A Comprehensive Guide to the Real-Time PCR Quantitative Analysis Workflow: From Fundamentals to Advanced Validation

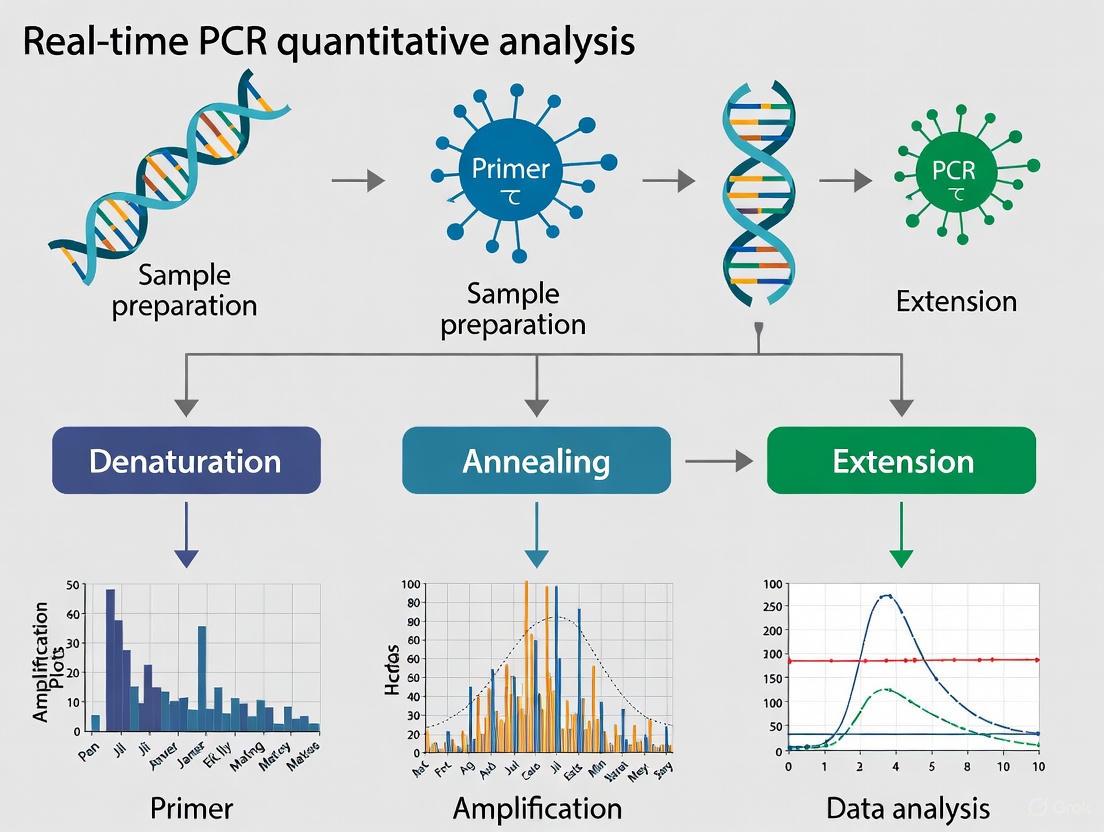

This article provides a systematic guide to the real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) workflow, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to the Real-Time PCR Quantitative Analysis Workflow: From Fundamentals to Advanced Validation

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide to the real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) workflow, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, detailed methodological steps for gene expression analysis, advanced troubleshooting and optimization techniques, and concludes with rigorous validation and data analysis frameworks. The content integrates current best practices, including the MIQE guidelines, to ensure the generation of precise, reproducible, and biologically significant data in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding Real-Time qPCR: Core Principles and Experimental Foundations

This application note delineates the fundamental operational and analytical distinctions between real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and end-point PCR. Framed within a comprehensive research workflow for quantitative analysis, we detail the superior quantification capabilities of qPCR, which monitors DNA amplification in real-time during the exponential phase, contrasted with the primarily qualitative nature of end-point PCR, which analyzes the final product yield. The document provides definitive protocols for both methods, supported by comparative data and workflow visualizations, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the appropriate technique for their specific molecular analyses.

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is an in vitro enzymatic process that amplifies a specific DNA sequence from a minimal starting amount, generating thousands to millions of copies [1]. While this core principle is universal, methodological variations have given rise to distinct technologies tailored for different applications. End-point PCR, also known as conventional PCR, is a foundational method where amplification is followed by a detection step that occurs after all thermal cycles are completed, typically via agarose gel electrophoresis [2] [3]. In contrast, real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR), also referred to as real-time PCR, incorporates fluorescent chemistry to monitor the accumulation of PCR product with each cycle of amplification in real time [4] [1]. This critical difference in detection timing fundamentally transforms the data output from qualitative to quantitative, making qPCR the gold standard for applications requiring precise measurement of nucleic acid concentration, such as gene expression analysis, viral load quantification, and genotyping in drug development pipelines [1] [3].

Comparative Analysis: qPCR vs. End-Point PCR

The choice between qPCR and end-point PCR hinges on the experimental objective—whether the goal is simply to detect the presence of a sequence or to accurately determine its initial quantity. The table below summarizes the core differences, which are explored in detail in the subsequent sections.

Table 1: Core Differences Between End-Point PCR and Quantitative PCR

| Feature | End-Point PCR | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Capability | Qualitative or semi-quantitative [2] | Quantitative (absolute or relative) [2] |

| Detection Method | Agarose gel electrophoresis and staining (e.g., ethidium bromide) [2] | Fluorescent dyes (e.g., SYBR Green) or sequence-specific probes (e.g., TaqMan) [4] |

| Data Collection Point | End of all cycles (plateau phase) [5] | During every cycle (exponential phase) [5] |

| Key Quantitative Metric | Band intensity (approximate) | Threshold Cycle (Cq or Ct) [4] |

| Throughput | Lower (requires post-processing) [2] | Higher (minimal post-processing) [2] |

| Precision & Dynamic Range | Low | High [4] |

| Multiplexing Potential | Low | High (with probe-based chemistries) [4] |

| Contamination Risk | Higher (open-tube post-processing) | Lower (closed-tube system) [3] |

Fundamental Principle: Timing of Detection

The most critical distinction lies in the phase of the amplification process where data is collected.

- End-Point PCR: Analysis occurs after the reaction is complete, in the plateau phase. In this phase, reagents have been depleted, and the reaction has stopped, meaning the final amount of product does not reliably correlate with the initial template amount [5] [3]. Even samples with different starting concentrations can yield similar final product amounts, making precise quantification unreliable [3].

- Real-Time qPCR: Fluorescence is measured during the exponential phase of every cycle. In this phase, the reaction efficiency is optimal and the amount of PCR product doubles with each cycle, providing a direct and quantitative relationship between the fluorescence signal and the initial concentration of the target nucleic acid [4] [1].

The qPCR Amplification Curve and Cq Value

In qPCR, the fluorescence is plotted against cycle number to generate an amplification curve. The Cq (Quantification Cycle) value is the fractional PCR cycle number at which the fluorescent signal crosses a predefined threshold, indicating a statistically significant increase in signal over the baseline [4] [1]. There is an inverse logarithmic relationship between the Cq value and the initial target concentration: a sample with a high starting concentration will produce a detectable signal earlier, resulting in a low Cq value, while a sample with a low starting concentration will have a higher Cq value [3]. This Cq value is the cornerstone of all qPCR quantification models.

Detection Chemistries in qPCR

Real-time qPCR utilizes two primary types of fluorescent chemistries:

- DNA-Binding Dyes (e.g., SYBR Green): These dyes fluoresce brightly when bound to double-stranded DNA. They are cost-effective and convenient but will bind to any dsDNA in the reaction, including non-specific products and primer-dimers, which can lead to overestimation of the target concentration [4] [6].

- Sequence-Specific Probes (e.g., TaqMan Probes): These oligonucleotide probes are labeled with a fluorescent reporter and a quencher. The close proximity of the quencher suppresses the reporter's fluorescence until the probe is hydrolyzed by the 5' nuclease activity of the DNA polymerase during amplification. This mechanism ensures that fluorescence is generated only upon successful amplification of the specific target sequence, providing greater specificity and enabling multiplexing (detection of multiple targets in a single tube) [4] [6].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows of both techniques, highlighting the key difference: the point of detection.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Standard End-Point PCR

This protocol is adapted from established molecular biology guides for conventional PCR amplification [7] [8].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for End-Point PCR

| Reagent | Function | Typical 50 µL Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | Contains the target sequence to be amplified. | 10-500 ng [7] |

| Forward & Reverse Primers | Define the 5' and 3' ends of the target sequence. | 0.1-1 µM each [7] |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Heat-stable enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands. | 1.25 units [8] |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for new DNA strands. | 200 µM each [8] |

| PCR Buffer (with MgCl₂) | Provides optimal chemical environment; Mg²⁺ is a cofactor for the polymerase. | 1X concentration [7] |

| Sterile dH₂O | Brings the reaction to the final volume. | To volume |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a master mix on ice containing all common reagents (water, buffer, dNTPs, polymerase) to minimize pipetting errors and ensure consistency between samples.

- Aliquot the master mix into individual PCR tubes.

- Add template DNA and primers to their respective tubes. Gently mix and briefly centrifuge to collect the contents at the bottom of the tube.

- If using a thermal cycler without a heated lid, overlay the reaction with a drop of mineral oil to prevent evaporation [8].

Thermal Cycling:

- Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run the following program [7]:

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 2 minutes (activates hot-start enzymes, ensures complete denaturation).

- Amplification (25-35 cycles):

- Denature: 94°C for 30 seconds.

- Anneal: 55-65°C* for 30 seconds.

- Extend: 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase of expected product.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes (ensures all products are fully extended).

- Hold: 4°C indefinitely.

*The annealing temperature should be optimized, typically 5°C below the primer's melting temperature (Tm) [7].

- Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run the following program [7]:

Post-Amplification Analysis by Gel Electrophoresis:

- Prepare a 1-2% agarose gel in TAE or TBE buffer containing a DNA intercalating dye like ethidium bromide or a safer alternative.

- Mix 2-10 µL of the PCR product with a DNA loading dye and load into the gel wells. Include a DNA molecular weight ladder.

- Run the gel at 5-10 V/cm until bands are adequately separated.

- Visualize the gel under UV light. The presence of a band at the expected size confirms amplification.

Protocol: Real-Time qPCR for Gene Expression

This protocol outlines a two-step reverse transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR) approach, which offers flexibility for analyzing multiple targets from a single RNA sample [4].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Two-Step RT-qPCR

| Reagent (Step 1: Reverse Transcription) | Function |

|---|---|

| Total RNA or mRNA | The template for cDNA synthesis. Purity and integrity are critical. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme that synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA. |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks for the cDNA strand. |

| Primers (Random Hexamers, Oligo-dT, or Gene-Specific) | Initiate cDNA synthesis from various regions or the 3' end of mRNAs. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA templates from degradation. |

| Reagent (Step 2: qPCR) | Function |

|---|---|

| cDNA (from Step 1) | Template for qPCR amplification. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, Mg²⁺, and optimized buffer. |

| Fluorescent Chemistry | SYBR Green dye or TaqMan probe assay for detection. |

| Forward & Reverse Primers | Define the amplicon for SYBR Green. For TaqMan, the assay includes primers and a probe. |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Reverse Transcription (RNA to cDNA)

- In a nuclease-free tube on ice, combine:

- 1 pg–1 µg of total RNA

- Reverse transcription primers (e.g., 50 ng Random Hexamers or 500 ng Oligo-dT)

- 1 mM dNTPs

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 10-15 µL.

- Heat the mixture to 65°C for 5 minutes to denature RNA secondary structure, then immediately place on ice.

- Add the remaining components:

- 1X Reverse Transcriptase Buffer

- 20 U RNase Inhibitor

- 200 U Reverse Transcriptase

- Mix gently and incubate in a thermal cycler:

- For Random Hexamers: 25°C for 10 minutes (primer annealing), followed by 37-42°C for 30-60 minutes (cDNA synthesis).

- For Oligo-dT: 37-42°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Inactivate the enzyme by heating to 70°C for 15 minutes. The resulting cDNA can be used immediately in qPCR or stored at -20°C.

Step 2: Quantitative PCR (cDNA Amplification and Detection)

- Assay Design: Design and validate primers with high efficiency (90-110%). For SYBR Green, ensure specificity by checking for primer-dimer formation and non-specific amplification. For TaqMan, use commercially available or custom-designed assays [4].

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a qPCR master mix on ice containing:

- 1X qPCR Master Mix (with appropriate dye or enzyme)

- Forward and Reverse Primers (e.g., 200-400 nM each) or a pre-formulated TaqMan Assay

- Nuclease-free water

- Aliquot the master mix into a qPCR plate.

- Add a diluted volume of the cDNA from Step 1 (e.g., 1-5 µL per 20 µL reaction). Include no-template controls (NTCs) and, for relative quantification, reference gene assays.

- Seal the plate with an optical adhesive film and centrifuge briefly.

- Prepare a qPCR master mix on ice containing:

- Thermal Cycling and Data Acquisition:

- Place the plate in the real-time PCR instrument. The instrument will run a thermal cycling protocol similar to end-point PCR but will measure the fluorescence in each well at the end of each annealing or extension cycle.

- A typical fast-cycling protocol might be:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-10 minutes.

- Amplification (40 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 15 seconds.

- Anneal/Extend & Acquire Data: 60°C for 30-60 seconds.

- Data Analysis:

- The instrument's software will generate an amplification plot and assign a Cq value to each reaction.

- For relative gene expression, use the Comparative Cq (ΔΔCq) method to calculate fold-change in gene expression between experimental and control groups, normalized to one or more stable reference genes [4].

Application in Drug Development and Research

The quantitative nature of qPCR makes it indispensable in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. Key applications include:

- Biomarker Discovery and Validation: qPCR is used to quantify expression levels of potential mRNA or microRNA biomarkers in patient samples [4] [9].

- Pharmacogenomics: Studying how genetic variations (SNPs) affect drug response by using allelic discrimination assays [4].

- Viral Load Monitoring: Precisely quantifying viral titers (e.g., HIV, HCV) in patient serum to monitor disease progression and antiviral treatment efficacy [1] [3].

- Cell and Gene Therapy: Assessing vector copy number in transduced cells and monitoring expression of therapeutic transgenes [2].

- Toxicology Studies: Evaluating changes in gene expression profiles of drug-metabolizing enzymes or stress response genes in pre-clinical models.

Within a rigorous real-time PCR quantitative analysis workflow, the distinction between end-point PCR and qPCR is foundational. End-point PCR remains a powerful, low-cost tool for applications demanding only qualitative confirmation of a target's presence, such as cloning or genotyping. However, for any research or diagnostic question requiring accurate, sensitive, and reproducible quantification of nucleic acids—from basic gene expression studies to critical drug development assays—real-time qPCR is the unequivocal method of choice. Its ability to measure amplification during the exponential phase via Cq analysis, combined with closed-tube workflows and advanced detection chemistries, provides the data integrity necessary for robust scientific conclusions.

Within the framework of real-time PCR (qPCR) quantitative analysis workflows, a foundational decision for researchers is selecting the appropriate quantification method. The choice between absolute quantification and relative quantification is dictated by the experimental question, the required output, and the available resources [10]. Absolute quantification determines the exact amount of a target nucleic acid in a sample, expressed as a concrete number (e.g., copies per microliter). In contrast, relative quantification measures the change in target quantity relative to a reference sample, such as an untreated control, and expresses this change as a fold-difference (e.g., n-fold induction or repression) [10] [11].

This application note delineates the core principles, applications, and procedural protocols for both methods to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the optimal quantification strategy for their study.

Core Concepts and Comparative Analysis

Absolute Quantification

Absolute quantification provides a direct count of target molecules. Two primary methodologies are employed:

- Standard Curve Method (qPCR): This method quantitates unknown samples by comparing them to a standard curve constructed from samples of known concentration [10]. The absolute quantities of the standards must be determined by an independent method, such as spectrophotometry (A260 measurement) [10].

- Digital PCR (dPCR) Method: A more recent innovation, dPCR partitions a sample into thousands of individual reactions. The target concentration is calculated directly from the ratio of positive to negative partitions using Poisson statistics, entirely eliminating the need for a standard curve [10] [12]. Recent studies highlight its superior accuracy for viral load quantification and rare target detection [13] [14].

Relative Quantification

Relative quantification analyzes changes in gene expression in a given sample relative to another reference sample, or calibrator (e.g., an untreated control) [10]. The result is a ratio expressing the relative change. Two common calculation methods are:

- Standard Curve Method: The quantity of the target is determined for all samples and the calibrator from a standard curve. The target quantity of each experimental sample is then divided by the target quantity of the calibrator [10].

- Comparative CT (ΔΔCT) Method: This method uses the formula 2-ΔΔCT to calculate relative expression levels. It requires that the amplification efficiencies of the target and reference gene are approximately equal and does not require a standard curve, increasing throughput [10] [11].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting the appropriate quantification method based on experimental goals and constraints.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of absolute and relative quantification methodologies.

| Feature | Absolute Quantification (Standard Curve) | Absolute Quantification (Digital PCR) | Relative Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Quantitation against a standard curve of known concentrations [10] | Direct counting of molecules via sample partitioning and Poisson statistics [10] [12] | Comparison of target levels relative to a calibrator sample and a reference gene [10] |

| Primary Output | Exact quantity (e.g., copies/µL, cell equivalents) [10] | Exact quantity (e.g., copies/µL) [13] | Fold-change (n-fold difference) [10] |

| Requires Standard Curve | Yes [10] | No [10] [12] | Yes (for standard curve method) / No (for ΔΔCT method) [10] |

| Requires Reference Gene | No (but can be used for normalization) [10] | No [10] | Yes [10] [11] |

| Key Applications | Viral titer determination, copy number variation, pathogen load [10] | Rare mutation detection, liquid biopsy, absolute viral load, rare gene targets [13] [12] [14] | Gene expression studies (e.g., drug treatment, disease states) [10] [11] |

| Advantages | Established, widely accessible technology [10] | High precision, absolute quantification without standards, tolerant to inhibitors [10] [13] | Simple standardization, no need for absolute standards, high throughput for ΔΔCT [10] [15] |

| Limitations | Variability from standard curve construction and dilution errors [10] | Higher cost, lower throughput, less automated workflows [13] | Results are relative, not absolute; requires stable reference gene [10] |

Application-Specific Selection Guidelines

When to Use Absolute Quantification

- Viral Load Quantification: Determining the absolute number of viral copies in a clinical sample is critical for disease management and understanding pathogenesis [10] [13]. A 2025 study demonstrated dPCR's superior accuracy for quantifying SARS-CoV-2, influenza, and RSV compared to standard qPCR [13].

- Rare Event Detection: The high sensitivity and precision of dPCR make it ideal for detecting rare mutations in oncology (e.g., in liquid biopsies) or quantifying rare gene targets like T-Cell Receptor Excision Circles (TRECs) from limited cell samples [12] [14].

- Copy Number Variation (CNV) Analysis: Absolute determination of gene copy number per genome is a core application for both standard curve and dPCR methods [12] [11].

When to Use Relative Quantification

- Gene Expression Profiling: The vast majority of gene expression studies, such as measuring transcriptional changes in response to a drug, chemical, or disease state, are ideally suited for relative quantification [10] [11]. The result of a fold-change is biologically meaningful and sufficient.

- High-Throughput Screening: When processing hundreds of samples to compare expression levels of a defined set of genes, the comparative CT method increases throughput by eliminating the need to run a standard curve on every plate [10].

- When Absolute Standards are Unavailable: Relative quantification is the preferred method when producing a standard of known absolute concentration is difficult or impossible [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Absolute Quantification using a Standard Curve (qPCR)

This protocol is for absolute quantification of a DNA target using a plasmid-derived standard curve on a qPCR instrument.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Absolute Quantification (Standard Curve)

| Item | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Standard (e.g., plasmid DNA, gDNA) | Provides known concentrations for calibration curve. | Must be a single, pure species; RNA contamination inflates copy number [10]. |

| Nucleic Acid Quantification Instrument (e.g., Spectrophotometer) | Measures concentration of standard stock (A260). | Essential for initial absolute measurement [10]. |

| qPCR Master Mix (with DNA polymerase, dNTPs) | Amplifies target sequence with fluorescence detection. | Choose dye-based (SYBR Green) or probe-based (TaqMan) chemistry [11]. |

| Target-specific Primers/Probes | Confidently amplifies and detects the target of interest. | Optimize design (amplicon 70-200 bp, Tm ~60°C, 40-60% GC) [11]. |

| Low-Binding Tubes & Pipette Tips | Used for making serial dilutions. | Prevents analyte loss due to adhesion, crucial for accuracy [10]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Standard Preparation: Prepare a high-concentration stock of purified plasmid DNA containing the target sequence. Ensure the preparation is free of RNA and contaminating DNA [10].

- Standard Quantification: Measure the concentration of the standard stock using a spectrophotometer (A260). Convert this concentration to copy number/µL using the molecular weight of the DNA [10].

- Serial Dilution: Perform a serial dilution (e.g., 10-fold) of the quantified standard over a range of at least 6 orders of magnitude (e.g., from 106 to 101 copies/µL). Prepare dilutions in a suitable buffer and divide into single-use aliquots to avoid freeze-thaw cycles [10].

- qPCR Setup: Plate the standard dilutions and unknown samples in replicates on a qPCR plate. Include a No-Template Control (NTC) to check for contamination. Use a reaction master mix containing fluorescence detection chemistry (e.g., intercalating dye or hydrolysis probe) [11] [16].

- Amplification: Run the plate on a real-time PCR instrument with the appropriate thermal cycling protocol.

- Data Analysis: The instrument software will generate a standard curve by plotting the Cq values of the standards against the log of their known concentrations. The absolute quantity of the unknown samples is determined by interpolating their Cq values from this curve [10].

Protocol 2: Absolute Quantification using Digital PCR (dPCR)

This protocol is for the absolute quantification of a DNA target without a standard curve, using a droplet-based or nanowell dPCR system.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Absolute Quantification (dPCR)

| Item | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| dPCR Master Mix | Optimized for efficient amplification in partitioned reactions. | Formulations are often specific to the dPCR platform. |

| Target-specific Primers/Probes | Confidently amplifies and detects the target of interest. | Requires extensive optimization of concentrations for multiplex assays [13]. |

| Partitioning Device/Consumable (e.g., droplet generator, nanowell chip) | Physically divides the sample into thousands of individual reactions. | Platform-dependent (e.g., droplet vs. nanowell); defines partition volume [13] [14]. |

| dPCR Instrument (with a fluorescence reader) | Performs thermal cycling and reads fluorescence in each partition. | Systems include Bio-Rad QX200, Thermo Fisher QuantStudio Absolute, QIAGEN QIAcuity [13]. |

| Viscosity Reduction Reagents (e.g., for crude lysate) | Reduces sample viscosity for efficient partitioning. | Critical when using crude cell lysates without DNA extraction [14]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Assay Optimization: Optimize primer and probe concentrations to minimize cross-reactivity and ensure efficient amplification, especially in multiplex formats [13]. For limited samples, a crude lysate protocol bypassing DNA extraction can be validated to prevent target loss [14].

- Reaction Assembly: Assemble the PCR reaction mix containing the sample, master mix, and optimized primers/probes.

- Sample Partitioning: Load the reaction mix into the dPCR system for partitioning. This step generates thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets (ddPCR) or loads the mixture into a microfluidic chip containing fixed nanowells [13].

- Endpoint PCR Amplification: Place the partitions into a thermal cycler and run a standard PCR protocol to endpoint amplification. Real-time fluorescence monitoring within partitions (qdPCR) can be used for precise condition determination [17].

- Partition Reading and Analysis: After cycling, the instrument reads the fluorescence in each partition. Partitions are classified as positive (containing the target) or negative (not containing the target). The absolute concentration of the target in the original sample, in copies/µL, is calculated automatically by the instrument's software using Poisson statistics to account for the fact that some partitions may contain more than one molecule [10] [12].

Protocol 3: Relative Quantification using the Comparative CT(ΔΔCT) Method

This protocol is for relative quantification of gene expression using a one-step RT-qPCR approach and the 2-ΔΔCT calculation method.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Relative Quantification (ΔΔCT)

| Item | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8 | High-quality starting template for gene expression. | Degraded RNA skews Cq values and results. |

| One-Step RT-qPCR Master Mix | Combines reverse transcription and qPCR in a single tube. | Normalizes against variables in RNA integrity and RT efficiency [10]. |

| Target Gene Assay (Primers/Probe) | Detects the gene of interest. | Must be optimized and efficient. |

| Endogenous Control Assay (Primers/Probe) | Detects a stably expressed reference gene (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin). | Critical for normalization; expression must not vary with experimental conditions [10] [11]. |

| Calibrator Sample (e.g., Untreated Control) | Serves as the 1x sample for comparison. | All fold-change values are expressed relative to this sample [10]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Validation Experiment (Prerequisite): Before running the main experiment, perform a validation assay to demonstrate that the amplification efficiencies of the target and reference genes are approximately equal (within 10%). This is a mandatory requirement for the ΔΔCT method to be valid [10].

- RNA Preparation and Reverse Transcription: Isolate high-quality RNA from all test and calibrator samples. In a one-step RT-qPCR protocol, the reverse transcription and amplification are combined in a single well.

- RT-qPCR Setup: Plate the RNA samples in replicates. Each sample must be amplified for both the target gene of interest and the endogenous control/reference gene. A No-Template Control (NTC) should be included.

- Amplification and Cq Determination: Run the RT-qPCR protocol. The instrument will generate Cq values for the target and reference genes in every sample.

- Data Calculation:

- Calculate ΔCT for each sample: ΔCT(sample) = CT(target gene) - CT(reference gene)

- Calculate ΔΔCT: ΔΔCT = ΔCT(test sample) - ΔCT(calibrator sample). The calibrator is typically the untreated control group.

- Calculate Fold-Change: Relative Quantity (RQ) = 2-ΔΔCT [10] [11]. A value of 1 indicates no change, >1 indicates up-regulation, and <1 indicates down-regulation.

The choice between absolute and relative quantification is a critical determinant of success in any qPCR-based study. Absolute quantification, enabled by either standard curves or the emerging power of dPCR, is indispensable when an exact molecular count is the primary objective, such as in viral load monitoring or rare mutation detection. Relative quantification remains the most practical and efficient method for assessing changes in gene expression across multiple samples, as it provides biologically relevant fold-change data without the need for absolute standards.

By aligning the experimental goal with the appropriate methodology as outlined in this application note, researchers can ensure the generation of robust, reliable, and interpretable data, thereby advancing their research and drug development workflows with confidence.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) is a cornerstone molecular technique renowned for its sensitivity, specificity, and capacity for precise nucleic acid quantification. Its applications span critical areas of biomedical research and drug development, including gene expression analysis, viral load detection, and biomarker validation [18] [19]. The reliability of qPCR data hinges on the optimized function and integration of its core components: enzymes, primers, probes, and fluorescent reporter molecules. Adherence to established international guidelines, such as the recently updated MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines, is paramount for ensuring the reproducibility, accuracy, and transparency of qPCR results [20] [21]. These guidelines provide a cohesive framework that emphasizes methodological rigor, from experimental design and execution to data analysis and reporting.

This application note provides a detailed overview of these essential qPCR components, framed within the context of a robust quantitative analysis workflow. It is structured to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals by offering not only foundational knowledge but also current comparative data, detailed protocols, and validated reagent solutions to support high-quality experimental outcomes.

Core Components of Real-Time qPCR

The fundamental reaction mixture of a probe-based qPCR assay integrates several key components that work in concert to enable specific amplification and real-time detection. The core components include a DNA polymerase with 5'→3' exonuclease activity, primers to define the target amplicon, a sequence-specific probe to facilitate detection, dNTPs as the building blocks for new DNA strands, a buffer system to maintain optimal chemical conditions, and MgCl₂ as a necessary co-factor for the polymerase [19].

Fluorescent Reporter Systems

Real-time qPCR relies on fluorescent reporters whose signal intensity is directly proportional to the amount of amplified PCR product [19]. The reaction progresses through four distinct phases: the linear ground phase with background fluorescence, the early exponential phase where the signal first rises above background (defining the cycle threshold, Ct), the linear exponential phase with doubling of amplicons each cycle, and the final plateau phase where the signal ceases to increase [19]. Two primary reporter systems are employed:

- DNA-Binding Dyes (e.g., SYBR Green): These dyes bind non-specifically to double-stranded DNA, resulting in a significant (20-100 fold) increase in fluorescence upon binding [19]. Their main disadvantage is the potential to bind to non-specific products like primer-dimers, which can lead to false positive signals and overestimation of target quantity.

- Fluorescent Probes (e.g., TaqMan): Probe-based assays offer superior specificity as they require hybridization of a sequence-specific oligonucleotide to the target amplicon in addition to primer binding [19]. The most common mechanism involves the 5'→3' exonuclease activity of Taq DNA polymerase. During amplification, the polymerase cleaves a probe that is bound to the template, separating a reporter dye from a quencher dye. This separation eliminates Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), resulting in a detectable fluorescent signal [19].

Table 1: Comparison of qPCR Fluorescent Reporter Systems

| Feature | DNA-Binding Dyes (SYBR Green) | Hydrolysis Probes (TaqMan) |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Lower - binds any dsDNA | Higher - requires specific probe hybridization |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Assay Design | Simpler, requires only primers | More complex, requires primers and probe |

| Multiplexing | Not possible | Possible with different reporter dyes |

| Primary Application | Single-target detection, presence/absence | Absolute quantification, SNP genotyping, multiplex detection |

Probe Technologies and Configurations

Probe-based assays have evolved to offer enhanced performance. Key configurations include:

- Dual-Labeled Probes: Feature a reporter dye (e.g., FAM, VIC, TET) at the 5' end and a quencher dye (e.g., TAMRA, BHQ) at the 3' end. The use of dark quenchers like BHQ, which dissipate energy as heat, reduces background signal compared to fluorescent quenchers like TAMRA [19].

- Minor Groove Binder (MGB) Probes: Incorporate an MGB moiety at the 3' end, which stabilizes the probe-DNA duplex. This allows for the use of shorter probes, which is advantageous for targeting sequences with high specificity, such as in single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) assays [19].

Applications and Comparative Performance

The specificity and quantitative nature of probe-based qPCR make it indispensable for a wide range of applications in research and diagnostics [19].

- SNP Genotyping: This method is a powerful tool for analyzing single base substitutions. It uses two allele-specific probes, each labeled with a different reporter dye (e.g., FAM and VIC). During amplification, the probe matching the perfect allele sequence binds stably and is cleaved, emitting fluorescence, while a probe with a single-base mismatch binds unstably and is not cleaved, resulting in no signal [19].

- Viral Detection and Quantification: qPCR is a gold standard for detecting and quantifying viral pathogens. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, diagnostic assays targeted specific genes of SARS-CoV-2 (e.g., S, E, M, N). The presence of the virus in a sample is indicated by an increase in fluorescence signal corresponding to the amplification of these targets [13] [19].

- Gene Expression Analysis: By converting mRNA to cDNA and then performing qPCR, researchers can quantify transcript levels with high sensitivity, detecting differences even in low-abundance mRNAs [19].

- DNA Methylation Analysis: Bisulfite-treated DNA can be analyzed with probes designed to distinguish between methylated and unmethylated cytosine bases, allowing for the assessment of epigenetic modifications [19].

Comparison with Emerging Technologies

While qPCR remains a robust and widely used method, emerging technologies like digital PCR (dPCR) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) offer complementary capabilities. A 2025 study comparing dPCR and real-time RT-PCR for respiratory virus detection (Influenza A/B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2) found that dPCR demonstrated superior accuracy and precision, particularly for samples with high viral loads [13]. dPCR's absolute quantification without the need for a standard curve makes it less susceptible to inhibitors and complex sample matrices, offering potential for enhanced diagnostic accuracy [13].

Similarly, a 2025 study on Helicobacter pylori detection in pediatric biopsies compared an IVD-certified qPCR kit, a PCR-HRM method, and NGS. While all three methods showed similar detection rates, the PCR-based methods were slightly more sensitive, identifying two additional positive samples missed by NGS [22]. This highlights that NGS, though powerful for detecting multiple pathogens simultaneously and characterizing complex samples, is currently limited by cost and complexity, making PCR variants a more attractive and cost-effective option for routine targeted diagnostics [22].

Table 2: Comparison of Quantitative Nucleic Acid Detection Platforms

| Platform | Key Principle | Quantification | Throughput | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-Time qPCR | Fluorescence detection during thermal cycling | Relative (requires standard curve) | High | Well-established, cost-effective, fast | Susceptible to PCR inhibitors |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | End-point fluorescence in partitioned reactions | Absolute (no standard curve) | Medium | High precision, resistant to inhibitors | Higher cost, lower throughput |

| nCounter NanoString | Color-coded probe hybridization | Digital (direct counting) | High | No enzymatic reaction, high multiplexing | Limited dynamic range for high copy numbers |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Massively parallel sequencing | Digital (read counts) | Very High | Unbiased, detects novel targets | High cost, complex data analysis |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: TaqMan Probe-Based qPCR for Gene Expression

Objective: To relatively quantify the expression level of a target gene in extracted RNA samples.

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from sample preparation to data analysis.

Materials:

- Extracted total RNA

- Reverse transcriptase kit

- TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (pre-designed primers and probe) or custom-designed primers/probe

- TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (contains Taq polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, MgCl₂)

- Nuclease-free water

- 96-well or 384-well optical reaction plates

- Real-time PCR instrument

Procedure:

- RNA Quality Control: Assess RNA integrity and concentration using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop) or fluorometry (e.g., Qubit).

- Reverse Transcription: Convert 100 ng - 1 µg of total RNA to cDNA using a reverse transcriptase enzyme according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Thaw and gently mix all reagents. Prepare the master mix on ice.

- For a single 20 µL reaction: 10 µL of 2X Master Mix, 1 µL of 20X TaqMan Gene Expression Assay, X µL of cDNA template (recommended equivalent of 10-100 ng input RNA), and nuclease-free water to 20 µL.

- Include a no-template control (NTC) by replacing cDNA with water.

- Pipette the reaction mix into the optical plate in triplicate for each sample.

- qPCR Run:

- Seal the plate and centrifuge briefly.

- Load the plate into the real-time PCR instrument.

- Use the following standard two-step cycling protocol:

- Hold Stage: 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 20 seconds.

- PCR Stage (40 cycles): 95°C for 1 second, 60°C for 20 seconds.

- Data Analysis:

- Set the fluorescence threshold in the exponential phase of the amplification plot to determine the quantification cycle (Cq) for each reaction.

- Use the comparative Cq method (ΔΔCq) to calculate the relative fold-change in gene expression, normalizing to an endogenous reference gene and a calibrator sample [20].

Protocol 2: Multiplex qPCR for Viral Detection

Objective: To simultaneously detect and differentiate multiple viral targets (e.g., Influenza A, Influenza B, RSV) from a single respiratory sample.

Materials:

- Nasopharyngeal swab sample in viral transport media

- Automated nucleic acid extraction system (e.g., KingFisher Flex, STARlet) with appropriate kits

- Commercial multiplex respiratory panel kit (e.g., Seegene Allplex) or custom-designed multiplex assay

- Real-time PCR instrument capable of detecting multiple fluorophores

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Subject the respiratory sample to mechanical lysis, if necessary, to break down mucus and release viral particles [13].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract RNA using an automated platform and a viral RNA/pathogen kit. Include an internal control during extraction to monitor extraction efficiency and potential PCR inhibition [13].

- Multiplex qPCR Setup:

- The multiplex master mix will contain multiple sets of forward/reverse primers and probes, each probe labeled with a spectrally distinct fluorophore (e.g., FAM for Influenza A, VIC for Influenza B, Cy5 for RSV).

- Aliquot the master mix into the PCR plate and add the extracted RNA template.

- qPCR Run:

- Use the cycling conditions specified by the kit manufacturer, which typically include a reverse transcription step and a subsequent PCR amplification.

- Data Interpretation:

- Analyze the amplification curves in each channel to determine the presence or absence of each virus. A sample is considered positive for a specific virus if the Cq value is below a validated cut-off.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A successful qPCR experiment depends on the quality and compatibility of its core reagents. The following table details essential materials and their critical functions within the workflow.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Probe-Based qPCR Assays

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Description | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Isolates high-purity DNA/RNA from complex biological samples; critical for removing PCR inhibitors. | MagMax Viral/Pathogen Kit, STARMag Universal Cartridge Kit [13] |

| Reverse Transcriptase Kit | Synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template for gene expression studies. | High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme that amplifies DNA; for probe-based assays, must possess 5'→3' exonuclease activity. | AmpliTaq Gold, FastStart Taq DNA Polymerase |

| qPCR Master Mix | Optimized buffer containing Taq polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and stabilizers for robust amplification. | TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Short oligonucleotides that define the start and end of the target amplicon for amplification. | Custom-designed, HPLC-purified; critical for specificity. |

| Hydrolysis Probe (TaqMan) | Sequence-specific oligonucleotide with reporter and quencher dyes; enables real-time detection via 5' nuclease assay. | Dual-labeled probes, MGB probes [19] |

| Commercial Assay Panels | Pre-validated, multiplexed assays for detecting multiple targets simultaneously. | Allplex Respiratory Panel, TaqMan Array Cards |

| Internal Positive Control | Control for nucleic acid extraction and amplification; detects PCR inhibition in clinical samples. | RNAse P gene detection in human samples [19] |

The integrity of real-time PCR quantitative analysis is fundamentally dependent on the careful selection and application of its core components. From the design of specific primers and probes to the choice of a robust enzyme system, each element must be optimized to ensure data accuracy and reproducibility. As the field advances, adherence to the MIQE 2.0 guidelines provides a critical framework for standardizing practices and reporting, thereby enhancing the reliability of research outcomes [20]. Furthermore, understanding the relative strengths and limitations of qPCR in comparison to emerging technologies like dPCR and NGS empowers scientists to select the most appropriate platform for their specific research or diagnostic question. By leveraging the detailed protocols, comparative data, and reagent solutions outlined in this application note, researchers and drug development professionals can confidently execute qPCR experiments that yield precise, reproducible, and biologically meaningful results.

Real-time PCR, also known as quantitative PCR (qPCR), is a powerful molecular technique that combines polymerase chain reaction amplification with fluorescent detection to monitor the accumulation of DNA products in real time [9]. Unlike conventional PCR that provides endpoint analysis, qPCR allows researchers to quantify the initial amount of a specific nucleic acid target with remarkable precision and over a wide dynamic range [11]. The fundamental output of a qPCR reaction is the amplification curve, a graphical representation of fluorescence signal versus PCR cycle number that contains critical information about the reaction performance and enables reliable quantification [23].

The amplification curve is typically divided into three distinct phases: the baseline phase with no detectable fluorescence increase, the exponential phase where product doubling occurs with each cycle, and the plateau phase where reaction components become depleted and amplification ceases [24]. Understanding the characteristics and proper interpretation of each phase, particularly the exponential phase, is essential for accurate gene quantification, proper assay validation, and meaningful experimental conclusions in both research and diagnostic applications [25] [26].

Core Principles of the Amplification Curve

The Three Phases of PCR Amplification

Baseline Phase: During the initial PCR cycles (typically cycles 1-15), the fluorescent signal remains at background levels as the accumulated product has not yet reached the detection threshold of the instrument. The baseline represents the background fluorescence that must be corrected for accurate quantification [27] [23].

Exponential Phase: This is the most critical phase for quantification, characterized by a rapid increase in fluorescence where the amount of PCR product theoretically doubles with each cycle. During this phase, all reaction components (primers, dNTPs, enzyme) are in excess, fueling consistent amplification efficiency. The exponential phase appears as a straight line when fluorescence is plotted on a logarithmic scale against cycle number [25] [24].

Plateau Phase: In the final phase of amplification, the reaction slows and eventually stops as essential components become depleted (primers, dNTPs) or the DNA polymerase loses activity. The fluorescence signal reaches a maximum level and shows minimal increase with additional cycles. Data from this phase are not considered quantitative [25] [24].

Understanding the Threshold Cycle (Ct)

The Threshold Cycle (Ct), also known as quantification cycle (Cq), is a fundamental parameter in qPCR analysis defined as the PCR cycle number at which the amplification curve crosses the fluorescence threshold [23]. This threshold is set within the exponential phase of amplification where the reaction is most efficient and reproducible. The Ct value is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid—a lower Ct value indicates a higher initial amount of target template, while a higher Ct value indicates a lower initial amount [23].

Proper threshold setting is crucial for accurate Ct determination. The threshold should be set:

- Sufficiently above the background fluorescence to avoid premature threshold crossing

- Within the exponential phase of all amplification curves being compared

- At a position where amplification curves display parallel log-linear phases [27]

Figure 1: The three phases of a qPCR amplification curve and determination of the Ct value. The Ct is identified where the curve crosses the threshold during the exponential phase.

The Critical Role of PCR Efficiency

PCR efficiency refers to the rate at which the target sequence is amplified during each cycle of the PCR reaction [26]. Ideally, efficiency should be 100%, meaning the target DNA doubles with every cycle during the exponential phase. In practice, efficiency is expressed as a percentage or a decimal value (e.g., 100% = 1.0, 90% = 0.9) and is a critical parameter that directly impacts quantification accuracy [24].

Efficiency can be calculated from a standard curve generated using serial dilutions of a known template concentration. The formula for calculating efficiency is:

E = 10(-1/slope) - 1

Where the slope is derived from the plot of Ct values against the logarithm of the template concentration [26] [28]. For a perfect reaction with 100% efficiency, the slope should be -3.32 [28].

Table 1: Interpretation of PCR Efficiency Values

| Efficiency Value | Slope | Interpretation | Impact on Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% (2.0) | -3.32 | Ideal efficiency | Accurate quantification |

| 90-110% | -3.1 to -3.6 | Acceptable range | Minimal error |

| <90% | >-3.6 | Low efficiency | Underestimation of quantity |

| >110% | <-3.1 | Apparent super-efficiency | Overestimation of quantity |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Amplification Efficiency

Objective: To determine the PCR amplification efficiency for a specific assay using a serial dilution series.

Materials Required:

- Template DNA or cDNA of known concentration

- qPCR master mix

- Target-specific primers and/or probes

- Nuclease-free water

- Appropriate qPCR instrument and consumables

Procedure:

- Prepare a 5- or 10-fold serial dilution series of the template spanning at least 5 orders of magnitude (e.g., 1:10, 1:100, 1:1,000, 1:10,000, 1:100,000).

- For each dilution, prepare qPCR reactions in triplicate according to the following setup:

- 10 µL qPCR master mix (2X concentration)

- 2 µL forward primer (10 µM)

- 2 µL reverse primer (10 µM)

- 1 µL probe (5 µM) if using hydrolysis probes

- 5 µL template DNA from appropriate dilution

- Adjust total volume to 20 µL with nuclease-free water

- Include no-template controls (NTC) containing nuclease-free water instead of template.

- Run the qPCR reaction using the following cycling conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-10 minutes

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute

- After the run, record the Ct values for each dilution.

Data Analysis:

- Plot the mean Ct value for each dilution against the logarithm of the template concentration or dilution factor.

- Generate a linear regression trendline through the data points.

- Calculate the slope of the trendline.

- Calculate the amplification efficiency using the formula: E = 10(-1/slope) - 1

- Assess the linearity of the standard curve using the coefficient of determination (R²). A value of R² ≥ 0.98 indicates excellent linearity [28].

Protocol 2: Validating Assay Performance Using MIQE Guidelines

Objective: To comprehensively evaluate qPCR assay performance according to MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines.

Materials Required:

- Test samples with varying target concentrations

- Reference gene assay with confirmed performance

- qPCR reagents as in Protocol 1

- Melt curve analysis capability (for SYBR Green assays)

Procedure:

- Specificity Assessment:

- For hydrolysis probe assays: Verify single amplification curves with characteristic sigmoidal shape.

- For SYBR Green assays: Perform melt curve analysis post-amplification by gradually increasing temperature from 60°C to 95°C while monitoring fluorescence. A single peak indicates specific amplification.

- Analyze no-template controls for absence of amplification.

Sensitivity and Dynamic Range Determination:

- Follow Protocol 1 to establish the linear dynamic range.

- Determine the limit of detection (LOD) as the lowest concentration at which 95% of positive samples are detected [28].

Precision Evaluation:

- Run intra-assay replicates (same run) and inter-assay replicates (different runs) for samples with high, medium, and low target concentrations.

- Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) for Ct values. CV should be <5% for technical replicates [25].

Efficiency Confirmation:

- Confirm that assay efficiency falls within 90-110% as calculated in Protocol 1.

Table 2: Quality Control Criteria for qPCR Assay Validation

| Parameter | Acceptance Criterion | Quality Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification Efficiency | 90-110% | Standard curve from serial dilutions |

| Dynamic Range | 5-6 orders of magnitude | Linear regression of dilution series |

| Specificity | Single peak in melt curve | Melt curve analysis (SYBR Green) |

| Precision | CV < 5% for Ct values | Replicate analysis |

| Linearity | R² ≥ 0.98 | Coefficient of determination |

| No-Template Control | No amplification or Ct > 40 | Include NTC in each run |

Protocol 3: Relative Quantification Using the ΔΔCt Method

Objective: To determine relative changes in gene expression between different experimental conditions.

Materials Required:

- cDNA samples from test and control conditions

- Validated assays for target gene and reference gene(s)

- qPCR reagents as in previous protocols

Procedure:

- For each sample (test and control), run qPCR reactions for both the target gene and reference gene(s) in triplicate.

- Include appropriate controls (NTC, positive control).

- Record Ct values for all reactions.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the ΔCt for each sample: ΔCt = Ct(target gene) - Ct(reference gene)

- Calculate the ΔΔCt: ΔΔCt = ΔCt(test sample) - ΔCt(control sample)

- Calculate the relative quantification (RQ) or fold change: RQ = 2-ΔΔCt

Important Considerations:

- The ΔΔCt method assumes the amplification efficiencies of the target and reference genes are approximately equal and close to 100% [26].

- If efficiencies are not equal, use an efficiency-corrected calculation: RQ = (Etarget)^(-ΔCttarget) / (Ereference)^(-ΔCtreference) [27]

- Select reference genes that show stable expression across experimental conditions.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Troubleshooting Amplification Curve Abnormalities

Table 3: Common Amplification Curve Abnormalities and Solutions

| Abnormality | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Irregular or jagged curves | Instrument instability, bubbles in reaction | Centrifuge plates before run; check instrument calibration [25] |

| Late Ct values (>35) | Low template concentration, inhibition | Increase template amount; purify sample [29] |

| No amplification | Template degradation, primer design issues | Check RNA/DNA quality; redesign primers |

| Multiple peaks in melt curve | Non-specific amplification, primer dimers | Optimize annealing temperature; redesign primers |

| Efficiency >110% | PCR inhibition in concentrated samples, pipetting errors | Dilute samples; improve pipetting technique [29] |

| Efficiency <90% | Poor primer design, reaction inhibitors | Redesign primers; purify template |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR

| Reagent/Material | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and salts | Choose based on application; may include passive reference dye [25] |

| Hydrolysis Probes (TaqMan) | Target-specific detection with fluorophore and quencher | Provides high specificity; requires custom design [11] |

| SYBR Green Dye | Intercalating dye that binds double-stranded DNA | Cost-effective; requires melt curve analysis for specificity [11] |

| Passive Reference Dye (ROX) | Normalizes for non-PCR related fluorescence fluctuations | Included in many master mixes; essential for plate-to-plate normalization [25] |

| Primers | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides for target amplification | Design for 15-30 bp length, 40-60% GC content, Tm ~60-65°C [11] |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent for reactions | Prevents RNA/DNA degradation |

| dNTPs | Nucleotides for DNA synthesis | Component of master mix |

| UNG Enzyme | Prevents carryover contamination | Degrades uracil-containing DNA from previous reactions [9] |

Advanced Concepts and Applications

The Impact of Efficiency on Quantification Accuracy

PCR efficiency significantly impacts quantification accuracy, particularly in relative gene expression studies using the ΔΔCt method. Even small deviations from 100% efficiency can introduce substantial errors in calculated fold-changes [26].

The error introduced by efficiency discrepancies can be calculated as: Error (%) = [(2^n/(1+E)^n) × 100)] - 100 Where E = efficiency of PCR and n = cycle number [26].

For example, if the PCR efficiency is 0.9 instead of 1.0 at a threshold cycle of 25, the resulting error will be 261%, meaning the calculated expression level would be 3.6-fold less than the actual value [26].

Figure 2: Comprehensive qPCR workflow highlighting the critical role of amplification efficiency throughout the experimental process. The cyclic nature demonstrates that unacceptable efficiency requires returning to assay optimization.

High-Throughput Data Analysis Methods

For laboratories processing large numbers of samples, high-throughput analysis methods such as the "dots in boxes" approach can efficiently visualize multiple assay characteristics simultaneously [28]. This method plots PCR efficiency on the y-axis against ΔCq (difference between Cq of NTC and lowest template dilution) on the x-axis, creating a graphical box where successful experiments should fall (efficiency 90-110%, ΔCq ≥3) [28].

Each data point can be assigned a quality score (1-5) based on multiple parameters including linearity, reproducibility, fluorescence consistency, curve steepness, and shape. This approach allows rapid evaluation of overall experimental success across multiple targets and conditions [28].

The qPCR amplification curve contains a wealth of information that, when properly demystified, enables robust and reliable nucleic acid quantification. Understanding the three distinct phases of amplification—baseline, exponential, and plateau—provides the foundation for accurate data interpretation. The exponential phase is particularly critical as it provides the Ct values used for quantification and reflects the PCR efficiency that fundamentally impacts calculation accuracy.

Proper experimental design, including rigorous assay validation according to MIQE guidelines, careful attention to efficiency determination, and appropriate implementation of quantification methods (ΔΔCt or standard curve), ensures generation of biologically meaningful results. Troubleshooting common amplification curve abnormalities and understanding their underlying causes further strengthens experimental outcomes.

As qPCR continues to be a cornerstone technique in molecular biology, clinical diagnostics, and drug development, mastery of amplification curve interpretation remains an essential skill for researchers seeking to generate quantitative data that withstands scientific scrutiny.

Within the framework of real-time PCR quantitative analysis research, the initial phases of RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis constitute the foundational pillars determining the entire workflow's success. This application note details a standardized, robust protocol designed to overcome common challenges such as RNA degradation, genomic DNA contamination, and inhibitor carryover, which are critical for generating reliable, reproducible gene expression data in drug development and clinical research settings [30] [31]. The procedures outlined herein are optimized to ensure high nucleic acid integrity and reverse transcription fidelity, directly impacting the accuracy of downstream quantitative PCR (qPCR) results.

Technical Specifications and Performance Data

Selecting appropriate reagents based on performance metrics is crucial for a robust workflow. The following tables summarize key quantitative data from comparative evaluations of different RNA extraction methods and reverse transcriptase enzymes.

Table 1: Comparison of RNA Extraction Methods from Challenging Samples

| Extraction Method / Kit | Sample Type | Average Yield | Purity (A260/A280) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastPure Cell/Tissue Kit (Vazyme) [30] | Rat liver, HEK 293 cells | High | High | Good integrity, high yield, and high purity |

| Modified SDS-Based Method [32] | Musa spp. (banana) tissues | 2.92-6.30 µg/100 mg | 1.83-2.25 | Effective for polysaccharide/polyphenol-rich tissues |

| Stool RNA Purification Kit (Norgen) [31] | Human stool | High | High | High purity, sensitive downstream detection |

| TRIzol Reagent [33] [32] | Various tissues | Variable | Variable | Effective lysis; may require additional purification |

Table 2: Reverse Transcriptase Enzyme Performance Characteristics

| Enzyme Type | Reaction Temperature | Reaction Time | RNase H Activity | Ideal For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMV Reverse Transcriptase [34] | 42°C | 60 min | High | Standard templates |

| MMLV Reverse Transcriptase [34] | 37°C | 60 min | Medium | Longer transcripts (<7 kb) |

| Engineered MMLV (e.g., SuperScript IV) [34] | 50-55°C | 10 min | Low | Challenging RNA, high GC content |

| HiScript IV (Vazyme) [30] | 37-50°C | 5-15 min | No | Low-input/degraded RNA, fast workflow |

Optimized Protocol for RNA Extraction

Sample Lysis and Homogenization

The first critical step is the effective disruption of cells or tissues while maintaining RNA integrity.

- Animal Tissues/Cells: For manual extraction from tissues like rat liver or cultured cells like HEK 293, use ~10 mg of tissue or 1x10^6 cells. Homogenize in lysis buffer containing guanidine salts using bead beating or mechanical homogenization. For Vazyme's FastPure Kit, homogenization is followed by centrifugation to clear the lysate [30].

- Plant Tissues: For challenging plant samples like Musa spp., grind 100 mg of tissue in liquid nitrogen. Use a modified SDS-based lysis buffer supplemented with PVP and β-mercaptoethanol to bind polyphenols and prevent oxidation [32].

- Complex Samples (e.g., Stool): Homogenize 200 µL of sample preserved in RNAlater in a bead tube with the kit's lysis buffer at 2,850 rpm for 5 minutes [31].

RNA Purification and DNase Treatment

Purification removes contaminants like proteins, salts, and most critically, genomic DNA.

- Silica-Membrane Purification: This is the basis for many kit-based methods (e.g., Vazyme, Norgen, Qiagen). The cleared lysate is mixed with ethanol and loaded onto a silica membrane. RNA binds while contaminants pass through [30] [31].

- DNase I Treatment: To eliminate gDNA contamination, apply an RNase-free DNase I solution directly onto the silica membrane and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes [31] [33]. This step is essential for accurate gene expression analysis.

- Alternative gDNA Removal: As an alternative to DNase I, thermolabile double-strand-specific DNases (e.g., ezDNase) can be used. They are inactivated by a short 5-minute heating step at 55°C, simplifying the workflow and reducing RNA loss [34].

- Washing and Elution: Wash the membrane with an ethanol-based wash buffer to remove salts and other residues. Elute the pure RNA in nuclease-free water [33]. Elution at room temperature can improve yield [35].

RNA Quality Assessment

Rigorous quality control is non-negotiable for reliable downstream results.

- Quantification and Purity: Use a spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) to measure concentration. Assess purity via A260/A280 ratio (ideal range: 1.8-2.1) and A260/A230 ratio (ideal >2.0), indicating minimal protein/phenol or salt/organic solvent contamination, respectively [36] [31] [32].

- Integrity Assessment: Evaluate RNA integrity by agarose gel electrophoresis. Sharp, clear ribosomal RNA bands (28S and 18S in eukaryotes) with the 28S band approximately twice the intensity of the 18S band indicate intact RNA [30] [32]. For a more precise measure, use an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or Qubit RNA IQ Assay [32].

Optimized Protocol for cDNA Synthesis

Reaction Setup and Primer Selection

The reverse transcription reaction must be carefully assembled based on the RNA template and research goals.

- RNA Input: Use 10 pg to 1 µg of total RNA per 20 µL reaction, with 500 ng being a standard starting point for gene expression studies. Normalize RNA input across samples for accurate comparative analysis [36].

- Primer Choice: Selection depends on the application:

- Oligo(dT) Primers: Anneal to the 3' poly-A tail of mRNA, ideal for synthesizing cDNA for reverse transcriptase qPCR (RT-qPCR) of protein-coding genes. They provide specific priming but can lead to 5' bias in long transcripts [34].

- Random Hexamers: Prime throughout the RNA sequence, ideal for degraded RNA, non-polyadenylated RNAs, or when analyzing multiple regions of a transcript [36] [34].

- Gene-Specific Primers: Provide the most specific priming but are only suitable for synthesizing cDNA for one target.

- Blended Primers: Some kits (e.g., Bio-Rad iScript) use a blend of oligo(dT) and random hexamers to provide comprehensive coverage [36].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for RNA to cDNA Workflow

| Item | Function | Example Products & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer | Disrupts cells, inactivates RNases | Often contains guanidine thiocyanate (commercial kits) or SDS (for plants) [30] [32]. |

| Silica Spin Column | Binds and purifies RNA | Found in most commercial kits; enables efficient washing [30] [31]. |

| DNase I, RNase-free | Digests contaminating genomic DNA | Critical for accurate RT-qPCR. Can be used on-column or in-solution [31] [34]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes cDNA from RNA template | Engineered enzymes (e.g., SuperScript IV, HiScript IV) offer high stability and yield [30] [34]. |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks for cDNA synthesis | Use high-quality dNTPs at 0.5-1 mM each [34]. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA template from degradation | Essential for handling low-abundance targets [34]. |

Thermal Cycling and Post-Synthesis Handling

The incubation conditions are key to efficient cDNA synthesis, especially for complex RNA templates.

- Primer Annealing: Incubate the reaction mix at 25°C for 5-10 minutes to allow primers to anneal to the RNA template [36] [34].

- cDNA Synthesis (Polymerization): Incubate at the optimal temperature for the reverse transcriptase. For thermostable enzymes like SuperScript IV or HiScript IV, use 50-55°C for 10-20 minutes. The higher temperature helps denature RNA secondary structures, leading to more full-length cDNA and higher yields [30] [34].

- Reaction Termination: Inactivate the enzyme by heating at 85°C for 5 minutes or 95°C for 1 minute [36] [34].

- cDNA Storage: For immediate use, store diluted cDNA at 4°C. For long-term storage, prepare aliquots and store at -20°C or -80°C to minimize freeze-thaw cycles, which can degrade cDNA [36].

Workflow and Evaluation Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the complete integrated workflow from sample to cDNA, highlighting key decision points and quality control checkpoints.

The protocol's effectiveness is demonstrated through a comparative evaluation of different methods, as illustrated below.

This application note provides a detailed, evidence-based framework for establishing a robust and reliable workflow from RNA extraction to cDNA synthesis. By adhering to the optimized protocols and quality control measures outlined—including the selection of appropriate extraction methods for specific sample types, the use of engineered reverse transcriptases for high-efficiency cDNA synthesis, and rigorous quality assessment—researchers can significantly enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of their real-time PCR quantitative data. The successful application of this workflow is confirmed by its validation in downstream quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), enabling precise gene expression analysis crucial for advancing research in drug development and molecular diagnostics [30] [32].

Executing a Reliable qPCR Assay: A Step-by-Step Protocol from Primer Design to Data Acquisition

In the realm of molecular biology and drug development, the real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) workflow stands as a cornerstone technology for gene expression analysis, validation of therapeutic targets, and diagnostic assay development. The reliability of any qPCR experiment is fundamentally dependent on the initial primer design phase, where strategic decisions determine the specificity, efficiency, and accuracy of subsequent quantitative results. Poorly designed primers can lead to costly experimental failures, false positives in diagnostic applications, and irreproducible data in research settings. This application note establishes a comprehensive protocol for designing PCR primers with an emphasis on two critical aspects: ensuring target specificity through bioinformatic tools like Primer-BLAST and proactively avoiding single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that could compromise assay performance. By integrating these considerations into a standardized workflow, researchers and drug development professionals can achieve superior experimental outcomes with enhanced reliability and reduced optimization time.

Foundational Principles of PCR Primer Design

Effective primer design extends beyond merely identifying complementary sequences flanking a target region. It requires careful balancing of multiple physicochemical properties that collectively determine primer behavior during amplification. The following parameters represent the essential foundation upon which specific and robust PCR assays are built:

Table 1: Essential Parameters for Optimal Primer Design

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 bases [37] [38] | Balances specificity and binding efficiency; shorter primers may cause nonspecific binding. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 60–64°C [38]; Optimal difference between paired primers: ≤ 2°C [38] | Ensures simultaneous binding of both primers to the template. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [37]; Ideal: 50% [38] | Provides sequence complexity while maintaining appropriate Tm; extremes can hinder binding. |

| GC Clamp | Presence of 2 G or C bases within the last 5 bases at the 3' end [37] | Stabilizes primer-template binding at the critical elongation point. |

| 3' End Stability | ΔG > -9 kcal/mol for secondary structures [38] | Prefers stable 3' ends to reduce false priming while avoiding overly stable dimers. |

Several critical design elements must be avoided to prevent assay failure. Repetitive sequences, including runs of four or more identical bases (e.g., AAAA) or dinucleotide repeats (e.g., ATATAT), can cause mispriming [37]. Similarly, primers must be screened for self-complementarity and cross-complementarity between forward and reverse primers, which can lead to primer-dimer formation that consumes reaction resources and reduces target amplification efficiency [37] [39]. The ΔG value for any potential secondary structures should be weaker (more positive) than -9.0 kcal/mol [38].

Advanced Strategy: Ensuring Specificity and Avoiding SNP Interference

The Critical Importance of Specificity Checking

Primer specificity ensures that amplification originates exclusively from the intended genetic target, a non-negotiable requirement for both basic research and clinical diagnostic applications. Non-specific amplification can generate false positive signals, quantitate irrelevant targets, and completely invalidate experimental results. This risk is particularly acute in genetically complex samples or when detecting low-abundance transcripts. The Primer-BLAST tool, developed and maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), provides an integrated solution that combines primer design with automated specificity validation against comprehensive nucleotide databases [40] [41].

The Critical Importance of SNP Avoidance

Single nucleotide polymorphisms represent the most common form of genetic variation in genomes. When undetected SNPs occur within primer binding sites, particularly at the critical 3' end, they can severely impede primer annealing and extension, leading to allele dropout, reduced amplification efficiency, and genotyping inaccuracies [42]. This failure mode has profound implications for clinical diagnostics where heterozygous samples might be misclassified, or for pathogen detection where variant strains could escape identification. Proactive SNP checking during primer design is significantly more effective than post-hoc troubleshooting of failed assays.

Integrated Workflow for Specificity and SNP Avoidance

Diagram: Primer Design and Validation Workflow

Protocol: Designing SNP-Aware Primers Using Primer-BLAST

This step-by-step protocol ensures the production of specific, SNP-resistant primers suitable for sensitive qPCR applications in drug development and clinical research.

Pre-Design Sequence Analysis

- Sequence Acquisition: Obtain the complete mRNA reference sequence (RefSeq) for your target gene, preferably using the NCBI Nucleotide database. The accession number format (e.g., NM_XXXXXX) is ideal for subsequent steps [40].

- Flanking Sequence Determination: For the genomic region of interest, ensure you have at least 50 nucleotides of high-quality sequence information both upstream and downstream of your target site [42]. This provides adequate context for robust primer design.

- SNP Screening: Before designing primers, use the dbSNP database (maintained by NCBI) to identify known polymorphisms within your target region. Manually inspect the primer binding regions, especially the final 5 nucleotides at the 3' end, and exclude any candidates where polymorphisms occur at these critical positions.

Primer-BLAST Specificity Analysis

- Access the Tool: Navigate to the NCBI Primer-BLAST submission form [40] [41].

- Input Template: Enter the RefSeq accession number or FASTA sequence in the "PCR Template" section. Using an mRNA reference sequence ensures the tool can design primers specific to particular splice variants [40].

- Configure Primer Parameters:

- Set Specificity Checking Parameters (Critical Step):

- Under "Primer Pair Specificity Checking Parameters," select the appropriate source organism [40] [41]. This restricts the search and increases precision.

- Choose the "Refseq mRNA" database for most gene expression applications [43]. For broader coverage, "Refseq representative genomes" or "core_nt" are alternatives [41].

- Enable the option "Primer must span an exon-exon junction" when working with RNA/cDNA to prevent amplification of genomic DNA contaminants [41] [43]. Set the requirement for annealing to both exons at the junction.

- Execute and Analyze: Click "Get Primers" to submit. Primer-BLAST will return only primer pairs that are computationally predicted to be specific to your intended target [41]. Carefully review the output to confirm the primer binding locations and verify the in silico specificity.

Post-Design Validation

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Use tools such as the IDT OligoAnalyzer or the UNAFold Tool to check all selected primer pairs for self-dimers, cross-dimers, and hairpin structures [38]. Confirm that the ΔG values for any potential secondary structures are more positive than -9.0 kcal/mol [38].

- Experimental Validation: Always validate primer performance empirically using a dilution series to calculate amplification efficiency (target: 90–110%) [4]. Include melt curve analysis for SYBR Green-based assays to confirm a single, specific amplification product.

Advanced Applications and Reagent Solutions

For particularly challenging applications involving highly multiplexed PCR or superior SNP discrimination, specialized technologies and reagent systems have been developed.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Primer Applications

| Technology / Reagent | Primary Function | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Avoiding Molecular Recognition Systems (SAMRS) [39] | Nucleobase analogs that pair with natural bases but not with other SAMRS, reducing primer-dimer formation. | Highly multiplexed PCR; superior SNP discrimination in complex backgrounds. |

| PACE (PCR Allele Competitive Extension) [42] | Advanced allele-specific PCR chemistry for SNP and Indel detection using competitive primer extension. | High-throughput genotyping in agricultural, aquaculture, and clinical research; diagnostic assay development. |

| SADDLE Algorithm [44] | Computational algorithm for designing highly multiplexed PCR primer sets that minimize primer dimer formation. | Large NGS panels; multiplexed qPCR assays targeting dozens to hundreds of targets simultaneously. |

| Double-Quenched Probes [38] | qPCR probes with internal quenchers (ZEN/TAO) that lower background fluorescence and increase signal-to-noise. | Sensitive quantitative gene expression analysis; pathogen detection with improved quantification accuracy. |