Mastering Thermal Cycling Protocol Modification: A Sensitive Guide for Precision in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical sensitivity of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) thermal cycling protocols.

Mastering Thermal Cycling Protocol Modification: A Sensitive Guide for Precision in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical sensitivity of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) thermal cycling protocols. It explores the foundational impact of temperature and time on DNA amplification, details advanced methodological modifications like VPCR and touchdown PCR, offers systematic troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and validates optimization strategies through comparative analysis. The content synthesizes current knowledge to empower scientists to achieve superior experimental outcomes in diagnostics and molecular biology through precise thermal protocol adjustments.

The Core Principles: How Thermal Cycling Parameters Dictate PCR Success

In the realm of molecular biology, the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) stands as a foundational technique, pivotal for applications ranging from basic research to drug development. Its power lies in the precise thermal cycling of three fundamental steps—denaturation, annealing, and extension—to exponentially amplify specific DNA sequences. Research into thermal cycling protocol modification sensitivity reveals that minute adjustments in temperature, timing, and cycle number can profoundly impact amplification efficiency, specificity, and yield. This technical support center is designed to guide researchers through the intricacies of these steps, providing targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to ensure experimental success in sensitive research contexts.

The Core Principles: A Step-by-Step Technical Guide

Denaturation

The denaturation step involves heating the reaction mixture to a high temperature, typically between 94–98°C, to separate double-stranded DNA into single strands. This provides the necessary template for primers to bind in subsequent steps [1] [2] [3].

- Function: Separates double-stranded DNA into single strands by breaking hydrogen bonds between complementary bases [3].

- Typical Conditions: 94–98°C for 10–60 seconds per cycle, with an initial, longer denaturation of 1-3 minutes at the start of PCR to ensure complete separation of complex DNA [1] [4].

- Sensitivity Note: Incomplete denaturation is a common source of failure. DNA with high GC content (>65%) or strong secondary structures often requires higher temperatures or longer times for complete denaturation [1] [5]. Conversely, excessive denaturation can degrade template DNA and reduce enzyme activity over many cycles [6].

Annealing

Following denaturation, the reaction temperature is lowered to between 50–65°C for the annealing step. This allows the primers to bind, or anneal, to their complementary sequences on the single-stranded DNA templates [1] [2] [7].

- Function: Facilitates the specific binding of primers to their target sequences on the single-stranded DNA template [3].

- Typical Conditions: 30 seconds to 2 minutes at a temperature 3–5°C below the primer's melting temperature (Tm) [1] [5] [7].

- Sensitivity Note: The annealing temperature is the most critical parameter for specificity. A temperature too low can result in non-specific binding and off-target amplification, while a temperature too high can prevent primer binding, leading to low or no yield [1] [5] [7]. Tm can be calculated using formulas that consider primer length, GC content, and salt concentration [1] [2].

Extension

During the extension step, the temperature is raised to the optimal range for the DNA polymerase, typically 70–75°C. The enzyme synthesizes a new DNA strand by adding nucleotides to the 3' end of the annealed primer [1] [3].

- Function: DNA polymerase synthesizes a new DNA strand complementary to the template by adding nucleotides to the 3' end of the annealed primer [3].

- Typical Conditions: The time required depends on the length of the DNA target and the synthesis rate of the polymerase. A common guideline is 1 minute per 1000 base pairs for Taq DNA polymerase [1] [8] [7].

- Sensitivity Note: Using a "slow" polymerase or amplifying long targets without a sufficient extension time will result in incomplete products [1]. For amplicons longer than 10 kb, reducing the extension temperature (e.g., to 68°C) can help maintain enzyme stability over the longer duration [5].

Table 1: Standard Thermal Cycling Parameters for a Three-Step PCR Protocol

| Step | Temperature Range | Time Range | Sensitive Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturation | 94–98°C | 10–60 seconds (cycle); 1–3 minutes (initial) | Temperature, time, GC content of template |

| Annealing | 50–65°C | 30 seconds – 2 minutes | Temperature (must be optimized relative to Tm) |

| Extension | 70–75°C | 1 min/kb (target-dependent) | Time, polymerase synthesis rate, amplicon length |

| Final Extension | 70–75°C | 5–15 minutes | Time (critical for complete products and A-tailing) |

The relationship between these steps and their parameters is a tightly controlled process. The following workflow illustrates the procedural logic and key decision points that can lead to common experimental issues.

Troubleshooting Guide: Connecting Symptoms to Step-Specific Solutions

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common PCR Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes Related to Fundamental Steps | Recommended Solutions & Protocol Modifications |

|---|---|---|

| No or Low Amplification | • Denaturation: Incomplete, especially with GC-rich templates [1].• Annealing: Temperature too high [5] [9].• Extension: Time too short for amplicon length or polymerase speed [1] [9].• Cycles: Insufficient number of cycles for low-copy templates [1] [9]. | • Increase denaturation time/temperature for GC-rich DNA [1] [5].• Lower annealing temperature in 2°C increments [5] [9].• Increase extension time (e.g., 1 min/kb + 1 min) [8].• Increase cycle number up to 40 for low-abundance targets [1] [9]. |

| Non-specific Bands (Multiple Bands) | • Annealing: Temperature too low [5] [9].• Cycles: Too many cycles leading to spurious product accumulation [1] [5]. | • Increase annealing temperature in 2°C increments [5] [9].• Use a Hot-Start DNA polymerase [5] [4].• Reduce the number of cycles [5] [9].• Consider Touchdown PCR [5] [9]. |

| Smear of Bands on Gel | • Annealing: Temperature too low, leading to non-specific priming [9].• Template: Too much template DNA or degraded template [5] [8].• Cycles: Excessive number of cycles ("over-PCR") [8]. | • Increase annealing temperature [9].• Reduce the amount of input template [5] [9].• Reduce the number of cycles [5] [9].• Check template DNA integrity [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Research Scientists

Q1: How do I determine the correct annealing temperature for a new primer set?

A: The annealing temperature (Ta) is primarily based on the primer melting temperature (Tm). Begin by calculating the Tm of each primer using the formula: Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T) or, more accurately, using the nearest-neighbor method available in online tools [1] [10]. Start with an annealing temperature 3–5°C below the lowest Tm of the primer pair [1] [5]. For precise optimization, use a thermal cycler with a gradient function to test a range of temperatures simultaneously [1] [7].

Q2: My target is GC-rich (>70%). What specific modifications to the fundamental steps should I prioritize? A: GC-rich sequences are challenging due to their high thermodynamic stability. Implement a multi-pronged approach:

- Denaturation: Increase the temperature (e.g., to 98°C) and/or duration of the denaturation step [1] [5].

- Additives: Include PCR enhancers such as DMSO (1-10%), formamide, or betaine in the reaction mix to help destabilize the double-stranded DNA [1] [5] [4].

- Polymerase: Choose a polymerase with high processivity and affinity for difficult templates [5].

Q3: How does the choice of DNA polymerase influence the parameters of the extension step? A: Different DNA polymerases have varying characteristics that directly impact extension:

- Synthesis Rate: "Fast" enzymes may require seconds/kb, while "slow" enzymes require up to 2 minutes/kb [1].

- Fidelity: High-fidelity polymerases often have proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity but may be slower, requiring longer extension times [4].

- Thermostability: Highly thermostable enzymes (e.g., from archaea) are less likely to denature during prolonged cycling, maintaining activity better in long extensions [1].

Q4: What is the purpose of a "Final Extension" step and when is it critical? A: The final extension step (typically 5-15 minutes at the extension temperature) ensures that all PCR products are fully synthesized and double-stranded [1]. This step is crucial for:

- Cloning: A 30-minute final extension is often recommended when using Taq polymerase to ensure proper addition of a single 'A' overhang for TA cloning [1].

- Complex/Long Amplicons: It improves the yield of full-length products, especially for long or difficult templates [1] [5].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for PCR Optimization and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function | Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by remaining inactive until the initial high-temperature denaturation step [5] [4] [7]. | Essential for improving specificity. Available as antibody-inhibited or chemically modified enzymes. |

| Mg²⁺ Ions (MgCl₂/MgSO₄) | Acts as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity [4] [10]. | Concentration (typically 1.5-2.5 mM) is critical; too little reduces yield, too much increases non-specificity and error rate [5] [10]. |

| PCR Additives (DMSO, BSA, Betaine) | Assist in amplifying difficult templates by reducing secondary structures, lowering Tm, and neutralizing inhibitors [1] [5] [4]. | Use at recommended concentrations (e.g., DMSO at 1-10%). Require re-optimization of annealing temperature as they can weaken primer binding [5]. |

| dNTP Mix | The building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for new DNA synthesis [4] [10]. | Use balanced equimolar concentrations (typically 200 μM of each). Unbalanced dNTPs increase error rate and can inhibit amplification [5]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimization of Annealing Temperature Using a Gradient Thermal Cycler

Objective: To empirically determine the optimal annealing temperature for a new primer set to maximize yield and specificity.

Background: Calculated Tm values are a starting point, but the true optimal annealing temperature can vary due to buffer composition, enzyme, and template. This protocol is a core methodology in thermal cycling sensitivity research [1] [7].

Materials:

- Prepared PCR master mix (excluding primers, per manufacturer's instructions)

- Forward and reverse primers (20 μM stock each)

- Template DNA

- Gradient thermal cycler

- Gel electrophoresis equipment

Methodology:

- Prepare Reaction Mix: Create a master mix containing all standard PCR components: buffer, dNTPs, Mg²⁺, DNA polymerase, template, and water.

- Aliquot and Add Primers: Aliquot the master mix into individual PCR tubes. Add the same volume of primer pair to each tube.

- Program Thermal Cycler: Set up the PCR protocol with the following steps:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 2 minutes.

- Cycling (35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 98°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: GRADIENT from 50°C to 65°C for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute/kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C.

- Execute PCR: Place the tubes in the thermal cycler, ensuring they are arranged according to the block's gradient profile.

- Analyze Results: Run the PCR products on an agarose gel. Identify the annealing temperature that produces the strongest, single band of the expected size with the least background smearing or non-specific bands [1].

Core Concepts: The Mechanism of Temperature Sensitivity

Why is the annealing temperature so critical for PCR specificity?

The annealing temperature determines the stringency of primer-template binding. This stringency acts as a molecular filter during the reaction:

- Too Low (<3-5°C below Tm): Permits non-specific binding where primers anneal to partially complementary sequences, leading to amplification of off-target products and primer-dimer formation [7].

- Too High (>3-5°C below Tm): Reduces binding efficiency to the specific target, resulting in significantly lower product yield or complete amplification failure [7] [11].

- Optimal Range (3-5°C below Tm): Creates the ideal balance where primers bind efficiently to perfect complements while rejecting sequences with mismatches [12].

Even minor 2°C deviations from this optimal range disrupt this balance, directly impacting assay specificity and efficiency [7].

What are the kinetic requirements for each PCR stage?

Recent research has quantified the precise time requirements for each PCR stage, explaining why temperature precision directly affects reaction kinetics [13]:

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Time Requirements for PCR Stages

| PCR Stage | Minimum Required Time | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Denaturation | 200-500 ms above threshold temperature [13] | Template GC-content, secondary structures [7] |

| Annealing | 300-1000 ms below threshold temperature [13] | Primer concentration, length, and Tm [12] |

| Extension | ~1 second per 70 bp (for KlenTaq polymerase) [13] | Polymerase type and processivity, amplicon length [7] |

The relationship between these parameters and final PCR outcomes can be visualized in the following workflow:

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnostic and Resolution Strategies

How do I diagnose temperature-related PCR failures?

Analyze your amplification results against the following common symptoms to identify the likely cause:

Table 2: Troubleshooting PCR Temperature-Related Issues

| Observed Result | Likely Temperature Issue | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| No product or faint bands | Annealing temperature too high; Incomplete denaturation [7] [11] | Cq values very high or undetectable [11] |

| Multiple bands or smearing | Annealing temperature too low [7] | Non-specific amplification products visible on gel [7] |

| Primer-dimer formation | Annealing temperature too low [11] | Short, unwanted products amplified due to low stringency [11] |

| Inconsistent yields between replicates | Poor thermal block uniformity [14] | Well-to-well temperature variations exceeding ±0.5°C [14] |

What are the most effective methods to optimize thermal conditions?

Systematic Annealing Temperature Optimization

- Gradient PCR: Utilizes a thermal cycler capable of creating a temperature gradient across the block during the annealing step, allowing simultaneous testing of a temperature range (e.g., 55-65°C) in a single run [12] [15].

- Procedure: Set a gradient spanning approximately 10°C based on the calculated Tm of your primers. Analyze results to identify the temperature producing the strongest specific product with minimal background [12].

Stepwise Optimization Protocol

- Design Primers with appropriate length (15-30 bp) and GC content (40-60%) [16]

- Calculate Theoretical Tm using appropriate software or algorithms [16]

- Empirically Determine Optimal Ta using gradient PCR [12]

- Verify Product Specificity through melt curve analysis or gel electrophoresis [11]

- Validate Protocol with positive and negative controls before routine use [11]

Experimental Protocols: Detailed Methodologies

Gradient PCR Annealing Temperature Optimization

Objective: Determine the optimal annealing temperature for a new primer set [12].

Materials:

- Gradient thermal cycler (e.g., Biometra TAdvanced with Linear Gradient Function) [15]

- PCR reagents: template DNA, primers, polymerase, dNTPs, buffer

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment or capillary electrophoresis system [12]

Procedure:

- Prepare Master Mix: Combine all reaction components except template in a single tube [16]

- Aliquot Reactions: Distribute equal volumes to PCR tubes across the gradient block [12]

- Program Thermal Cycler:

- Analyze Results: Identify the temperature producing the strongest specific band with minimal non-specific products [12]

Expected Outcomes: A range of amplification efficiencies across temperatures, with the optimal Ta typically showing the highest yield of specific product [12].

Fast PCR Protocol Optimization

Objective: Significantly reduce PCR run time while maintaining efficiency and specificity [17].

Materials:

- Fast-cycling thermal cycler with rapid ramp rates [17]

- Engineered polymerase blends (e.g., KlenTaq) optimized for fast cycling [13]

- Thin-walled PCR tubes or plates for efficient heat transfer [14]

Procedure:

- Prepare Reaction Mix with increased primer and polymerase concentrations [13]

- Program Thermal Cycler with shortened steps:

- Validate Performance by comparing Cq values and endpoint yields with standard protocols [17]

Performance Metrics: Successful fast PCR protocols can reduce total run time from 84 minutes to 49 minutes (approximately 40% reduction) while maintaining equivalent sensitivity and specificity [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PCR Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerases | Hot-start Taq, KlenTaq (rapid deletion mutant) [13] | Reduces non-specific amplification; Enables faster cycling [7] [13] |

| PCR Additives | DMSO, Betaine, Formamide (1-10%) [16] | Destabilizes secondary structures; Improves amplification of GC-rich templates [7] |

| Buffer Components | MgCl₂ (0.5-5.0 mM), K⁺ (35-100 mM) [16] | Cofactors that influence polymerase activity and primer annealing stringency [16] |

| Optimization Systems | Gradient Thermal Cyclers [12] [15] | Enables parallel temperature testing in a single run [12] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How does a 2°C temperature shift create measurable impacts in my PCR results? A: A 2°C shift alters the binding equilibrium between primers and template. NCBI studies demonstrate that adjustments of just 2°C significantly improved both yield and specificity when amplifying bacterial DNA, highlighting the exponential nature of amplification sensitivity to small temperature changes [7].

Q2: What is the difference between block temperature and sample temperature? A: Block temperature is what the instrument measures and controls, while sample temperature is the actual temperature experienced by your reaction mixture. Due to thermal transfer lag, samples typically experience slower ramp rates than the block. Advanced thermal cyclers use predictive algorithms to control sample temperatures based on reaction volume and tube type, ensuring your samples actually reach the set temperatures [14].

Q3: Can I use a gradient thermal cycler for purposes other than annealing temperature optimization? A: Yes, while primarily used for annealing optimization, gradient functions can also help optimize denaturation temperatures for GC-rich templates, test extension temperature requirements for different polymerases, and verify temperature thresholds for eliminating cross-contamination [12].

Q4: How many cycles should I typically run for optimal yield without increasing non-specific products? A: Standard protocols use 25-40 cycles. Excessive cycling (>40 cycles) can increase non-target products while providing minimal increase in specific yield. The optimal number depends mainly on starting template concentration - dilute samples may require more cycles, but this increases the risk of amplifying non-specific targets [6].

Q5: What are the key specifications to evaluate when selecting a thermal cycler for sensitive applications? A: Critical specifications include: temperature accuracy (±0.5°C or better), block uniformity (±0.5°C across all wells), ramp rate capabilities, gradient functionality, and verification of sample temperature (not just block temperature) control. Regular calibration with temperature verification kits is essential for maintaining precision [14].

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the consequences of incomplete denaturation? Incomplete denaturation, where double-stranded DNA does not fully separate into single strands, can lead to reduced product yield. The DNA strands may "snap back" together, making them inaccessible for primer binding and polymerase extension [6]. This is particularly common with templates having high GC content or strong secondary structures [7].

How can I optimize the annealing temperature to prevent nonspecific products? The annealing temperature is critical for specificity. If the temperature is too low, primers may bind non-specifically, resulting in off-target amplification and multiple bands on a gel [7] [1]. A higher annealing temperature increases discrimination against incorrectly bound primers [6]. Use a gradient thermal cycler to empirically determine the optimal temperature, typically 3–5°C below the primer's melting temperature (Tm), and increase it in 2–3°C increments if nonspecific products are observed [7] [1].

My PCR yield is low even with a high number of cycles. What step should I check? Low yield can result from several factors, but the extension step is a key candidate. Short extension times may not allow the DNA polymerase to fully synthesize the target amplicon, resulting in incomplete products [7]. Ensure the extension time is sufficient for your polymerase and amplicon length (e.g., 1 minute per kilobase for Taq polymerase) [7] [1]. Furthermore, exceeding 45 cycles can lead to a plateau phase where reaction components are depleted and nonspecific products accumulate, counteracting any yield gains [1].

What is the purpose of a final extension step? A final extension step, typically 5–15 minutes at the extension temperature, ensures that all PCR products are fully synthesized. This is especially important for obtaining a high yield of full-length amplicons and can improve the consistency of results [1]. If you are cloning PCR products using TA vectors, a longer final extension (e.g., 30 minutes) is recommended to ensure proper addition of adenine (A) overhangs [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Thermal Cycling Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes Related to Step Timing | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low or No Yield | • Incomplete initial denaturation• Annealing temperature too high• Extension time too short• Too few cycles for low-copy templates | • Increase initial denaturation time (1-3 min) [1]• Lower annealing temperature in 2-3°C increments [1]• Increase extension time (1-2 min/kb) [7] [1]• Increase cycles to 35-40 for low templates [1] |

| Non-specific Bands / Smearing | • Annealing temperature too low• Excessive cycle number• Denaturation temperature too low | • Increase annealing temperature gradientally [7] [1]• Reduce cycles to 25-35 [1]• Ensure denaturation at 94-98°C [1] |

| Primer-Dimer Formation | • Low annealing temperature allowing 3' ends to bind• Excessive cycling | • Increase annealing temperature [10]• Use a hot-start polymerase [7]• Reduce number of cycles [1] |

Quantitative Data for Thermal Cycling Parameters

The following table summarizes key temperature and time settings for a standard three-step PCR protocol.

| Step | Typical Temperature Range | Typical Time Range | Critical Factors for Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 94–98 °C [7] [1] | 1–3 minutes [1] | Template complexity & GC-content; required for hot-start enzyme activation [1]. |

| Denaturation | 94–98 °C [7] [1] | 20–30 seconds [7] | GC-rich templates may need higher temp or longer time [7] [1]. |

| Annealing | 50–65 °C [7] | 20–60 seconds [7] [10] | Primer Tm; use 3–5°C below Tm, then optimize for specificity vs. efficiency [7] [1]. |

| Extension | 70–75 °C [1] (often 72 °C [7]) | 30–60 sec/kb [7] [1] | Polymerase speed (Taq: ~1 min/kb; Pfu: ~2 min/kb) and amplicon length [1]. |

| Final Extension | 70–75 °C [1] (often 72 °C) | 5–15 minutes [1] | Ensures complete, full-length products; crucial for A-tailed cloning [1]. |

| Cycle Number | — | 25–35 cycles [7] [1] | Starting template copy number; >45 cycles increases non-specific products [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Annealing Temperature Using a Gradient

1. Objective: To empirically determine the optimal annealing temperature for a primer set to maximize specificity and yield of a PCR amplification.

2. Principle: While the primer melting temperature (Tm) can be calculated, the optimal annealing temperature for a specific primer-template system is best determined experimentally. A gradient thermal cycler allows a range of annealing temperatures to be tested in a single run [1].

3. Reagents and Materials:

- Template DNA

- Forward and reverse primers

- DNA polymerase master mix (e.g., with buffer, dNTPs, Mg²⁺, enzyme)

- Nuclease-free water

- Gradient thermal cycler

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

4. Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix containing all PCR components except template DNA. Aliquot the master mix into individual PCR tubes, then add template to each.

- Thermal Cycling Program:

- Product Analysis: Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. Identify the annealing temperature that produces a single, sharp band of the expected size with the highest intensity.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Remains inactive at room temperature to prevent non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation before the initial denaturation step, improving specificity and yield [7] [1]. |

| DMSO | Additive that destabilizes DNA duplexes, aiding in the denaturation of templates with high GC content or strong secondary structures [7] [1]. |

| Betaine | Additive that can help amplify GC-rich templates by reducing the formation of secondary structures and equalizing the melting temperatures of DNA [7] [10]. |

| MgCl₂ | Cofactor essential for DNA polymerase activity. Its concentration must be optimized, as it influences enzyme fidelity, primer annealing, and template denaturation [10]. |

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Instrument that creates a precise temperature gradient across its block, enabling the simultaneous testing of multiple annealing temperatures in a single experiment for rapid optimization [1]. |

PCR Parameter Optimization Workflow

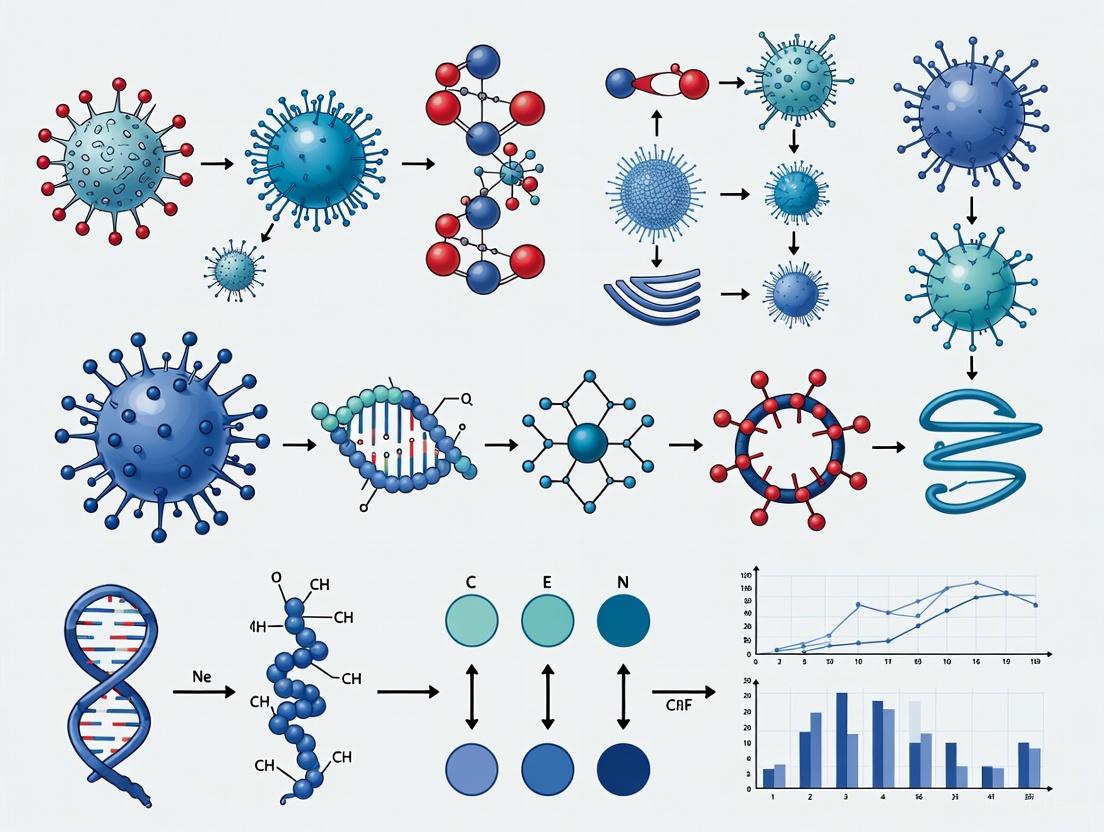

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and correcting common PCR problems related to thermal cycling parameters.

Advanced Method: "V" Shape PCR (VPCR) for Ultra-Fast Amplification

1. Methodology: VPCR is a rapid DNA amplification technique that eliminates the holding time at all three temperature steps. The amplification processes (denaturation, annealing, and extension) are completed during the dynamic heating and cooling phases of the thermal cycler. The temperature-time curve forms repeated "V" shapes, hence the name [18].

2. Key Protocol Adjustments:

- Thermal Profile: The protocol consists of cycles with two steps: a high temperature (e.g., 94°C) and a low temperature (e.g., 50-78°C), both with a hold time of 0 seconds [18].

- Primer Design: Requires longer primers with a higher melting temperature (Tm) to facilitate efficient binding and extension during the rapid temperature transitions [18].

- Polymerase Selection: Use of robust, fast DNA polymerases (e.g., KAPA2G Robust) is often necessary for success [18].

3. Outcome: This method can save up to two-thirds of the total amplification time compared to conventional PCR, enabling the amplification of a 500 bp fragment in under 17 minutes on an ordinary thermal cycler [18].

In the context of thermal cycling protocol modification sensitivity research, the optimization of cycle number stands as a critical parameter in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments. This technical support document addresses the fundamental challenge researchers face in balancing sufficient product yield against the generation of non-target amplification products. Cycle number directly influences amplification efficiency, product specificity, and experimental reproducibility, making its proper selection essential for reliable results in research and diagnostic applications.

The relationship between cycle number and amplification outcomes follows a predictable pattern characterized by three distinct phases: geometric amplification, linear growth, and ultimately the plateau phase where reaction components become depleted and amplification efficiency declines dramatically. Understanding these phases and their implications for both target and non-target products forms the foundation of effective cycle number optimization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does cycle number specifically affect the formation of non-target products? The optimum number of cycles depends mainly on the starting concentration of the target DNA when other parameters are optimized. Excessive cycling can significantly increase both the amount and complexity of nonspecific background products, a phenomenon known as the plateau effect. As cycles progress beyond the optimal range, reagents become depleted, enzyme fidelity decreases, and previously amplified products can serve as alternative templates, leading to amplification of non-target sequences that accumulate in later cycles [6] [19].

2. What are the visible indicators of excessive cycle numbers in gel electrophoresis? Too many cycles typically manifest as smearing or multiple bands on an electrophoresis gel rather than a single crisp band at the expected molecular weight. This smearing represents a heterogeneous population of amplification products including primer-dimers, non-specific amplicons, and larger DNA complexes that result from over-amplification [7].

3. How does starting template concentration influence optimal cycle number selection? The optimal number of cycles exhibits an inverse relationship with the starting concentration of the target DNA. Reactions with abundant template DNA (e.g., >1 ng) may require only 25-30 cycles to reach sufficient yield, while samples with scarce template (e.g., single copy genes) might need 40 or more cycles. However, increasing cycle numbers beyond 40 rarely improves yield and typically increases background noise [6] [19].

4. Can modifying other thermal cycling parameters compensate for suboptimal cycle numbers? While cycle number represents one key variable, it interacts significantly with other parameters. For instance, implementing more stringent annealing temperatures, especially during the first several cycles, can help increase specificity regardless of cycle number. Similarly, using hot-start polymerases can reduce early mis-priming events that become amplified over many cycles [6] [7].

5. How does cycle number optimization differ in quantitative PCR (qPCR) versus conventional PCR? In qPCR, the focus shifts to identifying the cycle threshold (Ct) value where amplification emerges from background noise, typically occurring during the geometric phase. The optimal cycle number for end-point analysis in conventional PCR generally corresponds to the late geometric or early plateau phase, before non-specific products accumulate significantly [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Product Yield Despite High Cycle Numbers

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient starting template: Verify template quality and concentration; consider increasing template amount rather than cycle number

- Suboptimal reagent concentrations: Check polymerase activity and dNTP concentrations; replenish components for reactions requiring >35 cycles

- Incomplete denaturation: Ensure denaturation temperature (typically 94-98°C) and duration (15-30 seconds) are adequate for your template, particularly for GC-rich sequences [7] [19]

- Enzyme activity loss: Be aware that Taq DNA polymerase has a half-life of approximately 40 minutes at 95°C, limiting practical cycle numbers in extended protocols [19]

Problem: Multiple Bands or Smearing on Gel Electrophoresis

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Excessive cycle numbers: Reduce cycles by 5-10 and re-evaluate; implement a gradient PCR to identify the optimal cycle number [6]

- Non-stringent annealing conditions: Increase annealing temperature by 2-5°C or utilize touchdown protocols where the annealing temperature starts high and decreases incrementally in early cycles [6]

- Primer design issues: Verify primer specificity and lack of self-complementarity; consider redesign if problems persist despite cycle optimization

- Template complexity: For complex genomes or multiplex reactions, implement "slowdown" or "stepdown" PCR modifications that combine cycle number optimization with progressive temperature stringency [6]

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Replicates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Plateau phase amplification: Reduce cycle number to ensure all reactions remain in the geometric amplification phase where efficiency is highest and most consistent [19]

- Thermal cycler calibration: Verify temperature uniformity across the block; poor uniformity can cause different wells to effectively experience different cycle efficiencies [20]

- Reagent instability: Prepare master mixes to minimize pipetting variation; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of enzymes and primers

- Insufficient cycle documentation: Record exact cycle numbers rather than ranges; small variations can significantly impact results when operating near the plateau phase

Experimental Protocols for Cycle Number Optimization

Protocol 1: Empirical Determination of Optimal Cycle Number

Objective: To establish the optimal cycle number that provides sufficient yield while minimizing non-target products.

Materials:

- Standard PCR reagents (polymerase, buffer, dNTPs, primers, template)

- Thermal cycler

- Gel electrophoresis equipment or other detection method

Methodology:

- Prepare a master mix containing all reaction components except template

- Aliquot equal volumes to multiple PCR tubes

- Add identical template quantities to each tube

- Program thermal cycler with identical conditions except for cycle number

- Run reactions with cycle numbers ranging from 20-40 in increments of 2 cycles

- Analyze products using appropriate detection method (gel electrophoresis, capillary electrophoresis, etc.)

- Identify the cycle number that provides strong target amplification with minimal background

Expected Outcomes: A sigmoidal relationship between cycle number and product yield will be observed, with a clear geometric phase followed by a plateau. The optimal cycle number typically falls just as the reaction begins to transition from geometric to linear growth.

Protocol 2: Cycle Number Optimization for Multiplex PCR

Objective: To identify cycle numbers that provide balanced amplification of multiple targets in a single reaction.

Materials:

- Multiplex PCR reagents (including multiple primer sets)

- Template DNA

- Thermal cycler

- Analysis method capable of distinguishing different amplicons (e.g., gel electrophoresis with different size products, capillary electrophoresis)

Methodology:

- Prepare multiplex master mix containing all primer sets

- Set up identical reactions with varying cycle numbers (25-40 cycles)

- Perform amplification with optimized thermal profile

- Analyze results, quantifying yield for each target amplicon

- Identify cycle number where all targets amplify efficiently with minimal primer-dimer formation

- Validate with template dilution series to ensure robustness across template concentrations

Expected Outcomes: Different targets may reach plateau phases at different cycle numbers due to varying amplification efficiencies. The optimal cycle represents the best compromise where all targets are detectable with minimal bias.

Quantitative Reference Data

Table 1: Cycle Number Recommendations Based on Template Concentration

| Template Concentration | Recommended Starting Cycle Number | Expected Yield Range | Risk of Non-target Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| High (>100 ng) | 25-30 cycles | 1-5 μg | Low |

| Moderate (10-100 ng) | 30-35 cycles | 0.1-1 μg | Moderate |

| Low (1-10 ng) | 35-40 cycles | 10-100 ng | High |

| Very Low (<1 ng) | 40-45 cycles* | 1-10 ng | Very High |

*Note: Cycles beyond 40 provide diminishing returns and significantly increase non-specific amplification [6] [19].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Cycle Number-Related Issues

| Observed Problem | Potential Cycle Number Issue | Immediate Solution | Long-term Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| No amplification | Too few cycles | Increase by 10 cycles | Optimize template preparation |

| Smearing on gel | Too many cycles | Reduce by 5-10 cycles | Implement touchdown PCR |

| Multiple discrete bands | Excessive cycles | Reduce by 5 cycles | Redesign primers |

| Inconsistent replicates | Operation at plateau phase | Reduce by 3-5 cycles | Improve pipetting precision |

| Primer-dimer predominant | Too many cycles | Reduce by 5-8 cycles | Optimize primer concentration |

Visual Guides

Diagram 1: Cycle Number Impact on Amplification

Diagram 2: Cycle Number Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Cycle Number Optimization Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Considerations for Cycle Number |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification in early cycles | Maintains activity through more cycles than standard enzymes |

| dNTP Mix | Provides nucleotides for DNA synthesis | Becomes depleted in high cycle number reactions |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Cofactor for polymerase activity | Concentration affects specificity, especially in later cycles |

| Template DNA | Target sequence for amplification | Concentration directly determines optimal cycle number |

| Specific Primers | Bind complementary sequences to initiate synthesis | Design quality affects cycle number tolerance |

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Allows simultaneous testing of multiple conditions | Essential for efficient cycle number optimization |

| Gel Electrophoresis System | Analyzes product yield and specificity | Standard method for evaluating amplification success |

| DNA Binding Dye | Enables product quantification | Helps determine exact yield at different cycle numbers |

| Molecular Weight Marker | Reference for product size verification | Critical for identifying non-specific products |

Cycle number optimization represents a fundamental aspect of PCR protocol refinement that directly impacts experimental success. By understanding the relationship between cycle number and the accumulation of both target and non-target products, researchers can systematically approach this critical parameter rather than relying on standardized protocols. The optimal cycle number represents a careful balance between sufficient yield and product purity, influenced primarily by template concentration but modified by primer design, reaction components, and specific application requirements.

The protocols and guidelines presented here provide a framework for evidence-based cycle number selection that aligns with the broader goals of thermal cycling protocol modification sensitivity research. Proper optimization not only improves immediate experimental outcomes but enhances reproducibility across laboratories and applications, ultimately supporting more reliable research findings and diagnostic results in pharmaceutical development and basic science.

Within the context of thermal cycling protocol modification sensitivity research, understanding the intricate relationship between reaction components and thermal parameters is paramount. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers and scientists engaged in optimizing enzymatic reactions, particularly in applications like PCR and industrial biocatalysis. The following FAQs and troubleshooting guides address common experimental challenges, offering detailed methodologies and data-driven solutions to enhance protocol robustness and reproducibility.

FAQs

1. How do template properties like GC content influence thermal cycling parameters?

Template DNA with high GC content has a higher melting temperature due to the stronger triple hydrogen bonding between guanine and cytosine bases compared to the double bond between adenine and thymine. This increased stability makes the DNA strands more resistant to denaturation. Consequently, for robust amplification, protocols often require higher denaturation temperatures or longer denaturation times to ensure complete strand separation. Furthermore, such templates are more prone to forming stable secondary structures (e.g., hairpins), which can impede polymerase progression. The use of additives like DMSO or betaine is common practice, as they can help destabilize these GC-rich regions and reduce secondary structure interference, thereby improving amplification efficiency [7].

2. What is the fundamental relationship between enzyme concentration and the thermal stability of a reaction?

While enzyme concentration primarily influences the reaction rate, it is intricately linked to observed thermal stability through a phenomenon described by the Equilibrium Model. This model posits that the active form of the enzyme (Eact) is in a rapid, reversible equilibrium with an inactive form (Einact), and it is this inactive form that proceeds to irreversible denaturation. A key parameter in this model is Teq, the temperature at which the concentrations of Eact and Einact are equal. When enzyme concentration is low, the system is more susceptible to irreversible inactivation over time, as the pool of Einact is constantly being drained. Therefore, understanding the enzyme's intrinsic Teq is crucial for predicting its functional lifespan under operational temperatures, beyond just its concentration [21].

3. Beyond irreversible denaturation, what mechanism causes enzyme activity to decrease at high temperatures?

The decrease is not solely due to irreversible denaturation. The Equilibrium Model describes a critical mechanism where the active enzyme (Eact) is in a fast, reversible equilibrium with a catalytically inactive form (Einact). This shift in equilibrium towards the inactive form occurs at elevated temperatures, even before irreversible thermal denaturation takes place. The temperature at which the concentrations of Eact and Einact are equal is defined as Teq. This parameter is a fundamental property of an enzyme, analogous to Km, and it explains the rapid loss of activity observed at temperatures above the optimum. For researchers, this means that an enzyme's performance at high temperatures is governed by both its Teq and its rate of irreversible denaturation [21].

4. How can machine learning assist in designing enzymes with improved thermal stability?

Machine learning (ML) offers data-driven strategies to navigate the vast sequence space of proteins efficiently. ML models can be trained on high-quality datasets of enzyme sequences and their corresponding thermal stability parameters (e.g., melting temperature Tm, optimal temperature Topt). These models learn the complex relationships between sequence or structural features and stability, allowing them to predict the thermostability of unseen enzyme variants. This approach helps prioritize a small set of promising mutants for experimental testing, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with traditional directed evolution or rational design. Furthermore, advanced ML can model epistasis (non-additive effects of combined mutations), which is crucial for predicting the fitness of multi-point mutants [22] [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low or Inconsistent Amplification Yield in PCR

Investigation and Resolution:

Verify Thermal Cycling Parameters:

- Denaturation: Ensure the denaturation temperature is sufficient (typically 94–98°C). For templates with high GC content or strong secondary structures, incrementally increase the denaturation temperature or time within a safe range for the polymerase [7].

- Annealing: Utilize a gradient PCR thermocycler to empirically determine the optimal annealing temperature. A temperature that is too high reduces primer binding efficiency, while one that is too low promotes non-specific binding [7].

- The table below summarizes key thermal parameters to optimize:

Parameter Typical Range Optimization Guidance Denaturation 94–98°C Increase for GC-rich templates. Annealing 50–65°C Use gradient PCR; set 3–5°C below primer Tm. Extension 68–72°C 1 min/kb for Taq polymerase; adjust for other enzymes. Assess Reaction Components:

- Enzyme Selection: Use hot-start polymerases to minimize non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation at lower temperatures [7].

- Template Quality: Re-evaluate DNA purity. Re-purify the template if inhibitors (e.g., phenol) are suspected [7].

- Additives: For difficult templates, include DMSO (1–5%) or betaine (0.5–1.5 M) in the reaction mix to lower the melting temperature and disrupt secondary structures [7].

Problem: Rapid Loss of Enzyme Activity at Elevated Temperatures

Investigation and Resolution:

Characterize Intrinsic Thermal Parameters: Determine if the activity loss is due to the reversible Eact/Einact equilibrium (governed by Teq) or irreversible denaturation. This requires specialized assays that monitor very early reaction kinetics at different temperatures, as described in the Equilibrium Model [21]. The experimental workflow for this characterization is outlined in the diagram below.

Explore Enzyme Engineering: If the native enzyme's Teq is too low for the application, consider stability engineering.

- Rational Design: Introduce mutations that enhance stabilizing interactions (e.g., hydrophobic packing, salt bridges, hydrogen bonds) [22].

- Data-Driven Design: Employ machine learning strategies like the iCASE method, which uses dynamics-based metrics to identify mutation sites that can enhance both stability and activity, addressing the common stability-activity trade-off [23].

The following table compiles key thermal parameters discussed in the research, providing a reference for experimental design and analysis.

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Experimental Determination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimum Temperature | Topt | Temperature at which enzyme activity is maximum [24]. | Measure initial reaction rates across a temperature gradient. |

| Melting Temperature | Tm | Temperature at which 50% of the enzyme is unfolded [22]. | Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) or fluorescence-based thermal shift assays. |

| Equilibrium Temperature | Teq | Temperature at which concentrations of active (Eact) and inactive (Einact) enzyme forms are equal [21]. | Fit progress curve data from continuous assays at multiple temperatures to the Equilibrium Model. |

| Enthalpy of Equilibrium | ΔHeq | Enthalpy change associated with the Eact/Einact equilibrium [21]. | Derived from the temperature dependence of the equilibrium constant in the Equilibrium Model. |

| Quantification Cycle | Cq | PCR cycle at which fluorescence exceeds a defined threshold [25]. | Real-time PCR instrumentation software analysis. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Teq and ΔHeq Using the Equilibrium Model

This protocol outlines the direct data-fitting method for characterizing an enzyme's intrinsic thermal behavior according to the Equilibrium Model [21].

Key Materials:

- Purified enzyme.

- Saturated substrate solution (≥10 × Km).

- Thermostable spectrophotometer with rapid kinetics capability (e.g., Peltier-controlled cuvette holder).

- Precision temperature probe (accurate to ±0.1°C).

Methodology:

- Assay Setup: Prepare reaction mixtures in quartz cuvettes. Use buffers adjusted to the correct pH at each assay temperature. Include salts or non-ionic detergents if using low enzyme concentrations to prevent surface adsorption.

- Temperature Control: Equilibrate the reaction mixture (excluding enzyme) to the target temperature. Verify stability using a calibrated thermocouple probe placed in the cuvette. Minimize temperature gradients and evaporation.

- Reaction Initiation & Data Acquisition: Initiate the reaction by adding a small volume of pre-chilled enzyme. Immediately record the progress curve (product formation vs. time) at intervals as short as 0.125 seconds.

- Data Collection Range: Repeat steps 2-3 across a wide temperature range, from well below the suspected Topt to temperatures where activity declines significantly.

- Data Analysis: Fit the collected progress curve data directly to the equations of the Equilibrium Model using non-linear regression software. The fit will yield the parameters Teq and ΔHeq, in addition to the traditional kinetic parameters (ΔG‡cat, ΔG‡inact) [21].

Protocol 2: Empirical Optimization of PCR Annealing Temperature

Key Materials:

- DNA template, primers, dNTPs.

- Thermostable DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq, hot-start variants).

- Gradient PCR thermocycler.

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix containing all PCR components and dispense it equally into PCR tubes or a plate.

- Gradient Programming: Set the thermocycler's annealing step to a gradient that spans a plausible range (e.g., 45°C to 65°C). The denaturation and extension steps are held constant.

- Amplification: Run the PCR protocol for 25-35 cycles.

- Analysis: Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. The optimal annealing temperature is the highest temperature that produces a strong, specific amplicon with minimal non-specific bands or primer-dimer [7].

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Enzyme Activity vs. Temperature Models

Diagram 2: Workflow for Enzyme Thermal Characterization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Thermal Parameter Research |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Remains inactive until high temperatures are reached, minimizing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during PCR setup [7]. |

| SYBR Green I Dye | A fluorescent dsDNA-binding dye used in real-time PCR to monitor amplicon accumulation kinetically, enabling Cq determination and melting curve analysis [25]. |

| DMSO / Betaine | Additives used to destabilize base pairing in nucleic acids, facilitating the denaturation of GC-rich templates and reducing secondary structure [7]. |

| Thermostable Cuvettes | Quartz cuvettes used in enzyme kinetics studies for their efficient temperature equilibration and stability at high temperatures [21]. |

| Calibrated Temperature Probe | Provides accurate (±0.1°C) temperature measurement within the reaction vessel, which is critical for reliable thermal parameter determination [21]. |

| Machine Learning Datasets (e.g., BRENDA, ThermoMutDB) | Curated databases of enzyme properties and mutant stability data used to train predictive models for enzyme thermostability design [22]. |

Advanced Protocol Engineering: From Theory to Practical Application

Within the broader context of thermal cycling protocol modification sensitivity research, the empirical determination of the optimal annealing temperature (Ta) stands as a fundamental process for establishing robust and reliable polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocols [12]. The annealing temperature is a critical variable that governs the specificity and efficiency of primer-template binding, directly impacting the quality of downstream applications such as sequencing, cloning, and gene expression analysis [12]. When the Ta is too low, primers can bind non-specifically to partially homologous sequences, leading to unwanted amplification products and smeared gel bands. Conversely, a Ta that is too high reduces reaction efficiency, as insufficient primer binding occurs, resulting in low or no yield [26]. Gradient PCR represents a powerful methodological approach that systematically addresses this optimization challenge by enabling the parallel screening of a temperature range in a single experiment, thereby accelerating protocol development and enhancing assay reproducibility [12].

Key Concepts: Understanding Gradient PCR

What is Gradient PCR?

A gradient thermal cycler is a specialized instrument engineered to apply a precise, linear temperature gradient across its sample block during the annealing step of the PCR cycle [12]. Unlike conventional thermal cyclers that maintain a single, uniform temperature across all reaction wells, a gradient cycler systematically varies the temperature from one end of the block to the other. For instance, on a 96-well block, each column of wells can be set to a different temperature within a user-defined range [12]. This sophisticated functionality relies on advanced Peltier elements and thermal sensing technology to establish and maintain a stable, reproducible temperature differential, ensuring that observed variations in PCR performance are attributable solely to the annealing temperature [12].

The Relationship between Tm and Optimal Ta

The melting temperature (Tm) of a primer is the temperature at which half of the primer-DNA duplexes dissociate [27]. It is a theoretical value calculated based on the primer's length, nucleotide sequence, and GC content, as well as the reaction conditions such as salt concentration [28]. While the Tm provides a crucial starting point for protocol development, the optimal annealing temperature (Ta) is determined empirically and is typically 3–5°C below the calculated Tm of the primer with the lowest melting temperature in the pair [5] [27]. This offset ensures sufficient stringency for specific binding while maintaining high reaction efficiency.

Experimental Protocol: Determining Optimal Annealing Temperature via Gradient PCR

Step-by-Step Methodology

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for using gradient PCR to empirically determine the perfect annealing temperature for a specific primer-template combination [12] [26].

- Prepare the Master Mix: Create a single master mix containing all PCR components: DNA template, forward and reverse primers, thermostable DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and reaction buffer [26]. Including an additive like bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 10-100 μg/ml or DMSO at 1-10% can be beneficial for difficult templates [10]. This ensures reaction consistency across all temperature points.

- Aliquot the Reaction Mixture: Distribute equal volumes of the master mix into the wells of a PCR plate arranged along the gradient axis of the thermal cycler [26]. For a negative control, aliquot a portion of the master mix into a separate well without adding template DNA, compensating for the volume with sterile water [10].

- Program the Thermal Cycler: Set up the PCR program with the following cycling parameters:

- Initial Denaturation: One cycle at 94–98°C for 2–5 minutes.

- Amplification Cycles (25–40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94–98°C for 15–60 seconds.

- Annealing: Set the gradient function. Define the highest and lowest temperatures for the span (e.g., 55°C to 65°C) [12] [26]. The cycler will automatically calculate and apply the intermediate temperatures.

- Extension: 68–72°C for a duration suitable for the amplicon length (e.g., 1 minute per kilobase).

- Final Extension: One cycle at 68–72°C for 5–15 minutes [5] [10].

- Execute the PCR Run: Place the PCR plate in the gradient thermal cycler and start the programmed run.

- Analyze the Results: After the run, analyze the amplification products from each well. Gel electrophoresis is the most common method:

- The optimal Ta is identified as the temperature that produces the brightest, single band of the expected amplicon size on the gel, with minimal or no non-specific bands or primer-dimers [12].

- If the optimal temperature is at the extreme end of the initial gradient, a second, narrower gradient run can be performed for finer precision [12].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the gradient PCR optimization experiment:

Troubleshooting & FAQs: A Technical Support Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How wide should the initial temperature gradient be? A typical initial thermal gradient spans 10–12°C around the calculated average Tm of your primer pair [12] [27]. For example, if the calculated Tm is 60°C, a gradient from 55°C to 65°C is an appropriate starting point.

Q2: My gradient PCR shows a smear or multiple bands at lower temperatures but no product at higher temperatures. What does this mean? This is a classic indication of sub-optimal reaction conditions due to poor specificity at low Ta and overly stringent conditions at high Ta [12] [9]. The solution is to use the temperature from the gradient that shows the best specificity (i.e., a single clean band) as your new standard Ta. If the product yield at this temperature is low, you can try increasing the primer or Mg2+ concentration slightly, or adding PCR enhancers like DMSO or BSA [10].

Q3: I get no amplification product across the entire temperature gradient. What should I check? This suggests that the problem is independent of the annealing temperature [12]. You should systematically check:

- Template DNA: Verify integrity, purity, and sufficient quantity. Re-purify if necessary to remove inhibitors [5].

- Primers: Confirm design, specificity, and quality. Check for degradation and ensure correct resuspension [5] [9].

- Reaction Components: Ensure all components were added, including Mg2+, and that the DNA polymerase is functional. Always include a positive control reaction to verify reagent functionality [9] [29].

Q4: Can gradient PCR be used to optimize factors other than annealing temperature? While its primary use is for Ta optimization, the gradient feature can be leveraged for other experimental parameters. For instance, by fixing the annealing step and running a gradient during the extension step, researchers can optimize the activity of a novel thermostable polymerase across a thermal range, improving assay specificity and overall yield [12].

Advanced Troubleshooting: Sensitivity to Reagent Batches

Research into thermal cycling protocol modification sensitivity has revealed that even minor, undocumented changes in reagent batches can cause assay failure, highlighting the importance of empirical validation [29]. In one documented case, a specific PCR assay failed completely with a new batch of a one-step RT-PCR mix from a manufacturer, despite the batch passing the manufacturer's quality control and working perfectly for other assays [29]. The failure was only resolved by switching to a different manufacturer's kit or reverting to an old batch of the original kit.

Recommendation: For critical diagnostic or validated research assays, it is essential to:

- Control batch changes individually for every assay, not just a subset.

- Purchase large batches of reagents to ensure long-term consistency.

- Prepare protocols for reagents from more than one manufacturer to assure rapid and reliable diagnostics when troubleshooting [29].

Data Presentation & Reagent Solutions

Quantitative Data for Gradient PCR Setup

The table below summarizes key parameters for planning and executing a successful gradient PCR experiment, based on information from the search results.

| Parameter | Recommended Range / Value | Notes & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Gradient Span | 10–12°C [12] [27] | Centered on the calculated average Tm of the primer pair. |

| Annealing Temp. (Ta) | 3–5°C below the lowest primer Tm [5] [27] | The optimal Ta is empirically determined from the gradient results. |

| Primer Length | 15–30 nucleotides [10] | - |

| Primer Concentration | 0.1–1.0 μM [5] | 0.5 μM is a common starting concentration. High concentrations can promote non-specific binding. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [10] | - |

| Mg2+ Concentration | 1.5–5.0 mM [10] | Optimize if non-specific products persist; excess Mg2+ can decrease fidelity [5]. |

| Template Quantity | 1–1000 ng (genomic DNA) [10] | 10^4 to 10^7 molecules. Too much template can cause non-specific amplification [5]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for performing gradient PCR optimization, along with their critical functions in the experiment.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Gradient PCR |

|---|---|

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Instrument that applies a linear temperature gradient across the sample block during the annealing step, allowing parallel testing of multiple temperatures [12]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that remains inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [5] [9]. |

| dNTP Mix | Deoxynucleotides (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) that serve as the building blocks for the synthesis of new DNA strands [10]. |

| PCR Buffers (with Mg2+) | Provides the optimal chemical environment (pH, salts) for polymerase activity. Often includes MgCl2 or MgSO4, a essential co-factor for the enzyme [10]. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., DMSO, BSA) | Enhancers that can help denature complex templates (high GC content), reduce secondary structures, and stabilize reaction components [5] [10]. |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis System | Standard method for analyzing PCR products post-run to visually assess yield, specificity, and amplicon size across the temperature gradient [12]. |

Technical Support Center: VPCR Troubleshooting and FAQs

VPCR, or "V" Shape Polymerase Chain Reaction, is a rapid DNA amplification technique that completes the denaturation, annealing, and extension processes during the dynamic heating and cooling phases of thermal cycling, eliminating holding times. This method saves approximately two-thirds of the amplification time compared to conventional PCR while retaining specificity, sensitivity, and compatibility with quantitative detection [30]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting and procedural guidance for researchers implementing VPCR in their workflows.

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common VPCR Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No Amplification | Non-optimal primer design; inefficient polymerase; reagent batch variability | Design longer primers with higher Tm; use robust polymerases (e.g., KAPA2G Robust); test new reagent batches with a validated assay [30] [29]. |

| Non-Specific Bands or Primer-Dimers | Annealing temperature too low; contaminated reagents | Optimize and use a higher annealing temperature; ensure a sterile workspace with filter tips and dedicated equipment [30] [31]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Runs | Reagent batch differences; poor sample purity; pipetting errors | Perform batch-to-batch quality control for all assays; check template purity (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8); use a master mix to minimize pipetting inaccuracies [31] [29]. |

| Low Sensitivity or Efficiency | Presence of PCR inhibitors; degraded template or reagents | Use PMA dye to exclude dead cell DNA in viability testing; avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles for reagents; use fresh aliquots [31] [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between VPCR and conventional PCR? The key difference lies in the reaction timeline. Conventional PCR uses discrete holding steps at denaturation, annealing, and extension temperatures for set durations (e.g., 30 seconds each). VPCR omits these holding times, performing the amplification reactions as the temperature dynamically changes between the upper and lower limits, forming a "V" shape on the thermal profile. This can reduce total amplification time by over two-thirds [30].

Q2: Can I run VPCR on my lab's standard thermal cycler? Yes. A significant advantage of VPCR is that it is designed to work on ordinary PCR thermal cyclers without requiring specialized rapid-cycling equipment. The method leverages the cycler's standard thermal ramp rates [30].

Q3: How do I design primers optimized for VPCR? For optimal VPCR performance, it is recommended to use longer primers with a higher melting temperature (Tm). This ensures efficient binding during the fast temperature transitions. Always determine the optimal annealing temperature for new primer sets [30] [31].

Q4: Why did my validated PCR assay fail when I used a new batch of the same master mix? Different PCR assays can exhibit unique sensitivities to minute, unstated changes in reagent buffer compositions between batches. This can sometimes lead to complete amplification failure, even if the new batch works for other assays. For critical in-house tests, it is advised to validate new reagent batches with every specific assay before use in diagnostics and to maintain a large stock of a known good batch [29].

Q5: How can I prevent contamination in my VPCR reactions?

- Use sterile filter tips and dedicated pipettes and racks for PCR setup.

- Maintain a reserved, clean space for PCR reactions.

- Decontaminate surfaces with ethanol, bleach, or RNase removers.

- Wear gloves and change them frequently [31].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating VPCR on a Standard Thermal Cycler

This protocol is adapted from foundational VPCR research and is used to amplify a 500 bp fragment from λ-DNA [30].

1. Reagent Setup

- Prepare a 10 µL reaction mixture containing:

- 1x Taq Buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.4, 20 mM KCl, 10 mM (NH₄)₂SO₄, 2 mM MgSO₄)

- 0.2 mM dNTPs

- 0.1 U/µL of a robust DNA polymerase (e.g., EasyTaq or KAPA2G Robust)

- Appropriate primer concentration (e.g., 0.4 µM each)

- Template DNA (e.g., 0.1 ng/µL λ-DNA)

2. Thermal Cycling Conditions

- VPCR Protocol: 30 cycles of:

- 94°C for 0 seconds

- 60°C for 0 seconds

- Note: The cycler will still require time to ramp between these temperatures. The total run time for 30 cycles will be approximately 16-17 minutes.

3. Analysis

- Analyze PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis alongside a conventional PCR product (30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s) for comparison.

Protocol 2: Fastest VPCR for Short Amplicons

This protocol demonstrates an ultra-fast VPCR for a 98 bp fragment, achieving amplification in about 8 minutes [30].

1. Reagent Setup

- Prepare a 5 µL reaction mixture containing:

- 1x Taq Buffer

- Additional MgCl₂ (to a final concentration of 3 mM, including buffer salt)

- 0.2 mM dNTPs

- 0.05 U/µL of KAPA2G Robust DNA Polymerase

- 0.5 µM of each specific primer (e.g., LG/LRG)

- Template DNA

2. Thermal Cycling Conditions with Touchdown

- 25 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 89°C for 0 seconds (decreasing by 0.1°C per cycle)

- Annealing/Extension: 77°C for 0 seconds (increasing by 0.1°C per cycle)

- This touchdown approach enhances specificity during rapid cycling.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for VPCR Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Robust DNA Polymerase | Enzymatically synthesizes new DNA strands. | KAPA2G Robust Polymerase is cited for successful fast cycling. Hot-Start polymerases can reduce non-specific amplification [30] [31]. |

| Primers with High Tm | Bind specifically to the target DNA sequence. | Requires longer primers with higher melting temperatures. PAGE-purified primers are recommended for purity [30]. |

| dNTPs | Building blocks for new DNA strands. | Use high-quality aliquots to prevent degradation from multiple freeze-thaw cycles [31]. |

| Mg²⁺ Solution | Cofactor for DNA polymerase; critical for efficiency. | Concentration may need optimization. The fast VPCR protocol uses 3 mM Mg²⁺ [30]. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | For Viability-PCR (vPCR); selectively inhibits DNA amplification from dead cells with compromised membranes. | Used in conjunction with VPCR/qPCR for distinguishing viable microorganisms in quality control [32]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

VPCR Experimental Workflow and Troubleshooting Loop

Conceptual Comparison: Conventional PCR vs. VPCR

Touchdown (TD) and Stepdown (SD) PCR are advanced thermal cycling techniques designed to enhance the specificity and yield of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. Within the context of thermal cycling protocol modification sensitivity research, these methods function by systematically varying the annealing temperature during the initial cycles of PCR. This approach preferentially enriches the desired target amplicon early in the reaction, even under suboptimal buffer conditions or with imperfectly matched primer-template pairs, thereby circumventing the common pitfalls of standard PCR and minimizing the need for extensive reaction optimization [33] [34] [35].

FAQs: Core Concepts and Applications

1. What is the fundamental principle behind Touchdown and Stepdown PCR?

The core principle is to initiate PCR with an annealing temperature higher than the calculated optimum for the primers. The temperature is then progressively decreased—either gradually in TD-PCR or in sharper steps in SD-PCR—until it reaches a temperature below the optimum. This strategy ensures that in the early, critical cycles, only the most perfectly matched primer-target hybrids (the specific target) are formed. Once this specific product is preferentially amplified, the reaction continues at a lower, more permissive temperature to maximize yield without promoting non-specific amplification [33] [34].

2. How do Touchdown and Stepdown PCR improve specificity and yield simultaneously?

These methods exploit the competitive advantage of the correct amplicon. The initial high-stringency cycles selectively amplify the target sequence, effectively "enriching" the reaction with the correct product. When the temperature drops below the optimum in later cycles, the reaction becomes highly efficient for amplifying this now-abundant specific target, but inefficient at initiating non-specific amplification from the original, complex template. This mechanism allows both high specificity and high yield to be achieved in a single reaction [33] [34].

3. In what experimental scenarios are these techniques particularly advantageous?

TD and SD PCR are exceptionally useful in several key scenarios relevant to research and drug development:

- When the optimal annealing temperature is unknown or difficult to predict.

- When using primers across different biological systems where primer-template mismatches may occur.

- When amplifying multiple targets with varying annealing temperatures in a single tube.

- For simplifying PCR optimization, especially when buffer conditions (e.g., MgCl₂ concentration) are not fully optimized [33] [35].

4. Can these methods be used with any thermal cycler?

Yes, the versatility is a key strength. Modern thermal cyclers with programmable touchdown functionality can execute TD-PCR with gradual temperature decreases. For older or basic instruments that lack this feature, the Stepdown PCR protocol can be manually programmed as a series of distinct cycling blocks with discrete annealing temperature drops, achieving a similar outcome [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low or No Yield After TD/SD PCR

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Initial annealing temperature too high | Ensure the starting temperature is only 5-10°C above the primer Tm. An excessively high start can prevent any amplification [33] [1]. |

| Insufficient number of high-stringency cycles | Program more cycles (e.g., 10-15) in the TD/SD phase to allow the reaction to "find" the optimal temperature [33]. |

| Template degradation or inhibitors | Check template DNA integrity via gel electrophoresis and ensure purity (A260/280 ratio ≥1.8). Re-purify if necessary [5] [36]. |

| Suboptimal Mg²⁺ concentration | Titrate Mg²⁺ concentration, typically between 1.5-4.0 mM, as it is a critical cofactor for polymerase activity [10] [5]. |

Problem 2: Persistent Non-Specific Amplification

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Temperature decline is too rapid | In TD-PCR, decrease the temperature more slowly (e.g., 0.5°C per cycle). In SD-PCR, add more steps with smaller temperature increments [33] [35]. |

| Final annealing temperature is too low | Raise the final annealing temperature used for the last set of cycles to increase stringency [1] [36]. |

| Primer design issues | Re-evaluate primers: avoid self-complementarity, long mono-nucleotide runs, and ensure a Tm difference of ≤5°C between primers. Use primer design software [10] [36]. |

| Excessive primer concentration | Optimize primer concentration, typically between 0.1–1 μM. High concentrations promote mis-priming [5] [36]. |

Problem 3: Smeared Bands on Agarose Gel

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Excessive cycle numbers | Reduce the total number of PCR cycles (generally 25-35 is sufficient) to prevent accumulation of non-specific by-products and primer-dimer [5] [1]. |

| Contaminated template or reagents | Use fresh, filtered pipette tips and prepare new reagent aliquots. Include a negative control to identify contamination [36]. |

| Insufficient final extension time | Implement or extend the final extension step (5-15 minutes) to ensure all amplicons are fully synthesized and to reduce smearing from incomplete products [1]. |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Classic Touchdown PCR

This protocol is designed for thermal cyclers with touchdown functionality.

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Assemble a standard 50 µL PCR master mix on ice. A typical mixture includes:

- 1X PCR Buffer (supplied with polymerase)

- 200 µM of each dNTP

- 1.5 mM MgCl₂ (adjust if not in buffer)

- 20-50 pmol of each primer (0.1-1 µM final concentration)

- 1-1000 ng of DNA template

- 0.5-2.5 units of thermostable DNA polymerase

- Nuclease-free water to 50 µL [10]

- Thermal Cycling Program:

- Initial Denaturation: 94–98°C for 1–3 minutes [1].

- Touchdown Phase: 10-15 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94–98°C for 20-30 seconds.

- Annealing: Start at 10°C above the primer Tm. Decrease the temperature by 1°C per cycle.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase of target.

- Final Amplification Phase: 20-25 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94–98°C for 20-30 seconds.

- Annealing: Use a temperature 5°C below the primer Tm.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-15 minutes [33] [1].

- Analysis: Analyze 5-10 µL of the PCR product by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Protocol 2: Manual Stepdown PCR

This protocol is suitable for all thermal cyclers, including those without automated touchdown features.

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Identical to Protocol 1.

- Thermal Cycling Program:

- Initial Denaturation: 94–98°C for 1–3 minutes [1].

- Stepdown Phase 1: 3-5 cycles with annealing at 62°C for 30-60 seconds.

- Stepdown Phase 2: 3-5 cycles with annealing at 58°C for 30-60 seconds.

- Stepdown Phase 3: 3-5 cycles with annealing at 54°C for 30-60 seconds.

- Final Amplification Phase: 25-29 cycles with annealing at 50°C for 30-60 seconds.

- Extension (after each annealing step in all phases): 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-15 minutes [33].

- Analysis: Analyze 5-10 µL of the PCR product by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Workflow and Mechanism Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their optimized functions in TD/SD PCR protocols, based on empirical findings from thermal cycling sensitivity research.

| Reagent | Function & Optimization Notes |

|---|---|

| Primers | Must be well-designed (18-30 nt, 40-60% GC, Tm within 5°C). The 3' end should be clamped with a G or C to increase priming efficiency and prevent breathing [10]. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Hot-start polymerases are recommended to prevent non-specific activity during reaction setup. The choice of enzyme (e.g., Taq vs. high-fidelity) depends on the need for speed or accuracy [5]. |

| Magnesium Ions (Mg²⁺) | A critical cofactor; concentration typically ranges from 1.5-5.0 mM. It must be optimized as it profoundly affects primer annealing, enzyme processivity, and specificity [10] [5]. |

| PCR Additives/Enhancers | Reagents like DMSO (1-10%), Betaine (0.5-2.5 M), or Formamide (1.25-10%) can help denature complex templates (e.g., GC-rich sequences). Note: they lower the effective primer Tm, which must be accounted for [10] [5] [1]. |