ANI vs dDDH: A Genomic Era Guide for Accurate Microbial Taxonomy and Strain Typing

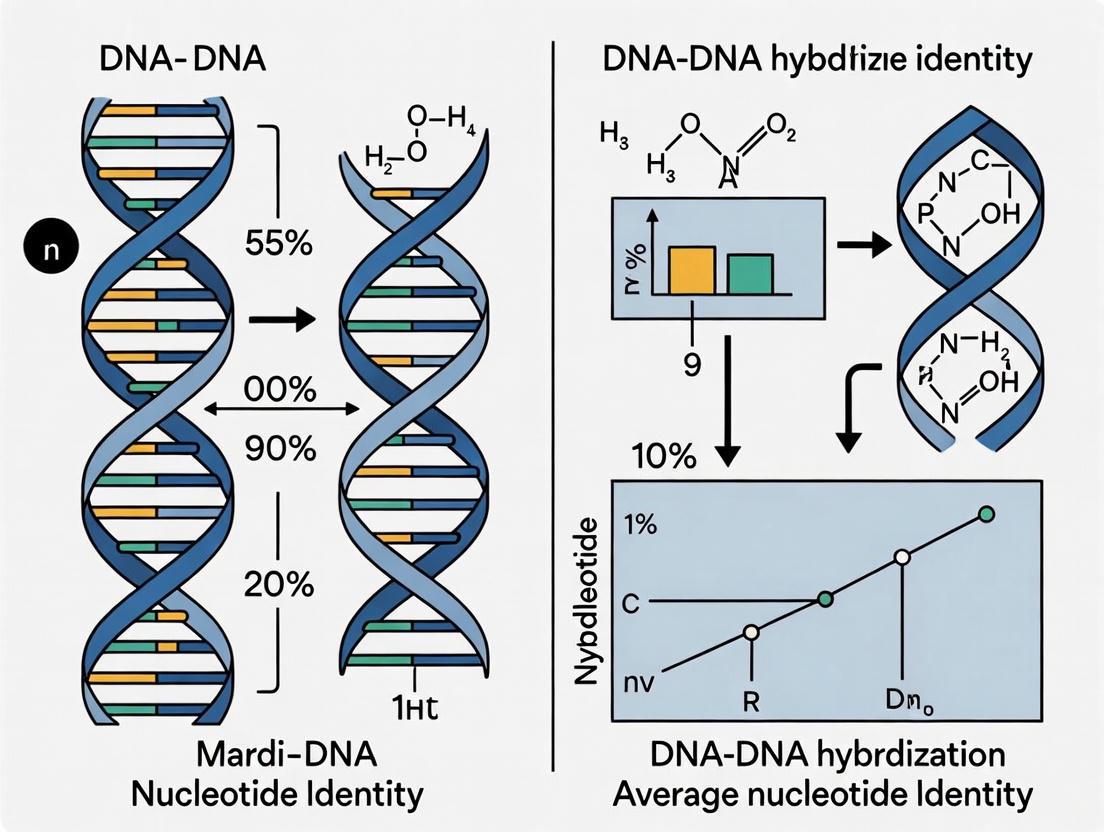

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH), two cornerstone genomic methods that have revolutionized prokaryotic species delineation and strain typing.

ANI vs dDDH: A Genomic Era Guide for Accurate Microbial Taxonomy and Strain Typing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH), two cornerstone genomic methods that have revolutionized prokaryotic species delineation and strain typing. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of these in-silico techniques, detail their calculation methodologies and applications in clinical and environmental microbiology, address critical troubleshooting aspects like threshold discrepancies and quality control, and present a comparative validation against traditional methods like MLST and phenotypic assays. By synthesizing the most current research, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to implement robust, genome-based taxonomic frameworks in their work, ultimately enhancing pathogen tracking, antibiotic resistance prediction, and microbial diversity studies.

Decoding the Genomic Alphabet: Foundational Principles of ANI and dDDH

For nearly 50 years, DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) served as the cornerstone technique for microbial species delineation, providing the pragmatic basis for the prokaryotic species concept [1] [2]. This wet-lab method measured the overall similarity between two microbial genomes through nucleic acid reassociation kinetics, with a established threshold of 70% similarity justifying the classification of strains as separate species [2]. Despite its foundational role, traditional DDH suffered from significant limitations: it was tedious, error-prone, difficult to reproduce across laboratories, and incapable of building cumulative comparative databases [3] [1] [2]. The advent of affordable whole-genome sequencing created an urgent need for computational methods that could replicate DDH measurements, leading to the development of digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) and Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) as transformative solutions [1] [2]. This evolution from wet lab to in-silico represents a paradigm shift in microbial taxonomy, offering unprecedented precision, reproducibility, and data reuse potential while maintaining continuity with established taxonomic standards.

Wet-Lab DDH: The Traditional Foundation

The traditional DDH protocol involved experimental measurement of DNA reassociation kinetics between closely related strains. The hydroxyapatite method, the most common among several variants, involved fragmenting DNA, denaturing double strands, and allowing complementary strands to reassociate [1]. The percentage of cross-hybridization between strains provided the similarity value, with the 70% threshold becoming universally accepted for species boundaries based on the work of an Ad Hoc Committee on Reconciliation of Approaches to Bacterial Systematics [1]. While this method enabled substantial standardization in prokaryotic taxonomy, its technical execution remained challenging. The procedure required significant DNA quantities, was sensitive to experimental conditions, produced results that varied between laboratories, and each data point represented a terminal measurement that couldn't be repurposed for future comparisons [2]. These inherent limitations created a bottleneck in microbial classification just as sequencing technologies began making genomic data increasingly accessible.

In-Silico Replacement: Digital DDH and ANI

Digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH)

The Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) emerged as the leading implementation for dDDH calculation, using high-scoring segment pairs (HSPs) or maximally unique matches (MUMs) to infer intergenomic distances [4] [2]. This method employs well-established similarity search tools like BLAST, BLAT, or MUMmer to identify homologous sequences between genomes, applies mathematical formulas to calculate distances from these matches, and finally converts these distances to percentage similarities analogous to traditional DDH values [2]. The GGDC approach demonstrates excellent correlation with wet-lab DDH while avoiding its inherent pitfalls, with some distance formulas showing remarkable robustness against incomplete genome sequences [4] [2]. The web server provides user-friendly access to this methodology, offering multiple distance formulas optimized for different scenarios, with Formula 2 recommended for its balanced error ratios at the critical 70% threshold [2].

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI)

The Average Nucleotide Identity method provides an alternative genome-based similarity measure by calculating the average nucleotide identity of orthologous genes shared between two genomes [5]. Initially, the 95-96% ANI threshold was established as equivalent to the 70% DDH standard for species demarcation [5] [6]. However, accumulating evidence from taxonomic studies across diverse bacterial genera indicates this relationship requires refinement. Research on Corynebacterium and Amycolatopsis has revealed that the corresponding ANI value for 70% dDDH may be approximately 96.67% OrthoANI for Corynebacterium and 96.6% ANIm for Amycolatopsis, suggesting genus-specific variations in these critical thresholds [6] [7]. This precision adjustment demonstrates how digital methods are refining rather than merely replacing traditional taxonomic boundaries.

Comparative Analysis: dDDH vs. ANI

Table 1: Comparison of Digital Methods for Microbial Taxonomy

| Feature | Digital DDH (GGDC) | Average Nucleotide Identity |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Input | Genome sequences | Genome sequences |

| Calculation Basis | High-scoring segment pairs (HSPs) or maximally unique matches (MUMs) | Orthologous nucleotide sequences |

| Standard Threshold | 70% for species delineation | 95-96% (with genus-specific variations) |

| Key Advantages | Higher correlation with wet-lab DDH; robust to incomplete genomes | Intuitive interpretation; direct evolutionary signal |

| Common Tools | GGDC web server | JSpeciesWS, OrthoANI |

| Typical Use Case | Official species description | Preliminary screening and species confirmation |

Both dDDH and ANI offer significant advantages over traditional methods, including objectivity, reproducibility, and incremental database building [1] [2]. While dDDH shows superior correlation with historical DDH data, ANI provides a more intuitive measure of genetic relatedness. In practice, modern microbial taxonomy often employs both methods complementarily to ensure robust species classification, as their orthogonal approaches provide mutual validation [6] [7].

Experimental Data and Threshold Refinements

Clinical Microbiology Applications

The transition to genome-based taxonomy has proven particularly valuable in clinical microbiology, where rapid and accurate pathogen identification is critical. A 2024 study evaluating Escherichia coli clinical isolates demonstrated that dDDH and ANI provided superior discriminative resolution compared to traditional multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) [5]. The research established optimized thresholds of 99.3% for ANI and 94.1% for dDDH for strain-level resolution in clinical isolates, notably higher than the standard species demarcation values [5]. This refinement highlights how application-specific thresholds can optimize the discriminatory power of these methods beyond basic species classification.

Genus-Specific Threshold Variations

Recent taxonomic investigations have revealed that the relationship between dDDH and ANI is not universal across bacterial genera, necessitating genus-specific threshold determinations:

Table 2: Genus-Specific Threshold Variations in Bacterial Taxonomy

| Bacterial Genus | Recommended ANI Threshold | Corresponding dDDH | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corynebacterium | 96.67% (OrthoANI) | 70% | Uterine isolates from camels [6] |

| Amycolatopsis | 96.6% (ANIm) | 70% | Rhizosphere soil isolates [7] |

| General/Historical | 95-96% | 70% | Early established correlation [5] [6] |

In the Corynebacterium study, researchers discovered that four uterine isolates from camels could not be reliably classified using the standard 95-96% ANI threshold, prompting a comprehensive re-evaluation that established the more appropriate 96.67% OrthoANI value for this genus [6]. Similarly, analysis of 29 pairs of Amycolatopsis type strains revealed that 70% dDDH corresponded to approximately 96.6% ANIm rather than the traditionally accepted 95-96% range [7]. These findings underscore the importance of genus-specific validation in microbial taxonomy and demonstrate how digital methods enable such precise calibrations through large-scale genomic comparisons.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Operating Procedure for dDDH Calculation

The GGDC methodology follows a standardized three-step process for calculating genome-to-genome distances [2]:

Similarity Search: Homologous regions between query and reference genomes are identified using nucleotide similarity search tools (BLAST, MUMmer, etc.). For optimal results with BLAST-based methods, "soft filtering" that applies filters only during the initial seed phase is recommended to prevent HSP fragmentation. Parameters should permit up to 100,000 HSPs to ensure comprehensive matching.

Distance Calculation: The identified HSPs or MUMs are processed using the Genome Blast Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) approach with specific distance formulas. Formula 2 (d5) is generally recommended for its balance of accuracy and robustness, particularly with incomplete genomes [2]. This formula must be used when working with draft genomes or incomplete sequences.

Conversion to Percentage Similarity: Calculated distances are converted to percentage similarities using the linear equation (s(d) = m \cdot d + c), where values for the slope (m) and intercept (c) are derived from robust linear fitting against reference DDH datasets [2].

ANI Calculation Workflow

ANI analysis typically follows this standardized protocol [6] [7]:

Genome Quality Assessment: Ensure all genomes meet quality thresholds (>95% completeness, <5% contamination) to guarantee reliable results.

Orthologous Identification: Identify orthologous regions between genomes using either BLAST-based (ANIb) or MUMmer-based (ANIm) approaches. ANIm is generally preferred when ANI values exceed 90% [7].

Identity Calculation: Calculate average nucleotide identity across all orthologous fragments, typically using tools like JSpeciesWS or the OrthoANI calculator.

Threshold Application: Apply appropriate genus-specific thresholds for species demarcation, using both dDDH and ANI complementarily for robust classification [6].

Diagram: The workflow from traditional DDH to modern genome-based classification methods, highlighting the parallel paths of dDDH and ANI calculation converging on taxonomic decisions.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Resources for Genome-Based Taxonomy

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGDC (Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator) | Web server | dDDH calculation using multiple formulas | https://ggdc.dsmz.de [4] [2] |

| TYGS (Type Strain Genome Server) | Web server | Genome-based prokaryote taxonomy with phylogenetic placement | https://ggdc.dsmz.de [4] |

| JSpeciesWS | Web service | ANI calculation using both BLAST and MUMmer approaches | Online service [7] |

| OrthoANI | Algorithm | ANI calculation based on orthologous gene identification | Implemented in various tools |

| NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline | Bioinformatics tool | Automated genome annotation for feature identification | NCBI resources [7] |

| antiSMASH | Bioinformatics tool | Secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene cluster identification | Web server [7] |

| MUMmer | Software package | Rapid genome alignment and ANI calculation | Open source [2] [7] |

This toolkit enables researchers to implement complete genome-based taxonomic workflows, from initial genome sequencing and annotation through comparative analysis and final species designation. The integration of these resources has democratized microbial taxonomy, making sophisticated genomic comparisons accessible to non-specialist laboratories while maintaining rigorous standards [4] [2] [7].

The evolution from wet-lab DDH to in-silico dDDH and ANI represents more than mere methodological convenience—it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how we conceptualize and deline microbial diversity. These digital approaches provide the foundation for a cumulative, reproducible, and data-rich taxonomic framework where every classification contributes to an expanding comparative database [2]. The discovery of genus-specific thresholds for ANI and dDDH correlations demonstrates how these methods are refining rather than merely replacing traditional taxonomic concepts [6] [7]. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and genomic databases expand, digital taxonomy will likely extend beyond species delineation to address broader questions about microbial evolution, functional adaptation, and ecosystem dynamics. The integration of these genomic metrics with phenotypic data through polyphasic approaches ensures that the rich history of microbial taxonomy will inform its genomic future, creating a more precise and comprehensive understanding of the microbial world.

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) represents a fundamental genomic metric for quantifying similarity between two bacterial or archaeal genomes at the nucleotide level. As an overall genome relatedness index (OGRI), ANI provides a robust, computational alternative to traditional wet-lab methods for prokaryotic species delineation and identification. The calculation of ANI yields values typically expressed as percentages, which reflect the proportion of nucleotide sequences in aligned genomic regions shared between two organisms. Research has established that approximately 95% ANI values correspond to the traditional 70% DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) threshold widely used for species demarcation in prokaryotic taxonomy [8]. This correlation has positioned ANI as a superior measure of genomic relatedness compared to data from individual genes, such as the 16S rRNA gene, because it incorporates information from hundreds to thousands of orthologous protein-coding genes distributed across the entire genome [8] [9].

The adoption of ANI has revolutionized microbial taxonomy by providing a standardized, reproducible approach that eliminates the technical variability associated with conventional DDH experiments. Unlike traditional methods that relied on laboratory hybridization measurements, ANI calculations can be performed computationally on sequenced genomes, enabling rapid, high-throughput classification of microorganisms. This transition to genome-based taxonomy has been particularly valuable for distinguishing closely related species that exhibit high similarity in 16S rRNA gene sequences but substantial genomic divergence [8] [10]. As whole-genome sequencing becomes increasingly accessible, ANI continues to solidify its role as an essential tool in modern bacteriology and microbiology research, with applications spanning clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and biotechnological development [8] [11].

Calculation Principles of ANI

The fundamental principle underlying ANI calculation involves comprehensive comparison of all shared genomic regions between two organisms and computation of the percentage of identical nucleotides relative to the total aligned nucleotides. This process typically employs either Whole Genome Alignment methods or more efficient programmed alignment algorithms to ensure both accuracy and computational efficiency. The standard ANI calculation workflow comprises four key stages: fragmentation, segment alignment, identity calculation, and average computation [8].

Core Calculation Workflow

The ANI calculation process begins with genome fragmentation, where both query genomes are divided into smaller fragments of specific length. For ANIb-based approaches, this typically involves creating 1,020-basepair fragments of the query genome, which are then compared to a reference genome using BLAST-based alignment [10]. Alternative methods like ANIm utilize the MUMmer alignment tool to compare entire contigs or genome sequences without prior fragmentation [10] [7]. Following fragmentation, the segment alignment phase identifies homologous regions between the two genomes through sophisticated sequence alignment algorithms.

The identity calculation step determines the similarity score for each aligned fragment pair by computing the percentage of identical nucleotides in the alignment. Finally, during average calculation, the individual similarity scores from all compared fragments are aggregated to produce a comprehensive ANI value. This value represents the mean nucleotide identity across all orthologous regions shared between the two genomes, providing a robust measure of overall genomic similarity [8].

Table: Key Steps in ANI Calculation

| Step | Process | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fragmentation | Division of genomes into smaller fragments | 1,020 bp fragments (ANIb), contigs (ANIm) |

| Segment Alignment | Identification of homologous regions | BLAST (ANIb), MUMmer (ANIm), USEARCH (OrthoANIu) |

| Identity Calculation | Determination of similarity for each aligned pair | Percentage of identical nucleotides in alignments |

| Average Calculation | Aggregation of individual similarity scores | Mean of all fragment identities |

Orthology Considerations

A significant advancement in ANI methodology came with the introduction of orthology-aware algorithms that specifically address the evolutionary relationships between compared genes. The original ANI implementation utilized BLAST to identify best hits of shared gene content between genomes, without explicitly considering orthology. This approach, known as ANIb, requires gene prediction on the assembly before ANI calculation can be performed [10]. The improved OrthoANI algorithm was developed specifically to accommodate the concept of orthology, potentially providing more biologically meaningful comparisons by focusing on genes with common evolutionary origins [12].

Core ANI Algorithms and Their Comparative Performance

Several computational algorithms have been developed to calculate ANI, each with distinct methodological approaches, performance characteristics, and applications in microbial taxonomy. The most widely used implementations include ANIb, ANIm, OrthoANIb, and OrthoANIu, which employ different alignment strategies and orthology considerations.

Algorithm Methodologies

ANIb represents the original BLAST-based ANI algorithm that fragments the query genome and uses BLAST to identify homologous regions in the reference genome. This method requires gene prediction before analysis and has been considered a benchmark in the field despite its computational intensity [12] [10]. ANIm utilizes the MUMmer ultra-rapid aligning tool to perform whole-genome comparisons without prior fragmentation or gene prediction, offering significant speed advantages while maintaining accuracy [10] [7].

OrthoANIb constitutes an enhanced version that incorporates orthology considerations while retaining BLAST as its search engine, potentially providing more biologically relevant comparisons. OrthoANIu represents a further optimization that employs the USEARCH program instead of BLAST, dramatically improving computational efficiency while preserving accuracy through orthology-aware comparisons [12]. A large-scale evaluation of these algorithms demonstrated that OrthoANIb and OrthoANIu exhibited excellent correlation with the standard ANIb across the entire range of ANI values, while ANIm showed poorer correlation particularly at ANI values below 90% [12].

Performance Comparison

Comparative studies have revealed substantial differences in computational efficiency among ANI algorithms. When analyzing genomes larger than 7 Mbp, both ANIm and OrthoANIu demonstrated dramatically faster run-times than ANIb—by 53-fold and 22-fold, respectively [12]. This performance advantage makes these algorithms particularly valuable for large-scale genomic studies involving hundreds or thousands of genome comparisons.

Table: Comparison of Major ANI Calculation Algorithms

| Algorithm | Alignment Method | Orthology Consideration | Speed | Accuracy Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANIb | BLAST | No | Slow (Reference) | Reference standard |

| ANIm | MUMmer | No | Very Fast (53× faster) | Poor below 90% ANI |

| OrthoANIb | BLAST | Yes | Slow | Excellent |

| OrthoANIu | USEARCH | Yes | Fast (22× faster) | Excellent |

The selection of an appropriate ANI algorithm depends on the specific research context. For routine taxonomic classification where computational efficiency is prioritized, OrthoANIu and ANIm offer compelling advantages. However, for precise species delineation near threshold values, particularly when analyzing genomes with ANI values below 90%, OrthoANIb or ANIb may provide more reliable results despite their computational demands [12].

Experimental Protocols for ANI Analysis

Implementing robust ANI analysis requires careful attention to experimental design, genome quality assessment, and computational procedures. The following protocols outline standardized approaches for conducting ANI comparisons in taxonomic studies.

Genome Quality Requirements

High-quality genome assemblies are prerequisite for reliable ANI calculations. Experimental protocols should enforce strict quality control metrics, including minimum sequencing coverage (typically 20-40× depending on the organism), Q score thresholds (minimum of 30), and assembly completeness assessments [10]. For taxonomic studies, genomes should demonstrate >95% completeness and <5% contamination based on tools like CheckM2 to ensure analytical reliability [13] [7]. DNA extraction methods must yield sufficient quantity and quality, with fragment size analysis confirming appropriate molecular weight for downstream analyses [11].

Computational Workflow

A standardized ANI computational workflow begins with genome preprocessing, including adapter trimming and quality filtering using tools like Fastp. Subsequent genome assembly can be performed using SPAdes for Illumina data or HGAP for PacBio data, followed by quality assessment [10]. For ANI calculation, the OrthoANIu algorithm implemented through the EZBiocloud web service (http://www.ezbiocloud.net/tools/ani) provides a user-friendly option with high accuracy and speed [12] [9]. Alternatively, researchers can implement standalone versions of various ANI algorithms for large-scale batch processing or integration into bioinformatics pipelines.

Workflow for ANI Analysis

ANI Thresholds for Species Delineation

The application of ANI in taxonomic classification relies on established threshold values that correlate with traditional species boundaries. While the widely accepted 95% ANI threshold corresponds to the conventional 70% DDH species demarcation line, recent evidence indicates that this relationship may vary across taxonomic groups and requires careful consideration in specific applications.

Standard and Group-Specific Thresholds

The conventional 95% ANI threshold for species delineation has been validated across numerous prokaryotic groups, providing a general standard for taxonomic classification [8]. However, studies of specific bacterial genera have revealed meaningful variations in optimal thresholds. Research on enteric bacteria demonstrated that while ≥95% ANI effectively classified Escherichia/Shigella and Vibrio species, lower thresholds of ≥93% for Salmonella and ≥92% for Campylobacter and Listeria provided more accurate species identification when using the ANIm method [10]. These findings highlight the importance of establishing group-specific thresholds, particularly for clinical identification where precision is critical.

Recent investigations in the genus Amycolatopsis have further challenged the universality of the 95% ANI threshold. Comparative genomic analysis of 29 pairs of Amycolatopsis type strains revealed that the 70% dDDH value corresponded to approximately 96.6% ANIm rather than the expected 95-96% [7]. This deviation underscores the necessity of considering genus-specific correlations between ANI and dDDH when describing novel taxa, as applying inappropriate thresholds could lead to either oversplitting or lumping of species.

Strain-Level Discrimination

Beyond species delineation, ANI has demonstrated utility for strain-level discrimination with appropriate threshold adjustments. A study evaluating E. coli clinical isolates established ANI and dDDH cut-offs of 99.3% and 94.1%, respectively, for discriminative strain resolution, potentially offering higher resolution than traditional multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) [11]. Similarly, research on Nonomuraea species and subspecies proposed dDDH values between 70% and 79% as indicative of different subspecies within the same species, while values above 79% suggest the same subspecies [14]. These refined thresholds enable precise strain typing valuable for epidemiological investigations and outbreak tracking.

Table: ANI and dDDH Thresholds for Different Taxonomic Levels

| Taxonomic Level | ANI Threshold | dDDH Threshold | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Same Species | ≥95% | ≥70% | General standard [8] |

| Same Species (Amycolatopsis) | ≥96.6% | ≥70% | Genus-specific threshold [7] |

| Same Subspecies | ~99% | ≥79% | Strain-level resolution [11] [14] |

| Different Subspecies | 95-99% | 70-79% | Infraspecific classification [14] |

Relationship Between ANI and Digital DNA-DNA Hybridization

The correlation between ANI and digital DDH (dDDH) represents a cornerstone of modern prokaryotic taxonomy, enabling the transition from experimental hybridization methods to computational genome-based classification. Understanding this relationship is essential for proper interpretation of genomic data and accurate species delineation.

Theoretical Basis and Correlation

The theoretical foundation linking ANI and DDH stems from their shared objective of quantifying overall genomic similarity. Traditional DDH measures the extent of DNA reassociation between two organisms under controlled laboratory conditions, while ANI computationally determines the percentage of identical nucleotides in aligned genomic regions. Extensive comparative analyses have established that the widely accepted 70% DDH threshold for species demarcation corresponds to approximately 95% ANI [8] [10]. This correlation has been validated across diverse bacterial groups, providing a robust framework for taxonomic classification.

The mathematical relationship between ANI and dDDH is generally linear in the critical range near species boundaries, but demonstrates variation across different taxonomic groups. As demonstrated in the Amycolatopsis study, the correlation between ANIm and dDDH values revealed that 70% dDDH corresponded to approximately 96.6% ANIm rather than the expected 95-96% [7]. Similarly, research on enteric bacteria showed that the ANI thresholds corresponding to 70% dDDH varied from 92% to 95% depending on the bacterial group [10]. These variations highlight the importance of considering taxonomic context when interpreting ANI-dDDH correlations.

Comparative Advantages in Taxonomic Studies

Both ANI and dDDH offer distinct advantages and limitations for taxonomic classification. The dDDH approach, implemented through the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC), provides direct comparability with historical DDH data and incorporates differences in genomic G+C content, which cannot exceed 1% within the same species [4] [7]. However, ANI methods generally offer superior computational efficiency, particularly with algorithms like OrthoANIu and ANIm, which can be orders of magnitude faster than dDDH calculation for large genomic datasets [12].

For contemporary taxonomy, a polyphasic approach incorporating both ANI and dDDH provides the most robust framework for species delineation. This integrated methodology leverages the computational efficiency of ANI for initial screening and the established taxonomic framework of dDDH for final classification decisions. Additionally, incorporating alternative genetic markers such as gyrB and recN genetic distances can provide supporting evidence for taxonomic decisions, particularly when genomic data is incomplete or unavailable [15].

Evolution of Genomic Relatedness Assessment Methods

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Implementing ANI analysis requires both laboratory reagents for genome preparation and computational tools for data analysis. The following resources represent essential components for conducting robust ANI studies.

Laboratory Reagents and Kits

High-quality genomic DNA extraction forms the foundation for reliable ANI analysis. The High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche Applied Science) provides a standardized method for obtaining sequencing-quality DNA from bacterial cultures [11]. For strains resistant to standard lysis protocols, supplementary reagents including lysozyme for Gram-positive bacteria, tissue lysis buffer, and proteinase K may be required for efficient cell disruption [11]. Quality assessment tools such as the Fragment Analyzer system enable verification of DNA fragment size and integrity prior to sequencing, ensuring library preparation compatibility [11].

Culture media selection depends on the target organisms, with specialized media such as chitin agar with antibiotics (nystatin, novobiocin, nalidixic acid) proving effective for isolating rare actinomycetes from environmental samples [13]. For routine cultivation, standard media including International Streptomyces Project 2 (ISP2) agar, tryptone soy agar (TSA), Luria-Bertani agar (LB), and Reasoner's 2A agar (R2A) support growth of diverse bacterial taxa [13] [7].

Several web services and standalone software packages provide accessible ANI calculation capabilities for researchers with varying bioinformatics expertise. The EZBiocloud ANI calculator (http://www.ezbiocloud.net/tools/ani) offers a user-friendly web interface for OrthoANIu computation, ideal for individual genome comparisons [12] [9]. For large-scale analyses or pipeline integration, standalone JAVA programs implementing OrthoANIu are available for download from the same platform [12].

The JSpeciesWS online service provides ANIm calculation capabilities and is particularly valuable when analyzing genomes with ANI values exceeding 90%, where ANIm demonstrates strong correlation with reference methods [7]. For dDDH calculations complementary to ANI analysis, the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) available through the Leibniz Institute DSMZ (https://ggdc.dsmz.de/) implements state-of-the-art methods with high correlation to wet-lab DDH results [4] [7].

Table: Essential Research Tools for ANI Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Resource | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit | Standardized DNA extraction [11] |

| Quality Assessment | Fragment Analyzer | DNA size and quality verification [11] |

| Specialized Media | Chitin agar with antibiotics | Isolation of rare actinomycetes [13] |

| Web Service | EZBiocloud ANI calculator | User-friendly OrthoANIu calculation [12] [9] |

| Standalone Software | OrthoANIu JAVA program | Large-scale batch processing [12] |

| Complementary Tool | GGDC (dDDH calculator) | Digital DDH calculation [4] [7] |

For decades, DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) served as the gold-standard technique for microbial species delineation, using the degree of genetic similarity between DNA sequences to determine the genetic distance between two organisms [16]. A 70% DDH value became the universally accepted threshold for defining a prokaryotic species [17] [18]. However, traditional DDH is a labor-intensive, time-consuming method fraught with technical challenges and reproducibility issues, making it unsuitable for building cumulative, comparable databases [17]. The advent of widespread whole-genome sequencing has catalyzed a paradigm shift, replacing this experimental mainstay with in-silico computational methods. Among these, digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) has emerged as a robust, reproducible, and accurate successor, overcoming the limitations of its wet-lab predecessor while providing a reliable genomic foundation for modern microbial taxonomy [17] [16].

dDDH and ANI: A Comparative Analysis of Genomic Metrics

While dDDH directly emulates the principles of laboratory DDH, Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) has developed in parallel as another powerful genome-based metric. ANI measures the average nucleotide identity of orthologous genes shared between two genomes [18]. Although both are used for species delineation, they offer different advantages and are often used in concert for robust taxonomic conclusions.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Genomic Delineation Methods

| Feature | Traditional DDH | Digital DDH (dDDH) | Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | DNA re-association and melting temperature [16] | Genome-to-genome sequence comparison using GBDP [17] | Mean identity of orthologous genomic regions [18] |

| Species Threshold | 70% [17] | 70% [17] | 95-96% [5] [18] |

| Data Output | Single similarity value | Single similarity value | Single identity value |

| Key Advantage | Established historical gold standard | High correlation with DDH; solves paralogy issues [16] | Intuitive interpretation; high correlation with DDH [18] |

| Primary Limitation | Tedious, low reproducibility, not cumulative [17] | Requires complete or draft genome sequences | Different algorithms (OrthoANI, FastANI) can yield varying results [19] |

The relationship between dDDH and ANI is well-established, with a 70% dDDH value corresponding to approximately 95-96% ANI [18]. However, this correlation can vary between taxonomic groups. A 2024 study on Amycolatopsis found that a 70% dDDH value corresponded more closely to an ANI of 96.6%, suggesting that genus-specific validation can be important for precise delineation [7].

Experimental Protocols: How dDDH and ANI are Calculated

The dDDH Methodology

The Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC), available as a web service, is a state-of-the-art platform for calculating dDDH values [4] [17]. Its core is the Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) method, which carefully filters out matches from paralogous sequences to ensure results reflect true genomic relatedness [16]. The general workflow involves:

- Whole-Genome Sequencing: Obtain high-quality genome sequences for the strains under investigation. A minimal sequencing coverage of 12x has been recommended to maintain essential genomic features and typing accuracy [5].

- Genome Preparation: Although complete genomes are ideal, draft genomes comprising distinct contigs can also be used successfully [17]. The GGDC method has been shown to be robust against partially incomplete genomic information [17].

- Digital Comparison via GBDP: The genome sequences are compared using a modified BLAST algorithm to identify High-Scoring Segment Pairs (HSPs) or alternatively, using MUMmer to find Maximally Unique Matches (MUMs) [17].

- Distance Calculation: The identities and lengths of the HSPs or MUMs are processed through a specific distance formula to compute the final dDDH value, which is a percentage mimicking the traditional DDH value [17].

The ANI Methodology

ANI calculation has several implementations, primarily differing in the alignment algorithm used:

- ANIb (BLAST-based): This method, implemented in the JSpecies software, fragments the query genome into consecutive 1020-nucleotide fragments to emulate the shearing of DNA in wet-lab DDH. These fragments are then aligned against the whole subject genome using BLASTN, and the average identity of all alignments is calculated [18].

- ANIm (MUMmer-based): This approach uses the MUMmer software package, which employs suffix trees to find anchors for alignment, offering faster computation speeds compared to BLAST-based methods [18].

- OrthoANI: An improved algorithm that incorporates the concept of orthology. It fragments both genomes and considers only orthologous fragment pairs for calculating nucleotide identities, ensuring symmetry in reciprocal comparisons and providing a more robust calculation for taxonomy [19].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for In-Silico Taxonomy

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Genomic Taxonomy |

|---|---|---|

| GGDC / TYGS | Web Server | High-throughput platform for calculating dDDH values and prokaryote taxonomy [4]. |

| JSpecies | Software Package | User-friendly tool for calculating ANI (both ANIb and ANIm) and comparing species boundaries [18]. |

| FastANI | Algorithm | Alignment-free tool for rapid ANI calculation, originally for bacteria but also applied to yeasts [20]. |

| OrthoANI | Algorithm & Software | Calculates ANI based on orthologous fragments, overcoming reciprocity issues [19]. |

| NCBI Genome Database | Data Repository | Source for downloading genome assemblies for reference and query strains [20]. |

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for using whole-genome sequencing and in-silico analyses for microbial species delineation, highlighting the roles of both dDDH and ANI:

Digital DDH has firmly established itself as the legitimate and superior successor to traditional DDH, providing a reproducible, high-resolution method for microbial species delineation in the genomic era. Its synergy with ANI calculations offers taxonomists a powerful, dual-faceted approach to classifying organisms. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and become more accessible, these in-silico methods will form the cornerstone of a more precise, scalable, and data-driven taxonomic framework. The transition from wet-lab gold standard to digital precision marks an irreversible and necessary evolution, enabling the construction of a cumulative and universally comparable understanding of microbial diversity.

The classification of prokaryotes has been fundamentally transformed by genome sequencing, moving from laborious laboratory procedures to precise computational methods. For decades, DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) served as the gold standard for species delineation, with a 70% similarity threshold widely accepted for defining a species [21]. However, this method was tedious, prone to experimental variation, and did not generate reusable data [21]. The advent of whole-genome sequencing enabled the development of digital alternatives, primarily Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and digital DDH (dDDH), which offer superior reproducibility and the ability to create cumulative databases [21] [22]. The 95% ANI threshold has become broadly correlated with the traditional 70% DDH value, establishing itself as a fundamental boundary in microbial taxonomy [22]. Nevertheless, recent research reveals that this relationship is not always precise, with significant implications for accurately classifying microorganisms in research and clinical settings.

Understanding the Core Metrics: ANI and dDDH

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI)

Average Nucleotide Identity is a bioinformatics metric that calculates the average nucleotide-level similarity between homologous regions of two genomes. It was developed as a robust, sequence-based alternative to wet-lab DDH [21]. Different algorithms can be used for its calculation:

- ANIm: Uses the MuMmer ultra-rapid aligning tool and is considered particularly reliable when comparing highly similar genomes (ANI >90%) [7] [23].

- ANIb: Based on the BLAST algorithm [23].

- OrthoANI: An improved method that may offer more accurate comparisons [6].

The 95-96% ANI range is widely recognized as the species boundary, meaning that two genomes sharing ≥95% ANI are likely members of the same species [24] [22].

Digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH)

Digital DNA-DNA Hybridization is a computational method designed to mimic the results of wet-lab DDH. The Genome Blast Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) approach is a highly reliable method for inferring genome-to-genome distances and calculating dDDH values [21]. This method uses local alignments between two genomes (high-scoring segment pairs) and transforms this information into a single distance value using specific distance formulas [21]. The well-established 70% dDDH threshold corresponds to the traditional DDH species boundary, allowing for consistent classification across methods [21] [22].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Prokaryotic Species Delineation

| Metric | Species Threshold | Calculation Method | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) | 95-96% | Bioinformatics comparison of homologous genome regions (e.g., ANIm, ANIb, OrthoANI) | Primary species delineation [22] |

| digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH) | 70% | Genome-to-genome distance calculation (e.g., GBDP) | Replication of wet-lab DDH standard [21] |

| 16S rRNA Gene Identity | 98.7% | Sequencing and alignment of the 16S rRNA gene | Preliminary screening [22] |

The Threshold Debate: A Universal Standard or a Genus-Specific Guideline?

While the 95% ANI and 70% dDDH correlation is a foundational concept in modern taxonomy, a growing body of evidence suggests that this relationship is not universal and requires refinement.

Evidence for a Universal Boundary

Large-scale genomic surveys consistently reveal that prokaryotic diversity is predominantly organized into sequence-discrete units. Analyses of thousands of genomes show a clear bimodal distribution of ANI values: a scarcity of genome pairs sharing 85-95% ANI, contrasted with abundant pairs showing >95% or <85% ANI [24] [25]. This "discontinuity" or "ANI gap" strongly suggests a natural genetic boundary between species [25]. Metagenomic studies of natural environments (marine, soil, human gut) further support this, showing that co-existing populations typically share >95% ANI within a population and <90% ANI between distinct populations [24] [25]. These sequence-discrete populations appear to be fundamental, persistent units of microbial communities [25].

Challenges and Refinements to the Universal Threshold

Despite the overarching pattern, significant exceptions and refinements exist:

Genus-Specific Threshold Variations: Recent studies have found that the 70% dDDH value does not always correspond precisely to 95-96% ANI. In the genus Amycolatopsis, a 70% dDDH value corresponds to approximately 96.6% ANIm [7]. Similarly, in Streptomyces, the equivalent ANI threshold is approximately 96.7% [23], and for Corynebacterium, 96.67% OrthoANI is proposed to better align with the 70% dDDH cutoff [6].

The Intra-Species ANI Gap: A groundbreaking study of 18,123 complete bacterial genomes revealed another discontinuity within species, between 99.2% and 99.8% ANI (midpoint 99.5%) [24]. This finer-scale gap provides a potential standard for defining intra-species units like clonal complexes with ~20% higher accuracy than previous methods [24]. Consequently, the proposal is that strains should be defined at ANI values >99.99% [24].

Technical and Ecological Considerations: The debate also involves technical considerations. Some argue that the observed ANI gap could be influenced by isolation biases, as available genome databases may over-represent closely related organisms [25]. However, the persistence of the pattern in metagenomic data, which is isolation-free, supports its biological reality, though rare intermediate genotypes do exist and may be ecologically significant [25].

Table 2: Refined ANI/dDDH Thresholds Across Bacterial Genera

| Bacterial Genus | Proposed Refined ANI Threshold | Equivalent dDDH Threshold | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amycolatopsis | 96.6% (ANIm) | 70% | Comparative genomic analysis of type strains [7] |

| Streptomyces | 96.7% (ANIm) | 70% | Correlation analysis of 80 species pairs [23] |

| Corynebacterium | 96.67% (OrthoANI) | 70% | Classification of uterine isolates from camels [6] |

| General (Intra-species) | 99.5% ANI | N/A | Delineation of sequence types/clonal complexes [24] |

Experimental Protocols for ANI and dDDH Analysis

Standard Workflow for Genome-Based Species Delineation

The following workflow outlines the key steps for researchers performing species classification using ANI and dDDH.

Detailed Methodological Considerations

1. Genome Sequencing and Assembly:

- DNA Extraction: Use standardized kits (e.g., High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit [5] or Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit [6]) to obtain high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA.

- Sequencing Platforms: Both Illumina (e.g., MiSeq, NovaSeq) [5] [6] and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (e.g., GridION, PromethION) [5] [7] platforms are widely used. For Nanopore sequencing, a minimum coverage of 12x is recommended to maintain typing accuracy [5].

- Assembly: Use assemblers like SPAdes [6] for de novo assembly. Assess assembly quality using metrics such as N50 and contig number, and validate with tools like GFinisher [26].

2. Calculation of ANI Values:

- Tools: The JSpeciesWS online service is a commonly used platform for calculating both ANIm and ANIb values [7] [23]. Alternatively, the OrthoANI calculator can be used [6].

- Protocol: Input the assembled genome (contigs or complete sequence) of the query strain and the genome sequence of the type strain(s) for comparison. The tool will output an ANI percentage. A value ≥95-96% typically indicates the same species, though genus-specific refinements should be considered [7] [23] [6].

3. Calculation of dDDH Values:

- Tools: The Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) is the standard tool, available online at http://ggdc.dsmz.de [5] [21].

- Protocol: Upload the genomes of the two organisms to be compared. The GGDC uses the GBDP method under the hood. It is crucial to use Formula 2 for the calculation, as it is optimized for species delineation and provides the closest correlation with wet-lab DDH values [7] [23] [21]. The result is a dDDH percentage, with values ≥70% supporting classification within the same species.

Table 3: Key Reagents, Tools, and Databases for Genomic Taxonomy

| Item Name | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| High Pure PCR Template Kit | Laboratory Reagent | Extraction of pure genomic DNA from bacterial cultures for sequencing [5]. |

| SPAdes Assembler | Bioinformatics Tool | De novo genome assembly from sequencing reads to reconstruct the complete genome [6]. |

| JSpeciesWS | Web Service | Calculation of Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) values between two genomes [7] [23]. |

| GGDC (Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator) | Web Service | Calculation of digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH) values using the GBDP method [21]. |

| FastQC | Bioinformatics Tool | Quality control assessment of raw sequencing data to ensure data integrity [6]. |

| Type Strain Genomes | Reference Data | Genomic sequences of nomenclatural types from databases like GenBank; essential as references for comparison [7] [22]. |

The establishment of the 95% ANI and 70% dDDH thresholds has provided the scientific community with powerful, reproducible standards for prokaryotic species delineation, moving beyond the limitations of traditional DDH. However, as genomic databases expand and analytical methods improve, it is evident that a single, universal genetic boundary is an oversimplification. The ongoing "Species Boundary Debate" is driving a more nuanced understanding, where genus-specific refinements to these thresholds and the discovery of finer-scale intra-species gaps are enhancing the resolution and accuracy of microbial classification. For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolving landscape underscores the importance of using a polyphasic approach—combining ANI, dDDH, and phylogenetic data—to make robust and reliable taxonomic determinations that are critical for tracking outbreaks, discovering new taxa, and understanding microbial function in clinical and environmental settings.

The Critical Role of Type Strains and Reference Genomes in Reliable Taxonomy

The accurate classification of microorganisms is a cornerstone of microbiology, with profound implications for clinical diagnostics, drug development, and ecological studies. For decades, microbial taxonomy relied heavily on labor-intensive techniques such as DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) to establish species boundaries. The advent of whole-genome sequencing has revolutionized this field, introducing digital methods like Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH) that provide superior reproducibility and resolution. These genomic tools, however, depend critically on the availability and quality of type strains and reference genomes to serve as standardized reference points for the entire taxonomic framework. Type strains—the permanently preserved reference specimens for a species name—provide the essential foundation upon which reliable and reproducible species delineation is built. This article examines the critical importance of these reference materials within the ongoing research discourse comparing dDDH and ANI methodologies, providing experimental data and analytical frameworks to guide researchers in selecting appropriate taxonomic demarcation criteria.

Understanding the Genomic Tools: ANI and dDDH

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) is a computational method that measures the average nucleotide-level similarity between homologous regions of two genomes. It typically provides a single percentage value reflecting genomic relatedness. Digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH) is an in silico emulation of the wet-lab DDH procedure, estimating the potential for DNA strands from two organisms to hybridize. The Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) is a widely used method for calculating dDDH values, often using BLAST+ alignments and genomic distance calculations that are then converted to estimated DDH values [27] [28].

These methods have largely replaced traditional DDH due to their reproducibility and the ability to build cumulative databases. However, their accuracy is fundamentally tied to the quality of the reference genomes used for comparison, underscoring the indispensable role of properly curated type strain genomes.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of ANI and dDDH

| Feature | Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) | Digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Calculates average nucleotide identity of aligned genomic regions | Computes in silico estimate of wet-lab DNA hybridization |

| Primary Output | Percentage value (0-100%) | Percentage value (0-100%) |

| Standard Species Threshold | 95-96% [7] [6] | 70% [7] [6] |

| Computational Basis | MUMmer or BLAST-based alignments [7] | Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) [27] [28] |

| Key Advantage | Intuitive interpretation as sequence similarity | Direct correlation with established wet-lab method |

Experimental Data: Comparative Performance of ANI and dDDH

Recent studies have generated substantial quantitative data comparing ANI and dDDH for species delineation, frequently revealing that the classical threshold correspondence requires refinement.

Threshold Variability Across Genera

A 2024 study on Corynebacterium isolates from camel uteri revealed that the conventional 95-96% ANI threshold did not correspond well with the 70% dDDH boundary. Through analysis of 150 type strain genomes, researchers proposed a refined OrthoANI cutoff of 96.67% to match the 70% dDDH value, highlighting genus-specific variations in threshold applicability [6] [29].

Similarly, research on Amycolatopsis species demonstrated that a 70% dDDH value corresponded to approximately 96.6% ANIm (ANI based on MUMmer), not the traditionally accepted 95-96% range. This finding emerged from comparative genomic analysis of 29 pairs of Amycolatopsis type strains and led to the identification of a novel species, Amycolatopsis cynarae sp. nov. [7].

High-Resolution Strain Typing

A 2024 study utilizing PromethION nanopore sequencing for Escherichia coli clinical isolates found that ANI and dDDH could achieve superior discriminative resolution compared to traditional Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST). The study established strain-level cutoffs of 99.3% for ANI and 94.1% for dDDH, which correlated well with MLST classifications while potentially offering higher resolution [11] [5] [30].

Table 2: Experimental ANI and dDDH Cutoffs from Recent Studies

| Study Organism | Research Context | Proposed ANI Cutoff | Proposed dDDH Cutoff | Correspondence to Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corynebacterium spp. [6] [29] | Species delineation of uterine isolates | 96.67% (OrthoANI) | 70% | Revised upward from 95-96% |

| Amycolatopsis spp. [7] | Novel species description | 96.6% (ANIm) | 70% | Revised upward from 95-96% |

| Escherichia coli [11] [5] | Strain-level typing | 99.3% | 94.1% | Far exceeds species thresholds |

The Essential Reference Framework: Type Strains and Reference Genomes

Type strains and their associated reference genomes provide the standardized, fixed reference points that enable the ANI and dDDH values discussed above to have taxonomic meaning.

The Problem of Incomplete Reference Databases

Despite their critical importance, reference databases suffer from significant gaps. A 2022 study reported that two-thirds of all species-level taxa in their analysis lacked a reference genome, with the representation gap being most pronounced in environmental samples such as soil (43-63% unrepresented) and animal-associated microbiomes (60-80% unrepresented) [31].

This substantial coverage gap means that a significant proportion of microbial diversity remains "invisible" to reference-dependent taxonomic profiling methods, potentially biasing abundance estimates of detected taxa [31].

Impact on Taxonomic Resolution

The limitations of single-gene approaches like 16S rRNA sequencing have become increasingly apparent. A comprehensive analysis of >1,000 Bacteroidetes type strain genomes demonstrated that classifications based heavily on 16S rRNA gene trees often resulted in non-monophyletic taxa requiring revision. The study revealed that phylogenomic approaches using whole-genome data provided significantly improved resolution and reliability for taxonomic decisions [32].

Experimental Protocols for Genomic Taxonomy

Protocol 1: dDDH Calculation Using GGDC

The Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) is a standardized method for dDDH calculation [27] [28]:

- Data Preparation: Obtain complete or draft genome sequences for both the query strain and the type strain(s) of closely related species.

- Sequence Comparison: Calculate genomic distances using BLAST+ local alignments. The GGDC method uses identities/HSP length (Formula 2) as the distance metric.

- Distance Conversion: Convert distance values to estimated DDH values and their associated confidence intervals using a generalized linear model.

- Interpretation: Compare the resulting dDDH value to the 70% species threshold. Values below 70% suggest the query represents a distinct species from the reference type strain.

Protocol 2: ANI Calculation Using MUMmer (ANIm)

For taxonomic studies, ANI based on MUMmer (ANIm) often provides more credible results than BLAST-based ANI when similarity exceeds 90% [7]:

- Genome Submission: Upload genome sequences in FASTA format to the JSpeciesWS online service or use standalone MUMmer tools.

- Alignment: The MUMmer algorithm identifies Maximally Unique Matches (MUMs) between the two genomes as alignment anchors.

- Identity Calculation: Calculate nucleotide identity across all aligned regions, generating an average identity value (ANIm).

- Threshold Application: Compare the ANIm value to appropriate taxonomic thresholds, noting that genus-specific variations may apply (e.g., 96.6% for Amycolatopsis versus 95-96% as a general guideline).

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Genomic Taxonomy

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application in Taxonomy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Databases | DSMZ Type Strain Database | Provides authenticated type strain sequences | Essential reference points for species demarcation |

| NCBI RefSeq | Curated collection of reference genomes | Source of high-quality genome sequences for comparison | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) [27] [28] | Calculates dDDH values from genome sequences | Standardized species delineation against type strains |

| JSpeciesWS [7] | Computes ANI values through web interface | User-friendly ANI calculation for taxonomic studies | |

| MUMmer [7] | Genome alignment and ANIm calculation | High-performance whole-genome comparison | |

| Sequencing Technologies | Nanopore PromethION [11] [7] | Long-read whole genome sequencing | Enables complete genome assembly for reference quality |

| Illumina NovaSeq [6] | Short-read high-throughput sequencing | Provides cost-effective draft genomes for comparison |

The integration of ANI and dDDH analyses represents a significant advancement in microbial taxonomy, offering unprecedented resolution for species delineation. However, the reliability of these genomic tools is fundamentally dependent on the quality and comprehensiveness of type strains and reference genomes. Experimental evidence consistently shows that while general thresholds provide useful guidelines, taxon-specific considerations are essential for accurate classification. The research community must therefore prioritize the expansion of reference genome databases, particularly for underrepresented environmental and animal-associated microbiomes, to fully realize the potential of genomic taxonomy. For researchers and drug development professionals, this emphasizes the critical importance of selecting appropriate reference strains and validated thresholds when establishing taxonomic relationships for novel isolates.

From Theory to Bench: Methodological Workflows and Diverse Applications

The pragmatic species concept for Bacteria and Archaea has historically relied on DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH), a wet-lab technique that estimates overall genomic similarity between strains but is notoriously tedious, error-prone, and difficult to standardize across laboratories [17]. The advent of accessible whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has catalyzed a shift toward in-silico methods, primarily Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH), which provide reproducible, absolute genomic comparisons that do not require repeated physical experiments with reference strains [17] [33]. ANI calculates the average nucleotide identity of orthologous genomic regions shared between two organisms, while dDDH uses genome-to-genome sequence comparison to mimic the legacy DDH technique [17] [5]. These methods have become the genomic gold standard for prokaryotic species delineation and are increasingly applied for high-resolution typing below the species level [5]. This guide provides a comprehensive workflow from sequencing to analysis, objectively comparing the performance of leading bioinformatics tools for ANI and dDDH calculation.

Core Computational Concepts: ANI and dDDH

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI)

ANI is a computational measure of nucleotide-level genomic similarity. Initially developed to emulate DDH, its definition has evolved and is often tied to specific software implementations [34]. Key methodological variations exist:

- Alignment-based ANI: Originally, ANI was calculated using BLAST to compare either protein-coding genes or 1,020-base fragments of one genome against another, averaging identity across aligned regions [34]. This fragment size corresponds to DNA fragments used in wet-lab DDH experiments.

- Whole-Genome Alignment (WGA): Methods like those in JSpecies use NUCmer (from the MUMmer package) to perform whole-genome alignment, with ANI computed as the fraction of matching bases in aligned regions [34].

- K-mer-based Approaches: To improve computational efficiency, tools like FastANI use k-mer sketching to estimate ANI, sacrificing some accuracy for dramatic speed improvements, especially with large datasets [34] [35].

A 95% ANI threshold is widely accepted as corresponding to the traditional 70% DDH species boundary [33]. However, for higher-resolution strain typing within a species, studies have proposed a 99.3% ANI cut-off [5].

Digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH)

The Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) implements dDDH as a state-of-the-art in-silico replacement for wet-lab DDH [17] [4]. Instead of mimicking the DDH procedure, GGDC calculates intergenomic distances using the Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) approach, which are then converted into DDH-like values [17] [4]. The method is designed to cope with challenges like genomic repeats and heavily reduced genomes [17]. The established dDDH threshold for species demarcation is 70%, though for intra-species strain discrimination, a threshold of 94.1% has been proposed [5].

Step-by-Step Workflow from Sequencing to Results

Wet-Lab Phase: Genome Sequencing

The initial phase involves obtaining high-quality genomic data. While any sequencing technology can be used, the workflow must ensure sufficient DNA quality and coverage.

- DNA Extraction: Use a standardized kit (e.g., High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit) to obtain high-molecular-weight DNA. Assess DNA concentration using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) and evaluate fragmentation with a Fragment Analyzer system [5].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: For prokaryotic whole-genome sequencing, optimized protocols exist for platforms like Oxford Nanopore's PromethION, which is suitable for multiplexing multiple bacterial genomes [5]. For viral genomes, targeted amplification—such as the optimized multisegment RT-PCR for Influenza A Virus—may be necessary before sequencing [36].

- Quality Control & Assembly: Process raw reads through quality filtering and error correction, then assemble into contigs or complete genomes. A minimum sequencing coverage of 12x has been shown to maintain essential genomic features and typing accuracy for downstream ANI/dDDH analysis [5].

Bioinformatics Phase: ANI/dDDH Calculation

The following diagram illustrates the core bioinformatics workflow for calculating ANI and dDDH, from raw genome sequences to final species classification.

Tool Selection and Execution

Researchers must select appropriate computational tools based on their accuracy and efficiency needs. The following table compares the primary tool categories.

Table 1: Comparison of ANI and dDDH Calculation Tools

| Tool Category | Example Tools | Methodology | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment-Based ANI | ANIb, OrthoANI, JSpecies [34] | Uses BLAST or MUMmer for whole-genome alignment. | High accuracy, considered a gold standard [34]. | Computationally expensive and slow for large datasets [34]. |

| K-mer-Based ANI | FastANI, Mash [34] [35] | Uses k-mer sketching for genome comparison. | Extremely fast, efficient for large-scale analyses [34] [35]. | Lower accuracy than alignment-based methods, especially for distant genomes [35]. |

| Hybrid & New Tools | Vclust (LZ-ANI) [35] | Combines k-mer pre-filtering with Lempel-Ziv parsing for alignment. | Superior accuracy and efficiency; ideal for large datasets like viromics [35]. | Performance may decrease with highly similar, large datasets [35]. |

| Digital DDH | GGDC [17] [4] | Uses Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny (GBDP). | Highest correlation with wet-lab DDH, robust to incomplete genomes [17] [4]. | Web service may have limitations for very high-throughput private analyses. |

To execute an analysis, researchers can use web servers or command-line tools. For instance, the GGDC web server provides a user-friendly interface for dDDH calculation, while tools like PyANI (for ANIb, ANIm, etc.) or Vclust are run locally, often requiring familiarity with a command-line environment [34] [4].

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Accuracy in Species Delineation

Studies have rigorously benchmarked in-silico methods against traditional techniques. A pivotal study established that a 70% wet-lab DDH threshold corresponds to approximately 95% ANI and 85% conserved genes [33]. In a clinical study on Escherichia coli, ANI and dDDH demonstrated excellent correlation with Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) and offered potentially higher discriminative resolution at cut-offs of 99.3% (ANI) and 94.1% (dDDH) for strain-level typing [5].

Benchmarking studies using standardized frameworks like EvANI have systematically evaluated ANI estimation algorithms. Results indicate that ANIb (BLAST-based) best captures evolutionary tree distance but is the least computationally efficient. K-mer-based approaches like Mash offer a favorable trade-off, being "extremely efficient" while maintaining "consistently strong accuracy" [34].

Computational Efficiency and Scalability

Efficiency is critical for large datasets. A 2025 benchmark of viral genome clustering tools revealed dramatic performance differences [35].

Table 2: Benchmarking of Genome Clustering Tools on Viral Genomes

| Tool | Methodology | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Relative Processing Speed | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vclust (LZ-ANI) | Alignment-based (Lempel-Ziv) | 0.3% | >40,000x faster than VIRIDIC | Prime tool for phage classification; balanced speed/accuracy [35]. |

| VIRIDIC | Alignment-based (BLAST) | 0.7% | 1x (Baseline) | High accuracy but impractically slow for large datasets [35]. |

| FastANI | K-mer sketching | 6.8% | >6x slower than Vclust | Fast but less accurate, lower agreement with official taxonomy [35]. |

| skani | Sparse approximate alignment | 21.2% | ~7x faster than Vclust (fastest mode) | Fastest in some modes, but substantially less accurate [35]. |

Vclust processed ~123 trillion contig pairs from the IMG/VR database (over 15 million sequences), demonstrating its capability for metagenomic-scale projects [35]. For bacterial genomes, the GGDC has also been shown to be robust, producing reliable distances even with draft genomes containing gaps [17].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and tools required to implement this workflow.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for WGS to ANI/dDDH Workflow

| Item | Function/Role | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | To obtain high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from bacterial cultures. | High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche) [5]. |

| Quantification Instrument | To accurately measure DNA concentration for library preparation. | Qubit Fluorometer with broad-range dsDNA assay (Thermo Fisher) [5]. |

| Sequencing Platform | To generate long-read sequence data for genome assembly. | Oxford Nanopore PromethION, suitable for prokaryotic WGS [5]. |

| ANI Calculation Software | To compute Average Nucleotide Identity between genomes. | PyANI (wrapper for ANIb/ANIm), FastANI, Vclust, JSpecies [34] [35]. |

| dDDH Calculation Service | To compute digital DNA-DNA Hybridization values. | GGDC (GBDP) web server [17] [4]. |

| Clustering Algorithm | To group genomes into species or strains based on ANI/dDDH matrices. | Integrated in Vclust (Clusty) or other tools [35]. |

The workflow from whole-genome sequencing to ANI and dDDH calculation represents a fundamental modernization of microbial taxonomy and typing. The experimental data clearly shows that in-silico methods are not merely replacements for but are improvements upon traditional techniques, offering superior reproducibility, resolution, and scalability [17] [5] [33]. While alignment-based methods like ANIb and GGDC currently offer the highest accuracy and correlation with established standards, newer tools like Vclust demonstrate that novel algorithms can dramatically increase computational speed without sacrificing precision, making large-scale pangenomic and viromic studies feasible [34] [35].

As sequencing costs continue to fall and datasets grow, the optimization of bioinformatics workflows will become increasingly critical for managing computational time and cost [37]. The future of this field lies in the development of even more efficient and accurate methods, potentially combining alignment and k-mer strategies, and extending these principles to amino-acid-based comparisons for functional evolutionary insights [35]. For now, ANI and dDDH stand as robust, genome-informed pillars for species delineation and strain typing in both research and clinical diagnostics.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has revolutionized clinical microbiology, moving beyond traditional species identification to enable high-resolution strain typing essential for outbreak detection and antimicrobial resistance surveillance. This guide compares the performance of two central genomic metrics—Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and digital DNA-DNA Hybridization (dDDH)—for distinguishing bacterial strains. We objectively evaluate their protocols, discriminatory power, and applicability in clinical and public health settings, providing a structured framework for researchers and laboratory professionals to implement these methods effectively.

The pragmatic species concept for Bacteria and Archaea has historically been based on wet-lab DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH), with values ≤70% indicating different species [17]. In the genomic era, this gold standard has been digitally replicated by dDDH, while ANI has emerged as a powerful, sequence-based alternative. While both metrics are firmly established for species delineation at accepted thresholds (95-96% for ANI and 70% for dDDH) [17] [7], their application for high-resolution strain typing within a species represents a paradigm shift in molecular epidemiology.

Strain-level analysis is critical as bacterial strains under the same species can exhibit different biological properties, including virulence, antibiotic resistance, and host adaptation [38]. Traditional typing methods like Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) rely on a small number of conserved housekeeping genes, offering limited resolution compared to whole-genome approaches [5] [39]. Advances in sequencing technologies, particularly long-read platforms like Oxford Nanopore's PromethION, have made WGS-based strain typing increasingly accessible for clinical laboratories [5]. This guide systematically evaluates ANI and dDDH as superior alternatives for outbreak investigation where distinguishing closely related strains is paramount.

Experimental Protocols for ANI and dDDH Analysis

Wet-Lab Workflow: From Bacterial Culture to Sequence Data

The initial stages of the protocol are critical for generating high-quality data:

- Culture Conditions: Clinical isolates are typically cultured for 24 hours on appropriate solid media such as tryptic soy agar plates with 5% sheep blood under aerobic conditions at 37°C [5].

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial kits like the High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche) with modifications for optimal bacterial lysis. This may include using tissue lysis buffer and proteinase K with stationary incubation at 55°C for 1 hour [5].

- DNA Quality Control: Assess DNA fragmentation using systems like the Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytical). Determine concentration using spectrophotometry (e.g., DeNovix DS-11+) and fluorometry (e.g., Qubit 4.0) [5].

- Whole-Genome Sequencing: Utilize either short-read (Illumina) or long-read (Oxford Nanopore PromethION or GridION) platforms. For nanopore sequencing, a minimal sequencing coverage of 12× is required to maintain essential genomic features and typing accuracy [5].

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ANI/dDDH Workflows

| Item | Function | Example Products/Methods |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA | High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche) |

| Culture Media | Optimal growth of bacterial isolates | Tryptic soy agar +5% sheep blood |

| Sequencing Platform | Whole-genome sequence generation | Illumina NovaSeq (short-read); Oxford Nanopore PromethION/GridION (long-read) |

| Quality Control Instruments | Assess DNA fragmentation and concentration | Fragment Analyzer System; DeNovix DS-11+; Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Calculate ANI and dDDH values | JSpeciesWS; Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) |

Bioinformatic Analysis: Calculating ANI and dDDH

Following sequencing and genome assembly, the following analytical steps are performed:

- ANI Calculation: Use the JSpeciesWS online service or similar tools. ANI can be calculated using the MuMmer ultra-rapid aligning tool (ANIm) or the BLAST algorithm (ANIb). ANIm is considered more credible when ANI values exceed 90% [7].

- dDDH Calculation: Utilize the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC), typically using Formula 2, which is optimized for incomplete genomes [7].

Performance Comparison: ANI vs. dDDH vs. Traditional Methods

Discriminatory Power in Strain Typing

Recent studies have established refined cutoffs for strain-level discrimination that are markedly higher than species-level boundaries.

Table 2: Established and Proposed Cutoff Values for Species and Strain Delineation

| Classification Level | ANI Cutoff (%) | dDDH Cutoff (%) | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species Delineation | 95-96 [7] [6] | 70 [17] [6] | Differentiating species within a genus |

| Strain Typing (E. coli) | 99.3 [5] | 94.1 [5] | High-resolution outbreak strain discrimination |

| Genomovar Definition (S. ruber) | 99.2-99.8 (Gap) [40] | - | Identifying sub-species populations in natural environments |

A 2024 study on Escherichia coli clinical isolates demonstrated that ANI and dDDH cutoffs of 99.3% and 94.1%, respectively, correlated well with MLST classifications and showed potentially higher discriminative resolution than MLST [5]. This superior resolution is critical during outbreaks, where minute genetic differences between closely related strains must be detected.

Furthermore, analysis of natural bacterial populations has revealed a bimodal distribution of ANI values, with a notably lower occurrence of values between 99.2% and 99.8%—creating a natural "gap" in the sequence space within a species [40]. This finding provides a potential statistical basis for defining sub-species clusters, or "genomovars," in epidemiological investigations.

Comparison with Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST)

MLST has been a workhorse for bacterial typing but suffers from inherent limitations. As it relies on only 7-10 housekeeping genes, which are more conserved than the rest of the genome, the overall similarity of genomes classified under the same Sequence Type (ST) can be misleading [5]. In contrast, ANI and dDDH assess genomic relatedness across the entire genome, capturing variation in both core and accessory genomes that MLST misses. This comprehensive view often provides epidemiologically meaningful insights that would otherwise go undetected.

Table 3: Method Comparison for Bacterial Strain Typing

| Method | Genetic Basis | Resolution | Speed & Cost | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLST | 7-10 housekeeping genes | Lower (relies on conserved genes) | Moderate (requires PCR & sequencing) | Does not reflect overall genome similarity [5] |

| PFGE | Whole-genome restriction patterns | Low to Moderate | Slow, labor-intensive | Poor reproducibility and portability [39] |

| ANI | Whole-genome alignment | High (uses entire genome) | Fast once WGS is obtained | Requires robust bioinformatic pipeline [5] |

| dDDH | In-silico genome-to-genome comparison | High (uses entire genome) | Fast once WGS is obtained | Dependent on algorithm and formula choice [17] |

Application in Outbreak Settings and Current Challenges

Integrating Strain Typing with Antibiotic Resistance Prediction

WGS-based strain typing protocols show promise for integrated antibiotic resistance prediction. For E. coli, resistance prediction based on WGS data showed high categorical agreement (≥93%) with Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) assays for antibiotics like amoxicillin, ceftazidime, amikacin, tobramycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole [5]. However, performance was suboptimal (68.8–81.3%) for other antibiotics including amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and ciprofloxacin [5]. This underscores both the potential and current limitations of using WGS for comprehensive resistance profiling in outbreak management.

Taxonomic Considerations and Genus-Specific Variations

A significant challenge in applying fixed ANI/dDDH thresholds is that the precise relationship between these values can vary across bacterial genera. For instance:

- In the genus Amycolatopsis, a 70% dDDH value corresponds to approximately a 96.6% ANIm value, not the typical 95-96% [7].

- A study on Corynebacterium proposed using a 96.67% OrthoANI value to equate to a 70% dDDH value for reliable taxonomy [6].