Resolving Low Resolution in 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: Strategies for Species-Level Microbial Identification

This article addresses the critical challenge of low taxonomic resolution in 16S rRNA gene sequencing, a key limitation for researchers and drug development professionals requiring species-level microbial identification.

Resolving Low Resolution in 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: Strategies for Species-Level Microbial Identification

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of low taxonomic resolution in 16S rRNA gene sequencing, a key limitation for researchers and drug development professionals requiring species-level microbial identification. We explore the fundamental causes of this resolution gap, from inherent genetic constraints to methodological biases. The content provides a comprehensive comparison of modern sequencing platforms (Illumina, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) and bioinformatic algorithms (OTU vs. ASV), alongside practical optimization strategies for primer selection, library preparation, and database choice. Through validation frameworks and comparative analyses, we synthesize a clear pathway for enhancing resolution in microbiome studies, enabling more precise biomarker discovery and contamination investigation in pharmaceutical and clinical settings.

The Fundamental Limits of 16S rRNA Sequencing: Why Species-Level Resolution is Elusive

A core challenge in 16S rRNA gene sequencing is its inherent taxonomic resolution ceiling. This concept refers to the fundamental limit of the 16S rRNA gene to distinguish between closely related bacterial taxa due to its sequence conservation. Unlike whole-genome approaches, which use thousands of genes, 16S analysis relies on variations within a single gene, approximately 1,550 base pairs long, containing nine hypervariable regions [1] [2]. This limitation means that even under ideal conditions, the gene may not provide sufficient phylogenetic signal for reliable species- or strain-level identification for many taxa, impacting the accuracy of microbial community analyses in both research and clinical diagnostics.

FAQs: Understanding the 16S Resolution Ceiling

1. What is the fundamental reason 16S rRNA gene sequencing cannot always distinguish between species?

The 16S rRNA gene is a highly conserved marker essential for basic cellular function, which limits the degree of sequence variation that can accumulate without compromising cell viability [2]. While the gene contains variable regions, the evolutionary rate is not sufficient to create distinguishing sequences between all closely related species. Some species share identical or nearly identical 16S gene sequences despite having different genomic content and phenotypes. Furthermore, the existence of multiple, slightly different copies of the 16S gene within a single genome (microheterogeneity) can further complicate precise taxonomic assignment [2].

2. My analysis is stuck at the genus level. Is this a bioinformatics problem or a genetic limitation?

It is often a combination of both, but the genetic limitation is the root cause. The amount of sequence variation in the 16S gene between different species within the same genus is frequently too small for reliable discrimination [3]. Bioinformatics tools struggle with this limited signal. For example, a 2025 study using the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) found that while genus-level resolution typically requires 16S sequences to be clustered at 92-96% identity, species-level resolution requires a much stricter 99% identity threshold [3]. However, applying such a stringent threshold universally is not feasible as it leads to over-splitting of other taxa. This confirms that the genetic information itself is often insufficient for consistent species-level classification.

3. Which variable regions of the 16S gene provide the best taxonomic resolution?

No single variable region is optimal for all bacterial groups. The discriminatory power of each region is taxon-dependent [4]. The table below summarizes findings from an in silico analysis of 16 plant-related microbial genera, which compared the performance of different variable regions against whole-genome data as a benchmark [4].

Table 1: Performance of 16S rRNA Variable Regions for Taxonomic Resolution

| Targeted Region(s) | Performance Summary | Notes and Example Genera |

|---|---|---|

| V1-V3 | Demonstrated the best resolution for 8 out of 16 analyzed genera. | Considered a more suitable option than V3-V4 for many plant-related genera [4]. |

| V6-V9 | Showed the best resolving power for 4 out of 16 genera. | A good alternative for certain taxa [4]. |

| V3-V4 | The most widely used "gold standard," but only showed the highest resolution for 1 genus (Actinoplanes). | Its common use does not mean it is the most discriminative for all studies [4]. |

| V4 Alone | Could not successfully distinguish genomes in any of the 16 genera analyzed. | Lacks sufficient variable sites for reliable genus or species-level resolution [4]. |

| Full-Length 16S | Overall best performance across the majority of genera. | Provides the most comprehensive phylogenetic signal by incorporating all variable regions [5] [4]. |

4. Are newer sequencing technologies able to overcome this resolution ceiling?

Long-read sequencing technologies, such as PacBio Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing, mitigate but do not fully overcome the inherent genetic limitation. By sequencing the full-length 16S rRNA gene (~1,500 bp), they capture all variable regions, providing the maximum possible resolution from the 16S gene itself. Studies show this approach significantly improves species-level classification rates compared to short-read sequencing of partial regions [5] [6]. For instance, one study reported a species-level assignment rate of 74.14% for PacBio (full-length) versus 55.23% for Illumina (V3-V4) in human microbiome samples [5]. The emerging method of sequencing the entire 16S-ITS-23S rRNA operon (~4,500 bp) offers even higher resolution, potentially differentiating between strains, but it still relies on a limited genetic locus and is subject to its own technical challenges [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Low Resolution in Your Data

Problem: Inability to Resolve Taxonomy Beyond Genus Level

Symptoms:

- Taxonomic classification outputs are consistently truncated at the genus rank.

- Closely related species (e.g., within the Streptococcus or Escherichia/Shigella groups) are reported as a single, ambiguous unit.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Confirm the Limitation: First, check if your isolates or dominant taxa belong to known "difficult" groups where 16S is known to be poorly discriminative. Consult literature and genomic databases.

- Optimize Your Wet-Lab Protocol:

- Switch to Full-Length 16S Sequencing: If possible, move from short-read (e.g., Illumina MiSeq of V3-V4) to long-read sequencing (Pacbio HiFi) of the entire 16S gene [5] [6].

- Target a More Informative Region: If full-length sequencing is not feasible, research the most discriminative variable region for your bacterial group of interest. For many genera, the V1-V3 region may be superior to the commonly used V3-V4 region [4].

- Optimize Your Bioinformatics Pipeline:

- Evaluate Clustering/Denoising Methods: Different algorithms have strengths and weaknesses. A 2025 benchmarking study found that ASV (Amplicon Sequence Variant) methods like DADA2 can suffer from over-splitting (creating multiple ASVs from one true biological sequence), while OTU methods like UPARSE can over-merge distinct sequences. Test different algorithms on mock community data to see which performs best for your needs [8].

- Use an Appropriate Database: Ensure you are using a modern, curated reference database like the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB). Be aware that even curated databases can have significant annotation error rates (estimated at ~17% in one study), which can propagate into your results [3] [9].

Problem: Inconsistent or Unreliable Species-Level Assignments

Symptoms:

- The same sequence variant is assigned to different species in separate runs or using different databases.

- Low bootstrap support or confidence scores for species-level assignments.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Use a Higher-Resolution Genetic Marker: When species-level identification is critical, transition to a method that is not limited by the 16S ceiling.

- 16S-ITS-23S Operon Sequencing: This approach uses a much longer and more variable genetic marker. A 2025 study demonstrated that using the Minimap2 classifier with the GROND database on RRN operon data consistently provided accurate species-level classification [7].

- Shotgun Metagenomics: This culture-independent method sequences all the DNA in a sample, allowing for classification based on many genes beyond the 16S rRNA, providing strain-level resolution and functional insights.

- Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS): For isolated colonies, WGS is the gold standard for definitive species and strain identification.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Improved Resolution

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| PacBio Sequel II System | Enables highly accurate (HiFi) long-read sequencing of full-length 16S rRNA gene or the entire 16S-ITS-23S operon. | Higher cost per sample compared to Illumina; requires higher DNA input. Optimal for maximum 16S resolution [5] [7]. |

| GROND Database | A curated reference database designed for classifying 16S-ITS-23S rRNA operon sequences. | Specifically improves species-level resolution when used with a suitable classifier like Minimap2 [7]. |

| Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) | A modern genome-based taxonomy database that provides a phylogenetic framework for 16S sequences. | Provides a more consistent and standardized taxonomy compared to older, phenotype-based systems [3]. |

| DADA2 Algorithm | A denoising tool that infers exact Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) from sequencing data. | Reduces sequencing error noise but may over-split ASVs from a single genome; best for high-resolution studies of fine-scale variation [8]. |

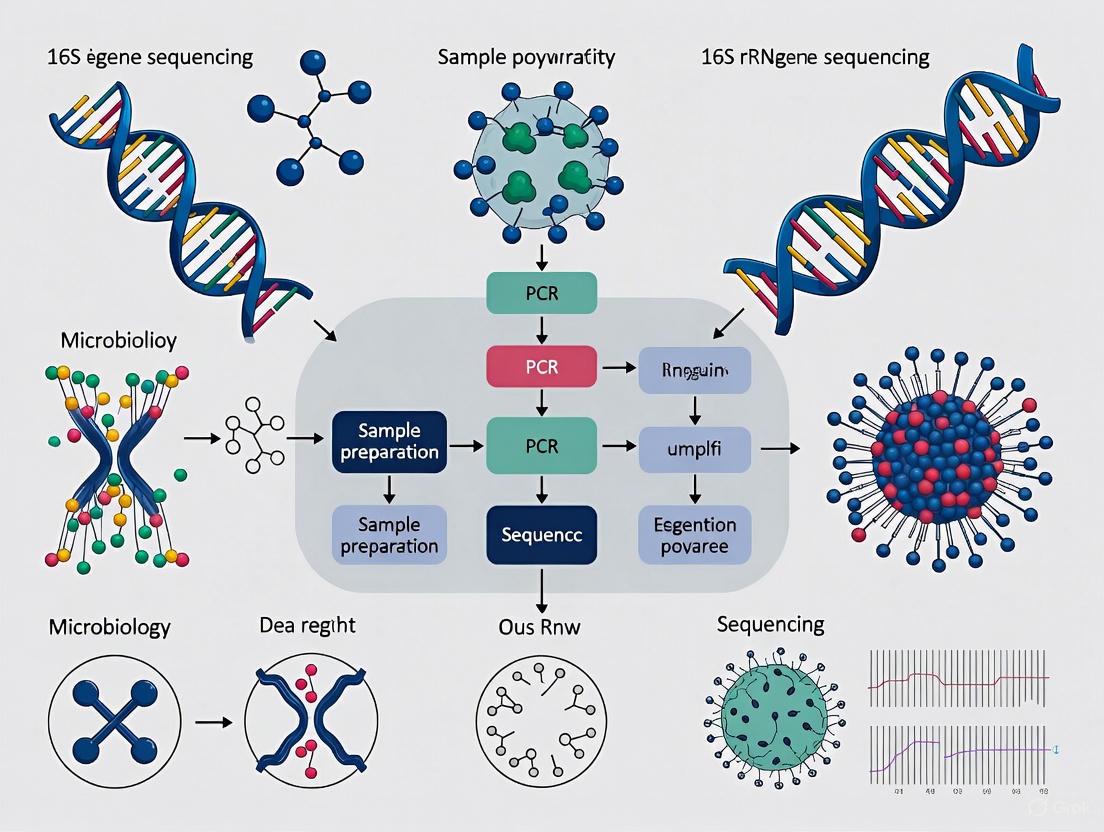

Experimental Workflow: Comparing Short-Read vs. Long-Read 16S Sequencing

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow to compare the taxonomic resolution achieved by short-read (partial 16S) and long-read (full-length 16S or RRN operon) sequencing approaches.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common sources of error in 16S rRNA gene sequencing? The primary sources of error include PCR artifacts (such as chimeras and polymerase errors), sequencing platform errors, and bioinformatic processing artifacts. These errors can significantly inflate diversity estimates and lead to the detection of spurious taxa that don't exist in the original sample [10] [11] [12].

2. How much can errors inflate apparent microbial diversity? Without proper error correction, artifacts can dramatically increase perceived diversity. One study found that simply reducing PCR cycles from 35 to 15 with a reconditioning step decreased unique sequence variants from 76% to 48%, while estimated total sequence richness dropped from 3,881 to 1,633 sequences [11]. Spurious taxa can account for approximately 50% (mock communities) to 80% (gnotobiotic mice) of reported taxa when using singleton removal alone [12].

3. What is the difference between OTU and ASV approaches in handling errors? OTU clustering at 97% similarity helps overcome some sequencing errors but can over-merge biologically distinct sequences. ASV methods (DADA2, Deblur, UNOISE3) attempt to distinguish true biological variation from errors using statistical models. ASV approaches generally yield lower rates of spurious taxa but can over-split sequences from the same strain [13].

4. How effective are chimera detection tools? Chimera detection effectiveness varies substantially. In one evaluation, Chimera Slayer detected >87% of chimeras with at least 4% divergence between parent sequences, while other tools required >13% divergence for similar sensitivity. Proper chimera checking can reduce chimera rates from 8% in raw data to 1% after processing [10] [14].

5. Can sequencing technology choice affect error rates? Yes, different platforms have characteristic error profiles. Traditional Sanger sequencing offers high accuracy but low throughput. Illumina platforms primarily exhibit substitution errors, while earlier Nanopore technologies had higher indel rates. Newer Nanopore R10 chemistry with duplex base calling achieves Q30 (>99.9% accuracy), improving species-level identification [13] [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inflated Diversity Estimates (Spurious Taxa)

Symptoms:

- Higher-than-expected richness estimates, especially in well-characterized communities

- Many low-abundance taxa (rare biosphere)

- Poor reproducibility between technical replicates

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Table 1: Comparison of Spurious Taxon Rates with Different Filtering Approaches

| Filtering Method | Mock Communities | Gnotobiotic Mice | Human Fecal Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singleton removal (OTU) | ~50% spurious taxa | ~80% spurious taxa | High variation (38% higher) |

| Relative abundance >0.25% (OTU) | Marked reduction | Marked reduction | Improved reproducibility |

| ASV-based approaches | Lower spurious taxa | Lower spurious taxa | Dependent on region & barcoding |

Apply abundance filtering: Implement a relative abundance threshold of 0.25% to effectively reduce spurious taxa while retaining true biological signals [12].

Optimize bioinformatic pipeline:

- For OTU-based approaches: Use closed-reference clustering when possible

- For ASV-based approaches: Select algorithms based on your sample type (DADA2 and UPARSE show closest resemblance to intended communities) [13]

Validate with mock communities: Include defined mock communities in your sequencing runs to quantify spurious taxon rates specific to your workflow [12].

Problem: PCR Artifacts and Chimeras

Symptoms:

- Detection of novel taxa that don't match expected biology

- Poor alignment with reference databases

- Inconsistent community profiles between replicates

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Table 2: PCR Artifact Rates Under Different Amplification Conditions

| PCR Condition | Cycle Number | Chimera Rate | Unique Sequences | Estimated Richness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | 35 cycles | 13% | 76% | 3,881 |

| Modified (+ reconditioning) | 15 + 3 cycles | 3% | 48% | 1,633 |

Modify PCR protocol:

- Reduce amplification cycles (15-20 instead of 30-35)

- Include reconditioning PCR step (3 additional cycles in fresh reaction mixture)

- Use high-fidelity polymerases with proofreading capability [11]

Implement robust chimera detection:

- Use Chimera Slayer for sensitive detection of chimeras between closely related sequences

- Combine multiple detection algorithms for comprehensive coverage

- Remember that chimera formation is reproducible across independent amplifications [14]

Cluster sequences appropriately: Report diversity estimates at 99% similarity to account for Taq polymerase errors while maintaining biological resolution [11].

Problem: Sequencing Errors and Platform-Specific Issues

Symptoms:

- Nucleotide substitutions or indels in consensus sequences

- Homopolymer miscalls

- Quality score deterioration in specific sequence regions

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Apply quality filtering:

Implement denoising algorithms:

- For Illumina data: Consider DADA2 or Deblur for error correction

- For pyrosequencing data: PyroNoise provides optimal error reduction but requires computational resources [10]

Utilize platform-specific solutions:

- For Nanopore: Use R10.3 or R10.4.1 flow cells with duplex base calling

- For Illumina: Consider read merging approaches and quality-aware trimming [15]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Modified Low-Error PCR Amplification

Purpose: To minimize PCR artifacts while maintaining representative amplification of community DNA [11].

Reagents:

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase with proofreading capability

- Molecular grade water

- Purified template DNA

- Target-specific primers with appropriate barcodes

Procedure:

- Set up first-round PCR with:

- Template DNA: 1-10 ng

- Primers: 0.2-0.5 μM each

- PCR components according to polymerase manufacturer

- Cycle conditions: 15 cycles of standard amplification

Perform reconditioning PCR:

- Transfer 1-5 μL of first PCR product to fresh reaction mixture

- Amplify for 3 additional cycles

Clean up PCR product using magnetic beads or columns

- Quantify using fluorometric methods (Qubit) rather than UV spectrophotometry

- Proceed to library preparation and sequencing

Validation: Include mock community controls and extraction blanks in each run.

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Chimera Detection Workflow

Purpose: To identify and remove chimeric sequences with maximum sensitivity [14].

Procedure:

- Perform initial quality filtering of raw sequences

- Run multiple chimera detection algorithms in parallel:

- Chimera Slayer (for sensitive detection of closely related chimeras)

- UCHIME (included in USEARCH/VSEARCH)

- Reference-based checking against curated database

Use consensus approach:

- Flag sequences identified as chimeric by any tool

- Manually inspect borderline cases using alignment visualization

For persistent chimera issues:

- Re-amplify with modified PCR protocol (fewer cycles)

- Consider alternative primer sets targeting different variable regions

- Implement duplex sequencing for ultra-high accuracy

Experimental Workflow and Relationships

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Error-Reduced 16S Sequencing

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Error Reduction Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| High-fidelity DNA polymerase | PCR amplification | Reduces Taq polymerase errors (∼3.3×10â»âµ errors/nt/duplication) |

| Magnetic bead cleanup kits | Purification | Removes primer dimers, reduces adapter contamination |

| ZymoBIOMICS DNA Standard | Mock community control | Quantifies spurious taxon rates in specific workflow |

| 16S Barcoding Kit (ONT) | Library preparation | Enables full-length 16S sequencing for improved resolution |

| Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Kit | DNA extraction | Minimizes inhibitor carryover that affects PCR |

| iQ-Check Free DNA Removal | Contaminant removal | Eliminates environmental DNA contamination |

| SequalPrep Normalization Plate | Library normalization | Improves sequencing balance, reduces bias |

A guide to navigating the choice that defines modern 16S rRNA sequencing analysis.

A core challenge in 16S rRNA gene sequencing research is the accurate translation of raw sequencing data into a true representation of a microbial community. The bioinformatic methods used to group sequences into analytical units profoundly influence the resolution—the level of taxonomic detail—you can achieve. The central methodological choice today is between traditional Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) clustering and the newer Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) denoising approaches. This guide, framed within the context of resolving low resolution, provides troubleshooting and FAQs to help you select and optimize the right method for your research, ensuring your conclusions are built on a robust analytical foundation.

FAQ: Core Concepts and Definitions

What are OTUs and ASVs, and how do they fundamentally differ?

Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) are clusters of sequencing reads grouped based on a predefined similarity threshold, traditionally 97% [16]. This method assumes that sequences differing by 3% or less likely belong to the same bacterial species. Clustering is designed to absorb minor sequencing errors into larger groups.

Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) are unique, error-corrected sequences that represent exact biological sequences. ASV methods, such as DADA2, use statistical models to distinguish true biological variation from sequencing errors, providing single-nucleotide resolution without applying an arbitrary clustering threshold [16].

The table below summarizes their key characteristics:

| Feature | OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit) | ASV (Amplicon Sequence Variant) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Cluster of sequences with a similarity threshold (e.g., 97%) [16] | Exact, error-corrected sequence variant [16] |

| Resolution | Lower (cluster-level) | Higher (single-nucleotide) [16] |

| Error Handling | Errors can be absorbed into clusters during greedy clustering or de novo methods [13] | Uses a denoising algorithm to model and remove errors [16] |

| Reproducibility | Can vary between studies and clustering parameters [16] | Highly reproducible across studies, as they represent exact sequences [16] |

| Computational Cost | Generally less computationally demanding [16] | Higher due to the complexity of denoising algorithms [16] |

Why is the choice between OTUs and ASVs critical for resolving low resolution in my data?

The choice is critical because it directly determines your ability to distinguish between closely related microbial species or strains. OTU clustering, by its design, can obscure fine-scale biological variation by grouping distinct but similar sequences together. This can lead to an underrepresentation of true diversity and a loss of taxonomic resolution. In contrast, ASVs can detect single-nucleotide differences, offering the potential to resolve strain-level variation and provide a more precise and accurate picture of the community structure [16]. This higher resolution is often essential for linking specific microbial lineages to host phenotypes or environmental gradients.

Which method provides a more accurate representation of a known microbial community?

Studies using mock microbial communities of known composition have demonstrated that ASV-based methods generally provide superior accuracy. For instance, one study found that DADA2, an ASV algorithm, produced a more accurate representation of a dairy-associated mock community compared to OTU-based methods like QIIME 1 (UCLUST) [17].

However, a more recent and comprehensive benchmarking study using a complex mock community of 227 strains revealed nuances: while ASV algorithms like DADA2 had consistent output, they sometimes suffered from "over-splitting" (generating multiple ASVs from a single strain). Conversely, OTU algorithms like UPARSE achieved clusters with lower error rates but with more "over-merging" (grouping distinct strains together) [13]. This suggests that the optimal choice can depend on the specific community and the trade-off your study is willing to make between false positives and false negatives.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Scenarios

Problem: My analysis is missing expected strain-level variation.

- Potential Cause: You are using an OTU-based approach with a 97% identity threshold, which is too lenient to capture strain-level differences.

- Solution: Switch to an ASV-based pipeline (e.g., DADA2, Deblur). ASVs are defined by single-nucleotide differences, making them ideal for detecting fine-scale variation [16]. If you must use OTUs, consider experimenting with a higher identity threshold (e.g., 99%), though this does not offer the same reproducibility or resolution as ASVs [18].

Problem: My diversity metrics (like richness) are inflated and do not match expectations.

- Potential Cause: OTU-based methods, particularly de novo clustering, are known to overestimate microbial richness due to the inclusion of sequencing errors as unique taxa [18] [13].

- Solution:

- Transition to an ASV pipeline. Denoising methods correct sequencing errors, leading to more accurate and typically lower estimates of true richness [18].

- If using OTUs, ensure rigorous quality filtering and chimera removal before clustering. Using a reference-based clustering approach can also help reduce inflation compared to de novo clustering [17].

Problem: I need to compare my new data with legacy datasets that used OTUs.

- Potential Cause: ASVs and OTUs are not directly comparable due to their different definitions, creating a challenge for longitudinal or meta-analyses.

- Solution: For the most robust and forward-compatible science, the best practice is to re-process raw sequence data from legacy studies through a standardized ASV pipeline. If this is not feasible, you can process your new data using both methods to facilitate comparison with the old dataset, acknowledging the inherent limitations [16].

Experimental Protocols: From Data to Biological Insight

Protocol: Benchmarking OTU vs. ASV Performance on Your Data

To empirically determine which method is more appropriate for your specific research system, follow this validation protocol using a mock community.

1. Experimental Design and Sequencing:

- Sample Type: Include a mock community standard with a known composition alongside your experimental samples. This provides a ground truth for validation [17] [13].

- DNA Extraction & Library Prep: Extract DNA and prepare 16S rRNA gene amplicon libraries (e.g., targeting the V4 region) using a consistent protocol [19]. The Ion Torrent PGM platform with DADA2 and the Greengenes database has been shown to be particularly accurate for mock communities [17].

- Sequencing: Sequence the mock community and experimental samples in the same run to control for run-specific effects.

2. Bioinformatic Processing:

- Parallel Analysis: Process the raw sequencing data (FASTQ files) through two separate pipelines:

- Taxonomic Assignment: Assign taxonomy to the resulting OTUs and ASVs using a consistent reference database (e.g., Greengenes or SILVA).

3. Downstream Analysis and Evaluation:

- Accuracy Assessment (Mock Community): Compare the inferred composition of the mock community from both pipelines to the known, expected composition.

- Calculate Error Rates: Measure the rate of false positives (taxa detected that are not in the mock) and false negatives (taxa in the mock that were not detected) [13].

- Diversity Metrics: Compare alpha and beta diversity measures between the two methods for your experimental samples. Note that the choice of pipeline can have a stronger effect on presence/absence indices like richness than on other parameters [18].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this benchmarking protocol:

Protocol: A Standardized DADA2 Workflow for High-Resolution Analysis

For researchers choosing to implement an ASV-based approach, the following workflow using the DADA2 package in R is a widely adopted and effective standard.

1. Filter and Trim: Quality filter and trim raw forward and reverse reads based on quality profiles. This often involves truncating reads where quality drops significantly. 2. Learn Error Rates: Model the error rates from the sequencing data. This sample-specific error model is crucial for DADA2's denoising accuracy. 3. Dereplication: Combine identical reads to reduce redundancy and improve computational efficiency. 4. Denoising (Core Algorithm): Apply the DADA2 algorithm itself to the dereplicated data. This step infers true biological sequences and removes sequencing errors. 5. Merge Paired-End Reads: Merge the denoised forward and reverse reads to create the full-length ASV sequences. 6. Remove Chimeras: Identify and remove chimeric sequences that arise from the PCR amplification process. 7. Assign Taxonomy: Classify the final ASVs taxonomically using a reference database.

This workflow results in a high-resolution, reproducible ASV table ready for ecological and statistical analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, kits, and software essential for conducting 16S rRNA gene sequencing experiments and analysis.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Ion 16S Metagenomics Kit | A commercial kit designed for targeted 16S sequencing on Ion Torrent platforms. It uses two primer sets to amplify multiple hypervariable regions (V2-4-8 and V3-6,7-9) for broad bacterial identification [20]. |

| TaqMan Environmental Master Mix 2.0 | A PCR master mix optimized for amplifying DNA from complex environmental samples, which often contain PCR inhibitors. It is used in kits like the Ion 16S Metagenomics Kit [20]. |

| DADA2 (Open-Source R Package) | A core software tool for ASV-based analysis. It implements a denoising algorithm to infer true biological sequences from amplicon data with high resolution [17] [18] [13]. |

| Greengenes Database | A reference taxonomy database used for taxonomic assignment of 16S rRNA sequences. It has been shown to be effective in combination with DADA2 and Ion Torrent sequencing [17]. |

| Mock Community (e.g., HC227) | A defined mix of genomic DNA from known bacterial strains. It is an essential control for benchmarking the accuracy and error rate of your wet-lab and bioinformatic workflows [13]. |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | A fluorometric method for accurate quantification of DNA concentration. This is critical for normalizing input DNA for library preparation, as recommended by service providers like GENEWIZ [21] [19]. |

| (S)-Remoxipride hydrochloride | Remoxipride Hydrochloride |

| Fmoc-D-HoPhe-OH | Fmoc-D-HoPhe-OH, CAS:135994-09-1, MF:C25H23NO4, MW:401.5 g/mol |

Decision Framework and Concluding Recommendations

The following diagram outlines a logical decision process to guide researchers in choosing between OTU and ASV approaches:

Conclusion: The field of microbial ecology is undergoing a definitive shift toward ASV-based methods due to their superior resolution, reproducibility, and accuracy [13] [16]. For new studies, especially those investigating strain-level dynamics or requiring cross-study comparison, an ASV pipeline is the recommended choice. OTU-based approaches remain viable for specific contexts, such as integrating with historical datasets or when computational constraints are a primary concern. Ultimately, validating your chosen method with a mock community tailored to your system of interest is the most robust strategy to ensure your conclusions about the microbial world are both precise and reliable.

Within the framework of a broader thesis on resolving low-resolution results in 16S rRNA gene sequencing, understanding the limitations of reference databases is a critical first step. Even with perfect experimental execution, the quality and completeness of the reference database directly dictate the accuracy and specificity of your taxonomic identifications. This guide addresses the common database-related issues that hinder precise identification and provides actionable troubleshooting strategies for researchers and drug development professionals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why can't my 16S rRNA sequencing data reliably identify bacterial species?

Your data may lack species-level resolution primarily due to two interconnected factors: the inherent genetic similarity of the 16S rRNA gene between closely related species and the quality of the reference database used for classification.

- Genetic Similarity: The 16S rRNA gene is a conserved marker. Closely related species, such as Escherichia coli and Shigella spp., can have near-identical or identical 16S rRNA gene sequences, making them impossible to distinguish based on this single gene [22] [23].

- Database Completeness: Many widely used databases contain a high proportion of sequences that are not annotated to the species level or are annotated with vague labels like "uncultured bacterium" [24]. If a database does not contain a high-quality, species-level reference sequence for your target organism, accurate identification is precluded.

2. What are the most common types of errors found in 16S reference databases?

Common errors that propagate through analyses include:

- Taxonomic Misannotation: Sequences are assigned an incorrect taxonomic identity. It is estimated that approximately 3.6% of prokaryotic genomes in GenBank and 1% in its curated subset, RefSeq, are affected by taxonomic error [22] [23].

- Sequence Contamination: Databases contain sequences with contamination from vectors, hosts, or other organisms. One systematic evaluation identified over 2 million contaminated sequences in GenBank [22] [23].

- Excessive Redundancy: Many sequences in a database may be from the same species, inflating the database size without adding new taxonomic information, which can slow down analyses and obscure results [24].

- Unspecific Labelling: Sequences are annotated only to a higher taxonomic rank (e.g., genus or family) and lack species-level identification [23].

3. I am using a popular database like SILVA or Greengenes. Why are my results still problematic?

While popular and widely used, these databases have known limitations that can impact resolution:

- Incomplete Annotation: A significant portion of sequences in historical databases like Greengenes and the RDP are not annotated at the species level [24].

- Curation Gaps: Some databases have not been updated for many years, meaning they lack recently discovered species [24]. Furthermore, while SILVA is manually curated, its initial design was to store all publicly available 16S sequences, not solely to serve as a curated identification database, leading to a bias in its sequence distribution [24].

- Non-Standard Taxonomy: Some newer databases, like the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB), provide a standardized taxonomy based on genome phylogeny but may collapse medically important species (like E. coli and Shigella) into a single taxon or use non-standard naming conventions, which can be problematic for clinical applications [22] [24] [23].

4. How does the choice of a variable region for sequencing affect identification accuracy?

The variable region (e.g., V4, V1-V3) you sequence has a major impact on taxonomic resolution. Sequencing the full-length (~1500 bp) 16S rRNA gene provides significantly better species-level discrimination than any single variable region [25].

Table 1: Performance of Common 16S rRNA Gene Sub-regions for Species-Level Identification

| Sequenced Region | Relative Performance for Species-Level ID | Notable Taxonomic Biases |

|---|---|---|

| Full-Length (V1-V9) | Best | Most consistent performance across taxa [25] |

| V1-V3 | Good | Poor for Proteobacteria [25] |

| V3-V5 | Moderate | Poor for Actinobacteria [25] |

| V4 | Worst | Fails to classify a high percentage of sequences to species [25] |

Short-read platforms (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) are limited to sequencing one or a few variable regions, which represents a historical compromise. The advent of high-throughput long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) now makes full-length 16S sequencing a realistic and superior option for achieving high resolution [25] [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Low Taxonomic Resolution

Problem: Inability to achieve species-level identification.

Step 1: Interrogate Your Reference Database

The first step is to assess the quality of the database you are using.

- Action: Evaluate your current database for the issues described in the FAQs. Check the proportion of sequences that have species-level labels versus those labeled "uncultured" or "unidentified."

- Mitigation: Consider switching to or supplementing with a specialized, curated database designed for species-level identification. Examples include:

Step 2: Optimize Your Bioinformatics Pipeline

The algorithms used to cluster sequences and assign taxonomy can introduce or mitigate errors.

- Action: Compare the output of different bioinformatics tools.

- For clustering into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), note that algorithms like UPARSE achieve lower errors but may over-merge biologically distinct sequences into the same cluster [13].

- For denoising into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), algorithms like DADA2 produce a consistent output but can over-split sequences from the same genome (due to intragenomic variation) into multiple ASVs [13].

- Mitigation: Use a mock community of known composition to benchmark your entire workflow, from sequencing to bioanalysis, to understand the specific biases and error rates of your pipeline [13] [27].

Step 3: Consider an Alternative Sequencing Approach

If 16S rRNA sequencing cannot provide the required resolution, even after optimizing the database and pipeline, a more powerful method may be necessary.

- Action: Move beyond 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

- Mitigation:

- Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: This method sequences all the genetic material in a sample, allowing for identification and functional analysis based on multiple genes, which provides much higher taxonomic resolution and can often distinguish strains [22].

- Long-Read Sequencing: Platforms like PacBio and Oxford Nanopore can sequence the entire 16S rRNA gene, capturing all variable regions and maximizing discriminatory power [25] [26]. They also enable shotgun metagenomics without the need for assembly, simplifying the detection of complete genes and operons.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the decision-making process for selecting and validating a reference database.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Resources for Improving 16S rRNA Database Quality and Analysis

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| Mock Microbial Communities | A controlled mix of genomic DNA from known bacterial species. | Serves as a ground truth for benchmarking the accuracy and resolution of your entire wet-lab and computational pipeline [13] [27]. |

| Curated 16S Databases (e.g., MIMt) | Databases with sequences rigorously filtered for species-level annotation and less redundancy. | Replacing default databases with these can immediately improve the accuracy and specificity of taxonomic assignments [24]. |

| Bioinformatic Tools (GUNC, CheckM) | Computational tools designed to detect contamination in sequence databases and genomes. | Used to screen and clean custom or public databases before use, preventing false positives from contaminated references [22] [23]. |

| Full-Length 16S rRNA Primers | PCR primers designed to amplify the entire ~1500 bp 16S rRNA gene. | Used with long-read sequencers to capture maximum sequence variation, overcoming the limitation of short variable regions [25]. |

| Taxonomic Classifiers (RDP, SPINGO) | Algorithms (e.g., the RDP Classifier, SPINGO) that assign taxonomy to sequences based on a reference database. | Some classifiers, like SPINGO, are specifically designed to improve accuracy at the species level and can be tested alongside standard tools [27]. |

Next-Generation Solutions: Platform and Algorithm Choices for Enhanced Fidelity

Platform Comparison & Technical Specifications

The choice between short-read and long-read sequencing technologies significantly impacts the resolution and depth of 16S rRNA gene sequencing results.

Table 1: Sequencing Platform Technology Overview

| Feature | Illumina (Short-Read) | PacBio (Long-Read) | Oxford Nanopore (Long-Read) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 50-600 bp [28] | Thousands to tens of kilobases [28] | Thousands to tens of kilobases [28] |

| Typical 16S Target | Single or multiple variable regions (e.g., V3-V4) [29] [5] | Full-length 16S gene (V1-V9) [29] [5] | Full-length 16S gene (V1-V9) [29] [30] |

| Key Chemistry | Sequencing by synthesis [1] | Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing [28] | Nanopore electrophoresis [28] |

| Accuracy | >99.9% [28] | ~Q27 (HiFi reads) [29] | ~Q20 and improving with new chemistries [29] [30] |

| Primary Advantage | High throughput, low cost per base [28] | High accuracy for long reads [28] | Portability, real-time analysis [28] |

Performance Comparison in 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

Empirical studies directly comparing these platforms reveal critical differences in their ability to resolve bacterial taxonomy.

Table 2: Performance Comparison for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

| Performance Metric | Illumina (e.g., V3-V4) | PacBio (Full-Length) | Oxford Nanopore (Full-Length) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species-Level Resolution | 47-55% of reads classified [29] [5] | 63-74% of reads classified [29] [5] | 76% of reads classified [29] |

| Genus-Level Resolution | 80-95% of reads classified [29] [5] | 85-95% of reads classified [29] [5] | 91% of reads classified [29] |

| Ability to Resolve Closely Related Species | Limited [25] [5] | Improved [25] [5] | Improved [30] |

| Common Bioinformatic Approach | ASV/OTU (e.g., DADA2) [29] | ASV (e.g., DADA2) [29] [5] | OTU/Denoising (e.g., Emu, Spaghetti) [29] [30] |

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for short-read and long-read 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 16S rRNA Sequencing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Platform Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil) [29] | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from samples. | Long-read sequencing requires high-molecular-weight DNA [28]. |

| 16S PCR Primers (e.g., 27F/1492R) [29] [31] | Amplification of the target 16S rRNA gene region. | Illumina: Target hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4). Long-read: Target full-length gene (V1-V9) [29]. |

| PCR Master Mix (e.g., KAPA HiFi) [29] [31] | High-fidelity amplification of the 16S gene. | Critical for minimizing PCR errors in all platforms. |

| Library Prep Kit (Platform-Specific) | Preparation of amplicons for sequencing. | Must be selected for the specific sequencing platform (e.g., SMRTbell for PacBio [29], SQK-16S024 for Nanopore [29]). |

| Reference Database (e.g., SILVA) [29] [30] | Taxonomic classification of sequenced reads. | Database choice significantly impacts classification accuracy, especially for Nanopore [30]. |

| 8-Isoprostaglandin E2 | 8-Isoprostaglandin E2, CAS:27415-25-4, MF:C20H32O5, MW:352.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fura-FF pentapotassium | Fura-FF pentapotassium, MF:C28H18F2K5N3O14, MW:853.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: I am getting low species-level resolution with my Illumina V3-V4 data. Should I switch to a long-read platform? Yes, if species-level identification is critical for your research. Multiple studies confirm that sequencing the full-length 16S rRNA gene with PacBio or Nanopore improves species-level classification rates significantly—from about 47% with Illumina to 63-76% with long-read platforms [29] [5]. This is because the full-length gene contains more informative nucleotide variation across all variable regions, providing a stronger phylogenetic signal [25].

Q2: Are there any specific bioinformatic tools recommended for analyzing full-length 16S data from PacBio or Nanopore? Yes, the choice of tools is platform-dependent due to differing error profiles:

- PacBio HiFi Reads: The high accuracy of HiFi reads allows the use of the DADA2 pipeline to generate Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), similar to the Illumina workflow [29] [5].

- Oxford Nanopore Reads: The higher error rate and lack of internal redundancy make DADA2 less suitable. Instead, specialized tools like Emu [30] or Spaghetti [29] that employ different denoising or OTU-clustering approaches are recommended.

Q3: My long-read sequencing results show many sequences classified as "uncultured_bacterium" at the species level. What does this mean? This is a common limitation, not a failure of your sequencing. It indicates that the specific bacterial species in your sample is not yet represented in the reference database used for taxonomic assignment [29]. This highlights a broader challenge in microbiology, where many environmental and host-associated microbes have not been isolated or sequenced. Using the most comprehensive and up-to-date databases can help mitigate this issue.

Q4: For a new project with a limited budget, which 16S variable region should I sequence with Illumina for the best resolution? If you are constrained to short-read sequencing, the V1-V3 region often provides a reasonable approximation of microbial diversity and has been shown to be a good compromise for skin and other microbiomes [31]. However, note that no single hypervariable region can perfectly recapitulate the resolution achieved by the full-length gene [25].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent taxonomic profiles between different sequencing platforms.

- Cause: This is a known issue caused by a combination of factors, including the specific 16S region targeted, PCR primer bias, and the platform's own technical artifacts [29].

- Solution:

- Wet Lab: Use the same DNA extraction for all platform comparisons to minimize batch effects.

- Bioinformatics: Apply a consistent, platform-appropriate bioinformatic pipeline. Be cautious when comparing or merging datasets generated from different platforms and primer sets [29].

- Interpretation: Focus on the overall community structure (beta-diversity) and major taxonomic groups, which should cluster by sample type rather than by sequencing platform, rather than expecting identical abundances for every taxon [5].

Problem: Low classification accuracy with Oxford Nanopore data.

- Cause: The inherent higher error rate of Nanopore sequencing can interfere with precise taxonomic assignment.

- Solution:

- Basecalling: Use the most accurate available basecalling model (e.g., "sup" or "hac" in Dorado) rather than the "fast" model, as the basecalling quality significantly influences downstream results [30].

- Database: Carefully select your reference database. The structure and composition of the database (e.g., SILVA vs. Emu's default database) can greatly influence the number and accuracy of species identifications [30].

Figure 2: A logical troubleshooting guide for diagnosing and solving low-resolution issues in 16S rRNA sequencing.

The resolution of 16S rRNA gene sequencing has long been constrained by technological limitations and bioinformatic challenges. While the full-length ~1500 bp 16S gene provides the highest taxonomic discrimination, most studies have historically sequenced only specific variable regions due to the read-length limitations of earlier sequencing platforms [25]. This represents a fundamental compromise, as different variable regions possess varying discriminatory power for distinct bacterial taxa [32] [25]. Furthermore, bioinformatic algorithms must distinguish true biological variation from sequencing errors and handle intragenomic variation between multiple 16S gene copies within a single organism [25] [13]. This technical support guide benchmarks four prominent algorithms—DADA2, DEBLUR, UNOISE3, and UPARSE—to help researchers select optimal strategies for overcoming these resolution limitations.

Algorithm Performance Benchmarking

Key Performance Metrics from Comparative Studies

Independent benchmarking studies using mock microbial communities have revealed critical differences in how algorithms resolve microbial sequences.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of 16S rRNA Analysis Algorithms

| Algorithm | Algorithm Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Performance Characteristics | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 | ASV (Denoising) | Highest [33] | Lower [33] | Best recall (sensitivity); prone to over-splitting [13] [33] | Moderate [13] |

| DEBLUR | ASV (Denoising) | Moderate [13] | High [33] | Balanced performance; lower error rates [13] | Fast (runs in a single step) [13] |

| UNOISE3 | ASV (Denoising) | High [33] | Highest [33] | Best balance between resolution and specificity [33] | Moderate [13] |

| UPARSE | OTU (Clustering) | Moderate [33] | High [33] | Lower error rates; prone to over-merging [13] | Fastest [13] |

Resolution at Species and Strain Levels

Sequencing the full-length 16S rRNA gene is superior to targeting sub-regions for species-level classification. One study demonstrated that while the V4 region failed to confidently classify 56% of sequences to the correct species, the full-length gene successfully classified nearly all sequences [25]. ASV-level methods (DADA2, DEBLUR, UNOISE3) generally provide higher taxonomic resolution than OTU-level methods like UPARSE because they distinguish sequences differing by a single nucleotide [33]. Modern full-length sequencing combined with algorithms that account for intragenomic 16S copy variation can even enable strain-level discrimination [25].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Analysis Issues and Solutions

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Algorithm Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| High rates of spurious OTUs/ASVs | Inadequate quality control; algorithm-specific error profile | For DADA2: Adjust quality filtering parameters [33] | Use synthetic mock communities to validate pipelines [34] |

| Over-splitting of biological sequences | Algorithm splitting intragenomic 16S variants into separate ASVs [13] | Use UNOISE3, which shows better specificity [33] | Select algorithms that balance sensitivity and specificity [33] |

| Over-merging of distinct taxa | OTU clustering with overly relaxed identity cutoff [13] | Use ASV methods or stricter clustering thresholds [13] | Use ASV-level methods for finer resolution [33] |

| Inconsistent results between pipelines | Different default parameters; algorithmic approaches | Re-analyze data with multiple pipelines for consensus [33] | Document all parameters and software versions used [35] |

| Low taxonomic resolution | Short read length; uninformative variable region [25] | Sequence full-length 16S gene if possible [25] | Select variable region based on target taxa [32] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Which algorithm provides the best balance between sensitivity and specificity for resolving closely related strains? A: Based on comparative studies, USEARCH-UNOISE3 generally provides the best balance, offering high sensitivity while maintaining the highest specificity among ASV methods [33].

Q2: Why does my analysis with DADA2 produce more ASVs than expected? A: DADA2 has the highest sensitivity but is prone to "over-splitting," where it may generate multiple ASVs from a single biological sequence due to intragenomic variation or minor sequencing errors [13] [33]. This can be mitigated by adjusting quality filtering parameters.

Q3: How does the choice of 16S variable region affect resolution? A: Different variable regions have varying discriminatory power for different bacterial taxa [32] [25] [34]. For instance, the V4 region performs poorly for species-level classification (failing to classify 56% of sequences in one study), while the V1-V3 region provides a reasonable approximation of diversity [25]. The full-length gene consistently provides the best resolution [25].

Q4: Should I use OTU or ASV methods for my study? A: ASV methods (DADA2, DEBLUR, UNOISE3) generally provide higher resolution and are more reproducible across studies, as they generate consistent sequence variants without clustering [33]. OTU methods (UPARSE) may be preferable for studies where computational efficiency is critical or when analyzing highly diverse communities where over-splitting is a concern [13].

Q5: How can I validate my bioinformatic pipeline's performance? A: Incorporate synthetic mock communities with known composition into your sequencing runs [34]. This allows you to quantify the error rate, sensitivity, and specificity of your chosen algorithm and parameters [13] [34].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Standardized Workflow for Method Comparison

The following workflow, based on published benchmarking studies [13] [33], provides a standardized approach for comparing algorithm performance:

Diagram 1: Algorithm Benchmarking Workflow

Protocol Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Use well-characterized synthetic mock communities (e.g., BEI Resources Mock Community [33] or HC227 complex mock [13]) alongside experimental samples.

- Library Preparation: Amplify the desired 16S rRNA variable region (e.g., V4 [33] or V3-V4 [13]) using validated primer sets.

- Sequencing: Sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq for short reads [33]).

- Quality Control: Process raw sequences through uniform preprocessing:

- Merge paired-end reads (if applicable)

- Quality filtering (maxEE=0.01-1.0 [13])

- Remove ambiguous bases and chimeras

- Parallel Analysis: Process the same quality-filtered dataset through each algorithm (DADA2, DEBLUR, UNOISE3, UPARSE) using default or recommended parameters.

- Performance Evaluation: Compare outputs against the known mock community composition for:

- Sensitivity: Proportion of expected taxa recovered

- Specificity: Number of spurious OTUs/ASVs generated

- Quantitative accuracy: Correlation between expected and observed abundances

Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for 16S rRNA Benchmarking

| Item | Function | Example Products/Details |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Mock Communities | Positive control for evaluating pipeline accuracy and bias | BEI Resources HM-782D [33]; HC227 (227 strains) [13] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | PCR amplification with minimal bias | Kapa HiFi HotStart, Q5 Polymerase [34] |

| Validated 16S Primer Sets | Amplification of target variable regions | 515F/806R (V4) [33]; 341F/785R (V3-V4) [13] |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Preparing amplicon libraries for sequencing | Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit [33] |

| Bioinformatic Workflow Management | Reproducible pipeline execution and error tracking | Nextflow, Snakemake [35] |

| Data Quality Control Tools | Assessing raw sequence data quality | FastQC, MultiQC [35] |

| 4-Fluoro phenibut hydrochloride | 4-Fluoro phenibut hydrochloride, CAS:3060-41-1, MF:C10H14ClNO2, MW:215.67 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ethylbenzene-d10 | Ethylbenzene-d10, CAS:25837-05-2, MF:C8H10, MW:116.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Algorithm Selection Guide

The choice of algorithm involves trade-offs between resolution, specificity, and computational efficiency. The following decision pathway can help guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate tool:

Diagram 2: Algorithm Selection Guide

To maximize resolution in 16S rRNA sequencing studies, researchers should consider a multi-faceted approach:

- Select the most informative variable region for their target taxa or, if possible, utilize full-length 16S sequencing [25].

- Choose algorithms based on their specific needs: DADA2 for maximum sensitivity, UNOISE3 for the best balance, or UPARSE for computational efficiency [33].

- Incorporate mock communities in every sequencing run to quantify pipeline performance and identify biases [34].

- Document all parameters and software versions meticulously to ensure reproducibility [35].

The ongoing development of both sequencing technologies and analysis algorithms continues to improve the resolution achievable through 16S rRNA gene sequencing, enabling more precise microbial community analysis for biomedical and environmental applications.

For decades, 16S rRNA gene sequencing has been the cornerstone of microbial ecology, enabling researchers to decipher the composition of complex bacterial communities. However, the historical compromise of sequencing short hypervariable regions (typically 300-600 bp) has imposed significant limitations on taxonomic resolution, particularly at the species and strain levels. The advent of third-generation sequencing platforms has made high-throughput sequencing of the full-length 16S rRNA gene (approximately 1500 bp, spanning regions V1-V9) a practical reality. This technical guide explores how leveraging V1-V9 sequencing resolves the pervasive challenge of low taxonomic resolution in microbiome research, providing scientists with enhanced capability for species discrimination in diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

FAQs: Understanding Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

What is the fundamental advantage of sequencing the full V1-V9 region over single hypervariable regions?

Sequencing the entire V1-V9 region provides significantly enhanced taxonomic resolution compared to single hypervariable regions. Short-read sequencing of individual variable regions (e.g., V4 or V3-V4) typically limits identification to the genus level, whereas full-length sequencing enables discrimination at the species and even strain level [5] [25]. This improvement occurs because the complete 1,500 bp sequence contains all nine variable regions, capturing the maximum evolutionary information available from the 16S gene for taxonomic classification [36].

Experimental evidence demonstrates that different variable regions have varying discriminatory power for specific bacterial taxa. One study found that while the V1-V2 region performed poorly for classifying Proteobacteria, and V3-V5 struggled with Actinobacteria, the complete V1-V9 region consistently produced the best results across all major phylogenetic groups [25]. The V4 region, commonly used in Illumina-based studies, performed particularly poorly, failing to confidently classify 56% of sequences to the species level in silico experiments [25].

How does full-length 16S sequencing improve species-level identification in human microbiome studies?

Full-length 16S sequencing dramatically increases the proportion of reads that can be confidently assigned to the species level. A 2024 comparative study analyzing human saliva, oral biofilm, and fecal samples found that while both Illumina (V3-V4 regions) and PacBio (V1-V9) platforms assigned a similar percentage of reads to the genus level (approximately 95%), PacBio full-length sequencing enabled a significantly higher proportion of reads to be further assigned to the species level (74.14% versus 55.23%) [5].

This enhanced resolution is particularly valuable for discriminating between closely related species with highly similar 16S sequences, such as streptococci or the Escherichia/Shigella group [5]. For example, in the analysis of oral microbiota, full-length 16S sequencing revealed a higher relative abundance of Streptococcus species compared to short-read methods (20.14% vs 14.12% in saliva), though these differences were not statistically significant after multiple testing corrections [5].

What are the technical considerations for primer selection in full-length 16S sequencing?

Primer selection critically influences the accuracy and representativeness of full-length 16S sequencing results. Different primer sets can yield strikingly different taxonomic profiles, even when sequencing the same samples [36]. A 2023 study comparing two primer sets (27F-I included in Oxford Nanopore's kit and a more degenerate 27F-II set) for human fecal microbiome analysis found significant differences in both taxonomic diversity and relative abundance across numerous taxa [36].

The conventional 27F primer (27F-I) revealed significantly lower biodiversity and showed an unusually high Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio compared to the more degenerate primer set (27F-II) [36]. When evaluated against expected microbiome compositions from the American Gut Project, the more degenerate primer set (27F-II) better reflected the anticipated composition and diversity of fecal microbiomes [36]. This highlights the importance of primer optimization and selection for accurate representation of complex bacterial communities.

Can full-length 16S sequencing resolve strain-level variation?

Emerging evidence indicates that full-length 16S sequencing can detect strain-level variation through the identification of intragenomic copy variants - subtle sequence differences between multiple copies of the 16S gene within a single bacterial genome [25]. Modern sequencing platforms achieve sufficient accuracy to resolve single-nucleotide substitutions that exist between these intragenomic copies [25].

This capability is significant because many bacterial genomes contain multiple polymorphic copies of the 16S gene [25]. Appropriate bioinformatic treatment of these intragenomic variants has the potential to provide taxonomic resolution at the strain level, which is valuable for tracking clinically relevant strains or predicting phenotypic characteristics [25]. However, researchers must account for this variation in their analysis pipelines to avoid misinterpreting genuine intragenomic variation as representing distinct taxa.

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Library Yield in Full-Length 16S Amplicon Sequencing

Symptoms:

- Final library concentrations below expected values (e.g., < 10-20% of predicted yield)

- Broad or faint peaks on electropherogram traces

- Dominance of adapter-dimer peaks (~70-90 bp) in size distribution

Root Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor input DNA quality | Low 260/230 ratios (<1.8), smeared electrophoregram | Re-purify input sample; ensure fresh wash buffers; use fluorometric quantification instead of UV absorbance [37] |

| Suboptimal PCR amplification | Increased small fragments (<100 bp), primer artifacts | Optimize cycling conditions; verify primer specificity; consider two-step indexing to reduce artifacts [37] |

| Inefficient bead cleanup | Unusual fragment size distribution, carryover contaminants | Adjust bead:sample ratios; avoid over-drying beads; implement rigorous washing steps [38] [37] |

| Insufficient input material | Low starting yield despite adequate concentration | Verify input DNA quality and quantity; use recommended 10 ng high molecular weight gDNA per barcode as starting point [38] |

Prevention Strategy: Implement a rigorous quality control workflow for input DNA, including fluorometric quantification and integrity assessment. Use master mixes to reduce pipetting errors, and validate each lot of purification beads with control DNA [37].

Taxonomic Representation Bias in Microbial Communities

Symptoms:

- Under-representation of Gram-positive bacteria (especially Firmicutes)

- Discrepancy between observed community structure and expected composition

- Inconsistent results between technical replicates

Root Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal DNA extraction | Consistent under-representation of difficult-to-lyse taxa | Implement improved lysis protocols (e.g., alkaline/heat/detergent methods) to replace gentle enzymatic lysis [39] |

| Primer bias | Systematic differences in diversity metrics between primer sets | Use degenerate primers (e.g., 27F-II instead of 27F-I); validate primer performance with mock communities [36] |

| Differential lysis efficiency | Variable recovery of Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative bacteria | Employ standardized bead-beating parameters; consider chemical lysis methods effective against tough cell walls [39] |

Experimental Protocol for Improved DNA Extraction: The "Rapid" microbial DNA extraction protocol has demonstrated improved representation of Firmicutes species compared to standard protocols [39]:

- Start with ≤10 mg of fecal sample material

- Apply alkaline lysis buffer with KOH combined with heat and detergent simultaneously

- Process samples in 96-well plate format for consistency

- Purify DNA using standard column-based or bead-based methods

- Validate extraction efficiency with mock communities containing both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria

This non-enzymatic, non-mechanical approach has been shown to provide more uniform lysis across diverse bacterial populations, reducing the under-representation of Firmicutes species common with gentler lysis methods [39].

Inaccurate Species-Level Assignment

Symptoms:

- Low proportion of reads assigned to species level (<60%)

- Ambiguous taxonomic assignments for closely related species

- Inconsistent classification of streptococci or Escherichia/Shigella groups

Root Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient sequence information | Limited discrimination between highly similar species | Switch from partial to full-length 16S gene sequencing (V1-V9) to capture all variable regions [5] [25] |

| Database limitations | High proportion of "unclassified" at species level | Use comprehensive, curated databases; regularly update reference sequences [40] |

| Platform-specific errors | Misclassification due to sequencing errors | Leverage circular consensus sequencing (CCS) to achieve high accuracy (>Q20) [5] [25] |

Experimental Protocol for Full-Length 16S Sequencing with PacBio:

- DNA Extraction: Use standardized protocol (e.g., HMP protocol or improved "Rapid" method) to ensure representative lysis [39]

- PCR Amplification: Amplify full-length 16S rRNA gene using primers 27F (5'-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R (5'-CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3') [5]

- Library Preparation: Prepare SMRTbell libraries according to manufacturer's instructions

- Sequencing: Perform Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) on PacBio Sequel II system to generate high-fidelity (HiFi) reads

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process reads using DADA2 or similar pipeline that accounts for intragenomic copy variation [25]

Performance Comparison: Full-Length vs. Partial 16S Sequencing

The table below summarizes quantitative performance differences between full-length V1-V9 sequencing and short-read approaches based on recent comparative studies:

| Metric | Illumina (V3-V4) | PacBio (V1-V9) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species-level assignment rate | 55.23% [5] | 74.14% [5] | +18.91% |

| Genus-level assignment rate | 94.79% [5] | 95.06% [5] | +0.27% |

| Discrimination of closely related species | Limited [25] | High [25] | Significant |

| Detection of intragenomic variation | Not feasible [25] | Possible [25] | New capability |

| Representation of Streptococcus in saliva | 14.12% [5] | 20.14% [5] | +6.02% |

Workflow Diagrams

Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Specific Product | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | "Rapid" alkaline/heat/detergent protocol [39] | Provides uniform lysis of diverse bacterial cells, including difficult-to-lyse Firmicutes |

| Full-Length Amplification | Degenerate primer set 27F-II [36] | Improves coverage of diverse bacterial taxa compared to conventional 27F-I primer |

| Long-read Sequencing | PacBio Sequel II with SMRT sequencing [5] | Enables high-fidelity full-length 16S sequencing through circular consensus sequencing |

| Library Preparation | Oxford Nanopore 16S Barcoding Kit [38] | Facilitates multiplexed sequencing of full-length 16S amplicons on nanopore platform |

| Quality Control | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit [38] | Provides accurate quantification of input DNA and final libraries |

The transition from short-read sequencing of hypervariable regions to full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing represents a significant advancement in microbiome research. By capturing the complete V1-V9 region, researchers can achieve substantially improved taxonomic resolution at the species level, enabling more precise microbial characterization in diagnostic, therapeutic, and ecological applications. While methodological considerations around primer selection, DNA extraction, and bioinformatic processing remain critical, the implementation of optimized protocols and troubleshooting strategies detailed in this guide will empower researchers to overcome the longstanding challenge of low resolution in 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

The introduction of Oxford Nanopore Technologies' (ONT) R10.4.1 flow cell chemistry represents a transformative advancement for clinical and research microbiology, specifically enabling high-resolution, species-level identification through full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing. This case study evaluates the impact of R10.4.1 chemistry and subsequent basecalling improvements on taxonomic resolution within the context of 16S rRNA gene sequencing research. By comparing traditional short-read (Illumina V3V4) and long-read (ONT V1V9) approaches, recent research demonstrates that the R10.4.1 chemistry, combined with optimized bioinformatic pipelines, facilitates the discovery of more precise, disease-specific bacterial biomarkers—a crucial capability for diagnostics and therapeutic development [41]. This technical support document provides a comprehensive framework for implementing this technology, including validated experimental protocols, performance metrics, and targeted troubleshooting guides to resolve common challenges encountered during workflow establishment.

R10.4.1 Chemistry

Oxford Nanopore's R10.4.1 chemistry features an updated nanopore design that significantly improves the accuracy of base recognition, particularly in homopolymer regions. This enhancement is fundamental for sequencing the full-length ~1500 bp 16S rRNA gene (V1-V9 regions), which provides the necessary sequence diversity to discriminate between closely related bacterial species. The technology sequences any length of native DNA/RNA molecule electronically, eliminating PCR bias and enabling direct detection of epigenetic modifications [42].

Basecalling with Dorado

Basecalling, the process of translating raw electrical signals into nucleotide sequences, utilizes machine learning models within the Dorado basecaller. Accuracy is tiered through different models to balance speed and precision according to experimental needs [42]:

- Fast Basecalling: Recommended for real-time insights when computational resources are limited.

- High Accuracy (HAC): Provides highly accurate basecalling suitable for most variant analysis projects.

- Super Accuracy (SUP): The most accurate and computationally intensive model, recommended for de novo assembly and low-frequency variant analysis.

- Duplex Basecalling: Sequences both strands of a DNA molecule for maximum accuracy, recommended for hemi-methylation investigation [42].

The latest Dorado basecalling models (v5) can achieve raw read accuracies of up to 99.75% (Q26) [42]. This high single-read accuracy is critical for species-level assignment, as a quality threshold of Q20 (99% accuracy) is considered the minimum for confidently assigning an Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) to a specific species using full-length 16S rRNA sequencing [41].

Performance Data and Validation

Quantitative Accuracy Metrics

Table 1: Basecalling and Consensus Accuracy of R10.4.1 Chemistry

| Metric | Performance | Sequencing & Basecalling Parameters | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-read Accuracy | >99% (Q20) [42]; up to Q26 with Dorado v5 [42] | R10.4.1 flow cell, latest SUP models | Raw read accuracy for single DNA/RNA strand |

| Variant Calling (SNPs) | Comparable to short-read methods [42] | Q20+ chemistry | Microbial genotyping |

| Assembly Accuracy | Q50 at 10–20x coverage (bacterial genomes) [42] | MinION R10.4.1, Ligation Sequencing Kit V14, Simplex SUP | De novo assembly of mock communities |

| DNA Modification (5mC) | 99.5% accuracy in CpG context [42] | Raw read accuracy (SUP) | Epigenetic studies in bacteria |

Impact on Species-Level Identification

A 2025 study directly compared Illumina (V3V4) and ONT R10.4.1 (V1V9) for bacterial biomarker discovery in colorectal cancer (CRC), analyzing feces from 123 subjects [41].

Table 2: Species-Level Biomarkers Identified by R10.4.1 Full-Length 16S Sequencing

| Bacterial Species Identified as CRC Biomarkers | Detection Method |

|---|---|

| Parvimonas micra | ONT R10.4.1 (V1V9) |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | ONT R10.4.1 (V1V9) & Illumina (V3V4) |

| Peptostreptococcus stomatis | ONT R10.4.1 (V1V9) |

| Peptostreptococcus anaerobius | ONT R10.4.1 (V1V9) |

| Gemella morbillorum | ONT R10.4.1 (V1V9) |

| Clostridium perfringens | ONT R10.4.1 (V1V9) |

| Bacteroides fragilis | ONT R10.4.1 (V1V9) & Illumina (V3V4) |

| Sutterella wadsworthensis | ONT R10.4.1 (V1V9) |

The study found that while basecalling models (fast, hac, sup) broadly resulted in similar taxonomic output, lower-quality basecalling led to significantly higher observed species counts and different taxonomic identifications, highlighting the importance of model selection. Furthermore, database choice greatly influenced results, with the Emu's Default database yielding higher diversity but sometimes overconfidently classifying unknown species compared to the SILVA database [41]. The ability to sequence the full-length 16S rRNA gene was critical, as Illumina's short-read approach targeting only the V3V4 regions (~400 bp) was restricted mostly to genus-level identification [41] [43].

Experimental Protocols

Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Workflow

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Sample Material: Use well-characterized reference materials (e.g., NML MCM2α/MCM2β, WHO WC-Gut RR) for validation alongside clinical samples [43].

- Cell Lysis: For clinical samples, subject to bead beating using Lysing Matrix E tubes on a TissueLyser (50 oscillations/second for 2 minutes) [43].

- DNA Extraction: Validate the performance of at least one DNA extraction method (e.g., AusDiagnostics MT-Prep, QIAamp DNA Micro Kit, MagMAX Microbiome Ultra Kit) with your sample type. For tissues, pre-process with Tissue Lysis Buffer and proteinase K (2 hours at 56°C) before bead-beating [43].

PCR Amplification and Library Preparation

- Target Region: Amplify the full-length ~1500 bp 16S rRNA gene (V1-V9 regions).

- PCR Conditions: Carefully optimize PCR cycle numbers to prevent non-specific over-amplification of low-abundance environmental microorganisms, which can reduce diagnostic sensitivity [43].

- Library Preparation: Use the Ligation Sequencing Kit V14 (SQK-LSK114) with R10.4.1 flow cells, following manufacturer's protocols [42].

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

Basecalling and Read Processing

- Basecalling: Process POD5 files from the sequencer using Dorado.

Use the

supmodel for the highest accuracy in species-level analysis [41]. - Adapter Trimming: Trim adapter and primer sequences using Dorado's integrated trimming function.

Taxonomic Classification

For full-length 16S rRNA reads, use a taxonomy assignment tool designed for long reads, such as Emu [41]. The choice of reference database (e.g., SILVA vs. Emu's Default database) significantly influences results and should be reported and justified [41].

Basecalling Optimization Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for R10.4.1 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

| Item | Function/Description | Example Products/References |

|---|---|---|

| R10.4.1 Flow Cell | Core sensing device; improved homopolymer accuracy. | MinION Mk1C, PromethION [42] |

| Ligation Sequencing Kit | Library preparation for DNA sequencing. | Ligation Sequencing Kit V14 (SQK-LSK114) [42] |

| Metagenomic Control Materials | Validation and standardization of the entire workflow. | NML MCM2α/MCM2β, WHO WC-Gut RR [43] |

| Bead Beating Tubes | Mechanical lysis for efficient DNA extraction from diverse samples. | Lysing Matrix E tubes (MP Bio, 6914100) [43] |

| DNA Extraction Kit | High-yield, unbiased microbial DNA extraction. | AusDiagnostics MT-Prep, QIAamp DNA Micro Kit [43] |

| Full-Length 16S Primers | Amplification of the ~1500 bp V1-V9 region. | Standard 27F/1492R or equivalent [41] |

| Dorado Basecaller | Translates raw signals to base sequences with HAC/SUP models. | Oxford Nanopore Dorado (v5.0+) [42] [44] |

| Taxonomic Classification Tool | Assigns taxonomy to long-read 16S sequences. | Emu [41] |

| Reference Database | Curated 16S sequences for taxonomic assignment. | SILVA, Emu's Default Database [41] |

| 1-Methoxycyclopropanecarboxylic acid | 1-Methoxycyclopropanecarboxylic acid, CAS:100683-08-7, MF:C5H8O3, MW:116.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Which basecalling model should I use for 16S rRNA species-level identification? For the highest species resolution, use the Super Accuracy (SUP) model in Dorado. While High Accuracy (HAC) and fast models produce broadly similar taxonomic output, the SUP model minimizes errors that can lead to over-splitting or misclassification at the species level [41].

Q2: My basecalling results show different species counts depending on the database I use. Which is correct? Database choice significantly influences results. The SILVA database may provide more conservative classifications, while Emu's Default database often identifies more species but can overconfidently assign an unknown species as the closest known match. The choice depends on your research goals: use SILVA for conservative analysis or Emu's database for maximum discovery, with caution regarding potential over-classification [41].