Reconstructing Prokaryotic Regulons: A Comparative Genomics Guide for Decoding Transcriptional Networks

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the computational reconstruction of prokaryotic transcriptional regulatory networks using comparative genomics.

Reconstructing Prokaryotic Regulons: A Comparative Genomics Guide for Decoding Transcriptional Networks

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the computational reconstruction of prokaryotic transcriptional regulatory networks using comparative genomics. It covers foundational concepts of transcription factors and regulons, details established and emerging methodologies for regulon prediction, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and discusses techniques for experimental validation and evolutionary analysis. Aimed at researchers and scientists in microbiology and drug development, this guide synthesizes current tools and frameworks to enable accurate prediction of gene regulatory interactions across diverse bacterial species, with direct implications for understanding bacterial pathogenesis, metabolism, and designing novel antimicrobial strategies.

Core Principles of Bacterial Transcription Regulation and Regulon Evolution

Defining Regulons, Transcription Factors, and Their Role in Bacterial Adaptation

In bacterial genetics, a regulon is defined as a set of transcription units (operons) controlled by a single regulatory protein—a transcription factor (TF) [1]. This organization allows for the coordinated expression of multiple genes, often involved in related cellular functions, in response to specific environmental or intracellular signals. The activity of most bacterial transcription factors is modulated by environmental signals, enabling bacteria to adapt rapidly to changing conditions [2]. Transcription factors function by recognizing specific DNA sequences at target promoters and subsequently either activating or repressing transcript initiation by RNA polymerase [2].

Table 1: Key Definitions in Bacterial Transcriptional Regulation

| Term | Definition | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Regulon | A set of operons transcriptionally co-regulated by the same regulatory protein [3] [1]. | Enables coordinated response across multiple genetic loci. |

| Transcription Factor (TF) | A DNA-binding protein that activates or represses transcript initiation at specific promoters [2]. | Activity is often controlled by a specific environmental or cellular signal. |

| Operon | A polycistronic transcription unit containing multiple co-regulated genes [4]. | Allows for coordinated expression of functionally related genes. |

| Core Regulon | The set of target genes directly related to the TF's primary signal and conserved across species [4]. | Evolves slowly due to direct functional connection to the signal. |

| Extended Regulon | The set of target genes that reflect adaptations to correlated environmental factors [4]. | Evolves rapidly and is often species- or niche-specific. |

Evolution and Genomic Organization of Regulons

Evolutionary Dynamics of Regulatory Networks

Regulons are not static; they evolve rapidly to allow bacterial adaptation. Comparative genomics studies reveal that orthologous transcription factors often regulate distinct sets of genes in related bacterial species [5]. This evolutionary rewiring is driven by two primary mechanisms: the gain or loss of transcription factor binding sites in the promoters of shared genes, and the acquisition of new target genes through horizontal gene transfer [5]. The concept of core and extended regulons helps frame this evolution. The core regulon comprises functions directly related to the signal relayed by the transcription factor (e.g., oxygen availability for FnrL) and is generally conserved across species. In contrast, the extended regulon includes functions adapted to correlated signals specific to an organism's ecological niche, such as pathogenesis functions in the Mg2+-responsive PhoP regulon of some species [4].

Physical Organization in the Genome

The component operons of a regulon are not randomly distributed in the bacterial chromosome. Computational studies of E. coli and B. subtilis have demonstrated that operons belonging to the same regulon tend to form clusters in terms of their genomic locations [3]. These clusters often consist of genes working in the same metabolic pathway. Furthermore, the global arrangement of regulons in a genome appears to follow an organizational principle that minimizes the total distance between the TF and all its target operons, suggesting selective pressure for efficient co-regulation [3]. Interestingly, the genomic locations of transcription factors themselves are under stronger evolutionary constraints than the locations of their target genes [3].

The following diagram illustrates the key concepts of regulon organization and evolution:

Diagram 1: Regulon structure and evolutionary dynamics. TFs control a regulon composed of a conserved core and a variable extended regulon, driving adaptation.

Protocols for Regulon Reconstruction and Analysis

Comparative Genomics Workflow for Regulon Prediction

A standard methodology for reconstructing regulons across multiple bacterial genomes leverages comparative genomics to identify conserved transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) [6].

Protocol Steps:

- Genome Selection and Ortholog Identification: Select a set of evolutionarily related but non-redundant reference genomes. Identify orthologs of the transcription factor of interest across these genomes using bidirectional best-hit BLAST searches and phylogenetic analysis [6].

- Training Set Construction: Compile an initial training set of known regulon members (operons) from model organisms. The upstream regulatory regions of these operons are used to identify a conserved sequence motif [6].

- Motif Discovery and PWM Building: Extract and align upstream sequences of candidate operons. Use expectation-maximization or Gibbs sampling algorithms to identify a conserved TFBS motif. Convert the aligned sites into a position weight matrix (PWM) [6].

- Genomic Scanning and Regulon Expansion: Use the PWM to scan the upstream regions of all genes in the selected genomes. Predict new TFBSs based on a predefined score threshold. Manually curate predictions by analyzing the metabolic context and conserved gene neighborhoods of candidate operons [6].

- Phylogenetic Profiling of Regulons: Compare the reconstructed regulons across different taxonomic groups to identify core (conserved), taxonomy-specific, and genome-specific members. This reveals the evolutionary history of the regulatory network [6].

Experimental Validation Using Sort-Seq for TFBS Characterization

The sort-seq method is a powerful high-throughput experimental technique for quantitatively mapping the relationship between TFBS sequences and their regulatory output [7].

Protocol Steps:

- Library Construction: Engineer a plasmid-based reporter system where the gene for a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) is placed under the control of a promoter containing a randomized TFBS library. For an 8-bp core binding site, this library will contain 65,536 (4^8) unique sequence variants [7].

- Cell Sorting and Binning: Transform the plasmid library into a bacterial strain expressing the transcription factor. In the absence of the inducer, subject the cell population to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Sort cells into multiple bins based on their level of fluorescence, which corresponds to the strength of transcriptional repression [7].

- Deep Sequencing and Data Analysis: Isolate plasmids from each bin and deep-sequence the TFBS region. For each sequence variant, the distribution across bins is used to compute a quantitative measure of repression strength, creating a comprehensive genotype-phenotype map [7].

- Landscape Analysis: Analyze the resulting data to determine the ruggedness of the regulatory landscape, identify epistatic interactions between nucleotides, and model the evolutionary accessibility of high-affinity binding sites [7].

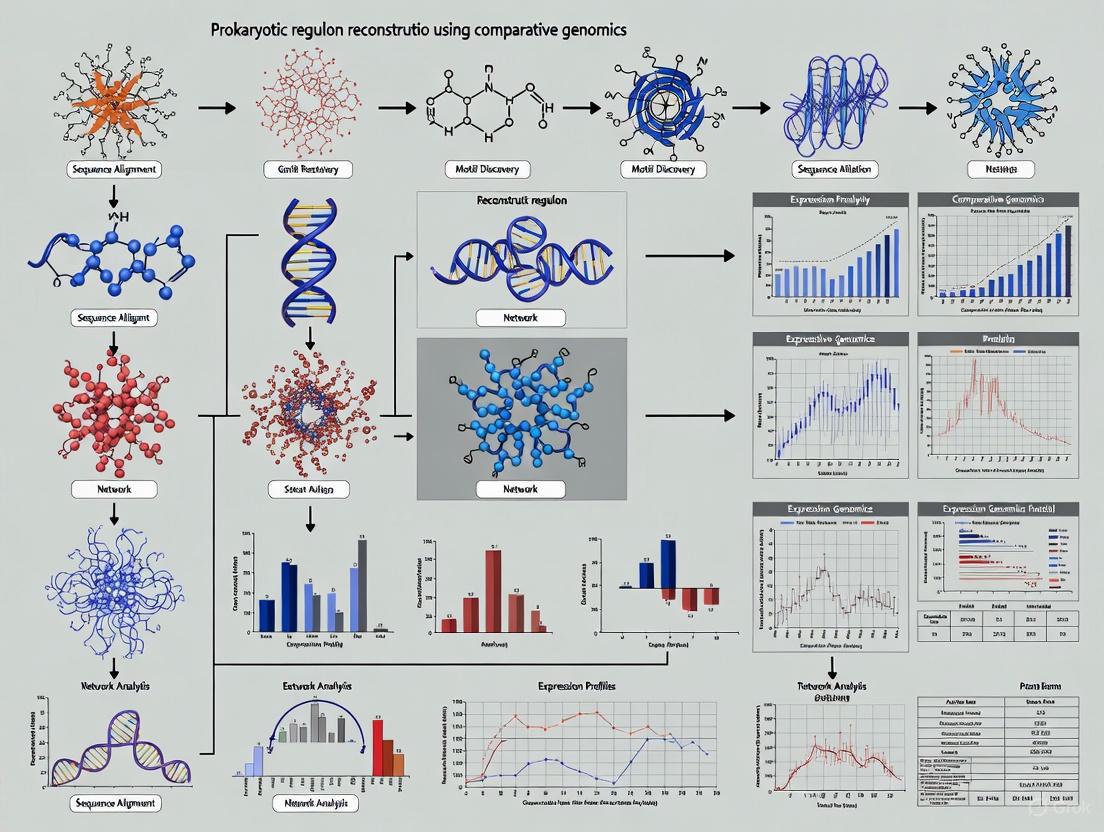

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for the comparative genomics approach:

Diagram 2: Comparative genomics workflow for regulon reconstruction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Resources for Regulon Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example or Source |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Regulon Databases | Provide reference data for known regulatory interactions and operon structures for comparative analysis. | RegulonDB [1], DBTBS [3], RegPrecise [6] |

| Comparative Genomics Tools | Platforms for motif discovery, TFBS prediction, and regulon reconstruction across multiple genomes. | RegPredict [6] |

| Fluorescent Reporter Plasmids | Engineered constructs for measuring promoter activity and TF regulatory function in vivo. | Plasmid systems with GFP/mCherry [7] |

| Mutagenized TFBS Libraries | Comprehensive sequence variant libraries for characterizing TFBS specificity and mapping regulatory landscapes. | Randomized oligo pools for sort-seq [7] |

| Flow Cytometry with Cell Sorting (FACS) | High-throughput measurement and physical separation of cells based on reporter gene expression levels. | Used in sort-seq protocol [7] |

| High-Throughput Sequencing | Identification and quantification of sequence variants from sorted bins in functional genomics screens. | Illumina sequencing [7] |

| R-Impp | R-Impp, MF:C24H27N3O2, MW:389.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Risuteganib | Risuteganib, CAS:1307293-62-4, MF:C22H39N9O11S, MW:637.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application Note: Predicting Niche-Specific Adaptation inBifidobacterium

Large-scale genomic reconstruction of carbohydrate utilization regulons in Bifidobacterium exemplifies the power of comparative genomics for predicting strain-specific adaptations with direct implications for probiotic development [8]. By analyzing the distribution of 589 curated metabolic gene functions (catabolic enzymes, transporters, and transcriptional regulators) across 3,083 genomes, researchers reconstructed 68 pathways for utilizing dietary glycans [8].

This analysis revealed extensive inter- and intraspecies functional heterogeneity. For instance, a distinct clade within Bifidobacterium longum was identified that possesses the unique ability to metabolize α-glucans, a capability not shared by all conspecifics [8]. Furthermore, isolates from a Bangladeshi population carried unique gene clusters for utilizing xyloglucan (a plant hemicellulose) and human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), suggesting local genomic adaptation to dietary components [8]. This regulon-based compendium provides a framework for rationally designing probiotic and synbiotic formulations tailored to the specific glycan utilization profiles of strains and the dietary habits of target human populations [8].

In prokaryotes, the regulation of gene expression is a complex process orchestrated by the interplay of transcription factors (TFs), sigma factors, and their cognate DNA binding sites. These components form the foundational circuitry of transcriptional regulatory networks, enabling bacteria to adapt to environmental changes, metabolize diverse nutrients, and coordinate growth. Within the framework of comparative genomics, the systematic identification and characterization of these elements allow for the reconstruction of regulons—sets of genes or operons controlled by a common regulator. This application note details the key molecular components, experimental methodologies, and computational protocols for reconstructing prokaryotic regulons, providing a structured resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in microbial genomics and systems biology.

Key Molecular Components in Prokaryotic Transcription

The following table summarizes the core components involved in the initiation and regulation of prokaryotic transcription.

Table 1: Core Molecular Components of Prokaryotic Transcription Initiation and Regulation

| Component | Molecular Function | Role in Regulon Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|

| Sigma Factor (σ) | Enables RNA polymerase (RNAP) promoter recognition and binding; facilitates promoter DNA melting [9] [10]. | Serves as a primary regulator of global transcriptional responses; diversity indicates niche specialization. |

| Core RNA Polymerase | Catalyzes DNA-directed RNA synthesis [9]. | A ubiquitous "housekeeping" complex; its interaction with sigma factors is a key regulatory node. |

| Transcription Factor (TF) | Sequence-specific DNA-binding protein that activates or represses transcription initiation [11]. | The defining regulator of a regulon; its binding sites define regulon membership. |

| TF Binding Site (TFBS) | Short, specific DNA sequence (motif) recognized and bound by a TF [11]. | The genomic "signature" used to identify all genes within a regulon. |

| Anti-Sigma Factor | Protein that binds to and inhibits sigma factor activity, preventing transcription initiation [10]. | An additional layer of post-translational regulation for sigma-dependent regulons. |

Quantitative Data and Genomic Analysis

Large-scale genomic studies provide quantitative insights into the distribution and variability of these components across bacterial taxa. The following table summarizes findings from a major genomic analysis of carbohydrate utilization in Bifidobacterium, illustrating the scale of regulon diversity [8].

Table 2: Quantitative Summary of a Large-Scale Genomic Reconstruction of Carbohydrate Utilization Regulons in Bifidobacterium [8]

| Analysis Parameter | Quantitative Result |

|---|---|

| Number of Non-Redundant Genomes Analyzed | 3,083 |

| Number of Curated Metabolic Functional Roles | 589 |

| Number of Reconstructed Catabolic Pathways | 68 |

| Pathways for Mono-/Disaccharides | 18 |

| Pathways for Di-/Oligosaccharides | 39 |

| Pathways for Polysaccharides | 11 |

| Accuracy of Genomics-Based Phenotype Predictions (vs. in vitro growth data) | 94% |

This study highlights extensive inter- and intraspecies functional heterogeneity. For instance, the phenotypic richness (number of utilization pathways) varied significantly even between phylogenetically close subspecies, driven by the presence or absence of pathways for substrates like fucosylated human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) and plant oligosaccharides [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Silico Reconstruction of a Transcription Factor Regulon

This protocol outlines the comparative genomics workflow for reconstructing a TF regulon, based on the methodology applied to LacI-family regulators [11].

4.1.1. Materials and Reagents

- Genomic Sequences: A set of complete or draft genomes from the target bacterial lineage(s).

- Bioinformatics Software:

- Genome Annotation Pipeline: (e.g., Prokka) for initial gene calling.

- Ortholog Grouping Tool: Software implementing the bidirectional best-hit criterion (e.g., ProteinOrtho, OrthoFinder).

- Motif Discovery Suite: (e.g., MEME, GLAM2) for identifying conserved DNA motifs.

- Phylogenetic Tree Software: (e.g., RAxML, FastTree) for building maximum-likelihood trees.

4.1.2. Procedure

- TF Identification: Identify all genes encoding TFs of a specific family (e.g., LacI) in your target genomes using homology searches (e.g., BLASTP) and domain prediction (Pfam domains PF00356 for DNA-binding and PF00532 for sugar-binding) [11].

- Define Orthologous Groups: Cluster the identified TFs into orthologous groups using a combination of bidirectional best-hit analysis and phylogenetic tree construction [11].

- Identify Candidate Regulon Members: For each orthologous TF group, select upstream regulatory regions of (i) the TF gene itself and (ii) genes encoding potential target metabolic enzymes (e.g., glycosyl hydrolases, transporters) based on genomic context.

- Discover Conserved Motifs: Use motif discovery software on the collected upstream regions to identify a conserved, palindromic DNA motif (the putative TFBS).

- Reconstruct the Regulon: Scan the upstream regions of all genes in the genome with the identified motif to define the full set of candidate target genes.

- Infer TF Function: Analyze the functional annotations of the target genes to infer the biological role of the TF and its potential effector ligand (e.g., a specific sugar).

Protocol 2: In Vitro Validation of Predicted Carbohydrate Utilization Phenotypes

This protocol describes a method for validating genomics-based predictions of substrate utilization, as used in bifidobacterial studies [8].

4.2.1. Materials and Reagents

- Bacterial Strains: The validated or newly isolated bacterial strains to be tested.

- Growth Media: Chemically defined or semi-defined liquid medium, lacking carbohydrates.

- Carbon Sources: Purified candidate glycans (e.g., HMOs, plant oligosaccharides) to be tested.

- Sterile Culture Ware: Anaerobic chambers or jars for cultivating anaerobic gut bacteria.

- Spectrophotometer: For measuring optical density (OD) to quantify growth.

4.2.2. Procedure

- Preparation: Inoculate strains into a rich medium and incubate under appropriate conditions. Harvest cells in the mid-exponential phase.

- Basal Washes: Wash the cell pellets twice with a carbohydrate-free basal medium to deplete endogenous carbon stores.

- Inoculation: Inoculate the washed cells into the defined growth medium supplemented with a specific test glycan as the sole carbon source. Include a negative control (no carbon source) and positive controls (e.g., glucose, lactose).

- Growth Monitoring: Measure the OD at 600nm (OD600) at regular intervals over a 24-48 hour period.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the maximum OD and growth rate for each strain on each substrate. A strain is confirmed as a "utilizer" if its growth significantly exceeds that of the negative control.

Visualization of Workflows and Mechanisms

Sigma Factor-Core RNA Polymerase Interaction in Transcription Initiation

Comparative Genomics Workflow for Regulon Reconstruction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents, databases, and software tools essential for prokaryotic regulon reconstruction.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Regulon Reconstruction

| Item Name | Specifications / Example Sources | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Genomic Compendium | Non-redundant dataset of isolate genomes and high-quality MAGs (completeness ≥97%, contamination ≤3%) [8]. | Provides the foundational data for comparative genomics and pangenome-scale analysis. |

| Functional Role Annotation Set | Manually curated set of gene functions (e.g., 589 roles for glycan metabolism [8]). | Enables accurate pathway reconstruction and phenotype prediction, surpassing automated annotations. |

| RegPrecise Database | Public database (http://regprecise.lbl.gov) for curated collections of reconstructed regulons [11]. | Repository of reference regulons for validation and comparative analysis. |

| dbCAN Database | Database for Carbohydrate-Active Enzyme (CAZyme) annotation [8]. | Critical for annotating glycan catabolic enzymes in metabolic reconstructions. |

| MicrobesOnline Database | Platform for integrated comparative genomics, including phylogenetic trees and gene orthology [11]. | Aids in ortholog identification and evolutionary analysis. |

| Motif Discovery Software (MEME Suite) | Tools for de novo discovery of conserved DNA motifs from upstream sequences [11]. | Identifies the cis-regulatory binding motif for a TF. |

| Random Forest Classifier | Machine learning model trained on reference genomic signatures [8]. | Automates the prediction of metabolic phenotypes (e.g., glycan utilization) from genomic data. |

| RK-287107 | RK-287107, MF:C22H26F2N4O2, MW:416.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| RL648_81 | RL648_81, MF:C17H17F4N3O2, MW:371.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Power of Comparative Genomics for Large-Scale Regulon Prediction

The prediction of regulons—sets of genes or operons controlled by a common transcription factor—is fundamental to understanding genetic regulatory networks. For prokaryotic systems, where experimental data can be sparse, comparative genomics techniques provide a powerful in silico approach for large-scale regulon reconstruction. These methods leverage the evolutionary principle that functional relationships, including coregulation, are often conserved across species. By analyzing patterns of genome organization and evolution across multiple organisms, researchers can accurately predict regulon memberships and their associated cis-regulatory motifs, enabling the reconstruction of entire regulatory networks on a genome-wide scale [12] [13].

This application note details the primary computational protocols for prokaryotic regulon prediction, focusing on methods based on conserved operon structures, protein fusion events, and correlated evolutionary patterns (phylogenetic profiles). We provide step-by-step methodologies, implementation details, and validation techniques to guide researchers in applying these powerful comparative genomics strategies.

Core Methodologies for Regulon Prediction

Three principal comparative genomics methods are optimized for predicting functional interactions and coregulated sets of genes. The following sections provide detailed protocols for each.

Method 1: Predictions Based on Conserved Operons

Principle: If two genes are consistently found within the same operon across multiple genomes, they are likely functionally related and potentially coregulated. Conservation of this arrangement across larger evolutionary distances provides stronger evidence for a functional link [12] [13].

Experimental Protocol:

- Identify Homologs: For each gene in the target genome, perform a BLAST search against a database of other complete genomes (e.g., 23 other bacterial genomes) using an E-value cutoff of 10-5 to identify homologs [12].

- Find Conserved Gene Pairs: Identify all pairs of non-homologous genes (i and j) in the target genome that have homologs located within the same operon in at least two other distinct genomes.

- Score Interactions: Calculate a weighted interaction score (aij) for each gene pair. The score is weighted by the evolutionary distance between the genomes exhibiting the conserved operon structure. Pairs conserved in more distantly related organisms receive higher confidence scores [12].

- Construct Interaction Matrix: Build an N×N interaction matrix for the target genome (where N is the number of genes). Set all diagonal values (homologous links) to zero to prevent clustering of homologous proteins.

- Cluster Genes: Apply a hierarchical clustering algorithm to the interaction matrix using an evolutionary distance cutoff (e.g., 0.1) to group genes into predicted coregulated sets, or regulons [12].

Method 2: Predictions Based on Protein Fusions (Rosetta Stone Method)

Principle: If two separate proteins in one organism are found as a single fused protein in another organism, the two original proteins are likely functionally interacting or participating in the same pathway [12].

Experimental Protocol:

- Search for Fusion Events: For all non-homologous protein pairs in the target genome, search a non-redundant protein database for a single polypeptide chain that contains two non-overlapping BLAST hits (E-value < 10-5) to the respective proteins [12].

- Weight the Evidence: For each linking fusion protein, calculate an interaction score based on the BLAST E-values of the two constituent hits. Use the higher of the two E-values in the calculation:

- Assign a score of 1.0 if the highest E-value is < 10-40.

- For E-values between 10-5 and 10-40, calculate the score as the negative log of the E-value divided by 10 [12].

- Filter Common Domains: To reduce false positives from common domains, exclude any protein that is linked through fusion events to 50 or more other proteins with scores greater than 0.1 [12].

- Populate Interaction Matrix: Add the calculated scores to the corresponding entries in the master N×N interaction matrix.

Method 3: Predictions Based on Correlated Evolution (Phylogenetic Profiles)

Principle: Proteins that function together in a pathway or complex are often preserved or eliminated together throughout evolution. Thus, homologs of functionally linked genes will be present or absent in the same subset of genomes [12].

Experimental Protocol:

- Construct Phylogenetic Profiles: For each gene in the target genome, create a binary presence-absence profile (phylogenetic profile) across all genomes in the comparison set. A '1' indicates the presence of a homolog (BLAST E-value < 10-5), and a '0' indicates its absence [12].

- Identify Correlated Profiles: Compute the correlation between all pairs of phylogenetic profiles. High correlation suggests a functional interaction.

- Score and Matrix Population: Score the interaction based on the correlation metric and add this to the master interaction matrix. The specific correlation and scoring algorithm should be optimized for the dataset, as detailed methodology was truncated in the available source [12].

Integrated Workflow for Regulon Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow integrating the three core methodologies for final regulon prediction.

Workflow for Integrated Regulon Prediction

Computational Implementation andCis-Regulatory Motif Discovery

Software and Data Integration

The three methods are implemented to generate individual N×N interaction matrices. These matrices are summed to produce a final integrated matrix of functional interaction predictions [12]. This matrix is then clustered to define the initial set of predicted regulons.

- Software Availability: Software for performing these analyses was available via

http://arep.med.harvard.edu/regulon_pred[12]. - Genome Selection: The original analysis utilized 24 complete genomes, including 22 prokaryotes, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Caenorhabditis elegans, though motif discovery was focused on the prokaryotes [12].

Motif Discovery with AlignACE

Objective: To identify shared regulatory motifs within the upstream regions of genes in a predicted regulon, thereby validating and refining the regulon membership [12].

Protocol:

- Extract Upstream Sequences: For all genes within a predicted regulon cluster, extract the DNA sequences upstream of their translation start sites.

- Run AlignACE: Use the motif-discovery program AlignACE on the set of upstream sequences to identify overrepresented DNA motifs [12].

- Filter Homologous Motifs: Exclude any motif where more than one-third of its instances are located upstream of homologous genes. This ensures the discovery of regulatory motifs rather than conserved protein-coding sequences [12].

- Refine Regulons: Use the presence of a significant, shared upstream motif to refine the initial regulon prediction. The final regulon should include only the subset of genes that both cluster together and share the significant regulatory element in their upstream regions [12].

Validation and Application

Benchmarking and Quantitative Measures

Evaluating the performance of regulon prediction methods requires robust quantitative measures. While traditional metrics like gene counts are useful, more sophisticated measures such as Annotation Edit Distance (AED) can quantify the structural changes in gene models and regulatory annotations between database releases, providing a finer-grained view of annotation refinement [14].

Case Study: Expanding the CRP and FNR Regulons

A comparative genomics approach between Escherichia coli and Haemophilus influenzae successfully expanded the known regulons for the global transcription factors CRP (cAMP receptor protein) and FNR (fumarate and nitrate reduction regulatory protein) [13].

Protocol for Application:

- Build Weight Matrices: Create position-specific weight matrices for the transcription factor (e.g., CRP, FNR) by aligning known binding sites from a well-studied organism (e.g., E. coli) using tools like CONSENSUS [13].

- Predict Binding Sites: Scan the upstream regions of all genes in both the target and reference genomes for matches to the weight matrix using a tool like PATSER.

- Integrate Orthology and Operon Data: Combine the predicted binding sites with data on orthologous genes and predicted transcription units (operons) in both genomes.

- Predict Novel Regulon Members: Genes are predicted as novel regulon members if their orthologs in another genome are also predicted to be bound by the same factor, leveraging the principle of regulon conservation [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key computational tools and data resources essential for conducting the regulon prediction protocols described herein.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Comparative Regulon Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Protocol | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST | Software | Identifies homologous genes and proteins across genomes for all three methods [12]. | [12] |

| AlignACE | Software | Discovers overrepresented regulatory DNA motifs in upstream sequences of predicted regulons [12]. | [12] |

| CONSENSUS/PATSER | Software | Builds weight matrices from known sites and scans for new binding sites for specific TFs like CRP/FNR [13]. | [13] |

| Curated Genome Database | Data | Provides essential comparative data; requires multiple complete, annotated genomes (e.g., 24 genomes used in original study) [12]. | WIT database [12] |

| Non-Redundant Protein DB | Data | Used for identifying protein fusion (Rosetta Stone) events [12]. | NCBI nr database |

| Annotation Edit Distance (AED) | Metric | Quantifies changes in gene model structure, useful for tracking annotation refinement and benchmarking [14]. | [14] |

The integrated application of conserved operon, protein fusion, and phylogenetic profile analyses provides a robust, computational framework for the large-scale prediction of regulons in prokaryotic organisms. The power of this comparative genomics approach is significantly enhanced by subsequent motif discovery, which serves to validate and refine the initial predictions. Adherence to the detailed protocols and utilization the specified research reagents will enable researchers to reconstruct and analyze transcriptional regulatory networks in a wide array of bacterial and archaeal species, dramatically accelerating systems-level biological understanding.

A regulon, defined as a set of genes or operons directly co-regulated by a single transcription factor (TF), constitutes a fundamental unit of transcriptional organization in prokaryotes [6] [15]. Understanding the evolutionary dynamics of regulons—how they expand, shrink, and undergo replacement—is critical for deciphering the adaptation of microbial metabolism to diverse environmental conditions [6]. These dynamics are driven by processes including the duplication and loss of transcription factors and their binding sites, leading to observable evolutionary events such as regulon mergers, splits, and the recruitment of non-orthologous regulators [6]. Comparative genomics provides a powerful approach to reconstruct these dynamics across diverse bacterial lineages, revealing the principles governing the evolution of transcriptional regulatory networks [6]. This Application Note details the protocols and conceptual frameworks for analyzing these processes, providing researchers with methodologies to investigate regulon evolution within the broader context of prokaryotic systems biology.

Quantitative Landscape of Regulon Evolution

Large-scale comparative genomic studies have begun to quantify the scale of regulon dynamics. One comprehensive analysis of 33 orthologous groups of transcription factors across 196 reference genomes from 21 taxonomic groups of Proteobacteria predicted over 10,600 TF binding sites and identified more than 15,600 target genes for 1,896 transcription factors [6]. The study demonstrated that regulon composition varies significantly, with core, taxonomy-specific, and genome-specific members classified by their metabolic functions [6].

Table 1: Documentated Cases of Regulon Dynamics in Proteobacteria

| Evolutionary Process | Specific Example | Observed Outcome | Taxonomic Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Orthologous Replacement | Methionine metabolism regulation | MetJ/MetR (Gammaproteobacteria) replaced by SahR/SamR or RNA riboswitches in other lineages [6] | Multiple lineages of Proteobacteria |

| Lineage-Specific Expansion | MetR regulon in Gammaproteobacteria | Core includes only metE and metR; extensive lineage-specific target gene additions [6] | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Functional Shift | Branched-chain amino acid, N-acetylglucosamine, and biotin utilization | LiuR/LiuQ, NagC/NagR/NagQ, and BirA/BioR regulons show lineage-specific expansions and substitutions [6] | Various bacterial taxa |

| Novel Regulon Prediction | Aromatic amino acid metabolism in Alteromonadales and Pseudomonadales | Prediction of novel regulators HmgS and HmgQ replacing TyrR/PhrR and HmgR regulons [6] | Alteromonadales and Pseudomonadales |

| Novel Regulon Prediction | NAD metabolism in Betaproteobacteria and Alphaproteobacteria | Prediction of a novel regulator, NadQ [6] | Betaproteobacteria and Alphaproteobacteria |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Core Workflow for Comparative Genomic Reconstruction of Regulons

The foundational approach for studying regulon evolution involves the comparative genomic reconstruction of regulons across multiple related genomes. The following workflow, implemented in the RegPredict server, provides a standardized protocol for this analysis [15].

Protocol 1: Regulon Reconstruction via Comparative Genomics

Principle: This protocol leverages conservation of TF binding sites across evolutionarily related genomes to identify regulon members and assess their conservation patterns [6] [15].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Genome Selection: Select a set of 4-16 taxonomically related prokaryotic genomes from the MicrobesOnline database. Avoid including very closely related strains to prevent skewing the training set [6].

- Workflow Selection:

- Path A (Known Motif): If a Positional Weight Matrix (PWM) for the TF of interest is available from databases like RegPrecise, RegTransBase, or RegulonDB, use the "Regulon inference based on known PWM" workflow [15].

- Path B (De Novo Inference): If no PWM is available, use the "De novo regulon inference workflow." Construct a training set of potentially co-regulated genes based on: a) genes from a functional pathway; b) genes homologous to known regulon members in a model organism; c) genes from conserved operons containing the TF gene; or d) genes with co-expression data [15].

- Motif Identification and CRON Construction:

- For Path A, scan all upstream regions in the target genomes with the known PWM.

- For Path B, identify conserved candidate TFBS motifs in the upstream regions of the training set using a MEME-like iterative algorithm to build a de novo PWM [15].

- The system automatically constructs CRONs (Clusters of co-Regulated Orthologous operons), which group orthologous operons that share candidate TFBSs. This facilitates the assessment of conservation levels [15].

- Manual Curation and Regulon Finalization:

- Manually review each CRON via the RegPredict interactive web interface, which integrates genomic context and functional information.

- Accept CRONs with strong phylogenetic conservation of TFBSs.

- The final regulon model is synthesized from all accepted CRONs [15].

Protocol for Analyzing Regulon Dynamics Using iModulons in Evolved Strains

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) coupled with transcriptomic analysis can reveal regulon dynamics in response to specific stresses, even in hypermutator strains where genomic analysis is complex [16].

Protocol 2: iModulon Analysis of Evolved Strains

Principle: Independent Component Analysis (ICA) is applied to large transcriptomic compendia to identify iModulons—independently modulated gene sets that often correspond to regulons. This top-down approach simplifies the analysis of global transcriptomic changes [16].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Strain Generation and RNA-seq:

- Perform ALE under a stress condition of interest (e.g., high temperature) to generate evolved strains [16].

- Prepare RNA-seq libraries from the evolved strains and an ancestral control under multiple relevant conditions.

- iModulon Activity Calculation:

- Map the RNA-seq data to a pre-established iModulon structure for the organism (available at iModulonDB.org).

- Calculate the activity level of each iModulon in every sample. This activity represents the strength of the coregulated signal [16].

- Identification of Adaptive Regulatory Changes:

- Compare iModulon activities between evolved and ancestral strains.

- Identify iModulons with consistently altered activities, which indicate selected-for regulatory changes. For example, in heat-evolved E. coli, this might include the downregulation of general stress response iModulons and the upregulation of specific heat shock iModulons [16].

- Integration with Genomic Data:

- Cross-reference the list of iModulons with altered activities with mutation data from the evolved strains, focusing on mutations in known regulatory genes (e.g., transcription factors, sigma factors) that may explain the observed transcriptomic changes [16].

Table 2: Essential Resources for Regulon Evolution Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Analysis | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| RegPredict | Web Server | Provides integrated tools for comparative genomic inference of regulons using known PWM or de novo workflows [15]. | http://regpredict.lbl.gov |

| MicrobesOnline | Database | Supplies genomic sequences, precomputed orthologs, and operon predictions essential for comparative analysis [6] [15]. | https://www.microbesonline.org/ |

| RegPrecise | Database | Collection of manually curated, computationally predicted regulons and TF binding sites across diverse prokaryotes, used for reference and PWM extraction [6] [15]. | http://regprecise.lbl.gov |

| MEME Suite | Software Toolkit | Used for de novo discovery of conserved DNA motifs (e.g., TFBSs) in upstream sequences of candidate co-regulated genes [17] [15]. | https://meme-suite.org/ |

| iModulonDB | Database | Provides pre-computed iModulon structures for several organisms, enabling transcriptomic analysis of regulon activities in evolved or perturbed strains [16]. | https://imodulondb.org |

Visualization of Evolutionary Patterns

The evolutionary dynamics of regulons can be conceptualized through specific patterns of change, which can be systematically identified using the protocols outlined above.

Concluding Remarks

The evolutionary dynamics of regulons—expansion, shrinkage, and replacement—are fundamental processes shaping the functional adaptability of prokaryotes. The integration of comparative genomics, using tools like RegPredict, with advanced transcriptomic approaches, such as iModulon analysis, provides a powerful, multi-faceted framework for reconstructing and understanding these dynamics. The protocols and resources detailed in this Application Note equip researchers with standardized methods to investigate how transcriptional regulatory networks evolve in response to environmental challenges and metabolic requirements. This knowledge is essential not only for fundamental microbial ecology and evolution but also for applied fields including metabolic engineering and drug development, where predicting and manipulating regulatory outcomes is crucial.

Methodologies and Tools for Computational Regulon Reconstruction

Reconstructing the full set of genes controlled by a regulator (regulon) in prokaryotes is fundamental to understanding bacterial physiology, metabolism, and adaptation. This process typically follows a defined workflow, beginning with the identification of a regulator's DNA-binding motif and culminating in the inference of a complete regulatory network across multiple genomes. Comparative genomics significantly enhances this process by leveraging evolutionary conservation to distinguish functional regulatory sites from random genomic sequences [15] [6]. This Application Note provides a detailed protocol for prokaryotic regulon reconstruction, framed within a comparative genomics strategy, to guide researchers in systematically moving from motif discovery to network inference.

Workflow Fundamentals and Key Concepts

The foundational unit of transcriptional regulation is the transcription factor binding site (TFBS), a short ( typically 12-30 bp), specific DNA sequence to which a transcription factor (TF) binds [15]. The pattern of nucleotides within a set of known TFBSs can be summarized into a positional weight matrix (PWM) or position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM), which quantifies the probability of each nucleotide at each position and serves as a computational model for identifying additional sites [15] [19].

A regulon is defined as the complete set of operons (and thus genes) directly controlled by a single TF [15] [6]. Comparative genomics approaches for regulon inference are based on the principle that functional TFBSs are often conserved in the upstream regions of orthologous genes across related genomes [15] [6]. The Cluster of co-Regulated Orthologous operons (CRON) is a key concept for managing this comparative analysis, where a regulon is broken down into sub-regulons of orthologous operons that share a common regulatory motif [15].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Phase I: Motif Discovery

Objective: To identify a de novo DNA-binding motif for a transcription factor of unknown specificity.

Methods:

Training Set Generation: Compile a set of DNA sequences suspected to be co-regulated. Sources include:

- Functional Pathway: Genes encoding enzymes in a defined metabolic pathway (e.g., amino acid biosynthesis) [6].

- Genomic Context: Genes located in conserved chromosomal loci near the TF gene itself [15].

- Expression Data: Genes showing co-expression under specific conditions from transcriptomic studies (e.g., RNA-seq) [15].

- The recommended sequence length is typically from -400 to +50 bp relative the translation start site.

De Novo Motif Finding: Submit the FASTA-formatted sequence set to one or more motif discovery tools.

- MEME: Uses expectation maximization to find widely conserved, ungapped motifs [20].

- Weeder: Performs an exhaustive enumeration to find motifs conserved in a large fraction of input sequences [20].

- ChIPMunk: An iterative greedy algorithm that combines optimization with bootstrapping [20].

- HOMER: A differential discovery algorithm designed for genomic applications, which identifies motifs enriched in one sequence set relative to a background set [21].

Motif Validation and PWM Construction: The significant motifs identified by the above tools must be aligned. Use this multiple sequence alignment of putative TFBSs to build a PWM. Tools like WebLogo can generate a sequence logo for visual validation [6].

Table 1: Common Motif Discovery Tools and Their Characteristics

| Tool | Algorithm Type | Key Feature | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEME [20] | Expectation-Maximization | Finds broad, conserved motifs | Initial discovery with a confident training set |

| Weeder [20] | Exhaustive Enumeration | Finds motifs conserved in many sequences | Identifying very overrepresented motifs |

| ChIPMunk [20] | Greedy Optimization + Bootstrapping | Fast and efficient | Large sequence sets |

| HOMER [21] | Differential Enrichment (Hypergeometric) | Identifies motifs enriched vs. a background set | ChIP-seq or differentially expressed gene sets |

Phase II: Regulon Inference and Expansion

Objective: To use the PWM to scan genomes and identify all potential regulon members.

Methods:

Genomic Scanning: Use the PWM (converted to a PSSM) to scan the upstream regions of all genes in a target genome. This can be done with custom scripts or integrated platforms.

Comparative Genomics and CRON Construction: To improve prediction accuracy, perform scanning across multiple taxonomically related genomes (e.g., 4-16 genomes) [6].

Probabilistic Framework for Site Assessment: To overcome the limitations of fixed score cut-offs, a Bayesian framework can be employed [19]. This estimates the posterior probability of regulation for a promoter by comparing the distribution of scores in a regulated promoter (a mixture of background and true site distributions) against the background distribution genome-wide [19].

Phase III: Network Inference and Validation

Objective: To reconstruct the complete regulatory network and validate predictions.

Methods:

Regulon Propagation: The refined PWM is used to scan additional genomes within the taxonomic group to propagate the regulon reconstruction [15] [6]. This reveals the core (conserved), taxonomy-specific, and genome-specific members of the regulon [6].

Functional Context Analysis: Analyze the metabolic pathways and biological functions of the predicted regulon members. This step provides biological validation and can reveal the global role of the TF [11].

Experimental Validation: Computational predictions require experimental confirmation. Key techniques include:

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) to test TF binding to predicted promoter regions.

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) to map in vivo binding sites genome-wide.

- RT-qPCR or RNA-seq to measure expression changes of target genes upon TF knockout or overexpression.

Table 2: Key Databases and Software for Regulon Reconstruction

| Category | Name | Function | URL/Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated Workflows | RegPredict [15] | Web server for comparative reconstruction of microbial regulons. | http://regpredict.lbl.gov |

| CGB [19] | Flexible platform for comparative genomics using a Bayesian framework. | Custom pipeline | |

| Motif Discovery | MEME Suite [20] | Integrated tools for de novo motif discovery and scanning. | http://meme-suite.org |

| HOMER [21] | Software for motif discovery and ChIP-seq analysis. | http://homer.ucsd.edu | |

| Databases | RegPrecise [15] [6] | Manually curated database of reconstructed regulons and PWMs. | http://regprecise.lbl.gov |

| MicrobesOnline [15] [6] | Provides genomic sequences, orthologs, and operon predictions. | http://microbesonline.org | |

| RegTransBase [15] | Literature-based database of experimental regulatory interactions. | http://regtransbase.lbl.gov |

Workflow Visualization

Main Regulon Inference Workflow

CRON Construction Logic

Anticipated Results and Interpretation

A successful regulon reconstruction will yield a set of genes consistently predicted to be under the control of a specific TF across multiple genomes. The results are typically categorized into:

- Core Regulon Members: Genes consistently regulated across most or all genomes in the taxonomic group. These often encode key enzymes in a conserved metabolic pathway [6].

- Lineage-Specific Members: Genes found in the regulon of only a subset of genomes, reflecting adaptive evolution and niche specialization [6].

- Novel Functional Associations: Hypothetical proteins or uncharacterized transporters that are consistently co-regulated with genes of known function, providing strong evidence for their involvement in a specific pathway [6] [11].

The evolutionary analysis of reconstructed regulons can reveal phenomena such as non-orthologous replacement of regulators, where different TFs control equivalent pathways in different lineages, and regulon fusion or fission events [6].

The accurate reconstruction of transcriptional regulatory networks (TRNs) is a fundamental challenge in microbial genomics and systems biology. Regulons, defined as sets of genes or operons co-regulated by a common transcription factor (TF) or RNA regulatory element, form the building blocks of these networks [15] [22]. The emergence of comparative genomics approaches has revolutionized this field by leveraging the principle that functional TF-binding sites (TFBSs) are often evolutionarily conserved across related genomes, whereas false positive sites are randomly scattered [15] [23]. This evolutionary conservation provides a powerful filter for distinguishing true regulatory interactions. Dedicated computational platforms have been developed to automate and standardize the process of regulon inference, enabling researchers to move from genomic sequences to predicted regulatory networks in a systematic manner. These tools have become indispensable for generating hypotheses about gene function, understanding microbial adaptation, and reconstructing genome-scale metabolic models with regulatory constraints [24] [8].

Table 1: Key Computational Platforms for Prokaryotic Regulon Reconstruction

| Platform | Primary Function | Key Methodology | Data Sources | User Interface |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RegPredict | Regulon inference and analysis | Comparative genomics, CRON construction | MicrobesOnline, RegPrecise, RegTransBase, RegulonDB | Web server [15] |

| CGB | Comparative regulon reconstruction | Bayesian probabilistic framework, gene-centered analysis | User-provided genomes, NCBI accessions | Standalone pipeline [23] [19] |

| RegPrecise | Database of curated regulons | Collection and visualization of inferred regulons | Manually curated regulons from comparative genomics | Web resource [22] [24] |

Platform-Specific Application Notes and Protocols

RegPredict: An Integrated System for Regulon Inference

Application Notes: RegPredict is designed specifically for comparative genomics reconstruction of microbial regulons using two well-established workflows: reconstruction for known regulatory motifs and ab initio inference of novel regulons [15]. A key innovation in RegPredict is the implementation of Clusters of co-Regulated Orthologous operons (CRONs), which address challenges in comparative analysis by grouping orthologous operons with candidate TFBSs and evaluating the conservation level of regulatory interactions [15]. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing large regulons controlled by global transcription factors, such as CRP in Proteobacteria and CcpA in Firmicutes. The platform integrates genomic sequences, ortholog predictions, and operon structures from the MicrobesOnline database, providing researchers with a unified environment for regulon analysis across multiple genomes [15].

Experimental Protocol: Known PWM-Based Regulon Reconstruction

Input Preparation: Select a group of up to 15 taxonomically related prokaryotic genomes from the MicrobesOnline database available within RegPredict [15].

Motif Selection: Choose a Position Weight Matrix (PWM) from the integrated collections, which include manually curated motifs from RegPrecise, literature-based motifs from RegTransBase, or experimentally characterized motifs from RegulonDB [15].

Genome Scanning: Execute genome-wide scanning using the selected PWM to identify candidate TFBSs in upstream regions of operons. The scoring threshold can be adjusted based on the desired sensitivity [15].

CRON Construction: Allow the system to automatically construct CRONs by:

- Linking orthologous operons with candidate TFBSs

- Extending clusters by adding orthologous operons lacking candidate TFBSs

- Prioritizing CRONs based on conservation level and site scores [15]

Manual Curation: Use the interactive web interface to evaluate each CRON, examining genomic context and functional information from integrated resources before accepting CRONs into the final regulon model [15].

Regulon Generation: Combine all accepted CRONs for the TFBS motif to generate the reconstructed TF regulon for the target genome group [15].

Experimental Protocol: De Novo Regulon Inference

Training Set Definition: Create a set of potentially co-regulated genes using one of four approaches: (i) genes comprising a functional pathway, (ii) genes homologous to regulons from model organisms, (iii) genes from chromosomal loci containing orthologous TF genes, or (iv) genes with similar expression profiles from microarray data [15].

Motif Discovery: Apply the Discover Profile tool (implementing a MEME-like iterative algorithm) to identify candidate TFBS motifs within upstream regions of training set genes [15].

PWM Construction: Build initial PWM profiles from identified motifs, with options for different motif types including palindromes and direct repeats [15].

Iterative Refinement: Perform cycles of genome scanning and profile refinement to expand the regulon beyond the initial training set, maximizing coverage and consistency [15].

CGB: A Flexible Platform for Comparative Genomics

Application Notes: CGB introduces several conceptual advances in comparative genomics of prokaryotic regulons, including a gene-centered framework rather than the traditional operon-centered approach, which accommodates frequent operon reorganization in evolution [23] [19]. The platform employs a novel Bayesian probabilistic framework for estimating posterior probabilities of regulation, providing easily interpretable and comparable scores across species [23] [19]. Unlike other tools that rely on precomputed databases, CGB has minimal external dependencies and can work with both complete and draft genomic data, offering unprecedented flexibility for analyzing newly sequenced bacterial clades [23] [19]. The automated integration of experimental information from multiple sources using phylogenetic weighting further enhances its utility for studying regulatory network evolution [23].

Experimental Protocol: Gene-Centered Regulon Reconstruction

Input Configuration: Prepare a JSON-formatted input file containing:

Orthology Detection: Identify orthologs of reference TFs in each target genome using the provided accessions [23].

Phylogenetic Analysis: Generate a phylogenetic tree of reference and target TF orthologs to estimate evolutionary distances [23] [19].

Species-Specific PWM Generation: Create weighted mixture PWMs for each target species using the inferred phylogenetic distances, following the CLUSTALW weighting approach [23] [19].

Operon Prediction and Promoter Definition: Predict operons in each target species and extract promoter regions based on average intergenic distance (default: 250bp) [23].

Promoter Scoring: Calculate position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) scores for all positions in promoter regions, combining forward and reverse strand scores using the formula:

( PSSM(si) = \log2(2^{PSSM(si^f)} + 2^{PSSM(si^r)}) ) [23] [19]

Probability Estimation: Compute posterior probabilities of regulation for each promoter using the Bayesian framework:

Ancestral State Reconstruction: Estimate aggregate regulation probabilities for orthologous gene groups across species using ancestral state reconstruction methods [23].

RegPrecise: A Database of Curated Genomic Inferences

Application Notes: RegPrecise serves as a knowledge base for capturing, visualizing, and analyzing predicted transcription factor regulons in prokaryotes that have been reconstructed through comparative genomics and manual curation [22] [24]. The database employs a hierarchical data structure organized at three levels: individual regulons (genes co-regulated in a specific genome), regulogs (orthologous regulons across related genomes), and collections of regulogs grouped by taxonomy, TF family, or biological pathway [22] [24]. This organization enables multiple analytical perspectives, from studying the conservation of specific regulons across bacterial lineages to exploring the entire transcriptional regulatory network of a particular species [22]. RegPrecise 3.0 significantly expanded its content to include over 781 TF regulogs across more than 160 genomes representing 14 taxonomic groups of Bacteria, plus nearly 400 regulogs operated by RNA regulatory elements [24].

Experimental Protocol: Database-Driven Regulon Analysis

Data Access: Navigate to the RegPrecise web portal (http://regprecise.lbl.gov) and select the appropriate data section based on your analysis goals [22] [24].

Taxonomy-Focused Exploration:

Transcription Factor-Focused Exploration:

- Select a TF family or specific TF of interest

- Compare reconstructed regulogs for orthologous TFs across different taxonomic lineages

- Analyze variations in regulon content and TFBS motifs across evolutionary distances [22]

Pathway-Focused Exploration:

Data Integration:

- Use the reference regulons as training sets for novel predictions

- Apply the web services API for programmatic access to regulatory data

- Download regulatory interactions for integration with metabolic models [24]

Table 2: RegPrecise Database Content and Statistics

| Database Section | Number of Regulogs | Number of Genomes | Taxonomic Coverage | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TF Regulatory Collections | 781 | >160 | 14 taxonomic groups | Position weight matrices, regulated genes, TFBS alignments [24] |

| RNA Regulatory Collections | ~400 | 24 bacterial lineages | Multiple bacterial phyla | Riboswitch motifs, RNA regulatory sites [24] |

| TF-Specific Collections | 40 | >30 taxonomic lineages | Cross-phylum comparisons | Evolution of regulons for orthologous TFs [22] [24] |

| Propagated Regulons | >1500 (estimated) | 640 | Broad bacterial coverage | Automatically propagated from reference regulons [24] |

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in Regulon Analysis | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | MicrobesOnline [15] | Provides genomic sequences, ortholog predictions, and operon structures | http://microbesonline.org |

| Regulatory Databases | RegTransBase [15], RegulonDB [15], DBTBS [24] | Source of experimentally validated TF-binding sites and regulatory interactions | http://regtransbase.lbl.gov, http://regulondb.ccg.unam.mx |

| Motif Discovery Tools | MEME [15], SignalX [15] | Identify novel DNA motifs from sets of co-regulated genes | http://meme-suite.org |

| Sequence Analysis Tools | Infernal [24] | Detection of RNA regulatory elements using covariance models | http://eddylab.org/infernal |

| Orthology Resources | EggNOG [8], Protein accession mappings [23] | Identification of orthologous genes across genomes | http://eggnog5.embl.de, http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein |

| Programming Environments | Python, R | Implementation of custom analysis scripts and Bayesian frameworks | http://python.org, http://r-project.org |

Workflow Integration and Comparative Analysis

The integration of these platforms creates a powerful pipeline for comprehensive regulon reconstruction, beginning with de novo prediction in RegPredict, progressing through probabilistic validation in CGB, and culminating in database curation and visualization in RegPrecise [15] [23] [24]. This integrated approach addresses the complete lifecycle of regulatory network inference, from initial discovery to comparative analysis and knowledge dissemination.

The complementary strengths of these platforms address different aspects of the regulon reconstruction challenge. RegPredict excels in initial motif discovery and comparative analysis across small to medium-sized taxonomic groups [15]. CGB provides sophisticated probabilistic frameworks for cross-species analysis and evolutionary inference, particularly valuable for studying regulatory network evolution [23] [19]. RegPrecise serves as a repository and visualization platform for accumulating and disseminating curated regulatory annotations [22] [24]. Together, they enable researchers to move from genomic sequences to predictive models of transcriptional regulation, supporting advances in microbial ecology, metabolic engineering, and understanding of bacterial pathogenesis.

The continued development and integration of these platforms represents a critical step toward comprehensive genome-scale annotation of regulatory networks across the bacterial domain. As sequencing technologies make microbial genomes increasingly accessible, these computational resources provide the necessary framework for converting sequence data into predictive models of transcriptional regulation that can guide experimental validation and hypothesis generation [24] [8].

Gene-Centered vs. Operon-Centered Approaches in Modern Analysis

Transcriptional regulon reconstruction is a cornerstone of prokaryotic comparative genomics, fundamental to understanding bacterial physiology, host-pathogen interactions, and antimicrobial resistance [25] [19]. A critical methodological consideration is the choice of the fundamental unit of analysis: the individual gene or the multi-gene operon. Gene-centered approaches treat each gene as an independent regulatory unit, while operon-centered methods analyze groups of co-transcribed genes as a single entity [19] [26]. The strategic selection between these frameworks significantly impacts the prediction accuracy, biological interpretability, and evolutionary insights derived from comparative genomic analyses. This Application Note delineates the technical specifications, experimental protocols, and practical applications of both approaches within the context of prokaryotic regulon reconstruction, providing researchers with a structured framework for methodological selection and implementation.

Conceptual and Technical Comparison

Operons, co-transcribed groups of functionally related genes, represent a fundamental organizational principle in prokaryotic genomes, with approximately 50-60% of bacterial genes organized in such structures [27] [26]. This organization ensures coordinated expression but undergoes frequent evolutionary reorganization through operon splitting, fusion, and gene rearrangement [27] [26]. These dynamic evolutionary processes present significant challenges for purely operon-centered comparative approaches.

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between Analytical Approaches

| Feature | Gene-Centered Approach | Operon-Centered Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Unit | Individual gene | Multi-gene operon |

| Handling of Operon Rearrangements | Robust; analyzes regulatory conservation despite genomic reorganization | Limited; relies on conserved operon structure across genomes |

| Regulatory Resolution | High; identifies gene-specific regulation within split operons | Low; assumes uniform regulation across all operon genes |

| Evolutionary Analysis | Trajects regulatory evolution of individual genetic units | Tracks conservation and disintegration of co-regulated gene clusters |

| Comparative Genomics Implementation | Bayesian probabilistic frameworks (e.g., CGB platform) [19] | Conservation of regulatory interactions in orthologous operons (e.g., RegPredict) [15] |

Gene-centered frameworks address these limitations by focusing on the regulatory state of individual genes, treating operons as logical—but not absolute—units of regulation [19]. This approach facilitates tracking regulatory conservation even after operon disintegration, where genes from an ancestral operon may maintain co-regulation through independent promoters under the same transcription factor [19]. The CGB platform exemplifies this methodology, employing a Bayesian framework to compute posterior probabilities of regulation for each gene independently, thereby enabling robust cross-species comparisons despite frequent operon rearrangements [19].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics in Comparative Genomic Studies

| Analysis Metric | Gene-Centered Method | Operon-Centered Method |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity in Divergent Genomes | High (maintains regulatory associations post-operon split) | Reduced (depends on operon structure conservation) |

| False Positive Rate in TFBS Prediction | Lower (integrates evolutionary conservation) | Variable (context-dependent) |

| Computational Framework | Bayesian probability integration [19] | Position Weight Matrix (PWM) scoring [15] |

| Handling of Incomplete Genomes | Effective with draft assemblies [19] | Requires well-annotated, complete genomes |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Gene-Centered Regulon Reconstruction with CGB Platform

Application: Evolution of regulatory networks across taxonomically diverse bacterial species, particularly when analyzing incomplete genome assemblies or genomes with frequent operon rearrangements.

Experimental Workflow:

Input Preparation

- Compile JSON-formatted input file containing:

- NCBI protein accession numbers for reference transcription factor (TF) instances

- Aligned TF-binding sites for each reference TF

- Accession numbers for target genome chromids/contigs

- Configure parameters: promoter region length, phylogenetic weighting method

- Compile JSON-formatted input file containing:

Orthology and Phylogeny Construction

- Identify TF orthologs in target genomes using BLAST-based search

- Construct phylogenetic tree of reference and target TF orthologs

- Generate weighted mixture Position-Specific Weight Matrix (PSWM) for each target species using CLUSTALW-like weighting based on evolutionary distance [19]

Operon Prediction and Promoter Scanning

- Predict operons in each target species using intergenic distance-based algorithm

- Define promoter regions (typically 250bp upstream of translational start sites)

- Scan promoter regions with species-specific PSWM to identify putative TF-binding sites

Bayesian Probability Calculation

- Calculate posterior probability of regulation for each gene using the framework: where R represents regulated promoter, D observed scores, B background distribution [19]

- Estimate background distribution (B) from genome-wide promoter scores

- Model regulated distribution (R) as mixture of background and motif distributions

Comparative Analysis and Ancestral State Reconstruction

- Identify orthologous gene groups across target species

- Estimate aggregate regulation probability using ancestral state reconstruction methods

- Generate hierarchical heatmaps and tree-based visualizations of regulation probabilities

Technical Notes: The gene-centered approach enables analysis of draft genomes and effectively handles horizontal gene transfer events. The Bayesian framework provides intuitively interpretable probabilities of regulation that are directly comparable across species [19].

Protocol 2: Operon-Centered Analysis with RegPredict

Application: High-confidence regulon propagation in well-annotated genomes from closely related species, particularly for pathway-specific regulation analysis.

Experimental Workflow:

Data Integration

- Select target genomes from MicrobesOnline database (up to 15 simultaneously)

- Retrieve pre-computed operon predictions and orthology assignments

- Select Position Weight Matrices (PWMs) from curated databases (RegPrecise, RegTransBase, RegulonDB) [15]

CRON Construction

- Scan upstream regions of all operons with selected PWM

- Identify candidate TF-binding sites above defined score threshold

- Construct Clusters of co-Regulated Orthologous operons (CRONs) by:

- Linking orthologous operons with candidate TF-binding sites

- Evaluating conservation level of regulatory interactions

- Extending clusters to include orthologous operons lacking candidate sites [15]

Comparative Genomics Validation

- Rank CRONs by conservation level (number of genomes with candidate sites)

- Perform functional enrichment analysis of CRON members

- Manually curate regulatory interactions through interactive web interface

Regulon Propagation

- Combine accepted CRONs to reconstruct complete TF regulon

- Export regulatory network in .sif format for visualization

- Annotate regulatory interactions with confidence metrics based on conservation

Technical Notes: The CRON-based approach efficiently handles large regulons for global transcription factors by splitting them into manageable subregulons. The method relies heavily on conservation of operon structure and is most effective in closely related species [15].

Table 3: Computational Tools and Databases for Regulon Reconstruction

| Resource | Type | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGB Platform [19] | Analysis Pipeline | Gene-centered regulon reconstruction | Bayesian probability framework, draft genome compatibility, no precomputed database dependency |

| RegPredict [15] | Web Server | Operon-centered regulon inference | CRON construction, precomputed PWMs, integration with MicrobesOnline |

| CoryneRegNet 7 [28] | Specialized Database | Transcriptional regulatory networks for Corynebacterium | 82,268 regulatory interactions, 228 TRNs, genome-scale transfer from model organisms |

| RegPrecise [15] | Curated Database | Collection of validated regulons | ~11,500 TFBSs, ~400 orthologous TF groups, 350+ prokaryotic genomes |

| MicrobesOnline [15] | Genomic Database | Operon and ortholog predictions | High-quality orthologs based on phylogenetic trees, predicted operons |

| SynGenome [29] | AI-Generated Database | Semantic design of novel functional sequences | 120+ billion base pairs of AI-generated sequences, function-guided design |

Application Case Studies

Case Study 1: Evolution of Type III Secretion System Regulation

Challenge: Track the evolutionary conservation of HrpB-regulated genes across divergent Proteobacteria species with significant operon reorganization.

Gene-Centered Implementation:

- Applied CGB pipeline to reconstruct HrpB regulon across 15 pathogenic Proteobacteria

- Used Bayesian framework to calculate posterior probabilities of regulation for each gene independently

- Identified conserved regulation of key effector genes despite operon splitting in Salmonella strains

- Revealed divergent evolution of regulatory networks through ancestral state reconstruction [19]

Outcome: Successful identification of core conserved regulon members and lineage-specific acquisitions, demonstrating the robustness of gene-centered approaches in tracking regulatory evolution despite operon rearrangements.

Case Study 2: SOS Regulon Discovery in Balneolaeota

Challenge: Characterize the novel SOS regulon in the recently sequenced Balneolaeota phylum with limited experimental data.

Methodology:

- Combined gene-centered and operon-centered approaches

- Initially identified recA and lexA orthologs using gene-centered homology search

- Reconstructed potential operons containing DNA repair genes

- Discovered novel TF-binding motif through comparative analysis of upstream regions [19]

Outcome: Identification and validation of complete SOS regulon, including a previously uncharacterized transcription factor binding motif, showcasing the power of integrated approaches for novel regulon discovery in understudied phyla.

Concluding Recommendations

The selection between gene-centered and operon-centered approaches should be guided by specific research objectives and genomic context. Gene-centered methods are particularly advantageous for analyses spanning evolutionarily divergent species, genomes with frequent operon rearrangements, and studies utilizing incomplete draft genomes [19]. The Bayesian probabilistic framework implemented in platforms like CGB provides intuitively interpretable results that directly facilitate cross-species comparisons. Operon-centered approaches remain valuable for high-confidence regulon propagation in closely related, well-annotated genomes and for pathway-specific analyses where guilt-by-association principles apply effectively [15] [26]. For comprehensive regulon characterization in non-model organisms, an integrated strategy leveraging the complementary strengths of both approaches yields the most robust and biologically insightful results.

Comparative genomics serves as a powerful methodology for deciphering transcriptional regulatory networks in bacteria, a process known as regulon reconstruction. A regulon encompasses the complete set of genes and operons directly controlled by a single transcription factor (TF). Understanding these networks is essential for insights into bacterial physiology, metabolism, and adaptation [6]. This application note details a protocol for reconstructing amino acid metabolism regulons in Proteobacteria, a phylum of great scientific and medical importance. The process involves identifying conserved transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) across multiple genomes to infer regulon membership and function, providing a cost-effective and scalable alternative to purely experimental methods [6] [30].

Key Concepts and Quantitative Findings

Large-scale comparative genomics studies have successfully mapped extensive regulatory networks across Proteobacteria. One seminal analysis of 33 orthologous TFs across 196 reference genomes from 21 taxonomic groups within Proteobacteria predicted over 10,600 TF binding sites and identified more than 15,600 target genes for 1,896 TFs [6]. The table below summarizes the core quantitative outcomes of such studies.

Table 1: Summary of Large-Scale Regulon Reconstruction Studies in Bacteria

| Study Focus | Number of Genomes Analyzed | Number of Regulons/Regulogs Reconstructed | Key Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Metabolism TFs in Proteobacteria [6] | 196 | 33 orthologous TF groups | >10,600 TFBSs predicted; >15,600 target genes identified |

| Cis-Regulatory RNA Motifs [31] | 255 | 310 regulogs for 43 RNA motif families | ~5,204 RNA sites identified; >12,000 target genes regulated |

| LacI-Family Transcription Factors [11] | 272 | 1,281 regulons | Functional roles and effectors predicted for the majority of studied LacI-TFs |

The evolutionary analysis of reconstructed regulons reveals a common architecture consisting of a core set of target genes conserved across a wide phylogenetic range and an extended set of lineage-specific targets. For instance, the regulon for the methionine metabolism TF MetJ is highly conserved in Gammaproteobacteria, whereas the MetR regulon core is small, with most regulatory interactions being lineage-specific [6]. Similarly, global regulators like FNR-type TFs possess a core regulon for essential functions, which is expanded in different species with genes tailored to their specific ecological niches [32]. This highlights the dynamic nature of regulatory network evolution.

Protocol: Reconstruction of Amino Acid Metabolism Regulons

This protocol outlines the step-by-step process for reconstructing a TF regulon using comparative genomics, based on established methodologies [6] [33] [30].

Stage 1: Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Genome Selection: Compile a set of 10-20 genomes from evolutionarily related Proteobacteria (e.g., from the same family or order). To avoid bias, exclude very closely related strains and species. Genomes can be sourced from public databases like GenBank or MicrobesOnline [6] [11].

- Identification of TF Orthologs: Identify orthologs of the amino acid metabolism TF of interest (e.g., ArgR, TyrR, TrpR for arginine, tyrosine, and tryptophan metabolism, respectively) in the selected genomes. This is typically done using protein BLAST searches with the bidirectional best-hit criterion, followed by validation via phylogenetic analysis [6] [11].

- Data Extraction: For each genome, extract the upstream non-coding regions (typically from -400 to +50 relative to the translation start site) of all coding genes. These sequences will be scanned for conserved regulatory motifs.

Stage 2: Motif Discovery and Positional Weight Matrix (PWM) Construction

- Create a Training Set: Compile a initial training set of likely regulated operons. These can be known targets from model organisms (e.g., E. coli) or operons encoding enzymes for a specific amino acid pathway that are co-localized with the TF gene on the chromosome [6] [33].

- Identify Conserved Motif: Use an iterative motif detection algorithm, such as the one implemented in the RegPredict web server, on the upstream sequences of the training set to identify a common, conserved DNA motif [6] [33] [30].

- Build a PWM: Convert the aligned binding sites into a Positional Weight Matrix (PWM), which quantifies the probability of finding each nucleotide at every position in the binding site. The PWM serves as a quantitative model of the TF's binding specificity [6] [30].

Stage 3: Genomic Scanning and Regulon Prediction

- Scan Genomic Sequences: Use the constructed PWM to scan the upstream regions of all genes in the analyzed genomes. Calculate a score for each potential site based on its similarity to the PWM [6] [19].

- Set a Threshold: Define a score threshold for site prediction, often based on the lowest score observed in the initial training set [33] [30].