery from low-DNA samples [32] [35] |

| Challenging Sample Types | Magnetic Beads | More effective with inhibitors; efficient extraction from soil, feces, sputum [37] [38] |

| Limited Budget/Small Scale | Spin Columns | Lower initial equipment cost; minimal investment [32] [33] |

| Rapid, Manual Processing | Spin Columns | Simpler workflow for small batches; no specialized equipment [32] |

| Minimal Laboratory Space | Spin Columns | Requires only a centrifuge; no magnetic separator needed [33] |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Magnetic Bead-Based DNA Extraction

The following optimized protocol is adapted from the high-yield SHIFT-SP (Silica bead-based HIgh yield Fast Tip-based Sample Prep) method [31].

Reagents and Equipment

- Lysis Binding Buffer (LBB): Contains guanidinium thiocyanate (GTC); adjust to pH 4.1 for optimal binding [31]

- Magnetic Silica Beads: 20-30μL per sample [31]

- Wash Buffer: Typically ethanol-based (e.g., 80% ethanol) [34]

- Elution Buffer: TE buffer or nuclease-free water [33]

- Equipment: Magnetic separator, heating block (62°C), pipettes

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Lysis:

- Mix 200μL sample with 200μL Lysis Binding Buffer.

- Incubate at 70°C for 10 minutes for efficient lysis [38].

Nucleic Acid Binding:

Magnetic Separation and Washing:

- Place tube on magnetic stand for ~2 minutes until beads form a pellet.

- Carefully remove and discard supernatant while retaining bead pellet.

- Wash twice with 500μL of 80% ethanol, fully removing supernatant between washes [34].

- Air-dry beads for 3-5 minutes. Avoid over-drying to maintain elution efficiency [34].

Elution:

- Resuspend beads in 20-50μL elution buffer (TE or nuclease-free water).

- Incubate at 62°C for 1 minute to maximize DNA release [31].

- Place tube on magnetic stand and transfer purified DNA supernatant to a clean tube.

Detailed Protocol: Spin Column-Based DNA Extraction

This general protocol is representative of commercial spin column kits, with specific notes from optimized workflows [33].

Reagents and Equipment

- Lysis Buffer: Contains chaotropic salts, Triton X-100; may include Proteinase K [33]

- Binding/Wash Buffer: Ethanol or isopropanol-based [33]

- Elution Buffer: TE buffer (pH 9.0) or nuclease-free water [33]

- Equipment: Microcentrifuge, spin columns with silica membrane, collection tubes

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Lysis:

- Add 200μL sample to 200μL lysis buffer and 20μL Proteinase K.

- Mix by vortexing and incubate at 56°C for 10-15 minutes [33].

Binding to Silica Membrane:

- Add 200μL ethanol or isopropanol to the lysate and mix by vortexing.

- Transfer entire mixture to spin column seated in collection tube.

- Centrifuge at ≥10,000×g for 1 minute. Discard flow-through [33].

Washing:

Elution:

- Place spin column in clean 1.5mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 50-100μL elution buffer (preheated to 62°C) directly to the center of silica membrane.

- Incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes.

- Centrifuge at full speed for 2 minutes to collect purified DNA [33].

Workflow Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for DNA Extraction Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Method Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts(e.g., Guanidinium thiocyanate) | Denature proteins, facilitate DNA binding to silica | Both methods; key component of lysis/binding buffers [31] [37] |

| Magnetic Silica Beads | Solid phase for DNA binding with superparamagnetic properties | Magnetic bead method only [39] [31] |

| Silica Membrane Columns | Solid phase for DNA binding in column format | Spin column method only [32] [33] |

| Proteinase K | Digest proteins and degrade nucleases | Both methods; added during lysis step [33] |

| Wash Buffers(typically ethanol-based) | Remove contaminants while retaining bound DNA | Both methods; often contain ethanol or isopropanol [34] [33] |

| Elution Buffers(TE buffer or nuclease-free water) | Release purified DNA from silica matrix | Both methods; low salt enables DNA rehydration [33] |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reduce disulfide bonds in complex samples | Challenging samples (e.g., sputum); helps break down mucoproteins [37] |

Both magnetic bead and spin column technologies provide effective pathways for microbial DNA extraction through silica-based chemistry. Magnetic bead methods offer significant advantages in throughput, automation compatibility, and sensitivity for challenging applications such as low parasitemia detection in Chagas disease or pathogen identification in complex environmental samples. Spin columns remain a valuable option for smaller-scale research settings where budget constraints or equipment availability are primary considerations. The decision between these methodologies should be guided by specific application requirements, including sample volume, required throughput, sensitivity demands, and available laboratory resources. By understanding the comparative strengths and limitations of each approach, researchers can implement optimized DNA extraction strategies that support robust and reproducible molecular analysis in microbial research and diagnostic applications.

Within microbial DNA extraction research, the paradigm that a single methodological approach can be universally applied has been fundamentally overturned. The critical importance of sample-specific protocols is now firmly established, as the unique biochemical composition of each sample type presents distinct challenges that directly impact DNA yield, purity, and downstream analytical success. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for optimizing microbial DNA extraction across five fundamental sample categories: blood, stool, urine, swabs, and cell cultures. By synthesizing current methodological research and quantitative performance data, we aim to equip researchers with detailed protocols that enhance reproducibility, minimize bias, and ensure the reliability of results in diagnostic development and microbiome studies.

Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Sample Types

The selection of an appropriate DNA extraction method requires careful consideration of performance metrics across different sample types. The following table summarizes key quantitative data from comparative studies, providing a basis for evidence-based protocol selection.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of DNA Extraction Methods Across Different Sample Types

| Sample Type | Extraction Method | DNA Yield | Purity (A260/A280) | Key Performance Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine | Standard Protocol (SP) | 175.73 ± 331.75 ng/µL | 1.28 ± 0.54 | High yield but variable; better for low-abundance taxa | [40] |

| Urine | Water Dilution Protocol (WDP) | 78.34 ± 173.95 ng/µL | 1.53 ± 0.32 | Superior purity, reduced contamination | [40] |

| Urine | Chelation-Assisted (CAP) | 62.89 ± 145.85 ng/µL | 1.37 ± 0.53 | Poor performance across all metrics | [40] |

| Vaginal Swabs | Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue | Highest Yield | 1.72 - 2.35 | Highest DNA yield and quality (GQS 4.24) | [14] |

| Vaginal Swabs | MoBio PowerSoil Standard | Lower Yield | N/S | Significantly higher alpha diversity | [14] |

| Skin/Wound Swabs | Improved Single-Swab (VLP) | 0.63 ng - 1.2 pg* | N/S | ~400-fold phage DNA enrichment; sufficient for library prep | [41] |

| Skin/Wound Swabs | Improved Single-Swab (Remainder) | 27 ng - 32 pg* | N/S | Adequate for 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomics | [41] |

*Yields from mock samples containing 1.9×10^8 to 1.9×10^5 virions. N/S: Not Specified.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Urine Sample Processing

The low bacterial biomass and presence of PCR inhibitors in urine make it one of the more challenging sample types for microbial DNA extraction. A recent methodological study compared three distinct protocols for processing urine samples prior to DNA extraction with the Quick-DNA Urine Kit [40].

Table 2: Protocol Comparison for Microbial DNA Extraction from Urine

| Protocol Step | Standard Protocol (SP) | Water Dilution Protocol (WDP) | Chelation-Assisted Protocol (CAP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume | 6 mL urine | 6 mL urine | 6 mL urine |

| Pre-Treatment | None | 4 mL UltraPure Distilled Water | 4 mL Tris-EDTA Buffer, pH 9.0 |

| Conditioning | Add Urine Conditioning Buffer | Add Urine Conditioning Buffer | Add Urine Conditioning Buffer |

| Centrifugation | Precipitate & pellet DNA | Precipitate & pellet DNA | Precipitate & pellet DNA |

| Lysis | Resuspend in Genomic Lysis Buffer + Proteinase K | Resuspend in Genomic Lysis Buffer + Proteinase K | Resuspend in Genomic Lysis Buffer + Proteinase K |

| Purification | Spin column binding & washing | Spin column binding & washing | Spin column binding & washing |

| Key Advantage | Higher DNA concentration, detects low-abundance taxa | Superior purity (260/280=1.53) and reduced contamination | Designed to dissolve urinary crystals (but performed poorly) |

Experimental Insights: The Water Dilution Protocol (WDP) is recommended for most urinary microbiome applications due to its significantly higher DNA purity (260/280 ratio of 1.53 vs. 1.28 for SP) and reduced contamination levels, despite yielding lower DNA concentrations [40]. WDP-extracted samples also showed significantly higher microbial abundance (p<0.0001), while SP demonstrated higher alpha diversity indices (p<0.01), likely due to improved detection of low-abundance taxa [40] [42]. Beta diversity analysis showed no significant compositional differences between SP and WDP (p=1.0), supporting WDP's reliability for microbiome research [40].

Swab Sample Processing

Swab samples, including vaginal, skin, and wound specimens, present challenges due to low microbial biomass. Different protocols yield varying results in terms of DNA quantity versus microbial diversity representation.

Vaginal Swab Protocol Comparison: A comparative study evaluated four extraction methods from self-collected vaginal swabs (Copan ESwab) [14]:

- Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue: Pellet resuspended in PBS with enzymatic lysis (Proteinase K, lysozyme, mutanolysin) at 37°C, followed by traditional phenol-chloroform extraction.

- MoBio PowerSoil with combined C2+C3: Pellet treated with a mixture of C2 and C3 solutions from the PowerSoil kit.

- MoBio PowerSoil with combined C1+C2+C3: Pellet treated with a mixture of C1, C2, and C3 solutions.

- MoBio PowerSoil Standard Protocol: Followed manufacturer's instructions without modifications.

Key Findings: The Qiagen DNeasy method produced the highest DNA yield and achieved the best Genomic Quality Score (4.24 ± 0.36). In contrast, the MoBio PowerSoil protocols, particularly the standard protocol, provided significantly higher alpha diversity estimates, despite lower DNA yields [14]. This highlights the critical trade-off between DNA quantity and diversity representation in low-biomass samples.

Integrated Swab Processing Workflow for Bacterial and Viral DNA: For skin and wound swabs where both bacterial and viral (phage) DNA are of interest, an improved single-swab method has been developed [41]. The following workflow diagram illustrates this integrated protocol:

This integrated method demonstrates substantial improvement for wound samples, increasing the success rate from 25% with traditional methods to 100% of samples yielding sufficient DNA for downstream analysis [41]. The VLP fraction shows approximately 400-fold enrichment of phage DNA compared to cellular DNA, while the remainder fraction provides adequate bacterial DNA for 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomic analysis [41].

Stool Sample Processing

Stool samples contain complex microbial communities but also include numerous PCR inhibitors that must be removed for reliable downstream analysis.

Key Considerations:

- Inhibitor Removal: Stool samples contain bile salts, complex carbohydrates, and humic substances that inhibit downstream PCR. Kits with patented Inhibitor Removal Technology (IRT) such as the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit or DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kits are specifically designed to address this challenge [43].

- Sample Input Flexibility: When using stabilization media, researchers may observe lower DNA yields compared to raw stool. Protocol flexibility should be maintained to adjust input volumes to meet the yield requirements of downstream assays [7].

- Mechanical Lysis: Robust bead beating is essential for breaking down tough Gram-positive bacterial cell walls and fungal cells present in stool samples. The DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit is validated for efficient lysis of both bacteria and fungi [43].

Minimum DNA Input Requirements: For 16S rRNA sequencing, a minimum DNA concentration above 4 × 10^(-2) ng/µL is recommended, with ideal inputs being >2 × 10^(-1) ng/µL. Input levels of ≤1.6 × 10^(-3) ng/µL are not recommended as they introduce taxonomic biases and misrepresent the microbiome [43].

Blood Sample Processing

Blood samples present unique challenges for microbial DNA extraction due to the high ratio of human to microbial DNA and the presence of PCR inhibitors like heme.

Critical Requirements:

- Human DNA Depletion: Effective separation of microbial DNA from abundant human DNA is crucial for sensitivity. Low- and high-molecular-weight substances inhibitory to PCR must be removed [44].

- Comprehensive Lysis Capability: The method must be capable of lysing Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, and fungal organisms that may cause bloodstream infections [44].

- Contamination Control: Extraction buffers, reagents, and consumables must be free of microbial DNA to avoid false-positive results. Some commercial kits have been reported to contain contaminating bacterial DNA [44].

Protocol Recommendations: For manual extraction from small-volume blood samples, methods utilizing guanidium thiocyanate and silicon dioxide-based binding matrices have proven effective. These protocols typically involve:

- Initial centrifugation to concentrate microbial cells

- Chemical and enzymatic lysis to break diverse cell walls

- Selective binding of DNA to silica matrices in the presence of chaotropic salts

- Extensive washing to remove PCR inhibitors

- Elution in low-salt buffers or molecular-grade water

Cell Culture Processing

Microbial DNA extraction from cell cultures requires careful attention to culture conditions and processing parameters to ensure high-quality DNA.

Key Protocol Elements:

- Culture Monitoring: Track cell viability, concentration, and maintain optimal density throughout expansion. Tools like automated cell counters provide reliable monitoring for consistent DNA isolation [7].

- Specialized Reagents: For specific cell types such as T cells, use specialized media and activation reagents to maintain cell health and maximize DNA yield [7].

- Lysis Optimization: Implement forceful but focused lysis through heat and mixing to break open cells without damaging DNA. Magnetic bead workflows can increase sample throughput and uniformity [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Microbial DNA Extraction Across Sample Types

| Reagent/Category | Function | Sample Type Applications | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guanidium Thiocyanate | Chaotropic salt; denatures proteins, enables DNA binding to silica | Universal | Foundation of many lysis buffers; used in PureLink and Boom methods [45] [46] |

| Silica-Based Matrices | Selective DNA binding in presence of chaotropic salts | Universal | Spin columns, magnetic beads, or homemade preparations with celite [45] [46] |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease; digests proteins | Tissue, cells, stool | Critical for tough samples; used with SDS for effective lysis [46] |

| Inhibitor Removal Technology (IRT) | Selective removal of PCR inhibitors | Stool, soil, blood | Patented technology in QIAGEN Power kits; removes humic acids, bile pigments [43] |

| DNase I | Digests free DNA outside of intact capsids | VLP purification from swabs | Essential for viral enrichment protocols; degrades bacterial and host DNA [41] |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) | Precipitates polysaccharides and proteins | Plant, stool, soil | Used in phenol-chloroform extractions to remove contaminants [41] |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) | Chelating agent; binds metal ions | Urine, tissue | Inhibits DNases, dissolves urinary crystals [40] |

| RNase A | Degrades RNA contamination | High-RNA samples (tissues) | Optional step to prevent RNA contamination in DNA extracts [46] |

The optimization of sample-type specific protocols for microbial DNA extraction represents a fundamental requirement in modern molecular research. As demonstrated by the comparative data and methodologies presented herein, the strategic selection and refinement of extraction protocols directly impacts the reliability and interpretability of downstream analyses. Researchers must consider the inherent characteristics of each sample matrix—whether the low biomass of urine, the inhibitor-rich environment of stool, the complex community of swabs, or the high human DNA background in blood—when designing their experimental workflows. By implementing these detailed protocols and leveraging the appropriate reagent systems, scientists can significantly enhance the quality of their microbial DNA extraction, thereby strengthening the foundation of their research in microbiome analysis, diagnostic development, and therapeutic discovery.

The efficacy of microbial DNA extraction is fundamentally governed by the initial cell lysis step, a process entirely dependent on the intricate structural properties of microbial cell walls. In the context of sample preparation for microbial DNA extraction research, a one-size-fits-all approach to lysis introduces significant bias, systematically favoring certain microbes over others and distorting the true representation of a microbial community [47]. This application note provides a detailed guide to tailoring lysis strategies to effectively and equitably handle the diverse challenges presented by Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, and fungi. The structural basis for these differences is paramount: Gram-positive bacteria possess a thick, multi-layered peptidoglycan wall; Gram-negative bacteria feature a thin peptidoglycan layer enclosed within a complex outer membrane rich in lipopolysaccharides; and fungi have robust cell walls primarily composed of chitin [48] [49]. Understanding these differences is the first step in developing an unbiased lysis protocol.

Structural Basis for Differential Lysis

The need for tailored lysis protocols stems from the profound structural differences between the major groups of microorganisms. The following table summarizes the key compositional differences that dictate their susceptibility to various lysis methods.

Table 1: Key Cell Wall Characteristics Influencing Lysis Efficiency

| Characteristic | Gram-Positive Bacteria | Gram-Negative Bacteria | Fungi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptidoglycan Layer | Thick, multilayered [48] | Thin, single-layered [48] | Absent |

| Outer Membrane | Absent [48] | Present (with LPS) [48] | Absent |

| Primary Structural Polymer(s) | Peptidoglycan, Teichoic acids [48] | Peptidoglycan, Lipopolysaccharide [48] | Chitin, Glucans [49] |

| Resistance to Physical Disruption | High [48] | Low [48] | Very High [49] |

| Susceptibility to Chemical/Enzymatic Lysis | Moderate (lysozyme-sensitive) [50] | High (lysozyme-sensitive, membrane disruptors) [50] | Low (requires specific hydrolases) [49] |

These structural profiles directly translate into varying levels of resistance, necessitating a strategic approach to cell disruption. The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting an appropriate lysis strategy based on the target microorganisms and research objectives.

Diagram 1: Lysis Strategy Selection Workflow

Comparative Analysis of Lysis Methods

No single lysis method is universally superior; each has advantages and drawbacks that make it suitable for specific applications. The choice of method can dramatically impact DNA yield, community representation, and downstream analysis.

Table 2: Advantages and Drawbacks of Primary Lysis Methods

| Lysis Method | Key Advantages | Key Drawbacks | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical (Bead Beating) | Most effective for tough cells (Gram-positives, fungi, spores); Fast; Broadly unbiased for complex communities [51] [47]. | Can shear DNA, reducing fragment size; Generates heat [47]. | Metagenomic DNA extraction from complex, diverse samples (e.g., soil, gut microbiota) [51]. |

| Chemical & Enzymatic | Gentle on DNA; Highly customizable with enzymes (lysozyme, proteinase K) and detergents [47] [52]. | Can be slow; No universal cocktail; May fail on robust cells; Chemical incompatibilities (e.g., EDTA vs. metal-dependent enzymes) [47]. | Extraction of high-molecular-weight DNA or lysis of specific, known fragile targets (e.g., pure culture of Gram-negatives) [52]. |

| Thermal | Simple, inexpensive, and low hands-on time [47]. | Highly biased; Kills but may not lyse tough cells; High DNA degradation risk [47]. | Quick lysis of fragile Gram-negative bacteria where DNA quality and completeness are not critical. |

| Ionic Liquid-Based | Rapid (minutes); Effective on both Gram-types; Low-cost; avoids hazardous chemicals [53]. | Emerging method; Requires optimization for new sample types; Potential PCR inhibition if not diluted [53]. | Rapid, high-throughput preparation of bacterial samples for diagnostics. |

The superiority of a combined mechanical and chemical lysis (CML) approach over chemical lysis (CL) alone for complex samples has been demonstrated quantitatively. In a recent 2025 study on respiratory microbiome analysis, CML significantly outperformed CL, yielding higher-quality data and better detection of robust microorganisms [51].

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Lysis Methods in Respiratory Microbiome Analysis

| Performance Metric | Chemical Lysis (CL) Only | Combined Mechanical & Chemical Lysis (CML) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|