E. coli Bacterial Transformation: A Complete Guide from Foundational Principles to Advanced Optimization for Researchers

This comprehensive guide details the E.

E. coli Bacterial Transformation: A Complete Guide from Foundational Principles to Advanced Optimization for Researchers

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details the E. coli bacterial transformation process, a cornerstone technique in molecular biology and drug development. It provides foundational knowledge on how bacteria uptake foreign DNA, compares established methodological protocols including heat shock and electroporation, and offers in-depth troubleshooting and optimization strategies to maximize transformation efficiency. Tailored for researchers and scientists, the article also presents a comparative analysis of methods and strains, supported by recent scientific literature, to enable robust experimental validation and successful application in biomedical research.

Understanding Bacterial Transformation: Core Principles and Cellular Competency

Bacterial transformation is a fundamental molecular biology technique involving the introduction of foreign DNA, typically a plasmid, into a bacterial cell. In a laboratory setting, this process allows bacteria to acquire new genetic traits, enabling them to replicate the foreign DNA and, if the plasmid contains a functional gene, express it to produce proteins of interest [1] [2]. This technique is vital for various applications, from basic research to the industrial production of pharmaceuticals like insulin [2].

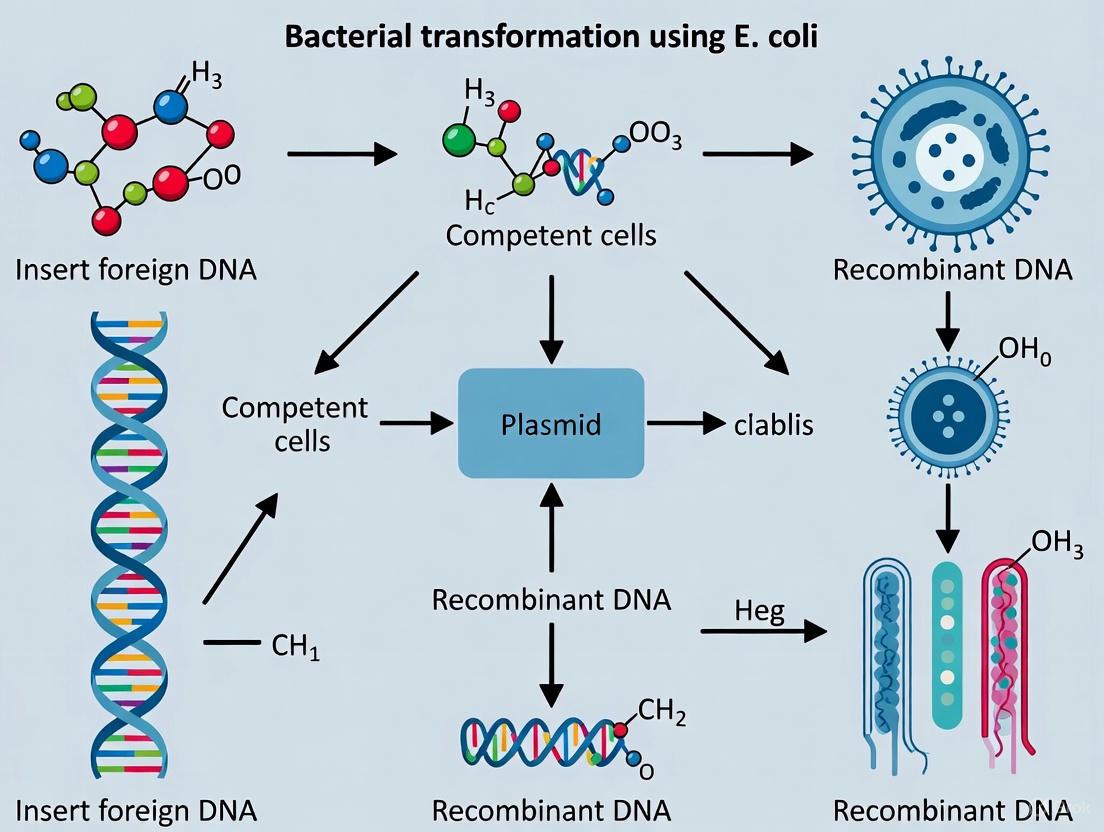

The process of bacterial transformation relies on three key steps: plasmid uptake, where DNA is introduced into bacterial cells; cell recovery, a period for bacteria to repair and express antibiotic resistance genes; and selection, where only successfully transformed bacteria are able to grow on antibiotic-containing media [2]. The workflow below illustrates this core process.

Quantitative Data in Bacterial Transformation

Transformation efficiency is a critical metric for evaluating the success of a transformation experiment. It is defined as the number of colony-forming units (CFU) produced per microgram of plasmid DNA used [1]. The table below summarizes key quantitative aspects.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters for Bacterial Transformation

| Parameter | Typical Range or Value | Protocol Note |

|---|---|---|

| Transformation Efficiency | Expressed as CFU/μg DNA [1] | A measure of protocol success; higher is better. |

| Competent Cell Volume | 50–100 μL [1] | Used per transformation reaction. |

| Plasmid DNA Amount | 1–10 ng (intact plasmid) [1] | Using more DNA can sometimes lower efficiency. |

| Heat Shock Duration | 30–60 seconds [3] | 45 seconds is often ideal, but strain-dependent. |

| Recovery Time | 45–60 minutes [3] | Crucial for antibiotic resistance gene expression. |

| Outgrowth Media | SOC Media [1] | Can increase transformed colonies 2- to 3-fold vs. LB. |

| Natural Competency of E. coli | 10⁻⁵ – 10⁻¹⁰ [1] | Highlights need for artificial competence methods. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Heat Shock Transformation

The following is a standardized protocol for transforming chemically competent E. coli cells via the heat shock method, consolidating best practices from cited sources [1] [3].

Preparation

- Thaw chemically competent E. coli cells on ice (approximately 20–30 minutes).

- Pre-warm LB agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotic to room temperature.

- Pre-warm SOC or LB recovery media to 37°C.

Transformation

- Gently mix the thawed competent cells; avoid vortexing.

- Aliquot 50 μL of cells into a pre-chilled microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 1–10 ng of plasmid DNA (or 1–5 μL of a ligation mixture) to the cells. Gently mix by flicking the tube.

- Incubate the DNA-cell mixture on ice for 20–30 minutes.

Heat Shock

- Transfer the tube to a pre-heated 42°C water bath for 30 seconds (for smaller tubes, a shorter time may be needed). Do not shake.

- Immediately return the tube to ice for at least 2 minutes.

Recovery

- Add 250–1,000 μL of pre-warmed SOC media to the tube.

- Incubate the tube at 37°C in a shaking incubator (225 rpm) for 45–60 minutes. This outgrowth step allows the bacteria to express the antibiotic resistance gene encoded on the plasmid.

Selection

- Spread 50–200 μL of the transformation culture onto the pre-warmed selective LB agar plates.

- Incubate the plates upside down at 37°C overnight (16–24 hours).

- The following day, transformed colonies should be visible on the plate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful transformation relies on specific biological materials and reagents. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Bacterial Transformation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Chemically Competent Cells | E. coli cells (e.g., K12, TOP10) treated with cations like CaCl₂ to make their membranes permeable to DNA [4] [1] [5]. |

| Plasmid DNA | A circular DNA vector containing an origin of replication for propagation in bacteria and a selectable marker (e.g., antibiotic resistance gene) [3]. |

| LB Agar Plates with Antibiotic | A solid growth medium used for selection. Only bacteria that have successfully taken up the plasmid and its resistance gene will grow [4] [3]. |

| SOC Recovery Media | A nutrient-rich liquid medium used after heat shock to allow cell recovery and expression of the antibiotic resistance gene before selection [1]. |

| Cation Solutions (e.g., CaCl₂) | Used in the preparation of chemically competent cells. The cations help neutralize the negative charges on the cell membrane and DNA, facilitating DNA uptake [1]. |

| Antibiotics (e.g., Kanamycin, Ampicillin) | Selectable agents added to growth media to inhibit the growth of untransformed cells, ensuring only successful transformants proliferate [4] [3]. |

Historical and Mechanistic Context

The concept of bacterial transformation was first demonstrated in 1928 by Frederick Griffith using Streptococcus pneumoniae [6]. His experiment showed that a "transforming principle" from a heat-killed virulent strain (S) could be taken up by a live, non-virulent strain (R), conferring virulence. This principle was later identified by Avery, MacLeod, and McCarty as DNA, establishing it as the genetic material [6].

The modern heat shock method leverages this natural principle artificially. The process involves making bacterial cells "competent" by treating them with calcium chloride. The Ca²⁺ ions are thought to neutralize repulsive charges on the DNA backbone and the bacterial cell membrane [1]. A subsequent brief heat shock creates a thermal imbalance, thought to cause the formation of pores in the membrane, allowing the plasmid DNA to enter the cell. After returning to optimal growth conditions, the cell membrane repairs itself, and the bacterium can propagate the plasmid. The relationship between key bacterial strains in Griffith's seminal work is shown below.

Plasmids are extra-chromosomal genetic elements that are fundamental to molecular biology, serving as versatile vehicles for gene cloning, protein expression, and genetic engineering [7]. These circular DNA molecules replicate independently of the bacterial chromosome and have been domesticated from their natural states into essential tools for biotechnology and therapeutic development. The functionality of a plasmid is governed by two critical genetic elements: the origin of replication (ORI), which controls plasmid replication and copy number, and the selectable marker, which enables selective pressure to maintain the plasmid within a bacterial population [8] [9]. For researchers working with E. coli transformation systems, understanding the interplay between these elements is crucial for experimental success, influencing everything from transformation efficiency to recombinant protein yield.

The historical significance of plasmid engineering was demonstrated in pioneering experiments as early as 1974, when researchers successfully joined Staphylococcus plasmid genes to the E. coli pSC101 plasmid, creating hybrid molecules that replicated as functional units in E. coli and expressed genetic information from both parent DNA molecules [10]. This foundational work established the principle that plasmid elements could function across bacterial species, expanding the possibilities for genetic engineering. Today, plasmid engineering continues to evolve with sophisticated approaches to optimize copy number, stability, and functionality for specific research and industrial applications.

Origins of Replication: The Copy Number Control Center

The origin of replication (ORI) is a specific DNA sequence where plasmid replication initiates, determining both the copy number (number of plasmid copies per cell) and host range (bacterial species in which the plasmid can replicate) [9]. The ORI includes the origin of vegetative replication (oriV) where replication begins, plus coding sequences for proteins (such as Rep proteins) that bind to oriV and regulate replication initiation, copy number control, and plasmid partitioning [9].

Plasmid replication is typically regulated by negative feedback mechanisms that narrow the distribution of plasmid copy numbers across single cells [7]. Many plasmids also encode active partitioning systems (Par systems) that ensure proper segregation of plasmid copies to daughter cells during cell division, significantly reducing the rate of plasmid loss [7]. Without such stabilization mechanisms, plasmid-free cells can rapidly emerge and outcompete plasmid-containing cells, especially if plasmid maintenance imposes a metabolic burden on the host [7].

Table 1: Common Origins of Replication and Their Properties

| Origin Type | Copy Number | Host Range | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pUC/pMB1 | 500-700 [11] | Narrow | High copy number, minimal size | High-yield protein expression, gene cloning |

| pBR322 | 15-20 [11] | Narrow | Moderate copy number, proven stability | General cloning, protein expression |

| pSC101 | ~5 [10] | Narrow | Very low copy number, high stability | Expression of toxic genes, metabolic engineering |

| RK2 | Variable [9] | Broad | Engineerable copy number [9] | Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, cross-species applications |

| pVS1 | Variable [9] | Broad | Engineerable copy number [9] | Binary vectors, plant and fungal transformation |

Recent advances in ORI engineering demonstrate that copy number can be systematically optimized for specific applications. Using directed evolution approaches with high-throughput growth-coupled selection assays, researchers have identified mutations in Rep proteins that significantly increase plasmid copy number across diverse origins including pVS1, RK2, pSa, and BBR1 [9]. These mutations often occur at dimerization interfaces of Rep proteins, potentially reducing "handcuffing" (dimer-mediated inhibition of replication) and enabling higher replication rates [9]. Such engineered high-copy-number variants have demonstrated remarkable improvements in transformation efficiency, with stable transformation efficiencies increasing by 60-100% in Arabidopsis thaliana and 390% in the oleaginous yeast Rhodosporidium toruloides [9].

Selectable Markers: Ensuring Plasmid Maintenance

Selectable markers are genes that confer a survival advantage to plasmid-containing cells under specific growth conditions, enabling selective pressure that maintains plasmid inheritance across bacterial generations [8]. Typically, these markers confer resistance to antibiotics, allowing only transformed cells to grow in antibiotic-containing media. The selectable marker is arguably the most critical element for ensuring plasmid stability in bacterial cultures, as it prevents the overgrowth of plasmid-free cells that inevitably arise through imperfect plasmid segregation or replication errors [7].

Table 2: Common Selectable Markers and Their Mechanisms

| Antibiotic | Cell Type | Mechanism of Action | Resistance Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | Prokaryote | Inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis | β-lactamase enzyme hydrolyzes β-lactam ring [8] |

| Chloramphenicol | Prokaryote | Binds to 50S ribosomal subunit, inhibiting protein synthesis | Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase modifies antibiotic [8] |

| Kanamycin | Prokaryote | Binds to 70S ribosomal subunit, inhibiting protein synthesis | Aminoglycoside phosphotransferase modifies antibiotic |

| Tetracycline | Prokaryote | Binds to 30S ribosomal subunit, inhibiting translocation | Membrane-associated protein prevents antibiotic uptake [8] |

| Hygromycin B | Eukaryote | Inhibits protein synthesis by disrupting translocation | Hygromycin B phosphotransferase enzyme [8] |

While antibiotic resistance markers are widely used, they present certain limitations, including loss of selective pressure due to antibiotic degradation and potential contamination of therapeutic products with antibiotics, which may be unacceptable for medical applications [8]. Additionally, ampicillin resistance presents specific challenges because Ampr cells secrete β-lactamase into the medium, gradually hydrolyzing the antibiotic and potentially allowing plasmid-free cells to grow after extended culture periods [8]. This can lead to the appearance of "satellite colonies" around genuine transformants on agar plates. To mitigate this issue, researchers can use more stable carbenicillin instead of ampicillin or limit culture times to 8-10 hours [8].

Alternative selection strategies that avoid antibiotics are increasingly important for biopharmaceutical production. These include complementation of essential genes, toxin-antitoxin systems, and metabolic pathway engineering that creates auxotrophies requiring plasmid-borne genes for survival [8].

Essential Protocols for Plasmid Engineering

Plasmid Copy Number Determination by qPCR

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) provides a sensitive and accurate method for determining plasmid copy number, essential for characterizing plasmid behavior and optimizing expression systems [11].

Materials and Reagents:

- Bacterial culture harboring the plasmid of interest

- Primers targeting a single-copy chromosomal gene (e.g., tdk encoding thymidine kinase)

- Primers targeting the plasmid ORI region

- qPCR reagents and instrumentation

- Known copy number control plasmid (e.g., pBR322 with ~19 copies/cell)

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Prepare bacterial lysates from cultures with defined cell counts (10²–10⁵ cells/μL). Incubate at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by immediate freezing at -4°C [11].

- Primer Design and Validation: Design primers targeting a single-copy chromosomal reference gene and a conserved region of the plasmid ORI. Verify primer specificity and efficiency (ideal efficiency: 1.85-2.05) [11].

- qPCR Reaction: Perform qPCR with both primer sets using the following conditions:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 3 minutes

- 40 cycles of: 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds

- Melting curve analysis: 65°C to 95°C, increment 0.5°C [11]

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Plasmid/Chromosome (P/C) ratio using the formula:

- P/C ratio = 2^(Ctchromosome - Ctplasmid)

- Compare the P/C ratio of test plasmids to the standard curve generated from control plasmids with known copy numbers [11].

Applications and Limitations: This method provides precise copy number determination but requires careful primer design and validation. It is particularly valuable for characterizing engineered ORI variants and optimizing expression systems for industrial protein production, where low-copy-number plasmids are often preferred for their enhanced stability [11].

Plasmid Loss Rate Measurement

Accurate measurement of plasmid loss rates is essential for understanding plasmid stabilization mechanisms and designing stable expression systems [7].

Materials and Reagents:

- Plasmid-containing bacterial strain

- Selective and non-selective growth media

- Microscope slides and agarose pads for microscopy-based methods

- 96-well plates for fluctuation tests

- Appropriate antibiotics for counterselection

Procedure - Modified Fluctuation Test:

- Culture Preparation: Grow plasmid-containing cells overnight in selective medium to saturation [7].

- Dilution and Outgrowth: Dilute the culture by approximately 10⁸ into non-selective medium and aliquot into a 96-well plate (100 μL per well) [7].

- Incubation: Incubate with vigorous agitation at 37°C for several hours to allow population growth and plasmid loss events to occur.

- Selection and Counting: Add chloramphenicol (or other appropriate selective agent) to each well to select for plasmid-containing cells. Determine the fraction of wells without growth, which indicates wells where plasmid loss occurred in the founding population [7].

- Calculation: Use fluctuation analysis principles to calculate the inherent plasmid loss rate from the distribution of plasmid-free cells across the wells.

Alternative Microscopy-Based Method:

- Culture and Resuspension: Grow plasmid-containing cells in selective medium to OD600 ≈ 0.3, centrifuge, and resuspend in non-selective medium [7].

- Imaging: At 5-minute intervals, spot 5 μL of culture onto selective low-melt agarose pads on microscope slides [7].

- Analysis: After incubation, image microcolonies and manually count single lysed cells (plasmid-free) versus growing microcolonies (plasmid-containing) to determine immediate loss frequencies at extremely short time scales [7].

Technical Considerations: Traditional plasmid loss assays can overestimate loss rates due to growth advantages of plasmid-free cells. These modified approaches separate inherent loss events from growth differences, providing more accurate measurements [7]. For many plasmids, loss rates may be much lower than previously believed, suggesting the existence of unknown stabilization mechanisms that improve copy number control or partitioning at cell division [7].

Restriction Digestion for Plasmid Analysis

Restriction enzyme digestion is a fundamental technique for plasmid verification, cloning, and analysis [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified plasmid DNA

- Appropriate restriction enzymes

- Compatible restriction buffer

- BSA (if recommended by manufacturer)

- Gel loading dye

- Electrophoresis equipment and reagents

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a 1.5 mL tube, combine:

- 1 μg plasmid DNA (for cloning) or 500 ng (for diagnostic digest)

- 1 μL of each restriction enzyme

- 3 μL 10x buffer

- 3 μL 10x BSA (if recommended)

- Nuclease-free water to 30 μL total volume [12]

- Incubation: Mix gently by pipetting and incubate at the appropriate temperature (usually 37°C) for 1 hour to overnight, depending on application [12].

- Analysis: Add gel loading dye and analyze digestion products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For double digests (two enzymes), use compatibility charts to determine optimal buffer [12].

- If enzymes don't cut, check for methylation sensitivity (Dam/Dcm methylases can block certain sites) [12].

- Use phosphatase treatment (CIP or SAP) for vectors in cloning to prevent recircularization [12].

- Avoid star activity (cleavage at non-canonical sites) by minimizing glycerol concentration and following manufacturer recommendations [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Plasmid Engineering and Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Competent Cells | DNA uptake for transformation | Efficiency ranges from 10⁶-10⁹ CFU/μg; choose based on application [13] |

| Electrocompetent Cells | High-efficiency transformation via electroporation | Essential for large plasmids (>10 kb) or BACs [3] |

| Universal MCS Vectors | Standardized cloning platforms | Enable automation-friendly cloning with consistent homologous linkers [14] |

| recA-deficient E. coli Strains | Enable in vivo assembly | Facilitate RecA-independent recombination for simplified cloning [14] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | PCR amplification with minimal errors | Essential for ORI mutagenesis and vector construction [14] |

| Antibiotic Selection Media | Maintain plasmid retention | Critical for preventing plasmid loss; be aware of stability issues with ampicillin [8] |

Visualizing Plasmid Engineering Workflows

Plasmid Component Relationships

Diagram 1: Plasmid functional relationships. The origin of replication (ORI) controls copy number, which influences expression levels, metabolic load, and stability. Selectable markers enable antibiotic resistance, creating selective pressure for plasmid maintenance. MCS (Multiple Cloning Site) provides cloning flexibility for inserting genes of interest.

Plasmid Copy Number Engineering Workflow

Diagram 2: Directed evolution workflow for plasmid copy number engineering. This pipeline uses growth-coupled selection to identify ORI mutations that increase copy number, followed by screening in plant systems to validate improved transformation efficiency [9].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The strategic engineering of plasmid components continues to enable advances across biotechnology. In Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (AMT), binary vector copy number directly impacts transformation efficiency in both plant and fungal systems [9]. Recent work demonstrates that engineered high-copy-number variants of broad-host-range origins (pVS1, RK2, pSa, BBR1) can significantly improve transient and stable transformation efficiencies [9]. This approach provides an easily deployable framework for improving transformation in recalcitrant species that remain challenging targets for genetic engineering.

In industrial protein production, plasmid copy number control is critical for optimizing yields while maintaining genetic stability. Low-copy-number plasmids like pBR322 derivatives (typically 15-20 copies/cell) often provide superior stability for large-scale fermentations, while high-copy-number pUC derivatives (500-700 copies/cell) can maximize expression for research applications [11]. The development of tunable copy number systems represents an important frontier in metabolic engineering, where precise control of gene expression levels is needed to optimize pathway fluxes without overburdening host metabolism.

Emerging techniques in automation-friendly cloning using universal multiple cloning sites (MCS) and bacterial in vivo assembly are simplifying plasmid construction while maintaining high efficiency and fidelity [14]. These approaches leverage RecA-independent recombination pathways in E. coli, allowing direct transformation of linearized vectors with PCR-amplified inserts without in vitro ligation [14]. Optimization of homologous linker length (12-15 bp) and insert-to-vector ratios (5:1 molar ratio) enables highly efficient assembly with positive clone rates exceeding 95% [14], significantly accelerating plasmid engineering workflows for high-throughput applications.

As synthetic biology advances, the critical role of well-characterized plasmid origins of replication and selectable markers will continue to grow, enabling more precise genetic engineering across diverse host systems from bacteria to plants and fungi. The continued refinement of these fundamental genetic elements promises to overcome current bottlenecks in transformation efficiency, genetic stability, and predictable gene expression.

What are Competent Cells? Enhancing DNA Uptake Efficiency

Competent cells are bacterial cells that have been specially treated to permit the efficient uptake of foreign DNA from the environment, a process fundamental to molecular cloning and genetic engineering [15]. In nature, some bacteria possess natural competence, a genetically programmed ability to take up DNA, as first demonstrated by Frederick Griffith in 1928 with Streptococcus pneumoniae [16]. However, common laboratory bacteria such as Escherichia coli do not possess this natural ability and require artificial methods to become competent [17]. The advent of artificial competence, beginning with the calcium chloride method developed by Mandel and Higa in 1970, revolutionized molecular biology by enabling researchers to introduce recombinant DNA into bacterial hosts for amplification and study [16].

The principle behind artificial competence involves altering the permeability of the bacterial cell wall and membrane to allow the passage of large, negatively charged DNA molecules [15]. Chemical methods typically use divalent cations such as Ca²⁺ to neutralize the charges on both the DNA backbone and the cell membrane, facilitating DNA binding to the cell surface [18] [19]. A subsequent heat shock creates a thermal imbalance that further increases membrane permeability, allowing DNA to enter the cell [15]. Alternatively, electroporation uses a high-voltage electrical pulse to create transient pores in the cell membrane through which DNA can enter [18]. The efficiency of this transformation process is critical for success in many applications, including DNA library construction, cloning of multiple fragments, and the handling of large plasmids [20].

Quantitative Analysis of Transformation Efficiency

Transformation efficiency (TE) is the gold standard metric for evaluating competent cell performance, expressed as colony-forming units per microgram of DNA (CFU/μg DNA) [20]. Achieving high TE is essential for demanding applications where the number of successful transformants is low.

Comparison of Transformation Methods

The choice of transformation method significantly impacts the efficiency and success of DNA uptake. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the most common methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Bacterial Transformation Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Transformation Efficiency (CFU/μg) | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Transformation (Heat Shock) | Chemical treatment (e.g., CaCl₂) and brief heat pulse to increase membrane permeability [18] [15]. | (1.0 \times 10^5) – (2.0 \times 10^9) [18] | Simple protocol, requires only a water bath, cost-effective [18]. | Lower efficiency compared to electroporation for some applications [18]. |

| Electroporation | A brief high-voltage electrical pulse creates transient pores in the cell membrane [18]. | (5.0 \times 10^9) – (2.0 \times 10^{10}) [18] | Highest achievable efficiency, faster process [18]. | Requires specialized (expensive) equipment, samples must be salt-free to prevent arcing [18]. |

| TSS-HI Method | A simplified chemical method combining advantages of TSS, Hanahan, and Inoue methods [20]. | Up to ((7.21 \pm 1.85) \times 10^9) [20] | Simplicity and extremely high efficiency for a chemical method [20]. | Optimization may be required for different bacterial strains [20]. |

Strain and Method Selection for Optimal Efficiency

The genetic background of the E. coli strain and the specific preparation protocol are critical determinants of TE. Research has demonstrated that no single method is optimal for all strains.

Table 2: Optimization of Transformation Methods for Common E. coli Strains

| E. coli Strain | Recommended Method | Reported Transformation Efficiency (CFU/μg) | Strain Characteristics and Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DH5α | Hanahan's Method [17] | > (1 \times 10^9) [20] | General cloning; endA1 mutation for high-quality plasmid DNA, recA1 to reduce recombination [16]. |

| BL21 (DE3) | CaCl₂ Method [17] | Information missing | Recombinant protein expression; lacks lon and ompT proteases, carries T7 RNA polymerase gene [16]. |

| BW3KD | TSS-HI Method [20] | ((7.21 \pm 1.85) \times 10^9) [20] | Derived from BW25113; high TE, fast growth, deletions in endA, fhuA, and deoR for improved cloning [20]. |

| XL-1 Blue | Hanahan's Method [17] | Information missing | General cloning and phage display applications. |

| TOP10 | CaCl₂ Method [17] | Information missing | General cloning; high transformation efficiency and stable replication of large plasmids. |

Factors Affecting Transformation Efficiency

Multiple variables during the preparation and transformation of competent cells can dramatically impact the resulting efficiency.

- Growth Phase of Bacteria: Cells harvested during the mid-logarithmic growth phase (OD600 of approximately 0.4-0.5) are metabolically active and yield the highest competence [18] [17].

- Temperature Control: Maintaining cells constantly on ice during chemical treatment is crucial. Low temperature helps maintain membrane permeability and prevents the loss of competence [18].

- Heat-Shock Conditions: The duration and temperature of the heat shock are critical. While a 45-second shock is often used, optimal times can vary [17].

- Storage and Handling: Competent cells must be stored at -80°C and never refrozen after thawing, as temperature fluctuations cause a dramatic decrease in transformation efficiency [18]. Proper storage allows cells to remain viable for at least one year [18].

- Recovery Time: Following transformation, an incubation period in a nutrient-rich, non-selective medium (e.g., SOC or LB broth) allows cells to recover, express the antibiotic resistance marker, and restore their cell walls [18].

Advanced Protocol: TSS-HI Method for High-Efficiency Transformation

The TSS-HI method represents a significant advance in preparing highly competent cells with a simpler protocol [20].

Reagent Preparation

- LB Broth: Standard Lennox formulation (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl).

- TSS-HI Solution: 10% (w/v) Polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350, 5% Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 20 mM MgCl₂, 20 mM MgSO₄, 40 mM Potassium acetate (pH 7.5), 90 mM MnCl₂, 10 mM CaCl₂, 0.1 M KCl, 3 mM Hexamminecobalt(III) chloride, adjusted to pH 6.1 with HCl and filter-sterilized. Store in aliquots at -20°C.

- KCM Solution: 0.1 M KCl, 30 mM CaCl₂, 50 mM MgCl₂. Autoclave and store at room temperature.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Inoculation and Growth: Streak the E. coli strain (e.g., BW3KD) onto a fresh LB agar plate and incubate overnight at 37°C. Pick a single colony and inoculate 5 mL of LB broth, incubating overnight with shaking at 37°C and 200-220 rpm. The next day, dilute 1 mL of the overnight culture into 99 mL of pre-warmed LB in a flask (1:100 dilution). Grow with vigorous shaking until the OD600 reaches 0.55 [20].

- Harvesting and Washing: Chill the culture flask on ice for 15-20 minutes. Centrifuge the cells at 3200 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Gently decant the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in 1/20 of the original volume (e.g., 5 mL for a 100 mL culture) of ice-cold TSS-HI solution.

- Aliquoting and Freezing: Dispense the cell suspension into pre-chilled microcentrifuge tubes (e.g., 100 µL aliquots). Flash-freeze the aliquots immediately in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C. Properly stored, these competent cells remain stable for at least one year [18].

- Transformation: Thaw a 100 µL aliquot of competent cells on ice. Add 1-10 ng of plasmid DNA (in a volume not exceeding 5 µL) and 10 µL of KCM solution. Mix gently by flicking the tube and incubate on ice for 30 minutes. Subject the mixture to a heat shock in a water bath at 42°C for 45-90 seconds. Immediately return the tube to ice for 2 minutes.

- Recovery and Plating: Add 900 µL of room-temperature SOC or LB broth to the tube. Incubate with shaking at 37°C for 45-60 minutes to allow for antibiotic resistance expression. Plate appropriate volumes onto selective agar plates and incubate overnight at 37°C.

Diagram 1: Competent Cell Preparation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Competent Cell Preparation

| Reagent Solution | Composition | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | 0.1 M CaCl₂, often with 15% glycerol [17]. | The foundational chemical method; Ca²⁺ ions neutralize charge repulsion between DNA and cell membrane [15] [17]. |

| Hanahan's FSB Buffer | Complex mixture including MnCl₂, CaCl₂, KCl, Hexamminecobalt(III) chloride, and DMSO [17]. | A multi-component buffer designed for ultra-high efficiency transformation of specific strains like DH5α [17]. |

| TSS Solution | LB broth (pH 6.1), PEG 3350, DMSO, MgCl₂, MgSO₄ [20] [17]. | A simple, one-step chemical method that can achieve high transformation efficiencies without the need for heat shock in its original form [17]. |

| Glycerol Solution (10%) | 10% v/v glycerol in ultrapure water [18]. | Used as a cryoprotectant for preparing electrocompetent cells; it replaces salts to prevent arcing during electroporation [18]. |

| SOC Recovery Medium | A nutrient-rich broth containing glucose and additional ions. | Provides essential nutrients for cell wall repair and allows expression of antibiotic resistance genes after heat shock or electroporation [17]. |

Competent cells are an indispensable tool in modern molecular biology and biotechnology. Understanding the principles behind DNA uptake and the variables that influence transformation efficiency allows researchers to select the appropriate strain, method, and protocol for their specific application. The continued optimization of protocols, such as the development of the TSS-HI method achieving efficiencies rivaling electroporation with the simplicity of a chemical method, ensures that researchers can tackle increasingly complex cloning challenges. By adhering to optimized protocols and paying meticulous attention to factors like growth phase, temperature control, and storage conditions, scientists can reliably produce highly competent cells that form the foundation of successful genetic manipulation workflows.

Within the framework of bacterial transformation protocol research for E. coli, the selection of an appropriate DNA delivery method is a critical determinant of experimental success. Transformation, the process of introducing foreign DNA into a host cell, relies on overcoming the fundamental barrier of the cell's plasma membrane [21]. For the widely used E. coli model system, two primary techniques—chemical transformation and electroporation—have been established as the most effective and commonly used methods [22] [23]. This application note delineates the fundamental mechanisms of DNA entry for both chemical and electroporation methods, providing a structured comparison of their capabilities. It further offers detailed, actionable protocols to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting and optimizing the ideal transformation strategy for their specific applications, from routine cloning to complex library construction. Understanding the distinct principles underpinning each method is essential for maximizing transformation efficiency, a key metric in molecular cloning workflows.

Fundamental Mechanisms of DNA Entry

The journey of exogenous DNA into an E. coli cell requires a temporary and reversible alteration of the cell membrane's permeability. While the end goal is identical, the physical and chemical principles exploited to achieve this differ profoundly between the two methods.

Chemical Transformation (Heat Shock)

Chemical transformation, also referred to as heat shock or calcium chloride transformation, utilizes a combination of chemical and thermal stimuli to facilitate DNA uptake [22] [23]. The process begins with the preparation of competent cells—harvested during the mid-log phase of growth (OD₆₀₀ between 0.4 and 0.9) to ensure optimal physiological state [23]. These cells are then incubated in a solution containing divalent cations, most commonly calcium chloride (CaCl₂).

The mechanism is multi-faceted. The Ca²⁺ ions are thought to neutralize the negative charges on both the DNA backbone and the bacterial cell membrane, reducing electrostatic repulsion and promoting DNA adhesion to the cell surface [22] [24]. This incubation is performed on ice to stabilize this complex. The subsequent heat shock—a brief, sudden elevation in temperature to 42°C for 30-60 seconds—creates a thermal current and induces fluidity in the membrane's lipid bilayer. This temporary phase transition is believed to form transient pores or channels, allowing the bound DNA to enter the cell via diffusion or convection [22] [23]. Following the heat shock, the cells are immediately returned to ice to reseal the membrane.

Electroporation

Electroporation relies purely on a physical force to drive DNA into cells. This method involves subjecting a mixture of cells and DNA to a brief, high-intensity electrical pulse [21] [22]. The preparation of cells for electroporation, termed electrocompetent cells, requires extensive washing with ice-cold deionized water or a low-conductivity buffer like 10% glycerol [23]. This critical step removes salts from the medium, which would otherwise conduct electricity and cause arcing (an electrical discharge), thereby reducing cell viability and transformation efficiency [22] [23].

The fundamental mechanism involves the application of an electric field across the cell suspension, typically in a specialized cuvette with a gap of 0.1 to 0.2 cm. When a high-voltage pulse (with a field strength of >15 kV/cm for bacteria) is applied, it induces a transient transmembrane potential [23]. This potential difference causes the polar phospholipid heads of the membrane to realign, forming hydrophilic pores that are thought to be nanometers in diameter [21] [22]. Because the DNA is negatively charged, the electric field then drives the molecules through these pores into the cell via electrophoresis [22]. The pores are transient and reseal spontaneously once the electric field is dissipated, trapping the DNA inside the cell.

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the key procedural differences between these two methods.

Comparative Analysis & Application Selection

The choice between chemical transformation and electroporation is not merely one of preference but should be guided by the specific requirements of the experimental application. The two methods differ significantly in their efficiency, requisite setup, and optimal use cases.

Table 1: Method Comparison at a Glance

| Feature | Chemical Transformation | Electroporation |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Mechanism | Chemical (cation-based) pore formation & heat shock [22] [23] | Physical (electrical field-induced) pore formation [21] [22] |

| Typical Transformation Efficiency | (1 \times 10^6) to (5 \times 10^9) CFU/µg [25] | (1 \times 10^{10}) to (3 \times 10^{10}) CFU/µg [25] [26] |

| Key Equipment | Water bath or dry bath/block heater [25] | Electroporator and electroporation cuvettes [22] [25] |

| Optimal DNA Amount | 1–10 ng [23] | Low amounts (e.g., 10 pg) to saturating concentrations [25] |

| Critical Parameter | Duration and temperature of heat shock [3] [23] | Electrical field strength and pulse time constant [23] [26] |

| Susceptibility to Issues | Less sensitive to protocol variations [22] | Sensitive to salt content, can cause arcing [22] [23] |

Table 2: Guideline for Application-Based Method Selection

| Research Application | Recommended Method | Justification & Required Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Routine Cloning & Subcloning | Chemical Transformation | Sufficient efficiency ((10^6)-(10^8) CFU/µg); simplicity and cost-effectiveness [25] |

| cDNA/genomic DNA Library Construction | Electroporation | Requires highest efficiency ((>10^{10}) CFU/µg) to represent large diversity [25] |

| Large Plasmid Transformation (>30 kb) | Electroporation | More effective at introducing large DNA molecules [3] [25] |

| High-Throughput Workflows | Chemical Transformation | Adaptable to 96-well plates and automated formats [25] |

| Transformation of Other Microbial Species | Electroporation | Broader range, including bacteria with cell walls [25] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Chemical Transformation ofE. colivia Heat Shock

This protocol is adapted from standard laboratory practices and manufacturer guidelines [3] [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Competent Cells: Chemically competent E. coli (e.g., DH5α, XL1-Blue). Prepared by CaCl₂ treatment or purchased commercially.

- SOC Media: Contains nutrients and MgCl₂ to maximize transformation efficiency during recovery [23].

- LB Agar Plates: Containing the appropriate selective antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin, kanamycin).

- Plasmid DNA: Supercoiled plasmid DNA, such as pUC19, for transformation control.

- Thawing Competent Cells: Gently thaw 50–100 µL of chemically competent E. coli cells on ice.

- DNA Addition: Add 1–10 ng of plasmid DNA (or 1–5 µL of a ligation mixture) directly to the thawed cells. Mix gently by tapping the tube. Do not vortex.

- Incubation on Ice: Incubate the cell-DNA mixture on ice for 20–30 minutes.

- Heat Shock: Transfer the tube to a preheated 42°C water bath for exactly 30 seconds. Do not shake.

- Recovery on Ice: Immediately return the tube to ice for at least 2 minutes.

- Outgrowth: Add 250–500 µL of pre-warmed SOC media to the tube. Shake at 37°C for 45–60 minutes at 225 rpm.

- Plating: Plate 50–200 µL of the transformation culture onto pre-warmed LB agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotic.

- Incubation: Incubate plates overnight at 37°C.

Protocol 2: High-Efficiency Transformation ofE. colivia Electroporation

This protocol is based on established methodologies for high-efficiency transformation [23] [26] [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Electrocompetent Cells: E. coli strain (e.g., DH10B, MC4100) washed in 10% glycerol [23] [27].

- Electroporation Buffer: Ice-cold 10% glycerol or similar low-ionic-strength buffer.

- SOC Media: For immediate recovery post-pulse.

- LB Agar Plates: Containing the appropriate selective antibiotic.

- Preparation of Cells: Thaw electrocompetent cells on ice. Alternatively, use freshly prepared, ice-cold electrocompetent cells.

- DNA and Cell Mixing: Add 1 µL of plasmid DNA (10 pg–100 ng) to 20–50 µL of electrocompetent cells in a pre-chilled electroporation cuvette (0.1 cm gap). Mix gently by pipetting. Ensure the sample is free of bubbles and at the bottom of the cuvette.

- Electroporation: Place the cuvette in the electroporator chamber and deliver a single pulse. Typical parameters for E. coli are 1.8–2.5 kV, 200 Ω, and 25 µF, resulting in a time constant of ~4–5 ms [26] [27].

- Immediate Recovery: Immediately after the pulse, add 0.5–1 mL of pre-warmed SOC media directly to the cuvette. Transfer the cell suspension to a sterile culture tube.

- Outgrowth: Incubate the culture at 37°C with shaking at 225 rpm for 45–60 minutes.

- Plating and Incubation: Plate appropriate volumes onto selective LB agar plates and incubate overnight at 37°C.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful transformation is dependent on the quality and appropriateness of the reagents and materials used. The following table details key components for a successful transformation workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bacterial Transformation

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Competent Cells | E. coli strains treated to uptake foreign DNA. | Select strain based on genotype (e.g., endA1 for high-quality plasmid prep, recA for unstable inserts) [25]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Primary chemical for creating chemically competent cells; neutralizes charge repulsion [23]. | Use high-purity, ice-cold solutions. Can be supplemented with other cations (Rb⁺, Mn²⁺) for higher efficiency [23]. |

| SOC Media | Rich recovery medium containing glucose and MgCl₂. | Significantly increases transformation efficiency (2–3 fold) compared to LB during outgrowth [23]. |

| Electroporation Cuvettes | Disposable cuvettes with specific gap widths (e.g., 0.1 cm, 0.2 cm) to deliver precise electric fields. | Must be clean, dry, and ice-cold. The gap width determines the required field strength (V/cm) [23]. |

| Selective Agar Plates | LB agar supplemented with antibiotic for selectable marker-based screening of transformants. | Antibiotic must be active; use fresh plates to avoid satellite colonies from degraded antibiotic [23]. |

| pUC19 Control Plasmid | Small, supercoiled, high-copy-number plasmid. | Used as a control to determine the transformation efficiency (CFU/µg) of competent cell batches [23] [25]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | A reducing agent. | Sometimes added to chemical transformation protocols to further improve efficiency [23]. |

The strategic selection between chemical transformation and electroporation is a cornerstone of efficient molecular biology research involving E. coli. Chemical transformation, with its straightforward protocol and minimal equipment needs, remains the workhorse for routine cloning applications. In contrast, electroporation offers a substantial advantage in transformation efficiency, making it indispensable for challenging applications such as library construction and the transformation of large DNA fragments. The detailed mechanisms, comparative data, and robust protocols outlined in this application note provide a foundational resource for researchers to make an informed decision, optimize their experimental parameters, and ultimately accelerate their research and development pipeline in drug discovery and basic science.

Within molecular biology and biotechnology, the successful transformation of Escherichia coli is a foundational procedure. It is essential for cloning, protein expression, and genetic engineering [28]. While standard protocols exist, achieving high efficiency, particularly with challenging constructs, depends critically on three interlinked factors: the size of the plasmid, the genetic background of the bacterial strain, and the physiological health of the competent cells. This application note details the influence of these factors and provides optimized protocols to maximize transformation success for researchers and drug development professionals.

Strain Genetics: The Foundational Element

The choice of E. coli strain is not arbitrary; its genotype must be strategically matched to the experimental goal, whether it be routine cloning, propagation of large plasmids, or protein expression.

Table 1: Selection of E. coli Strains for Specific Applications

| Application | Recommended Strains | Key Genetic Features | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Efficiency Cloning | BW3KD, DH5α, TOP10 | endA1, deoR (in BW3KD), recA1 |

endA1 mutation inactivates an endonuclease that degrades plasmid DNA during purification. deoR facilitates the transformation of large plasmids [20]. |

| Large Plasmid/BAC Propagation | BW3KD, XL1-Blue MRF′ | deoR deletion, recA1 |

Mutations like deoR overcome the inefficiency in transforming large plasmids (>50 kbp) [29] [20]. |

| Protein Expression | BL21(DE3) and derivatives | lon, ompT, T7 RNA polymerase |

Deficiencies in Lon and OmpT proteases minimize target protein degradation. The T7 expression system enables strong, IPTG-inducible expression [30]. |

| Methylated DNA Cloning | STBL2, SCS110 | mcrA, mcrBC, mrr |

Mutations in methylation-dependent restriction systems prevent cleavage of genomic DNA methylated at cytosine residues [30]. |

| Toxic Gene Expression | BL21(DE3)pLysS, BL21(DE3)pLysE | T7 lysozyme gene on pLys plasmid | T7 lysozyme suppresses basal expression from the T7 promoter by inhibiting T7 RNA polymerase, allowing propagation of toxic genes [30]. |

Strain Genotype Deep Dive

- Restriction Systems: Wild-type K-12 strains possess the EcoKI Type I restriction-modification system (

hsdRMS). Strains withhsdRmutations (r–, m+) are preferred for cloning unmethylated DNA (e.g., PCR products) as they cannot restrict it [30]. - Methylation Considerations: For routine cloning, standard strains are sufficient. However, if using restriction enzymes sensitive to adenine or cytosine methylation, one should use

dam/dcmdeficient strains. Conversely, for cloning eukaryotic DNA, strains deficient in the McrA, McrBC, and Mrr systems are necessary to avoid restriction of methylated cytosine [30].

Plasmid Size: A Critical Determinant of Efficiency

Transformation efficiency (TE) is highly dependent on plasmid size, with a dramatic inverse correlation observed.

Table 2: Impact of Plasmid Size on Transformation Efficiency

| Plasmid Type | Approximate Size (kbp) | Relative Transformation Efficiency | Recommended Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Cloning Vector | 3 - 5 | Very High (e.g., >10⁹ CFU/µg) | Chemical Transformation [3] |

| Large Plasmid | 10 - 50 | High to Moderate | Chemical Transformation or Electroporation |

| Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) | >50 | Very Low (requires optimization) | High-Efficiency Electroporation [29] |

| Assembled Product (e.g., Gibson) | Variable | Often Low (multiple orders of magnitude drop) | High-Efficiency Chemical Cells [20] |

Research indicates that the transformation efficiency for a 120 kbp BAC plasmid can be optimized to reach up to 7 × 10⁸ transformants/µg using specialized electroporation protocols, highlighting that method optimization can partially overcome the physical barriers to large DNA uptake [29].

Cellular Health and Transformation Workflow

The preparation of highly competent cells is a sensitive process where physiological state and handling are paramount. The following workflow and protocol ensure maximum viability and transformation efficiency.

Optimized High-Efficiency Chemical Transformation Protocol

This protocol, incorporating elements from the TSS-HI method [20] and other established sources [23] [17] [3], is designed for high transformation efficiency with standard plasmids.

Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit)

- Recombinant Plasmid DNA: 1-10 ng for high-efficiency cells.

- E. coli Strain: Select based on application (see Table 1).

- Growth Media: LB, SOB, or SOC (SOC is preferred for outgrowth).

- Transformation Buffers: Ice-cold CaCl₂ solution or specialized buffers like TSS or FSB.

- Antibiotics: For selective plating.

- Equipment: Water bath (42°C), shaking incubator (37°C), ice bucket, sterile tubes and plates.

Methodology

- Competent Cell Thawing: Thaw 50-100 µL of competent cells (prepared in-house or commercial) on ice [23] [3].

- DNA Addition: Gently mix cells with 1-10 ng of plasmid DNA. Do not vortex. Incubate on ice for 20-30 minutes [3].

- Heat Shock: Transfer the tube to a preheated 42°C water bath for 45 seconds. The optimal duration can vary from 30-90 seconds depending on the strain and method [17] [20].

- Recovery: Immediately return the tube to ice for 2 minutes [3].

- Outgrowth: Add 250-1000 µL of pre-warmed SOC medium [23]. Shake at 37°C for 45-60 minutes to allow expression of the antibiotic resistance gene [3].

- Plating: Plate an appropriate volume onto pre-warmed LB agar plates containing the selective antibiotic. Incubate at 37°C overnight [23].

Integrated Optimization Strategies

For maximum transformation efficiency, a holistic approach that considers all factors is required.

Method Selection: Chemical vs. Electroporation

- Chemical Transformation: Simpler, requires no specialized equipment, and is ideal for routine cloning with small to medium-sized plasmids. Efficiency for supercoiled plasmids can exceed 10⁹ CFU/µg with optimized methods like TSS-HI [20].

- Electroporation: Generally yields higher efficiencies (up to 10¹⁰ CFU/µg for supercoiled plasmids) and is strongly recommended for large plasmids (>10 kbp) and BACs [3] [29]. It requires electrocompetent cells, which are washed in low-ionic-strength buffers to prevent arcing [23].

Protocol for Large Plasmids and BACs

Electrotransformation is the method of choice for large constructs [29]. Key optimizations include:

- Cell Preparation: Grow cells at a lower temperature (e.g., 25-30°C) and use specific media supplements to enhance competency for large DNA uptake [29].

- Washing Buffer: Use ice-cold deionized water or 10% glycerol to remove all salts from the electrocompetent cells [23].

- Electroporation Parameters: Use a high field strength (>15 kV/cm) with a 0.1 cm cuvette and an exponential decay pulse [23].

- DNA Handling: Use high-quality, concentrated DNA to minimize volume. Avoid excessive handling to prevent shearing.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- No Transformants: Verify the antibiotic is active and the resistance marker on the plasmid matches. Include a positive control plasmid [3].

- Low Efficiency with Assembled DNA: DNA from assembly reactions (e.g., Gibson, Golden Gate) often transforms poorly. Using rolling circle amplification (RCA) followed by nicking can yield a >6,500-fold increase in transformed colonies [31].

- Satellite Colonies: Avoid prolonged incubation (>16 hours). Satellite colonies are antibiotic-sensitive and form around true transformants due to antibiotic degradation [23].

Achieving robust and efficient bacterial transformation in E. coli requires a meticulous, integrated strategy. Researchers must select a host strain whose genetics are tailored to the application, acknowledge and address the inherent challenges of transforming large plasmids, and adhere to protocols that prioritize cellular health throughout the competency and transformation process. By systematically optimizing these key factors—plasmid size, strain genetics, and cellular health—scientists can significantly enhance the reliability and throughput of their molecular cloning workflows, accelerating discovery and development in biotechnology and pharmaceutical research.

Step-by-Step Transformation Protocols: Heat Shock, Electroporation, and Best Practices

Chemical transformation followed by heat shock is a foundational technique in molecular biology for introducing plasmid DNA into Escherichia coli (E. coli). This process creates "competent" bacterial cells capable of taking up exogenous DNA from their environment. The principle relies on a chemical pretreatment, typically with calcium chloride, to neutralize charge repulsions between the bacterial cell surface and the DNA, followed by a brief thermal shock to facilitate DNA uptake [32] [33]. The success of this method is highly dependent on several factors, including the specific E. coli strain, the chemical method used for inducing competence, and the precise execution of the heat shock step [17]. Within the broader context of a thesis on bacterial transformation, this protocol details the standardized methodology for achieving high-efficiency transformation, a critical step in cloning, protein expression, and genetic engineering workflows for researchers and drug development professionals.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines the essential reagents and their specific functions in the chemical transformation workflow.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Chemical Transformation

| Reagent | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | A divalent cation that neutralizes the negative charges on the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of the bacterial outer membrane and the DNA backbone, reducing electrostatic repulsion and allowing DNA to adhere to the cell surface [34] [32]. |

| SOC Medium (Super Optimal broth with Catabolite repression) | A nutrient-rich recovery media used after heat shock. It provides essential metabolites and a controlled osmotic environment, allowing the bacteria to recover and express the antibiotic resistance gene encoded on the plasmid before being placed on selective plates [35] [32]. |

| Glycerol | Added to the final competent cell suspension as a cryoprotectant, enabling long-term storage of the prepared competent cells at -80°C without significant loss of viability or transformation efficiency [17] [32]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Used in some transformation buffers (e.g., DMSO method) to promote the aggregation of DNA and its precipitation onto the cell membranes, thereby increasing the local DNA concentration available for uptake [17]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | A membrane fluidizer used in some high-efficiency protocols (e.g., Hanahan's method) to help disrupt the cell membrane, potentially facilitating the passage of DNA during the heat shock step [17]. |

Optimizing transformation efficiency (TE), measured in colony-forming units per microgram of DNA (CFU/μg), is crucial for experiments involving limited DNA or complex cloning steps. The data below summarize key factors influencing TE.

Table 2: Comparison of Chemical Transformation Methods Across Common E. coli Strains Data adapted from a systematic comparison of four chemical methods [17]

| E. coli Strain | Optimal Transformation Method | Significant Media Effect? (SOB vs. LB) |

|---|---|---|

| DH5α | Hanahan's Method | No significant effect |

| XL-1 Blue | Hanahan's Method | Enhanced with SOB |

| JM109 | Hanahan's Method | Dampened with SOB |

| SCS110 | CaCl₂ Method | No significant effect |

| TOP10 | CaCl₂ Method | No significant effect |

| BL21(DE3) | CaCl₂ Method | No significant effect |

Table 3: Transformation Efficiency Benchmarks and Influential Parameters Efficiency benchmarks from [36]; Heat shock data from [17] [34]

| Parameter | Impact on Transformation Efficiency (TE) |

|---|---|

| Transformation Efficiency Benchmark | >10⁸ CFU/μg (Excellent); 10⁷-10⁸ CFU/μg (Good); 10⁶-10⁷ CFU/μg (Fair); <10⁶ CFU/μg (Poor) [36] |

| Heat Shock Duration | No significant difference in TE was found between 45 s and 90 s heat shock across multiple strains [17]. |

| Storage Temperature of Competent Cells | Fresh competent cells stored at 4°C demonstrated higher TE compared to those stored frozen at -80°C [34]. |

| DNA Amount | Using an excessive amount of DNA can saturate the system and lower efficiency. For highly competent cells, less DNA (e.g., 1-10 pg to 100 ng) often yields higher TE [3] [35]. |

Experimental Workflow and Procedure

The following diagram illustrates the complete chemical transformation protocol, from cell preparation to the analysis of results.

Diagram 1: Complete workflow for chemical transformation of E. coli.

Detailed Protocol Steps

Part I: Preparation of Chemically Competent E. coli DH5α (Adapted Calcium Chloride Method) [35] [32]

- Duration: Approximately 4-6 hours.

- Critical Note: All steps must be performed aseptically and kept on ice or at 4°C unless specified.

- Starter Culture: From a freshly streaked LB agar plate, inoculate a single colony of E. coli DH5α into 2-5 mL of LB broth. Grow overnight (16-20 hours) at 37°C with vigorous shaking (200-250 rpm).

- Dilution and Growth: Inoculate 100 mL of pre-warmed LB broth in a 1L flask with the overnight culture to an initial OD₆₀₀ of 0.01-0.05. Incubate at 37°C with vigorous shaking (210 rpm) until the culture reaches mid-exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ = 0.35-0.5). This typically takes about 3 hours. Note: Cells must be in this growth phase for optimal competence.

- Chilling: Transfer the culture to ice-cold polypropylene centrifuge bottles. Incubate on ice for 20 minutes to halt bacterial growth.

- Pellet and Wash: Pellet the cells by centrifugation at 2,700-5,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Carefully decant the supernatant.

- Gently resuspend the pellet in 30 mL of ice-cold CaCl₂-MgCl₂ solution (80 mM MgCl₂, 20 mM CaCl₂). Avoid vortexing.

- Incubate the resuspended cells on ice for 15-30 minutes.

- Final Resuspension: Pellet the cells again as in step 4. Carefully decant the supernatant.

- Gently resuspend the pellet in 4 mL of ice-cold 0.1 M CaCl₂ solution containing 10% (v/v) glycerol. Use a chilled pipette for this step.

- Aliquoting and Storage: Dispense 50-100 μL aliquots of the cell suspension into pre-chilled, sterile microcentrifuge tubes. Flash-freeze the aliquots in a dry-ice/ethanol bath or liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C for future use.

Part II: Transformation of Competent Cells via Heat Shock [3] [35] [37]

- Duration: Approximately 2 hours.

- Thawing: Remove a vial of competent cells from -80°C and thaw on ice for 20-30 minutes.

- DNA Addition: Add 1-5 μL of plasmid DNA (10 pg to 100 ng) directly to the thawed competent cells. Do not vortex. Gently mix by flicking the tube. Incubate the mixture on ice for 30 minutes.

- Pro-Tip: For high-efficiency cells, using less DNA (e.g., a 1:5 or 1:10 dilution) can sometimes yield higher transformation efficiencies [3].

- Heat Shock: Transfer the tube to a pre-heated 42°C water bath for exactly 30-45 seconds. Do not shake or agitate the tube. The optimal duration may vary slightly between cell preparations [17] [38].

- Immediate Cooling: Immediately return the tube to ice for 2 minutes.

- Recovery: Add 250-1000 μL of pre-warmed SOC or LB media to the tube. Incubate at 37°C for 45-60 minutes in a shaking incubator (200-250 rpm). This "outgrowth" step allows the bacteria to recover and begin expressing the antibiotic resistance gene on the plasmid.

- Plating: Plate 20-200 μL of the transformation mixture onto pre-warmed LB agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotic. Spread the liquid evenly using a sterile spreader.

- Pro-Tip: If the volume plated is too large, concentrate the cells by centrifuging the transformation mixture, removing the supernatant, resuspending the pellet in a smaller volume of LB (e.g., 100 μL), and then plating the entire volume [37].

- Incubation: Leave the plates upright until the liquid is absorbed, then invert and incubate at 37°C for 16-20 hours.

Data Analysis and Calculation of Transformation Efficiency

After overnight incubation, count the number of colonies on the plate that has a countable number (ideally between 50-300 colonies for accuracy) [36].

Transformation Efficiency (TE) is calculated using the following formula and accounts for all dilution factors [36]:

[ \text{Transformation Efficiency (CFU/μg)} = \frac{\text{Number of Colonies Counted}}{\text{Amount of DNA plated (μg)}} ]

Where:

- Amount of DNA plated (μg) = (Concentration of DNA (ng/μL) × Volume of DNA used (μL) × (Volume of transformation reaction plated (μL) / Total volume of transformation mixture after recovery (μL))) / 1000 (to convert ng to μg).

Example Calculation:

- DNA used: 1 μL of a 10 ng/μL plasmid solution.

- Total transformation mixture volume after adding recovery media: 500 μL.

- Volume of transformation mixture plated: 100 μL.

- Colonies counted: 150.

[ \text{Amount of DNA plated} = (10 \, \text{ng/μL} \times 1 \, \mu\text{L}) \times (100 \, \mu\text{L} / 500 \, \mu\text{L}) / 1000 = 0.002 \, \mu\text{g} ] [ \text{Transformation Efficiency} = 150 \, \text{colonies} / 0.002 \, \mu\text{g} = 75,000 = 7.5 \times 10^4 \, \text{CFU/μg} ]

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- No Colonies: Verify the antibiotic in the plate matches the resistance gene on the plasmid. Check the health of the competent cells using a positive control plasmid. Ensure the heat shock step was performed at the correct temperature and duration [3].

- Low Transformation Efficiency: Ensure cells were kept ice-cold until the heat shock step. Use fresh, high-quality DNA. Avoid over- or under-growing the initial culture. Ensure the recovery media (SOC) is fresh, as glucose is unstable [3] [35].

- Excessive Background (Satellite Colonies): This can occur if the antibiotic in the plate is degraded. Use fresh selective plates. Ensure the antibiotic concentration is correct. For ampicillin, the 1-hour recovery step is less critical but helps reduce background [3].

- Transformation of Large Plasmids (>10 kb): Chemical transformation is less efficient for large plasmids. For higher efficiency with large plasmids or BACs, consider using electroporation as an alternative method [3].

Electroporation is a physical method of bacterial transformation that uses an electrical field to create transient pores in the cell membrane, allowing foreign DNA to enter the cell [39] [40]. This technique is a cornerstone of molecular biology, enabling the introduction of plasmid DNA into Escherichia coli for cloning, protein expression, and genetic engineering. Unlike chemical transformation methods, electroporation is highly efficient and can be used for a wide range of bacterial species, including strains that are difficult to transform using heat shock [39]. The technique is physicochemical, involving the manipulation of cells with cations and electrical currents to make them competent for the uptake of foreign DNA [41]. This protocol details the optimized methodology for the electroporation transformation of E. coli, framed within the broader research on bacterial transformation mechanisms and efficiencies.

Principle of Electroporation

The fundamental principle of electroporation involves subjecting a cell suspension to a high-voltage electrical pulse. This pulse acts on the cell membrane, which functions as an electrical capacitor [40]. The applied field induces a rearrangement of the membrane's lipid structure, leading to the formation of hydrophilic nanopores [42]. When these pores are transient (reversible electroporation), they permit the passage of macromolecules like plasmid DNA into the cell without causing permanent damage. If the electrical parameters are too severe, the pores become permanent, leading to cell death—a state known as irreversible electroporation [43] [42]. For successful transformation, the electrical conditions must be carefully optimized to achieve reversible electroporation, ensuring high DNA uptake while maintaining sufficient cell viability for subsequent recovery and growth [44].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of a standard electroporation transformation procedure:

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential reagents and equipment required for the electroporation transformation protocol.

| Reagent/Equipment | Function and Specification |

|---|---|

| Electrocompetent E. coli Cells | Host cells made permeable to DNA via repeated washing in an inert, cold solution like 10% glycerol [45]. Must be kept at -80°C and handled on ice. |

| Plasmid DNA | Circular DNA construct carrying the gene of interest and a selectable marker (e.g., antibiotic resistance gene). Must be high-quality and free of contaminants [39]. |

| Electroporation Buffer | Typically a low-ionic-strength solution like 10% glycerol or 1M sorbitol [41]. Prevents arcing during the electrical pulse and maintains osmotic stability. |

| SOC Recovery Medium | A rich growth medium containing nutrients that allows transformed cells to recover and express the newly acquired antibiotic resistance genes [17]. |

| Electroporator & Cuvettes | Device that generates controlled electrical pulses. Cuvettes have aluminum electrodes and a precise gap (e.g., 2 mm) to ensure a consistent electric field [40]. |

| Selective Agar Plates | Contain an antibiotic to select for bacterial colonies that have successfully taken up the plasmid [45]. |

Methodology

Preparation of Electrocompetent Cells

- Inoculation and Growth: Inoculate a single colony of the desired E. coli strain into a rich liquid medium (e.g., LB or SOB). Grow the culture overnight at 37°C with vigorous shaking (200-220 rpm) [17].

- Dilution and Log-Phase Growth: Dilute the overnight culture 1:50 to 1:100 into a larger volume of fresh, pre-warmed medium. Incubate with shaking until the cells reach the mid-logarithmic phase of growth, corresponding to an OD600 of 0.4 to 0.6 [45].

- Chilling and Harvesting: Chill the culture flask on ice for 15-30 minutes to halt growth. All subsequent steps should be performed on ice or at 4°C using pre-chilled solutions and centrifuges. Pellet the cells by centrifugation at 3200-4000 × g for 10-15 minutes at 4°C [17].

- Washing: Gently resuspend the cell pellet in a large volume (e.g., half the original culture volume) of ice-cold 10% glycerol or a similar electroporation buffer. Pellet the cells again by centrifugation. Repeat this washing step a total of two or three times to ensure complete removal of ionic salts from the growth medium, which can cause arcing during electroporation [45].

- Aliquoting and Storage: After the final wash, resuspend the cells in a small volume of ice-cold 10% glycerol. Dispense into pre-chilled, sterile microcentrifuge tubes as small aliquots (e.g., 50-100 µL). Flash-freeze the aliquots in a dry-ice/ethanol bath and store at -80°C until use [17].

Electroporation Transformation Procedure

- Thaw Competent Cells: Thaw an aliquot of electrocompetent cells on ice.

- Add DNA: Gently mix 1 µL to 10 µL of plasmid DNA (concentration ~10-100 ng/µL) into the thawed cells. Do not mix by pipetting vigorously. Incubate the DNA-cell mixture on ice for ~1 minute.

- Pulse Application: Transfer the entire mixture to a pre-chilled electroporation cuvette with a 2 mm gap, ensuring the sample covers the bottom and contacts both electrodes. Wipe any condensation from the cuvette. Apply a single electrical pulse using the optimized parameters (see Section 5.1 for details). A typical time constant for a successful pulse is between 4-5 milliseconds [39].

- Immediate Recovery: Immediately after the pulse, add 1 mL of pre-warmed, rich SOC recovery medium directly to the cuvette. Gently pipette to resuspend the cells and transfer the entire suspension to a sterile culture tube.

- Outgrowth: Incubate the recovered cells for 45-60 minutes at 37°C with shaking (200-220 rpm). This outgrowth period allows the bacteria to recover, express the antibiotic resistance gene, and begin plasmid replication [45].

- Plating and Selection: Spread 100-200 µL of the outgrowth culture onto selective agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotic. Incubate the plates inverted overnight at 37°C.

- Analysis: The following day, count the number of transformed colonies to calculate the transformation efficiency.

Optimization and Critical Parameters

Quantitative Optimization Data

Transformation efficiency is highly dependent on several physical and biological parameters. The following table summarizes key optimization data from the literature for E. coli transformation.

| Parameter | Optimal Range / Condition | Effect on Transformation Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Electric Field Strength | 12.5 - 18 kV/cm for E. coli [39] | Must be balanced; too low reduces DNA uptake, too high causes irreversible cell damage. |

| Pulse Length/Time Constant | 4 - 5 ms [39] | A longer time constant indicates successful pore formation and DNA entry. |

| DNA Quantity and Quality | 1 µL - 10 µL (10-100 ng) [39] | High-quality, supercoiled plasmid DNA is critical. Contaminants can reduce efficiency or cause arcing. |

| Cell Preparation | Mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.4-0.6), thorough washing [45] | Actively dividing cells are most competent. Complete salt removal is essential to prevent arcing. |

| Recovery Medium | Rich medium (SOC) [17] | Essential for cell wall repair and expression of antibiotic resistance markers. |

| Strain Dependence | Varies by strain; e.g., Hanahan's method best for DH5α, XL-1 Blue; CaCl₂ method best for TOP10, BL21 [17] | Different E. coli strains have inherent differences in transformation competency and optimal methods. |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Low Transformation Efficiency: Ensure cells are harvested at mid-log phase, washing is thorough to remove all salts, DNA is pure and at an optimal concentration, and the recovery period is sufficient.

- Electrical Arcing: This is often caused by the presence of salts in the cell/DNA mixture. Ensure all buffers are ice-cold and that the cuvette is dry and free of condensation before pulsing.

- Excessive Cell Death: Optimize the electrical parameters (field strength and pulse length). Using too high a voltage or too many pulses can lead to irreversible electroporation.

Applications in Research

Electroporation is a versatile tool with wide-ranging applications in molecular biology and biotechnology. Its primary use is in the cloning of DNA fragments into plasmid vectors for amplification and analysis [45]. It is also indispensable for recombinant protein production, where transformed E. coli are used as cellular factories to express proteins of interest for therapeutic, industrial, or research purposes [39] [45]. Furthermore, electroporation is crucial for modern genetic engineering techniques, including CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, allowing for the precise introduction of editing machinery into bacterial cells [45]. The technique's reliability and high efficiency make it a fundamental procedure in any molecular biology laboratory.

The mechanism of DNA uptake via electroporation and its integration into the host cell's genetic repertoire is summarized in the following pathway:

Within bacterial transformation protocols, the preparation of competent Escherichia coli cells is a foundational step. The physiological state of the bacterial culture at the time of harvesting is a critical determinant of transformation efficiency (TrE). Achieving mid-log phase growth, characterized by rapidly dividing, metabolically active cells, is paramount for inducing the highest levels of competency. This application note details the protocols and quantitative data supporting the cultivation of E. coli to mid-log phase, providing researchers and drug development professionals with methodologies to maximize transformation success for cloning, library construction, and recombinant protein expression.

The Critical Window: Mid-Log Phase

Phases of Bacterial Growth

Bacterial growth in liquid medium follows a characteristic progression through four distinct phases [46]:

- Lag Phase: A period of slow growth following inoculation where cells adapt to the medium.

- Log Phase (Exponential Phase): Cells divide rapidly and exponentially. This is the phase where cells are healthiest and most actively producing proteins [46].

- Stationary Phase: Nutrient depletion and metabolic waste accumulation halt population growth.

- Death Phase: Toxicity from metabolic products leads to a decline in viable cell count.

Why Mid-Log Phase is Crucial

Harvesting cells during the early- to mid-log phase is essential because this is when bacterial cells are at their physiological peak. The cell walls are more permeable during active division, facilitating the formation of channels through which DNA molecules can pass during transformation [46]. All competent cell preparation methods, including the highly efficient TSS-HI and Hanahan methods, require cultures to be grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of between 0.3 and 0.5 before induction of competency [20] [17]. Allowing the OD600 to exceed 0.4 risks the culture exiting the log phase, resulting in cells that are suboptimal for transformation [46].

Table 1: Key Growth Parameters for Optimal Competency

| Parameter | Target Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| OD600 at Harvest | 0.35 - 0.5 [46] [17] | Indicates active, mid-log phase growth. |

| Doubling Time | ~20 minutes [46] | Characteristic of healthy, exponential growth. |

| Culture Volume | 50-100 mL [17] [47] | Standard for lab-scale competent cell preps. |

| Incubation Temp | 37°C [46] [17] | Optimal for E. coli growth. |

Experimental Protocol: Cultivation and Monitoring

Workflow for Cell Cultivation

The following diagram outlines the complete workflow from culture initiation to cell harvesting for competent cell preparation.

Detailed Methodology

Materials:

- E. coli strain of choice (e.g., DH5α, XL-1 Blue, BW3KD) [20] [17]

- LB (Luria-Bertani) broth or SOB (Super Optimal Broth) [17]

- Sterile conical flasks (volume ≥4x culture volume for aeration)

- Spectrophotometer with cuvettes for measuring OD600 [46]

- Incubator shaker at 37°C

Procedure:

- Starter Culture: From a freshly streaked agar plate, inoculate a single colony into 5-10 mL of sterile LB medium. Incubate overnight (~16 hours) at 37°C with shaking at 200-220 rpm [46] [17].

- Dilution and Main Culture: The next day, dilute the overnight starter culture 1:50 to 1:100 into a larger volume of pre-warmed LB medium (e.g., add 1 mL of starter to 50-100 mL of LB in a 250-500 mL flask) [17] [47].

- Incubation and Monitoring: Incubate the main culture at 37°C with vigorous shaking (200-220 rpm). After approximately 1.5-2 hours, begin monitoring the OD600 every 20-30 minutes.

- Calibrate the spectrophotometer at 600 nm using uninoculated LB broth as a blank [46].

- Pipette 2 mL of the growing culture into a clean cuvette, wipe the sides to remove fingerprints, and measure the absorbance.

- Harvesting: Once the OD600 reaches 0.35-0.4, immediately remove the flask from the incubator and place it on ice for 20-30 minutes to halt growth [46]. Swirl gently and occasionally to ensure even cooling.

- Processing: The chilled cells are now ready for the subsequent steps of competent cell preparation (e.g., centrifugation, resuspension in transformation buffers).

Impact of Growth Phase on Transformation Efficiency

The choice of growth medium and bacterial strain can influence the final transformation efficiency (TrE), even when cultures are harvested at the same OD600.