Measuring Microbial Activity with RNA Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) as a powerful tool for measuring functional microbial activity in complex communities.

Measuring Microbial Activity with RNA Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) as a powerful tool for measuring functional microbial activity in complex communities. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, from distinguishing between microbial presence and activity to exploring the roles of different RNA types. It details optimized methodologies for RNA extraction and library preparation from challenging samples like soil, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and validates the approach through comparative analysis with DNA-based methods. The scope extends to diverse applications, including environmental microbiomes, host-pathogen interactions, and drug discovery, offering a practical guide for implementing and interpreting microbial metatranscriptomics.

From Presence to Activity: Foundational Principles of Microbial RNA Analysis

Why RNA-Seq? Moving Beyond DNA to Capture Functional Activity

While genomic sequencing provides a static blueprint of an organism's potential, it reveals little about dynamic biological processes. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has emerged as a transformative technology that bridges this gap by capturing the transcriptome—the complete set of RNA transcripts present in a cell or community at a specific moment. This capability to profile functional activity rather than just genetic potential is particularly valuable in microbial research, where up to 70% of proteins in even well-characterized communities like the human gut microbiome remain functionally uncharacterized based on DNA evidence alone [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, RNA-Seq provides critical insights into microbial gene regulation, metabolic pathways, and responses to environmental stimuli, pharmaceutical compounds, and host interactions that are undetectable through DNA-based approaches.

The power of RNA-Seq lies in its ability to provide a comprehensive, quantitative snapshot of gene expression. Since its introduction in 2008, RNA-Seq has generated an exponentially growing wealth of data, with PubMed listings reaching 2,808 publications by 2016 [2]. This growth reflects the technology's increasing accessibility and its pivotal role in revealing active biological pathways, identifying novel therapeutic targets, and understanding disease mechanisms at a molecular level.

Key Applications in Microbial Research and Drug Development

Elucidating Function in Microbial Communities

In microbial communities, RNA-Seq (specifically metatranscriptomics) enables researchers to determine which genes are actively expressed under different conditions, providing insights into community interactions, metabolic specialization, and functional responses:

Functional Annotation: A novel method called FUGAsseM leverages community-wide multiomics data to predict functions for uncharacterized microbial proteins. This approach has successfully predicted high-confidence functions for >443,000 protein families, approximately 82.3% of which were previously uncharacterized. Notably, this included >27,000 protein families with only remote homology to known proteins and >6,000 families without any homology [1].

Pathway Activity Profiling: Genes involved in the same biological pathway tend to be co-expressed. RNA-Seq captures these coexpression patterns, allowing researchers to infer pathway membership and activity for uncharacterized genes, moving beyond the limitations of sequence similarity alone [1].

Microbial Dark Matter Exploration: Even in well-studied microorganisms like Escherichia coli, pangenomes derived from typical communities remain predominantly uncharacterized. While E. coli K-12 reference strains have 64.6% of protein families annotated with biological process terms, only 37.6% of proteins in the E. coli pangenome have such annotations, with 24.9% lacking any Gene Ontology annotations [1].

Drug Discovery and Development Applications

RNA-Seq provides powerful approaches throughout the drug development pipeline, from initial target identification to mechanism of action studies:

Target Identification: RNA-Seq can reveal expression patterns in response to treatment, helping identify potential drug targets by highlighting pathways critical to disease states or microbial viability [3].

Mode-of-Action Studies: Analyzing transcriptomic changes following drug treatment can elucidate a compound's mechanism of action by revealing which pathways and processes are affected [3].

Biomarker Discovery: Expression signatures can serve as biomarkers for disease progression, treatment response, or toxicological effects [3].

Dose-Response Characterization: Kinetic RNA-Seq approaches monitor transcriptome changes over time and at different drug concentrations, distinguishing primary from secondary drug effects and identifying optimal therapeutic windows [3].

Table 1: RNA-Seq Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

| Application | Key Insights | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Expression patterns in disease vs. healthy states; essential pathways | Multiple cell lines/tissues; sufficient biological replicates |

| Mode-of-Action Studies | Early transcriptional responses; affected pathways and processes | Multiple time points; kinetic approaches like SLAMseq |

| Biomarker Discovery | Gene expression signatures correlating with disease or treatment response | Large cohort sizes; validation in independent datasets |

| Dose-Response Studies | Concentration-dependent effects; therapeutic windows | Multiple dosage levels; time course experiments |

Experimental Design and Workflow

Critical Design Considerations

Robust experimental design is fundamental to generating meaningful RNA-Seq data:

Hypothesis-Driven Objectives: Begin with a clear hypothesis and specific aims to guide choices in model systems, experimental conditions, controls, and analytical approaches [3].

Replication Strategy: Include sufficient biological replicates (independent samples from the same experimental group) to account for natural variation. Typically, 3-8 replicates per condition are recommended, with higher numbers increasing statistical power and reliability [3].

Batch Effect Control: Systematic non-biological variations can arise from how samples are processed. Implement strategies such as randomizing sample processing orders, including controls in each batch, and using spike-in controls to enable batch correction during analysis [3] [4].

Sample Size Planning: The ideal sample size balances statistical power, practical constraints, and cost. Pilot studies are valuable for estimating variability and determining appropriate sample sizes for main experiments [3].

Microbial Single-Cell RNA-Seq Considerations

Applying RNA-Seq to microbial communities presents unique challenges and opportunities:

Cell Wall Integrity: The rigid microbial cell wall requires specialized lysis protocols different from those used for mammalian cells [5].

mRNA Capture: Unlike eukaryotic mRNAs with poly(A) tails, bacterial mRNAs require alternative capture methods such as random priming, poly(A) polymerase treatment, or gene-specific probes [5].

rRNA Depletion: Ribosomal RNA constitutes >90% of bacterial RNA content, necessitating effective depletion strategies such as Cas9 cleavage, RNase H digestion, or cDNA pull-down methods [5].

Single-Cell Applications: Recent advances enable single-cell RNA sequencing in microbes, revealing functional heterogeneity within populations:

- Combinatorial indexing methods (PETRI-seq, microSPLiT, BaSSSh-seq) enable profiling of thousands of cells without specialized equipment [5].

- Droplet-based methods (smRandom-seq, ProBac-seq) provide high-throughput single-cell analysis with good transcript capture efficiency [5].

- Flow sorting approaches (MATQ-seq) allow enrichment of specific subpopulations with higher transcripts per cell [5].

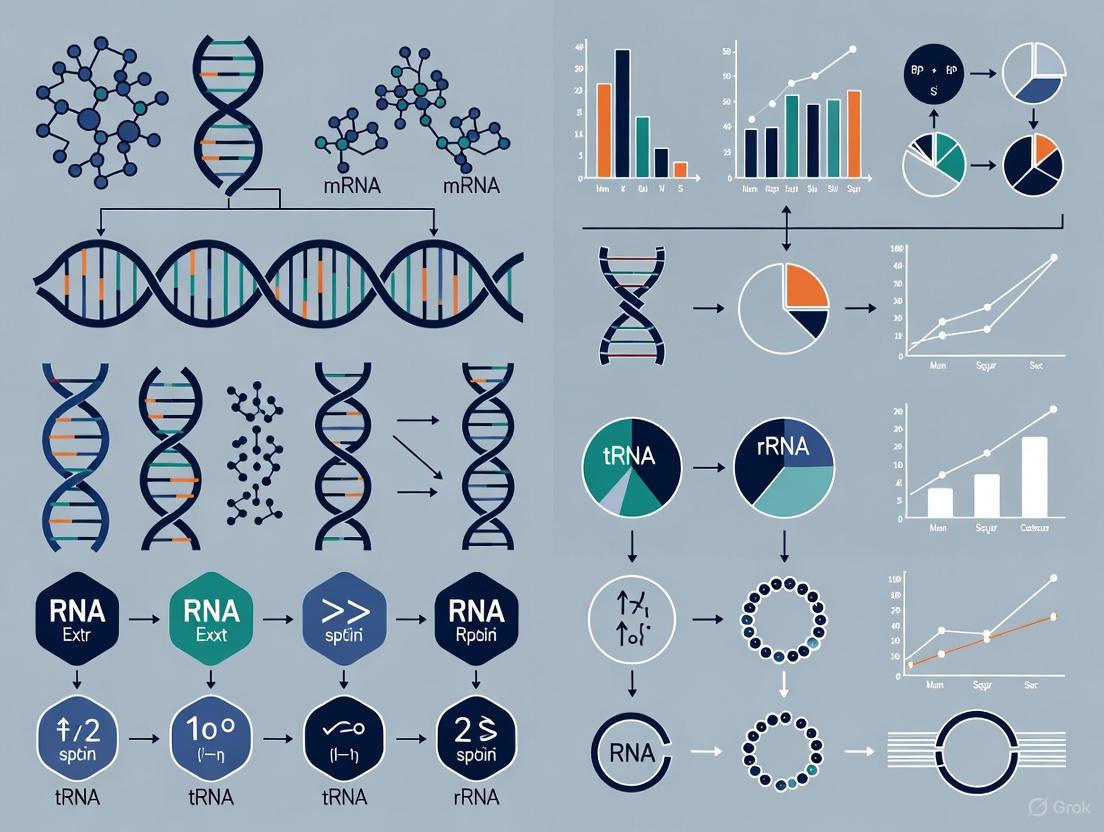

Diagram 1: RNA-Seq experimental and computational workflow

Data Analysis Framework

Analysis Workflow and Quality Control

RNA-Seq data analysis requires a structured approach to transform raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful insights:

Primary Analysis: Conversion of raw sequencing signals into base calls and demultiplexing of samples [2] [6].

Secondary Analysis: Alignment of reads to a reference genome and generation of count tables quantifying gene expression levels [2].

Quality Assessment: Critical quality metrics include:

Differential Expression Analysis: Statistical testing to identify genes with significant expression changes between conditions using tools such as DESeq2 and edgeR, which employ negative binomial models to account for biological variability and technical noise [2] [6].

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Coexpression Network Analysis: Genes with similar functions often show coordinated expression patterns. Methods like Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) can identify functionally related gene modules [1] [7].

CoRegNet: A novel statistical approach based on beta-binomial distributions that constructs robust gene co-regulation networks across thousands of heterogeneous experiments, overcoming limitations of traditional correlation-based methods when integrating diverse datasets [7].

Functional Enrichment Analysis: Interpretation of differentially expressed genes in the context of biological pathways, molecular functions, and cellular components using Gene Ontology, KEGG, and other annotation databases [6].

Table 2: Essential RNA-Seq Analysis Tools and Their Applications

| Tool Category | Representative Tools | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment | TopHat2, STAR | Map sequencing reads to reference genome | Depends on reference quality; affects mapping rates |

| Quantification | HTSeq, featureCounts | Generate count tables for genes/transcripts | Affected by annotation quality |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, edgeR | Identify statistically significant expression changes | Require biological replicates; different statistical models |

| Quality Control | RSeQC, Picard | Assess read distribution, rRNA content, duplicates | Essential for validating data quality |

| Functional Enrichment | clusterProfiler, GSEA | Interpret results in biological context | Dependent on annotation completeness |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful RNA-Seq experiments rely on appropriate reagents and controls tailored to the research question and sample type:

RNA Stabilization Reagents: Compounds that immediately stabilize RNA at collection to preserve accurate transcriptional profiles, especially critical for clinical samples or time-course experiments [3].

rRNA Depletion Kits: Probe sets that selectively remove abundant ribosomal RNA, dramatically improving sequencing coverage of informative transcripts, particularly important for prokaryotic samples [5] [6].

Spike-In Controls: Synthetic RNA sequences (e.g., ERCC, SIRVs) added in known quantities to enable normalization, assessment of technical variability, and quantification accuracy across samples and batches [3] [6].

Library Preparation Kits: Tailored to specific applications—3' mRNA-Seq (e.g., QuantSeq) for high-throughput gene expression studies, whole transcriptome approaches for isoform analysis, and single-cell kits for cellular heterogeneity studies [3] [5] [6].

DNA Removal Reagents: DNase treatments to eliminate genomic DNA contamination that would otherwise confound RNA-Seq results [6].

RNA-Seq represents a fundamental advancement beyond DNA sequencing by capturing the dynamic functional activity of cells and microbial communities. Its ability to profile transcriptomes comprehensively and quantitatively has made it indispensable for understanding microbial community function, identifying drug targets, and elucidating mechanisms of action. As methodologies continue to evolve—particularly in the realm of single-cell transcriptomics and integrated multiomics approaches—RNA-Seq will remain at the forefront of functional genomics, providing increasingly sophisticated insights into biological systems and accelerating therapeutic development.

The successful implementation of RNA-Seq requires careful experimental design, appropriate analytical strategies, and awareness of both its power and limitations. By moving beyond static genetic information to capture dynamic functional activity, RNA-Seq empowers researchers to address fundamental biological questions and translate findings into practical applications across microbiology, medicine, and drug development.

The microbial transcriptome constitutes the complete set of RNA molecules transcribed from the genome of a microbial community, including messenger RNA (mRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), and various regulatory non-coding RNAs. This dynamic entity provides a snapshot of functional microbial activity, revealing which genes are actively being expressed under specific environmental conditions, from host-pathogen interactions to soil ecosystems. Unlike genomic DNA, which offers information about metabolic potential, the transcriptome captures active physiological processes, making it indispensable for understanding microbial behavior in natural environments, host systems, and industrial or drug discovery contexts [8] [9]. Advanced RNA sequencing technologies have revolutionized our ability to decode this complexity, enabling researchers to move beyond census-taking to understanding functional dynamics in microbiomes.

The composition of the microbial transcriptome is dominated by rRNA, which typically comprises 82-90% of a cell's total RNA pool and serves as a fundamental structural component of ribosomes [8]. Despite its abundance, mRNA is the primary target for most functional studies because its abundance often correlates with protein-coding gene activity. Furthermore, the growing field of epitranscriptomics has revealed that RNA modifications serve as critical regulatory strategies for pathogens, influencing their adaptability, virulence, and replication during host-microbe interactions [10]. These modifications, including m6A, m5C, and ac4C on mRNAs, tRNAs, and rRNAs, represent a sophisticated layer of post-transcriptional control that microbes exploit to survive in dynamic environments.

Components of the Microbial Transcriptome

Messenger RNA (mRNA)

Messenger RNA serves as the transient intermediary between genes encoded in DNA and functional proteins, making it the most direct indicator of a microbe's metabolic activity. In metatranscriptomic studies, mRNA profiling allows researchers to identify which metabolic pathways are active within a community, from nutrient cycling in environmental samples to virulence factor expression in pathogens. A key challenge in mRNA analysis lies in its relatively low abundance compared to rRNA and its lack of poly-A tails in prokaryotic organisms, necessitating specialized enrichment or depletion techniques during library preparation [11]. The stability of bacterial mRNA, which typically has a shorter half-life than eukaryotic mRNA, means that transcriptome profiles provide a near real-time view of microbial responses to environmental stimuli, drug treatments, or other perturbations.

Recent evidence indicates that bacterial mRNA modifications play crucial regulatory roles in pathogen adaptability. For instance, in Acinetobacter baumannii, mRNA modifications (m5C, m6A, and Ψ) on iron-chelating genes (exbD and feoB) modulate iron uptake and enhance bacterial survival during infection, demonstrating how epitranscriptomic marks directly influence nutrient assimilation in host environments [10]. Similarly, in Escherichia coli, increased levels of m5C, m6A, and N6,N6-dimethyladenosine in 16S rRNA occur in response to heat shock conditions, facilitating bacterial adaptation to thermal stress [10]. These findings highlight the underappreciated regulatory functions of mRNA modifications in microbial physiology.

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA)

Ribosomal RNA constitutes the structural and functional core of ribosomes, the protein synthesis machinery of the cell. While rRNA genes are routinely sequenced (via 16S for prokaryotes and 18S for eukaryotes) for phylogenetic classification in microbial ecology, the rRNA transcripts themselves have historically been used as indicators of microbial "activity" or growth states [8] [12]. The underlying assumption is that cells with higher ribosome content are more metabolically active and capable of protein synthesis. This approach has been applied to identify active fractions of microbes in diverse environments, including soils, oceans, and host-associated microbiomes.

However, the relationship between rRNA content and microbial activity is not straightforward. Critical limitations have been identified in using rRNA as a reliable indicator of metabolic state [8]:

- Non-linear correlation with growth rate: The relationship between rRNA concentration and growth rate is not consistent across all measured growth rates and can break down altogether, especially outside balanced growth conditions.

- Taxonomic variability: The relationship between rRNA concentration and growth rate differs significantly among microbial taxa, making cross-species comparisons of relative activity problematic.

- Persistence in dormant cells: Dormant cells can maintain high ribosome numbers, leading to false positives for activity detection in environments likely to contain dormant microbes (e.g., spores).

- Unknown relationship with non-growth activities: The connection between non-growth metabolic functions and rRNA concentration remains largely uninvestigated.

These limitations necessitate a more nuanced interpretation of rRNA-based assessments and underscore the importance of complementing such data with mRNA and other functional metrics.

Regulatory RNAs and RNA Structural Switches

Beyond the classical RNA classes, microbial transcriptomes contain diverse regulatory RNAs that fine-tune gene expression in response to environmental cues. These include small RNAs (sRNAs), antisense RNAs, riboswitches, and RNA thermometers that modulate transcription, translation, or RNA stability through complementary base-pairing interactions. RNA structural switches represent a particularly sophisticated mechanism where RNAs interconvert between alternative conformations to regulate gene expression [13].

Recent transcriptome-wide mapping of RNA secondary structure ensembles in Escherichia coli has revealed that approximately 16.6% of analyzed RNA regions populate two or more structural conformations, indicating widespread structural heterogeneity with potential regulatory consequences [13]. These dynamic structural elements enable microbes to rapidly adapt to changing conditions without requiring new protein synthesis. For example, RNA thermometers in the 5' untranslated regions (UTRs) of cspG, cspI, cpxP, and lpxP mRNAs in E. coli undergo temperature-dependent structural rearrangements that control translation efficiency in response to cold shock [13]. Similarly, riboswitches in the 5' UTRs of bacterial mRNAs alter their structure upon binding specific metabolites (e.g., FMN, Mg2+, TPP, lysine), thereby modulating the expression of downstream genes involved in biosynthesis or transport [13].

Table 1: Key Components of the Microbial Transcriptome and Their Research Applications

| Transcriptome Component | Primary Function | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Protein coding; direct indicator of gene expression | Pathway activity profiling; functional response to treatments; biomarker discovery | Low abundance in bacteria; requires rRNA depletion; no universal poly-A tails |

| rRNA | Ribosomal structural RNA; protein synthesis | Phylogenetic identification; historical indicator of cellular activity | Dominates RNA pool (82-90%); requires depletion for mRNA studies; problematic activity indicator |

| tRNA | Amino acid transport to ribosomes | Translation efficiency; codon usage bias; modification studies | Modifications affect function; hypoxia alters tRNA pool in pathogens |

| Regulatory RNAs | Gene expression regulation | Virulence regulation; stress adaptation mechanisms; antibiotic resistance | Includes sRNAs, riboswitches, RNA thermometers; structural dynamics important |

| RNA Modifications | Post-transcriptional regulation (m6A, m5C, ac4C, Ψ) | Pathogen adaptation; virulence; drug resistance studies | Emerging field (epitranscriptomics); requires specialized sequencing methods |

Methodological Framework: From Sample to Analysis

Experimental Design Considerations

Robust experimental design forms the foundation of reliable transcriptomic research. Several critical factors must be addressed during planning:

- Hypothesis and Objectives: Begin with a clearly defined hypothesis and experimental aims, as these will guide decisions on model systems, conditions, controls, library preparation methods, and sequencing parameters [3]. Determine whether your study requires a global, unbiased readout or a targeted approach, and what type of differential expression you expect to find.

- Sample Size and Replication: Statistical power depends heavily on appropriate sample size and replication. Biological replicates (independent samples from the same experimental group) are essential to account for natural variation and ensure findings are generalizable. While 3 biological replicates per condition are typically recommended, between 4-8 replicates per sample group better cover most experimental requirements, particularly for detecting subtle expression changes [3]. Technical replicates (multiple measurements of the same biological sample) are less critical but can help assess technical variation in sequencing runs or laboratory workflows.

- Batch Effects and Controls: Large-scale studies inevitably introduce batch effects—systematic, non-biological variations arising from how samples are collected and processed over time or across multiple sites. Experimental designs should minimize batch effects through randomization and include appropriate controls that enable statistical correction during analysis [3]. Artificial spike-in controls provide internal standards for quantifying RNA levels between samples, assessing technical variability, and ensuring data consistency across large experiments [3].

Pilot studies represent a valuable strategy for mitigating risks in main experiments, allowing researchers to validate parameters, test wet lab and data analysis workflows, and make necessary adjustments before committing to full-scale studies [3].

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

Obtaining high-quality RNA from microbial samples, particularly complex environmental matrices like soil, presents significant technical challenges. Humic acids, phenolics, and other contaminants can co-purify with RNA and inhibit downstream molecular applications. Additionally, the ubiquity of robust RNases in environmental samples requires carefully controlled extraction conditions [11].

An optimized CTAB phenol-chloroform extraction protocol has been developed specifically for challenging samples like clay-rich rhizosphere soils, significantly improving RNA yield and quality compared to commercial kits [11]. Key steps in this protocol include:

- Homogenization of 250 mg soil samples with silica beads in CTAB extraction buffer

- Organic extraction using water-saturated phenol and chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (49:1)

- Precipitation with PEG-NaCl solution

- Purification using commercial clean-up kits supplemented with DNase I

Comprehensive quality assessment should include:

- Quantification using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit fluorometer)

- Purity assessment via A260/A280 and A260/230 ratios (NanoDrop spectrophotometer)

- Integrity evaluation through RNA Integrity Number (RINe) or similar metrics (e.g., Agilent TapeStation)

Table 2: Comparison of Transcriptomic Approaches for Microbial Community Analysis

| Methodological Aspect | Total RNA-seq | Amplicon-seq (16S/18S) | Metatranscriptomics (rRNA-depleted) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Molecules | All RNA species | Specific rRNA genes | mRNA & non-rRNA transcripts |

| PCR Amplification Bias | Minimal | Significant | Minimal |

| Cross-Domain Analysis | Yes (bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes simultaneously) | No (separate analyses required) | Yes (theoretically possible) |

| Functional Insights | Limited for mRNA without depletion | Indirect inference only | Direct assessment of expressed functions |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus to species level with mapping-based approaches [12] | Genus to family level | Dependent on reference databases |

| Quantitative Accuracy | High (median ~10% abundance in mock community) [12] | Variable, often lower than actual proportions | Relative expression levels |

| Technical Challenges | rRNA dominates sequencing output | Primer bias, chimera formation | Efficient rRNA depletion, high RNA quality |

rRNA Depletion and Library Preparation

Effective removal of abundant rRNA is crucial for efficient mRNA sequencing, particularly in metatranscriptomic studies where rRNA can constitute over 90% of total RNA. This process is especially challenging for heterogeneous multi-species samples due to differences in prokaryotic and eukaryotic rRNA sequences [11]. While eukaryotic mRNA is typically enriched through poly(A) tail selection, this approach is ineffective for bacterial mRNA lacking poly-A tails.

Universal rRNA depletion methods have been developed to address this challenge, using probe-based hybridization to remove both prokaryotic and eukaryotic rRNAs from total RNA samples. The Zymo-Seq RiboFree Total RNA Library Kit represents one such solution, enabling construction of rRNA-depleted libraries from complex environmental samples [11]. The workflow involves:

- cDNA synthesis from total RNA

- rRNA-cDNA hybrid depletion using universal depletion reagents

- Adapter ligation and amplification with unique dual indices (UDIs)

- Library quantification and sequencing on platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq

This approach has demonstrated minimal rRNA contamination in sequencing data, with effective removal confirmed in silico using tools like SortMeRNA with SILVA database references [11].

Data Analysis Workflow

The computational analysis of microbial transcriptome data follows a structured pipeline with quality control checkpoints at multiple stages [14]:

- Quality Control (QC1): Initial assessment of raw sequencing data using tools like FastQC to identify samples with artefacts or problematic batch effects.

- Data Type Specific Processing: Processing of raw data, including adapter trimming, quality filtering, and alignment to reference genomes or assemblies.

- Data Summarization: Summarization of processed reads to features of interest (e.g., genes, transcripts, contigs).

- Normalization: Removal of technical variation between samples while retaining biological variance, making samples comparable.

- Quality Control (QC2): Identification of issues arising during preprocessing, often using multivariate visualization techniques like PCA.

- Hypothesis Testing: Statistical analysis using moderated methods to prevent type I error inflation in omics analyses.

- Quality Control (QC3): Validation of statistical results through sanity checks and assumption verification.

- Multiple Testing Correction: Adjustment for false discovery rate (FDR) given the large number of simultaneous statistical tests.

For total RNA-seq data, a mapping-based quantification approach has shown superior performance for microbial community analysis. This method involves dividing reads into ssrRNA-origin and other RNA (primarily mRNA) categories, then mapping these reads to annotated assembled contigs or reference databases [12]. This strategy has demonstrated genus-level taxonomic accuracy and quantitatively reproduced mock community compositions with median relative abundance of approximately 10% among ten community members, outperforming standard amplicon-seq approaches [12].

Diagram 1: Microbial Transcriptomics Workflow. The workflow encompasses wet lab procedures (yellow) and bioinformatic analysis (green), highlighting key steps from sample collection to biological interpretation.

Applications and Case Studies

Environmental Microbial Ecology

Metatranscriptomics has revealed how microbial communities drive essential ecosystem processes and respond to environmental change. In arid and semiarid environments, where microbial activity is restricted by low water availability, transcriptomic profiling has uncovered rapid functional responses to simulated humid conditions [9]. Arid soil communities subjected to increased moisture exhibited heightened transcription of pedogenesis-related genes, including those involved in:

- Soil aggregate formation through exopolysaccharide (EPS) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) production

- Phosphorus metabolism and solubilization

- Weathering of minerals via organic acid production and oxidoreduction reactions

- Carbon and nitrogen dynamics, with transcriptional reconfiguration suggesting utilization of available organic resources alongside autotrophy

This functional activation was particularly pronounced in arid sites compared to semiarid sites, which showed greater resilience to moisture changes. Taxonomically, Pseudomonadota and Actinomycetota dominated the transcriptional profiles associated with these early stages of soil development, highlighting their crucial role in pioneering pedogenetic processes under changing climate conditions [9].

Host-Microbe Interactions and Pathogenesis

Transcriptomic approaches have illuminated how pathogens manipulate their gene expression to establish infections, evade host defenses, and exploit host resources. RNA modification reprogramming represents a key strategy employed by diverse pathogens during host adaptation:

- Bacterial pathogens: In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, GidA-dependent cmnm5U tRNA modification modulates expression of virulence regulators, shifting protein translation toward pathogenic physiological states [10]. Similarly, queuosine (Q) modification on tRNA regulates virulence and biofilm formation across diverse bacterial phyla, particularly in human pathogens [10].

- Viruses: HIV-1 utilizes host machinery to introduce m6A modifications at multiple sites across its RNA genome, promoting viral replication and regulating full-length RNA packaging into viral particles [10]. Hepatitis B virus employs m5C modifications in epsilon elements critical for virion production and reverse transcription [10].

- Parasites and fungi: While less extensively characterized, emerging evidence indicates similar exploitation of RNA modification systems in eukaryotic pathogens.

These findings not only advance fundamental understanding of infection biology but also identify potential therapeutic targets for novel anti-infective strategies aimed at disrupting pathogen epitranscriptomic programming.

Drug Discovery and Development

RNA-seq has become an integral tool throughout the drug discovery pipeline, from target identification to mode-of-action studies [3]. In large-scale drug screens, transcriptomic profiling can:

- Identify expression patterns in response to compound treatment

- Reveal differential responses to drug combinations

- Discover biomarkers for patient stratification and treatment response monitoring

- Distinguish primary drug effects from secondary consequences through kinetic studies

Methodologies such as 3'-end sequencing (3'-Seq) enable cost-effective processing of large sample numbers by focusing on the 3' termini of transcripts, often permitting library preparation directly from cell lysates without RNA extraction [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for high-throughput screening applications where quantitative gene expression data rather than complete isoform information is sufficient. For more in-depth investigations of drug effects on splicing, non-coding RNAs, or viral variants, whole transcriptome approaches with mRNA enrichment or ribosomal RNA depletion remain preferable [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Microbial Transcriptomics

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Key Features | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTAB Phenol-Chloroform Extraction | RNA isolation from complex matrices | Effective for clay-rich soils; reduces humic acid contamination; customizable protocol [11] | Optimized for rhizosphere soil; superior to commercial kits for challenging samples |

| Universal rRNA Depletion Kits | Removal of prokaryotic and eukaryotic rRNA | Probe-based hybridization; enables mRNA enrichment without poly-A selection [11] | Zymo-Seq RiboFree Total RNA Library Kit; effective for metatranscriptomics |

| Spike-in Controls | Technical variability assessment; normalization | Artificial RNA sequences; quantitation standards; performance monitoring [3] | SIRVs (Spike-in RNA Variant Control Mixes); assess dynamic range, sensitivity |

| RNA Clean-up Kits | Post-extraction purification | Contaminant removal; DNase treatment; sample concentration [11] | Zymo RNA Clean & Concentrator kits; include DNase I treatment |

| RiboFree Library Prep Kits | rRNA-depleted library construction | cDNA synthesis with rRNA depletion; adapter ligation; index PCR [11] | Zymo-Seq RiboFree Total RNA Library Kit; compatible with Illumina sequencing |

| Mapping-based Quantification | Taxonomic and functional analysis | Uses own reads as reference; superior to amplicon-seq for quantification [12] | ARI-seq; genus-level accuracy; minimal PCR bias |

The microbial transcriptome represents a dynamic landscape of coding, structural, and regulatory RNAs that collectively determine microbial functional potential in diverse environments. While rRNA continues to serve as a valuable phylogenetic marker and rough indicator of cellular ribosome content, its limitations as a precise metric of microbial activity necessitate complementary approaches focusing on mRNA and regulatory RNAs. Advances in RNA extraction, particularly from complex matrices like soil, coupled with effective rRNA depletion strategies and sophisticated bioinformatic pipelines, have dramatically enhanced our ability to characterize microbial community function at unprecedented resolution.

The growing recognition of RNA modifications as key regulatory mechanisms in host-microbe interactions, alongside the discovery of widespread RNA structural switches in bacterial transcriptomes, highlights the expanding complexity of RNA-mediated regulation in microbes [10] [13]. These emerging layers of transcriptional and post-transcriptional control offer exciting avenues for future research and potential therapeutic intervention. As methodologies continue to evolve, particularly in single-cell transcriptomics and spatial mapping of gene expression, our understanding of microbial community dynamics and function will deepen, offering new insights into ecosystem processes, host-pathogen interactions, and biotechnological applications.

Application Note: Measuring the Rhizosphere Effect through RNA Analysis

Theoretical Foundation and Quantitative Assessment

The rhizosphere effect quantifies how plant roots alter soil microbial communities, a phenomenon measurable through advanced RNA analysis. Research comparing Arabidopsis thaliana to eight other plant species revealed that its bacterial rhizosphere effect was approximately 35% lower than the average of the other species, while its fungal effect was a striking 90% lower [15]. However, within the root endosphere, the selective pressure of Arabidopsis was comparable to other species, indicating a specialized relationship with its core microbial partners [15].

RNA-based analysis is critical because it moves beyond census-taking to identify functionally active community members. This is superior to DNA-based methods like 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing, which can detect both active and dormant organisms [8]. Metatranscriptomics captures actively transcribed genes, providing direct insight into microbial functional dynamics and their responses to plant and environmental signals [11].

Quantitative Data from Rhizosphere Studies

Table 1: Quantitative Measures of the Rhizosphere Effect (Arabidopsis vs. Other Species)

| Metric | Arabidopsis thaliana | Average of Eight Other Species | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Rhizosphere Effect | ~35% lower | Baseline (100%) | Number of enriched/depleted bacterial taxa [15] |

| Fungal Rhizosphere Effect | ~90% lower (10% of average) | Baseline (100%) | Number of differentially abundant fungal taxa [15] |

| Endorhizosphere Effect | Comparable | Comparable | Selective pressure for both bacteria and fungi [15] |

| Community Distinctness | Closest to soil cluster | More distinct from soil | PCoA analysis of bacterial communities [15] |

Table 2: Microbial Community Shifts from Bulk Soil to Rhizosphere Compartments

| Microbial Group | Trend from Soil to Rhizosphere | Trend from Soil to Endorhizosphere |

|---|---|---|

| Proteobacteria | Increase | Considerable Increase [15] |

| Actinobacteria | - | Considerable Increase [15] |

| Acidobacteria | - | Reduced [15] |

| Overall Alpha Diversity | No large decrease | Substantial decrease [15] |

Protocol: Metatranscriptomic Analysis of Rhizosphere Microbial Activity

Optimized RNA Extraction from Rhizosphere Soil

Principle: Obtain high-quality, inhibitor-free total RNA from clay-rich rhizosphere soils for downstream sequencing. An optimized CTAB phenol-chloroform protocol significantly improves yield and quality compared to standard commercial kits [11].

Materials:

- CTAB Extraction Buffer

- Water-saturated phenol

- 49:1 Chloroform:Isoamyl alcohol

- 500 mM sodium phosphate (NaP) buffer, pH 5.8

- 2-Mercaptoethanol

- PEG-NaCl precipitation solution

- Silica beads (0.1 mm and 0.5 mm, 19:1 ratio)

- Zymo RNA Clean & Concentrator kits (Cat #R1015)

- DNase I (Zymo Research, Cat #E1010)

Procedure:

- Homogenization: Homogenize 250 mg of flash-frozen rhizosphere soil with silica beads in CTAB extraction buffer, phenol, chloroform:isoamyl alcohol, NaP buffer, and 2-Mercaptoethanol [11].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Recover the aqueous phase [11].

- Organic Extraction: Perform sequential extractions with Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl alcohol and a second Chloroform:Isoamyl alcohol [11].

- Precipitation: Precipitate the RNA from the final aqueous phase with one volume of PEG-NaCl solution. Incubate on ice at 4°C for 20 min and centrifuge at 20,000 g for 20 min at 4°C [11].

- Pellet Washing and Resuspension: Wash the pellet with 70% ice-cold ethanol, air-dry, and resuspend in nuclease-free water [11].

- Purification and DNase Treatment: Further purify the crude RNA using a Zymo RNA Clean & Concentrator kit, including on-column DNase I treatment [11].

Quality Control:

- Quantification: Use a Qubit 4 fluorometer.

- Purity: Assess via NanoDrop (target A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios).

- Integrity: Determine RNA Integrity Number (RINe) using an Agilent 4150 TapeStation system [11].

Universal rRNA Depletion and Library Preparation

Principle: Remove abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) to enable efficient sequencing of messenger RNA (mRNA), allowing for the assessment of functional gene expression.

Materials:

Procedure:

- cDNA Synthesis: Convert 250 ng of total RNA to cDNA [11].

- rRNA Depletion: Treat cDNA with RiboFree Universal Depletion reagents to remove rRNA-cDNA hybrids [11].

- Adapter Ligation and Amplification: Ligate adapters to the remaining cDNA and amplify the library using Zymo-Seq UDI Primers per the manufacturer's protocol [11].

- Library QC and Sequencing: Quantify the final cDNA libraries with a Qubit and sequence on an Illumina NovaSeq platform (e.g., 20 million 150-bp paired-end reads) [11].

Bioinformatics Workflow for Metatranscriptomic Data

The following workflow outlines the key steps for processing sequencing data to analyze microbial activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Rhizosphere Metatranscriptomics

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example Product (if specified) |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB Phenol-Chloroform Solution | Lysis buffer for effective cell disruption and nucleic acid extraction from complex soil matrices. | Custom-made [11] |

| PEG-NaCl Precipitation Solution | Precipitates nucleic acids from the aqueous phase after organic extraction. | Custom-made [11] |

| RNA Clean & Concentrator Kit | Purifies crude RNA extracts, removing contaminants like humic acids, and includes DNase treatment. | Zymo Research, Cat #R1015 [11] |

| Universal rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes prokaryotic and eukaryotic rRNA from total RNA samples, enriching for mRNA. | Zymo-Seq RiboFree Total RNA Library Kit, Cat #R3000 [11] |

| Silica Beads (0.1 & 0.5 mm) | Mechanical homogenization of tough soil and microbial cell walls during lysis. | Various suppliers [11] |

| DNase I Enzyme | Degrades genomic DNA contamination during RNA purification to ensure pure RNA for sequencing. | Zymo Research, Cat #E1010 [11] |

Application in Host-Pathogen Interactions and Drug Discovery

From Ecology to Translation

Understanding microbial activity through RNA analysis bridges fundamental ecology and applied science. In host-pathogen interactions, metatranscriptomics can identify the functional shifts in the rhizosphere that precede disease outbreaks, revealing pathogen activation and the host's defensive microbiome response [11]. This provides targets for preemptive biocontrol strategies.

In drug discovery, the rhizosphere is a reservoir for novel antimicrobial compounds. Microbial warfare via specialized metabolites (e.g., antibiotics) is a key mechanism of interference competition [16]. By analyzing the metatranscriptome, researchers can pinpoint the expression of biosynthetic gene clusters for compounds like novel antibiotics under specific conditions, streamlining the discovery pipeline [17] [16]. This metabolic ecology framework, focused on nutrient competition and bacterial interactions, offers a general principle for understanding and engineering microbiomes across health, agriculture, and environmental contexts [17].

Metatranscriptomics is a powerful molecular technique that sequences the collective messenger RNA (mRNA) from entire microbial communities, providing a real-time snapshot of actively expressed genes and metabolic functions. Unlike metagenomics, which reveals the genetic potential of a microbiome, metatranscriptomics reveals which functions are actively being performed, offering direct insight into microbial community responses to their environment [18] [19].

This Application Note details the distinct advantages of metatranscriptomics and provides established protocols for its application. The content is framed within a broader thesis on RNA analysis, underscoring its critical role in measuring microbial activity for research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Omic Approaches

The table below summarizes how metatranscriptomics complements and enhances other common microbial community profiling techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Microbial Community Profiling Techniques

| Feature | Metatranscriptomics | Metagenomics | 16S rRNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Target | Total mRNA from a community [19] | Total DNA from a community [19] | 16S rRNA gene (DNA) [18] |

| Primary Insight | Active gene expression and metabolic activity [20] | Functional potential and taxonomic composition [21] | Taxonomic composition and diversity [18] |

| Temporal Resolution | High (snapshot of active processes) [19] | Low (stable genetic blueprint) | Low (stable genetic blueprint) |

| Key Advantage | Identifies actively transcribed pathways and community responses [22] | Unbiased view of all encoded functions | Cost-effective for community profiling |

| Main Challenge | RNA instability; host RNA contamination [21] [19] | Does not distinguish active vs. silent genes [21] | Limited functional and taxonomic resolution [18] |

Key Advantages and Research Applications

Metatranscriptomics provides several critical advantages that make it indispensable for modern microbiome research.

Reveals Active Metabolic Pathways in Real-Time: By capturing mRNA, this technique directly identifies which metabolic pathways are actively functioning, moving beyond mere genetic potential. For instance, in a urinary tract infection (UTI) study, metatranscriptomics identified highly expressed virulence genes in E. coli, such as adhesion genes (fimA, fimI) and iron acquisition systems (chuY, iroN), which are critical for host colonization and infection [22].

Unveils Host-Microbiome Interactions: The method allows for the simultaneous profiling of both host and microbial RNA. This integrative approach sheds light on complex communication networks, providing insights into the role of microbial gene expression in health, disease, and host physiology [19].

Captures Dynamic Community Responses: Metatranscriptomics is ideal for monitoring how microbial communities respond to environmental changes, dietary interventions, or disease states over time. This temporal resolution helps researchers understand microbial population dynamics, community resilience, and functional shifts in response to perturbations [19].

Identifies Active Key Taxa: A critical finding across studies is the frequent divergence between microbial abundance (DNA) and activity (RNA). For example, in the skin microbiome, Staphylococcus and Malassezia species often have an outsized contribution to metatranscriptomes despite their modest representation in metagenomes, highlighting them as key active players [21]. Similarly, in aerobic granular sludge, a weak correlation was found between the relative abundance of microbes and their transcriptomic activity, underscoring that abundance does not equate to metabolic importance [23].

Table 2: Selected Case Studies Demonstrating Metatranscriptomic Applications

| Field of Study | Research Objective | Key Metatranscriptomic Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious Disease (UTI) | Characterize active metabolic functions of uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) in patient samples. | Identified highly expressed virulence genes and patient-specific metabolic adaptations in UPEC strains. | [22] |

| Skin Microbiology | Profile active gene expression of the healthy human skin microbiome across body sites. | Revealed that Staphylococcus and Malassezia are highly transcriptionally active; discovered diverse antimicrobial genes (bacteriocins) expressed by commensals. | [21] |

| Wastewater Treatment | Investigate microbial activity patterns in different-sized aggregates of aerobic granular sludge. | Uncovered a weak correlation between microbial abundance and activity; identified distinct functional roles for microbes in flocs vs. granules. | [23] |

| Nutritional Science | Understand gut microbiome metabolism of dietary components like fibres and proteins. | Enabled the capture of active transcripts related to metabolite production (e.g., short-chain fatty acids) that affect gut health. | [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following section outlines a robust, generalized workflow for metatranscriptomic analysis, synthesized from recent studies on human skin [21] and rhizosphere soil [11].

The diagram below illustrates the complete metatranscriptomics workflow, from sample collection to data analysis.

Step-by-Step Protocol

1. Sample Collection and Preservation

- Objective: To obtain microbial biomass while preserving RNA integrity and minimizing host contamination.

- Procedure:

- Collect samples using appropriate methods (e.g., swabs for skin [21], soil cores for rhizosphere [11]).

- Immediately preserve samples in a nucleic acid stabilization reagent (e.g., DNA/RNA Shield) and flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen.

- Store at -80°C until processing. Note: Rapid preservation is critical due to the rapid degradation of mRNA [21] [11].

2. Total RNA Extraction

- Objective: To isolate high-quality, intact total RNA from the complex sample matrix.

- Procedure:

- Use a protocol combining mechanical lysis (e.g., bead beating with silica beads) and chemical lysis (e.g., CTAB-phenol-chloroform) for robust cell disruption [11].

- Purify the crude RNA extract using commercial kits (e.g., Zymo RNA Clean & Concentrator) to remove contaminants like humic acids, proteins, and genomic DNA (using DNase I treatment) [11].

- Quality Control: Assess RNA concentration, purity (A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios via NanoDrop), and integrity (RNA Integrity Number (RINe) using an Agilent TapeStation) [21] [11].

3. rRNA Depletion and mRNA Enrichment

- Objective: To remove highly abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which can constitute >90% of total RNA, to enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA).

- Procedure:

- Use probe hybridization-based kits designed for universal rRNA depletion (e.g., riboPOOLs, Zymo-Seq RiboFree Total RNA Library Kit) [18] [21] [11]. These kits use oligonucleotides that bind to rRNA from a wide range of prokaryotes and eukaryotes, which is then degraded or removed.

- Note: Unlike eukaryotic mRNA, prokaryotic mRNA lacks a poly-A tail, so oligo(dT)-based enrichment cannot be used [18].

4. Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Objective: To convert the enriched mRNA into a sequencing library.

- Procedure:

- Reverse-transcribe the mRNA into double-stranded cDNA using random hexamer primers [18].

- Fragment the cDNA, ligate sequencing adapters, and amplify the library using index primers for multiplexing.

- Sequence the library on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq) to generate a minimum of 20-30 million paired-end (e.g., 2x150 bp) reads per sample for sufficient coverage [21] [22] [24].

5. Bioinformatic Analysis

- Objective: To process raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful information about active taxa and functions.

- Procedure:

- Quality Control & Trimming: Use FastQC for quality assessment and tools like Trimmomatic or BBMAP to remove adapters and low-quality bases [18] [11].

- Host Read Removal: Align reads to the host genome (e.g., human, soybean) using STAR or BWA and remove matching reads [21] [11].

- rRNA Filtering: Remove residual rRNA sequences using SortMeRNA with Silva database references [18] [11].

- Assembly & Gene Prediction: Assemble high-quality, non-rRNA reads into transcripts using a metatranscriptomic assembler like IDBA-MT or rnaSPAdes [18] [11].

- Taxonomic & Functional Annotation: Classify transcripts taxonomically using Kraken2 or Kaiju [18]. Annotate gene functions by aligning transcripts to protein databases (e.g., UniRef, KEGG) using DIAMOND [18] [11].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Quantify transcript abundances and identify significantly differentially expressed genes between conditions using tools like DESeq2 or EdgeR [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and kits critical for a successful metatranscriptomic study.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Metatranscriptomics

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples (from search results) |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Preservation Reagent | Stabilizes RNA at the point of collection to prevent degradation. | DNA/RNA Shield [21] |

| Bead Beating Tubes | Mechanical cell lysis for robust extraction from tough microbial cell walls and soil. | Tubes with 0.1 mm and 0.5 mm silica beads [11] |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Purifies high-quality total RNA, free of contaminants like humics and gDNA. | Zymo RNA Clean & Concentrator kits; CTAB-phenol-chloroform method [11] |

| Universal rRNA Depletion Kit | Selectively removes rRNA to enrich for mRNA. Critical for prokaryote-dominated samples. | riboPOOLs, Zymo-Seq RiboFree Total RNA Library Kit [18] [21] [11] |

| Library Prep Kit | Prepares rRNA-depleted RNA for Illumina sequencing. | SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq Kit; Zymo-Seq RiboFree Total RNA Library Kit [18] [11] |

Metatranscriptomics has emerged as a fundamental tool for moving beyond the census of microbial communities to understanding their active functions and dynamic responses. The protocols and advantages outlined in this Application Note provide a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design robust studies that uncover the critical, active roles microbes play in human health, disease, and environmental ecosystems. When integrated with other multi-omic data, metatranscriptomics offers an unparalleled view into the functional state of microbial communities.

From Sample to Sequence: Optimized RNA-Seq Workflows for Complex Microbial Samples

RNA analysis is a powerful tool for measuring microbial activity, providing insights into functional gene expression and active community members in diverse environments. However, obtaining high-quality RNA for downstream analyses is fraught with technical challenges. Three significant hurdles consistently complicate microbial RNA extraction: the co-purification of inhibitory substances like humic acids, the pervasive threat of RNase degradation, and the limited yield from low-biomass samples [25] [26]. The inherent fragility of RNA and the diverse structural composition of microbial cells further necessitate optimized, robust protocols. This Application Note details these primary challenges and provides validated, detailed methodologies to overcome them, ensuring the recovery of intact, pure RNA for accurate assessment of microbial activity.

The Core Challenges in Microbial RNA Extraction

Humic Acid Interference

Humic substances are complex organic polymers formed from the decomposition of plant and microbial matter. While naturally abundant in soil, water, and sediments, they pose a significant problem for RNA extraction. Their chemical structure, rich in phenolic and carboxylic functional groups, allows them to co-purify with nucleic acids, acting as potent inhibitors in downstream enzymatic reactions like reverse transcription and PCR [27]. Their brown-black color also interferes with spectrophotometric quantification of RNA. Critically, their polyanionic nature enables them to bind to positively charged viral glycoproteins, which, while the basis for their reported antiviral activity, can also interfere with the detection and analysis of RNA viruses in environmental samples [27].

RNase Degradation

Unlike DNA, RNA is single-stranded and features a reactive 2'-hydroxyl group on its ribose sugar, making it inherently susceptible to base-catalyzed hydrolysis. This chemical instability is compounded by the ubiquitous presence of ribonucleases (RNases), enzymes that rapidly degrade RNA [28] [29]. RNases are exceptionally durable; they are found on skin, in dust, and on surfaces, and do not require co-factors to function, meaning they can remain active even after autoclaving [29]. A single introduction of RNase contamination can devastate an RNA sample, leading to fragmented, unreliable data. Therefore, a paramount concern in any RNA workflow is maintaining an RNase-free environment.

Low Microbial Biomass

Many microbial niches, such as the human respiratory tract, deep subsurface environments, and clean-room facilities, are characterized by low microbial biomass. Extracting sufficient RNA from such samples for sequencing is highly challenging. The low absolute amount of microbial RNA is often dwarfed by host or environmental RNA, requiring extremely high sequencing depth to achieve adequate coverage of the microbial transcriptome [25] [26]. This amplifies the impact of any inhibitors or degradation, as the already faint microbial signal can be easily lost. Furthermore, standard extraction protocols often fail to lyse robust microbial cells (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria, fungi) efficiently in these samples, leading to a biased representation of the active community [25].

Optimized Protocols for Challenging Samples

The following protocols have been specifically selected and optimized to address the intertwined challenges of humic acids, RNases, and low biomass.

Comprehensive RNA Extraction from Low-Biomass Respiratory Samples

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study on the respiratory microbiome, is designed for maximal recovery of microbial RNA from sample types like nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) [25]. It is particularly effective for lysing tough microbial cells.

- Sample Preparation: Pooled human NPS or BAL samples, stored in transport medium, were used in the original study. Ensure all collection tubes are RNase-free.

- Lysis Method: The key to success is using a kit that combines Chemical and Mechanical Lysis (CML). The Quick-DNA/RNA Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo Research) was used with bead beating to physically disrupt robust cell walls of gram-positive bacteria and fungi [25].

- Optimized Steps:

- Use an increased input volume of 400 µL (instead of the standard 200 µL) to maximize yield from low-biomass samples.

- Perform all steps in duplicate to improve robustness.

- Include a DNase treatment step using TURBO DNase (Invitrogen) directly on the extraction column or eluate to remove genomic DNA contamination [25].

- Critical Notes: This CML protocol significantly outperformed chemical lysis-only methods, yielding higher sequencing reads and enhancing the detection of gram-positive bacteria and fungi without compromising viral detection [25].

RNA Extraction from Low-Biomass Autotrophic Bacteria

Developed for volume-limited cultures of autotrophic bacteria, this protocol emphasizes high-quality RNA yield suitable for RNA-seq [26].

- Sample Preparation: Bacterial cultures of Nitrosomonas europaea and Nitrobacter winogradskyi were used. Concentrate cells by centrifugation from a sufficient culture volume.

- Lysis Method: Enzymatic lysis using lysozyme digestion. This method was found to generate higher quality RNA compared to ultrasonication, which can degrade RNA [26].

- Optimized Steps:

- Begin with a standard commercial silica-column based kit protocol.

- Amend the initial lysis step with a dedicated incubation with lysozyme to gently but effectively break down the bacterial cell wall.

- Proceed with the kit's standard binding, washing, and elution steps.

- Critical Notes: This method is ideal for experiments where sample volume and/or biomass is limited, as it avoids the RNA shearing associated with harsh physical lysis methods [26].

General Best Practices for an RNase-Free Environment

These precautions are non-negotiable for all RNA work and should be integrated into every protocol [28] [29].

- Personal Equipment: Always wear gloves and change them frequently. Avoid touching skin, hair, or any potentially contaminated surfaces with gloved hands.

- Workspace: Designate a special area for RNA work only. Before starting, clean the bench and equipment with a commercial RNase-inactivating agent like RNaseZap or a solution of SDS and ethanol [28] [29].

- Consumables: Use sterile, disposable plasticware (tubes, tips), which are typically RNase-free. Always use filter tips to prevent aerosol contamination of pipettors [28].

- Liquid Reagents: Use only RNase-free water (e.g., DEPC-treated and autoclaved) for making solutions. Dedicate separate reagents for RNA work. Note that Tris buffers cannot be decontaminated with DEPC and should be made from a reserved, RNase-free stock [29].

- Sample Handling: Keep samples on ice whenever possible to slow RNase activity. For long-term storage, preserve RNA at -70 °C to -80 °C as ethanol precipitates or in RNase-free buffer [29].

Essential Reagents and Solutions

The table below summarizes key reagents and their roles in overcoming extraction challenges.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial RNA Extraction

| Reagent/Kit | Function/Role | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Quick-DNA/RNA Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo Research) | Combined chemical & mechanical lysis (CML) | Effectively disrupts robust gram-positive bacterial and fungal cell walls in low-biomass samples [25]. |

| Lysozyme | Enzymatic lysis agent | Gently digests bacterial cell walls, providing high-quality RNA suitable for RNA-seq from low-biomass cultures [26]. |

| TURBO DNase (Invitrogen) | DNA digestion | Removes contaminating genomic DNA without compromising RNA integrity, critical for metatranscriptomics [25]. |

| Protector RNase Inhibitor (Roche) | RNase inhibition | Protects RNA from a broad spectrum of RNases during isolation and downstream applications like reverse transcription [29]. |

| RNaseZap / DEPC-treated Water | RNase decontamination | Creates an RNase-free environment for workspace (RNaseZap) and aqueous solutions (DEPC-water) [28] [29]. |

| NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit (NEB) | Ribosomal RNA removal | Enriches for messenger RNA by depleting host and microbial rRNA, greatly improving sequencing depth of informative transcripts [25]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard (Zymo Research) | Positive control | Validates extraction efficiency and sequencing performance across a defined mix of bacterial and fungal cells [25]. |

Quantitative Data Comparison

The following table summarizes performance metrics from key studies, illustrating the impact of different optimization strategies.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of RNA Extraction Optimizations

| Extraction Method / Strategy | Sample Type | Key Outcome Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical + Mechanical Lysis (CML) | Human Respiratory (BAL, NPS) | - Significantly higher dsDNA library yields and sequencing read counts (p < 0.0001).- Enhanced detection of gram-positive bacteria and fungi. [25] | [25] |

| Chemical Lysis (CL) Only | Human Respiratory (BAL, NPS) | Lower yields and microbial detection compared to CML, potential bias against robust cells. [25] | [25] |

| Enzymatic Lysis (Lysozyme) | Low-biomass Autotrophic Bacteria | Generated high-quality, high-yield RNA suitable for downstream RNA-seq analysis. [26] | [26] |

| Ultrasonication Lysis | Low-biomass Autotrophic Bacteria | Resulted in high RNA yield but low RNA quality, making it less suitable for sensitive applications. [26] | [26] |

| Silica Beads with Phenol-Chloroform (NS2) | Raw Wastewater | - Higher SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection than silica columns (p < 0.0001).- Effective RT-qPCR inhibitor removal. [30] | [30] |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Strategic Workflow for RNA Extraction

The diagram below outlines the critical decision points and pathways for selecting the optimal RNA extraction strategy based on sample-specific challenges.

RNase Control Pathway

This diagram illustrates the parallel pathways required for successful RNase control, encompassing both the laboratory environment and the sample itself.

Successful RNA analysis for measuring microbial activity hinges on overcoming the technical barriers of humic acid interference, RNase degradation, and low biomass. As detailed in this Application Note, a one-size-fits-all approach is inadequate. Researchers must instead select and optimize their extraction protocols based on the specific sample matrix and research question. The integration of robust mechanical lysis for tough cells, enzymatic treatments for gentle and effective disruption, inhibitor-removal steps, and scrupulous RNase-free technique provides a comprehensive strategy to recover high-quality RNA. By implementing these validated protocols and best practices, researchers can ensure that the microbial activity data they generate is both accurate and reliable, forming a solid foundation for advanced research in drug development, environmental microbiology, and human health.

Within the context of microbial activity measurement research, obtaining high-quality RNA from environmental samples is a critical first step for techniques like metatranscriptomics, which reveal the active functional roles of soil microbes [11]. Clay-rich soils present a significant challenge for nucleic acid extraction due to the strong adsorption of RNA to clay particles and the co-purification of potent enzymatic inhibitors like humic substances [31] [32]. Standard protocols often yield degraded RNA or extracts unsuitable for downstream applications [33] [32].

The cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) phenol-chloroform method is a robust, in-house technique that allows for the flexibility needed to overcome these challenges. This protocol details a optimized CTAB-based approach, specifically tailored for clay-rich soils, that significantly improves RNA yield and purity by incorporating key steps such as a sodium phosphate buffer wash and PEG-based precipitation [11] [33]. The resulting high-quality RNA is ideal for sensitive downstream analyses, including quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) and next-generation sequencing, providing a reliable tool for studying microbial activity in soil environments [31] [11].

Key Reagents and Equipment

The following table lists the specialized solutions and equipment required to successfully execute this protocol.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| CTAB Extraction Buffer | A cationic detergent buffer that facilitates cell lysis and separation of polysaccharides and polyphenols from nucleic acids [34]. |

| Sodium Phosphate (NaP) Buffer | Helps to displace clay-adsorbed RNA through ion exchange, dramatically improving yield from clay-rich matrices [35] [11]. |

| Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVP) | Binds to and removes phenolic compounds (e.g., humic acids) that are common PCR inhibitors in soil [35] [32]. |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | A reducing agent added to the lysis buffer to inhibit RNases and prevent RNA degradation [11]. |

| PEG-NaCl Precipitation Solution | Used as an alternative to alcohol precipitation to improve RNA recovery and simultaneously remove carry-over pigmentation [35] [33]. |

| Silica Spin Column | Used for final purification to concentrate the RNA and remove residual salts and contaminants [11]. |

| Bead Beater | Provides mechanical lysis via rapid shaking with silica/zirconia beads, essential for disrupting robust microbial cell walls [11] [25]. |

Method

The diagram below illustrates the complete experimental workflow for RNA extraction and validation from clay-rich soil.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Soil Sample Preparation and Pre-treatment

- Begin with 250 mg of freeze-dried, homogenized clay-rich soil [11]. Use a swing mill with tungsten carbide beads to pulverize the sample for 1 minute to further disrupt soil aggregates [35].

- Critical: For soils with very high clay content (>40%), a pre-wash with 500 µL of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) can be beneficial. Vortex thoroughly, centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 5 min, and discard the supernatant. This step helps elute humic substances and initiates the displacement of clay-adsorbed RNA [35] [33].

Step 2: Combined Chemical and Mechanical Lysis

- To the pre-washed pellet, add:

- Homogenize the mixture using a bead beater (e.g., FastPrep) with a lysing matrix containing 0.1 mm and 0.5 mm silica beads. Process at 6 m/s for 45-60 seconds [31] [11].

- Incubate the homogenate at 65°C for 10 minutes with occasional inversions to ensure thorough chemical lysis [35].

Step 3: Organic Phase Separation and Nucleic Acid Recovery

- Centrifuge the lysate at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate soil debris [11].

- Transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube. Add an equal volume of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), vortex thoroughly, and centrifuge again [11] [34].

- Transfer the aqueous phase and perform a second extraction with an equal volume of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1) to remove residual phenol [35] [11].

Step 4: Precipitation and Purification of RNA

- To the final aqueous phase, add 0.7 volumes of PEG-NaCl precipitation solution (e.g., 20-30% PEG 6000, 5 M NaCl) instead of traditional isopropanol. Incubate on ice for 20 minutes [11] [33]. This step is highly effective at removing pigmentation.

- Centrifuge at 20,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C to pellet the RNA. Wash the pellet with 500 µL of ice-cold 70% ethanol, air-dry, and resuspend in nuclease-free water [11].

- Further Purification: Pass the resuspended RNA through a silica spin column (e.g., Zymo RNA Clean & Concentrator). Perform an on-column DNase I digestion (1 U/µL) to remove contaminating genomic DNA [11]. Elute in 20-50 µL of nuclease-free water.

Expected Results and Quality Control

When optimized, this protocol yields RNA suitable for the most sensitive downstream applications. The table below summarizes typical performance metrics and benchmarks.

Table 2: Expected RNA Yield and Quality Metrics from Clay-Rich Soils

| Parameter | Target Value | Measurement Technique | Significance for Downstream Apps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total RNA Yield | >100 ng/µL (from 250 mg soil) | Qubit Fluorometer | Sufficient quantity for library prep (e.g., 250 ng input) [11]. |

| Purity (A260/A280) | 1.8 - 2.1 | NanoDrop Spectrophotometer | Indicates minimal protein contamination [33]. |

| Purity (A260/A230) | >1.8 | NanoDrop Spectrophotometer | Indicates removal of humics, salts, and other organics [33]. |

| RNA Integrity (RINe) | ≥7.0 | Agilent TapeStation | Confirms RNA is not degraded; essential for sequencing [11] [33]. |

| qRT-PCR Suitability | Cq < 30 for 16S rRNA | Quantitative RT-PCR | Validates RNA is free of inhibitors and functionally intact [31] [32]. |

Application Notes

Downstream Molecular Applications

The high-quality RNA extracted via this protocol enables a range of advanced techniques for profiling active microbial communities.

- Metatranscriptomic Sequencing: For Illumina sequencing, use 250 ng of total RNA. Employ a universal rRNA depletion kit (e.g., Zymo-Seq RiboFree) to remove both prokaryotic and eukaryotic rRNA, dramatically increasing the proportion of informative mRNA reads [11]. This allows for the assembly and annotation of active microbial transcripts.

- Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR): The extracted RNA is free from PCR inhibitors, making it directly suitable for sensitive qRT-PCR assays targeting functional genes (e.g., hcnC) or phylogenetic markers like 16S rRNA to quantify specific active microbial populations [31].

Distinguishing Microbial Activity from Presence

A key application in microbial ecology is differentiating the active from the total microbial community. This is conceptually achieved by comparing RNA-based and DNA-based community profiles.

Table 3: DNA vs. RNA Based Microbial Community Analysis

| Analysis Type | Target Molecule | What It Reveals | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-Based Community Profiling | 16S rRNA gene (DNA) | Total microbial membership: includes active, dormant, and dead cells [36]. | May overrepresent dormant populations (e.g., Saccharibacteria) and underestimate active root associates [36]. |

| RNA-Based Community Profiling (PSP) | 16S rRNA transcript (RNA) | Protein Synthesis Potential (PSP): identifies the potentially active fraction of the community [36]. | More sensitive to environmental changes; reveals fine-scale differences (e.g., enrichment of Comamonadaceae in rhizosphere) [36]. |

Troubleshooting

- Low RNA Yield: Increase the sodium phosphate buffer concentration to 1 M in the lysis buffer to better compete with clay particles for RNA binding [35]. Ensure bead-beating is performed at sufficient speed and duration.

- Brown Pigmentation (Humics): If a brown color persists, repeat the PEG precipitation step or use a higher concentration (30% PEG). Ensure PVP is fresh and included in the CTAB buffer [33] [32].

- RNA Degradation: Always work on ice and use fresh β-mercaptoethanol. Pre-chill centrifuges. Process samples quickly or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen after collection [11].

- DNA Contamination: Ensure the DNase I digestion is performed on a silica column for maximum efficiency. Include a "no-RT" control in downstream qRT-PCR assays to check for gDNA contamination [31] [11].

The study of host-microbe interactions represents a frontier in understanding health, disease, and ecosystem function. These complex biological systems, known as holobionts, require analytical approaches that can simultaneously capture transcriptional activity from all symbiotic partners. RNA sequencing has emerged as a powerful tool for this purpose, yet a significant technical challenge persists: the efficient enrichment of messenger RNA from both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells within the same sample [37].

Ribosomal RNA dominates cellular RNA content, comprising approximately 80-90% of total RNA in both bacterial and eukaryotic cells [38] [39]. This abundance poses a substantial barrier to mRNA sequencing, as rRNA reads can consume the majority of sequencing depth and resources. While polyadenylated (polyA) RNA selection effectively enriches eukaryotic mRNA by targeting the polyA tail, this approach fails to adequately capture bacterial transcripts due to fundamental biological differences in RNA processing and stability [37] [39].

This Application Note establishes universal rRNA depletion as a critical methodological foundation for dual RNA-sequencing in mixed prokaryotic-eukaryotic communities. We present quantitative comparisons of methodological approaches, detailed protocols, and practical implementation strategies to enable comprehensive transcriptomic profiling in holobiont systems.

The Technical Challenge of Holobiont Transcriptomics

Fundamental Differences in Eukaryotic and Prokaryotic RNA Biology

The core challenge in simultaneous host-microbe transcriptomics stems from fundamental differences in RNA biology between these domains of life:

- Eukaryotic mRNA: Characterized by relatively long half-lives (several hours) and stable polyA tails (~250 nucleotides) that facilitate enrichment via oligo(dT) capture [37].

- Bacterial mRNA: Features short half-lives (minutes) and transient, short polyA tails (<50 nucleotides) that tag transcripts for degradation rather than stabilization [37].

These differences render polyA enrichment ineffective for bacterial transcript capture, as demonstrated in a study of the marine sponge Amphimedon queenslandica holobiont, where polyA enrichment performed poorly for bacterial symbiont transcriptomes compared to rRNA depletion methods [37].

Methodological Limitations in Mixed Samples

In infection models or symbiotic systems, bacterial RNA can represent less than 1% of total RNA, with eukaryotic ribosomal RNA constituting up to 98% of the remaining material [40]. This imbalance necessitates highly efficient rRNA removal to achieve sufficient sequencing depth for bacterial transcripts without prohibitive sequencing costs.

Comparative Performance of rRNA Depletion Methods

rRNA Depletion Versus PolyA Enrichment

Direct comparison of rRNA depletion and polyA enrichment methods reveals distinct performance characteristics and trade-offs:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of PolyA Enrichment vs. rRNA Depletion for RNA-seq

| Parameter | PolyA Enrichment | rRNA Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| Eukaryotic mRNA Capture | Excellent | Excellent |

| Bacterial mRNA Capture | Poor | Excellent |

| Required Sequencing Depth | Lower | Higher (50-220% more for equivalent exonic coverage) |

| Intronic Read Capture | Minimal | Substantial (up to 50% of reads in blood samples) |

| Non-coding RNA Detection | Limited to polyA+ ncRNA | Comprehensive (lncRNA, snoRNA, etc.) |

| Performance with Degraded RNA | Poor | Good |

| Applicability to Holobiont Studies | Limited | Ideal |

Research comparing both methods on human blood and colon samples demonstrated that rRNA depletion captured a wider diversity of unique transcriptome features, while polyA selection provided higher exonic coverage and better accuracy for gene quantification [41]. For the same level of exonic coverage in blood-derived RNA, rRNA depletion required 220% more sequencing reads compared to polyA selection, and 50% more reads for colon tissue [41].

Efficiency of Commercial rRNA Depletion Kits

Various commercial rRNA depletion kits employ different technologies with varying efficiencies:

Table 2: Comparison of Commercial rRNA Depletion Approaches

| Kit/Method | Technology | Efficiency | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RiboZero (discontinued) | Probe hybridization & magnetic bead capture | High (gold standard) | Discontinued in 2018; pan-prokaryotic |

| riboPOOLs | Species-specific biotinylated probes & magnetic capture | Similar to RiboZero [42] | Species-specific designs available |

| RiboMinus | Probe hybridization & magnetic separation | Moderate [42] | Pan-prokaryotic |