A Practical Guide to Sample Size Calculation for Microbiological Method Verification

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on determining appropriate sample sizes for the verification of microbiological methods.

A Practical Guide to Sample Size Calculation for Microbiological Method Verification

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on determining appropriate sample sizes for the verification of microbiological methods. Aligning with international standards like the ISO 16140 series, it bridges the gap between statistical principles and practical laboratory application. The content covers foundational concepts, step-by-step methodologies, strategies for troubleshooting common issues, and the final steps for validation and comparative analysis, empowering scientists to design robust and defensible verification studies.

Why Sample Size Matters: Foundational Concepts for Robust Method Verification

Distinguishing Method Validation from Verification in Microbiology

In clinical, pharmaceutical, and food safety microbiology laboratories, demonstrating the reliability of analytical methods is a fundamental requirement for regulatory compliance and data integrity. The terms "method validation" and "method verification" are often used interchangeably, but they describe distinct processes with different objectives, scopes, and applications. Understanding this distinction is critical for selecting the correct approach when implementing new microbiological tests and for ensuring that the data generated is scientifically sound and defensible.

Method validation is the comprehensive process of proving that an analytical procedure is fit for its intended purpose. It is an in-depth investigation conducted to establish the performance characteristics and limitations of a new method, typically during its development or when significantly modifying an existing one. In contrast, method verification is the process of providing objective evidence that a previously validated method performs as expected within a specific laboratory's environment, using its operators and equipment. Essentially, validation asks, "Does this method work in principle?" while verification asks, "Can our laboratory perform this method correctly?"

Core Conceptual Differences

The fundamental differences between method validation and verification can be understood through their definitions, objectives, and the contexts in which they are applied.

What is Method Validation?

Method validation is a documented process that proves an analytical method is acceptable for its intended use [1]. It is a rigorous exercise performed to demonstrate that the method is capable of delivering results at the required performance level for specific applications [2]. Validation is typically required in the following scenarios:

- Development of a new analytical method (a Laboratory Developed Test or LDT).

- When an existing FDA-cleared or approved method is modified in a way not specified as acceptable by the manufacturer (e.g., using different specimen types or altering test parameters like incubation times) [3].

- Transfer of a method between laboratories or instruments where its performance must be re-established [1].

What is Method Verification?

Method verification is the process of confirming that a previously validated method performs as expected under a specific laboratory's conditions [1]. It is a one-time study meant to demonstrate that a test performs in line with previously established performance characteristics when used exactly as intended by the manufacturer for unmodified FDA-approved or cleared tests [3]. Laboratories perform verification anytime they start using a new, standardized method to demonstrate they can achieve the performance characteristics claimed during the validation process [4] [5].

Table 1: High-Level Comparison of Validation and Verification

| Aspect | Method Validation | Method Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Core Question | Does this method work for its intended purpose? | Can our lab perform this validated method correctly? |

| Context | New methods, lab-developed tests, modified methods | Adopting unmodified, commercially available methods |

| Scope | Comprehensive assessment of all performance parameters | Limited assessment of key performance parameters |

| Performed By | Method developer (often a third party) [4] | End-user laboratory |

| Regulatory Focus | Establishes performance claims [1] | Demonstrates laboratory competency [1] |

Performance Parameters and Experimental Design

The experimental designs for validation and verification differ significantly in breadth and depth. Validation requires a full characterization of the method, while verification focuses on confirming a subset of key parameters in the user's specific environment.

Parameters for Method Validation

A complete method validation characterizes a wide array of performance metrics [2] [6]:

- Accuracy: Closeness of agreement between a measured value and the true value.

- Precision: The degree of agreement among individual test results when the procedure is applied repeatedly to multiple samplings (includes within-run, between-run, and operator variance) [3].

- Specificity: Ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of expected interferences like impurities or other matrix components.

- Detection Limit (LOD): The lowest amount of analyte that can be detected.

- Quantitation Limit (LOQ): The lowest amount of analyte that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy.

- Linearity: The ability to obtain results directly proportional to analyte concentration.

- Range: The interval between upper and lower analyte levels where suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity are demonstrated.

- Robustness: Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in procedural parameters.

Parameters for Method Verification

For verification of unmodified FDA-approved tests, laboratories are required to verify a more focused set of characteristics [3]:

- Accuracy: To confirm acceptable agreement of results between the new method and a comparative method.

- Precision: To confirm acceptable within-run, between-run, and operator variance.

- Reportable Range: To confirm the acceptable upper and lower limits of the test system.

- Reference Range: To confirm the normal result for the tested patient population.

Application Notes and Protocols

This section provides detailed, practical guidance for designing and executing method verification studies in a microbiological context, with a specific focus on sample size considerations.

Sample Size Determination for Verification Studies

The following table summarizes the typical sample size requirements for verifying key parameters of qualitative and semi-quantitative microbiological assays, as derived from CLIA standards and best practices [3].

Table 2: Sample Size Guidance for Verification of Qualitative/Semi-Quantitative Assays

| Performance Characteristic | Minimum Sample Number | Sample Type and Distribution | Statistical Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 20 isolates | Combination of positive and negative samples for qualitative assays; range from high to low values for semi-quantitative assays [3]. | (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100 |

| Precision | 2 positive and 2 negative, tested in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators [3] | Controls or de-identified clinical samples. If system is fully automated, user variance testing may not be needed. | (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100 |

| Reportable Range | 3 samples | Known positive samples for qualitative assays; samples near upper and lower cutoff values for semi-quantitative assays [3]. | Verification that results fall within the established reportable range. |

| Reference Range | 20 isolates | De-identified clinical or reference samples representing the laboratory's typical patient population [3]. | Verification that results align with the expected reference range. |

Experimental Protocol for a Microbiological Method Verification

This protocol outlines the steps for verifying a qualitative microbiological test, such as a PCR assay for a specific pathogen.

Objective: To verify that the laboratory can successfully implement a commercial, FDA-cleared PCR test for Listeria monocytogenes in environmental samples, achieving performance metrics consistent with the manufacturer's claims.

Scope: Applicable to the verification of accuracy, precision, reportable range, and reference range prior to the implementation of the new test for routine use.

Materials and Reagents:

- Commercial Test Kit: Includes all necessary reagents, primers, probes, and controls.

- Reference Materials: Known positive and negative control strains from a recognized culture collection (e.g., ATCC).

- Clinical Samples: De-identified residual environmental sponge samples, previously characterized using a validated method.

- Equipment: Real-time PCR instrument, DNA extraction system, microbiological incubator, and biosafety cabinet.

- Culture Media: Appropriate enrichment and plating media as specified by the test method.

Procedure:

- Verification of Accuracy:

- Obtain 20 well-characterized isolates or samples. This should include 10 positive samples (various Listeria species and other relevant bacteria to challenge specificity) and 10 negative samples.

- Test all samples using the new PCR method according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Compare the results to those obtained from the reference method or known characterization.

- Calculate the percent agreement. The result must meet or exceed the manufacturer's stated claims or a laboratory-defined minimum (e.g., ≥95%).

Verification of Precision:

- Select 2 positive and 2 negative samples (e.g., control strains or spiked samples).

- Two trained analysts will each test these samples in triplicate, over three non-consecutive days (total of 36 data points).

- Ensure runs include all required quality controls.

- Calculate the percent agreement for within-run, between-run, and between-analyst comparisons. Results should meet pre-defined acceptance criteria for consistency.

Verification of Reportable Range:

- Test a minimum of 3 samples with known concentrations near the assay's limit of detection to confirm the lower reportable limit.

- For the upper limit, test a high-titer positive sample to ensure the result is correctly reported as "detected" without inhibition.

- All results should fall within the "Detected" or "Not detected" parameters as expected.

Verification of Reference Range:

- Test 20 samples that are known to be negative for Listeria monocytogenes from the laboratory's typical environmental monitoring program.

- All 20 samples should be reported as "Not detected," confirming the manufacturer's stated reference range is applicable to the laboratory's patient (or sample) population.

Acceptance Criteria: All calculated performance characteristics (accuracy, precision) must meet or exceed the specifications provided in the test kit's package insert or the laboratory's pre-defined acceptance criteria based on CLIA director approval [3].

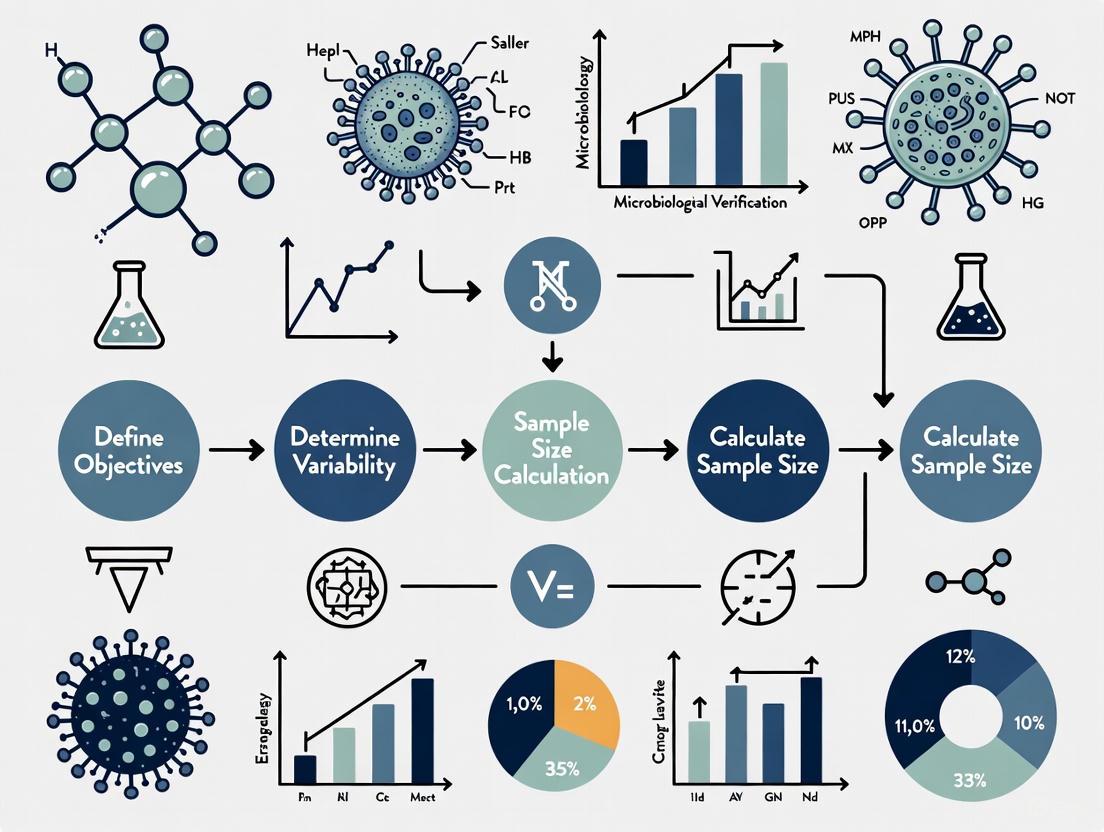

Workflow and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for determining whether a method requires validation or verification, and the key steps involved in the verification workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of method verification studies relies on high-quality, traceable materials. The following table lists essential reagents and their critical functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Microbiological Method Verification

| Reagent/Material | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Strains | Well-characterized microbial strains from collections like ATCC or NCTC. Used as positive controls and for spiking experiments to establish accuracy and precision. |

| Molecular Grade Water | Ultra-pure, nuclease-free water used in molecular assays (e.g., PCR) to prevent inhibition or degradation of sensitive reactions, ensuring robust and reproducible results. |

| Quality Control (QC) Strains | Strains with known reactivity patterns used in daily QC to monitor the consistent performance of the test system post-implementation. |

| Inhibitor Controls | Specifically designed controls (e.g., internal amplification controls in PCR) to detect the presence of substances in a sample that may interfere with the test, ensuring result validity. |

| Selective and Non-Selective Enrichment Media | Broths and agars used to cultivate target microorganisms from samples. Critical for ensuring the method's ability to recover stressed or low-level contaminants. |

In microbiological method verification research, robust statistical planning is the cornerstone of generating reliable, defensible, and scientifically valid data. Calculating an appropriate sample size is not merely a procedural step; it is a critical methodological decision that protects against both false positives and false negatives, ensuring efficient use of resources and upholding ethical standards in scientific research [7]. An underpowered study, due to an insufficient sample size, risks failing to detect true effects of a new microbiological method, potentially causing valuable innovations to be abandoned. Conversely, an excessively large sample size wastes resources, can cause ethical problems by involving more test materials than necessary, and delays the completion of research activities [7] [8].

This Application Note demystifies the triad of statistical concepts—Power, Confidence, and Effect Size—that govern sample size calculation. We frame these concepts specifically within the context of microbiological method verification and validation, guided by standards such as the ISO 16140 series [9]. The protocols and tools provided herein will enable researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to build statistically sound sampling plans that meet rigorous scientific and regulatory expectations.

Theoretical Foundations

Interrelated Concepts in Sample Size Estimation

The determination of sample size is governed by the interplay between several key statistical parameters. Understanding these relationships is crucial for designing a valid verification study. The core concepts include:

Type I Error (α) and Confidence Level: A Type I error (or false positive) occurs when the null hypothesis (H₀) is incorrectly rejected, meaning one concludes there is an effect or difference when none exists in the population [7] [8]. The probability of committing a Type I error is denoted by alpha (α). The Confidence Level, defined as (1-α), expresses the degree of certainty that the true population parameter lies within the calculated confidence interval. A standard α of 0.05 corresponds to a 95% confidence level, indicating a 5% risk of a false positive [7] [8].

Type II Error (β) and Statistical Power: A Type II error (or false negative) occurs when the null hypothesis is incorrectly retained, meaning a true effect or difference is missed [7] [8]. The probability of this error is beta (β). Statistical Power, defined as (1-β), is the probability that the test will correctly reject a false null hypothesis—that is, detect a true effect. The ideal power for a study is conventionally set at 0.8 (or 80%), meaning the study has an 80% chance of detecting an effect of a specified size if it truly exists [7] [8]. There is a delicate balance to be maintained between the risks of Type I and Type II errors.

Effect Size (ES): The Effect Size is a quantitative measure of the magnitude of a phenomenon or the strength of the relationship between two variables. In method verification, this could represent the minimum difference in detection capability between a new method and a reference method that is considered scientifically or clinically important [7]. Unlike the P-value, the ES is independent of sample size and provides a more practical indication of a finding's real-world significance. Larger effect sizes are easier to detect with smaller samples, while detecting small effect sizes requires larger sample sizes [7] [8].

P-Value: The P value is the obtained statistical probability of incorrectly accepting the alternate hypothesis. It is compared against the pre-defined alpha level to determine statistical significance. If the P value is at or lower than alpha, the alternative hypothesis (H₁) is accepted [7] [8].

The logical and mathematical relationships between these concepts, leading to sample size calculation, are visualized in the following workflow:

Error Types and Their Consequences in Microbiology

The concepts of Type I and Type II errors have direct, practical implications in a microbiology quality control setting. The following table summarizes these errors, their probabilities, and their real-world impact:

Table 1: Types of Statistical Errors in Microbiological Method Assessment

| Error Type | Statistical Description | Probability | Consequence in Microbiological Context | Example in Method Verification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I Error (False Positive) | Incorrectly rejecting a true null hypothesis (H₀) [7] [8] | α (Typically 0.05) [7] [8] | Concluding a new method is different from or superior to a reference method when it is not. | Adopting an alternative method that appears more sensitive but is not, leading to unnecessary cost and potential false failure rates. |

| Type II Error (False Negative) | Incorrectly failing to reject a false null hypothesis (H₀) [7] [8] | β (Often 0.20) [7] [8] | Concluding a new method is equivalent to a reference method when it is truly different or inferior. | Failing to identify a loss of detection capability in a new rapid method, potentially allowing contaminated products to be released. |

Practical Application & Experimental Protocols

Sample Size Calculation Formulas for Common Scenarios

The formulas for calculating sample size vary depending on the study design and the nature of the data. The table below summarizes key formulas relevant to microbiological method verification and related research.

Table 2: Sample Size Calculation Formulas for Common Research Methods [7] [8]

| Study Type | Formula | Variable Explanations |

|---|---|---|

| Comparison of Two Proportions (e.g., detection rates) | n = [p(1-p)(Z₁₋α/₂ + Z₁₋β)²] / (p₁ - p₂)² where p = (p₁ + p₂)/2 |

p₁, p₂: proportion of event of interest (e.g., detection) for group I and group II.Z₁₋α/₂: 1.96 for alpha 0.05.Z₁₋β: 0.84 for power 0.80. |

| Comparison of Two Means (e.g., colony counts) | n = [2σ² (Z₁₋α/₂ + Z₁₋β)²] / d² |

σ: pooled standard deviation from previous studies.d: clinically or technically meaningful difference between the means of 2 groups.Z values as above. |

| Validation of Sensitivity/Specificity | n = [Z₁₋α/₂² * P(1-P)] / d² |

P: expected sensitivity or specificity.d: allowable error (precision) for the estimate. |

For non-parametric tests or complex risk-based scenarios, such as those used in medical device packaging validation, a binomial reliability approach is often used. This method is suitable for qualitative (pass/fail) data and incorporates confidence and reliability levels derived from a risk assessment [10].

Table 3: Minimum Sample Sizes for Zero-Failure Binomial Reliability Testing [10]

| Confidence Level | Reliability Level | Minimum Sample Size (0 failures allowed) |

|---|---|---|

| 95% | 90% | 29 |

| 95% | 95% | 59 |

| 95% | 99% | 299 |

| 90% | 95% | 45 |

| 99% | 95% | 90 |

Protocol for Sample Size Determination in Method Verification

This protocol outlines the steps for determining a statistically justified sample size for the verification of a microbiological method, aligned with the principles of ISO 16140 [9].

Protocol Title: Sample Size Determination for Microbiological Method Verification Objective: To establish a statistically sound sample size plan that provides sufficient power to demonstrate the performance of a method relative to its validation claims or a reference method. Scope: Applicable to the verification of quantitative and qualitative microbiological methods in a single laboratory.

Materials and Reagents:

- Statistical Software: Tools such as G-Power, R, or other dedicated sample size calculators [7] [8].

- Pilot Data or Literature: Historical data, method validation reports, or published literature to inform variability (standard deviation) and expected effect size.

- Risk Assessment Matrix: A tool for assigning severity, occurrence, and detection ratings to justify confidence and reliability levels [10].

Procedure:

Define the Hypothesis and Objective:

- Clearly state the null hypothesis (H₀), e.g., "There is no difference in the detection rate between the new method and the reference method."

- State the alternative hypothesis (H₁), e.g., "The new method has a detection rate that is non-inferior to the reference method."

Select Statistical Parameters:

- Set the Significance Level (α): Typically 0.05 for a 95% confidence level [7] [8].

- Set the Statistical Power (1-β): Typically 0.80 or 80% [7] [8]. For higher-stakes verifications, a power of 0.90 may be chosen.

- Determine the Effect Size (ES): This is the most critical and often challenging step.

- For quantitative data (e.g., mean colony counts), the ES is the smallest difference (d) you need to detect, relative to the expected variability (σ). Use pilot data or a literature review to estimate σ.

- For qualitative data (e.g., presence/absence), the ES is the minimum difference in proportions (e.g., detection rates) that is considered microbiologically significant.

- If no prior data exists, use a conservative (larger) estimate for variability or consult a statistician.

Choose the Appropriate Statistical Test:

- Based on your objective and data type, select the test (e.g., comparison of two proportions, comparison of two means, reliability demonstration). Refer to Table 2 for corresponding formulas.

Calculate the Sample Size:

- Use the formula from Table 2 corresponding to your chosen test, inputting your selected α, power, and effect size.

- Alternatively, use statistical software, which often provides a more user-friendly interface for these calculations. For risk-based attribute data, use the zero-failure binomial sample sizes in Table 3 as a starting point, justified by a Risk Priority Number (RPN) [10].

Document and Justify:

- The final sample size and the complete rationale behind the chosen parameters (α, power, ES, and the source of variability estimates) must be documented in the study protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiological Method Verification

| Item | Function/Application in Verification Studies |

|---|---|

| Reference Strains | Well-characterized microorganisms from culture collections (e.g., ATCC) used as positive controls to ensure method performance and reproducibility [11]. |

| Facility Isolates | Environmental or process isolates representative of the actual microbial population in the production facility; used to challenge the method with relevant strains [11]. |

| Selective and Non-Selective Media | Used for the recovery and enumeration of challenge microorganisms; recovery must be demonstrated for the specific product category [11]. |

| Neutralizing Agents | Inactivates antimicrobial properties of the product or method to ensure accurate microbial recovery and prevent false negatives. |

| Statistically Justified Sample Size | The foundational "reagent" determined by this protocol; ensures the experimental data generated is reliable, reproducible, and scientifically defensible [7] [10]. |

Concluding Remarks

The rigorous application of statistical power, confidence, and effect size principles is non-negotiable in modern microbiological research and drug development. Moving beyond the arbitrary selection of sample sizes to a calculated, justified approach strengthens the validity of your method verification data, ensures regulatory compliance, and makes efficient use of valuable resources. By integrating these statistical tools into the experimental planning phase, as outlined in this document, scientists and researchers can produce higher-quality, more reliable data that truly demonstrates the fitness-for-purpose of their microbiological methods.

In microbiological research and drug development, the validity of any study hinges on the integrity of its sample size calculation. An incorrectly sized sample—whether too small or excessively large—undermines the entire scientific process, leading to either undetected hazards (false negatives) or significant resource waste. Within the framework of method verification and validation, establishing a sample plan is a foundational step that determines the power of a study to detect true effects and the reliability of its conclusions [12].

The core challenge lies in balancing vigilance with practicality. Inadequate sample sizes fail to capture the true microbial profile of a batch, allowing contaminated products to go undetected and posing serious risks to public health [12]. Conversely, excessively large samples strain time, personnel, and financial resources without a commensurate improvement in detection probability, making quality control processes unsustainable [12]. This application note details the consequences of incorrect sample sizing and provides structured protocols to empower researchers in designing defensible, efficient microbiological studies.

Quantitative Impact of Sample Size on Sampling Plan Performance

The performance of a microbiological sampling plan is mathematically described by its Operating Characteristic (OC) curve, which plots the probability of accepting a batch against the true proportion of defective samples [13]. The shape and accuracy of this curve are profoundly influenced by the chosen sample size.

The False Negative Problem: Undetected Contamination

A sampling plan with an insufficient sample size will have an OC curve shifted to the right, meaning the probability of accepting a batch remains high even when the contamination level is unacceptable [13]. This occurs because a small sample has a low probability of including contaminated units, especially when contamination is heterogeneous.

For example, if 1% of units in a batch are contaminated, a sample size of 299 units is required to have 95% confidence ((Prej = 0.95)) in detecting the problem [13]. A smaller sample size drastically reduces this detection probability. Furthermore, the sensitivity of the test method itself—the probability of correctly identifying a contaminated sample—exacerbates this issue. Low sensitivity increases false negatives, further shifting the OC curve to the right and reducing the probability of batch rejection [13].

Table 1: Sample Sizes Needed for 95% Confidence in Detecting Contamination

| Contamination Rate (Pdef) | Required Sample Size (n) | Calculation (Approx. 3/Pdef) |

|---|---|---|

| 1% (1 in 100) | 299 | 300 |

| 5% (1 in 20) | 59 | 60 |

| 10% (1 in 10) | 29 | 30 |

The Resource Waste Problem: False Positives and Economic Cost

While less dangerous than false negatives, false positives generated by poor sampling plans lead to significant resource waste. A low specificity (the probability of correctly identifying a non-contaminated sample) means actual negative samples are tested positive [13]. This moves the OC curve to the left, increasing the rejection rate of batches that are, in fact, acceptable [13].

The economic impact is multifaceted:

- Wasted Product: Rejection of safe batches results in direct financial loss.

- Unnecessary Labor: Time and effort are invested in follow-up testing, root-cause analysis, and disposal procedures.

- Operational Disruption: Production schedules are halted unnecessarily.

The effect of specificity is particularly severe in sampling plans with larger sample sizes, where it "should be much larger than 0.99 to have a reasonable performance" [13]. This highlights the critical interplay between statistical power and analytical method quality.

Consequences of Incorrect Sample Sizes

Scientific and Safety Consequences

- Inaccurate Method Validation: Method verification and validation require a clear understanding of a method's performance characteristics (specificity, sensitivity, reproducibility) [14] [9]. An incorrect sample size during validation jeopardizes this understanding, leading to the implementation of a method whose true limitations are unknown.

- Undetected Microbial Hazards: As shown in Table 1, small samples cannot reliably detect low-prevalence pathogens. This is catastrophic in drug development and food safety, where virulent pathogens pose a direct threat to consumer health [12] [13].

- Erosion of Scientific Credibility: Results from an underpowered study are not defensible to the scientific, regulatory, or legal communities [14]. In microbial forensics, this can "seriously impact the course or focus of an investigation, thus affecting the liberties of individuals" [14].

Operational and Resource Consequences

- Inefficient Resource Allocation: Oversampling consumes materials, reagents, and analyst time that could be deployed more effectively elsewhere in the R&D pipeline [12].

- Increased Cost of Quality Control: The direct costs of consumables and indirect costs of personnel time skyrocket with excessively large routine sampling plans, making the quality control process inefficient and unsustainable [12].

Protocols for Determining Sample Size in Method Verification

A robust, risk-based approach is essential for determining the correct sample size. The following protocol aligns with principles from international standards [9] and applied microbiology [12].

Protocol 1: Risk-Based Sample Plan Development

Objective: To establish a sampling plan frequency and size based on a scientific assessment of risk. Applications: Environmental monitoring, raw material testing, finished product release testing.

Conduct a Risk Assessment:

- Identify critical control points and potential microbial hazards in the process [12].

- Consider factors such as the susceptibility of ingredients to contamination, complexity of processing steps, and historical data from past contamination incidents [12].

- Example: In a vegetable factory, leafy greens are higher risk due to raw consumption and exposure to soil, warranting a more intensive sample plan [12].

Define the Scope and Objectives:

- Clearly state the purpose of testing (e.g., detection of a specific pathogen, enumeration of a spoilage organism).

- Define the statistical confidence required (e.g., 95% confidence) and the level of contamination that must be detected [13].

Determine Sampling Frequency and Size:

- Use the risk assessment to set frequencies. High-risk areas (e.g., raw material intake) require more frequent sampling than lower-risk areas (e.g., finished product storage) [12].

- Employ statistical techniques (e.g., random sampling, stratified sampling) to determine a sample size that accurately represents the batch and can detect the target contamination level with the required confidence [12]. Refer to formulas such as ( n = \frac{log(0.05)}{log(1-Pdef)} ) for qualitative testing [13].

Select and Validate Methodology:

The following workflow visualizes this risk-based protocol:

Protocol 2: Verification of Sample Plan Effectiveness

Objective: To verify that an implemented sampling plan performs as expected, particularly concerning the impact of method sensitivity and specificity. Applications: Verification of any new or revised sampling plan before full implementation.

Model the OC Curve:

- Using the formula ( P{accept} = (1 - P{def})^n ) for perfect tests, model the ideal OC curve for your sample size (n) and a range of defect rates (Pdef) [13].

- This represents the best-case performance.

Adjust for Method Imperfection:

- Calculate the practical probability of detection ((P{det})) that accounts for test method performance: ( P{det} = sens \times P{def} + (1 - spec) \times (1 - P{def}) ) [13], where

sensis sensitivity andspecis specificity. - Model the actual OC curve using this adjusted (P_{det}) value.

- Calculate the practical probability of detection ((P{det})) that accounts for test method performance: ( P{det} = sens \times P{def} + (1 - spec) \times (1 - P{def}) ) [13], where

Compare and Interpret Curves:

- A significant left-shift in the OC curve (lower acceptance) indicates false positives are likely due to low specificity, which will waste resources [13].

- A significant right-shift (higher acceptance) indicates false negatives are likely due to low sensitivity, which creates safety risks [13].

- Use this analysis to refine the sample size or select a more accurate test method.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for executing microbiological sampling and analysis as part of a verified method.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiological Sampling

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Selective & Non-selective Media | Supports the growth of target microorganisms while inhibiting non-targets. Essential for detection and enumeration. | Must be validated for the specific food matrix and target microbe to ensure recovery [12]. |

| Enrichment Broths | Amplifies low numbers of target pathogens to detectable levels. | Composition and incubation conditions are critical for sensitivity and must be optimized [15]. |

| Molecular Detection Reagents (e.g., PCR mixes, primers, probes) | Provides high specificity and sensitivity for confirming the identity of microorganisms [9]. | Requires rigorous validation of inclusivity and exclusivity to avoid false positives/negatives [9]. |

| Sample Diluents & Neutralizers | Prepares the sample for analysis and neutralizes residual antimicrobial agents or inhibitors present in the sample matrix. | Vital for obtaining representative and reliable results by ensuring microbial recovery is not biased [12]. |

| Reference Strains & Controls | Serves as positive and negative controls for validating method performance (specificity, sensitivity) during verification [14] [9]. | Use of certified reference materials is necessary for defensible and accurate verification. |

Determining the correct sample size is a critical, non-negotiable component of microbiological method verification. It is a balancing act that demands a scientific, risk-based approach. Under-sizing samples leads to a dangerous inability to detect contaminants, compromising product safety and public health. Over-sizing leads to unsustainable inefficiencies and wasted resources without a meaningful improvement in safety. By employing the structured protocols and understanding the quantitative relationships outlined in this document, researchers and drug development professionals can design defensible sampling plans that are both effective and efficient, thereby ensuring the reliability of their methods and the safety of their products.

The ISO 16140 series of International Standards provides standardized protocols for the validation and verification of microbiological methods in the food and feed chain. This series is essential for testing laboratories, test kit manufacturers, competent authorities, and food business operators to ensure that the methods they implement are fit for purpose and reliably performed within their facilities [9]. Understanding this framework is particularly crucial for research on sample size calculation, as the series defines specific requirements for the number of samples, food categories, and replicates needed for statistically sound method verification and validation studies.

The series has been developed to address the need for a common validation protocol for alternative (often proprietary) methods, providing a basis for their certification and enabling informed choices about their implementation [9]. The standards under the ISO 16140 umbrella each address distinct aspects of the method approval process, creating a comprehensive ecosystem for assuring microbiological data quality.

The ISO 16140 series is structured into several parts, each focusing on a specific validation or verification scenario. Table 1 summarizes the scope and application of each part.

Table 1: Parts of the ISO 16140 Series on Microbiology of the Food Chain - Method Validation

| Standard Part | Title | Scope and Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 16140-1 | Vocabulary | Defines terms used throughout the series [9]. |

| ISO 16140-2 | Protocol for the validation of alternative (proprietary) methods against a reference method | The base standard for validating alternative methods, involving a method comparison study and an interlaboratory study [9]. |

| ISO 16140-3 | Protocol for the verification of reference methods and validated alternative methods in a single laboratory | Describes how a laboratory demonstrates its competence in performing a previously validated method [9] [16]. |

| ISO 16140-4 | Protocol for method validation in a single laboratory | Addresses validation studies conducted within a single lab, the results of which are not transferred to other labs [9]. |

| ISO 16140-5 | Protocol for factorial interlaboratory validation for non-proprietary methods | Used for non-proprietary methods requiring rapid validation or when a full interlaboratory study isn't feasible [9]. |

| ISO 16140-6 | Protocol for the validation of alternative (proprietary) methods for microbiological confirmation and typing procedures | Validates methods for confirming presumptive results or for typing strains (e.g., serotyping) [9]. |

| ISO 16140-7 | Protocol for the validation of identification methods of microorganisms | Validates methods for identifying microorganisms (e.g., using PCR or mass spectrometry) where no reference method exists [9]. |

The relationships between these standards, especially when moving from method validation to routine laboratory use, can be visualized in the following workflow. This is critical for understanding where sample size calculations apply in the method lifecycle.

Distinction Between Method Validation and Verification

A fundamental concept within the ISO 16140 framework is the clear distinction between method validation and method verification. These are two sequential stages required before a method can be used routinely in a laboratory [9].

Method Validation is the first stage, which proves that a method is fit for its intended purpose. It characterizes the method's performance against defined criteria, such as its detection limit, accuracy, and specificity. As shown in the diagram, validation can follow different pathways (e.g., ISO 16140-2, -4, -5, -7) depending on the method type and scope of application. For instance, ISO 16140-2 involves an extensive interlaboratory study to generate performance data that is recognized broadly [9]. This stage is typically conducted by method developers or independent validation bodies.

Method Verification is the second stage, where a laboratory demonstrates that it can competently perform a method that has already been validated. It answers the question: "Can we achieve the performance characteristics claimed in the validation study in our lab, with our personnel and equipment?" [9] [16]. This process, detailed in ISO 16140-3, is a requirement for laboratories accredited to ISO/IEC 17025 and is considered a best practice for all testing facilities [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Method Verification (ISO 16140-3)

For researchers designing verification studies, ISO 16140-3:2021 outlines a structured two-stage process for laboratories to verify a method they intend to implement.

Two-Stage Verification Process

The verification process under ISO 16140-3 is divided into two distinct stages:

Implementation Verification: The purpose is to demonstrate that the user laboratory can perform the method correctly. This is achieved by testing a food item that was already used in the original validation study and showing that the laboratory can obtain comparable results. This confirms that the laboratory's execution of the method is fundamentally sound [9].

Food Item Verification: The purpose is to demonstrate that the method performs satisfactorily for the specific, and potentially challenging, food items that the laboratory tests routinely. This is done by testing several such food items and confirming that the method's performance meets defined characteristics for them [9].

Sample and Food Category Considerations

A critical aspect of designing a verification study is the selection of food categories and items, which directly impacts sample size calculations. The validation of a method often covers a defined scope of food categories.

ISO 16140-2 defines a list of food categories (e.g., heat-processed milk and dairy products). A method validated using a minimum of five different food categories is considered validated for a "broad range of foods," which covers 15 defined categories [9]. This concept is vital for scoping verification work. When a laboratory conducts a verification study, it must select food items that fall within the method's validated scope and are also relevant to the laboratory's own testing needs [9].

Table 2: Key Concepts for Sample Planning in Verification and Validation

| Concept | Description | Implication for Sample Size |

|---|---|---|

| Food Category | A group of sample types of the same origin (e.g., heat-processed milk and dairy products) [9]. | Validation studies often use 5 categories to represent a "broad range" of foods [9]. |

| Food Item | A specific product within a food category (e.g., UHT milk within the "heat-processed milk" category). | Verification requires testing specific items relevant to the lab's scope [9]. |

| Implementation Verification | Testing a food item used in the original validation study [9]. | Requires at least one food item. |

| Food Item Verification | Testing challenging food items from the lab's own scope [9]. | Requires several food items; specific numbers are defined in the standard. |

| Inoculum Level | The number of microorganisms introduced into a test sample. | Low-level inoculation (e.g., near the method's detection limit) is often used to challenge the method [11]. |

Regarding low-level inocula, it is important to note that microbial distribution at low concentrations follows a Poisson distribution rather than a normal distribution. This means that with a target of, for example, 10 CFU, there is a significant probability that an individual aliquot may contain more or fewer cells than intended. This variability must be accounted for in the experimental design, potentially by increasing replicate numbers [11] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The successful execution of methods under the ISO 16140 framework requires specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details essential components for microbiological method verification and validation studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiological Method Testing

| Reagent / Material | Function and Importance in Validation/Verification |

|---|---|

| Reference Method Materials | Materials specified by the standardized reference method (e.g., ISO 6579-1 for Salmonella). Serves as the benchmark against which an alternative method is validated [18]. |

| Alternative Method Kits | Proprietary test kits (e.g., iQ-Check EB, Petrifilm BC Count Plate). The object of the validation study to prove performance equivalence or superiority [18]. |

| Culture Media | Used for cultivation of microorganisms. Must be validated to support growth of fastidious organisms; factors like pH, ionic strength, and nutrient composition are critical. Handling (e.g., reheating) must be standardized [17]. |

| Reference Strains | Well-characterized strains from culture collections (e.g., ATCC). Used as indicator organisms to demonstrate a medium's ability to support growth and to challenge the method's detection capability [11] [17]. |

| Facility Isolates | Microbial strains isolated from the local manufacturing or testing environment. Should be included in verification studies to ensure the method detects relevant contaminants [17]. |

| Selective Agars | Agar media used for the isolation and confirmation of specific microorganisms. Validation of confirmation methods (ISO 16140-6) is tied to the specific agars used in the study [9]. |

| Inactivation Agents | Used to neutralize inhibitory substances in a sample (e.g., antimicrobial residues). Their performance must be validated to ensure they do not harm target microorganisms and effectively neutralize inhibitors [17]. |

Defining the scope of a microbiological method verification study is a critical first step that directly influences the experimental design, sample size calculations, and ultimate validity of the research findings. This document establishes frameworks for selecting appropriate food categories and target microorganisms, ensuring verification studies are conducted with scientific rigor and regulatory compliance. The principles outlined here are framed within the context of microbiological method verification as defined in the ISO 16140 series, which provides standardized protocols for laboratories validating alternative methods against reference methods [9].

The scope of validation directly informs verification activities in a laboratory. When a method has been validated for a "broad range of foods" (typically across 15 defined food categories using a minimum of 5 categories during validation), it is expected to perform reliably across all similar matrices within those categories [9]. Understanding this relationship between validation scope and verification requirements is essential for designing efficient yet comprehensive verification studies with appropriate sample sizes.

Food Categorization Framework

ISO 16140 Food Categories

The ISO 16140-2 standard defines 15 primary categories of food and feed samples that form the basis for validation and verification studies [9]. These categories group sample types of similar origin and characteristics, providing a systematic framework for method evaluation. When a method is validated using a minimum of 5 different food categories, it is considered validated for a "broad range of foods" encompassing all 15 categories [9].

Table 1: ISO 16140 Food Categories for Method Validation and Verification

| Category Number | Description | Example Matrices |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Meat and meat products | Raw meats, cured meats, paté |

| 2 | Fish and fish products | Fresh fish, shellfish, smoked fish |

| 3 | Fruits and vegetables | Fresh produce, salads, juices |

| 4 | Egg and egg products | Whole eggs, powdered eggs, egg-based products |

| 5 | Milk and milk products | Raw milk, cheese, yogurt, butter |

| 6 | Cereals and cereal products | Flour, bread, pasta, breakfast cereals |

| 7 | Confectionery | Chocolate, candies, chewing gum |

| 8 | Nuts, nut products, and seeds | Whole nuts, nut butters, sunflower seeds |

| 9 | Sugars and sugar products | Honey, syrups, molasses |

| 10 | Fermented foods and beverages | Beer, wine, sauerkraut, tempeh |

| 11 | Spices and seasonings | Dried herbs, spice blends, condiments |

| 12 | Food supplements | Probiotic supplements, vitamin formulations |

| 13 | Water | Bottled water, process water |

| 14 | Other foods | Prepared meals, composite dishes |

| 15 | Animal feed | Pet food, livestock feed, ingredients |

Additional Category Considerations

Beyond the 15 primary food categories, validation and verification studies may incorporate supplementary categories including pet food and animal feed, environmental samples from food or feed production environments, and primary production samples [9]. The overlap between validation scope, method scope, and laboratory application scope must be carefully considered when designing verification studies, as illustrated in ISO 16140-3, Figure 3 [9].

Target Microorganisms Selection

Microorganisms of Public Health Significance

Selection of target microorganisms should be driven by the method's intended application and regulatory requirements. Pathogens of concern vary by food category and may include Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Cronobacter species, particularly in infant formula products [18].

Indicator Organisms and Spoilage Microorganisms

Beyond pathogens, verification studies often include indicator organisms that signal potential contamination or assess general microbiological quality. Recent method certifications have focused on microorganisms such as:

- Enterobacteriaceae: Detection methods validated for infant formula, infant cereals, and related ingredients [18]

- Total Bacterial Count: Quantitative methods for raw milk testing [18]

- Bacillus cereus: Enumeration methods in various food matrices [18]

- Yeast and Mold: Enumeration methods for various food products [18]

Experimental Design and Protocols

Two-Stage Verification Protocol

ISO 16140-3 specifies two distinct stages for verification of validated methods [9]:

Stage 1: Implementation Verification

- Purpose: Demonstrate that the user laboratory can perform the method correctly

- Protocol: Test one of the same food items evaluated in the validation study

- Acceptance Criteria: Obtain results similar to those from the validation study

Stage 2: Food Item Verification

- Purpose: Demonstrate that the user laboratory is capable of testing challenging food items within the laboratory's scope of accreditation

- Protocol: Test several challenging food items using defined performance characteristics

- Acceptance Criteria: Confirm the method performs well for these food items

Sample Size Considerations

The appropriate sample size for verification studies depends on several factors:

- Scope of Validation: Methods validated for a "broad range" (5+ categories) may require fewer samples per category

- Laboratory Scope: The specific food matrices routinely tested by the laboratory

- Statistical Power: The desired confidence level for detecting significant differences between methods

- Regulatory Requirements: Specific sample size mandates for certain food-pathogen combinations

Table 2: Method Verification Examples and Characteristics

| Validated Method | Target Microorganism | Food Categories | Test Portion | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iQ-Check EB | Enterobacteriaceae | Infant formula, infant cereals | Up to 375g | ISO 21528-2 |

| Petrifilm Bacillus cereus | Bacillus cereus | Various food categories | Standard method | ISO 7932:2004 |

| One Plate Yeast & Mould | Yeasts and moulds | Various food categories | Standard method | ISO 21527:2008 |

| InviScreen Salmonella | Salmonella spp. | Various food categories | Standard method | ISO 6579-1:2017 |

| Autof ms1000 | Confirmation of bacteria, yeasts, molds | Various agar media | Isolated colonies | Reference identification methods |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbiological Method Verification

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Verification Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Alternative proprietary methods | iQ-Check EB, Petrifilm plates, Soleris NF-TVC | Demonstrate comparable performance to reference methods |

| Reference culture strains | ATCC strains, NCTC strains | Provide known positive controls for target microorganisms |

| Selective agar media | XLD Agar, Chromogenic media | Isolate and identify target microorganisms from food matrices |

| Molecular detection kits | foodproof Salmonella Detection Kit, InviScreen Salmonella spp. Detection Kit | Detect target pathogens using DNA-based methods |

| Sample preparation reagents | foodproof StarPrep One Kit, foodproof Magnetic Preparation Kit | Extract and purify microbial DNA from food samples |

| Confirmation systems | Autof ms1000 (MALDI-TOF) | Confirm identity of isolated colonies using mass spectrometry |

Workflow Visualization

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Guide to Sample Size Calculation

In microbiological method verification, the foundation of a robust experimental design is the precise definition of the primary outcome and the establishment of a statistically justified level of precision. This initial step determines the validity, reproducibility, and regulatory acceptance of the method. A clearly articulated outcome, coupled with a pre-specified precision threshold, directly informs the sample size calculation, ensuring the study is sufficiently powered to detect meaningful effects or demonstrate equivalence. This protocol provides a structured framework for researchers and scientists in drug development to execute this critical first step.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome is the single most important variable, or endpoint, that the method verification study is designed to assess. It must be a specific, measurable, and unambiguous characteristic that directly reflects the method's performance.

Characteristics of a Well-Defined Primary Outcome:

- Specific: Precisely defined, leaving no room for interpretation.

- Measurable: Quantifiable using a reliable and validated technique.

- Relevant: Directly related to the objective of the microbiological method.

- Pre-specified: Defined before any data collection commences to avoid bias.

Acceptable Precision (Margin of Error)

The acceptable precision, often expressed as the margin of error (E), is the maximum tolerable difference between the point estimate derived from your sample data and the true population parameter. It represents the clinical or practical significance threshold. In method verification, this is the pre-defined limit within which the method's results are considered acceptable for their intended purpose. A smaller margin of error requires a larger sample size to achieve greater certainty.

Experimental Protocol: Defining Parameters for Sample Size Calculation

Purpose and Scope

This protocol outlines the procedure for formally defining the primary outcome and acceptable precision for a microbiological method verification study, which are critical inputs for subsequent sample size calculations.

Materials and Equipment

- Study protocol document

- Statistical software (e.g., R, SAS, PASS, nQuery)

- Relevant regulatory guidance documents (e.g., USP, ICH, CLSI)

Procedure

Step 1: Identify and Justify the Primary Outcome 1.1. Based on the method's objective (e.g., quantifying bacterial load, identifying specific pathogens, determining antimicrobial susceptibility), list all potential measurable outcomes. 1.2. Consult existing literature, regulatory guidelines, and internal stakeholder input to select the single most critical outcome. 1.3. Document a complete operational definition for the outcome, including the specific units of measurement, the measurement technology, and the sampling procedure.

Step 2: Determine the Acceptable Precision (Margin of Error, E) 2.1. Establish the margin of error based on one of the following, listed in order of preference: * Regulatory Standards: Use predefined limits from pharmacopeial standards (e.g., USP) or other regulatory guidance. * Clinical or Practical Significance: Define the smallest change or difference in the outcome that would be meaningful in a real-world application. * Historical Data: Analyze data from previous, similar studies or from a pilot study to estimate variability and inform a reasonable margin. 2.2. Justify the chosen value with a clear scientific or regulatory rationale and document it in the study protocol.

Step 3: Specify the Statistical Confidence Level 3.1. Select the confidence level (1 - α) for the study. A 95% confidence level (α = 0.05) is most common in scientific research. 3.2. Document this value, as it is a key component for sample size calculation.

Step 4: Document all Parameters for Sample Size Calculation 4.1. Compile the finalized parameters into a structured table within the study protocol to ensure clarity and transparency for all team members and reviewers.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The parameters defined in this protocol are not for immediate statistical analysis but are inputs for the sample size calculation. The subsequent statistical analysis plan will detail how the primary outcome, once measured, will be analyzed against these pre-defined precision goals.

Table 1: Defined Parameters for Sample Size Calculation in a Microbiological Method Verification Study

| Parameter | Description | Example: Bacterial Load Enumeration | Justification & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | The key variable being measured. | Mean log10 Colony Forming Units (CFU) per mL. | Directly measures the quantitative performance of the enumeration method. |

| Acceptable Precision (E) | The maximum tolerable margin of error. | ± 0.5 log10 CFU/mL. | Based on clinical relevance where a 0.5 log change is considered significant. |

| Confidence Level (1-α) | The probability that the confidence interval contains the true parameter. | 95% (α = 0.05). | Standard for scientific research to control Type I error. |

| Expected Standard Deviation (σ) | The anticipated variability in the data (estimated). | 0.8 log10 CFU/mL. | Estimated from a pilot study or previous similar experiments. |

Visualization of the Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points for defining the primary outcome and establishing precision.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiological Method Verification

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard Strains | Certified microbial strains (e.g., from ATCC) used as positive controls to ensure method accuracy and reproducibility. |

| Culture Media | Prepared and sterilized growth substrates (e.g., Tryptic Soy Agar, Mueller-Hinton Broth) for the propagation and enumeration of microorganisms. |

| Diluents and Buffers | Sterile solutions (e.g., Phosphate Buffered Saline, Saline) used for serial dilutions of microbial suspensions to achieve countable colony ranges. |

| Antimicrobial Agents | Standard powders or disks for susceptibility testing methods, requiring precise reconstitution and storage. |

| Neutralizing Agents | Components added to dilution blanks or media to inactivate residual antimicrobial or disinfectant effects in the sample. |

| Quality Control Organisms | Specific strains used to verify the performance and sterility of each batch of culture media and reagents. |

In microbiological method verification research, establishing a statistically significant result is only the first step. Determining the practical significance of that result through effect size is what translates a finding from a mere numerical difference into a meaningful scientific conclusion. While a P-value can indicate whether an observed effect is likely real (e.g., a difference between two microbial quantification methods), it does not convey the magnitude or importance of that effect [7] [19]. Effect size quantifies this magnitude, providing a scale-independent measure of the strength of a phenomenon [19].

The accurate determination of effect size is a critical prerequisite for a robust sample size calculation. It creates a direct bridge between statistical analysis and practical application, ensuring that a study is designed to be sensitive enough to detect differences that are not only statistically real but also scientifically or clinically relevant [20]. This step is therefore foundational for avoiding both wasted resources on overpowered studies and the ethical dilemma of underpowered studies that fail to detect meaningful effects [7].

Quantifying Effect Size: Key Measures and Calculations

The choice of effect size measure depends on the type of data and the study design. The following table summarizes common effect size measures used in biomedical and microbiological research.

Table 1: Common Effect Size Measures and Their Applications

| Effect Size Measure | Data Type | Formula | Interpretation (Cohen's Guidelines) | Common Use in Microbiology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen's d [19] | Continuous (Comparing two means) | ( d = \frac{M1 - M2}{SD_{pooled}} ) | Small: 0.2, Medium: 0.5, Large: 0.8 | Comparing mean microbial counts (e.g., CFU/mL) between a new and a reference method. |

| Pearson's r [19] | Continuous (Correlation) | - | Small: 0.1, Medium: 0.3, Large: 0.5 | Assessing the strength of a linear relationship between two quantitative measurements (e.g., optical density and cell concentration). |

| Odds Ratio (OR) [7] | Binary / Categorical | - | - | Comparing the odds of an event (e.g., detection of a pathogen) between two groups. |

| Cohen's f [21] [22] | Continuous (Comparing >2 means - ANOVA) | ( f = \sqrt{ \frac{\sum{i=1}^G \frac{Ni}{N} (\mui - \bar{\mu})^2}{\sigma{pooled}^2} } ) | - | Comparing alpha diversity metrics (e.g., Shannon entropy) across multiple sample groups or treatment conditions. |

For Cohen's d, the calculation involves the difference between two group means divided by the pooled standard deviation [19]. A d of 1 indicates the groups differ by 1 standard deviation. The formulas for comparing two means or two proportions, integral to these calculations, are well-established [7].

Determining Effect Size for Study Planning

Selecting an appropriate effect size for a sample size calculation is a critical decision. Two primary approaches guide this selection, each with distinct advantages.

Table 2: Methods for Determining Effect Size in Study Planning

| Method | Description | Application in Method Verification | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Clinically Important Difference (MCID) [20] | The smallest effect that is considered scientifically or clinically meaningful. | Defining the smallest difference in analytical performance (e.g., sensitivity, precision) that would impact the method's utility. | Anchors the study in practical significance; requires expert input and consensus. |

| Conventional Method [20] | Based on effect sizes observed in previous similar studies, pilot data, or meta-analyses. | Using data from a preliminary pilot study or published validation studies of similar methods to estimate a realistic effect. | Provides a data-driven estimate; may not reflect the specific context of the new method. |

Addressing Uncertainty in Effect Size Estimation

Effect size is rarely known with absolute certainty before a study is conducted. To manage this uncertainty, researchers should [20]:

- Perform Sensitivity Analysis: Calculate sample sizes and power for a range of plausible effect sizes (e.g., the estimated MCID, and slightly larger and smaller values) to understand how the required sample size changes.

- Consider Bayesian Assurance: This method incorporates prior knowledge and uncertainty about the effect size into the sample size calculation, leading to more robust study designs.

Experimental Protocol: Determining Effect Size for a Microbiological Study

This protocol outlines a step-by-step process for determining the effect size to be used in power analysis for a study comparing two microbiome analysis methods.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Effect Size Determination in Microbiome Studies

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Large Microbiome Database (e.g., American Gut Project, FINRISK) [21] [22] | Provides a large, population-level dataset for robust effect size calculation for various metadata variables. |

| Effect Size Analysis Software (e.g., Evident, G-Power, R, Python) [8] [21] [22] | Tools to compute effect sizes (e.g., Cohen's d, f) from pilot data or large databases and to perform subsequent power analysis. |

| Pilot Study Data [7] [20] | A small-scale preliminary dataset used to estimate means, standard deviations, and prevalence for the outcomes of interest. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for determining effect size, integrating both pilot data and large public databases.

Detailed Methodology

The protocol below is adapted from the Evident workflow for power analysis in microbiome studies [21] [22].

Objective: To derive an effect size for comparing the mean α-diversity (Shannon entropy) between two independent groups (e.g., two sample types or two DNA extraction methods).

Materials and Software:

- A large microbiome dataset (e.g., from the American Gut Project) OR a pilot dataset from your specific experiment.

- Statistical software (e.g., Evident, R, Python, G*Power).

Procedure:

- Define Population and Parameter: Clearly identify the population and the key outcome variable (e.g., Shannon entropy).

- Compute Population Parameters:

- If using a large database (like AGP), calculate the average Shannon entropy (( \mui )) and the population variance (( \sigmai^2 )) for each group. With large sample sizes (( N_i )), these are considered robust estimates of the true population parameters [22].

- If using a pilot study, calculate the mean (( Mi )) and standard deviation (( SDi )) for each group from your pilot data.

- Calculate Pooled Variance: Under the assumption of homoscedasticity, compute the pooled variance (( \sigma{pooled}^2 )) by averaging the empirical variances from each group, weighted by their sample sizes [22]: ( \sigma{pooled}^2 = \frac{\sum{i=1}^G Ni \sigmai^2}{\sum{i=1}^G N_i} )

- Compute Effect Size:

- Use Effect Size in Power Analysis: Input the calculated effect size (d), along with the desired significance level (α, typically 0.05) and power (1-β, typically 0.8), into statistical software to determine the required sample size for your main study [7].

Determining the effect size is not a mere statistical formality but a fundamental exercise in scientific reasoning. By rigorously quantifying the magnitude of the effect a study is designed to detect—through either the MCID or evidence-based conventional methods—researchers ensure that their microbiological method verification is both statistically sound and practically relevant. This step guarantees that valuable resources are invested in studies capable of detecting meaningful differences, thereby strengthening the validity and impact of research outcomes in drug development and public health.

In the context of microbiological method verification, establishing acceptable error rates is a fundamental step in the sample size calculation process. This step ensures that the study is designed with a pre-defined tolerance for risk, balancing the chance of false positives against the risk of false negatives. A well-considered balance between Type I (α) and Type II (β) errors is critical for developing a robust, reliable, and scientifically defensible method. Setting these parameters is not an arbitrary exercise but a strategic decision that directly impacts the credibility of the research and the efficacy of the resulting microbiological method [7].

Defining Type I (Alpha) and Type II (Beta) Errors

Statistical hypothesis testing in method verification involves a null hypothesis (H₀), which typically states that there is no effect or no difference, and an alternative hypothesis (H₁) that states there is a meaningful effect [7].

- Type I Error (Alpha - α): A Type I error occurs when the null hypothesis (H₀) is incorrectly rejected. In practical terms, it is the probability of concluding that a new method is different or superior when, in fact, it is not. This is known as a false-positive finding [7]. The alpha level (α) is the threshold set by the researcher for accepting this risk. An α of 0.05 implies a 5% risk of a false positive.

- Type II Error (Beta - β): A Type II error occurs when the null hypothesis is incorrectly retained. This represents the failure to detect a true effect, resulting in a false-negative conclusion. In method verification, this would mean failing to identify a true, practically significant difference between methods [7]. The probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis is the statistical power of the test, calculated as 1-β [23] [7].

The following table summarizes these core concepts:

Table 1: Definitions of Key Statistical Error Parameters

| Parameter | Symbol | Common Value | Definition | Consequence in Method Verification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I Error Rate | α | 0.05 | Probability of a false positive; rejecting H₀ when it is true. | Concluding a new method is different when it is not. |

| Confidence Level | 1-α | 0.95 (95%) | Probability of correctly not rejecting a true H₀. | Confidence that a "significant" finding is real. |

| Type II Error Rate | β | 0.20 | Probability of a false negative; failing to reject H₀ when it is false. | Failing to detect a true, meaningful difference between methods. |

| Statistical Power | 1-β | 0.80 (80%) | Probability of correctly rejecting a false H₀. | The ability of the study to detect a true effect if it exists. |

The Interrelationship of Alpha, Beta, Effect Size, and Sample Size

The parameters α, β, effect size, and sample size are intrinsically linked. A change in one necessitates an adjustment in at least one of the others to maintain the same statistical properties [7].

- Effect Size: This is the magnitude of the difference or effect that the study is designed to detect. It is a measure of practical significance [23]. In microbiome studies, for example, the choice of diversity metric (e.g., Bray-Curtis vs. Jaccard) can profoundly influence the observed effect size and, consequently, the required sample size [24].

- Sample Size: For a given effect size, alpha, and power, a specific sample size is required. A smaller effect size, a lower alpha (stricter false-positive control), or a higher power (lower false-negative risk) will all increase the required sample size [23] [7].

Diagram 1: Relationship between key parameters in sample size calculation

Experimental Protocol for Establishing Alpha and Beta

Protocol: A Risk-Based Approach to Setting Error Rates

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for determining the appropriate alpha and beta levels for a microbiological method verification study.

4.1.1 Objective To define the Type I (α) and Type II (β) error rates for a study, ensuring the sample size calculation is aligned with the clinical, regulatory, and practical consequences of false-positive and false-negative outcomes.

4.1.2 Materials and Reagents

- Historical data from pilot studies or previous similar methods.

- Statistical software (e.g., G*Power, R) or online calculators (e.g., OpenEpi).

- Risk assessment documentation (e.g., FMEA output).

4.1.3 Procedure

- Define the Primary Hypothesis: Clearly state the null and alternative hypotheses for the method verification. For example, H₀: "There is no difference in the recovery rate between the new method and the standard reference method."

- Conduct a Risk Assessment: Use a structured risk assessment tool, such as Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), to evaluate the impact of both Type I and Type II errors [25]. Categorize the overall risk of the method as low, medium, or high based on factors like patient safety, product quality, and decision impact.

- Set the Alpha (α) Level:

- The standard value is α = 0.05 [7].

- For high-risk scenarios where a false positive could have severe consequences (e.g., releasing a contaminated product), a more stringent alpha (e.g., 0.01 or 0.001) should be used [7].

- For exploratory or pilot studies, a less conservative alpha (e.g., 0.10) may be acceptable [7].

- Set the Beta (β) Level and Calculate Power:

- Determine the Minimally Important Effect Size:

- This is the smallest difference from the null hypothesis that is considered practically or clinically significant [23].

- Use data from pilot studies, published literature, or subject matter expertise to define this value [23]. For instance, a 10% difference in microbial recovery might be deemed the minimum important effect.

- In microbiome studies, note that the choice of alpha and beta diversity metrics (e.g., Bray-Curtis, UniFrac) can influence the observed effect size and must be selected a priori to avoid p-hacking [24].

- Calculate the Sample Size: Input the defined α, β (power), and effect size into an appropriate statistical formula or software to determine the required sample size [23] [7].

4.1.4 Data Analysis and Interpretation The final output of this protocol is a justified set of parameters for sample size calculation. The chosen alpha and beta should be documented in the study protocol, along with the rationale based on the risk assessment.

Table 2: Example Risk-Based Selection of Alpha and Beta [7] [25]

| Risk Level | Example Context | Recommended α (Type I) | Recommended Power (1-β) | Recommended β (Type II) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Risk | Exploratory research, preliminary method feasibility. | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.20 |

| Medium Risk | Standard method verification, comparative studies. | 0.05 | 0.80 - 0.90 | 0.20 - 0.10 |

| High Risk | Final validation for product release, safety-critical methods. | 0.01 - 0.001 | 0.90 - 0.95 | 0.10 - 0.05 |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Power Analysis

| Item | Function in Error Rate & Sample Size Context |

|---|---|

| Statistical Software (G*Power, R, PS Power) | Used to perform the sample size calculation after alpha, beta, and effect size have been defined. These tools implement the complex statistical formulas required for different study designs [23]. |

| Pilot Study Data | Provides a preliminary estimate of key parameters like variance and baseline rates, which are necessary for calculating the effect size for the main study [23]. |

| Online Calculators (OpenEpi) | Provides a free and accessible interface for performing basic sample size and power calculations for common study designs [23]. |

| Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for Validation | A pre-defined SOP ensures that the rationale for choosing alpha, beta, and the resulting sample size is documented, consistent, and defensible during audits [26] [25]. |

| Risk Assessment Matrix | A formal tool (e.g., FMEA) used to objectively categorize the risk level of the method, which directly informs the stringency of the chosen alpha and beta levels [25]. |

Calculating the appropriate sample size is a fundamental step in designing a scientifically sound study for the verification of microbiological methods. An inadequate sample size can lead to Type I errors (false positives) or Type II errors (false negatives), compromising the reliability of the verification study and the validity of its conclusions [7]. The choice of sample size is intrinsically linked to the nature of the method being verified—whether it is qualitative (detecting the presence or absence of a microorganism) or quantitative (enumerating the number of microorganisms). This article provides detailed protocols for determining sample sizes for both method types within the context of microbiological method verification research for drug development.

Fundamental Distinctions Between Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

In microbiology, qualitative methods are used to detect the presence or absence of specific microorganisms, such as pathogens like Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli O157:H7. These methods are highly sensitive, with a limit of detection (LOD) that can be as low as 1 colony forming unit (CFU) per test portion, and results are typically reported as Positive/Negative or Detected/Not Detected [27]. In contrast, quantitative methods measure the numerical population of specified microorganisms, reported as CFU per unit weight or volume (e.g., CFU/g). These methods, such as aerobic plate counts, have a higher LOD, often 10 or 100 CFU/g, and require a series of dilutions to achieve a countable range of colonies on an agar plate [27].

The following table summarizes the core differences that influence sample size strategy:

Table 1: Core Differences Between Qualitative and Quantitative Microbiological Methods

| Parameter | Qualitative Methods | Quantitative Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Detection and identification [27] | Enumeration and quantification [27] |

| Reported Result | Presence/Absence (e.g., Detected/25g) [27] | Numerical count (e.g., 10⁵ CFU/g) [27] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Very low (theoretically 1 CFU/test portion) [27] | Higher (e.g., 10 CFU/g for plate counts) [27] |

| Key Performance Parameters | Sensitivity, Specificity [28] [29] | Accuracy, Precision, Linearity [29] |

Sample Size Calculation for Qualitative Method Verification