Foundational Protocols for Bacterial Culture: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the foundational protocols for bacterial culture, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Foundational Protocols for Bacterial Culture: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the foundational protocols for bacterial culture, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the core principles and history of bacteriology, detailed methodological applications for culturing and isolating pure strains, systematic troubleshooting for common laboratory challenges, and a comparative analysis of traditional culture versus modern molecular techniques. The content synthesizes established practices with current advancements to enhance experimental reproducibility, support pathogen identification, and inform antibiotic susceptibility testing in clinical and research settings.

The Bedrock of Bacteriology: Principles, History, and Culture Media

The late 19th century marked a revolutionary period in medical science now known as the Golden Age of Microbiology. During this transformative era, groundbreaking discoveries by Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur established the fundamental principles and techniques that form the bedrock of modern bacteriology. Their work definitively confirmed the germ theory of disease, systematically displacing long-held beliefs in spontaneous generation and miasmatic theories of illness. This paradigm shift created the scientific foundation for public health, clinical microbiology, and infectious disease control, ultimately saving millions of lives through the development of novel methodologies for pathogen identification, culture, and vaccine development [1] [2].

This whitepaper examines the specific technical contributions of Koch and Pasteur within the context of foundational protocols for bacterial culture research. For working researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these core principles remains essential for designing contemporary experimental approaches in microbial isolation, identification, and characterization. We will analyze the complementary approaches of these two pioneers—Koch's systematic methods for pure culture isolation versus Pasteur's work on attenuation and immunization—and their collective impact on establishing standardized bacteriological techniques that continue to influence modern laboratory practice [3].

Historical Rivalry and Complementary Approaches

The scientific rivalry between German physician Robert Koch (1843-1910) and French chemist Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) fueled rapid advancement in microbiological science. Despite their national and methodological differences, their work collectively established microbiology as a discrete scientific discipline [3].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Koch and Pasteur's Contributions

| Aspect | Robert Koch | Louis Pasteur |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Medical bacteriology, etiology | Fermentation, immunology, applied microbiology |

| Key Theories | Germ theory validation, Koch's postulates | Germ theory, disproval of spontaneous generation |

| Major Discoveries | Anthrax bacillus (1876), Tuberculosis bacillus (1882), Cholera vibrio (1883) | Pasteurization, anthrax vaccine (1881), rabies vaccine (1885) |

| Technical Innovations | Pure culture techniques, agar solid media, bacterial staining, microphotography | Attenuation methods, liquid culture media, vaccine development |

| Institutional Legacy | Robert Koch Institute (1891) | Pasteur Institute (1887) |

Tensions between Koch and Pasteur were influenced by the political climate following the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), during which Germany seized Alsace-Lorraine from France. Pasteur, who had been a professor at the University of Strasbourg in Alsace and whose son served in the French army during the conflict, maintained strong patriotic sentiments [3]. This national rivalry manifested scientifically in their competing approaches—Koch's German school emphasized rigid bacteriological principles and pure cultures with constant bacterial traits, while Pasteur's French school accepted bacterial variation and focused on practical applications like attenuation for vaccine development [3].

Their methodological differences were particularly evident in their approach to anthrax. Koch's meticulous work in 1876 established Bacillus anthracis as the causative agent and uncovered its spore stage, demonstrating that a specific microorganism caused a specific disease [1]. Pasteur, building on the work of French colleague Casimir Davaine, subsequently developed an anthrax vaccine in 1881 using attenuation techniques, though historical evidence suggests he initially used chemical deactivation methods developed by Toussaint [3]. Despite these conflicts, their complementary approaches collectively established the framework for modern microbiological investigation.

Foundational Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Koch's Postulates and Pathogen Identification

Robert Koch established a systematic protocol for definitively linking specific microorganisms to particular diseases. These principles, known as Koch's postulates, provided a rigorous methodological framework for disease etiology that remains influential in epidemiology and microbial pathogenesis [1] [4].

Table 2: Koch's Postulates and Modern Interpretation

| Postulate | Original Principle | Contemporary Application |

|---|---|---|

| First | The microorganism must be found in abundance in all organisms suffering from the disease, but not in healthy organisms. | Molecular detection methods (PCR, sequencing) complement culture. |

| Second | The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased organism and grown in pure culture. | Enhanced culture techniques and cellular models address fastidious organisms. |

| Third | The cultured microorganism should cause disease when introduced into a healthy organism. | Ethical constraints modified with animal models and molecular evidence. |

| Fourth | The microorganism must be reisolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as identical to the original specific causative agent. | Genomic fingerprinting confirms isolate identity. |

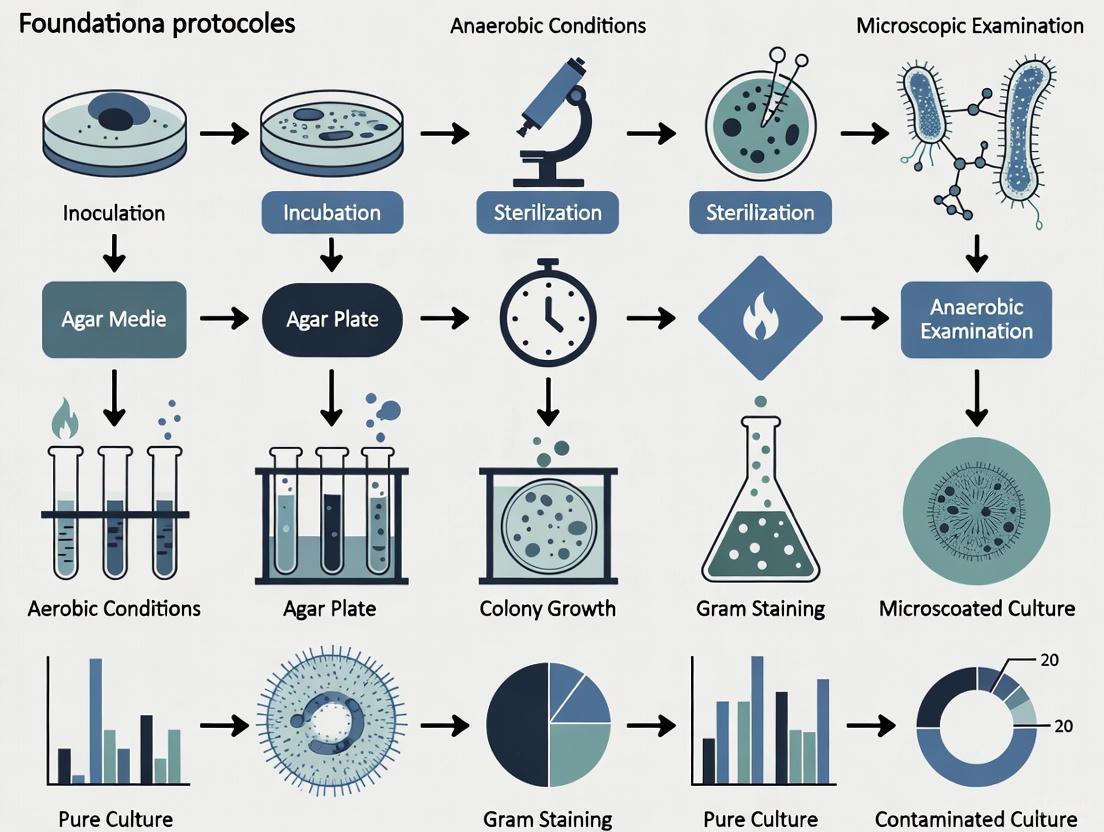

The following workflow visualizes the experimental process Koch established for pathogen identification, incorporating both his postulates and technical innovations:

Pasteur's Attenuation Method and Vaccine Development

Louis Pasteur developed revolutionary protocols for vaccine development through bacterial attenuation. His critical insight came in 1879 when an old culture of Pasteurella multocida (the causative agent of chicken cholera) was accidentally left exposed to air, resulting in diminished virulence [3]. When inoculated into chickens, this attenuated culture failed to cause disease but conferred protection against subsequent challenges with virulent strains.

The following diagram outlines Pasteur's attenuation workflow and its application to vaccine development:

Pasteur applied this attenuation principle to develop the first anthrax vaccine in 1881, which he demonstrated in a highly publicized experiment at Pouilly-le-Fort [3]. He later adapted this approach for rabies, though the rabies "vaccine" actually functioned as a post-exposure therapy rather than a true prophylactic vaccine [2].

Technical Innovations in Bacterial Culture

Evolution of Culture Media

The development of reliable culture media was essential for advancing microbiological research. Pasteur created the first liquid artificial culture medium in 1860, composed of "yeast soup," ashes, sugar, and ammonium salts [5]. This allowed for the reproducible growth of bacteria but did not enable the isolation of pure clones.

Koch recognized the limitations of liquid media and systematically evaluated solidifying agents, beginning with coagulated egg albumin, starch paste, and potato slices [1] [5]. He initially used gelatin as a solidifying agent but found it liquefied at temperatures above 25°C and was degraded by gelatinase-producing bacteria [5]. In 1881, based on a suggestion from his assistants Walther and Fanny Hesse, Koch adopted agar as a superior gelling agent [4]. Agar's unique properties—including its solid state at 37°C (the optimal temperature for human pathogens), resistance to bacterial degradation, and transparency—made it ideal for cultivating and isolating pure bacterial colonies [4].

Table 3: Evolution of Bacterial Culture Media Components

| Component Type | Specific Examples | Function | Historical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Bases | Meat extract, beef serum, yeast extract | Provides carbon, nitrogen, and essential elements | Koch's early broths used meat extracts; Pasteur used yeast-based solutions |

| Solidifying Agents | Gelatin, agar, potato slices | Creates solid surface for colony isolation | Koch initially used gelatin (1881), switched to agar (1882) |

| Selective Agents | Dyes, antibiotics, chemicals | Inhibits unwanted bacteria | Developed after antimicrobial discovery |

| Growth Factors | Purines, pyrimidines, amino acids | Provides essential metabolites | Identified through nutritional requirement studies |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The pioneering work of Koch and Pasteur established fundamental tools and reagents that remain essential in modern microbiology laboratories. The following table details key research reagent solutions from this foundational period:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials in Foundational Bacteriology

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function | Innovator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agar Solid Medium | Nutrient broth + 1.5-2% agar | Solid surface for bacterial colony isolation | Koch (adapted from Fannie Hesse's suggestion) |

| Gelatin Medium | Nutrient broth + gelatin | Initial solidifying agent (pre-agar) | Koch |

| Methylene Blue Stain | Methylene blue dye solution | Bacterial visualization under microscope | Koch |

| Bismarck Brown Stain | Bismarck brown dye solution | Bacterial differentiation in microscopy | Koch |

| Potato Slice Medium | Sterile potato slices | Natural solid medium for some bacteria | Koch |

| Yeast Extract Broth | Yeast extract, sugars, salts | Liquid culture medium for fermentation studies | Pasteur |

| Attenuated Cultures | Aged or oxygen-exposed pathogens | Vaccine development through reduced virulence | Pasteur |

| Petri Dish | Circular glass dish with cover | Container for solid media with reduced contamination | Julius Petri (Koch's assistant) |

Legacy and Modern Applications

The foundational work of Koch and Pasteur established principles and methodologies that continue to influence contemporary microbiology research and clinical practice. Koch's systematic approach to pathogen identification finds modern expression in molecular Koch's postulates, which use genetic evidence to establish disease causation [4]. The culture techniques they pioneered remain central to clinical diagnostics, pharmaceutical development, and microbiological research.

Modern automated microbial identification systems like VITEK 2 represent the technological evolution of Koch's pure culture principles, enabling rapid, high-throughput identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing [6]. Similarly, contemporary vaccine development continues to build upon Pasteur's attenuation concepts, employing genetic engineering to create precisely modified attenuated strains [2].

The institutional legacies of both scientists continue to drive infectious disease research. The Robert Koch Institute in Berlin and the global network of Pasteur Institutes (the first opening in Paris in 1888, followed by others worldwide) maintain their founders' commitment to understanding and combating infectious diseases [1] [3]. Their complementary approaches—Koch's rigorous bacteriological standards and Pasteur's applied immunological interventions—created a dual foundation upon which modern microbiology continues to build.

The Golden Age of Microbiology, defined by the contributions of Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur, established the fundamental protocols that continue to guide bacterial culture research. Their complementary approaches—Koch's systematic methodology for pathogen identification and pure culture techniques, combined with Pasteur's innovative work on attenuation and vaccine development—created a comprehensive foundation for microbiological science. The technical innovations from this period, including solid culture media, bacterial staining, and controlled attenuation methods, directly enabled the development of modern diagnostic, therapeutic, and research approaches. For contemporary researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these foundational protocols provides essential historical context and continues to inform experimental design in microbial isolation, characterization, and antimicrobial development. The legacy of this transformative period persists in every microbiology laboratory where agar plates are poured, pathogens are isolated, and novel therapeutics are developed against infectious diseases.

The successful in vitro cultivation of bacteria is a cornerstone of microbiological research, underpinning advancements in drug development, molecular biology, and microbial ecology. Central to this process is the formulation of culture media that precisely meets the nutritional requirements of the target microorganisms. This guide details the core nutritional elements—carbon, nitrogen, and growth factors—that researchers must provide to support bacterial growth, metabolism, and recombinant protein production. Framed within foundational protocols for bacteriology research, this whitepaper synthesizes current knowledge to equip scientists with the principles necessary for designing and optimizing culture conditions for diverse experimental applications.

The Triad of Bacterial Nutrition

Bacterial growth and replication require the assimilation of numerous elements from the environment. The essential nutritional requirements can be categorized into six broad classes: carbon, nitrogen, energy, growth factors, inorganic salts, and water [7]. Among these, carbon and nitrogen are the primary building blocks of cellular material, while growth factors regulate metabolic efficiency. Carbon is the most abundant element in bacterial cells, forming the structural backbone of all organic compounds, including proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids [8] [9]. Nitrogen is a fundamental component of amino acids and nucleic acids, typically constituting 12-15% of bacterial dry weight [7]. The interplay between these nutrients directly influences growth rates, metabolic pathways, and the yield of target products.

A carbon source is an organic or inorganic compound that provides the carbon skeletons for cellular biosynthesis and, for heterotrophs, serves as the primary energy source [9]. Bacteria are classified based on their carbon source utilization:

- Heterotrophs require organic carbon molecules, such as sugars, alcohols, and organic acids [8]. The majority of bacteria cultivated in laboratories are heterotrophs.

- Autotrophs utilize inorganic carbon, primarily carbon dioxide (CO₂), to synthesize organic molecules [8].

In practice, the choice of carbon source is a critical experimental parameter. Simple sugars like glucose are widely used for rapid growth, while other sources like pyruvate are employed in specialized applications, such as selective isotopic labeling for nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy studies [10]. The ability of bacteria to utilize different carbon sources is a key characteristic used in identification and classification [9].

Table 1: Common Carbon Sources in Bacterial Culture Media

| Carbon Source | Chemical Class | Example Applications | Metabolic Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Monosaccharide | General-purpose growth, high-yield protein production | Rapidly metabolized; can cause catabolite repression [8]. |

| Glycerol | Sugar alcohol | Biomass production, cryopreservation | Slower metabolism than glucose; can reduce acetate formation. |

| Lactose | Disaccharide | Recombinant protein induction (e.g., in lac operon systems) | Requires β-galactosidase for hydrolysis [8]. |

| Pyruvate | Organic acid | Selective isotopic labeling for NMR spectroscopy | Can be rapidly depleted, leading to metabolic byproducts like acetate and lactate [10]. |

| Acetate | Organic acid | Growth under nutrient limitation | Can be used as a carbon source by many bacteria after preferred sources are exhausted. |

Nitrogen is essential for the synthesis of amino acids, proteins, nucleic acids, and coenzymes. A nitrogen source is any substance that provides a bioavailable form of nitrogen for these syntheses [7]. Unlike carbon, nitrogen sources are typically not used as primary energy sources [7]. Microbes exhibit varying capabilities in nitrogen assimilation:

- Diazotrophs: Specialized bacteria capable of fixing atmospheric dinitrogen (N₂) [7].

- General Assimilators: Most bacteria utilize ammonium salts (e.g., NH₄⁺), nitrates, or organic nitrogen compounds like amino acids and peptides [7].

In complex media, nitrogen is often supplied via protein hydrolysates like peptone, tryptone, and yeast extract, which provide a mixture of amino acids and peptides [11]. In synthetic or defined media, inorganic salts such as ammonium sulfate or potassium nitrate are used to ensure consistency and reproducibility. Recent innovations explore alternative nitrogen sources, such as enzymatic hydrolysates of soy protein, for cost-effective microbial production of metabolites like nattokinase and clavulanic acid [12].

Table 2: Common Nitrogen Sources in Bacterial Culture Media

| Nitrogen Source | Type | Example Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Sulfate | Inorganic | Defined minimal media | Readily assimilated; can acidify medium as ammonium is consumed. |

| Peptone | Organic (Protein hydrolysate) | Complex media (e.g., Nutrient Broth) | A mixture of peptides and amino acids; composition can be variable. |

| Tryptone | Organic (Casein digest) | Complex media (e.g., LB Broth) | Rich in tryptophan; provides a readily available nitrogen source. |

| Yeast Extract | Organic | Complex media, vitamin source | Contains amino acids, peptides, vitamins, and minerals. |

| Soy Protein Hydrolysate | Organic | Industrial fermentation for secondary metabolites [12] | Cost-effective; supports high production yields for certain compounds. |

Growth Factors

Growth factors are organic compounds that a bacterium requires for normal metabolism but cannot synthesize de novo. They must be supplied in the culture medium in small quantities [7]. Their primary functions are to serve as precursors for important chemical substances (proteins, nucleic acids, lipids) or as components of coenzymes [7]. Based on their growth factor requirements, bacteria can be classified as:

- Prototrophs: Do not require external growth factors.

- Auxotrophs: Require specific growth factors to be added to the medium.

Common growth factors include [7] [11]:

- Vitamins: Often act as coenzymes (e.g., B vitamins for various metabolic reactions).

- Amino Acids: Required by auxotrophs that lack specific biosynthetic pathways (e.g., valine and glutamic acid for Leuconostoc mesenteroides).

- Purine and Pyrimidine Bases: Required for nucleic acid synthesis by some fastidious bacteria.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Nutritional Requirements

Protocol: Investigating Carbon Source Utilization

This protocol outlines a method for determining the ability of a bacterial strain to utilize different carbon sources, which is vital for both identification and medium optimization.

- Base Medium Preparation: Prepare a chemically defined minimal medium containing all essential inorganic salts (e.g., MgSO₄, KH₂PO₄), a nitrogen source (e.g., (NH₄)₂SO₄), and trace elements. Omit a carbon source [10].

- Carbon Source Supplementation: Dispense the base medium into sterile flasks. Supplement each flask with a filter-sterilized carbon source (e.g., glucose, pyruvate, glycerol) at an equimolar carbon concentration (e.g., 0.5-1% w/v). Include a negative control with no carbon source.

- Inoculation and Incubation: Inoculate each flask with a standardized inoculum of the test bacterium, prepared in a carbon-free buffer. Incubate under appropriate conditions (temperature, aeration).

- Growth Monitoring: Monitor bacterial growth by measuring optical density (OD) at 600 nm at regular intervals (e.g., hourly) until the culture enters the stationary phase [10].

- Metabolite Analysis (Optional): For a deeper metabolic understanding, analyze the culture medium at different time points using techniques like NMR spectroscopy to track carbon source depletion and byproduct formation (e.g., acetate, lactate) [10].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the maximum growth rate (μₘₐₓ) and final biomass yield for each carbon source to determine utilization efficiency.

Protocol: Analyzing the Impact of Organic Amendments on Nitrogen Metabolism

This protocol, adapted from a year-long anaerobic soil study, demonstrates how different organic materials, with varying carbon compositions, drive distinct nitrogen metabolic pathways [13].

- Material Preparation: Select organic amendments with distinct properties (e.g., pig-manure digestate, compost, straw powder). Sterilize materials (e.g., via γ-irradiation) to eliminate exogenous microbes. Analyze initial total organic carbon (TOC) and total nitrogen (TN) content [13].

- Experimental Setup: Establish microcosms (e.g., in serum bottles) containing a base soil or matrix. Add organic amendments normalized to an equivalent total carbon input. An inorganic fertilizer-only control should be included. Add potassium nitrate solution to standardize initial nitrate levels across treatments [13].

- Incubation and Maintenance: Maintain anaerobic conditions by replacing the headspace with pure helium. Incubate at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C) for the desired duration. For long-term studies, a second batch of amendments can be added mid-way through the incubation to simulate follow-up fertilization [13].

- Sampling and Analysis: Collect samples at multiple time points for chemical and molecular analysis:

- Chemical Analysis: Measure ammonium (NH₄⁺), nitrate (NO₃⁻), total nitrogen (TN), and total organic carbon (TOC) concentrations [13].

- Microbial Community Analysis: Extract total DNA and perform shotgun metagenomic sequencing to profile the functional genes and taxonomic composition of the nitrogen-transforming microbiome [13].

- Data Interpretation: Correlate temporal shifts in nitrogen chemistry with changes in the abundance of key microbial taxa (e.g., Ramlibacter, Lysobacter, Clostridium) and functional genes to elucidate the microbial mechanisms driving processes like mineralization or fixation [13].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Carbon Utilization Workflow

Nitrogen Metabolism Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Bacterial Nutrition Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| D-Glucose | A readily metabolizable carbon source for energy and biomass. | General propagation of heterotrophic bacteria [11]. |

| Ammonium Sulfate | A defined, inorganic nitrogen source for ammonium assimilation. | Component of M9 minimal medium for controlled experiments [10]. |

| Peptone | A complex mixture of peptides and amino acids from digested proteins. | Nitrogen and vitamin source in complex media like Nutrient Broth [11]. |

| Yeast Extract | A complex source of amino acids, nitrogen, vitamins, and trace elements. | Enrichment agent in media for fastidious bacteria [11]. |

| Agar | A polysaccharide gelling agent derived from algae. | Solidifying agent for Petri plates to isolate colonies [11]. |

| Vitamin Stocks | Aqueous or ethanolic solutions of essential vitamins (e.g., B1, B12). | Supplementation of defined media for auxotrophic strains [7]. |

| HEPES or PIPES Buffer | Chemical buffers to maintain stable pH during bacterial growth. | Cultures where metabolic activity causes significant pH shifts. |

| Trace Element Solution | A cocktail of essential metal ions (e.g., Fe, Zn, Mo, Co). | Defined media to ensure availability of cofactors for enzymes [7]. |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

Understanding microbial growth extends beyond optimal conditions. In natural environments, microbes often exist in a state of near-zero growth due to severe nutrient limitation [14]. This slow-growth state activates unique metabolic pathways and the production of secondary metabolites, presenting both a challenge and an opportunity for discovering novel compounds and genes [14]. Furthermore, the longstanding paradigm that "99% of microbes are unculturable" is being re-evaluated. Recent research on nitrogen-fixing bacteria suggests that the issue is not absolute unculturability but rather that many microbes are "difficult-to-culture" or "not-yet-cultured," often because they are rare taxa that get outcompeted in standard enrichment cultures [15]. Future research will focus on innovative cultivation strategies, such as in-situ cultivation using diffusion chambers and co-culture techniques, to access this hidden microbial diversity [11]. Finally, genomic prediction of maximum growth rates is becoming more sophisticated. Tools like Phydon integrate codon usage bias (CUB) with phylogenetic information to accurately predict the growth rates of uncultivated organisms from genome sequences, enhancing ecosystem modeling and guiding cultivation efforts [16].

The cultivation of bacteria remains a cornerstone of microbiological research, forming the foundational protocol upon which advancements in diagnostics, drug development, and molecular biology are built. As first established by Robert Koch, a pure bacterial culture is essential for studying virulence, antibiotic susceptibility, and genome sequence [17]. The efficacy of this research is fundamentally dependent on the appropriate selection and formulation of culture media, which provide the necessary nutrients and physical environment for bacterial growth and propagation. Culture media have evolved significantly since the creation of the first liquid artificial medium by Louis Pasteur in 1860 and the subsequent development of solid media by Koch, which enabled the purification of bacterial clones [18]. This technical guide provides an in-depth classification of culture media based on their physical state—liquid, solid, and semi-solid—detailing their formulations, applications, and specific protocols for their use in a research context. A thorough understanding of these media is critical for researchers and scientists engaged in drug development and bacteriological studies, as the choice of medium directly impacts experimental outcomes, reproducibility, and the validity of scientific conclusions.

The Function and Composition of Culture Media

At its core, a culture medium is designed to replicate the natural environment and meet the nutritional needs of bacteria [18]. Its primary function is to supply the essential elements for bacterial growth: water, a source of energy, carbon, nitrogen, vitamins, and minerals. The basic components of a standard medium, such as Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, typically include tryptone (a source of amino acids and peptides), yeast extract (providing vitamins, minerals, and other cofactors), and sodium chloride (to maintain osmotic equilibrium) [19] [20]. Beyond these basic nutrients, media can be tailored through additives to select for or differentiate between bacterial species.

- Selective Media: These incorporate inhibitors that suppress the growth of unwanted microbes. This is achieved using organic or inorganic components like bile salts or crystal violet (which inhibit Gram-positive bacteria), or specific antibiotics [17] [18]. For instance, bismuth sulfite agar is used to inhibit commensal organisms for the culture of enteric bacilli [17].

- Enriched Media: These are basal media supplemented with extra nutrients like blood, which provides hemin and other growth factors, to support the growth of fastidious microorganisms [17].

- Defined vs. Complex Media: Defined media have a known exact chemical composition, while complex media, such as LB, contain digest of animal or plant products which provide nutrients in a non-defined form [19] [20].

The physical state of the medium—dictated by gelling agents—determines its key applications, from achieving high cell densities in liquid broth to isolating pure colonies on solid surfaces.

Classification by Physical Formulation

Bacterial culture media are categorized into three primary physical formulations, each serving distinct and critical roles in microbiological workflows. The selection of the appropriate formulation is a fundamental decision in any experimental design.

Liquid Media (Broths)

Liquid media, or broths, are nutrient-rich solutions without a gelling agent. They are used to promote high-density bacterial growth, which is essential for obtaining sufficient biomass for downstream applications like plasmid DNA isolation, protein expression, and metabolite production [19] [20].

- Protocol for Inoculating a Liquid Bacterial Culture:

- Prepare Liquid LB: Weigh out 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 10 g NaCl per liter of distilled water. Dissolve the components and adjust the pH to 7.0 with 5 M NaOH. Adjust the final volume to 1 L [20].

- Sterilize: Decant the medium into several small bottles, loosen the caps, and sterilize by autoclaving. Tighten the caps once the medium has cooled below 40°C [20].

- Add Antibiotic: Once the sterilized medium has cooled to below 50°C, add the appropriate filter-sterilized antibiotic to the recommended working concentration (e.g., 100 µg/mL ampicillin) [19] [20].

- Inoculate: Using a sterile pipette tip or toothpick, select a single colony from a freshly streaked agar plate and drop it into the liquid LB with antibiotic [19].

- Incubate: Loosely cover the culture tube or flask to allow for aeration and incubate at 37°C for 12-18 hours in a shaking incubator (typically 150-250 rpm) [19].

- Verify Growth: After incubation, growth is characterized by a cloudy haze in the media. For precise measurements, the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) can be determined [19].

Solid Media

Solid media are created by adding a gelling agent, most commonly agar at a concentration of 1.5%, to a liquid broth base before sterilization [17] [18] [20]. The invention of the petri dish revolutionized clinical microbiology by allowing observation of colonies and limiting contamination [17]. Solid media are indispensable for isolating individual bacterial clones, quantifying viable cells, and studying colony morphology.

- Protocol for Preparing LB Agar Plates:

- Prepare LB Broth: Follow the protocol for liquid LB medium as described above [20].

- Add Agar: Just before autoclaving, add 15 g of agar per liter of LB medium and mix [20].

- Sterilize: Sterilize the medium with agar by autoclaving. Swirl the medium gently after autoclaving to distribute the melted agar evenly [20].

- Cool and Add Antibiotics: Cool the autoclaved agar medium to below 50°C (comfortable to hold) before adding heat-sensitive antibiotics. Mix thoroughly [20].

- Pour Plates: Pour approximately 30-35 mL of medium per standard 90 mm petri dish in a laminar flow hood or on a cleaned bench surface. Remove air bubbles by briefly passing a Bunsen burner flame over the surface [20].

- Dry and Store: Allow the plates to solidify, then dry them with lids slightly ajar in a laminar-flow hood for about an hour or in a 37°C incubator for 30 minutes. Store plates inverted at 4°C in the dark [20].

Semi-Solid Media

Semi-solid media are formulated with a lower concentration of agar, typically between 0.2% and 0.5%. This reduced agar content creates a soft, jelly-like consistency that is ideal for studying bacterial motility, as motile bacteria can swim through the medium, creating a diffuse zone of growth away from the inoculation line [21] [22]. They are also used in certain biochemical tests and for the maintenance and storage of cultures [22].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Media Formulations

| Formulation | Agar Concentration | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Media | 0% | High-density growth, plasmid preparation, protein expression | Supports suspension growth; suitable for scaling up volumes from mL to L [19] [20] |

| Solid Media | 1.0 - 1.5% | Isolation of pure colonies, quantification (CFU), strain storage | Provides a solid surface for colony formation; essential for cloning and purification [17] [20] |

| Semi-Solid Media | 0.2 - 0.5% | Motility assays, biochemical tests, culture storage | Soft consistency allows for visualization of bacterial movement [21] [22] |

Supporting Methodologies and Conditions for Bacterial Culture

Successful bacterial cultivation extends beyond the medium itself to encompass stringent control of incubation conditions and specialized techniques for handling and preserving cultures.

Critical Incubation Parameters

- Temperature: Most pathogenic or commensal bacterial strains are mesophiles, growing optimally at body temperature (37°C). Environmental strains may thrive at lower temperatures (25-30°C), while thermophiles require higher temperatures [21]. Some bacteria, like Rickettsia felis, have very specific temperature requirements for successful culture [17].

- Atmosphere: Bacterial species vary in their oxygen requirements [21].

- Aerobes require oxygen.

- Microaerophiles, such as Campylobacter spp., require lower oxygen levels (~5% O₂) [17].

- Anaerobes, like Clostridium species, cannot survive in oxygen and require specialized anaerobic chambers or jars [21]. The addition of antioxidants in culture media under an aerobic atmosphere has been shown to allow the growth of some strictly anaerobic species [17].

- Incubation Time: While many common pathogens grow within 24-48 hours, some fastidious species require extended incubation. For example, Bartonella species can require 12-14 days, and some isolates may need over 45 days to grow [17].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are fundamental to routine bacteriology work.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function | Example Protocol & Handling |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Stocks | Selective pressure to maintain plasmids or select for resistant bacteria. | Prepare 1000X stocks (e.g., 50 mg/mL Ampicillin in water), filter-sterilize, aliquot, and store at -20°C. Add to cooled (<50°C) sterilized media at 1:1000 dilution [19] [20]. |

| Agar | Gelling agent for solid and semi-solid media. | Add 15 g/L for solid plates or 2-5 g/L for semi-solid media before autoclaving [20]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (3%) | Substrate for the catalase test, a key biochemical identification assay. | Use a freshly prepared solution. Adding a few drops to a colony will cause immediate bubbling (O₂ production) in catalase-positive organisms (e.g., Staphylococcus) [23]. |

| Tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride | Substrate for the oxidase test. | Use a fresh 1% solution. A colony smeared on filter paper moistened with the reagent will turn dark purple within 10-20 seconds if oxidase-positive (e.g., Pseudomonas) [23]. |

Experimental Workflow and Visualization

The process of selecting and using the appropriate culture medium follows a logical sequence, from sample processing to pure culture and analysis. The diagram below outlines this core workflow in bacteriological research.

Figure 1: Media Selection Workflow. This diagram outlines the logical progression for using different media formulations to obtain a pure culture and proceed with specific experimental applications.

The meticulous classification and application of liquid, solid, and semi-solid culture media form the bedrock of bacteriological research. From the foundational work of Pasteur and Koch to the modern, optimized media used in today's clinical and pharmaceutical development laboratories, understanding the distinct roles of each formulation is non-negotiable. Liquid media enable the amplification of biomass, solid media are critical for isolation and purity, and semi-solid media facilitate the study of motility and other phenotypic traits. Mastery of their preparation, supplemented with controlled incubation conditions and the use of selective agents like antibiotics, empowers researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to reliably culture, identify, and manipulate bacterial strains. This foundational protocol is a prerequisite for all subsequent research, ensuring the integrity, reproducibility, and success of scientific endeavors in microbiology and beyond.

The selection of an appropriate culture medium is a critical foundational protocol in bacteriology, directly influencing the success and reproducibility of research and drug development. The core choice often lies between complex media and defined media, a decision that hinges on the specific requirements of the experimental or production workflow [24]. Complex media, also known as undefined media, contain ingredients of unknown exact chemical composition, such as yeast extract, peptone, or other plant or animal derivatives [24] [25]. These media provide a rich, nonspecific mixture of nutrients, vitamins, and growth factors, making them versatile for cultivating a wide array of microorganisms, particularly those with unknown nutritional requirements [26] [25]. In contrast, defined media (also called synthetic or chemically defined media) are formulated with precise, known quantities of pure chemical compounds [24] [26]. This ensures a completely reproducible and consistent environment, free of animal-derived components, which is essential for studying microbial metabolism, conducting precise physiological studies, or producing products for therapeutic use where regulatory compliance is paramount [24] [27]. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these two media types to empower researchers and scientists in making an informed selection for their foundational culturing protocols.

Core Definitions and Key Characteristics

Complex Media

Complex media are nutrient-rich growth environments whose exact chemical composition is not known. Their formulation relies on crude digest or extracts of biological materials which contain a vast and variable assortment of nutrients in undefined proportions [24] [26]. Common components include:

- Peptones: These are protein digests (e.g., from casein or meat) that provide a mixture of peptides, amino acids, and inorganic salts.

- Yeast Extract: A rich source of B vitamins, carbohydrates, and nitrogen compounds.

- Beef Extract: Provides vitamins, minerals, and organic compounds.

The primary advantage of complex media is their ability to support the growth of a wide variety of microorganisms, including fastidious bacteria with complex nutritional needs that are difficult or impossible to culture on defined media [24] [25]. They are commonly used for routine cultivation, propagation of starter cultures, and in many industrial fermentation processes. Examples of complex media include Nutrient Broth, Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), and Blood Agar [25].

Defined Media

Defined media are composed solely of known, purified chemical components of specified concentrations [24] [26]. There is no animal, plant, or yeast tissue present, and the medium is entirely free of undefined constituents. A typical defined medium will contain:

- A precise carbon source (e.g., glucose, glycerol).

- A defined nitrogen source (e.g., ammonium salts, specific amino acids).

- Inorganic salts (e.g., phosphates, sulfates, magnesium, iron).

- Vitamins and other growth factors as required by the specific microbe.

The major advantage of defined media is the high level of reproducibility and consistency they offer [28]. They are indispensable for experiments that require precise control over the nutritional environment, such as studies of metabolic pathways, nutrient requirements, or the effects of specific variables on growth [26]. Furthermore, they are mandatory in biopharmaceutical production to ensure product purity and comply with regulatory standards, as they eliminate the risk of introducing adventitious agents from animal sera [24] [27].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Complex and Defined Media

| Characteristic | Complex Media | Defined Media |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Composition | Partially or fully undefined; exact concentrations unknown [24] [25] | Fully known and specified for every component [24] [26] |

| Typical Ingredients | Yeast extract, peptone, beef extract, malt extract [25] | Glucose, ammonium sulfate, purified amino acids, defined salts and vitamins [24] |

| Reproducibility | Lower; varies between batches and suppliers [28] | High; highly consistent and reproducible between batches [28] |

| Cost | Generally lower cost | Generally higher cost due to purified reagents |

| Primary Applications | Routine cultivation, diagnostic microbiology, growing fastidious organisms, industrial fermentation [29] [25] | Metabolic studies, physiological research, recombinant protein production, vaccine and biopharmaceutical manufacturing [24] [27] |

| Regulatory Suitability | Less suitable for stringent therapeutic production due to variability and undefined nature [24] | Essential for therapeutic product manufacturing where a completely defined process is required [24] |

Strategic Selection and Market Context

Selecting the appropriate medium type is a strategic decision that impacts experimental outcomes, process scalability, and cost-effectiveness. The global market for microbiology and bacterial culture media, valued at approximately $6.03 billion in 2025, reflects the critical importance of these materials, with complex media holding a dominant share of about 35% due to their versatility and widespread use in clinical and industrial settings [29]. The decision framework for selection can be visualized in the following workflow, which guides the researcher through key questions to arrive at the optimal media type for their specific application.

Beyond the technical considerations, market trends highlight the growing adoption of ready-to-use formats, which improve workflow efficiency and reduce contamination risks [29] [30]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and automation in microbial discovery and culture screening is transforming media optimization and selection processes, enabling high-throughput testing and data-driven formulation design [29].

Experimental Protocols for Media Comparison

To empirically determine the optimal media for a specific bacterial strain, a systematic comparison of growth in complex and defined media is essential. The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for such an evaluation.

Growth Kinetics and Reproducibility Assessment

Objective: To compare the growth performance, yield, and batch-to-batch reproducibility of a bacterial culture in complex versus defined media.

Materials:

- Test Organism: A pure culture of the bacterium of interest (e.g., Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis).

- Media:

- Complex Medium: e.g., Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) or Luria-Bertani (LB) Broth.

- Defined Medium: A formulation specific to the test organism (e.g., M9 minimal medium for E. coli).

- Equipment: Sterile flasks, spectrophotometer (for measuring optical density, OD), pH meter, shaking incubator, autoclave.

Methodology:

- Media Preparation: Prepare multiple independent batches (e.g., n=5) of both the complex and defined media according to standard recipes. Sterilize by autoclaving or filtration as required. Measure and record the initial pH of each batch.

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow the test organism to mid-exponential phase in a small volume of either medium. Wash the cells by centrifugation and resuspend in a sterile saline solution to create a standardized inoculum.

- Cultivation: Aseptically inoculate each batch of media (in triplicate) with the standardized inoculum to a low starting OD (e.g., OD600 ≈ 0.05).

- Monitoring: Incubate the cultures under optimal conditions (temperature, aeration). Monitor growth by measuring OD600 at regular intervals (e.g., every 30-60 minutes).

- Data Analysis: Plot growth curves for each culture. Calculate key parameters:

- Lag Phase Duration: Time before exponential growth begins.

- Maximum Growth Rate (μmax): Calculated from the slope of the exponential phase.

- Final Cell Yield: Maximum OD600 reached.

- Reproducibility: Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) for the final cell yield across the different batches of each media type.

Expected Outcomes: As demonstrated in a comparative study with Bacillus subtilis, defined media typically provide substantially better reproducibility across batches from a single supplier and even more so when comparing media from different suppliers [28]. Complex media may support a higher maximum cell yield or faster growth rate for some organisms but will likely show greater batch-to-batch variability.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Media Preparation and Evaluation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example in Complex Media | Example in Defined Media |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptones | Provides a complex mixture of peptides and amino acids as nitrogen and carbon sources. | Tryptone, Peptone from Casein | Not Used |

| Yeast Extract | Serves as a source of B-complex vitamins, nucleotides, and other cofactors. | Yeast Extract | Not Used |

| Defined Carbon Source | Provides a known, fermentable energy source. | Not specified/defined | Glucose, Glycerol |

| Defined Nitrogen Source | Provides a known, metabolizable nitrogen source. | Not specified/defined | Ammonium Sulfate, Potassium Nitrate |

| Inorganic Salts Buffer | Maintains osmotic balance and provides essential ions; buffers pH. | Sodium Chloride, Phosphates | Magnesium Sulfate, Potassium Phosphate |

| Agar | A polysaccharide used as a solidifying agent for petri dishes and slants. | Used in solid media | Used in solid media |

| pH Indicator | A dye that changes color with pH, useful for detecting metabolic activity. | Phenol Red | Phenol Red |

| Selective Agents | Antibiotics, dyes, or other compounds that inhibit unwanted microbes. | Can be added to both media types | Can be added to both media types |

The choice between complex and defined media is a fundamental decision that underpins successful bacterial research and development. Complex media offer robustness and ease of use for general cultivation and diagnostic purposes, explaining their dominant share in the market [29]. However, their inherent variability can be a significant drawback for studies requiring precision. Defined media, while often more costly and time-consuming to formulate, provide an unparalleled level of control and consistency, making them indispensable for metabolic studies, and the production of vaccines and biopharmaceuticals [24] [27]. As the field advances, with trends pointing towards increased automation, AI-driven design, and stringent regulatory requirements, the strategic selection and optimization of culture media will remain a cornerstone of foundational protocols in bacteriology. Researchers are advised to align their media selection with their primary experimental goals, using the frameworks and protocols provided herein as a guide to establish a reliable and reproducible nutritional foundation.

In the field of bacteriological research, the integrity of experimental outcomes hinges on the rigorous exclusion of unintended microorganisms. Sterilization and aseptic technique form the foundational framework that enables researchers to maintain this purity, ensuring that observed results are attributable only to the microbes under investigation rather than to contaminants. These protocols are not merely supportive practices but are critical determinants of experimental success, influencing everything from basic culture viability to the reliability of drug development data. Within research laboratories, the consistent application of these methods protects valuable cell lines, preserves the accuracy of enumerations, and safeguards both personnel and the broader environment from potential biological hazards. This technical guide examines the core principles and procedures that constitute effective contamination control, providing a comprehensive resource for scientists dedicated to methodological excellence in bacterial culturing.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Understanding the distinction between key terms is essential for implementing appropriate contamination control strategies.

- Aseptic Technique: A set of procedures designed to prevent the introduction of contaminating microorganisms into sterile cultures, reagents, or equipment. The goal is to create a barrier between the environment and the sterile cell culture, thereby reducing the probability of contamination. [31] [32] It focuses on not introducing contamination to a previously sterilized environment.

- Sterilization: A process that eliminates all forms of viable microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and especially resistant bacterial spores, from a surface, object, or fluid. After sterilization, an object is referred to as sterile. [33] Sterile techniques are used to achieve this state of sterility, often describing the methods and the resulting condition of instruments and environments. [31]

- Clean Technique: This approach aims to reduce the overall number of germs but does not completely eliminate them. It involves using clean, but not sterile, items to minimize the transfer of microorganisms. For example, unused gloves from a box are clean but not sterile. [31]

Table: Comparison of Contamination Control Terms

| Term | Objective | Level of Microbial Control | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sterile Technique | Complete elimination of all microorganisms | Eliminates all microbes, spores, and viruses | Surgical instrument processing, preparation of culture media, parenteral drugs [31] [33] |

| Aseptic Technique | Prevent contamination of a sterile field | Maintains a previously achieved sterile state | Plating procedures, cell culture manipulations, inoculations [32] [34] |

| Clean Technique | Reduce the overall number of pathogens | Reduces microbial count but does not eliminate all | Non-sterile glove use in a doctor's office, handling of non-critical items [31] |

Sterilization Methods in Microbiology

A variety of sterilization methods are employed in research laboratories, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and ideal applications. The selection of an appropriate method depends on the nature of the material to be sterilized, including its heat stability, composition, and intended use.

Heat-Based Sterilization

Heat is the most reliable and widely used method for sterilization and can be applied as either moist or dry heat.

- Moist Heat (Autoclaving): This process uses pressurized steam to achieve rapid microbial inactivation. The mechanism of action is the hydrolysis and coagulation of cellular proteins. Typical autoclave cycles run between 3 and 30 minutes at 121–134 °C (250–273 °F). Steam sterilization is a faster process than dry heat due to the high latent heat of steam, which allows for efficient heat penetration. [35] [33] It is the method of choice for aqueous solutions, culture media, and any materials that can withstand high temperatures and moisture.

- Dry Heat (Flaming & Baking): Dry heat kills microbes primarily through the oxidation of cell constituents. This requires more energy than protein hydrolysis, necessitating higher temperatures and longer exposure times than moist heat. For example, sterilization in a hot air oven often requires at least 2 hours at 160 °C (320 °F). Dry heat is suitable for materials that might be damaged by moist heat or are impenetrable to steam, such as powders, petroleum products, and sharp instruments. [35] [36] [33] Flaming is a rapid form of dry heat sterilization used for inoculating loops and straight wires in microbiology labs, where heating the wire until it glows red ensures the inactivation of any infectious agent. [33]

Non-Thermal and Alternative Sterilization Methods

For heat-sensitive materials, several effective non-thermal alternatives exist.

- Filtration: This is a quick, heatless method for sterilizing solutions that would be degraded by heat. Filters work by passing the solution through a membrane with a pore diameter too small for microbes to pass through, typically 0.2 µm for bacterial removal. It is crucial to note that viruses and phages can pass through these filters. This method is commonly used for sterilizing thermolabile pharmaceutical fluids, serum, and antibiotic solutions. [35] [36]

- Chemical Sterilization:

- Liquid Chemicals: Chemical sterilants like glutaraldehyde and performic acid are used for medical devices that are heat-sensitive and incompatible with other methods. They require prolonged contact times (3-12 hours) and have limitations, as they cannot adequately penetrate barriers like biofilms, and their survivor curves may not provide the same sterility assurance level as thermal methods. [36]

- Gas Sterilization: Ethylene oxide gas is used to sterilize heat- and moisture-sensitive items, such as catheters and complex medical devices. It alkylates cellular components, preventing metabolism and replication. However, ethylene oxide is highly toxic, requires aeration after sterilization, and presents several health risks, making it less common in general research labs. [35] [36]

- Vaporized Hydrogen Peroxide (VHP) & Ozone: These are low-temperature sterilization systems that have been developed more recently. VHP offers rapid cycle times and leaves behind only water and oxygen as by-products. Ozone is generated from oxygen and water within the sterilizer and is converted back at the end of the cycle, making it an environmentally friendly option. [36]

- Radiation: Ionizing radiation, such as gamma rays and electron beams, is a low-temperature method that damages microbial DNA. It is highly effective and used for large-scale sterilization of medical devices and single-use consumables during manufacturing. Non-ionizing radiation, like UV light, has limited penetration and is useful for sterilizing air and exposed surfaces, such as inside laminar flow hoods between uses. [35] [32]

Table: Comparison of Common Laboratory Sterilization Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Typical Conditions | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steam (Autoclave) | Protein hydrolysis & coagulation | 121°C, 15-30 min, 15 psi [35] [33] | Culture media, aqueous solutions, surgical tools [35] [33] | Unsuitable for heat-sensitive or moisture-sensitive items [35] |

| Dry Heat (Oven) | Oxidation | 160°C for 120 min [36] [33] | Powders, sharp instruments, glassware [36] [33] | Long cycle times; high temperatures damage many materials [35] [36] |

| Filtration | Physical removal | 0.2 µm membrane pore size [35] | Thermolabile solutions (sera, antibiotics) [35] [36] | Does not remove viruses; requires pre-filtration for cloggy solutions [35] |

| Ethylene Oxide Gas | Alkylation | 3-5 hours, 37-63°C [36] | Heat- and moisture-sensitive medical devices [35] [36] | Highly toxic; requires long aeration; lengthy cycle [35] |

| Radiation (Gamma) | DNA damage | Varies with dose [35] | Industrial sterilization of plastics (e.g., pipettes, petri dishes) [35] | Not practical for lab-scale use; requires specialized facilities [35] [36] |

Sterilization Method Decision Workflow

Aseptic Technique in Practice

Aseptic technique encompasses all the practices that maintain the sterility of experimental materials during handling. Its proper execution is paramount for successful cell culture, media preparation, and all manipulations involving pure bacterial strains.

Foundational Principles

The core elements of aseptic technique can be broken down into four key areas: [31]

- Tool and Patient Preparation: All tools and instruments must be properly sterilized, typically via autoclaving. The work surface and the operator's hands are also prepared to reduce the microbial load. [31]

- Barriers: Physical barriers, such as personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves, gowns, and masks, are used to prevent cross-contamination between the user and the sterile field or culture. [31]

- Contact Guidelines: A fundamental rule is to maintain sterile-to-sterile contact only. This means sterile instruments should only touch other sterile surfaces or the culture, and non-sterile items must be excluded from the sterile field. [31]

- Environmental Controls: This involves preparing the workspace to minimize airborne contamination by working in a designated, uncluttered area, such as a laminar flow hood, and minimizing drafts and movements that could disturb the air. [31] [37]

Practical Procedures for the Microbiology Lab

The following procedures are essential for daily work in a bacteriology laboratory.

- Workspace Preparation: The laboratory bench should be clear of clutter and disinfected with a suitable agent, such as 70% ethanol or 1% Virkon, before and after work. [37] [32] A Bunsen burner is often used to create a sterile field; the updraft of the flame draws airborne contaminants away from the immediate work area. All necessary supplies should be organized within immediate reach before starting the procedure. [37] [34]

- Sterile Handling of Instruments:

- Using a Wire Loop: A wire loop is sterilized by heating it to red hot in the Bunsen burner flame before and after use. To prevent splattering, the loop should be heated gradually, starting from the base of the wire near the handle and moving the tip slowly into the hottest part of the flame. The sterile loop must be allowed to cool for a few seconds in the air before touching a culture and should not be placed on the bench surface. [37]

- Using a Pipette: Sterile pipettes should be removed from their wrapper by the end containing the cotton wool plug. After attaching a teat, the pipette barrel is held like a pen. The teat is depressed before immersion into the liquid to avoid introducing air bubbles, and then released slowly to draw up the fluid. After use, contaminated pipettes should be immediately placed in a pot of disinfectant. [37]

- Flaming the Neck of Vessels: The necks of bottles and test tubes should be passed briefly through the Bunsen burner flame after opening and before recapping. This action creates a convection current away from the opening, helping to prevent airborne microorganisms from entering the vessel. [37]

- Working with Plates and Flasks: When working with Petri dishes, exposure of the sterile inner surfaces should be limited. The lid should be lifted as little as possible and not placed on the bench; instead, it can be held over the base at an angle that shields the agar surface. Similarly, bottles and flasks should be capped when not in immediate use. [37] [32]

Aseptic Technique Core Steps

Contamination Detection and Control Strategy

Despite rigorous aseptic technique, contamination remains a risk. A proactive, comprehensive strategy for microbial control and detection is therefore essential.

Understanding potential contamination sources is the first step in mitigating risk. Key sources include: [38]

- Raw Materials: Cell lines themselves can be a source, with studies suggesting 5-35% of bioproduction cell lines have mycoplasma contamination. Biological raw materials like serum albumin can also be contaminated. [38]

- Laboratory Environment: Airflow (HVAC systems), water, and cleanroom surfaces can harbor microbes. Airborne contaminants can compromise processes, especially if filters are worn out or pressure is incorrect. [38]

- Personnel: Human error is a significant source of GMP deviations. Shed skin, dirt from clothing, and improper technique can introduce contaminants. [32] [38]

- Process Additives and Equipment: Non-sterile additives or single-use systems with manufacturing defects (e.g., micro-holes) can introduce contamination. Cross-contamination can occur between bioreactors if cleaning is insufficient, allowing biofilms to form. [38]

Detection Methods

Timely detection of contamination is critical for preventing the loss of experimental data and resources.

- Traditional Microbiological Methods: These are the cornerstone of sterility testing but are often slow. They include bioburden testing by filtration or plating methods, where filters or samples are placed in culture media and observed for microbial growth over several days up to two weeks. [38] These methods are effective but can delay process decisions.

- Rapid Microbiological Methods (RMMs): Newer technologies aim to reduce detection time. These include methods based on nucleic acid amplification (e.g., PCR) and advanced spectroscopy. One novel method uses UV absorbance spectroscopy combined with machine learning to provide a label-free, non-invasive contamination assessment in under 30 minutes, a significant improvement over traditional 7-14 day incubation periods. [39]

Experimental Protocols: Essential Plating Techniques

The following core plating methodologies are routinely used in microbiology to isolate, propagate, or enumerate bacteria. All incorporate aseptic technique to maintain sterility. [34]

Streak Plate Procedure: Isolation of Bacterial Colonies

The streak-plate procedure is designed to isolate pure cultures of bacteria, or colonies, from mixed populations by simple mechanical separation. [34]

Protocol: Quadrant Method [34]

- Preparation: Ensure the agar plate is dry and pre-warmed to room temperature. Label the bottom of the plate. Sterilize a metal loop by flaming until red hot and allow it to cool.

- First Quadrant: If the inoculum is a broth suspension, obtain a loopful. If it is a colony from another plate, gently touch the colony with the cooled loop. Lift the lid of the plate slightly and spread the inoculum over about one-quarter of the agar surface using a rapid, smooth, back-and-forth motion. Flame the loop.

- Second Quadrant: Turn the plate 90°. Touch the cooled loop to the first quadrant near the end of the last streak and drag it into the empty second quadrant, crossing over the last half of the streaks from the first quadrant. Do not go back into the first half. Fill the second quadrant with streaks. Flame the loop.

- Third and Fourth Quadrants: Repeat the process for the third and fourth quadrants, each time using a sterile loop (or re-flaming) and ensuring the loop does not go back into previous quadrants where a higher density of cells was deposited.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate upside down to prevent condensation from accumulating on the lid and falling onto the agar surface.

Objective: To obtain well-isolated single colonies derived from a single bacterium in the final quadrant.

Spread Plate and Pour Plate Procedures: Enumeration of Viable Bacteria

These methods are used to determine the concentration of viable bacteria in a liquid culture.

Protocol: Spread Plate [34]

- Prepare the Inoculum: Serially dilute the bacterial culture in a sterile diluent.

- Transfer and Spread: Pipette a small, measured volume (e.g., 100 µL) of the desired dilution onto the center of a pre-dried agar plate. Use a sterile, bent glass spreader (often dipped in ethanol and flamed to sterilize). Gently spread the liquid evenly over the agar surface by rotating the plate while the spreader is in contact with the agar.

- Incubation: Allow the liquid to absorb into the agar, then incubate the plate upside down.

Protocol: Pour Plate [34]

- Prepare the Inoculum: Serially dilute the bacterial culture as before.

- Transfer to Empty Plate: Pipette a measured volume (0.1-1.0 mL) of the dilution into an empty, sterile Petri dish.

- Add and Mix Agar: Promptly add approximately 15-20 mL of molten, but cooled, agar medium (ca. 45-50°C) to the dish. Swirl the dish gently to mix the inoculum thoroughly with the molten agar.

- Solidification and Incubation: Allow the agar to solidify completely, then incub the plate upside down.

Objective: After incubation, count the number of colonies on a plate to calculate the colony-forming units (CFU) per mL of the original culture.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Aseptic Microbiology Work

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Autoclave | Sterilizes using pressurized steam | Workhorse for media, solutions, and glassware; requires validation with biological indicators (e.g., G. stearothermophilus spores) [35] [33] |

| Laminar Flow Hood (BSC) | Provides a sterile work area via HEPA-filtered air | Essential for BSL-2 work; maintains product protection via unidirectional air; no Bunsen burner used inside [32] [34] |

| 70% Ethanol | Disinfects surfaces and gloved hands | Rapid action; used for wiping down work surfaces and equipment before use; fire hazard [37] [32] |

| Bunsen Burner | Creates an updraft sterile field; sterilizes loops | Standard for BSL-1 work on an open bench; flame used for sterilizing loops and flaming bottle necks [37] [34] |

| Sterile Pipettes | Transfers sterile liquids accurately | Disposable plastic or glass; used with a pipettor; never used more than once to avoid cross-contamination [37] [32] |

| Membrane Filters (0.2 µm) | Sterilizes heat-sensitive solutions | Removes bacteria from solutions like antibiotics or serum; does not remove viruses [35] |

| Selective & Differential Media | Grows and identifies specific microbes | Contains indicators or antibiotics to select for or differentiate between bacterial species |

Mastering Practical Techniques: Inoculation, Isolation, and Culture Conditions

Inoculation Tools and Aseptic Transfer Protocols

In microbiological research, the ability to study and characterize microorganisms fundamentally depends on working with them in a way that prevents contamination of the sample, the environment, or the researcher. Aseptic technique refers to this collection of procedures designed to prevent the introduction of unwanted organisms into pure cultures or laboratory settings [40]. These protocols are equally critical for maintaining experimental integrity and ensuring operator safety.

The core principle involves excluding contaminating microorganisms during the transfer of microbial cultures from one sterile medium to another [40]. Mastery of aseptic technique is a foundational skill for all subsequent procedures in bacteriology, from basic culture maintenance to advanced genetic and co-culture experiments. Without it, the reliability of any experimental result is compromised.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Growth Media Forms

Bacteria are cultivated in growth media, which provide the nutrients necessary to sustain their metabolism and reproduction. These media are prepared in several physical forms, each serving a distinct purpose in the laboratory [41].

- Broth (Liquid Medium): A liquid medium without agar, used for fast, luxuriant growth and for growing large quantities of bacteria [42] [41]. It is also essential for certain metabolic tests and inoculations.

- Agar Plates: Melted agar poured into Petri dishes, providing a large surface area for microbial growth. This format is ideal for isolating individual colonies, characterizing colonies, and performing certain biochemical tests [41].

- Agar Slants: Test tubes in which melted agar is allowed to solidify at an angle, creating a slanted surface. The relatively small tube opening reduces dehydration and contamination risk, making slants ideal for culturing and storing bacterial stocks for intermediate periods (weeks) [41].

- Agar Deeps: Test tubes in which melted agar is allowed to solidify vertically. This form is typically used for cultivating anaerobic bacteria or for specific differential metabolic tests [42] [41].

Sterilization vs. Disinfection

A clear understanding of decontamination methods is essential for laboratory safety and protocol integrity.

- Sterilization: The complete removal or destruction of all vegetative cells, endospores, and viruses from an item. It is an all-or-nothing process; an item is either sterile or not. Media and tools are typically sterilized using an autoclave, which employs moist heat (steam) under pressure to achieve temperatures of 121-132°C, effectively killing all life forms [41].

- Disinfection: The killing or inhibition of vegetative microbes, though bacterial spores may survive. Chemical disinfectants (e.g., chlorine bleach) are used on non-living surfaces like laboratory benches [41]. It is critical to note that a disinfected surface is not sterile.

Essential Tools and Reagents

Successful bacterial culturing requires the use of specific tools and reagents. The following table details the core components of the researcher's toolkit.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Bacterial Cultivation

| Item | Function/Description | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Inoculating Loop | Sterilizable tool, typically metal or disposable plastic, for transferring and streaking cultures [42] [40]. | – |

| Inoculating Needle | A straight, stiffer wire used for stabbing into solid media, such as agar deeps [42]. | – |

| Growth Media | Nutrient-rich substance supporting bacterial growth; can be liquid (broth) or solid (with agar) [42] [19]. | Luria Broth (LB), MRS Broth, Trypticase Soy Broth [19] [43] [44] |

| Agar | A polysaccharide from red algae used as a solidifying agent in culture media; not degraded by most bacteria [41]. | – |

| Antibiotics | Selective agents added to media to isolate bacteria carrying specific plasmid-encoded resistance genes [19]. | Ampicillin (100 µg/mL), Kanamycin (50 µg/mL), Chloramphenicol (25 µg/mL) [19] |

| Chromogenic Agar | Specialized agar containing substrates that produce colorimetric changes based on bacterial enzymatic activity, allowing for rapid preliminary identification [44]. | – |

| Disinfectant | Chemical agent used to kill or inhibit vegetative microbes on non-living surfaces [41]. | Chlorine-based solutions, Alcohol [41] |

Fundamental Aseptic Transfer Protocols

The following workflow outlines the generalized steps for aseptically transferring bacteria, which are adapted based on the source and destination media.

Diagram 1: General aseptic transfer workflow for different media types.

Detailed Transfer Procedure

The specific actions for each step in the workflow are critical for success.

- Sterilizing the Tool: The inoculating loop or needle must be sterilized by passing it at an angle through the flame of a Bunsen burner until the entire wire becomes orange from the heat, incinerating all contaminants [40]. The tool should not be laid down after sterilization to prevent recontamination.

- Removing Inoculum from a Broth Culture:

- Hold the sterile loop like a pencil and the culture tube in the other hand.

- Use the little finger of the loop hand to remove the tube cap. Never lay the cap down, and keep the open end facing downward to minimize contamination [40].

- Briefly pass the lip of the culture tube through the flame to create a convection current that forces air out of the tube.

- Keeping the tube at an angle, insert the cooled loop and remove a loopful of inoculum.

- Re-flame the lip of the tube and replace the cap [40].

- Removing Inoculum from a Plate Culture: Slightly lift the lid of the Petri dish, stab the loop into the agar away from any bacterial growth to cool it, then scrape off a small amount of the organism and close the lid [40].

- Transferring Inoculum to a Sterile Broth Tube:

- Pick up the sterile broth tube and remove the cap with the little finger of your loop hand.

- Briefly flame the lip of the tube.

- Place the loopful of inoculum into the broth and withdraw the loop.

- Re-flame the lip of the tube and replace the cap.

- Re-sterilize the loop in the flame before laying it down [40].

- Transferring Inoculum to an Agar Plate (Streaking): The goal is to separate individual bacterial cells to obtain isolated colonies.

- Primary Streaking: After obtaining the inoculum, lift the lid of the plate just enough to insert the loop. Lightly streak back and forth in one sector of the plate, making close, parallel streaks.

- Secondary Streaking: Sterilize and cool the loop again. Make a new set of nearly parallel streaks, starting from the inoculated area and crossing into a sterile area of the plate, so that about half the plate is covered.

- Tertiary Streaking: Flame and cool the loop once more. Make a final set of streaks, starting from the secondary streaks and crossing into the remaining sterile area, avoiding the first set of streaks [40].

Inoculation of Specific Culture Types

Preparing a Liquid Broth Culture from a Single Colony

Liquid cultures are used to grow high densities of bacteria, which are necessary for many applications, such as plasmid DNA isolation [19].

- Prepare Media: Prepare liquid broth (e.g., LB broth) and autoclave it. Once cooled, add the appropriate antibiotic to the correct working concentration [19].

- Inoculate: Using a sterile pipette tip or toothpick, select a single, well-isolated colony from an agar plate.

- Transfer: Drop the tip or swirl the toothpick into the liquid broth containing antibiotic [19].

- Incubate: Loosely cover the culture tube or flask (to allow aeration) and incubate at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 37°C) for 12-18 hours in a shaking incubator. Shaking is critical for oxygenating the culture, which promotes robust growth [19].

- Verify Growth: After incubation, successful growth is indicated by a cloudy haze in the media. A negative control (broth with antibiotic but no bacteria) should remain clear [19].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Liquid Culture Inoculation

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Purpose/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Volume | 2 mL (miniprep) to 1 L (large prep) | Volume depends on the required bacterial yield [19]. |

| Antibiotic Dilution | 1:1,000 from a 1000X stock | Ensures correct selective pressure without inhibiting growth [19]. |

| Incubation Temperature | 30°C or 37°C | Strain-dependent; growth is slower at lower temperatures [19]. |

| Incubation Time | 12-18 hours (37°C) | For high-copy number plasmids; longer for low-copy plasmids [19]. |

| Shaking Speed | 150-250 rpm (standard); up to 350-400 rpm (high density) | Aeration is crucial for achieving high cell density [19]. |

Advanced and Specialized Applications

Rapid Bacterial Isolation from Blood for Diagnostics

Conventional diagnosis of bacteremia relies on blood cultures, which can take days. Advanced protocols have been developed to drastically reduce this time. One recent method isolates and identifies bacteria from blood within 12 hours by bypassing prior hemocultures [44].

Diagram 2: Workflow for rapid bacterial isolation from blood samples.

The protocol's key steps are:

- Bacterial Isolation: A low-speed centrifugation step (e.g., 500g for 2 minutes) separates bacteria from blood cells in a hemoculture sample, achieving >99% red blood cell removal with a bacterial isolation efficiency of approximately 50-65% for a single spin. This efficiency can be increased to over 80% with iterative centrifugation steps [44].

- Up-Concentration: The supernatant is further up-concentrated by centrifugation at a higher force (1000g for 10 minutes) over a density medium like Percoll, which acts as a cushion to preserve bacterial viability and near-complete recovery [44].

- Identification: The final pellet is resuspended, plated onto chromogenic agar plates, and incubated overnight. Distinct colony colors allow for accurate identification of pathogenic species like Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus [44].

In Vitro Co-culture with Mammalian Cells

Co-culture systems are vital for investigating host-microbe interactions, such as the effects of probiotics on intestinal barrier function. The following protocol outlines the process for co-culturing bacteria with mammalian Caco-2 cells, which model the intestinal epithelium [43].

- Prepare Mammalian Cells: Seed Caco-2 cells on polyester filter inserts and culture for approximately 17 days to allow them to form a differentiated, polarized monolayer with tight junctions [43].

- Prepare Bacterial Inoculum: Grow the bacteria of interest (e.g., Lactiplantibacillus plantarum) on an agar plate. Pick a single colony to prepare a liquid culture in a suitable broth (e.g., MRS broth for lactobacilli) and grow to the desired phase [43].

- Establish Co-culture: On the day of the experiment, resuspend the bacterial cells in a cell culture medium appropriate for the mammalian cells. Replace the medium on the Caco-2 cell monolayer with the medium containing the bacteria [43].