Validating Microbial Interaction Networks: From Computational Inference to Biomedical Application

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of microbial interaction networks, a critical step for translating computational predictions into reliable biological insights and clinical applications.

Validating Microbial Interaction Networks: From Computational Inference to Biomedical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of microbial interaction networks, a critical step for translating computational predictions into reliable biological insights and clinical applications. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of microbial interactions, reviews cutting-edge qualitative and quantitative inference methodologies, and addresses key challenges in data preprocessing and environmental confounders. A dedicated section on validation strategies offers a comparative analysis of experimental and computational benchmarks, empowering scientists to critically evaluate network models and leverage them for therapeutic discovery, such as predicting microbe-drug associations and combating antibiotic resistance.

The Blueprint of Microbial Societies: Defining Interactions and Network Fundamentals

Microbial communities are complex ecosystems where interactions between microorganisms play a pivotal role in shaping community structure, stability, and function. Understanding these interactions—positive, negative, and neutral—is fundamental to advancing research in microbiology, ecology, and therapeutic development [1]. The validation of inferred microbial interaction networks remains a significant challenge, necessitating a comparative assessment of the methodological tools and approaches used to decipher these intricate relationships [2] [3]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the primary experimental and computational methods used to map microbial interactomes, framing the analysis within the broader thesis of validating network inferences for research and drug development applications.

Microbial Interaction Types: A Ecological Framework

Microbial interactions are typically classified by their net effect on the interacting partners and can be understood through the lens of classical ecology [2] [4] [1].

- Positive Interactions benefit at least one partner. In mutualism, both organisms benefit, often through metabolic exchange (syntrophy) or cooperative behaviors [4] [1]. Commensalism describes a relationship where one organism benefits while the other is unaffected, such as when one microbe alters the environment to make it more favorable for another without cost to itself [2] [4].

- Negative Interactions harm at least one partner. Competition occurs when multiple organisms require the same limited resource, lowering the growth rates of one or both populations [4] [1]. Predation and Parasitism involve one organism consuming or harming another for its own benefit [2] [4]. Amensalism is a unidirectional negative interaction where one organism harms another without receiving benefit or harm, often through the release of toxic compounds [2] [1].

- Neutral Interaction or Neutralism describes an interaction where there is no apparent positive or negative effect on either organism involved [4].

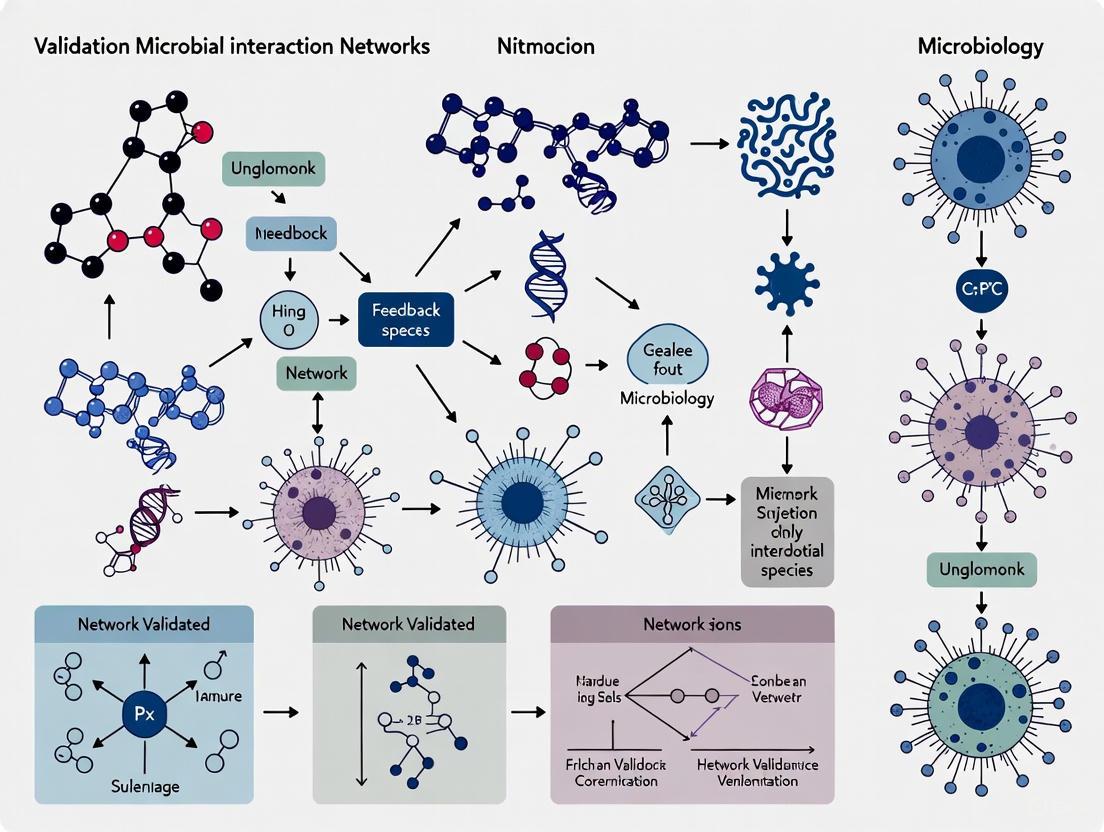

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationships in a microbial interaction network, showing how different species can be interconnected.

Comparative Analysis of Methods for Microbial Network Inference

A range of qualitative and quantitative methods are employed to detect and characterize microbial interactions, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and applicability for network validation [3] [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Methods for Studying Microbial Interactions

| Method Category | Description | Key Applications | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-culture Experiments [1] | Direct cultivation of microbial species together to observe phenotypic changes. | Studying cell-cell contact, spatial arrangement, and metabolite exchange. | Direct observation of directionality and mechanism; mimics in vivo conditions. | Laborious and time-consuming; limited to cultivable microbes. |

| Metabolic Modeling [3] | Predicts metabolic interactions based on genome-scale metabolic networks. | Prediction of syntrophic interactions and nutrient competition. | Provides mechanistic hypotheses for metabolic dependencies. | Quality limited by availability of well-annotated genomes. |

| Co-occurrence Network Inference [2] [3] | Statistical correlation of taxon abundance across many samples to infer associations. | Mapping potential interactions in complex, uncultured communities. | Applicable to high-throughput sequencing data; reveals community-scale structure. | Prone to false positives; reveals correlation, not causation. |

| Advanced Statistical Models (e.g., SGGM) [5] | Uses longitudinal data and Gaussian graphical models to infer conditional dependence networks. | Identifying interactions from irregularly spaced time-series data. | Accounts for data correlation; infers direct conditional interactions. | Sensitive to model assumptions (e.g., zero-inflation, compositionality). |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Construction of Co-occurrence Networks from 16S rRNA Data

This protocol is used to infer potential microbial interactions from high-throughput sequencing data [6].

- Data Collection & Processing: Collect 16S rRNA gene sequencing data from multiple samples. Perform quality filtering, map reads to Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), and annotate against a reference database (e.g., SILVA).

- Network Construction: Calculate pairwise correlations (e.g., Spearman or Pearson) or more advanced conditional independence measures between the abundance of all OTUs across samples.

- Network Analysis: Define nodes (OTUs) and edges (statistical associations). Use network metrics (degree, betweenness centrality) to identify keystone species or hubs. The role of "microbial dark matter" can be assessed by comparing networks constructed with and without unclassified taxa [6].

Protocol 2: Co-culture Assays for Direct Interaction Observation

This qualitative method observes interactions through direct physical cultivation of microbes [1].

- Setup: Cultivate microbial species together in a shared medium (e.g., in a two-chamber assay to separate cells while allowing metabolite exchange, or in a mixed biofilm in a flow cell).

- Incubation & Observation: Observe phenotypic changes using time-lapse imaging, confocal microscopy, or scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Key phenotypes include changes in colony morphology, biofilm structure, and spatial arrangement.

- Metabolite Analysis: Combine with metabolomic analysis (e.g., liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry) to identify cross-fed metabolites, quorum-sensing signals, or inhibitory compounds released during the interaction.

The workflow for integrating these methods to validate an interaction network is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Microbial Interaction Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Two-Chamber Co-culture Systems [1] | Allows observation of indirect microbial interactions via metabolite exchange while preventing physical contact. |

| Fluorescent Labels & Tags [1] | Enable visualization of spatial organization and physical co-aggregation in mixed-species biofilms using microscopy. |

| Reference Databases (e.g., SILVA) [6] | Essential for taxonomic annotation of 16S rRNA sequences and identification of "microbial dark matter." |

| Metabolomics Suites (e.g., LC-MS) [1] | Identify and quantify metabolites, quorum-sensing molecules, and other chemical mediators exchanged between microbes. |

| BRD-9327 | BRD-9327, MF:C22H16BrNO4, MW:438.3 g/mol |

| Binospirone hydrochloride | Binospirone hydrochloride, MF:C20H27ClN2O4, MW:394.9 g/mol |

No single method is sufficient to fully capture the complexity of microbial interactomes. While co-occurrence networks can map potential interactions at scale, they require validation through direct experimental methods like co-culture and metabolomics [3] [1]. The emerging paradigm for robust validation of microbial interaction networks involves an iterative cycle: using high-throughput data to generate hypotheses and infer network structures, then employing targeted experiments and advanced statistical models on longitudinal data to test these hypotheses and establish causality [2] [5]. This multi-faceted approach is critical for translating network inferences into reliable knowledge, ultimately informing the development of novel therapeutic strategies for managing microbiome-associated diseases [2].

Understanding the complex web of interactions within microbial communities is fundamental to deciphering their structure, stability, and function. As microbiome research has evolved, so too has the toolkit available to researchers for mapping these intricate relationships. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the predominant techniques used to infer microbial interactions, from traditional laboratory co-cultures to modern sequencing-based computational approaches. The validation of inferred microbial interaction networks remains a central challenge in the field, requiring careful consideration of each method's strengths, limitations, and appropriate contexts for application. This article objectively examines the performance characteristics of these techniques and provides the experimental protocols necessary for their implementation, serving as a resource for researchers and drug development professionals working to translate microbial ecology insights into therapeutic applications.

Comparative Analysis of Interaction Inference Techniques

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of major microbial interaction inference techniques.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Microbial Interaction Inference Methods

| Method Category | Key Features | Interaction Types Detected | Throughput | Biological Resolution | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pairwise Co-culture | Direct experimental validation; controlled conditions | Competition, mutualism, commensalism, amensalism, exploitation | Low to medium (hundreds to thousands of pairs) [7] | High (strain-level mechanistic insights) | Labor-intensive; may not capture community complexity [8] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling (GSMM) | In silico prediction of metabolic interactions based on genomic data | Metabolic competition, cross-feeding, complementation | High (thousands of predictions) | Moderate (genome-level predictions require experimental validation) | Depends on genome annotation quality; may miss non-metabolic interactions [9] [8] |

| Co-occurrence Network Inference | Statistical analysis of abundance correlations across samples | Putative positive and negative associations | High (community-wide analysis) | Low (correlative only; does not distinguish direct from indirect interactions) | Associations may be driven by environmental factors rather than direct interactions [10] |

| Transcriptomic Analysis | Measures gene expression changes in co-culture conditions | Functional responses; metabolic interactions; stress responses | Medium | High (mechanistic insights into interaction molecular basis) | Resource-intensive; complex data interpretation [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Pairwise Co-culture Interaction Assay

The PairInteraX protocol represents a standardized, high-throughput approach for experimentally determining bacterium-bacterium interaction patterns [7].

Detailed Methodology:

- Strain Preparation: Monocultures of bacterial isolates are established by inoculating 1% (v/v) bacterial suspensions into 5 mL modified Gifu Anaerobic Medium (mGAM) and incubating at 37°C for 72-96 hours under anaerobic conditions (85% N2, 5% CO2, 10% H2).

- Cell Harvesting: Bacterial cells are collected via centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C, then resuspended in mGAM medium adjusted to OD600 = 0.5.

- Co-culture Setup: pairwise co-culture experiments are performed on mGAM agar plates using a standardized coculture strategy. Briefly, 2.5 μL of the first isolate culture is dripped onto the mGAM agar plate surface, followed by the addition of 2.5 μL of another bacterial isolate at external tangency to the first representative isolate.

- Incubation and Data Collection: Following 72-hour incubation at 37°C, interaction results are recorded using a stereo microscope equipped with a digital camera.

- Interaction Classification: Based on growth patterns in mono- versus co-culture, interactions are classified as: neutralism (0/0), commensalism (0/+), exploitation (-/+), amensalism (0/-), or competition (-/-) [7].

Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling for Interaction Prediction

GSMM enables in silico prediction of bacterial interactions by simulating metabolic exchanges within a defined environment [9].

Detailed Methodology:

- Genome Acquisition and Annotation: Retrieve and annotate genomes of target microorganisms from databases such as NCBI or NMDC using annotation tools like Prokka.

- Metabolic Network Reconstruction: Construct metabolic models for each organism, accounting for metabolic capabilities, transport reactions, and biomass composition.

- Media Definition: Define the chemical composition of the growth environment (e.g., artificial root exudate medium for rhizosphere studies) to reflect ecological context.

- Constraint-Based Modeling: Apply flux balance analysis to simulate growth and metabolic exchanges under defined conditions, using tools such as the COBRA toolbox.

- Interaction Scoring: Calculate interaction scores based on the impact of one microorganism's presence on another's growth capability, typically classified as positive (mutualism, commensalism), negative (competition, amensalism), or neutral.

- Validation: Correlate in silico predictions with in vitro growth assays to validate interaction predictions [9].

Transcriptomic Inference of Interactions

Sequencing-based transcriptome analysis identifies transcriptional adaptations to co-culture conditions, revealing mechanisms of interaction.

Detailed Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Establish mono-culture and co-culture conditions for target microorganisms with appropriate biological replicates.

- RNA Extraction and Sequencing: Harvest cells during appropriate growth phase, extract total RNA, and prepare sequencing libraries for transcriptome analysis using platforms such as Illumina.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Map sequencing reads to reference genomes, quantify gene expression levels, and identify statistically significant differentially expressed genes in co-culture versus mono-culture conditions.

- Functional Analysis: Conduct pathway enrichment analysis to identify biological processes significantly altered in co-culture conditions.

- Interaction Inference: Hypothesize specific metabolic interactions based on expression patterns of metabolic pathway genes, such as upregulation of metabolite transport systems and downregulation of biosynthetic pathways for metabolites provided by interaction partners [11].

Visualizing Microbial Interaction Inference Workflows

Diagram 1: Experimental Co-culture Workflow

Diagram 2: Computational Inference Approaches

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below details key reagents and materials essential for implementing microbial interaction inference techniques.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| mGAM Agar | Bacterial co-culture experiments | Rich medium designed to maintain community structure of human gut microbiome; contains diverse prebiotics and proteins [7] | Modified Gifu Anaerobic Medium; composition includes soya peptone, proteose peptone, L-Rhamnose, D-(+)-Cellobiose, Inulin |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Cultivation of anaerobic microbes | Creates oxygen-free environment (typically 85% N2, 5% CO2, 10% H2) for proper growth of anaerobic species [7] | Temperature-controlled (37°C), maintains strict anaerobic conditions |

| Full-length 16S rRNA Sequencing | Strain identification and verification | Provides high-resolution taxonomic classification of bacterial isolates [7] | Enables precise strain-level identification for interaction studies |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | In silico interaction prediction | Computational representations of metabolic networks derived from genomic annotations [9] [8] | Constructed from databases like MetaCyc, KEGG; used for flux balance analysis |

| Synthetic Bacterial Communities (SynComs) | Controlled interaction studies | Defined mixtures of microbial strains for testing specific interaction hypotheses [9] | Typically include marker genes (antibiotic resistance, fluorescence) for tracking |

| LRI Databases | Cell-cell interaction inference | Curated databases of ligand-receptor pairs for predicting intercellular signaling [12] | Examples: CellPhoneDB, CellChat; include protein subunits, activators, inhibitors |

| PF-5274857 hydrochloride | PF-5274857 hydrochloride, MF:C20H26Cl2N4O3S, MW:473.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 4-Iodo-SAHA | 4-Iodo-SAHA, CAS:1219807-87-0, MF:C14H19IN2O3, MW:390.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The field of microbial interaction inference has diversified considerably, with methods ranging from traditional co-culture experiments to sophisticated computational approaches. While high-throughput sequencing and omics technologies have enabled unprecedented scale in interaction mapping, each method carries distinct advantages and limitations for network validation. Pairwise co-culture remains the gold standard for experimental validation but scales poorly, while computational methods like GSMM and co-occurrence network analysis offer scalability at the cost of direct mechanistic evidence. Transcriptional approaches provide valuable insights into interaction mechanisms but require careful interpretation. The most robust understanding of microbial interaction networks emerges from the strategic integration of multiple complementary approaches, leveraging the strengths of each to overcome their respective limitations. As the field advances, addressing challenges such as rare taxa, environmental confounding, and higher-order interactions will be essential for generating predictive models of microbial community dynamics with applications in drug development and therapeutic intervention.

Graph theory provides a powerful mathematical framework for representing and analyzing complex biological systems. In this context, biological networks represent interactions among molecular or organismal components, where nodes (or vertices) symbolize biological entities such as proteins, genes, or microbial species, and edges (or links) represent the physical, functional, or statistical interactions between them [13] [14]. The network topology—the specific arrangement of nodes and edges—holds crucial information about the system's structure, function, and dynamics. The application of network science to biology has become instrumental for deciphering how numerous components and their interactions give rise to functioning organisms and communities, with graph theory serving as a universal language across different biological scales from molecular pathways to ecosystems [15].

In microbial ecology specifically, network inference—the process of reconstructing these interaction networks from experimental data—remains a fundamental challenge [16] [15]. Microbial interaction networks typically represent bacteria, archaea, or other microorganisms as nodes, with edges depicting various relationship types including competition, cooperation, predation, or commensalism. The accurate topological analysis of these networks enables researchers to predict community assembly, stability, and functional outcomes, which is essential for applications in human health, environmental science, and biotechnology [16].

Key Concepts: Nodes, Edges, and Network Topology

Fundamental Graph Elements

In biological network analysis, the precise definition of nodes and edges varies depending on the biological context and research question. Nodes can represent a diverse range of biological entities: in protein-protein interaction networks, nodes are individual proteins; in gene regulatory networks, nodes represent genes or transcription factors; in metabolic networks, nodes signify metabolites or enzymes; and in microbial coexistence networks, nodes correspond to different microbial species or operational taxonomic units (OTUs) [14] [15]. The definition of these nodes is a critical methodological decision that directly influences the resulting network topology and biological interpretation.

Edges represent the interactions or relationships between nodes and can be characterized by several properties. Edges may be directed or undirected, indicating whether the interaction is asymmetric (e.g., Gene A regulates Gene B) or symmetric (e.g., Protein A physically binds to Protein B) [17] [15]. Additionally, edges may be weighted or unweighted, where weights quantify the strength, confidence, or magnitude of the interaction. In microbial networks, edges often represent inferred ecological relationships based on statistical associations from abundance data, though they can also represent experimentally confirmed interactions [15].

Network Topology and Biological Significance

Network topology refers to the structural arrangement of nodes and edges, which can reveal fundamental organizational principles of biological systems. Key topological features include:

- Degree distribution: The pattern of connectivity across nodes, where degree represents the number of connections a node has. Biological networks often exhibit "scale-free" properties where few nodes have many connections while most nodes have few connections.

- Modularity: The extent to which a network is organized into densely connected subgroups (modules) with sparse connections between them. In biological systems, modules often correspond to functional units.

- Centrality measures: Metrics that identify particularly important nodes within a network, such as betweenness centrality (nodes that lie on many shortest paths) or eigenvector centrality (nodes connected to other well-connected nodes) [14] [18].

In microbial networks, specific topological patterns can indicate functional properties of the community. For instance, highly connected, central nodes (often called "hubs") may represent keystone species whose presence is critical for community stability, while modular structure may reflect functional guilds or niche-specific associations [16].

Computational Frameworks for Network Inference and Analysis

Static Versus Dynamic Network Models

Computational approaches for inferring biological networks from data can be broadly categorized into static and dynamic methods. Static network models capture correlative relationships between entities, typically using correlation coefficients, mutual information, or other association measures computed across multiple samples or conditions [15]. While these methods can address complex communities of thousands of species and have been successfully applied to identify co-occurrence patterns in microbial communities, they usually ignore the asymmetry of relationships and cannot capture temporal dynamics [15].

Dynamic network models, in contrast, explicitly incorporate time and can represent the causal or directional influences between entities. Two prominent frameworks for dynamic network inference are Lotka-Volterra (LV) models and Multivariate Autoregressive (MAR) models [15]. LV models are based on differential equations originally developed to describe predator-prey dynamics and have since been extended to various microbial systems. MAR models are statistical models that represent each variable as a linear combination of its own past values and the past values of other variables in the system. Each framework has distinct strengths: LV models generally superior for capturing non-linear dynamics, while MAR models perform better for networks with process noise and near-linear behavior [15].

Knowledge Graph Embedding and Machine Learning Approaches

Knowledge graph embedding is an emerging approach that learns representations of biological entities and their interactions in a continuous vector space [16]. This method has shown promising results for predicting pairwise microbial interactions while minimizing the need for extensive in vitro experimentation. In one application to soil bacterial strains cocultured in different carbon source environments, knowledge graph embedding accurately predicted interactions involving strains with missing culture data and revealed similarities between environmental conditions [16].

Advanced graph neural networks (GNNs) and explanation frameworks like ExPath represent the cutting edge of biological network analysis [18]. These methods can integrate experimental data with prior knowledge from biological databases to infer context-specific subnetworkes or pathways. The ExPath framework, for instance, combines GNNs with state-space sequence modeling to capture both local interactions and global pathway-level dependencies, enabling identification of targeted, data-specific pathways within broader biological networks [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Network Inference Methods for Microbial Communities

| Method Type | Representative Approaches | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static Models | Correlation networks, Mutual information | Computational efficiency for large communities; Identifies co-occurrence patterns | Ignores directionality and dynamics; Prone to spurious correlations | Initial exploration of community structure; Large-scale screenings |

| Dynamic Models | Lotka-Volterra, Multivariate Autoregressive | Captures temporal dynamics and directionality; Reveals causal relationships | Computationally intensive; Requires dense time-series data | Investigating community succession; Perturbation response studies |

| Knowledge Graph Embedding | Translational embedding, Neural network-based | Predicts missing interactions; Reveals latent similarities | Requires structured knowledge base; Black-box interpretations | Integrating heterogeneous data; Prediction of novel interactions |

| Graph Neural Networks | GNNExplainers, ExPath | Integrates experimental data; Captures complex non-linear patterns | High computational demand; Complex implementation | Condition-specific pathway identification; Mechanism discovery |

Experimental Validation of Microbial Interaction Networks

Methodologies for Network Inference

Experimental validation of microbial interaction networks requires careful methodological consideration across study design, data collection, computational analysis, and experimental validation. For dynamic network inference using Lotka-Volterra models, the core methodology involves collecting high-resolution time-series data of microbial abundances, then applying linear regression methods to estimate interaction parameters from the differential equations [15]. The generalized Lotka-Volterra model represents the population dynamics of multiple microbial species with equations that include terms for intrinsic growth rates and pairwise interaction coefficients, which can be estimated from abundance data.

For knowledge graph embedding approaches, the experimental protocol involves several key stages [16]. First, researchers construct a knowledge graph where nodes represent microbial strains and environmental conditions, while edges represent observed interactions or associations. Embedding algorithms then learn vector representations for each node that preserve the graph structure in a continuous space. These embeddings enable prediction of unobserved interactions through vector operations. Validation typically involves hold-out testing, where a subset of known interactions is withheld during training and used to assess prediction accuracy.

Logical digraphs provide another formal framework for representing regulatory interactions in biological systems [17]. This approach uses Boolean logic to define the dynamics of interacting elements, where each element can exist in an active (1) or inactive (0) state, and transfer functions define how elements influence each other. The framework incorporates eight core logical connectives to represent different interaction types, enabling precise representation of complex regulatory logic. This method has been applied to analyze neural circuits and gene regulatory networks, demonstrating its utility for identifying attractors and limit cycles in biological systems [17].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a generalized computational workflow for inferring and validating microbial interaction networks, integrating elements from multiple methodological approaches:

Diagram 1: Computational workflow for microbial network inference

Comparative Analysis of Network Inference Methods

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

Rigorous comparison of network inference methods requires standardized performance metrics that assess both topological accuracy and biological relevance. For microbial interaction networks, key evaluation criteria include:

- Topological accuracy: How well the inferred network structure matches known biological interactions, typically measured by precision, recall, and F1-score when ground truth data is available.

- Predictive performance: The ability to predict unobserved interactions or dynamic behaviors, assessed through cross-validation or hold-out testing.

- Biological relevance: The extent to which inferred networks align with established biological knowledge or generate testable hypotheses, often evaluated through functional enrichment analysis or literature validation.

In a comparative study of Lotka-Volterra versus Multivariate Autoregressive models, researchers found that while both approaches can successfully infer network structure from time-series data, their relative performance depends on system characteristics [15]. LV models generally outperformed MAR models for systems with strong non-linear dynamics, while MAR models were superior for systems with significant process noise and near-linear behavior. This highlights the importance of selecting inference methods based on the specific characteristics of the microbial system under investigation.

For knowledge graph embedding methods, evaluation using soil bacterial datasets demonstrated high accuracy in predicting pairwise interactions, with the additional advantage of predicting interactions for strains with missing culture data [16]. The embedding approach also enabled the identification of similarities between carbon source environments, allowing prediction of interactions in one environment based on outcomes in similar environments.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Network Inference Methods Based on Published Studies

| Method Category | Prediction Accuracy | Handling of Missing Data | Computational Efficiency | Biological Interpretability | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Networks | Moderate | Poor | High | Moderate | Low |

| Lotka-Volterra Models | High for non-linear systems | Moderate | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Multivariate Autoregressive | High for linear systems with noise | Moderate | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Knowledge Graph Embedding | High | Excellent | Moderate to High | Moderate | High |

| Graph Neural Networks | Very High | Good | Low | Moderate to High | Very High |

Case Study: Microbial Interaction Prediction in Soil Bacteria

A concrete application of network inference methods comes from a study predicting interactions among 20 soil bacterial strains across 40 different carbon source environments using knowledge graph embedding [16]. The experimental protocol involved several key steps:

Data Collection: Measuring pairwise interaction outcomes (positive, negative, or neutral) for all strain combinations across multiple environmental conditions.

Knowledge Graph Construction: Creating a graph where nodes represented bacterial strains and carbon sources, with edges representing observed interactions and environmental conditions.

Embedding Learning: Training embedding algorithms to represent each node in a continuous vector space while preserving the graph structure.

Interaction Prediction: Using the learned embeddings to predict unobserved interactions through vector operations.

The results demonstrated that knowledge graph embedding achieved high prediction accuracy for pairwise interactions, successfully predicted interactions involving strains with missing data, and identified meaningful similarities between carbon source environments. This enabled the design of a recommendation system to guide microbial community engineering, highlighting the practical utility of network inference approaches for biotechnology applications [16].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Network Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Databases | KEGG, STRING | Provide prior knowledge of molecular interactions | Network construction and validation |

| Computational Frameworks | ExPath, PathMamba | Infer targeted pathways from experimental data | Condition-specific network inference |

| Dynamic Modeling Tools | Lotka-Volterra solvers, MAR algorithms | Model temporal dynamics of interacting species | Time-series analysis of microbial communities |

| Visualization Platforms | Graphviz, Cytoscape | Create biological network diagrams | Network representation and exploration |

| Color Accessibility Tools | Viz Palette, ColorBrewer | Ensure accessible color schemes in visualizations | Creation of inclusive scientific figures |

The application of graph theory to biological systems has revolutionized our ability to represent, analyze, and predict the behavior of complex microbial communities. Different network inference methods—including static correlation networks, dynamic models like Lotka-Volterra and Multivariate Autoregressive systems, knowledge graph embeddings, and advanced graph neural networks—each offer distinct advantages and limitations. The choice of method should be guided by the specific research question, data characteristics, and analytical goals.

As the field advances, key challenges remain in improving the accuracy of network inference, particularly for large-scale microbial communities, and in enhancing the integration of heterogeneous data types. The development of standardized evaluation frameworks and benchmark datasets will be crucial for rigorous comparison of methods. Ultimately, network-based approaches provide powerful frameworks for unraveling the complexity of microbial systems, with promising applications in microbiome engineering, therapeutic development, and ecological management.

Building the Network: From Omics Data to Predictive Models

The study of microbial interactions represents a critical frontier in understanding complex biological systems, from human health to environmental science. Traditional monoculture methods often fail to recapitulate the intricate ecological contexts where microorganisms naturally exist, limiting their predictive value in real-world scenarios. High-throughput experimental systems have emerged as powerful tools to overcome these limitations, enabling researchers to investigate polymicrobial interactions with unprecedented scale and precision. Among these technologies, microfluidic droplet systems and advanced co-culture assays have demonstrated particular promise for mapping microbial interaction networks, offering robust platforms for quantifying population dynamics, metabolic exchanges, and community responses to perturbations.

These technologies have evolved significantly from early co-culture methods that were typically poorly defined in terms of cell ratios, local cues, and supportive cell-cell interactions [19]. Modern implementations now provide exquisite control over cellular microenvironments while enabling high-throughput screening of interaction parameters. The application of these systems spans fundamental microbial ecology, drug discovery, and bioproduction optimization, where understanding interspecies dynamics is essential for predicting community behavior and engineering consortia with desired functions. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of leading high-throughput co-culture platforms, with a specific focus on their applicability to validating microbial interaction networks.

Technology Comparison: Performance Characteristics and Applications

The selection of an appropriate high-throughput co-culture system depends heavily on research objectives, required throughput, and the specific biological questions being addressed. Below, we compare the key performance characteristics of major technological approaches, highlighting their respective advantages and limitations for studying microbial interactions.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of High-Throughput Co-culture Systems

| Technology | Throughput Capacity | Spatial Control | Temporal Resolution | Single-Cell Resolution | Label-Free Operation | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet Microfluidics | High (Thousands of cultures) [20] | Moderate (3D confinement in picoliter droplets) [20] | High (Minute-scale imaging intervals) [20] | Yes (AI-based morphology identification) [20] | Yes (Brightfield microscopy with deep learning) [20] | Bacterial-phage interactions, polymicrobial dynamics, growth/lysis kinetics |

| Cybernetic Bioreactors | Low (Single culture) [21] | Low (Well-mixed) [21] | Moderate (Minute-scale composition measurements) [21] | No (Population-averaged measurements) [21] | Partial (Requires natural fluorophores for estimation) [21] | Long-term co-culture stabilization, bioproduction optimization, composition control |

| Microfluidic Hydrogel Beads | High (Combinatorial encapsulation) [19] | High (Cell patterning in microgels) [19] | Low (Typically endpoint analysis) [19] | Limited (Fluorescence-dependent) [19] | No (Requires fluorescent reporters) [19] | Paracrine signaling studies, stem cell niche interactions, growth factor screening |

Table 2: Quantitative Experimental Capabilities Across Platforms

| Platform | Typical Culture Volume | Maximum Duration | Species Identification Method | Encapsulation Control | Real-time Monitoring | Automated Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet Microfluidics | 11 picolitres [20] | 20 hours [20] | Morphology-based deep learning [20] | Poisson distribution [20] | Yes (5-minute intervals) [20] | Limited (Environmental control only) |

| Cybernetic Bioreactors | 20 milliliters [21] | 7 days (~250 generations) [21] | Natural fluorescence + growth kinetics [21] | Initial inoculation ratio [21] | Yes (Minute-scale OD/fluorescence) [21] | Yes (Real-time PI control) [21] |

| Microfluidic Hydrogel Beads | Nanolitre to microlitre scale [19] | Hours to days (Endpoint) [19] | Fluorescent labeling [19] | Flow rate control [19] | Limited | No |

The performance data reveals a clear trade-off between throughput and long-term control capabilities. Microfluidic droplet systems excel in high-resolution, short-to-medium term studies of microbial interactions at the single-cell level, while cybernetic bioreactors provide superior long-term composition control despite lower throughput. The choice between label-free morphological identification versus fluorescence-based tracking further distinguishes these platforms, with significant implications for experimental design and potential microbial perturbation.

Experimental Protocols for Microbial Interaction Studies

Microfluidic Droplet Platform for Polymicrobial-Phage Interactions

The droplet microfluidics approach enables label-free quantification of bacterial co-culture dynamics with phage involvement through a carefully optimized protocol [20]:

Day 1: Device Preparation and Bacterial Culture

- Fabricate microfluidic device featuring droplet generation and trapping geometry using standard soft lithography techniques.

- Prepare bacterial strains P. aeruginosa PA14 ΔflgK and S. aureus MSSA476 in appropriate liquid media, growing to mid-exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5).

- Propagate and purify P. aeruginosa phage P278 using standard phage amplification protocols, determining stock concentration via plaque assay.

Day 2: Droplet Generation and Loading

- Connect microfluidic device to pressure-controlled pumps and sterile filters.

- Prepare aqueous phase containing co-culture mixture with approximately 10ⶠCFU/mL total bacterial density with desired species ratio and 10ⷠPFU/mL phage stock in growth media.

- Load oil phase (fluorinated oil with 2% biocompatible surfactant) into designated reservoir.

- Generate 11 picolitre droplets at approximately 1000 Hz generation rate, collecting droplets in device trapping array or off-chip for incubation.

- Verify droplet size and loading efficiency via brightfield microscopy.

Day 2-3: Time-Lapse Imaging and Analysis

- Mount device on automated microscope stage with environmental control (appropriate temperature).

- Program Z-stack acquisition (approximately 6-8 slices at 1µm intervals) every 5 minutes for up to 20 hours using AI-based autofocus system.

- Process images through deep learning pipeline: (1) Apply YOLOv8-based classifier for focal plane correction, (2) Segment individual droplets using Hough transform, (3) Identify and count bacterial cells by morphology (rod-shaped vs. cocci) using convolutional neural networks.

- Quantify species-specific growth rates, population dynamics, and lysis events from time-series data.

Cybernetic Control of Co-culture Composition

This protocol enables long-term stabilization of two-species co-cultures through real-time monitoring and actuation [21]:

Week 1: Monoculture Characterization

- Cultivate P. putida OUS82 (lapA knockout) and E. coli in separate bioreactors across temperature gradient (e.g., 28-38°C).

- Measure growth rates (via OD₆₅₀) and natural fluorescence (excitation 395nm/emission 440nm for P. putida pyoverdine) at 1-minute intervals.

- Parameterize Monod-like growth models for each species relating temperature to growth rate.

Week 2: Co-culture Implementation and Controller Setup

- Inoculate co-culture with desired initial ratio (e.g., 1:1) in Chi.bio or similar bioreactor with turbidostat operation (OD setpoint 0.2).

- Implement Extended Kalman Filter to estimate composition from combined OD and fluorescence measurements.

- Program Proportional-Integral (PI) control algorithm to adjust temperature based on composition error (difference between estimated and desired composition).

- Set temperature actuation range (typically 30-36°C) based on characterized growth differential.

Week 2-3: Long-term Control Operation

- Initiate control loop with composition setpoint, allowing temperature adjustments every generation.

- Sample periodically for validation via flow cytometry or plating.

- Monitor for escape mutations or controller instability, adjusting parameters if necessary.

- For dynamic tracking experiments, implement time-varying composition references.

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows and system architectures for the featured high-throughput co-culture platforms, created using DOT language with compliance to specified color and contrast guidelines.

Diagram Title: Microfluidic Droplet Workflow

Diagram Title: Cybernetic Control System

Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Co-culture Studies

The successful implementation of high-throughput co-culture studies requires careful selection of reagents and materials that maintain cell viability while enabling precise monitoring and control. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in microbial interaction studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for High-Throughput Co-culture Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes | Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorinated Oil with 2% Surfactant | Forms immiscible phase for water-in-oil droplet generation | Prevents droplet coalescence, maintains structural integrity | Compatible with most bacterial cultures; oxygen-permeable formulations available |

| Matrigel/ECM Hydrogels | Provides 3D scaffold for cell growth and signaling | Enables complex tissue modeling in organoid systems | Temperature-sensitive gelling; composition varies by batch |

| Natural Fluorescent Reporters (e.g., Pyoverdine) | Enables label-free species identification | P. putida produces pyoverdine (ex395/em440) [21] | Species-specific; non-invasive monitoring |

| Selective Growth Media | Supports specific microbial groups while inhibiting others | Enables quantification via plating validation | May alter natural competition dynamics |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Genetic editing for mechanistic studies | Enables insertion of markers or gene knockouts | Requires optimization for each microbial species |

| Antibiotic Resistance Markers | Selection for specific strains in consortia | Maintains desired composition in validation studies | Ecological relevance concerns; potential fitness costs |

| Microfluidic Device Materials (PDMS) | Device fabrication with gas permeability | Suitable for long-term bacterial culture | May absorb small molecules; surface treatment often required |

High-throughput co-culture systems have fundamentally transformed our ability to study microbial interactions under controlled yet ecologically relevant conditions. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that technology selection involves inherent trade-offs: microfluidic droplet platforms offer unparalleled single-cell resolution and throughput for short-to-medium term studies, while cybernetic bioreactors provide exceptional long-term composition control despite lower parallelism. The emergence of label-free monitoring techniques, particularly morphology-based deep learning approaches, represents a significant advancement for minimizing perturbation during data acquisition.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on increasing system complexity while maintaining high throughput, potentially through hierarchical designs that combine droplet-based initiation with larger-scale cultivation. Similarly, the integration of multi-omics sampling capabilities within these platforms would provide unprecedented insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying observed ecological dynamics. As these technologies continue to mature, they will play an increasingly vital role in validating microbial interaction networks, ultimately enhancing our ability to predict, manipulate, and engineer microbial communities for biomedical and biotechnological applications.

In the field of microbial ecology, understanding the intricate web of interactions within communities is paramount to deciphering their structure and function. This guide explores the computational inference engines that empower researchers to move beyond simple correlation measures to more robust network models. Specifically, we focus on the evolution from correlation networks to Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs) and modern machine learning approaches, providing a structured comparison of their methodologies, performance, and applicability in validating microbial interaction networks. As the volume and complexity of microbial data grow, selecting the appropriate inference engine becomes critical for generating accurate, biologically relevant insights that can inform downstream applications in therapeutic development and microbiome engineering.

Correlation Measures vs. Gaussian Graphical Models

Correlation Networks

Correlation networks are constructed by computing sample Pearson correlations between all pairs of nodes (e.g., microbial species) and drawing edges where correlation exceeds a defined threshold [22]. While simple to implement and interpret, this approach has a significant drawback: it captures both direct and indirect associations, potentially leading to spurious edges that do not represent direct biological dependencies [22].

For example, consider three microbial species A, B, and C, where A upregulates B and B upregulates C. A correlation network might show an edge between A and C, even though their correlation is strictly driven through their mutual relationship with B [22]. This occurs because Pearson correlation measures the net effect of all pathways between two nodes, making it a "network-level" statistic that confounds direct and indirect effects [22].

Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs)

GGMs address this limitation by using partial correlations—the correlation between two nodes conditional on all other nodes in the network [22]. This approach effectively controls for the influence of indirect pathways, making it more likely that edges represent direct biological interactions. In the three-species example, the partial correlation between A and C would be zero, correctly resulting in no edge between them [22].

The mathematical relationship between the correlation matrix C and partial correlation matrix P is given by:

C = Dâ»Â¹Aâ»Â¹Dâ»Â¹

where the (i,j) entry of A is -Ï€{ij} for i≠j and 1 for i=j, and D is a diagonal matrix with dii equal to the square root of the (i,i) entry of Aâ»Â¹ [22].

The Pair-Path Subscore (PPS) for Path-Level Interpretation

A challenge in using GGMs is interpreting how specific paths contribute to overall correlations. The Pair-Path Subscore (PPS) method addresses this by scoring individual network paths based on their relative importance in determining Pearson correlation between terminal nodes [22].

For a simple three-node network with nodes 1, 2, and 3, the correlation câ‚â‚‚ can be expressed as:

câ‚â‚‚ = (Ï€â‚â‚‚ + Ï€â‚₃π₃₂) / (√(1-π₂₃²) √(1-Ï€â‚₃²))

The numerator represents the sum of products of partial correlations along all paths connecting nodes 1 and 2: the direct path (Ï€â‚â‚‚) and the path through node 3 (Ï€â‚₃π₃₂) [22]. PPS leverages this relationship to decompose correlations into path-specific contributions, enabling finer-scale network analysis.

Experimental Workflow for Microbial Network Inference

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for inferring microbial interaction networks using these different computational approaches:

Diagram 1: Workflow for microbial network inference, comparing correlation-based and GGM-based approaches.

Advanced Machine Learning Approaches

Knowledge Graph Embedding

Recent approaches have leveraged knowledge graph embedding to predict microbial interactions while minimizing labor-intensive experimentation [16]. This method learns representations of microorganisms and their interactions in an embedding space, enabling accurate prediction of pairwise interactions even for strains with missing culture data [16].

A key advantage of this framework is its ability to reveal similarities between environmental conditions (e.g., carbon sources), enabling prediction of interactions in one environment based on outcomes in similar environments [16]. This approach also facilitates recommendation systems for microbial community engineering.

Comparison of Inference Methods for Microbial Networks

The table below summarizes the key computational approaches used for inferring microbial interaction networks:

Table 1: Comparison of microbial network inference methods

| Method | Underlying Principle | Strengths | Limitations | Experimental Validation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Networks | Pairwise Pearson correlation | Simple implementation and interpretation | Prone to spurious edges from indirect correlations [22] | Coculture experiments to verify direct interactions [3] |

| Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs) | Partial correlation conditioned on all other nodes | Filters out indirect correlations [22] | Quality depends on well-annotated genomes [3] | Metabolic modeling to verify predicted dependencies [3] |

| Pair-Path Subscore (PPS) | Decomposes correlation into path contributions | Enables path-level interpretation of networks [22] | Limited to linear relationships | Targeted validation of specific pathways [22] |

| Knowledge Graph Embedding | Embedding entities and relations in vector space | Predicts interactions with minimal experimental data [16] | Requires large dataset for training | Validation of predicted interactions in select environments [16] |

| Coculture Experiments | Direct experimental observation of interactions | Identifies both direct and indirect interactions [3] | Laborious and time-consuming [3] | Self-validating through direct measurement |

Computational Inference Engines: Performance Comparison

In 2025, specialized AI inference providers have emerged as powerful solutions for running computational models at scale, offering optimized performance for various workloads [23]. These platforms provide the underlying infrastructure for executing trained models efficiently, balancing latency, throughput, and cost [23].

Inference engines optimize model performance through techniques like graph optimization, hardware-specific optimization, precision lowering (quantization), and model pruning [24]. For microbial network inference, which often involves large-scale genomic and metabolomic data, these platforms can significantly accelerate computational workflows.

Performance Benchmarking of Inference Engines

The table below compares leading AI inference platforms based on key performance metrics relevant to computational biology research:

Table 2: Performance comparison of AI inference platforms in 2025

| Platform | Optimization Features | Hardware Support | Latency Performance | Cost Efficiency | Relevance to Microbial Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ONNX Runtime | Cross-platform optimization, graph fusion [24] | CPU, CUDA, ROCm [24] | Varies by execution provider | High (open-source) | Flexible deployment for custom models |

| NVIDIA TensorRT-LLM | Kernel fusion, quantization, paged KV caching [24] | NVIDIA GPUs [24] | Ultra-low latency | Medium | High-performance for large models |

| vLLM | PagedAttention, continuous batching [23] | NVIDIA GPUs [23] | Up to 30% higher throughput [23] | High | Efficient for transformer-based models |

| GMI Cloud Inference Engine | Automatic scaling, quantization [25] | NVIDIA H200, Blackwell [25] | 65% reduction in latency reported [25] | 45% lower compute costs [25] | Managed service for production workloads |

| Together AI | Token caching, model quantization [26] | Multiple GPU types [26] | Sub-100ms latency [26] | Up to 11x more affordable than GPT-4 [26] | Access to 200+ open-source models |

Inference Engine Architecture and Optimization Techniques

Modern inference engines employ sophisticated optimization techniques to maximize performance:

Diagram 2: Model optimization workflow in modern inference engines.

Key optimization strategies include:

- Graph Optimization: Analyzing computational graphs to fuse operations and remove redundancies [24]

- Precision Reduction: Quantizing models from FP32 to lower precision (FP16, INT8, INT4) to reduce memory footprint and increase speed [24]

- Hardware-Specific Optimization: Using specialized kernels tuned for specific accelerators (GPUs, TPUs) [24]

- Dynamic Batching: Grouping multiple requests to improve GPU utilization [23]

- Caching: Reusing computed results for repeated queries, potentially reducing costs by 20-40% [23]

Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Validation

Computational predictions of microbial interactions require experimental validation. The table below outlines key reagents and methodologies used in this process:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and methods for validating microbial interactions

| Reagent/Method | Function in Validation | Application Context | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coculture Assays | Direct observation of microbial interactions in controlled environments [3] | Testing predicted pairwise interactions | Laborious and time-consuming [3] |

| Metabolomic Profiling | Measuring metabolite abundance to infer metabolic interactions [22] | Validating predicted metabolic dependencies | Requires specialized instrumentation |

| Carbon Source Variants | Testing interaction stability across different nutritional environments [16] | Assessing context-dependency of interactions | Enables knowledge transfer between environments |

| Flux Balance Analysis | Predicting metabolic interactions from genomic data [3] | Genome-scale modeling of metabolic networks | Limited by genome annotation quality [3] |

| Isolated Bacterial Strains | Obtaining pure cultures for controlled interaction experiments [3] | Fundamental requirement for coculture studies | Availability can limit experimental scope |

The validation of microbial interaction networks relies on a sophisticated toolkit of computational inference engines, from foundational statistical models like Gaussian Graphical Models to modern AI platforms. Correlation measures provide an accessible starting point but risk inferring spurious relationships, while GGMs offer more robust identification of direct interactions through conditional dependence. The emerging generation of AI inference engines dramatically accelerates these computations, enabling researchers to work with larger datasets and more complex models. However, computational predictions remain hypotheses until validated experimentally through coculture studies, metabolomic profiling, and other laboratory methods. The integration of powerful computational inference with careful experimental validation represents the most promising path forward for unraveling the complex web of microbial interactions that shape human health and disease.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have emerged as indispensable mathematical frameworks for simulating the metabolism of archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotic organisms [27]. By defining the relationship between genotype and phenotype, GEMs contextualize multi-omics Big Data to provide mechanistic, systems-level insights into cellular functions [27]. As the field progresses, consensus approaches that integrate models from multiple reconstruction tools are demonstrating enhanced predictive performance and reliability, particularly in the validation of complex microbial interaction networks [28].

Foundations of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

GEMs are network-based tools that represent the complete set of known metabolic information of a biological system, including genes, enzymes, reactions, associated gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules, and metabolites [27]. They provide a structured knowledge base that can be simulated to predict metabolic fluxes and phenotypic outcomes under varying conditions.

Core Components and Simulation Approaches

- Mathematical Representation: GEMs mathematically formulate the biochemical transformations within a cell, tissue, or organism, linking the genotype to metabolic phenotypes [27] [29].

- Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA): This methodology uses mass-balance, thermodynamic, and capacity constraints to define the set of possible metabolic behaviors without requiring kinetic parameters [30].

- Key Simulation Techniques:

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): Optimizes an objective function (e.g., biomass production) to predict steady-state reaction fluxes [27] [29].

- Dynamic FBA (dFBA): Extends FBA to simulate time-dependent changes in the extracellular environment and microbial community dynamics [27] [31].

- Flux Space Sampling: Generates a probabilistic distribution of possible flux states without assuming a single biological objective, enabling comprehensive exploration of metabolic capabilities [29].

Table 1: Key Methods for Simulating and Analyzing GEMs

| Method | Core Principle | Primary Application | Key Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Optimization of a biological objective function (e.g., growth) under steady-state constraints [27]. | Predicting growth rates, nutrient uptake, and byproduct secretion [27] [32]. | Assumption of a cellular objective; definition of nutrient constraints. |

| Flux Space Sampling | Statistical sampling of the entire space of feasible flux distributions [29]. | Characterizing network redundancy and comparing metabolic states without a predefined objective [29]. | Computationally intensive for very large models. |

| 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C MFA) | Uses isotopic tracer data to determine intracellular flux maps [27]. | Experimental validation and precise quantification of in vivo metabolic fluxes [27]. | Expensive experimental data from isotopic labeling. |

| Dynamic FBA | Integrates FBA with changes in extracellular metabolite concentrations over time [27] [31]. | Modeling batch cultures, microbial community dynamics, and host-microbe interactions [27] [31]. | Additional parameters for uptake kinetics and dynamics. |

The Emergence and Validation of Consensus Modeling

Different automated GEM reconstruction tools can generate models with varying properties and predictive capabilities for the same organism [28]. Consensus modeling addresses this uncertainty by synthesizing the strengths of multiple individual models.

The GEMsembler Framework

GEMsembler is a dedicated Python package that systematically compares GEMs from different reconstruction tools, tracks the origin of model features, and builds consensus models containing a unified subset of reactions and pathways [28].

- Performance Validation: In rigorous tests, GEMsembler-curated consensus models for Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Escherichia coli outperformed gold-standard, manually curated models in predicting auxotrophy (nutrient requirements) and gene essentiality [28].

- Uncertainty Reduction: By highlighting discrepant pathways and GPR rules across input models, GEMsembler pinpoints areas of metabolic uncertainty, guiding targeted experimental validation to resolve model conflicts [28].

- Mechanistic Workflow: The tool provides an agreement-based curation workflow where reactions are included in the consensus model based on their presence in a user-defined subset of the input models (e.g., a reaction must appear in at least two of three input models) [28].

GEMsembler Consensus Model Workflow

Experimental Protocols for GEM Validation and Integration

The predictive power of GEMs and consensus models is critically dependent on integration with experimental data. The following protocols outline standard methodologies for validating and contextualizing models.

Protocol 1: Integrating Multi-Omics Data for Condition-Specific Modeling

This protocol, adapted from integration studies with Pseudomonas veronii, generates context-specific GEMs by incorporating transcriptomics and exometabolomics data [32].

- Cultivation and Sampling: Grow the target organism under defined conditions of interest (e.g., exponential vs. stationary phase). Collect cell pellets and spent medium samples at specific time points [32].

- Omics Data Generation:

- RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq): Extract total RNA, prepare cDNA libraries, and perform deep sequencing. Map reads to the reference genome to quantify genome-wide gene expression [32].

- Exometabolomics: Use high-resolution mass spectrometry (e.g., LC-MS/MS) to perform untargeted analysis of the spent medium, identifying and quantifying extracellular metabolites [32].

- Data Integration via REMI: Utilize the Relative Expression and Metabolomics Integration (REMI) tool. REMI integrates differential gene expression and metabolite abundance data into a base GEM to maximize consistency between the data and predicted metabolic fluxes for a given condition pair [32].

- Model Simulation and Validation: Simulate the resulting context-specific model (e.g., using FBA) to predict growth rates or metabolic secretion profiles. Compare these predictions against measured experimental values (e.g., optical density, enzymatic assays) to validate model accuracy [32].

Protocol 2: Comparing Metabolic States with ComMet

The ComMet approach enables a model-driven comparison of metabolic states in large GEMs, such as healthy versus diseased, without relying on assumed objective functions [29].

- Define Constraints: Apply condition-specific constraints (e.g., different nutrient availability) to the GEM to create distinct in silico representations of the metabolic states to be compared [29].

- Flux Space Characterization: Use an analytical approximation algorithm to efficiently estimate the probability distribution of reaction fluxes for each condition, avoiding the computational cost of traditional sampling in large models [29].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Perform PCA on the characterized flux spaces to decompose them into biochemically interpretable reaction sets, or "modules," that account for the majority of flux variability [29].

- Extract Differential Features: Identify the metabolic modules and specific reactions whose flux potentials most significantly differ between the two conditions. These form the hypothesized mechanistic basis for the phenotypic difference [29].

- Visualization and Hypothesis Generation: Map the differentially active modules onto the metabolic network. This visualization helps generate testable hypotheses about the underlying metabolic reprogramming, which can be validated experimentally [29].

ComMet Metabolic State Comparison Workflow

Advanced Applications: From Single Organisms to Microbial Communities

GEMs are increasingly scaled to model complex ecological interactions, providing mechanistic insights into community structure and function.

Modeling Host-Microbe Interactions

GEMs offer a powerful framework to investigate host-microbe interactions at a systems level [33] [30]. Multi-compartment models, which combine a host GEM (e.g., human or plant) with GEMs of associated microbial species, can simulate metabolic cross-feeding, predict the impact of microbiota on host metabolism, and identify potential therapeutic targets by simulating the effect of dietary or pharmacological interventions [33] [31] [30].

Designing and Deciphering Microbial Communities

Community-level GEMs are used to predict the emergent properties of microbial consortia, such as syntrophy (cross-feeding), competition, and community stability [34]. These models help elucidate the metabolic principles governing community assembly and can be used to design synthetic microbial consortia with desired functions for biotechnology, agriculture, and medicine [34]. The main challenge lies in formulating realistic community-level objectives and accurately simulating the dynamic exchange of metabolites [31].

Table 2: Applications of GEMs Across Biological Scales

| Application Scale | Modeling Approach | Key Insight Generated | Representative Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Strain / Multi-Strain | Pan-genome analysis to create core and pan metabolic models from multiple individual GEMs [27]. | Identification of strain-specific metabolic capabilities and vulnerabilities [27]. | Analysis of 410 Salmonella strain GEMs to predict growth in 530 environments [27]. |

| Host-Microbe Interactions | Integrated multi-compartment GEMs simulating metabolite exchange between host and microbiome [33] [30]. | Prediction of reciprocal metabolic influences, such as microbiome-derived metabolites affecting host pathways [33] [30]. | Understanding the role of the gut microbiome in host metabolic disorders and immune function [33]. |

| Microbial Communities | Dynamic Multi-Species GEMs using techniques like dFBA to simulate population and metabolite changes over time [31] [34]. | Prediction of stable consortium compositions, community metabolic output, and response to perturbations [31] [34]. | Designing consortia for bioremediation of pollutants or enhanced production of biofuels [34]. |

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Advanced Metabolic Modeling

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEMsembler [28] | Python Package | Consensus model assembly and structural comparison from multiple input GEMs. | Improves model accuracy and reliability for phenotype prediction; identifies areas of metabolic uncertainty. |

| REMI [32] | Algorithm/Tool | Integration of relative gene expression and metabolomics data into GEMs. | Generates condition-specific models that reflect metabolic reprogramming, enabling mechanistic study of adaptation. |

| ComMet [29] | Methodological Framework | Comparison of metabolic states in large GEMs without assumed objective functions. | Identifies differential metabolic features between states (e.g., healthy vs. diseased) for hypothesis generation. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Mathematical Technique | Prediction of steady-state metabolic fluxes to optimize a biological objective [27]. | Core simulation method for predicting growth, nutrient utilization, and metabolic phenotype from a network structure. |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry | Analytical Instrument | Untargeted profiling of intracellular and extracellular metabolites (metabolomics) [32] [35]. | Provides quantitative experimental data on metabolic outcomes for model input, constraint, and validation. |

| RNA Sequencing | Experimental Method | Genome-wide quantification of gene expression (transcriptomics) [32]. | Informs context-specific model construction by indicating which metabolic genes are active under studied conditions. |

Genome-scale metabolic models provide an unparalleled, mechanistic framework for interpreting complex biological data and predicting phenotypic outcomes. The emergence of consensus approaches like GEMsembler marks a significant advancement, directly addressing model uncertainty and enhancing predictive trustworthiness. When integrated with multi-omics data through standardized experimental protocols, GEMs transition from static reconstructions to dynamic, context-specific models capable of revealing the fundamental mechanics of life from single cells to complex microbial ecosystems. This powerful synergy between computation and experimentation is indispensable for validating microbial interaction networks and driving discoveries in drug development and systems biology.

The intricate web of microbial interactions forms a complex system that is fundamental to the health and function of diverse ecosystems, from the human gut to the plant rhizosphere. Understanding this "microbial interactome" – the system-level map of microbe-microbe, microbe-host, and microbe-environment interactions – is a central challenge in modern microbiology [2]. The characterization of these interaction networks is pivotal for advancing our understanding of the microbiome's role in human health, guiding the optimization of therapeutic strategies for managing microbiome-associated diseases [2]. Within these networks, certain species exert a disproportionately large influence on community structure and stability; these are the keystone species. Their identification, along with the functional modules they orchestrate, is critical for validating microbial interaction networks and translating ecological insights into actionable knowledge, particularly in drug development and therapeutic intervention.

Theoretical Framework: Keystone Species and Network Analysis

Defining Keystone Species in Microbial Networks

In microbial ecology, a keystone species is an operational taxonomic unit (OTU) whose impact on its community is disproportionately large relative to its abundance. Recent research has revealed that microbial generalists—species capable of thriving across multiple environmental niches or host compartments—often function as keystone species [36] [37]. For instance, in the anthosphere (floral microbiome), bacterial generalists like Caulobacter and Sphingomonas and fungal generalists like Epicoccum and Cladosporium were found to be tightly coupled in the network and constructed core modules, suggesting they act as keystone species to support and connect the entire microbial community [36].

A Network Theory Approach to Microbial Ecology

Network theory provides a powerful mathematical framework for representing and analyzing these complex ecological relationships [2]. In a microbial interaction network:

- Nodes represent microbial species or OTUs.

- Edges represent the functional interactions between them [2].

These interactions can be characterized by their ecological effect:

- Sign: Positive (+), negative (–), or neutral (0).

- Strength/Magnitude: The weight of the interaction.

- Direction: Whether the relationship is directed (A→B) or undirected (A–B) [2].

Table: Classifying Ecological Interactions in Microbial Networks

| Interaction Type | Effect of A on B | Effect of B on A | Network Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | + | + | Undirected, positive edge |

| Competition | – | – | Undirected, negative edge |

| Commensalism | + | 0 | Directed edge |

| Amensalism | – | 0 | Directed edge |

| Parasitism/Predation | + | – | Directed edge |

A functional module is a group of densely connected nodes that often work together to perform a specific ecological function. Keystone species frequently serve as hubs (highly connected nodes) or connectors (nodes that link different modules), thereby determining overall network stability [37].

Methodological Approaches: Statistical and Experimental Frameworks

The accurate detection of microbial interactions depends heavily on experimental design and the choice of statistical tools, each with inherent strengths and limitations.

Comparison of Network Inference Methods

Table: Methodological Approaches for Microbial Network Inference

| Method Category | Key Feature | Required Data Type | Inference Capability | Notable Tools/Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Sectional | Static "snapshots" of multiple communities | Relative abundance data from multiple samples | Undirected networks (association, not causation) | Correlation-based methods (SparCC, SPIEC-EASI) |

| Longitudinal | Repeated measurements over time | Time-series data from one or more individuals | Directed networks (potential causality) | Dynamic Bayesian networks, Granger causality |

| Multi-Omic Integration | Combines multiple data layers (e.g., genomic, metabolomic) | Metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, metabolomic data | Mechanistic insights into interactions | PICRUSt2, FAPROTAX, FUNGuild [36] |

Cross-sectional studies can reveal undirected associations but are susceptible to false positives from compositional data and environmental confounding. Longitudinal time-series data are essential for inferring directed interactions and causal relationships, as they capture the dynamic response of microbes to each other and to perturbations [2]. The integration of multi-omic data helps move beyond correlation to propose potential molecular mechanisms underlying observed interactions.

Foundational Experimental Protocols

The following workflow, generalized from recent studies on plant microbiomes [36] [37], outlines a standard protocol for building microbial interaction networks from amplicon sequencing data.

Case Studies in Validation

The Anthosphere Microbiome

A 2025 study of 144 flower samples from 12 wild plant species provides a robust example of network validation [36]. The research demonstrated that the anthosphere microbiome is plant-dependent, yet microbial generalists (Caulobacter, Sphingomonas, Achromobacter, Epicoccum, Cladosporium, and Alternaria) were consistently present across species. Ecological network analysis revealed these generalists were tightly coupled and formed the core network modules in the anthosphere. The study also linked community structure to function, predicting an enrichment of parasitic and pathogenic functions in specific plants like Capsella bursa-pastoris and Brassica juncea using functional prediction tools [36]. This validates the network by connecting topological properties (the core module) to both taxonomic consistency (the generalists) and a potential ecological outcome (pathogen prevalence).

The Feral Rapeseed Rhizosphere