Ensuring Diagnostic Precision: A Comprehensive Guide to Accuracy Testing Protocols for Qualitative Microbiological Assays

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed framework for planning, executing, and troubleshooting accuracy testing for qualitative microbiological assays.

Ensuring Diagnostic Precision: A Comprehensive Guide to Accuracy Testing Protocols for Qualitative Microbiological Assays

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed framework for planning, executing, and troubleshooting accuracy testing for qualitative microbiological assays. Aligned with international standards like ISO 16140 and CLSI guidelines, it covers foundational principles, methodological protocols for FDA-cleared and laboratory-developed tests, strategies for resolving discrepant results, and validation requirements for alternative methods. The guidance supports robust assay implementation, regulatory compliance, and reliable diagnostic outcomes in clinical and pharmaceutical settings.

Foundations of Accuracy: Core Principles and Regulatory Standards for Qualitative Assays

In microbiological analysis, the distinction between qualitative and quantitative methods is fundamental. Qualitative microbiological testing is designed to detect, observe, or describe the presence or absence of a specific quality or characteristic, such as a particular microorganism, in a given sample [1]. Unlike quantitative methods that measure numerical values, qualitative assays answer the question "Is it there?" rather than "How much is there?" [1]. These methods are typically characterized by their high sensitivity, with a theoretical limit of detection (LOD) equivalent to 1 Colony Forming Unit (CFU) per test portion, even when test portions are as large as 25 g to 375 g or more [1].

Defining accuracy within this context presents unique challenges. In the absence of a certified ground-truth reference material for microbial cell count, quantifying the absolute accuracy of a counting method becomes limited [2]. Consequently, method performance assessments and comparisons must rely on a suite of key performance metrics that, together, build a profile of a method's reliability. These metrics—including diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, precision, robustness, and ruggedness—provide a framework for validating qualitative methods, ensuring they are fit-for-purpose in critical applications ranging from pharmaceutical drug development to food safety diagnostics [1].

Key Performance Metrics for Qualitative Assays

The validation of a qualitative microbiological method involves characterizing its performance against a panel of defined metrics. The following table summarizes the core metrics essential for defining accuracy in this context.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Qualitative Microbiological Assays

| Metric | Definition | Experimental Goal | Acceptance Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Sensitivity | The probability of the method correctly identifying a true positive sample (e.g., contaminated with the target microbe) [1]. | Maximize the number of true positives detected. | Ideally 100%; lower confidence limit should meet required performance. |

| Diagnostic Specificity | The probability of the method correctly identifying a true negative sample (e.g., not contaminated with the target microbe) [1]. | Minimize the number of false positives. | Ideally 100%; lower confidence limit should meet required performance. |

| Precision (Repeatability & Reproducibility) | The closeness of agreement between independent results obtained under stipulated conditions [2]. | Demonstrate consistent results across replicates, days, analysts, and laboratories. | 100% agreement or statistically significant consistency. |

| Robustness | The capacity of the method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | Identify critical operational parameters that require control. | The method continues to meet pre-defined sensitivity/specificity. |

| Ruggedness | The degree of reproducibility of results under a variety of normal, practical conditions (e.g., different instruments, operators). | Demonstrate method reliability in real-world lab environments. | Consistent performance across all defined variables. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest number of target organisms that can be detected in a defined sample size [1]. | Confirm the method can detect very low populations (e.g., 1 CFU/test portion). | Consistent detection at the target level (e.g., 1 CFU/25g). |

These metrics are interdependent. A comprehensive accuracy testing protocol does not view them in isolation but seeks to understand how they collectively ensure the method's reliability for its intended use.

Experimental Protocols for Metric Validation

Protocol for Determining Diagnostic Sensitivity and Specificity

This protocol outlines the procedure for establishing the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of a qualitative microbiological method, such as a PCR assay or cultural method for a pathogen like Salmonella.

1. Principle: The method's performance is evaluated by testing a panel of characterized samples with known status (positive or negative for the target organism). Results from the test method are compared to the known status to calculate sensitivity and specificity [1].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Target Microorganism: Certified reference strain(s) of the target organism (e.g., Listeria monocytogenes).

- Non-Target Microorganisms: A panel of closely related and common non-target strains to challenge specificity.

- Test Samples: A sufficient number of representative sample matrices (e.g., food homogenate, environmental swab eluent) for artificial contamination.

- Culture Media: All enrichment broths, selective agars, and other media as required by the test method.

- Control Materials: Positive and negative control materials as defined by the method.

3. Procedure: 1. Panel Preparation: Prepare a blinded panel of samples. * Positive Panel: Artificially inoculate a portion of samples with low levels (targeting ~1-5 CFU per test portion) of the target microorganism. * Negative Panel: Another portion remains uninoculated. * Specificity Challenge Panel: Inoculate some samples with non-target microorganisms. 2. Testing: Analyze the entire panel using the qualitative test method under validation according to its standard operating procedure. This includes any required enrichment amplification step [1]. 3. Reference Analysis: All samples are analyzed in parallel using a reference cultural method, which is considered the definitive test for determining the sample's true status. 4. Data Collection: Record all results as Positive, Negative, or Presumptive Positive as per the method's guidelines.

4. Data Analysis:

- Construct a 2x2 contingency table comparing the test method results to the reference method results.

- Diagnostic Sensitivity (%) = [True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives)] x 100

- Diagnostic Specificity (%) = [True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives)] x 100

- Calculate the 95% confidence intervals for both sensitivity and specificity.

Protocol for Determining Precision (Repeatability)

This protocol assesses the internal consistency of the qualitative method by testing under repeatable conditions.

1. Principle: The same homogeneous, artificially contaminated sample is analyzed multiple times (e.g., n=5-20) within the same laboratory, using the same equipment, analyst, and short interval of time. The goal is to measure the method's inherent variability [2].

2. Procedure: 1. Prepare a single large batch of sample material and inoculate it with the target organism at a level near the LOD (e.g., a level that yields 95-99% positive results). 2. Subdivide this material into multiple identical test portions. 3. A single analyst tests all portions in one session or over multiple sessions on the same day, following the identical protocol. 4. Record the result (Positive/Negative) for each replicate.

3. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage agreement between all replicates.

- The expected agreement for repeatability should be 100%. Any deviation should be investigated, as it indicates significant inherent variability in the method at the defined contamination level.

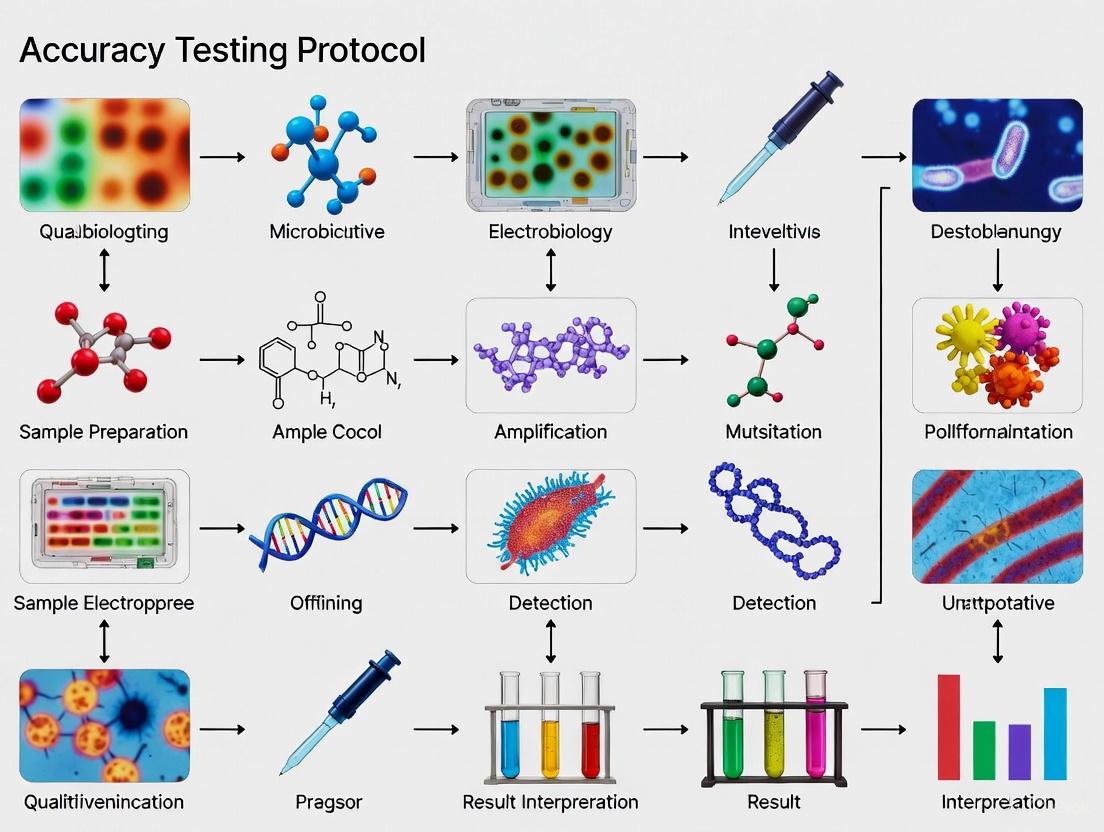

Diagram 1: Qualitative method validation workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The reliability of qualitative microbiological assays is heavily dependent on the quality and consistency of the reagents used. The following table details essential materials and their functions in the context of assay development and validation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Qualitative Microbiology

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance in Qualitative Testing |

|---|---|

| Certified Microbial Reference Strains | Provide a traceable, characterized source of the target microorganism essential for preparing positive controls, determining sensitivity, and challenging specificity. |

| Selective and Differential Culture Media | Used in cultural methods to isolate the target organism from a mixed microbiota by inhibiting non-targets and displaying a recognizable colonial phenotype [1]. |

| Enrichment Broths | Liquid media designed to amplify the low numbers of the target microorganism to a detectable level, a critical amplification step in most qualitative methods [1]. |

| Antibodies & Antigens (for Immunoassays) | Key reagents for rapid screening methods (e.g., ELISAs, lateral flow devices) that detect cell-surface antigens for identification. |

| Primers and Probes (for Molecular Assays) | Short, specific DNA or RNA sequences designed to bind to the target organism's unique genetic signature, enabling detection via PCR or isothermal amplification. |

| Sample Diluents and Transport Media | Maintain the viability and integrity of microorganisms from the time of sample collection to the initiation of testing, preventing false negatives. |

A Framework for Assessing Method Accuracy

The concept of accuracy in qualitative microbiology transcends a single number. It is best defined as the closeness of agreement between a test result and the accepted reference value, which is built upon the foundation of the performance metrics described in this document [2]. A method's fitness-for-purpose is demonstrated through the cumulative evidence provided by its high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, its precision, and its robustness under variable conditions.

The experimental protocols and metrics outlined here provide a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design rigorous validation studies. By systematically collecting data on these key performance indicators, scientists can generate the evidence base needed to confidently select, optimize, and deploy qualitative microbiological assays that ensure product safety and public health.

Diagram 2: The pillars of qualitative method accuracy.

In regulated laboratory environments, particularly within pharmaceutical development and qualitative microbiological assay research, the concepts of method validation and method verification represent two distinct but complementary processes essential for ensuring data integrity and regulatory compliance. Both processes confirm that an analytical method is suitable for its intended purpose, but they serve different roles within the method lifecycle and are applied under different circumstances [3]. Understanding the distinction is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who must make strategic decisions about method implementation while maintaining scientific rigor and meeting regulatory obligations.

Method validation is a comprehensive, documented process that proves an analytical method is acceptable for its intended use, establishing its performance characteristics and limitations through rigorous experimentation [3]. It is typically required when developing new methods, significantly modifying existing methods, or transferring methods between laboratories or instruments. Method verification, in contrast, is a confirmation process that a previously validated method performs as expected in a specific laboratory setting, with its specific analysts, equipment, and reagents [3] [4]. For qualitative microbiological assays, which provide binary results such as "detected" or "not detected," these processes require special consideration of factors like matrix effects, inclusivity, and exclusivity that differ from quantitative analytical procedures.

The fundamental distinction lies in the purpose and scope: validation creates the evidence that a method works in principle, while verification confirms that it works in a particular practice. This distinction is crucial in the context of a broader thesis on accuracy testing protocols for qualitative microbiological assays, as the choice between validation and verification directly impacts study design, resource allocation, regulatory strategy, and ultimately, the reliability of the data generated for drug development decisions.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

Method Validation: Establishing Fitness for Purpose

Method validation provides objective evidence that a method consistently meets the requirements for its intended analytical application [3]. According to regulatory guidelines from organizations such as the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), United States Pharmacopeia (USP), and Food and Drug Administration (FDA), validation is a comprehensive exercise involving systematic testing and statistical evaluation of multiple performance parameters [3]. For qualitative microbiological assays, the validation process must demonstrate that the method reliably detects the target microorganism(s) when present and does not produce false positives when absent.

The key performance characteristics assessed during validation of qualitative microbiological methods include:

- Accuracy: The agreement between the test result and the true value, often demonstrated through method comparison studies [4].

- Precision: The degree of agreement among individual test results when the procedure is applied repeatedly to multiple samplings, including within-run, between-run, and operator variance [4].

- Specificity: The ability to detect the target analyte in the presence of other components, including closely related microorganisms that might be present in the sample matrix.

- Detection Limit: The lowest amount of the target microorganism that can be reliably detected [3].

- Robustness: The capacity of the method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters, demonstrating reliability during normal usage [3].

- Range: The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of the target microorganism for which the method has suitable levels of precision, accuracy, and linearity.

For microbiological assays, the unique biological aspects introduce additional considerations not typically encountered in chemical analysis. The viability of microorganisms, their physiological state, the complexity of food or clinical matrices, and the potential for interaction between different microbial populations must all be addressed during validation [5].

Method Verification: Confirming Performance in a Specific Setting

Method verification confirms that a previously validated method performs as expected when implemented in a particular laboratory [3]. It is typically employed when adopting standard methods (e.g., compendial methods from USP, ISO, or AOAC) in a new laboratory context [4]. The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) require verification for non-waived systems before reporting patient results, defining it as a one-time study demonstrating that a test performs in line with previously established performance characteristics when used as intended by the manufacturer [4].

The verification process for qualitative microbiological assays focuses on confirming critical performance parameters under the laboratory's actual operating conditions. According to CLIA standards, laboratories must verify the following characteristics for unmodified FDA-approved tests [4]:

- Accuracy: Confirming acceptable agreement of results between the new method and a comparative method.

- Precision: Confirming acceptable within-run, between-run, and operator variance.

- Reportable Range: Confirming the acceptable upper and lower limits of the test system.

- Reference Range: Confirming the normal result for the tested patient population.

Verification is generally less exhaustive than validation but remains essential for quality assurance. It demonstrates that a laboratory can successfully perform a method that has already been proven fit-for-purpose elsewhere, accounting for laboratory-specific factors such as analyst training, equipment calibration, environmental conditions, and sample matrices [3].

Comparative Analysis: Validation vs. Verification

Objective Comparison and Decision Framework

The choice between method validation and method verification depends on the laboratory's specific circumstances, including the method's origin, novelty, and regulatory context. The following decision pathway provides a systematic approach for determining the appropriate process:

Figure 1: Decision Pathway for Method Validation versus Verification

Comparative Parameter Analysis

The table below summarizes the key differences between method validation and method verification across critical parameters relevant to qualitative microbiological assays:

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Method Validation versus Verification

| Parameter | Method Validation | Method Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Establish that a method is fit for its intended use [3] | Confirm that a validated method performs as expected in a specific lab [3] |

| When Performed | During method development, transfer, or significant modification [3] | When implementing a previously validated method in a new setting [4] |

| Scope | Comprehensive assessment of all performance characteristics [3] | Limited assessment focusing on critical parameters [3] |

| Regulatory Basis | Required for new drug applications, novel assays [3] | Required for standardized methods in established workflows [3] |

| Resource Intensity | High (time, personnel, materials) [3] | Moderate to low [3] |

| Duration | Weeks to months [3] | Days to weeks [3] |

| Typical Parameters Evaluated | Accuracy, precision, specificity, LOD, LOQ, linearity, range, robustness [3] | Accuracy, precision, reportable range, reference range [4] |

| Output | Complete performance characterization and documentation [3] | Confirmation that established performance is achieved in the user lab [4] |

For qualitative microbiological assays, both processes must address the unique challenges of working with biological systems. The Poisson distribution becomes relevant at low microbial concentrations, making simple linear averaging inappropriate and requiring specialized statistical approaches [5]. Additionally, factors such as media suitability, incubation conditions, and sample matrix effects require careful consideration during both validation and verification [5].

Application Notes and Protocols

Comprehensive Method Validation Protocol for Qualitative Microbiological Assays

This protocol provides a detailed framework for validating qualitative microbiological methods, consistent with ISO 16140 standards for the food chain [6] and CLSI guidelines for clinical microbiology [4].

Pre-Validation Requirements

Before initiating validation studies, complete these foundational activities:

- Define Intended Use: Clearly document the method's purpose, target microorganisms, sample matrices, and required performance specifications.

- Develop Standard Operating Procedure (SOP): Create a detailed, step-by-step protocol for the method, including all reagents, equipment, and steps.

- Qualify Equipment and Reagents: Ensure all instruments are properly calibrated and maintained, and that all culture media and reagents meet quality specifications.

Experimental Design for Validation Parameters

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Validating Qualitative Microbiological Assays

| Validation Parameter | Experimental Design | Acceptance Criteria | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Test a minimum of 20 positive and 20 negative samples comparing new method to reference method [4] | ≥90% agreement with reference method | Use clinically relevant isolates and appropriate sample matrices |

| Precision | Test 2 positive and 2 negative samples in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators [4] | 100% agreement for positive/negative calls across all replicates | Include different sample matrices if applicable |

| Specificity (Inclusivity) | Test a panel of 50-100 target strains representing genetic diversity | ≥95% detection rate for all target strains | Include recent clinical or environmental isolates relevant to intended use |

| Specificity (Exclusivity) | Test 30-50 non-target strains that may be present in samples | ≤5% false positive rate | Include closely related species and normal flora |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Test serial dilutions of target organisms with 20 replicates at each concentration | Detection of 95% of replicates at the claimed LOD | Use at least 3 different strains of the target microorganism |

| Robustness | Deliberately vary critical parameters (temp, time, reagent lots) | Method performs within specifications despite variations | Identify critical parameters through risk assessment |

Sample Preparation and Storage

For qualitative microbiological assays, proper sample preparation is crucial:

- Sample Matrix Considerations: Account for potential interference from sample matrices by testing the method with representative sample types. For food testing, this might include categories such as heat-processed milk and dairy products, raw meats, and ready-to-eat foods [6].

- Inoculation Methods: Use standardized inoculation procedures with appropriate negative controls to distinguish between true positives and contamination.

- Sample Stability: Establish stability under various storage conditions (time, temperature) if samples will not be tested immediately.

Method Verification Protocol for Qualified Microbiological Methods

This protocol outlines the verification process for implementing previously validated qualitative microbiological methods in a new laboratory setting, consistent with ISO 16140-3 for verification in a single laboratory [6] and CLIA requirements [4].

Verification Study Design

The verification process consists of two stages as defined in ISO 16140-3 [6]:

- Implementation Verification: Demonstrate that the user laboratory can perform the method correctly by testing one of the same items evaluated in the validation study.

- Item Verification: Demonstrate that the laboratory is capable of testing challenging items within its scope of accreditation by testing several such items using defined performance characteristics.

Experimental Parameters for Verification

For qualitative microbiological assays, focus verification on these critical parameters:

Table 3: Experimental Protocol for Verifying Qualitative Microbiological Assays

| Verification Parameter | Experimental Design | Acceptance Criteria | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Test minimum 20 isolates with combination of positive and negative samples [4] | Meet manufacturer's stated claims or lab director-defined criteria [4] | Use reference materials, proficiency samples, or de-identified clinical samples |

| Precision | Test minimum 2 positive and 2 negative samples in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators [4] | 100% agreement for categorical results | If system is fully automated, operator variance may not be needed [4] |

| Reportable Range | Test minimum 3 known positive samples near cutoff values [4] | Correct detection/non-detection according to established cutoffs | Verify both upper and lower limits of detection if applicable |

| Reference Range | Test minimum 20 isolates representing laboratory's patient population [4] | Expected results for typical samples from patient population | Re-define reference range if manufacturer's range doesn't represent local population |

Data Analysis and Acceptance Criteria

- Statistical Analysis: For qualitative assays, calculate percent agreement between results obtained with the verified method and expected results based on reference method or known samples.

- Establishing Acceptance Criteria: Base acceptance criteria on manufacturer's claims, regulatory requirements, or laboratory-defined criteria approved by the laboratory director.

- Documentation: Maintain comprehensive records of all verification activities, including raw data, analysis, and conclusion regarding method acceptability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of both method validation and verification for qualitative microbiological assays requires specific materials and reagents. The following table details essential components and their functions:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Qualitative Microbiological Assay Validation/Verification

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Strains | Positive controls for target organisms | Obtain from recognized collections (ATCC, NCTC); include genetic diversity |

| Exclusivity Panel | Specificity testing against non-target organisms | Include closely related species and normal flora from sample matrix |

| Culture Media | Microbial growth and differentiation | Validate each lot for growth promotion; check pH, osmolality [5] |

| Sample Matrices | Assess method performance in real-world conditions | Include representative samples from all intended categories [6] |

| Molecular Reagents | DNA extraction, amplification, and detection | Use consistent lots throughout validation; verify purity and concentration |

| Quality Controls | Monitor assay performance | Include positive, negative, and internal controls for each run |

Regulatory Framework and Compliance Considerations

International Standards and Guidelines

The validation and verification of microbiological methods occur within a well-defined regulatory landscape characterized by several key standards:

- ISO 16140 Series: Provides a comprehensive framework for validation and verification of microbiological methods in the food chain, with specific parts addressing protocol for validation of alternative methods (Part 2), verification in a single laboratory (Part 3), and validation in a single laboratory (Part 4) [6].

- Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA): Mandates verification studies for non-waived testing systems in clinical laboratories before reporting patient results [4].

- USP Chapters: Compendial methods such as <61> Microbial Enumeration Tests provide standardized approaches with defined validation procedures [7].

- EPA Guidelines: Requires validation and peer review of all analytical methods before issuance [8].

The regulatory requirements differ significantly between validation and verification. Method validation is typically required for new drug applications, clinical trials, and novel assay development, while verification is acceptable for standard methods in established workflows [3].

Documentation and Quality Assurance

Regardless of whether performing validation or verification, comprehensive documentation is essential for regulatory compliance and technical review. Documentation should include:

- Protocol: Detailed experimental design with predefined acceptance criteria.

- Raw Data: Complete records of all experiments, including any deviations from the protocol.

- Final Report: Summary of results, statistical analysis, and conclusion regarding method suitability.

- Quality Control Plan: Ongoing monitoring procedures to ensure continued method performance.

For laboratories seeking accreditation under standards such as ISO/IEC 17025, method verification is generally required to demonstrate that standardized methods function correctly under local laboratory conditions [3].

The distinction between method validation and method verification is fundamental to establishing and maintaining reliable qualitative microbiological assays in research and drug development. Validation comprehensively establishes that a method is fit for its intended purpose, while verification confirms that a previously validated method performs as expected in a specific laboratory environment. Understanding when each process applies—and implementing the appropriate structured protocols—ensures scientific rigor, regulatory compliance, and the generation of reliable data for critical decisions in pharmaceutical development and public health protection.

As microbiological technologies continue to advance with techniques including PCR, next-generation sequencing, and biosensors becoming more prevalent [9], the principles of proper validation and verification remain constant. By applying the frameworks and protocols outlined in this document, researchers and laboratory professionals can confidently implement qualitative microbiological methods that produce accurate, reproducible results, thereby supporting drug development processes and ultimately protecting public health.

For researchers and scientists developing qualitative microbiological assays, navigating the interplay of international standards and regulations is crucial for ensuring patient safety, data integrity, and market access. The current diagnostic and research environment is defined by three key frameworks: ISO 15189, which specifies requirements for quality and competence in medical laboratories; the In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR), which governs devices in the European Union; and the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), which regulate laboratory testing in the United States [10] [11] [12]. With the full implementation of the updated ISO 15189:2022 required by December 2025 and the progressive application of IVDR, laboratories must understand how these requirements impact the development and validation of qualitative assays, such as those for detecting microbial pathogens [13] [14]. This document outlines the core requirements of these frameworks and provides detailed protocols for compliance within the context of microbiological assay research.

Core Regulatory Framework Requirements

ISO 15189: Quality and Competence for Medical Laboratories

ISO 15189 is an international standard specifically tailored for medical laboratories, outlining requirements for quality management and technical competence [10] [15]. The 2022 revision introduced significant updates, emphasizing risk management and integrating point-of-care testing (POCT) requirements previously covered by ISO 22870:2016 [13] [15].

Key Requirements for Microbiological Assay Development:

- Personnel Competence: Staff must be qualified, trained, and regularly assessed for competence in assigned tasks, including specific microbiological techniques [15].

- Examination Procedures: All laboratory examination methods must be verified or validated for their intended use, with specific parameters for qualitative assays [15] [16].

- Quality Assurance: Laboratories must implement both internal quality control and external quality assessment schemes to monitor performance and result accuracy [15].

- Sample Handling: Documented procedures are required for sample collection, transportation, storage, acceptance, and rejection, critical for microbiological specimen integrity [15].

IVDR: In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation

The IVDR established a new regulatory framework for in vitro diagnostic devices in the European Union, with major consequences for both commercially available CE-IVDs and in-house devices (IH-IVDs), also known as laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) [11]. The regulation introduces a risk-based classification system and stricter requirements for clinical evidence and post-market surveillance [11] [14].

Critical Timelines for Compliance:

- May 2022: Compliance with General Safety and Performance Requirements began [14].

- May 2024: Implementation of appropriate Quality Management Systems (e.g., ISO 15189) required [14].

- May 2028: Justification for using in-house devices over commercially available tests mandated [14].

CLIA: Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments

CLIA are U.S. federal regulatory standards that apply to any facility performing laboratory testing on human specimens for health assessment, diagnosis, prevention, or treatment of disease [12]. CLIA regulations focus on quality assurance throughout the entire testing process.

Essential CLIA Components for Assay Validation:

- Method Verification: Required for all new tests, instruments, or relocations before reporting patient results [12].

- Staff Competency: Must be assessed semiannually during the first year of employment and annually thereafter [12].

- Quality Assurance: An ongoing, comprehensive program analyzing pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical processes [12].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Regulatory Frameworks

| Requirement | ISO 15189:2022 | IVDR | CLIA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Quality & competence of medical laboratories | Safety & performance of IVD devices | Quality assurance across testing process |

| Geographic Application | International | European Union | United States |

| Risk Management | Explicit requirement with reference to ISO 22367 [10] | Integrated into classification system & GSPRs [11] | Implied through quality control requirements |

| Personnel Requirements | Competence requirements for all personnel [15] | Not directly specified for health institutions | Specific competency assessments mandated [12] |

| Validation/Verification | Examination procedures must be verified/validated [15] | Required for in-house devices per Annex I GSPRs [14] | Method verification required for all test systems [12] |

| Quality Management | Comprehensive QMS requirements [10] | Appropriate QMS (e.g., ISO 15189) required for in-house devices [14] | Quality assurance program required [12] |

Interrelationship of Regulatory Frameworks

The relationship between ISO 15189, IVDR, and CLIA creates an integrated ecosystem for quality and compliance. IVDR explicitly recognizes ISO 15189 as an appropriate quality management system for health institutions developing in-house devices [10] [14]. However, compliance with ISO 15189 alone does not constitute a sufficient QMS for the manufacture of in-house IVDs under IVDR, necessitating additional procedures for device development, manufacturing changes, surveillance, and incident reporting [10].

For laboratories operating in both the EU and U.S. markets, understanding the harmonization and differences between these frameworks is essential. While ISO 15189 is widely embraced in the EU and many countries, it is not recognized by the FDA as equivalent to CLIA certification, which remains the obligatory framework in the U.S. [15].

Diagram 1: Regulatory Framework Interrelationships. This diagram illustrates how major regulations interact with and recognize each other, with the laboratory at the center of compliance requirements.

Experimental Protocols for Regulatory Compliance

Comprehensive Validation Protocol for Qualitative Microbiological Assays

Objective: To establish and verify performance specifications of a new qualitative microbiological assay in compliance with ISO 15189, IVDR, and CLIA requirements before implementation in routine diagnostics [16].

Scope: Applicable to all new qualitative microbiological assays, including antimicrobial susceptibility tests, introduced into the clinical microbiology laboratory.

Protocol Workflow:

Diagram 2: Validation Protocol Workflow. This diagram outlines the key stages in the validation process for qualitative microbiological assays, from initial planning to final documentation.

Methodology:

Validation Planning and Acceptance Criteria

- Define intended use, target population, and clinical claims

- Establish predetermined acceptance criteria for accuracy, precision, and other parameters

- Document validation plan including sample size justification and statistical approach [16]

Reference Standard and Sample Selection

- Select appropriate reference standard (gold standard method, clinical diagnosis, or consensus method)

- Collect a minimum of 5 positive and 5 negative samples for verification of established tests [12]

- For novel tests, include 50-100 clinical samples representing target population and potentially interfering organisms [16]

- Ensure samples span expected concentration ranges and include potentially cross-reacting organisms

Testing Procedure

- Perform blinded testing of clinical samples using both new method and reference standard

- Include quality controls and internal controls as appropriate

- Conduct reproducibility testing across multiple days, operators, and instrument lots if applicable

- Document all procedures, reagents, equipment, and environmental conditions

Data Analysis and Performance Calculation

- Calculate accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value

- Determine 95% confidence intervals for performance characteristics

- Analyze discordant results to identify patterns or systematic errors

- Compare results against predetermined acceptance criteria

Documentation and Reporting

Table 2: Essential Performance Parameters for Qualitative Microbiological Assays

| Parameter | ISO 15189 Requirement | IVDR GSPR Alignment | CLIA Verification Requirement | Recommended Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Verification of examination procedures [15] | Annex I General Requirements [14] | Required performance specification [12] | Comparison to reference method with clinical samples |

| Precision | Quality assurance monitoring [15] | Performance stability requirements | Required performance specification [12] | Repeated testing of positive and negative samples |

| Analytical Specificity | Consideration of interfering substances [15] | Annex I Requirement [14] | Limitations in methodologies [12] | Testing with potentially cross-reacting organisms |

| Reportable Range | Result traceability and reporting [15] | Performance characteristics | Reportable range establishment [12] | Testing samples with varying target concentrations |

| Sample Stability | Sample handling procedures [15] | Specimen receptacle requirements | Specimen storage criteria [12] | Time-course evaluation under various storage conditions |

Quality Management System Implementation Protocol

Objective: To establish and maintain a quality management system that satisfies ISO 15189 requirements while addressing IVDR stipulations for in-house device manufacturing [10].

Implementation Steps:

Gap Analysis and Planning

- Conduct comprehensive review of existing processes against ISO 15189 clauses 4-8

- Identify specific gaps in addressing IVDR requirements for in-house devices

- Develop implementation timeline with assigned responsibilities

Documentation System Establishment

- Create quality manual, procedures, work instructions, and records

- Implement document control system for approval, distribution, and revision

- Establish records management for traceability and retrieval

Process Implementation

- Define and document pre-examination, examination, and post-examination processes

- Establish impartiality and confidentiality safeguards per Clause 4 [15]

- Implement resource management for personnel, equipment, and facilities per Clause 6 [15]

- Develop management system procedures per Clause 8, including internal audits and corrective actions [15]

IVDR-Specific Supplementation

- Establish procedures for development, manufacture, and change control of in-house devices

- Implement surveillance procedures for device performance monitoring

- Create incident reporting and corrective action systems

- Develop equivalence analysis procedures for commercially available alternatives [10]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Qualitative Microbiological Assay Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Assay Development | Regulatory Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard Materials | Provides benchmark for comparison and accuracy assessment during validation [16] | Must be traceable to international standards; documentation required for audit purposes |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitors assay performance precision and stability over time [15] [12] | Should mimic patient samples; positive and negative controls required for each testing batch |

| Molecular Grade Reagents | Ensures reliability and reproducibility of nucleic acid-based assays | Must meet specifications for purity, stability, and performance; certificate of analysis required |

| Clinical Isolates Panel | Evaluates analytical specificity and inclusivity of detection claims [16] | Should represent target population diversity and potentially interfering organisms; well-characterized |

| Sample Collection Devices | Maintains specimen integrity from collection to testing [15] | Must be validated for compatibility with the assay; stability studies required |

Successfully navigating the regulatory landscape for qualitative microbiological assays requires a systematic approach that integrates the requirements of ISO 15189, IVDR, and CLIA into a cohesive quality framework. The protocols outlined provide a foundation for developing compliant, reliable assays that generate accurate results while meeting regulatory obligations. As the December 2025 deadline for ISO 15189:2022 implementation approaches and IVDR requirements continue to phase in, laboratories must prioritize understanding the interrelationships between these frameworks and establishing robust validation and quality management systems [13] [14]. Through diligent application of these principles and protocols, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure their microbiological assays meet the highest standards of quality, reliability, and regulatory compliance.

Within pharmaceutical and clinical microbiology, the reliability of qualitative microbiological assays is paramount for ensuring product safety and accurate diagnosis. These assays, which yield binary results such as "detected/not detected," form the cornerstone of tests for sterility, specific pathogens, and microbial limits. The validation of these methods is not merely a regulatory formality but a fundamental scientific requirement to establish their fitness for purpose. This document details the application notes and experimental protocols for four essential validation parameters—Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, and Limit of Detection (LOD)—framed within the context of a broader thesis on accuracy testing protocols for qualitative microbiological assays. The procedures outlined herein are aligned with standards such as USP <1223> and ISO 15189, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a rigorous framework for method qualification [17] [18] [16].

Core Principles of Qualitative Assay Validation

Qualitative assays differ fundamentally from their quantitative counterparts, as they aim to detect the presence or absence of a specific microorganism or a defined group of microorganisms, rather than determining their exact concentration. This distinction dictates a unique approach to validation. The parameters of Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, and LOD are interconnected, collectively providing a comprehensive picture of an assay's performance. Accuracy ensures the result is correct, Precision ensures it is reproducible, Specificity ensures it is exclusive to the target, and LOD defines its ultimate sensitivity. For any new method, demonstrating equivalency to a compendial method is a typical goal, requiring a structured comparison using a statistically justified number of samples [17] [4] [18]. A crucial first step is defining whether the work constitutes a verification (for unmodified, FDA-cleared tests) or a validation (for laboratory-developed tests or modified FDA methods) [4].

Detailed Parameter Analysis and Protocols

Accuracy

Accuracy establishes the degree of agreement between the test result and the true condition of the sample. For a qualitative assay, this means correctly identifying samples that are truly positive or truly negative for the target analyte [17].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: A minimum of 20 clinically relevant or product-specific isolates is recommended [4]. The sample panel must include a combination of positive samples (containing the target microorganism) and negative samples (containing non-target microorganisms or no microorganisms). Acceptable samples can be derived from certified reference materials, proficiency test samples, or previously characterized de-identified clinical or product samples [4].

- Testing Procedure: Test all samples using the new qualitative method (the alternative method) and a validated reference method (the compendial or comparative method) in parallel.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage agreement between the two methods.

- Acceptance Criteria: The calculated accuracy percentage must meet or exceed the manufacturer's stated claims or a pre-defined acceptance criterion (e.g., ≥95%) set by the laboratory director [4].

Table 1: Summary of Key Validation Parameters for Qualitative Microbiological Assays

| Parameter | Experimental Objective | Key Experimental Details | Data Analysis & Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy [17] [4] | Measure agreement with true or reference result. | - Minimum 20 samples (positive & negative) [4].- Parallel testing with reference method. | Percentage Agreement = (Correct Results / Total Results) × 100.Acceptance: ≥95% or per manufacturer claims [4]. |

| Precision (Repeatability) [17] [4] | Assess within-lab, within-operator variability. | - Test 2 positive & 2 negative samples [4].- Perform in triplicate over 5 days by 2 operators. | Percentage Agreement calculated for each sample level.Acceptance: ≥95% agreement across all replicates [4]. |

| Specificity [17] | Confirm detection of target and non-detection of non-targets. | - Challenge with target and related non-target strains.- Include samples with potential interferents (APIs, excipients). | All target microorganisms recovered; no interference from non-targets or matrix.Acceptance: 100% recovery of targets; 0% false positives. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) [17] [19] | Determine the lowest number of microorganisms that can be reliably detected. | - Prepare serial dilutions of target microorganism(s).- Low-level challenge (<100 CFU) is often used [17]. | The lowest concentration where ≥95% of replicates test positive.Acceptance: Consistent detection at the target low level. |

Precision

Precision, or reliability, measures the closeness of agreement between a series of test results obtained under prescribed conditions. For qualitative assays, it confirms the consistency of the "detected" or "not detected" result upon repeated testing of the same sample [17].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Select a minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative samples that represent a range of expected results (e.g., weak positive, strong positive) [4].

- Testing Procedure: Test each sample in triplicate, over 5 separate days, by two different analysts to capture within-run, between-run, and operator-related variance [4]. If the system is fully automated, operator variance may not be required.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of results in agreement for each sample level across all replicates and days.

- Acceptance Criteria: The method is considered precise if it demonstrates ≥95% agreement across all replicates for each sample level [4].

Specificity

Specificity (or Selectivity) is the ability of the assay to detect only the target microorganism(s) without interference from other microorganisms, product components, or matrix elements [17] [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation:

- Microbial Challenge: Challenge the assay with a panel of closely related non-target microorganisms and a range of the target microorganisms. The challenge level should be low, typically <100 Colony Forming Units (CFU), to rigorously assess the method's resolution [17].

- Interference Testing: Inoculate the target microorganism into the product matrix (e.g., containing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), excipients, degradation products) to check for inhibition or enhancement.

- Testing Procedure: Test all challenge and interference samples using the alternative method.

- Data Analysis: For the microbial challenge, record the rate of true positives (target detected) and false positives (non-target detected). For the interference study, compare recovery in the presence and absence of the matrix.

- Acceptance Criteria: The method should demonstrate 100% recovery of all challenge target microorganisms and no detection of closely related non-target strains. Freedom from interference is confirmed if recovery in the product matrix is equivalent to the control [17].

Limit of Detection (LOD)

The LOD is the lowest number of target microorganisms that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified, under stated experimental conditions. It is a critical parameter for ensuring the assay's sensitivity at the required level of control [17] [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Perform serial dilutions of a calibrated suspension of the target microorganism(s) to create a range of low concentrations (e.g., from 10 CFU to 100 CFU per test sample) [17] [19].

- Testing Procedure: Test a sufficient number of replicates (e.g., n=10-20) at each dilution level using the alternative method.

- Data Analysis: The LOD is determined as the lowest concentration at which ≥95% of the test replicates yield a positive result [17]. Statistical approaches, such as those based on a Poisson confidence interval, can be employed to model the inherent variability in microbial distribution and provide a more robust LOD estimate [19].

- Acceptance Criteria: The determined LOD must be equal to or lower than the required sensitivity for the assay's intended use. A common pharmacopeial requirement is the consistent detection of a low-level challenge of <100 CFU [17].

Diagram 1: LOD Determination Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful execution of validation protocols relies on a suite of critical materials and reagents. The following table details these essential components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Validation Studies

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Microbial Strains | Provides genetically defined, traceable microorganisms for accuracy, specificity, and LOD studies, ensuring challenge integrity. |

| Selective and Non-Selective Culture Media | Used for compendial method comparison, purity checks, and assessing medium suitability in the presence of product matrix [17]. |

| Inactivation Agents/Neutralizers | Critical for evaluating specificity and accuracy in antimicrobial products by neutralizing the product's effect to allow microbial recovery. |

| Standardized Animal Sera/Blood | Essential component in blood culture analysis and for preparing specific media required for the growth of fastidious microorganisms. |

| Molecular Grade Reagents (for PCR/NGS) | High-purity enzymes, nucleotides, and buffers are mandatory for validating molecular methods to ensure sensitivity and specificity while preventing inhibition. |

| Quality Control Organisms | Well-characterized non-target and target strains used for ongoing precision monitoring and routine system suitability testing post-validation [17]. |

The rigorous validation of qualitative microbiological assays through the assessment of Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, and Limit of Detection is a non-negotiable prerequisite for their application in research, drug development, and clinical diagnostics. The experimental protocols and application notes detailed herein provide a scientifically sound and regulatory-aligned framework. By adhering to these structured procedures, scientists can generate robust data that unequivocally demonstrates the reliability of their methods, thereby contributing to the overarching thesis of ensuring accuracy and integrity in microbiological testing. This foundational work not only supports regulatory submissions but also builds the critical trust in data that underpins public health and patient safety.

From Plan to Data: A Step-by-Step Protocol for Accuracy Testing

A priori power and sample size calculations are crucial for designing microbiological studies that yield valid, reliable, and scientifically sound conclusions. These calculations ensure that studies are capable of detecting a meaningful effect—whether it pertains to the accuracy of a new qualitative assay, the presence of a pathogen, or a shift in microbial ecology—without resorting to excessive resources that raise ethical and cost concerns [20] [21]. An inadequate sample size is a fundamental statistical error that can lead to false negatives (Type II errors) or an overstatement of the analysis results, undermining the entire research project [21].

In the specific context of accuracy testing for qualitative microbiological assays, traditional sample size calculations must be adapted to accommodate the unique features of microbiome and pathogen detection data. This includes the use of attributes sampling plans, which are the standard for microbiological testing in both food and clinical settings [22]. This application note provides researchers with the frameworks and practical protocols to establish robust sample sizes and design rigorous experimental validation studies.

Theoretical Foundations: Power, Error, and Sampling Plans

Core Statistical Concepts for Sample Size

The foundation of sample size calculation lies in the balance between Type I (false positive) and Type II (false negative) errors. The following concepts are essential [21]:

- Null Hypothesis (H0): The premise that there is no effect or no difference (e.g., the new assay is no more accurate than the reference method).

- Alternative Hypothesis (H1): The premise that there is a true effect (e.g., the new assay is more accurate).

- Alpha (α): The probability of rejecting a true null hypothesis (Type I error). It is typically set at 0.05.

- Beta (β): The probability of failing to reject a false null hypothesis (Type II error).

- Power (1-β): The probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis. A power of 0.8 (80%) is conventionally considered the minimum target.

- Effect Size (ES): The magnitude of the effect or difference that is considered biologically or clinically meaningful. Defining the ES is a key scientific, not just statistical, decision.

The relationship between these elements is delicate; reducing the risk of one type of error increases the risk of the other. Therefore, the study design must strike a balance appropriate for the research context [21]. For instance, in a pilot study, an alpha of 0.10 might be acceptable, whereas for a high-stakes clinical validation, a much lower alpha (e.g., 0.001) might be necessary.

Attributes Sampling Plans for Microbiological Data

Microbiological specifications, central to assay validation, often rely on attributes sampling plans [22]. These plans classify results into categories rather than using continuous data.

There are two primary types of attributes plans, summarized in the table below:

Table 1: Types of Attributes Sampling Plans for Microbiological Testing

| Plan Type | Description | Key Components | Common Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Class Plan | Results fall into one of two classes: acceptable or defective [22]. | n, c |

Pathogen detection (e.g., Salmonella, Listeria). A positive result in any sample may lead to rejection. |

| 3-Class Plan | Results fall into one of three classes: acceptable, marginally acceptable, or defective [22]. | n, c, m, M |

Quality indicators (e.g., aerobic plate count, coliforms). Allows for a marginal zone reflecting good manufacturing practice. |

Key Components Defined [22]:

n: The number of sample units tested from a lot.c: The maximum number of sample units permitted to exceed the marginal limit (m) but still be below the maximum limit (M) before the lot is rejected.m: The marginal limit separating acceptable quality from marginally acceptable quality.M: The maximum limit beyond which quality is unacceptable.

The stringency of a plan (i.e., its ability to reject a defective lot) increases with larger n and smaller c, m, and M values. This stringency is determined by the risk associated with the microbiological target, considering factors like the severity of illness, vulnerability of the consumer, and potential for microbial growth in the product [22].

Sample Size Calculation Methods and Scenarios

General Formulas for Common Study Types

The formulas for sample size calculation vary depending on the study design and the nature of the data. The following table summarizes key formulas for scenarios relevant to assay validation [21].

Table 2: Sample Size Calculation Formulas for Different Study Types

| Study Type | Formula | Variable Explanations |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion (for Surveys/Prevalence) | N = (Zα/2² * P(1-P)) / E² |

N: Sample size; P: Expected proportion; E: Margin of error; Zα/2: 1.96 for α=0.05. |

| Comparison of Two Proportions | N per group = [ (Zα/2 * √(2*p̄(1-p̄)) + Zβ * √(p1(1-p1) + p2(1-p2)) )² ] / (p1 - p2)² where p̄ = (p1 + p2)/2 |

p1, p2: Expected proportions in groups 1 and 2; Zα/2: 1.96 for α=0.05; Zβ: 0.84 for 80% power. |

| Comparison of Two Means | N per group = ( (Zα/2 + Zβ)² * 2σ² ) / d² |

σ: Pooled standard deviation; d: The difference between means considered meaningful. |

Practical Considerations and Minimums in Assay Validation

Beyond these general formulas, specific validation guidelines provide concrete minimum sample requirements. For example, when validating a new quantitative assay against a predicate method, the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) provides specific frameworks [23]:

- Precision (CLSI EP05-A3): A minimum of 20 days of testing with 2 replicates of at least 2 control levels (a 20 x 2 x 2 format) [23].

- Bias/Method Comparison (CLSI EP09-A3): A minimum of 40 patient samples, tested over several days, is required to compare a new method to a reference [23].

- Reference Interval Verification (CLSI EP28): A minimum of 20 samples from healthy volunteers is required to verify a provided reference range [23].

For qualitative microbiological assays, the focus is on agreement (e.g., positive percent agreement and negative percent agreement) with a reference method. The sample size must include enough positive and negative samples to precisely estimate these agreement metrics. This often requires targeted enrollment or sample selection to ensure a sufficient number of positive samples, which may be rare in the general population.

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

Protocol for a Method Comparison Study (Bias Assessment)

This protocol is designed to assess the bias of a new qualitative microbiological assay against a reference method.

1. Objective: To determine the systematic difference (bias) in results between the new investigational assay and the established reference method.

2. Hypothesis:

- H0: There is no difference in the results between the new and reference methods.

- H1: There is a statistically significant difference in the results between the new and reference methods.

3. Experimental Design:

- Sample Type: Use well-characterized patient or environmental samples with known values by the reference standard [23].

- Sample Number: A minimum of 40 unique samples. The samples should ideally provide an even distribution of positive, negative, and, if relevant, low-positive results across the expected analytical range [23].

- Testing Procedure: Each sample is tested once by both the new and the reference method. Testing should be performed over several days (at least 3-5 days) to capture inter-day variability [23].

- Blinding: The operators should be blinded to the results of the other method to prevent bias.

4. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percent agreement (Overall, Positive, and Negative).

- Use a statistical test such as McNemar's test for paired nominal data to assess if the discrepancy between the two methods is statistically significant.

- Report the results with 95% confidence intervals.

Protocol for a Precision (Repeatability) Study

1. Objective: To establish the variance and random error of the assay under unchanged conditions.

2. Hypothesis:

- H0: The variance of replicate measurements is within the pre-defined allowable total error.

- H1: The variance of replicate measurements exceeds the pre-defined allowable total error.

3. Experimental Design:

- Sample Type: Use stable quality control (QC) materials, optimally from a third-party vendor, at at least two levels (e.g., low-positive and high-positive) near critical decision points [23].

- Testing Procedure: Implement a 20 x 2 x 2 design: two runs of duplicate measurements per day for each level of QC, repeated over 20 separate days [23].

- Total Analyses: 80 analyses per QC level.

4. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the repeatability (within-run) and intermediate (between-day) standard deviation and coefficient of variation (%CV) using a two-way nested analysis of variance (ANOVA) [23].

- The total observed variance should not exceed 33% of the total allowable error goal set a priori for the assay.

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

Sample Size Calculation and Validation Workflow

Attributes Sampling Plan Decision Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Microbiological Assay Validation

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose in Validation |

|---|---|

| Quality Control (QC) Materials | Stable, characterized samples used in precision studies to establish variance and in daily runs to monitor assay performance [23]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | High-metrological-order samples with assigned target values, used to establish accuracy and bias against a reference method [23]. |

| Clinical or Environmental Samples | Well-characterized, matrix-matched samples used in method comparison studies to assess agreement and bias under realistic conditions [23]. |

| Selective and Enrichment Media | Used to isolate and promote the growth of the target microorganism, ensuring the method's fitness for purpose in a complex sample matrix. |

| Molecular Detection Reagents | Primers, probes, and master mixes for PCR-based assays. Their quality and lot-to-lot consistency are critical for the robustness of the validation. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Tools like EP Evaluator or Analyse-it are used to perform the complex calculations required by CLSI standards for precision, bias, and linearity [23]. |

The reliability of qualitative microbiological assays is foundational to diagnostic accuracy in clinical microbiology and drug development. These assays, designed to detect the presence or absence of specific microorganisms, require rigorous validation to ensure that a "positive" or "detected" result is unequivocally accurate. The selection of an appropriate reference standard is the most critical variable in this validation process, serving as the benchmark against which all assay performance is measured. Within a broader research thesis on accuracy testing protocols, this application note provides a detailed framework for selecting between two principal categories of reference standards: Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) and characterized clinical isolates. We detail their properties, applicable international standards, and provide verified experimental protocols for their use in validation studies, ensuring that methods meet the demands of standards such as ISO 15189 and the In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR) [16].

Understanding Reference Standards

Certified Reference Materials (CRMs)

CRMs are highly characterized materials produced under stringent, accredited processes. They are accompanied by a certificate of analysis that provides traceability to the original culture and confirms defined properties such as identity, viability, and well-characterized traits [24]. These materials are produced under ISO 17034 and ISO/IEC 17025 accredited processes, ensuring the highest level of quality assurance, accuracy, and traceability for scientific research [24] [25]. For qualitative assays, CRMs provide a known positive and negative control, allowing laboratories to confirm that their methods can correctly identify the target organism.

- Key Advantages: CRMs offer superior traceability, reduced preparation time, and come with a defined Certificate of Analysis (CoA). Their use minimizes inter-laboratory variability and is often stipulated for testing and calibration in ISO 17025 accredited laboratories [24] [25].

- Physical Formats: Common formats include ready-to-use discs or pellets (e.g., Vitroids, LENTICULE discs) comprising a solid, water-soluble matrix containing the live microbial culture in a precisely quantified form, ensuring a consistent and defined inoculum for every test [25].

Characterized Clinical Isolates

Characterized clinical isolates are microbial strains typically obtained from clinical specimens and well-characterized in-house or by a reference laboratory. These isolates represent the wild-type strains encountered in routine diagnostics and are essential for challenging an assay with real-world genetic diversity. Isolate sets are available from specialized providers for specific verification purposes, such as antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) [26].

- Key Advantages: Clinical isolates provide genetic and phenotypic diversity, making them ideal for verifying an assay's ability to detect a wide range of strains. They are crucial for testing assays against emerging resistant strains or genetic variants [26].

- Considerations: Their use requires significant laboratory resources for proper isolation, expansion, characterization, and long-term storage. Without meticulous documentation, traceability can be a challenge compared to CRMs.

Table 1: Comparison of Certified Reference Materials and Clinical Isolates

| Feature | Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Characterized Clinical Isolates |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Method validation, calibration, routine QC, regulatory submissions [24] | Verifying assay performance against strain diversity, challenging method inclusivity [26] |

| Traceability | Fully traceable to a recognized culture collection (e.g., NCTC, ATCC) [24] [25] | Varies; requires internal documentation to patient isolate or reference lab |

| Characterization | Well-defined identity and characteristics; certificate of analysis provided [24] | Requires in-house characterization (phenotypic, genotypic) |

| Format & Stability | Ready-to-use formats (e.g., discs); stability of 16-24 months [25] | Requires preparation of liquid cultures or glycerol stocks; stability dependent on storage conditions |

| Standardization | High; produced under ISO 17034 and ISO/IEC 17025 [24] [25] | Lower; potential for batch-to-batch variability |

| Cost & Time | Higher material cost, but significant time savings in laboratory preparation [25] | Lower acquisition cost, but high labor and resource cost for characterization and maintenance |

Selection Criteria and Application

The choice between CRMs and clinical isolates is not mutually exclusive; a robust validation protocol often requires both.

Strategic Selection for Assay Validation

- Use CRMs for: Establishing the fundamental accuracy of a new assay. They are ideal for determining diagnostic sensitivity and specificity during initial validation [24] [1]. They are also critical for routine Quality Control (QC) to ensure day-to-day assay consistency and for use in growth promotion tests of culture media [25].

- Use Clinical Isolates for: Challenging the assay's performance against a panel of well-characterized strains, including those with known genetic mutations or atypical phenotypes [26]. This verifies the method's robustness and inclusivity, ensuring it can detect the target organism across its natural variation.

Sourcing and Documentation

- CRMs: Should be sourced from reputable providers like ATCC or Sigma-Aldrich, which offer materials with full traceability and ISO accreditation [24] [25].

- Clinical Isolates: Can be sourced from in-house collections, clinical specimens (with ethical approval), or specialized providers offering isolate sets for specific verification purposes, such as AST method verification [26].

- Documentation: For every reference material used, maintain detailed records including source, date of receipt, passage history, storage conditions, and all characterization data. This documentation is essential for audit trails and meeting ISO 15189 requirements [16].

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols provide a practical guide for utilizing CRMs and clinical isolates in the verification of a qualitative microbiological assay.

Protocol 1: Verification Using Certified Reference Materials

This protocol describes the use of CRMs to establish the detection capability of a qualitative assay for a specific target, such as Listeria monocytogenes [25] [1].

1. Principle: A defined number of colony-forming units (CFUs) from a CRM are introduced into the assay's sample matrix to challenge the entire method from sample processing to detection. A successful result confirms that the assay can detect the target at the level of the CRM's certification.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- CRM of the target organism (e.g., Listeria monocytogenes Vitroids disc) [25].

- Appropriate non-selective and selective enrichment broths.

- Culture media for confirmation (e.g., selective agar plates).

- Sterile diluents (e.g., Buffered Peptone Water).

- The qualitative assay under verification (e.g., PCR kit, lateral flow device, or cultural method).

3. Procedure: 1. Reconstitution: Hydrate the CRM disc as per the manufacturer's instructions in a specified volume of diluent to create a stock suspension with a certified CFU range (e.g., 15-80 CFU per disc) [25]. 2. Sample Spiking: Aseptically spike a known volume of the stock suspension into the appropriate sample matrix (e.g., 25g of food homogenate or a simulated clinical sample). This is the "test portion" [1]. 3. Enrichment and Detection: Process the spiked sample through the complete qualitative assay procedure, including any required enrichment steps and the final detection method [1]. 4. Controls: Include an unspiked negative control (matrix only) and a positive control (if available) in the same test run. 5. Confirmation: For cultural methods, typical colonies from selective plates must be confirmed as the target organism via standard techniques (e.g., biochemical, serological, or molecular methods) [1]. 6. Replication: Repeat the test a sufficient number of times (e.g., n=5 or as per validation guidelines) to establish statistical confidence [16].

4. Interpretation of Results:

- Acceptable Result: The assay yields a positive/detected result for the spiked sample in all replicates. The negative control must remain negative.

- Unacceptable Result: A negative/not detected result for the spiked sample indicates a potential problem with the assay's sensitivity, the enrichment conditions, or the detection method, requiring investigation.

Protocol 2: Verification Using Characterized Clinical Isolates

This protocol uses a panel of clinical isolates to challenge the assay's ability to detect a diverse range of strains, a key aspect of inclusivity testing [16] [26].

1. Principle: A panel of well-characterized clinical isolates, representing the genetic and phenotypic diversity of the target organism, is tested using the qualitative assay. This verifies that the assay can reliably detect different strains and is not affected by known variations.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Panel of characterized clinical isolates (e.g., 10-30 strains) [16] [26].

- Non-selective culture media (e.g., Tryptic Soy Agar/Broth).

- Equipment for preparing McFarland standards or equivalent for standardizing inoculum.

- The qualitative assay under verification.

3. Procedure: 1. Culture Preparation: Revive each clinical isolate from storage and subculture onto non-selective agar to ensure purity and viability. 2. Inoculum Standardization: Prepare a suspension of each isolate in a sterile diluent, adjusting the turbidity to a 0.5 McFarland standard or equivalent. This creates a standardized, high-concentration inoculum (~1 x 10^8 CFU/mL). 3. Sample Preparation: Dilute the standardized suspension to a low concentration (e.g., aiming for 10-100 CFU per test portion) and spike it into a sterile, neutral matrix or the actual sample matrix. 4. Testing: Process each spiked sample through the complete qualitative assay procedure. 5. Controls: Include a negative control (matrix only) for each isolate tested.

4. Interpretation of Results:

- Acceptable Result: The assay correctly identifies all (or a high percentage, e.g., >95-99%) of the clinical isolates as positive, demonstrating robust inclusivity.

- Unacceptable Result: Failure to detect one or more strains indicates a lack of inclusivity, which may be due to genetic variations not recognized by the assay's primers, antibodies, or culture conditions.

Table 2: Key Parameters for Verification Studies

| Parameter | Typical Acceptance Criterion | Primary Reference Material | Sample Size Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Sensitivity | ≥ 95% or as claimed by manufacturer | Clinical Isolate Panel | 50+ positive samples [16] |

| Diagnostic Specificity | ≥ 95% or as claimed by manufacturer | Clinical Isolate Panel (off-target) | 50+ negative samples [16] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Consistent detection at claimed CFU level | CRM | 20 replicates at target concentration [16] |

| Inclusivity | Detection of all or vast majority of strains | Clinical Isolate Panel | 10-30 target strains [16] |

Workflow and Material Selection Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting and applying reference standards within a microbiological assay verification protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for executing the verification protocols described in this note.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Microbiological Assay Verification

| Reagent Solution | Function in Verification | Key Characteristics & Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) [24] [25] | Serves as the primary benchmark for accuracy; used for LOD determination, growth promotion testing, and routine QC. | ISO 17034 produced; certificate of analysis; defined CFU/count; traceable to international culture collection (e.g., NCTC, ATCC). |

| Characterized Clinical Isolates [26] | Challenges assay against real-world strain diversity; used for inclusivity and robustness testing. | Well-defined phenotypic and genotypic profile; should include common, rare, and resistant strains. |

| Selective & Non-Selective Culture Media [1] | Supports the growth and isolation of target organisms during assay procedure and confirmation steps. | Performance tested with CRMs; defined shelf-life; complies with relevant standards (e.g., EN ISO 11133). |

| AST Verification Isolate Sets [26] | Specific for verifying performance of antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) methods for new agents. | Provided with summarized modal MICs and categorical results from reference methods (e.g., CLSI). |

| Sterile Diluents & Matrix | Used for reconstituting CRMs, standardizing inoculum, and simulating sample conditions. | Confirmed to be non-inhibitory to target organisms; sterile. |