The Uncultured Majority: Navigating the Challenges and Opportunities in Prokaryotic Taxonomy for Drug Discovery

The vast majority of prokaryotes resist cultivation in the laboratory, creating a fundamental challenge for taxonomy and limiting access to a potential treasure trove of novel natural products.

The Uncultured Majority: Navigating the Challenges and Opportunities in Prokaryotic Taxonomy for Drug Discovery

Abstract

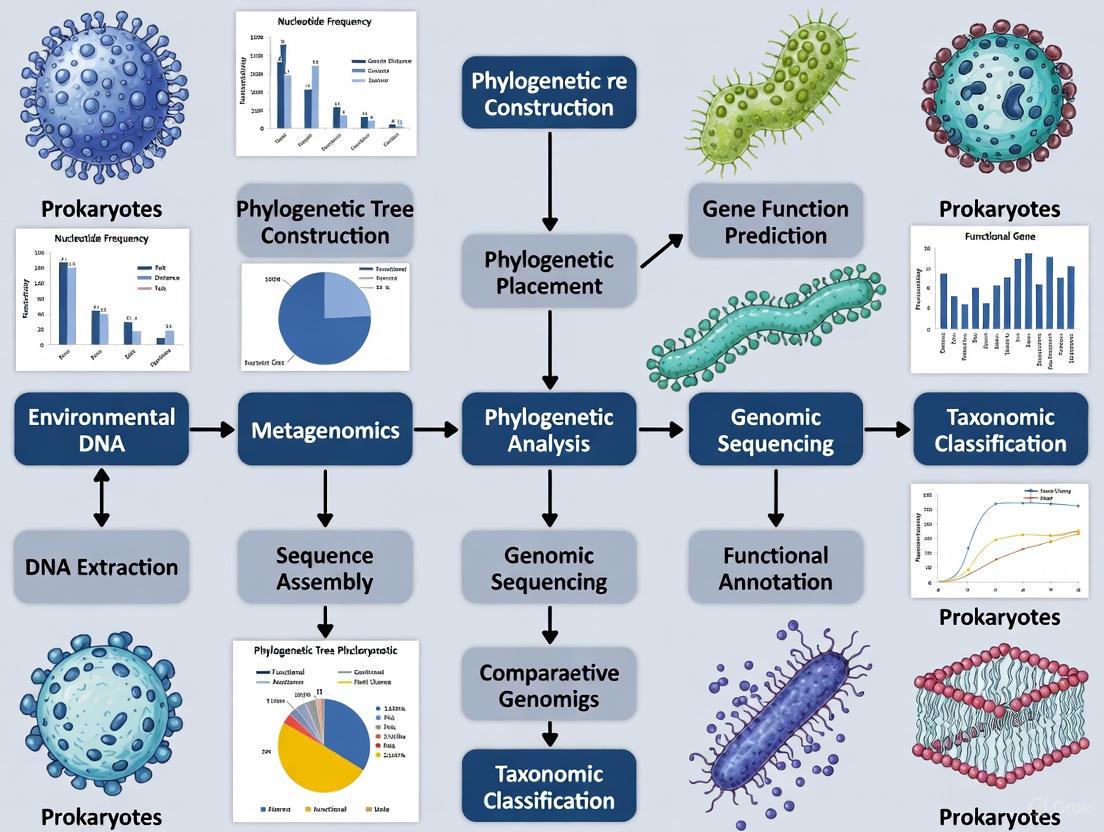

The vast majority of prokaryotes resist cultivation in the laboratory, creating a fundamental challenge for taxonomy and limiting access to a potential treasure trove of novel natural products. This article explores the paradigm shift in microbial classification, moving from traditional phenotype-based methods to genome-centric frameworks in the age of big sequence data. We examine the methodological advances in metagenomics and single-cell genomics that are revealing the 'microbial dark matter,' the ongoing debates in nomenclature and classification for these uncultured organisms, and the practical implications for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to harness this uncultured diversity for biomedical applications, including the discovery of new antibiotics.

The Unseen World: Why Uncultured Prokaryotes Challenge Traditional Taxonomy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the "Great Plate Count Anomaly"? The "Great Plate Count Anomaly" describes the discrepancy, often by orders of magnitude, between the number of microbial cells observed by direct microscopy in an environmental sample and the number of colonies that grow on a petri dish using standard plating techniques [1]. In many environments, like oceans, traditional plating methods recover only 0.01 to 0.1% of bacterial cells, while over 99% remain uncultured [1] [2].

Why is it so difficult to culture most prokaryotes? Most environmental prokaryotes are free-living oligotrophs adapted to low nutrient concentrations, which are drastically exceeded by standard laboratory media [3]. Key challenges include:

- Unknown Growth Requirements: Many require specific, uncharacterized nutrients, signaling molecules, or co-factors [2].

- Microbial Interdependencies: They may depend on other microbes for essential nutrients or detoxification of harmful metabolites (syntrophy) [3] [2].

- Slow Growth: They are often outcompeted by fast-growing "copiotrophs" (fast-growing bacteria that thrive in nutrient-rich conditions) under standard lab conditions [3] [2].

- Dormancy: Cells may be in a dormant state and unable to immediately adjust to lab conditions [1].

How does the cultivation gap affect prokaryotic taxonomy and drug discovery? The cultivation gap creates a massive bias in our understanding of microbial life, leaving a vast reservoir of genetic and metabolic diversity unexplored [4] [5].

- Taxonomy: Current taxonomy is based on a tiny, non-representative fraction of microbial diversity. This skews the tree of life, as over 85% of microbial phyla have no cultured representatives [4] [5].

- Drug Discovery: Uncultured microbes represent an untapped source of novel biosynthetic gene clusters and enzymes with potential for developing new antibiotics and therapeutics [6].

What modern methods are used to study uncultured microbes?

- Culture-Independent Genomics:

- High-Throughput Cultivation (HTC): Using dilution-to-extinction in low-nutrient media to mimic natural conditions and isolate slow-growing oligotrophs [1] [3].

Troubleshooting Common Cultivation Experiments

Issue 1: Low Colony Yield on Agar Plates

This is the direct manifestation of the Great Plate Count Anomaly.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Nutrient-rich media inhibits oligotrophs. | Use low-nutrient media (e.g., 1/10 R2A, sterilized natural water, or defined oligotrophic media) [1] [3]. |

| Fast-growing copiotrophs outcompete target cells. | Apply high-throughput dilution-to-extinction cultivation to physically separate cells and prevent competition [1] [3]. |

| Agar is toxic to some cells. | Reduce agar concentration or use gelling agents like gellan gum (Gelrite) [2]. |

| Incorrect incubation time. | Extend incubation time from days to weeks to allow slow-growing colonies to appear [1]. |

Detailed Protocol: High-Throughput Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation

- Principle: To isolate cells by extreme dilution into low-nutrient media, minimizing competition and mimicking in situ substrate levels [1] [3].

- Procedure:

- Prepare Media: Use a defined, low-carbon medium or filter-sterilized water from the sample environment. Carbon concentrations should be in the µM range (e.g., 1-2 mg Dissolved Organic Carbon per liter) [3].

- Dilute Inoculum: Dilute a fresh environmental sample in the prepared medium to a final concentration of approximately 1 to 5 cells per well [1] [3].

- Distribute Aliquots: Dispense 1-ml aliquots into the wells of 48- or 96-well microtiter plates [1] [3].

- Incubate: Incubate plates in the dark at a temperature relevant to the sample's environment (e.g., 16°C for lakes) for 6 to 8 weeks [3].

- Screen for Growth: Monitor for growth using sensitive methods like fluorescence microscopy after DAPI staining or by measuring turbidity [1].

Diagram 1: High-throughput dilution-to-extinction workflow.

Issue 2: Different Counts Between Technical Replicates

Microbiological plate counting is an inherently imprecise technique, especially at low colony numbers, as colony-forming units (CFUs) follow a Poisson distribution [8].

| Number of Colonies Counted (on a plate) | Approximate 95% Confidence Interval | Error as % of Mean |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 4 to 16 | ±60% |

| 100 | 80 to 120 | ±20% |

| 500 | 455 to 545 | ±9% |

Guidance for Accurate Counting and Reporting:

- Countable Range: For a standard 90mm agar plate, the statistically reliable countable range is 25 to 250 colonies [9] [8]. Counts outside this range should be reported as estimates.

- Use Replicates: Perform tests in replicates (at least duplicates) to improve precision [8].

- Calculate CFU:

Issue 3: Cultivating Strict Anaerobes

Obligate anaerobes are poisoned by oxygen, requiring its complete exclusion [2].

Detailed Protocol: Anaerobic Cultivation Using the Hungate Method

- Principle: To create and maintain a strict oxygen-free environment using pre-reduced media and an inert gas atmosphere [2].

- Procedure:

- Media Preparation: Boil the medium to drive off dissolved oxygen. Continuously sparge with an oxygen-free gas (e.g., Nâ‚‚ or COâ‚‚) during cooling and dispensing.

- Add Reducing Agent: Add a reducing agent like cysteine sulfide or sodium sulfide to the medium to lower the redox potential.

- Dispense Anaerobically: Dispense media into tubes or bottles under a constant stream of inert gas.

- Seal: Seal tubes with butyl rubber stoppers that are impermeable to oxygen.

- Autoclave: Autoclave the sealed tubes.

- Inoculate: Use syringes to inoculate through the rubber stopper, avoiding the introduction of air [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Defined Oligotrophic Media | Mimics natural substrate concentrations (µM range) to avoid inhibiting oligotrophs adapted to low nutrients [3]. |

| Marine R2A Agar (and dilutions) | A low-nutrient medium; a 1/10 dilution (1/10R2A) is often more effective for isolating environmental bacteria than full-strength media [1]. |

| Microtiter Plates (48- or 96-well) | Enables high-throughput dilution-to-extinction culturing, allowing thousands of cultures to be processed simultaneously [1] [3]. |

| Butyl Rubber Stoppers & Serum Bottles | Creates an airtight seal for cultivating anaerobic microorganisms, preventing oxygen ingress [2]. |

| Gelling Agents (Gelrite/Gellan Gum) | A potential alternative to agar, as some bacteria are sensitive to agar impurities [2]. |

| Cell Array Manifold | A custom filter manifold that allows efficient screening of dozens of microtiter plate wells for microbial growth via microscopy [1]. |

| CheckM Software | A bioinformatic tool used to assess the quality and completeness of Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) and Single-Amplified Genomes (SAGs) based on single-copy marker genes [6]. |

| SeqCode Registry | A registry for formally naming uncultivated prokaryotes based on genome sequences (MAGs/SAGs), bypassing the requirement for a physical culture [5]. |

| Tolprocarb | Tolprocarb, CAS:911499-62-2, MF:C16H21F3N2O3, MW:346.34 g/mol |

| Ibrutinib dimer | Ibrutinib dimer, CAS:2031255-23-7, MF:C50H48N12O4, MW:881.0 g/mol |

Advanced Strategy: Growth-Curve-Guided Isolation

For particularly fastidious organisms, a targeted, data-driven approach can improve success.

Protocol: Growth-Curve-Guided Isolation [2]

- Initial Enrichment: Inoculate the environmental sample into a suitable liquid medium.

- Monitor Growth: Use optical density (OD) or quantitative PCR (qPCR) to track the growth curve of the total community and, if possible, the target microbe specifically.

- Identify Key Phase: Sample the culture during its late exponential or early stationary phase. This is when the target microbe is most active and abundant, before being outcompeted.

- Strategic Dilution: Use this sample for dilution-to-extinction plating or further dilutions. The goal is to transfer cells when their relative fitness is highest.

- Apply Selective Pressure: Establish conditions that provide a relative growth advantage for the target (e.g., using specific carbon sources, antibiotics, or pH) while inhibiting non-target microbes [2].

Diagram 2: Growth-curve-guided isolation strategy.

Historical Background: The Phenotype Era and its Limitations

What was the traditional basis for classifying prokaryotes, and why was it problematic?

For centuries, prokaryotic classification relied almost exclusively on observable phenotypic characteristics. This approach, often termed the "phenotype era," depended on morphological, biochemical, and physiological traits [10]. The first edition of Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology (1923) categorized bacteria into a nested hierarchical classification using identification keys and tables of distinguishing characteristics [10]. This system relied heavily on:

- Morphology: Cell shape and structural features

- Culturing conditions: Growth requirements and environmental preferences

- Biochemical traits: Metabolic capabilities and reaction patterns

- Pathogenic characteristics: Disease-causing capabilities in hosts

However, phenotypic classification provided little insight into deep evolutionary relationships of microorganisms [10]. Stanier and van Niel famously concluded during the 1940s-1960s that it was "a waste of time for taxonomists to attempt a natural system of classification for bacteria" based solely on phenotype [10]. The limitations became increasingly apparent as scientists recognized that phenotypic similarities often masked fundamental genetic differences, much like the historical misclassification of hippos with pigs based on anatomical similarities rather than their actual evolutionary relationship to whales [10].

What conceptual development helped frame this historical divide?

The genotype-phenotype distinction, first proposed by Wilhelm Johannsen in 1909-1911, provided an important conceptual framework for understanding heredity [11] [12]. Johannsen introduced these terms in his pure-line breeding experiments on barley and beans, defining:

- Genotype: The hereditary constitution of an organism

- Phenotype: The observable characteristics that develop through the interaction of genotype and environment [12]

This distinction emerged as part of Johannsen's campaign against the "transmission conception" of heredity, which suggested that parental traits were directly transmitted to offspring [11]. Instead, Johannsen viewed the genotype as a stable, ahistorical disposition that could produce different phenotypes under varying environmental conditions—a concept he equated with Richard Woltereck's "norm of reaction" (Reaktionsnorm) [11] [12].

The Great Plate Count Anomaly: A Fundamental Technical Challenge

Why can't we culture most microorganisms, and how does this limit phenotypic classification?

The "great plate count anomaly" describes the dramatic discrepancy between the number of microbial cells observed under microscopy and the fraction that can be cultured in the laboratory [13]. Different environments, including seawater, soil, and marine sediments, typically yield only 0.01-1% of observable microorganisms using artificial media [13]. This anomaly represents a fundamental technical challenge for phenotype-based taxonomy because:

- Uncultured majority: The vast majority of microbial diversity remains inaccessible for phenotypic characterization

- Cultural bias: Taxonomic knowledge becomes skewed toward "easy growers" with readily replicated laboratory requirements

- Missing diversity: Environmental functions and ecological contributions of uncultured microbes remain unknown

What factors contribute to the great plate count anomaly?

Multiple interrelated factors limit microbial culturability [13]:

Table: Primary Factors Limiting Microbial Cultivation

| Factor Category | Specific Challenges | Potential Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Requirements | Lack of essential nutrients; media too rich or poor | Diffusion chambers; substrate supplementation |

| Biological Interdependencies | Obligate mutualisms; auxotrophy | Co-culture systems; helper strains |

| Environmental Conditions | Inappropriate pH, salinity, temperature | Environmental simulation; gradient cultures |

| Microbial Characteristics | Slow growth; small cell size | Extended incubation; cell encapsulation |

The recognition of this vast uncultured microbial world, often called "microbial dark matter," necessitated a fundamental shift away from phenotype-dependent classification systems [13] [14].

The Molecular Revolution: Genotype Takes Center Stage

What technological advances enabled the shift to genotype-based classification?

The transition from phenotypic to genotypic classification became possible through several key technological developments:

16S rRNA as a Molecular Chronometer Carl Woese's pioneering work with small subunit ribosomal RNA (16S/18S rRNA) provided the first universal molecular framework for microbial classification [10] [15]. The 16S rRNA gene offered ideal properties as a molecular chronometer:

- High conservation: Essential structural and functional roles maintain sequence stability

- Variable regions: Permitted distinction between closely related organisms

- Universal distribution: Present in all prokaryotes, enabling comprehensive phylogenetic comparisons

This molecular approach revealed astonishing microbial diversity previously undetectable by phenotypic methods, most dramatically exemplified by the discovery of Archaea as a completely new domain of life [10].

Shotgun Sequencing and Metagenomics The development of metagenomics—direct sequencing of genetic material from environmental samples—bypassed the need for cultivation entirely [13] [15]. This approach:

- Eliminates cultural bias: Provides access to genetic information from uncultured organisms

- Reveals community structure: Identifies relative abundances of different taxa within samples

- Enables functional profiling: Links metabolic capabilities to specific community members

Key technical improvements, including bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) for cloning environmental DNA and advanced bioinformatics for sequence assembly, made metagenomic approaches increasingly powerful [15].

Table: Evolution of Genotypic Classification Methods

| Method | Time Period | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-DNA Hybridization [10] | 1960s-1980s | Direct comparison of overall genome similarity | Limited to cultivated strains; no deep phylogeny |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing [10] [15] | 1970s-present | Universal phylogenetic framework | Limited resolution at species level |

| Multilocus Sequence Typing [10] | 1990s-present | Improved strain discrimination | Requires multiple primer sets |

| Metagenomic Shotgun Sequencing [13] [15] | 2000s-present | Culture-independent; functional insights | Assembly challenges; population heterogeneity |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual and methodological shift from phenotype-based to genotype-based classification:

Modern Workflows: Obtaining Genomes from Uncultured Microorganisms

What methods are currently used to obtain genome sequences from uncultured microbes?

Contemporary approaches for accessing uncultured microbial genomes primarily utilize two complementary strategies:

Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) MAGs are reconstructed from mixed environmental sequences through:

- Shotgun sequencing: Random fragmentation and sequencing of all DNA in a sample

- Binng: Grouping sequences based on composition (GC content, k-mer frequency) and abundance

- Quality assessment: Evaluating completeness and contamination using single-copy marker genes [16]

Single-Cell Amplified Genomes (SAGs) SAGs utilize microfluidic isolation and whole-genome amplification:

- Single-cell isolation: Physical separation of individual cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting or microfluidics

- Whole-genome amplification: Multiple displacement amplification (MDA) with phi29 DNA polymerase

- Computational cleaning: Removing chimeric sequences and coverage biases [14]

How does the ccSAG workflow improve single-cell genome quality?

The Cleaning and Co-assembly of a Single-Cell Amplified Genome (ccSAG) workflow addresses key limitations of single-cell genomics [14]:

Table: ccSAG Workflow Steps and Functions

| Step | Process | Purpose | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAG Grouping | 16S rRNA similarity ≥99%; ANI >95% | Identify closely related cells | Groups for co-assembly |

| Cross-reference Mapping | Map reads to raw contigs | Identify chimeric sequences | Classification into clean/chimeric/unmapped |

| Chimera Splitting | Split partially aligned reads | Rescue genetic information | Increased valid sequence recovery |

| Co-assembly | De novo assembly of clean reads | Generate composite genome | High-quality draft genomes |

The ccSAG workflow typically integrates 5-6 SAGs to achieve optimal completeness (>96%) with minimal contamination (<1.25%), producing genomes comparable to those from cultured isolates [14]. The following diagram illustrates this process:

Current Challenges and Future Directions

What major challenges remain in prokaryotic taxonomy of uncultured organisms?

Despite significant advances, several persistent challenges complicate genotype-based classification:

Nomenclature and Classification Standards The International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (ICNP) currently requires cultivation for valid naming, creating a discrepancy between sequenced and officially recognized taxa [10] [16]. This has led to:

- Unnamed diversity: Numerous genomic sequences without formal taxonomic placement

- Database inconsistencies: Variation in naming conventions across public repositories

- Communication barriers: Difficulty discussing uncultured taxa in scientific literature

The recently developed SeqCode (Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes Described from Sequence Data) aims to address these issues by establishing standards for naming uncultivated prokaryotes based on DNA sequence data [16].

Genome Quality and Interpretation The variable quality of MAGs and SAGs presents challenges for comparative genomics:

- Fragmentation: Incomplete genomes hinder comprehensive functional analysis

- Contamination: Mis-binning can introduce foreign sequences

- Metapopulation averaging: MAGs may represent composite populations rather than individual strains

How is the genotype-phenotype relationship being redefined in modern microbiology?

Contemporary research recognizes that the relationship between genotype and phenotype is complex and multidimensional [17]. The "genotype-to-phenotype problem" refers to the challenge of predicting organismal characteristics from genetic information alone [17]. Systems biology approaches are addressing this by:

- Network analysis: Viewing cellular processes as interconnected networks rather than linear pathways

- High-dimensional phenotyping: Integrating morphological, transcriptional, protein, and metabolic data

- Natural variation studies: Leveraging quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping in diverse populations

This refined understanding acknowledges that while genotype provides the essential blueprint for classification, phenotypic expression remains context-dependent and influenced by environmental factors, regulatory networks, and community interactions [11] [17].

What key resources support modern genotype-based taxonomy?

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Databases for Genotype-Based Taxonomy

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDP [10] | Database | 16S/28S rRNA sequence analysis and classification | https://rdp.cme.msu.edu/ |

| SILVA [10] | Database | Comprehensive rRNA database for Bacteria, Archaea, Eukaryotes | https://www.arb-silva.de/ |

| GTDB [10] | Database | Genome-based taxonomy using evolutionary framework | https://gtdb.ecogenomic.org/ |

| Phi29 DNA Polymerase [14] | Reagent | Multiple displacement amplification for SAGs | Commercial suppliers |

| Nextera XT [14] | Reagent | Library preparation for metagenomic sequencing | Illumina |

| SPAdes [14] | Software | Assembly of single-cell genomes despite uneven coverage | https://cab.spbu.ru/software/spades/ |

The transition from phenotype to genotype represents more than just a technical shift in methodology—it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how we conceptualize, categorize, and understand microbial diversity. This paradigm shift has revealed a biological universe far more vast and complex than previously imagined, while simultaneously presenting new challenges in standardization, interpretation, and functional characterization. As genomic technologies continue to evolve and new computational approaches emerge, the principles of prokaryotic taxonomy will likely continue to refine our understanding of life's invisible majority.

The 16S rRNA Revolution and Its Limitations for Deep Phylogeny

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can I reliably identify bacterial species using 16S rRNA gene sequencing?

For species-level identification, 16S rRNA sequencing has significant limitations. While it is excellent for genus-level classification, its resolution at the species level is often insufficient. Genomically distinct species can share nearly identical 16S rRNA sequences (>99.9% identity), blurring the lines between them [18] [19]. For accurate species identification, techniques offering higher genomic resolution, such as whole-genome sequencing for Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) analysis, are recommended [20].

Q2: Which hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene provide the best taxonomic resolution?

No single region is perfect, and the choice can influence your results. Some studies targeting the V5-V8 regions have reported challenges in distinguishing between closely related Lactobacillus species, which are common in genital tract microbiomes [21]. Full-length 16S rRNA sequencing, enabled by third-generation sequencing, provides greater taxonomic depth than short-read sequencing of individual hypervariable regions [22].

Q3: My sequencing results show high adapter dimer contamination. What went wrong?

A high presence of adapter dimers (sharp peaks around 70-90 bp on an electropherogram) typically indicates issues during library preparation. Common root causes include an suboptimal adapter-to-insert molar ratio (too much adapter) or inefficient purification that failed to remove these small artifacts [23]. Re-optimizing your ligation conditions and ensuring a rigorous clean-up step can resolve this.

Q4: What bioinformatic tools can improve species-level classification from 16S data?

Some classifiers are specifically designed to enhance species-level resolution. For full-length 16S sequences, SINTAX and SPINGO have been shown to provide high classification accuracy when used with the RDP reference database [22]. SPINGO is also noted as a useful tool for addressing the inherent limitations of short-read amplicons at the species level [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inability to Distinguish Between Closely Related Species

Problem: Your 16S rRNA sequencing data fails to resolve different species within a genus, even though other methods confirm their presence.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Confirm with Genomic Standards: Check if the species in question are known to have highly similar 16S rRNA sequences. Studies have found that bona fide species confirmed by whole-genome analysis can have 16S rRNA identities above the typical species threshold (e.g., >98.7%) [18].

- Use Advanced Classifiers: Implement species-specific classifiers like SPINGO in your bioinformatic pipeline, which can improve resolution [24].

- Shift to Higher-Resolution Methods: If species-level identification is critical for your project, consider moving to:

Issue 2: Low Library Yield or Poor Sequencing Quality

Problem: The final library concentration is unexpectedly low, or the sequencing output is poor.

Diagnosis and Solutions: Follow this diagnostic workflow to identify and correct common preparation errors:

Table: Common Causes and Corrective Actions for Library Prep Failures

| Root Cause | Failure Signals | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input DNA Quality | Degraded DNA, inhibitory contaminants | Re-purify sample; check 260/230 and 260/280 ratios [23]. |

| Fragmentation & Ligation Issues | Adapter-dimer peaks (~70-90 bp) | Titrate adapter-to-insert ratio; ensure fresh ligase [23]. |

| Amplification Problems | High duplicate rate, bias, artifacts | Reduce PCR cycle number; use high-fidelity polymerase [23]. |

| Purification & Cleanup Errors | Incomplete removal of dimers, high sample loss | Optimize bead-to-sample ratio; avoid bead over-drying [23]. |

Issue 3: Choosing a Sequencing Platform and Bioinformatics Pipeline

Problem: As a novice researcher, you are unsure which sequencing platform and bioinformatics pipeline to select for your project.

Diagnosis and Solutions: The optimal choice depends on your target taxonomic level and available resources. The following table summarizes findings from benchmarking studies that used a known mock microbial community [24]:

Table: Platform and Pipeline Selection Guide

| Sequencing Platform | Recommended Pipeline (for a novice) | Key Advantages | Limitations at Species Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina MiSeq (V3-V4 region) | VSEARCH, QIIME 1.9.1 | Lower error rate; competitive cost [24]. | All tested pipelines performed well at family/genus level but had limitations at species level [24]. |

| Ion Torrent PGM | QIIME 1.9.1 (default parameters) | Good for characterizing multiple hypervariable regions [24]. | Not suitable for detecting certain species like Bacteroides without modified pipeline [24]. |

| Third-Generation (Full-length 16S) | SINTAX or SPINGO with RDP database | Highest species-level accuracy [22]. | Higher computational cost; longer sequencing runs. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Tools for 16S rRNA Sequencing and Validation

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Mechanical & chemical lysis to release microbial DNA; includes purification steps to remove inhibitors [25]. | Critical for low-biomass samples; method can impact results [25]. |

| 16S rRNA PCR Primers | Amplify target hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4, V5-V8) for library construction [21]. | Primer choice influences which taxa are detected. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Reduces errors during PCR amplification, ensuring sequence accuracy [23]. | Essential for minimizing bias. |

| SILVA/Greengenes/RDP Databases | Curated reference databases for taxonomic classification of sequencing reads [22] [21]. | RDP is often used for species-level classification with SPINGO [22] [24]. |

| QIIME 2 / MOTHUR | User-friendly bioinformatics pipelines for processing raw sequencing data into taxonomic units [25] [22]. | Include extensive tutorials for non-bioinformaticians [25]. |

| SPINGO / SINTAX Classifier | Specialized algorithms for improving species-level classification from 16S data [22] [24]. | Recommended for full-length 16S sequences with RDP [22]. |

| Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) Tool | Genomic standard for definitive species identification (threshold ~95-96%) [18] [20]. | Used to validate 16S findings; tools include FastANI and Skani [20]. |

| Iclepertin | Iclepertin, CAS:1421936-85-7, MF:C20H18F6N2O5S, MW:512.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3,N-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazole-5-amine | 3,N-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazole-5-amine | 3,N-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazole-5-amine is a chemical building block for antimicrobial and materials science research. This product is for research use only and not for human use. |

Conceptual Framework: The Relationship Between 16S rRNA and Genomic Divergence

The core limitation of 16S rRNA for deep phylogeny is its evolutionary rigidity compared to the rest of the genome. The following diagram illustrates this conceptual problem.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What proportion of microbial diversity is represented by uncultured lineages, and why does it matter? Research indicates that a significant portion of microbial diversity lacks cultured representatives. One comprehensive genomic study found that lineages with no cultured representatives made up a substantial part of the Tree of Life, with the Candidate Phyla Radiation (CPR) alone constituting approximately 50% of the total bacterial diversity on the tree [26]. This matters because without cultures, our understanding of the physiology, metabolism, and ecological roles of these dominant organisms remains incomplete and reliant on predictions from genomic data.

FAQ 2: What cultivation methods are most effective for isolating previously uncultured aquatic bacteria? High-throughput dilution-to-extinction cultivation has proven highly successful. One recent large-scale initiative using this method with defined, low-nutrient media that mimic natural conditions yielded 627 axenic strains from 14 Central European lakes. On average, this approach resulted in 10 axenic strains per sample, with cultures representing up to 72% of the bacterial genera detected in the original environmental samples via metagenomics [3].

FAQ 3: My differential abundance analysis results change drastically with different normalizations. What is the issue and how can I resolve it? This is a common problem rooted in scale uncertainty. Normalization methods like Total Sum Scaling (TSS) implicitly assume that the total microbial load is constant across all samples. When this assumption is false, it can lead to both false positives and false negatives [27]. To resolve this, we recommend using scale models instead of a single normalization. The updated ALDEx2 software package allows for this approach, which incorporates uncertainty about the true biological scale (e.g., microbial load) into the model, dramatically improving the robustness of inferences [27].

FAQ 4: Where can I find authoritative information on prokaryotic nomenclature and taxonomy? The List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) is a comprehensive and freely available resource for this purpose. It provides curated information on the valid naming of prokaryotes according to the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (ICNP) [28].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Low Isolation Success in Cultivation Experiments

- Problem: Researchers are unable to isolate a significant fraction of the microbial community observed through sequencing.

Diagnosis: This is often because standard nutrient-rich media and incubation times favor fast-growing copiotrophs, while many environmental microbes are slow-growing oligotrophs with uncharacterized growth requirements [3] [29].

Solution:

- Imitate the Natural Environment: Use dilution-to-extinction cultivation with defined, low-nutrient media (e.g., containing 1.1-1.3 mg DOC per litre) that chemically mimics the natural habitat of the target microbes [3].

- Prolong Incubation: Allow plates or culture wells to incubate for extended periods (6-8 weeks or more), as many oligotrophs grow very slowly [3] [29].

- Apply Stimuli: Consider adding resuscitation-promoting factors (Rpf) or other signaling molecules from culture supernatants (e.g., from Micrococcus luteus) to stimulate the growth of dormant cells [29].

- Leverage Genomic Insights: Use metabolic information from Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) to design specific media that target the predicted requirements of uncultured lineages [29].

Challenge 2: Unreliable Differential Abundance Results Due to Compositional Data

- Problem: Statistical results for differential abundance analysis are highly sensitive to the choice of normalization method.

Diagnosis: Sequencing data is compositional (relative); conclusions about absolute abundance changes require knowledge of the system's scale (microbial load), which is not measured in standard sequencing [27].

Solution:

- Adopt Scale-Aware Models: Replace standard normalizations with a scale model analysis using tools like the updated ALDEx2 Bioconductor package. This treats the system scale as an uncertain variable, reducing false positives and negatives [27].

- Incorporate External Data: If possible, use external measurements of microbial load (e.g., from flow cytometry or qPCR) to inform the scale model and constrain the analysis [27].

- Use a Sensitivity Analysis: Employ Scale Simulation Random Variables (SSRVs) to test how different potential scale values affect your conclusions, making your results more transparent and robust [27].

Challenge 3: Resolving Deep Phylogenetic Relationships of Novel Lineages

- Problem: Placing novel, uncultured lineages on the Tree of Life is difficult, and deep evolutionary relationships lack statistical support.

Diagnosis: Single marker genes (like 16S rRNA) may not contain enough phylogenetic signal, and genome-based trees can show conflicting topologies (e.g., two-domain vs. three-domain of life) [26].

Solution:

- Use Concatenated Protein Markers: Infer phylogenies from a concatenated alignment of multiple, universally conserved ribosomal protein genes for increased resolution [26].

- Explore Public Resources: Use comprehensive tools like the OneZoom tree of life explorer to visualize the placement of your organisms of interest within the context of all sequenced diversity [30].

- Acknowledge Uncertainty: Be transparent about the lack of support for deep branches and avoid over-interpreting these relationships.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation

This protocol is adapted from a large-scale study that successfully cultivated abundant freshwater oligotrophs [3].

Principle: Greatly diluting an environmental inoculum to the point of statistically distributing single cells into individual wells prevents the overgrowth by fast-growing copiotrophs and allows the growth of slow-growing organisms.

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect water or soil samples from the environment of interest. For water, filter a large volume to concentrate cells.

- Media Preparation: Prepare defined, oligotrophic media. The table below outlines components from a successful study.

- Inoculation and Incubation: In a 96-deep-well plate, inoculate each well with a diluted sample containing approximately one cell per well. Incubate at an environmentally relevant temperature (e.g., 16°C) for 6-8 weeks without disturbance.

- Growth Screening: Monitor growth by measuring optical density or chlorophyll fluorescence over time.

- Purity Checking: Transfer positive cultures to new media and check for purity via Sanger sequencing of 16S rRNA gene amplicons.

- Long-term Maintenance: Maintain axenic cultures in fresh, low-nutrient media.

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| med2 / med3 media | Defined, low-carbon media mimicking natural freshwater conditions (1.1-1.3 mg DOC/L). Contains carbohydrates, organic acids, catalase, and vitamins [3]. | Used for general isolation of diverse oligotrophs like Planktophila and Fontibacterium [3]. |

| MM-med media | Defined medium with methanol and methylamine as sole carbon sources. Used for isolating methylotrophs [3]. | Enriched for Methylopumilus and Methylotenera [3]. |

| Resuscitation-Promoting Factor (Rpf) | A bacterial cytokine that stimulates the resuscitation of dormant cells from a viable but non-culturable state [29]. | The heat-labile component of Micrococcus luteus culture supernatant increased the diversity of cultured soil bacteria [29]. |

- Quantitative Results from a Recent Cultivation Study [3]:

| Metric | Result | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Total wells inoculated | 6,144 | 64 x 96-deep-well plates |

| Initial positive cultures | 1,201 | After initial incubation |

| Final axenic cultures | 627 | After purity checking and stabilization |

| Average viability | 12.6% | (Axenic cultures / Inoculated wells) * 100 |

| Genera represented | 72 | Including 15 of the 30 most abundant freshwater genera |

| Community coverage | Up to 72% | Genera in cultures vs. original sample (avg. 40%) |

Protocol 2: Scale Model-Based Differential Abundance Analysis with ALDEx2

This protocol addresses the problem of compositional data in sequencing experiments [27].

Principle: Instead of assuming a fixed scale (like TSS does), this method uses a Bayesian model to incorporate uncertainty about the true and unmeasured biological scale (e.g., total microbial load) of each sample, leading to more robust differential abundance estimates.

Workflow:

- Procedure:

- Install ALDEx2: Ensure you have the latest version of ALDEx2 from Bioconductor that supports scale models.

- Define a Scale Model: This model represents your prior belief about how the total microbial load might vary between sample groups. This can be:

- An Uninformed Model: A uniform distribution over a wide range of possible values.

- An Informed Model: Based on external data like flow cytometry or qPCR.

- A Sparsity Model: Assuming that very few taxa are changing in absolute abundance.

- Run the Analysis: Execute the

aldexfunction, specifying your scale model. The underlying algorithm will generate a posterior distribution of absolute abundances consistent with both your observed relative data and the defined scale model. - Interpret Results: The output will provide effect sizes and p-values that are more reliable because they are not contingent on a single, potentially incorrect, scale assumption.

Advanced Statistical & Bioinformatic Considerations

Handling Genome Sequence Uncertainty

Next-generation sequencing has inherent base-calling errors. Treating sequences as known without error can lead to overconfident conclusions in downstream phylogenetic or population genetic analyses [31].

- Solution Framework: The Sequence Uncertainty Propagation (SUP) framework provides a method to incorporate this uncertainty.

- Method: SUP uses a probabilistic matrix representation of sequences that incorporates base quality scores. It uses resampling to propagate this uncertainty through downstream analysis, giving a more realistic variance for estimates like clock rates or lineage assignments [31].

- Impact: One study showed that SARS-CoV-2 lineage designations were much less certain than typically reported when sequence uncertainty was considered [31].

Logical Workflow for Integrating Cultured and Unculturaed Data

The following diagram outlines a strategic workflow for combining cultivation-dependent and independent approaches to refine the Tree of Life and prokaryotic taxonomy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core conflict between the ICNP and modern microbial research? The International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (ICNP) requires that new species be grown in a lab and distributed as pure, viable cultures deposited in at least two international culture collections to be formally named [32] [33]. This conflicts with the microbial reality that an estimated ≥80% of archaeal and bacterial diversity is uncultivated, meaning the vast majority of prokaryotes cannot be formally named under the current ICNP rules [32] [4].

Q2: Why is it so difficult to cultivate most prokaryotes? Many prokaryotes, especially free-living oligotrophs in environments like freshwater and oceans, have oligotrophic lifestyles adapted to low nutrient concentrations. They often possess reduced genomes with multiple auxotrophies, creating dependencies on other microbes for essential nutrients [3]. Their slow growth and tendency to be outcompeted by fast-growing copiotrophs in lab settings make them notoriously difficult to isolate [3].

Q3: What are the practical consequences for research and communication? The inability to formally name most prokaryotes creates significant communication challenges. It leads to the use of unregulated placeholder names in literature, increasing the risk of errors and making it difficult to track microbial diversity, compare data across studies, and communicate findings effectively between scientists, clinicians, and the public [33] [34]. For example, clinically relevant organisms like some Chlamydia-related species cannot be validly named, potentially hindering disease tracking and scientific discourse [33].

Q4: What modern solutions have been developed to address this conflict? The SeqCode (Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes Described from Sequence Data) was established in 2022 as a parallel system that uses genome sequence data as the nomenclatural type for both cultivated and uncultivated prokaryotes [32] [33]. Meanwhile, advanced cultivation techniques like high-throughput dilution-to-extinction with defined media that mimic natural conditions are improving the cultivation of previously unculturable oligotrophs [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inability to Name a Novel, Unculturabled Prokaryote

Issue: Your research has identified a novel, phylogenetically distinct prokaryote via metagenomic sequencing, but all cultivation attempts have failed. You cannot formally name it under the ICNP.

Solution Pathway:

Step-by-Step Guide:

- Generate a High-Quality Genome Sequence: Use metagenomic assembly or single-cell genomics to obtain a Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MAG) or Single-Amplified Genome (SAG). The genome should be of high quality, as classified by standards that assess completeness, contamination, and the presence of marker genes [6].

- Evaluate Nomenclatural Options:

- Path A (Formal Nomenclature under SeqCode): Proceed to formally name the organism under the SeqCode. This provides a stable, formal name with priority. Register the name and the required genomic data in the SeqCode registry [33].

- Path B (Provisional ICNP Status): Use the provisional "Candidatus" category as per ICNP guidelines. Note that "Candidatus" has no formal standing in nomenclature and the name does not have priority if the organism is later cultivated [34].

- Publish a Description: For a formal SeqCode name, publish a protologue that includes the etymology of the name, the properties of the taxon inferred from genomic and environmental data, and the accession numbers for the deposited genome sequences [34].

Problem: Cultivation Failure of Abundant Environmental Microbes

Issue: Microbes that are highly abundant in environmental samples (e.g., lakes, soil) based on metagenomic data fail to grow on standard nutrient-rich laboratory media.

Solution Pathway & Experimental Protocol:

Detailed Methodology: High-Throughput Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation [3]

Media Design:

- Prepare defined artificial media with low nutrient concentrations that mimic the natural environment. For example, use media with ~1.1-1.3 mg Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) per liter for freshwater microbes [3].

- Include a mix of carbohydrates, organic acids, vitamins, and other organic compounds in µM concentrations.

- Consider specialized media; for example, using methanol and methylamine (MM-med) as sole carbon sources can help isolate methylotrophs [3].

Cultivation Process:

- Inoculate a large number of sterile media wells (e.g., in 96-deep-well plates) using a dilution-to-extinction approach, aiming for approximately one cell per well. This avoids competition from fast-growing copiotrophs.

- Incubate the plates for an extended period (e.g., 6-8 weeks) at a temperature representative of the source environment (e.g., 16°C for temperate lakes).

- Screen the wells for growth. Identify axenic cultures by sequencing 16S rRNA gene amplicons and ensure purity through several transfers.

Characterization:

- Sequence the genomes of the obtained strains.

- Compare them to Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) from the original sample to confirm their environmental relevance and abundance.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Nomenclatural Frameworks for Prokaryotes

| Feature | ICNP | SeqCode |

|---|---|---|

| Nomenclatural Type | Viable pure culture, deposited in at least two international culture collections [32] [33] | Genome sequence (from pure culture, single cell, or metagenome) [32] [33] |

| Coverage of Diversity | <0.5% of prokaryotic species [32] | All prokaryotes with a high-quality genome sequence [33] |

| Key Limitation | Excludes the vast uncultivated majority of prokaryotes [32] | Does not require a physical culture for naming [33] |

| Status of Names | Formal, with standing in nomenclature | Formal, with standing under the SeqCode; aims for future unification [33] [34] |

Table 2: Performance of Modern Methods for Accessing Uncultivated Prokaryotes

| Method | Key Output | Key Advantages | Key Limitations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) [6] | Genomic sequences binned from community sequencing | Provides extensive genomic data from complex communities; straightforward experimental procedure | MAGs can be chimeric; often lack 16S rRNA genes; difficult to associate mobile genetic elements with individual species |

| Single-Amplified Genomes (SAGs) [6] | Genomic sequences from physically isolated single cells | Provides strain-resolved genomes; excellent recovery of 16S rRNA genes; can link hosts to mobile elements | Technically challenging; lower genome completeness; potential for chimeric sequences or contamination |

| High-Throughput Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation [3] | Axenic cultures of previously uncultured taxa | Yields live cultures for physiological studies; allows isolation of slow-growing oligotrophs | Requires careful media design; incubation can take weeks; not all taxa are cultivable |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Research on Uncultivated Prokaryotes

| Item | Function/Benefit | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Low-Nutrient Media (e.g., med2/med3) [3] | Mimics natural substrate concentrations (e.g., 1.1-1.3 mg DOC/L) to cultivate oligotrophs without inhibition. | Isolation of abundant, yet previously uncultured, freshwater bacteria like Planktophila and Methylopumilus [3]. |

| C1 Compound Media (e.g., MM-med) [3] | Uses methanol/methylamine as sole carbon source to selectively enrich for methylotrophic bacteria. | Targeted isolation of methylotrophs such as Methylopumilus and Methylotenera from lake samples [3]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits for Environmental Samples | Efficiently lyses diverse microbial cells and yields high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA for sequencing. | Initial step for shotgun metagenomics to generate data for MAG assembly [6]. |

| Flow Cytometric Cell Sorter | Precisely isolates individual microbial cells from complex environmental communities for SAG generation. | Production of SAGs from marine bacteria in surface seawater [6]. |

| CheckM Software [6] | Assesses quality of MAGs/SAGs by estimating genome completeness and contamination using single-copy marker genes. | Quality control and binning refinement to select high-quality genomes for taxonomic proposal [6]. |

| Ercc1-xpf-IN-2 | Ercc1-xpf-IN-2, MF:C15H13Cl2NO3, MW:326.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ugt8-IN-1 | Ugt8-IN-1, MF:C20H22F6N4O4S, MW:528.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Tools for Discovery: Genomic and Cultivation-Based Approaches to Access the Uncultured

The study of prokaryotic diversity has long been constrained by a fundamental limitation: the inability to cultivate the vast majority of microorganisms in laboratory settings. This "microbial dark matter" represents an estimated over 90% of environmental microbes, leaving a substantial gap in our understanding of microbial taxonomy and ecosystem function [35]. Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) have emerged as a revolutionary culture-independent approach to address this challenge, enabling researchers to reconstruct individual microbial genomes directly from environmental samples [36].

The field of prokaryotic taxonomy currently faces significant challenges in formally describing uncultured organisms. The established International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (ICNP) requires physical specimen or culture deposition for valid species description, creating a taxonomic impasse for microorganisms that cannot be cultivated [37]. This has led to the proposal of DNA-based taxonomy approaches, which would permit DNA sequences as type material, potentially unlocking the formal classification of the uncultivated microbial majority [37]. MAGs serve as a crucial bridge in this paradigm shift, providing the genomic foundation needed to characterize these previously inaccessible lineages.

MAGs have dramatically expanded the known tree of life. Recent analyses reveal that while cultivated taxa represent only 9.73% of bacterial and 6.55% of archaeal diversity, MAGs contribute 48.54% and 57.05% respectively, highlighting their indispensable role in uncovering microbial diversity [35]. For researchers working with uncultured organisms, MAGs provide genomic context that enables more accurate phylogenetic placement and functional characterization, advancing the field of microbial taxonomy beyond the constraints of traditional culturing methods.

MAG Principles and Workflows

Theoretical Foundations

MAG reconstruction relies on several key biological and computational principles that enable the separation of mixed sequences into discrete genomes:

- Contig Co-abundance: Contigs from the same genome exhibit similar abundance profiles across multiple samples due to their shared genomic copy number [36]

- Sequence Composition: Contigs from the same genome share similar k-mer frequencies, GC content, and other sequence composition features that are phylogenetically conserved [36]

- Single-Copy Marker Genes: Essential, single-copy genes provide metrics for assessing genome completeness and contamination [38]

- Evolutionary Conservation: Taxonomic signals in genes and proteins enable phylogenetic placement of reconstructed genomes [37]

Standard MAG Generation Workflow

The process of generating MAGs follows a multi-stage workflow, with each step employing specialized tools and algorithms.

Workflow Diagram: MAG Generation and Quality Control

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

The initial wet lab phase is critical for MAG success. Sample collection should be tailored to research objectives, using sterile tools and DNA-free containers [35]. Immediate preservation at -80°C or nucleic acid preservation buffers is essential to maintain DNA integrity [35]. DNA extraction methods must be optimized for the specific sample type (soil, water, gut content) to maximize yield and representativeness.

Sequencing technology selection involves important trade-offs:

- Illumina short-reads: Provide high accuracy (Q30 > 94%) [39] and cost-effectiveness but struggle with repetitive regions [36]

- PacBio/Oxford Nanopore long-reads: Enable resolution of repetitive regions but historically had higher error rates [40]

- Hybrid approaches: Combine both technologies to leverage accuracy and contiguity [36]

Bioinformatics Processing

Quality Control employs tools like fastp to remove adapters, trim low-quality bases (typically Q20 threshold), and filter short reads [41]. For host-associated samples, Bowtie2 is used with reference genomes (e.g., hg38) to remove host contamination [41] [39].

Metagenome Assembly faces unique challenges compared to single-genome assembly, including uneven organism abundance and strain variation [40]. Common assemblers include:

- MEGAHIT: Optimized for large datasets with lower memory requirements [36]

- metaSPAdes: Provides robust error correction and iterative graph construction [36]

- Flye/Canu: Specialized for long-read assembly, resolving repetitive regions [36]

Genome Binning groups contigs into putative genomes using:

- Composition-based methods (MetaBAT, CONCOCT): Utilize tetranucleotide frequencies and GC content [36]

- Coverage-based methods (MaxBin): Leverage differential abundance across samples [36]

- Hybrid approaches: Combine multiple binning strategies for improved results [36]

Quality Standards and Assessment

MIMAG Standards and Quality Metrics

The Minimum Information about a Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MIMAG) standards provide a framework for quality assessment and reporting [38]. Quality evaluation focuses on three core metrics:

Table 1: MAG Quality Classification Standards Based on MIMAG

| Quality Tier | Completeness | Contamination | tRNA Genes | rRNA Genes | Suitable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Draft | >90% | <5% | ≥18 | ≥1 (5S, 16S, 23S) | Publication, database deposition, detailed functional analysis |

| Medium-Quality Draft | ≥50% | <10% | Not required | Not required | Comparative genomics, metabolic potential assessment |

| Low-Quality Draft | <50% | <10% | Not required | Not required | Presence/absence analysis, limited functional insights |

These standards are implemented in tools like CheckM, which uses single-copy marker genes to estimate completeness and contamination [38], and Bakta, which annotates features including rRNA and tRNA genes [38].

Automated Quality Assessment Pipelines

For high-throughput MAG analysis, automated pipelines like MAGqual provide standardized quality assessment [38]. Built in Snakemake, MAGqual integrates CheckM and Bakta to assign MIMAG-compliant quality categories and generate comprehensive reports [38]. This approach promotes reproducibility and standardization across studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MAG Research

| Category | Item/Software | Function/Purpose | Key Features/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Materials | Nucleic Acid Preservation Buffers (RNAlater, OMNIgene.GUT) | Stabilize DNA/RNA during sample storage/transport | Critical when immediate freezing to -80°C isn't possible [35] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Extract microbial DNA from complex matrices | Must be optimized for sample type (soil, gut, water) to ensure representative lysis [35] | |

| Sequencing Library Preparation Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries for Illumina, PacBio, or Nanopore platforms | Choice affects insert size, complexity, and sequencing efficiency [40] | |

| Computational Tools | CheckM | Assess MAG quality (completeness/contamination) | Uses single-copy marker genes; essential for MIMAG compliance [38] [36] |

| Bakta | Annotate MAG features (rRNA, tRNA genes) | Determines assembly quality per MIMAG standards [38] | |

| metaWRAP, Anvi'o | MAG refinement and visualization | Bin refinement, contamination removal, interactive exploration [36] | |

| GTDB-Tk | Taxonomic classification of MAGs | Standardized taxonomy based on Genome Taxonomy Database [42] | |

| Reference Databases | CheckM Database | Single-copy marker gene database | Required for quality assessment [38] |

| GTDB (Genome Taxonomy Database) | Reference taxonomy for prokaryotes | Genome-based taxonomy including MAGs [42] | |

| MAGdb | Repository of high-quality MAGs | Contains 99,672 HMAGs across clinical, environmental categories [42] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Pre-sequencing and Experimental Design

Q1: How can I optimize sampling strategies for MAG recovery from low-biomass environments?

- Solution: Increase filtration volumes for aquatic samples, use composite sampling for heterogeneous environments like soil, and employ biomass concentration techniques. Metadata collection (pH, temperature, nutrients) is crucial for contextual interpretation [35].

Q2: What sequencing depth is required for adequate MAG recovery?

- Solution: Requirements vary by community complexity:

- Low complexity communities (e.g., bioreactors): 5-10 Gb per sample

- Medium complexity (e.g., human gut): 20-30 Gb per sample

- High complexity (e.g., soil): 50+ Gb per sample [42]

- Correlations show MAG yield increases with sequencing depth, though completeness plateaus in complex samples [42].

Bioinformatics Processing Issues

Q3: My assembly is highly fragmented with low N50 values. How can I improve contiguity?

- Problem: Likely caused by low sequencing depth, high community complexity, or technology limitations.

- Solutions:

- Implement hybrid assembly combining Illumina short reads with PacBio or Nanopore long reads [36]

- Increase sequencing depth to cover low-abundance organisms

- Try multiple assemblers (metaSPAdes, MEGAHIT, Flye) and compare results [36]

- Use metaWRAP's reassembly module to target specific bins with optimized parameters [36]

Q4: How can I distinguish closely related strains during binning?

- Problem: Standard binning tools often collapse strains into single bins due to similar composition and coverage.

- Solutions:

Quality Assessment and Taxonomy

Q5: My MAG has high completeness (>95%) but also high contamination (>10%). Can it be salvaged?

- Problem: Likely represents a mixed bin of closely related organisms.

- Solutions:

- Use refinement tools like metaWRAP's bin_refinement module to separate contaminants [36]

- Apply taxonomic classifiers (GTDB-Tk) to identify inconsistent contigs [42]

- Manual inspection in Anvi'o to identify and remove divergent contigs based on multiple metrics [36]

- Consider the trade-off: Sometimes slightly lower completeness with significantly reduced contamination produces a more reliable MAG [38]

Q6: How should I handle MAGs that represent novel taxa with no close cultivated relatives?

- Problem: Common in environmental samples, creating taxonomic classification challenges.

- Solutions:

- Use genome-based taxonomy (GTDB-Tk) which incorporates MAGs [42]

- Calculate Average Amino Acid Identity (AAI) against known taxa to confirm novelty [37]

- Identify conserved marker genes for phylogenetic placement [37]

- Consider Candidatus status for highly novel, high-quality MAGs meeting ICNP requirements for uncultivated taxa [37]

Q7: My MAGs lack rRNA genes, making them non-compliant with high-quality MIMAG standards. What are my options?

- Problem: rRNA genes are often missing from MAGs due to assembly difficulties in repetitive regions.

- Solutions:

- Targeted reassembly of rRNA regions using specialized tools

- Hybrid assembly with long reads that better capture repetitive regions [36]

- Note limitations in publications and use "near-complete" category when appropriate [38]

- Extract rRNA reads from raw data and map to related taxa for phylogenetic placement [41]

Data Management and Publication

Q8: What are the minimum requirements for publishing MAGs in scientific journals?

- Solution:

- Adhere to MIMAG standards for quality reporting [38]

- Deposit in public repositories (NCBI, ENA) with complete metadata

- Provide taxonomic classifications using standard frameworks (GTDB) [42]

- Report completeness/contamination metrics from standardized tools (CheckM) [38]

- Contextualize novelty by comparing to existing databases (MAGdb contains 99,672 HMAGs) [42]

The field of MAG research continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future. Long-read sequencing technologies are improving in accuracy and affordability, enabling more complete genome reconstructions, particularly for repetitive regions like rRNA operons [36]. Integration of multi-omics data (metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics) with MAGs is providing insights into actual microbial activities beyond genetic potential [35]. Machine learning approaches are being developed to enhance binning accuracy and functional prediction [36].

From a taxonomic perspective, the ongoing development of DNA-based taxonomy frameworks promises to facilitate the formal description of uncultivated prokaryotes based on MAG data [37]. International databases like MAGdb are curating and standardizing MAG collections, creating valuable resources for comparative studies [42]. These advances will further establish MAGs as fundamental tools for exploring microbial dark matter and expanding our understanding of prokaryotic taxonomy.

For researchers navigating the challenges of uncultured organism taxonomy, MAGs provide a powerful approach to bridge the gap between molecular detection and formal classification. By adhering to established quality standards, employing appropriate troubleshooting strategies, and leveraging growing reference resources, scientists can reliably generate high-quality MAGs that advance our knowledge of microbial diversity and function across diverse ecosystems.

Prokaryotic taxonomy has long been constrained by reliance on cultured organisms, leaving the "uncultivated majority" of microbial diversity largely unexplored [44]. Single-Amplified Genomes (SAGs) represent a transformative approach that enables researchers to access genomic information from individual uncultured microbial cells, providing strain-resolved insights into complex ecosystems [45]. This technical support center addresses the key experimental challenges and provides troubleshooting guidance for implementing SAG methodologies to advance research on uncultured organisms.

Technical Guide: Core SAG Methodology

The following diagram illustrates the complete SAG generation workflow, from sample preparation to genome analysis:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for SAG Generation

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Single-cell isolation based on optical characteristics | BD influx Mariner; detection of SYTO-9 stain or autofluorescence [46] |

| SYTO-9 Green Fluorescent Stain | Nucleic acid staining for cell detection | Thermo Fisher Scientific; enables cell discrimination during sorting [46] |

| WGA-X / WGA-Y Kits | Whole genome amplification from single cells | Improved genome recovery, especially for high G+C content organisms [46] |

| RedoxSensor Green Probe | Measurement of cellular respiration rates | Thermo Fisher Scientific; requires customer pre-labeling before analysis [46] |

| Phi29 DNA Polymerase | Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) | Core enzyme for WGA; provides high processivity and fidelity [44] [14] |

| GlyTE Cryoprotectant | Sample preservation during storage/shipment | Maintains cell integrity; $100/10mL [46] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Low Genome Completeness

Problem: SAGs show less than 50% completeness, limiting downstream analysis.

Solutions:

- Utilize Improved WGA Protocols: Implement WGA-X or WGA-Y methods that significantly enhance average genome recovery from single cells, particularly for challenging templates with high G+C content [46].

- Apply Cleaning and Co-assembly (ccSAG): Integrate multiple closely related SAGs (ANI >95%) through cross-reference mapping and de novo co-assembly. Research demonstrates this achieves >96.6% completeness with <1.25% contamination [14].

- Optimize Cell Lysis: Employ controlled freeze-thaw cycles (2 cycles) followed by KOH treatment to ensure complete lysis while preserving DNA integrity [46].

Contamination Issues

Problem: Non-target sequences contaminate SAG assemblies, compromising data quality.

Solutions:

- Implement SAG-QC Pipeline: Use this specialized tool to exclude contaminant sequences by comparing k-mer compositions with "no template control" sequences run alongside experimental samples [47].

- Establish Cleanroom Procedures: Perform cell sorting and DNA amplification in cleanroom environments with decontaminated consumables to minimize exogenous DNA introduction [46] [44].

- Include Comprehensive Controls: Reserve multiple wells on each 384-well plate as negative controls during cell sorting to detect potential contamination sources [46].

Chimeric Sequence Artifacts

Problem: MDA amplification generates chimeric molecules linking non-contiguous genomic regions.

Solutions:

- Apply Cross-Reference Mapping: Identify potentially chimeric reads by mapping each SAG read to multiple raw contigs from the same phylogenetic group, then split and reclassify these fragments [14].

- Use Specialized Assemblers: Employ single-cell-specific assembly tools like SPAdes that account for uneven coverage depth and can handle chimeric artifacts [46] [44].

- Validate with Benchmark Cultures: Establish expected error rates using mock communities of known strains; benchmark studies show approximately 1 misassembly per Mb following proper cleanup [44].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of SAGs over metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) for strain-level analysis?

SAGs provide cellular-level resolution that captures individual genomic content, including mobile genetic elements (MGEs) and strain-specific variations that are often obscured in MAGs, which represent population consensus genomes [45]. SAGs also recover nearly complete rRNA genes (94.8% of fecal SAGs contain 16S rRNA) whereas MAGs largely lack these phylogenetically critical markers (only 0.0069% contain rRNA genes) [45].

Q2: What sample preservation methods are critical for SAG success?

Immediate cryopreservation using specialized cryoprotectants like glyTE is essential. Studies indicate that Gram-negative bacteria are particularly susceptible to aerobic sample processing, solvent-induced lysis during preservation, and freezing-induced stress, which significantly impacts SAG recovery rates [45] [46].

Q3: How many SAGs are typically needed for robust genome reconstruction?

Empirical results indicate that co-assembly of 5-6 SAGs optimizes genome completeness while minimizing chimeric accumulation. Integration of fewer than 5 SAGs may leave genomic gaps, while exceeding 6 SAGs can degrade assembly quality through accumulation of incorrect sequences [14].

Q4: What quality standards should be applied to SAG assemblies?

The Genomic Standards Consortium recommends using the MISAG (Minimum Information about a Single Amplified Genome) standard. For medium-quality drafts, aim for ≥50% completeness and <10% contamination; high-quality drafts should exceed >90% completeness with <5% contamination [44].

Q5: How can we validate host range findings for mobile genetic elements discovered in SAGs?

SAGs enable precise linking of MGEs to their microbial hosts at the cellular level. For example, research using 17,202 human oral and gut SAGs identified broad-host-range plasmids and phages carrying antibiotic resistance genes that were not detected in MAGs from the same samples [45]. Experimental validation can include PCR amplification across MGE-host junctions or functional assays.

Advanced Applications in Microbial Ecology

Resolving Strain Variation and Mobile Genetic Elements

The application of SAG technology enables unprecedented resolution of microbial strain variation and mobile genetic element dynamics:

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Performance Metrics: SAGs vs. MAGs

| Parameter | Single-Amplified Genomes (SAGs) | Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) |

|---|---|---|

| Strain Resolution | Individual cell genomic content [45] | Population consensus, obscures strain variation [45] |

| rRNA Gene Recovery | 94.8% contain 16S rRNA genes [45] | Nearly complete lack (0.0069%) of rRNA genes [45] |

| Mobile Genetic Elements | Directly linked to host genomes [45] | Limited detection (1-29% for plasmids) [45] |

| Completeness Range | Variable (often 50-90% for medium-high quality) [44] | Generally higher completeness [48] |

| Contamination Control | Critical issue requiring specialized tools [47] | Less susceptible to single-cell contaminants |

| Experimental Requirements | FACS, cleanrooms, specialized amplification [46] | Extensive sequencing, computational resources [48] |

Single-Amplified Genome technology provides an indispensable toolkit for advancing prokaryotic taxonomy beyond the limitations of cultured organisms. By implementing the troubleshooting guidelines, quality control measures, and experimental protocols outlined in this technical support center, researchers can reliably generate high-quality SAGs to explore previously inaccessible dimensions of microbial diversity, function, and evolution. The strain-level resolution offered by SAGs enables precise mapping of mobile genetic elements, antibiotic resistance genes, and functional adaptation across complex ecosystems.

FAQs: Addressing Common Challenges in Cultivation

Q1: Why should I use an ichip instead of standard petri dishes for isolating environmental microbes?

Standard petri dishes often fail to cultivate the majority of environmental microbes because they cannot replicate the natural chemical environment and growth factors present in a microbe's original habitat. The ichip addresses this by serving as a high-throughput platform of miniature diffusion chambers. When incubated in situ, it allows natural nutrients and signaling molecules to diffuse through semi-permeable membranes, creating a more natural growth environment. Research shows that ichips can achieve microbial recovery rates of 40-50% from seawater and soil samples, a significant increase over the approximately 5% recovery rate typical of standard petri dishes [49] [50]. Furthermore, species grown in ichips demonstrate significantly higher phylogenetic novelty compared to those from petri dishes [49].

Q2: My dilution-to-extinction cultures are not growing. What could be the issue?

Dilution-to-extinction cultivation is highly effective for isolating slow-growing oligotrophs by reducing competition from fast-growing species. Failure often stems from improper media composition or cell density. Key considerations include:

- Media Composition: Use diluted, defined media that mimic the natural environmental conditions, particularly low nutrient concentrations (e.g., 1.1-1.3 mg DOC per litre). For freshwater microbes, supplementing with catalase, vitamins, and a mix of carbohydrates or specific carbon sources like methanol can be crucial [3].

- Inoculation Density: The goal is to inoculate at approximately one cell per well [3]. Confirming your initial cell count and dilution factor is essential to ensure wells receive a cell while minimizing co-culture.

- Incubation Time: These cultures often require extended incubation (6-8 weeks or more) as many target oligotrophs grow very slowly [3] [51]. Patience is key.

Q3: How can I improve the success of cultivating microorganisms from extreme environments, like hot springs?

Cultivating thermo-tolerant or other extremophilic organisms often requires customizing techniques to maintain in situ conditions.

- Device Modification: When using an ichip in a hot spring, one study successfully replaced agar with the more heat-stable gellan gum as a gelling agent [52].

- Temperature Control: Ensure your in situ incubation or laboratory setup accurately maintains the environmental temperature. For example, a study of Tengchong hot spring incubated modified ichips at 85°C [52].

- Multiple Methods: No single method captures all diversity. A study on High Arctic lake sediment found that using a suite of methods—including diffusion chambers, traps, and dilution-to-extinction—was necessary to access the broadest spectrum of microbial taxa [51].

Q4: After successful cultivation in a diffusion chamber, how do I domesticate the organism for lab growth?

Domestication, or transitioning a microbe from an in situ device to a laboratory plate, can be challenging. A common strategy is sequential sub-culturing. After initial growth in the device, extract the microcolony and streak it onto a rich laboratory medium (e.g., R2A Agar). If this fails, one effective approach is to repeat the process: perform a second round of in situ cultivation within the diffusion chamber or ichip. Research indicates that this repeated in situ passaging can significantly improve domestication success, with one study reporting that 40% of colonies domesticated after a second round [50].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Problems and Solutions in Advanced Cultivation

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No growth in diffusion chambers/ichips | Membranes are clogged, preventing nutrient diffusion. | Use membranes with an appropriate pore size (e.g., 0.03 μm) and ensure devices are not buried in sediment that could block diffusion [49] [52]. |

| The in situ environment does not match the original sample habitat. | Incubate the device as close as possible to the exact location and conditions (e.g., temperature, oxygen levels) where the sample was collected [52] [51]. | |

| Contaminated cultures | The device was improperly sealed, allowing environmental cells to enter. | Verify the seal integrity of the device. Tests have shown that well-sealed chambers prevent external microbial invasion [49]. |

| Reagents or labware are contaminated. | Use sterile, DNA-grade water and autoclave all components. Include a non-inoculated control device to check for contamination [49] [52]. | |

| Only fast-growing species are isolated | Competition from fast-growers is outcompeting slow-growers. | Employ dilution-to-extinction to physically separate cells and reduce competition [3]. Use nutrient-poor media to selectively favor oligotrophs [3]. |

| Incomplete or chimeric genome assemblies from SAGs | Whole-genome amplification (WGA) bias and contamination. | Use multiple displacement amplification (MDA) methods with caution. Co-assembly of multiple SAGs and chimera sequence cleaning can help overcome these issues [6] [48]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Microbial Recovery and Novelty Across Techniques

| Technique | Typical Microbial Recovery Rate | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Petri Dish | ~5% [49] [50] | Simple, low-cost, and high-throughput. | Heavy bias toward fast-growing copiotrophs; misses the vast majority of microbial diversity. |

| Diffusion Chamber/Ichip | 40-50% (soil/seawater) [49] | Accesses novel and abundant microbial taxa; provides a more natural chemical environment. | Technically challenging; requires domestication for lab growth; device assembly can be laborious. |

| Dilution-to-Extinction | Varies; one study reported an average of 12.6% viability for freshwater lakes [3] | Excellent for isolating slow-growing oligotrophs and reducing competition. | Requires careful media design; extended incubation times (weeks to months). |

| Single-Cell Genomics (SAGs) | N/A (genome completeness is the metric) | Provides strain-resolved genomes; excellent recovery of 16S rRNA and mobile genetic elements [6]. | Technically demanding; genome completeness is often low; requires specialized equipment [6] [48]. |

| Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) | N/A (genome completeness/contamination are metrics) | Can generate multiple genomes from a community without cultivation; straightforward experimental process [6]. | Can produce chimeric genomes; often misses 16S rRNA genes and plasmids; struggles in highly diverse ecosystems [6]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cultivation Using the Ichip

This protocol is adapted from methods used to cultivate soil and seawater bacteria, as well as thermo-tolerant microbes from hot springs [49] [52].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Polyoxymethylene (Delrin) plates: Hydrophobic plastic used to fabricate the central, top, and bottom plates of the ichip.

- Semi-permeable membranes (0.03 μm pore size): Allow diffusion of nutrients and growth factors while containing the target cells.