Mastering Aseptic Technique: A Comprehensive Guide for Reliable Microbial Culture and Cell Line Handling

This article provides a complete guide to aseptic techniques for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals handling microbial cultures and cell lines.

Mastering Aseptic Technique: A Comprehensive Guide for Reliable Microbial Culture and Cell Line Handling

Abstract

This article provides a complete guide to aseptic techniques for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals handling microbial cultures and cell lines. It covers the foundational principles of contamination prevention, step-by-step methodological protocols for transfers and handling, advanced troubleshooting for identifying and rectifying contamination, and validation through Good Microbiological Laboratory Practices (GMLP) and biosafety standards. The content is designed to ensure experimental reproducibility, protect valuable samples, and maintain a safe laboratory environment, directly addressing the core challenges faced in biomedical and clinical research settings.

The Principles of Asepsis: Defining Your First Line of Defense Against Contamination

In microbial culture handling and pharmaceutical research, the precise distinction between "aseptic" and "sterile" is fundamental to experimental validity and product safety. While often used interchangeably in casual context, these terms describe distinct concepts with specific applications in controlled environments. Aseptic techniques comprise a set of procedures designed to prevent contamination of sterile materials by excluding pathogenic microorganisms, whereas sterile techniques refer to validated processes that completely eliminate all viable microorganisms, including spores. This whitepaper delineates the critical differences between these two concepts, frames them within the context of microbial culture handling research, and provides detailed methodologies for their implementation in laboratory and drug development settings. Understanding this distinction is crucial for maintaining pure stock cultures, ensuring the reliability of microbiological experiments, and complying with stringent regulatory requirements for sterile pharmaceutical products.

In the realm of microbiology and pharmaceutical development, precision in terminology directly correlates with experimental integrity and patient safety. The terms "aseptic" and "sterile" represent hierarchal levels of microbial control essential for different aspects of research and production.

Sterile describes a state of being completely free from all viable microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and spores [1] [2] [3]. Achieving sterility is an absolute and validated endpoint, often described statistically by a Sterility Assurance Level (SAL) of 10⁻⁶, which denotes a probability of no more than one non-sterile unit in one million [4] [2]. Sterility is a quality attributed to an environment, instrument, or product after it has undergone a definitive sterilization process.

Aseptic, by contrast, refers to the procedural efforts and techniques used to maintain sterility by preventing the introduction of contaminants into a product or environment that is already sterile [1] [5] [3]. Aseptic technique is not a method to achieve sterility but to preserve it. It is the practical application of practices and behaviors that minimize the risk of contamination during complex handling procedures, such as transferring cultures or preparing sterile media [5].

The relationship is symbiotic: sterile techniques create the initial condition of non-viability, and aseptic techniques sustain that condition throughout subsequent operations. For researchers handling microbial cultures, this distinction is operationalized daily. The goal is to use aseptic technique to maintain the sterility of sterile equipment and media, thereby ensuring that only the intended organisms are present in pure cultures.

Comparative Analysis: Aseptic versus Sterile in Practice

The following table synthesizes the core distinctions between aseptic and sterile techniques, highlighting their unique objectives, methods, and applications within a research and development context.

Table 1: Core distinctions between aseptic and sterile techniques

| Feature | Aseptic Technique | Sterile Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | To prevent contamination during procedures and maintain sterility [3] | To completely eliminate all viable microorganisms, including spores [1] [3] |

| State vs. Process | A process and a set of behaviors [1] | A state or condition of an item or environment [1] |

| Scope of Microbial Control | Minimizes the introduction, growth, and transfer of pathogens [5] | Total destruction or removal of all microbial life [2] |

| Common Methods | Laminar flow hoods, Bunsen burners, flawless manipulative skills [5] [3] | Autoclaving (steam sterilization), filtration, gamma irradiation, ethylene oxide gas [4] [3] |

| Key Applications in Research | Inoculating media, transferring cultures, handling sensitive reagents [5] | Preparing sterile media, decontaminating instruments and waste, sterilizing heat-labile solutions via filtration [4] [6] |

| Validation & Measurement | Monitored via environmental controls (settle plates, air samplers) and process simulation (media fills) [4] | Validated by achieving a defined Sterility Assurance Level (SAL), often 10⁻⁶ [4] [2] |

The selection between employing aseptic technique alone or in conjunction with a full sterilization process depends entirely on the procedural requirements. Many research and manufacturing workflows integrate both: materials are first rendered sterile via autoclaving or filtration, and then they are handled using aseptic technique to prevent contamination during the experiment or production process.

The Critical Role in Microbial Culture Handling

For researchers working with pure cultures, the failure of aseptic technique can compromise months of work. Contamination from airborne spores, non-sterile surfaces, or the operator can overgrow the target microbe, consume nutrients, produce metabolites that alter the environment, or lead to incorrect conclusions [5]. Proper aseptic technique is, therefore, a compulsory laboratory skill.

The core objectives of aseptic technique in a microbiological context are [5]:

- To avoid contaminating cultures with exogenous microbes from the environment, lab surfaces, or the investigator.

- To prevent the culture from contaminating the laboratory environment or the investigator, especially when handling pathogens.

- To enable the successful transfer and subculturing of isolates while maintaining purity.

Table 2: Aseptic practices for different biosafety levels

| Biosafety Level (BSL) | Risk Profile | Example Agents | Required Aseptic and Containment Practices |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSL-1 | Low risk, unlikely to cause disease | E. coli K-12, Pseudomonas | Standard microbiological practices; basic aseptic technique; no special containment equipment [5] |

| BSL-2 | Moderate risk, associated with human disease | Salmonella, Hepatitis viruses | BSL-1 plus lab coats, gloves, biohazard signs; procedures that minimize aerosol generation; use of Class I or II Biosafety Cabinets (BSCs) for aerosol-producing activities [5] |

| BSL-3 | High individual risk, low community risk; can be transmitted via aerosols | Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Bacillus anthracis | BSL-2 plus enhanced PPE, controlled lab access, physical separation, mandatory use of BSCs for all open manipulations, and laboratory exhaust air not recirculated [5] |

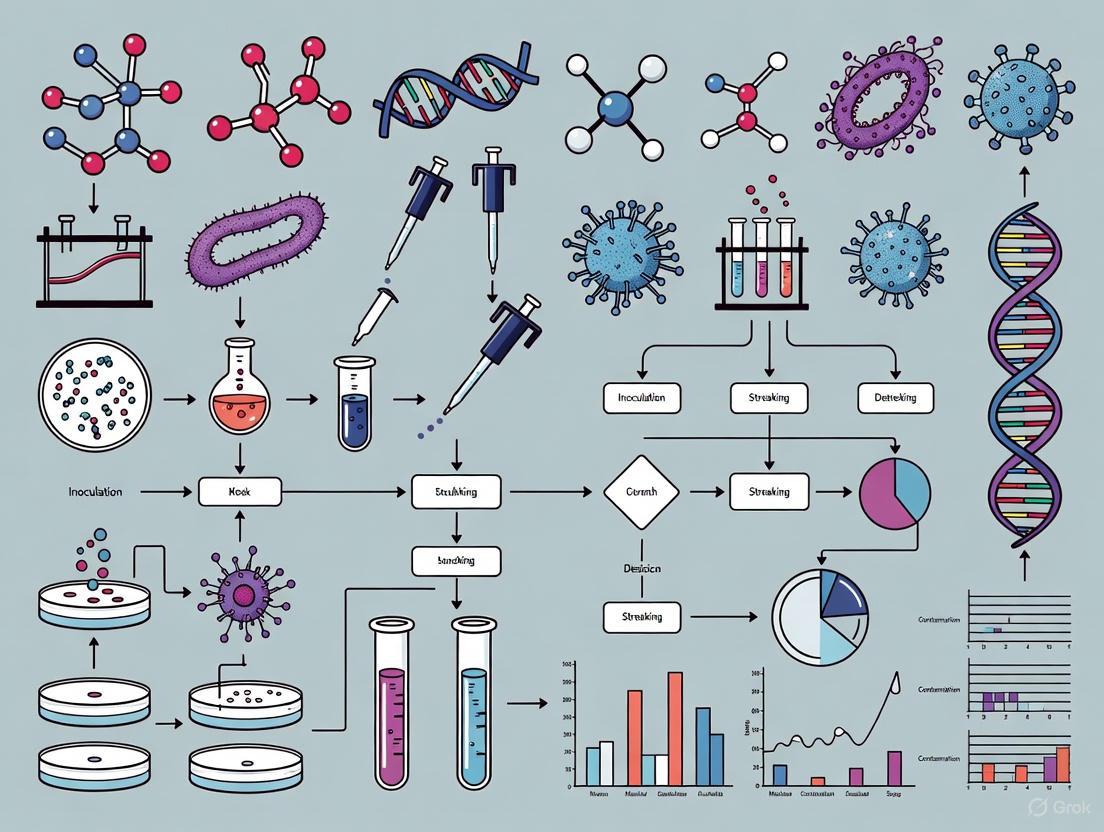

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process a researcher must follow to determine the necessary level of containment and technique when handling biological materials.

Diagram: Decision pathway for biosafety level and technique selection

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of aseptic and sterile techniques relies on specific reagents, equipment, and materials. The following table details key items in a researcher's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for aseptic work and sterilization

| Item | Function & Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sterilizing-Grade Filter | Removal of microorganisms from heat-labile solutions (e.g., serum, antibiotics, buffers) [4] [6] | Pore size of 0.22 µm or less; must be validated via a Bacterial Challenge Test with Brevundimonas diminuta at 10⁷ CFU/cm² [4] [6] |

| Culture Media | Nutrient source for growth of microorganisms. | Must be sterilized, typically by autoclaving, prior to use in experiments to ensure no background growth. |

| Autoclave | Steam sterilization of media, glassware, and other heat-stable items using saturated steam under pressure [4] | Typical validated cycle: 121°C, 15 psi, 15-20 minutes [5]. Effectiveness is quantified by the F-value [4]. |

| Biosafety Cabinet (BSC) | Provides a sterile working environment via HEPA-filtered laminar airflow; protects user and product [5] | Class II BSCs are standard for BSL-2 work; must be certified annually; unidirectional airflow velocity of ~0.45 m/s [4] |

| Disinfectants | Chemical agents used on surfaces and equipment to reduce microbial load (e.g., 70% ethanol, quaternary ammonium compounds) [2] | Used for pre- and post-work surface decontamination. Distinct from sterilants, which destroy all microbial life [2]. |

| Integrity Test Fluid | Used for post-filtration integrity testing of membrane filters via bubble point or pressure hold tests [6] | Confirms the filter was intact and functioned correctly during the filtration process. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Validation is the cornerstone that differentiates a claim of sterility from a scientifically and regulatorily supported fact. The following section outlines core validation methodologies.

Validation of Sterile Filtration

For solutions that cannot be terminally sterilized, filtration through a sterilizing-grade membrane is the method of choice. The validation of this process is critical.

- Objective: To demonstrate that a specific filter will produce a sterile effluent when processing a specific product under defined process conditions [6].

- Critical Parameter: Bacterial Retention.

- Methodology - Bacterial Challenge Test (BCT) [4] [6]:

- Viability Test (VT): First, determine if the product formulation itself is bactericidal or bacteriostatic. The test organism (Brevundimonas diminuta, ATCC 19146, at a challenge level of 10⁷ CFU per cm² of filter surface) is exposed to the product for the duration of the process. If the product affects viability, the test may need to be modified, for instance, by using a product placebo [6].

- Challenge Test: The product, inoculated with the challenge organism, is filtered through the test filter under worst-case process conditions (e.g., maximum filtration time, pressure, and volume).

- Analysis: The filtrate is collected and analyzed for the presence of the challenge organism. The filter must produce a sterile filtrate to pass. The filter's integrity is then verified post-use with a validated method, such as a bubble point test [4].

- Success Criteria: No growth of the challenge organism in the filtrate, demonstrating a log reduction value (LRV) greater than 7 for the organism, corresponding to an SAL of 10⁻⁶ [6].

The workflow for validating a sterile filtration process is multi-staged and rigorous, as shown in the following diagram.

Diagram: Sterile filter validation workflow

Validation of the Aseptic Process (Media Fill)

In pharmaceutical production, the entire aseptic process is validated through a "media fill" or process simulation, which is directly analogous to a researcher's procedure for handling sterile culture media.

- Objective: To demonstrate that the aseptic process, performed by personnel in the actual environment using the same procedures, can consistently produce a sterile product [4].

- Critical Parameter: Sterility of the final simulated product.

- Methodology [4]:

- A sterile growth medium, such as Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), which supports the growth of a wide range of microorganisms, is used instead of the actual product.

- The medium is subjected to all the same steps the product would undergo—filtration (if applicable), transfer, filling, and sealing—by the same operators using the exact same aseptic techniques and equipment.

- The filled units are then incubated to encourage the growth of any contaminating microorganisms that may have been introduced during the process.

- Success Criteria: The number of contaminated units must be within a pre-defined, statistically justified limit. For initial validation, a zero-growth result from a large number of units (e.g., several thousand) is typically required to provide a high confidence level in the aseptic process.

The distinction between "aseptic" and "sterile" is not merely semantic but foundational to quality and safety in microbiological research and pharmaceutical development. Sterile defines the absolute, validated condition of being free from viable microorganisms, a state achieved through rigorous physical or chemical processes. Aseptic describes the dynamic process of protecting that sterile state from contamination during handling. For the researcher at the bench, this means that sterilization methods like autoclaving and filtration create the foundational sterile tools and media, while aseptic technique is the daily practiced discipline that preserves their integrity. Mastering both concepts, and understanding their interdependence, is essential for ensuring the reliability of experimental data, the safety of biopharmaceutical products, and the prevention of healthcare-associated infections. As regulatory frameworks like the EU MDR continue to emphasize usability and risk mitigation, the rigorous application and validation of these principles will only grow in importance [7].

In microbial culture handling research, the core objectives of preventing contamination and ensuring safety are foundational to data integrity, experimental reproducibility, and personnel protection. Contamination compromises the validity of research findings and can lead to erroneous conclusions, while lapses in safety pose significant risks to researchers and the environment. Aseptic technique encompasses the totality of procedures and practices designed to achieve these dual objectives, creating a controlled framework for the manipulation of pure cultures without introducing extraneous microbes or compromising safety [8] [9]. This guide details the technical protocols, environmental controls, and material specifications essential for maintaining sterility and safety within the context of modern microbiological research and drug development.

Foundational Principles and Quantitative Standards

Adherence to established standards is critical for creating a validated research environment. The following tables summarize key quantitative parameters for environmental control and testing.

Table 1: Environmental Control Standards for Aseptic Manipulation

| Parameter | Standard Requirement | Rationale & Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Airborne Particulate Cleanliness | Class 100 (ISO 5) in the direct manipulation zone (e.g., inside a biosafety cabinet or超净工作台). | Minimizes the number of airborne particles that can act as carriers for microorganisms. [9] |

| Background Environment Cleanliness | Class 10,000 (ISO 7) for the room housing the Class 100 zone. | Provides a clean buffer area to support the integrity of the critical zone. [9] |

| Microbiological Environmental Monitoring | Regular monitoring via settle plates, active air sampling, and surface samples. | Validates the effectiveness of cleaning, disinfection, and aseptic practices. [9] |

| Incubator Temperature Control | Typically 30°C - 37°C for common mesophiles, with humidity control to prevent desiccation. | Provides a stable and optimal growth environment for the target microbe, discouraging contaminants. [10] |

| Media Sterilization (Autoclaving) | 121°C for a minimum of 15-30 minutes, depending on load volume. | Validated process to achieve a Sterility Assurance Level (SAL) of 10⁻⁶. [9] |

| Dry Heat Sterilization (Oven) | 160°C for 120 minutes or 170°C for 60 minutes. | Suitable for moisture-impermeable items like metal instruments and glassware. [9] |

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control and Testing

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Growth Media (e.g., Tryptic Soy Broth) | Supports the growth and proliferation of the target microorganisms. | Must undergo growth promotion testing (also known as fertility testing) to demonstrate it can support growth of low-inoculum microbes. [9] [11] |

| Selective Media | Suppresses the growth of non-target microbes while permitting the growth of desired organisms. | Used for the isolation and identification of specific pathogens or microbes from mixed samples. [11] |

| Neutralizers & Inactivators | Added to dilution blanks or rinse fluids to neutralize the effects of residual disinfectants or antimicrobials on samples or equipment. | Critical for accurate microbial recovery; effectiveness must be validated. Common agents include lecithin, polysorbate, and histidine. [9] |

| Chemical Disinfectants (e.g., 70% Alcohol, quaternary ammonium compounds) | Used for surface decontamination and hand sanitization within the lab. | 70% alcohol is preferred for its efficacy and rapid evaporation; surfaces must be cleaned of organic matter before application. [8] |

| Sterile Water for Injection | Used in media preparation and as a diluent in microbiological tests. | Its high purity ensures no introduction of interfering substances or contaminants. [10] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Aseptic Transfer via Streak Plate Method

This protocol is fundamental for isolating individual bacterial colonies from a mixed culture or stock.

Key Materials:

- Sterile Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) plates [9]

- Inoculating loop (metal or disposable)

- Bunsen burner or Bacti-Cinerator

- Target microbial culture (e.g., Escherichia coli)

- 70% ethanol for surface disinfection [8]

- Biohazard waste container

Methodology:

- Preparation: Disinfect the work surface with 70% ethanol. Place all required materials in the超净工作台 or near the Bunsen burner and turn on the UV light for at least 30 minutes prior to use. [8]

- Inoculating Loop Sterilization: Flame the inoculating loop from the base to the tip until it is red-hot throughout. Allow it to cool for 10-15 seconds without placing it down or blowing on it. [8]

- Sample Collection: Hold the stock culture tube in one hand. Use the little finger of the hand holding the loop to remove the cap of the tube. Briefly pass the lip of the tube through the flame to create an air current that prevents contamination. Gently dip the cooled loop into the culture broth or a single colony.

- Streaking: Lift the lid of the agar plate just enough to allow the loop to enter. Streak the inoculum in a defined pattern (e.g., four-quadrant method) to sequentially dilute the bacteria across the plate. Between quadrants, re-flame and cool the loop. [8]

- Incubation: Replace the lid, and secure it with parafilm if necessary. Invert the plate and incubate at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 35°C) for 24-48 hours. [9]

- Waste Disposal: Sterilize all used metal loops by re-flaming. Dispose of all plastic consumables and cultures in a biohazard bag for autoclaving before disposal. [9]

Protocol for Method Suitability Testing (无菌检验方法适用性试验)

This test is mandatory to demonstrate that a product or sample itself does not inhibit the growth of microorganisms during sterility testing, thereby preventing false negatives. [9]

Key Materials:

- Test sample (the product to be tested for sterility)

- Culture media: Tryptic Soy Broth (for bacteria) and Sabouraud Dextrose Broth (for fungi) [9]

- Challenge microorganisms (as per pharmacopoeia, typically <100 CFU):

- Membrane filtration apparatus or direct inoculation tubes

- Incubators set at 30-35°C (for bacteria) and 20-25°C (for fungi)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the test sample according to the defined protocol, which may involve dissolving, diluting, or otherwise processing it.

- Inoculation: Divide the prepared sample into two portions.

- Test Group: Inoculate the first portion with a small number (fewer than 100 CFU) of one of the challenge microorganisms.

- Control Group: The second portion is not inoculated and serves as a negative control to confirm the initial sterility of the sample and media.

- Incubation & Observation: Incubate all containers for no less than 14 days. [9] Observe them periodically for visual evidence of microbial growth (turbidity).

- Results Interpretation: The test is valid only if the control group remains sterile and the test group shows clear growth of the challenge microorganism. Growth in the test group must be comparable to a growth control (microbe in media without product) and occur within the specified time frame. If the test sample inhibits growth in the test group, the method must be modified (e.g., by increasing dilution, adding a larger volume of rinse fluid in membrane filtration, or using a specific neutralizer) and the test repeated until no inhibition is observed. [9]

Workflow Visualizations

Aseptic Technique Core Logic

This diagram outlines the fundamental decision-making process and dual objectives underpinning all aseptic techniques.

Sterility Test Method Suitability Workflow

This flowchart details the step-by-step procedure for validating a sterility test method, a critical GMP requirement.

Advanced Techniques: Leveraging Microfluidic Platforms

Modern research employs advanced engineering solutions to enhance control and throughput. Droplet microfluidic technology involves generating and manipulating picoliter-to-nanoliter volume droplets within microchannels, serving as isolated micro-reactors. [12]

Key Materials:

- Microfluidic device (PDMS or glass)

- Oil phase (carrier fluid, e.g., fluorinated oil with surfactant)

- Aqueous phase (containing cells, culture media, and reagents)

- Precision syringe pumps

- Microscopy setup for incubation and monitoring

Methodology:

- Droplet Generation: The aqueous phase containing a highly diluted suspension of microbial cells and nutrients is injected alongside the oil phase into a microfluidic device. At the junction, highly monodisperse water-in-oil droplets are generated at high frequencies (up to 20,000 Hz). [12]

- Incubation: The droplets are collected in a capillary tube or off-chip reservoir and incubated. Each droplet functions as a miniature, isolated bioreactor. [12]

- Analysis & Sorting: After incubation, droplets can be reinjected into a microfluidic sorter. Based on an optical signal (e.g., fluorescence from a reporter gene or a metabolic dye), droplets containing cells with desired traits (e.g., high growth, specific enzyme activity) are electrically or piezoelectrically deflected and collected for further culture or genomic analysis (e.g., MaPS-seq, Microbe-seq). [12]

This platform's inherent containment drastically reduces cross-contamination risks and enables high-resolution, single-cell analysis, pushing the boundaries of aseptic investigation in complex microbiomes. [12]

Within the critical field of microbial culture handling, the integrity of research and drug development hinges on the purity of cell cultures. Contamination by bacteria, fungi, and mycoplasma represents a pervasive threat, capable of compromising experimental data, jeopardizing product safety, and invalidating years of research [13]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these common contaminants, framing their identification and control within the essential context of aseptic technique. For researchers and scientists, understanding these adversaries is the first line of defense in ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of their work. The following sections will detail the sources and detection methods for each contaminant, provide structured protocols for monitoring, and visualize the workflows integral to maintaining uncontaminated cultures.

Understanding the specific profiles of common contaminants is fundamental to their control. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of bacteria, fungi, and mycoplasma.

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Cell Culture Contaminants

| Contaminant | Common Examples | Primary Sources | Key Detection Methods | Visible & Morphological Clues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Escherichia coli, Bacillus species, Staphylococcus epidermis [14] | Lab personnel, unfiltered air, contaminated water baths, non-sterile reagents [13] [14] | Microbial culture, Gram's stain, visual turbidity, pH change (acidic) [13] | Cloudy (turbid) culture medium; rapid color change (yellow) of phenol red pH indicator [13] [14] |

| Fungi | Yeasts (e.g., Candida), Molds (e.g., Aspergillus, Penicillium) [14] | Airborne spores, lab personnel, humidified incubators, cellulose products [13] [14] | Microbial culture, visual observation of mycelia or turbidity, odor [13] | Fuzzy, filamentous patches (molds); oval, budding particles smaller than cells (yeasts) [14] |

| Mycoplasma | M. fermentans, M. orale, M. arginini, M. hyorhinis [15] [14] | Contaminated cell lines, animal-derived reagents (e.g., serum), lab personnel [13] [14] | PCR, Hoechst staining, specialized mycoplasma detection kits, microbial culture [13] [15] | No visible change under standard microscope; subtle effects like altered cell growth rates, morphology, and metabolism [14] |

Bacterial Contamination

Bacterial contamination is a prevalent issue characterized by its rapid growth. The nutrients in cell culture media provide an ideal environment for bacteria to proliferate, often leading to visible turbidity and a sharp drop in media pH, turning it yellow [13] [14]. These contaminants are typically introduced through lapses in aseptic technique, such as from laboratory personnel, unfiltered air, or contaminated equipment like water baths used for warming media [13].

Fungal Contamination

Fungal contamination encompasses both yeasts and molds. Yeasts, such as Candida, are single-celled eukaryotes that reproduce by budding and can cause turbidity in the media without an immediate color change [14]. Molds, like Aspergillus, form multicellular, filamentous structures (hyphae) that appear as fuzzy dots or patches [14]. Their spores are ubiquitous in the environment and can be introduced through airborne transmission or contaminated surfaces [13].

Mycoplasma Contamination

Mycoplasma contamination is particularly insidious. As some of the smallest self-replicating organisms lacking a cell wall, they are resistant to many common antibiotics and can pass through standard microbiological filters [15] [14]. They do not cause visible turbidity or immediate cell death, making them difficult to detect without specific testing [14]. However, they profoundly affect cellular functions, altering gene expression, protein synthesis, and metabolism, which can severely impact the quality and reliability of research data [14]. It is estimated that 15–35% of continuous cell lines are infected with mycoplasma, often originating from contaminated reagents or operator cross-contamination [14].

Experimental Protocols for Contaminant Identification

Routine monitoring is critical for early contaminant detection. The following protocols outline standard methodologies for identifying bacterial, fungal, and mycoplasma contamination.

Visual and Microscopic Inspection

Daily visual inspection of cultures is the first line of defense.

- Procedure: Examine culture flasks under a light microscope for changes in cell morphology, adherence, and the presence of foreign particles [14]. Look for media turbidity (bacteria, yeast), filamentous structures (mold), or unexpected pH changes indicated by phenol red [13] [14].

- Note: Mycoplasma will not be visible with this method.

Microbial Culture for Bacteria and Fungi

This method confirms the presence of cultivable microbes.

- Procedure:

- Under aseptic conditions, take a small aliquot (e.g., 100 µL) from the suspect culture.

- Inoculate onto nutrient-rich agar plates (e.g., blood agar, tryptic soy agar).

- Incubate plates at 37°C for 24-48 hours and observe for bacterial or fungal colony formation [13].

- Interpretation: The growth of distinct colonies indicates contamination. Further identification can be performed via Gram staining or other microbiological tests.

Hoechst Staining for Mycoplasma Detection

Mycoplasma, while invisible under standard microscopy, can be detected using DNA-binding fluorescent stains like Hoechst 33258.

- Procedure:

- Grow cells on a sterile coverslip in a culture dish.

- Fix the cells with a fixative such as acetic acid/ethanol or methanol.

- Stain with Hoechst stain according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- Mount the coverslip and observe under a fluorescence microscope [13].

- Interpretation: The nuclei of the host cells will fluoresce brightly. Mycoplasma contamination appears as a fine, particulate or filamentous fluorescence in the cytoplasm and surrounding the cell membranes [13]. Uncontaminated cells will show clean nuclear staining without this extranuclear fluorescence.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for Mycoplasma

PCR is a highly sensitive and specific method for detecting mycoplasma DNA.

- Procedure:

- Interpretation: The presence of a band of the expected size indicates mycoplasma contamination. Commercial mycoplasma detection kits based on PCR are widely available and provide robust protocols [15].

Workflow Visualization for Contaminant Identification

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for identifying and responding to potential contamination in cell culture, integrating the protocols described above.

Diagram 1: Contaminant identification and response workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Effective contamination control relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items essential for prevention, detection, and decontamination.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 70% Ethanol (EtOH) | Surface and glove disinfection; works by denaturing proteins and dissolving lipids [15]. | Most effective concentration; 100% EtOH is less effective as it causes rapid surface protein coagulation [15]. |

| Antibiotics (e.g., Penicillin/Streptomycin) | Added to media to suppress bacterial growth [13]. | Not effective against mycoplasma; overuse can mask lapses in aseptic technique [15]. |

| Antimycotics | Added to media to suppress fungal and yeast growth [13]. | Used as a preventive measure, not a cure for established contamination. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kits | Commercial kits for routine testing via PCR, ELISA, or enzymatic methods [15] [14]. | Essential for quarantining new cell lines and regular monitoring of established cultures. |

| Hoechst 33258 Stain | Fluorescent DNA stain used to detect mycoplasma contamination under a microscope [13]. | Reveals characteristic extranuclear fluorescence pattern of mycoplasma. |

| Gamma-Irradiated Serum | Animal serum treated to inactivate viruses, mycoplasma, and other contaminants [13]. | Critical for preventing introduction of contaminants from animal-derived reagents. |

Vigilance against contamination is a non-negotiable aspect of rigorous scientific practice. As detailed in this guide, bacteria, fungi, and mycoplasma each present unique challenges that require specific detection strategies, from simple visual checks to sophisticated molecular tests. However, the cornerstone of effective contamination control remains unwavering adherence to strict aseptic technique. By integrating the profiling, protocols, and workflows outlined herein, researchers and drug development professionals can fortify their defenses, safeguard their cultures, and ensure the integrity of their critical work in microbial culture handling.

In microbial culture handling, the integrity of research and drug development outcomes hinges on the rigorous application of aseptic techniques. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of two cornerstone tools for maintaining sterility: the Bunsen burner and the laminar flow hood. We delineate their fundamental principles, distinct roles, and operational protocols within a modern microbiology laboratory. While the Bunsen burner creates a localized sterile environment through convection currents and direct flaming, laminar flow hoods offer a controlled, HEPA-filtered workspace for more sensitive or hazardous procedures. This guide details explicit methodologies for their use, supported by comparative data and workflow visualizations, to empower researchers in selecting and implementing the appropriate aseptic strategy for their specific applications.

Aseptic technique comprises a set of carefully designed procedures to prevent contamination of pure cultures, sterile media stocks, and other solutions by unwanted microorganisms (i.e., sepsis) [16] [17]. It simultaneously acts as a critical biosafety measure, reducing the potential for transmission of microorganisms to researchers, which is paramount when working with pathogens [18]. These techniques are fundamental to the accuracy and reproducibility of experiments in microbiology, biotechnology, and pharmaceutical development [19] [20].

It is crucial to distinguish aseptic technique from sterile technique. Sterile technique refers to the complete elimination or destruction of all microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and spores, and is applied to create a sterile starting state, often through methods like autoclaving, dry heat, or filtration [21] [20]. Aseptic technique, conversely, is a continuous practice focused on maintaining that sterility by preventing the introduction of contaminants during experimental procedures [21] [20]. In essence, sterile techniques provide the initial clean slate, while aseptic techniques preserve it throughout the research process.

The Bunsen Burner: Principle and Applications

The Bunsen burner, a staple of microbiology laboratories for over a century, provides a pragmatic and effective means of establishing a localized aseptic work area on an open bench [17].

Core Mechanism and Function

The primary aseptic function of a lit Bunsen burner is the creation of a convection current of hot air above and around the laboratory bench [22] [19] [17]. This upward airflow draws ambient air and any suspended dust or microbial particles upward and away from the immediate work zone, thereby reducing their viability and the likelihood of them settling into open cultures or media [19] [17]. Furthermore, the intensely hot flame serves as an immediate and effective method for sterilizing tools such as inoculating loops and the necks of glass bottles and test tubes [22] [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Inoculating an Agar Plate

The following protocol is a standard procedure for transferring microorganisms using a Bunsen burner.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Bunsen burner connected to gas source

- Inoculating loop (metal)

- Source culture (e.g., in a broth or on an agar slant)

- Sterile agar plate

- Striker or lighter

- Lab coat, gloves, and safety goggles [18]

Methodology:

- Preparation: Disinfect the work surface with 70% ethanol and ensure all materials are within immediate reach [17]. Light the Bunsen burner to create a sterile convection zone [19].

- Sterilize the Loop: Hold the inoculating loop in the Bunsen burner flame. Begin with the tip in the cooler, light blue cone of the flame, then slowly draw the rest of the wire upward into the hottest region (immediately above the blue cone) until the entire wire is glowing red hot [17]. This gradual heating prevents culture residue from sputtering and forming an aerosol.

- Cool the Loop: Allow the sterilized loop to cool for a few seconds in the air near the burner. Do not wave it around or place it on a non-sterile surface [17].

- Obtain Inoculum: With your free hand, pick up the source culture tube. Using the little finger of the hand holding the loop, remove the cap or cotton plug of the tube. Briefly pass the neck of the tube through the Bunsen burner flame to create an airflow outward [17]. Insert the cooled loop into the tube to pick up a small sample of the culture.

- Inoculate the Plate: Lift the lid of the sterile agar plate just enough to allow the loop to enter, angling the lid to shield the agar surface from airborne contaminants [22] [17]. Gently streak the sample onto the surface of the agar using a standard streaking pattern to isolate colonies.

- Final Sterilization: After streaking, remove the loop and re-sterilize it completely in the Bunsen burner flame before setting it down. This destroys any remaining microorganisms, preventing environmental contamination [17].

- Incubation: Seal the agar plate with parafilm or tape and place it in an incubator set to the appropriate temperature for the microorganism.

The Laminar Flow Hood: Principle and Applications

Laminar flow hoods (or cabinets) provide a sophisticated, enclosed workspace that offers a higher degree of sterility and, in the case of Class II cabinets, operator protection [22] [23] [21].

Core Mechanism and Function

A laminar flow hood maintains sterility by generating a continuous, unidirectional stream of HEPA-filtered air across the work surface [19] [17]. A certified High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filter is capable of capturing a minimum of 99.97% of airborne particles larger than 0.3 μm, including dust, pollen, mold, and bacteria [17]. This creates an ultraclean environment for handling sensitive biological materials, protecting both the experiment (product protection) and, in specific cabinet types, the researcher from exposure to hazardous agents (operator protection) [24] [23] [21]. It is critical to note that the use of a Bunsen burner within a laminar flow hood is generally not recommended, as the heat can disrupt the laminar airflow, potentially cause damage to the HEPA filter, and compromise the cabinet's ability to provide sterility and safety [23] [21].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Aseptic Media Transfer

This protocol outlines the procedure for transferring sterile liquid media within a laminar flow hood.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Class II Laminar Flow Hood (or similar)

- Sterile media in a bottle

- Sterile recipient flask or Petri dishes

- Sterile disposable serological pipettes and a pipettor

- 70% Ethanol spray and lint-free wipes

- Waste container for used pipettes

- Appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) [21]

Methodology:

- Preparation and Sterilization: Turn on the laminar flow hood and allow it to run for at least 15 minutes to purge airborne contaminants. Wipe down all interior surfaces, including the back and side walls, with 70% ethanol [21]. Some protocols include ultraviolet (UV) light sterilization of the exposed work surface before beginning [21].

- Introduction of Materials: Place all necessary materials into the cabinet after wiping their exteriors with 70% ethanol [21]. Arrange them in a logical, uncluttered workflow, ensuring they do not block airflow grilles. Keep the work area free of unnecessary items [21].

- Aseptic Transfer: Work slowly and deliberately to minimize turbulence. To transfer media, uncap the sterile media bottle and the recipient vessel. Use a sterile serological pipette and pipettor to aspirate the required volume. Avoid touching the tip of the pipette against the non-sterile threads of the bottle or any other non-sterile surface [21] [17]. Dispense the media into the recipient vessel and promptly recap both containers. Each sterile pipette should be used only once to prevent cross-contamination [21].

- Completion: Once the procedure is complete, immediately remove all equipment, including any waste (e.g., used pipettes), from the work area. Wipe down the interior surfaces of the hood with 70% ethanol once more. Leave the hood running for several minutes to clear any particulates before shutting it off [21].

Comparative Analysis: Bunsen Burner vs. Laminar Flow Hood

The choice between a Bunsen burner and a laminar flow hood depends on the specific requirements of the procedure, the nature of the biological agents, and available resources.

Table 1: Tool Comparison for Aseptic Technique

| Feature | Bunsen Burner | Laminar Flow Hood |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Creates upward convection currents of hot air [19] [17] | Provides a continuous stream of HEPA-filtered, particulate-free air [19] [17] |

| Sterilization Method | Direct flaming (e.g., loops, needle, glass necks) [22] [17] | Surface disinfection (e.g., with 70% ethanol); no open flames recommended [23] [21] |

| Level of Protection | Protects the experiment (product) only; no operator protection [23] | Class II cabinets offer both product and operator protection [23] [21] |

| Ideal for | Routine microbiology on non-pathogenic cultures (e.g., inoculation, streaking) [16] | Handling sensitive, hazardous, or expensive biological materials; cell culture; pharmaceutical prep [19] [21] |

| Cost & Complexity | Low cost, simple setup and operation [17] | High initial and maintenance cost; requires regular certification [19] |

| Flaming in Hood | N/A | Not recommended; disrupts airflow, risks HEPA filter damage, and is unsafe with plasticware [23] [21] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful aseptic work relies on a suite of supporting reagents and materials. The following table details key items essential for experiments in this field.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Aseptic Microbial Culture

| Item | Function in Aseptic Technique |

|---|---|

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Protects the operator and prevents the introduction of contaminants from skin and clothing. Includes lab coats, gloves, and safety goggles [24] [21] [18]. |

| 70% Ethanol | A fast-acting disinfectant used to wipe down work surfaces, gloved hands, and the exteriors of containers before they are placed in the sterile work area [19] [21] [17]. |

| Autoclave | A sterilization device that uses pressurized steam at 121°C to eliminate all microorganisms, including resistant spores. Used to sterilize glassware, media, and solutions before use [22] [24] [20]. |

| Inoculating Loops/Needles | Tools for transferring and streaking microorganisms. Metal loops are sterilized by flaming, while disposable plastic loops are pre-sterilized [22] [17]. |

| Sterile Serological Pipettes | Used for accurate, aseptic transfer of liquid media and reagents. Designed for single use to prevent cross-contamination [22] [21] [17]. |

| Agar Plates & Culture Media | Provide the nutritional environment for microbial growth. Must be pre-sterilized and handled aseptically to prevent contamination [22] [19]. |

Both the Bunsen burner and the laminar flow hood are indispensable tools in the microbiologist's arsenal, each serving a distinct purpose in the overarching framework of aseptic technique. The Bunsen burner remains a cost-effective and reliable method for establishing a sterile field for basic microbiological procedures on the open bench. In contrast, the laminar flow hood offers a superior, controlled environment for handling sensitive, valuable, or potentially hazardous biological materials while ensuring researcher safety. The informed selection and correct application of these tools, in conjunction with disciplined aseptic practices, are fundamental to ensuring data integrity, reproducibility, and safety in microbial research and drug development.

Within microbiological research and pharmaceutical development, the accurate study of microorganisms hinges on the ability to work with uncontaminated, well-defined biological systems. The triad of pure culture, sterilization, and disinfection forms the cornerstone of all aseptic techniques, ensuring the integrity of experimental data and the safety of both personnel and products [25] [26]. A pure culture, defined as a laboratory culture containing only a single species of organism, is a prerequisite for characterizing physiology, identifying pathogens, and producing consistent, reproducible results in both research and industrial applications like antibiotic and vaccine production [25] [27]. The processes of sterilization and disinfection are the critical barriers that protect these pure cultures from contamination and prevent environmental release [28] [26]. This guide details the core principles, methods, and practical protocols that underpin these foundational concepts, framed within the essential context of aseptic technique for advanced research and drug development.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Pure Culture

A pure culture is a population of microorganisms that arises from a single precursor cell and is therefore genetically identical [25]. In practical laboratory terms, it contains only one species or strain of microbe, free from any contaminating organisms [27]. The isolation and maintenance of pure cultures are fundamental to microbiology, as they allow for the precise study of an organism's characteristics, its role in disease, its metabolic pathways, and its potential industrial applications [29] [25]. Obtaining a pure culture is the first critical step in fulfilling Koch's postulates to establish the cause of an infectious disease and is equally vital in drug development for ensuring the consistent quality of cell-based therapies and fermentation products [25].

Aseptic Technique

Aseptic technique is the overarching set of procedures and protocols designed to prevent the introduction of contaminating microorganisms into pure cultures, sterile media, and the laboratory environment [29] [26]. The term "aseptic" literally means "without contamination" [26]. The goals are two-fold: to prevent environmental microbes from contaminating the cultures being studied and to prevent the cultured microbes from escaping into the environment [29]. Proper aseptic technique is non-negotiable in a research setting, as contaminated cultures yield unreliable and worthless data, compromising experimental validity and diagnostic accuracy [29]. These techniques encompass all actions in the lab, from flame sterilization and proper tube transfer to the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and the management of the workspace [29] [30].

Sterilization vs. Disinfection

While both sterilization and disinfection are decontamination processes, they differ fundamentally in their objectives and outcomes. Understanding this distinction is critical for applying the correct level of microbial control.

Sterilization is an absolute process that aims to completely destroy or eliminate all forms of microbial life, including highly resistant bacterial endospores and viruses [28] [26] [31]. An item is either sterile or it is not; there is no middle ground. Sterilization is typically achieved by physical methods such as steam autoclaving, dry heat, radiation, or filtration [26] [31]. It is essential for all culture media, surgical instruments, and any item that must be completely free of viable microbes [31].

Disinfection is a relative process that reduces the number of pathogenic microorganisms on inanimate objects or surfaces to a level considered safe for public health [28] [31]. It does not necessarily eliminate all microbial forms, particularly bacterial spores [28]. Disinfection is usually accomplished using chemical agents like chlorine, alcohol, or iodine-based solutions [28] [31].

Table 1: Key Differences Between Sterilization and Disinfection

| Characteristic | Sterilization | Disinfection |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Achieve absolute sterility; eliminate all microbial life [28] [31] | Reduce pathogens to a safe level [31] |

| Target Microorganisms | All microorganisms, including bacterial spores and viruses [28] [26] | Primarily vegetative bacteria, fungi, and viruses; generally not spores [28] |

| Method Examples | Autoclaving (steam under pressure), dry heat ovens, ethylene oxide gas, gamma radiation [26] [31] | Chemical disinfectants (e.g., bleach, alcohol), boiling, UV radiation [28] [31] |

| Application Context | Preparation of culture media, surgical instruments, pharmaceutical products [26] [31] | Decontaminating laboratory benches, clinical surfaces, non-critical patient care equipment [28] [26] |

| Status of Item | Sterile [26] | Disinfected, but not sterile [28] |

Essential Methods and Protocols

Methods for Obtaining a Pure Culture

The transition from a mixed population in a natural sample to a pure culture in the laboratory requires specific isolation techniques, primarily involving mechanical dilution on a solid surface.

Streak Plate Method

The streak plate method is a rapid, simple, and widely used technique for mechanically diluting a concentrated sample of microorganisms across the surface of an agar plate to obtain isolated colonies [29] [25]. The goal is to reduce the microbial population with each successive streak series until individual cells are separated and can grow into discrete, well-isolated colonies presumed to arise from a single cell [29].

Detailed Protocol: Three-Phase Streak Plate

- Step 1: Flame an inoculating loop until it is red-hot to sterilize it. Allow the loop to cool for 15-30 seconds to avoid killing the sample microbes [29].

- Step 2: Lift the lid of the source plate (e.g., a mixed culture) just enough to insert the loop. Pick up a small amount of the microbial growth or a loopful of a broth culture. Avoid digging into the agar. Immediately replace the lid [29].

- Step 3: Position a fresh, sterile agar plate in front of you. Lift its lid slightly and smear the inoculum in a small area (the "first phase" or "initial streak") over approximately one-quarter of the plate surface [29].

- Step 4: Re-flame the loop to sterilize it and let it cool. Rotate the plate about 90 degrees. Drag the loop through the edge of the first phase a few times and then streak into the adjacent, untouched agar surface (the "second phase") in a continuous pattern, further diluting the sample [29].

- Step 5: Re-flame and cool the loop again. Rotate the plate another 90 degrees. Drag the loop through the edge of the second phase and streak into the final untouched quadrant (the "third phase") [29].

- Step 6: Replace the plate lid, and flame the loop to sterilize it. Incubate the plate under appropriate conditions. After incubation, well-isolated colonies in the third phase should be pure and available for subculturing [29].

Pour Plate and Spread Plate Methods

Two other common techniques for isolation and enumeration are the pour plate and spread plate methods [29] [25].

- Pour Plate Method: A sample (typically serially diluted) is mixed with molten, cooled agar and poured into an empty, sterile petri dish. Colonies grow both within the agar and on its surface [25].

- Spread Plate Method: A small volume of a diluted liquid sample is pipetted onto the surface of a pre-poured, solid agar plate and then spread evenly using a sterile, L-shaped glass or plastic rod (spreader). Colonies grow only on the agar surface [25].

Sterilization Techniques

Sterilization is achieved through physical and chemical methods that are lethal to all microbial life.

- Autoclaving (Moist Heat Sterilization): This is the most common and effective method for sterilizing culture media, aqueous solutions, and laboratory glassware. An autoclave uses saturated steam under pressure (typically 15 psi at 121°C) for a minimum of 20 minutes to ensure destruction of all vegetative cells and endospores [26]. The critical factor is the direct contact of the steam with all surfaces of the items to be sterilized [26].

- Dry Heat Sterilization: Performed in a hot-air oven, this method (e.g., 160-170°C for 2-4 hours) is used for materials that might be damaged by moist heat or are impervious to steam, such as powders, oils, and sharp instruments [31].

- Chemical Sterilants: Heat-sensitive materials (e.g., some plastics, optical devices) can be sterilized using chemical gases like ethylene oxide or liquids like glutaraldehyde [31]. These are highly effective but require careful handling and aeration.

- Filtration: Fluids that would be degraded by heat (e.g., serum, antibiotic solutions) can be sterilized by passage through a membrane filter with pores small enough (typically 0.22 µm) to physically retain bacteria and larger microorganisms [31].

Disinfection Practices

Disinfection in the laboratory is primarily chemical-based and targeted at work surfaces and non-critical equipment.

- Surface Decontamination: Laboratory benches are routinely disinfected before and after work using a 10% bleach solution or commercial disinfectants like chlorine-based compounds or quaternary ammonium compounds [26] [32].

- Antiseptics: While disinfectants are for inanimate surfaces, antiseptics are lower-toxicity antimicrobial chemicals (e.g., chlorhexidine, iodine, 70% alcohol) applied to living tissue, such as a researcher's skin, to prevent infection [28] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful microbial culture handling relies on a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table details key items essential for maintaining asepsis and performing core techniques.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Agar | A polysaccharide extracted from red algae; used as a solidifying agent for culture media because it is not metabolized by most microbes and provides a transparent, solid surface for colony growth [26]. |

| Growth Media (Broth & Agar) | Nutrient-rich substances, either liquid (broth) or solidified with agar, designed to support microbial growth. Can be general-purpose or selective/differential for specific organisms [26]. |

| Autoclave | A high-pressure device that uses steam to achieve temperatures above the boiling point of water (typically 121°C) for the sterilization of media, solutions, and labware [26] [31]. |

| Chemical Disinfectants | Solutions such as chlorine bleach, alcohol, and hydrogen peroxide used to decontaminate non-living surfaces like laboratory benches to reduce the microbial load [28] [26] [32]. |

| Bunsen Burner | Used for flame sterilization of inoculating loops and needles, and to create a convective updraft that reduces airborne contamination in the immediate work area [29] [32]. |

| Inoculating Loop/Needle | Tools, typically metal or disposable plastic, used to transfer and inoculate microbial samples. They are sterilized by flaming before and after each transfer [29]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Gloves, lab coats, masks, and safety glasses worn to protect the researcher from microbial exposure and to prevent personal contaminants from entering the cultures [30] [32]. |

| Aseptic Connectors | Devices like MicroCNX connectors used in advanced systems (e.g., bioreactors) to maintain a sterile fluid path between components, which is critical for automated sampling in cell therapy manufacturing [33]. |

Advanced Application: Aseptic Technique in Cell Therapy Manufacturing

The principles of asepsis are pushed to their technological limits in the production of advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) like Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies [33]. In these processes, autologous cells are expanded ex vivo and infused back into a patient, making the prevention of contamination paramount for patient safety. Manual sampling from microbioreactors for process monitoring introduces risks of operator variability and contamination [33]. This has driven the development of automated, closed systems.

The Automated Cell Culture Sampling System (Auto-CeSS) exemplifies the integration of foundational aseptic principles with modern engineering [33]. This system addresses the challenge of small-volume sampling (as low as 30 µL) from scaled-down microbioreactors with limited starting material. It maintains sterility through defined aseptic points (APs), such as sterile connectors, and uses automated pinch valves and peristaltic pumps to transfer samples without exposing the culture to the open environment [33]. This application demonstrates how core concepts of asepsis are adapted to ensure sterility, consistency, and regulatory compliance in cutting-edge pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Workflow and Procedural Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for isolating and working with a pure culture, integrating the core concepts and techniques discussed.

Diagram 1: Pure Culture Isolation Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps for obtaining a pure culture from a mixed sample, highlighting the cyclical nature of purity assessment and the constant role of disinfection.

The foundational concepts of pure culture, sterilization, and disinfection are inextricably linked and form the non-negotiable basis of all rigorous microbiological research and biopharmaceutical development. Mastering the theoretical principles and practical protocols outlined in this guide—from performing a flawless streak plate and understanding the absolute nature of sterilization to implementing aseptic technique in both manual and automated systems—is essential for any researcher or scientist. The integrity of experimental data, the safety of novel therapeutics like CAR-T cells, and the reliability of diagnostic outcomes all depend on the consistent and correct application of these core techniques. As the field advances with increased automation and complexity, these foundational principles remain the constant bedrock upon which scientific progress and product quality are built.

Procedures in Practice: A Step-by-Step Guide to Aseptic Microbial Transfers and Cell Culture

In microbiological and cell culture research, aseptic technique is the cornerstone of reliable and reproducible results. This comprehensive set of practices is designed to prevent microbial contamination of cultures and protect researchers from potential infection [34] [35]. Within a laboratory context, aseptic technique encompasses all aspects of environmental control, including personal hygiene, equipment and media sterilization, workspace disinfection, and associated quality control procedures [35]. The constant challenge of microbial contamination necessitates rigorous protocols, particularly when working with mammalian cell cultures, which are highly susceptible to contamination by bacteria, fungi, and viruses [36].

The consequences of contamination are far-reaching, leading to wasted resources, compromised experimental data, and potential biological hazards [36] [37]. In industrial settings such as pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, contamination can compromise product quality and pose significant health risks [37]. Therefore, a robust aseptic technique, centered on proper workspace disinfection and the correct use of laminar flow containment devices, is not merely a best practice but an essential requirement for any research involving microbial or cell cultures [36] [34] [35].

This guide details the critical procedures for preparing a sterile workspace, with a specific focus on the management and disinfection of laminar flow hoods—one of the most important pieces of equipment in a cell culture lab [36].

Laminar Flow Hoods: Types and Principles

Fundamental Principles and Components

A laminar flow hood is an enclosed workspace designed to provide a sterile environment through the constant, unidirectional flow of HEPA-filtered air [36] [38]. The High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filter is the core component, capable of trapping and removing 99.97% of airborne particles that are 0.3 micrometers or larger, including dust, microbes, and other contaminants [36] [39]. This creates an ISO Class 5 environment, which contains no more than 3,520 particles (≥0.5 µm) per cubic meter of air [39].

The fundamental components of a horizontal laminar flow hood include:

- Work Surface: The stainless-steel surface where all procedures are performed [40].

- Prefilter: Located at the front or top of the hood, it captures large particles of dust and debris to extend the life of the more expensive HEPA filter [40].

- Blower/Fan: Sealed within the cabinet, it draws room air through the prefilter and pushes it through the HEPA filter [40].

- HEPA Filter: Positioned at the rear, it traps microscopic contaminants to create sterile air for the workspace [40].

Selecting the Appropriate Containment Device

It is critical to distinguish between different types of laminar flow hoods, as they offer varying levels of protection. The table below summarizes the key classes and their appropriate applications.

Table: Classification and Selection of Laminar Flow Hoods and Biosafety Cabinets

| Class/Type | Airflow Principle | Protection Offered | Typical Biosafety Level | Suitability for Cell Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clean Bench (Horizontal/Vertical) | HEPA-filtered air blown from back/across work surface toward user [36] [38]. | Product only; exposes user to aerosols [36] [38]. | N/A | Not suitable for mammalian cell culture or handling of potentially hazardous materials [36] [38]. |

| Class I Biosafety Cabinet | Unfiltered lab air flows inward over the product; HEPA-filtered exhaust [36] [38]. | Personnel and environment; does not protect cultures from contamination [36] [38]. | BSL-1, 2, 3 [36] | Not suitable for cell and tissue culture work [36] [38]. |

| Class II Biosafety Cabinet | HEPA-filtered air flows downward (inflow) and across work surface (laminar flow); HEPA-filtered exhaust [36] [38]. | Personnel, environment, and the culture [36] [38]. | BSL-1, 2, 3 [36] | The standard for most cell culture work (e.g., primate-derived, virally infected cultures) [36] [38]. |

| Class III Biosafety Cabinet | Gas-tight; supply and exhaust air are HEPA filtered; operators use attached gloves [36]. | Maximum protection for personnel, environment, and culture [36]. | BSL-4 [36] | Required for work involving known human pathogens [36]. |

For most cell culture applications involving moderate-risk agents, a Class II Biosafety Cabinet (BSC) is recommended [36] [38]. The following decision diagram outlines the selection logic based on the biological agents being handled.

Disinfection and Cleaning Protocols

Pre-Work Preparation and Personal Hygiene

Contamination control begins before approaching the laminar flow hood. Researchers must adhere to strict personal hygiene and garbing procedures:

- Apparel: No eating, drinking, or smoking in the laboratory. Wear a dedicated lab coat or disposable gown to protect your clothing and the workspace [34].

- Hand Hygiene: Always wash hands thoroughly with a suitable cleansing agent (e.g., chlorhexidine gluconate) before and after handling cultures and upon removing gloves [34] [40].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear disposable gloves and safety goggles. In clean rooms, don additional PPE such as shoe covers, hair covers, and face masks in the anteroom before entering [34] [37] [40].

Hood Cleaning Procedure: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Proper cleaning of the laminar flow hood is vital to maintaining sterility. The following protocol, based on USP Chapter <797> guidelines and manufacturer recommendations, should be performed at the beginning of every shift, before every batch compounding session, and every 30 minutes during continuous compounding activities [40].

Table: Essential Supplies for Laminar Flow Hood Cleaning

| Supply Item | Specification | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cleaning Wipes | Lint-free, non-shedding, and aseptic (e.g., sterile gauze) [40] [41]. | To apply disinfectants without introducing fibers or contaminants. |

| Sterile 70% IPA | Supplied in a pour bottle that can be recapped [40] [41]. | Primary disinfectant; kills or inhibits microorganisms [40]. |

| Sterile Water | Purified and sterilized [40]. | Removes sticky residues insoluble in IPA [40]. |

| Disinfectant Spray | e.g., 70% Ethanol [41]. | To neutralize airborne charges and disinfect surfaces before wiping. |

The workflow for the cleaning procedure is methodical and must be followed precisely to ensure all surfaces are decontaminated.

Detailed Cleaning Steps:

- Gather and Transport Supplies: In the anteroom, gather all essential hood-cleaning supplies. Wipe down the exterior surfaces of all supply containers (e.g., alcohol and water bottles) with a presaturated cleaning wipe and allow them to dry before transporting them into the clean room [40].

- Prepare in Clean Room: After donning appropriate sterile gowning and gloves, place the supplies inside the hood. Wipes should be placed at least six inches inside the hood, as the outer six-inch edge of the work surface is considered a contaminated zone [40].

- Systematic Wiping Procedure [41]:

- Spray Surfaces: Immediately before working, spray all interior surfaces with a cleaning solution such as 70% ethanol or 70% isopropanol.

- Wipe Methodically: Using a lint-free wipe, start with the cleanest area and progress to the dirtiest to avoid spreading contamination.

- For a vertical laminar flow hood or Biosafety Cabinet: Clean the back wall first, then the side walls (moving side-to-side, from top to bottom), and always clean the floor panel last [41].

- For a horizontal laminar flow hood: Clean the ceiling panel first, then the back wall, side walls, and finally the work surface [41].

- Use a new cloth or tissue for each wall or whenever it looks dirty.

- Do not attempt to clean the HEPA filter itself; this requires professional certification [40].

- Final Documentation: The hood-cleaning process is an official procedure that must be documented on a checklist for review by regulatory and compliance organizations [40].

UV Sterilization

Many laminar flow hoods and biosafety cabinets are equipped with an ultraviolet (UV) light for supplemental sterilization. UV light inactivates microorganisms by altering their DNA [41]. Safety is paramount: UV light is harmful to human skin and eyes and should only be used to prepare the workspace when the hood is unoccupied. The light must always be turned off during use [41]. UV sterilization is not a substitute for manual cleaning, as dust and debris can shield microorganisms from the light.

Maintenance, Monitoring, and Contamination Control

Routine Maintenance Schedule

A laminar flow hood is a precision instrument that requires regular maintenance to function correctly. The following table outlines the critical maintenance tasks and their frequency.

Table: Laminar Flow Hood Maintenance Schedule

| Component | Maintenance Task | Frequency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Surface & Interior | Thorough cleaning with disinfectant | Before and after every use; every 30 mins during long sessions [40] [41]. | [40] [41] |

| Prefilter | Replacement | Every 30 days, or as per manufacturer's instructions [40]. | [40] |

| HEPA Filter | Integrity Recertification | Every 6 months, and anytime the hood is moved [40]. | [40] |

| UV Light | Check intensity and function | As per manufacturer's specifications. | - |

| Overall Hood | Contamination test (e.g., settle plates) | Periodically, or when contamination is suspected [41]. | [41] |

Experimental Protocol: Monitoring Contamination Levels

To quantitatively assess the cleanliness of your laminar flow hood, you can perform a simple contamination test using nutrient agar plates.

Objective: To determine the level of microbial contamination within the laminar flow hood workspace. Principle: Exposing growth media to the air inside the hood and then incubating it will allow any viable contaminants to form visible colonies [41].

Materials:

- Peptone agar plates or other suitable culture media (e.g., malt extract agar for fungi) [41].

- Incubator.

Methodology:

- Turn on the hood and allow it to run for at least 15-20 minutes to purge airborne particles.

- Perform the standard cleaning procedure as outlined in Section 3.2.

- Place several prepared, sterile agar plates in different locations within the hood, including the center, front, and sides.

- Remove the lids and expose the agar surfaces to the hood environment for time intervals relevant to your work (e.g., 30 minutes, 1 hour) [41].

- Replace the lids and collect the plates.

- Incubate the plates for 1–3 days at an appropriate temperature (e.g., 30-35°C for mesophilic bacteria and fungi) [41].

- Count the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) on each plate.

Interpretation: A clean environment is indicated by no colony growth after a 1-hour exposure [41]. The presence of colonies suggests contamination. If contamination is confirmed, thoroughly clean the hood, replace sterile materials, and if the problem persists, consider replacing the HEPA filter [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Aseptic Work

| Item | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 70% Isopropanol (IPA) | Primary surface disinfectant [40] [41]. | More effective than higher concentrations; water content is crucial for cell wall penetration. |

| 70% Ethanol | Alternative surface disinfectant [41]. | Effective and commonly used; can be sprayed as a fine mist to settle airborne particles [41]. |

| Chlorhexidine Gluconate | Surgical scrub for hand hygiene [40]. | Provides persistent antimicrobial activity on skin. |

| Sterile Water | Diluent and for removing water-soluble residues [40]. | Used after IPA to remove sticky residues that alcohol cannot dissolve [40]. |

| Lint-Free Wipes | Application of disinfectants without shedding fibers [40] [41]. | Critical for preventing introduction of particulate contaminants. |

| HEPA Filter | Air filtration to create an ISO Class 5 environment [36] [39]. | Traps 99.97% of particles ≥0.3 µm; requires regular recertification [40]. |

Meticulous workspace preparation, centered on the disciplined management of the laminar flow hood, is a non-negotiable aspect of successful aseptic technique. This involves selecting the correct Class II Biosafety Cabinet for cell culture, adhering to a strict and systematic cleaning protocol before, during, and after work, and implementing a routine schedule for maintenance and environmental monitoring. By integrating these practices into daily laboratory routines, researchers and drug development professionals can safeguard the integrity of their cultures, ensure the validity of their experimental data, and protect their own safety in the process.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and Personal Hygiene

This technical guide details the critical role of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and personal hygiene within the framework of aseptic techniques for microbial culture handling. It provides researchers and drug development professionals with the protocols and knowledge necessary to ensure sample integrity, personal safety, and experimental reproducibility.

Aseptic technique comprises a set of specialized procedures and routine practices designed to prevent contamination of samples and cultures throughout microbiological analysis [42]. These techniques are foundational to producing accurate and reliable research data, as contamination can lead to false or misleading results, ultimately compromising research findings and conclusions [42]. The principle is twofold: to protect the valuable microbial cultures from introduced contaminants and to shield the researcher and environment from potential exposure to pathogens.

The implementation of aseptic technique is critical in various settings, including research laboratories and pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities. In controlled environments like cleanrooms, where the concentration of airborne particles is meticulously regulated, contamination control is paramount [43]. Contaminants can be solid, liquid, gaseous, or microbial, and even minimal human presence is a significant source, as a human body can shed millions of skin particles per minute [43]. Therefore, a rigorous combination of personal hygiene and appropriate PPE is non-negotiable for maintaining the aseptic field.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): A Component of the Aseptic Barrier

PPE serves as a primary physical barrier between the researcher and the experimental materials. Its correct use minimizes the transfer of microorganisms, particulate matter, and chemical hazards, safeguarding both the personnel and the product.

The selection of PPE is determined by a risk assessment of the specific procedures and agents being handled. The following table summarizes the essential PPE components and their functions in a microbial research context.

Table 1: Personal Protective Equipment for Microbial Culture Handling

| PPE Category | Specific Types | Primary Function & Application | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Protection | Lab Coat, Gown, Coverall, Apron | Protects personal clothing and skin from stains, dyes, blood, dust, and contaminants; minimizes cross-contamination [44] [45]. | 65% cotton/35% polyester blend (semi-fire retardant) [44]; Tyvek for particulate and biological agent protection in cleanrooms [43]. |

| Hand Protection | Gloves (Nitrile, Latex, Vinyl) | Creates a barrier against contagious samples and hazardous chemicals; minimizes chemical exposure risks [44] [46]. | Disposable nitrile is minimum standard; checked for tears before use; not reused or disinfected [44]. |

| Eye & Face Protection | Safety Goggles, Face Shields | Protects from chemical liquid splashes and flying objects [44] [47]. | Goggles with baffled vents for splash protection; close-fitting to prevent lateral entry [47]. |

| Respiratory Protection | Surgical Mask, N95 Respirator | Surgical masks resist fluid and protect from large droplets; N95 respirators are tight-fitting and filter ≥95% of airborne particles for protection against small-particle aerosols [44] [48]. | N95 requires fit-testing for proper seal and optimal protection [48]. |

| Head & Footwear Protection | Hair/Beard Covers, Shoe Covers | Hair covers prevent loose strands from contaminating the environment [45]. Shoe covers prevent tracking dirt and microorganisms into clean areas [45]. | Well-fitting, comfortable, closed-toe shoes are a minimum requirement [44]. |

PPE for Specific Hazard Levels: Transmission-Based Precautions

When working with documented or suspected pathogens, standard PPE is augmented with transmission-based precautions. These are categorized based on the route of transmission and are directly applicable to handling specific microbial cultures in a research setting.

Table 2: Transmission-Based Precautions and Corresponding PPE

| Precaution Type | Implementation Context | Required PPE & Additional Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Contact Precautions | Known or suspected infections with epidemiologically important organisms (e.g., MRSA, VRE, C-diff), or draining wounds [48] [46]. | Gloves and Gown are required. Dedicated patient equipment is also used [48] [46]. |

| Droplet Precautions | Pathogens transmitted by large respiratory droplets from coughing, sneezing, or talking (e.g., influenza, pertussis) [48] [46]. | Mask and Goggles or a Face Shield are required [48] [46]. |

| Airborne Precautions | Pathogens transmitted by small respiratory droplets (e.g., tuberculosis, measles) [48] [46]. | Fit-tested N-95 respirator or PAPR is required. An airborne infection isolation room (single room with closed door) is also necessary [48] [46]. |

Foundational Protocols for Personal Hygiene

Personal hygiene, particularly hand hygiene, is the single most important practice for reducing the transmission of infectious agents in healthcare and research settings [48] [49].

Hand Hygiene Techniques and Protocols

Indications for Hand Hygiene (The Five Moments): Healthcare and research personnel should perform hand hygiene at these five key moments [48] [46]:

- Immediately before touching a patient or handling culture samples.

- Before performing an aseptic task or handling invasive devices.

- Before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site on a patient or sample.

- After touching a patient, culture samples, or their immediate environment.

- After contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without glove use).

Hand Hygiene Methods: There are two primary methods, each with specific indications and techniques.

Table 3: Hand Hygiene Protocol Comparison

| Parameter | Alcohol-Based Hand Rub | Handwashing with Soap and Water |

|---|---|---|

| Indications | Preferred method unless hands are visibly soiled [48] [46]. Routine decontamination after most patient or sample contact. | Hands are visibly soiled, contaminated with blood/body fluids, after restroom use, or potential exposure to spore-forming organisms (e.g., C. difficile, B. anthracis) [49] [46]. |