Fundamentals of Microbiological Method Verification: A Comprehensive Guide to Study Design for Reliable Lab Results

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for designing robust microbiological method verification studies.

Fundamentals of Microbiological Method Verification: A Comprehensive Guide to Study Design for Reliable Lab Results

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for designing robust microbiological method verification studies. Covering foundational concepts, practical methodology, troubleshooting strategies, and validation protocols, it translates regulatory requirements into actionable verification plans. Readers will learn to differentiate verification from validation, establish acceptance criteria, address common pitfalls, and implement defensible verification protocols compliant with CLIA, ISO 16140, and other relevant standards for both clinical and pharmaceutical quality control environments.

Core Principles and Regulatory Landscape of Microbiological Method Verification

In laboratory environments, particularly within pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and food safety, the demand for accurate and reliable testing is non-negotiable [1]. Two cornerstone processes—method validation and method verification—serve as critical pillars to ensure this reliability. While the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they represent distinct concepts with different applications, scopes, and regulatory implications. Understanding this distinction is not merely an academic exercise; it is a fundamental requirement for researchers and scientists designing microbiological studies, ensuring regulatory compliance, and maintaining data integrity. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of method verification versus validation, specifically framed within the context of microbiological method verification study design research.

Core Definitions and Conceptual Framework

What is Method Validation?

Method validation is a comprehensive, documented process that proves an analytical method is acceptable for its intended use [1]. It establishes the performance characteristics and limitations of a method and its domains of applicability [2]. This process is typically undertaken when a method is newly developed, significantly altered, or used for a new product or formulation [2].

In practice, validation involves rigorous testing and statistical evaluation to assess parameters such as accuracy, precision, specificity, detection limit, quantitation limit, linearity, and robustness [1]. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guideline Q2(R2) provides a recognized framework for the validation of analytical procedures, underscoring its global regulatory importance [3].

What is Method Verification?

Method verification, in contrast, is the process of confirming that a previously validated method performs as expected in a specific laboratory setting [1]. It is a one-time study meant to demonstrate that a test performs in line with previously established performance characteristics when used as intended by the manufacturer and under the actual conditions of the receiving laboratory [4] [2].

Essentially, while validation asks, "Does this method work for its intended purpose in general?", verification asks, "Can my laboratory successfully perform this already-validated method and achieve the established performance standards?" [5].

The table below synthesizes the key differences between these two critical processes.

Table 1: Core Differences Between Method Validation and Method Verification

| Comparison Factor | Method Validation | Method Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | To establish and document method performance characteristics for a novel or modified method [1] [2]. | To confirm a lab can reproduce the performance of a pre-validated method [1] [5]. |

| Typical Initiating Event | Development of a new method; significant method modification; use in a new matrix [4] [2]. | Adoption of an unmodified, FDA-cleared or compendial method (e.g., USP, EP) in a new lab [4] [2]. |

| Scope | Comprehensive assessment of all relevant performance parameters [1]. | Limited, targeted assessment of critical parameters to confirm performance in a specific context [1] [4]. |

| Regulatory Basis | ICH Q2(R2), USP <1225> [1] [3]. | CLIA regulations, USP <1226> [4] [2]. |

| Resource Intensity | High (time, cost, expertise) [1]. | Moderate, more efficient [1]. |

Method Verification in Detail: A Focus on Microbiological Study Design

For microbiological methods, verification studies are required by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) for non-waived systems before reporting patient results [4]. The following section outlines the key considerations and methodologies for designing a robust verification study.

Determining the Study Purpose and Type

The first step is unequivocally determining whether the activity is a verification or a validation. For a clinical microbiology lab, a verification is for unmodified FDA-approved or cleared tests, while a validation is necessary for laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) or modified FDA-approved methods [4]. Furthermore, the assay type—qualitative, quantitative, or semi-quantitative—must be defined as it directly influences the verification design and acceptance criteria [4].

Establishing the Verification Study Design and Protocols

For an unmodified FDA-approved test, laboratories are required to verify specific performance characteristics. The following table details the experimental protocols for verifying qualitative and semi-quantitative microbiological assays, as suggested by CLIA standards [4].

Table 2: Method Verification Protocols for Qualitative/Semi-Quantitative Microbiological Assays

| Performance Characteristic | Minimum Sample & Design Requirements | Recommended Samples & Sources | Calculation & Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Minimum of 20 clinically relevant isolates; combination of positive and negative samples [4]. | Standards/controls, reference materials, proficiency tests, de-identified clinical samples tested in parallel with a validated method [4]. | (Number of results in agreement / Total results) × 100. Must meet manufacturer's stated claims or lab director's determination [4]. |

| Precision | Minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative samples tested in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators (if not fully automated) [4]. | Controls or de-identified clinical samples [4]. | (Number of results in agreement / Total results) × 100. Must meet manufacturer's stated claims or lab director's determination [4]. |

| Reportable Range | Minimum of 3 known positive samples [4]. | Samples positive for the detected analyte; for semi-quantitative, use samples near the upper/lower manufacturer cutoffs [4]. | Verification that the laboratory can report results as defined (e.g., "Detected," "Not detected," Ct value cutoff) [4]. |

| Reference Range | Minimum of 20 isolates [4]. | De-identified clinical or reference samples representing the laboratory's typical patient population [4]. | Verification that the manufacturer's reference range is appropriate for the lab's patient population; re-definition may be necessary [4]. |

The Verification Plan

A formal, written verification plan is a cornerstone of a successful study. This document, which requires review and sign-off by the laboratory director, should include [4]:

- The type of verification and the purpose of the study.

- A detailed description of the test and its intended use.

- A comprehensive study design outlining the number and types of samples, quality controls, replicates, and performance characteristics to be evaluated with defined acceptance criteria.

- A list of all required materials, equipment, and resources.

- Safety considerations and a projected timeline for completion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Method Verification

The successful execution of a method verification study relies on a suite of critical reagents and materials. The selection of these components is vital to ensure the integrity and reproducibility of the study.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiological Verification

| Reagent/Material | Function in Verification Study | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Strains | Provide known, standardized microorganisms for spiking studies to assess accuracy, precision, and detection limits. | Using ATCC strains of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa to challenge a new sterility test method [4]. |

| Clinical Isolates | Offer real-world, clinically relevant microorganisms to ensure the method performs with diverse strains found in the patient population. | Using 20 de-identified patient isolates to verify a new MRSA detection assay [4]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Act as a gold standard for method comparison, providing a benchmark for accuracy and helping to establish the reportable range. | Using a certified quantitative microbial standard to verify the reportable range of an automated cell counter [5]. |

| Quality Controls (Positive/Negative) | Monitor the daily performance and consistency of the test system, ensuring it is functioning correctly throughout the verification process. | Including a positive control (a known weak positive) and a negative control in each run of a PCR-based verification study [4]. |

| Selective and Non-Selective Media | Support the growth and differentiation of target microorganisms; used in comparative studies for accuracy assessment. | Using Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) for the recovery of a wide range of microorganisms in a growth-based rapid method [6]. |

The Regulatory and Lifecycle Context

The Evolving Regulatory Landscape

Regulatory guidance clearly demarcates the requirements for validation and verification. Validation is governed by guidelines such as ICH Q2(R2) and USP <1225>, while verification is addressed in documents like USP <1226> and CLIA regulations [1] [4] [2]. Furthermore, the regulatory environment is evolving to accommodate modern techniques. The recent publication of USP <73> on ATP-bioluminescence for short shelf-life products, effective August 2025, lowers the barrier for using these rapid microbiological methods (RMMs) by no longer requiring alternative method validation, acknowledging their reliability [6].

The Method Lifecycle and "Fitness-for-Purpose"

Method validation and verification are part of a broader method lifecycle. A newer, crucial concept is "Fitness-for-Purpose"—a demonstration that a method delivers expected results in a previously unvalidated matrix [5]. This is particularly relevant when applying a validated method to a new food matrix or sample type. The decision to perform a full validation, a verification, or a "fitness-for-purpose" study depends on the degree of change and the associated public health or detection risk [5].

The distinction between method validation and method verification is a fundamental concept that underpins reliable laboratory testing in drug development and clinical research. Validation is a comprehensive process to establish a method's performance, while verification is a targeted confirmation that a pre-validated method works in a specific lab's hands. For microbiological methods, a well-designed verification study—rooted in a solid plan, appropriate sample sizes, and clear acceptance criteria—is not just a regulatory hurdle but a critical component of quality assurance. As the field advances with new rapid microbiological methods and evolving regulatory guidance, a deep understanding of these principles ensures that researchers and scientists can navigate the complexities of method qualification, ultimately guaranteeing the safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical products and the accuracy of clinical diagnostics.

For researchers and scientists designing microbiological method verification studies, navigating the intersecting requirements of major regulatory frameworks is fundamental to ensuring data integrity, patient safety, and regulatory compliance. The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) in the U.S., the international quality standard ISO 15189 for medical laboratories, and the European Union's In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR) collectively shape the standards for laboratory testing. While CLIA provides a mandatory, compliance-focused structure for U.S. laboratories, ISO 15189 is a voluntary, international standard emphasizing continual improvement and risk management. The IVDR presents a product-centric regulatory framework for manufacturers placing devices on the European market. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these frameworks, with a specific focus on their implications for the design and execution of microbiological method verification studies.

CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments)

CLIA is a U.S. federal regulatory standard established to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and timeliness of patient test results regardless of where a test is performed [7]. Its primary focus is on analytical testing phases. Compliance with CLIA regulations is mandatory for all clinical laboratories in the United States that report patient-specific results for health assessment [7] [8]. Laboratories are subject to routine inspections by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) or CMS-approved accrediting organizations [7].

ISO 15189 (Medical laboratories — Requirements for quality and competence)

ISO 15189 is an international standard that specifies requirements for quality and competence in medical laboratories [8]. Its core objective is to promote patient welfare and satisfaction through confidence in the quality of laboratory results [9]. A major focus of the updated 2022 version is on risk management, making patient safety central to all laboratory processes [9]. Unlike CLIA, ISO 15189 accreditation is voluntary and serves as a demonstration of a laboratory's commitment to a high level of quality and continuous improvement [7].

IVDR (In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation)

The IVDR (EU) 2017/746 is the European Union's regulatory framework for in vitro diagnostic medical devices [10]. It is a product-centric regulation that applies to manufacturers placing IVD devices on the EU market. A cornerstone of the IVDR is a new, stricter risk-based classification system (Class A-D), with most devices now requiring a conformity assessment by a Notified Body [11]. The regulation emphasizes robust clinical evidence, performance evaluation, and stringent post-market surveillance [11]. Key transition periods for legacy devices are in effect from 2025 to 2027 [10] [11].

Table: High-Level Comparison of CLIA, ISO 15189, and IVDR

| Feature | CLIA | ISO 15189 | IVDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | United States | International | European Union |

| Nature | Mandatory regulation | Voluntary accreditation | Mandatory product regulation |

| Primary Focus | Analytical phase quality; regulatory compliance | Total testing process; continuous improvement; patient safety | Device safety, performance, and lifecycle monitoring |

| Governing Body | Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) | International Organization for Standardization (ISO) | European Commission |

| Applicability | Clinical laboratories | Medical laboratories | Manufacturers of in vitro diagnostics |

Detailed Requirements for Method Verification

Method verification is the process of confirming that a validated test performs as expected in a laboratory's own environment before reporting patient results [4]. For non-waived, FDA-cleared tests, CLIA requires verification of specific performance characteristics [4].

CLIA Requirements for Verification of Microbiological Methods

For qualitative and semi-quantitative microbiological assays (e.g., PCR, antigen tests), CLIA requires verification of several key performance characteristics [4]. The following protocols outline standard methodologies.

Table: CLIA Method Verification Protocol for Qualitative/Semi-Quantitative Assays

| Performance Characteristic | Recommended Protocol (Microbiology) | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Test a minimum of 20 clinically relevant isolates (positive and negative). Use standards, controls, proficiency samples, or clinical specimens previously tested with a validated method [4]. | Percentage of agreement = (Number of agreements / Total results) × 100. Should meet manufacturer's stated claims or criteria set by the laboratory director [4]. |

| Precision | Test a minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative samples in triplicate over 5 days by 2 different operators. Use controls or de-identified clinical samples [4]. | Percentage of agreement = (Number of agreements / Total results) × 100. Should meet manufacturer's stated claims or director-defined criteria [4]. |

| Reportable Range | Verify using a minimum of 3 samples. For qualitative assays, use known positive samples. For semi-quantitative, use samples near the cutoff values [4]. | The laboratory confirms that it can accurately report results as defined (e.g., "Detected," "Not detected," or with a specific Ct value cutoff) [4]. |

| Reference Range | Verify using a minimum of 20 isolates. Use de-identified clinical samples or reference materials that represent the laboratory's patient population [4]. | The laboratory confirms the manufacturer's reference range is appropriate for its patient population, or re-defines it if necessary [4]. |

ISO 15189 and IVDR Considerations for Verification

ISO 15189 emphasizes the verification and validation of examination procedures to ensure they are suitable for their intended use [8]. It mandates that laboratories must "verify the ability to achieve the required performance" and that examination procedures must be "appropriate for the intended use" [8]. This aligns with CLIA but is embedded within a broader quality management system that requires documented procedures, personnel competence, and risk management across the entire testing process (pre-examination, examination, and post-examination) [8].

The IVDR imposes requirements on the manufacturer, not the clinical laboratory directly. However, laboratories using IVDR-compliant devices must be aware that the manufacturer's provided performance claims (e.g., sensitivity, specificity) are backed by a stringent performance evaluation and clinical evidence dossier assessed by a Notified Body [11]. The laboratory's verification study often uses this manufacturer data as the benchmark for acceptance criteria.

Comparative Analysis of Quality Control and Personnel Requirements

Quality Control (QC) and Proficiency Testing (PT)

A 2025 global survey of QC practices highlights practical differences in how accredited laboratories implement QC. CLIA labs are overwhelmingly once-a-day QC users, aligning with the CLIA minimum requirement, while ISO 15189 labs show more variation in frequency, with a more balanced distribution across once, twice, or three times per day [12]. The same survey found that ISO labs are more likely to use multi-rule "Westgard Rules" on all tests compared to CLIA labs [12].

CLIA mandates successful participation in a CMS-approved proficiency testing (PT) program for regulated analytes [13]. New, stricter PT acceptance criteria were fully implemented in 2025 [13]. For example, the allowable total error for microbiology-based glucose is now ± 8% or ± 6 mg/dL (whichever is greater), tightened from the previous ± 10% [13]. ISO 15189 also requires participation in inter-laboratory comparisons, such as PT, but as part of a broader external quality assessment scheme used for continual improvement.

Personnel Qualifications

CLIA regulations specify detailed personnel qualifications for different roles (director, supervisor, testing personnel) and based on test complexity (moderate or high). Recent updates effective in 2025 have refined these requirements, including changes to permitted degrees and the addition of continuing education requirements for high-complexity lab directors [14]. Grandfathering clauses protect currently employed personnel if their employment is continuous [14].

ISO 15189, under its "Resource Requirements" (Clause 6), mandates that personnel be competent and have the appropriate education, training, experience, and skills, but does not prescribe specific degree or hour requirements like CLIA [8]. The laboratory must define the necessary competence for each role and provide evidence that personnel meet these requirements [8].

Table: Comparison of Key Laboratory Processes

| Process | CLIA | ISO 15189:2022 |

|---|---|---|

| QC Frequency | Primarily once per day (minimum requirement) [12]. | More varied; can be once, twice, or three times per day based on risk [12]. |

| QC Rules | Less frequent use of multi-rule Westgard Rules [12]. | More frequent use of multi-rule Westgard Rules on all tests [12]. |

| Proficiency Testing (PT) | Mandatory, with specific graded analytes and 2025-updated acceptance criteria [13]. | Required as part of external quality assessment (EQA), used for performance monitoring and improvement. |

| Personnel | Specific, regulated degree and experience requirements for each role [14]. | Competency-based requirements defined by the laboratory [8]. |

| Risk Management | Implied in quality assessment but not explicitly mandated as a formal process. | A major focus; requires proactive risk management across all processes to benefit patient safety [9]. |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following reagents and materials are critical for executing a compliant microbiological method verification study.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Method Verification

| Reagent/Material | Function in Verification |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides a metrologically traceable standard for verifying accuracy and reportable range. |

| Commercial Quality Controls (Assayed/Lyophilized) | Used for precision (repeatability and reproducibility) studies and ongoing quality control. |

| Characterized Clinical Isolates | Essential for accuracy studies; provides samples with known identity/characteristics for comparison. |

| Proficiency Testing (PT) Samples | Used as an external benchmark for verifying assay accuracy and performance. |

| Storage and Stability Solutions | Ensures the integrity of reagents and samples throughout the verification timeline. |

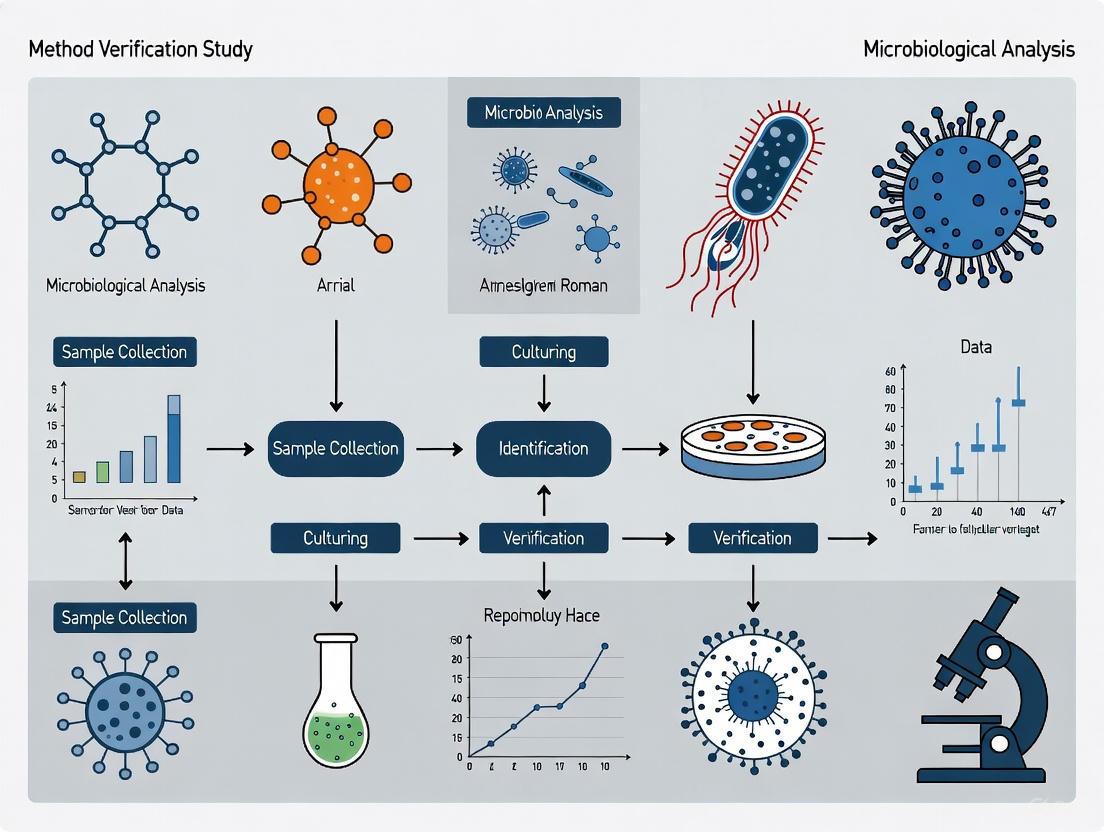

Method Verification Workflow

The following diagram maps the logical workflow for planning and executing a method verification study, integrating considerations from CLIA, ISO 15189, and manufacturer's (IVDR) claims.

Method Verification Workflow Diagram

The regulatory frameworks of CLIA, ISO 15189, and IVDR, while distinct in their scope and application, are not mutually exclusive. A modern clinical microbiology laboratory must often operate within the boundaries of multiple standards. CLIA provides the foundational, compliance-based floor for U.S. operations. ISO 15189 offers a ceiling for achieving excellence through a holistic, risk-based quality management system. The IVDR ensures that the diagnostic devices themselves are safe and effective. A robust microbiological method verification study is not merely a regulatory checkbox but a critical scientific undertaking. It synthesizes the manufacturer's (IVDR) performance claims with the laboratory's specific environment and patient population, following structured protocols (CLIA) within a system dedicated to continuous quality improvement and patient safety (ISO 15189). Understanding the requirements and synergies between these frameworks is fundamental to designing a verification study that is both scientifically sound and regulatorily compliant.

In the rigorous world of pharmaceutical, clinical, and food safety microbiology, the concepts of method validation and method verification are foundational to ensuring the reliability of laboratory data. Although these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they represent distinct, critical processes within the method lifecycle. Method validation is the process of establishing, through laboratory studies, that the performance characteristics of a method meet the requirements for its intended analytical applications [15]. In contrast, method verification is "the ability to verify that a method can perform reliably and precisely for its intended purpose" within a specific laboratory setting [15]. Essentially, verification demonstrates that a laboratory can successfully execute a method that has already been validated elsewhere [5].

Understanding when verification is required—as opposed to a full validation or a simpler qualification—is a fundamental compliance and scientific decision. This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a structured framework for determining verification necessity, ensuring both regulatory compliance and data integrity.

The Regulatory and Standards Framework

Globally, regulatory authorities and standards organizations provide clear, albeit sometimes differing, expectations for method verification. A summary of key guidance across major sectors is provided in the table below.

Table 1: Regulatory and Standards Framework for Method Verification

| Authority/Standard | Sector | Key Guidance/Document | Verification Requirement Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDA, EMA, ICH | Pharmaceutical | ICH Q2(R2), USP <1226>, USP <1225> | Verification required for compendial (e.g., USP, EP) methods or previously validated methods transferred to a new laboratory [15] [16]. |

| CLIA | Clinical Microbiology | 42 CFR 493.1253 | Verification is mandated for unmodified, FDA-cleared/approved tests before reporting patient results [4]. |

| ISO | Food & Feed Testing | ISO 16140 Series (Parts 1, 3) | Two-stage verification: "implementation verification" and "(food) item verification" to demonstrate laboratory competency and method suitability for specific items [17]. |

| AOAC, FDA | Food Safety | AOAC Guidelines, FDA 21 CFR 211 | Each laboratory must perform verification to show it can correctly execute a validated method with its specific operators and environment [5]. |

The core principle unifying these regulations is that the burden of proof is on the testing laboratory. Even when using a method perfectly validated by a pharmacopeia or a kit manufacturer, a laboratory must still verify that the method performs as expected in its own hands, with its specific equipment, reagents, and personnel [15] [5].

When is Verification Required? A Decision Framework

The necessity for verification is triggered by specific scenarios in the laboratory. The following decision pathway provides a visual guide to determining when verification is the required course of action.

Diagram 1: Method Verification Decision Pathway

The decision framework outlines three primary scenarios mandating verification. The specific protocols and experimental designs for each scenario, however, differ based on the method type and regulatory context.

Verification of Compendial Methods

In pharmaceutical quality control (QC) microbiology, many standard methods like sterility testing (USP <71>) and microbial enumeration (USP <61>) are validated by the pharmacopeia. The laboratory's task is not to re-validate these methods but to perform verification that the method is suitable for the specific product (sample matrix) and the laboratory setting [15]. The core objective is to demonstrate that the sample itself does not interfere with the method's ability to recover microorganisms.

Verification of Commercial Kits and FDA-Cleared Tests

When implementing an unmodified, commercially available test kit or an FDA-cleared/approved method, laboratories are required to perform a verification study [4] [16]. This process verifies that the laboratory can achieve the performance characteristics (e.g., accuracy, precision) claimed by the manufacturer. For Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) compliance, this is a one-time study for non-waived systems before reporting patient results [4].

Method Transfer Between Laboratories

When a validated method is transferred from one laboratory to another (e.g., from an R&D center to a QC lab, or to a contract testing organization), the receiving laboratory must perform verification. This demonstrates that the method can be executed successfully in the new environment, producing results equivalent to those generated by the originating laboratory.

Distinguishing Verification from Validation and Qualification

A critical skill for scientists is to discern when verification is sufficient versus when a more extensive validation is needed. The table below clarifies the distinctions and appropriate applications for each.

Table 2: Comparison of Validation, Verification, and Qualification

| Aspect | Method Validation | Method Verification | Method Qualification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Establishing performance characteristics for a new method's intended use [15]. | Demonstrating a lab can perform a pre-validated method correctly [15] [5]. | A phase-appropriate approach for early development where full validation is not yet required [16]. |

| Scope | Broad, to prove the method itself is fit-for-purpose. | Narrow, to prove laboratory proficiency with the method. | Flexible and risk-based, covering critical parameters for the development stage. |

| When Used | - Novel method development- Modern/alternative method implementation [15]- Significant method modification. | - Compendial methods [15]- Unmodified commercial kits [16]- Method transfer. | - Early-stage drug development (e.g., Phase I) [16]- Methods for processes not yet locked. |

| Key Parameters | Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, LOD, LOQ, Linearity, Range, Robustness [15]. | Accuracy, Precision, Reportable Range, Reference Range (as per CLIA) [4]. | Risk-based selection of critical parameters (e.g., specificity, accuracy for safety-related tests) [16]. |

A key differentiator is that verification is for established methods, while validation is for novel or significantly changed methods. Furthermore, in early-stage drug development where processes are fluid, a full validation may be premature. In these cases, a phase-appropriate "qualification" is often the recommended strategy, reserving the term "validation" for later-stage (Phase III and commercial) methods [16].

Experimental Protocols for Core Verification Activities

Protocol for Verification of a Qualitative Compendial Method

This protocol is suited for methods like USP <61> for non-sterile products.

- 1. Purpose: To verify that a compendial qualitative method (e.g., test for specified microorganisms) is suitable for use with a specific product matrix in the user's laboratory.

- 2. Experimental Design:

- Sample Preparation: Use a minimum of 20 test samples. These can be artificially contaminated with low levels (typically 10-100 CFU) of appropriate challenge organisms specified in the compendial chapter [4] [15].

- Control Strains: Use ATCC or equivalent reference strains.

- Testing: Execute the compendial method exactly as written on the contaminated samples and appropriate negative controls.

- 3. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the Accuracy as (Number of correct positive identifications / Total number of challenged samples) x 100 [4].

- The acceptance criterion is typically successful detection and identification of the challenge organism in all contaminated samples, with negative controls showing no growth.

- 4. Documentation: The verification report must include the compendial method reference, details of samples and challenge organisms, raw data, calculations, and a statement of acceptance.

Protocol for Verification of a Quantitative Method (CLIA Framework)

This protocol is based on CLIA requirements for an unmodified, FDA-cleared quantitative test.

- 1. Purpose: To verify the performance of an unmodified quantitative method in the user's laboratory.

- 2. Experimental Design:

- Accuracy: Compare results from the new method against a reference method or known standard for a minimum of 20 samples [4].

- Precision:

- Within-run: Test a minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative samples in triplicate in a single run.

- Between-run & Operator: Test the same samples over 5 days by 2 different operators [4].

- 3. Data Analysis:

- Accuracy: Calculate the percentage agreement or bias compared to the reference value.

- Precision: Calculate the standard deviation and coefficient of variation (%CV) for the replicate measurements. The results should meet the manufacturer's stated claims or laboratory-defined criteria.

- 4. Additional CLIA Requirements: The laboratory must also verify the Reportable Range (upper and lower limits) using at least 3 samples and the Reference Range (normal values) using a minimum of 20 samples from the laboratory's patient population [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful verification studies rely on high-quality, traceable materials. The following table details essential items for a microbiological verification toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Verification Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Verification | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Strains (e.g., ATCC, NCTC) | Served as challenge organisms for accuracy, specificity, and limit of detection studies. | Purity, viability, and proper lineage documentation are critical. Must be appropriate for the method and sample matrix. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Provide a "conventional true value" for quantifying accuracy and calibrating measurements. | Source and certification documentation must be available. |

| Inhibitory/Interfering Substances | Used in robustness testing to evaluate the method's resilience to slight variations. | Examples include varying pH, salinity, or specific components known to be in the sample matrix. |

| Quality Control Strains | Used for ongoing monitoring of method performance pre- and post-verification. | Should be different from the reference strains used in the initial verification. |

| Standardized Culture Media | Supports the growth and recovery of challenge organisms. | Must be qualified and prepared according to compendial or manufacturer specifications. |

Determining the necessity for verification is a fundamental, non-negotiable step in the implementation of any microbiological method within a regulated environment. The requirement is clearly triggered in three core scenarios: when adopting a compendial method, when implementing an unmodified commercial kit or FDA-cleared test, and when transferring a validated method to a new laboratory. By adhering to the structured decision framework and experimental protocols outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure their laboratories generate reliable, defensible data, thereby upholding the highest standards of product quality and patient safety. A disciplined approach to verification is not merely a regulatory hurdle; it is a cornerstone of scientific rigor in applied microbiology.

In clinical and microbiological laboratories, the classification of test methods into qualitative, quantitative, and semi-quantitative categories is fundamental to research design, method verification, and data interpretation. These categories correspond to established scales of measurement in metrology, each with distinct statistical properties and applications [18].

The ordinal, difference, and ratio scales deal with properties that can be measured and apply to quantitative methods, which report quantitative results, typically concentrations. The nominal scale applies to qualitative methods, which report categorical results without numerical values [18]. Semi-quantitative assays occupy a unique position, providing results on an ordinal scale where values can be ranked but lack the precise numerical relationships of true quantitative measurements [18] [19].

Understanding these distinctions is particularly crucial for method verification study design in microbiological research, where the choice of assay type directly impacts validation protocols, statistical analysis methods, and the interpretation of results in drug development contexts.

Defining the Core Assay Categories

Qualitative Assays

Qualitative assays determine the presence or absence of an analyte and provide a binary "yes/no" result [20] [4]. These tests examine nominal properties where only equality matters, and results cannot be ordered or ranked [18]. The output is reported using descriptive terms such as "positive/negative," "reactive/non-reactive," or "detected/not detected" [20] [4].

Examples in Practice:

- Diagnostic tests for pathogens (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 via qualitative RT-PCR) [20]

- Pregnancy tests detecting human chorionic gonadotrophin [20]

- Presence of specific genetic markers [4]

Quantitative Assays

Quantitative assays report precise numerical concentrations of an analyte, employing calibration curves with multiple points to calculate exact values for unknown specimens [20]. These methods utilize the ratio scale, characterized by equally sized units, a natural zero point, and constant ratio relationships between quantity values [18].

Key Characteristics:

- Results expressed in standardized units (e.g., BAU/mL, IU/mL) [20]

- Require comparison to international standards for harmonization [20]

- Enable longitudinal monitoring and precise threshold determination [20]

Semi-Quantitative Assays

Semi-quantitative assays measure approximate concentrations and report results on an ordinal scale with multiple arbitrary steps or categories without standard measurement units [20] [19]. They provide more information than qualitative tests but less precision than fully quantitative methods [18].

Distinguishing Features:

- Results are ordinal and can be ranked (e.g., "small," "moderate," "large") but lack precisely defined intervals between categories [18]

- May use numerical values to determine cutoffs but report qualitative results [4]

- Often employ a single calibrator or limited calibration curve to establish cutoff values [20]

- Recognized as having "less-than-optimal quality indicators for trueness, precision, and detectability" compared to quantitative methods [18]

Common Applications:

- Urine test strips with multiple result categories [19]

- Serologic antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2 that estimate levels without precise quantification [20]

- Screening tests for drugs of abuse with graded results [19]

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Assay Categories

| Characteristic | Qualitative | Semi-Quantitative | Quantitative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scale Type | Nominal | Ordinal | Ratio |

| Result Format | Binary (e.g., Positive/Negative) | Multiple ordered categories | Precise numerical value with units |

| Statistical Analysis | Contingency tables, Bayesian statistics | Ordinal scale statistics | Parametric statistics |

| Calibration | Single cutoff point | Limited calibration points | Multi-point calibration curve |

| Uncertainty Communication | Probability of classification error | Estimated concentration ranges | Measurement uncertainty with confidence intervals |

| Example Methods | Pregnancy tests, pathogen presence | Urine test strips, graded serology | Therapeutic drug monitoring, antibody quantification |

Method Verification and Validation Frameworks

Distinguishing Verification from Validation

In laboratory medicine, verification confirms that a previously validated method performs as expected in a user's laboratory, while validation establishes that an assay works as intended for its specific application [4]. Verification is required for unmodified FDA-cleared tests, whereas validation is necessary for laboratory-developed tests or modified FDA-approved methods [4].

The ISO 16140 series provides standardized protocols for method validation in microbiology, with specific parts addressing different validation scenarios [17]:

- Part 2: Validation of alternative (proprietary) methods against a reference method

- Part 3: Verification of reference methods in a single laboratory

- Part 4: Protocol for method validation in a single laboratory

- Part 5: Factorial interlaboratory validation for non-proprietary methods

- Part 6 & 7: Validation of confirmation and identification procedures [17]

Verification Criteria for Different Assay Types

For qualitative and semi-quantitative assays, verification requires specific approaches that differ from quantitative methods [4]:

Accuracy Verification:

- Minimum of 20 clinically relevant isolates recommended

- Combination of positive and negative samples for qualitative assays

- Range of samples with high to low values for semi-quantitative assays

- Calculation: (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100 [4]

Precision Verification:

- Minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative samples tested in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators

- For semi-quantitative assays: samples spanning high to low values

- Fully automated systems may not require user variance testing [4]

Reportable Range Verification:

- Minimum of 3 known positive samples for qualitative assays

- Samples near upper and lower cutoff values for semi-quantitative assays

- Verification that results fall within the manufacturer's established reportable range [4]

Experimental Design and Statistical Approaches

Statistical Methods for Qualitative and Semi-Quantitative Data

The evaluation of qualitative and semi-quantitative assays requires specialized statistical approaches distinct from those used for quantitative data. Standard method validation parameters for quantitative assays do not apply to these formats [19].

Recommended Statistical Tools:

- Contingency tables for comparing method outcomes

- Bayesian statistics for probability-based assessments

- Statistical hypothesis testing for inter-rater agreement [19]

- Measures of accordance and concordance for interlaboratory studies of qualitative methods [19]

For novel digital measures and complex data structures, advanced statistical methods including confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), multiple linear regression, and correlation analyses have shown utility in establishing relationships between measures, particularly when traditional reference standards are unavailable [21].

Study Design Considerations

Key factors in validation study design significantly impact the ability to detect meaningful relationships between measures:

Temporal Coherence: Alignment of data collection periods between compared methods [21]

Construct Coherence: Similarity between the theoretical constructs being assessed by different measures [21]

Data Completeness: Implementation of strategies to maximize complete data capture across all measures [21]

Studies with strong temporal and construct coherence demonstrate stronger correlations and more reliable validation outcomes [21].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Method Verification Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Verification Studies | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control Organisms | Well-characterized microorganisms with defined profiles to validate testing methodologies and monitor instrument, operator, and reagent quality [22]. | Pharmaceutical, food, and clinical testing laboratories |

| International Standards | Reference materials that ensure results correspond to specific numerical values and harmonize results across different laboratories [20]. | Quantitative serologic assays (e.g., WHO International Standard for anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin) |

| Calibrators | Materials with known analyte concentrations used to establish calibration curves for quantitative and semi-quantitative assays [20]. | All quantitative and semi-quantitative method validation |

| Proficiency Test Materials | Samples of known composition but unknown to analysts used to validate laboratory competency and method performance [22]. | Ongoing quality assurance for all method types |

| Reference Materials | Certified materials used for method validation, equipment calibration, and quality control [22]. | Implementation of new methods and routine quality monitoring |

The precise categorization of assay methods into qualitative, quantitative, and semi-quantitative formats provides the foundation for appropriate method verification study design in microbiological research and drug development. Understanding the fundamental measurement scales underlying these categories enables researchers to select appropriate statistical methods, design rigorous validation protocols, and correctly interpret results within the framework of regulatory requirements.

As novel technologies continue to emerge, particularly in digital health and complex biomarker detection, the principles of method validation and verification remain essential for ensuring analytical reliability and clinical utility across all assay formats. The standardized approaches outlined in international standards such as the ISO 16140 series provide critical guidance for maintaining methodological rigor while accommodating technological innovation in pharmaceutical development and clinical diagnostics.

Within the framework of microbiological method verification study design research, a Verification Plan serves as the foundational document that ensures a laboratory can successfully perform a validated method before implementing it for routine testing [17]. This is distinct from method validation, which is the initial process of establishing that an assay works as intended, often for non-FDA cleared tests [4]. In contrast, verification is a one-time study for unmodified FDA-approved or cleared tests, meant to demonstrate that the test performs in line with previously established performance characteristics when used as intended by the manufacturer [4]. A meticulously crafted and approved plan is critical for regulatory compliance, data integrity, and ensuring the reliability of results reported from the clinical or food testing laboratory.

Core Components of a Verification Plan

A comprehensive verification plan acts as a detailed roadmap for the entire study. It must be clear, unambiguous, and provide sufficient detail to enable consistent execution. The essential components are:

- Type of Verification and Purpose of Study: The plan must clearly state whether the activity is a verification or a validation, as the requirements differ significantly [4]. It should also describe the purpose of the test and a brief method description.

- Details of Study Design: This is the core of the plan, specifying the performance characteristics that will be evaluated and the rigorous protocols for doing so. According to CLIA standards for non-waived systems, this must include Accuracy, Precision, Reportable Range, and Reference Range [4]. The plan must detail the number and type(s) of samples, the type of quality assurance and quality controls that will be used, the number of replicates (including how many days and how many analysts), and, crucially, the pre-defined acceptance criteria for each characteristic [4].

- Materials, Equipment, and Resources: A complete list of all materials, equipment, reagents, and any other resources needed to execute the study must be included.

- Safety Considerations: The plan should address any specific safety protocols for handling microbiological specimens or other hazardous materials.

- Expected Timeline for Completion: A projected timeline with key milestones helps in tracking the progress of the verification study.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key decision points in developing a microbiological method verification plan:

Quantitative Requirements: Structuring the Verification Study

The verification study's design must be backed by empirical evidence and adhere to statistically sound principles. The tables below summarize the key quantitative requirements for verifying qualitative and semi-quantitative microbiological assays, based on established guidelines [4].

Table 1: Sample Size and Composition Requirements for Verification Studies

| Performance Characteristic | Minimum Sample Number | Sample Type & Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 20 isolates [4] | A combination of positive and negative samples for qualitative assays; a range of samples with high to low values for semi-quantitative assays [4]. |

| Precision | 2 positive and 2 negative samples [4] | Tested in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators. If the system is fully automated, user variance testing may not be needed [4]. |

| Reportable Range | 3 samples [4] | For qualitative assays, use known positive samples; for semi-quantitative, use samples near the upper and lower manufacturer cutoffs [4]. |

| Reference Range | 20 isolates [4] | Use de-identified clinical or reference samples representative of the laboratory's patient population [4]. |

Table 2: Experimental Protocols and Acceptance Criteria

| Performance Characteristic | Experimental Protocol | Calculation & Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Test the minimum number of samples, comparing results between the new method and a comparative method [4]. | (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100. The percentage must meet the manufacturer's stated claims or criteria set by the Laboratory Director [4]. |

| Precision | Test the required samples in triplicate over multiple days with multiple operators, as specified [4]. | (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100. The percentage must meet the manufacturer's stated claims or director-defined criteria [4]. |

| Reportable Range | Verify the upper and lower limits by testing samples that fall within the reportable range [4]. | The laboratory establishes what constitutes a reportable result (e.g., "Detected," "Not detected," Ct value cutoff), verified by testing [4]. |

| Reference Range | Verify the normal result for the tested patient population using the required number of samples [4]. | The expected result for a typical sample is verified. If the manufacturer's range doesn't represent the lab's population, the range may need re-defining [4]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Executing a verification plan requires specific, high-quality materials. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions in the verification process.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Microbiological Method Verification

| Item | Function in Verification |

|---|---|

| Clinical Isolates & Reference Strains | Well-characterized microbial strains used as positive controls, for accuracy testing, and for challenging the method with relevant organisms [4]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Materials | Commercially available controls or de-identified clinical samples used to monitor the precision and ongoing performance of the method during the verification study [4]. |

| Selective and Non-Selective Agar Media | Various growth media used for the recovery of microorganisms, essential for verifying that the method performs as expected across different culture conditions [17]. |

| Molecular Detection Reagents | Kits containing primers, probes, and enzymes for PCR-based verification studies, used to confirm the identity of isolates and verify molecular assay performance [23]. |

| Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) Panels | For verifying AST methods, these panels contain predefined antibiotics at specific concentrations to establish accurate and precise minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) results [4]. |

Director Approval: The Final Verification Gateway

The laboratory director's approval is not a mere formality but a critical regulatory and quality gate. Before starting the study, the written verification plan must be reviewed and signed off by the lab director [4]. This endorsement signifies that the director, who bears ultimate responsibility for the quality and integrity of the laboratory's results, has verified that:

- The plan is scientifically sound and aligns with regulatory requirements (e.g., CLIA) [4] and standards (e.g., ISO 16140 series for microbiological methods) [17].

- The study design is robust, with appropriate sample sizes, acceptance criteria, and methodologies to demonstrate the method is under control.

- The laboratory has the requisite resources, including trained personnel and equipment, to successfully complete the verification.

The director's approval transforms the verification plan from a proposal into an authorized protocol, enabling the laboratory to proceed with the testing phase and ultimately implement a reliable and compliant testing method.

Designing and Executing a Robust Verification Study Protocol

Within the rigorous fields of pharmaceutical development and clinical diagnostics, the reliability of microbiological testing is paramount. Establishing the performance characteristics of a method is a fundamental requirement to ensure that test results are accurate, reproducible, and fit for their intended purpose. This process is a critical component of method verification and validation, which together form the bedrock of quality assurance in regulated laboratories. Method verification demonstrates that a previously validated method performs as expected within a user's laboratory, while method validation provides evidence that a new method is fit for its intended purpose through a rigorous, defined process [17] [24].

This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the four core performance characteristics—Accuracy, Precision, Reportable Range, and Reference Range—that must be established for microbiological methods. Framed within the broader context of microbiological method verification study design, this whitepaper delivers detailed experimental protocols and data analysis frameworks tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core Performance Characteristics: Definitions and Experimental Protocols

The following characteristics represent the foundation for assessing a method's performance. The specific experimental approach varies depending on whether the method is qualitative (e.g., presence/absence of a microorganism) or quantitative (e.g., microbial enumeration).

Accuracy

Accuracy refers to the closeness of agreement between a test result and an accepted reference value, or the proportion of correct results identified by a new method compared to a reference method. It is a measure of correctness [24] [25].

Experimental Protocols:

- For Quantitative Methods (e.g., Bioburden Enumeration): Accuracy is determined by assessing the recovery of known quantities of a microorganism from a sample matrix. A common approach is to inoculate a sterile product or a placebo with a low-level challenge (e.g., <100 Colony Forming Units or CFU) of a specified microorganism and quantify the recovery using the new method. The percentage recovery is calculated as (Result from New Method / Expected Result) × 100. Acceptance criteria often specify a recovery range of 50% to 200% for microbiological methods, reflecting the inherent variability in microbial distribution and recovery [25].

- For Qualitative Methods (e.g., Sterility Testing, Pathogen Detection): Accuracy is evaluated by testing a panel of samples with known status (positive or negative). The panel should include a minimum of 20 clinically relevant isolates or samples, comprising both positive and negative targets [24]. The accuracy is calculated as the percentage of correct results: (Number of Correct Results / Total Number of Results) × 100 [24] [25].

Table 1: Experimental Design for Assessing Accuracy

| Method Type | Sample Number & Type | Challenge Microorganism | Key Calculations | Common Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Minimum 3 replicates per organism/matrix | <100 CFU of specified strains | % Recovery = (Result from New Method / Expected Result) × 100 | Recovery between 50% and 200% [25] |

| Qualitative | Minimum 20 samples (positive & negative) | Relevant to method's purpose (e.g., E. coli for a coliform test) | % Accuracy = (Number of Correct Results / Total Results) × 100 | Meets manufacturer's claims or a predetermined percentage (e.g., ≥95%) [24] |

Precision

Precision describes the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under prescribed conditions. It is a measure of reproducibility and is typically subdivided into repeatability and intermediate precision [24] [25].

Experimental Protocols:

- Repeatability (Within-test variation): This assesses the variation when the test is performed repeatedly in a short period by the same technician using the same equipment and reagents. A minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative samples (or samples with high and low values for semi-quantitative assays) are tested in triplicate [24]. Results are expressed as standard deviation (SD) or coefficient of variation (CV).

- Intermediate Precision: This assesses the variation within the laboratory under different conditions, such as different days, different analysts, or different reagent lots. The same samples used for repeatability are tested in triplicate over at least 5 days by two different operators [24]. If the system is fully automated, operator variance may not be required.

Table 2: Experimental Design for Assessing Precision

| Precision Level | Experimental Design | Samples | Key Calculations | Common Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability | Same day, same analyst, same reagents | Min. 2 positive & 2 negative, tested in triplicate [24] | Standard Deviation (SD), Coefficient of Variation (CV) | CV < 1/4 to 1/6 of the Allowable Total Error (ATE)* [26] |

| Intermediate Precision | Different days (e.g., 5 days), different analysts | Min. 2 positive & 2 negative, tested in triplicate by 2 operators [24] | Standard Deviation (SD), Coefficient of Variation (CV) | CV < 1/3 to 1/4 of the ATE* [26] |

ATE (Allowable Total Error) is a predefined performance goal based on clinical need, biological variation, or regulatory guidance [26].

Reportable Range

The Reportable Range (also known as the analytical measurement range) is the interval between the upper and lower levels of analyte (in this context, microorganisms) that the method can reliably detect and, for quantitative methods, quantify [24] [26]. It defines the limits of what a laboratory can report as a valid result.

Experimental Protocols:

- For Quantitative Methods: The laboratory must verify the manufacturer's claimed range or the range established during validation. This is done by testing a minimum of 3 samples that span the entire range, including concentrations near the upper and lower limits [26]. For microbial enumeration, this could involve testing dilutions of a microbial suspension from a level below the expected lower limit of quantification to a level at or above the upper limit.

- For Qualitative/Semi-Quantitative Methods: The reportable range is often defined by the cutoff values that distinguish a positive from a negative result, or that define different levels of a semi-quantitative assay (e.g., cycle threshold (Ct) cutoffs in PCR). Verification involves testing known samples positive for the analyte at these critical cutoff values [24].

Reference Range

The Reference Range defines the normal or expected result for a specific patient population or sample type. For many microbiological tests, such as those for specific pathogens, the expected result for a typical sample is "not detected" or "negative" [24].

Experimental Protocol:

- The reference range is verified by testing a minimum of 20 samples that are representative of the laboratory's typical patient population [24]. These can be de-identified clinical samples or reference materials with known negative (or normal) status. If the manufacturer's reference range does not align with the laboratory's patient population, additional testing is required, and the reference range may need to be re-defined to reflect the local population [24].

The Method Verification Workflow

The process of establishing performance characteristics is not performed in isolation but follows a logical sequence within a comprehensive verification plan. The workflow below outlines the key stages from initial planning to final implementation of a verified method.

Diagram 1: Method verification workflow.

Relationships Between Performance Characteristics

Understanding how the four core characteristics interrelate is crucial for a holistic assessment of a method's performance. Accuracy and precision, for instance, are distinct but complementary concepts that together form the basis for reliable quantification.

Diagram 2: Performance characteristics relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful execution of a verification study relies on a set of well-characterized materials and controls. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions in establishing method performance.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Verification Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Verification | Technical Specifications & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Microorganism Strains | Serves as the ground truth for accuracy and precision studies. | Obtained from recognized culture collections (e.g., ATCC, NCTC). Selected based on method specificity (e.g., E. coli for a coliform test, S. aureus for a coagulase test) [25]. |

| Clinical or Product Isolates | Provides real-world relevance and challenges method specificity. | A minimum of 20 clinically relevant isolates should be used to verify accuracy for qualitative methods [24]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Materials | Used for precision studies and ongoing monitoring of method performance. | Can be commercially available QC strains, in-house prepared samples, or de-identified clinical samples. Should include positive and negative controls [24]. |

| Sample Matrix | Assesses the impact of the sample background on method performance (recovery, interference). | For pharmaceutical testing, this could be a sterile placebo or the actual product without preservatives. For clinical testing, it could be various specimen types (e.g., sputum, urine) [25]. |

| Culture Media & Reagents | The foundational components for growth-based and non-growth-based methods. | Must be qualified for sterility and performance. Selectivity and productivity should be confirmed during specificity and accuracy assessments [25]. |

Establishing the performance characteristics of accuracy, precision, reportable range, and reference range is a non-negotiable requirement in the verification of microbiological methods. This process, guided by international standards such as the ISO 16140 series and CLSI guidelines, ensures that the data generated in the laboratory is scientifically sound, defensible, and ultimately fit for supporting patient care or product quality decisions [17] [24]. A well-designed verification study, founded on a clear plan with predefined acceptance criteria, is not merely a regulatory hurdle but a fundamental pillar of quality in microbiological science. By meticulously following the experimental protocols and leveraging the essential research reagents outlined in this guide, professionals can robustly demonstrate that their methods are reliable and ready for routine use.

Method verification is a critical, one-time study mandated by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) for unmodified, FDA-cleared tests before patient results can be reported. Its purpose is to demonstrate that a test's performance characteristics—accuracy, precision, reportable range, and reference range—align with manufacturer claims and are achievable within the user's specific laboratory environment [4]. For clinical microbiology laboratories, this process presents unique challenges, as microbiological methods often do not perfectly fit the parameters designed for analytical chemistry assays.

The foundation of a robust verification study lies in appropriate sample selection and sizing. Using an inadequate number of samples or samples that are not clinically relevant can compromise the entire verification, leading to unreliable test performance data and potential patient safety risks. This guide provides an in-depth technical framework for sample selection and sizing, detailing minimum requirements and the critical importance of clinically relevant isolates to ensure the verification study is both compliant and scientifically sound [4].

Core Principles: Verification vs. Validation and Assay Types

Before designing a verification study, it is essential to define its fundamental purpose, which hinges on two key concepts: the type of study required and the category of the assay itself.

Verification vs. Validation

The terms "verification" and "validation" are often used interchangeably but represent distinct processes with different regulatory requirements:

- Verification: Applies to unmodified, FDA-approved or cleared tests. It is a process that demonstrates a test performs according to its established performance characteristics when used in the laboratory's environment as the manufacturer intended [4].

- Validation: A more extensive process required for laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) or modified FDA-approved tests. Validation establishes that an assay works as intended for its specific application, which may involve different specimen types, sample dilutions, or altered test parameters [4].

This guide focuses on the requirements for method verification.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Assays

The type of result an assay provides—qualitative, quantitative, or semi-quantitative—directly influences the verification study design, including sample selection and the performance characteristics evaluated [4].

Table: Categories of Microbiological Testing Methods

| Assay Category | Nature of Result | Common Examples in Microbiology |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Binary result (e.g., Detected/Not Detected, Positive/Negative) | PCR detection of a specific pathogen (e.g., mecA gene) [4] |

| Semi-Quantitative | Uses a numerical cutoff to determine a qualitative result | Cycle threshold (Ct) value cutoff in real-time PCR [4] |

| Quantitative | Provides a numerical value | Viral load testing, enumeration of bacteria in a sample |

In clinical microbiology, qualitative and semi-quantitative assays are the most common types requiring verification [4]. The guidance provided herein, including minimum sample sizes, is primarily tailored to these assay types.

Minimum Sample Size Requirements for Verification

The following tables consolidate the minimum sample size requirements for verifying the key performance characteristics of qualitative and semi-quantitative assays, as derived from established clinical laboratory standards [4].

Table 1: Minimum Sample Sizes for Key Verification Characteristics

| Performance Characteristic | Minimum Sample Requirement | Sample Composition Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 20 clinically relevant isolates [4] | A combination of positive and negative samples [4]. |

| Precision | 2 positive and 2 negative samples [4] | Tested in triplicate over 5 days by 2 operators (if not fully automated) [4]. |

| Reportable Range | 3 samples [4] | Known positive samples for the detected analyte; for semi-quantitative, use samples near the upper and lower cutoff values [4]. |

| Reference Range | 20 isolates [4] | De-identified clinical or reference samples representing the standard result for the laboratory's patient population [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Sample Analysis

Adhering to standardized protocols is essential for generating reliable and defensible verification data.

Protocol for Accuracy Verification

- Sample Procurement: Obtain a minimum of 20 well-characterized isolates. These can be from certified reference materials, proficiency test samples, archived clinical samples with previous results from a validated method, or commercially available controls [4].

- Testing: Analyze all samples using the new method according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Data Analysis: Compare the results from the new method to the known or expected results. Calculate the percent agreement: (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100 [4].

- Acceptance Criteria: The calculated accuracy must meet or exceed the manufacturer's stated claims or the criteria established by the laboratory director [4].

Protocol for Precision Verification

- Sample Selection: Select at least two positive and two negative samples that represent a range of responses (e.g., strong positive, weak positive) [4].

- Testing Scheme: Test each sample in triplicate, over the course of at least five days, and include two different operators to capture between-run and inter-operator variability. For fully automated systems, operator variance may not be required [4].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percent agreement for all replicates across all days and operators: (Number of concordant results / Total number of results) × 100 [4].

- Acceptance Criteria: The precision must meet the manufacturer's stated performance or laboratory-defined criteria [4].

Sourcing and Selecting Clinically Relevant Isolates

Meeting the minimum sample size is necessary but insufficient. The clinical relevance of the isolates used is paramount to ensure the verification reflects real-world testing scenarios.

Acceptable sources for isolates and samples include [4]:

- Reference Materials and Standards: Certified strains from culture collections (e.g., ATCC).

- Proficiency Test Samples: These provide well-characterized samples with expected results.

- Quality Control Materials: Commercial controls with established performance.

- De-identified Clinical Samples: Archived patient samples that have previously been tested using a validated method. These are highly valuable as they represent the actual matrix and microbial diversity encountered in the lab.

Criteria for Clinical Relevance

When selecting isolates, consider the following to ensure clinical relevance:

- Representative of Patient Population: The isolates should reflect the spectrum of organisms and strains typically seen in your specific patient population [4]. For example, a verification study for a gastrointestinal panel should include relevant pathogens and commensals found in stool.

- Inclusion of Challenging Strains: The study should include organisms that are known to be difficult to identify or that have borderline characteristics (e.g., near the cutoff value for a semi-quantitative assay) to robustly challenge the method [4].

- Sample Matrices: If the test is approved for multiple sample types (e.g., swabs, tissue, fluid), the verification should include samples from each relevant matrix to ensure consistent performance.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for selecting and justifying clinically relevant isolates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful verification study relies on more than just microbial isolates. The following table details key reagents, materials, and resources essential for planning and executing a method verification study in clinical microbiology.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Method Verification

| Item | Function/Application in Verification |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Strains | Provide genetically and phenotypically well-defined microorganisms; serve as gold standards for accuracy testing [4]. |

| Commercial Quality Controls | Assayed controls with established expected values; used for precision and reproducibility studies [4]. |

| Proficiency Test (PT) Panels | External, blinded samples used to objectively assess the accuracy and reliability of the testing method [27]. |

| CLSI Guidance Documents | Provide standardized protocols and consensus guidelines for evaluation (e.g., EP12, M52, MM03) [4]. |

| Individualized Quality Control Plan (IQCP) Tools | Framework for developing a customized quality control plan based on a risk assessment of the testing process [4]. |

The integrity of a microbiological method verification study is fundamentally dependent on a well-considered strategy for sample selection and sizing. Adherence to the minimum sample requirements for accuracy, precision, reportable range, and reference range provides a regulatory-compliant foundation. However, true success is achieved when these samples are clinically relevant isolates that accurately reflect the laboratory's patient population and testing demands. By rigorously applying the principles and protocols outlined in this guide—from sourcing appropriate materials to justifying selections based on local epidemiology—laboratories can ensure their verification studies are robust, defensible, and ultimately guarantee the delivery of reliable patient results.

In the field of clinical and pharmaceutical microbiology, the reliability of a testing method is paramount. Before a new microbiological method can be routinely deployed to inform critical decisions on product safety or patient care, its performance must be rigorously demonstrated within the specific laboratory environment where it will be used [28]. This process, central to a broader thesis on fundamentals of microbiological method verification study design research, ensures that results are consistently accurate, precise, and dependable. Method verification is a standard practice required by regulations such as the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) for non-waived systems before patient results can be reported [4]. The core of this demonstration lies in a robust experimental design, which meticulously defines the number of replicates, the involvement of different operators, and the testing duration. These three elements collectively provide evidence that the method is under statistical control and is suitable for its intended purpose, forming the bedrock of data integrity in drug development and diagnostic research [25].

It is crucial to distinguish between the terms "validation" and "verification," as they are often used interchangeably but represent different processes. A validation is a more extensive process meant to establish that a novel or modified assay works as intended; this applies to laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) or modified FDA-approved tests [4] [29]. Conversely, a verification is a one-time study for unmodified, FDA-approved or cleared tests, meant to demonstrate that the test performs in line with the manufacturer's established performance characteristics in the user's specific environment [4] [17]. International standards, such as the ISO 16140 series for the food and feed chain, further formalize these processes, outlining distinct stages for both the initial validation of alternative methods and their subsequent verification in a single laboratory [17]. This guide focuses on the practical experimental design parameters required for a successful verification study.

Core Principles of Verification Study Design

Key Parameters and Their Definitions

The design of a verification study is built upon evaluating specific performance characteristics. The essential parameters, along with their definitions and the role of replicates, operators, and duration in their assessment, are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Performance Characteristics in Method Verification

| Parameter | Definition | Role of Replicates, Operators, & Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between a measured value and the true or expected value [25]. | Established by testing a sufficient number of samples in agreement with a reference method. |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample [25]. | Directly assessed via multiple replicates, multiple operators, and testing over multiple days to capture different sources of variation. |

| Reportable Range | The interval between the upper and lower levels of analyte (including concentrations) that the method can quantitatively measure with acceptable accuracy and precision [4]. | Verified by testing samples at the upper and lower ends of the range, often in replicates. |

| Analytical Sensitivity (Limit of Detection) | The lowest number of microorganisms that can be detected by the method under stated conditions [25]. | Determined by testing low-level challenges in multiple replicates over time to establish a detection limit with statistical confidence. |

The Interplay of Replicates, Operators, and Duration

The three core elements of this discussion are not independent; they work in concert to challenge the method under various conditions and provide a comprehensive picture of its robustness.