A Comprehensive Guide to Chimera Detection and Removal in Sequencing Data: From Fundamentals to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chimera detection and removal in sequencing data, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to Chimera Detection and Removal in Sequencing Data: From Fundamentals to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chimera detection and removal in sequencing data, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational biology of chimeric RNAs and their significance in diseases like cancer, explores the latest computational methods and sequencing technologies enhancing detection capabilities, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies in data processing pipelines, and offers a comparative analysis of validation techniques and tool performance. By synthesizing current methodologies and challenges, this guide aims to support the development of robust, accurate, and clinically relevant genomic analyses.

Understanding Chimeras: Biological Origins and Significance in Genomic Research

Chimeric RNAs, hybrid transcripts composed of exons from two or more different genes, represent a fascinating and complex area of modern molecular biology [1]. Once considered primarily products of chromosomal rearrangements in cancer cells, these molecules are now recognized to occur in normal physiology and can arise through multiple biogenesis mechanisms [2] [3]. This expanding understanding has complicated their detection and analysis, requiring researchers to distinguish biologically relevant chimeric RNAs from technical artifacts that can arise during experimental procedures. The field faces the dual challenge of recognizing legitimate chimeric RNAs with potential functional significance while identifying and eliminating false positives generated through various technical processes.

For researchers working with sequencing data, this distinction is particularly crucial. Technical artifacts can originate from multiple sources including reverse transcription errors, PCR amplification biases, cross-contamination between samples, and bioinformatic misclassification [4] [5]. Meanwhile, authentic chimeric RNAs continue to be discovered in diverse biological contexts, with some playing roles in normal development and others contributing to disease processes [1] [2]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate these challenges, offering practical methodologies for accurate chimera detection and validation within the broader context of sequencing data research.

FAQs: Addressing Common Research Challenges

FAQ 1: What are the primary mechanisms that generate authentic chimeric RNAs?

Authentic chimeric RNAs arise through several distinct biological mechanisms:

DNA-Level Rearrangements: Traditional fusion genes result from chromosomal abnormalities including translocations, inversions, deletions, or tandem duplications [2] [3]. These events bring previously separate genes into proximity, enabling transcription of chimeric RNAs. The well-known BCR-ABL fusion in chronic myelogenous leukemia exemplifies this category [1] [2].

Trans-Splicing: This RNA-level mechanism joins exons from two separate pre-mRNA molecules [2] [3]. The JAZF1-JJAZ1 chimera, found in both normal endometrial cells and endometrial stromal sarcomas, represents a validated trans-splicing product that occurs without chromosomal rearrangement [2].

Cis-Splicing of Adjacent Genes (cis-SAGe): This process involves transcriptional readthrough where RNA polymerase continues past the normal termination signal of one gene into a neighboring gene, followed by splicing of the resulting transcript into a mature chimeric RNA [2] [3]. These chimeras typically occur between same-strand neighboring genes located within 30 kilobases of each other and often follow the "2-2 rule" (joining the second-to-last exon of the 5′ gene to the second exon of the 3′ gene) [3].

Cross-Strand Chimeric RNAs (cscRNAs): Recent research has identified chimeric RNAs formed from transcripts originating from opposite DNA strands [6]. These appear to be particularly prevalent in regions of convergent transcription and demonstrate tissue-specific expression patterns.

FAQ 2: How can I distinguish true biological chimeras from technical artifacts?

Distinguishing authentic chimeric RNAs from artifacts requires a multi-faceted approach:

Experimental Validation: Use independent methods such as RT-PCR with primers spanning the junction site followed by Sanger sequencing [2]. Northern blotting provides additional confirmation through size verification.

Genetic Evidence: For suspected contamination artifacts, examine SNP patterns. Authentic transcripts should match the host genotype, while contaminants may show discrepant SNPs [5]. This approach successfully identified cross-sample contamination in GTEx data through variant analysis.

Replication Across Platforms: Verify chimeric RNAs using different library preparation methods and sequencing platforms. Artifacts specific to certain protocols are less likely to replicate across methodologies.

Statistical Support: Implement rigorous bioinformatic filters requiring multiple supporting reads, proper pair alignment, and junction sequences consistent with known splicing patterns [7].

Biological Plausibility: Consider whether the chimera formation aligns with known biological mechanisms. Artifacts often lack conservation across samples or show expression patterns inconsistent with parental genes.

Technical artifacts in chimeric RNA detection arise from several sources:

Reverse Transcription Artifacts: The reverse transcriptase enzyme can template-switch between different RNA molecules, creating spurious chimeric sequences [4]. This frequently occurs at regions of short sequence homology (SHS) where the enzyme can dissociate from one template and continue synthesis on another.

PCR Recombination: During amplification, incomplete PCR products can act as primers on different templates, generating chimeric molecules [4] [7]. This is particularly problematic in high-cycle amplification and with fragmented templates.

Cross-Contamination: Sample-to-sample contamination can occur during library preparation or sequencing [5]. Highly expressed genes from one sample can appear as low-level signals in other samples processed simultaneously. The GTEx project documented this phenomenon, where pancreas-enriched genes (PRSS1, PNLIP) appeared in non-pancreas tissues sequenced on the same day [5].

Bioinformatic Misalignment: Computational pipelines may misalign reads across paralogous genes or to regions with repetitive elements, creating apparent chimeras [7].

Index Hopping: In multiplexed sequencing, index swapping between samples can assign reads to the wrong sample, creating apparent chimeric expression [5].

FAQ 4: Which computational tools are most effective for chimeric RNA detection?

Various computational tools have been developed for chimeric RNA detection, each with different strengths:

Table: Computational Tools for Chimeric RNA Detection

| Tool Name | Methodology | Key Features | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TopHat-Fusion [1] | Alignment-based | Discovers fusions from known and unknown genes | Comprehensive discovery |

| FusionHunter [1] | Paired-end analysis | Identifies fusion transcripts from RNA-seq reads | Cancer fusion detection |

| ChimeraScan [1] | High-throughput sequencing | Processes long paired-end reads; detects junction-spanning reads | Sensitive chimera detection |

| FusionSeq [1] | Paired-end RNA-seq | Includes filters to remove spurious candidates | High-specificity applications |

| cscMap [6] | Specialized pipeline | Specifically designed for cross-strand chimeric RNAs | Cross-strand fusion detection |

| CRAC [1] | Integrated analysis | Predicts splice junctions or fusion RNAs directly from RNA-seq | Direct RNA analysis |

FAQ 5: What experimental strategies can validate putative chimeric RNAs?

A robust validation pipeline incorporates multiple experimental approaches:

Junction-Specific RT-PCR: Design primers that span the unique junction sequence of the putative chimera. Follow with Sanger sequencing to confirm the exact fusion point [2].

Quantitative PCR: Develop qPCR assays targeting the chimera junction to quantify expression levels across different samples and conditions.

Northern Blot Analysis: Use junction-spanning probes to verify the size and integrity of the chimeric transcript, helping distinguish from PCR artifacts [2].

Mass Spectrometry: For chimeric RNAs with protein-coding potential, mass spectrometry can detect the predicted fusion protein, providing functional validation [1].

Single-Molecule Sequencing: Long-read technologies like PacBio or Nanopore can capture full-length transcripts, confirming the chimera structure without assembly.

Genetic SNP Validation: Compare SNPs in the chimeric RNA with the genomic DNA of the same sample to confirm they originate from the same individual [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Cross-Contamination in Sequencing Data

Cross-contamination between samples represents a significant challenge in chimeric RNA detection, as demonstrated by the systematic contamination found in GTEx datasets [5].

Table: Identifying and Resolving Sample Contamination

| Contamination Indicator | Detection Method | Resolution Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected tissue-specific genes | Co-expression clustering of highly expressed, tissue-enriched genes | Analyze sequencing batch effects; compare samples sequenced on same day |

| Genotype mismatches | SNP analysis comparing DNA and RNA variants | Verify sample identity; check for index hopping |

| Correlation with processing date | Metadata analysis of isolation/sequencing dates | Implement strict sample separation; use unique dual indices |

| Low-level expression of high-abundance genes | Expression outlier detection | Include negative controls; filter genes with inconsistent expression |

Workflow Implementation:

- Screen for highly expressed, tissue-enriched genes (e.g., pancreas: PRSS1, PNLIP, CLPS, CELA3A; esophagus: KRT4, KRT13) in unexpected tissues.

- Correlate findings with processing dates - contamination is strongly associated with samples sequenced on the same day as the source tissue.

- Perform SNP analysis on suspicious chimeric reads to confirm genotype mismatches.

- Implement batch correction in analysis or re-process affected samples with appropriate controls.

Guide 2: Optimizing Bioinformatics Pipelines for Accurate Detection

Proper bioinformatic processing is essential for distinguishing true chimeric RNAs from artifacts:

Critical Filtering Steps:

- Homology Filtering: Remove chimeras with short homologous sequences (SHS) at junction points, which often represent reverse transcription artifacts [4].

- Mapping Quality: Require unique alignment and proper pairing for supporting reads.

- Multiple Evidence: Set minimum thresholds for supporting reads (typically ≥3) and spanning multiple samples or replicates.

- Database Comparison: Check against databases of known artifacts and validated chimeras (ChiTaRS, ChimerDB) [1].

- Reading Frame Analysis: For coding chimeras, check if the junction maintains an open reading frame.

Guide 3: Validating Chimeric RNAs Through Experimental Approaches

Robust experimental validation is essential for confirming putative chimeric RNAs:

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Initial RT-PCR Screening

- Design primers spanning the predicted junction sequence

- Include controls: parental gene expression, no-template, and genomic DNA contamination check

- Use reverse transcriptases with lower template-switching activity

- Perform triplicate technical replicates

Sequence Verification

- Clone PCR products and sequence multiple clones

- Alternatively, use Sanger sequencing directly from PCR products

- Confirm the exact junction sequence matches bioinformatic predictions

Expression Pattern Analysis

- Perform quantitative RT-PCR across multiple tissue types or conditions

- Compare expression levels with parental genes

- Look for correlation with biological factors

Functional Validation

- For protein-coding chimeras: perform Western blot with junction-specific antibodies

- Implement knockdown using junction-targeting siRNAs or Cas13 systems [3]

- Assess phenotypic effects of overexpression and knockdown

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Chimeric RNA Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Junction-Specific Primers | Custom DNA oligos spanning fusion points | RT-PCR amplification of unique chimera sequence |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Superscript IV, LunaScript | High-fidelity reverse transcription with reduced template switching |

| CRISPR-Cas13 System [3] | Cas13a, Cas13b | Targeted degradation of chimeric RNA without affecting parental genes |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep Kits | Illumina TruSeq, NEBNext Ultra II | High-quality library preparation with minimal artifacts |

| Positive Control Plasmids | Synthetic chimera constructs with known sequence | Pipeline validation and positive control for detection methods |

| Chimera Databases | ChiTaRS [1], ChimerDB [1], FusionGDB [2] | Reference for known chimeras and filtering of common artifacts |

Advanced Detection Methodologies

Next-Generation Sequencing Analysis Protocols

Comprehensive RNA-Seq Analysis for Chimera Detection:

Library Preparation Considerations

- Use paired-end sequencing (minimum 2x75bp, preferably 2x150bp)

- Employ strand-specific protocols to determine origin

- Include technical replicates and control samples

- Use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish PCR duplicates

Bioinformatic Processing Pipeline

- Quality control: FastQC, MultiQC

- Adapter trimming: Trimmomatic, Cutadapt

- Alignment: STAR, HISAT2 (with chimeric alignment options)

- Chimera detection: Run multiple tools (see Table above) and take consensus

- Filtering: Remove low-complexity regions, simple repeats, and paralogous genes

Validation Integration

- Prioritize chimeras with junction reads in multiple samples

- Check for supporting evidence in public databases

- Correlate with potential biological functions

Specialized Techniques for Challenging Cases

Cross-Strand Chimeric RNA Detection: The cscMap pipeline specializes in identifying cross-strand chimeric RNAs (cscRNAs), which form between transcripts from opposite DNA strands [6]. Key considerations:

- Use strand-specific RNA-seq data

- Require both ends of paired-end reads to support the cross-strand junction

- Filter out potential reverse transcription artifacts through sequence analysis

- Validate recurrent cscRNAs across multiple samples

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Considerations: Chimeric RNA detection in single-cell data presents additional challenges:

- Higher amplification cycles increase PCR artifacts

- Multiplet events can create hybrid expression profiles

- Lower sequencing depth reduces detection sensitivity

- Implement specialized tools (e.g., scFusion) designed for single-cell data

Accurate detection of chimeric RNAs requires an integrated approach combining computational stringency with experimental validation. By understanding the multiple mechanisms that generate authentic chimeric RNAs and the technical artifacts that mimic them, researchers can develop more robust detection pipelines. The methodologies outlined in this technical support center provide a framework for distinguishing biological signals from technical noise, enabling more reliable discoveries in this rapidly evolving field.

As sequencing technologies continue to advance and our knowledge of transcriptome complexity expands, these troubleshooting approaches will help researchers navigate the challenges of chimera detection, ultimately leading to more accurate characterization of these fascinating hybrid molecules and their roles in health and disease.

FAQs: Understanding Biological Chimeras in Sequencing Data

1. What is the fundamental difference between a biological chimera and a sequencing artifact?

A biological chimera, such as a trans-spliced RNA or a gene fusion from a chromosomal rearrangement, is a true biological molecule present in the cell. In contrast, a sequencing artifact (like a PCR chimera) is an artificial molecule created during the laboratory preparation of sequencing libraries, primarily due to incomplete amplification or polymerase errors [8] [9]. Distinguishing between the two is critical, as a biological chimera may have functional significance in disease or development, while an artifact does not.

2. My RNA-Seq analysis detected a chimeric transcript. How can I determine if it resulted from trans-splicing?

Spliceosome-Mediated RNA Trans-Splicing (SMaRT) is a natural, though rare, process that joins exons from two separate pre-mRNA molecules [10] [11]. To investigate a putative trans-splicing event:

- Validate with PCR: Design primers that span the novel exon-exon junction and perform RT-PCR followed by Sanger sequencing.

- Examine genomic DNA: The definitive test is to check the corresponding genomic locus. If the chimeric exon structure is not present in the genome, it supports a post-transcriptional origin like trans-splicing [12].

- Consult databases: Check if the chimeric transcript is a known, annotated read-through fusion of adjacent genes [12].

3. What is a "read-through" fusion and how does it differ from a fusion caused by a chromosomal rearrangement?

A read-through fusion (or tandem chimerism) occurs when two consecutive genes on the same chromosome are transcribed into a single continuous RNA molecule without a DNA rearrangement [12]. In contrast, a fusion from a chromosomal rearrangement is caused by a physical breakage and rejoining of DNA, such as a translocation or inversion, that brings two previously separate genes into proximity [12]. While read-through fusions are common, their biological relevance is often limited compared to the well-documented driver role of many rearrangement-driven fusions like BCR::ABL1 [12].

4. Why does my 16S rRNA amplicon data have such a high proportion of chimeric reads?

High chimera rates in 16S sequencing are predominantly technical artifacts introduced during PCR amplification. This occurs when an incomplete DNA fragment from one organism acts as a primer on a template from another organism, leading to a hybrid amplicon [8] [9]. Common exacerbating factors include:

- High PCR cycle counts: More cycles increase the chance of incomplete extension.

- Poor template quality: Degraded DNA provides more incomplete fragments.

- Insufficient primer removal: Leaving primer sequences on reads can interfere with downstream denoising and increase false chimera detection [13].

- Complex microbial communities: Higher sample diversity provides more opportunities for cross-template priming.

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving High Chimera Rates

Problem: High Chimera Percentage in 16S Amplicon Sequencing

This is a common issue that can drastically inflate microbial diversity estimates by creating spurious "species" [8] [9].

Diagnosis Flowchart:

Recommended Actions:

- Action 1: Optimize Primer Removal. Primer sequences can interfere with the denoising algorithms used for chimera detection. Remove primers using a dedicated tool like

cutadaptbefore running denoising pipelines like DADA2. One study showed this can increase non-chimeric reads from 10-15% to 40-45% [13]. - Action 2: Reduce PCR Cycle Count. The number of PCR cycles is a major factor in chimera formation. Titrate your cycle number to use the minimum required for sufficient library yield [9].

- Action 3: Use a Robust Chimera Detection Tool. Employ specialized tools designed to identify and remove chimeric sequences. The table below benchmarks several common methods.

Table 1: Benchmarking of Chimera Detection and Denoising Algorithms for 16S Data [8] [9]

| Tool/Method | Type | Key Principle | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCHIME | Chimera Detection | Uses a reference database or abundance-based de novo discovery. | >1000x faster than ChimeraSlayer; high sensitivity, especially with short, noisy sequences [8]. |

| DADA2 | Denoising (ASV) | Implements an iterative process of error estimation to infer true biological sequences. | Produces consistent output but can over-split 16S rRNA gene copies from the same strain [9]. |

| Deblur | Denoising (ASV) | Uses a pre-calculated statistical error profile to correct sequences. | Reduces errors by applying a position-specific error model [9]. |

| UNOISE3 | Denoising (ASV) | Compares read abundance to similar sequences using a probabilistic model. | Effectively clusters reads by assessing substitution and insertion probabilities [9]. |

| UPARSE | Clustering (OTU) | Greedy clustering algorithm to group reads into OTUs. | Achieves clusters with lower errors but may over-merge distinct biological sequences [9]. |

Problem: Distinguishing Biological vs. Technical Chimeras in RNA-Seq

Diagnosis Strategy: Confirming a biological chimera requires multiple lines of evidence to rule out technical artifacts.

- Step 1: Independent Validation. Use a non-sequencing based method such as RT-PCR with primers spanning the fusion junction and Sanger sequencing. This confirms the physical existence of the transcript independent of NGS library construction [14].

- Step 2: Genomic DNA Correlation. For suspected gene fusions from rearrangements, perform PCR on genomic DNA. The presence of the junction in genomic DNA confirms a DNA-level rearrangement [12].

- Step 3: Re-analysis with Specialized Tools. Re-process raw sequencing data using fusion-finding algorithms that are designed to account for sequencing errors and mapping artifacts.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating a Putative Trans-Splicing Event

Objective: To confirm a putative trans-spliced RNA molecule identified from RNA-Seq data.

Materials:

- RNA Sample: Total RNA from the original tissue or cell line.

- Reverse Transcriptase: For cDNA synthesis.

- Junction-Specific Primers: Forward primer in the 5' gene partner, reverse primer spanning the novel exon-exon junction of the 3' partner.

- PCR Reagents: High-fidelity DNA polymerase.

- Sanger Sequencing Services.

Methodology:

- cDNA Synthesis: Convert total RNA to cDNA using a reverse transcriptase kit with random hexamers and/or oligo-dT primers.

- Junction PCR: Perform PCR amplification using the junction-specific primers and the synthesized cDNA as template.

- Positive Control: Primers for a constitutively expressed housekeeping gene.

- Negative Control: No-template control (NTC) for the junction-specific primers.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Analyze the PCR products on an agarose gel. A single, discrete band of the expected size is a positive indicator.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Purify the PCR product and submit it for Sanger sequencing. Analyze the returned chromatogram to visually confirm the precise nucleotide sequence at the junction [14]. The text file must match the predicted exon-exon junction from the RNA-Seq data.

Protocol 2: Differentiating a Read-Through from a Rearrangement Fusion

Objective: To determine the genomic basis of a chimeric RNA.

Materials:

- Genomic DNA (gDNA): Isolated from the same sample as the RNA.

- Junction-Specific Primers: The same primers used for RNA validation in Protocol 1.

- PCR Reagents: High-fidelity DNA polymerase.

- Sanger Sequencing Services.

Methodology:

- gDNA PCR: Use the junction-specific primers from the RNA validation to perform PCR on the gDNA sample.

- Interpretation of Results:

- No PCR Product from gDNA: This suggests the chimera is a result of a post-transcriptional event, such as trans-splicing [12].

- PCR Product from gDNA: This confirms a DNA-level event. Sequence the product.

- If the sequenced gDNA product shows the genes are fused in their natural genomic order with no intervening sequence, it is consistent with a read-through transcription event [12].

- If the sequenced gDNA product shows a junction that is not present in the reference genome, it confirms a genomic rearrangement (e.g., translocation, inversion) [12].

Table 2: Interpretation Guide for Fusion Validation Experiments

| Observation | RNA PCR | gDNA PCR | Likely Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Positive | Negative | Post-transcriptional (e.g., Trans-splicing) |

| 2 | Positive | Positive (genes in order) | Read-Through Transcription |

| 3 | Positive | Positive (genes rearranged) | Chromosomal Rearrangement |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Chimera Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Reduces PCR errors and artifact formation during library amplification and validation. | Kits from suppliers like QIAGEN, NEB, or Thermo Fisher. |

| cutadapt | Software for removing primer/adapter sequences from NGS reads. | Critical pre-processing step to improve denoising and reduce false chimera calls [13]. |

| DADA2 | R package for modeling and correcting Illumina-sequenced amplicon errors. | Denoises sequences to resolve Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [9]. |

| UCHIME | Algorithm for detecting chimeric sequences in amplicon data. | Can be run in de novo mode or with a reference database [8]. |

| Sanger Sequencing | The gold standard for validating novel nucleic acid sequences. | Used to confirm the sequence of fusion junctions discovered by NGS [14]. |

In biomedical research, a "chimera" refers to a single biological entity containing cells or genetic material from at least two different origins. In the context of sequencing data, chimeric sequences are artificial constructs formed during laboratory processes, primarily polymerase chain reaction (PCR), where incomplete amplification products from different templates join together to create a single, misleading sequence. These artifacts are particularly problematic in amplicon sequencing studies, such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing for microbiome analysis, where they can significantly inflate diversity estimates and lead to the false detection of non-existent species [15].

Beyond these technical artifacts, naturally occurring microchimerism (MC) represents a clinically relevant form where individuals harbor a small population of cells from another genetically distinct individual. This phenomenon is most commonly acquired through pregnancy, with fetal cells persisting in the maternal body or maternal cells in the offspring, though it can also occur through blood transfusions or organ transplants [16]. Research has linked microchimerism to a diverse range of health effects, functioning both as a biomarker and potential driver in conditions including cancer, autoimmune diseases, and tissue repair processes [16].

This technical support guide addresses the critical challenges of chimera detection and removal in sequencing data research, providing troubleshooting guidance and methodological frameworks to ensure data accuracy in studies investigating the role of chimeras in human disease.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary sources of chimeric sequences in amplicon sequencing data?

Chimeric sequences predominantly form during the PCR amplification process. Template switching occurs when an incomplete DNA extension product from one round of amplification acts as a primer in a subsequent cycle, annealing to and extending from a different template sequence. This issue is exacerbated with longer amplicons, as the probability of incomplete synthesis increases with amplicon length. Additionally, chimeras can form post-amplification during library preparation steps, such as adapter ligation in Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) workflows [15].

Q2: Why is primer removal often recommended before chimera detection in workflows like DADA2?

Primer removal prior to denoising can significantly improve chimera detection efficacy. Empirical evidence shows that removing primers using tools like cutadapt before running qiime dada2 denoise-paired can increase the percentage of reads identified as non-chimeric from 10-15% to 40-45% in gut microbiome datasets [13]. This improvement likely occurs because residual primer sequences interfere with the accurate alignment and comparison of reads during the denoising process, which is fundamental to identifying and removing chimeric artifacts.

Q3: How can I analyze chimeric sequences in specialized applications like AAV capsid engineering?

For analyzing chimeric adeno-associated virus (AAV) libraries created through directed evolution, specialized tools like hafoe have been developed. This command-line tool performs "neighbor-aware serotype identification" by chopping variant sequences into overlapping fragments (default: 100 bp with 10 bp overlap), aligning them to parental serotype genomes, and using neighborhood context to assign the most probable parental origin to each fragment. This approach accurately identifies parental serotype compositions with 96.3% to 97.5% accuracy and can process hundreds of thousands of variants simultaneously [17].

Q4: What are the consequences of failing to remove chimeric sequences from my dataset?

Failure to adequately remove chimeric sequences leads to several critical data quality issues:

- Inflated Diversity Estimates: Chimeras appear as novel sequences, artificially increasing observed alpha diversity metrics.

- Skewed Community Structure: The false taxa detected can distort the true biological composition of samples.

- Reduced Statistical Power: The introduction of artifactual sequences adds noise to datasets, potentially obscuring true biological signals.

- Compromised Downstream Analyses: All subsequent analyses, including differential abundance testing and biomarker discovery, will be based on contaminated data [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Chimera Rates in Full-Length 16S rRNA Nanopore Sequencing

Problem: After performing full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing with Oxford Nanopore Technology, an unexpectedly high proportion of reads are identified as chimeric, compromising data integrity.

Solution: Implement a consensus-based approach with robust chimera detection:

Sequence Preprocessing:

- Filter reads by length to remove fragments outside the expected amplicon size distribution.

- Identify and trim primer sequences using tools like

primer-chop. - Retain only the highest quality reads (top 80% with fewest expected errors) using

Filtlong[15].

Consensus Generation & Chimera Detection:

- Cluster quality-filtered reads based on k-mer composition (e.g., 3mer) using UMAP-OPTICS.

- Generate a consensus sequence for each cluster using

lamassemble. - Perform initial chimera detection on consensus sequences using

vsearch uchime_denovo, flagging "local chimeric sequences" [15].

Cross-Sample Validation:

- Deduplicate consensus sequences across all samples.

- Map original reads back to the consensus sequences with

minimap2. - Identify "global chimeric sequences" based on mapping patterns across samples and remove them from the final dataset [15].

Tool Recommendation: The CONCOMPRA workflow is specifically designed for this purpose and has demonstrated superior performance for profiling bacterial communities using full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing [15].

Issue: Persistent Chimeras After Standard DADA2 Processing

Problem: Standard DADA2 denoising pipelines yield low percentages of non-chimeric reads, even after adjusting standard truncation parameters.

Investigation and Resolution Steps:

Verify Primer Removal:

- Confirm complete primer removal using

cutadaptwith appropriate parameters before DADA2 denoising. - Use

qiime demux summarizeon both input and output ofcutadaptto visually verify primer trimming [13].

- Confirm complete primer removal using

Adjust DADA2 Parameters:

- Use

trim-left-fandtrim-left-rparameters instead of, or in combination with, truncation parameters to remove primer residues from the 5' end. - Avoid overly aggressive truncation lengths (

trunc-len) that may discard excessive sequence data while attempting to resolve chimera issues [13].

- Use

Evaluate Alternative Trimming Strategies:

- Test the impact of using default DADA2 denoising parameters after primer removal, as this has been observed to increase non-chimeric read retention in some cases [13].

Issue: Analyzing Complex Chimeric AAV Libraries

Problem: Standard alignment tools are inadequate for deciphering the parental composition and enrichment patterns of chimeric AAV variants from DNA shuffling experiments.

Recommended Workflow with hafoe:

Input Preparation:

- Prepare a FASTA file containing the

capgene sequences of all parental AAV serotypes used in library construction. - Provide sequencing reads (FASTQ/CSV) of the chimeric library, plus additional files for any enriched libraries from selection cycles [17].

- Prepare a FASTA file containing the

Preprocessing and Clustering:

- Filter sequences by length and identify open reading frames (ORFs), retaining only variants with ORF size >1.8 kb and total length <3 kb.

- Reduce sequence redundancy using CD-HIT-EST clustering at 90% similarity threshold, selecting the most abundant sequence as cluster representative [17].

Parental Deconvolution:

- Allow

hafoeto automatically fragment sequences and perform neighbor-aware serotype identification. - Review interactive graphical reports to analyze recombination patterns and parental segment contributions to enriched variants [17].

- Allow

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Validation of Chimera Detection Methods Using Synthetic Communities

Purpose: To empirically evaluate the performance (sensitivity and specificity) of any chimera detection tool using a mock microbial community with known composition.

Reagents and Materials:

- Commercially available synthetic bacterial community DNA (e.g., ATCC MSA-1002)

- Appropriate primers for target amplicon (e.g., full-length 16S rRNA gene primers 27F/1492R)

- PCR master mix (e.g., Phire Tissue Direct PCR Master Mix)

- Oxford Nanopore PCR Barcoding Expansion Pack (EXP-PBC096)

- ONT ligation sequencing kit (SQK-LSK109 or SQK-LSK114)

- ONT flow cells (R9.4.1 or R10.4.1) [15]

Procedure:

- Amplification: Amplify the target gene from the synthetic community DNA using standardized PCR conditions.

- Library Preparation: Perform barcoding and library preparation according to ONT's "Amplicon by Ligation" protocol. Include multiple independent amplification replicates (n=4) to assess technical variability.

- Sequencing: Sequence the pooled library on appropriate ONT flow cells, basecalling with a super-accurate model (e.g., Guppy).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process the resulting FASTQ files through the chimera detection tool being validated (e.g., CONCOMPRA, DADA2, etc.).

- Validation: Compare the tool's output to the known composition of the synthetic community. Calculate performance metrics including:

- Recall: Proportion of actual true sequences correctly identified as non-chimeric.

- Precision: Proportion of sequences identified as non-chimeric that are true sequences.

- False Discovery Rate: Proportion of sequences identified as non-chimeric that are actually chimeric.

Protocol: Chimera Analysis in AAV Directed Evolution

Purpose: To identify and characterize enriched chimeric AAV capsid variants with improved tropism for specific target tissues.

Reagents and Materials:

- DNA-shuffled AAV capsid library

- Target cells (e.g., human dermal fibroblasts, dendritic cells) or tissues (e.g., canine muscle, liver)

- PacBio or Oxford Nanopore sequencing platform

hafoecomputational tool [17]

Procedure:

- Library Selection: Apply the chimeric AAV library to target cells or tissues in vitro or in vivo. Allow binding and internalization.

- Variant Recovery: Isclude genomic DNA from target cells/tissues and recover enriched AAV variants by PCR amplification of capsid regions.

- Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from both the initial unselected library and the enriched pools. Sequence using long-read technology (PacBio CCS or ONT).

- Bioinformatic Analysis with

hafoe:- Run

hafoewith the parental serotype FASTA file and sequencing data from both unselected and enriched libraries. - Use the tool's clustering and neighbor-aware identification to determine parental recombination patterns in enriched variants.

- Generate interactive reports to visualize segment contributions from different parental serotypes.

- Run

- Variant Characterization: Select highly enriched chimeric variants for downstream functional validation in secondary assays to confirm improved tropism properties.

Data Presentation

Performance Comparison of Chimera Detection Tools

Table 1: Evaluation of chimera detection tools using a synthetic bacterial community (16S MOCK) with known composition.

| Tool Name | Principle/Method | Reference Database Dependent? | Reported Non-Chimeric Reads | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONCOMPRA | Consensus sequencing & mapping | No | ~40-45% [15] | Works without reference databases; suitable for novel organisms | Requires careful parameter optimization |

| DADA2 | Error model-based denoising | Implicitly, during training | 10-45% [13] (highly dependent on primer removal) | Integrated into QIIME2; high sensitivity | Performance drops without proper primer trimming |

| hafoe | Neighbor-aware serotype identification | Yes (parental sequences) | N/A (for AAV-specific use) | Accurate parental deconvolution (96.3-97.5%); processes large datasets [17] | Specific to engineered chimeric libraries |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key reagents and computational tools for chimera-related research.

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Bacterial Community (ATCC MSA-1002) | Biological Standard | Validation control for chimera detection methods | Benchmarking performance of bioinformatic tools against known ground truth [15] |

| Oxford Nanopore PCR Barcoding Kit | Laboratory Reagent | Barcoding amplicons for multiplexed sequencing | Preparing full-length 16S rRNA libraries for microbiome analysis [15] |

| CONCOMPRA | Computational Tool | Detects chimeras by drafting and mapping to consensus sequences | Profiling bacterial communities with long-read amplicon sequencing [15] |

| hafoe | Computational Tool | Exploratory analysis of chimeric AAV libraries | Identifying parental serotype composition in directed evolution experiments [17] |

| DADA2 | Computational Tool | Sequence denoising and chimera removal | 16S rRNA amplicon analysis in QIIME2 workflows [13] |

| Cutadapt | Computational Tool | Primer and adapter removal from sequencing reads | Preprocessing step to improve downstream chimera detection in DADA2 [13] |

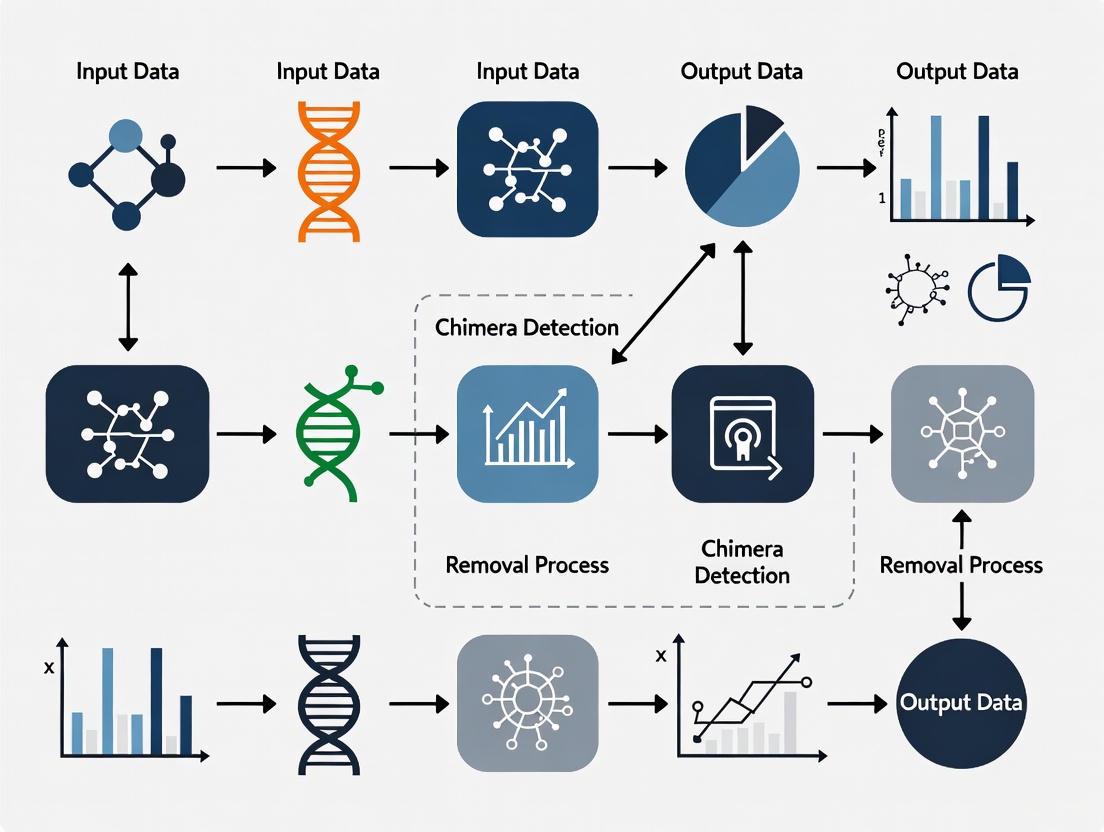

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Workflow for Comprehensive Chimera Detection in Amplicon Sequencing

Chimera Detection Workflow in Amplicon Sequencing

Workflow for Analyzing Chimeric AAV Variants

Chimeric AAV Variant Analysis Workflow

In molecular biology, a chimera is a single DNA sequence originating from two or more parent sequences that have joined together during experimental processes such as PCR amplification [18]. These artifacts form when an incompletely extended DNA strand dissociates from its template and anneals to a different, but similar, template in a subsequent PCR cycle, acting as a primer to create a hybrid sequence [19] [18] [20].

Undetected chimeras pose a significant threat to data integrity. In adaptive immune receptor repertoire sequencing (AIRR-seq), they can be misinterpreted as sequences with high somatic hypermutation, potentially leading to the wasteful prioritization of artifactual sequences for further phenotypic characterization [19]. In metabarcoding studies, they inflate perceived microbial diversity by appearing as novel sequences that do not match any known organism, thus confounding ecological interpretations [18] [21].

FAQs on Chimera Fundamentals

1. What is the fundamental difference between a PCR chimera and a chimeric read? A PCR chimera is an artificial sequence formed during the amplification process and is generally considered an artifact that should be filtered out [18]. A chimeric read, however, is a sequencing read where subsections align to different genomic locations. These are not always artifacts and are often used by structural variant callers to detect real biological rearrangements [18] [21].

2. In which research areas are chimeras considered problematic artifacts? Chimeras are primarily problematic in amplicon sequencing studies, including:

- 16S rRNA metabarcoding for microbial community analysis [18] [21].

- Adaptive Immune Receptor Repertoire sequencing (AIRR-seq) for studying B and T cell receptors [19].

- Any PCR-based assay where mixed templates are amplified, as they can generate false-positive variants or overestimate diversity [20].

3. Can chimeras ever be biologically relevant? Yes, in a different context. The deliberate creation of artificial chimeras is a useful tool in protein engineering and drug discovery. For example, proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) are engineered molecules designed to degrade specific disease-causing proteins [22]. This article, however, focuses on chimeras as sequencing artifacts.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High Chimera Rates in Amplicon Sequencing Data

Problem: Your amplicon sequencing data (e.g., 16S rRNA, AIRR-seq) shows an unexpectedly high number of chimeric sequences upon analysis with tools like DADA2 or VSEARCH.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive PCR Cycles | Review your library preparation protocol. Higher cycle numbers correlate with increased chimera formation [19]. | Minimize the number of PCR cycles. Use only the cycles necessary to generate sufficient material for sequencing [19] [23]. |

| Poor DNA Template Quality | Check the quality of your input DNA/RNA using electrophoregrams (e.g., RIN) or spectrophotometers (e.g., A260/A280) [24]. | Use high-quality, intact starting material. Degraded DNA can generate more partial fragments that act as primers for chimera formation [24]. |

| Overly Complex Template Mixture | Consider the natural complexity of your sample. Mixed-template amplifications are notoriously prone to chimera generation [20]. | Optimize template concentration. There is no direct fix, but be aware that environmental samples with vast diversity have higher inherent chimera rates (up to 30%) and require rigorous bioinformatic filtering [20]. |

Guide 2: Resolving Discrepancies in Chimera Detection Across Tools

Problem: Different chimera detection tools (e.g., UCHIME, DADA2, DECIPHER) report different numbers of chimeras for the same dataset.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Different Algorithmic Approaches | Identify whether the tools used are de novo (compare sequences within your dataset) or reference-based (compare to a curated database) [25]. | Understand the tool's methodology. De novo methods assume more abundant sequences are correct, while reference-based methods are more accurate if a comprehensive database is available. Use the method best suited for your amplicon and reference database completeness [25] [20]. |

| Varying Default Stringency Parameters | Check the default parameters for each tool, such as minimum parent abundance and minimum fold-parent over-abundance [26]. | Use consistent and justified parameters. When comparing tools, adjust key parameters to be as similar as possible. For final analysis, select a threshold that balances false positives and false negatives for your specific research goal [19] [26]. |

Experimental Protocols for Chimera Detection and Validation

Protocol 1: De Novo Chimera Detection with VSEARCH

This protocol is ideal for metabarcoding studies where a comprehensive reference database is not available [25].

Methodology:

- Input Data: Prepare a FASTA file containing unique sequences (Amplicon Sequence Variants - ASVs) from your dataset. This file is typically generated after denoising and quality filtering steps.

- Command Execution: Run the

uchime3_denovoalgorithm in VSEARCH. - Output: The algorithm compares all ASVs against one another, looking for subregions that match different, more abundant "parent" sequences. Sequences identified as chimeras are excluded from the output file

output_nonchimeras.fasta[25].

Protocol 2: Reference-Based Chimera Detection

This method is more accurate when a high-quality, curated reference database exists for your target gene (e.g., the 16S rRNA database) [20].

Methodology:

- Inputs: You will need your ASV FASTA file and a reference database FASTA file (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes for 16S rRNA).

- Command Execution: Run a reference-based algorithm like

uchime2_ref(as used by NCBI) or the reference mode in VSEARCH/USEARCH. - Output: The tool checks if each query sequence can be reconstructed as a chimera of two or more closer-matching reference sequences. Sequences flagged as chimeric are removed [20].

Protocol 3: Sample-Specific Chimera Detection with DADA2

The DADA2 pipeline incorporates a consensus de novo method that performs chimera detection sample-by-sample for increased accuracy [26].

Methodology (R code):

- Input Data: A sequence table (ASV table) where rows are samples and columns are amino acid sequences, generated after the DADA2 denoising step.

- Command Execution: Use the

removeBimeraDenovofunction with the "consensus" method. - Output: The function identifies sequences that are flagged as chimeric in a large fraction of samples. This consensus approach provides a robust final ASV table for downstream ecological analysis [26].

Quantitative Data on Chimera Formation

Table 1: Chimera and Error Rates Across Experimental Conditions

The following table summarizes quantitative findings on chimera formation from controlled studies, highlighting the impact of different protocols and sequencing platforms.

| Experimental Condition | Metric | Value | Context & Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Cycle Number | Chimera Formation Rate | Positive Correlation | Increasing PCR cycles leads to a higher rate of chimera formation [19]. |

| Sequencing Platform (Mock Community) | Index Misassignment / False Positive Reads | 5.68% (NovaSeq 6000) vs. 0.08% (DNBSEQ-G400) | Comparison using a commercial mock microbial community [21]. |

| Library Preparation Method (RAD-seq) | Misassigned Reads | 1.15% (Type B: Pooled PCR) vs. 0.65% (Type A: Individual PCR) | Type B libraries (pooled before PCR) showed a higher percentage of misassigned reads [23]. |

| Mixed-Template Amplification (16S rRNA) | Estimated Chimera Rate | Up to 30% | Environmental samples with mixed templates are highly susceptible to chimera formation [20]. |

Workflow Visualization

Chimera Detection and Removal Workflow

PCR Chimera Formation Mechanism

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Chimera Management

This table lists key software tools and their primary function in detecting and removing chimeric sequences from sequencing data.

| Tool Name | Function | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| UCHIME / VSEARCH | De Novo & Reference-Based Detection | Widely used algorithm available in both USEARCH and VSEARCH for identifying chimeras by comparing sequences within a dataset or against a reference database [18] [25]. |

DADA2 (removeBimeraDenovo) |

De Novo Detection | An R package that uses a de novo method to identify chimeras by comparing ASVs to more abundant "parent" sequences, often used as part of its broader amplicon analysis pipeline [26]. |

| DECIPHER | Reference-Based Detection | A tool that uses a search-based approach for chimera identification for 16S rRNA sequences [18]. |

| CHMMAIRRa | Domain-Specific Detection | A hidden Markov model (HMM) designed specifically for detecting chimeras in Adaptive Immune Receptor Repertoire (AIRR-seq) data, incorporating models for somatic hypermutation [19]. |

| CATCh | Ensemble Classification | An ensemble classifier for chimera detection in 16S rRNA sequencing studies, designed to improve detection accuracy [18]. |

Detection Methodologies: Computational Tools and Advanced Sequencing Technologies

Chimeras are artifact sequences formed by two or more biological sequences incorrectly joined together. This occurs predominantly during Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification of mixed templates, such as those from uncultured environmental samples. During PCR, incomplete extensions allow partially extended strands from one template to bind to a different, but similar, sequence in a subsequent cycle. This strand then acts as a primer, extending to form a new, chimeric sequence that is amplified in later cycles. This end result is a PCR artifact that does not represent a biologically existing sequence [20].

The presence of chimeras poses a significant problem for sequence analysis. Studies estimate that in mixed-template environmental samples, as many as 30% of sequences may be chimeric [20]. While most common in mixed templates, chimeras also occur at a lower frequency in amplifications from supposedly pure cultures. These artifacts corrupt data integrity, leading to the inference of false taxa, spurious Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), and degraded diversity estimates, ultimately resulting in inaccurate representations of biological diversity [20].

Algorithm Classifications and Methodologies

Chimera detection tools can be broadly categorized into two methodological approaches: reference-based and de novo detection. The choice of algorithm is critical and depends on the availability of a high-quality reference database, the sequencing technology used, and the specific research context.

Reference-Based Detection

Reference-based methods require a curated, high-quality database of non-chimeric sequences to identify chimeras by comparing query sequences against known parents.

- UCHIME: A widely used algorithm available in both reference and de novo modes. In its reference-based mode, it identifies a query sequence as chimeric if it can be divided into segments, each matching a different reference sequence (the "parents") more closely than any single reference sequence matches the entire query. The Uchime2_ref implementation is used by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) to scan 16S rRNA sequences. NCBI has optimized its parameters to find chimeras that are >3% diverged from the closest parent, as these tend to produce spurious OTUs [20].

- ChimeraSlayer: Another reference-based tool designed for detecting chimeras in 16S and ITS amplicon data. It uses a broad database and is designed to be sensitive to chimeras even when evolutionary distances between parents are close [27].

De Novo Detection

De novo methods do not require a reference database. Instead, they leverage the properties of the dataset itself, such as relative sequence abundance or read-to-read alignments, to identify chimeric sequences.

- UCHIME (de novo mode): This mode uses the abundance of sequences in the sample to infer chimeras. The underlying principle is that a chimeric sequence, being an artifact, is likely to be less abundant than its true biological parents. It identifies potential chimeras by looking for sequences that can be reconstructed from more abundant "parent" sequences within the same sample [27].

- YACRD (Yet Another Chimeric Read Detector): A standalone tool designed specifically for long-read technologies like nanopore sequencing. YACRD uses a de novo approach by requiring an overlap alignment file between reads. It does not need a reference genome but, in practice, requires high sequencing coverage to be effective, making it less suitable for low-coverage applications such as metagenomics [27].

- MiniScrub: This tool performs "read scrubbing" for nanopore reads, a process that removes low-quality segments which often include chimeric regions. The goal is to improve the accuracy of downstream analyses like genome assembly [27].

Comparison of Key Algorithms

Table 1: Overview of Common Chimera Detection Tools

| Tool Name | Detection Method | Primary Application | Key Requirement | Notable Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCHIME [20] [27] | Reference-based & De novo | 16S rRNA, ITS amplicons | Reference database (ref-mode) or abundance data (de novo) | NCBI uses optimized version for 16S screening |

| ChimeraSlayer [27] | Reference-based | 16S rRNA, ITS amplicons | Curated reference database | Sensitive to chimeras from closely related parents |

| YACRD [27] | De novo | Nanopore reads | Overlap file from read mapping (high coverage) | Designed for long-read technologies |

| MiniScrub [27] | De novo | Nanopore reads | Overlap file from read mapping | Removes (scrubs) chimeric and low-quality segments |

| Alvis [27] | Alignment-based visual detection | Long reads, assemblies | Read-to-reference alignment file (e.g., PAF, SAM) | Generates visual diagrams to identify chimeric breaks |

Experimental Protocols for Chimera Detection

Standard Operating Protocol: Reference-Based Detection with UCHIME

This protocol outlines the steps for using a reference-based algorithm like UCHIME to detect chimeras in a set of amplicon sequences.

1. Input Data Preparation:

- Query Sequences: The file containing the demultiplexed amplicon sequences to be checked (e.g., in FASTA or FASTQ format).

- Reference Database: A high-quality, curated database of non-chimeric sequences relevant to the study (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes for 16S rRNA). Ensure the database is formatted for use with the specific tool.

2. Algorithm Execution:

- Run the UCHIME algorithm in reference database mode (

uchime2_ref). - Specify the input query file and the reference database file.

- Set key parameters. For example, following NCBI's optimization:

min_div: 3.0 (to flag chimeras >3% diverged from parents) [20].- Other parameters can be left as default or adjusted based on the specific tool's documentation and the user's requirements for sensitivity.

3. Output Interpretation:

- The tool will generate an output file listing the sequences flagged as chimeric.

- The output typically includes the identified "parent" sequences and the estimated breakpoint where the chimera is formed.

- The standard practice is to remove all sequences identified as chimeric from downstream analyses to prevent data pollution [20].

Workflow: Integrated Chimera Detection and Validation

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for processing sequencing data, incorporating both reference-based and de novo chimera detection checkpoints.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why are a very high percentage (e.g., >90%) of my reads being reported as chimeric? This is a common issue, particularly with complex samples or specific sequencing technologies. Potential causes and solutions include:

- Low Sequence Quality: Noisy data with a high error rate can be misinterpreted as chimeric. Inspect your read quality profiles (e.g., average Phred scores). For PacBio data, samples with an average quality of Q25 showed much higher chimera flagging rates than those with Q36 [28].

- Suboptimal Filtering: Overly stringent or lenient filtering before denoising can exacerbate the problem. Adjust trimming and filtering parameters to remove truly low-quality sequences before they reach the chimera detection step [28].

- Incomplete Reference Sequences: If using a reference-based method, an incomplete or poorly curated database can lead to false positives. One user observed that having incomplete 16S sequences in the reference caused the algorithm to consistently report normal reads as chimeras, with breakpoints near the end of the short references. Removing these incomplete sequences significantly reduced false positives [29].

Q2: In a tool like QIIME2, I set the chimera method to 'none', but many reads are still not output. Are chimeras still being removed? Not necessarily. In this context, the "non-chimeric" output count often simply represents the final number of reads that passed all previous stages of the pipeline (filtering, denoising). A low output count is typically due to heavy read loss at the filtering or denoising steps, not chimera removal. This indicates underlying issues with read quality or suboptimal parameter settings for the specific dataset [28].

Q3: Are chimeras only a problem for short-read amplicon studies? No. While prevalent in 16S and ITS amplicon studies, chimeras are also a significant concern in long-read sequencing. For nanopore reads, chimeras can be formed by the ligation of two distinct molecules during library preparation or formed in silico by base-calling software when two molecules are sequenced in the same pore in quick succession. A recent study found that at least 1.7% of nanopore reads contain post-amplification chimeric elements, necessitating the use of specialized tools like YACRD or MiniScrub [27].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Chimera Detection

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High False Positive Rate | Reference database contains incomplete or poor-quality sequences. | Curate or switch to a high-quality, complete reference database. Remove partial sequences [29]. |

| High False Positive Rate | Algorithm parameters are too sensitive for the dataset. | Adjust sensitivity parameters (e.g., increase the minimum divergence threshold) [20]. |

| High False Negative Rate | Algorithm parameters are not sensitive enough. | Use more stringent parameters or a different algorithm. Consider the de novo approach if a reference is lacking. |

| Poor Performance on Long Reads | Using a tool designed for short-read amplicons. | Switch to a tool specifically designed for long reads, such as YACRD or MiniScrub [27]. |

| Low Number of Output Reads | Underlying sequence quality is poor, leading to loss before chimera check. | Inspect raw read quality (e.g., Phred scores). Optimize trimming and filtering parameters prior to denoising and chimera detection [28]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Resources for Chimera Detection Experiments

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Reference Database | A collection of verified, high-quality non-chimeric sequences used as a ground truth for reference-based detection. | SILVA, Greengenes, or UNITE databases for 16S/ITS rRNA gene amplicon analysis [20] [29]. |

| Negative Control (Mock Community) | A synthetic sample containing known, predefined sequences. Used to empirically assess error rates and chimera formation in the wet-lab workflow. | Sequencing a mock community allows benchmarking of the chimera detection pipeline's accuracy under controlled conditions [29]. |

| Alignment Visualization Tool | Software that generates visual diagrams of read-to-reference alignments to manually inspect potential chimeric breaks. | Alvis software can load alignment files (e.g., from minimap2) and highlight chimeric queries, providing a visual confirmation of automated results [27]. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | A PCR enzyme with high processivity and proofreading activity, reducing the rate of incomplete extensions that lead to chimera formation. | Using a high-fidelity polymerase during the amplification step is a preventative measure to minimize the creation of chimeras [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our lab is new to fusion gene detection. We tried multiple tools on the same RNA-seq dataset, but the results have very little overlap. Why does this happen, and how should we interpret these findings?

Different tools report different fusions due to variations in algorithms, alignment methods, and annotation databases [30]. To improve reliability, run multiple tools and consider fusions detected by more than one as higher confidence [30]. FusionCatcher uses a multi-aligner strategy (BOWTIE, BLAT, STAR) to overcome limitations of single-algorithm approaches [31].

Q2: When using ChiTaH for identifying known chimeras, what constitutes a "known" chimera, and what are the key advantages of this reference-based approach?

ChiTaH uses a reference database of 43,466 non-redundant known human chimeras to map sequencing reads [32]. This strategy offers superior speed and accuracy for identifying these specific sequences compared to de novo prediction tools, making it ideal for clinical diagnostics of known cancer fusions like BCR-ABL1 [32].

Q3: We are using DADA2 for amplicon sequencing analysis. Does it correct for PCR errors, or only sequencing errors? We are observing more ASVs than expected.

DADA2's core algorithm corrects sequencing errors using a parametric error model learned from your data [33]. It does not specifically correct for PCR errors. The observed high number of ASVs could be due to biological sequence variation or the presence of true sequence variants. It is recommended to rely on the max-ee parameter (maximum expected errors) for quality filtering rather than truncating based on quality scores alone, as this allows DADA2 to more effectively distinguish between true biological variation and errors [34].

Q4: For FusionCatcher, should we pre-trim adapters and quality-trim our raw FASTQ files before running the analysis?

No. Do not pre-trim your FASTQ files before running FusionCatcher [31]. The tool performs its own intelligent quality filtering and adapter removal, which is optimized for fusion detection. Pre-trimming can reduce sensitivity by shortening RNA fragment lengths, which are crucial for accurately identifying fusion junctions [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Sensitivity in Chimera Detection with ChimPipe

Problem: ChimPipe is reporting very few or no chimeric transcripts, even in samples where fusions are suspected.

Solution:

- Verify Input Data: Ensure you are using paired-end Illumina RNA-seq data. ChimPipe relies on both discordant paired-end reads and split-reads for optimal detection [35].

- Check Mapping Strategy: ChimPipe uses the GEMtools RNA-seq pipeline and GEM RNA mapper for an exhaustive mapping search. Confirm that these components are correctly installed and configured [35].

- Inspect Independent Evidence: ChimPipe finds split-reads and discordant paired-end reads independently. Check the intermediate output files for both types of evidence to see if one is lacking [35].

Issue 2: FusionCatcher Fails to Detect Expected Known Fusions

Problem: FusionCatcher analysis completes but does not report a known fusion gene that is clinically validated in the sample.

Solution:

- Confirm Database Content: Ensure the reference database you are using includes the gene symbols for your expected fusion. The database should be built for the correct species (e.g.,

homo_sapiens) [31]. - Avoid Non-Default Parameters: FusionCatcher's performance decreases dramatically with non-default parameters. Re-run the analysis using the default settings, which are optimized for the best balance of sensitivity and specificity [31].

- Provide a Matched Normal: If available, use the

-Ioption to provide a directory containing a matched normal sample from the same patient. This creates a personalized background filter to improve specificity for somatic fusions [31].

Issue 3: DADA2 Produces an Unexpectedly High Number of ASVs

Problem: The DADA2 output contains a much larger number of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) than anticipated based on biological knowledge.

Solution:

- Review Truncation Parameters: Re-inspect the quality profiles of your forward and reverse reads using

plotQualityProfile()to ensure yourtruncLenparameter is set appropriately. Poor truncation can leave low-quality bases that interfere with denoising [36]. - Tighten Filtering Criteria: The standard filtering parameter

maxEE(maximum expected errors) can be tightened. This is a more effective filter than averaging quality scores and can reduce the number of spurious sequences entering the DADA2 algorithm [36]. - Investigate Biological Reality: Consider if the observed diversity could reflect genuine biological variation. You can use the

isBimeraDenovo()function in DADA2 to check if the excess ASVs are technical chimeras.

Tool Comparison and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Key Features and Applications of Chimera Detection Tools

| Tool | Primary Purpose | Methodology | Key Feature | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChiTaH [32] | Identify known human chimeras | Reference-based mapping | Fastest and most accurate for known chimeras | Clinical detection of known driver fusions (e.g., BCR-ABL1) |

| ChimPipe [35] | Detect fusion genes & transcriptional chimeras | Discordant PE reads + split-reads | Best trade-off between sensitivity and precision | Research discovery of novel chimeras in any eukaryotic species |

| FusionCatcher [31] | Detect somatic fusion genes in cancer | Multi-aligner (BOWTIE, BLAT, STAR) | Integrated biological knowledge for filtering | Oncology research; gold standard for validation rate |

| DADA2 [36] | Identify amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) | Divisive partitioning & error model | High-resolution output of exact sequences | Microbiome and metabarcoding studies |

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance on Real and Simulated Datasets (Based on Published Studies)

| Tool | Sensitivity | Precision | Junction Coordinate Accuracy | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChiTaH | High [32] | High [32] | High [32] | Top performer for identifying known human chimeras |

| ChimPipe | High [35] | High [35] | Best [35] | Top program for identifying exact junction coordinates |

| FusionCatcher | High for its niche [30] | High (Excellent RT-PCR validation rate) [31] | Varies | Excels at detecting difficult fusions (e.g., IGH, DUX4) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Detecting Known Chimeras with ChiTaH

Methodology:

- Input: High-throughput sequencing data (DNA-Seq or RNA-Seq) [32].

- Mapping: Sequencing reads are mapped to a custom reference database of 43,466 non-redundant known human chimeras [32].

- Identification: Chimeric reads are identified and accurately quantified based on this mapping [32].

- Output: A list of known chimeras present in the sample, with supporting read counts.

Workflow Visualization:

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Chimera Discovery with ChimPipe

Methodology:

- Input: Paired-end Illumina RNA-seq data [35].

- Independent Read Extraction:

- Split-reads: Identified directly from reads that do not map contiguously to the genome.

- Discordant PE reads: Identified independently from read pairs mapping inconsistently with annotated gene structure [35].

- Junction Detection: Chimeric junctions are defined primarily using the more sensitive split-reads [35].

- Filtering: Discordant PE reads are used as supporting evidence to reduce the false positive rate (though not strictly compulsory) [35].

- Output: A list of high-confidence chimeras with base-pair resolution of junction points.

Workflow Visualization:

Protocol 3: Optimized Fusion Detection in Cancer with FusionCatcher

Methodology:

- Input: Raw FASTQ files from tumor RNA-seq (do not pre-trim) [31].

- Multi-Aligner Execution: The tool sequentially uses three aligners:

- BOWTIE: For fusions at known exon borders.

- BLAT: For fusions within exons/introns, even with incomplete annotation.

- STAR: For splice-aware detection of complex events [31].

- Biological Filtering: Results are filtered against extensive databases of known false positives (e.g., from healthy samples), pseudogenes, and read-throughs [31].

- Output: A final list of high-confidence somatic fusion genes, prioritized for clinical relevance.

Workflow Visualization:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Databases for Chimera Detection Experiments

| Item | Function | Example/Tool Association |

|---|---|---|

| Known Chimera Database | Reference for mapping and identifying known fusion sequences | ChiTaH database (43,466 human chimeras) [32] |

| Genome Annotation (GTF) | Provides gene model coordinates for alignment and junction annotation | GENCODE annotation (used by FusionCatcher/Arriba) [37] |

| Reference Genome Sequence | Primary sequence for read alignment and mapping | GRCh38 primary assembly [37] |

| Blacklist File | Filters out recurrent technical artifacts and common false positives | Blacklist for hg38 (used by Arriba) [37] |

| False Positive Filter Database | Database of fusions found in healthy samples to remove non-somatic events | Internal database used by FusionCatcher [31] |

| Validated Oncogene Database | Highlights fusions with known clinical or driver significance | Used for prioritization in FusionCatcher output [31] |

FAQs: Long-Read Sequencing for Complex Rearrangements

Q1: What are the key advantages of long-read sequencing over short-read for detecting complex chimeras and structural variants?

Long-read sequencing technologies fundamentally overcome critical limitations of short-read sequencing for complex genomic analyses. They generate reads consistently longer than 10 kb, enabling them to span large, repetitive regions and resolve complex structural rearrangements in a single read [38]. Key advantages include the ability to perform direct phasing (determining which variants are inherited from each parent) without needing parental samples, detect epigenetic modifications like methylation simultaneously, and provide a more exhaustive view of the genome, uncovering approximately 5.8% more of the "telomere-to-telomere" genome that short reads cannot access [39]. This comprehensive data often allows for a diagnosis in a single, cost-efficient test, transforming years-long diagnostic journeys into a matter of days [39].

Q2: Our clinical microarray identified copy number variants (CNVs) suggestive of an underlying complex rearrangement. Short-read genome sequencing could not resolve the structure. What is the recommended long-read approach?

This scenario is a primary application for long-read sequencing. As demonstrated in the resolution of rare genetic syndromes, platforms like Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) circular consensus sequencing (HiFi) are highly effective for this task [38]. The process involves:

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare a whole-genome library and sequence it on a long-read platform to generate high-fidelity (HiFi) reads.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map the long reads to a reference genome (preferably a complete "telomere-to-telomere" assembly) and use specialized structural variant (SV) callers.

- Validation: The long reads often provide inherent validation through multiple spanning reads. This approach has successfully resolved novel recombinant chromosomes (e.g., Rec8) and complex rearrangements involving multiple interstitial deletions, precisely defining breakpoints and genomic structures that other technologies could only hint at [38].

Q3: We are using long-range PCR with Nanopore sequencing for targeted phasing. Our pipeline detects a proportion of "chimeric reads." How do we distinguish PCR artifacts from real biological rearrangements?

Chimeric reads are a known challenge in long-range PCR and require careful bioinformatic filtering [40]. To minimize and identify them:

- Optimize PCR: Use high-fidelity PCR kits and limit PCR cycles (e.g., 26 cycles) to reduce artifact formation [40].

- Bioinformatic Filtering: Implement a pipeline specifically designed to detect and flag chimeric reads. Under optimized conditions, the median proportion of chimeric reads can be maintained at a low level (e.g., 2.80%) [40].

- Validation: Correlate findings with orthogonal data. A real biological chimera, such as a gene fusion in cancer, may be supported by independent evidence from RNA sequencing or may affect a gene with known clinical relevance, whereas artifacts typically are not [41].

Q4: In single-cell long-read genome sequencing, we encounter significant technical noise. How can we confidently identify real somatic transposon activity?

Single-cell long-read sequencing is susceptible to amplification biases and errors. To validate somatic variants like transposon activity [42]:

- Benchmarking: Use a validated benchmark, such as the Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) sample, to establish baseline error rates for your specific wet-lab and computational workflow.

- Multi-modal Confirmation: Compare single-cell calls with high-coverage bulk long-read and short-read sequencing data from the same sample. True somatic events may be present at low variant allele frequencies (VAF) in bulk data.

- Error Profile Analysis: Distinguish true variants from amplification artifacts by analyzing substitution patterns. True somatic variants show balanced patterns (e.g., C>T and T>C occur with roughly equal frequency), while a predominant C>T pattern often indicates a common amplification error [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Long-Read Sequencing Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to resolve complex SVs | Short read lengths; repetitive regions | Implement PacBio HiFi or ultra-long ONT reads; use a T2T reference genome [38] [39] |

| High chimeric read rate in amplicons | PCR artifacts; excessive cycles | Optimize LR-PCR with a high-fidelity kit (e.g., UltraRun LongRange); reduce PCR cycles to ~26 [40] |

| Low diagnostic yield in rare disease | Incomplete reference; missed phasing | Employ long-read sequencing for comprehensive variant detection, phasing, and methylation in one test [39] |

| Poor MAG recovery from complex soils | High microbial diversity; low yield | Use deep long-read sequencing (~100 Gbp/sample) & advanced binning (e.g., mmlong2 workflow) [43] |

| False positives in single-cell SV calling | Whole-genome amplification bias | Benchmark with GIAB; filter using coverage/identity thresholds; validate against bulk data [42] |

Table 2: Optimized Long-Range PCR and Nanopore Sequencing Protocol

This protocol, adapted from Jamshidi et al. 2025, provides a robust workflow for phasing distantly separated variants or analyzing regions with high homology [40].

| Step | Key Parameters | Details & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Design | Target Size: 1-20 kb | Use NCBI Primer-BLAST; design primers in unique sequence regions flanking the target. |

| PCR Optimization | Kit: UltraRun LongRange PCR Kit | Success rate of 90% for amplification up to 22 kb [40]. |

| Cycles: 26 | Minimizes chimeric read formation. | |

| Library Prep | Method: Native Barcoding (SQK-NBD114.24) | Enables multiplexing of up to 8 amplicons on a single Flongle flow cell. |

| Sequencing | Flow Cell: Flongle (R10.4.1) | A cost-effective solution for targeted sequencing. |

| Basecalling: Super Accuracy (SUP) | Uses dna_r10.4.1_e8.2_400bps_sup@v4.3.0 for high accuracy. |

|

| Bioinformatic Analysis | Read Filtering: MAPQ ≥ 20; Read Identity ≥ 80% | Removes poorly mapped and low-quality reads. |

| Variant Caller: Clair3 v1.0.4 | Optimized for accurate variant calling from long reads. | |

| Phasing Tool: WhatsHap v2.3 | Determines the phase of variants on haplotypes. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Resolving Complex Genomic Rearrangements with Long-Read Sequencing

Methodology: This protocol describes using PacBio Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) to resolve complex chromosomal rearrangements in patients with rare genetic syndromes, where microarrays and short-read sequencing were inconclusive [38].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- DNA Extraction: Use high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA extraction kits to ensure DNA integrity and length.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare a SMRTbell library for the patient sample. Sequence the library on a PacBio Sequel II system to generate HiFi reads. Target a minimum mean depth of coverage of 30x for confident SV calling.

- Data Processing and Alignment: Process raw subreads to generate HiFi reads (QV > 30) using the SMRT Link software. Align the HiFi reads to the human reference genome (GRCh38) using a long-read aware aligner like

pbmm2. - Variant and SV Calling: Call structural variants using a long-read specific SV caller. Simultaneously, call small variants (SNVs, indels).