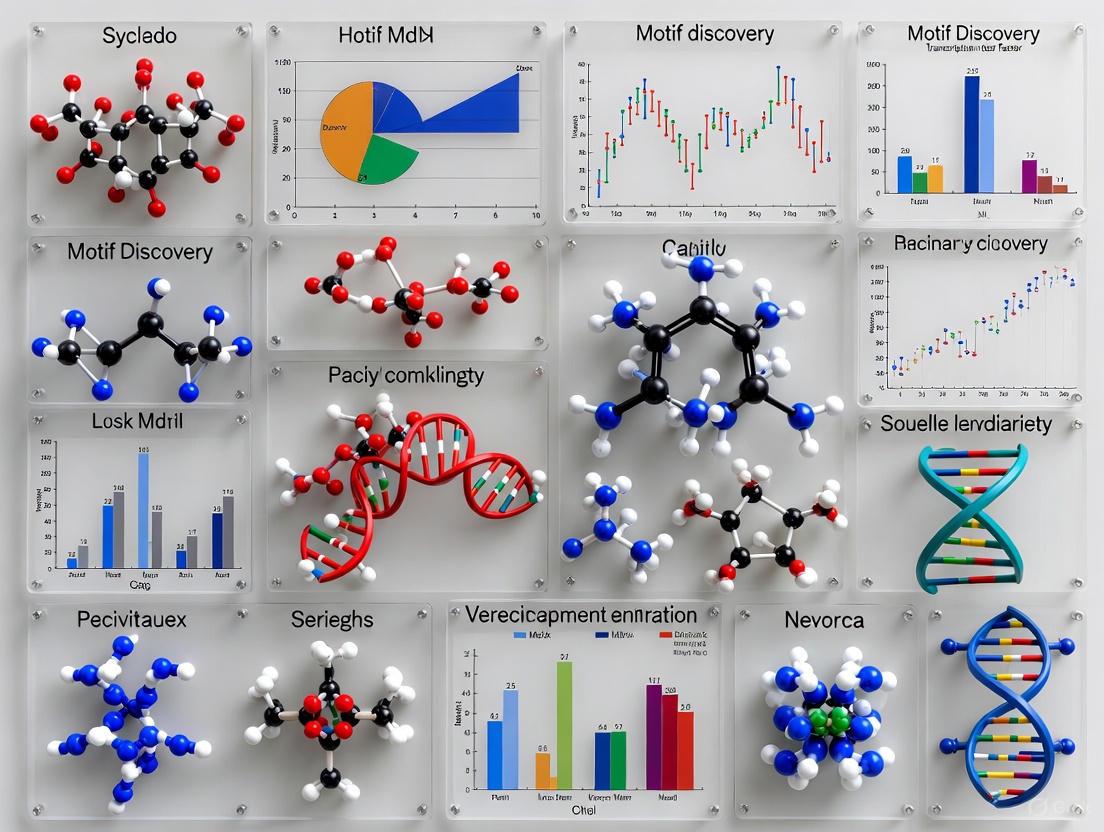

Beyond the Consensus: Advanced Strategies for Degenerate Transcription Factor Binding Site Discovery

This article addresses the critical challenge of identifying degenerate transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs), short DNA sequences essential for gene regulation that exhibit high sequence variability.

Beyond the Consensus: Advanced Strategies for Degenerate Transcription Factor Binding Site Discovery

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of identifying degenerate transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs), short DNA sequences essential for gene regulation that exhibit high sequence variability. We explore the biological significance of these low-affinity sites, which are often non-randomly clustered and evolutionarily conserved, and their implications for understanding transcriptional specificity. A comprehensive overview of current computational methods—from combinatorial algorithms and machine learning approaches to integrated web platforms—is provided. The article further delivers practical optimization strategies, including the use of degenerate position-specific models and background sequence selection, and concludes with rigorous cross-platform validation techniques and benchmark studies to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the most effective tools for their experimental data.

The Landscape of Degeneracy: Why Variable TFBSs Are Functionally Crucial

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a degenerate motif and how does it differ from a simple consensus sequence? A degenerate motif represents a pattern in biological sequences where certain positions can tolerate multiple nucleotides. Unlike a simple consensus sequence, which shows only the most frequent nucleotide at each position, a degenerate motif captures this variability. For example, while a consensus might be "TACGC", the degenerate consensus could be "WACVC", where 'W' stands for A or T, and 'V' for A, C, or G, following IUPAC ambiguity codes [1] [2]. This provides a more realistic representation of natural binding sites that are often flexible.

2. When should I use a Position Weight Matrix (PWM) over a degenerate consensus sequence? PWMs are superior for most analytical purposes because they quantify the relative preference for each nucleotide at every position, rather than just showing the possibilities. They are used for sensitive scanning of genomic sequences to find potential transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) [3]. Use a degenerate consensus for a quick, human-readable summary of the motif, but a PWM when you need to compute a similarity score for any given DNA sequence, which is essential for predicting novel binding sites.

3. My motif discovery tool outputs a PWM, but I'm getting too many false positive matches. How can I improve specificity? This is a common challenge, as many existing PWMs provide low specificity [3]. You can:

- Optimize the score threshold: Use methods like those by Bucher to determine the optimal cutoff value for your specific PWM and application [3].

- Use an improved background model: Instead of a uniform background, use a model that reflects the nucleotide composition of your target sequences (e.g., promoters). Some tools allow for dinucleotide-preserving shuffling or the use of pre-compiled background sequences for your species [4] [5].

- Employ a more advanced algorithm: Consider tools that build 16-row dinucleotide matrices which account for dependencies between adjacent nucleotides, as they can provide better results than standard 4-row matrices [3].

4. What does the information content or height in a sequence logo represent? In a sequence logo, the total height of the stack at each position represents the information content in bits, which indicates sequence conservation [6] [7]. A taller stack means a more conserved position. The height of each individual letter within the stack is proportional to its relative frequency at that position [6]. This provides an intuitive visualization of both the conservation and the nucleotide composition of the motif.

5. How can I handle low-count data when building a PWM to avoid overfitting? Applying a pseudocount is the standard method to correct for a small number of observations. This involves adding a small, predetermined value to the count of each nucleotide at every position before calculating frequencies [1] [7]. This prevents probabilities from being zero and stabilizes the PWM. Many tools, like Seq2Logo, incorporate this automatically, often using a Blosum62 matrix for protein motifs or a simple fraction of the total count for DNA [1] [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental and Analytical Issues

Table 1: Common Issues and Solutions in Motif Analysis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low specificity (many false positives) | Suboptimal PWM score threshold; inappropriate background model. | Optimize cutoff using methods like Bucher's [3]; use a matched background sequence set (e.g., with HOMER2's background model) [5]. |

| Weak or no motif found in ChIP-Seq peaks | The TF may bind indirectly or have a highly degenerate motif; the dataset may be noisy. | Try multiple de novo discovery tools (MEME, Weeder, ChIPMunk) and compare results [4]. Use stricter peak calling or focus on high-confidence peaks. |

| Inconsistent motifs across different experimental platforms (e.g., ChIP-Seq vs. PBM) | Technical biases inherent to each platform [8]. | Perform cross-platform benchmarking. Use a consensus PWM from tools that perform well across multiple data types, as demonstrated in large-scale studies [8]. |

| Sequence logo does not reflect biological expectations | Incorrect handling of sequence redundancy or low counts. | Apply sequence weighting (e.g., Hobohm algorithm) to reduce redundancy and use pseudocounts [7]. |

| Difficulty visualizing custom PWMs | Using a tool that only accepts multiple sequence alignments as input. | Use a flexible logo generator like Logomaker in Python, which can create logos directly from a count matrix or PWM [9]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Creating a PWM from Sequence Instances using Biopython

This protocol is used when you have a set of aligned DNA sequences (instances) of a binding site.

- Input Preparation: Compile your aligned sequence instances in FASTA format or as a simple list. Ensure all sequences are the same length.

- Create Motif Object: Use the

Bio.motifsmodule in Biopython to create a motif object from the instances. - Access Counts Matrix: The counts matrix is automatically calculated and stored in

motif.counts[1] [2]. - Generate Consensus Sequences: Obtain the simple and degenerate consensus sequences.

- Calculate the PWM: The counts matrix can be normalized and converted to a position frequency matrix (PFM), and then log-odds transformed to create a PWM, using a background nucleotide distribution.

Protocol 2:De NovoMotif Discovery from ChIP-Seq Peaks using HOMER

This is a standard workflow for finding novel motifs enriched in genomic regions.

- Input Preparation: Have your genomic regions of interest (e.g., ChIP-Seq peaks) in BED format.

- Run HOMER: Use the

findMotifsGenome.plscript. HOMER is a differential algorithm designed to find motifs enriched in one set (target) versus another (background) [5].peaks.bed: Your file of genomic coordinates.hg38: Reference genome.-size 200: Region size around the center of each peak to analyze.-bg background.bed: (Optional) A custom set of background regions. HOMER will automatically generate one if not provided.

- Interpret Output: HOMER will output several files, including HTML reports with sequence logos, PWMs, and statistical significance for each discovered motif.

Protocol 3: Improving an Existing PWM with Promoter Data

This advanced protocol, based on published research, iteratively refines a PWM using a database of promoter sequences expected to be enriched for functional binding sites [3].

- Gather Inputs: You need an initial PWM (or consensus), a control set of known experimental binding sites, and a database of promoter sequences (e.g., from EPD).

- Extract Putative Sites: Scan the promoter database with your initial PWM to extract a set of putative binding sites.

- Build a New PWM: Use the extracted sites to build a new PWM. The formula used often includes a smoothing parameter

s_ito handle low counts [3]: ( w{bi} = \ln(\frac{n{bi}}{e{bi}} + si) + c_i ) wheren_biis the count of basebat positioni,e_biis its expected frequency,s_iis a smoothing pseudocount, andc_iis a column-specific constant. - Benchmark and Iterate: Evaluate the new PWM's performance (e.g., using correlation coefficient considering both sensitivity and specificity) against the control set. Iterate steps 2 and 3 until the performance converges on an optimal PWM [3].

Workflow and Logical Diagrams

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Degenerate Motif Analysis

| Tool Name | Type / Function | Key Features and Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bio.motifs (Biopython) [1] [2] | Python API for motif manipulation | Programmatic creation of motifs from instances; calculation of counts, consensus, and reverse complements. Ideal for custom pipelines. |

| HOMER [5] | De novo motif discovery | Differential motif discovery designed for ChIP-Seq; uses hypergeometric distribution for enrichment; accounts for sequence bias. |

| MEME Suite [8] | De novo motif discovery | Classic, widely-used algorithm for finding enriched, ungapped motifs in a set of sequences. |

| JASPAR/TRANSFAC [4] [2] | Databases of known motifs | Curated, non-redundant collections of transcription factor binding models (PWMs) for known motif scanning. |

| Seq2Logo/Logomaker [7] [9] | Sequence logo generation | Seq2Logo (web) and Logomaker (Python) create customizable, publication-quality logos from alignments or matrices. |

| STAMP [4] | Motif comparison and clustering | Tool for comparing and merging motifs from different sources based on similarity. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Degenerate Site Analysis

Q1: What constitutes a "degenerate" transcription factor binding site (TFBS), and why is it challenging to study? A degenerate TFBS is a DNA sequence recognized by a transcription factor that shows significant variation from a canonical consensus sequence. Unlike a simple, highly conserved motif, a degenerate motif contains several positions that can tolerate different nucleotides while still facilitating functional binding. This high degree of sequence variation makes them difficult to distinguish from random genomic background using standard motif discovery tools, which often assume a more defined, conserved pattern [10] [11].

Q2: What is the biological evidence for the non-random nature of degenerate sites? Research on factors like REST, c-myc, p53, HNF-1, and CREB has revealed that highly degenerate TFBS-like sequences are not randomly distributed across the genome. Instead, they show significant enrichment in the genomic regions surrounding the cognate, high-affinity binding sites. This non-random clustering suggests these degenerate sites form a favorable genomic landscape that may guide transcription factors to their functional targets [10].

Q3: How does evolutionary conservation provide evidence for the functional importance of degenerate sites? Comparative genomics studies of orthologous promoters in human, mouse, and rat have demonstrated that highly degenerate sites are conserved at a rate significantly higher than expected by random chance. This evolutionary conservation indicates that these sequences are under purifying selection, implying they provide a functional advantage that has been maintained over millions of years [10].

Q4: My de novo motif finding results include low-complexity or simple repeat sequences. Are these real motifs? Not necessarily. Motifs that show simple nucleotide repeats or low-complexity patterns (e.g., AAAAAA, CGCGCG) often arise from systematic biases in your target sequences compared to the background. They are frequently classified as poor-quality motifs. To address this:

- Ensure your background sequences are appropriately matched to your target sequences (e.g., promoters vs. promoters).

- Use the

-gcor-cpgoptions in HOMER to normalize for GC or CpG content. - Consider using autonormalization options like

-olento more aggressively normalize sequence bias [12] [13].

Q5: How can I judge the quality of a motif discovered de novo before reporting it? Always visually inspect the motif alignment. A motif finding tool may assign a known factor's name to your de novo motif with a very low p-value, but the alignment might show that the found motif only corresponds to a peripheral part of the known motif, not its core. Look for a clear, well-aligned core sequence in the detailed view before concluding a match [12] [13].

Troubleshooting Guides for Motif Discovery

Problem: Motif Finding is Taking Too Long or Not Finishing

Long run times are often due to overly ambitious parameters or large dataset sizes.

Solutions:

- Start with default parameters. Resist the urge to find large motifs initially. Begin with

-len 8,10,12[12] [13]. - Reduce sequence set size. Use only your highest confidence target sequences (e.g., top 10,000 peaks). Limit the number of background sequences (e.g.,

-N 20000in HOMER) [12]. - Limit sequence length. Use shorter sequences centered on your regions of interest (e.g.,

-size 50or-size 100instead of the full peak length) [12]. - For long motifs (>16bp): Increase the number of allowed mismatches during the search (e.g.,

-mis 4or-mis 5in HOMER) to maintain sensitivity [12].

Problem: No Significant or Plausible Motifs Are Found

A failure to find motifs can stem from biological reality (no strong, shared motif) or technical issues.

Solutions:

- Verify background sequence selection. The background is critical for calculating enrichment. If you have a specific set of control regions (e.g., expressed genes, cell-type-specific peaks), provide them directly using the

-bgoption. Disable automatic GC-weighting with-noweightif your background is already matched [12] [13]. - Check for sequence bias. If your results are dominated by low-complexity motifs, use autonormalization (

-olen) or switch GC-normalization methods (-gc) [12]. - Ensure adequate sequence number and quality. Motif finding requires a sufficient number of sequences containing the motif. If the true motif is present in a very small fraction (<5%) of targets, it may be missed or dismissed as a low-quality hit [13].

Problem: Handling and Interpreting Long or Highly Degenerate Motifs

Standard motif finders struggle with long, variable motifs because the search space becomes immense.

Solutions and Advanced Strategies:

- Use a two-step optimization strategy. First, find a short version of the motif (e.g.,

-len 12). Then, rerun the analysis and instruct the tool to optimize this motif to a longer length (e.g., in HOMER:-opt motif1.motif -len 30) [12]. - Employ specialized algorithms. Tools like MotifSeeker are specifically designed to handle high degeneracy by leveraging the property that variable sites are often position-specific, which reduces noise and improves accuracy [11].

- Look for nonrandom clustering. If a single motif is elusive, analyze the distribution of potential low-affinity sites around your high-confidence regions to see if they cluster non-randomly, which can be a signature of functional importance [10].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: Identifying Nonrandom Clusters of Degenerate Sites

Objective: To statistically test if low-affinity, degenerate TFBSs are non-randomly clustered around canonical binding sites.

Methodology:

- Define High-Score and Degenerate Sites: Using a position weight matrix (PWM) for your TF of interest, define two sets of sites:

- High-score sites: Sites with a PWM score above a stringent threshold (e.g., minimizing false positives).

- Highly-degenerate sites: Sites with a PWM score below the high-score threshold but above a relaxed lower bound [10].

- Genomic Coordinate Mapping: Map the genomic coordinates of all high-score and highly-degenerate sites. Mask repetitive regions to avoid false positives [10].

- Calculate Enrichment: In the proximal promoter regions (e.g., -2kb to +2kb from TSS) of known target genes, calculate the observed density of highly-degenerate sites around the high-score sites. Compare this to the density expected by chance, which can be derived using permuted versions of the PWM [10].

- Statistical Testing: Use a Chi-squared test on a 2x2 contingency table to determine if the observed enrichment is statistically significant [10].

The workflow for this analytical protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol: Assessing Evolutionary Conservation of Degenerate Sites

Objective: To determine if degenerate TFBSs are under evolutionary constraint by analyzing their conservation across species.

Methodology:

- Compile Orthologous Promoters: Gather the promoter sequences (e.g., -2kb to +2kb from TSS) for a set of orthologous genes from multiple species (e.g., human, mouse, rat) [10].

- Identify Sites in Each Species: Independently identify the high-score and highly-degenerate sites in the orthologous promoter of each species, using the same PWM and thresholds [10].

- Define Conservation: A site is considered "conserved" if it is found in all orthologous promoters, with similar sequences (allowing for a small number of base differences) and similar locations relative to the TSS (e.g., within 400 bp) [10].

- Calculate Conservation Rate: For the high-score and highly-degenerate sites, calculate the conservation rate (p) as the ratio of conserved occurrences to the average overall occurrences across species.

- Compare to Background: Compare this observed conservation rate (p) to an expected background rate (p₀) derived from random permuted motifs. Use a Chi-squared test to assess if the observed conservation is significantly greater than expected by chance [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Resources for Degenerate Motif Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HOMER | Software Suite | De novo motif discovery & ChIP-seq analysis | Provides practical tips for judging motif quality and handling long/degenerate motifs [12]. |

| MotifSeeker | Algorithm | Identification of highly degenerate motifs | Uses position-restricted degeneracy and data fusion to improve accuracy in long sequences [11]. |

| TRANSFAC | Database | Curated library of TF binding motifs | Source of PWMs (e.g., RE1 matrix M00256) used to define high-score and degenerate sites [10]. |

| MATCH | Algorithm | Genome-wide search for TFBSs using PWMs | Allows adjustment of score thresholds to define site categories [10]. |

| COSMIC | Database | Catalog of somatic mutations in cancer | Used for identifying nonrandom clusters of activating mutations in oncogenes [14]. |

| CoSMoS.c. | Web Tool | Conservation scoring in S. cerevisiae | Calculates multiple conservation scores (e.g., Shannon Entropy, JSD) across 1012 yeast strains [15]. |

Performance Benchmarking and Data Presentation

Benchmarking Motif Discovery Tools

When selecting a tool, consider the nature of your motif. Different algorithms have different strengths, particularly when dealing with degeneracy. The following table synthesizes findings from benchmark studies.

Table 2: Characteristics of Select Motif Finding and Analysis Approaches

| Method / Aspect | Typical Use Case | Advantages | Limitations / Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PWM (HOMER, MEME) | Standard de novo discovery | Interpretable, widely used, fast [16]. | Assumes positional independence; can be noisy [16]. |

| SVM-based Models | Classification of bound/unbound sequences | Can capture interactions beyond PWM scope [16]. | Performance depends on training data; limited to short k-mers [16]. |

| Deep Learning Models | Complex pattern recognition in large datasets | Can model long-range dependencies and complex features [16]. | "Black box" nature; requires large data and compute resources [16]. |

| MotifSeeker | Finding highly degenerate motifs | Accuracy less sensitive to motif degeneracy and input sequence length [11]. | --- |

| Clusterize | Clustering millions of sequences | Linear time complexity; high accuracy [17]. | Designed for sequence clustering, not direct motif discovery. |

The decision-making process for selecting an appropriate tool based on the research goal and data characteristics is outlined below.

A fundamental question in gene regulation is how transcription factors (TFs) achieve functional specificity in vivo when members of the same structural family recognize strikingly similar DNA sequences in vitro. This is known as the specificity paradox [18].

Eukaryotic TFs from the same structural family (e.g., zinc fingers, homeodomains, bZIP, and bHLH) tend to bind very similar DNA sequences, yet they execute distinct, non-overlapping functions within the cell. For instance, family members of the bHLH class control essential processes as different as myocyte differentiation (MyoD), regulation of the circadian clock (Clock and BMAL1), and the decision to proliferate or differentiate (Max), despite recognizing very similar binding sites [18].

The resolution to this paradox lies partly in the use of low-affinity binding sites (also termed suboptimal or highly-degenerate sites), which are better able to distinguish between similar TFs than high-affinity sites. Furthermore, the cell employs combinatorial strategies and exploits an inhomogeneous 3D nuclear distribution of TFs, where locally elevated TF concentration allows these low-affinity binding sites to become functional [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is a "low-affinity" transcription factor binding site (TFBS)? A low-affinity TFBS is a DNA sequence that bears similarity to a TF's consensus binding sequence but has a lower binding energy, typically one or two orders of magnitude lower in affinity than the optimal consensus site [19]. These sites are often highly degenerate, meaning many sequence variations can still facilitate binding, albeit more weakly [10].

Q2: If they bind weakly, how can low-affinity sites be functionally relevant? While individual low-affinity sites bind TFs transiently, clusters of these sites within regulatory sequences (like enhancers) can achieve substantial synergistic occupancy at physiologically-relevant TF concentrations [19]. This is because the presence of multiple adjacent sites increases the local probability of TF binding, leading to a high mean occupancy that can drive transcriptional output comparable to that of high-affinity sites [19].

Q3: Aren't these low-affinity sites just non-functional evolutionary leftovers? No, genomic analyses show that highly-degenerate TFBSs are non-randomly distributed and are significantly enriched around cognate, functional binding sites. Comparisons of orthologous promoters across species reveal that these sites are conserved more than expected by chance, suggesting they are under positive selection and contribute to a favorable genomic landscape for target site selection [10].

Q4: What experimental methods can detect these elusive low-affinity interactions? Detecting low-affinity binding requires sensitive or high-throughput methods. Key techniques include:

- Modified MITOMI (iMITOMI): A microfluidics-based assay that quantitatively measures TF binding across a wide affinity range, ideal for clusters [19].

- HT-SELEX/SELEX-seq: High-throughput methods that use selection and deep sequencing to measure relative binding affinities [18] [20].

- Protein Binding Microarrays (PBMs): Microarrays of immobilized DNA probes used to quantify binding specificity [18] [20].

- Spec-seq/MITOMI: Provide quantitative affinity measurements, including the low-affinity range [18].

Q5: How do low-affinity sites contribute to transcriptional robustness? Clusters of low-affinity sites provide redundancy. A mutation in one site within a cluster has a minimal impact on the overall occupancy and transcriptional output, as the other sites can still recruit the TF. This makes the regulatory system more robust to genetic variation and environmental fluctuation [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Investigating Low-Affinity Binding In Vitro

Challenge: Your in vitro binding data (e.g., from EMSA) shows weak or inconsistent binding for a suspected regulatory sequence, or ChIP-seq fails to show a peak in a region with suspected functional activity.

Diagnosis: The regulatory element may be dependent on a cluster of low-affinity sites, which are difficult to detect with standard assays.

Solution: Employ quantitative, high-throughput in vitro assays to characterize binding to potential site clusters.

Step-by-Step Protocol: Using an iMITOMI-like Approach [19]

- Design DNA Target Library: Synthesize a library of double-stranded DNA sequences (e.g., ~90 bp). Include targets with varying numbers of weak/very-weak binding sites (1 to 6 sites), clusters of overlapping sites, and single consensus sites as controls.

- Immobilize DNA: Configure the microfluidic device to surface-immobilize the DNA target library.

- Introduce Transcription Factor: Flow a solution containing the purified TF at various concentrations (e.g., from low nM to µM) over the immobilized DNA.

- Mechanical Trapping: Once equilibrium is reached, use a "button" valve on the device to mechanically trap TF-DNA complexes, preventing dissociation during washing.

- Quantify Binding: Use fluorescent antibodies against the TF and fluorescent staining of DNA to quantify bound TF and total DNA for each feature. Normalize the bound TF signal by the DNA signal.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot binding saturation curves for each DNA target.

- Calculate the mean occupancy (〈N〉), the average number of TFs bound per DNA molecule.

- Observe if clusters of low-affinity sites achieve occupancy levels similar to single high-affinity sites at relevant TF concentrations.

Table 1: Key Parameters from a Systematic iMITOMI Study [19]

| Transcription Factor | Cluster Configuration | Individual Site Affinity (Relative to Consensus) | TF Concentration for Equivalent Occupancy to Single Consensus Site | Maximum Observed Occupancy (〈N〉) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zif268 (Zinc Finger) | Single Consensus | 1x | (Reference) | ~1 |

| Zif268 (Zinc Finger) | 6x Weak Sites | ~10x lower | 14 nM | ~6 |

| Pho4 (bHLH) | Single Consensus | 1x | (Reference) | ~1 |

| Pho4 (bHLH) | 5x Weak Sites | ~10x lower | 170 nM | ~5 |

Guide: Validating Functional Relevance of Low-Affinity Clusters In Vivo

Challenge: You have identified a cluster of low-affinity sites in silico and confirmed binding in vitro, but you need to prove its functional role in a living cell.

Diagnosis: The cluster's contribution to gene expression needs to be tested in a physiological context.

Solution: Use synthetic biology and native gene replacement strategies in a model organism (e.g., S. cerevisiae).

Step-by-Step Protocol: Synthetic and Native Promoter Testing [19]

A. Synthetic Promoter Construction:

- Design: Clone a minimal promoter (e.g., the yeast minCYC1 promoter) upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP).

- Integrate Binding Sites: Engineer clusters of low-affinity binding sites (e.g., for Zif268) into the promoter. Include controls with single consensus sites and multiple consensus sites.

- Transform & Measure: Introduce the constructs into your host organism and measure the reporter gene expression level (e.g., fluorescence).

B. Native Promoter Replacement:

- Identify a Native System: Choose a well-characterized regulatory network (e.g., the inorganic phosphate regulatory network in yeast, controlled by Pho4).

- Edit the Promoter: In the native promoter of a target gene (e.g., PHO5), replace the existing high-affinity TF binding regions with synthetic clusters of low-affinity sites for the same TF (Pho4).

- Assay Functionality: Under inducing conditions, measure the expression of the native gene or a linked reporter. Compare the output driven by the low-affinity cluster to that of the wild-type promoter.

Expected Outcome: A cluster of 3-5 low-affinity binding sites, each an order of magnitude lower in affinity than the consensus, can generate a transcriptional output comparable to a single or even multiple consensus sites [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Studying Low-Affinity TFBSs

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Transcription Factor | For in vitro binding assays (MITOMI, SELEX, PBM). | Requires functional DNA-binding domain. Aliquot and store at -80°C to avoid denaturation from freeze-thaw cycles [21]. |

| High-Complexity DNA Library | Contains randomized or genomic DNA fragments for SELEX-seq or PBM. | Must be designed to cover the sequence space of interest, including flanking regions which can influence affinity [18] [20]. |

| RNase Inhibitor (e.g., RiboLock RI) | Protects RNA during in vitro transcription for probe synthesis. | Essential for maintaining RNA integrity in any step involving RNA [21]. |

| Microfluidic Device (e.g., MITOMI/iMITOMI) | Allows highly parallel, quantitative measurement of binding equilibria. | The inverted geometry (iMITOMI) with surface-immobilized DNA is optimal for studying clusters [19]. |

| Chromatin Shearing Enzymes (e.g., MNase) | For preparing chromatin fragments for ChIP-seq/DAP-seq. | Defines resolution of in vivo binding maps. Optimization is required for different cell types. |

| Bag-of-Motifs (BOM) Software | Computational framework to predict cell-type-specific enhancers based on motif counts. | A minimalist, interpretable model that can outperform deep-learning approaches for classifying regulatory elements [22]. |

Conceptual and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz, illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this guide.

A comprehensive understanding of the cistrome—the complete set of transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) in a genome—is fundamental to decoding gene regulatory networks. However, accurately identifying TFBS presents significant challenges, as binding is influenced not only by core sequence motifs but also by the broader cistromic and epicistromic environment, which includes tissue-specific DNA chemical modifications like methylation. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers navigating the complexities of TFBS recognition within its genuine genomic context, with a focus on improving motif discovery for degenerate binding sites.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Experimental Design and Execution

Q1: Our in vitro TFBS predictions do not match subsequent in vivo validation results. What could be causing this discrepancy?

- Problem: A common issue is that the DNA used for in vitro binding assays (like SELEX or PBM) lacks the native genomic context, including DNA methylation patterns and primary sequence flanking the core motif, which can significantly impact TF binding affinity.

- Solution: Consider employing methods that utilize native genomic DNA (gDNA) instead of synthetic oligonucleotides. The DAP-seq method, for instance, probes binding sites with in-vitro-expressed TFs against a library of fragmented gDNA. Because this gDNA retains its natural 5-methylcytosine patterns, it allows for the simultaneous mapping of the cistrome and the "epicistrome" — the map of methylation-sensitive binding events [23]. Comparing results from standard DAP-seq with ampDAP-seq (which uses a PCR-amplified library where DNA modifications are removed) can directly reveal the impact of DNA methylation on binding for your TF of interest [23].

Q2: We are working with a transcription factor for which we cannot obtain a binding signal in any in vitro assay. What are potential reasons and solutions?

- Problem: The failure could stem from technical issues in protein expression or fundamental biological requirements of the TF.

- Solution:

- Technical Issues: First, verify protein stability and expression levels in your system. A simple retest may resolve the issue for some TFs [23].

- Biological Requirements: The TF may require a specific protein partner, cofactor, or post-translational modification for DNA binding activity [23]. Research known interactors or required cofactors for your TF's family. Supplementing the binding reaction with suspected cofactors or using a heterodimer partner in the assay might be necessary. Note that success rates are highly family-specific; for example, MADS-box TFs are particularly difficult to recover in vitro, while bZIP and NAC families have higher success rates [23].

Q3: How can we confidently identify the true motif when working with a set of genomic regions from a ChIP-seq experiment?

- Problem: The regions identified by ChIP-seq are often several hundred base pairs long, and the actual TFBS is a short, degenerate motif within this larger sequence, making its discovery challenging [24].

- Solution: Utilize multiple modern de novo motif discovery algorithms that are designed for ChIP-seq data. These tools use sophisticated search strategies to find over-represented, conserved sequence patterns within the input sequences [24]. Be aware that different algorithms have different strengths:

- Combinatorial Optimization (e.g., Weeder): Effective for finding short, exact motifs [25] [26].

- Probabilistic Methods (e.g., MEME, Gibbs Sampling): Build a position weight matrix (PWM) to model the frequency of nucleotides at each position, allowing for degeneracy [24] [26].

- Nature-Inspired Algorithms (e.g., GALF-G): Can be useful for finding multiple, potentially overlapping motifs and for handling uncertainty in the true motif width [25].

- Ensemble Approaches: Using several tools and comparing their results can improve confidence in the final predicted motif [25].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Q4: Our motif discovery tool returns multiple candidate motifs. How do we determine which one is biologically relevant?

- Problem: Computational tools can output several high-scoring motifs, but not all may be functional.

- Solution: Triangulate your findings using multiple lines of evidence:

- Comparison to Known Databases: Use tools like TOMTOM or STAMP to compare your candidate motifs against databases of known motifs (e.g., JASPAR, TRANSFAC) [24] [27].

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Perform Gene Ontology (GO) or pathway enrichment analysis on the genes associated with your binding sites. A biologically relevant motif should be associated with targets that have coherent functions, consistent with the known or suspected role of your TF [23] [27].

- Evolutionary Conservation: Check if the candidate motifs are located in evolutionarily conserved non-coding sequences, which are strong indicators of functional regulatory elements [27].

- Clustering of Sites: Genuine cis-regulatory elements often contain clusters of binding sites for one or multiple TFs [27]. Check if your candidate motifs appear in dense clusters within your ChIP-seq peaks.

Q5: What does it mean for a transcription factor to be "methylation sensitive," and how does this affect our analysis?

- Problem: A large proportion of TFs (over 75% in Arabidopsis) exhibit methylation sensitivity, meaning their binding is enhanced or occluded by the presence of methylated cytosines within their binding motif [23]. Ignoring this can lead to a high false negative rate.

- Solution: Incorporate methylation data into your binding site analysis.

- If using DAP-seq, directly compare binding profiles from methylated (DAP-seq) and non-methylated (ampDAP-seq) gDNA libraries [23].

- If working with ChIP-seq data from a specific tissue, obtain or generate a base-resolution methylome for that same tissue. Overlay your predicted TFBS with the methylation map to identify sites where binding may be blocked by methylation. This set of methylation-affected sites constitutes the "epicistrome" for your TF [23].

Key Experimental Protocols

DNA Affinity Purification Sequencing (DAP-seq)

DAP-seq is a high-throughput method for defining the cistrome and epicistrome of any TF in any organism with a sequenced genome [23].

Detailed Workflow:

- Step 1: Genomic DNA Library Preparation. Isolate and fragment genomic DNA from the tissue of interest. Ligate a sequencing adaptor to the fragments to create the "DAP library." For the ampDAP-seq variant, the gDNA is first PCR-amplified to remove native methylation before adaptor ligation [23].

- Step 2: Transcription Factor Preparation. Express the TF of interest with an affinity tag (e.g., His-tag) in an in vitro translation system. Bind the expressed TF to ligand-coupled beads (e.g., cobalt beads for His-tag) and wash to remove non-specific cellular components [23].

- Step 3: Affinity Purification. Incubate the gDNA library with the immobilized TF. Wash away unbound DNA fragments. Elute the specifically bound DNA [23].

- Step 4: Sequencing and Analysis. Amplify the eluted DNA via PCR, adding an indexed adaptor. Sequence the resulting library and map the reads to a reference genome. Use peak-calling algorithms to identify significantly enriched genomic loci (TFBS) and motif discovery tools to derive the binding motif [23].

Motif Discovery from ChIP-seq Data

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for identifying the binding motif of a TF from ChIP-seq-derived peak regions [24] [25].

Detailed Workflow:

- Step 1: Data Pre-processing. Obtain a set of high-confidence genomic regions (peaks) from your ChIP-seq experiment using a peak-caller. Extract the corresponding DNA sequences from the reference genome.

- Step 2: Sequence Preparation (Optional). To reduce the search space and improve signal-to-noise ratio, you may focus on the most significant peaks or restrict the analysis to sequences immediately surrounding the peak summits.

- Step 3: Algorithm Selection and Execution. Choose one or more motif discovery tools based on your needs (see FAQ #3). Execute the tool(s), typically providing the FASTA file of peak sequences and parameters for motif width and number of motifs to discover.

- Step 4: Post-processing and Validation. Analyze the output motifs for significance (E-value, p-value). Compare them to known databases and validate them using the strategies outlined in FAQ #4.

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from large-scale studies on TF binding and motif discovery, which can serve as benchmarks for your own research.

| Metric | Value / Finding | Context / Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Methylation-Sensitive TFs | >75% (248/327) | Proportion of Arabidopsis TFs whose binding was affected by DNA methylation in their motif [23]. |

| TFBS Genome Coverage | 9.3% (11 Mb) | Portion of the Arabidopsis genome covered by 2.7 million TFBS identified via DAP-seq [23]. |

| DAP-seq vs. ChIP-seq Site Count | ~12,352 (DAP) vs. ~8,372 (ChIP) | Average number of binding sites per TF, showing DAP-seq's comprehensiveness [23]. |

| Informative Positions in PWM | 6.8 bp (DAP-seq) vs. 4.8 bp (PBM) | DAP-seq-derived motifs contained more information-rich positions, leading to more precise TFBS prediction [23]. |

| Population with CVD | ~4.5% of total population | Highlights the importance of colorblind-friendly palettes in data visualization for accessibility [28]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for key experiments in cistrome analysis.

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Affinity-Tagged TF Construct | Enables in vitro expression and immobilization of the TF on beads for purification in DAP-seq [23]. |

| Native Genomic DNA (gDNA) | The substrate for DAP-seq; retains tissue-specific methylation patterns, allowing for epicistrome mapping [23]. |

| PCR-Amplified gDNA Library | Creates a modification-free control library for ampDAP-seq to isolate the effect of DNA methylation on binding [23]. |

| Position Weight Matrix (PWM) | A probabilistic model representing a TF's binding specificity; used to score and predict potential TFBS in silico [24] [27]. |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) | An experimental technique to isolate DNA regions bound by a specific protein in vivo, providing input for motif discovery [24] [27]. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

DAP-seq Experimental Workflow

Impact of DNA Methylation on TF Binding

Motif Discovery from ChIP-seq Data

The Computational Toolbox: Algorithms and Platforms for Motif Discovery

Combinatorial and enumeration approaches are fundamental methods in DNA motif discovery, designed to identify transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) by systematically exploring the space of possible DNA patterns. Unlike probabilistic methods that may converge to local optima, these algorithms exhaustively search for over-represented subsequences in genomic data, making them particularly valuable for finding degenerate motifs where binding specificity may vary [29] [30].

These approaches operate on the principle that functional regulatory elements will occur more frequently in relevant DNA sequences than would be expected by chance alone. By examining all possible or many possible word patterns, they can identify short, conserved motifs that represent potential protein-DNA interaction sites. The field has evolved from simple exact string matching to sophisticated algorithms that accommodate degeneracy using IUPAC codes and specialized data structures to manage the computational complexity [31] [29].

Algorithm Specifications and Workflows

Teiresias Algorithm

Teiresias is a combinatorial pattern discovery algorithm that operates in two distinct phases: scanning and convolution [30]. It efficiently finds rigid patterns without requiring the motif to be present in every input sequence.

- Core Principle: Based on general pattern discovery, Teiresias identifies all maximal patterns with minimum support specified by the user [30].

- Key Feature: A distinctive property of Teiresias is the type of structural restriction it allows users to impose. The algorithm is flexible, requiring only the parameter

Wto be set, which enables the discovery of patterns of arbitrary length as long as preserved positions are not more thanWresidues apart [30]. - Typical Application: In a 2005 study, researchers used Teiresias to scan 23 Hrp59 target exons and successfully identified the known "GGAGG" core motif, which was subsequently validated through ChIP, IP, and RT-PCR experiments [30].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the Teiresias algorithm:

Weeder Algorithm

Weeder is an enumeration-based algorithm particularly designed for finding transcription factor binding sites in eukaryotic organisms [29] [30]. It implements an exhaustive search method to identify conserved motifs.

- Core Principle: Weeder performs exhaustive enumeration to identify signals without requiring the user to input the exact motif length [30].

- Search Method: The algorithm examines all possible motifs up to a specified length, allowing for mismatches, and evaluates their over-representation in the input sequences compared to background models [29].

- Application Context: Weeder belongs to the category of word enumeration algorithms that use IUPAC motif representation, providing discriminative power similar to probabilistic models [31].

MotifSeeker and the LP/DEE Framework

While not explicitly detailed in the search results, MotifSeeker represents approaches that combine combinatorial optimization with mathematical programming. The LP/DEE (Linear Programming/Dead-End Elimination) framework recasts motif discovery as finding the best gapless local multiple sequence alignment using the sum-of-pairs (SP) scoring scheme [32].

- Core Principle: Models motif discovery as finding a maximum weight clique in a multi-partite graph, then applies integer linear programming and pruning techniques [32].

- Key Innovation: Uses Dead-End Elimination (DEE) algorithms to discard sequence positions incompatible with the optimal alignment, dramatically reducing problem size before applying mathematical programming solutions [32].

- Advantage: This approach naturally incorporates substitution matrices and phylogenetic information, making it suitable for both DNA and protein motif discovery [32].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My motif discovery tool runs extremely slowly or runs out of memory with large sequence sets. What optimizations can I try?

- Sequence Length Reduction: Research has shown that sequence length is the most critical factor affecting performance. Reduce upstream sequences to 100-400bp regions rather than using full intergenic regions [33].

- Tool Selection: Consider using algorithms like Weeder or DiNAMO that implement efficient data structures for enumeration. For very large datasets, probabilistic methods like MEME may be more practical despite potential sensitivity trade-offs [31] [29].

- Parameter Adjustment: Limit motif length and degeneracy parameters. In DiNAMO, restricting the number of degenerate letters (

d) significantly reduces computational complexity [31].

Q2: How can I distinguish biologically relevant motifs from false positives?

- Control Datasets: Always run motif discovery with appropriate control sequences (e.g., random genomic regions or sequences from unrelated experiments). DiNAMO specifically implements this approach by requiring both signal and control datasets [31].

- Statistical Validation: Use multiple significance measures. The LP/DEE framework incorporates statistical significance testing using background nucleotide frequencies to compute the probability of observed motif scores occurring by chance [32].

- Cross-Platform Validation: Recent research shows that motifs consistent across multiple experimental platforms (ChIP-seq, SELEX, PBM) are more likely to be biologically relevant [8].

Q3: Why do different motif discovery algorithms return different results for my dataset?

- Algorithmic Diversity: Different algorithms optimize different objective functions - combinatorial methods often use mutual information or Fisher's exact test, while probabilistic methods maximize likelihood functions [31] [29].

- Solution: Implement ensemble approaches. Research shows that combining predictions from multiple algorithms can improve accuracy by 6-45% over individual base algorithms [33].

- Tool-Specific Patterns: Weeder excels with eukaryotic TFBS discovery, while Teiresias is effective for finding patterns with specific spatial constraints [30].

Q4: How should I handle degenerate motifs with variable binding specificity?

- IUPAC Representation: Use tools like DiNAMO that explicitly model degeneracy using IUPAC codes, allowing a controlled level of ambiguity at specific positions [31].

- Sum-of-Pairs Scoring: Consider methods like the LP/DEE framework that use SP-scoring which can naturally accommodate dependencies between nucleotide positions, unlike position-independent models [32].

- Multiple Modes: For transcription factors with multiple binding modes, recent research suggests combining multiple PWMs into random forest models can better capture binding diversity [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance comparison of combinatorial motif discovery approaches

| Algorithm | Optimality Guarantee | Strengths | Limitations | Typical Runtime Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teiresias | Finds all maximal patterns with specified support [30] | Flexible pattern length; doesn't require motif in every sequence [30] | May produce large output sets requiring filtering | Quasi-linear with output size [30] |

| Weeder | Exhaustive for specified length and mismatches [29] | Effective for eukaryotic TFBS discovery [29] [30] | Limited to shorter motifs due to combinatorial explosion [29] | Exponential with motif length [29] |

| LP/DEE Framework | Provably optimal for many practical instances [32] | Handles long motifs; incorporates phylogenetic information [32] | Complex implementation; requires mathematical programming solvers [32] | Polynomial for many practical cases [32] |

Comprehensive Workflow for Degenerate TFBS Discovery

The following workflow integrates multiple combinatorial approaches for robust identification of degenerate transcription factor binding sites:

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Sequence Acquisition and Pre-processing

- Obtain upstream sequences (200-500bp) for co-regulated genes from databases like RegulonDB or ENSEMBL.

- Mask low-complexity regions and repetitive elements using tools like RepeatMasker.

- Generate control sequences with similar length and GC content for statistical comparison.

Multi-Algorithm Motif Discovery

- Run Weeder with default parameters for exhaustive enumeration of IUPAC motifs.

- Execute Teiresias with parameter W set based on expected spacing between conserved positions.

- For complex or long motifs, implement the LP/DEE framework using sum-of-pairs scoring.

Ensemble Analysis and Validation

- Identify motifs consistently predicted across multiple algorithms.

- Calculate statistical significance using Fisher's exact test or mutual information.

- Verify motifs against known databases (JASPAR, CIS-BP) and experimental data when available.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential resources for combinatorial motif discovery research

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Purpose/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motif Discovery Software | Weeder [29] [30], Teiresias [30], DiNAMO [31] | Identifying over-represented DNA patterns | Exhaustive enumeration; IUPAC output; control dataset support |

| Benchmarking Platforms | Codebook Motif Explorer (MEX) [8], Tompa et al. benchmark [33] | Algorithm performance evaluation | Cross-platform validation; large-scale comparison |

| Sequence Databases | RegulonDB [33], JASPAR [8], CIS-BP [8] | Experimental sequence sources and validation | Experimentally verified binding sites; curated motifs |

| Statistical Frameworks | Mutual Information [31], Fisher's exact test [31], Sum-of-Pairs scoring [32] | Significance assessment of discovered motifs | Multiple testing correction; background modeling |

Transcription Factor Binding Sites (TFBSs) are short, recurring DNA sequences that play a fundamental role in gene regulation. These sequences are recognized by transcription factors (TFs), proteins that control the expression of genetic information. In vertebrate genomes, TFBSs are typically highly degenerate, meaning numerous sequence variations can facilitate binding with varying affinities [10]. This degeneracy creates a landscape filled with highly-degenerate TFBS-like sequences distributed non-randomly throughout the genome, presenting significant challenges for accurate computational identification [10].

This technical support center addresses these challenges by providing targeted troubleshooting and methodological guidance for three powerful motif discovery tools: MEME, HOMER, and GimmeMotifs. Each employs distinct computational approaches—including probabilistic modeling, enumerative methods, and ensemble techniques—to identify these elusive regulatory elements within genomic sequences. By optimizing the use of these tools, researchers can advance our understanding of gene regulatory networks, with important implications for deciphering developmental biology and disease mechanisms.

Tool-Specific Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

MEME Suite Troubleshooting

Q: What should I do when MEME runs excessively slowly on large datasets?

A: MEME's running time increases roughly with the square of the sequence data size. Use the -searchsize option to limit the portion of primary sequences (in letters) used in the motif search. For very large datasets, setting -searchsize 0 uses all sequences but will significantly increase runtime [34].

Q: How do I select the appropriate objective function for ChIP-seq data?

A: MEME offers several objective functions. For ChIP-seq data where motifs are centrally enriched, use -objfun ce (Central Enrichment) or -objfun cd (Central Distance). These functions are specifically designed for such data and require all input sequences to be of equal length with adequate flanking regions (e.g., 500bp) [34].

Q: Why are my results different when using control sequences versus shuffled sequences?

A: When control sequences (-neg option) are not provided, MEME generates them by shuffling primary sequences while preserving k-mer frequencies (default k=2). Using actual control sequences from your experiment typically provides more biologically meaningful results than shuffled sequences [34].

Table: MEME Objective Functions for Different Data Types

| Objective Function | Command Option | Best For | Key Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classic | -objfun classic |

General purpose motif discovery | Standard motif enrichment |

| Central Enrichment | -objfun ce |

ChIP-seq, CLIP-seq | Equal-length sequences, central motif tendency |

| Central Distance | -objfun cd |

ChIP-seq, CLIP-seq | Equal-length sequences, distance-based scoring |

| Differential Enrichment | -objfun de |

Datasets with control sequences | Primary and control sequences |

HOMER Troubleshooting

Q: How can I improve HOMER's sensitivity for finding long motifs (>16 bp)?

A: HOMER's empirical approach struggles with longer motifs due to sparse sequence space. To improve sensitivity: (1) Increase mismatches with -mis 4 or -mis 5; (2) First find short motifs, then optimize to longer lengths using -opt motif1.motif -len 30; (3) Reduce sequence complexity with -size 50 and limit background sequences with -N 20000 [12].

Q: Why does HOMER report different numbers of background sequences than I input? A: HOMER automatically normalizes GC-content between target and background sequences. If your target sequences are GC-rich and background is AT-rich, many AT-rich sequences may be added fractionally to minimize imbalance, changing the apparent count [12].

Q: How can I address simple repeat motifs or low-complexity false positives?

A: Systematic biases between target and background often cause these issues. For GC-bias, use -gc for total GC-content normalization instead of default CpG-content. For other compositional biases, use -olen # for aggressive oligo-level autonormalization, or carefully design matched background sequences [12].

Diagram: HOMER's Differential Motif Discovery Workflow. The algorithm compares target and background sequences while normalizing for sequence composition biases [5] [12].

GimmeMotifs Troubleshooting

Q: How can I reduce GimmeMotifs' running time for large datasets?

A: Running time depends on input size, tools used, and motif sizes. For large ChIP-seq datasets: (1) Use default settings (absolute maximum of 1000 sequences for prediction); (2) Analyze only top 5000 peaks; (3) Avoid slow tools like GADEM; (4) Use smaller motif sizes (-a medium or -a large instead of -a xl) [35].

Q: What background type should I choose for my analysis?

A: GimmeMotifs offers several background options: gc (default, matches GC%), genomic (random genomic regions), random (artificial sequences with similar composition), promoter (random promoters), or a custom file. The default gc background is generally recommended for most applications [35].

Q: Why are my positional preference plots incorrect?

A: This occurs when input sequences have different lengths. For proper statistics and plotting, ensure all sequences in your FASTA file are the same length. GimmeMotifs automatically handles this when using BED/narrowPeak files with the -s (size) parameter [35].

Table: Recommended De Novo Tools in GimmeMotifs

| Tool | Best For | Speed | Sensitivity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEME | General purpose, long motifs | Medium | High | Default choice |

| Homer | ChIP-seq data, short motifs | Fast | Medium | Specialized for genomic data |

| BioProspector | ChIP-seq data | Medium | Medium | Complementary approach |

| DREME | Short motifs (<8 bp) | Very Fast | High for short motifs | Good for initial scan |

Experimental Protocols for Degenerate TFBS Research

Comprehensive Motif Discovery Pipeline for Degenerate Sites

Protocol Objective: Identify both primary and highly degenerate transcription factor binding sites from ChIP-seq data using a multi-tool approach that maximizes sensitivity to sequence degeneracy.

Step 1: Sequence Preparation and Quality Control

- Obtain peak regions from ChIP-seq analysis (e.g., MACS2 narrowPeak files)

- Extract sequences centered on peak summits (200-500bp recommended)

- For HOMER: Use

findMotifsGenome.plwith genome reference - For MEME: Convert to FASTA format with equal-length sequences

- For GimmeMotifs: Can directly use BED, narrowPeak, or FASTA files

Step 2: Background Sequence Selection

- Critical Consideration: Proper background is essential for degenerate TFBS identification

- GC-matched background: Default in HOMER and GimmeMotifs; controls for compositional bias

- Cell-type specific background: Use promoters or accessible regions from same cell type

- Empirical background: For differential analysis, use non-specific peaks as background

Step 3: Multi-Tool Motif Discovery Execution

- HOMER: Run with increasing motif lengths (

-len 8,10,12,15,20) and increased mismatch allowance (-mis 4) for degenerate sites - MEME: Use

-objfun dewith control sequences for differential enrichment analysis - GimmeMotifs: Employ ensemble approach with multiple de novo tools (

-t meme,homer,bioprospector)

Step 4: Validation and Specificity Assessment

- Cross-reference discovered motifs with known databases (JASPAR, CIS-BP)

- Validate degenerate sites through conservation analysis across species

- Test motif specificity using gimme roc or similar ROC analysis tools

Diagram: Experimental Protocol for Degenerate TFBS Identification. The multi-tool approach increases sensitivity for detecting highly degenerate binding sites [10] [12] [35].

Benchmarking and Validation Methodology

Objective: Quantitatively evaluate motif discovery performance to select optimal tools and parameters for degenerate TFBS identification.

Performance Metrics:

- ROC AUC (Area Under Curve): Measures overall classification performance [36]

- Recall at 10% FDR: Practical metric for biological applications [36]

- Motif Conservation: Assess evolutionary constraint on discovered sites [10]

Validation Procedure:

- Reference Dataset Curation: Collect validated TFBS from databases like ReMap

- Background Sequence Generation: Use matched genomic regions as negatives

- Tool Performance Comparison: Execute multiple tools with standardized parameters

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate performance metrics using tools like

gimme roc

Table: Key Computational Resources for Motif Discovery

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Degenerate TFBS Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEME Suite [37] | Software Package | De novo motif discovery, enrichment analysis | Comprehensive motif analysis using probabilistic models |

| HOMER [5] | Software Package | Differential motif discovery | Finding motifs enriched in target vs. background sequences |

| GimmeMotifs [38] | Analysis Framework | Ensemble motif discovery, benchmarking | Combining multiple tools for improved motif identification |

| JASPAR [36] | Motif Database | Curated TF binding profiles | Reference for known motifs, validation of discoveries |

| CIS-BP [36] | Motif Database | Integrated motif collection | Comprehensive motif reference across multiple species |

| TRANSFAC [10] | Motif Database | Commercial curated motifs | Reference database with quality-controlled profiles |

| GenomePy | Utility Tool | Genome sequence management | Fetching genome sequences for background generation |

Advanced Configuration for Specialized Applications

Handling Specific Data Types

For ATAC-seq Data:

- Use

-size 100or smaller in HOMER to account for smaller accessible regions - Employ GimmeMotifs with promoter background to identify regulatory motifs

- In MEME, use

-objfun cewith centered peaks

For Cross-Species Conservation Analysis:

- Extract orthologous promoter regions from multiple species

- Use conservation as additional filter for degenerate site validation

- Consider specialized tools like PhyloGibbs that incorporate evolutionary information

For Identifying Trans-Acting DNA Motif Groups:

- Use specialized algorithms like MotifHub that employ probabilistic modeling with EM and Gibbs sampling [39]

- Analyze chromatin interaction data (Hi-C) to identify co-binding patterns

- Implement group-specific discovery for promoter-enhancer pairs

Parameter Optimization Tables

Table: Recommended Parameters for Degenerate TFBS Discovery

| Tool | Key Parameter | Standard Value | Degenerate Site Value | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMER | -mis (mismatches) |

2 | 4-5 | Increased sensitivity for variant sites |

| HOMER | -len (motif length) |

8,10,12 | 8,10,12,15,20 | Capture full extent of degenerate motifs |

| MEME | -objfun |

classic | de, ce | Better for differential/enriched motifs |

| GimmeMotifs | -a (analysis size) |

xl | xl | Maximum sensitivity for longer motifs |

| All Tools | Background | random | matched GC% | Reduces false positives from bias |

CompleteMOTIFs (cMOTIFs) is an integrated web tool specifically developed to facilitate systematic discovery of overrepresented transcription factor binding motifs from high-throughput chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments [40] [41]. This platform provides comprehensive annotations and Boolean logic operations on multiple peak locations, enabling researchers to focus on genomic regions of interest for de novo motif discovery using established tools such as MEME, Weeder, and ChIPMunk [40]. The pipeline incorporates a scanning tool for known motifs from TRANSFAC and JASPAR databases and performs enrichment testing using local or precalculated background models that significantly improve motif scanning results [41]. The platform has demonstrated utility in identifying cooperative binding of multiple transcription factors upstream of important stem cell differentiation regulators [40].

Availability: http://cmotifs.tchlab.org [40] [41]

Galaxy ChIP-Seq Analysis Platform

Galaxy provides a comprehensive, user-friendly framework for analyzing ChIP-seq data through accessible web-based tools [42]. The platform enables complete processing of ChIP-seq datasets from raw sequencing reads to advanced interpretation, including: pre-processing sequencing reads, mapping reads to reference genomes, post-processing mapped data, assessing quality and strength of ChIP-signal, displaying coverage plots in genome browsers, calling ChIP peaks with MACS2, inspecting obtained calls, searching for sequence motifs within called peaks, and analyzing distribution of enriched regions across genes [42]. This integrated approach simplifies the computational challenges of ChIP-seq analysis while providing robust, reproducible workflows suitable for researchers without extensive bioinformatics expertise.

Integrated Workflow for Degenerate TFBS Research

Workflow Diagram

Workflow Description

The integrated workflow begins with raw ChIP-seq data preprocessing in Galaxy, including quality control and mapping reads to a reference genome using tools like BWA [42]. Following mapping, post-processing steps filter out poorly mapped reads (e.g., mapping quality <20) to eliminate non-uniquely mapped reads [42]. Peak calling with MACS2 identifies statistically significant enrichment regions [42]. These peak locations then feed into cMOTIFs for sophisticated motif discovery, where Boolean logic operations enable researchers to focus on specific genomic regions of interest [40]. The degenerate TFBS analysis phase leverages cMOTIFs' ability to scan for known motifs from TRANSFAC and JASPAR databases while performing enrichment tests using optimized background models [41]. Finally, experimental validation confirms computational predictions, completing the iterative research cycle.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting Common ChIP-Seq Experimental Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal | Excessive sonication [43], insufficient starting material [43], over-crosslinking [43] | Optimize sonication to yield fragments between 200-1000 bp [43]; Use 25 mg tissue or 4×10⁶ cells per IP [44]; Reduce formaldehyde fixation time [43] |

| High Background | Non-specific antibody binding [43], contaminated buffers [43], low-quality protein A/G beads [43] | Pre-clear lysate with protein A/G beads [43]; Use fresh lysis and wash buffers [43]; Use high-quality protein A/G beads [43] |

| Poor Chromatin Fragmentation | Incorrect micrococcal nuclease concentration [44], suboptimal sonication conditions [44] | Perform MNase titration (0-10 μL diluted enzyme) [44]; Conduct sonication time course [44]; Ensure 150-900 bp fragment size [44] |

| Low DNA Concentration | Insufficient starting material [44], incomplete cell lysis [44] | Increase input material [44]; Verify complete nuclei lysis microscopically [44]; Use 5-10 μg chromatin per IP [44] |

Computational Analysis FAQs

Q: How can I assess the quality of my ChIP-seq data in Galaxy?

A: Galaxy provides multiple quality assessment tools. Use DeepTools plotFingerprint to generate Signal Extraction Scaling (SES) plots, which show the cumulative distribution of read coverage across the genome [42]. Successful ChIP experiments typically show that ~30% of reads are contained in a small percentage of the genome, indicating strong enrichment [42]. Additionally, use multiBamSummary and plotCorrelation to check replicate concordance through correlation heatmaps [42].

Q: What strategies does cMOTIFs offer for analyzing degenerate transcription factor binding sites? A: cMOTIFs enables systematic discovery of overrepresented motifs through comprehensive annotation capabilities and Boolean logic operations on peak sets, allowing researchers to focus on specific genomic regions of interest [40]. The platform performs enrichment testing using optimized background models that improve detection of statistically significant motifs, including highly degenerate sites that may be missed with standard approaches [41].

Q: How can I visualize my ChIP-seq results alongside motif locations?

A: In Galaxy, use bamCoverage to convert BAM files to bigWig format with appropriate bin sizes (e.g., 25 bp) and read extension to fragment size (e.g., 150 bp) [42]. Visualize these tracks in genome browsers like IGV alongside BED files of motif locations identified by cMOTIFs to correlate enrichment peaks with predicted binding sites [42].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Chromatin Fragmentation Optimization

Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) Titration Protocol [44]:

- Prepare cross-linked nuclei from 125 mg tissue or 2×10⁷ cells (equivalent to 5 IP preparations)

- Transfer 100 μL nuclei preparation into 5 individual tubes on ice

- Prepare diluted MNase (3 μL stock + 27 μL 1X Buffer B + DTT)

- Add 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, or 10 μL diluted MNase to tubes, mix, and incubate 20 minutes at 37°C with frequent mixing

- Stop digestion with 10 μL 0.5 M EDTA, pellet nuclei

- Resuspend in 200 μL 1X ChIP buffer + PIC, lyse nuclei by sonication or homogenization

- Reverse cross-links and analyze DNA fragment size on 1% agarose gel

- Select condition producing 150-900 bp fragments; the optimal volume of diluted MNase from this protocol is equivalent to 10× the stock MNase volume for one IP preparation

Sonication Optimization Protocol [44]:

- Prepare cross-linked nuclei from 100-150 mg tissue or 1-2×10⁷ cells

- Perform sonication time course, removing 50 μL samples after increasing duration

- Clarify samples by centrifugation

- Reverse cross-links and analyze DNA fragment size by electrophoresis

- Choose conditions where ~90% of DNA fragments are <1 kb for cells fixed 10 minutes, or ~60% for tissues fixed 10 minutes

- Avoid over-sonication (>80% fragments <500 bp) to prevent chromatin damage and reduced IP efficiency

Quality Control Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for ChIP-Seq Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Micrococcal Nuclease | Chromatin digestion to 150-900 bp fragments | Requires titration for each tissue/cell type [44] |

| Protein A/G Beads | Antibody-mediated chromatin capture | Use high-quality beads to reduce background [43] |

| Formaldehyde | Protein-DNA crosslinking | Limit fixation to 10-30 minutes to prevent epitope masking [43] |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (PIC) | Preserve protein integrity during processing | Use fresh in all buffers [44] |

| Glycine | Quench formaldehyde crosslinking | Critical for stopping fixation [43] |

| Antibody | Target-specific immunoprecipitation | Use 1-10 μg per IP; validate for ChIP applications [43] |

Theoretical Framework: Degenerate TFBS Biology

Genomic Organization of Degenerate Binding Sites

Research on transcription factor binding sites has revealed that highly-degenerate TFBS-like sequences show nonrandom distribution around cognate binding sites [10]. Rather than being randomly distributed throughout the genome, these inexact sites are significantly enriched around functional binding sites, creating a favorable genomic landscape for target site selection [10]. Comparative analyses of human, mouse, and rat orthologous promoters reveal that these highly-degenerate sites are conserved significantly more than expected by chance, suggesting their positive selection during evolution [10]. This arrangement of sub-optimal binding sites around primary sites may facilitate robust transcriptional responses and provide a mechanism for maintaining regulatory specificity despite binding site degeneracy.

Analytical Implications for Motif Discovery

The non-random clustering of degenerate TFBS has important implications for motif discovery in ChIP-seq data. Traditional approaches that focus only on highest-affinity sites may miss this broader regulatory context. The integrated cMOTIFs-Galaxy workflow addresses this by enabling analysis of both high-affinity and degenerate sites through its comprehensive annotation system and Boolean selection capabilities [40]. This approach aligns with findings that functional specificity emerges from the genomic context around target sites, including the arrangement of sub-optimal binding sites that collectively contribute to robust transcriptional regulation [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: I have obtained a set of ChIP-seq peaks. What is the most effective way to build a high-quality Position Weight Matrix (PWM) for my transcription factor of interest?

A: For generating a PWM from your ChIP-seq data, we recommend using the rGADEM tool for de novo motif discovery, as it has been shown to be a top-performing tool for this specific task [45]. The general workflow is as follows:

- Input Preparation: Use your ChIP-seq peak regions (typically in BED format).

- Motif Discovery: Run rGADEM on these sequences. rGADEM is an efficient tool that uses a genetic algorithm to identify over-represented motifs within large sets of genomic sequences [45].

- Model Extraction: The output will be one or more candidate PWMs.

- Validation: Always compare the discovered motif against known models in curated databases like JASPAR or HOCOMOCO for validation and annotation.

Q2: When scanning a DNA sequence with a PWM, how do I choose the correct score threshold to distinguish real binding sites from background?

A: Selecting an appropriate threshold is critical for balancing sensitivity and specificity [46].

- Use a Common False-Positive Rate: A robust and unbiased method is to select a threshold based on a consistent false-positive rate (FPR). Studies have shown that using a common FPR (e.g., 0.001) for all motifs provides results that are least biased by the motif's information content, leading to more uniformly accurate predictions across different TFs [46].

- Database-Specific Thresholds: Some databases, like HOCOMOCO, provide predefined score thresholds corresponding to a specific probability of finding a TFBS among all possible words of a given length, which allows for statistically comparable predictions [47].

- Avoid Inconsistent Thresholds: Do not use arbitrary or fixed log-odds scores for all motifs, as the distribution of scores is highly dependent on the information content of the PWM [46].

Q3: What are the key practical differences between JASPAR, HOCOMOCO, and TRANSFAC that I should consider for my research?

A: The choice of database can significantly impact your results. The table below summarizes the key differences:

Table: Comparison of Major TFBS Model Databases

| Feature | JASPAR CORE | HOCOMOCO | TRANSFAC |

|---|---|---|---|

| License & Cost | Open-access, no restrictions [48] | Open-access, no restrictions [47] | Commercial license required [46] |

| Core Philosophy | Single, non-redundant, high-quality model per TF [48] | Single, hand-curated model per TF by integrating multiple data sources [47] | May contain several models per TF from separate experiments [47] |

| Data Curation | Manually curated with orthogonal experimental support [48] | Systematically curated and hand-curated models [47] | Derived from experimental literature [45] |

| Model Count (Human TFs) | Not specified in results | 426 models for 401 TFs [47] | 106 motifs (2010.3 version) [46] |

Q4: For genome-wide scanning, should I use a tool that predicts individual TFBSs or clusters of sites?

A: The best tool depends on your biological question and the regulatory context you are studying.

- For Individual Sites: Use FIMO (Find Individual Motif Occurrences). It is designed to identify individual TFBSs and was evaluated as a top-performing tool in its class [45].

- For Site Clusters: Use MCAST. It is designed to identify clusters of TFBSs, which are often indicative of cis-regulatory modules, and has been shown to perform best for this purpose [45].

Q5: The motif for my TF of interest looks different in JASPAR and HOCOMOCO. Which one should I trust?

A: Discrepancies arise from the different data sources and construction methodologies.

- JASPAR models are often derived from a single high-throughput experiment (like ChIP-seq) that has been manually curated and supported by orthogonal evidence [48].

- HOCOMOCO explicitly integrates binding sequences from both low- and high-throughput methods to create a unified model, aiming to correct for technique-specific bias and improve robustness [47].

- Solution: Cross-reference your results. Scan your sequences with both models and compare the predictions. You can also check if the motifs are similar to those of related TFs in the same protein family. The HOCOMOCO approach of data integration may often yield a more generalized model [47].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Poor Overlap Between Predicted TFBSs and ChIP-seq Peaks Issue: After running a PWM scan (e.g., with FIMO) on your ChIP-seq peak regions, you find very few overlapping sites, suggesting low sensitivity. Solution:

- Verify PWM Quality: Ensure the PWM used is appropriate for your TF and cell type. Check if a newer or more specific model exists in HOCOMOCO or JASPAR.

- Adjust Score Threshold: The score threshold may be too stringent. Lower the threshold based on a less strict false-positive rate (e.g., from 0.0001 to 0.001) and evaluate the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity [46].

- Check for Motif Variants: Some TFs, like CTCF, have significantly different binding motifs (variants). Ensure you are using the correct variant for your experimental context. JASPAR, for instance, provides multiple profiles for such TFs [48].

- Consider Clustered Sites: If searching for individual sites fails, use a cluster-based scanner like MCAST, as functional binding can sometimes require the presence of multiple sites in close proximity [45].

Problem: Over-prediction of TFBSs and High False-Positive Rate Issue: Your PWM scan predicts an unmanageably large number of sites across the genome, most of which are likely non-functional. Solution:

- Use a Stricter Threshold: Increase the score threshold. Employ a threshold that corresponds to a very low false-positive rate (e.g., 0.0001) [46].

- Incorporate Chromatin Context: Do not rely on sequence-based prediction alone. Integrate additional data such as ATAC-seq or DNase-seq to restrict your scanning to open chromatin regions where TFs can actually bind.