Culture vs. Non-Culture Microbiological Tests: A Strategic Guide for Research and Diagnostic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of culture-based and culture-independent microbiological test methods for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Culture vs. Non-Culture Microbiological Tests: A Strategic Guide for Research and Diagnostic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of culture-based and culture-independent microbiological test methods for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of both approaches, examines specific methodological applications across various infection types, addresses key challenges in implementation and data interpretation, and outlines rigorous validation and comparative assessment frameworks. The content synthesizes current evidence to guide optimal test selection, highlighting how non-culture methods are transforming diagnostic paradigms while acknowledging the enduring role of culture for antimicrobial susceptibility testing and public health surveillance.

The Evolving Landscape of Microbiological Testing: From Traditional Culture to Modern Diagnostics

Historical Context and Limitations of Culture-Based Methods

For over a century, microbial culture has served as the foundational cornerstone of clinical microbiology, enabling the isolation and identification of pathogenic organisms responsible for infectious diseases [1]. Robert Koch's pioneering work in establishing pure culture techniques created the paradigm that has guided laboratory diagnosis for generations [1]. This methodology relies on the fundamental principle of cultivating microorganisms under controlled laboratory conditions using various nutrient media, atmospheric conditions, and temperature parameters to support microbial growth [1]. However, the early 21st century has witnessed a remarkable transformation in diagnostic approaches, with non-culture-based techniques increasingly challenging traditional culture-based methods across numerous clinical scenarios [2] [3]. This shift reflects growing recognition of the inherent limitations of culture techniques alongside the emergence of sophisticated molecular diagnostics that offer improved sensitivity, speed, and diagnostic accuracy [4] [3]. This comprehensive analysis examines both historical and contemporary aspects of culture-based methods, objectively evaluating their performance against non-culture alternatives through experimental data and clinical evidence.

Historical Context and Development of Culture Methods

The evolution of culture-based methodologies represents a fascinating journey of scientific innovation. Early strategies employed simple meat infusions or heart and brain extracts as nutrient sources, with subsequent refinement through the addition of peptones, yeast extracts, and various vegetable components [1]. The invention of the petri dish revolutionized the field by enabling observation of colonial morphology while minimizing contamination [1]. The development of solid culture media using kitchen components like gelatin and agar allowed for pure culture isolation and detailed bacterial characterization [1].

Key Historical Developments in Culture Methodology

- Early Culture Media: Initial substrates included meat infusions, heart/brain extracts, and vegetable components; peptones became widely used as carbohydrate-free nutrient additives [1]

- Solid Media Revolution: Addition of gelatin or agar created solid culture media, enabling pure culture isolation and colonial morphology study [1]

- Enriched Media: Blood addition provided hemin and other nutrients, particularly benefiting fastidious microorganisms and anaerobic species [1]

- Selective Media: Incorporation of inhibitors like deoxycholic acids, bile salts, crystal violet, and antibiotics allowed isolation of pathogens from complex microbiota [1]

- Atmosphere Control: Development of anaerobic, microaerophilic, and specialized atmospheric conditions expanded the range of culturable organisms [1]

The progressive refinement of culture conditions—including optimized nutrients, atmosphere control, temperature modulation, and incubation times—enabled the cultivation of increasingly fastidious microorganisms [1]. This methodological evolution fundamentally advanced our understanding of infectious diseases and established culture as the "gold standard" against which new diagnostic techniques would be measured [3].

Fundamental Limitations of Culture-Based Methods

Despite their historical importance, culture-based methods possess significant limitations that impact their utility in modern clinical practice. The core constraints include prolonged turnaround times, limited sensitivity, inability to culture certain pathogens, and substantial resource requirements.

Time Constraints and Turnaround Limitations

Culture methods typically require 24-48 hours for initial growth of common bacterial pathogens, with fastidious organisms necessitating considerably longer incubation periods [1]. For example, Bordetella pertussis colonies become visible in 3-4 days, Legionella pneumophila requires approximately 3 days, and Bartonella species may need 12-14 days on blood agar, with some isolates requiring over 45 days for growth detection [1]. This extended time to result delays critical treatment decisions and impacts patient outcomes.

Sensitivity and Detectability Challenges

Culture methods demonstrate variable and often suboptimal sensitivity for many pathogens. In comparative studies of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients, real-time PCR showed significantly higher detection rates for key respiratory pathogens compared to culture: Haemophilus influenzae (43.4% vs 26.2%), Moraxella catarrhalis (12.9% vs 6.3%), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (11.0% vs 17.4% in one study, with higher PCR detection in others) [4]. Similarly, for Campylobacter enteritis, molecular tests demonstrated 51.2% higher sensitivity than culture methods (41 PCR-positive specimens vs 21 culture-positive) [3].

Fastidious and Non-culturable Organisms

Many clinically significant pathogens either grow poorly under routine culture conditions or cannot be cultured altogether. Examples include Talaromyces marneffei (requiring prolonged incubation and specific dimorphic transition) [5], Mycobacterium tuberculosis (weeks for culture) [2], Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae [2], and numerous viruses [2]. This limitation has driven the development of specialized culture techniques including shell vial procedures, axenic media, and amoebal coculture systems [1].

Technical and Interpretation Challenges

Culture-based assessment requires significant technical expertise for optimal performance. Microscopy, while rapid and inexpensive, is labor-intensive and requires highly skilled scientists [2]. Even with optimal technique, microscopy demonstrates poor sensitivity for most common bacterial and fungal infections [2]. Additionally, culture methods struggle with polymicrobial infections; in urinary tract infection evaluation, PCR detected polymicrobial infections in 95% of cases compared to only 22% with culture [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Limitations of Culture-Based Diagnostic Methods

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenge | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Time Constraints | 24-48 hours for common pathogens; weeks for slow-growing organisms | Delayed diagnosis and treatment initiation |

| Sensitivity Issues | Lower detection rates for multiple pathogens including H. influenzae, Campylobacter | Missed diagnoses and false negatives |

| Fastidious Organisms | Difficult or impossible to culture organisms (T. marneffei, M. pneumoniae) | Incomplete diagnostic assessment |

| Technical Demands | Requires skilled personnel; labor-intensive processing | Limited availability and standardization |

| Sample Viability | Affected by transport conditions, prior antibiotic exposure | Reduced diagnostic yield |

| Antimicrobial Testing | Additional 24-48 hours beyond identification | Further delays in targeted therapy |

Comparative Performance Data: Culture vs. Non-Culture Methods

Robust experimental and clinical studies provide quantitative data demonstrating the performance differences between culture and non-culture methods across various specimen types and pathogen categories.

Respiratory Pathogen Detection

In comprehensive studies of COPD patients, significant disparities emerged between culture and molecular methods. Analysis of 2,293 samples from the AERIS study revealed PCR detection rates for H. influenzae were 65.6% higher than culture (43.4% vs 26.2%) [4]. Similarly, for M. catarrhalis, PCR detection (12.9%) doubled the culture rate (6.3%) [4]. The NTHI-004 and NTHI-MCAT-002 studies confirmed this pattern, with PCR identifying substantially more positive samples for all major respiratory pathogens [4]. Bacterial load analysis further demonstrated that many culture-negative samples showed pathogen loads by PCR equivalent to culture-positive samples, confirming the sensitivity limitation rather than clinical irrelevance of PCR-positive results [4].

Gastrointestinal Pathogen Detection

The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) investigating 32 enteropathogens found substantially higher attributable incidences using quantitative PCR compared to traditional microbiological methods [3]. The qPCR-derived incidence rates were approximately twice as high for Campylobacter, five times higher for adenovirus, two times higher for Shigella spp./EIEC, and 1.5 times higher for heat-stable enterotoxin-producing E. coli [3]. This enhanced detection capability has led to marked increases in the use of culture-independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs) for detecting gastrointestinal pathogens including Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella over the last decade [3].

Environmental Sampling and MDRO Recovery

Recent methodological comparisons of environmental sampling techniques for multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) demonstrate significant variability in culture-based recovery efficiency [6]. In controlled experiments comparing sponge-sticks (SS) and ESwabs, culture-based recovery varied substantially across MDRO taxa, being highest for vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus and lowest for carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPA) [6]. Sponge-stick methods generally showed superior culture-based recovery compared to ESwabs, except for CRPA where all methods performed poorly [6]. These findings highlight how methodological choices significantly impact culture-based detection efficiency.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Detection Rates: Culture vs. PCR

| Pathogen | Sample Type | Culture Positive (%) | PCR Positive (%) | Relative Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. influenzae | Sputum (AERIS study) | 26.2% | 43.4% | 65.6% higher |

| M. catarrhalis | Sputum (AERIS study) | 6.3% | 12.9% | 104.8% higher |

| S. pneumoniae | Sputum (AERIS study) | 17.4% | 11.0% | Culture higher* |

| Campylobacter | Stool | 51.2% sensitivity | 100% sensitivity | 95.3% higher sensitivity |

| Bordetella pertussis | Respiratory | Culture-negative | 170/368 detected | PCR detected culture-negative infections |

Note: Lower PCR detection for *S. pneumoniae in AERIS study attributed to misidentification of S. pseudopneumoniae/mitis isolates by conventional methods [4]*

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Comparisons

Culture-Based Method Evaluation Protocol

Recent investigations into culture-based detection of Enterobacterales in donor human milk provide insightful methodological comparisons [7]. This study systematically evaluated four culture-based approaches with varying sensitivity:

- Method 1 (Reference): Direct plating of 20 µL of sample onto selective media

- Method 2 (Volume Enhancement): Increased plating volume to 100 µL of sample

- Method 3 (Concentration): Centrifugation of 1 mL sample to concentrate bacterial cells before plating

- Method 4 (Enrichment): 24-hour pre-incubation in liquid enrichment medium before plating [7]

Detection limits varied by several orders of magnitude (2.86 × 10² CFU/mL to 4.90 × 10⁰ CFU/mL) across methods, with enrichment-based techniques demonstrating superior sensitivity [7]. In real-world testing of 93 raw donor milk samples, enrichment-based methods detected Gram-negative pathogens in four samples while direct plating detected none [7].

Environmental Sampling Protocol for MDRO Detection

Standardized sampling methodologies are critical for reliable culture-based detection. Recent comparative studies employed the following protocol:

- Surface Contamination: Known quantities of each MDRO were pipetted onto stainless-steel surfaces and allowed to dry for 1 hour

- Sampling Methods: Parallel testing of ESwabs (moistened with ESwab solution), cellulose-containing sponge-sticks (CS), and polyurethane-containing sponge-sticks (PCS)

- Processing: Sponge-sticks expressed in PBS containing 0.02% Tween 80 using a stomacher, centrifuged, and resuspended; ESwabs vortexed

- Culture: Serial dilutions plated on selective and nonselective media, incubated at 37°C for 24 hours

- Analysis: Viable colony counting and nucleic acid recovery assessment [6]

This protocol revealed that culture-based recovery was significantly higher for sponge-sticks compared to ESwabs for most MDROs, except CRPA where all methods performed poorly [6].

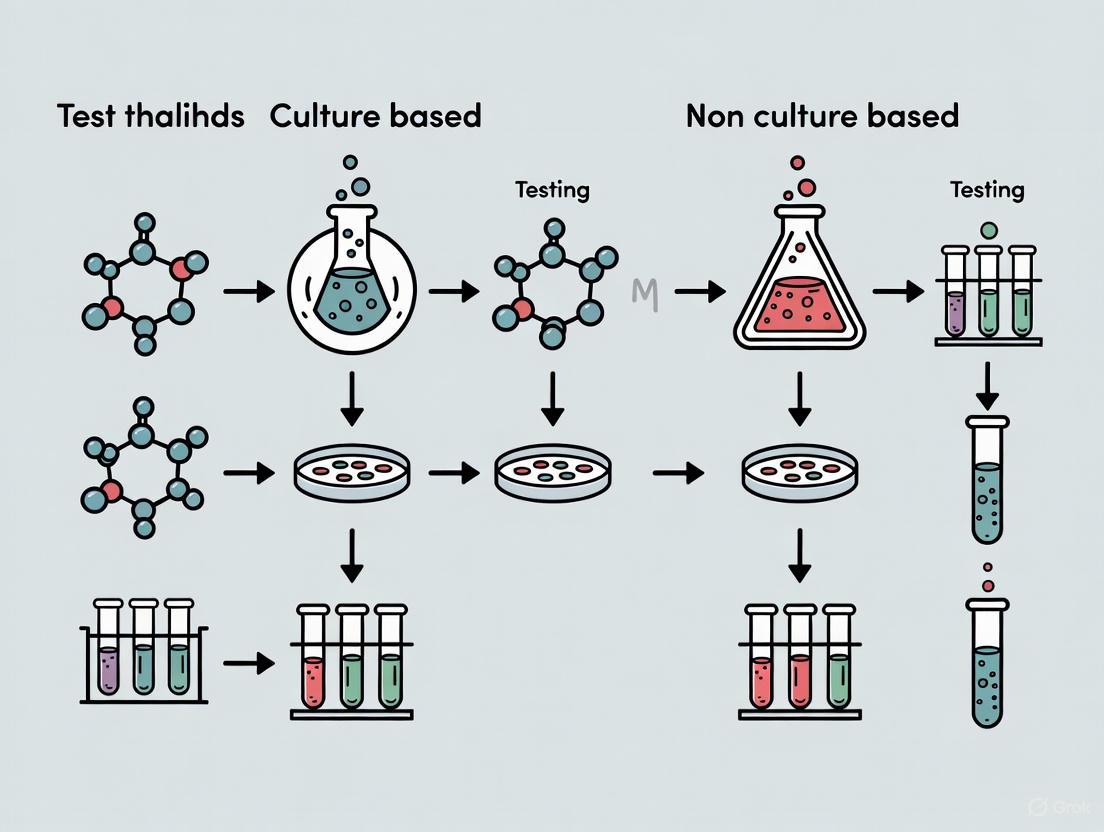

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflow: Culture vs. Non-Culture Methods. Culture-based pathways require multiple processing steps and extended incubation periods, while molecular methods provide more rapid results through nucleic acid-based detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Culture and Non-Culture Methods

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Context | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Agar Media (e.g., VRBD, Drigalski) | Selective growth of target microorganisms | Enterobacterales detection in complex samples | Variable detection limits (10²-10⁰ CFU/mL) [7] |

| Enrichment Broths | Enhancement of low bacterial concentrations | Pathogen detection in paucibacillary samples | Improves sensitivity; adds 18-24 hours to protocol [7] |

| ESwab & Sponge-Stick Systems | Environmental surface sampling | MDRO recovery from healthcare surfaces | Sponge-sticks generally superior culture recovery to ESwabs [6] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of DNA/RNA from clinical samples | Molecular detection methods (PCR, mNGS) | Critical step influencing sensitivity/specificity of molecular assays [6] |

| PCR Master Mixes | Amplification of target sequences | Pathogen detection and identification | Enables quantification and multiplex detection capabilities [4] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Kits | Comprehensive genomic analysis | Pathogen identification and AMR gene detection | Allows culture-independent resistance prediction [6] [8] |

Antimicrobial Resistance Detection: Critical Limitations

The emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance represents one of the most significant challenges in modern infectious disease management, and culture methods exhibit particular limitations in this domain.

Phenotypic vs Genotypic Resistance Detection

Culture-based antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) remains the reference standard for determining minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) and establishing resistance profiles [8]. However, this approach requires isolated pure cultures, adding 24-48 hours to the diagnostic timeline after initial growth detection [8]. This delay significantly impacts clinical decision-making, particularly for critically ill patients requiring immediate appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Molecular methods offer rapid detection of resistance mechanisms but face different limitations. Techniques including PCR, whole genome sequencing (WGS), and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) can identify resistance genes within hours [6] [8]. However, the presence of resistance genes does not necessarily correlate with phenotypic expression, potentially leading to false-positive resistance predictions [8]. Additionally, resistance mediated by novel mechanisms or undefined genetic markers may escape detection by targeted molecular approaches [8].

Methodological Challenges in Resistance Detection

Recent evaluations highlight specific limitations in resistance detection methodologies:

- Culture-Based Limitations: Labor-intensive, slow turnaround, inability to test unculturable organisms, affected by prior antibiotic exposure [8]

- Molecular Method Limitations: Detects resistance potential rather than expression, may miss novel resistance mechanisms, requires prior knowledge of resistance markers for targeted approaches [8]

- Sequencing Limitations: WGS predictions may not correlate with phenotypic expression; false negatives documented in specific pathogens like Salmonella enterica [8]

The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) has highlighted critical issues requiring resolution before widespread implementation of genotypic resistance prediction, including insufficient evidence for prediction accuracy across many bacteria and the non-trivial bioinformatic processes required for proper interpretation [8].

Culture-based methods retain important roles in clinical microbiology, particularly for antimicrobial susceptibility testing and outbreak investigation where isolate availability remains essential [3]. However, substantial evidence demonstrates significant limitations in sensitivity, turnaround time, and applicability to fastidious microorganisms. Non-culture methods, particularly nucleic acid amplification techniques and sequencing-based approaches, offer demonstrably superior sensitivity and faster detection for many clinically important pathogens [2] [4] [3]. The optimal diagnostic approach increasingly involves strategic integration of both methodologies, leveraging the respective strengths of each technique while mitigating their limitations through complementary application. Future directions will likely see continued refinement of molecular methods alongside development of sophisticated algorithms integrating genotypic and phenotypic data to optimize patient management and antimicrobial stewardship.

The field of microbial diagnostics is undergoing a significant transformation, moving from traditional culture-based techniques toward rapid, non-culture methods. Culture test procedures such as the heterotrophic plate count, the most probable number (MPN) method, and the spread plate count have long been widely cited and accepted for the enumeration of microorganisms. However, these methods have inherent limitations, most notably extended performance time. Furthermore, any given culture test method typically recovers only a portion of the total viable microbes present in a sample. It is these limitations that have recently led to the marketing and adoption of a variety of non-culture procedures, test kits, and instruments [9] [10].

Non-culture microbiological tests attempt to provide the same or complementary information as culture methods through the measurement of different parameters. Culture test methods estimate microbial population densities based on the ability of microorganisms in a sample to proliferate in or on a specified growth medium under specified growth conditions. In contrast, non-culture test methods bypass the need for cellular proliferation, instead detecting microorganisms through alternative means such as genetic analysis, antigen detection, or enzymatic activity [9]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their technological foundations, performance characteristics, and practical applications in modern research and diagnostic settings.

Scope and Definition of Non-Culture Methods

Fundamental Principles and Classifications

Non-culture methods encompass a broad range of techniques designed to detect, identify, or quantify microorganisms without relying on their ability to grow in artificial culture media. According to ASTM E1326, a standard guide for evaluating these tests, their purpose is to assist users and producers "in determining the applicability of the test for processing different types of samples and evaluating the accuracy of the results" [9] [10]. The scope of these methods is vast, covering applications from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring and food safety.

The fundamental principle underlying non-culture methods is that microbial presence can be established through indicators other than growth. These indicators include:

- Genetic material: Detection of microbial DNA or RNA sequences specific to target organisms

- Antigens: Recognition of microbial surface structures or secreted proteins

- Enzymatic activity: Measurement of specific biochemical reactions

- Cell components: Identification of unique microbial structural elements

It is recognized that the heterotrophic plate count (HPC) does not recover all microorganisms present in a product or a system. When this problem occurs during the characterization of a microbiological population, alternative standard enumeration procedures are necessary [9]. Non-culture methods fill this critical gap, offering solutions when traditional culture fails to detect viable but non-culturable organisms or when rapid results are essential for time-sensitive decisions.

Technological Categories of Non-Culture Methods

Non-culture methods can be broadly categorized into several technological domains, each with distinct mechanisms and applications. The following diagram illustrates the major categories and their relationships:

Technological Foundations of Major Non-Culture Platforms

Molecular Detection Methods

Molecular techniques represent one of the most significant advances in non-culture diagnostics, offering unprecedented specificity and sensitivity. These methods detect microbial nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) through various amplification and detection strategies.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Quantitative PCR (qPCR) techniques amplify specific genetic targets to detectable levels. In clinical applications for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, PCR enables detection of Aspergillus DNA from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples with high sensitivity [11]. Modern implementations have expanded to viability PCR using propidium monoazide, a photoreactive DNA-binding dye that preferentially binds to double-stranded DNA of dead cells, ensuring only DNA from live microbial cells is detected [12].

Isothermal amplification methods represent another frontier, with techniques like electropulse isothermal amplification enabling rapid (20 cycles/min) target amplification without thermal cycling. This approach has been integrated into novel diagnostic systems where captured DNA and/or RNA is subjected to rapid amplification, with products hybridized to thousands of target probes on polymer-coated grids [13].

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) provides culture-independent detection of pathogens by sequencing all nucleic acids in a sample and comparing them against extensive databases. This method is particularly valuable for detecting unculturable or unexpected pathogens in invasive samples like bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or cerebrospinal fluid [5].

Immunological and Biosensor Approaches

Immunological methods detect microbial antigens or host antibody responses to infection, providing complementary information to molecular techniques.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) formats detect circulating antigens or antibodies with quantifiable sensitivity. For melioidosis diagnosis, indirect ELISA demonstrates a pooled sensitivity of 0.86 [95% CI (0.80-0.90)] and specificity of 0.85 [95% CI (0.80-0.89)] according to a recent meta-analysis [14].

Lateral Flow Immunoassays (LFI) provide rapid, point-of-care detection of specific pathogens. For melioidosis, LFIs targeting CPS show a pooled sensitivity of 0.52 [95% CI (0.33-0.70)] and specificity of 0.96 [95% CI (0.93-0.98)] [14]. These assays are particularly valuable in resource-limited settings where complex laboratory infrastructure is unavailable.

MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry has revolutionized microbial identification by creating unique spectral fingerprints based on protein profiles. The technology works by crystallizing the organism in an organic acid matrix. A laser ionizes the sample within the matrix, producing singly protonated sample ions that are accelerated through a vacuum. The speed at which the ions travel creates a pattern unique to a given organism [12]. Artificial intelligence is now being applied to interpret MALDI-TOF MS spectra, using machine learning approaches like support vector machines, genetic algorithms, and artificial neural networks to improve identification accuracy [12].

Innovative Detection Platforms

Emerging technologies are pushing the boundaries of non-culture methods, with several innovative platforms showing significant promise.

Integrated Cassette Systems represent a futuristic approach to comprehensive pathogen detection. These systems, such as the conceptual MyCrobe system, incorporate multiple detection modalities in a single device. The system uses a collection device with a porous, bristled tip that expresses sterile processing buffer and creates gentle sonication during sample collection. The sample is then applied to a cassette with separate chambers for nucleic acid processing and antigen detection [13].

Microfluidic Separation with AI Detection enables rapid, culture-free detection of bacteria from whole blood for sepsis diagnosis. This approach concatenates five steps: smart centrifugation, selective blood cell lysis, volume reduction, microfluidic trapping combined with microscopy imaging, and deep-learning based detection of bacterial cells. The entire assay takes less than a few hours, significantly faster than traditional culture methods [15].

Biosensors are being developed for continuous monitoring of pathogens in various environments. Municipal water providers have experimented with biosensors in water supplies to detect specific pathogens. While the pharmaceutical sector has used flow cytometry to detect microbial numbers in circulating water systems, newer approaches combine ultrafiltration membrane modules with viability quantitative PCR for improved sensitivity and specificity [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Culture-Free Sepsis Detection

The detection of bloodstream infections represents one of the most challenging applications in microbiology due to low microbial loads and the critical need for rapid results. The following workflow illustrates the protocol for culture-free sepsis detection using microfluidic separation and AI-based detection:

Step 1: Smart Centrifugation – Layer 3 ml of blood culture medium-diluted spiked blood on top of 1 ml density medium (2:1 volumetric mixture of Lymphoprep and BCM with density of 1.051 g/ml). Centrifuge for 5 minutes at 600 × g in a hanging bucket centrifuge. This step removes 99.82% ± 0.04% of RBCs, 95% ± 4% of WBCs, and 63% ± 2% of platelets while recovering 65% ± 16% of E. coli, 95% ± 17% of K. pneumoniae, 64% ± 24% of E. faecalis, or 8% ± 7% of S. aureus [15].

Step 2: Selective Blood Cell Lysis – Mix approximately 2.5 ml supernatant from the smart centrifugation step with 1 ml of selective lysing solution (sodium cholate hydrate and saponin mixture). Keep in a shaking incubator at 37°C for 10 minutes to completely lyse remaining RBCs, WBCs, and platelets [15].

Step 3: Volume Reduction – Enrich the sample and remove excess lysing buffer in a second centrifugation step to concentrate bacterial cells for downstream processing [15].

Step 4: Microfluidic Trapping – Load the concentrated sample into a microfluidic chip designed to trap bacterial cells while allowing debris to pass through. Perform microscopy imaging of trapped cells [15].

Step 5: Deep Learning Detection – Apply trained convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopy images and identify bacterial cells based on morphological features. This approach has detected E. coli, K. pneumoniae, or E. faecalis from spiked samples of healthy human donor blood at clinically relevant concentrations as low as 9, 7, and 32 colony-forming units per ml of blood, respectively, within 2 hours [15].

Protocol for Antigen Detection in Fungal Diagnostics

For Talaromyces marneffei infection, a thermally dimorphic fungus that primarily affects immunocompromised individuals, antigen detection serves as an important diagnostic tool:

Sample Preparation – Collect blood, urine, or respiratory samples according to standardized procedures. For blood samples, serum separation is required before testing.

Galactomannan ELISA – Use Platelia Aspergillus Ag ELISA (Bio-Rad) according to manufacturer instructions. Add sample to microplate wells coated with monoclonal antibody EB-A2 specific to Aspergillus galactomannan. After incubation and washing, add rat monoclonal antibody EB-A2 peroxidase conjugate. Following second incubation and wash, add substrate solution and measure optical density. The test is recommended for both serum and BAL samples with cutoff indices established for each sample type [11].

(1→3)-β-D-Glucan Detection – Use Fungitell assay (Associated Cape-Cod, Inc.) following manufacturer protocol. The assay is based on the activation of a proenzyme factor in the horseshoe crab coagulation cascade. Dilute serum or BAL samples and mix with the reagent. Measure the reaction kinetics spectrophotometrically. A positive result is defined as >80 pg/mL, though some studies recommend increasing the cutoff to >200 pg/mL for BAL samples to improve specificity [11].

Lateral Flow Assay – For rapid detection, use the OLM Diagnostics or IMMY lateral flow device. Apply sample to the sample pad and allow it to migrate across the test strip. Results are typically available within 15-30 minutes. These assays demonstrate high specificity but variable sensitivity across different patient populations [11].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data Analysis

Diagnostic Accuracy Across Pathogens and Sample Types

The performance characteristics of non-culture methods vary significantly depending on the target pathogen, sample matrix, and specific technology employed. The following table summarizes the diagnostic accuracy of various non-culture methods for different infectious diseases:

Table 1: Diagnostic Accuracy of Non-Culture Methods for Various Infectious Diseases

| Infectious Disease | Detection Method | Sample Type | Sensitivity (Pooled) | Specificity (Pooled) | Time to Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melioidosis | Indirect ELISA | Serum | 0.86 [0.80-0.90] | 0.85 [0.80-0.89] | 2-4 hours |

| Melioidosis | IHA (1:160 threshold) | Serum | 0.60 [0.46-0.72] | 0.70 [0.58-0.79] | 1-2 hours |

| Melioidosis | LFI (CPS target) | Serum | 0.52 [0.33-0.70] | 0.96 [0.93-0.98] | 15-30 minutes |

| Melioidosis | IFA (polyclonal) | Serum | 0.60 [0.44-0.75] | 0.99 [0.97-1.00] | 2-3 hours |

| Melioidosis | RT-PCR (T3SS target) | Blood/Tissue | 0.72 [0.41-0.91] | 1.00 [0.97-0.99] | 2-4 hours |

| Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis | Galactomannan EIA | BAL | 0.82-0.92* | 0.85-0.96* | 2-4 hours |

| Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis | (1→3)-β-D-Glucan | BAL | 0.52-0.89* | 0.31-0.62* | 1-2 hours |

| Talaromyces marneffei infection | Metagenomic NGS | BAL/CSF | 0.85-0.95* | 0.90-0.98* | 24-48 hours |

Ranges represent variation across multiple studies with different patient populations and cutoff values [11] [14].

Method Comparison: Sepsis Diagnosis

The performance of novel non-culture methods for sepsis diagnosis demonstrates significant advantages over traditional blood culture, particularly in time-to-result:

Table 2: Comparison of Sepsis Diagnostic Methods

| Method | Principle | Detection Limit (CFU/ml) | Time to Result | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Blood Culture | Microbial growth in liquid media | 1-10 CFU/ml | 2-5 days | Gold standard, provides isolate for AST | Slow, affected by prior antibiotics |

| Automated Blood Culture | Microbial growth with automated detection | 1-10 CFU/ml | 1-3 days | Faster than manual culture, continuous monitoring | Still requires growth, moderate speed |

| PCR-based Direct Detection | Nucleic acid amplification | 10-100 CFU/ml | 4-8 hours | Rapid, can detect non-viable organisms | Limited resistance information, may miss mixed infections |

| Microfluidic/AI Detection | Physical separation + microscopic identification | 7-32 CFU/ml* | 2 hours | Very rapid, phenotypic information | Limited clinical validation, challenging for S. aureus |

| Integrated Cassette Systems | Multiplex nucleic acid and antigen detection | Varies by target | 15-90 minutes | Comprehensive pathogen and resistance profiling | Limited availability, high cost |

Varies by organism: E. coli: 9 CFU/ml, K. pneumoniae: 7 CFU/ml, E. faecalis: 32 CFU/ml [15].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of non-culture methods requires specific reagents and materials designed to optimize recovery, detection, and analysis of microorganisms. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for executing non-culture microbiological tests:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Non-Culture Methods

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Lysis Solution | Sodium cholate hydrate and saponin mixture | Selective lysis of human blood cells while preserving bacterial integrity | Sepsis diagnostics from whole blood [15] |

| Density Gradient Media | 2:1 volumetric mixture of Lymphoprep and blood culture medium (density 1.051 g/ml) | Separation of bacteria from blood components based on density differences | Smart centrifugation step in sepsis diagnostics [15] |

| Nucleic Acid Preservation Buffer | Detergents and enzymes that promote nucleic acid release while preventing degradation | Stabilizes genetic material during sample storage and transport | MyCrobe collection system [13] |

| Viability Dyes | Propidium monoazide (PMA) or similar compounds | Penetrates compromised membranes of dead cells, binding DNA and preventing amplification | Viability PCR to distinguish live vs. dead microorganisms [12] |

| MALDI-TOF Matrix | Organic acid crystals (e.g., α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) | Facilitates ionization of microbial proteins for mass spectrometric analysis | Microbial identification via MALDI-TOF MS [12] |

| Hybridization Buffers | Salt solutions with detergents and blocking agents | Optimizes binding of nucleic acid probes to complementary targets | Microarray-based pathogen detection [13] |

| Enzyme Substrates | Chromogenic or fluorogenic compounds | Produces detectable signal upon enzymatic cleavage by microbial enzymes | Detection of microbial enzyme activity in biosensors |

| Microfluidic Coatings | PEGylated surfaces or specific chemical treatments | Prevents non-specific binding in microfluidic channels | Microfluidic bacterial capture devices [15] |

Non-culture methods represent a fundamental shift in microbiological detection, offering solutions to the inherent limitations of traditional culture-based techniques. These methods leverage diverse technological foundations—from genetic detection to immunological recognition and AI-enhanced microscopy—to provide faster, often more sensitive alternatives to culture. While the diagnostic accuracy of these methods varies by target organism and sample type, their collective advancement points toward a future where comprehensive pathogen detection and characterization can occur within hours rather than days.

The appropriate application of these technologies requires understanding their respective strengths, limitations, and implementation requirements. As standardization improves and technologies mature, non-culture methods are poised to become increasingly central to microbiological analysis across clinical, industrial, and research settings, ultimately enhancing our ability to detect and respond to microbial threats with unprecedented speed and precision.

Key Advantages and Inherent Limitations of Each Paradigm

Microbiological testing represents a critical foundation for diagnosing infections, guiding antimicrobial therapy, and advancing pharmaceutical research. For over a century, culture-based methods have served as the cornerstone of microbial identification, relying on the propagation of microorganisms in artificial media to obtain visible growth for analysis [16]. However, the emergence of non-culture-based techniques—including molecular, antigen detection, and sequencing methods—has fundamentally transformed diagnostic paradigms, offering alternative pathways for pathogen detection. Within clinical and research settings, understanding the comparative advantages and limitations of these approaches becomes paramount for selecting appropriate methodologies based on specific diagnostic needs, timeframe constraints, and required sensitivity [17].

This comprehensive analysis examines the technical performance, operational characteristics, and clinical applications of both culture and non-culture paradigms. By synthesizing experimental data and comparative studies, we provide an evidence-based framework to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in methodological selection for diverse laboratory contexts, from routine clinical diagnostics to cutting-edge research applications.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data Analysis

The comparative effectiveness of culture versus non-culture methods varies significantly across performance metrics, as evidenced by multiple clinical studies. The table below summarizes key quantitative comparisons between these methodological paradigms.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Culture vs. Non-Culture Methods

| Performance Metric | Culture Methods | Non-Culture Methods | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Result | 24-48 hours (routine); up to 7 days (slow-growing pathogens) [18] | 2-8 hours (PCR); <2 hours (rapid antigen tests) [15] [18] | Bacterial and fungal infection diagnostics [15] [18] |

| Analytical Sensitivity | 10-100 CFU/mL (for viable organisms) [15] | 1-10 gene copies (PCR); variable for antigen detection [15] | Sepsis diagnostics using blood samples [15] |

| Pathogen Detection Range | Limited to viable, cultivable organisms [19] | Viable/non-viable pathogens; uncultivable organisms; antimicrobial resistance markers [17] [18] | Broad-spectrum pathogen detection [17] [19] |

| Additional Characterization | Provides antibiotic susceptibility profiles [18] | Limited susceptibility data (except for specialized molecular assays) [15] | Guidance for antimicrobial therapy [18] |

| Automation Potential | Moderate (automated blood culture systems) [20] | High (molecular platforms; AI-integrated systems) [12] | High-throughput laboratory settings [12] |

A landmark study comparing automated blood culture systems (ABCS) with conventional culture methods for pleural infection diagnosis demonstrated the superior sensitivity of non-culture approaches. In 9,020 patients, ABCS detected pathogens in 632 cases, while conventional culture identified only 302 (47.8%) of these, with 330 (52.2%) patients having isolates detected exclusively by ABCS [20]. This substantial difference in detection capability highlights the sensitivity advantage of automated non-culture systems, particularly for challenging sample types like pleural fluid.

Non-Culture Methodologies: Technical Approaches and Applications

Non-culture techniques encompass diverse technological platforms, each with distinct mechanisms and applications. The table below outlines major non-culture categories with their specific implementations and performance characteristics.

Table 2: Non-Culture Method Categories and Characteristics

| Method Category | Examples | Mechanism | Clinical/Research Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Detection | PCR, multiplex PCR, viability qPCR [15] [18] | Amplification of pathogen-specific DNA/RNA sequences | Sepsis diagnosis [15]; infectious disease identification [18]; pharmacogenomics [18] | Cannot distinguish viable/non-viable pathogens (without viability dyes) [18] |

| Antigen Detection | Galactomannan EIA, CLIA, LFA [11] | Immunoassay detection of microbial antigens | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis diagnosis [11] | Variable specificity; cross-reactivity issues [11] |

| Metagenomic Sequencing | Shotgun metagenomics, 16S rRNA sequencing [17] | Sequencing all genetic material in sample; bioinformatics analysis | Microbial community profiling [17]; uncultivable pathogen discovery [19] | High cost; complex data interpretation; database limitations [17] |

| Proteomic Identification | MALDI-TOF MS [12] | Mass spectrometry analysis of microbial protein profiles | Microbial identification [12] | Limited database coverage; equipment cost [12] |

Molecular methods like PCR provide exceptional speed and sensitivity, detecting pathogens within hours—crucial for sepsis management where mortality increases approximately 8% per hour of delayed effective treatment [15]. Advanced approaches integrate viability markers like propidium monoazide in qPCR assays to distinguish live from dead microorganisms, addressing a key limitation of molecular detection [12].

For fungal infections such as invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, non-culture biomarkers like galactomannan and (1→3)-β-D-glucan offer improved sensitivity over culture, particularly in immunocompromised patients [11]. Metagenomic sequencing enables comprehensive microbiome analysis, with studies demonstrating that culture-enriched metagenomic sequencing (CEMS) and culture-independent metagenomic sequencing (CIMS) identify largely non-overlapping microbial species (only 18% overlap), suggesting complementary roles in revealing full microbial diversity [19].

Experimental Protocols: Methodological Details

Automated Blood Culture System (ABCS) Protocol for Pleural Fluid

A substantial comparative study evaluated ABCS versus conventional culture using pleural fluid samples from 9,020 patients [20]. The methodology provides a robust template for comparative performance assessment:

Sample Collection and Preparation: Fresh pleural fluid samples were collected via thoracentesis or percutaneous drainage. At bedside, 5-10 mL of fluid was inoculated into each aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottle (for ABCS), while 5-10 mL was placed in a sterile tube for conventional culture [20].

Transport and Processing: All samples were promptly transported to the microbiology laboratory. The non-centrifuged portion of the conventional sample was aspirated and inoculated onto culture media [20].

Culture Conditions:

- Conventional culture: Inoculation onto blood agar, MacConkey agar, and Brucella agar; incubation at 37°C for up to 7 days under aerobic and anaerobic conditions [20].

- ABCS: Use of BACT/ALERT 3D and VIRTUO systems with aerobic and anaerobic bottles; incubation at 37°C for up to 7 days with terminal subculture [20].

Organism Identification: Positive samples underwent species identification using VITEK 2 and VITEK MS systems [20].

Data Analysis: Comparison of detection rates, time to positivity, and organism identification between methods, with statistical analysis using Pearson χ² test and Student's t-test [20].

This protocol demonstrated that ABCS detected 52.2% more positive cases than conventional culture alone, with particular advantage for streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, and Klebsiella species [20].

Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS) Protocol

A novel approach combining culturomics with metagenomic sequencing was developed to maximize microbial detection from complex samples [19]:

Sample Preparation: Fresh fecal sample (0.5g) was homogenized with 4.5g distilled water, with serial dilutions (10⁻³ to 10⁻⁷) prepared in 0.85% NaCl solution [19].

Multi-Media Cultivation: 200μL of each dilution was plated on 12 different media types, including nutrient-rich media (LGAM, PYG), selective media (PGAM, DGAM), and oligotrophic media (1/10GAM) [19].

Incubation Conditions: Duplicate sets were incubated aerobically and anaerobically at 37°C for 5-7 days using an anaerobic chamber with 95% nitrogen and 5% hydrogen atmosphere [19].

Sample Processing:

- Experienced Colony Picking (ECP): Traditional selection of distinctive colonies for purification and identification [19].

- Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS): All colonies from each medium were pooled, harvested using cell scrapers, and processed for DNA extraction [19].

- Culture-Independent Metagenomic Sequencing (CIMS): Direct metagenomic sequencing of original fecal sample [19].

DNA Sequencing and Analysis: Shotgun metagenomic sequencing using Illumina HiSeq 2500, generating 100bp paired-end reads with average 6.73Gb data per sample. Taxonomic profiling using HUMANN2 with MetaPhlAn2 [19].

This protocol revealed that CEMS and CIMS identified complementary microbial communities with only 18% species overlap, demonstrating their synergistic value in comprehensive microbiome analysis [19].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| BACT/ALERT Culture Bottles (bioMérieux) | Supports microbial growth with nutrient media in automated detection systems | Automated blood culture systems for sterile body fluids [20] |

| Lymphoprep (STEMCELL Technologies) | Density gradient medium for cell separation | Smart centrifugation protocols for bacterial isolation from blood [15] |

| Propidium Monoazide | DNA-binding dye that penetrates only dead cells | Viability qPCR to distinguish live/dead microorganisms [12] |

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) | DNA extraction from complex biological samples | Metagenomic sequencing from fecal samples [19] |

| Fungitell Assay (Associated Cape Cod) | Detection of (1→3)-β-D-glucan in serum | Diagnosis of invasive fungal infections [11] |

| Platelia Galactomannan EIA (Bio-Rad) | Enzyme immunoassay for aspergillus antigen | Diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis [11] |

| GasPak EZ Anaerobe Pouch (BD) | Creates anaerobic environment for cultivation | Anaerobic bacterial culture [21] |

| Hubix Culture Bottles (HUFIT Inc.) | Culture media for novel continuous monitoring systems | Bacterial growth detection in automated systems [21] |

Workflow Visualization: Methodological Pathways

The diagnostic and research pathways for culture and non-culture methods involve distinct procedural steps with significant implications for time investment and information output. The following workflow diagrams illustrate these processes.

Culture vs. Non-Culture Workflow Comparison

The fundamental distinction between these paradigms lies in their core detection principles: culture methods depend on biological amplification (microbial growth), while non-culture methods utilize technological amplification (molecular or signal detection). This distinction drives their differential performance in speed, sensitivity, and application scope.

Integrated Approaches and Future Directions

The comparative analysis reveals that culture and non-culture methods offer complementary rather than mutually exclusive approaches. Integrated methodologies that leverage the strengths of both paradigms represent the future of microbiological diagnostics and research [17] [19]. Culture-enriched metagenomic sequencing exemplifies this integration, demonstrating superior microbial diversity detection compared to either method alone [19].

Emerging trends include automation of traditional culture processes [12], artificial intelligence integration for MALDI-TOF spectrum interpretation [12], and development of rapid culture-free detection systems for sepsis diagnosis [15]. These innovations aim to bridge the performance gap between paradigms while maintaining the unique benefits of each approach. For pharmaceutical and research applications, methodological selection should be guided by specific requirements for speed, sensitivity, characterization depth, and actionable results, with increasingly sophisticated integrated systems offering pathways to optimize across all these dimensions.

Understanding the 'Gold Standard' Concept in Microbiology

In clinical and research microbiology, the 'gold standard' refers to the diagnostic test or benchmark that is the best available under reasonable conditions against which new tests are compared to gauge their validity and efficacy [22]. This concept is fundamental yet dynamic, as technological advancements continuously redefine the benchmarks for accuracy. The central thesis of modern microbiological testing hinges on the comparison between traditional culture-based methods—long considered the archetypal gold standard—and rapidly evolving non-culture methods such as molecular diagnostics. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this dichotomy is crucial for selecting appropriate methodologies, interpreting data accurately, and driving diagnostic innovation. This guide provides an objective comparison of these paradigms, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Defining the Gold Standard and its Imperfections

A hypothetical ideal gold standard test possesses 100% sensitivity (identifying all true positives) and 100% specificity (identifying all true negatives) [22]. In practice, however, no test is perfect, and the designation of "gold standard" is context-dependent, representing the best available option that is practically achievable [23].

The table below outlines core characteristics of an ideal gold standard versus practical realities:

| Characteristic | Ideal Gold Standard | Practical/Imperfect Gold Standard ("Alloyed Gold") |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 100% (No false negatives) | High, but less than 100% |

| Specificity | 100% (No false positives) | High, but less than 100% |

| Real-World Example | Theoretical benchmark | Blood culture for enteric fever [24], Microbial culture for many bacterial pathogens [25] [3] |

| Key Limitation | Unattainable in practice | Performance can be affected by sample quality, prior antibiotic use, and the inherent limitations of the method itself [25]. |

This concept is critically linked to ground truth, which is the underlying absolute state of information. The gold standard is the best effort to approximate this ground truth [22] [23]. In many cases, a Composite Reference Standard (CRS) is employed, which combines the results of two or more diagnostic tests to define the final diagnosis when a single perfect test is unavailable [24].

Direct Comparison: Culture vs. Non-Culture Methods

The following tables summarize the comparative performance of traditional culture and modern non-culture methods across key parameters and specific pathogens.

| Parameter | Culture-Based Methods | Non-Culture Methods (e.g., NAATs, Multiplex PCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Growth and isolation of viable microorganisms on or in nutrient media [3]. | Detection of pathogen-specific biomarkers, most commonly nucleic acids [3]. |

| Turnaround Time | Long (24 hours to several days or weeks) [3]. | Rapid (hours to same-day) [3]. |

| Analytical Sensitivity | Lower; requires viable organisms in sufficient quantity. | Higher; can detect non-viable or low-load pathogens [3]. |

| Ability to Detect Novel/Unculturable Pathogens | No, only organisms that can be grown under the laboratory conditions used. | Yes, if the genetic target is known [25]. |

| Key Advantage | Provides a live isolate for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) and strain typing for public health surveillance [3]. | High throughput, ability to test for multiple pathogens simultaneously (multiplexing), and superior speed [3]. |

| Major Drawback | Slow, labor-intensive, and fails to identify difficult-to-culture microorganisms [3]. | Does not provide a live isolate for AST without reflex culture [26] [3]. Positive results may detect non-viable organisms or clinical significance may be uncertain [26]. |

Table 2: Performance Data from Comparative Studies

| Infectious Disease / Pathogen | Gold Standard | Comparative Method | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enteric Fever (Salmonella spp.) [24] | Blood Culture | Tube Widal & Dot Blot Assay | Blood culture sensitivity was low (9.81% positivity), specific at 100%. Dot Blot IgM showed higher sensitivity (71.15%) but lower specificity (10.16%) against a Composite Reference Standard. |

| Campylobacter Enteritis [3] | Culture | PCR | In a study of 400 specimens, PCR identified 41 positives. Culture only detected 21 of these, yielding a culture sensitivity of 51.2% compared to PCR. |

| Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections (NSTI) [25] | Culture | Multiple Molecular Methods (16S rRNA sequencing, etc.) | Culture identified microbes in 70% of surgical samples. Molecular methods identified microorganisms in 90% of samples and frequently detected additional, unexpected pathogens. |

| Polymicrobial Urinary Tract Infections [3] | Urine Culture | Multiplex PCR | In 175 patients with polymicrobial infections, PCR detected 95% of cases, while culture only reported 22%. PCR also revealed polymicrobial infections in 67 patients with negative culture results. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and critical evaluation, detailed methodologies from key cited studies are outlined below.

Objective: To isolate and identify Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi or Paratyphi from the blood of suspected enteric fever patients.

Workflow:

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Culture Medium: Brain Heart Infusion Broth with SPS (sodium polyanethol sulfonate) as an anticoagulant and anticoagulant [24].

- Sub-culture Media: Blood Agar and MacConkey Agar [24].

- Identification Tools: Standard biochemical test reagents (e.g., for lactose fermentation, gas production) and specific antisera for sero-agglutination confirmation [24].

- Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Mueller-Hinton Agar and antibiotic discs for Kirby Bauer disc diffusion method [24].

Objective: To define a confirmed case of enteric fever in the absence of a single perfect test, using multiple component tests.

Workflow:

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Component Tests: All reagents for blood culture, Tube Widal test, and Dot Enzyme Immunoassay (Dot EIA) for Salmonella-specific IgM and IgG [24].

- Data Integration Framework: A pre-defined statistical or rule-based framework (e.g., the "two-test criteria") for combining results from the component tests to yield a final CRS outcome [24].

Objective: To quantify live Campylobacter cells in a sample, differentiating them from dead, membrane-compromised cells, thereby challenging the CFU gold standard.

Workflow:

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Propidium Monoazide (PMA): A DNA-intercalating crosslink agent that penetrates only dead, membrane-compromised cells. Upon light exposure, it covalently cross-links the DNA, rendering it non-amplifiable in subsequent qPCR [27].

- Internal Sample Process Control (ISPC): A known number of dead cells from a different species (e.g., C. sputorum) added to the sample to monitor the efficiency of PMA treatment and compensate for DNA loss during processing [27].

- qPCR Reagents: Primers and probes specific for thermophilic Campylobacter, the ISPC, and an Internal Amplification Control (IAC) to detect PCR inhibition [27].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key reagents and their critical functions in the methodologies discussed.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Selective Culture Media (e.g., with antibiotics) | Suppresses the growth of competing flora to allow isolation of fastidious pathogens like Campylobacter [3]. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | Used in live/dead differentiating qPCR to inhibit amplification of DNA from dead cells, ensuring quantification of viable pathogens [27]. |

| Internal Sample Process Control (ISPC) | Monitors efficiency of sample processing steps (e.g., DNA extraction, PMA treatment) and corrects for sample-derived inhibition or losses [27]. |

| Target-Specific Primers/Probes | For NAATs; ensure high specificity by binding to unique genetic sequences of the target pathogen (e.g., Salmonella Typhi, C. jejuni) [25] [3]. |

| Polyvalent Antisera | For serological agglutination tests (e.g., Widal, serotyping) to identify specific bacterial serovars based on surface antigen reactions [24]. |

The concept of a gold standard in microbiology is not static. While culture remains an indispensable tool for obtaining live isolates for antimicrobial susceptibility testing and epidemiological typing, its role as the undisputed gold standard is being redefined [3]. Molecular methods, particularly NAATs, offer superior speed, sensitivity, and the ability to detect difficult-to-culture pathogens, establishing themselves as the new gold standard for certain infections, especially viral ones [26].

The future of microbiological diagnostics lies in a synergistic approach. Reflex culture—where samples positive by a rapid, sensitive molecular test are subsequently cultured—is a recommended strategy to harness the speed of molecular methods while retaining the phenotypic information provided by culture [26] [3]. For researchers and drug developers, the choice between methods must be guided by the specific question at hand, whether it is rapid detection, outbreak tracing, or antimicrobial stewardship, with a clear understanding of the strengths and limitations inherent in each technological paradigm.

The Critical Role of Culture in Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

In the global fight against antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which is responsible for millions of deaths annually, antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) stands as a critical line of defense [28]. AST guides effective antimicrobial therapy, balancing optimal patient outcomes with the need to minimize selection pressure that drives AMR [29]. The core principle of AST is to expose a pathogen isolated from a patient to antimicrobial agents to determine the most effective treatment [29]. While novel, rapid methods are emerging, microbial culture remains the foundational step for phenotypic AST. This article objectively compares culture-based AST methods with emerging non-culture alternatives, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of culture versus non-culture microbiological test methods.

A Comparative Analysis of AST Methodologies

AST methods can be broadly categorized into classical culture-based, automated culture-based, and non-culture molecular techniques. Each offers distinct advantages and limitations in turnaround time, cost, and informational value.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Methods

| Method Category | Examples | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Turnaround Time | Information Provided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Culture-Based | Disk Diffusion, Agar/Broth Dilution [28] | Low cost, flexible, provides phenotypic result (what actually happens) [28] | Time-consuming, requires prior bacterial isolation [28] | 18–24 hours or longer after isolation [28] | Qualitative (S/I/R) or Quantitative (MIC) [28] |

| Automated Culture-Based | Automated Blood Culture Systems (BACT/ALERT VIRTUO) [20] | Higher sensitivity, faster than some manual methods, standardized [20] | Higher instrument costs, limited agent selection | 6–24 hours after initial isolation [28] | Quantitative (MIC) |

| Non-Culture Molecular | PCR, Genetic Probe Assays [28] | Rapid, direct from specimen, high throughput [28] | Detects only known resistance mechanisms, may overestimate resistance [28] | ~1–6 hours [28] | Detection of specific resistance genes (e.g., mecA, ESBL genes) [28] |

Experimental Data: Showcasing the Sensitivity of Automated Culture

A 2021 retrospective study of over 9,000 patients compared conventional pleural fluid culture with automated blood culture systems (ABCS) like BACT/ALERT [20]. The results demonstrate a significant performance enhancement offered by modern culture technology.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data: Conventional vs. Automated Culture

| Testing Parameter | Conventional Culture | Automated Blood Culture System (ABCS) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Positive Patients | 302 (47.8%) | 632 (100%) |

| Exclusive Positivity Rate | Not Applicable | 330 (52.2%) |

| Common Organisms Detected | Varies | Viridans group streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella spp. [20] |

| Associated Patient Factors | Higher CRP, Lower glucose [20] | Lower CRP, Higher glucose [20] |

Experimental Protocol for Culture Comparison [20]: Pleural fluid samples were divided at the bedside. For ABCS, 5-10 mL was inoculated into each aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottle (BACT/ALERT 3D or VIRTUO). For conventional culture, another 5-10 mL was placed in a sterile tube. Conventional culture used solid media (blood agar, MacConkey agar, Brucella agar) incubated aerobically and anaerobically at 37°C for up to 7 days. ABCS bottles were incubated at 37°C for up to 7 days. Identification and susceptibility testing used VITEK 2 or VITEK MS systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of reliable AST, whether for clinical diagnostics or pharmaceutical development, depends on a suite of essential reagents and instruments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for AST

| Item | Function/Application in AST | Key Players/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Provides nutrients for microbial growth; essential for phenotypic results [30] | Chocolate Agar, Nutrient Broth, Tryptic Soy Broth [31] |

| Automated Culture Systems | Enhances diagnostic sensitivity and standardization for sterile body fluids [20] | BACT/ALERT VIRTUO (bioMérieux) [20] |

| Identification & Susceptibility Systems | Provides species identification and MIC-based susceptibility profiles [20] | VITEK 2, VITEK MS (bioMérieux) [20] |

| Antimicrobial Discs | Used in disk diffusion method to determine susceptibility categorically [28] | Various manufacturers (e.g., BD, bioMérieux) |

| Microdilution Trays | Used in broth microdilution to determine Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) [28] | Custom or pre-made panels for automated systems |

Innovation and Workflow in Modern AST

The Personalized AST Workflow

Emerging research focuses on making AST more precise and efficient by moving away from one-size-fits-all panels. The following diagram illustrates a novel, data-driven workflow for personalized AST.

Diagram Title: Personalized AST Clinical Prediction Workflow

This personalized approach uses clinical prediction models that incorporate variables like prior antimicrobial resistance, recent antibiotic treatment, and patient age to predict the probability of susceptibility for a given antibiotic [29]. If an antibiotic from the WHO "Access" category (those least likely to induce resistance) has a predicted susceptibility probability greater than 50%, it is automatically added to the test panel [29]. This method has been shown in simulation studies to provide more susceptible results for Access category antibiotics than standard fixed-panel approaches, directly supporting antimicrobial stewardship goals [29].

The Broader Diagnostic Pathway

The role of culture becomes even more critical when viewed as part of the complete diagnostic pathway, where it interacts with and validates other testing methods.

Diagram Title: Integrated Culture and Molecular AST Pathway

Despite the rapid advancement of molecular techniques, microbial culture remains the irreplaceable cornerstone of phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing. It provides the direct, observable evidence of how a pathogen responds to an antimicrobial agent—the phenotypic reality that genotypic methods can only predict. While molecular methods offer unparalleled speed for detecting known resistance mechanisms, they cannot replace the comprehensive insight gained from culture, especially for detecting novel resistance patterns. The future of AST lies not in the displacement of culture, but in its integration with novel technologies and data-driven approaches, creating a synergistic workflow that maximizes speed, accuracy, and clinical relevance in the ongoing battle against antimicrobial resistance.

Methodological Deep Dive: Applications of Culture and Non-Culture Tests in Research and Diagnostics

Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAATs) have revolutionized diagnostic microbiology by providing rapid, sensitive, and specific detection of pathogens that traditional culture-based methods often miss. The evolution from conventional culture techniques to molecular methods represents a paradigm shift in clinical microbiology, enabling detection of non-culturable, fastidious, or slow-growing microorganisms [32] [33]. While culture remains valuable for antibiotic susceptibility testing and serves as an enrichment technique, it demonstrates limited effectiveness for anaerobic, low-abundance, and slow-growing organisms [33]. The COVID-19 pandemic particularly highlighted the crucial role of NAATs, with methods like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing becoming essential for diagnosis and management [34].

NAAT technologies have diversified significantly, with multiplex panels and real-time applications emerging as powerful tools for syndromic testing. These advancements allow simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens in a single reaction, substantially improving diagnostic efficiency for infections with overlapping clinical presentations [35] [36]. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of various NAAT platforms, focusing on their applications, limitations, and experimental validation in clinical settings.

Performance Comparison of NAAT Modalities

The diagnostic landscape features several NAAT approaches with distinct performance characteristics, applications, and technical requirements. The table below provides a comparative analysis of major NAAT modalities based on recent clinical studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of NAAT Technologies in Clinical Diagnostics

| Technology | Targets/Specific Examples | Sensitivity & Specificity | Limit of Detection | Multiplexing Capacity | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex Real-time RT-PCR | Respiratory viruses (SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A/B, RSV) [35] | 100% PPA and NPA for all targets compared to reference assays [35] | 3,333-8,333 copies/mL depending on target [35] | Moderate (3-4 targets typically) | High throughput, automated sample-to-result platform [35] | Limited targets per reaction compared to advanced multiplexing |

| Melting-Curve-Based Multiplex qPCR | SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A, HRSV, HRV-B [36] | 100% concordance with commercial kits [36] | 10 copies/reaction for all targets [36] | Moderate (4 targets demonstrated) | 100% specificity in validation; no cross-reactivity [36] | Requires optimization to maintain distinct melting temperatures |

| High-Plex PCR with Machine Learning | 7 respiratory pathogens simultaneously [37] | Accurate classification using amplification curve analysis [37] | Not specified | High (7-plex demonstrated) | Single fluorescent channel detection; reduced reagent costs [37] | Complex bioinformatics pipeline required |

| Metagenomic NGS (wcDNA) | Broad pathogen detection (bacterial, fungal, viral) [33] | 74.07% sensitivity, 56.34% specificity vs. culture [33] | Varies by pathogen abundance | Very high (unbiased detection) | Culture-independent; detects uncultivable organisms [33] | High host DNA background; compromised specificity |

| Fungal Multiplex Real-time PCR | Aspergillus fumigatus, A. terreus, Candida albicans, C. glabrata [38] | 100% specificity across 65 organisms tested [38] | 100 pg/μL (10⁶ copies/μL) [38] | Moderate (4 targets demonstrated) | Rapid 3-hour detection; identifies non-viable organisms [38] | Higher detection limit than bacterial assays |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multipreal-time RT-PCR for Respiratory Pathogens

The analytical performance evaluation of the LabTurbo multiplex real-time RT-PCR kit exemplifies a standardized approach for respiratory pathogen detection [35]. This cross-sectional study conducted from September to November 2023 utilized 350 nasopharyngeal swab samples (250 positive cases and 100 negative cases) collected in universal transport medium and stored at -80°C until analysis. The protocol employed the LabTurbo platform for simultaneous detection of SARS-CoV-2, influenza A/B, and RSV, with comparison to reference assays (Cobas Liat SARS-CoV-2 influenza A/B assay and Cobas influenza A/B and RSV assays). For limit of detection (LOD) determination, RNA standards were serially diluted and tested with the LabTurbo kit, establishing LODs ranging from 3,333 copies/mL for influenza A to 8,333 copies/mL for SARS-CoV-2 and RSV [35]. The study demonstrated 100% positive percent agreement (PPA) and negative percent agreement (NPA) with reference methods, confirming robust diagnostic performance.

Melting-Curve-Based Multiplex Assay Development

The development of a melting-curve-based multiplex real-time PCR (M-m-qPCR) assay illustrates a targeted approach for respiratory virus detection [36]. Researchers designed primers targeting the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein N of SARS-CoV-2, the Matrix protein 2 of Influenza A virus, the RdRp domain of the L protein from Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus, and the polyprotein from Rhinovirus B genes. The analytical validation included in silico analysis and testing against a panel of reference and clinical strains encompassing viral, bacterial, and fungal pathogens, demonstrating 100% specificity. The assay achieved a detection limit of 10 copies per reaction for all targets using positive controls and was further validated in simulated nasal fluid before clinical testing on 811 nasopharyngeal swabs [36]. This comprehensive validation framework ensures reliable performance across diverse clinical scenarios.

Smart-Plexer: Hybrid Multiplex Assay Development

The Smart-Plexer workflow represents a breakthrough in multiplex assay development through its hybrid approach that couples empirical testing of singleplex assays with computer simulation [37]. This method addresses the fundamental challenge in multiplex development where the number of possible assay combinations increases exponentially with the number of targets. The process involves:

- Singleplex Data Collection: Running real-time PCR reactions with individual primer sets and targets.

- Curve Processing: Background subtraction, removal of late amplification curves, and elimination of noisy curves.

- Sigmoidal Fitting: Applying a five-parameter model to normalize curve data.

- Distance Calculation: Computing kinetic inter-target distances between amplification curves.

- Combination Ranking: Ranking simulated multiplex combinations based on average distance scores (ADS) and minimum distance scores (MDS).

- Empirical Validation: Laboratory testing of top-ranked combinations with machine learning classification via Amplification Curve Analysis (ACA).

This workflow successfully developed a 7-plex assay for respiratory pathogens using a single fluorescent channel, dramatically reducing development time and resources [37].

Figure 1: Smart-Plexer computational-experimental workflow for developing multiplex PCR assays.

Advanced Applications and Innovative Approaches

Digital Technologies and Machine Learning in Multiplexing

Recent innovations have leveraged digital technologies to overcome traditional limitations in multiplex qPCR. Machine learning (ML) algorithms applied to amplification and melting curves (AC and MC) enable accurate classification of multiple nucleic acid targets in single reactions [39]. This data-driven approach enhances multiplexing capabilities without requiring sophisticated instrumentation or complex fluorescent probe systems. The integration of knowledge-based and data-driven software solutions creates an end-to-end framework for streamlined assay design and improved target detection accuracy [39]. These computational advances are particularly valuable for expanding diagnostic capacity in resource-limited settings where traditional multiplex equipment may be cost-prohibitive.

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) represents the most comprehensive NAAT approach, enabling unbiased detection of known and novel pathogens without prior targeting [33]. Comparative studies of whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) mNGS versus cell-free DNA (cfDNA) mNGS reveal important performance differences: wcDNA mNGS demonstrates superior sensitivity (74.07% vs. 46.67% concordance with culture) and lower host DNA background (84% vs. 95% host DNA) [33]. However, this enhanced sensitivity comes with compromised specificity, requiring careful interpretation in clinical practice. mNGS excels in detecting polymicrobial infections and identifying fastidious organisms that evade conventional diagnostic methods, positioning it as a powerful tool for complex diagnostic scenarios.

Antimicrobial Resistance Detection

NAATs have expanded beyond simple pathogen detection to encompass antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiling. A four-color multiplex real-time PCR assay for Mycoplasma genitalium demonstrates this application by simultaneously detecting the pathogen and azithromycin-resistance mutations in the 23S rRNA gene [40]. This approach enables targeted antibiotic therapy selection, directly addressing the global challenge of macrolide-resistant M. genitalium. Similarly, next-generation sequencing facilitates genomic antimicrobial susceptibility testing (gAST) by detecting resistance genes in bacterial whole genome sequences [32]. While gAST cannot yet replace phenotypic methods entirely due to technical complexity and interpretation challenges, it provides valuable insights for antimicrobial stewardship programs.

Figure 2: Evolution of diagnostic testing from traditional culture to advanced genotypic resistance detection.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of NAAT technologies requires specific reagent systems tailored to each application. The table below details key research solutions and their functions in nucleic acid amplification testing.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NAAT Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Large Volume Kit [40], Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit [40] [38], VAHTS Free-Circulating DNA Maxi Kit [33] | Isolation of DNA/RNA from clinical specimens; critical for assay sensitivity | wcDNA extraction shows superior sensitivity vs. cfDNA for mNGS [33] |

| PCR Master Mixes | Path-ID Multiplex One-Step RT-PCR Kit [40], TaqMan-based chemistries [37] | Enzymatic amplification with reverse transcription capability | Compatible with multiplex real-time platforms |

| Specific Primers/Probes | Species-specific oligonucleotides targeting bgt1, benA, ITS2, LEU2 genes [38], RdRp, N protein, M2 protein [36] | Target-specific amplification and detection | Designed with stringent specificity validation; ΔG values critical for multiplexing [38] |

| Internal Controls | Extraction & Inhibition Control (EIC), Universal Inhibition Control (UIC) [40], human RNase P gene [36] | Process control for extraction efficiency and amplification inhibition | Essential for distinguishing true negatives from assay failures |

| Transport Media | Universal Transport Medium (Libo) [35], ESwab Liquid Amies Collection System [40] | Sample preservation during storage and transport | Critical for maintaining nucleic acid integrity before testing |

| Digital PCR Reagents | Customized chemistries for Smart-Plexer workflow [37] | Enables amplification curve analysis for machine learning classification | Fundamental for data-driven multiplexing approaches |

NAAT technologies represent a dynamic and rapidly evolving field that continues to transform clinical microbiology diagnostics. From singleplex PCR to sophisticated multiplex panels and metagenomic sequencing, each approach offers distinct advantages for specific diagnostic scenarios. Multiplex real-time PCR excels in targeted syndromic testing with excellent sensitivity and specificity, while mNGS provides comprehensive unbiased detection at the cost of greater complexity and interpretation challenges. Innovations in digital PCR, machine learning, and computational assay design are pushing multiplexing capabilities beyond traditional limits, creating new possibilities for efficient, cost-effective pathogen detection. The ongoing integration of genotypic resistance testing further expands the clinical utility of NAAT platforms, enabling more targeted therapeutic interventions. As these technologies continue to mature, they promise to enhance diagnostic precision, outbreak management, and antimicrobial stewardship efforts in increasingly sophisticated healthcare environments.