Beyond the Colony: A Modern Comparison of Heterotrophic Plate Count Methods for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Heterotrophic Plate Count (HPC) methodologies, from traditional culture-based techniques to modern rapid alternatives like flow cytometry and qPCR.

Beyond the Colony: A Modern Comparison of Heterotrophic Plate Count Methods for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Heterotrophic Plate Count (HPC) methodologies, from traditional culture-based techniques to modern rapid alternatives like flow cytometry and qPCR. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, practical applications, and limitations of each method. The scope extends to troubleshooting common issues, optimizing protocols for specific sample types, and validating method performance through comparative data. The discussion synthesizes how the choice of HPC method impacts data reliability in critical areas, including pharmaceutical water systems, clinical dialysate quality control, and biocompatibility testing, while forecasting the industry's shift toward rapid, culture-independent diagnostics.

Heterotrophic Plate Count Fundamentals: Understanding the Bedrock of Microbial Water Quality

The Heterotrophic Plate Count (HPC) method represents a foundational microbiological technique for estimating viable bacterial populations in water and other samples. This review objectively compares the performance of different HPC methodologies, with a specific focus on the influential variables of culture media and incubation conditions. Experimental data from clinical water sampling demonstrates that low-nutrient R2A agar incubated at lower temperatures for extended periods yields significantly higher heterotrophic bacterial counts compared to conventional high-nutrient Plate Count Agar (PCA). These performance differences underscore the critical importance of methodological standardization in environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical testing, and public health microbiology to ensure accurate risk assessment.

In microbiology, the Colony-Forming Unit (CFU) serves as the fundamental parameter for estimating the number of viable microorganisms—bacteria or fungi—in a sample that retain the capacity to multiply under controlled conditions [1]. The term "viable" specifically refers to cells that remain physiologically active enough to undergo binary fission and form visible colonies on solid culture media. The CFU measurement differs fundamentally from total cell counts (such as those obtained microscopically or via flow cytometry) because it deliberately excludes non-viable cells that cannot reproduce [2]. This distinction makes HPC particularly valuable for assessing potential infection risks and microbial contamination levels where proliferating organisms pose the primary concern.

The term Heterotrophic Plate Count (HPC) describes the application of CFU methodology to enumerate aerobic and facultative anaerobic heterotrophic bacteria—organisms that require organic carbon for growth [3]. The HPC method involves plating diluted samples onto a solid growth medium containing essential nutrients. After an appropriate incubation period under specified temperature conditions, visible colonies are counted, and the results are calculated back to the original sample concentration, typically expressed as CFU per milliliter (CFU/mL) or CFU per gram (CFU/g) [4] [3]. The theoretical foundation assumes that one viable cell can give rise to one colony through replication. However, this assumption presents limitations because microorganisms in natural environments rarely exist as solitary cells; more often, they form clusters, chains, or clumps (e.g., Streptococcus chains or Staphylococcus clusters). Consequently, a single CFU may originate from a group of cells deposited together, meaning CFU-based quantification typically underestimates the actual number of viable individual cells present [1].

What CFUs Actually Measure: Technical Specifics and Limitations

The Relationship Between Viable Cells and Visible Colonies

The colony-forming unit represents a operational measure of viable colonogenic cell numbers—specifically, those cells that remain viable enough to proliferate and form small colonies under the specific culture conditions provided [5]. The multistep process from single cell to countable colony introduces several technical considerations. The "unit" aspect of CFU acknowledges the uncertainty about whether a visible colony arose from a single cell, a pair, a small cluster, or even a fragment of mycelium in the case of fungi. This inherent uncertainty is precisely why results are expressed as "colony-forming units" rather than direct cell counts [1].

The quantification process typically requires serial dilutions of samples, as original samples often contain too many microorganisms to count individually. The colonies that develop on the plate are enumerated, and the CFU concentration in the original sample is calculated based on the plated volume and dilution factor [1]. For example, if 100 microliters of a 1:1,000 dilution yields 50 colonies, the original concentration calculates to 50 × (1,000/0.1) = 500,000 CFU/mL. This calculation method standardizes reporting despite variations in plating techniques.

Critical Methodological Limitations

Several important limitations affect the accuracy and interpretation of CFU measurements:

- Selective Viability: Only microorganisms capable of growing on the specific medium provided, under the specific temperature and atmospheric conditions provided, and within the specified time frame will form countable colonies. This inherently selects for a subpopulation of the total viable community [1].

- Microbial Aggregation: As noted, bacteria existing in chains or clumps will produce a single CFU regardless of the number of individual cells in that aggregate. Some protocols attempt to disrupt these aggregates through vortexing, but this risks damaging delicate species, potentially reducing viability counts [1].

- Nutrient and Condition Dependence: The chosen growth medium's nutrient composition (high versus low nutrient), incubation temperature, and incubation duration dramatically impact which bacterial species can grow and thus be counted [6].

- Practical Counting Range: For statistical reliability, plates should contain between 30-300 colonies. Fewer colonies reduces statistical power, while crowded plates make accurate counting difficult due to overlapping colonies or resource competition [1].

Experimental Comparison: R2A versus PCA Culture Media

Study Design and Methodological Protocols

A rigorous 2024 study directly compared two primary HPC methodologies for monitoring microbial contamination in hospital purified water systems, specifically targeting water from dental unit three-in-one guns and terminal rinse water for endoscopes [6]. The experimental design addressed a key research question: whether low-nutrient R2A agar or conventional high-nutrient Plate Count Agar (PCA) provides superior recovery of heterotrophic bacteria from purified water systems.

The sample collection protocol followed aseptic techniques. For dental water, sterile tubes collected 10 mL of water discharged after a 30-second flush from three-purpose guns on dental chairs. For endoscopic rinse water, 200 mL samples were collected in sterile bottles after a similar 30-second flush. All samples were stored refrigerated and processed within 2 hours of collection [6]. The analytical methodology employed two approaches based on sample type. For dental water (1 mL samples), the pour plate method was used with both PCA and R2A media, plating tenfold and hundredfold dilutions with parallel samples for each concentration. For endoscopic rinse water (20 mL and 100 mL samples), membrane filtration with 0.45 μm filters was employed, placing the filter membranes directly on the respective agar media [6].

The culture conditions constituted the key experimental variable. PCA medium plates were incubated at 36°C ± 1°C for 48 hours, reflecting standard microbiological practices. In contrast, R2A medium plates were incubated at lower temperatures of 17°C–23°C for 168 hours (7 days), following international recommendations for water testing [6]. This difference in incubation conditions reflects the fundamental ecological adaptation of aquatic bacteria, which typically thrive in cooler, nutrient-poor environments rather than the warm, nutrient-rich conditions mimicking the human body.

Comparative Results and Statistical Analysis

The experimental results demonstrated striking differences between the two methodologies. Analysis of 142 water specimens revealed that the R2A culture method yielded a median heterotrophic bacterial count of 200 CFU/mL (interquartile range: 25–18,000), significantly higher than the median count of 6 CFU/mL (interquartile range: 0–3,700) obtained with the PCA method [6]. Statistical analysis using the Wilcoxon signed-rank sum test confirmed this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05) [6].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of R2A vs. PCA Media for HPC in Hospital Purified Water

| Parameter | R2A Medium | PCA Medium | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median CFU/mL | 200 | 6 | P < 0.05 |

| Interquartile Range (CFU/mL) | 25–18,000 | 0–3,700 | Not reported |

| Incubation Temperature | 17–23°C | 36°C ± 1°C | N/A |

| Incubation Duration | 7 days | 2 days | N/A |

| Number of Bacterial Species Detected | Greater diversity | Lesser diversity | Not formally tested |

| Linear Correlation (R²) | \multicolumn{2}{c | }{0.7264} | Strong correlation |

Beyond the quantitative CFU differences, the study found that R2A agar supported the growth of a greater diversity of bacterial species compared to PCA agar [6]. This suggests that R2A medium not only recovers higher numbers of bacteria but also captures a broader spectrum of the microbial community present in purified water systems. Linear regression analysis demonstrated a relatively strong correlation between the counts obtained by both methods (R² = 0.7264), particularly after logarithmic transformation of the data, indicating that while absolute counts differ substantially, the methods generally correlate in detecting relative contamination levels [6].

Advanced Methodological Comparisons: Flow Cytometry versus Traditional HPC

Emerging Technology in Microbial Enumeration

While conventional HPC methods relying on CFU enumeration have been the standard for decades, emerging technologies like flow cytometry (FCM) present compelling alternatives for water quality monitoring. A 2025 study directly compared HPC and FCM for monitoring dialysis water quality, highlighting significant methodological differences [2]. Flow cytometry operates on fundamentally different principles than culture-based methods. FCM rapidly detects and measures physical and chemical characteristics of individual cells in a fluid stream as they pass through one or more lasers. When combined with viability stains such as those targeting DNA, FCM can distinguish between total and intact cell populations, providing information about the physiological state of the microbial community [2].

The technical workflow for FCM-based water monitoring involves sample collection, fluorescent staining of nucleic acids, and analysis using a flow cytometer that counts and characterizes thousands of cells per second. This approach provides several theoretical advantages, including dramatically reduced time-to-results (hours versus days), increased sensitivity for detecting low levels of contamination, and the ability to detect viable but non-culturable (VBNC) organisms that would not form colonies on traditional media [2]. For dialysis water monitoring specifically, this rapid detection capability enables real-time corrective actions, potentially enhancing patient safety.

Performance Comparison: HPC versus Flow Cytometry

The comparative study of dialysis water monitoring revealed fundamental differences in the information provided by these methodologies. While HPC measures only those microorganisms capable of forming colonies under specific culture conditions, FCM provides a broader assessment of the total microbial population, including intact cells that may not grow on the chosen culture media [2].

Table 2: Methodological Comparison: HPC versus Flow Cytometry for Water Quality Monitoring

| Parameter | Heterotrophic Plate Count (HPC) | Flow Cytometry (FCM) |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Basis | Viable, culturable bacteria | Total and intact cells via DNA staining |

| Time to Result | Typically 2-7 days | Less than 1 hour |

| Detection Limit | 1 CFU per filtered volume | Potentially higher sensitivity |

| VBNC Detection | No | Yes |

| Information Provided | CFU count only | Total cell count, intact cell count, community structure |

| Throughput Capacity | Low to moderate | High |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Established | Emerging |

| Key Advantage | Established standards and action levels | Speed and comprehensive profiling |

The study concluded that FCM offers higher sensitivity than HPC for microbial monitoring of dialysis water, potentially enabling earlier corrective actions [2]. However, the authors noted that widespread adoption of FCM in regulated environments like dialysis requires establishing corresponding maximum allowable levels and action levels, which currently exist primarily for HPC methodologies. This regulatory framework gap represents a significant barrier to implementation despite the technical advantages of flow cytometry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of HPC methodologies requires specific laboratory materials and reagents, each serving distinct functions in the microbial enumeration process. The following table details essential components for conducting heterotrophic plate count analyses, particularly comparing R2A and PCA media approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HPC Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| R2A Agar | Low-nutrient medium for cultivating water-borne heterotrophic bacteria; contains yeast extract, peptone, glucose, soluble starch [6] | Commercially prepared plates from suppliers like Chongqing Pangtong Company [6] |

| Plate Count Agar (PCA) | High-nutrient general purpose medium; contains beef extract, peptone, glucose, agar [6] | Commercially prepared plates meeting quality control standards [6] |

| Sterile Containers | Aseptic sample collection and transport | Sterile sampling tubes, bottles |

| Membrane Filters | Concentration of microorganisms from large water volumes (≥100 mL) | 0.45 μm pore size filters for bacterial retention [6] |

| Dilution Buffers | Creating serial dilutions for countable plates | Phosphate-buffered saline, peptone water |

| Incubators | Maintaining precise temperature conditions during culture | 17-23°C for R2A; 36±1°C for PCA [6] |

| Colony Counter | Accurate enumeration of CFUs | Manual click-counters, automated imaging systems |

Beyond these basic materials, methodological variations exist for different sample types. The pour plate method involves mixing the sample with molten agar cooled to approximately 40–45°C before solidification and incubation. The spread plate method applies a small sample volume onto the surface of pre-poured, solidified agar plates. The membrane filtration method filters the sample through a membrane, which is then placed on an agar plate—particularly useful for low-bioburden samples like purified waters [1] [6]. For laboratories handling numerous samples, automated colony counting systems using software like OpenCFU or commercial automated systems can significantly reduce counting time and improve objectivity, while also extracting additional data such as colony size and color [1].

The comparative analysis between R2A and PCA culture media demonstrates that methodological choices significantly impact HPC outcomes and, consequently, contamination risk assessments. The substantially higher bacterial counts obtained with R2A agar under extended, lower-temperature incubation conditions suggest that this approach more accurately reflects the true heterotrophic bacterial load in low-nutrient water systems like hospital purified water [6]. These findings have profound implications for quality control programs in pharmaceutical manufacturing, healthcare facilities, and water treatment operations, where accurate microbial assessment directly impacts product safety and patient health.

The emergence of alternative technologies like flow cytometry further challenges traditional HPC paradigms, offering faster results and potentially more comprehensive microbial community analysis [2]. However, the century-old HPC method retains advantages in regulatory acceptance, established action levels, and technical accessibility. Future methodological developments will likely focus on correlating results from advanced techniques like FCM with traditional CFU counts while establishing corresponding quality standards. For researchers and quality control professionals, these comparisons underscore that "what we measure" depends fundamentally on "how we measure," emphasizing that methodological specifications must be carefully considered when establishing monitoring protocols and interpreting HPC data for critical decision-making.

The Critical Role of HPC in Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Water Systems

In the highly regulated biomedical and pharmaceutical industries, water quality is not merely a utility concern but a critical component of product safety and efficacy. The monitoring of microbial contamination, primarily through Heterotrophic Plate Count (HPC) methods, serves as a vital indicator of water system control. Simultaneously, High-Performance Computing (HPC) has emerged as a transformative force in drug discovery and development. This guide explores the intersection of these two distinct yet acronymically similar fields, examining how computational power enhances our understanding of water system microbiology and provides robust frameworks for comparing methodological approaches in quality control. Within pharmaceutical water systems, heterotrophic bacteria can form biofilms on pipe surfaces and colonize distribution systems, posing significant risks to water quality [7]. Effective monitoring through HPC methods is therefore essential for identifying critical control points and ensuring water safety [7].

Heterotrophic Plate Count Methods: A Comparative Analysis

Understanding HPC in Pharmaceutical Water Context

Heterotrophic Plate Count (HPC) represents a standardized methodology for enumerating heterotrophic microorganisms—those requiring organic carbon for growth—in water samples. These microorganisms include bacteria, yeasts, and molds that are widely found in water systems [8]. In pharmaceutical settings, HPC testing serves to monitor the overall biological health of water systems and validate the effectiveness of water treatment processes [8]. While HPC bacteria in drinking water are generally not a direct health concern to the general public, specific strains can function as opportunistic pathogens that may infect immunocompromised individuals, a critical consideration for pharmaceutical products intended for vulnerable patient populations [9].

Regulatory bodies worldwide have established different HPC methodologies with varying cultivation parameters including media type, incubation temperature, and incubation duration. These methodological differences can significantly impact the outcome of analyses, making comparative understanding essential for pharmaceutical water quality assurance [10].

Table 1: Standard HPC Methods and Their Parameters

| Method Standard | Media Type | Incubation Temperature | Incubation Time | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIN EN ISO 6222 (European) | Yeast Extract Agar (YEA) | 37°C and 22°C | 48h (37°C), 72h (22°C) | Regulatory compliance in EU nations |

| US EPA Methods | R2A, PCA, or YEA | 20°C to 40°C (range) | 48h to 7 days (variable) | US regulatory framework |

| Alternative Methods | R2A (low nutrient) | 22°C to 35°C | 3-7 days | Extended recovery of stressed microbes |

| EasyDisc Platform | R2A, PCA, or YEA formulations | Standard incubator temperatures | 24-48 hours | Rapid testing across industries |

Comparative Experimental Data on HPC Methodologies

Research has demonstrated that variations in HPC methodology significantly impact both the quantitative results and the qualitative composition of detected microbial communities. Studies examining different media types and incubation temperatures reveal substantial differences in recovery rates and biodiversity measurements.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of HPC Methods Across Water Systems

| Study Context | Method Comparison | Key Findings | Impact on HPC Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bottled Water Production [7] | Point-of-use filtration systems | HPC increased from mean 227 CFU/mL (inlet) to 2,416 CFU/mL (outlet) after one month of use | Significant bacterial regrowth in treatment devices |

| Private Well Water [10] | YEA at 22°C vs. 37°C | Temperature showed statistically significant effect on community composition (p < 0.01) | Different bacterial families predominant at each temperature |

| Water Treatment Systems [7] | R2A vs. YEA media | Highest biodiversity detected at lower temperatures, particularly on R2A medium | Low-nutrient media recover more diverse microorganisms |

| PoU Treatment Units [9] | R2A agar incubation | 49 bacterial strains identified; 20 Gram-negative, 29 Gram-positive | Bacillus most frequently detected genus in input and output samples |

A study on Point-of-Use (PoU) water treatment units demonstrated concerning bacterial regrowth, with HPC levels increasing from a mean of 226.7 CFU/mL in input water to 2,416.4 CFU/mL in treated outlet water over a one-month operation period [9]. This highlights the importance of regular filter replacement and monitoring in pharmaceutical water systems. Molecular analysis of these systems identified 49 bacterial strains, with Bacillus being the most frequently detected genus in both inlet and outlet water samples [9]. Many identified strains were opportunistic pathogens potentially dangerous for immunocompromised populations, including Acinetobacter, Aeromonas, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas [9].

Experimental Protocols for HPC Method Comparison

Standard HPC Methodologies

Protocol 1: Membrane Filtration Method (Based on DIN EN ISO 6222)

- Sample Collection: Collect water samples in sterile containers containing sodium thiosulphate to neutralize residual chlorine [9].

- Filtration: Filter a defined volume (typically 100mL) through a 0.45μm nitrocellulose membrane filter [10].

- Plating: Transfer the membrane filter onto the appropriate agar medium (YEA for DIN standard; R2A for US EPA) [10].

- Incubation: Incubate plates at required temperatures (22°C for 72 hours and/or 37°C for 48 hours) [10].

- Enumeration: Count developed colonies and express results as colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) [11].

Protocol 2: Spread Plate Method (Alternative Approach)

- Sample Preparation: Agitate water samples by vortex mixing [7].

- Inoculation: Spread 0.1-1.0mL of sample evenly across the surface of prepared agar plates [7].

- Incubation: Incubate under appropriate temperature and duration conditions for selected method [10].

- Counting: Count colonies and calculate CFU/mL based on dilution factor and plated volume [11].

Advanced Molecular Identification Protocol

Protocol 3: Bacterial Identification via 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

- HPC Isolation: Pick characteristic colonies from HPC plates and restreak to ensure purity [7].

- DNA Extraction: Subculture overnight on R2A agar and extract genomic DNA using commercial kits [9].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify 16S rRNA gene using universal bacterial primers (8f and 1520r) [10].

- Cloning and Sequencing: Clone PCR products into sequencing vector and sequence with standard primers [10].

- Sequence Analysis: Compare obtained sequences with NCBI database using BLASTN for taxonomic identification [7].

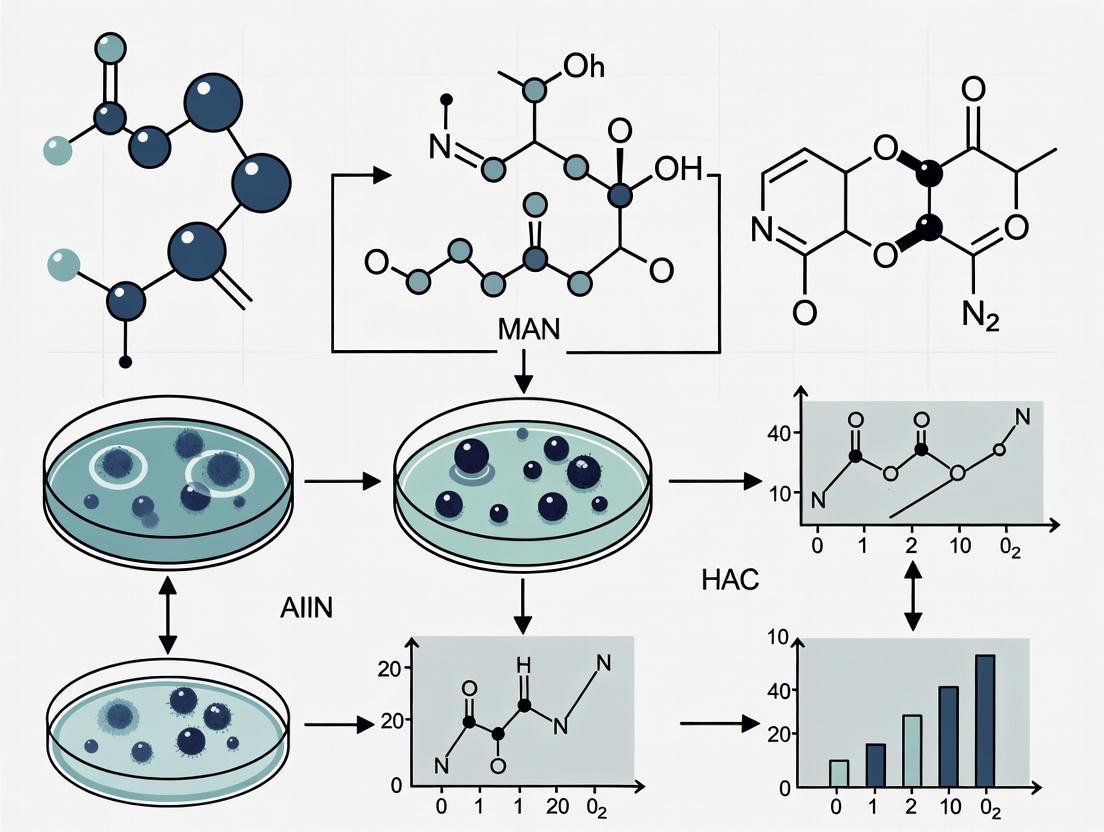

Visualization of HPC Method Selection and Outcomes

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process for HPC method selection and the expected outcomes based on experimental comparisons:

HPC Method Selection and Microbial Recovery Outcomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for HPC Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in HPC Analysis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| R2A Agar | Low-nutrient medium for recovery of stressed/chlorine-injured bacteria | US EPA methods; environmental water samples [10] |

| Yeast Extract Agar (YEA) | High-nutrient medium standard for European regulatory compliance | DIN EN ISO 6222 method; routine water monitoring [10] |

| Membrane Filters (0.45μm) | Concentration of microorganisms from water samples | Membrane filtration method [10] |

| Sodium Thiosulphate | Neutralization of residual chlorine in water samples | Sample preservation and collection [9] |

| EasyDisc Platform | Pre-prepared culture medium discs for simplified HPC testing | Rapid testing; eliminates media preparation [8] |

| PCR Reagents & Primers | Amplification of 16S rRNA gene for bacterial identification | Molecular identification of HPC isolates [10] |

The critical role of HPC monitoring in biomedical and pharmaceutical water systems demands careful method selection informed by comparative research. Experimental evidence demonstrates that incubation temperature significantly affects microbial community composition (p < 0.01), with lower temperatures (22°C) favoring recovery of naturally occurring Pseudomonadaceae and Aeromonadaceae, while higher temperatures (37°C) enhance detection of Enterobacteriaceae, Citrobacter spp., and Bacilli [10]. Media selection further influences outcomes, with R2A agar demonstrating superior biodiversity detection, particularly at lower temperatures [10]. These methodological considerations directly impact water safety management, especially given that HPC populations can increase significantly in treatment devices during operation, potentially elevating concentrations of opportunistic pathogens [9]. Pharmaceutical facilities must therefore align HPC method selection with their specific water system characteristics and monitoring objectives, implementing rigorous protocols at critical control points where water stagnation occurs and bacterial regrowth potential is highest [7].

For over a century, the heterotrophic plate count (HPC) has served as the gold standard for assessing microbial viability in diverse fields, from clinical diagnostics to water safety monitoring. This culture-dependent paradigm, however, rests on a critical assumption: that viable microorganisms will grow on artificial laboratory media. The discovery of the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state in 1982 fundamentally challenged this premise [12]. In this dormant state, bacteria retain metabolic activity and pathogenicity but fail to form colonies on routine agar plates, leading to a potentially dangerous underestimation of viable microbial counts in environmental, clinical, and industrial samples [12] [13]. This article examines the limitations of traditional HPC methods in the context of the VBNC problem and compares their performance against modern culture-independent approaches, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to advance the field of microbial detection.

The VBNC State: A Fundamental Challenge to Culture-Based Methods

Defining Characteristics of VBNC Cells

The VBNC state represents a survival strategy adopted by numerous bacterial species when confronted with environmental stress. VBNC cells are characterized by a loss of culturability on standard media while maintaining metabolic activity, membrane integrity, and genetic potential for resuscitation [12]. Key differentiating features from both culturable and dead cells include:

- Metabolic Activity: VBNC cells continue respiration, produce ATP, and incorporate amino acids into proteins, distinguishing them from dead cells [12].

- Genetic Integrity: They maintain intact membranes that retain chromosomal and plasmid DNA [12].

- Morphological Changes: Cells typically undergo reductive division, becoming smaller and often changing from rod-shaped to coccoid forms [12].

- Enhanced Resistance: VBNC cells demonstrate increased tolerance to environmental stresses, including antibiotics, temperature extremes, and chemical disinfectants [12].

Induction and Public Health Significance

Entry into the VBNC state can be triggered by multiple stressors commonly employed in disinfection protocols or found in natural environments, including nutrient starvation, temperature shifts, osmotic stress, and exposure to disinfectants such as chlorine [12] [14]. Of particular concern to public health is that numerous human pathogens can enter this state, including Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterococcus faecalis [12] [13] [15].

Critically, many pathogens retain virulence potential in the VBNC state and can resuscitate when conditions become favorable, posing a "hidden" risk for disease outbreaks [12] [16]. For example, VBNC Salmonella Enteritidis has been shown to exacerbate colitis severity and compromise intestinal barrier function in mouse models [16]. The persistence of VBNC pathogens throughout drinking water systems represents a significant challenge for accurate risk assessment [13].

Comparative Analysis of Detection Methods

Methodological Limitations of HPC

The heterotrophic plate count method suffers from fundamental limitations in detecting VBNC cells:

- Non-culturability: By definition, VBNC cells do not form colonies on routine media, leading to false negatives [12].

- Nutrient Imbalance: Standard high-nutrient media like Plate Count Agar (PCA) do not support the growth of stressed or dormant bacteria adapted to low-nutrient environments [6].

- Temporal Constraints: Standard incubation times (24-48 hours) are insufficient for the resuscitation and growth of VBNC cells [6].

Table 1: Comparison of HPC Media and Conditions for Detecting Environmental Bacteria

| Media Type | Nutrient Level | Incubation Conditions | Detection Capability | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate Count Agar (PCA) | High | 36°C ± 1°C for 48 hours | Limited for VBNC | High nutrients inhibit stressed cells; unsuitable temperature and duration |

| R2A Agar | Low | 17-23°C for 7 days | Enhanced for heterotrophic aquatic bacteria | Extended incubation time required |

| TSA | High | 37°C for 24-48 hours | Limited for VBNC | Designed for clinical isolates, not environmental strains |

Recent comparative studies demonstrate these limitations conclusively. In an analysis of hospital purified water, the R2A culture method (low nutrients, extended incubation) detected significantly higher heterotrophic bacterial counts compared to traditional PCA, with medians of 200 CFU versus 6 CFU respectively [6]. This confirms that methodology selection dramatically impacts the accuracy of viable bacterial enumeration.

Advanced Detection Strategies for VBNC Cells

Molecular and cytometric approaches bypass the culturability limitation by targeting indicators of cellular viability rather than growth capacity.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of VBNC Detection Methods

| Method | Target | Detection Principle | Time to Result | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPC | Culturable cells | Growth on synthetic media | 2-7 days | Low cost; standardized | Misses VBNC cells |

| PMA-qPCR | Viable cells (membrane integrity) | PCR amplification from cells with intact membranes | 3-5 hours | Specific; quantitative | May miss cells with intact membranes but low metabolic activity |

| PMA-ddPCR | Viable cells (membrane integrity) | Absolute quantification without standard curve | 3-5 hours | High precision; no standard curve needed | Higher cost; complex workflow |

| Flow Cytometry (FCM) | Total/Intact cells | Fluorescent staining of nucleic acids | <1 hour | Rapid; distinguishes intact/damaged cells | Requires specialized equipment |

| CTC-FCM | Metabolic activity | Reduction of tetrazolium salts | 2-4 hours | Measures metabolic activity directly | Staining efficiency variable |

PMA-based PCR methods utilize propidium monoazide dye, which penetrates only membrane-compromised (dead) cells and covalently cross-links to DNA upon light exposure, preventing its amplification. This allows quantification of viable cells (with intact membranes) by subtracting PMA-treated signals from total DNA quantification [15] [14]. Recent advancements include using longer gene segments in PMA-qPCR assays to reduce false positives from short DNA fragments released from dead cells [14].

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) offers absolute quantification without standard curves, with recent studies demonstrating its application for quantifying VBNC Klebsiella pneumoniae using multiple single-copy genes (KP, rpoB, and adhE) for enhanced accuracy [15].

Flow cytometry provides rapid enumeration of total and intact cells using DNA staining, with studies showing higher sensitivity than HPC for microbial monitoring of dialysis water [2]. This method can distinguish bacterial communities with low and high nucleic acid content (LNA/HNA), providing additional information on community dynamics [2].

Experimental Protocols for VBNC Research

Protocol 1: Induction and Quantification of VBNCPseudomonas aeruginosa

This protocol, adapted from Shanghai University research, details the induction of VBNC state by disinfectants and quantification using PMA-qPCR [14].

Materials:

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain (e.g., CMCC(B)10104)

- Luria-Bertani (LB) medium

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.0 ± 0.1)

- Sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) solution

- PMA dye (Biotium)

- DNA extraction kit

- qPCR system and reagents

Procedure:

- Culture P. aeruginosa in LB medium to logarithmic growth phase.

- Harvest cells by centrifugation at 6,869 × g for 10 min and wash with PBS.

- Resuspend in sterile water to ~10⁷ CFU/mL.

- Disinfection Treatment: Add NaClO (0.5-3 mg/L) with continuous stirring.

- Collect samples at timed intervals (0, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 min).

- Quench residual chlorine with sodium thiosulfate (0.1 mM).

- Viability Assessment:

- HPC: Spread samples on nutrient agar, incubate at 37°C for 24h

- PMA-qPCR: Treat 500μL samples with PMA, incubate in dark for 5min

- Expose to 650W halogen light on ice for 5min

- Filter through 0.22μm membrane, extract DNA

- Perform qPCR with species-specific primers

- Calculate VBNC cells = PMA-qPCR viable count - HPC culturable count

Regrowth Potential Assessment:

- Incubate VBNC cells in LB medium at 37°C with shaking

- Monitor culturability recovery bihourly via HPC

Protocol 2: Absolute Quantification of VBNCKlebsiella pneumoniaeUsing PMA-ddPCR

This protocol enables absolute quantification without standard curves, optimized for intestinal pathogen detection [15].

Materials:

- High alcohol-producing K. pneumoniae (HiAlc Kpn) strain

- Artificial seawater (ASW: 40 g/L sea salt)

- PMA dye

- Droplet digital PCR system

- Primers for single-copy genes (KP, rpoB, adhE)

Procedure:

- Culture HiAlc Kpn in LB broth to OD₆₀₀ = 1.0.

- Resuspend in ASW at ~10⁸ CFU/mL.

- VBNC Induction: Incubate at 4°C, monitoring culturability every 5 days on LB agar.

- PMA Optimization: Test PMA concentrations (5-200μM) and incubation times (5-30min).

- DNA Extraction: After optimal PMA treatment, extract DNA.

- ddPCR Analysis:

- Partition samples into ~20,000 droplets

- Perform PCR amplification with three single-copy gene targets

- Analyze endpoint fluorescence to count positive/negative droplets

- Calculate absolute copy numbers using Poisson statistics

- Resuscitation Assessment: Transfer VBNC cells to fresh media, monitor regrowth.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for VBNC Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Application | Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMA Dye | Viability PCR | Selective DNA modification in dead cells | Distinguishes viable cells in qPCR/ddPCR [15] [14] |

| R2A Agar | Cultivation | Low-nutrient medium for stressed bacteria | Enhanced recovery of aquatic microorganisms [6] |

| CTC Stain | Metabolic activity | Tetrazolium reduction to fluorescent formazan | Measuring respiratory activity in VBNC cells [13] |

| LIVE/DEAD BacLight | Membrane integrity | Differential nucleic acid staining | Flow cytometric enumeration of intact cells [2] |

| ATP Assay Kits | Metabolic activity | Luciferase-based ATP quantification | Confirming metabolic activity in VBNC cells [14] |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

VBNC Detection Method Comparison

VBNC State Transition Pathways

The VBNC state represents a fundamental challenge to traditional microbiology paradigms and necessitates a methodological evolution from culture-dependent to function-based detection approaches. Quantitative comparisons demonstrate that molecular methods (PMA-qPCR, PMA-ddPCR) and flow cytometry offer significant advantages over HPC for comprehensive microbial risk assessment, particularly through their ability to detect the entire spectrum of viable organisms. Future research directions should focus on standardizing these alternative methods, establishing threshold values for different sample types, and developing targeted strategies to eliminate or prevent VBNC state induction in clinical and industrial settings. As our understanding of microbial dormancy deepens, so too must our analytical approaches evolve to accurately assess and mitigate the hidden risks posed by viable but non-culturable pathogens.

From Agar to Algorithms: A Deep Dive into HPC Methodologies and Their Applications

The enumeration of viable microorganisms is a cornerstone of microbiological analysis in water quality, pharmaceutical development, and clinical diagnostics. Among the most established techniques are the heterotrophic plate count (HPC) methods, primarily comprising pour plate, spread plate, and membrane filtration. These methods are essential for assessing microbial contamination, guiding disinfection protocols, and ensuring public health safety, particularly in sensitive environments like healthcare facilities [6]. While they share the common principle of cultivating viable cells on solid media to form countable colonies, they differ significantly in their procedures, applications, and performance characteristics. Accurate microbial monitoring is critical, as contaminated water in clinical settings can pose a serious risk of nosocomial infections [6]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three traditional culture methods, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers and professionals in selecting the appropriate technique for their specific applications.

The pour plate method involves mixing a sample with molten agar and pouring the mixture into a Petri dish [17]. The spread plate technique evenly distributes a liquid sample onto the surface of a pre-solidified agar plate [17]. Membrane filtration passes the entire liquid sample through a sterile membrane filter, which traps microorganisms; the filter is then placed on a nutrient agar plate [18].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and a quantitative performance comparison based on published studies.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Traditional Culture Methods

| Feature | Pour Plate | Spread Plate | Membrane Filtration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Addition | Mixed with molten agar [17] | Spread onto solidified medium surface [17] | Filtered through a membrane [18] |

| Primary Use | Separation and quantification of viable microorganisms [17] | Isolation and easy counting of individual bacterial colonies [17] | Testing for contamination in large sample volumes [18] |

| Quantifiable Organisms | Anaerobes (as they are embedded within the agar) [17] | Aerobes, facultative anaerobes [17] | Aerobes; suitable for a wide range of microorganisms [18] |

| Sample Volume | Typically up to 2 mL [18] | Typically up to 0.5 mL [18] | Large volumes (e.g., 100 mL or more) [18] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison in Microbial Enumeration

| Performance Metric | Pour Plate | Spread Plate | Membrane Filtration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reported Accuracy | Comparatively higher accuracy [17] | Comparatively lower accuracy [17] | High accuracy and sensitivity from testing the entire sample [18] |

| Typical Sample Volume Used | 1 mL [6] | 0.1 mL or less [19] | 100-200 mL [6] [18] |

| Effect on Microbial Growth | Can be stressful for heat-sensitive organisms due to warm agar | Surface growth only; suitable for organisms requiring oxygen | Concentrates organisms; allows for efficient nutrient transfer [18] |

| Colony Isolation for ID | Difficult to pick isolated colonies from within agar | Excellent for picking and isolating discrete surface colonies [18] | Colonies easily transferred from membrane surface for further analysis [18] |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

To ensure reliable and reproducible results, strict adherence to aseptic technique is paramount throughout all procedures. This includes sterilizing all instruments and media, working in a disinfected and tidy area, and using a Bunsen burner to create a sterile field updraft on the laboratory bench (or a biosafety cabinet for BSL-2 organisms) [19].

Detailed Protocol: Pour Plate Method for Bacterial Enumeration

The pour plate method is commonly used to determine the concentration of viable bacteria in a liquid sample [19].

- Preparation: Label sterile Petri dishes and organize all materials. Ensure agar tubes are sterilized and kept molten in a water bath at approximately 45-50°C.

- Inoculation: Using aseptic technique, transfer a specific volume of the sample (e.g., 1.0 mL from an appropriate dilution) into the sterile Petri dish [6].

- Pouring: Quickly pour approximately 15-20 mL of the molten, cooled agar medium (e.g., Plate Count Agar (PCA) or Reasoner’s 2A (R2A) agar) into the dish.

- Mixing: Gently swirl the dish on the bench top to mix the sample and agar thoroughly, ensuring even distribution without splashing the sides.

- Solidification: Allow the agar to solidify completely at room temperature.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate in an inverted position at the required temperature and duration for the specific microorganism and medium (e.g., 36°C ± 1°C for 48 hours for PCA, or 17-23°C for 7 days for R2A) [6].

Detailed Protocol: Membrane Filtration for Water Analysis

Membrane filtration is ideal for testing large volumes of water where microbial concentration is expected to be low [6] [18].

- Apparatus Set-up: Aseptically assemble the membrane filtration unit, placing a sterile membrane filter (typically 0.45 μm pore size) into the receptacle.

- Filtration: Pour the entire water sample (e.g., 100-200 mL) into the funnel and apply a vacuum to draw the liquid through the filter. Any microorganisms in the sample are retained on the membrane's surface [6] [18].

- Transfer: Using flamed forceps, carefully remove the membrane filter and place it onto the surface of a pre-poured, nutrient-rich agar plate (e.g., R2A agar), ensuring no air bubbles are trapped underneath [6].

- Incubation: Incub the plate right-side up at the specified conditions. Nutrients and moisture from the agar diffuse through the membrane to support the growth of colonies on its surface [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

The selection of appropriate culture media and materials is critical for the success of any plating method. The choice between high-nutrient and low-nutrient media can significantly impact recovery rates, especially for environmental or stressed communities.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Plate Count Agar (PCA) | A high-nutrient medium for enumerating heterotrophic bacteria [6]. | Culturing at 36°C for 48 hours for general HPC analysis [6]. |

| Reasoner’s 2A Agar (R2A) | A low-nutrient medium designed to recover stressed bacteria from water systems [6]. | Culturing at 17-23°C for 7 days for improved recovery of waterborne heterotrophs [6]. |

| Mixed Cellulose Ester Membrane Filter | A general-purpose filter (0.45 μm) for trapping bacteria during membrane filtration [18]. | Concentrating microorganisms from large volume water samples (e.g., dialysis water, purified water) [6] [18]. |

| Supor Membrane Filter | A polyethersulfone membrane with high flow rates, available in 0.2 μm pore size for critical applications [18]. | Pharmaceutical testing where capture of all potential contamination is required [18]. |

Method Selection Workflow and Data Interpretation

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting the most appropriate plating method based on sample characteristics and research goals.

Quantitative Data Interpretation: Colony counts are expressed as Colony-Forming Units (CFU) per mL or per total volume filtered [19]. It is critical to note that different media and methods yield different results. A 2024 study on hospital purified water demonstrated that the R2A culture method recovered a significantly higher median number of heterotrophic bacteria (200 CFU) compared to the PCA method (6 CFU), highlighting that the low-nutrient R2A medium was more effective for this water type [6]. Furthermore, linear regression analysis showed a strong correlation (R² = 0.7264) between the counts from the two media after logarithmic transformation, indicating a predictable relationship despite absolute count differences [6].

The pour plate, spread plate, and membrane filtration methods each occupy a vital niche in the microbiologist's toolkit. The choice of method is a prerequisite for ensuring accurate results and should be guided by the sample volume, the physiological characteristics of the target microorganisms, and the required sensitivity [6]. While pour plate and spread plate are foundational techniques, membrane filtration offers distinct advantages in sensitivity for large-volume samples and is increasingly supported by modern membrane technology [18]. Researchers must also carefully select the growth medium, as demonstrated by the superior recovery of waterborne bacteria on R2A agar versus PCA [6]. By understanding the comparative strengths, limitations, and protocols of each method, professionals in research and drug development can make informed decisions to ensure the reliability of their microbial quality assessments.

The accurate enumeration of heterotrophic bacteria is a cornerstone of microbiological monitoring in diverse fields, from clinical settings to water safety and pharmaceutical development. The choice of culture medium critically influences the recovery and growth of microorganisms, particularly those that are stressed, injured, or adapted to oligotrophic environments. For decades, the high-nutrient Plate Count Agar (PCA) has been a standard method. However, the low-nutrient Reasoner's 2A Agar (R2A) has emerged as a powerful alternative that can significantly enhance the recovery of environmental and stressed microbes. This guide provides an objective comparison of PCA and R2A performance, underpinned by recent experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their selection of appropriate heterotrophic plate count methods.

Fundamental Media Characteristics and Formulation

The core difference between PCA and R2A lies in their composition and intended purpose, which directly impacts their interaction with microbial communities.

Plate Count Agar (PCA) is a high-nutrient medium traditionally formulated for the enumeration of microorganisms from food products. Its key ingredients typically include pancreatic digest of casein (a source of nitrogen and amino acids), yeast extract (providing vitamins and coenzymes), dextrose as a fermentable carbohydrate, and agar. This rich composition supports the rapid growth of robust, non-fastidious microorganisms under optimal conditions.

Reasoner's 2A Agar (R2A) is a low-nutrient medium specifically developed to recover bacteria from potable water, which is typically an oligotrophic (nutrient-poor) environment [20] [6]. Its formulation includes lower concentrations of peptones and yeast extract compared to PCA. Crucially, it contains a wider variety of carbon sources, such as glucose, soluble starch, and sodium pyruvate. Sodium pyruvate is particularly important as it acts as a scavenger of reactive oxygen species, thereby aiding the recovery of oxidative-stress-damaged cells.

Table 1: Key Compositional and Incubation Differences between PCA and R2A

| Characteristic | Plate Count Agar (PCA) | R2A Agar |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Level | High | Low |

| Primary Carbon Sources | Dextrose | Glucose, Soluble Starch, Sodium Pyruvate |

| Nitrogen & Vitamin Sources | Pancreatic digest of casein, Yeast extract | Proteose peptone, Casamino acids, Yeast extract |

| Typical Incubation Temperature | 36 ± 1 °C | 17 - 23 °C |

| Typical Incubation Time | 48 ± 2 hours | 5 - 7 days (168 hours) |

| Developed For | Food microbiology | Oligotrophic aquatic environments |

Comparative Experimental Data and Performance

Recent studies across various applications have consistently demonstrated the superior recovery of heterotrophic bacteria using R2A, especially from low-nutrient or treated water systems.

A 2024 study directly compared the two media for monitoring heterotrophic bacteria in hospital purified water, a critical environment for preventing nosocomial infections [20] [6]. The researchers analyzed 142 water samples from sources like dental unit water and endoscope rinse water. The results were stark: the median heterotrophic bacterial colony count on R2A was 200 CFU (Q1–Q3: 25–18,000), vastly exceeding the median of 6 CFU (Q1–Q3: 0–3,700) recovered on PCA. Statistical analysis confirmed that the total number of colonies cultured in R2A medium for 7 days was significantly higher than that cultured in PCA medium for 2 days (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the number of bacterial species detected was greater on R2A, indicating its ability to support a wider diversity of microbes [20].

This trend is not new. A 1998 study on natural mineral water found that using R2A with spread plates yielded colony counts that were over 343% higher after 7 days of incubation at 22°C compared to the standard PCA pour plate method [21]. The study also highlighted that R2A facilitated the recovery of specific bacterial genera, such as Flavobacterium and Arthrobacter, which were not recovered using PCA, underscoring its greater inclusivity.

Table 2: Summary of Quantitative Comparative Studies

| Study Context (Source, Year) | Sample Type | Key Quantitative Finding | Statistical & Diversity Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Water [20] [6] (2024) | Dental & endoscope rinse water (142 samples) | R2A Median: 200 CFUPCA Median: 6 CFU | P < 0.05; R2A supported a greater number of bacterial species. |

| Natural Mineral Water [21] (1998) | Bottled natural mineral water (112 samples) | R2A/spread plates yielded >343% higher counts than PCA/pour plates. | Genera like Flavobacterium and Arthrobacter were exclusively recovered on R2A. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of the comparative data presented, this section outlines the standard methodologies employed in the cited research.

- Sampling: Aseptically collect water samples from the designated points (e.g., dental three-purpose guns, endoscope rinse stations). Allow water to flow for 30 seconds before collecting the sample in a sterile container.

- Sample Transport and Storage: Store samples at low temperature (e.g., in a low-temperature refrigerator) and process within 2 hours of collection.

- Inoculation (Pour Plate Method):

- For water with expected high microbial load (e.g., oral diagnosis water), prepare tenfold and 100-fold dilutions of the sample.

- Aseptically transfer 1.0 ml of each dilution onto sterile petri dishes.

- For each dilution, prepare parallel plates by pouring approximately 15-20 ml of molten, cooled PCA and R2A agar separately. Gently swirl the plate to mix the inoculum with the medium.

- Include a blank control for each medium batch.

- Inoculation (Membrane Filtration Method):

- For water with expected low microbial load (e.g., endoscope rinse water), filter 20 ml and 100 ml volumes of water through a 0.45 μm pore-size membrane filter.

- Aseptically transfer the filter membrane onto the surface of pre-poured PCA and R2A agar plates.

- Incubation:

- Incubate PCA plates at 36 ± 1 °C for 48 hours.

- Incubate R2A plates at 17 - 23 °C for 168 hours (7 days).

- Enumeration and Analysis: Count the colonies on each plate and calculate the colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/ml). For identification, colonies can be subjected to further analysis like mass spectrometry (e.g., using a VITEK MS system).

General Workflow for Media Comparison

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key decision points in a standard media comparison experiment, as described in the protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Selecting the appropriate materials is fundamental to executing a valid media comparison. The following table details essential items and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Media Comparison Studies

| Item | Function / Purpose | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Plate Count Agar (PCA) | High-nutrient control medium for benchmarking; supports growth of non-fastidious organisms. | Commercially available dehydrated powder or ready-made plates. |

| Reasoner's 2A Agar (R2A) | Low-nutrient test medium for recovery of stressed, injured, or oligotrophic bacteria. | Commercially available dehydrated powder or ready-made plates. |

| Sterile Sampling Containers | Aseptic collection and transport of liquid samples to prevent contamination. | Whirl-Pak bags, sterile borosilicate glass or plastic bottles. |

| Membrane Filtration System | Concentration of microorganisms from large volume or low-bioburden samples. | 0.45 μm pore-size mixed cellulose ester filters, filtration manifolds. |

| Dilution Blanks | Preparation of serial dilutions for samples with high microbial load to obtain countable plates. | Buffered Peptone Water, Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), sterile tubes. |

| Incubators | Providing precise, controlled temperature conditions for optimal and comparable microbial growth. | Temperature range covering 20-37°C, with consistent thermal uniformity. |

| Automated Colony Counter | Standardized, objective enumeration of colony-forming units, reducing operator bias and error. | Systems like ProtoCOL3 [22]; ensure validation against manual counts. |

| Microbial Identification System | Taxonomic characterization of recovered colonies to assess diversity and media selectivity. | MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry (e.g., VITEK MS) [20], 16S rRNA sequencing. |

The body of evidence clearly demonstrates that the choice between high-nutrient PCA and low-nutrient R2A has profound implications for the outcome of heterotrophic plate counts. While PCA remains a valid standard for certain samples like foods, R2A is demonstrably superior for the recovery of stressed, injured, and slow-growing bacteria from oligotrophic environments such as purified water systems [20] [6] [21]. Its formulation, coupled with extended incubation at a lower temperature, more closely mimics the natural conditions of these microbes, leading to higher counts and greater biodiversity. For researchers and professionals where the accurate assessment of microbial contamination is critical—such as in pharmaceutical water systems, medical device rinses, and potable water monitoring—adopting R2A as the primary medium provides a more complete and realistic picture of microbiological quality.

The heterotrophic plate count (HPC) method has long been the standard technique for quantifying microorganisms in environmental and clinical samples. However, its limitations—including long incubation times, low sensitivity, and the inability to detect viable but non-culturable (VBNC) organisms—have driven the adoption of rapid alternative methods [6] [23] [2]. This guide objectively compares three key alternative methods: SimPlate (as a representative culture-based method), Flow Cytometry (FCM), and quantitative PCR (qPCR) with copies/mL quantification.

Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations for microbial analysis, making them suitable for different applications in research, pharmaceutical development, and clinical diagnostics. Understanding their performance characteristics, experimental requirements, and output data is essential for selecting the appropriate method for specific research questions.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of the three methods based on current research findings.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of rapid microbiological methods

| Parameter | SimPlate (Culture-Based) | Flow Cytometry (FCM) | qPCR (copies/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| What It Measures | Colony-forming units (CFUs) | Total/intact cell counts via fluorescence | Gene copies/µL (specific DNA targets) |

| Detection Time | 2-7 days [6] [2] | <1 hour [2] | 2-4 hours [24] |

| Limit of Detection | Varies with media; generally >10 CFU/mL | Potentially higher sensitivity than HPC [2] | <10 copies/µL demonstrated [24] |

| Key Output Metrics | CFU/mL | Total/Intact cell counts, bacterial fingerprint (LNA/HNA) [2] | Ct values, gene copies/µL [24] |

| Throughput | Moderate | High | High |

| Information Level | Viable, culturable organisms only | Viability (with stains), population structure, community dynamics [2] | Specific target presence/quantity; does not indicate viability |

| Typical Applications | Water quality testing, pharmaceutical quality control | Dialysis water monitoring [2], immune cell profiling [25] [26] | Pathogen detection [24], gene expression analysis [27] |

| Key Advantages • Familiar, standardized• Does not require specialized equipment | • Rapid results enabling real-time action [2]• High sensitivity• Provides community structure data | • Exceptional specificity and sensitivity [24]• Can detect non-culturable organisms• Quantitative | |

| Key Limitations • Long incubation period• Low sensitivity• Only detects culturable organisms [23] | • Requires specialized instrumentation and expertise• Limited established regulatory limits | • Does not distinguish live/dead cells• Susceptible to PCR inhibitors [24] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Flow Cytometry (FCM) for Microbial Water Monitoring

Recent studies have validated FCM for dialysis water quality monitoring, demonstrating its advantages over traditional HPC methods [2].

- Sample Collection and Staining: Water samples are collected aseptically. A viability stain, such as a nucleic acid-binding dye (e.g., SYBR Green I with propidium iodide), is added to discriminate between total and intact bacterial cells. Intact cells are considered a potential viability indicator [2].

- Instrument Analysis: Stained samples are run through a flow cytometer. The instrument measures fluorescence and light scatter characteristics of individual particles as they pass a laser.

- Data Analysis: Bacterial populations are identified based on their fluorescence signature. Key parameters include:

- Total Cell Count (TCC): The number of all stained particles.

- Intact Cell Count (ICC): The number of particles with intact membranes.

- Bacterial Community Structure: Analysis of sub-populations with low and high nucleic acid content (LNA/HNA) provides a "flow cytometric fingerprint" of the microbial community [2].

qPCR for Specific Pathogen Detection

A 2025 study established a validated TaqMan qPCR method for detecting Haemophilus parasuis (HPS), which exemplifies a robust qPCR protocol [24].

- Primer and Probe Design: Primers and a hydrolytic (TaqMan) probe are designed to bind to a conserved, specific region of the target organism's genome. For HPS, the INFB gene was targeted to ensure specificity over other Haemophilus species [24].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Total nucleic acid is extracted from samples using a magnetic bead-based kit. For complex matrices like blood or feces, the lysis protocol may be modified to improve yield and purity [24].

- Amplification Reaction Setup: The reaction mixture typically includes:

- 10 µL of 2x qPCR Premix

- 0.5 µL each of forward and reverse primers (10 µM concentration)

- 0.5 µL of probe (10 µM concentration)

- 1-2 µL of DNA template

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 µL [24].

- Thermocycling and Analysis: The qPCR run uses conditions like: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s and 60°C for 45 s. The cycle threshold (Ct) is determined for each sample, and the quantity is calculated against a standard curve of known copy numbers [24].

Advanced Computational Flow Cytometry

For complex immunophenotyping, advanced computational models like the Multi-Sample Gaussian Mixture Model (MSGMM) can be applied. This approach fits a joint statistical model to multiple FCM samples simultaneously, keeping cell population parameters fixed across samples but allowing their proportional abundances to vary. This facilitates direct comparison of cell populations across samples and enhances the detection of rare cell types [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential reagents and materials required for implementing these methods, as cited in recent literature.

Table 2: Key research reagents and their functions

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| R2A Agar Medium | Low-nutrient culture medium for cultivating heterotrophic bacteria from water systems. | Promoted greater recovery of diverse bacteria from hospital purified water compared to nutrient-rich PCA medium [6]. |

| SYBR Green I / Propidium Iodide | Nucleic acid staining dyes for differentiating total and intact bacterial cells in FCM. | Used for microbial monitoring of dialysis water to obtain total and intact cell counts [2]. |

| TaqMan Probes | Hydrolytic fluorescent probes for target-specific detection in qPCR, offering high specificity. | Enabled specific detection of Haemophilus parasuis by targeting the INFB gene [24]. |

| Di-4-ANEPPDHQ | Voltage-sensitive dye that detects changes in membrane lipid order. | Differentiated macrophage phenotypes (M1/M2) based on membrane potential via fluorescence shifts [25]. |

| CD Marker Antibodies (e.g., CD86, CD206) | Antibodies conjugated to fluorophores for detecting specific cell surface proteins via flow cytometry. | Used to identify and distinguish M1 (CD86, CD64) and M2 (CD206) macrophage polarization states [25]. |

| Magnetic Bead Nucleic Acid Kits | For purification of high-quality DNA/RNA from complex sample matrices. | Extracted nucleic acids from clinical samples (blood, tissue) for reliable downstream qPCR analysis [24]. |

Visualized Workflows and Logical Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting an appropriate microbial detection method based on key research questions and requirements.

Method Selection Decision Pathway

This second diagram contrasts the fundamental operational workflows of Flow Cytometry and qPCR, highlighting their core procedural differences.

Core Workflow Comparison: FCM vs. qPCR

The move away from exclusive reliance on traditional heterotrophic plate count methods represents a significant advancement in microbial analysis. Flow cytometry and qPCR offer powerful, complementary capabilities for researchers and drug development professionals.

- Flow Cytometry is the superior choice for rapid, viability-based enumeration and understanding microbial community structure, enabling real-time decision-making [2].

- qPCR provides unmatched specificity and sensitivity for detecting and quantifying specific genetic targets, making it indispensable for pathogen identification and molecular diagnostics [24].

The optimal method depends entirely on the research question. For comprehensive analysis, an integrated approach that leverages the strengths of multiple techniques often yields the most robust and actionable data, ultimately accelerating research and development timelines and improving product and patient safety.

Microbiological monitoring is a critical component of quality assurance in clinical, pharmaceutical, and research settings. Accurate assessment of microbial contamination in water, pharmaceuticals, and environmental samples is essential for patient safety, product quality, and research validity. The heterotrophic plate count (HPC) method has served as the traditional cornerstone for this monitoring for over a century, providing a measure of viable microorganisms in samples [28]. However, evolution in methodology has led to multiple HPC approaches and emerging alternative technologies, creating a complex landscape for professionals selecting the optimal method for their specific application. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methods, supported by experimental data, to inform evidence-based selection for diverse settings.

Understanding Heterotrophic Plate Count (HPC): Principles and Variants

The Heterotrophic Plate Count is a culture-based method designed to quantify viable heterotrophic microorganisms—bacteria, yeasts, and molds—that require organic carbon for growth [29]. The fundamental principle involves inoculating a sample onto a nutrient medium, incubating under controlled conditions, and counting the resulting colonies to calculate colony-forming units (CFU) per volume [30].

Core HPC Methodologies

Three principal methods are commonly employed for HPC testing, each with distinct procedural variations and advantages:

- Pour Plate Method: The sample is mixed with molten, cooled agar and poured into a petri dish. This method is simple but subjects bacteria to potential heat stress [29].

- Spread Plate Method: A small volume of sample is spread onto the surface of pre-poured, solidified agar. This eliminates heat stress but limits the sample volume that can be tested [30] [29].

- Membrane Filtration Method: The sample is filtered through a membrane, which is then placed on a nutrient pad or agar surface. This allows for testing larger volumes and is particularly effective for samples with low bacterial counts [29].

Critical Variables in HPC Methodology

The outcome of HPC testing is highly influenced by several variables, making standardization crucial for comparative analysis.

Culture Media: The choice of nutrient medium significantly impacts the types and quantities of bacteria recovered.

- Plate Count Agar (PCA): A high-nutrient medium typically incubated at 36°C ± 1°C for 48 hours. It is widely used but may fail to recover slow-growing or stressed bacteria from nutrient-poor environments like purified water [20].

- Reasoner's 2A Agar (R2A): A low-nutrient medium incubated at lower temperatures (17–23°C) for longer durations (5-7 days). This method is better suited for enumerating heterotrophic bacteria from water systems, as it promotes the growth of a broader range of indigenous aquatic bacteria [20]. A 2024 study demonstrated that the R2A method yielded significantly higher bacterial counts from hospital purified water compared to PCA, with medians of 200 CFU and 6 CFU, respectively [20].

Incubation Conditions: Temperature and duration directly influence the microbial populations recovered. Lower temperatures and extended incubation times favor the growth of environmental bacteria.

Table 1: Comparison of Common HPC Culture Media

| Medium | Nutrient Profile | Typical Incubation | Primary Applications | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate Count Agar (PCA) | High-nutrient | 36°C ± 1°C for 48 hours | Food, pharmaceutical products | Standardized, rapid results |

| R2A Agar | Low-nutrient | 17-23°C for 5-7 days | Drinking water, purified water (clinical/pharma) | Recovers a wider variety of stressed and slow-growing aquatic bacteria |

| SimPlate | Proprietary substrates | 35°C for 48 hours | Dental unit waterlines, commercial testing | High throughput, reduced labor |

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Monitoring Methods

Selecting the appropriate method requires a clear understanding of the performance characteristics of each option. The following comparison contrasts traditional HPC with its variants and a modern alternative.

Traditional HPC vs. Rapid Alternative: Flow Cytometry

Flow Cytometry (FCM) has emerged as a powerful, rapid alternative to culture-based methods. It uses DNA staining to quantify total and intact cell counts in a sample without the need for incubation [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison: HPC vs. Flow Cytometry

| Parameter | Heterotrophic Plate Count (HPC) | Flow Cytometry (FCM) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Culture-based growth on agar media | Fluorescent staining and cell counting |

| Analysis Time | 2-7 days | ~15 minutes [31] |

| Measurement | Colony-Forming Units (CFU/mL) | Total Cell Count (TCC) & Intact Cell Count (ICC) |

| Detectable Fraction | <1% of total bacterial community (only culturable) [31] | Nearly 100% of bacterial cells |

| Information Output | Viable, culturable count | Total abundance, membrane integrity |

| Sensitivity | Lower | Higher sensitivity for overall bioburden [2] |

| Primary Application | Routine compliance monitoring | Real-time process monitoring, outbreak investigation |

A 2025 study directly comparing HPC and FCM for dialysis water monitoring concluded that FCM offers higher sensitivity, potentially enabling earlier corrective actions and greater patient safety [2] [32]. However, the authors noted that established maximum allowable levels for dialysis water using FCM are still needed [2].

Comparison Among HPC Method Variants

Even within HPC methodologies, significant performance differences exist. A study on dental unit waterlines (DUWL) compared the SimPlate method (Method 9215E) to the R2A spread plate method (9215C). The SimPlate method consistently underestimated microbial levels compared to the R2A method, and the correlation between the two methods was poor [33]. This highlights that the choice of HPC variant itself is critical, and methods like the R2A spread plate are considered more appropriate for monitoring specialized water systems [33].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and a deep understanding of the methodological nuances, detailed protocols for key experiments cited are provided below.

Objective: To accurately determine the total heterotrophic bacterial colony count in purified water systems (e.g., dental unit water, endoscope rinse water).

Materials:

- Sterile sampling containers

- R2A agar plates

- Phosphate buffer solution for dilutions

- Membrane filtration system (for large volume samples)

- 0.45 μm membrane filters

- Incubator set to 17-23°C

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Aseptically collect water samples. For outlet sampling (e.g., dental three-in-one gun), let water run for 30 seconds before collecting at least 10 mL into a sterile container. For terminal rinse water, collect 200 mL.

- Sample Transport and Storage: Store samples at 1-4°C and analyze within 6 hours of collection.

- Sample Inoculation:

- For small volume samples (e.g., 1 mL): Use the pour plate or spread plate method. For the spread plate, spread 0.1-1.0 mL of the sample (or dilution) onto the surface of an R2A agar plate.

- For large volume samples (e.g., 100-200 mL): Use membrane filtration. Filter a known volume through a 0.45 μm membrane and aseptically place the filter onto the surface of an R2A agar plate.

- Incubation: Invert plates and incubate at 17-23°C for 7 days (168 hours).

- Enumeration: After incubation, count all colonies on the plate or membrane. Calculate the CFU per mL based on the sample volume and any dilution factors.

Objective: To rapidly quantify the total microbiological load in dialysis water for real-time monitoring.

Materials:

- Flow cytometer

- DNA staining dye (e.g., SYBR Green I with propidium iodide for intact cell count)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Sterile tubes

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect water samples from representative points in the water treatment system and distribution loop aseptically.

- Sample Staining: A fixed volume of the water sample is mixed with a precise volume of fluorescent DNA stain. The mixture is incubated in the dark for a specified period (e.g., 10-15 minutes).

- Instrument Calibration: The flow cytometer is calibrated using standard beads of known size and fluorescence.

- Sample Analysis: The stained sample is passed through the flow cytometer. As cells intercept a laser beam, they scatter light and emit fluorescence, which is detected by photomultiplier tubes.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: The triggered signals are processed by the software. Bacterial cells are discriminated from background noise based on their fluorescence and scatter signals. The total number of cells (or intact cells, depending on the stain) per mL is automatically calculated.

Visualization of Method Selection and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key decision-making pathway for selecting an appropriate microbial monitoring method based on the application's primary requirement.

Decision Pathway for Microbial Monitoring Methods

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for performing the microbial monitoring methods discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Microbial Monitoring

| Item | Function/Description | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| R2A Agar | Low-nutrient culture medium for recovering stressed and slow-growing bacteria from water. | Enumeration of heterotrophic bacteria in purified water, dialysis fluid, pharmaceutical water systems [20]. |

| Plate Count Agar (PCA) | High-nutrient general-purpose medium for viable bacterial counts. | Standard microbial limits testing in pharmaceuticals, food products, and general water quality assessment. |

| Membrane Filters (0.45 µm) | Sterile filters to concentrate bacteria from large liquid volumes for analysis. | HPC testing of large water samples (e.g., 100 mL) via membrane filtration method [29]. |

| SYBR Green I / PI Stain | Fluorescent nucleic acid stains used in flow cytometry to differentiate total and intact bacterial cells. | Rapid bioburden analysis of water via flow cytometry; SYBR Green stains all cells, PI penetrates compromised membranes [31]. |

| SimPlate for HPC | Ready-to-use multi-well plate with proprietary substrates; metabolism produces fluorescence. | Commercial, high-throughput testing for heterotrophic bacteria; results in 48 hours [33]. |

| Sterile Sampling Kits | Containers with sodium thiosulfate to neutralize residual chlorine in water samples. | Collection of water from treated systems (municipal, dental lines) to prevent continued disinfection during transport [33]. |

The selection of a microbial monitoring method is a critical decision that directly impacts patient safety, product quality, and research integrity in clinical, pharmaceutical, and scientific environments. Traditional HPC methods, particularly those using R2A agar, remain the gold standard for regulatory compliance where data on culturable bacteria is required. However, the emergence of rapid techniques like Flow Cytometry offers a powerful tool for real-time process monitoring and control, enabling proactive interventions. The choice ultimately depends on the specific application, the need for speed versus culturality, and the nature of the sample being tested. By understanding the strengths and limitations of each method, professionals can make informed decisions to ensure the highest standards of microbiological quality.

Troubleshooting HPC assays: Overcoming Low Recovery and Interpreting Complex Results