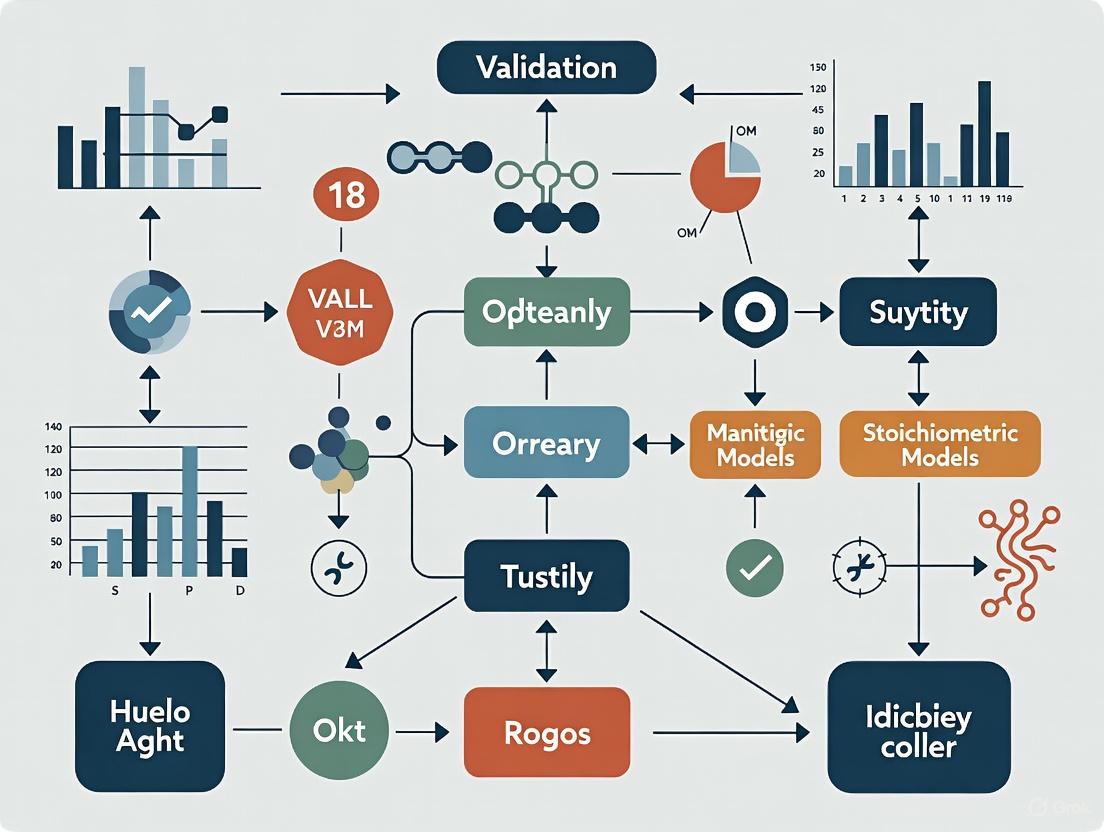

Validation of Stoichiometric Models for Microbial Communities: A Framework for Biomedical Research

Stoichiometric models, particularly Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs), provide a powerful computational framework for simulating the metabolic interactions within microbial communities and their hosts.

Validation of Stoichiometric Models for Microbial Communities: A Framework for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Stoichiometric models, particularly Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs), provide a powerful computational framework for simulating the metabolic interactions within microbial communities and their hosts. For researchers and drug development professionals, the predictive power of these models hinges on robust validation strategies. This article details a comprehensive roadmap, from the foundational principles of constraint-based modeling and the COBRA framework to advanced methodological applications for simulating community behaviors. It further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects for model optimization and synthesizes a multi-metric validation framework that integrates thermodynamic, experimental, and comparative analyses. By establishing rigorous validation standards, this guide aims to enhance the reliability of model predictions, thereby accelerating their translation into biomedical discoveries and therapeutic interventions.

The Foundation of Microbial Community Modeling: From GEMs to Cross-Feeding

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are comprehensive knowledge bases that mathematically represent the complete set of metabolic reactions occurring within a cell, tissue, or organism [1]. These models integrate biological data with mathematical rigor to describe the molecular relationships between genes, proteins, and metabolites, enabling systematic study of metabolic capabilities [2] [3].

The Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) framework is the predominant methodology for simulating and analyzing GEMs [4] [3]. This approach calculates intracellular flux distributions that satisfy three fundamental constraints: steady-state mass-balance (equating production and consumption rates for metabolites), reaction reversibility (ensuring irreversible reactions proceed in thermodynamically feasible directions), and enzyme capacity (limiting flux rates based on measured capabilities) [3]. The solution space defined by these constraints contains all feasible metabolic phenotypes, which can be explored using various computational techniques [3] [5].

Comparative Analysis of GEM Reconstruction Tools

Different automated reconstruction tools produce varying model structures due to their distinct algorithms, biochemical databases, and reconstruction philosophies, significantly impacting downstream predictions [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Automated GEM Reconstruction Tools

| Tool | Reconstruction Approach | Primary Database | Key Features | Typical Output Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Top-down | A curated, universal template | Fast model generation; Ready-to-use networks | Highest number of genes; Moderate reactions/metabolites [6] |

| gapseq | Bottom-up | Multiple comprehensive sources | Extensive biochemical information | Most reactions and metabolites; More dead-end metabolites [6] |

| KBase | Bottom-up | ModelSEED | User-friendly platform; Integrated environment | Moderate genes/reactions; Similar metabolites to gapseq [6] |

A comparative study using metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from marine bacterial communities revealed substantial structural differences between models generated by different tools from the same genomic data [6]. The Jaccard similarity for reaction sets between gapseq and KBase models was only 0.23-0.24, while metabolite similarity was 0.37, indicating limited overlap [6]. This suggests that the choice of reconstruction tool introduces significant variation and uncertainty in model predictions.

Table 2: Structural Comparison of Community GEMs from Different Reconstruction Approaches

| Metric | CarveMe | gapseq | KBase | Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Genes | Highest | Lowest | Moderate | High (similar to CarveMe) [6] |

| Number of Reactions | Moderate | Highest | Moderate | Highest (encompasses unique reactions) [6] |

| Number of Metabolites | Moderate | Highest | Moderate | Highest [6] |

| Dead-End Metabolites | Moderate | Highest | Moderate | Reduced [6] |

| Jaccard Similarity with Consensus (Genes) | 0.75-0.77 | Lower | Lower | 1.0 [6] |

Validation Frameworks for Stoichiometric Models

ComMet: A Method for Comparing Metabolic States

The ComMet (Comparison of Metabolic states) approach enables in-depth investigation of different metabolic conditions without assuming objective functions [1]. This method combines flux space sampling with network analysis to identify functional differences between metabolic states and extract distinguishing biochemical features [1].

ComMet Workflow:

- Flux Space Characterization: Uses analytical approximation of flux probability distributions instead of conventional sampling, reducing computational time while maintaining accuracy [1].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Applies Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to decompose flux spaces into biochemically interpretable reaction sets (modules) [1].

- Comparative Analysis: Identifies metabolic differences between conditions through rigorous optimization strategies [1].

- Visualization: Presents results in three network modes to highlight functional distinctions [1].

ComMet Analysis Workflow

Consensus Modeling Approach

Consensus reconstruction addresses tool-specific biases by merging draft models from multiple tools (CarveMe, gapseq, KBase) into a unified model [6]. This approach retains more unique reactions and metabolites while reducing dead-end metabolites, creating more functionally capable models [6]. Consensus models demonstrate stronger genomic evidence support by incorporating a greater number of genes from the combined sources [6].

Extreme Pathway Analysis for Network Validation

Extreme Pathway (ExPa) analysis examines the edges of the conical solution space containing all feasible steady-state flux distributions [4]. The ratio of extreme pathways to reactions (P/R) reveals fundamental network properties: metabolic networks typically show high P/R ratios (e.g., 33.44 for amino acid, carbohydrate, lipid metabolism), indicating numerous alternative pathways and redundancy, while transcriptional and translational networks exhibit lower P/R ratios (0.12-0.75), reflecting more linear structures [4]. ExPa analysis can also identify network incompleteness by detecting reactions that don't participate in any pathway [4].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Community Model Reconstruction and Gap-Filling

Objective: Reconstruct and validate metabolic models for microbial communities using metagenomics data [6].

Protocol:

- Input Data Preparation: Collect high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) or isolate genomes [6].

- Draft Model Generation: Create individual GEMs using multiple automated tools (CarveMe, gapseq, KBase) [6].

- Consensus Model Building: Merge draft models from different tools for each organism using a consensus pipeline [6].

- Community Integration: Combine individual models into a community model using compartmentalization, with each species in a distinct compartment sharing a common extracellular environment [6].

- Gap-Filling: Apply the COMMIT algorithm with an iterative approach based on MAG abundance, starting with minimal medium and dynamically updating with permeable metabolites identified during the process [6].

- Validation: Test the influence of iterative order on gap-filling solutions and verify functional capabilities against experimental data [6].

Community Model Reconstruction Workflow

ComMet Protocol for Metabolic State Comparison

Objective: Identify functional metabolic differences between conditions (e.g., healthy vs. diseased, different nutrient availability) [1].

Protocol:

- Model Preparation: Obtain context-specific GEMs for each condition (e.g., iAdipocytes1809 for adipocyte metabolism) [1].

- Condition Specification: Define condition-specific constraints (e.g., unlimited vs. blocked uptake of branched-chain amino acids) [1].

- Flux Space Analysis: Apply the analytical approximation algorithm to characterize flux spaces for each condition [1].

- Module Extraction: Perform PCA-based decomposition to identify biochemical modules accounting for flux variation [1].

- Comparative Optimization: Implement rigorous optimization strategies to extract distinguishing features between conditions [1].

- Biological Validation: Corroborate identified metabolic processes (e.g., TCA cycle, fatty acid metabolism) with literature evidence [1].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GEM Validation

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Database | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction Platforms | CarveMe, gapseq, KBase | Generate draft GEMs from genomic data [6] |

| Biochemical Databases | KEGG, MetaCyc, ModelSEED | Provide reaction, metabolite, and pathway information for reconstruction [3] |

| Analysis Frameworks | ComMet [1], COMMIT [6] | Compare metabolic states and perform community gap-filling |

| Pathway Analysis Tools | Extreme Pathway Analysis | Characterize solution space and identify network gaps [4] |

| Model Standards | Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) | Enable model exchange and interoperability between tools |

| Community Modeling | COBRA Toolbox [3] | Simulate and analyze multi-species community interactions |

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) is a mechanistic, computational approach for modeling metabolic networks. At its core, COBRA uses genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs)—mathematical representations of an organism's metabolism—to simulate metabolic fluxes and predict phenotypic behavior [7]. The COBRA framework leverages knowledge of the stoichiometry of metabolic reactions, along with constraints on reaction fluxes, to define the set of possible metabolic behaviors a cell can display. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is the most widely used technique within the COBRA toolbox. FBA computes flow of metabolites through a metabolic network by optimizing a cellular objective, typically the maximization of biomass production, under the assumption of steady-state metabolite concentrations and within the bounds of known physiological constraints [8] [9]. These methods have become indispensable in systems biology, with applications ranging from metabolic engineering of individual strains to the analysis of complex microbial communities [7] [10].

Theoretical Foundations and Key Methodologies

The Core Principle of Flux Balance Analysis

FBA operates on the fundamental premise that metabolic networks reach a quasi-steady state where the production and consumption of each intracellular metabolite are balanced. This is represented mathematically by the equation:

N · v = 0

where N is the stoichiometric matrix (with metabolites as rows and reactions as columns), and v is the vector of metabolic reaction fluxes [9]. The solution space of possible flux distributions is further constrained by imposing lower and upper bounds (vi ≤ Ci) on individual reaction fluxes, representing known physiological limitations, thermodynamic irreversibility, or substrate uptake rates [9].

The FBA solution is found by optimizing an objective function, most commonly biomass production, which is represented as a pseudo-reaction that drains biomass precursors in their known proportions. The standard FBA formulation is thus:

max vBM subject to: N · v = 0, virrev ≥ 0, vi ≤ Ci

This linear programming problem efficiently identifies an optimal flux distribution that maximizes the objective function, predicting growth rates and metabolic byproduct secretion that often closely match experimental observations [9].

Dynamic and Community Extensions of FBA

Basic FBA assumes a steady-state and is therefore best suited for modeling continuous cultures. For dynamic systems like batch or fed-batch cultures, Dynamic FBA (dFBA) was developed. dFBA combines FBA with ordinary differential equations that describe time-dependent changes in extracellular substrate, product, and biomass concentrations [11] [10]. In practice, dFBA sequentially performs FBA at discrete time points, updating the extracellular environment between each optimization, allowing it to capture the metabolic shifts that occur as substrates are depleted [11].

To model microbial communities, FBA has been extended into several frameworks. These approaches generally fall into three categories:

- Group-level objective optimization, where a community-level objective function is optimized [12].

- Independent optimization, where each species' growth is optimized independently [12].

- Abundance-adjusted optimization, where measured species abundances are used to constrain or weight individual growth rates [12].

Tools like COMETS further incorporate spatial dimensions and metabolite diffusion, enabling more realistic simulations of microbial ecosystems [12].

Alternative Approaches: Flux Sampling and Elementary Conversion Modes

A significant limitation of standard FBA is that it requires the assumption of a cellular objective, which can introduce observer bias, especially in non-optimal or rapidly changing environments [8]. Flux sampling addresses this by generating a probability distribution of feasible steady-state flux solutions instead of a single optimal point. This is achieved using algorithms like Coordinate Hit-and-Run with Rounding (CHRR), which randomly sample the solution space defined by the constraints, providing a more comprehensive view of metabolic capabilities without presuming a single objective [8].

Another powerful concept is that of Elementary Conversion Modes (ECMs), which are the minimal sets of net conversions between external metabolites that a network can perform [13] [9]. Unlike Elementary Flux Modes (EFMs) that describe internal pathway routes, ECMs focus solely on input-output relationships, drastically reducing computational complexity and allowing for the thermodynamic characterization of all possible catabolic and anabolic routes in a network [13] [9].

Comparative Analysis of COBRA Tools and Performance

Qualitative Comparison of Community Modeling Tools

The expansion of COBRA methods has led to the development of numerous software tools. A qualitative assessment based on FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) reveals significant variation in software quality and documentation [10].

Table 1: Qualitative Features of Prominent COBRA Tools for Microbial Communities.

| Tool Name | Modeling Approach | Key Features | Community Objective | Spatiotemporal Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MICOM [10] [12] | Steady-state | Uses abundance data; cooperative trade-off | Maximizes community & individual growth | No |

| COMETS [10] [12] | Dynamic, Spatiotemporal | Incorporates metabolite diffusion & 2D/3D space | Independent species optimization | Yes (2D/3D) |

| Microbiome Modeling Toolbox (MMT) [12] | Steady-state | Pairwise interaction screening; host-microbe modeling | Simultaneous growth rate maximization | No |

| SteadyCom [12] | Steady-state | Assumes community steady-state | Maximizes community growth rate | No |

| OptCom [12] | Steady-state | Bilevel optimization | Embedded optimization (community & individual) | No |

Quantitative Performance Evaluation

A systematic evaluation of COBRA tools against experimental data for two-species communities provides critical insight into their predictive accuracy [10] [12]. Performance was tested in various scenarios, including syngas fermentation (Clostridium autoethanogenum and C. kluyveri), sugar mixture fermentation (engineered E. coli and S. cerevisiae), and spatial patterning on a Petri dish (E. coli and Salmonella enterica) [10].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of COBRA Tools for Predicting Community Phenotypes.

| Tool / Category | Predictive Accuracy for Growth Rates | Accuracy of Interaction Strength Prediction | Computational Tractability | Key Limiting Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-Curated GEMs (e.g., from AGORA) | Low correlation with experimental data [12] | Low correlation with experimental data [12] | Generally fast | Model quality and curation [12] |

| Manually Curated GEMs | Higher accuracy | More reliable | Fast | Limited availability of curated models [12] |

| Static (Steady-State) Tools | Varies; sensitive to medium definition [10] [12] | Varies | Fast | Cannot capture dynamics [10] |

| Dynamic Tools (e.g., COMETS) | Can be high; depends on kinetic parameters [10] | Can capture facilitation & competition over time [12] | Computationally intensive | Requires accurate kinetic parameters [10] |

| Spatiotemporal Tools | Can predict spatial patterns [10] | Can predict spatially-dependent interactions [10] | Most computationally intensive | Requires diffusion parameters [10] |

These evaluations show that even the best tools have limitations. Predictions using semi-curated, automated reconstructions from databases like AGORA often show poor correlation with measured growth rates and interaction strengths, highlighting that model quality is a critical determinant of predictive accuracy [12]. Furthermore, the mathematical formulation of the community objective function significantly impacts the predicted ecological interactions, such as cross-feeding and competition [12].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Dynamic FBA (dFBA)

The application of dFBA to evaluate strain performance, as demonstrated in a case study of shikimic acid production in E. coli [11], involves a multi-step workflow that integrates experimental data with simulation.

Diagram 1: dFBA workflow for strain evaluation.

Step 1: Data Extraction and Approximation.

- Procedure: Manually extract time-course data for key extracellular variables (e.g., glucose and biomass concentrations) from experimental literature using tools like WebPlotDigitizer. Fit these data points to polynomial equations (e.g., 5th order) using least-squares regression to create continuous functions describing the concentrations over time [11].

- Output: Approximate equations:

Glc(t)for glucose andX(t)for biomass [11].

Step 2: Calculate Specific Rates for Constraints.

- Procedure: Differentiate the concentration equations with respect to time to get the absolute consumption and growth rates. Then, divide these rates by the biomass concentration

X(t)to obtain the specific glucose uptake rate and the specific growth rate [11]. - Output: Equations for

v_uptake_Glc_approx(t)andμ_approx(t), which serve as time-varying constraints in the subsequent FBA [11].

Step 3: Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis.

- Procedure: At each discrete time point in the simulation, impose the calculated specific uptake and growth rates as constraints on the genome-scale model. Perform a bi-level FBA optimization: the inner problem typically maximizes growth, while the outer problem maximizes the production of the target compound (e.g., shikimic acid). The obtained fluxes are then used in numerical integration to update metabolite concentrations for the next time step [11].

- Output: Time-series data of metabolic fluxes and metabolite concentrations, including the theoretical maximum production of the target compound [11].

Step 4: Performance Evaluation.

- Procedure: Compare the simulated maximum production concentration of the target compound with the actual experimental value obtained from the strain. The ratio (e.g., experimental concentration / simulated maximum concentration) quantifies the performance of the engineered strain [11].

- Output: A quantitative metric for strain performance. In the case study, the experimental strain achieved 84% of the simulated maximum shikimic acid production [11].

Protocol for Flux Sampling with CHRR

Flux sampling is used to explore the entire space of feasible metabolic states without assuming a single objective function. The Coordinate Hit-and-Run with Rounding (CHRR) algorithm has been identified as the most efficient for this task [8].

Diagram 2: Flux sampling workflow with CHRR.

Step 1: Problem Definition.

- Procedure: Load the genome-scale metabolic model and apply the desired constraints, including stoichiometric constraints (

N · v = 0), irreversibility constraints (virrev ≥ 0), and any additional flux constraints based on the environmental or genetic context [8].

Step 2: Preprocessing and Sampling.

- Procedure: The CHRR algorithm first preprocesses the convex solution space defined by the constraints using a rounding procedure to improve sampling efficiency. It then employs a "hit-and-run" Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method to generate a sequence (chain) of feasible flux solutions [8].

- Parameters: The user must specify the total number of samples to generate (e.g., 5,000,000) and a "thinning" constant. Thinning involves storing only every k-th sample (e.g., every 1000th) to reduce autocorrelation between consecutive samples in the chain [8].

Step 3: Convergence Diagnostics.

- Procedure: Run multiple independent chains and assess convergence using diagnostics like the Potential Scale Reduction Factor (PSRF). This ensures the chain has adequately explored the entire solution space and that the samples provide an accurate representation [8].

- Output: A converged set of flux samples that represent the probability distribution of metabolic fluxes under the given constraints.

Step 4: Analysis.

- Procedure: Analyze the sampled fluxes to determine the range of feasible fluxes for each reaction (similar to FVA) and their probability distributions. This can reveal alternative metabolic pathways and the robustness of network functions to perturbations [8].

Successful implementation of COBRA methods relies on a suite of computational and data resources.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for COBRA Modeling.

| Resource Type | Name / Example | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Model Repository | AGORA [12] | A library of semi-curated, genome-scale metabolic models for human gut bacteria. |

| Software Toolbox | COBRA Toolbox [11] [8] | A MATLAB-based suite for performing FBA, dFBA, flux sampling, and other constraint-based analyses. |

| Sampling Algorithm | CHRR [8] | An efficient algorithm for sampling the feasible flux space of genome-scale models. |

| Pathway Analysis Tool | ecmtool [13] [9] | Software for calculating Elementary Conversion Modes (ECMs) to enumerate metabolic capabilities. |

| Thermodynamic Database | eQuilibrator [13] | A tool for estimating Gibbs free energy of formation and reaction, used for thermodynamic analysis of pathways. |

| Data Extraction Tool | WebPlotDigitizer [11] | A tool to manually extract numerical data from published graphs and figures for use as model constraints. |

| Quality Control Tool | MEMOTE [12] | A tool for the systematic and standardized quality assessment of genome-scale metabolic models. |

COBRA and FBA provide a powerful, mechanistic framework for predicting microbial metabolism, from single strains to complex communities. The core strength of these methods lies in their ability to integrate genomic and experimental data to generate testable hypotheses. However, the predictive power of any COBRA approach is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the underlying metabolic model, with manually curated models significantly outperforming automated reconstructions. The choice of tool—be it for steady-state analysis (MICOM), dynamic modeling (COMETS), or objective-free exploration (Flux Sampling)—must be guided by the biological question and the availability of relevant constraint data. As the field moves forward, improving model curation, refining community objective functions, and better integration of multi-omic data will be crucial for enhancing the reliability and scope of constraint-based modeling in microbial ecology and metabolic engineering.

Extending Single-Species Models to Microbial Communities and Host-Microbe Interactions

The transition from modeling individual microbial species to capturing the complexities of entire communities and their interactions with a host represents a significant frontier in systems biology. This progression is vital for applications ranging from drug development to understanding ecosystem dynamics. The validation of stoichiometric models, particularly genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), is a critical step in ensuring these in-silico tools provide reliable insights into the functional potential of microbial communities and the metabolic basis of host-microbe interactions. This guide objectively compares the performance of predominant modeling approaches, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Comparative Analysis of Community Model Reconstruction Approaches

Different automated reconstruction tools, relying on distinct biochemical databases, produce models with varying structures and functional capabilities. A comparative analysis of three major tools—CarveMe, gapseq, and KBase—alongside a consensus approach reveals significant differences in model properties [6].

The following tables summarize the quantitative structural differences and similarities of community models generated from the same metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) for two marine bacterial communities.

Table 1: Structural characteristics of GEMs from coral-associated and seawater bacterial communities, reconstructed via different tools. Data adapted from [6].

| Reconstruction Approach | Number of Genes | Number of Reactions | Number of Metabolites | Number of Dead-End Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Highest | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| gapseq | Lowest | Highest | Highest | Highest |

| KBase | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| Consensus | High (similar to CarveMe) | Highest | Highest | Lowest |

Table 2: Jaccard similarity indices for model components between different reconstruction approaches (average of coral and seawater community data). A value of 1 indicates identical sets, while 0 indicates no overlap. Data adapted from [6].

| Comparison | Reaction Similarity | Metabolite Similarity | Gene Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|

| gapseq vs. KBase | 0.24 | 0.37 | Lower |

| CarveMe vs. gapseq/KBase | Lower | Lower | - |

| CarveMe vs. KBase | - | - | 0.44 |

| CarveMe vs. Consensus | - | - | 0.76 |

The consensus approach, which integrates models from different tools, demonstrates distinct advantages by encompassing a larger number of reactions and metabolites while simultaneously reducing network gaps (dead-end metabolites) [6]. Furthermore, the set of predicted exchanged metabolites was more influenced by the reconstruction tool itself than by the specific bacterial community being modeled, highlighting a potential bias in interaction predictions that can be mitigated by the consensus method [6].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation and Application

Protocol 1: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) for Metabolic Interactions

Purpose: To simulate metabolic interactions between microbes or between a microbe and its host in a shared environment by calculating the distribution of metabolic fluxes at a steady state [14].

Detailed Methodology:

- Network Reconstruction: Represent the metabolic network of each bacterium or host cell as a stoichiometric matrix S, where rows correspond to metabolites and columns to reactions. This matrix defines the substrate and product relationships for all biochemical conversions [14].

- Define Constraints: Impose lower and upper bounds ((v{i, min}) and (v{i, max})) on the flux (v_i) of each reaction to reflect environmental conditions (e.g., nutrient availability) or enzyme capacities [14].

- Formulate the Objective Function (OF): Define a biological objective, formulated as (Z = c^T * v), to be optimized. Common objectives include maximizing biomass production (simulating growth) or maximizing the production of a specific metabolite of interest [14].

- Solve the Linear System: Under the steady-state assumption ((S * v = 0)), use linear programming to find a flux distribution (v) that optimizes the objective function (Z) within the defined constraints [14].

Application Example: To study cross-feeding, the metabolic models of Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii can be placed in a shared metabolic compartment. Simulating this system with an OF such as "minimize total glucose consumption" can demonstrate how B. adolescentis secretes acetate, which is then utilized by F. prausnitzii for growth and butyrate production, thereby predicting the emergent interaction [14].

Protocol 2: Building and Gap-Filling a Consensus Community Model

Purpose: To generate a more comprehensive and functionally complete community metabolic model by integrating reconstructions from multiple automated tools [6].

Detailed Methodology:

- Draft Model Generation: Reconstruct draft GEMs for each genome in the community using at least two different automated tools (e.g., CarveMe, gapseq, KBase) that employ different biochemical databases and reconstruction logics (top-down vs. bottom-up) [6].

- Draft Model Merging: For each individual genome, merge the draft models from the different tools into a single draft consensus model [6].

- Community Model Integration: Combine all individual consensus models into a community model, typically using a compartmentalization approach where each species is assigned a distinct compartment, all sharing a common extracellular space [6].

- Gap-Filling with COMMIT: Use the COMMIT tool to perform community-scale gap-filling. This process uses an iterative approach:

- Start with a minimal medium.

- Incorporate models into the community one by one (e.g., based on MAG abundance).

- After gap-filling each model, its predicted secreted metabolites are added to the shared medium, making them available for subsequent models.

- This step adds necessary reactions to ensure model functionality in the community context [6].

Key Finding: The number of reactions added during the gap-filling step shows only a negligible correlation (r = 0–0.3) with the abundance order of MAGs, suggesting the iterative order has minimal influence on the final gap-filling solution [6].

Visualization of Workflows and Logical Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical workflows for the consensus modeling approach and the fundamental principles of constraint-based modeling.

Diagram 1: Consensus community model reconstruction workflow. MAGs are processed by multiple tools, merged, and integrated before final gap-filling.

Diagram 2: Core workflow for Flux Balance Analysis (FBA).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Computational Solutions

This section details essential resources for constructing and validating community and host-microbe metabolic models.

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational solutions for microbial community modeling.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Software Tool | Automated GEM reconstruction using a top-down, template-based approach. | Produces models quickly; often contributes the majority of genes in consensus models [6]. |

| gapseq | Software Tool | Automated GEM reconstruction using a bottom-up, biochemical database-driven approach. | Tends to generate models with the highest number of reactions and metabolites [6]. |

| KBase | Software Platform | Integrated platform for systems biology, including GEM reconstruction and analysis. | Shares ModelSEED database with gapseq, leading to higher model similarity [6]. |

| COMMIT | Software Tool | Community-scale model gap-filling. | Uses an iterative approach to ensure community models are functional in a shared environment [6]. |

| ModelSEED | Biochemical Database | Curated database of reactions, compounds, and pathways. | Underpins reconstructions in tools like gapseq and KBase [6]. |

| AGORA | Model Resource | A curated library of GEMs for common human gut microbes. | Pre-curated models that can be used for host-microbiome interaction studies [14]. |

| Recon3D | Model Resource | A comprehensive, consensus GEM of human metabolism. | Used as a host model for integrating with microbial models to study host-microbe interactions [14]. |

| KRAS G12C inhibitor 53 | KRAS G12C inhibitor 53, MF:C21H14ClF2N5O2, MW:441.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Fludrocortisone acetate-d5 | Fludrocortisone acetate-d5, MF:C23H31FO6, MW:427.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Within microbial communities, species do not exist in isolation but are engaged in a complex web of interactions that fundamentally shape the structure, function, and stability of the ecosystem. Understanding these interactions—particularly syntrophy, competition, and cross-feeding—is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to predict community behavior, engineer consortia for bioproduction, or modulate the human microbiome for therapeutic purposes. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key interactions, with a specific focus on validating stoichiometric models, which use the metabolic network reconstructions of microorganisms to predict community dynamics through mass-balance constraints [15] [16]. The accuracy of these models hinges on their ability to correctly represent the underlying ecological interactions, making empirical validation against experimental data a critical step in the research workflow.

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Interactions

The table below provides a definitive comparison of the three key microbial interactions, highlighting their distinct ecological roles, mechanisms, and outcomes relevant to community modeling.

Table 1: Defining Characteristics of Key Microbial Interactions

| Interaction Type | Ecological Role | Underlying Mechanism | Impact on Community | Representation in Stoichiometric Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syntrophy | Obligatory mutualism that enables both partners to survive in an environment where neither could live alone [17]. | Typically involves the transfer and consumption of inhibitory metabolites (e.g., hydrogen), which alleviates feedback inhibition for the producer [17]. | Creates stable, interdependent partnerships that are critical for breaking down complex substrates [15]. | Modeled as metabolite exchange reactions that are essential for the growth of both partners. |

| Competition | Antagonistic interaction where species vie for the same limited resources. | Direct exploitation of a shared, limiting resource (e.g., carbon, nitrogen, oxygen) [15]. | Drives competitive exclusion or niche differentiation; a key determinant of community composition [15]. | Represented by shared uptake reactions for the same extracellular metabolites; growth rates are tied to resource availability. |

| Cross-Feeding | A mutualistic or commensal interaction where metabolites are exchanged [18] [15]. | Involves the secretion of metabolites (byproducts, amino acids, vitamins) by one organism that are utilized by another [18] [19]. | Enhances community complexity, stability, and collective metabolic output [18] [20]. | Modeled as the secretion of a metabolite by one network and its uptake as a nutrient by another partner's network. |

Stability and Evolutionary Dynamics

A critical consideration for modeling and engineering communities is the evolutionary robustness of these interactions against "cheater" mutants that benefit from the interaction without contributing. Cross-feeding based on the exchange of self-inhibiting metabolic wastes (a form of syntrophy) has been shown to be highly robust against such cheaters over evolutionary time. In contrast, interactions based on cross-facilitation, where organisms share reusable public goods like extracellular enzymes, are far more vulnerable to collapse from cheating mutants [17]. This distinction is crucial for designing stable synthetic consortia.

Experimental Validation of Stoichiometric Models

Stoichiometric models, such as those built from genome-scale metabolic reconstructions, predict interactions by analyzing the metabolic network of each organism to identify potential resource competition and metabolite exchange [15] [16]. The following workflow and experimental data are central to validating these predictions.

Figure 1: Workflow for validating stoichiometric models of microbial communities. The cycle of prediction, experimental testing, and model refinement is key to achieving accurate models.

A Case Study in Model Validation: Engineered Yeast Consortia

Recent research provides a robust protocol for testing model predictions of cross-feeding using engineered auxotrophic strains. In a key study, six auxotrophs of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica were constructed, each lacking a gene essential for synthesizing a specific amino acid or nucleotide (e.g., ∆lys5, ∆trp2, ∆ura3) [20].

Table 2: Experimental Growth Data of Selected Y. lipolytica Auxotrophic Pairs [20]

| Auxotrophic Pair | Exchanged Metabolites | Max OD600 in Co-culture | Lag Phase | Final Population Ratio (Strain A:Strain B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆ura3 / ∆trp4 | Uracil / Tryptophan | ~0.55 [20] | 40 hours [20] | 1 : 1.2 - 1.8 [20] |

| ∆trp4 / ∆met5 | Tryptophan / Methionine | ~0.55 [20] | 20 hours [20] | 1 : 1.0 - 1.9 [20] |

| ∆trp2 / ∆trp4 | Anthranilate / Indole or Tryptophan [20] | Moderate (0.32-0.55) [20] | 12 hours [20] | ~1 : 1.5 (from 1:5 inoculum) [20] |

Experimental Protocol:

- Strain Construction: Create deletion mutants (e.g.,

∆ura3) that are auxotrophic for specific essential metabolites [20]. - Co-culture Inoculation: Combine pairs of auxotrophic strains in a minimal medium that lacks the essential metabolites required by both. A range of initial inoculation ratios (e.g., 10:1 to 1:10) should be tested [20].

- Growth Monitoring: Measure community growth (OD600) and glucose consumption over time to quantify the synergistic effect of the interaction [20].

- Population Tracking: Use flow cytometry or selective plating to track the population dynamics of each strain throughout the growth curve, determining the stable equilibrium ratio [20].

- Metabolite Analysis: Employ HPLC or LC-MS to quantify the exchange of predicted metabolites in the culture supernatant, providing direct evidence for the cross-feeding interaction.

This experimental data serves as a direct benchmark. A stoichiometric model is considered validated if it can correctly predict: a) the viability of the co-culture in minimal medium, b) the specific metabolites being exchanged, and c) the relative growth yields and population dynamics.

Visualization of Interaction Concepts

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts of the microbial interactions discussed in this guide, highlighting their distinct mechanisms.

Figure 2: Conceptual diagrams of key microbial interactions. (Top) Cross-feeding/Syntrophy involves the secretion and consumption of a metabolite. (Middle) Competition arises from shared consumption of a limited resource. (Bottom) Cross-facilitation involves the production of a public good that benefits the whole community.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Interaction Studies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Microbial Interactions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Validation |

|---|---|

| Auxotrophic Mutant Strains | Engineered microorganisms lacking the ability to synthesize specific metabolites; the foundation for constructing and testing obligatory cross-feeding interactions [20]. |

| Defined Minimal Media | Culture media with precisely known chemical composition, essential for controlling nutrient availability and forcing interactions based on specific metabolite exchanges [20]. |

| Flow Cytometer with Cell Sorting | Instrument used to track and quantify individual species in a co-culture over time, enabling the measurement of population dynamics [20]. |

| LC-MS / HPLC Systems | Analytical platforms for identifying and quantifying metabolites in the culture supernatant, providing direct evidence for metabolite exchange in cross-feeding [20]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Computational reconstructions of an organism's metabolism; used to generate predictions about growth requirements, byproduct secretion, and potential interactions [15] [16]. |

| cIAP1 Ligand-Linker Conjugates 2 | cIAP1 Ligand-Linker Conjugates 2, MF:C37H48N4O7, MW:660.8 g/mol |

| Onradivir monohydrate | Onradivir monohydrate, CAS:2375241-19-1, MF:C22H24F2N6O3, MW:458.5 g/mol |

The holobiont concept represents a fundamental paradigm shift in biology, redefining the human host and its associated microbiome not as separate entities but as a single, integrated biological unit. This framework posits that a host organism and the trillions of microorganisms living in and on it form a metaorganism with a combined hologenome that functions as a discrete ecological and evolutionary unit [21]. The conceptual transition from studying isolated components to investigating the integrated holobiont system has profound implications for biomedical research, therapeutic development, and our understanding of complex diseases. This approach acknowledges that evolutionary success is not solely attributable to the host's genome but results from the combined genetic repertoire of the entire system, with natural selection potentially acting on the hologenome due to fitness benefits accrued through the integrated gene pool [21].

Within this framework, health and disease are understood as different stable states of the holobiont ecosystem. A healthy state represents a symbiotic equilibrium where the microbial half significantly contributes to host processes, while a disease state reflects dysbiosis where the holobiont ecosystem is disrupted [21]. This perspective moves beyond traditional models that view the body as a battlefield against microbial invaders and instead recognizes that in the holobiont ecosystem, "there are no enemies, just life forms in different roles" [21]. The reconceptualization necessitates developing sophisticated modeling approaches that can capture the dynamic, multi-kingdom interactions within holobiont systems, particularly through the application of stoichiometric models that quantify metabolic exchanges between hosts and their microbiota.

Holobiont Modeling Approaches: A Comparative Analysis

Multiple computational frameworks have been developed to model the complex interactions within holobiont systems, each with distinct methodologies, applications, and limitations. The table below provides a systematic comparison of the primary modeling approaches used in holobiont research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Holobiont Modeling Approaches

| Modeling Approach | Core Methodology | Data Requirements | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holo-omics Integration [22] [23] | Multi-omic data integration from host and microbiota | (Meta)genomics, (meta)transcriptomics, (meta)proteomics, (meta)metabolomics | Untangling host-microbe interplay in basic ecology, evolution, and applied sciences | Computational complexity in integrating massive, heterogeneous datasets |

| Community Metabolic Modeling [24] | Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) with multi-objective optimization | Genomic annotations, metabolic network reconstructions, constraint parameters | Predicting metabolic interactions, nutrient cross-feeding, and community assembly | Limited by completeness of metabolic annotations and network reconstructions |

| Dynamic Ecological Models [25] | Ordinary/partial differential equations simulating population dynamics | Time-series abundance data, interaction parameters | Predicting community compositional dynamics and stability | Often lacks molecular mechanistic resolution of interactions |

| Microbe-Effector Models [25] | Explicit modeling of molecular effectors (metabolites, toxins) | Metabolomic profiles, interaction assays, uptake/secretion rates | Understanding chemical mediation of microbial growth and community function | Requires extensive parameterization of molecular interactions |

Advancements in Stoichiometric Modeling

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) represent a particularly powerful approach for simulating the metabolic interactions within holobiont systems. These constraint-based models reconstruct the complete metabolic network of an organism from its genomic annotation, enabling quantitative prediction of metabolic fluxes under different conditions [24]. Recent innovations have extended this framework to holobiont systems through multi-objective optimization techniques that simultaneously optimize functions for multiple organisms within the system. For instance, researchers have developed a computational score that integrates simulation results to predict interaction types (competition, neutralism, mutualism) between gut microbes and intestinal epithelial cells [24]. This approach successfully identified potential choline cross-feeding between Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and epithelial cells, explaining their predicted mutualistic relationship [24].

The application of community metabolic modeling to holobiont systems has revealed that even minimal microbiota can favor epithelial cell maintenance, providing a mechanistic understanding of why host cells benefit from microbial partners [24]. These models are particularly valuable for their ability to generate testable hypotheses about metabolic interactions that can be validated experimentally, creating an iterative cycle of model refinement and biological discovery.

Experimental Methodologies for Holobiont Model Validation

Validating holobiont models requires sophisticated experimental approaches that can probe the complex interactions between hosts and their microbiota. The following section details key methodologies and protocols for experimental validation of holobiont model predictions.

Holo-omic Data Acquisition and Integration

The holo-omic approach incorporates multi-omic data from both host and microbiota domains to untangle their interplay [22]. The experimental workflow for generating holo-omic datasets involves:

- Sample Collection and Preparation: Simultaneous collection of host tissue and microbial samples from the same ecological context. For gut holobiont studies, this typically involves mucosal biopsies, luminal content collection, and possibly blood samples for systemic metabolic profiling.

- Multi-omic Profiling: Parallel sequencing and molecular profiling including:

- Host and microbial genomics: Whole genome sequencing of host tissue and shotgun metagenomics of microbial communities [22] [23]

- (Meta)transcriptomics: RNA sequencing of host tissues and microbial communities to assess gene expression patterns [22]

- (Meta)proteomics: Mass spectrometry-based profiling of host and microbial proteins [23]

- (Meta)metabolomics: Untargeted or targeted mass spectrometry to quantify metabolites in host tissues and microbial environments [23]

- Data Integration: Computational integration of multi-omic datasets using specialized algorithms that cluster biological features into modules and cross-correlate features across the host-microbiome boundary [23].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Holobiont Investigations

| Research Reagent | Specific Function | Application Examples in Holobiont Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems [26] | Targeted gene editing in host organisms | Validating host genes involved in response to microbial signals; generating knockout mouse models of inflammasome components |

| Cre-loxP Systems [26] | Tissue/cell-specific gene manipulation | Exploring region-specific host-microbe interactions in gut segments or specialized cell types |

| Organoid Cultures [26] | 3D in vitro models of host tissues | Studying host-microbe interactions in controlled environments; testing predicted metabolic interactions |

| Gnotobiotic Animals [27] | Organisms with defined microbial composition | Establishing causal relationships in host-microbe interactions; testing ecological models of community assembly |

| Multi-objective Optimization Algorithms [24] | Computational prediction of interaction types | Quantifying and predicting competition, neutralism, and mutualism in holobiont systems |

| Genome-scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) [24] | In silico reconstruction of metabolic networks | Predicting nutrient cross-feeding and metabolic interactions between host and microbes |

Protocol for Validating Predicted Metabolic Interactions

To experimentally validate metabolic interactions predicted by community metabolic modeling [24], researchers can implement the following protocol:

In Silico Prediction Phase:

- Construct genome-scale metabolic models for host cells and microbial partners using annotated genomes.

- Apply multi-objective optimization to predict potential metabolic interactions and cross-feeding relationships.

- Identify specific metabolites predicted to be exchanged between organisms (e.g., choline, short-chain fatty acids, amino acids).

Isotope Tracing Experiments:

- Design stable isotope-labeled precursors (e.g., 13C-choline) to track metabolic fluxes.

- Establish co-culture systems with host cells (e.g., intestinal epithelial organoids) and microbial strains.

- Administer labeled compounds and track their transformation and exchange between partners using mass spectrometry.

Genetic Validation:

- Use CRISPR-Cas systems to knockout genes encoding key transporters or metabolic enzymes in host cells [26].

- Generate microbial mutants defective in production or uptake of predicted exchanged metabolites.

- Measure the functional consequences of these genetic perturbations on holobiont fitness parameters.

Functional Assays:

- Assess host cell viability, barrier function, or immune signaling in response to microbial metabolites.

- Measure microbial growth kinetics in the presence versus absence of host-derived factors.

- Quantify system-level outcomes such as resistance to pathogens or recovery from injury.

Holobiont-Informed Therapeutic Development

The holobiont perspective is revolutionizing therapeutic development through the emerging field of pharmacomicrobiomics, which studies the interaction between drugs and the microbiota [28]. This discipline calls for a redefinition of drug targets to include the entire holobiont rather than just the host, acknowledging that host physiology cannot be studied in separation from its microbial ecology [28]. This paradigm shift creates both novel challenges and untapped opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

The recognition that a significant number of drugs originally designed to target host processes unexpectedly affect the gut microbiota [28] necessitates more sophisticated preclinical models that can capture holobiont dynamics. Holobiont animal models that account for the complex interplay between host genetics, microbiota ecology, and environmental pressures are essential for accurate prediction of drug efficacy and safety [28]. Similarly, the understanding that dietary interventions can shape the holobiont phenotype offers promising avenues for microbiota-based personalized medicine [28].

The gut microbiome significantly influences drug metabolism through multiple mechanisms: direct enzymatic transformation of drugs, alteration of host metabolic pathways, modulation of drug bioavailability, and influence on systemic inflammation [28]. These interactions explain the considerable interindividual variation in drug response and highlight the potential of targeting the holobiont to improve therapeutic outcomes.

Future Directions and Synthesis

The integration of synthetic biology with holobiont research represents a promising frontier for both understanding and engineering host-microbiota systems [29]. Emerging approaches include the development of engineered biosensors to detect metabolic exchanges, surface display systems to facilitate specific interactions, and engineered interkingdom communication networks [29]. The concept of de novo holobiont design - which combines tractable hosts with engineered microbiota - could enable the creation of customized systems for biomedical, agricultural, and industrial applications [29].

However, significant challenges remain in holobiont modeling and validation. The immense complexity of microbial communities, combined with the highly varied types and quality of data, creates obstacles in model parameterization and validation [25]. Future methodological developments should focus on enhancing the biological resolution necessary to understand host-microbiome interplay and make meaningful clinical interpretations [23].

The holistic perspective offered by the holobiont concept fundamentally transforms our approach to biology and medicine. As noted in a 2024 review, "John Donne's solemn 400yr old sermon, in which he stated, 'No man is an island unto himself,' is a truism apt and applicable to our non-individual, holobiont existence. For better or for worse, through sickness and health, we are never alone, till death do us part" [21]. This recognition that we are composite beings, integrated with our microbial partners at fundamental metabolic, immune, and cognitive levels, necessitates continued development and refinement of modeling approaches that can capture the exquisite complexity of the holobiont as a single functional unit.

Building and Simulating Community Models: Methods and Biomedical Applications

Stoichiometric models have emerged as indispensable tools for predicting the behavior of complex microbial communities, enabling researchers to simulate metabolic fluxes and interactions at an unprecedented scale. In the context of microbial communities research, these models provide a computational framework to explore microbe-microbe and host-microbe interactions, predict community functions, and identify key species driving ecosystem services [30] [31]. The validation of these models remains a critical challenge, as it determines their reliability in translating computational predictions into biological insights. This guide objectively compares the performance of different methodological approaches across the model development pipeline, supported by experimental data and standardized protocols to ensure reproducible results in drug development and biomedical research.

Phase 1: Model Reconstruction

Reconstruction forms the foundational phase where metabolic networks are built from genomic information and biochemical data.

Genomic Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The initial step involves gathering high-quality genomic data from either isolate genomes or metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). Experimental protocols from recent studies indicate that MAGs should be filtered based on co-assembly type to prevent data redundancy and assessed for quality using tools like CheckM to extract single-copy, protein-coding marker genes [32]. Taxonomic affiliation is then assigned through phylogenetic analysis using maximum-likelihood methods with tools such as IQ-TREE.

For 16S rRNA sequencing data—still widely used due to cost-effectiveness—preprocessing pipelines like QIIME2, Mothur, or USEARCH are employed for denoising, quality filtering, and clustering sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or higher-resolution Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [30]. The final output is an OTU/ASV table representing microbial abundance profiles.

Metabolic Network Reconstruction

Genome-scale metabolic networks (GSMNs) are reconstructed using automated tools that translate genomic annotations into biochemical reaction networks. The metage2metabo (m2m) tool suite exemplifies this approach, utilizing PathwayTools to create PathoLogic environments for each genome and automatically reconstruct non-curated metabolic networks [32]. These reconstructions incorporate metabolic pathway databases such as MetaCyc and KEGG to link genome annotations to metabolism.

Table 1: Comparison of Reconstruction Approaches

| Method | Data Input | Tools | Key Output | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate-Based Reconstruction | Complete microbial genomes | PathwayTools, ModelSEED | Single-organism metabolic models | Misses uncultured organisms |

| Metagenome-Assembled Reconstruction | MAGs from complex communities | metage2metabo (m2m), CheckM | Multi-species metabolic networks | Dependent on assembly quality |

| 16S rRNA-Based Profiling | Amplicon sequences | QIIME2, Mothur, USEARCH | Taxonomic abundance tables | Limited functional resolution |

Experimental Data Integration

Reconstruction quality is enhanced by integrating experimental constraints. Root exudate-mimicking growth media can be implemented as "seed" compounds for predicting producible metabolites, creating nutritionally constrained models [32]. For synthetic microbial community (SynCom) design, metabolic complementarity between bacterial species and host crop plants is analyzed to select minimal communities preserving essential plant growth-promoting traits (PGPTs) while reducing community complexity approximately 4.5-fold [32].

Phase 2: Model Curation

Curation ensures model accuracy through rigorous validation and refinement of metabolic functions.

Quality Control and Functional Validation

Initial curation involves fundamental quality checks to ensure model functionality. The MEMOTE (MEtabolic MOdel TEsts) pipeline provides standardized tests to verify that models cannot generate ATP without an external energy source and cannot synthesize biomass without required substrates [33]. Additional validation includes ensuring biomass precursors can be successfully synthesized across different growth media conditions.

For microbial communities, plant growth-promoting traits (PGPTs) identification serves as functional validation. Protein sequences from MAGs are aligned using BLASTP and HMMER tools against databases like PGPT-Pred, with hits having E-value < 1e−5 considered significant [32]. This confirms the presence of key functional genes involved in nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, exopolysaccharide production, siderophores, and plant growth hormones.

Validation Methodologies

Stoichiometric model validation employs multiple complementary approaches:

Growth/No-Growth Validation: Qualitative assessment comparing model predictions of viability under different substrate conditions against experimental observations. This method validates the existence of metabolic routes but doesn't test accuracy of internal flux predictions [33].

Growth-Rate Comparison: Quantitative evaluation assessing consistency of metabolic network, biomass composition, and maintenance costs with observed substrate-to-biomass conversion efficiency. While informative for overall conversion efficiency, this approach provides limited information about internal flux accuracy [33].

Statistical Validation: For 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), the χ²-test of goodness-of-fit is widely used, though complementary validation methods incorporating metabolite pool size information are increasingly advocated [33].

Table 2: Model Validation Techniques Comparison

| Validation Method | Application Scope | Data Requirements | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goodness-of-Fit (χ²-test) | 13C-MFA | Isotopic labeling data | Statistical rigor | Limited for underdetermined systems |

| Growth/No-Growth | FBA models | Growth phenotype data | Qualitative functional validation | Doesn't test flux accuracy |

| Growth-Rate Comparison | FBA models | Quantitative growth data | Overall efficiency assessment | Uninformative for internal fluxes |

| Van 't Hoff Analysis | Supramolecular complexes | Temperature-dependent data | Thermodynamic validation | Requires multiple conditions |

Thermodynamic Validation

The van 't Hoff analysis provides critical thermodynamic validation for stoichiometric determinations. Recent studies demonstrate that statistical measures alone (e.g., F-test P-values, Akaike information criterion) may insufficiently validate equilibrium models [34]. By performing triplicate titration experiments at multiple temperatures (e.g., 283, 288, 298, 308, 318, and 328 K) and plotting association constants in ln Kn vs. 1/T graphs, researchers can obtain linear fits with R² values >0.93 for valid stoichiometric models, confirming thermodynamic consistency [34].

Phase 3: Model Integration

Integration combines multiple validated models to simulate complex community behaviors and host-microbe interactions.

Multi-Species Community Modeling

Integrated community modeling leverages tools like metage2metabo's cscope command to analyze collective metabolic potentials, incorporating host metabolic networks in SBML file format [32]. This approach enables prediction of cross-feeding relationships and metabolic interdependencies. For synthetic community design, mincom algorithms identify minimal communities that retain crucial functional genes while reducing complexity, enabling targeted manipulation of community structure.

Experimental data from a study designing synthetic communities for plant-microbe interaction demonstrated that in silico selection identified six hub species with taxonomic novelty, including members of the Eremiobacterota and Verrucomicrobiota phyla, that preserved essential plant growth-promoting functions [32].

Temporal Dynamics Forecasting

Advanced integration incorporates temporal dynamics through multivariate time-series analysis. A framework combining singular value decomposition (SVD) and seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models can explain up to 91.1% of temporal variance in community meta-omics data [35]. This approach decomposes gene abundance and expression data into temporal patterns (eigenvectors) and gene loadings, enabling forecasting of community dynamics.

Experimental protocols for temporal forecasting involve:

- Weekly sampling over 14+ months for longitudinal meta-omics data

- SVD to extract relevant temporal patterns clustered into fundamental signals

- ARIMA modeling integrated with environmental parameters

- Model validation using additional samples collected over subsequent years This methodology has demonstrated forecasting correctness for multiple signals and prediction of gene abundance and expression with a coefficient of determination ≥0.87 for three-year projections [35].

Standardization Challenges

Model integration faces significant standardization hurdles. Different metabolic reconstructions often lack harmonization and interoperability, even for the same target organisms [36]. Issues include inconsistent representation formats, variable reconstruction methods, and disparate model repositories. This standardization gap impedes direct model comparison, selection of appropriate models for specific applications, and consistent integration of metabolic with gene regulation and protein interaction networks in multi-omic studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CheckM | Quality assessment of MAGs | Completeness/contamination estimation [32] |

| QIIME2/Mothur | 16S rRNA data processing | OTU/ASV table generation [30] |

| metage2metabo (m2m) | Metabolic network reconstruction | Community metabolic potential analysis [32] |

| MEMOTE | Metabolic model testing | Quality control of stoichiometric models [33] |

| COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-based modeling | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [33] |

| PathwayTools | Metabolic pathway database | Network reconstruction from genomes [32] |

| IQ-TREE | Phylogenetic analysis | Maximum-likelihood tree reconstruction [32] |

| MetaCyc/KEGG | Metabolic pathway reference | Reaction and pathway annotation [32] |

| 3-Hydroxy Bromazepam-d4 | 3-Hydroxy Bromazepam-d4, MF:C14H10BrN3O2, MW:336.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Rhodium(II) triphenylacetate dimer | Rhodium(II) triphenylacetate dimer, MF:C80H64O8Rh2, MW:1359.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Direct comparison of methodological performance reveals trade-offs between computational complexity and predictive accuracy:

Reconstruction Methods: Metagenome-assembled reconstruction captures uncultured diversity but depends heavily on assembly quality, while isolate-based approaches provide complete metabolic networks but miss community context.

Validation Techniques: Growth/no-growth validation offers rapid functional assessment but lacks quantitative precision, while growth-rate comparison provides efficiency metrics but limited internal flux information. Statistical methods like χ²-tests offer rigor but require comprehensive labeling data.

Integration Approaches: Multi-genome metabolic modeling successfully identifies key hub species and minimal communities, with experimental data showing 4.5-fold community size reduction while preserving essential functions [32]. Temporal forecasting models demonstrate high predictive accuracy (R² ≥0.87) for gene expression over multi-year periods when integrating meta-omics with environmental parameters [35].

The continuing development of correction factors for reaction equilibrium constants [37] and standardized validation frameworks [33] [36] addresses current limitations in predicting specific metabolites like methane and hydrogen, pushing the field toward more accurate and reliable stoichiometric modeling of complex microbial communities.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) provide a computational representation of an organism's metabolism, enabling researchers to predict metabolic capabilities and behaviors in silico. The reconstruction and simulation of high-quality GEMs rely heavily on specialized tools and databases. In the context of microbial communities research, selecting the appropriate resource is crucial for generating reliable, predictive models. This guide provides an objective comparison of four key resources—AGORA, BiGG, CarveMe, and RAVEN—focusing on their methodologies, performance, and applications in microbial systems.

Tools and Databases at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, primary functions, and relative advantages of each tool and database.

Table 1: Overview of Key Tools and Databases for Metabolic Modeling

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGORA [38] [39] | Model Repository & Resource | Provides curated, ready-to-use metabolic reconstructions | Focus on human microbiome; includes drug metabolism pathways; manually curated. |

| BiGG [40] [41] | Knowledgebase | Integrates and standardizes published GEMs | Unified namespace (BiGG IDs); integrates over 70 published models; platform for sharing. |

| CarveMe [42] [43] | Reconstruction Tool | Automated reconstruction of species and community models | Top-down, high-speed approach; simulation-ready models; command-line interface. |

| RAVEN [44] [45] | Reconstruction Toolbox | Semi-automated reconstruction, curation, and simulation | MATLAB-based; uses multiple data sources (KEGG, MetaCyc, templates); extensive curation. |

Performance and Validation Data

Independent studies have evaluated the predictive performance of models generated by these resources. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from validation experiments, which typically assess accuracy in predicting experimental outcomes such as substrate utilization and gene essentiality.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Based on Independent Validation Studies

| Resource | Validation Metric | Reported Performance | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGORA2 [38] | Accuracy against 3 experimental datasets | 0.72 - 0.84 | Predictions for metabolite uptake/secretion; outperformed other reconstruction resources. |

| AGORA2 [38] | Prediction of microbial drug transformations | Accuracy: 0.81 | Based on known microbial drug transformations. |

| CarveMe [42] | Reproduction of experimental phenotypes | Close to manually curated models | Performance assessed on substrate utilization and gene essentiality. |

| CarveMe [38] | Flux consistency of reactions | Higher than AGORA2 (P < 1×10â»Â³â°) | Designed to remove flux-inconsistent reactions; comparison of 7,279 strains. |

| RAVEN [44] | Capture of manual curation (S. coelicolor) | Captured most of the iMK1208 model | Benchmarking against a high-quality, manually curated model. |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The resources employ distinct methodologies for reconstruction and validation. Understanding these protocols is essential for interpreting their performance data.

Reconstruction Workflows

The fundamental difference lies in the reconstruction paradigm: CarveMe uses a top-down approach, while RAVEN and the drafts for AGORA use bottom-up approaches.

Detailed Protocols

- Universal Model: Start with a manually curated, simulation-ready universal metabolic model containing no blocked or unbalanced reactions.

- Gene Annotation: Input genome (FASTA format) is aligned against a database of genes with known metabolic functions.

- Reaction Scoring: Alignment scores are mapped to reactions via Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules to determine the likelihood of a reaction's presence.

- Model Carving: A Mixed Integer Linear Program (MILP) solves for a network that maximizes the inclusion of high-scoring reactions while ensuring network connectivity and a minimum growth rate.

- Validation: The resulting model is simulated to predict phenotypes like substrate utilization and gene essentiality, which are compared against experimental data to measure accuracy.

- Data Collection: Genomes are selected, and an extensive manual literature search is conducted for experimental data on metabolic capabilities.

- Draft Reconstruction & Refinement: Draft models are generated (e.g., via KBase) and then refined through the DEMETER pipeline. This involves manual validation of gene functions and integration of literature data.

- Quality Control: Models undergo automated quality checks, including tests for flux consistency, biomass production, and ATP yield on different media.

- Validation: Model predictions are tested against independently collected experimental datasets (e.g., NJC19, Madin) not used during the curation process, calculating accuracy based on the agreement between predictions and experimental observations.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential "research reagents"—critical databases, software, and data formats—required for working with these tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Reconstruction and Modeling

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Purpose | Relevant Tools |

|---|---|---|

| BiGG Database [40] | Standardized namespace and reaction database for consistent model building and sharing. | BiGG, RAVEN, CarveMe |

| KEGG Database [44] | Pathway database used for gene annotation and draft reconstruction. | RAVEN |

| MetaCyc Database [44] | Database of experimentally verified pathways and reactions with curated reversibility. | RAVEN |

| SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) [42] [44] | Standard file format for representing and exchanging models. | All |

| COBRA Toolbox [44] [39] | A MATLAB toolbox for constraint-based modeling and simulation. | All |

| NCBI RefSeq Genome Annotations [40] | Provides standardized genome sequences and annotations for reconstruction. | CarveMe, AGORA2 |

The choice between these resources depends on the research goals:

- For studying the human gut microbiome or host-microbe-drug interactions, AGORA2 offers unparalleled, experimentally validated coverage [38].

- For rapid, large-scale reconstruction of thousands of genomes with reasonable accuracy, CarveMe is the most efficient tool [42] [38].

- For building a highly curated, customized model with extensive manual input and multi-source data integration, the RAVEN toolbox is the most suitable platform [44].

- As a foundational resource, the BiGG database is critical for standardizing and sharing models, ensuring consistency and reproducibility across studies [40].

For microbial community research, the ideal approach may involve using multiple resources in concert, such as employing CarveMe for initial high-throughput reconstruction of community members, followed by refinement and simulation using the standardized knowledge within AGORA and BiGG.

Community Flux Balance Analysis (cFBA) represents a cornerstone computational methodology in constraint-based modeling of microbial ecosystems. By extending the principles of classical FBA to multi-species systems, cFBA enables prediction of metabolic fluxes, species abundances, and metabolite exchanges under the steady-state assumption of balanced growth. This approach is particularly valuable for simulating syntrophic communities in controlled environments such as chemostats and engineered bioprocesses. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of cFBA against alternative modeling frameworks, examining their theoretical foundations, implementation requirements, and performance in predicting community behaviors. We focus specifically on the critical role of the balanced growth assumption and present experimental data validating cFBA predictions against empirical measurements.

Microbial communities drive essential processes across human health, biotechnology, and environmental ecosystems. Deciphering the metabolic interactions within these communities remains a fundamental challenge in systems biology. Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods provide a powerful computational framework for studying these complex systems by leveraging genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). These approaches rely on stoichiometric models of metabolic networks to predict organismal and community behaviors under various environmental conditions [46].

Community Flux Balance Analysis (cFBA) extends the well-established FBA approach from single organisms to microbial consortia. The foundational principle of cFBA involves the application of the balanced growth assumption to the entire community, where all member species grow at the same specific rate, and all intra- and extracellular metabolites achieve steady-state concentrations [47] [48]. This assumption simplifies the complex dynamic nature of microbial ecosystems into a tractable linear optimization problem, enabling predictions of optimal community growth rates, metabolic exchange fluxes, and relative species abundances [47].

The validation of stoichiometric models for microbial communities presents unique challenges, primarily concerning the definition of appropriate objective functions, handling of metabolic interactions, and integration of multi-omics data. cFBA addresses these challenges by considering the comprehensive metabolic capacities of individual microorganisms integrated through their metabolic interactions with other species and abiotic processes [47].

Theoretical Foundations and Key Assumptions

The Balanced Growth Assumption

The balanced growth assumption forms the core mathematical foundation of cFBA. For a microbial community, this condition requires that:

- Constant Growth Rate: All microorganisms in the consortium grow exponentially at the same fixed specific growth rate (μ) [46] [48].

- Metabolic Steady State: The concentration of every metabolic intermediate (both intracellular and extracellular) remains constant over time [47] [46].

This state mirrors the physiological condition of cells in a chemostat or during exponential growth in batch culture [46]. Mathematically, for any metabolite i in the system, the steady-state condition is formalized as:

dci/dt = 0 = S·v - μ·ci

where S is the stoichiometric matrix, v is the flux vector, and ci is the metabolite concentration [46]. This equation ensures that for each metabolite, the rate of production equals the sum of its consumption and dilution by growth.

Mathematical Formulation of cFBA

The cFBA framework integrates individual GEMs into a unified community model. Each organism's metabolic network is represented by its own stoichiometric matrix Sâ‚, Sâ‚‚, ..., Sn, which are combined into a larger community stoichiometric matrix. The method imposes constraints deriving from reaction stoichiometry, reaction thermodynamics (via flux directionality), and ecosystem-level exchanges [47].

The community balanced growth problem can be formulated as a linear optimization problem:

Maximize: μ_community

Subject to:

- S·v = 0 (Mass balance constraints)

- vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax (Capacity constraints)

- vbiomass₠= vbiomass₂ = ... = vbiomassn = μ_community (Balanced growth constraint)

where vbiomassi represents the biomass production flux of organism i [48]. This formulation predicts the maximal community growth rate and the corresponding metabolic flux distribution required to maintain all species in balanced growth.

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Community Modeling Approaches