Validating Ancestral State Reconstruction in Gene Regulatory Network Evolution: Methods, Challenges, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating ancestral state reconstruction (ASR) in gene regulatory network (GRN) evolution, addressing a critical need in evolutionary developmental biology and systems biology.

Validating Ancestral State Reconstruction in Gene Regulatory Network Evolution: Methods, Challenges, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating ancestral state reconstruction (ASR) in gene regulatory network (GRN) evolution, addressing a critical need in evolutionary developmental biology and systems biology. We explore the foundational principles of ASR, from its historical roots in cladistics to modern model-based approaches, and detail cutting-edge methodological applications that infer ancestral GRN states. The article systematically addresses key troubleshooting challenges and optimization strategies, including accounting for evolutionary rate variation and statistical uncertainty. Furthermore, we present a multi-faceted validation framework combining computational benchmarks, phylogenetic predictions, and crucially, experimental biochemical testing—exemplified by studies on kinase evolution. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this synthesis empowers the confident application of ASR to decipher the evolutionary history of regulatory networks, with significant implications for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets.

The Foundations of Ancestral State Reconstruction: Tracing the Evolutionary Blueprint of Gene Networks

Defining Ancestral State Reconstruction (ASR) and Its Core Principles

Ancestral State Reconstruction (ASR) is a computational method in evolutionary biology that extrapolates back in time from measured characteristics of contemporary individuals, populations, or species to infer the characteristics of their common ancestors [1] [2]. It is a fundamental application of phylogenetics, allowing scientists to test hypotheses about evolutionary history, trace the origin of key traits, and understand the genetic basis of evolutionary changes in regulatory networks [1] [3].

The core principle of ASR is the application of an evolutionary model to a phylogenetic tree (a hypothesis of evolutionary relationships) to estimate the states of characteristics—whether genetic sequences, phenotypic traits, or geographic distributions—at internal nodes representing ancestors [1] [2]. The accuracy of ASR is contingent on the realism of the underlying evolutionary model and the accuracy of the phylogenetic tree itself [1] [2].

Methodological Framework of ASR

ASR methodologies have evolved from simple heuristics to complex statistical models. The three primary classes of methods are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Core Methodologies for Ancestral State Reconstruction

| Method | Core Principle | Key Assumptions | Output | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Parsimony [1] [2] | Selects the evolutionary pathway that requires the fewest character state changes [1]. | Evolutionary change is rare; all types of changes are equally likely; all lineages evolve at the same rate [1]. | A single most-parsimonious reconstruction. | Sensitive to rapid evolution; ignores branch length; can be statistically unjustified [1] [2]. |

| Maximum Likelihood (ML) [2] | Finds the ancestral states that maximize the probability of observing the extant data, given a specific model of evolution and the phylogeny [2]. | Evolution follows an explicit, probabilistic model (e.g., a Markov process); accounts for branch lengths [2]. | The most likely ancestral state(s), often with associated probabilities. | Computationally intensive; results are conditional on the model of evolution and a single tree [2]. |

| Bayesian Inference [1] | Estimates the posterior probability distribution of ancestral states by integrating over uncertainty in the phylogeny and model parameters [1]. | Incorporates prior knowledge; accounts for uncertainty in the tree topology and evolutionary parameters [1]. | A sample of plausible ancestral states with quantified uncertainty. | Extremely computationally intensive [1]. |

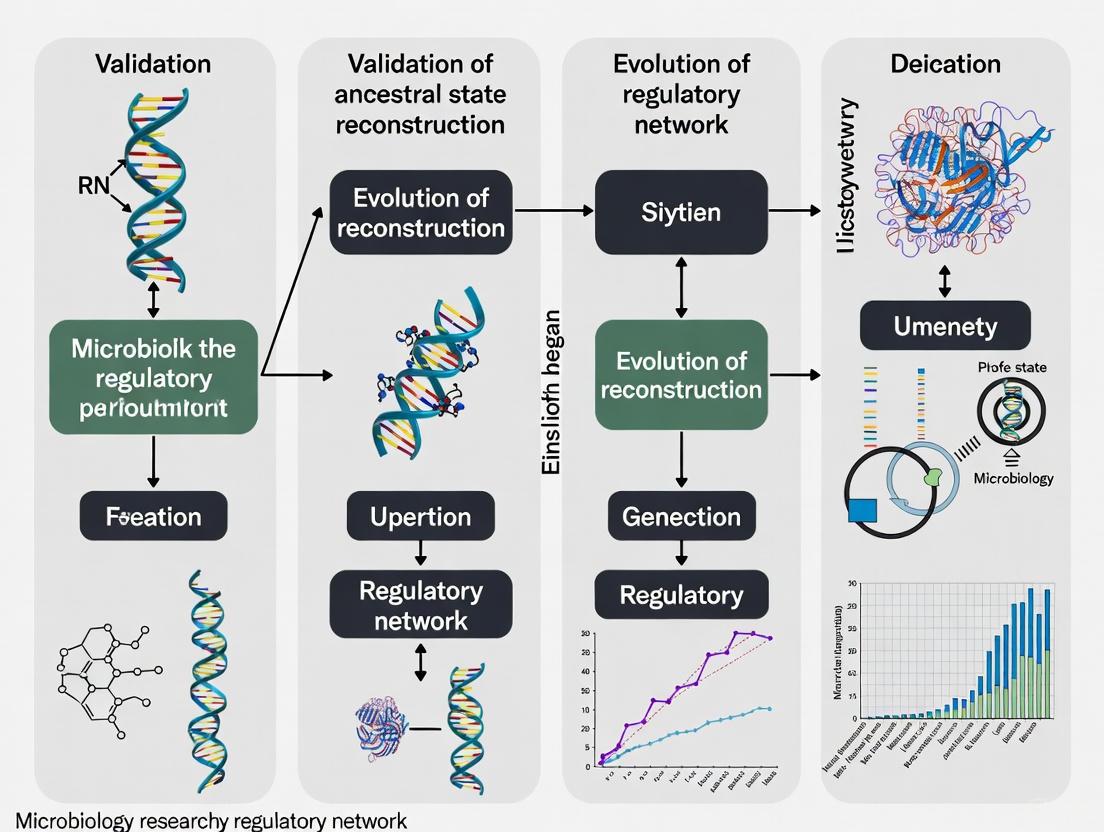

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for conducting an ASR analysis, from data collection to the inference of ancestral states.

Experimental Validation in Regulatory Network Evolution

ASR moves beyond inference to testable predictions when integrated with experimental molecular biology. A prime example is the study of kinase regulation, where researchers reconstructed ancestral protein sequences to understand how tight control of ERK1 and ERK2 kinases evolved [3].

Experimental Protocol: Ancestral Kinase Reconstruction

The following workflow and detailed protocol outline the key steps for an experimental ASR study, as demonstrated in ERK kinase research [3].

Detailed Methodology [3]:

- Sequence Alignment and Phylogeny Construction: A diverse set of modern CMGC kinase family sequences was collected and aligned. A maximum likelihood phylogeny was inferred to establish evolutionary relationships.

- Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction: Using the phylogeny and an evolutionary model, the amino acid sequences of key ancestral nodes were statistically inferred. This included ancestors such as AncMAPK (ancestor of all MAP kinases) and AncERK1-2 (ancestor of ERK1 and ERK2). Computational checks (posterior probabilities) were used to quantify confidence in the reconstructions.

- Gene Synthesis and Protein Purification: The DNA sequences coding for the inferred ancestral proteins were synthesized, cloned into expression vectors, and the proteins were purified from E. coli.

- Biochemical Assays:

- Specificity Profiling: A positional scanning peptide library (PSPL) was used to determine the substrate specificity of the ancestral kinases.

- Activity Assays: Basal catalytic activity was measured using a generic substrate (e.g., Myelin Basic Protein) to test for autophosphorylation capability without upstream activators.

- Functional Validation via Mutagenesis: Based on differences between active ancestors and inactive modern ERK, specific amino acid changes were identified. These "historical" mutations were engineered into modern ERK1/2, and the mutant proteins were tested for regained autophosphorylation activity. Furthermore, the ability of these autoactive mutants to drive signaling in human cells independently of their upstream activator MEK was tested.

Key Findings and Comparative Data

The experimental ASR of ERK kinases yielded quantitative data on the evolution of regulatory control, summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Ancestral Kinase Reconstruction [3]

| Kinase Construct | Key Functional Characteristic | Autophosphorylation & Basal Activity | Dependence on Upstream Activator (MEK) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancestral Kinases (e.g., AncERK1-5) | High basal catalytic activity [3]. | High | Low / Independent |

| Modern ERK1 & ERK2 | Tightly regulated, very low autoactivity [3]. | Very Low | Absolute Dependence |

| Modern ERK with Reverted Ancestral Mutations | regained autoactivation capability [3]. | High | Independent (in cells) |

This study identified two synergistic amino acid changes—a shortening of the β3-αC loop and a mutation of the gatekeeper residue—as pivotal in the evolutionary transition to tight MEK dependence. Reversing these changes in modern ERK was sufficient to create a constitutively active kinase, demonstrating how ASR can pinpoint the precise genetic mechanisms behind the evolution of complex regulatory networks [3].

Research Reagent Solutions for ASR Studies

Successful ASR research, particularly when coupled with experimental validation, relies on a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for ASR

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in ASR Workflow |

|---|---|

| Algorithm for Gene Order Reconstruction in Ancestors (AGORA) [4] | A parsimony-based algorithm for reconstructing ancestral gene contents and organizations (ancestral genomes) from extant genome data. |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Software (e.g., for Maximum Likelihood) | Infers the phylogenetic tree from sequence data, which is the essential foundation for all subsequent ASR [1] [2]. |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction Tools | Implements probabilistic models (ML, Bayesian) to infer ancestral character states on the nodes of a given phylogenetic tree [2]. |

| Gene Synthesis Services | Physically creates the DNA sequences of inferred ancestral genes for downstream experimental testing [3]. |

| Positional Scanning Peptide Library (PSPL) [3] | An experimental tool to determine the substrate specificity profile of reconstructed ancestral kinases. |

| Inducible Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [5] | A cellular model system used to test the functional impact of ancestral regulators or miRNA losses in a relevant developmental context. |

Ancestral State Reconstruction is a powerful comparative framework for deducing evolutionary history. Its core principles—applying explicit models of evolution to phylogenetic trees—allow researchers to move from static observations of extant species to dynamic hypotheses about historical processes. As demonstrated by its application to kinase regulation, ASR's true power is unlocked when computational inferences are paired with robust experimental validation. This integrated approach can precisely identify the genetic changes that drove the evolution of critical regulatory networks, with profound implications for understanding basic biology and disease mechanisms.

The field of evolutionary biology has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from the qualitative analysis of morphological characteristics to sophisticated computational methods that quantify evolutionary relationships from molecular data. This journey from traditional cladistics to computational phylogenetics represents a paradigm shift in how researchers infer evolutionary histories, particularly for challenging problems like ancestral state reconstruction in regulatory network evolution. Cladistics, emerging in the mid-20th century, provided the foundational principle that organisms should be grouped based on shared derived characteristics inherited from a common ancestor [6]. This methodology established the crucial concept of the clade—a group consisting of a common ancestor and all its descendants—which remains central to modern phylogenetic analysis [7].

The limitations of analyzing complex evolutionary scenarios with manual methods became increasingly apparent as biological data grew in volume and complexity. The development of powerful computers and sophisticated algorithms catalyzed the rise of computational phylogenetics, which applies statistical models and computational optimization to infer evolutionary trees from genetic sequence data [8]. This transition has been particularly critical for ancestral reconstruction in gene regulatory networks, where researchers attempt to extrapolate back in time from measured characteristics of individuals to their common ancestors [2]. The validation of these reconstructions requires increasingly sophisticated methods that account for the complex nature of molecular evolution, selection pressures, and non-neutral traits [9].

Fundamental Principles: From Cladistics to Computational Methods

The Cladistic Framework

Cladistics operates on the principle of parsimony, which seeks to minimize the total number of evolutionary changes required to explain the observed distribution of characteristics among taxa [6]. In a typical cladistic analysis, researchers begin by gathering data on the characteristics of the organisms being studied and constructing a character matrix that records the state of each characteristic for each taxon [7]. The method then identifies the most likely branching pattern by determining which characteristics are shared by different groups due to inheritance from a common ancestor rather than convergent evolution [6].

A simple example analyzing three dinosaur genera—Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus, and Camarasaurus—illustrates this process well. By coding characteristics such as "cervical ribs extend past at least one whole vertebra" or "bifurcated neural spine in cervical vertebrae" as present or absent, researchers can generate a character matrix [6]. The principle of parsimony then guides the selection of the tree topology that requires the fewest total character state transitions across the tree. In this dinosaur example, tree #1 required only 5 state transitions compared to 6 or 7 for alternative trees, making it the most parsimonious and thus preferred hypothesis [6].

The Computational Phylogenetics Revolution

Computational phylogenetics expanded this framework by introducing model-based inference and leveraging molecular sequence data. Where cladistics primarily used morphological characters, computational phylogenetics analyzes nucleotide or amino acid sequences, employing optimality criteria such as maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference to find phylogenetic trees that best explain the observed sequence data [8]. This shift enabled researchers to move beyond simple parsimony counts to sophisticated statistical models that account for variation in evolutionary rates across sites and lineages [8] [2].

The computational burden of these methods is substantial—while three taxa give rise to only three possible trees, ten taxa can be arranged into more than 34 million trees [6]. This combinatorial explosion necessitated the development of specialized software packages like PAUP (Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony) and MacClade, along with heuristic search algorithms that efficiently navigate "tree space" to find optimal solutions without exhaustively evaluating every possibility [6]. Key advances included distance-matrix methods like Neighbor-Joining, which cluster sequences based on genetic distance, and model-based approaches that explicitly account for different substitution patterns between nucleotides or amino acids [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Phylogenetic Analysis Methods

| Feature | Cladistics | Computational Phylogenetics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Principle | Parsony (minimize state changes) [6] | Maximum Likelihood, Bayesian Inference [8] |

| Data Sources | Morphological characteristics [6] | Molecular sequences (DNA, RNA, proteins) [8] |

| Character Treatment | Discrete states (e.g., present/absent) [6] | Continuous-time Markov models of state transition [8] [2] |

| Handling Uncertainty | Limited, primarily through character selection [6] | Statistical support measures (bootstrapping, posterior probabilities) [8] |

| Computational Demand | Low to moderate (hand calculation possible for small datasets) [6] | High (requires specialized software and often supercomputing resources) [8] |

| Key Limitations | Sensitive to convergent evolution; assumes changes are rare [6] [7] | Model misspecification; computational constraints with large datasets [8] [9] |

Ancestral State Reconstruction: Methods and Validation Challenges

Reconstruction Methods

Ancestral reconstruction represents a critical application of phylogenetics, enabling researchers to infer the characteristics of ancestral populations or species from contemporary observations [2]. The field has developed three primary approaches for this task:

Maximum Parsimony, one of the earliest formalized algorithms, seeks to find the distribution of ancestral states within a given tree that minimizes the total number of character state changes necessary to explain the states observed at the tips [2]. Implemented through algorithms like Fitch's method, it operates via two traversals of a rooted binary tree—first from tips toward root (postorder), then from root toward tips (preorder) [2]. While intuitively appealing and computationally efficient, parsimony methods suffer from several limitations: they assume changes between all character states are equally likely, perform poorly under rapid evolution, and do not account for variation in evolutionary time among lineages [2].

Maximum Likelihood (ML) methods treat character states at internal nodes as parameters and attempt to find values that maximize the probability of the observed data given a model of evolution and a phylogeny [2]. These approaches employ a probabilistic framework, typically modeling sequence evolution as a time-reversible continuous-time Markov process. The likelihood of a phylogeny is computed from a nested sum of transition probabilities corresponding to the tree's hierarchical structure, summing over all possible ancestral character states at each node [2]. ML methods naturally incorporate variation in evolutionary rates across sites and branches, providing more reliable estimates when evolutionary rates vary.

Bayesian methods extend the ML approach by accounting for uncertainty in tree reconstruction, evaluating ancestral reconstructions over many trees rather than relying on a single point estimate [2]. This approach is particularly valuable when multiple tree topologies have similar support, as it incorporates this uncertainty into the ancestral state estimates. Bayesian methods also allow for the incorporation of prior knowledge about evolutionary processes through explicit prior distributions on model parameters.

Validation Challenges for Non-Neutral Traits

Validating ancestral state reconstructions presents particular challenges for non-neutral traits under selection, such as those involved in gene regulatory networks [9]. The assumptions underpinning most ancestral state reconstruction methods are frequently violated in such systems, especially for traits under directional selection. Simulation studies reveal that error rates in ancestral reconstruction increase with node depth, the true number of state transitions, and rates of state transition and extinction, exceeding 30% for the deepest 10% of nodes under high rates of extinction and character-state transition [9].

The performance of different methods varies significantly under non-neutral conditions. BiSSE (Binary State Speciation and Extinction) models, which simultaneously model trait evolution and lineage diversification, generally outperform both parsimony and standard Markov (Mk2) models when either speciation or extinction is state-dependent [9]. However, all methods struggle with scenarios involving preferential extinction of species with the ancestral character state or highly asymmetrical transition rates away from the ancestral state [9]. These findings have profound implications for reconstructing the evolution of regulatory networks, where transcription factor binding sites or regulatory motifs may experience precisely such selective pressures.

Table 2: Accuracy of Ancestral State Reconstruction Methods Under Non-Neutral Conditions

| Condition | Maximum Parsimony | Mk2 Model | BiSSE Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetric Rates | Moderate accuracy [9] | High accuracy [9] | High accuracy [9] |

| Asymmetric Transition Rates | Performance decreases significantly [9] | Moderate accuracy [9] | High accuracy [9] |

| State-Dependent Speciation | Low accuracy [9] | Low accuracy [9] | High accuracy [9] |

| State-Dependent Extinction | Low accuracy [9] | Low accuracy [9] | High accuracy [9] |

| Deep Nodes (>90% of tree depth) | Error rates >30% [9] | Error rates >30% [9] | Error rates >30% but lower than alternatives [9] |

| Root State Inference | Highly inaccurate under high transition rates [9] | Moderate accuracy [9] | High accuracy except under extreme parameters [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Simulation-Based Validation

Rigorous validation of ancestral state reconstruction methods requires carefully designed simulation studies that benchmark performance against known evolutionary histories. The following protocol, adapted from seminal work in the field [9], provides a framework for such validation experiments:

Tree and Character Simulation: Employ state-dependent speciation and extinction models (e.g., BiSSE) to simultaneously simulate phylogenetic trees and binary characters. This approach generates more realistic evolutionary scenarios than independent simulation of trees and traits. Parameters should include state-dependent speciation rates (λ₀, λâ‚), extinction rates (μ₀, μâ‚), and character transition rates (qâ‚€â‚, qâ‚â‚€), with the root state fixed to a known value (typically 0) to enable accuracy assessment [9].

Parameter Space Exploration: Systematically vary parameters across biologically realistic ranges. Extinction rates should span {0.01, 0.25, 0.5, 0.8}, character transition rates {0.01, 0.05, 0.1}, and speciation rate pairs should include both symmetrical and asymmetrical values [9]. This comprehensive parameter sampling ensures conclusions hold across diverse evolutionary scenarios.

Reconstruction and Comparison: Apply target reconstruction methods (parsimony, Mk2, BiSSE) to the simulated data, then compare inferred ancestral states to the known true states from simulations. Accuracy should be assessed both overall and as a function of node depth, as error rates typically increase toward deeper nodes [9].

Error Quantification: Calculate error rates for each method-condition combination, with particular attention to scenarios involving asymmetrical transition rates, state-dependent diversification, and deep nodes. Statistical tests should determine whether performance differences between methods are significant [9].

This protocol directly addresses the challenges of validating reconstruction methods for non-neutral traits by explicitly incorporating state-dependent speciation and extinction into the simulation process, thus creating more biologically realistic benchmark datasets.

Gene Regulatory Network Validation

For studies focused specifically on regulatory network evolution, a specialized validation protocol connects phylogenetic reconstruction with network dynamics:

Network Definition: Establish a gene regulatory network (GRN) structure based on established biological knowledge. For example, studies of Arabidopsis thaliana flower morphogenesis might define a 12-gene network with documented activation/inhibition relationships [10].

Dynamical Model Construction: Convert discrete network models (e.g., Boolean networks) to continuous dynamical systems describing temporal evolution of protein concentrations. This typically involves creating ordinary differential equations for mRNA and protein concentrations for each network node [10].

Epigenetic Landscape Computation: Solve the associated Fokker-Planck equation to obtain a stationary probability distribution of concentrations, representing the epigenetic landscape. Advanced computational methods like gamma mixture models can transform this problem into an optimization framework [10].

Experimental Correlation: Compare theoretical coexpression patterns derived from the epigenetic landscape with empirical coexpression matrices from experimental data. Strong agreement validates both the network model and the evolutionary inferences derived from it [10].

This approach provides a powerful bridge between phylogenetic reconstruction of ancestral states and their functional validation in terms of regulatory dynamics and network stability.

Diagram 1: Simulation Validation Workflow (Width: 760px)

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Phylogenetic Validation

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAUP | Software Package | Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony and other optimality criteria [6] | General phylogenetic inference; particularly effective for parsimony-based analyses [6] |

| MacClade | Software Package | Interactive analysis of phylogeny and character evolution [6] | Examining evolutionary hypotheses and character state changes across trees [6] |

| diversitree R package | Software Library | Analysis of comparative phylogenetic data; implements BiSSE and related models [9] | Testing for state-dependent diversification; ancestral reconstruction under non-neutral evolution [9] |

| iPhyloC | Web Framework | Interactive comparison of phylogenetic trees with non-identical taxa [11] | Comparing gene trees and species trees; visualizing phylogenetic incongruence [11] |

| BiSSE Model | Analytical Model | Simultaneous modeling of trait evolution and lineage diversification [9] | Ancestral reconstruction when traits influence speciation/extinction rates [9] |

| 16S rRNA Sequences | Molecular Markers | Taxonomic profiling of microbial communities [12] | Phylogenetic analysis of microbial diversity; marker gene-based approaches [12] |

| Whole-Genome Shotgun Data | Genomic Data | Comprehensive genomic sampling without cultivation [12] | Phylogenomic studies; reconstruction of draft genomes from environmental samples [12] |

Applications in Regulatory Network Evolution and Drug Discovery

Phylogenetic Analysis of Gene Regulatory Networks

The evolution of gene regulatory networks represents a particularly challenging application for phylogenetic methods due to the complex interactions between transcription factors, regulatory elements, and their target genes. Phylogenetic approaches help unravel how these networks evolve by identifying conserved regulatory modules and lineage-specific innovations [12]. By comparing orthologous genes across species and reconstructing their ancestral states, researchers can infer how regulatory relationships have changed over evolutionary time [12].

The integration of phylogenetic methods with gene expression data enables the reconstruction of ancestral expression states, providing insights into how regulatory programs have evolved. This approach has revealed both deep conservation of certain regulatory circuits and surprising flexibility in others [12]. For example, studies of flower development in Arabidopsis thaliana have combined phylogenetic analysis with dynamical modeling of its 12-gene regulatory network, enabling researchers to understand how alterations in network architecture produce different floral morphologies [10]. This integration of phylogenetics with dynamical systems theory represents a powerful frontier in evolutionary developmental biology.

Pharmaceutical Applications

Phylogenetic methods have found important applications in drug discovery and development, particularly in the identification of potential drug targets and prediction of drug resistance mechanisms [12]. By analyzing the evolutionary relationships between pathogen strains, researchers can identify conserved essential genes that represent promising targets for novel antimicrobial agents [12]. Similarly, phylogenetic profiling—comparing the presence or absence of orthologous genes across species—can reveal co-evolving gene sets and predict functional associations in metabolic pathways that might be targeted therapeutically [12].

In molecular epidemiology, phylogenetic approaches track the origin and spread of pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2, investigate disease outbreaks, and develop targeted interventions [12]. These applications rely on the ability to reconstruct ancestral states of pathogens, identifying key mutations that alter transmissibility, virulence, or drug resistance. The accuracy of these reconstructions has direct implications for public health responses, as misinterpretations could lead to ineffective containment strategies or therapeutic approaches [12] [9].

Diagram 2: Phylogenetic Analysis Applications (Width: 760px)

The historical trajectory from cladistics to computational phylogenetics has profoundly expanded our ability to reconstruct evolutionary history, particularly for complex systems like gene regulatory networks. While cladistics established the fundamental conceptual framework of monophyletic grouping based on shared derived characteristics, computational methods have enabled statistically rigorous, model-based inference that accounts for the stochastic nature of molecular evolution [6] [8]. This evolution has been driven by both theoretical advances and exponential growth in computational power, allowing researchers to tackle problems of previously unimaginable scale and complexity.

Validation of ancestral state reconstructions remains challenging, particularly for non-neutral traits under selection [9]. Future progress will likely require continued development of integrated models that simultaneously account for trait evolution, lineage diversification, and environmental influences. The incorporation of additional data types—including epigenomic, proteomic, and metabolomic information—into phylogenetic frameworks promises to provide more comprehensive insights into evolutionary processes [12]. As these methods continue to mature, they will enhance our ability to not only reconstruct the evolutionary past but also predict future evolutionary trajectories, with important implications for medicine, conservation, and fundamental understanding of biological diversity.

The Centrality of the Phylogenetic Tree as an Evolutionary Hypothesis

The phylogenetic tree is more than a simple depiction of evolutionary relationships; it is a powerful, testable hypothesis about historical processes that can be validated and refined through statistical analysis. This central role is crucial in modern evolutionary biology, particularly in complex fields like regulatory network evolution. By providing a historical scaffold, phylogenetic trees allow researchers to move beyond mere description to hypothesis-driven investigation of evolutionary mechanisms. The practice of ancestral state reconstruction (ASR) transforms these trees into dynamic tools for inferring past characteristics, from morphological traits to molecular functions [13]. This is especially relevant for studying how gene regulatory networks have evolved, as it allows scientists to formulate and test specific hypotheses about the ancestral states of these networks and the evolutionary paths that led to their current diversity. The phylogenetic framework thereby bridges the gap between observed genomic data and inferred historical processes, offering a rigorous method for testing evolutionary hypotheses.

Comparative Analysis of Phylogenetic Methodologies

Various statistical methods have been developed to incorporate phylogenetic information into evolutionary studies. The table below summarizes the core features, strengths, and limitations of several key phylogenetic comparative methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Key Application in Evolutionary Hypothesis Testing | Data Requirements | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts (PIC) [14] | Transforms species data into statistically independent contrasts using an evolutionary model (e.g., Brownian motion). | Testing for adaptation and trait correlations while accounting for shared phylogenetic history. | Rooted tree with branch lengths; continuously distributed trait data. | Assumes a Brownian motion model of evolution; not suitable for multivariate predictions of ancestral states. |

| Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) [14] | A generalized least squares regression model where the variance-covariance matrix is defined by the phylogeny and an evolutionary model. | Modeling relationships between multiple traits, accounting for phylogenetic non-independence. | Rooted tree with branch lengths; continuous response and predictor variables. | More computationally intensive than PIC; model misspecification can lead to biased results. |

| Ancestral State Reconstruction (ASR) [13] | Uses statistical models to infer the character states (discrete or continuous) of ancestral nodes on a phylogeny. | Inferring the evolutionary history and timing of trait changes, testing hypotheses about ancestral states. | Rooted phylogeny; trait data for terminal taxa; model of character evolution. | Accuracy is highly dependent on the model of evolution and the completeness of the phylogeny. |

| Phylogenetically Informed Simulations [14] | Generates null distributions of test statistics by simulating trait evolution along the phylogenetic tree. | Creating phylogenetically correct null hypotheses for testing evolutionary patterns (e.g., trait correlations). | Rooted tree with branch lengths; model of trait evolution for simulations. | Requires careful specification of the evolutionary model used for simulations. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Ancestral Hypotheses

Genome-Wide InterEvo Analysis for Convergent Evolution

A groundbreaking 2025 study on animal terrestrialization provides a robust protocol for testing hypotheses about convergent genome evolution using phylogenetic trees [15]. The methodology can be adapted for research on regulatory networks.

- 1. Genomic Data Curation and Phylogeny Construction: The first step involves mining a large dataset of high-quality genomes (e.g., 154 genomes from 21 animal phyla). A strongly supported phylogenetic tree is then constructed, focusing on nodes that represent major evolutionary transitions (e.g., the 11 independent terrestrialization events in the cited study) [15].

- 2. Homology and Gene Turnover Analysis: Protein sequences from all genomes are clustered into Homology Groups (HGs) to identify orthologous and paralogous genes. The genomic content of key ancestral nodes is reconstructed, classifying HGs based on their evolutionary mode: gains (novel, novel core, expanded) and reductions (contracted, lost). Statistical tests (e.g., permutation tests) confirm whether observed gene turnover rates are significantly higher in lineages of interest compared to control nodes [15].

- 3. Functional Convergence Analysis: The functions of genes identified as gained or lost in independent lineages are annotated using Gene Ontology (GO) terms and protein domain databases (e.g., Pfam). Convergence is inferred by identifying biological functions (e.g., osmosis regulation, detoxification) that are significantly overrepresented in the novel genes of multiple, independently evolving lineages. The functions of terrestrial novel genes are further compared to those in aquatic ancestors to ensure they are distinct and not merely exaptations [15].

Ancestral State Reconstruction for Regulatory Networks

A study on silver birch (Betula pendula) exemplifies the protocol for inferring the ancestral state of regulatory networks [16], directly applicable to the user's thesis context.

- 1. Regulatory Network Construction: For the focal organism and related species, gene regulatory networks are constructed. This involves combined analyses such as co-expression analysis (using RNA-seq data) and in silico promoter motif analysis to identify transcription factors and their potential target genes [16].

- 2. Multi-Species Network Comparison and Phylogenetic Mapping: The structure and components of the regulatory networks (e.g., for secondary cell wall biosynthesis) are compared across multiple species. Key features—such as the presence of specific regulatory interactions, genes under positive selection, and genes retained from whole-genome multiplications—are mapped onto a established phylogenetic tree [16].

- 3. Inference of Ancestral Network State: Using ASR methods on the phylogenetic tree, the ancestral state of the regulatory network is inferred. In the birch example, this analysis suggested a "relatively simple ancestral state" for secondary cell wall regulation in core eudicots, which has been retained in birch. The evolution of specific network components, like lignin biosynthesis, can be identified as less conserved, highlighting points of evolutionary innovation [16].

Visualization and Annotation of Phylogenetic Data

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting complex phylogenetic hypotheses and their associated data. The ggtree package in R has become a powerful tool for this purpose, enabling researchers to create highly customizable and informative tree visualizations [17] [18].

ggtree supports a wide array of tree layouts, including rectangular, circular, fan, and unrooted (using equal-angle or daylight algorithms), allowing researchers to choose the most effective way to present their data and hypotheses [18]. Beyond basic topology, ggtree excels at integrating diverse types of associated data. It can directly use covariates stored in the tree object to color branches or nodes, allowing for the visualization of traits, evolutionary rates, or divergence times. Users can add multiple layers of annotations to highlight clades, label nodes with symbols or text, and display uncertainty in branch lengths [17] [18]. This flexibility makes it an indispensable tool for exploring tree structures and visually communicating the results of ancestral state reconstructions and other phylogenetic analyses.

Workflow for Phylogenetic Analysis and Ancestral State Reconstruction

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for using phylogenetic trees to test evolutionary hypotheses, from data collection to visualization.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogenetic Analysis

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Genome Assemblies (High-quality, across multiple species) | Serves as the primary data source for identifying genes, homology groups, and conducting phylogenetic tree construction [15]. |

| Software for Phylogenetic Inference (e.g., IQ-TREE, RAxML) | Used to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree topology and estimate branch lengths, forming the essential scaffold for all subsequent comparative analyses [15] [14]. |

| Homology Grouping Tools (e.g., OrthoFinder) | Clusters protein sequences into orthologous and paralogous groups, enabling the analysis of gene gain and loss across the phylogeny [15]. |

Comparative Method Software (e.g., phylolm R package) |

Implements statistical methods like PGLS and PIC to test trait correlations and evolutionary models while accounting for phylogenetic history [14]. |

Ancestral State Reconstruction Tools (e.g., ape, phytools R packages) |

Applies statistical models to infer the characteristics of ancestral nodes on the phylogeny, crucial for testing hypotheses about past states [13] [14]. |

Tree Visualization Software (e.g., ggtree R package) |

Enables the visualization, annotation, and publication-ready presentation of phylogenetic trees and their associated data [17] [18]. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) & Pfam Databases | Provides functional annotation for genes, allowing researchers to interpret genomic changes in a biological context (e.g., identifying convergent functions) [15]. |

The phylogenetic tree remains the central, indispensable hypothesis in evolutionary biology. Its power is not static but is continually enhanced by integrating robust statistical comparative methods like PGLS, sophisticated ancestral state reconstruction protocols, and advanced visualization tools. As demonstrated by genomic studies of convergent evolution and regulatory network analysis, this integrated framework allows researchers to rigorously test complex hypotheses about the deep past. By reconstructing ancestral states and visualizing evolutionary pathways, scientists can transform the tree from a static diagram into a dynamic model of history, providing profound insights into the mechanisms that have shaped the diversity of life on Earth.

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) are fundamental frameworks for understanding how coordinated gene expression programs control development and phenotypic traits [19]. The evolution of species-specific traits and novel biological structures is primarily driven by alterations in the structure and function of these networks [19] [20]. GRNs possess a hierarchical and modular architecture that profoundly influences their evolutionary trajectory [19] [21]. At the foundation of this hierarchy are kernels—highly conserved, inflexible subcircuits that specify essential developmental fields [19]. These are distinguished from more labile "plug-in" modules and "differentiation gene batteries" that control terminal cell-specific functions [19]. This architectural organization creates a framework where changes at different hierarchical levels have distinct evolutionary consequences: kernel alterations lead to profound, potentially pleiotropic effects, while modifications to terminal differentiation programs offer greater evolutionary flexibility [19].

Understanding GRN evolution requires examining three interconnected conceptual pillars: the conservative nature of GRN kernels, the dynamic process of regulatory rewiring, and the functional recruitment mechanism of evolutionary co-option. These concepts are not mutually exclusive but represent different facets of how regulatory information is organized, modified, and repurposed throughout evolution. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the experimental approaches and data types used to validate reconstructions of ancestral GRN states, with particular emphasis on their strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications within evolutionary developmental biology.

Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions

GRN Kernels: The Stable Core of Developmental Programs

GRN kernels represent deeply conserved subcircuits responsible for specifying the fundamental positional identities and developmental fields in an organism [19]. These network components are characterized by their evolutionary stability, functional criticality, and resistance to change due to the severe fitness consequences of their perturbation [19]. The hierarchical constraint of GRNs is inversely related to developmental potential, creating a system where kernels form the immutable foundation upon which evolutionary innovations are built [19].

Table: Characteristics of GRN Hierarchical Components

| Component Type | Evolutionary Flexibility | Functional Role | Impact of Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kernels | Low (Highly conserved) | Specify essential developmental fields | Large, often pleiotropic |

| Plug-in Modules | Intermediate | Carry out specific signaling processes | Context-dependent |

| Differentiation Gene Batteries | High (Labile) | Control cell type-specific functions | Limited, tissue-specific |

Regulatory Rewiring: Altering Network Connectivity

Regulatory rewiring encompasses changes in the connections between transcriptional regulators and their target genes, creating novel network architectures [22]. This process represents a key mechanism of evolutionary innovation, particularly through transcription factors gaining or losing regulatory connections to target genes [22]. In bacterial systems, successful rewiring events demonstrate that transcription factors with high activation capability, high expression levels, and preexisting low-level affinity for novel target genes are preferentially co-opted [22]. This suggests that the potential for evolutionary innovation is constrained by the existing GRN architecture and the biochemical properties of individual transcription factors [22].

Evolutionary Co-option: Repurposing Existing Genetic Programs

Co-option occurs when existing GRN subcircuits are redeployed in different developmental contexts or for new functional purposes [19] [23]. This process allows for the rapid evolution of novel traits without requiring the de novo evolution of complete genetic programs. A documented example includes the co-option of organic scaffold-forming networks for biomineralization in deuterostomes, where GRNs controlling distinct organic scaffolds were independently recruited for mineralization functions in different lineages [23]. The ease with which a subcircuit can be co-opted and its functional consequences are dependent on its position within the GRN hierarchy [19].

Methodological Comparison for Ancestral State Reconstruction

Validating reconstructions of ancestral GRN states requires integrating multiple computational and experimental approaches. The table below compares the primary methodologies employed in contemporary evolutionary developmental biology research.

Table: Methodological Approaches for Ancestral GRN Reconstruction

| Methodology | Core Principle | Data Requirements | Validation Strength | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-species Regulatory Network Learning (MRTLE) | Uses phylogenetic structure, sequence motifs, and transcriptomics to infer networks across species [24] | Gene expression data from multiple species, phylogenetic tree, orthology relationships [24] | High (incorporates evolutionary relationships explicitly) [24] | Computationally intensive; requires multiple sequenced genomes [24] |

| Cis-Regulatory Module (CRM) Analysis | Comparative analysis of non-coding regulatory sequences and their transcription factor binding sites [19] | Genome sequences, chromatin immunoprecipitation data, epigenetic marks [19] | Direct functional validation possible via reporter assays [19] | Labor-intensive; may miss long-range regulatory interactions [19] |

| Experimental Microbial Evolution | Direct observation of rewiring events in real-time under strong selection [22] | Genetically tractable model system, selectable phenotype [22] | Direct empirical observation of evolutionary trajectories [22] | Limited to microbial systems; may not reflect metazoan complexity [22] |

| Boolean Dynamical Modeling | Logical modeling of network states to identify stable attractors and phenotypic combinations [21] | Known regulatory interactions, perturbation responses [21] | Captures multistable switch behavior fundamental to cell fate decisions [21] | Oversimplifies quantitative kinetic parameters [21] |

Workflow Diagram: MRTLE Methodology for Phylogenetic Network Inference

The MRTLE approach represents a significant advancement in computational methods for GRN reconstruction across multiple species by explicitly incorporating phylogenetic relationships [24].

MRTLE Computational Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integrated inputs, processing steps, and outputs of the Multi-species Regulatory Network Learning method that explicitly incorporates phylogenetic information for more accurate ancestral GRN reconstruction [24].

Experimental Validation of Rewiring Events

Experimental validation of computationally predicted rewiring events requires direct manipulation in model systems. The diagram below illustrates a microbial experimental system used to identify properties that facilitate transcription factor rewiring.

Experimental Rewiring Identification: This workflow demonstrates the hierarchical discovery of transcription factor rewiring pathways in bacterial systems, revealing preferred and alternative evolutionary solutions to restore lost functions [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagents for GRN Evolution Studies

| Reagent/Solution Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | MRTLE [24], TEKRABber [25], Boolean modeling frameworks [21] | Network inference, cross-species comparison, dynamics simulation | Reconstruction of ancestral states, identification of conserved modules, prediction of evolutionary trajectories |

| Model Organisms | Drosophila species [19], Heliconius butterflies [19], Pseudomonas fluorescens [22], Ascomycete yeasts [24] | Comparative analysis, experimental evolution, functional validation | Provide evolutionary diversity, genetic tractability, and phenotypic variability for testing hypotheses |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Reporter constructs (e.g., lacZ, GFP) [19], CRISPR-Cas9 systems, RNA-seq libraries [24] | cis-regulatory analysis, gene editing, expression profiling | Functional testing of regulatory elements, genetic manipulation, transcriptome quantification |

| Phylogenetic Resources | Multi-species genome assemblies, orthology databases, sequence alignment tools | Ancestral state reconstruction, evolutionary rate calculation | Establishing evolutionary relationships, identifying conserved elements, tracing gene histories |

| Gancaonin J | Gancaonin J|Research Compound | Gancaonin J supplier for research. This prenylated chalcone is for research use only (RUO). Not for human consumption. Inquire for price and availability. | Bench Chemicals |

| Isooxoflaccidin | Isooxoflaccidin, MF:C16H12O5, MW:284.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Integrated Analysis: Synthesizing Evidence Across Methodologies

The most robust validation of ancestral GRN reconstructions comes from integrating multiple lines of evidence across computational and experimental approaches. The hierarchical structure of GRNs means that kernels exhibit greater sequence conservation and slower evolutionary rates compared to terminal differentiation genes [19] [20]. This creates a predictive framework where computational identification of deeply conserved non-coding elements can prioritize experimental targets for functional validation.

Studies in Drosophila pigmentation have demonstrated that seemingly similar phenotypic outcomes can arise through distinct molecular mechanisms—including cis-regulatory changes, trans-regulatory alterations, and combinations of both [19]. For example, the loss of male-specific abdominal pigmentation in Drosophila kikkawai resulted from changes in the Abd-B binding site within the yellow gene's 'body element' CRM, while similar phenotypic changes in other species involved trans-regulatory mechanisms [19]. This highlights the importance of experimental validation for distinguishing between convergent phenotypic evolution and true homologous regulatory mechanisms.

Boolean modeling of coupled regulatory switches in mammalian cell cycle regulation demonstrates how the coordinated activity of multistable circuits generates distinct phenotypic combinations [21]. This dynamical modularity perspective provides a conceptual bridge between GRN architecture and the emergent functional capabilities that evolution acts upon, revealing general principles that govern how coupled switches coordinate their functions across different biological contexts [21].

Validation of ancestral GRN reconstructions requires a multifaceted approach that leverages both computational predictions and experimental manipulations. The most compelling evidence emerges when phylogenetic inference, comparative genomics, and functional assays converge on consistent evolutionary scenarios. The hierarchical and modular organization of GRNs provides a theoretical foundation for predicting which network components are likely to be conserved versus those that are free to diverge, enabling more accurate reconstruction of ancestral states.

Future advances in this field will depend on developing increasingly sophisticated methods for integrating diverse data types—including single-cell transcriptomics, chromatin conformation, and epigenetic modifications—within a phylogenetic framework. This will enable researchers to move beyond static network maps toward dynamic models of regulatory evolution that capture the temporal, spatial, and functional constraints that shape the evolution of developmental programs. As these methods improve, so too will our ability to reconstruct the ancestral regulatory states that have generated the remarkable diversity of life forms observed today.

The Critical Relationship Between Model Realism and Reconstruction Accuracy

Ancestral state reconstruction (ASR) serves as a foundational tool in comparative biology, enabling researchers to infer the evolutionary history of lineages by extrapolating back in time from measured characteristics of contemporary species to their common ancestors [2]. In the specific context of regulatory network evolution research, the accuracy of these reconstructions is paramount, as they form the basis for understanding how complex cellular systems evolve and how molecular mechanisms diverge across species. The fidelity of such reconstructions critically depends on the biological realism of the underlying evolutionary models employed. Models that oversimplify the complex processes of evolution—ignoring factors such as state-dependent speciation, extinction, or character transition—introduce systematic biases that can compromise the validity of biological inferences [9]. This guide provides a comparative evaluation of ancestral reconstruction methodologies, focusing on how increasing model sophistication enhances accuracy, with particular emphasis on applications in regulatory network and protein function evolution.

Comparative Analysis of Reconstruction Methods

Ancestral reconstruction methods span a spectrum from simple parsimony-based approaches to complex model-based techniques that explicitly account for the evolutionary process. The choice of method is not trivial, as it directly impacts the reliability of the reconstructed ancestral states, which in turn affects downstream biological interpretations.

Core Methodologies and Algorithms

Maximum Parsimony (MP): This method operates on the principle of "Occam's razor," seeking the evolutionary scenario that requires the fewest number of character state changes across a given phylogenetic tree. Algorithms like Fitch's method perform a postorder traversal from tips to root, assigning ancestral character states by set intersection or union, followed by a preorder traversal to finalize state assignments [2]. While computationally efficient and intuitively appealing, MP assumes changes between all states are equally likely and does not account for variation in evolutionary rates or branch lengths, making it susceptible to error in scenarios involving rapid evolution or long branches [2].

Maximum Likelihood (ML) and the Mk2 Model: ML methods treat ancestral states as parameters to be estimated, seeking values that maximize the probability of the observed data under a specified model of evolution and a given phylogeny. The Mk2 model is a standard Markov model for discrete character evolution. These approaches employ a probabilistic framework, typically using a time-reversible continuous-time Markov process to compute the likelihood of a phylogeny by summing transition probabilities over all possible ancestral states at each node [2]. ML methods directly incorporate branch length information, providing a more statistically robust framework than parsimony.

*State-Dependent Speciation and Extinction (SSE) Models (e.g., BiSSE): The BiSSE (Binary State Speciation and Extinction) model represents a significant advance in model realism by simultaneously modeling the evolution of a binary character and the phylogenetic branching process. Unlike other methods, BiSSE allows rates of speciation (λ), extinction (μ), and character-state transition (q) to depend on the current state of the character [9]. This explicitly accounts for the possibility that a trait might influence its own evolutionary destiny, for instance, by increasing the rate of lineage diversification.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The performance of these methods has been rigorously evaluated through simulation studies, revealing a clear relationship between model realism and reconstruction accuracy. The following table summarizes the key comparative findings:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Ancestral State Reconstruction Methods

| Method | Key Assumptions | Computational Cost | Best-Suited Scenarios | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Parsimony | Changes are rare; all changes equally likely [2]. | Low | Small datasets; few state changes; closely related taxa. | Highly inaccurate under high rates of change; ignores branch lengths; no statistical uncertainty [9] [2]. |

| Mk2 Model (ML) | Homogeneous, time-reversible Markov process of character change [2]. | Moderate | General-purpose use when trait is not linked to diversification. | Inaccurate under state-dependent speciation/extinction; assumes trait neutrality [9]. |

| BiSSE Model | Character state affects speciation/extinction rates [9]. | High | Non-neutral traits; direct testing of trait-dependent diversification hypotheses. | Prone to error if unobserved traits drive diversification; requires larger datasets [9]. |

A comprehensive simulation study evaluating MP, Mk2, and BiSSE under a wide range of evolutionary scenarios demonstrated that error rates for all methods increased with node depth, the true number of state transitions, and rates of state transition and extinction, sometimes exceeding 30% for the deepest nodes [9]. However, the key finding was that BiSSE consistently outperformed both MP and Mk2 in scenarios where either speciation or extinction was state-dependent [9]. Furthermore, where rates of character-state transition were asymmetrical, error rates were greatest when the rate away from the ancestral state was largest, a scenario that BiSSE was best equipped to handle.

Table 2: Impact of Evolutionary Conditions on Reconstruction Accuracy

| Evolutionary Condition | Impact on Reconstruction Accuracy | Best-Performing Method |

|---|---|---|

| High Extinction Rate (e.g., μ=0.8) | Increases error rates for all nodes [9]. | BiSSE |

| Asymmetrical Transition Rates (q01 >> q10) | Higher error rates, especially when ancestral state is unfavored [9]. | BiSSE |

| Increasing Node Depth | Error rates increase for all methods [9]. | BiSSE |

| State-Dependent Speciation | MP and Mk2 show significantly elevated error rates [9]. | BiSSE |

| Neutral Trait Evolution | All methods more accurate; smaller performance gaps [9]. | Mk2 / BiSSE |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

The comparative data presented above is derived from sophisticated simulation frameworks and empirical validation studies. The following protocols detail how the performance of ancestral reconstruction methods is benchmarked.

Simulation-Based Benchmarking Protocol

This protocol is used to generate ground-truth data with known ancestral states to test different methods.

- Simulate Evolutionary History: Using a model like BiSSE, simulate phylogenetic trees and associated binary character data simultaneously. Parameters for state-dependent speciation (λ0, λ1), extinction (μ0, μ1), and character transition (q01, q10) are defined. The root state is typically fixed to a known value (e.g., state 0) [9].

- Generate Replicate Datasets: Conduct a large number of simulations (e.g., 500 trees per scenario) across a wide range of parameters to test method performance under various evolutionary conditions, including symmetrical and highly asymmetrical rates [9].

- Apply Reconstruction Methods: Reconstruct ancestral states on the simulated trees using the methods under investigation (e.g., MP, Mk2, BiSSE).

- Quantify Accuracy: Compare the inferred ancestral states to the known simulated states. Common metrics include:

- Overall Error Rate: The proportion of all internal nodes for which the state was incorrectly inferred.

- Node-Depth-Specific Error: How accuracy decays from tips to the root.

- Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR): Measures the trade-off between precision and recall for edge prediction in network contexts [24].

Empirical Validation with Experimental Biochemistry

This protocol validates computationally inferred ancestral sequences through synthesis and functional characterization.

- Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR): Collect extant protein sequences from a phylogenetically diverse set of species. Infer the sequences of ancestral proteins at specific nodes of the phylogeny using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods [3].

- Gene Synthesis and Protein Purification: Synthesize the coding sequences for the inferred ancestral genes, clone them into expression vectors, and purify the proteins from a heterologous system like E. coli [3].

- Functional Biochemical Assays:

- Specificity Profiling: Use techniques like positional-scanning peptide libraries (PSPL) to determine the substrate specificity of the reconstructed ancestral kinases [3].

- Activity Measurement: Assess basal catalytic activity using generic substrates like Myelin Basic Protein (MBP) to quantify autophosphorylation capability and dependence on upstream activators [3].

- Identify Key Evolutionary Mutations: Use targeted mutagenesis to revert specific residues in modern proteins to their inferred ancestral states, and vice-versa, to test hypotheses about the functional impact of specific historical substitutions [3].

Advanced Frameworks: Joint Reconstruction and Uncertainty Quantification

A significant limitation of traditional marginal reconstruction is its focus on individual nodes, which fails to capture the dependency of evolutionary histories. A new paradigm, joint ancestral reconstruction, estimates the full sequence of states across all nodes of the tree [26].

Novel algorithms have been developed to efficiently estimate all relevant ancestral histories and quantify the uncertainty of joint ASR. Simulation studies demonstrate that joint reconstructions have higher accuracy than their marginal counterparts [26]. Furthermore, the uncertainty surrounding the best joint reconstruction can be biologically meaningful. For example, when applied to epidemic multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, joint ASR revealed that the evolution of antibiotic resistance is not a single narrative but a series of competing histories, each with distinct phenotype-genotype transitions that traditional marginal approaches would struggle to identify [26].

Diagram 1: Marginal vs. Joint Reconstruction. Joint reconstruction infers a single, cohesive evolutionary history, making the state transition (1→0) on a specific branch explicit.

Case Study: Evolutionary Reconstruction of ERK Regulatory Evolution

The power of ancestral reconstruction is exemplified by research into the evolution of ERK kinase regulation. The study reconstructed the lineage leading to modern ERK1 and ERK2 to understand how their tight control by the upstream kinase MEK evolved [3].

Researchers reconstructed ancestral kinases, synthesized their genes, and purified the proteins. Biochemical assays revealed a dramatic switch from high to low autophosphorylation activity at the transition to the inferred ancestor of ERK1 and ERK2 (AncERK1-2), indicating the emergence of dependence on MEK [3]. Through mutagenesis, they pinpointed two synergistic amino acid changes responsible: a shortening of the β3-αC loop and a mutation of the gatekeeper residue. Reversing these two mutations to their ancestral state in modern ERK1 and ERK2 was sufficient to restore autoactivation, eliminating dependence on MEK in human cells [3]. This study showcases how ASR can move beyond correlation to identify precise mechanistic steps in regulatory evolution.

Diagram 2: Key Regulatory Transition in ERK Evolution. Two mutations led to MEK dependence; reverting them restored autoactivation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ancestral Reconstruction Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Software (e.g., RevBayes, BEAST, diversitree) | Infers phylogenetic trees and performs ASR under probabilistic models. | Used to infer the evolutionary relationships of extant sequences and reconstruct ancestral nodes [9] [3]. |

| diversitree R package | Provides functions for analyzing comparative phylogenetic data, including the BiSSE model. | Used to simulate trait-dependent evolution and fit complex state-dependent models [9]. |

| Gene Synthesis Services | Chemically synthesizes the DNA sequence of inferred ancestral genes for experimental testing. | Essential for expressing and purifying ancestral proteins for biochemical characterization [3]. |

| Positional-Scanning Peptide Library (PSPL) | A high-throughput biochemical method for determining kinase substrate specificity. | Used to characterize the specificities of reconstructed ancestral kinases and compare them to modern ones [3]. |

| Myelin Basic Protein (MBP) | A generic kinase substrate used in in vitro kinase activity assays. | Used to measure and compare the basal catalytic activity of reconstructed ancestral kinases [3]. |

Methodological Toolkit: From Parsimony to Machine Learning for GRN Inference

Maximum Parsimony (MP) represents one of the most intuitive and historically significant optimality criteria in phylogenetic inference, with particular relevance for ancestral state reconstruction in evolutionary studies. In phylogenetics and computational phylogenetics, maximum parsimony is defined as an optimality criterion under which the phylogenetic tree that minimizes the total number of character-state changes (or minimizes the cost of differentially weighted character-state changes) is considered optimal [27]. The fundamental principle underpinning MP is the minimization of homoplasy—convergent evolution, parallel evolution, and evolutionary reversals—thereby seeking the simplest possible explanation for the observed data [27]. This principle aligns with the scientific concept of Occam's razor, which favors simpler explanations over more complex ones when both account for the observations equally well.

In the context of regulatory network evolution research, MP methods provide a critical framework for inferring historical evolutionary pathways. These methods enable researchers to reconstruct ancestral gene regulatory states and identify key evolutionary transitions by analyzing patterns of character state changes across phylogenetic trees. The application of MP is especially valuable for investigating the evolution of developmental processes, such as the emergence of terrestrial adaptations in animals [15] or the conservation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis pathways in plants [16], where understanding ancestral states informs our comprehension of evolutionary constraints and innovations.

Core Algorithmic Framework: Maximum Parsimony and Fitch's Method

The Maximum Parsimony Principle

The maximum parsimony approach operates on character-based data, where discrete characters (morphological traits or molecular sequence positions) are scored across a set of taxa. For a given phylogenetic tree, the parsimony score represents the minimum number of character-state changes required to explain the observed data. Under the MP criterion, the tree requiring the fewest total evolutionary changes across all characters is considered optimal [27]. Mathematically, if we consider a phylogenetic tree ( T ) and a character ( f ) that assigns states to the leaves, the parsimony score of ( f ) on ( T ) is the minimum number of state changes along the edges of ( T ) needed to explain the evolution of ( f ) [28].

The search for the most parsimonious tree faces significant computational challenges due to the vast number of possible tree topologies. For small numbers of taxa (fewer than nine), an exhaustive search evaluating every possible tree is feasible. For nine to twenty taxa, branch-and-bound algorithms guarantee finding the optimal tree, while for larger datasets, heuristic search methods must be employed [27].

Fitch's Algorithm: Methodology and Workflow

Fitch's algorithm, introduced by Walter M. Fitch in 1971, represents one of the most widely used parsimony methods for ancestral state reconstruction [27] [29]. This algorithm operates through a two-stage process on a rooted phylogenetic tree:

- Stage 1: Leaf-to-root pass - This stage assigns a set of candidate states to each node through post-order traversal (from tips to root)

- Stage 2: Root-to-leaf pass - This stage selects specific states from the candidate sets through pre-order traversal (from root to tips)

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of Fitch's algorithm:

Fitch's Algorithm Workflow

In the first stage, the algorithm proceeds from leaves to root, assigning state sets to each internal node as follows: if the intersection of the children's state sets is non-empty, that intersection becomes the parent's state set; if empty, the union is taken instead and the parsimony score is incremented by one [29] [30]. In the second stage, the root is assigned a state chosen randomly from its state set, then the algorithm proceeds root-to-leaves: each child node selects its state from its set, preferentially choosing the parent's state if available [29].

The Fitch method operates under several key assumptions: (1) characters evolve independently, (2) state changes are rare, and (3) the phylogenetic tree accurately represents evolutionary relationships. Violations of these assumptions can impact reconstruction accuracy, particularly when evolutionary rates are high or when substantial homoplasy exists in the dataset [31] [29].

Performance Comparison: Maximum Parsimony vs. Alternative Methods

Theoretical Foundations and Statistical Properties

Maximum Parsimony has faced significant theoretical scrutiny regarding its statistical properties. A critical finding by Joe Felsenstein demonstrated that maximum parsimony can be statistically inconsistent under certain conditions, particularly in cases of long-branch attraction, where rapidly evolving lineages may be erroneously grouped together despite not sharing recent common ancestry [27]. This inconsistency means that MP is not guaranteed to produce the true tree with high probability, even given sufficient data.

In contrast, model-based methods like Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference explicitly model evolutionary processes and can incorporate complex patterns of sequence evolution. These methods generally demonstrate better statistical consistency, though they require correct model specification and incur greater computational costs [31].

Empirical Performance Across Evolutionary Contexts

The performance of Maximum Parsimony varies considerably across different evolutionary contexts and data characteristics. The following table summarizes key comparative performance metrics based on empirical and simulation studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Phylogenetic Inference Methods

| Performance Metric | Maximum Parsimony | Bayesian Inference | Maximum Likelihood |

|---|---|---|---|

| Handling Character Dependency | Performs poorly without specialized coding; contingent coding recommended [31] | Superior performance; naturally handles character dependency through probabilistic modeling [31] | Moderate performance; depends on model specification [31] |

| Accuracy with Few Substitutions | High accuracy when k < n/8 + 11/9 - 1/18√(9×(n/4)²+16) [28] | Moderate accuracy; may overparameterize simple datasets [28] | Moderate accuracy; similar to Bayesian for simple datasets [29] |

| Long-Branch Attraction | Highly susceptible [27] | Resistant with appropriate model [31] | Resistant with appropriate model [31] |

| Computational Efficiency | Fast for small datasets; heuristic search needed for large datasets [27] | Computationally intensive regardless of dataset size [31] | Computationally intensive for large datasets [31] |

| Theoretical Consistency | Can be inconsistent under certain conditions [27] | Statistically consistent with correct model [31] | Statistically consistent with correct model [31] |

| Saikochromone A | Saikochromone A, MF:C11H10O5, MW:222.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Rauvoyunine C | Rauvoyunine C|Alkaloids | Rauvoyunine C is a high-purity natural alkaloid for research use only (RUO). Isolated from Rauvolfia yunnanensis. Not for human or animal use. | Bench Chemicals |

The performance of Fitch's method specifically for ancestral state reconstruction has been rigorously evaluated under various evolutionary models. For N-state evolutionary models, the reconstruction accuracy depends heavily on tree topology and conservation probability. Studies have revealed that for equal-branch complete binary trees, there exists an equilibrium interval of conservation probability where the ambiguous reconstruction accuracy converges to 1/N (random chance) as the number of leaves increases [29]. This equilibrium interval varies with the number of character states, with the upper bound decreasing as the number of states increases.

Performance in Handling Character Dependency

A significant challenge in morphological phylogenetics is logical character dependency, where the state of one character depends on the state of another. This problem frequently arises in analyses of major evolutionary transitions, such as the origin of limbs or floral structures [31]. The following table compares different approaches for handling character dependency:

Table 2: Comparison of Methods for Handling Character Dependency

| Method | Approach | Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contingent Coding | Hierarchical character coding where secondary characters only apply when primary character is present | Most accurate among coding strategies for MP; minimizes spurious assignments [31] | Does not fully resolve the problem for MP; implementation complexity |

| Absent Coding | Secondary characters scored as absent when primary character is absent | Performs better in small datasets [31] | Higher error rates in complex datasets [31] |

| Multistate Coding | Combines primary and secondary characters into a single multi-state character | Moderate performance [31] | Can introduce artificial state relationships [31] |

| Bayesian Inference | Probabilistic modeling of character dependencies | Outperforms all parsimony-based solutions [31] | Computational intensity; model specification challenges |

Recent research indicates that Bayesian inference substantially outperforms all parsimony-based solutions for handling character dependency, due to fundamental differences in their optimization procedures [31]. However, the study also notes that regardless of the optimality criterion, estimation becomes increasingly challenging as the number of primary characters bearing secondary traits increases, owing to considerable expansion of the tree parameter space.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Benchmarking Maximum Parsimony Accuracy

The reconstruction accuracy of Maximum Parsimony methods can be quantified using carefully designed simulation experiments. A standard protocol involves:

Tree Simulation: Generating model phylogenetic trees with known topologies and branch lengths. Common topologies for benchmarking include complete binary trees and comb-shaped trees, which represent extremal cases of tree balance [29].

Sequence Evolution Simulation: Evolving artificial sequences along the model tree according to specified substitution models (e.g., N-state Jukes-Cantor model). The conservation probability (q) represents the probability that a state remains unchanged along a branch [29].

Reconstruction and Comparison: Applying MP reconstruction to the simulated sequences and comparing the inferred ancestral states to the known simulated states.

The accuracy metrics typically include unambiguous reconstruction accuracy (probability that the inferred state matches the true state) and ambiguous reconstruction accuracy (accounting for cases where multiple equally parsimonious states exist) [29].

Novel Validation in Genome Evolution Studies

Recent research on convergent genome evolution during animal terrestrialization demonstrates innovative applications of MP principles. The InterEvo (intersection framework for convergent evolution) approach identifies intersections of biological functions between different sets of genes independently gained or reduced across multiple terrestrialization events [15]. This framework:

- Analyzes 154 genomes from 21 animal phyla

- Reconstructs protein-coding content of ancestral genomes linked to 11 independent terrestrialization events

- Identifies convergent gene gain and loss patterns using parsimony principles

- Annotates functions of novel genes using Gene Ontology terms and Pfam protein domains [15]

The experimental workflow for such genome-scale comparative analyses can be visualized as follows:

Genome Evolution Analysis Workflow

This approach revealed that most terrestrialization events display high levels of gene turnover, reflecting genome plasticity during the water-to-land transition. Specifically, novel gene families that emerged independently in different terrestrialization events are involved in osmosis regulation, metabolism, reproduction, detoxification, and sensory reception [15].

Applications in Regulatory Network Evolution Research

Case Study: Ancestral State Reconstruction in Plant Cell Walls

Research on silver birch (Betula pendula) demonstrates the application of ancestral state reconstruction principles to understand regulatory network evolution. The study combined co-expression and promoter motif analysis to construct regulatory networks for primary and secondary cell wall biosynthesis [16]. By employing multispecies network analysis including birch, poplar, and eucalyptus, researchers identified conserved regulatory interactions and determined that lignin biosynthesis represents the least conserved pathway [16].

This approach revealed that the secondary cell wall biosynthesis co-expression module was enriched with whole-genome multiplication duplicates, and while regulator genes were under positive selection, others evolved under relaxed purifying selection [16]. The study concluded that silver birch retains a relatively simple ancestral state of secondary cell wall biosynthesis regulation still present in core eudicots, providing insights into the evolutionary history of wood formation in flowering plants.

Emerging Approaches: History sDAG for Parsimony Deviations