Method Verification in Microbiology Labs: When and How to Ensure Regulatory Compliance

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical requirements for method verification in microbiology laboratories.

Method Verification in Microbiology Labs: When and How to Ensure Regulatory Compliance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical requirements for method verification in microbiology laboratories. It clarifies the foundational distinction between method validation and verification, detailing specific scenarios—such as implementing a new FDA-cleared test, testing new sample matrices, or meeting CLIA, ISO 15189, and cGMP standards—that mandate verification. The content offers a methodological framework for planning and executing verification studies, including key performance parameters like accuracy, precision, and reportable range. It further addresses troubleshooting common pitfalls, optimizing ongoing quality control, and understanding when full validation is necessary, empowering professionals to build robust, reliable, and compliant laboratory testing processes.

Verification vs. Validation: Defining the Foundation of Reliable Microbiology Testing

In the regulated environment of a microbiology laboratory, the terms "verification" and "validation" represent distinct but complementary processes essential for ensuring the reliability and accuracy of test methods. Understanding this distinction is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental requirement for compliance with regulatory standards and for ensuring patient safety [1]. Within the context of microbiology research and drug development, these processes confirm that laboratory methods are fit for their intended purpose, whether for diagnosing infectious diseases, testing pharmaceutical products for microbial contamination, or characterizing complex microbial communities [2] [3].

This guide provides a detailed framework for differentiating method verification from validation, with a specific focus on the circumstances that necessitate verification within microbiology laboratory research. The clarification of these concepts is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who must navigate the stringent requirements of regulatory bodies such as the FDA, CLIA, and international pharmacopeias [2] [1].

Core Definitions and Regulatory Context

Defining Verification and Validation

In laboratory practice, "verification" and "validation" are often used interchangeably, but they describe fundamentally different processes based on the origin and regulatory status of the method in question.

Verification is a process performed for unmodified, FDA-approved or cleared tests. It is a one-time study that demonstrates a test performs in line with the manufacturer's established performance characteristics when used as intended in the operator's specific environment [2]. In the pharmaceutical industry, method verification is defined as the ability to verify that a method can perform reliably and precisely for its intended purpose, often applied to compendial methods like USP chapters <61>, <62>, and <71> [1].

Validation, in contrast, establishes that an assay works as intended for non-FDA cleared tests. This applies to laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) and modified FDA-approved tests. Modifications can include using different specimen types, sample dilutions, or test parameters such as changing incubation times, any of which could affect the assay's performance and thus require full validation [2]. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Chapter <1225> defines validation as "a process by which it is established, through laboratory studies, that the performance characteristics of a method meet the requirements for its intended analytical applications" [1].

Regulatory Requirements and Guidance

Method verification is required by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) for all non-waived systems (tests of moderate or high complexity) before reporting patient results [2]. Regulatory agencies, including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Medicine and Healthcare Regulatory Agency (MHRA), and ICH, require these processes to ensure patient safety and result reliability [1].

Table 1: Regulatory Guidance Documents for Verification and Validation

| Document | Focus Area | Application |

|---|---|---|

| CLIA (42 CFR 493.1253) | Laboratory testing | Verification of non-waived systems [2] |

| USP <1225> | Compendial procedures | Validation of compendial procedures [1] |

| USP <1226> | Compendial procedures | Verification of compendial procedures [1] |

| USP <1223> | Microbiological methods | Validation of alternative microbiological methods [1] |

| ICH Q2(R2) | Analytical procedures | Validation of analytical methods [1] |

| EU 5.1.6 | Microbiological quality | Alternative methods for control of microbiological quality [1] |

When is Method Verification Required in Microbiology?

Method verification is a mandatory process in specific scenarios within the microbiology laboratory. The requirement is triggered by the introduction of a new test system or significant changes to existing systems.

Primary Scenarios Requiring Verification

Implementation of a New Unmodified FDA-Cleared Test: Before any patient results are reported, the laboratory must verify that the test performs as claimed by the manufacturer in their specific environment [2]. This is the most common scenario for verification in clinical microbiology laboratories.

Major Changes in Procedures or Instrument Relocation: Verification is required when there are significant changes to the testing environment or methodology that could impact performance, such as moving an instrument to a new location or making substantial changes to the testing process not classified as a modification requiring full validation [2].

The Lifecycle Perspective

Method verification is not a "one-and-done" activity. A vigilant oversight approach throughout a product's lifecycle is necessary. Re-verification or validation may be required when changes occur, including [1]:

- Formulation or concentration updates

- Material source changes

- Manufacturing process updates

- Manufacturing location changes

- Reagent changes due to vendor changes or discontinuation

- Implementation of modern microbiological methods to replace traditional ones

Key Performance Characteristics for Verification

For an unmodified FDA-approved test, CLIA regulations require laboratories to verify specific performance characteristics. The exact approach depends on whether the assay is qualitative, quantitative, or semi-quantitative, with qualitative and semi-quantitative being more common in microbiology labs [2].

Table 2: Verification Criteria for Qualitative/Semi-Quantitative Microbiology Assays

| Performance Characteristic | Minimum Sample Requirement | Sample Types | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 20 clinically relevant isolates | Combination of positive and negative samples; can include standards, controls, reference materials, proficiency tests, or de-identified clinical samples [2] | (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100 [2] |

| Precision | 2 positive and 2 negative samples tested in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators | Controls or de-identified clinical samples [2] | (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100 [2] |

| Reportable Range | 3 samples | Known positives for qualitative assays; range of positives near upper and lower cutoff values for semi-quantitative assays [2] | Verify laboratory's established reportable result (e.g., Detected, Not detected) [2] |

| Reference Range | 20 isolates | De-identified clinical samples or reference samples known to be standard for the laboratory's patient population [2] | Verify expected result for a typical sample from the laboratory's patient population [2] |

The acceptance criteria for these performance characteristics should meet the stated claims of the manufacturer or what the CLIA director determines to be acceptable [2].

Experimental Design and Protocols for Verification

Creating a Verification Plan

A written verification plan, reviewed and signed off by the laboratory director, is essential before commencing the study. This plan should include [2]:

- Type of verification and purpose of the study

- Purpose of the test and method description

- Detailed study design including:

- Number and type(s) of samples

- Type of quality assurance and quality controls

- Number of replicates, days, and analysts

- Performance characteristics evaluated and acceptance criteria

- Materials, equipment, and resources needed

- Safety considerations

- Expected timeline for completion

Method-Specific Considerations

Microbiological methods present unique challenges for verification studies. For example, with antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods, knowing what organisms to use, how to interpret results, and what to consider when using non-FDA breakpoints with an FDA-cleared AST panel is not clearly defined [2]. This highlights the importance of leveraging resources such as clinical microbiologists and laboratory leaders who are specifically trained to oversee this process.

In microbiome research, methodological variations such as the choice of 16S rRNA hypervariable region for amplification, sequencing platform technology, and geographic location of sample sources can significantly impact results [3]. These factors must be considered when designing verification studies for microbiome methods.

Statistical Approaches for Verification Studies

Selecting appropriate statistical methods is crucial for accurate verification. Recent comparative studies have shown that simplified algebraic methods for estimating variability, while easy to use, can overestimate the contribution of between-strain and within-strain variability due to the propagation of experimental variability in nested experimental designs [4]. Mixed-effect models and multilevel Bayesian models provide more unbiased estimates for all levels of variability, though they come with higher complexity [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful verification studies require carefully selected materials and reagents. The following table outlines essential components for microbiology method verification studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microbiology Verification

| Reagent/Material | Function in Verification | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Isolates | Serve as positive and negative controls for accuracy studies [2] | Verify detection of target microorganisms (e.g., MRSA, ESBL) |

| Reference Materials | Provide standardized samples with known characteristics [2] | ATCC strains for microbial identification verification |

| Proficiency Test Samples | External assessment of method performance [2] | CAP surveys for laboratory accreditation |

| De-identified Clinical Samples | Assess method performance with real patient specimens [2] | Verify recovery of pathogens from stool, respiratory, or blood samples |

| Quality Controls | Monitor precision and reproducibility [2] | Daily QC for automated identification and susceptibility systems |

| Culture Media | Support microbial growth for traditional methods [1] | Verification of media lots for growth promotion tests |

The distinction between verification and validation is fundamental to maintaining quality and compliance in microbiology laboratories. Verification is required when implementing unmodified FDA-cleared tests and ensures these tests perform as intended in your specific laboratory environment. Through careful planning, execution, and documentation of performance characteristics including accuracy, precision, reportable range, and reference range, laboratories can confidently implement methods that generate reliable results. As methodology in microbiology continues to evolve, with increasing implementation of modern molecular techniques and microbiome analyses, maintaining rigorous approaches to verification and validation becomes increasingly important for both patient safety and scientific progress.

In clinical microbiology and drug development, regulatory standards provide the essential framework for ensuring that diagnostic tests and products are safe, reliable, and effective. These regulations govern every stage of the testing lifecycle, from initial development and verification to ongoing clinical use. For researchers and scientists, understanding when method verification is required under these frameworks is fundamental to maintaining regulatory compliance and delivering high-quality patient care.

The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) establish quality standards for all laboratory testing in the United States, while ISO 15189 specifies requirements for quality and competence in medical laboratories globally. The In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR) creates a robust regulatory framework for in vitro diagnostic devices in the European Union, and Current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) regulations ensure the quality of pharmaceutical products in the US. Navigating this complex regulatory landscape requires a clear understanding of the specific requirements for test verification and validation under each framework, particularly for microbiology tests which present unique challenges due to the complexity of biological systems and the critical importance of accurate antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Core Regulatory Frameworks: Definitions and Applications

CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments)

CLIA establishes quality standards for all laboratory testing in the United States to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and timeliness of patient test results. CLIA regulations apply to laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) and require that laboratories establish and verify performance specifications for all tests [5]. CLIA categorizes tests based on complexity (waived, moderate, or high complexity) and specifies that method verification is required for any non-waived system before reporting patient results [6]. This includes any new assay or equipment and when there are major changes in procedures or instrument relocation.

ISO 15189

ISO 15189 is an international standard that specifies requirements for quality and competence in medical laboratories. The standard was recently updated in 2022 and includes specific requirements for the verification and validation of examination processes [7]. Laboratories complying with ISO 15189:2012 may find that they largely comply with Annex I of the IVDR, though manufacturing processes required under IVDR Annex I are not covered by ISO 15189 alone [8]. This standard is particularly important for laboratories operating in international contexts or those seeking to demonstrate the highest levels of quality.

IVDR (In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation)

IVDR (EU 2017/746) is the European regulation governing in vitro diagnostic medical devices, with the goal of improving clinical safety and creating fair market access [8]. IVDR introduced a risk-based classification system with four classes (A, B, C, D) and requires more rigorous clinical evidence for devices [9]. Under IVDR, performance evaluation is a continuous process throughout the device lifecycle and must demonstrate scientific validity, analytical performance, and clinical performance [9]. For in-house devices (also known as LDTs), IVDR Article 5.5 imposes specific constraints, including the requirement for appropriate quality management systems and justification for use over commercially available tests [8].

cGMP (Current Good Manufacturing Practice)

cGMP regulations, enforced by the FDA, contain minimum requirements for the methods, facilities, and controls used in manufacturing, processing, and packing of drug products [10]. These regulations ensure that a product is safe for use and that it has the ingredients and strength it claims to have. The CGMP regulations for drugs are primarily outlined in 21 CFR Parts 210 and 211 [10]. For pharmaceutical manufacturers, compliance with cGMP is essential for drug approval and marketing.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Regulatory Frameworks

| Framework | Jurisdiction/Scope | Primary Focus | Key Verification/Validation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLIA | United States; Clinical laboratory testing | Laboratory testing accuracy and reliability | Verification of accuracy, precision, reportable range, and reference range for non-waived tests [6] |

| ISO 15189 | International; Medical laboratories | Quality management and technical competence | Validation and verification procedures for examination processes [7] |

| IVDR | European Union; In vitro diagnostic devices | Device safety and performance throughout lifecycle | Performance evaluation including scientific validity, analytical performance, and clinical performance [9] |

| cGMP | United States; Drug manufacturing | Pharmaceutical product quality and consistency | Manufacturing process controls, quality standards, and documentation [10] |

When is Method Verification Required?

Method verification is a foundational requirement across regulatory frameworks to ensure tests perform as expected in your specific laboratory environment. The specific triggers for verification depend on the test type and regulatory context.

Verification vs. Validation: A Critical Distinction

Understanding the distinction between verification and validation is essential for proper regulatory compliance:

Verification is a one-time study for unmodified FDA-cleared or approved tests meant to demonstrate that a test performs in line with previously established performance characteristics when used as intended by the manufacturer [6]. It confirms that test performance specifications are met in the user's environment.

Validation is a more extensive process meant to establish that an assay works as intended. This applies to non-FDA cleared tests (e.g., laboratory-developed tests) and modified FDA-approved tests [6]. Validation is also an ongoing process to monitor and ensure that the test continues to perform as expected throughout its use [5].

Specific Triggers for Method Verification

Method verification is required in the following circumstances:

Implementation of new unmodified FDA-cleared tests: Before reporting patient results, laboratories must verify that the manufacturer's performance claims are met in their hands [6].

Major changes to existing procedures: This includes instrument relocation, significant reagent lot changes, or updates to software that could affect test performance [6].

For IVDR compliance: Verification is needed when implementing CE-marked in vitro diagnostic devices to ensure performance in your specific laboratory environment [7].

When modifying FDA-approved tests: Any changes to the assay not specified as acceptable by the manufacturer (e.g., different specimen types, sample dilutions, or test parameters) require validation before implementation [6].

For microbiology tests specifically, verification and validation procedures must be tailored to account for the complexity of biological systems, the diversity of microorganisms, and the critical importance of antimicrobial susceptibility testing [7] [6].

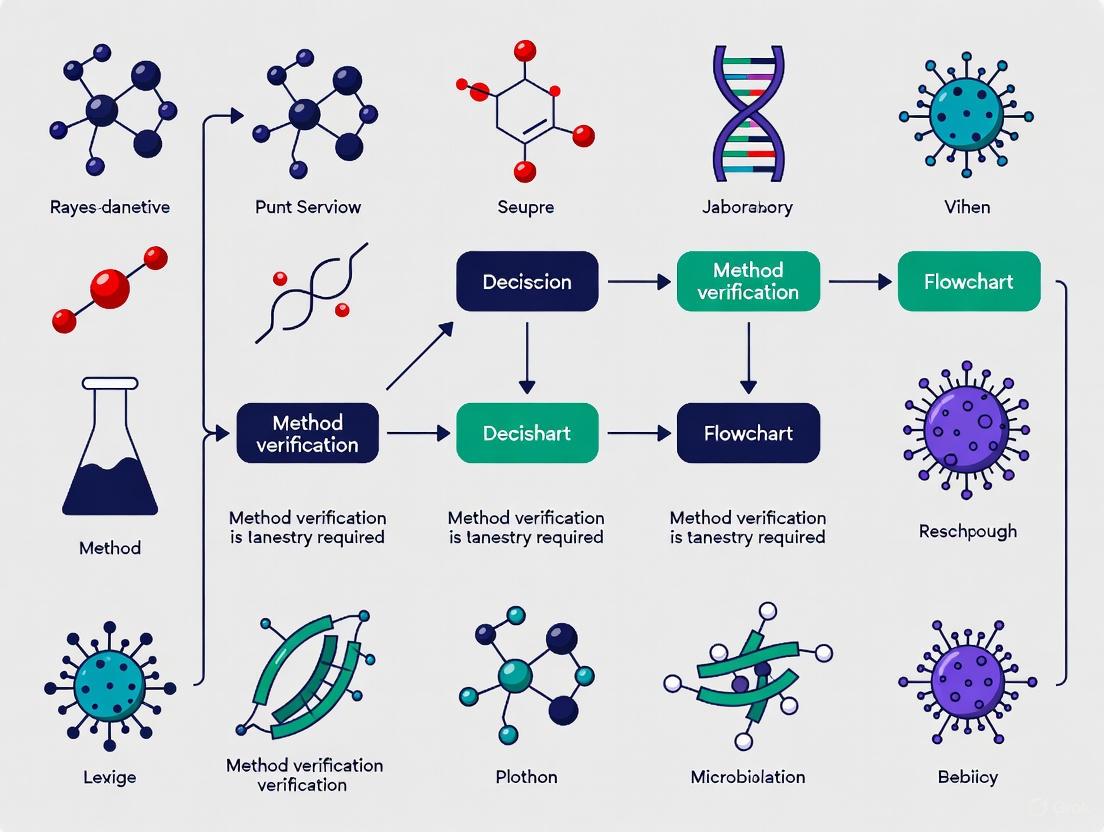

Diagram 1: Method Verification Decision Pathway

Experimental Design for Method Verification

Core Performance Characteristics

When designing a verification study for a clinical microbiology test, specific performance characteristics must be evaluated based on regulatory requirements. For qualitative and semi-quantitative assays commonly used in microbiology, the following criteria must be verified:

Accuracy: Confirm the acceptable agreement of results between the new method and a comparative method [6]. For qualitative assays, use a combination of positive and negative samples. A minimum of 20 clinically relevant isolates is recommended [6].

Precision: Confirm acceptable within-run, between-run and operator variance [6]. Test a minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative samples in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators. For fully automated systems, user variance assessment may not be needed [6].

Reportable Range: Confirm the acceptable upper and lower limit of the test system [6]. For qualitative assays, verify with known positive samples for the detected analyte. A minimum of 3 samples is recommended.

Reference Range: Confirm the normal result for the tested patient population [6]. Use a minimum of 20 isolates, including de-identified clinical samples or reference samples with results known to be standard for the laboratory's patient population.

Table 2: Verification Study Design Parameters for Microbiology Tests

| Performance Characteristic | Minimum Sample Size | Sample Types | Testing Protocol | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 20 clinically relevant isolates [6] | Combination of positive and negative samples; may include standards, controls, reference materials, proficiency tests, or de-identified clinical samples [6] | Comparison between new method and reference method | Percentage of agreement should meet manufacturer's stated claims or laboratory director's determination [6] |

| Precision | 2 positive and 2 negative samples [6] | Controls or de-identified clinical samples with high to low values for semi-quantitative assays [6] | Tested in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators [6] | Percentage of results in agreement should meet manufacturer's claims [6] |

| Reportable Range | 3 samples [6] | Known positive samples for qualitative assays; range of positive samples near cutoffs for semi-quantitative assays [6] | Testing samples that fall within the reportable range | Laboratory establishes reportable result parameters (e.g., "Detected", "Not detected") [6] |

| Reference Range | 20 isolates [6] | De-identified clinical samples or reference samples representative of laboratory's patient population [6] | Testing samples representative of laboratory's patient population | Expected result for a typical sample in laboratory's patient population [6] |

Creating a Verification Plan

A comprehensive verification plan should be documented and signed off by the laboratory director before commencing the study. This plan should include [6]:

- Type of verification and purpose of study: Clearly state whether the study is for verification or validation and the regulatory basis.

- Purpose of test and method description: Detail the intended use of the test and a complete description of the methodology.

- Study design specifics: Include the number and type of samples, quality assurance and quality control procedures, number of replicates, days of testing, number of analysts, and performance characteristics to be evaluated.

- Materials and equipment: List all required resources for the study.

- Safety considerations: Address any biosafety requirements for handling microbiology specimens.

- Timeline for completion: Establish realistic timeframes for completing the verification study.

Special Considerations for Microbiology Testing

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

Verification of antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods presents unique challenges due to the biological variability of microorganisms and the critical importance of accurate results for patient care. When verifying AST methods, particular attention should be paid to [7]:

- Selection of appropriate reference strains that represent the expected susceptibility profiles

- Inclusion of resistant, intermediate, and susceptible isolates to challenge the system

- Comparison with reference methods such as broth microdilution

- Careful interpretation of results when using non-FDA breakpoints with an FDA-cleared AST panel

Molecular Microbiology Assays

For molecular tests such as PCR-based methods, verification must include assessment of [5]:

- Analytical sensitivity (limit of detection) for each target

- Analytical specificity, including cross-reactivity with genetically similar organisms

- Inhibition controls and their effectiveness

- Specimen stability and nucleic acid extraction efficiency

Laboratory-Developed Tests (LDTs) and IVDR Compliance

For laboratories developing their own tests, the regulatory requirements are more extensive. Under IVDR, in-house devices must comply with specific requirements including [8]:

- The devices must not be transferred to another legal entity

- Implementation of appropriate quality management systems (e.g., ISO 15189)

- The product may not be made on an industrial scale

- Documentation justifying why an equivalent commercially available device is not used

The timeline for IVDR compliance for in-house devices is progressive, with full justification for use over commercially available tests required by May 2028 [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiology Verification Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Verification/Validation | Regulatory Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Strains | Provide quality control organisms with known characteristics for accuracy and precision studies [6] | Must be traceable to recognized collections (e.g., ATCC, NCTC) |

| Clinical Isolates | Challenge the test with real-world samples representing the laboratory's patient population [6] | Should be de-identified and used in accordance with ethical guidelines |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor assay performance during verification and ongoing quality assurance [5] | Should include positive, negative, and internal controls as appropriate |

| Analyte-Specific Reagents (ASRs) | Building blocks for laboratory-developed tests; primers, probes, antibodies [5] | FDA-defined category; laboratories using ASRs assume responsibility for test validation |

| Proficiency Testing Samples | Assess test performance through external quality assessment programs [5] | CLIA requires participation for regulated analyses |

| Reference Standards | Serve as comparator for method comparison studies [7] | Should represent the current gold standard or reference method |

The regulatory landscape encompassing CLIA, ISO 15189, IVDR, and cGMP presents a complex but essential framework for ensuring the quality and reliability of microbiology tests in both clinical and research settings. Method verification serves as a critical bridge between regulatory requirements and practical laboratory implementation, with specific triggers and protocols depending on the test type and regulatory jurisdiction.

As regulations continue to evolve, particularly with the full implementation of IVDR and updates to ISO standards, microbiology laboratories must maintain vigilant compliance with verification and validation requirements. By understanding the distinct requirements of each regulatory framework and implementing robust verification protocols, researchers and laboratory professionals can ensure the generation of reliable, reproducible data that advances both patient care and drug development.

In the regulated environment of a microbiology laboratory, method verification is not merely a best practice but a fundamental requirement to ensure the reliability, accuracy, and precision of test results. It serves as a critical demonstration that a laboratory can competently perform a previously validated method under its specific conditions, using its unique analysts and equipment. The triggers for method verification are bound by a complex framework of legal mandates, technical necessities, and regulatory expectations that vary across industries and jurisdictions. A failure to perform verification when required can have severe consequences, including regulatory citations, product recalls, and, most importantly, compromises to product safety and patient health. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the specific situations that legally and technically necessitate method verification, offering a structured framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to ensure compliance and uphold the highest standards of data integrity.

Distinguishing Between Verification and Validation

A foundational step in understanding the requirements is to clearly distinguish between method verification and method validation. These terms are often incorrectly used interchangeably, yet they describe two distinct processes with different objectives and regulatory implications.

Method Validation is the process of establishing, through extensive laboratory studies, that the performance characteristics of an analytical method are suitable for its intended analytical purpose. It is the initial demonstration that a method works. Validation is required for non-FDA cleared methods, such as laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) or modified FDA-approved methods [2]. The core parameters established during validation, as outlined in guidelines like ICH Q2(R2), include specificity, accuracy, precision, linearity, range, detection limit, and quantitation limit [11] [12].

Method Verification, in contrast, is the one-time study meant to demonstrate that a pre-validated or FDA-approved method performs in line with its previously established performance characteristics when it is introduced into a laboratory for the first time and used as intended by the manufacturer [2]. It is the process of confirming a method's performance in a user's hands.

The table below summarizes the key differences:

Table 1: Core Differences Between Method Validation and Verification

| Aspect | Method Validation | Method Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | To establish method performance characteristics for a new method [11]. | To confirm a laboratory can achieve the method's validated performance claims [2] [13]. |

| When Performed | For new, non-cleared, or significantly modified methods [2]. | When implementing a previously validated method in a new laboratory [13]. |

| Regulatory Focus | ICH Q2(R2), FDA for LDTs [11] [12]. | CLIA for clinical labs; FDA for compendial methods (e.g., USP) [2] [14] [11]. |

| Scope of Work | Extensive testing of all performance parameters [11]. | Limited testing of key parameters like accuracy and precision for the lab's specific use [2]. |

Legal and Regulatory Triggers for Method Verification

Legal and regulatory requirements are the most unambiguous triggers for method verification. Compliance is not optional, and these mandates are enforced through routine inspections by agencies such as the FDA, CMS, and accreditation bodies.

Implementing a New FDA-Cleared or Approved Method

In clinical diagnostics, the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) explicitly require that for any unmodified, FDA-cleared or approved test system of moderate or high complexity, the laboratory must perform method verification before reporting patient results [2]. This is a legal requirement under 42 CFR 493.1253. The verification must demonstrate that the test's performance specifications, as claimed by the manufacturer, can be met by the laboratory.

Using Compendial Methods for Pharmaceutical Products

For pharmaceutical quality control, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandates verification for compendial methods. As stated in the FDA guidance "Analytical Procedures and Methods Validation for Drugs and Biologics," a laboratory does not need to re-validate a method from an FDA-recognized source like the United States Pharmacopeia (USP). Instead, it must verify that the method is suitable for use under the actual conditions of use [14] [11]. Recent FDA inspections have shown a "hyper-focus" on this requirement, with inspectors specifically requesting product-specific reports proving that methods, including USP monographs, have been verified [14]. The verification must comply with general chapters such as USP <1226> "Verification of Compendial Procedures" [14].

Adhering to International Standards for Food and Feed Testing

For food and feed testing laboratories, the ISO 16140 series provides the standard for microbiological method validation and verification. According to ISO 16140-3, a laboratory must perform verification to demonstrate it can satisfactorily perform a method that has been validated through an interlaboratory study [13]. This process often involves two stages: implementation verification (proving the lab can perform the method correctly on a known item) and item verification (proving the method works for the specific food items tested by the lab) [13].

Technical and Operational Triggers for Method Verification

Beyond explicit regulatory mandates, several technical and operational changes within a laboratory trigger the need for verification to ensure ongoing data integrity.

Changes in Laboratory Infrastructure or Equipment

Significant changes to the laboratory environment that could affect analytical performance necessitate re-verification or partial verification. This includes:

- Introduction of new instrumentation of the same type and model. While a full IOPQ (Installation, Operational, and Performance Qualification) is required for equipment under cGMP [15], a method verification is still needed to confirm the method performs as expected on the new instrument.

- Relocation of the testing system to a new laboratory with different environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity).

- Changes to critical software or the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) that processes analytical data [15].

Changes in Reagents or Critical Materials

A change in the source of a critical reagent, such as culture media, antisera, or key biochemical substrates, requires verification to confirm that the new material produces results equivalent to those obtained with the original material. This ensures the method's specificity and accuracy are not compromised.

Changes in Analyst Personnel

While routine analyst training is part of quality control, a significant turnover in staff or the introduction of the method to a new group of analysts may trigger a limited verification to ensure that the new personnel can execute the method with the same level of precision and accuracy as demonstrated in the original verification study.

Experimental Protocols for Method Verification

The design of a verification study depends on whether the method is qualitative or quantitative. The following protocols, aligned with CLSI and ISO standards, provide a framework for a robust verification plan.

Verification of Qualitative Methods

Qualitative methods provide a binary result (e.g., detected/not detected, present/absent). The following table outlines the key performance characteristics to verify for a qualitative microbiological assay, such as a PCR test for a specific pathogen or a sterility test.

Table 2: Verification Protocol for Qualitative Microbiological Methods

| Performance Characteristic | Experimental Protocol & Minimum Sample Sizes | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Test a minimum of 20 clinically relevant isolates or samples with a combination of known positive and negative status [2]. Use reference materials, proficiency test samples, or de-identified clinical samples previously tested with a validated method. | The percentage of agreement should meet the manufacturer's stated claims or a lab-director-defined threshold (e.g., ≥95%) [2]. |

| Precision | Test a minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative samples in triplicate over 5 days by 2 different operators [2]. For fully automated systems, operator variance may not be needed. | Results should be 100% reproducible for each sample type, or meet a predefined percentage agreement. |

| Reportable Range | Verify using a minimum of 3 known positive samples for the detected analyte [2]. | The method should correctly identify all positive samples as "detected." |

| Reference Range | Verify using a minimum of 20 isolates or samples that represent the standard result for the laboratory's patient population (e.g., samples negative for the target organism) [2]. | The method should correctly identify all negative samples as "not detected." |

Verification of Quantitative Methods

Quantitative methods provide a numerical value (e.g., microbial colony counts, CFU/mL). The verification of a method like microbial enumeration (as per USP <61>) would focus on different parameters.

Table 3: Key Verification Parameters for Quantitative Microbiological Methods

| Performance Characteristic | Experimental Protocol | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Analyze a certified reference material (CRM) with a known microbial count. Compare the mean result from multiple replicates to the certified value. | Recovery should be within the certified range or meet predefined limits (e.g., 70-130%). |

| Precision | Perform multiple replicates (e.g., n=6) of the same sample in the same run (repeatability) and across different days/analysts (intermediate precision). | The relative standard deviation (RSD) should be within the manufacturer's claims or a predefined limit (e.g., <15-20% for HPLC, adapted for microbiology) [16]. |

| Linearity & Range | Test a dilution series of a microbial suspension across the claimed reportable range of the method. | The method's response should be linear across the range, with an R² value of >0.98, for example. |

| Specificity | Challenge the method with closely related species or strains to ensure it accurately quantifies the target microorganism without interference. | The method should correctly identify and quantify the target organism without significant interference. |

The Verification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of activities in a comprehensive method verification process, from planning to final implementation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

A successful verification study relies on high-quality, traceable materials. The following table details key reagent solutions and their critical functions in the verification process.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Method Verification

| Reagent / Material | Function in Verification |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Well-characterized microorganisms with defined profiles and known counts; used as the gold standard for establishing accuracy and precision [17]. |

| Quality Control Organisms | Used to monitor test validity, verify instrument performance, and serve as positive and negative controls during verification runs [17]. |

| Proficiency Test (PT) Samples | Blinded samples of known content provided by an external program; used to independently verify a laboratory's competency and the accuracy of its methods [17]. |

| In-House Isolates | Well-characterized strains isolated from the laboratory's own environment or historical samples; used to challenge the method's specificity and ensure it is relevant to the lab's specific testing needs [17]. |

| Standardized Culture Media | Verified for growth promotion properties using specific QC strains; ensures the medium supports the growth of target microorganisms, a critical factor in method accuracy [17]. |

Consequences of Non-Compliance

Failing to perform required method verification carries significant risks. Regulatory bodies like the FDA can issue Form 483 observations during inspections, demanding immediate corrective actions. For clinical laboratories, CMS can revoke CLIA certification, halting all patient testing [2]. Beyond compliance, the technical risks are profound: inaccurate test results can lead to flawed scientific conclusions, release of unsafe products, misdiagnosis of patients, and ultimately, harm to public health and the company's reputation [17]. The financial impact of investigating and correcting errors, repeating studies, and potential litigation can be substantial.

Method verification is a non-negotiable pillar of quality assurance in the microbiology laboratory. The triggers are clear: the legal mandates of CLIA for clinical labs, the FDA's requirements for compendial methods, and the technical necessities driven by changes in equipment, reagents, or personnel. By understanding these triggers and implementing a structured, protocol-driven verification process, laboratories can confidently ensure their methods are fit-for-purpose, their data is reliable, and their operations remain in a state of regulatory compliance. A proactive approach to verification is not just a regulatory hurdle but a fundamental component of scientific excellence and patient safety.

In microbiology laboratory research, the accurate classification of testing methods is a fundamental prerequisite for determining when and how method verification is required. Assays are broadly categorized as qualitative, quantitative, or semi-quantitative, each with distinct purposes, performance characteristics, and verification protocols [6]. Understanding these categories is critical for researchers and drug development professionals because the category dictates the validation and verification pathway a method must undergo before implementation [13].

The principles of method validation and verification are codified in standards such as the ISO 16140 series for the food chain and guidelines from bodies like the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) for clinical microbiology [13] [6]. Validation establishes that a method is fit for its intended purpose, while verification is the process by which a laboratory demonstrates that it can successfully perform a previously validated method [13] [6]. This distinction is crucial for regulatory compliance and ensuring the reliability of data in both research and diagnostic settings.

Defining the Core Assay Categories

Qualitative Assays

Qualitative methods are designed to detect the presence or absence of a specific microorganism or microbial component in a sample, providing a binary result [18] [6]. These methods do not determine the quantity of the organism present. They are typically used for detecting pathogens like Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli O157:H7, where even very low levels (e.g., 1 CFU) in a large sample portion (e.g., 25g to 375g) are significant [18].

A key feature of most qualitative methods is an amplification step, such as enrichment, to increase the target microorganism to a detectable level [18]. This step breaks the direct link to the initial concentration in the sample. Results are reported as "Detected or Not Detected" or "Positive or Negative" per the tested weight or volume (e.g., Not detected/25 g) [18].

Quantitative Assays

Quantitative methods measure the numerical concentration of specified microorganisms in a sample, reported as colony-forming units (CFU) or most probable number (MPN) per unit of weight or volume (e.g., CFU/g) [18]. These methods are essential for enumerating microbial indicators (e.g., aerobic plate count, Enterobacteriaceae) or specific organisms like Staphylococcus aureus [18].

These methods require careful serial dilution to achieve a countable range of colonies on an agar plate (e.g., 25-250 colonies) for accurate measurement [18]. The limit of detection (LOD) for quantitative plate count methods is typically 10 or 100 CFU/g, while MPN methods have an LOD of around 3 MPN/g [18]. If no target organisms are detected, the result is reported as "less than" the LOD (e.g., <10 CFU/g), which is not equivalent to a qualitative "Negative" result [18].

Semi-Quantitative Assays

Semi-quantitative methods occupy a middle ground, providing results on an ordinal scale rather than a precise numerical value [19]. These assays use numerical values or signals to determine a cutoff but report a qualitative or categorized result (e.g., "small," "moderate," "large" or a cycle threshold (Ct) value from PCR) [6] [19].

From a metrological perspective, semi-quantitative results can be ranked, but the units are not necessarily identical across the entire measuring interval [19]. These methods are often considered to have less-than-optimal quality indicators for trueness and precision compared to fully quantitative methods but offer more information than purely qualitative tests [19]. They communicate that the measurement has an inherent uncertainty while still providing a useful scale for interpretation.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Microbiological Assay Categories

| Characteristic | Qualitative Assays | Quantitative Assays | Semi-Quantitative Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Detection/identification | Enumeration | Relative estimation/categorization |

| Result Type | Binary (e.g., Positive/Negative) | Numerical (e.g., CFU/g) | Ordinal/Categorical (e.g., 1+, 2+, 3+) |

| Data Scale | Nominal [19] | Ratio [19] | Ordinal [19] |

| Key Performance Characteristics | Accuracy, Specificity [6] | Precision, Reportable Range [6] | Cut-off determination, Categorization accuracy [6] |

| Typical LOD | 1 CFU/test portion [18] | 10-100 CFU/g (plate count); 3 MPN/g (MPN) [18] | Varies, based on cut-off |

| Common Examples | Pathogen screening (e.g., Salmonella) [18] | Aerobic plate count, indicator organisms [18] | Some PCR assays with Ct values, antigen tests with graded results [6] |

Method Verification Protocols and Requirements

The Verification Mandate in Regulated Laboratories

Method verification is a mandatory requirement in regulated laboratory environments before reporting patient or research results. The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) in the United States requires verification for all non-waived test systems of moderate or high complexity [6]. This process is distinct from validation: verification confirms that a pre-validated, unmodified FDA-cleared or approved method performs according to manufacturer claims in the user's laboratory, while validation establishes method performance for laboratory-developed tests or significantly modified FDA-approved methods [6].

In the food testing sector, the ISO 16140 series provides a structured framework for method verification, delineating it as the second essential stage after method validation [13]. According to ISO 16140-3, verification involves two stages: implementation verification (demonstrating the laboratory can correctly perform the method using items from the validation study) and item verification (demonstrating competency with challenging items specific to the laboratory's scope) [13].

Category-Specific Verification Criteria

The verification requirements differ significantly based on the assay category. The table below summarizes the core verification criteria for each category as guided by CLSI standards.

Table 2: Verification Criteria by Assay Category

| Verification Characteristic | Qualitative Assays | Quantitative Assays | Semi-Quantitative Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | ≥20 positive/negative samples; calculate % agreement [6] | Statistical comparison of means against reference method | Similar to qualitative, but with samples spanning reportable categories |

| Precision | 2 positive & 2 negative samples in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators [6] | Within-run, between-run, and between-operator variance | Assess reproducibility of categorical assignments across runs and operators |

| Reportable Range | 3 known positive samples [6] | Verification of upper and lower limits of quantification | Verification of cut-off values and categorical boundaries [6] |

| Reference Range | ≥20 samples representing "normal" population [6] | Establish normal values for patient population | Verify categorical distributions match expected population patterns |

Experimental Design for Verification Studies

Designing a robust verification study requires careful planning. The first step is creating a verification plan that includes the type and purpose of the study, test method description, detailed study design (number/type of samples, replicates, operators), performance characteristics to be evaluated with acceptance criteria, required materials, and a timeline [6].

For qualitative and semi-quantitative assays common in microbiology, acceptable samples for verification can include reference materials, proficiency test samples, de-identified clinical samples previously tested with a validated method, or well-characterized isolates [6]. The number of samples should be sufficient to provide statistical confidence, with a minimum of 20 samples recommended for accuracy assessment [6].

For quantitative methods, precision is typically evaluated through repeated testing of samples across multiple days and by different operators to establish reproducibility. The reportable range must be verified by testing samples at both the upper and lower limits of quantification to ensure linearity and recovery throughout the measuring interval.

Decision Framework and Practical Implementation

Selection Criteria and Verification Workflow

Choosing between qualitative, quantitative, or semi-quantitative methods depends entirely on the research or testing objective. A qualitative method is appropriate when the goal is to detect the presence of a specific microorganism, particularly pathogens, even at very low levels [18]. A quantitative method is necessary when the numerical concentration of microorganisms is critical, such as in potency assays or when monitoring microbial loads [18]. Semi-quantitative methods are useful when relative abundance or categorization within ranges provides sufficient information for decision-making.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting and verifying microbiological methods:

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful method verification requires specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details essential solutions and their functions in verification studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Method Verification

| Reagent/Material | Function in Verification | Application Across Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Provide ground truth for accuracy assessment; characterized samples with known properties [6] | Qualitative, Quantitative, Semi-Quantitative |

| Proficiency Test Samples | External quality assessment; independently characterized samples [6] | Qualitative, Quantitative, Semi-Quantitative |

| Quality Controls (Positive/Negative) | Monitor assay performance; verify proper function of test system [6] | Qualitative, Quantitative, Semi-Quantitative |

| Well-Characterized Isolates | Assess accuracy and specificity; verify identification capabilities [6] | Qualitative, Semi-Quantitative |

| Serial Dilution Materials | Establish countable range; perform quantitative measurements [18] | Primarily Quantitative |

| Selective and Differential Media | Isolate and identify target microorganisms; confirm cultural characteristics [18] | Qualitative, Quantitative |

The distinction between qualitative, quantitative, and semi-quantitative assays is fundamental to microbiology laboratory research and directly determines when and how method verification is required. As outlined in this guide, each category has distinct purposes, performance characteristics, and verification protocols mandated by regulatory frameworks and international standards.

Method verification is not a one-size-fits-all process but must be tailored to the specific assay category and intended use. By following the structured approaches, experimental protocols, and decision frameworks presented here, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure their microbiological methods are properly verified, compliant with regulatory requirements, and capable of generating reliable, reproducible data for both research and clinical applications.

Executing Method Verification: A Step-by-Step Protocol for Microbiology Labs

In microbiology laboratory research, method verification is a fundamental process required to demonstrate that a laboratory can successfully perform a pre-validated, standardized method before using it for routine testing [13]. It is a critical checkpoint within a broader quality management system, confirming that a method's established performance characteristics can be reproduced in a specific laboratory's environment, with its specific personnel and equipment. Understanding when verification is required—as opposed to the more extensive process of method validation—is essential for regulatory compliance, data integrity, and patient safety in drug development.

The terms verification and validation are often used interchangeably, but they describe distinct activities [2]. A validation is a comprehensive process that establishes that an assay works as intended; this is required for non-FDA-cleared tests, such as laboratory-developed methods (LDM) or modified FDA-approved tests [2]. In contrast, a verification is a one-time study for unmodified, FDA-approved or cleared tests, demonstrating that the test performs in line with the manufacturer's established performance characteristics when used as intended in the user's specific environment [2]. According to the ISO 16140 series, verification consists of two stages: implementation verification (demonstrating the lab can perform the method correctly) and (food) item verification (demonstrating the method works for specific sample types within the lab's scope) [13]. For clinical laboratories, verification is mandated by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) for all non-waived testing systems before patient results can be reported [2].

Core Components of a Microbiology Verification Plan

A well-structured verification plan serves as the blueprint for the entire study. This pre-approved document details the what, how, and when of the verification activity, ensuring it is executed systematically and meets all regulatory requirements. The essential components of this plan are detailed below.

Statement of Purpose and Test Definition

The plan must begin with a clear statement of its purpose and a detailed description of the test method. This section should explicitly state whether the activity is a verification or a validation, define the intended use of the test, and describe the methodological principle [2]. For a verification, this includes confirming that the method is unmodified and FDA-approved or cleared. It should also specify the type of assay—qualitative (providing a binary result such as "detected/not detected"), quantitative (providing a numerical value), or semi-quantitative (using a numerical cutoff to determine a qualitative result) [2]. This clarity sets the scope and regulatory basis for all subsequent activities.

Detailed Study Design and Experimental Protocols

The study design is the technical core of the plan, specifying the performance characteristics to be evaluated, the acceptance criteria, and the experimental methodology for each. For an unmodified FDA-approved test, CLIA requires verification of accuracy, precision, reportable range, and reference range [2]. The following sections provide detailed experimental protocols for these key characteristics in the context of qualitative and semi-quantitative microbiology assays.

Verification of Accuracy

Accuracy confirms the acceptable agreement of results between the new method and a comparative method [2].

- Experimental Protocol: Use a minimum of 20 clinically relevant isolates or samples [2]. For qualitative assays, use a combination of positive and negative samples. For semi-quantitative assays, use a range of samples with high to low values. Acceptable specimens can include certified reference materials, proficiency test samples, or de-identified clinical samples previously characterized by a validated method [2]. Test all samples using the new method and compare the results to those obtained from the comparative method.

- Calculation and Acceptance Criteria: Calculate accuracy as the number of results in agreement divided by the total number of results, multiplied by 100. The acceptable percentage of accuracy should meet the manufacturer's stated claims or a level determined by the Laboratory Director [2].

Verification of Precision

Precision confirms acceptable variance within a run, between runs, and between different operators [2].

- Experimental Protocol: Use a minimum of two positive and two negative samples, tested in triplicate over five days by two different operators [2]. If the system is fully automated, testing for user variance may not be required. The samples can be controls or de-identified clinical samples.

- Calculation and Acceptance Criteria: Calculate precision for each level of testing (e.g., within-run, between-day, between-operator) as the number of results in agreement divided by the total number of results, multiplied by 100. The acceptance criteria should align with the manufacturer's claims or the Laboratory Director's specifications [2].

Verification of Reportable Range

The reportable range confirms the acceptable upper and lower limits of the test system [2].

- Experimental Protocol: Verify using a minimum of three samples [2]. For qualitative assays, use known positive samples. For semi-quantitative assays, use a range of positive samples near the upper and lower ends of the manufacturer-determined cutoff values.

- Evaluation: The reportable range is defined as what the laboratory establishes as a reportable result (e.g., "Detected," "Not detected," or a specific cycle threshold (Ct) value cutoff). Verification involves testing samples to confirm they fall within and are correctly reported across this defined range [2].

Verification of Reference Range

The reference range confirms the normal expected result for the tested patient population [2].

- Experimental Protocol: Verify using a minimum of 20 isolates [2]. Use de-identified clinical samples or reference samples with a result known to be standard for the laboratory’s patient population (e.g., samples negative for MRSA for an MRSA detection assay).

- Evaluation: The reference range is verified by testing samples representative of the laboratory's patient population. If the manufacturer's reference range does not represent this population, the laboratory must screen additional samples and potentially redefine the reference range [2].

Materials, Equipment, and Resource Requirements

This section provides a comprehensive list of all resources required to execute the verification study. This includes specific materials, validated equipment, and other critical resources.

- Research Reagent Solutions: The plan must catalog all critical reagents, their sources (e.g., certified reference materials, proficiency test samples, commercially prepared media), and quality control requirements (e.g., growth promotion testing for media, certificate of analysis review) [2] [20].

- Validated Equipment and Systems: All equipment used in the verification—such as incubators, pipettes, centrifuges, PCR systems, and the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS)—must be listed. The plan should reference their current Installation, Operational, and Performance Qualification (IOPQ) status, which is a non-negotiable requirement for cGMP testing and strongly recommended for all clinical labs [15] [20]. IOPQ ensures equipment is installed correctly, operates according to specifications, and performs consistently under real-world conditions [15].

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Microbiological Verification

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Microorganisms | ATCC strains; certified reference materials from national collections [20] | Serves as positive controls and challenge organisms for accuracy, precision, and specificity testing. |

| Culture Media | Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA); Mueller Hinton Broth; Selective and differential agars [20] | Supports microbial growth for testing; quality is verified through growth promotion and sterility checks. |

| Clinical Isolates & Samples | De-identified patient samples; proficiency test samples; contrived samples [2] | Provides a clinically relevant matrix for verifying method performance against a comparative method. |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | PCR master mixes; primers and probes; DNA extraction kits [2] | Essential for molecular methods like real-time PCR for pathogen detection and identification. |

Safety Considerations and Project Timeline

The verification plan must explicitly address laboratory safety protocols for handling biological specimens, chemical hazards, and any other potential risks. This includes requirements for personal protective equipment (PPE), biosafety levels, and waste disposal procedures [2].

Finally, the plan should outline a realistic timeline for completion, including key milestones for each phase of the verification (e.g., protocol finalization, sample acquisition, testing phase, data analysis, and report writing). This facilitates project management and ensures timely implementation of the new method.

The Verification Workflow and Director Approval

The entire verification process, from planning to final approval, follows a logical sequence of activities with the Laboratory Director's oversight as a constant thread. The following diagram visualizes this workflow and the critical approval gates.

Diagram: Microbiology Method Verification and Approval Workflow

The Role of the Laboratory Director

The Laboratory Director's role is paramount throughout the verification process. As highlighted in the workflow, the Director holds ultimate responsibility for reviewing and signing off on the verification plan before any testing begins [2]. This review ensures the study design is scientifically sound, addresses all required performance characteristics, and has appropriate acceptance criteria. Furthermore, after the study is executed and a final report is compiled, the Director must provide final approval, confirming that the data demonstrate the method is acceptable for clinical use [2]. This final approval is a regulatory requirement under CLIA and signifies the formal acceptance of the method into the laboratory's test menu.

Regulatory Framework and Essential Documentation

A successful verification is not only about the science but also about rigorous documentation that provides an auditable trail of the entire process.

The Three-Part Documentation Structure

The verification process generates a structured documentation package that transforms experimental data into a legally defensible and auditable record [21].

- The Validation/Verification Protocol: This is the pre-approved master document that details the entire plan—purpose, scope, study design, acceptance criteria, and methodologies [2] [21]. It is the commitment document that is signed before the study begins.

- Raw Data: All data generated during the execution of the protocol must be meticulously recorded and maintained. This includes instrument printouts, worksheets, calculation records, and notes on any deviations from the protocol [21].

- The Final Verification Report: This report summarizes the results against each acceptance criterion defined in the protocol. It must clearly state whether the method passed or failed each criterion, discuss any deviations, and provide a final conclusion on the method's fitness for use. This report requires the final signature of approval from the Laboratory Director [2] [21].

Key Regulatory Standards and Guidelines

Adherence to globally recognized standards is critical for regulatory compliance. Key guidance documents for microbiology verification include:

- CLSI M52: Verification of Commercial Microbial Identification and AST Systems [2].

- CLSI EP12-A2: User Protocol for Evaluation of Qualitative Test Performance [2].

- ISO 16140-3: Protocol for the verification of reference methods and validated alternative methods in a single laboratory [13].

- USP General Chapters: Such as <1225> for validation of compendial procedures and <1226> for verification of compendial procedures [21] [14].

Table: Quantitative Sample Requirements for Verification of Qualitative/Semi-Quantitative Assays

| Performance Characteristic | Minimum Sample Number | Sample Type Recommendations | Experimental Replication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 20 isolates/samples [2] | Combination of positive and negative clinical isolates; reference materials [2] | Single test per sample, compared to a reference method [2]. |

| Precision | 2 positive + 2 negative samples [2] | Controls or de-identified clinical samples [2] | Triplicate testing for 5 days by 2 operators [2]. |

| Reportable Range | 3 samples [2] | Known positives; samples near cutoff values [2] | Testing to verify upper and lower limits of detection/reporting [2]. |

| Reference Range | 20 isolates/samples [2] | Samples representative of the lab's patient population [2] | Testing to confirm normal expected results [2]. |

Developing a robust verification plan is a critical, non-negotiable step in implementing any new microbiological method in a research or diagnostic setting. This process, culminating in the formal approval of the Laboratory Director, ensures that methods perform reliably in a specific laboratory environment, thereby safeguarding data integrity, regulatory compliance, and ultimately, patient safety. As regulatory scrutiny intensifies—with the FDA increasingly focused on documented validation and verification—adhering to a structured framework with clear components, detailed experimental protocols, and comprehensive documentation is not just a best practice but a fundamental requirement for any credible microbiology laboratory involved in drug development and clinical research.

In biomedical and clinical research, sample size determination is the process of calculating the number of participants or observations needed for a successful experiment that can yield generalizable results to the broader population [22]. This calculation is a critical aspect of study design that directly impacts the scientific validity and statistical soundness of research outcomes [23] [22]. Appropriate sample size selection balances scientific rigor with ethical considerations and resource allocation, ensuring that studies have adequate power to detect clinically significant effects without unnecessarily exposing subjects to risk or consuming excessive resources [24].

Within microbiology laboratories, the principles of sample size determination extend beyond clinical studies to inform method verification and validation processes. When implementing new diagnostic methods, laboratories must conduct studies with sufficient sample sizes to confidently establish method performance characteristics, including accuracy, precision, and reportable ranges [2]. The determination of appropriate sample size therefore serves as a cornerstone for researchers seeking to draw precise inferences across the spectrum of biomedical and clinical investigations [22].

Key Statistical Concepts in Sample Size Determination

Core Components and Definitions

Table 1: Fundamental Statistical Concepts for Sample Size Calculation

| Concept | Definition | Role in Sample Size Calculation | Common Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis (H₀) | Statement that no relationship or difference exists between variables | Forms the basis for statistical testing; sample size determines ability to reject when false | No effect or no difference |

| Alternative Hypothesis (H₁) | Statement that a specific relationship or difference exists | Represents the effect the study aims to detect | Specific effect size |

| Significance Level (α) | Probability of rejecting H₀ when it is actually true (Type I error) | Sets threshold for statistical significance; lower α requires larger sample size | 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 |

| Power (1-β) | Probability of correctly rejecting H₀ when H₁ is true | Primary determinant of sample size; higher power requires larger sample size | 0.8, 0.9, 0.95 |

| Effect Size | Magnitude of the effect of practical or clinical importance | Larger effect sizes require smaller samples; most challenging parameter to specify | Varies by field and context |

| Standard Deviation | Measure of variability in the data | More variable data requires larger sample sizes | Estimated from pilot studies or literature |

Error Types and Statistical Power

Statistical hypothesis testing involves balancing two potential errors [23]. A Type I error (false positive) occurs when the null hypothesis is incorrectly rejected, while a Type II error (false negative) happens when the null hypothesis is incorrectly retained. The probability of committing a Type I error is denoted by α (significance level), while the probability of a Type II error is denoted by β. Statistical power, defined as 1-β, represents the probability of correctly detecting an effect when one truly exists [23] [22].

The relationship between these elements is crucial: reducing the risk of one error type typically increases the risk of the other unless sample size is increased. For most clinical trials, a power of 0.8 (80%) is considered optimal, meaning there is an 80% chance of detecting a specified effect size if it truly exists [22]. However, higher power (90% or 95%) may be required for studies where missing a true effect would have serious consequences [23].

Sample Size Calculation by Study Design

Cross-Sectional Studies and Surveys

Cross-sectional studies measure prevalence or proportion of characteristics in a population at a specific point in time [22]. The sample size formula for estimating a proportion is:

$$n = \frac{(Z_{1-α/2})^2 \times p \times (1-p)}{d^2}$$

Where:

- n = required sample size

- Z₁₋α/₂ = critical value from standard normal distribution (1.96 for 95% confidence)

- p = estimated proportion or prevalence

- d = margin of error (precision) [22]

Table 2: Sample Size Requirements for Cross-Sectional Studies (95% Confidence Level)

| Expected Prevalence | Margin of Error (d) | Required Sample Size | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 (50%) | 0.05 (5%) | 385 | Prevalence of antibiotic resistance |

| 0.2 (20%) | 0.05 (5%) | 246 | Prevalence of hospital-acquired infection |

| 0.1 (10%) | 0.05 (5%) | 139 | Prevalence of rare pathogen |

| 0.05 (5%) | 0.03 (3%) | 203 | Prevalence of specific genetic marker |

| 0.5 (50%) | 0.03 (3%) | 1068 | High-precision prevalence studies |

Example Calculation: In a study to determine the prevalence of liver diseases in a population where previous research indicated a 9% prevalence, with 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error [22]:

- Z₁₋α/₂ = 1.96

- p = 0.09

- d = 0.05

- Calculation: n = (1.96² × 0.09 × 0.91) / 0.05² = 126

Comparative and Experimental Studies

For studies comparing two groups, different formulas apply based on the outcome type (continuous vs. categorical) [23] [24]. For two independent proportions, the sample size per group is calculated as:

$$n = \frac{(Z{1-α/2} + Z{1-β})^2 \times [p1(1-p1) + p2(1-p2)]}{(p1 - p2)^2}$$

Where:

- p₁ and p₂ = expected proportions in the two groups

- Z₁₋α/₂ and Z₁₋β = critical values for Type I and Type II errors [23]

For continuous outcomes comparing two means, the formula becomes:

$$n = \frac{(Z{1-α/2} + Z{1-β})^2 \times 2σ^2}{d^2}$$

Where:

- σ = standard deviation of the outcome variable

- d = clinically important difference to detect [24]

Figure 1: Sample Size Determination Workflow

Special Considerations for Microbiome Studies

Microbiome studies present unique challenges for sample size calculation due to the high-dimensional nature of microbiome data and specific features like compositionality, sparsity, and heterogeneous distribution of microbial taxa [25]. Power calculations for microbiome studies must account for whether microbiome features are hypothesized to be the outcome, exposure, or mediator in the analysis [25]. Specialized statistical approaches and R scripts have been developed to address these unique requirements, moving beyond classic sample size calculations that don't accommodate the intrinsic features of microbiome datasets [25].

Sample Size in Method Verification and Validation

Method Verification in Microbiology Laboratories

In clinical microbiology laboratories, method verification studies are required by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) for non-waived systems before reporting patient results [2]. These studies demonstrate that a laboratory can reliably implement a previously validated method. It's crucial to distinguish between verification (confirming proper performance of an FDA-approved method) and validation (establishing performance characteristics for laboratory-developed or modified methods) [2] [13].

The ISO 16140 series provides international standards for method validation and verification in food chain microbiology, outlining a two-stage process [13]:

- Method validation establishes that a method is fit for purpose

- Method verification demonstrates that a laboratory can properly perform the validated method [13]

Table 3: Minimum Sample Requirements for Method Verification of Qualitative/Semi-Quantitative Assays

| Performance Characteristic | Minimum Samples | Sample Types | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 20 clinically relevant isolates | Combination of positive and negative samples; range of values for semi-quantitative assays | Meets manufacturer claims or laboratory director determination |

| Precision | 2 positive + 2 negative tested in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators | Controls or de-identified clinical samples | Meets manufacturer claims or laboratory director determination |

| Reportable Range | 3 samples | Known positives; samples near cutoff values for semi-quantitative assays | Laboratory-established reportable result verified |

| Reference Range | 20 isolates | De-identified clinical samples representing patient population | Expected result for typical sample verified |

Specimen Collection and Quality Considerations

The reliability of microbiological analyses depends heavily on appropriate specimen selection, collection technique, and transport conditions [26] [27]. Even with perfect sample size calculations, results will be compromised by poor specimen management. Key principles include:

- Collect specimens before antibiotic administration whenever possible [27]

- Prefer tissue, fluid, or aspirates over swabs when feasible [27]

- Use appropriate transport media and conditions (temperature, time) [26] [27]

- Ensure proper specimen labeling with specific site information [27]

For anaerobic cultures, special collection procedures are essential. Swabs are generally unacceptable due to oxygen exposure, inhibitory substances in swab materials, and small specimen volumes. Instead, needle aspirates or tissue biopsies should be placed into anaerobic transport media and transported at room temperature [26].

Practical Implementation and Tools

Sample size calculation need not be done manually, with several specialized software tools available [24]:

- G*Power: Statistical software package for power analysis

- OpenEpi: Open-source online calculator for various study designs

- PS Power and Sample Size Calculation: Practical tool for studies with dichotomous, continuous, or survival outcomes

- Sample Size Calculator: Web-based tool for common study designs

These tools vary in their interfaces, mathematical formulas, and assumptions, so researchers should understand the underlying principles to select appropriate tools and interpret results correctly [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Microbiological Studies and Verification

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Transport Medium (ATM) | Preserves viability of anaerobic organisms during transport | Specimens must be transported at room temperature; swabs not acceptable [26] |

| Flocked Swabs | Improved specimen collection and release | More effective than Dacron, rayon, or cotton swabs for many applications [27] |

| Specialized Media | Selective growth of target microorganisms | Different media required for MRSA vs. C. difficile surveillance cultures [26] |

| Quality Controls | Verification of method performance | Include positive, negative, and quantitative controls as appropriate [2] |

| Reference Strains | Method verification and quality assurance | Well-characterized strains for accuracy assessment [2] |

Effect Size Determination Strategies

The effect size is often the most challenging parameter to specify in sample size calculations [24]. Several approaches can be used:

- Pilot studies: Conduct small-scale preliminary studies to estimate effect sizes

- Previous research: Consult meta-analyses or similar published studies

- Clinical significance: Determine the minimum effect that would be clinically meaningful

- Standardized values: Use conventional small (0.2), medium (0.5), or large (0.8) effect sizes when no other information is available [24]