Flux Balance Analysis for Microbial Communities: From Foundational Principles to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to model the metabolism of microbial communities.

Flux Balance Analysis for Microbial Communities: From Foundational Principles to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to model the metabolism of microbial communities. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts, from reconstructing genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) for individual species to coupling them for consortium-level simulation. It details core modeling methodologies like compartmentalized and dynamic FBA (dFBA), alongside advanced techniques such as flux sampling and machine learning integration to overcome limitations of traditional optimization. The scope extends to a critical evaluation of model accuracy, the impact of different reconstruction tools on predictions, and troubleshooting common challenges. The article concludes by synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for leveraging microbial community modeling in biomedical and clinical research, including drug discovery and understanding host-microbiome interactions.

Foundations of Microbial Community Metabolism: From Genomes to Constraint-Based Models

Constraint-Based Modeling is a computational approach used to study and predict the behavior of metabolic networks. The core principle involves defining a system's capabilities based on physico-chemical and biological constraints, rather than attempting to predict its precise kinetic behavior. The most widely used method within this framework is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). FBA employs linear programming to predict the flow of metabolites (or "flux") through a metabolic network, enabling researchers to compute the rate at which every reaction in the network will proceed under specified conditions. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing complex systems where comprehensive kinetic data is unavailable. In the context of microbial communities, constraint-based modeling is essential for obtaining a systems-level understanding of ecosystem functioning, elucidating metabolic exchanges between microorganisms, and predicting community dynamics and overall function [1].

Key Principles and Mathematical Foundation of FBA

Flux Balance Analysis relies on several key principles and mathematical constructs [1].

The Stoichiometric Matrix

The metabolic network is represented by a stoichiometric matrix, S, where m rows correspond to metabolites and r columns correspond to reactions. Each element ( s_{ij} ) represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j.

The Mass Balance Assumption

The model assumes a metabolic steady state, where the concentration of internal metabolites remains constant over time. This is represented by the equation: S · v = 0 where v is the vector of reaction fluxes.

Capacity Constraints

Flux capacities are constrained by lower and upper bounds: α ≤ v ≤ β These bounds represent thermodynamic and enzyme capacity constraints.

The Objective Function

FBA identifies a flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes a specified biological objective function, Z, which is typically a linear combination of fluxes: Z = cᵀv The most common objective is the maximization of biomass growth.

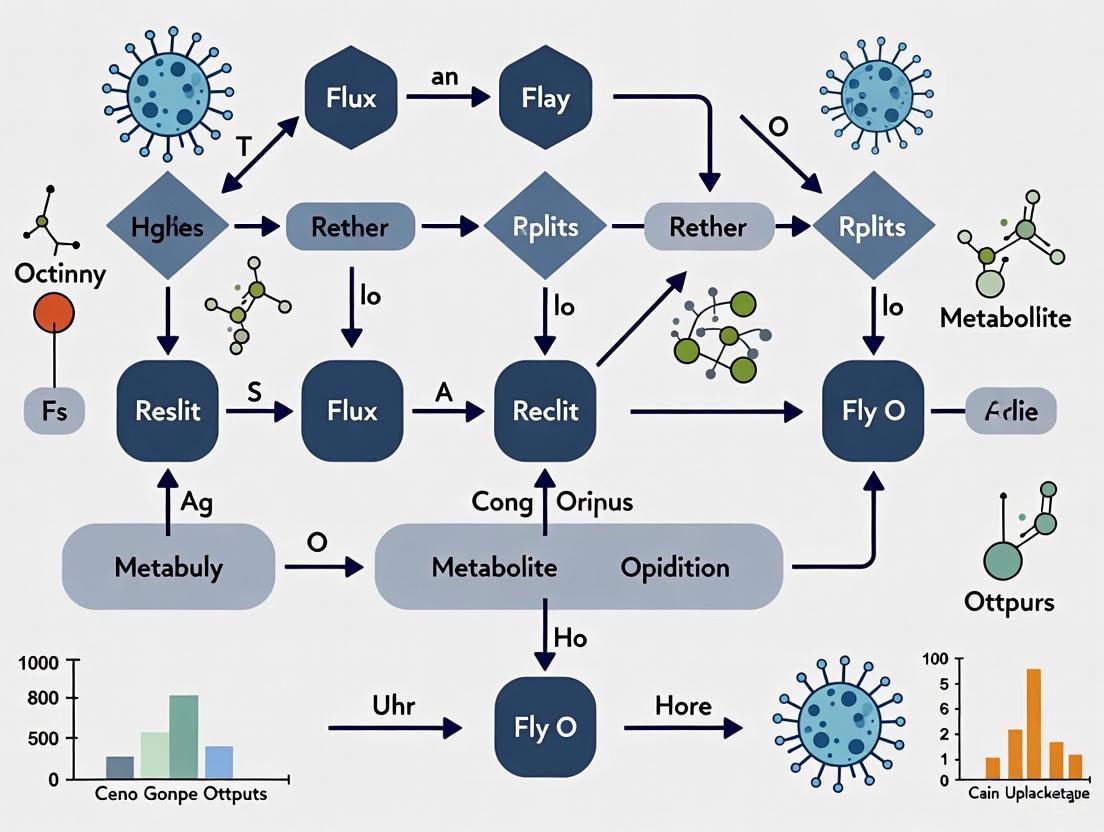

The following diagram illustrates the core computational workflow of a standard FBA simulation.

Table 1: Key Components of a Constraint-Based Model

| Component | Description | Mathematical Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | An m x r matrix encoding the stoichiometry of all metabolic reactions. | ( S ) |

| Flux Vector (v) | A vector of length r containing the flux (rate) of each reaction. | ( \vec{v} ) |

| Mass Balance | The system of equations dictating that internal metabolites are produced and consumed at equal rates. | ( S \cdot \vec{v} = 0 ) |

| Flux Constraints | The lower and upper bounds for each reaction flux, often based on thermodynamics and enzyme capacity. | ( \alpha \leq \vec{v} \leq \beta ) |

| Objective Function (Z) | A linear combination of fluxes chosen to represent a biological goal, such as biomass production. | ( Z = \vec{c}^T \cdot \vec{v} ) |

Protocols for Key FBA Experiments

This section provides detailed methodologies for performing fundamental FBA simulations, adaptable for both single organisms and microbial communities.

Purpose: To predict the metabolic capability of an organism or community to utilize different carbon substrates and the corresponding growth yield [2].

- Model and Medium Setup: Load the target Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM). Initialize the simulation with a defined minimal medium, typically containing a primary carbon source like D-glucose.

- Modify Carbon Source: Identify the exchange reaction for the desired alternate carbon source (e.g.,

EX_succ_efor succinate). Set its lower bound to a negative value (e.g., -10 mmol/gDW/hr) to allow uptake. - Remove Primary Carbon Source: Identify the exchange reaction for the original carbon source (e.g.,

EX_glc_e). Set its lower bound to 0, effectively removing it from the medium. - Solve and Analyze: Perform FBA with the objective of maximizing biomass growth. Compare the new optimal growth rate to the baseline. A lower growth rate indicates a lower growth yield on the alternate substrate.

Protocol: Simulating Anaerobic Growth

Purpose: To predict metabolic behavior and growth capacity in the absence of oxygen [2].

- Model Setup: Load the target GEM with a minimal medium containing a carbon source.

- Knock Out Oxygen Uptake: Identify the oxygen exchange reaction (

EX_o2_e). Set both its lower and upper bounds to 0, simulating an anaerobic environment. - Solve and Analyze: Perform FBA with the objective of maximizing biomass growth. An "infeasible solution" indicates no growth is possible under these conditions. A reduced but non-zero growth rate indicates fermentative or anaerobic respiratory capability.

Protocol: Analysis of Metabolic Yields

Purpose: To determine the maximum theoretical yield of a specific metabolite (e.g., ATP, a secondary metabolite, or an excreted byproduct) [2].

- Model Setup: Load the target GEM with appropriate medium conditions.

- Change Objective Function: Identify a balanced reaction that consumes the metabolite of interest (e.g., the ATP Maintenance reaction,

ATPM, for ATP yield). Set this reaction as the new objective function to maximize. - Solve and Analyze: Perform FBA. The resulting objective value is the maximum possible flux through that reaction, representing the system's maximum production capacity for the target metabolite.

Protocol: Dynamic FBA for Microbial Communities

Purpose: To simulate the time-dependent changes in metabolite availability and species abundances in a microbial community [1].

- Construct Community Model: Assemble a multi-species model by combining individual GEMs, linked through a shared extracellular environment (common metabolite pool).

- Define Community Objective: Formulate an objective for the community, which can be a weighted sum of individual species biomass functions or a different community-level property.

- Initialize and Solve at t₀: Set initial nutrient concentrations and species abundances. At each time point, perform FBA on the community model to obtain fluxes and growth rates.

- Update the System: Use the predicted growth rates to update species abundances. Update the extracellular metabolite concentrations based on the predicted exchange fluxes.

- Iterate: Repeat the FBA simulation at the next time point using the updated abundances and medium composition.

The following workflow outlines the generalized process for building and utilizing a metabolic model, from genome to simulation.

Table 2: Example FBA Simulation Results for E. coli Core Metabolism

| Simulation Type | Condition | Carbon Source | Objective | Predicted Growth Rate (h⁻¹) | Key Constraint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Growth | Baseline | D-Glucose | Maximize Biomass | 0.874 | Oxygen uptake = -18.5 mmol/gDW/hr [2] |

| Aerobic Growth | Substrate Shift | Succinate | Maximize Biomass | 0.398 | D-Glucose uptake = 0 mmol/gDW/hr [2] |

| Anaerobic Growth | Fermentation | D-Glucose | Maximize Biomass | 0.211 | Oxygen uptake = 0 mmol/gDW/hr [2] |

| Energetics | Aerobic | D-Glucose | Maximize ATPM | 175.0 | ATP yield, not growth [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Constraint-Based Modeling and FBA

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Function and Description |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Toolbox | A MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling, supporting model reconstruction, simulation, and analysis [2]. |

| COBRApy | Software Library | A Python-based toolkit that provides core functions for reading, writing, and simulating constraint-based models [2]. |

| Escher-FBA | Web Application | An interactive, web-based tool for performing FBA directly within a metabolic pathway visualization; ideal for beginners and exploratory analysis [2]. |

| BiGG Models | Knowledgebase | A curated database of high-quality, published genome-scale metabolic models. Used to obtain reliable starting models for simulation [2]. |

| CarveMe | Software Tool | An automated platform for the reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models from genome annotations [3]. |

| antiSMASH | Software Tool | A genome mining tool used to identify biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) for secondary metabolites, crucial for expanding models to include secondary metabolism [3]. |

| GLPK (GNU Linear Programming Kit) | Solver | An open-source solver for linear programming problems; the computational engine used by many FBA tools to find optimal flux distributions [2]. |

Application in Microbial Communities: Status and Outlook

The extension of FBA to microbial communities (cFBA) introduces additional layers of complexity but is vital for understanding and engineering microbiomes [1]. Two primary modeling schemes exist:

- Steady-State Community FBA: Models the community as a unified metabolic network at a fixed composition, optimizing a community-level objective.

- Dynamic FBA (dFBA): Simulates the temporal evolution of the community by coupling FBA at each time step with differential equations that update metabolite concentrations and species abundances.

Key challenges in community modeling include [1] [3]:

- Defining a Community Objective: Choosing biologically relevant objective functions (e.g., total community biomass, specific metabolite production) is non-trivial.

- Model Integration and Curation: Seamlessly combining metabolic models from different sources and of varying quality remains an open problem.

- Parameterizing Exchange Fluxes: It is difficult to experimentally determine individual species' contributions to net extracellular flux measurements.

Future outlooks point towards the increased reconstruction of models incorporating secondary metabolism (smGSMMs), which is crucial for understanding the production of compounds mediating ecological interactions [3]. Furthermore, the development of more sophisticated multi-objective optimization techniques and the integration of multi-omics data (metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics) as constraints will enhance the predictive power of community FBA models.

Microbial communities, such as the human gut microbiota, perform emergent activities that are fundamentally different from those carried out by their individual members [4]. These communities are shaped by complex networks of metabolic interactions, with cross-feeding—the exchange of metabolites between microorganisms—being a core process [4]. Understanding these interactions is essential for manipulating microbial communities for therapeutic purposes, such as drug development and managing diseases linked to microbiome dysbiosis [4]. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and other genome-scale modeling approaches provide a powerful mathematical framework to quantify these interactions, predict community behavior, and identify keystone metabolites and taxa [4] [5]. This Application Note details the experimental and computational protocols used to define microbial communities through their metabolic interactions.

Key Metabolic Interactions in Microbial Communities

Cross-feeding interactions are a dominant force in structuring microbial ecosystems. These exchanges can involve various metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), amino acids, organic acids, and gases [4]. The table below summarizes the primary types of metabolic cross-feeding interactions.

Table 1: Key Metabolites in Microbial Cross-Feeding Interactions

| Metabolite Class | Specific Metabolites | Producer Taxa Examples | Consumer Taxa Examples | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Acetate, Butyrate, Propionate | Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia | Energy for host colonocytes, immune regulation, pH balance [4] |

| Organic Acids | Lactate, Succinate | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus | SCFA producers | Metabolic intermediates in fermentation pathways [4] |

| Amino Acids | Phenylalanine, Tyrosine, Tryptophan | Engineered auxotrophs (e.g., E. coli ΔpheA) | Engineered auxotrophs (e.g., E. coli ΔtyrA) | Essential biomass precursors; bidirectional exchange can drive population dynamics [6] |

| Gases | H₂ | Fermentative bacteria | Methanogenic archaea (e.g., Blautia hydrogenotrophica) | Electron donor for methanogenesis [4] |

| Complex Carbohydrate Degradation Products | Monosaccharides, Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs) | Bacteroides spp., Bifidobacterium bifidum | Bifidobacterium longum, butyrate producers | Primary cross-feeding currency in fiber fermentation [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Cross-Feeding

Protocol: Investigating Amino Acid Cross-Feeding in Synthetic Communities

This protocol is adapted from experimental work that demonstrated robust population cycles in an engineered mutualism [6].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Amino Acid Cross-Feeding Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Amino Acid Auxotrophs | Genetically engineered microbial strains (e.g., E. coli ΔtyrA and ΔpheA) that lack the ability to synthesize specific essential amino acids, creating obligate cross-feeding dependencies [6]. |

| Minimal Media | A defined growth medium lacking the essential amino acids that the auxotrophic strains require, forcing them to engage in cross-feeding for survival [6]. |

| External Amino Acid Supplementation | Stock solutions of phenylalanine and tyrosine used to modulate the obligation for cross-feeding (e.g., no, low, moderate, and high supply) in the experimental media [6]. |

| Glucose Solution | The primary carbon and energy source that both auxotrophs compete for, creating a mixed interaction of mutualism and competition [6]. |

| Fluorescent Protein Tags | Genes for different fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP) expressed in each strain to enable tracking of their individual population densities over time via flow cytometry [6]. |

2. Methodology

- Strain Preparation: Inoculate monocultures of E. coli ΔtyrA and ΔpheA in rich media and grow overnight. Harvest cells and wash twice in sterile, carbon-free minimal media to remove residual amino acids.

- Co-culture Inoculation: Combine the two washed strains in a defined ratio (e.g., 1:1) into fresh minimal media supplemented with glucose and a defined concentration of external amino acids (see table below for conditions).

- Serial Batch Cultivation: Incubate the co-culture with shaking. Every 24 hours (or at the chosen period), perform a dilution by transferring a fraction (e.g., 1:100) of the culture into fresh media. Repeat this process for at least 10 days.

- Data Collection:

- Population Dynamics: At each passage, measure the optical density (for total biomass) and use flow cytometry to quantify the relative abundance of each fluorescently tagged strain.

- Resource Profiling: In parallel experiments, periodically sample the culture supernatant and quantify the concentrations of glucose, phenylalanine, and tyrosine using HPLC or enzymatic assays.

3. Expected Outcomes and Data Interpretation

Table 3: Experimental Conditions and Corresponding Dynamical Behaviors

| External Amino Acid Supply | Observed Community Dynamics | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| None | Convergence to a stable equilibrium | Obligate cross-feeding stabilizes the community at a fixed composition [6]. |

| Low | Sustained, large-amplitude period-two oscillations | Cross-inhibition of amino acid production creates internal feedback that drives cyclical population dynamics [6]. |

| Moderate/High | Convergence to an equilibrium or exclusion of one strain | External supply reduces dependency on mutualism, allowing competitive dynamics to dominate [6]. |

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for serial batch co-culture of amino acid auxotrophs.

Protocol: Community-Level Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

This protocol outlines the procedure for constructing and simulating a metabolic model of a microbial community to predict cross-feeding outcomes [5].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Components for Community-Level FBA

| Component | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) | Curated, organism-specific computational reconstructions of metabolic networks, detailing all metabolic reactions and genes [4]. |

| Universal Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | A mathematical framework that integrates individual GSMMs into a single community model, defining stoichiometry for extracellular, transport, and intracellular reactions [5]. |

| Constraints | Experimentally measured or theoretically defined limits on reaction fluxes (e.g., substrate uptake rates, ATP maintenance) [5]. |

| Optimization Solver | Software (e.g., COBRA, COBRApy) used to solve the linear programming problem and find a flux distribution that optimizes a community objective [4]. |

2. Methodology

- Model Compilation: Gather or reconstruct high-quality Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) for each species in the community of interest.

- Construct Universal Stoichiometric Matrix: Create a compartmentalized model that includes:

- Extracellular Metabolites (Me): Metabolites in the shared environment.

- Intracellular Metabolites (Mi): Metabolites within each organism's unique compartment.

- Extracellular Reactions (Ne): Uptake and secretion of metabolites from the environment.

- Transport Reactions (Nt): Movement of metabolites between the extracellular space and each organism's intracellular compartment.

- Intracellular Reactions (Ni): Metabolic reactions within each organism [5].

- Define Constraints: Apply constraints to the model based on experimental conditions, such as:

- Nutrient availability in the media.

- Maximum uptake rates for carbon sources.

- Organism-specific growth requirements.

- Define Objective Function: Choose a community-level objective to optimize. Common choices include maximizing the total community biomass or maximizing the production rate of a specific metabolite (e.g., butyrate).

- Solve and Simulate: Use an optimization solver to find a flux distribution that satisfies the constraints and optimizes the objective function. The output provides predicted growth rates for each member and the exchange fluxes of all metabolites.

- Model Validation: Compare model predictions (e.g., relative species abundances, metabolite profiles) with experimental data from co-culture studies to validate and refine the model [4].

Figure 2: Structural framework for community-level Flux Balance Analysis.

Data Presentation and Modeling Outputs

Quantitative models generate testable predictions about community behavior. The following table summarizes the output from a community-level FBA simulation of a microbial fuel cell (MFC) community under different organic loading rates (OLRs), demonstrating how cross-feeding shapes community structure [7].

Table 5: FBA-Predicted Microbial Guild Abundance and Metabolic Cross-Feeding in a Microbial Fuel Cell under Variable Organic Loading

| Organic Loading Rate (OLR) | Sulfide-Oxidizing Bacteria (SOB) Relative Abundance | Methanogens (MET) Relative Abundance | Dominant Cross-fed Metabolite | Primary Metabolic Interaction | MFC Performance (Current Generation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (L-OLR) | High (∼65%) | Low (∼15%) | Acetate from SRB to SOB | SRB and SOB coupling via S-cycle and acetate | High [7] |

| High (H-OLR) | Low (∼20%) | High (∼65%) | Acetate and H₂ from SRB to MET | Competitive cross-feeding; MET outcompete SOB for acetate | Declined [7] |

Defining microbial communities requires an integrated understanding of their metabolic interactions, particularly cross-feeding. Experimental approaches using synthetic co-cultures reveal the dynamic consequences of these interactions, such as stable equilibria or oscillatory dynamics [6]. Computational frameworks like community-level Flux Balance Analysis provide a mechanistic, quantitative platform to predict how these interactions shape community structure and function in response to environmental perturbations [5] [7]. The synergy between controlled experiments and genome-scale modeling is a powerful paradigm for advancing microbial ecology and developing novel therapeutic strategies aimed at manipulating the human microbiome.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational frameworks that provide a systematic representation of the metabolic network of an organism. They integrate gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations for nearly all metabolic genes, incorporating data on stoichiometry, compartmentalization, biomass composition, and thermodynamic constraints [8]. By imposing systemic constraints on the entire metabolic network, GEMs enable researchers to predict cellular metabolic capabilities and responses under diverse conditions, making them indispensable tools for systems biology and metabolic engineering [8] [9]. The first GEM was reconstructed for Haemophilus influenzae in 1999, and since then, the modeling approach has expanded to encompass thousands of organisms across bacteria, archaea, and eukarya, including important model organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [9].

The core strength of GEMs lies in their ability to serve as a platform for integrating diverse omics data, such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, facilitating a holistic understanding of cellular physiology [8] [9]. Recent advancements have further led to the development of multiscale models, such as enzyme-constrained GEMs (ecGEMs) and strain-specific GEMs (ssGEMs), which incorporate additional layers of biological information to enhance predictive accuracy [8]. These models have found widespread applications in various fields, including strain development for bio-based chemical production, drug target identification in pathogens, and the study of host-microbe interactions [9] [10] [11].

The Stoichiometric Matrix: Foundation of Constraint-Based Modeling

Mathematical Definition and Mass Balance

At the heart of every constraint-based metabolic model lies the stoichiometric matrix, denoted as S. This m × r matrix (where m is the number of metabolites and r is the number of reactions) mathematically represents the network topology of the metabolic system [12]. Each element Sᵢⱼ of the matrix corresponds to the net stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j.

The fundamental equation governing constraint-based modeling is the mass balance equation, which assumes that the concentration of internal metabolites remains constant over time (steady-state assumption). This is represented as: S · v = 0 Where v is the r × 1 flux vector containing the reaction rates (fluxes) [12]. This equation dictates that for each metabolite in the network, the weighted sum of fluxes producing it must equal the weighted sum of fluxes consuming it.

Chemical Moisty Conservation and Network Topology

Beyond mass balance, the stoichiometric matrix also encodes information about chemical moiety conservation. Metabolites that are solely recycled, such as ATP, NAD(P)H, and coenzyme A, impose constraints on the maximum concentration of their corresponding chemical moieties [12]. These conservation relationships create linear dependencies between the rows of the stoichiometric matrix and define the linkage relationships between metabolite concentrations.

The structure of the stoichiometric matrix has important implications for network analysis. The rank of the matrix determines the number of independent metabolites, while the null space of the matrix defines all possible steady-state flux distributions [12]. Decomposition of the stoichiometric matrix reveals the flux modes—pathways through the network along which every metabolite is at steady state. These can be visualized as either cycles or routes from source to sink metabolites [12].

Table 1: Key Properties of the Stoichiometric Matrix and Their Biological Interpretations

| Mathematical Property | Symbol/Equation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | m × r | Number of metabolites × Number of reactions |

| Matrix Element | Sᵢⱼ | Net stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j |

| Mass Balance | S · v = 0 | Steady-state assumption: metabolite production = consumption |

| Rank | rank(S) | Number of independent metabolites in the network |

| Left Null Space | L · S = 0 | Defines metabolite conservation relationships |

| Right Null Space | S · K = 0 | Defines all possible steady-state flux distributions |

Figure 1: The role of the stoichiometric matrix in constraint-based modeling. The matrix serves as the foundational element for formulating mass balance constraints, which together with physiological constraints and an objective function, enables flux prediction through Flux Balance Analysis.

Protocol for GEM Reconstruction and Simulation

GEM Reconstruction Workflow

The reconstruction of high-quality GEMs follows a systematic multi-step process that transforms genomic information into a computational model. For well-characterized organisms like S. cerevisiae, consensus models such as Yeast8 and Yeast9 have been developed through community efforts, incorporating updates to gene-protein-reaction associations, mass and charge balances, and thermodynamic parameters [8]. The general workflow applies to both manual and automated reconstruction approaches.

Step 1: Draft Reconstruction

- Genome Annotation: Identify metabolic genes from genome sequences using databases like KEGG and EcoCyc [13] [9].

- Reaction Inclusion: Compile all known metabolic reactions associated with the annotated genes, ensuring mass and charge balance for each reaction [12].

- Compartmentalization: Assign intracellular reactions to appropriate subcellular compartments based on experimental evidence or homology [8].

Step 2: Network Refinement

- Gap Filling: Identify and fill gaps in metabolic pathways that would prevent the synthesis of essential biomass components [14].

- Biomass Definition: Define a biomass reaction that incorporates all essential biomass precursors (e.g., amino acids, nucleotides, lipids) in experimentally determined proportions [12] [9].

- Transport Reactions: Include exchange reactions that allow metabolites to be transported between compartments and taken up from or secreted into the extracellular environment [15].

Step 3: Model Validation

- Growth Simulation: Test the model's ability to simulate growth on different carbon sources and under varying environmental conditions [9].

- Gene Essentiality: Compare predicted essential genes with experimental gene knockout data to assess model accuracy [9].

- Qualitative Checks: Use tools like MEMOTE to systematically check for dead-end metabolites, charge imbalances, and futile cycles [14].

For non-model yeast species and less characterized organisms, automated reconstruction tools such as the RAVEN Toolbox and CarveFungi can generate draft models, which then require extensive manual curation to produce high-quality models [8].

Flux Balance Analysis Protocol

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is the primary method for simulating GEMs to predict metabolic fluxes. The following protocol outlines a standard FBA implementation for predicting growth rates or metabolite production [12] [15].

Step 1: Model Initialization

- Load the GEM in Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) format.

- Identify the biomass reaction and set it as the objective function for optimization.

- Map exchange reactions that simulate metabolite transport between the organism and environment [15].

Step 2: Define Environmental Conditions

- Set the bounds of exchange reactions to define available nutrients in the medium.

- Constrain uptake rates based on experimental measurements or literature values.

- Define constraints for irreversible reactions (lower bound ≥ 0) [12] [15].

Step 3: Solve the Optimization Problem

- Formulate the linear programming problem:

- Objective: Maximize Z = cᵀ · v (where c is a vector indicating the objective function, typically biomass production)

- Subject to: S · v = 0 (mass balance)

- And: vₗ ≤ v ≤ vᵤ (flux constraints)

- Use optimization solvers (e.g., COBRApy in Python) to find the optimal flux distribution [15].

Step 4: Analyze Results

- Extract the optimal growth rate (flux through biomass reaction).

- Analyze flux distributions through specific pathways of interest.

- Compare predictions with experimental data for validation [15] [14].

Table 2: Example Medium Composition for Microbial Growth Simulation [15]

| Category | Component | Symbol/Unit | Concentration | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Source | Glucose | glc_De (mM) | 27.8 | Primary carbon and energy source |

| Nitrogen Source | Ammonium | nh4_e (mM) | 40 | Nitrogen source for amino acids & nucleotides |

| Mineral Salts | Phosphate | pi_e (mM) | 2 | Component of nucleic acids, ATP, phospholipids |

| Electron Acceptor | Oxygen | o2_e (mM) | 0.24 | Terminal electron acceptor for aerobic respiration |

| Physical Parameters | pH | - | 7.1 | Optimal for many microorganisms |

| Temperature | °C | 37 | Physiological temperature |

Figure 2: GEM reconstruction and simulation workflow. The process begins with genome annotation and proceeds through draft reconstruction, network refinement, and validation before the model can be used for Flux Balance Analysis.

Application Notes for Microbial Community Modeling

Modeling Multi-Species Systems

GEMs can be extended to model microbial communities, enabling the study of metabolic interactions between different species. Three principal tools have been developed for this purpose, each employing distinct approaches to simulate community metabolism [14].

COMETS (Computation of Microbial Ecosystems in Time and Space)

- Incorporates spatial dimensions and temporal dynamics through dynamic FBA.

- Simulates changes in biomass and metabolite concentrations over time.

- At each iteration, updates uptake bounds based on nutrient availability in the environment.

- Suitable for simulating batch processes and spatial community structures [14].

MICOM (Microbial Community Modeling)

- Uses relative abundance data from sequencing as a proxy for taxon abundances.

- Implements a cooperative trade-off approach balancing optimal community growth with individual species growth.

- Applies quadratic regularization (L2) to maintain consistency with observed abundances.

- Supports multiple optimization strategies including "moma" (minimization of metabolic adjustment) [14].

Microbiome Modeling Toolbox (MMT)

- Performs pairwise screens for microbe-microbe interactions using merged models.

- Optimizes growth rates for each species individually (monoculture) and simultaneously (co-culture).

- Infers interactions by comparing growth rates in mono- versus co-culture.

- Can incorporate relative abundance data from sequencing into community models [14].

Table 3: Comparison of Community Modeling Tools Based on Flux Balance Analysis [14]

| Tool | Primary Approach | Community Objective | Temporal Dynamics | Spatial Dimensions | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMETS | Dynamic FBA | Maximizes individual species growth | Yes | 2D or 3D | Batch processes, Spatial structure |

| MICOM | Cooperative trade-off | Balances community and individual growth | No | No | Gut microbiome, Metagenomic data |

| MMT | Pairwise comparison | Compares mono- vs. co-culture growth | No | No | Interaction screening, Host-microbe |

Case Study: Probiotic Interactions for Parkinson's Disease

A practical application of GEMs in microbial community research involves evaluating probiotic strains for managing Parkinson's disease. The following case study demonstrates how FBA and dynamic FBA (dFBA) can assess the reliability and safety of probiotic combinations [15].

Objective: Evaluate potential negative interactions between probiotic strains recommended for Parkinson's disease management, particularly focusing on their metabolism of L-DOPA, the primary medication for this condition.

Methods:

- Strain Selection: Select candidate strains such as E. coli Nissle 1917 and Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 based on probiotic recommendations.

- Model Preparation:

- Use iDK1463 model for E. coli Nissle 1917 (1463 genes, 2984 reactions)

- Use the Teusink model for L. plantarum WCFS1 (721 genes, 643 reactions)

- Engineer the E. coli model to produce L-DOPA by introducing HpaBC hydroxylase enzyme

- Simulation Conditions:

- Set up a simulated gut environment with defined metabolite concentrations

- Implement FBA to predict metabolic footprints of individual strains

- Apply dFBA to simulate co-culture dynamics and metabolite exchange

- Safety Assessment:

- Screen for harmful metabolite production

- Identify potential for L-DOPA metabolism that could reduce drug efficacy

- Exclude strains with tyrosine decarboxylase activity that could metabolize L-DOPA [15]

Results: FBA analysis revealed that Enterococcus faecium possesses the gene for tyrosine decarboxylase, which could prematurely metabolize L-DOPA, reducing its therapeutic efficacy. This finding led to its exclusion from the proposed probiotic consortium, demonstrating the utility of GEMs in screening for detrimental drug-microbe interactions [15].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GEM Reconstruction and Simulation

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Database | Function and Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEM Reconstruction Tools | RAVEN Toolbox | Automated reconstruction of draft GEMs from genomic data | [8] |

| CarveFungi | Specialized tool for automated GEM reconstruction in fungi | [8] | |

| Model Quality Assessment | MEMOTE | Systematic testing of GEM quality including mass/charge balance | [14] |

| Model Databases | AGORA2 | Curated strain-level GEMs for 7,302 gut microbes | [11] |

| Simulation Environments | COBRApy | Python toolbox for constraint-based modeling and FBA | [15] |

| Community Modeling | COMETS | Dynamic FBA with spatial and temporal dimensions | [14] |

| MICOM | Microbial community modeling with abundance constraints | [14] | |

| Microbiome Modeling Toolbox | Pairwise screening of microbe-microbe interactions | [14] | |

| Biochemical Databases | KEGG, EcoCyc | Foundational databases for pathway information and genome annotation | [13] [9] |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

The applications of GEMs continue to expand into increasingly complex biological systems. In host-microbe interaction studies, GEMs enable the exploration of metabolic interdependencies and cross-feeding relationships, providing systems-level insights into host-microbe dynamics [10]. For drug development, GEMs of pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis have been used to predict metabolic responses to antibiotic pressure and identify potential drug targets [9]. The integration of GEMs with machine learning approaches and the continued development of multiscale models that incorporate enzyme kinetics and regulatory information represent promising future directions for the field [8] [13].

As the development of GEMs continues to evolve, these models are expected to play an increasingly important role in pioneering physiological and metabolic studies, particularly in the context of complex microbial communities and their interactions with host systems [8] [11]. The core components—the genome-scale metabolic model and its foundational stoichiometric matrix—will remain essential frameworks for integrating biological knowledge and generating testable hypotheses in systems biology and metabolic engineering.

Reconstructing Metabolic Networks from Genomic and Metagenomic Data

Genome-scale metabolic network reconstructions represent structured knowledge-bases that abstract the biochemical transformations within a target organism [16]. For microbial communities, these reconstructions provide a mechanistic framework to understand metabolic capabilities and interspecies interactions [10]. The reconstruction process translates genomic and metagenomic data into a mathematical model that can simulate phenotypic states using constraint-based methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [17] [18]. FBA calculates the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network, enabling predictions of growth rates or metabolite production by optimizing a biological objective function under stoichiometric and environmental constraints [17]. This protocol details the application of these approaches to reconstruct metabolic networks from both isolate genomes and complex metagenomic data, framed within the context of flux balance analysis for microbial communities research.

Background and Principles

Conceptual Foundations of Metabolic Reconstruction

Metabolic network reconstructions are biochemical, genetic, and genomic (BiGG) knowledge-bases compiled from an organism's genome annotation and biochemical literature [16]. The reconstruction process is inherently bottom-up, based on genomic and bibliomic data [16]. The resulting network encapsulates all known metabolic reactions for an organism and the genes that encode each enzyme [17].

The conversion of a reconstruction into a computational model enables the study of network properties, hypothesis testing, phenotypic characterization, and metabolic engineering [16]. For microbial communities, these models simulate metabolic fluxes and cross-feeding relationships, allowing exploration of metabolic interdependencies and emergent community functions [10].

Mathematical Basis of Flux Balance Analysis

Flux Balance Analysis is a constraint-based approach that analyzes metabolic networks at steady-state conditions [17]. The core mathematical representation is the stoichiometric matrix S, of size m × n, where m represents metabolites and n represents reactions [17]. The steady-state mass balance equation is:

Sv = 0

where v is the flux vector of all reaction rates in the network [17]. This equation defines the system constraints, ensuring that total production and consumption of each metabolite are balanced.

FBA identifies an optimal flux distribution by maximizing or minimizing an objective function Z = cTv, which is typically a linear combination of fluxes [17]. Common biological objectives include biomass production, ATP synthesis, or synthesis of specific metabolites. The optimization is solved using linear programming:

Maximize Z = cTv Subject to: Sv = 0 vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax

where vmin and vmax represent lower and upper bounds on reaction fluxes [17].

Table 1: Key Components of Constraint-Based Metabolic Models

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | m × n matrix | Biochemical transformation relationships |

| Flux Vector (v) | v = (v₁, v₂, ..., vₙ)T | Rate of each biochemical reaction |

| Mass Balance Constraints | Sv = 0 | Metabolic steady-state assumption |

| Flux Constraints | vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax | Thermodynamic and capacity constraints |

| Objective Function | Z = cTv | Biological objective to be optimized |

Protocol: Metabolic Network Reconstruction from Genomic Data

This protocol describes the comprehensive process for building a high-quality genome-scale metabolic reconstruction, which typically requires 6-24 months depending on the target organism and available data [16].

Stage 1: Draft Reconstruction Assembly

Step 1.1: Genome Annotation and Initial Reaction List

- Obtain the genome sequence of the target organism

- Identify genes encoding metabolic enzymes using annotation tools (RAST, KEGG, BioCyc) [16] [19]

- Compile an initial list of metabolic reactions based on enzyme annotations

- Document the genomic evidence (gene locus tags) for each reaction

Step 1.2: Compartmentalization

- For eukaryotic organisms, assign intracellular localization to reactions and metabolites

- Use protein localization prediction tools (PSORT, PA-SUB) [16]

- Add transport reactions between cellular compartments

Step 1.3: Stoichiometric Matrix Construction

- Represent the network as a stoichiometric matrix S

- Each column corresponds to a reaction, each row to a metabolite

- Negative coefficients for substrates, positive coefficients for products [17]

Stage 2: Network Refinement and Curation

Step 2.1: Gap Analysis and Filling

- Identify blocked metabolites that cannot carry flux

- Add missing reactions to connect disconnected network components

- Use biochemical literature and phylogenetic analysis to justify additions

Step 2.2: Directionality Assignment

- Assign reaction directionality based on thermodynamic calculations

- Use pKa prediction tools (pKa Plugin, pKa DB) to estimate metabolite properties [16]

- Apply network consistency checks (e.g., no energy-generating cycles)

Step 2.3: Biomass Composition

- Define the biomass reaction representing cellular composition

- Include macromolecules (proteins, RNA, DNA, lipids, carbohydrates)

- Incorporate building blocks at physiological ratios [17]

- Use organism-specific composition data when available

Stage 3: Model Conversion and Validation

Step 3.1: Constraint Definition

- Define uptake and secretion constraints for extracellular metabolites

- Set ATP maintenance requirements (ATPM)

- Incorporate enzyme capacity constraints if data available

Step 3.2: Validation with Experimental Data

- Test model predictions against experimental growth phenotypes

- Validate gene essentiality predictions against knockout studies

- Compare predicted nutrient utilization with experimental observations

- Test auxotrophy predictions against growth requirement data

Step 3.3: Debugging and Iteration

- Identify and correct false positive/negative growth predictions

- Refine gene-protein-reaction relationships

- Update biomass composition based on experimental measurements

Protocol: Metabolic Network Reconstruction from Metagenomic Data

Reconstructing metabolic networks from metagenomic data enables modeling of uncultured microorganisms in complex communities, such as those found in anaerobic digesters or host-associated environments [10] [20].

Stage 1: Metagenomic Binning and Genome Resolution

Step 1.1: Sequence Assembly and Binning

- Perform hybrid assembly of Illumina short-reads and Nanopore long-reads [20]

- Use multiple assemblers (SPAdes, OPERA-MS, Unicycler) and merge assemblies

- Bin contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) using Metabat2 and MaxBin2

- Assess MAG quality (completeness, contamination) with CheckM

Step 1.2: Metabolic Potential Annotation

- Annotate metabolic genes in MAGs using KEGG, MetaCyc, or RAST

- Identify key metabolic pathways (e.g., Wood-Ljungdahl pathway for methanogens) [20]

- Determine potential metabolic interactions (hydrogen, formate exchange)

Table 2: Key Metrics for Metagenome-Assembled Genomes in Metabolic Reconstruction

| Metric | Target Value | Assessment Tool | Importance for Model Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completeness | >90% | CheckM | Determines coverage of metabolic network |

| Contamination | <5% | CheckM | Reduces false positive reactions |

| Strain Heterogeneity | <10% | CheckM | Ensures model represents single population |

| N50 | >10 kbp | QUAST | Indicates contiguity of genetic information |

| Protein Coding Density | 80-95% | Prodigal | Validates coding potential |

Stage 2: Community Metabolic Model Construction

Step 2.1: Individual Genome-Scale Model Reconstruction

- Build draft models for each high-quality MAG using automated tools (CarveMe, ModelSEED) [20]

- Manually curate key pathways based on metabolic literature

- Add transport reactions for metabolic exchanges

Step 2.2: Community Model Integration

- Combine individual models into community metabolic model

- Define shared extracellular environment and nutrient constraints

- Add metabolic exchange reactions between community members

Step 2.3: Simulation of Metabolic Interactions

- Use FBA with appropriate objective functions for community growth

- Analyze metabolic cross-feeding through flux variability analysis

- Identify syntrophic relationships (e.g., hydrogen transfer) [20]

Stage 3: Validation with Environmental Data

Step 3.1: Integration with Environmental Parameters

- Constrain model with measured environmental conditions (pH, temperature, substrate availability)

- Incorporate gas partial pressure data for methanogenic communities [20]

Step 3.2: Comparison with Metatranscriptomic Data

- Validate active pathways using metatranscriptomic data

- Constrain reaction fluxes based on gene expression levels

- Identify discrepancies between potential and actual metabolic functions

Flux Balance Analysis Applications for Microbial Communities

Simulating Metabolic Interactions

FBA of community models enables prediction of metabolic interactions and resource competition [10]. For example, in anaerobic methanation communities, FBA revealed syntrophic relationships based on hydrogen and carbon dioxide uptake, with formate and amino acid exchanges [20]. The multi-step FBA formulation can simulate dynamic metabolic switches, such as when microbes transition between primary and secondary substrates [21].

Advanced FBA Techniques

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA)

- Identifies alternate optimal solutions in metabolic networks

- Determines minimum and maximum possible flux through each reaction

- Reveals metabolic flexibility and redundant pathways [17]

Dynamic FBA

- Extends FBA to dynamic conditions by incorporating metabolite concentrations over time

- Uses a cybernetic approach to model metabolic switches [21]

- Can be coupled with reactive transport models for spatial simulations [21]

Machine Learning Integration

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) can serve as surrogate FBA models [21]

- Reduces computational time for dynamic and spatial simulations

- Enables efficient coupling with reactive transport models [21]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Resources for Metabolic Network Reconstruction and Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Databases | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Annotation | RAST, KEGG, BioCyc, NCBI Entrez Gene | Functional annotation of metabolic genes |

| Biochemical Databases | BRENDA, Transport DB, PubChem | Reaction kinetics, metabolite properties |

| Reconstruction Software | ModelSEED, CarveMe, AuReMe | Automated draft model generation |

| FBA Simulation | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB), COBRApy (Python), CellNetAnalyzer | Constraint-based modeling and analysis |

| Network Analysis | OptFlux, FASIMU, Escher | Visualization and flux simulation |

| Quality Assessment | MEMOTE, CheckM | Model and MAG quality evaluation |

| Community Modeling | MICOM, SMETANA, MMinte | Multi-species metabolic modeling |

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Common Reconstruction Issues

Network Gaps and Disconnected Components

- Symptoms: Metabolites cannot carry flux, inability to produce biomass precursors

- Solutions: Add missing transport reactions, verify cofactor balances, check reaction directionality

Incorrect Growth Predictions

- Symptoms: False positive/negative growth predictions

- Solutions: Verify biomass composition, check energy maintenance requirements, validate gene essentiality

Numerical Instability in FBA

- Symptoms: Inconsistent solutions, solver errors

- Solutions: Check for stoichiometric consistency, remove energy generating cycles, verify constraint bounds

Quality Assurance Metrics

- Stoichiometric consistency: All metabolites should be mass- and charge-balanced

- Network connectivity: All biomass precursors should be producible from defined nutrients

- Gene essentiality: Model should recapitulate known essential genes with >80% accuracy

- Growth prediction: Model should match experimental growth phenotypes on different substrates

Metabolic network reconstruction from genomic and metagenomic data provides a powerful framework for investigating the metabolic capabilities of individual microorganisms and complex communities. The protocols outlined here enable researchers to build high-quality, predictive models that can simulate metabolic fluxes using Flux Balance Analysis. For microbial communities, these approaches reveal syntrophic relationships and metabolic cross-feeding that underlie community function and stability. As reconstruction methods continue to advance through automation and machine learning integration, these models will play an increasingly important role in microbial ecology, biotechnology, and understanding host-microbe interactions.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) serves as a cornerstone computational method for analyzing metabolic networks in microorganisms and microbial communities. This constraint-based approach enables researchers to predict metabolic fluxes, growth rates, and essentiality patterns by leveraging genome-scale metabolic reconstructions [22]. FBA operates on the fundamental principle that metabolic networks rapidly reach steady-state conditions where metabolite production and consumption are balanced [23]. This steady-state assumption, mathematically represented as S∙v = 0 (where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the flux vector), transforms complex kinetic problems into tractable linear programming solutions [24].

The biomass objective function represents a critical component in FBA simulations, quantifying the cellular requirements for growth by specifying the necessary metabolites in appropriate proportions [22]. This function encapsulates the metabolic costs of producing all biomass components—including proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids—thereby enabling predictions of growth rates under various environmental conditions [25]. When modeling microbial communities, these fundamental concepts expand to encompass cross-feeding relationships, resource competition, and emergent community functions [26].

Understanding the interplay between balanced growth assumptions, steady-state constraints, and biomass formulation is particularly crucial for investigating host-microbe interactions and multi-species ecosystems [24]. The accurate representation of these concepts enables researchers to simulate complex metabolic interactions, predict community assembly, and identify key metabolic pathways that influence ecosystem stability and function [26].

The Biomass Objective Function: Formulation and Implementation

Theoretical Foundation and Mathematical Representation

The biomass objective function mathematically represents the metabolic requirements for cellular replication by combining all biomass precursors into a single reaction. In classical FBA, this is implemented by appending coefficients mi of metabolites Mi as a single reaction column to the stoichiometric matrix S [27]:

S' = [S | m] (Equation 1)

where values mi < 0 represent consumption of process reactants, and mi > 0 represent byproduct return [27]. The flux through the biomass reaction (vbio) is typically maximized in FBA simulations and can be interpreted as the microbial growth rate [22]. The subsequent optimization problem becomes:

maximize vbio subject to S'∙v' = 0 and vl ≤ v ≤ vu (Equation 2)

The coefficients mi represent the required amounts of metabolites for a basis amount of cell mass, making the biomass reaction flux vbio represent the fractional fulfillment of that requirement per time [27]. This formulation inherently assumes proportional production of all biomass components.

Hierarchical Formulation Approaches

Table 1: Levels of Biomass Objective Function Formulation

| Formulation Level | Components Included | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Basic | Macromolecular content (proteins, RNA, lipids), metabolic building blocks (amino acids, nucleotides) | Initial model development, high-level growth predictions |

| Intermediate | Biosynthetic energy requirements (ATP, GTP for polymerization), polymerization products (water, diphosphate) | Standard metabolic simulations, gene essentiality predictions |

| Advanced | Vitamins, cofactors, elements; core essential components based on experimental data | Specialized conditions, minimal media, high-precision predictions |

The formulation process begins with defining the macromolecular composition of the cell, including weight fractions of protein, RNA, DNA, lipids, and carbohydrates [22]. Each macromolecular group is further broken down into specific metabolic precursors, enabling detailed calculation of carbon, nitrogen, and additional elemental requirements [22].

At the intermediate level, biosynthetic energy requirements are incorporated, accounting for the ATP and GTP needed for polymerization processes such as protein synthesis (approximately 2 ATP and 2 GTP molecules per amino acid) [22]. This level also includes the polymerization byproducts (water from protein synthesis, diphosphate from nucleic acid synthesis) that become available to the cell [22].

Advanced formulations incorporate vitamins, cofactors, and trace elements, and may implement separate "core" biomass functions representing minimally functional cellular content based on experimental data from knockout strains [22]. This approach improves accuracy when predicting gene, reaction, and metabolite essentiality [22].

Balanced Growth Assumption in Metabolic Models

Conceptual Framework and Implications

The balanced growth assumption in FBA imposes strict proportionality between all biomass reactants through the biomass reaction's fixed stoichiometric coefficients [27]. This assumption encodes population-average balanced growth, implying both homogeneity between cells and temporal homogeneity within individual cells [27]. Mathematically, this constraint forces identical fractional fulfillment of all metabolite requirements for growth, scaling production to the most limited reactant [27].

This balanced growth formulation makes several biologically significant assumptions. First, it presupposes regulatory enforcement of metabolite production ratios, despite transcriptional and translational mechanisms operating on timescales longer than typical FBA time steps (1 second to several minutes) [27]. Second, it treats all metabolites included in the biomass reaction as essential for replication, potentially leading to false essentiality predictions if non-essential components are included [27]. Experimental evidence increasingly challenges these assumptions, with observations confirming that essential metabolites can be produced in non-wild-type proportions under various conditions [27].

Methodological Extensions: flexFBA

The flexFBA approach addresses limitations of the rigid biomass reaction by introducing reactant flexibility [27]. This method removes the fixed proportionality between reactants by appending their coefficients as separate reactions to the stoichiometric matrix:

S̃ = [S | -diag(m₁,...,mn) | diag(m{n+1},...,m{n+n})] (Equation 3)

where the fluxes fi now represent independent fractional fulfillments of metabolite requirements [27]. flexFBA employs a modified optimization objective:

maximize fatp - γ∑i|fatp - f_i| (Equation 4)

This formulation maximizes ATP production while penalizing metabolites produced less than proportionally to ATP, using an ℓ1-norm penalty to encourage sparsity in deviation terms [27]. The weighting constant γ determines the penalty strength for non-proportional production [27].

Diagram 1: Conceptual comparison between classical FBA and flexFBA approaches to balanced growth

Steady-State Assumption: Foundations and Applications

Mathematical Framework and Physiological Basis

The steady-state assumption represents a cornerstone of constraint-based modeling, asserting that internal metabolite concentrations remain constant over time despite ongoing metabolic fluxes [23]. Mathematically, this is represented as d[Metabolite]/dt = 0, implying that production and consumption fluxes for each metabolite are perfectly balanced [23]. This assumption is physiologically justified by the observation that metabolic processes typically operate on much faster timescales than regulatory or growth processes [23].

The steady-state assumption enables the application of linear programming to otherwise intractable metabolic systems by transforming the problem into finding flux distributions that satisfy S∙v = 0 within specified bounds [24]. This formulation has proven remarkably successful despite not requiring the quasi-steady-state approximation associated with Michaelis-Menten kinetics [23].

Recent mathematical frameworks have demonstrated that the steady-state assumption applies not only to constant systems but also to oscillating and growing systems without requiring quasi-steady-state at any specific time point [23]. However, these frameworks also reveal that average metabolite concentrations may not always align with average fluxes, highlighting unintuitive effects when integrating nonlinear constraints into steady-state models [23].

Dynamic Extensions: tFBA and Hybrid Approaches

The time-linked FBA (tFBA) approach addresses limitations of the classical steady-state assumption by relaxing the fixed proportionality between reactants and byproducts [27]. This method enables description of transitions between metabolic steady states, making it particularly valuable for modeling dynamic processes in microbial communities and host-microbe interactions [27].

When combining flexFBA and tFBA, researchers can model timescales shorter than the regulatory and growth steady states encoded by traditional biomass reactions [27]. This short-time FBA method is especially valuable for integrated modeling applications such as whole-cell models, where it avoids artifacts caused by low-copy-number enzymes in single-cell models with kinetic bounds [27].

More recently, machine learning approaches have been developed to couple FBA with reactive transport models, creating surrogate models that maintain the steady-state assumption while dramatically improving computational efficiency [21]. These approaches use artificial neural networks trained on FBA solutions to predict exchange fluxes, enabling rapid simulation of metabolic switching in dynamic environments [21].

Table 2: Steady-State Implementation Across FBA Variants

| Method | Steady-State Formulation | Applications | Computational Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical FBA | S∙v = 0 for all metabolites | Single condition analysis, Gene essentiality | Linear programming, Efficient |

| flexFBA | S∙v = 0 with flexible biomass components | Unbalanced growth conditions, Stress responses | Linear programming with additional variables |

| tFBA | Sequential steady states with metabolic memory | Dynamic environments, Diauxic shifts | Multiple LP solutions, Moderate cost |

| ANN-surrogate FBA | S∙v = 0 embedded in neural network | Multi-scale modeling, Reactive transport | High initial training, Very fast execution |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Model Reconstruction and Integration for Microbial Communities

Purpose: To reconstruct and integrate genome-scale metabolic models for host-microbe interaction studies [24].

Materials:

- Genomic data (host and microbial sequences)

- Metabolic reconstruction tools (ModelSEED, CarveMe, RAVEN, gapseq)

- Standardization resources (MetaNetX namespace)

- Linear programming solvers (GLPK, Gurobi, CPLEX)

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Obtain genome sequences for host and microbial species of interest. For complex communities, use metagenome-assembled genomes [24].

- Draft Reconstruction: Generate individual metabolic models using automated pipelines (ModelSEED, CarveMe) or retrieve pre-curated models from databases (AGORA, BiGG) [24].

- Host Model Refinement: Manually curate host metabolic models to account for compartmentalization (mitochondria, peroxisomes) and cell-type specific metabolism [24].

- Model Integration: Harmonize nomenclatures across models using MetaNetX and merge into unified framework [24].

- Quality Control: Detect and remove thermodynamically infeasible reaction cycles introduced during model merging [24].

- Constraint Definition: Define nutritional environment (medium composition) and additional constraints based on experimental data [24].

Validation: Compare predicted growth rates, substrate utilization, and byproduct secretion with experimental measurements. Validate gene essentiality predictions using knockout studies [24].

Protocol 2: Dynamic Multi-Substrate Growth Simulation

Purpose: To simulate microbial metabolic switching between multiple carbon sources using surrogate FBA models [21].

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iMR799 for S. oneidensis)

- Random sampling framework for parameter space exploration

- Artificial neural network training environment (Python, TensorFlow, PyTorch)

- Reactive transport modeling platform

Procedure:

- Solution Space Characterization: Perform multi-step FBA with appropriate parameters (e.g., ATP stoichiometry in biomass, fractional byproduct production) [21].

- Data Generation: Randomly sample environmental conditions (substrate and oxygen availability) and compute corresponding FBA solutions for exchange fluxes [21].

- ANN Training: Develop multi-input multi-output (MIMO) artificial neural networks using generated FBA solutions as training data [21].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Determine optimal network architecture (nodes, layers) through grid search and cross-validation [21].

- Model Integration: Incorporate trained ANN as algebraic equations into reactive transport models as source/sink terms [21].

- Dynamic Simulation: Implement cybernetic approach to model metabolic switches as outcome of competition among growth options [21].

Validation: Compare ANN predictions with original FBA solutions across parameter space. Verify metabolic switching patterns against experimental observations of sequential substrate utilization [21].

Diagram 2: Workflow for metabolic model reconstruction and integration in host-microbe studies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for FBA Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Databases | AGORA, BiGG, APOLLO | Provide curated metabolic models for diverse organisms | Model retrieval, Comparative analysis |

| Reconstruction Tools | ModelSEED, CarveMe, RAVEN, merlin | Automated draft model generation from genomic data | High-throughput model building |

| Standardization Resources | MetaNetX | Namespace harmonization across models | Multi-species model integration |

| Simulation Environments | COBRA Toolbox, SMETOOLS | FBA implementation and analysis | Metabolic flux prediction |

| Linear Programming Solvers | GLPK, Gurobi, CPLEX | Solve linear optimization problems in FBA | Core computational engine |

| Experimental Validation | ¹³C metabolic flux analysis, Knockout strains | Validate model predictions experimentally | Method confirmation |

Application Notes for Microbial Community Modeling

Technical Considerations in Community Modeling

When applying balanced growth, steady-state, and biomass concepts to microbial communities, several technical aspects require careful consideration. Assumptions about decision-making principles and environmental conditions significantly impact simulation outcomes, potentially yielding multiple steady states with qualitatively different predictions [26]. Different assumption combinations can predict varying modes of microbial coexistence, including both substrate competition and cross-feeding relationships [26].

The integration of time-linked approaches with flexible biomass formulations enables more realistic modeling of community dynamics, particularly for systems exhibiting metabolic specialization or division of labor [27]. These approaches are especially valuable when investigating synthetic communities where individual strains exhibit no growth in isolation but achieve growth through cooperative interactions [26].

Challenges and Future Directions

Current challenges in microbial community modeling include standardization of model integration, as models from different sources often use distinct nomenclatures for metabolites, reactions, and genes [24]. Additionally, the detection and removal of thermodynamically infeasible reactions remains crucial when merging models of different origins [24].

Future methodological developments will likely focus on multi-scale integration, combining metabolic models with regulatory networks and spatial considerations [24]. Machine learning approaches, such as the ANN-surrogate models successfully demonstrated for S. oneidensis, offer promising avenues for enhancing computational efficiency while maintaining biological fidelity [21]. These developments will significantly advance our ability to model complex host-microbe ecosystems and predict community responses to environmental perturbations [24].

Computational Frameworks and Techniques for Modeling Community Metabolism

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have emerged as a powerful computational framework for simulating the metabolic capabilities of microorganisms. When analyzing microbial communities, researchers primarily employ three core modeling approaches: compartmentalized, lumped (mixed-bag), and costless secretion [28] [29]. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations for simulating metabolic interactions, cross-feeding, and community dynamics. The selection of an appropriate approach depends on the research question, available data, and the desired level of computational complexity [28] [30]. This article provides a detailed technical overview of these methodologies, their implementation protocols, and applications within flux balance analysis (FBA) of microbial communities.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Modeling Approaches for Microbial Communities

| Approach | Core Concept | Best-Suited Applications | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compartmentalized Model | Merges multiple GEMs into a single stoichiometric matrix with a shared extracellular compartment [28] [30] | Synthetic consortia; communities with well-characterized, dominant species [29] | Maintains species identity and segregation; enables tracking of species-specific contributions [28] | Computationally intensive; requires high-quality models for all members [29] |

| Lumped Model (Mixed-Bag) | Pools all metabolic reactions and metabolites from community members into a single "supra-organism" model [28] [30] | Analysis of overall community metabolic potential; functional profiling from metagenomic data [29] | Computational efficiency; reduced model size; simple simulation [28] | Overestimates community capability; ignores species-species barriers [29] |

| Costless Secretion | Iteratively simulates individual models while updating the shared environment with metabolites secreted without growth cost [30] [31] | Identifying spontaneous cross-feeding opportunities; understanding emergent interactions [31] | Captures environmentally-mediated interactions; identifies metabolites that drive cooperation [31] | Sequential, quasi-dynamic approach; may miss simultaneous interactions [30] |

Compartmentalized Modeling Approach

Conceptual Framework and Workflow

The compartmentalized approach models microbial communities by combining individual GEMs of member species into a unified stoichiometric matrix while maintaining their metabolic autonomy through separate intracellular compartments. These models are connected via a shared extracellular "lumen" compartment that enables metabolite exchange and cross-feeding [28] [30]. This method preserves species-specific biochemical networks while allowing for the simulation of metabolic interactions.

Experimental Protocol

Implementation of Pairwise Community Simulation Using Compartmentalized Modeling

The following seven-step protocol adapts the approach used by Magnúsdóttir et al. in the AGORA framework for studying pairwise microbial interactions [28] [30]:

- Model Selection: Select two genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) for the species of interest from curated databases like AGORA [28].

- Model Integration: Merge the two individual GEMs into a single stoichiometric matrix. Create a shared extracellular compartment (lumen) that connects to both models via exchange reactions [28] [30].

- Environmental Constraints: Constrain the merged model by adjusting exchange reaction bounds to reflect the chosen nutritional environment (diet) and extracellular conditions (e.g., aerobic vs. anaerobic) [28] [30].

- Monoculture Simulation (Control 1): Simulate monoculture conditions for the first species by "shutting off" the second model (set all reaction upper and lower bounds to 0 flux). Calculate the growth rate of the active model using FBA with biomass maximization as the objective [28].

- Monoculture Simulation (Control 2): Repeat step 4 for the second species while shutting off the first model [28].

- Co-culture Simulation: Restore activity to both models in the merged system. Simulate co-culture by optimizing for growth of both organisms, allowing metabolite exchange via the shared lumen compartment [28] [30].

- Interaction Analysis: Compare paired growth in co-culture with individual monoculture growth rates. Classify interaction types: if both models show >10% increased growth, classify as mutualism; if both show >10% decreased growth, classify as competition; for asymmetric effects, classify as parasitism, commensalism, or amensalism accordingly [28].

Applications and Variations: This approach has been successfully applied to study metabolic interactions in gut microbiota [28] and host-microbe interactions [10] [24]. Advanced implementations include multi-objective optimization frameworks like OptCom, which simultaneously optimize individual and community-level objectives [29] [32].

Lumped Modeling Approach

Conceptual Framework and Workflow

The lumped model approach, also known as the "mixed-bag" or "enzyme soup" method, consolidates all metabolic reactions and metabolites from community members into a single unified metabolic network [28] [30]. This supra-organism model eliminates species boundaries, effectively treating the entire community as a single metabolic entity. While this simplification ignores biological compartmentalization, it significantly reduces computational complexity.

Experimental Protocol

Community Metabolic Potential Assessment Using Lumped Modeling

- Model Acquisition or Reconstruction: Obtain GEMs for all community members from databases like AGORA or BiGG [29] [24]. Alternatively, reconstruct models from genomic data using automated pipelines such as CarveMe, gapseq, or ModelSEED [24] [33].

- Model Integration and Standardization: Merge all individual metabolic models into a single stoichiometric matrix. Standardize metabolite and reaction nomenclature across models using resources like MetaNetX to resolve inconsistencies [24].

- Biomass Reaction Configuration: Choose one of two approaches for biomass reactions:

- Constraint Application: Apply environmental constraints based on available nutrients and growth conditions. Set appropriate bounds on exchange reactions to reflect the simulated environment [28].

- Model Simulation and Analysis: Perform flux balance analysis to predict metabolic flux distributions. Use flux variability analysis (FVA) to identify blocked reactions and validate model functionality [28] [30]. Analyze the production of community-level metabolites of interest (e.g., short-chain fatty acids in gut models) [28].

Applications and Considerations: The lumped approach has been effectively used to predict metabolic byproducts from complex dietary sources and to identify minimal microbiomes for specific functions [28] [34]. A significant limitation is the potential overestimation of community metabolic capabilities, as it ignores physical and regulatory barriers between species [29]. Consensus modeling approaches that integrate reconstructions from multiple tools can improve prediction accuracy by reducing tool-specific biases [33].

Costless Secretion Approach

Conceptual Framework and Workflow

The costless secretion approach simulates microbial interactions through an iterative process that identifies metabolites that can be secreted without fitness cost to the producer [30] [31]. These "costless" metabolites (those whose secretion does not reduce growth rate) become available to other community members, driving cross-feeding interactions in a dynamically updated environment.

Experimental Protocol

Iterative Identification of Cross-Feeding Through Costless Metabolites

- Initialization: Begin with a defined base medium containing essential nutrients. Select the microbial species to simulate and their order of introduction [30] [31].

- First Iteration (c = 1): Simulate the first organism using constraint-based modeling (FBA) with growth maximization as the objective on the initial medium [31].

- Costless Secretion Identification: For the simulated organism, identify all metabolites that can be secreted without reducing growth rate compared to non-secretion conditions (vg,s ≥ vg,0). These are designated as costless secretions [31].

- Medium Update: Add the identified costless metabolites to the shared medium by enabling appropriate uptake reactions [30] [31].

- Subsequent Iterations: Introduce the next organism(s) and simulate their growth on the updated medium. Identify their costless secretions and add these to the medium [31].

- Termination Check: Repeat iterations until no new metabolites are secreted or a stable state is reached (cs) where the medium composition no longer changes between iterations [31].

- Interaction Analysis: Analyze the final metabolic environment and growth capabilities to identify potential mutualisms, commensalisms, and other interaction types mediated by costless metabolite exchange [31].

Applications and Insights: This approach has revealed that anoxic conditions promote more cooperative interactions by increasing opportunities for costless metabolite exchange [30] [31]. Studies have shown that costless secretions include various metabolites such as organic acids, nitrogen-containing compounds, and fermentation byproducts, creating ample opportunities for cross-feeding without invoking evolutionary dilemmas associated with costly cooperation [31].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Community Metabolic Modeling

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Database | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Model Databases | AGORA [28] [24] | Curated GEM collection for human gut microbiota |

| BiGG Models [29] [24] | Database of curated genome-scale metabolic models | |

| Reconstruction Tools | CarveMe [24] [33] | Automated GEM reconstruction using a universal template |

| ModelSEED [29] [24] | Rapid draft model reconstruction from genomic data | |

| gapseq [24] [33] | Comprehensive metabolic reconstruction from genomes | |

| Simulation Environments | COBRA Toolbox [28] [30] | MATLAB toolbox for constraint-based metabolic analysis |

| KBase [33] | Integrated platform for microbial community analysis | |

| Analysis Techniques | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [28] [29] | Predicts metabolic fluxes by optimizing biomass production |

| Flux Sampling [28] [30] | Generates range of possible fluxes without objective function | |