Position-Specific Weight Matrices: From Theory to Practice in Prokaryotic Promoter Prediction

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of position-specific weight matrices (PWMs) and their application in predicting prokaryotic promoters.

Position-Specific Weight Matrices: From Theory to Practice in Prokaryotic Promoter Prediction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of position-specific weight matrices (PWMs) and their application in predicting prokaryotic promoters. It covers the foundational principles of PWM construction, from early frequency matrices to modern optimization techniques. The methodological section details the operational workflow for practical application, while the troubleshooting segment addresses common challenges like false positives and presents optimization strategies, including dinucleotide models and algorithm selection. Finally, the article offers a critical validation of current tools through independent benchmarking, comparing the performance of popular resources like BPROM, iPro70-FMWin, and CNNProm. Aimed at researchers and bioinformaticians in genomics and drug development, this review serves as a practical guide for selecting, applying, and optimizing PWM-based methods for accurate promoter identification in bacterial genomes.

The Building Blocks: Understanding PWM Fundamentals and Core Promoter Architecture in Prokaryotes

Within the field of bioinformatics and genomic research, the precise identification of short, degenerate sequence patterns is a fundamental challenge. For research focused on prokaryotic systems, this is particularly critical for predicting promoter regions—the genetic switches that control transcriptional initiation. The position weight matrix (PWM), also known as a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM), has emerged as an indispensable quantitative model for representing these motifs, notably the -10 and -35 hexamers of bacterial promoters [1] [2]. This "Application Notes and Protocols" document provides a detailed framework for constructing and applying PWMs, framing the methodology within the broader objective of enhancing promoter prediction in prokaryotic genomes. We will delineate the step-by-step conversion of raw biological data into a powerful log-odds scoring model, complete with quantitative comparisons and actionable protocols suitable for researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundation: From Biological Sequences to a Quantitative Model

The Hierarchy of Matrix Models

The development of a PWM is a multi-stage process that transforms observed sequence data into a probabilistic scoring system. This workflow progresses through three key stages [3] [2]:

- Position Frequency Matrix (PFM): This is the most fundamental representation, derived directly from a multiple sequence alignment of confirmed functional sites (e.g., aligned -10 box sequences from E. coli σ70 promoters). A PFM is a table of counts, where each element $x_{i,j}$ contains the frequency of nucleotide $i$ (A, C, G, T) at position $j$ of the motif [3] [4].

- Position Probability Matrix (PPM): The PFM is converted into a PPM by normalizing the counts at each position by the total number of sequences ($N$). This provides the probability $M{k,j}$ of observing nucleotide $k$ at position $j$. Pseudocounts are often added at this stage to prevent probabilities of zero and to correct for small sample sizes [3] [4]. The probability is calculated as: $M{k,j}= \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} I(X{i,j}=k)$ where $I$ is an indicator function that is 1 when the nucleotide at position $j$ in sequence $i$ is $k$ [3].

- Position Weight Matrix (PWM): The final step involves converting the PPM into a log-odds score matrix. Each element of the PWM is calculated as the logarithm (base 2 is conventional) of the ratio of the position-specific probability to the background probability of that nucleotide [3] [5]: $PWM{k,j} = \log2(\frac{M{k,j}}{bk})$ Here, $b_k$ is the background frequency of nucleotide $k$. A positive score indicates a nucleotide is more likely at that position in the motif than by random chance, while a negative score indicates it is less likely [3].

The Role of Pseudocounts and Background Models

The application of pseudocounts, or Laplace estimators, is a critical step in PPM construction to avoid overfitting, especially with limited data. Pseudocounts are added to the observed frequencies before normalization, effectively acting as a prior in a Bayesian framework [3] [4]. A common approach is to use a square root function, such as adding $\sqrt{N} * 1/4$ for each nucleotide, though methods vary [4].

The choice of background model ($b_k$) significantly influences the PWM. While a uniform background (0.25 for each nucleotide) is simple, using the genomic GC-content or the specific nucleotide frequencies of the organism being studied provides a more realistic null model and improves prediction accuracy [3] [5]. For GC-rich prokaryotes, this adjustment is essential to avoid a high false-positive rate in promoter scanning.

Scoring a Sequence with a PWM

The power of a PWM lies in its ability to assign a quantitative score to any candidate DNA sequence. For a given sequence $S$ of length $L$, the score is calculated by summing the PWM values corresponding to the nucleotide at each position [3] [5]:

$PWMS(S) = \sum{j=1}^{L} PWM{S_j, j}$

This score is a log-odds score, representing the likelihood that the sequence $S$ is a genuine instance of the motif versus being a random genomic segment. A score greater than 0 suggests the sequence is more likely to be a functional site [3]. The score can be interpreted as the binding energy for a transcription factor to that specific sequence, providing a physical basis for the model [3].

Results & Data Presentation

Workflow Visualization: PFM to PWM

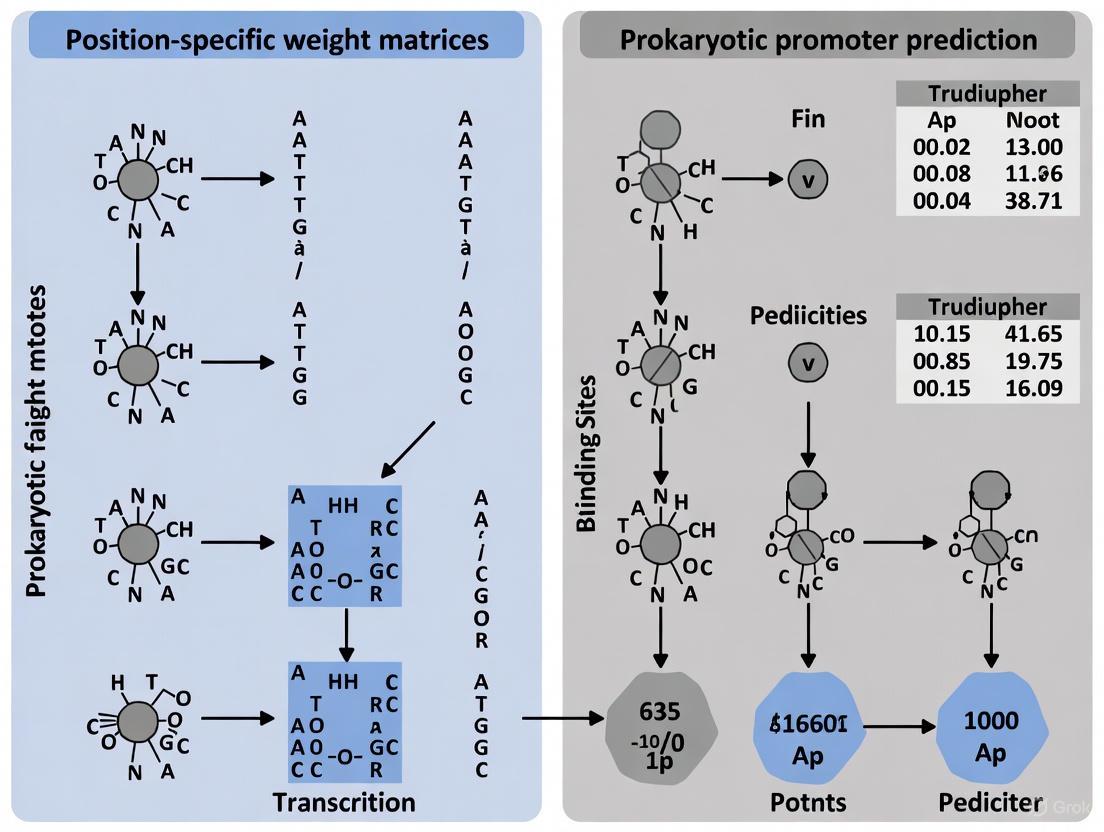

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow for constructing a Position Weight Matrix and using it to score sequences.

Quantitative Example: Constructing a PWM

To demonstrate the process, consider a simplified example derived from a set of aligned DNA sequences [3].

Table 1: Example Position Frequency Matrix (PFM). This matrix shows raw nucleotide counts from 10 aligned sequences of length 9.

| Position | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| C | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| G | 1 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| T | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

Table 2: Derived Position Probability Matrix (PPM) with Pseudocounts. The PFM is normalized and pseudocounts (a total of 1 'pseudo-sequence' distributed evenly) are added to avoid zero probabilities.

| Position | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| C | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| G | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.94 | 0.02 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| T | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.94 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

Table 3: Final Position Weight Matrix (PWM). The PPM is converted to log-odds scores using a uniform background frequency (0.25 for each nucleotide). Scores are in bits.

| Position | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.26 | 1.26 | -1.32 | -3.64 | -3.64 | 1.26 | 1.49 | -0.32 | -1.32 |

| C | -0.32 | -0.32 | -1.32 | -3.64 | -3.64 | -0.32 | -1.32 | -1.32 | -0.32 |

| G | -1.32 | -1.32 | 1.49 | 1.91 | -3.64 | -1.32 | -1.32 | 1.00 | -1.32 |

| T | 0.68 | -1.32 | -1.32 | -3.64 | 1.91 | -1.32 | -1.32 | -0.32 | 1.26 |

Sequence Scoring and Threshold Determination

Using the PWM from Table 3, the score for a test sequence, S = GAGGTAAAC, is calculated by summing the values for G at pos1, A at pos2, etc. [3]:

p(S|M) = -1.32 + 1.26 + 1.49 + 1.91 + 1.91 + 1.26 + 1.49 + -0.32 + -1.32 = 6.36

This positive score indicates the sequence is a good match to the motif. The significance of individual PWM scores is typically evaluated by comparing them to an extreme value distribution of scores from random sequences, or by setting a threshold based on the desired balance between sensitivity and specificity [5]. For prokaryotic promoter prediction, thresholds are often set to retain a manageable number of high-confidence hits given the large search space.

Protocol: Building and Applying a PWM for Prokaryotic Promoter Prediction

Protocol Workflow Visualization

The following diagram outlines the end-to-end experimental and computational protocol for building a PWM and applying it to genome-wide promoter prediction.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Curate a High-Quality Training Set

- Objective: Collect a non-redundant set of experimentally validated promoter sequences for the prokaryotic sigma factor of interest (e.g., σ70 in E. coli).

- Procedure:

- Source data from dedicated databases like RegulonDB or from primary literature.

- Extract sequences containing the core promoter elements (e.g., from -50 to +10 relative to the transcription start site).

- Manually curate or use computational tools (e.g., MEME, Clustal Omega) to create a multiple sequence alignment focused on the -10 and -35 regions.

- Notes: The quality and size of the training set directly determine the predictive power of the resulting PWM. A common minimum is 20-30 confirmed sites.

Step 2: Construct the Position Frequency Matrix (PFM)

- Objective: Convert the aligned sequences into a quantitative count matrix.

- Procedure:

- For each position (j) in the alignment, count the occurrences of A, C, G, and T.

- Record these counts in a 4 x L matrix, where L is the length of the aligned motif. This is your PFM (see Table 1).

Step 3: Convert PFM to Position Weight Matrix (PWM)

- Objective: Transform the PFM into a log-odds scoring matrix.

- Procedure:

- Add Pseudocounts: To each count in the PFM, add a pseudocount. A widely used method is:

Adjusted_Count = Observed_Count + sqrt(N) * (1/4), where N is the number of sequences [4]. - Create PPM: Normalize the adjusted counts at each position so they sum to 1.0. This creates the PPM (see Table 2).

- Calculate Log-Odds: For each probability (p{i,j}) in the PPM, compute the PWM value:

PWM_{i,j} = log2( p_{i,j} / b_i ), where (bi) is the background frequency of nucleotide (i). Use the genomic nucleotide frequencies for the target organism for (b_i) [3] [5]. The result is the final PWM (see Table 3).

- Add Pseudocounts: To each count in the PFM, add a pseudocount. A widely used method is:

Step 4: Scan Genomic Sequences

- Objective: Identify putative promoter sites in a prokaryotic genome.

- Procedure:

- Notes: The output is a list of genomic coordinates and scores for all windows scoring above a user-defined threshold.

Step 5: Evaluate and Filter Predictions

- Objective: Reduce false positives and identify biologically relevant hits.

- Procedure:

- Set a Score Threshold: Determine a threshold based on the score distribution of known sites or by controlling the false discovery rate (FDR) [5].

- Incorporate Genomic Context: Filter hits based on their location. True promoters are typically found in intergenic regions upstream of coding sequences.

- Leverage Comparative Genomics: Check for conservation of high-scoring sites in related species, as functional elements are often under evolutionary constraint.

- Consider Clustering: Some regulatory systems involve multiple, clustered TF binding sites. The presence of additional nearby hits can bolster the credibility of a prediction.

Advanced Applications and Integration

Enhanced Prediction with Contextual Scores

Basic PWM scanning can yield a high number of false positives. Advanced methods like COMMBAT (COnditions for Microbial Metabolite Activated Transcription) have been developed to integrate PWM-derived interaction scores with additional biological context for more accurate prediction, especially in complex regions like bacterial biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [7].

COMMBAT generates a composite score (C) by combining a normalized interaction score (I) from the PWM with a target score (T) that incorporates genomic region (R) and gene function (F) information: C = I + T, where T = R + F [7]. This approach prioritizes PWM hits that are located near promoter regions and that regulate functionally important BGC genes.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for PWM-Based Analysis

| Item Name | Type/Source | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Promoter Datasets (e.g., RegulonDB) | Biological Database | Provides experimentally validated sequences for Step 1 (Training Set Curation). |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tool (e.g., Clustal Omega, MEME) | Software | Aligns core promoter motifs for precise PFM construction in Step 2. |

| PWM Scanning Software (e.g., Patser, PWMScan, GimmeMotifs) | Software/Web Server | Executes Step 4 (Genome Scanning) using the constructed PWM to identify putative sites. |

| PWM/PFM Databases (e.g., JASPAR, RegulonDB, FlyFactorSurvey) | Biological Database | Source of pre-built matrices for specific TFs, bypassing Steps 1-3 if a validated model exists. |

| Genomic Sequence FASTA File | Biological Data | The target genome or sequence regions to be scanned in Step 4. |

| Background Nucleotide Frequencies | Calculated Data | Essential parameter for log-odds calculation in Step 3. Can be genome-wide or sequence-specific. |

Discussion

The position weight matrix remains a cornerstone of computational motif detection due to its simplicity, interpretability, and strong statistical foundation. Within prokaryotic promoter prediction, PWMs provide a direct method to quantify the sequence specificity of sigma factors and other transcription factors [1] [2]. However, users must be cognizant of its limitations, primarily the assumption of position independence, which ignores correlations between nucleotides at different positions. Furthermore, the challenge of the "futility theorem"—the overwhelming number of false positives generated when scanning large genomes—necessitates the integration of additional layers of evidence, such as evolutionary conservation, genomic context, and functional genomics data [2].

The development of tools like COMMBAT demonstrates the future direction of the field: moving beyond pure sequence-similarity scoring to integrative models that incorporate the rich biological context in which regulatory elements operate [7]. For drug development professionals, this enhanced accuracy is critical for identifying novel regulatory nodes in bacterial pathogens that could be targeted for therapeutic intervention. By adhering to the detailed protocols and considerations outlined in this document, researchers can robustly apply PWM methodology to advance their studies in prokaryotic genomics and transcriptional regulation.

In prokaryotes, the initiation of transcription is a tightly regulated process centered on the promoter region, a specific DNA sequence recognized by the RNA polymerase (RNAP) holoenzyme. The specificity of this interaction is conferred by sigma (σ) factors, which direct the core RNAP to specific promoter elements, primarily the -10 box (Pribnow box) and the -35 box. The precise sequence and spacing of these elements are critical for binding affinity and transcription efficiency. This foundational biology is the cornerstone for developing computational predictive models, such as Position-Specific Weight Matrices (PSWMs), which quantify the likelihood of a DNA sequence functioning as a promoter. Accurate prediction is vital for annotating genomes, understanding regulatory networks, and identifying novel drug targets in pathogenic bacteria.

Core Promoter Elements and Their Consensus

Sigma factors recognize specific consensus sequences at the -10 and -35 positions relative to the transcription start site (+1). The strength of a promoter is often correlated with its similarity to these consensus sequences.

Table 1: Consensus Elements for Primary Sigma Factors in E. coli

| Sigma Factor | Function / Regulon | -35 Consensus | Spacing (bp) | -10 Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σâ·â° (RpoD) | Housekeeping genes | TTGACA | 16-18 | TATAAT |

| σ³² (RpoH) | Heat shock response | TCTCNCCCTTGAA | 13-15 | CCCCATNTA |

| σâµâ´ (RpoN) | Nitrogen metabolism | CTGGNA | 6 | TTGCA |

| σᴾᴼ (RpoS) | Stationary phase stress | TTGACA* | 16-18 | TATAAT* |

Note: σᴾᴼ promoters are highly diverse and often lack a strong -35 box, relying on other elements for recognition.

Table 2: Information Content (Bits) in Consensus Elements

The information content (IC) at each position of a consensus element quantifies its conservation, with higher bits indicating greater importance for recognition. This data is the direct input for building PSWMs.

| Position | σâ·â° -35 Box (IC in bits) | σâ·â° -10 Box (IC in bits) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.52 (T) | 1.89 (T) |

| 2 | 1.23 (T) | 1.95 (A) |

| 3 | 1.45 (G) | 1.52 (T) |

| 4 | 1.60 (A) | 1.84 (A) |

| 5 | 1.33 (C) | 1.45 (A) |

| 6 | 1.48 (A) | 1.21 (T) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: DNase I Footprinting to Map Sigma Factor Binding Sites

Objective: To identify the precise DNA sequences (including -10 and -35 boxes) protected by the RNAP holoenzyme during promoter complex formation.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- End-Labeling: A DNA fragment containing the putative promoter is amplified by PCR or restriction digest. The 5' or 3' end of one strand is labeled with ³²P using T4 Polynucleotide Kinase.

- Binding Reaction: The labeled DNA fragment is incubated with purified E. coli RNAP holoenzyme (core RNAP + specific σ factor) in a binding buffer (e.g., 40 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/mL BSA) for 20 minutes at 37°C.

- DNase I Digestion: A diluted solution of DNase I is added to the reaction. The concentration and digestion time (typically 1 minute) are empirically determined to achieve, on average, one cleavage per DNA molecule.

- Reaction Quenching: The digestion is stopped by adding a chelating agent (e.g., EDTA) and SDS.

- Precipitation & Denaturation: Proteins are digested with Proteinase K, and nucleic acids are precipitated with ethanol. The pellet is resuspended in formamide loading dye.

- Electrophoresis: Samples are denatured and resolved on a high-resolution, denaturing polyacrylamide gel (6-8%).

- Visualization: The gel is dried and exposed to a phosphorimager screen. A "footprint" or gap in the ladder of cleavage products indicates the region protected by the bound RNAP.

Protocol 2:In VitroTranscription Assay to Validate Promoter Strength

Objective: To quantitatively measure the transcriptional activity driven by a promoter sequence in vitro.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Template Preparation: A linear DNA template containing the promoter of interest upstream of a G-less cassette (a sequence lacking guanines) or a defined open reading frame is purified.

- Transcription Reaction: The DNA template is incubated with purified RNAP holoenzyme in transcription buffer (e.g., 40 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT) containing ATP, CTP, UTP, and a limiting concentration of [α-³²P]CTP (for radiolabeling). To prevent non-specific initiation, heparin may be added as a competitor.

- Initiation & Elongation: The reaction is incubated at 37°C for 20-30 minutes to allow for open complex formation, initiation, and elongation.

- Reaction Termination: The reaction is stopped by adding an equal volume of stop solution (e.g., 95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA).

- Product Analysis: Transcripts are denatured and separated by urea-PAGE. The radiolabeled RNA products are visualized and quantified using a phosphorimager. The intensity of the correct-length transcript is proportional to promoter strength.

Visualizations

Title: Sigma Factor Directs Promoter Recognition

Title: PSWM Construction for Promoter Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Promoter Analysis Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Purified RNAP Holoenzyme | Core enzyme combined with a specific sigma factor (e.g., σâ·â°) for in vitro binding and transcription studies. |

| DNase I (RNase-free) | Enzyme used in footprinting assays to cleave DNA not protected by a bound protein. |

| [γ-³²P] ATP | Radioactive ATP used by T4 Polynucleotide Kinase to end-label DNA fragments for visualization in footprinting assays. |

| T4 Polynucleotide Kinase | Enzyme that transfers the gamma-phosphate of ATP to the 5'-end of DNA, facilitating radiolabeling. |

| G-less Cassette Template | A DNA template lacking guanine residues in the non-template strand; allows for specific transcription runoff without the need for GTP in in vitro assays. |

| Heparin | A polyanion used as a competitor in in vitro transcription; it binds free RNAP and prevents re-initiation, simplifying the analysis of single-round transcription. |

| SAR-20347 | SAR-20347|TYK2/JAK1 Inhibitor|For Research Use |

| (S)-Azelastine Hydrochloride | (S)-Azelastine Hydrochloride, CAS:153408-27-6, MF:C22H25Cl2N3O, MW:418.4 g/mol |

The additivity hypothesis is a fundamental assumption in many computational models used for prokaryotic promoter prediction. It posits that the individual nucleotide positions within a transcription factor binding site or promoter element contribute independently to the total binding affinity or activity. This means the contribution of any base at a given position does not depend on the identity of bases at other positions within the motif. This assumption of statistical independence enables the construction of simple, interpretable models known as position weight matrices (PWMs), which have become a standard tool in computational biology for identifying regulatory elements in genomic sequences [3].

In the context of prokaryotic promoter research, the additivity hypothesis provides the mathematical foundation for treating a binding site as a series of independent multinomial distributions—one for each position in the motif. This allows the probability of any given sequence to be calculated by simply multiplying the probabilities of each constituent nucleotide at their respective positions. Similarly, the overall binding score is computed as the sum of position-specific scores, creating a computationally efficient framework for scanning large genomic regions [3]. Despite ongoing debates about its biological accuracy, this additive model remains widely employed due to its simplicity, interpretability, and reasonable performance across many applications.

Theoretical Foundation of Positional Independence

Mathematical Formulation of Independence

The additivity hypothesis in promoter modeling is rooted in the mathematical definition of statistical independence derived from probability theory. Two events, A and B, are considered independent if the probability of their joint occurrence equals the product of their individual probabilities: P(A∩B) = P(A)P(B) [8]. In the context of sequence modeling, this translates to assuming that the probability of observing a specific nucleotide at position i is independent of the nucleotides observed at all other positions j≠i within the binding site.

For a sequence S of length l, where S = sâ‚, sâ‚‚, ..., sâ‚—, the probability of S given the model M is calculated as: p(S|M) = âˆáµ¢ p(sáµ¢|M) where p(sáµ¢|M) represents the probability of observing nucleotide sáµ¢ at position i in the motif [3]. This multiplicative relationship forms the core of the additivity assumption and enables the straightforward computation of sequence probabilities under the model.

From Position Frequency Matrices to Position Weight Matrices

The practical implementation of the additivity hypothesis begins with the construction of a position frequency matrix (PFM). A PFM is created by counting the occurrences of each nucleotide at each position in a set of aligned binding sites. The PFM is then normalized to create a position probability matrix (PPM), where each entry represents the probability of observing a specific nucleotide at a particular position [3].

To create a position weight matrix (PWM) used for scoring, log-odds weights are typically applied. Each element in the PWM is calculated as: Mâ‚–,â±¼ = logâ‚‚(Mâ‚–,â±¼/bâ‚–) where Mâ‚–,â±¼ is the probability of nucleotide k at position j in the PPM, and bâ‚– is the background frequency of nucleotide k [3]. This transformation enables additive scoring of sequences, where the score for a candidate sequence is simply the sum of the corresponding weights from the PWM.

Table 1: Evolution of Matrix Models from Sequence Alignment

| Matrix Type | Description | Calculation | Parameters for Length l |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position Frequency Matrix (PFM) | Raw counts of nucleotides at each position | Count occurrences in aligned sequences | 4 × l |

| Position Probability Matrix (PPM) | Normalized probabilities | PFM column / number of sequences | 4 × l |

| Position Weight Matrix (PWM) | Log-odds scores for scoring | log₂(PPM entry / background frequency) | 4 × l |

Experimental Validation Protocols

Protocol 1: Testing the Additivity Assumption via Binding Affinity Measurements

Purpose: To experimentally validate whether positions in a transcription factor binding site contribute independently to binding affinity.

Materials:

- Purified transcription factor protein

- DNA library containing all possible base variations at target positions

- Binding affinity measurement system (e.g., EMSA, SPR, or microarray)

- Buffer components for binding reactions

Procedure:

- Design DNA Targets: Create a comprehensive set of DNA oligonucleotides that systematically vary at the positions of interest. For testing two positions, include all 16 possible dinucleotide combinations.

- Measure Binding Affinities: Determine the association constant (Kâ‚) for each sequence variant using your selected methodology. For protein-binding microarrays, follow the protocol of Bulyk et al. where proteins are displayed on phage and bound directly to double-stranded DNA microarrays [9].

- Convert to Probabilities: Normalize the Kâ‚ values to probabilities of binding using the equation: P(Nâ‚– | A) = [Kâ‚(Nâ‚–, A)]/[Σ Kâ‚(Nₖ′, A)] where the denominator is the partition function (sum of Kâ‚ over all sequence variants) [9].

- Calculate Best Additive Model (BAM): Compute the mononucleotide BAM by summing probabilities for sequences sharing bases at each position. For example, the parameter for A at position 1 is the sum of probabilities of all sequences of the form ANN [9].

- Compare Predictions: Calculate the predicted probabilities under the additive model by multiplying the position-specific probabilities. Compare these with measured values using correlation analysis.

- Statistical Analysis: Compute correlation coefficients between measured binding probabilities and additive model predictions. High correlations support the additivity hypothesis, while significant deviations suggest positional interdependence [9].

Troubleshooting:

- If correlation coefficients are low, consider dinucleotide models that account for dependencies between adjacent positions.

- Ensure binding measurements are performed under equilibrium conditions for accurate Kâ‚ determination.

- Include sufficient replicates to account for experimental variability (e.g., 9 replicates as in Bulyk et al. study) [9].

Protocol 2: Computational Assessment Using Promoter Sequence Analysis

Purpose: To evaluate the additivity hypothesis by comparing the performance of mononucleotide versus dinucleotide PWM models.

Materials:

- Curated set of experimentally verified promoter sequences

- Background genomic sequences for comparison

- Computational resources for matrix construction and evaluation

- Programming environment (e.g., Python, R) with appropriate bioinformatics libraries

Procedure:

- Data Compilation: Collect a non-redundant set of experimentally verified promoter sequences, such as 1871 human promoter sequences from the Eukaryotic Promoter Database (EPD) used in studies of GC-box elements [10].

- Construct Mononucleotide PWM: Build a standard 4-row PWM using the Staden-Bucher approach: wᵦᵢ = ln(nᵦᵢ/(eᵦᵢ + sᵢ)) + cᵢ where nᵦᵢ is the number of times base b occurs at position i, eᵦᵢ is the expected frequency, sᵢ is a smoothing parameter, and cᵢ is a constant [10].

- Construct Dinucleotide PWM: Build a 16-row dinucleotide matrix using the same methodology but counting dinucleotide occurrences instead of single nucleotides [10].

- Performance Evaluation: Scan promoter sequences and control sequences (e.g., random or non-promoter genomic regions) with both models using an appropriate score threshold.

- Calculate Metrics: Determine sensitivity (ability to find true binding sites) and specificity (ability to reject non-binding sites) for both models.

- Compare Models: Assess whether the dinucleotide model provides statistically significant improvement over the mononucleotide model using metrics like correlation coefficient or area under the ROC curve.

Validation:

- Use independent test sets not used during model construction

- Compare with experimentally validated binding sites from databases like TRANSFAC

- Perform statistical significance testing on performance differences

Quantitative Evidence and Data Analysis

Correlation Analysis of Additive Model Performance

Experimental studies have quantitatively assessed the validity of the additivity hypothesis by comparing measured binding affinities with predictions from additive models. Research on protein-DNA interactions has revealed that while the additivity assumption does not fit experimental data perfectly, it often provides a remarkably good approximation.

Table 2: Correlation Coefficients Between Measured Binding Affinities and Additive Model Predictions for Zif268 Variants

| Zif268 Protein Variant | Mononucleotide Model (123) | Dinucleotide Model (12*3) | Dinucleotide Model (1*23) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 0.973 | 0.986 | 0.987 |

| RGPD | 0.883 | 0.942 | 0.941 |

| REDV | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| LRHN | 0.927 | 0.978 | 0.956 |

| KASN | 0.695 | 0.791 | 0.718 |

Data derived from binding affinity measurements to all 64 possible trinucleotide targets shows consistently high correlation coefficients for most protein variants, supporting the utility of additive models. The wild-type protein exhibits a correlation of 0.973 with the mononucleotide model, improving only marginally with dinucleotide models (0.986-0.987). The REDV variant shows nearly perfect correlation (0.999) with all models, while the KASN variant shows the lowest correlation (0.695), suggesting potential position interdependence in certain contexts [9].

Extended Thermodynamic Models Incorporating Non-additive Effects

Recent research has developed extended thermodynamic models that move beyond strict additivity to better predict promoter function from random sequences. These models incorporate six essential structural features of bacterial promoters not present in standard additive models:

- Multiple binding configurations allowing σâ·â°-RNAP to bind in different orientations that cumulatively contribute to expression

- Spacer length flexibility with energy penalties for suboptimal distances between -10 and -35 elements

- Occlusive unproductive binding that blocks productive transcription

- Reverse complement binding that inhibits productive binding at the promoter

- Dinucleotide interactions between promoter nucleotides in direct contact with σâ·â°-RNAP

- Clearance rate of RNAP from the promoter [11]

Experimental validation using mutant libraries of bacteriophage Lambda PR promoter containing >12,000 constitutively expressed random mutants demonstrated that the extended model significantly outperformed the standard additive model in predicting gene expression levels. Both models were trained on a subset of the library and evaluated on held-out test sequences, with the extended model showing superior performance despite the increased parameter complexity [11].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Additivity Hypothesis Investigation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Systems | Protein-binding microarrays, EMSA kits, Surface Plasmon Resonance | Measurement of binding affinities for comprehensive sequence variants |

| DNA Libraries | All possible dinucleotide variants (16), All possible trinucleotide variants (64) | Comprehensive testing of positional effects and interactions |

| Computational Databases | TRANSFAC, Eukaryotic Promoter Database (EPD), Database of Transcriptional Start Sites (DBTSS) | Source of validated binding sites and promoter sequences for model training |

| Software Tools | MATCH algorithm, Possumsearch, Gibbs sampling algorithms | PWM-based scanning of genomic sequences and motif discovery |

| Statistical Frameworks | Correlation analysis, Weighted multinomial logistic regression, ROC curve analysis | Quantitative evaluation of model performance and additivity validation |

Advanced Computational Implementation

Algorithm for Improved PWM Construction

The Staden-Bucher approach provides a foundation for PWM construction, with recent modifications enhancing performance for promoter prediction:

This algorithm incorporates smoothing parameters to handle limited data situations and prevents the logarithm of zero, which is particularly important when working with the limited number of known binding sites available for many prokaryotic transcription factors [10].

Workflow for Comprehensive Model Evaluation

Implications for Prokaryotic Promoter Prediction Research

The additivity hypothesis, despite its limitations, continues to provide a valuable foundation for prokaryotic promoter prediction. The high correlation coefficients observed between additive model predictions and experimental measurements across multiple transcription factors suggest that positional independence serves as a reasonable first-order approximation for many protein-DNA interactions. However, evidence from both biological experiments and computational studies indicates that incorporating specific types of positional dependencies, particularly between adjacent nucleotides, can yield meaningful improvements in model accuracy.

For researchers focused on prokaryotic systems, the practical implication is that standard PWM approaches based on the additivity hypothesis remain useful for initial promoter scanning and analysis. However, when highest accuracy is required—particularly for synthetic biology applications or evolutionary studies—extended models that account for dinucleotide interactions and multiple binding configurations should be employed. The pervasiveness of functional σâ·â°-binding sites in random sequences, with an estimated 10-20% of random sequences leading to expression and ~80% of non-expressing sequences being just one mutation away from functionality, underscores the importance of accurate models for understanding promoter evolution and function [11].

The decision between simple additive models and more complex approaches should be guided by the specific research context, considering the trade-off between model complexity, interpretability, and predictive power. For many discovery-level applications in prokaryotic promoter research, additive models implemented through position weight matrices provide an optimal balance of these factors.

Position Weight Matrices (PWMs) are a fundamental model for representing transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) in DNA sequences, serving as a critical tool for predicting regulatory elements like prokaryotic promoters [12] [13]. A PWM provides a quantitative representation of a DNA sequence pattern, where each entry reflects the probability of finding a specific nucleotide at a given position in the binding site. This article provides a detailed overview of public PWM databases and the computational tools available for their application, with a specific focus on resources and protocols for prokaryotic promoter prediction research.

In prokaryotes, promoters are DNA sequences that initiate transcription and typically contain conserved short motifs, such as the Pribnow box (-10 box) and the -35 box [14]. PWMs are exceptionally suited for modeling these sites because they can capture the base preferences at each position, allowing for the scoring of any DNA sequence for its similarity to the known motif. This capability is foundational for computationally identifying promoter regions across entire genomes, a process that is more efficient than labor-intensive biological methods [15]. The accuracy of computational predictions has been steadily increasing, with modern approaches leveraging deep learning models that sometimes outperform traditional machine learning and scoring function-based methods [14].

Catalog of Public PWM Databases and Tools

The following tables summarize key databases and software tools that are instrumental for PWM-based research.

Table 1: Public Databases Relevant for PWM and Prokaryotic Promoter Research

| Database Name | Key Features | Specificity | Last Update |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOOR (Database of Prokaryotic OpeRons) [16] | Contains computationally predicted operons for over 2,000 prokaryotic genomes; includes cis-regulatory motifs. | Prokaryotic | 2014 |

| TRANSFAC [12] | A commercial database with a public version; contains a large collection of PWMs for transcription factors. | Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic | Not Specified |

| RegulonDB [15] | Contains information on the transcriptional regulatory network of Escherichia coli, including promoter sequences. | Prokaryotic (E. coli) | Actively Maintained |

| EPD (Eukaryotic Promoter Database) [13] | A collection of eukaryotic promoters; the associated PWMTools website provides resources for PWM analysis. | Eukaryotic | 2021 (Tools) |

Table 2: Key Software Tools for PWM Scanning and Analysis

| Tool Name | Function | Algorithm Highlights | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOODS (Motif Occurrence Detection Suite) [12] | Fast search for PWM matches in DNA sequences. | Implements advanced online algorithms (e.g., lookahead filtration) for speed. | C++ library, BioPerl/Biopython bindings |

| PWMTools [13] | Web interface for PWM model generation, evaluation, and genome scanning. | Includes PWMTrain, PWMEval, PWMScore, and PWMScan. | Web Server |

| iProEP [14] | Predicts prokaryotic and eukaryotic promoters. | Uses PseKNC and position-correlation scoring function with SVM. | Webserver/Local Tool |

| BPROM [17] | Predicts bacterial promoters. | Not Specified | Web Server |

| PPP (Prokaryotic Promoter Prediction) [17] | Online tool for predicting prokaryotic promoters. | Not Specified | Web Server |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Prokaryotic Promoter Prediction Using PWM Scanning

This protocol details the steps for identifying potential promoter regions in a prokaryotic genome using pre-existing PWMs.

1. Resource Acquisition: - PWM Collection: Obtain PWMs for your transcription factors of interest. For core prokaryotic promoters, this typically involves PWMs for the -10 and -35 boxes. These can be sourced from literature or databases like RegulonDB [15]. - Genomic Sequence: Download the complete genomic sequence of the target prokaryotic organism in FASTA format from a repository like NCBI.

2. Tool Selection and Setup: - Scanner: Select a PWM scanning tool. For high-performance scanning of large genomes, a tool like MOODS is recommended due to its efficient algorithms [12]. Install the software or access the web service.

3. Parameter Configuration: - Score Threshold: Determine an appropriate score threshold for calling a match. This can be set based on a P-value (e.g., 1e-4) which MOODS can convert into a score threshold using a dynamic programming algorithm [12]. - Background Model: Specify the background nucleotide distribution. This can be the default uniform distribution or a model estimated from your target genome for greater accuracy. - Strand Consideration: Ensure the tool is configured to scan both forward and reverse strands of the DNA.

4. Execution: - Run the scanning tool with your genomic sequence and the provided PWMs. For example, using MOODS's multi-matrix lookahead filtration (MLF) algorithm allows for scanning hundreds of PWMs against the genome in a single pass [12].

5. Result Analysis: - The output will typically be a list of genomic coordinates, strands, and scores for each PWM match. - Promoter regions can be inferred by identifying genomic locations where matches for the -10 and -35 box PWMs occur at an appropriate spacing and orientation.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol 2:De NovoPWM Creation from Binding Site Sequences

This protocol describes how to build a PWM de novo from a set of aligned DNA sequences, such as those derived from high-throughput experiments like HT-SELEX.

1. Data Input: - Sequence Alignment: Provide a set of aligned DNA sequences of equal length, known to contain the binding motif.

2. Matrix Construction: - Position Frequency Matrix (PFM): For each position in the alignment, count the occurrence of each nucleotide (A, C, G, T). This forms a PFM. - Add Pseudocounts: Apply a small pseudocount (e.g., +1 to all counts) to avoid probabilities of zero and to account for sampling bias. - Calculate Probabilities: Convert the adjusted counts into probabilities at each position. - Log-Odds Scoring: Convert the probabilities into a log-odds score against a background nucleotide distribution. The score for nucleotide ( i ) at position ( j ) is typically calculated as ( PWM{i,j} = \log2(\frac{p{i,j}}{bi}) ), where ( b_i ) is the background frequency of nucleotide ( i ) [12].

3. Model Evaluation: - Use a tool like PWMEval (part of the PWMTools suite) to assess the predictive performance of your newly created PWM, for instance, by testing its ability to recover binding sites from an independent dataset like ChIP-seq [13].

The logical flow for creating a PWM is as follows:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PWM-Based Analyses

| Item/Resource | Function in Protocol | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PWM Scanning Software | Identifies potential TFBS/promoter locations in a DNA sequence. | MOODS [12] (for high-speed local analysis), PWMTools [13] (web-based suite). |

| Prokaryotic Operon Database | Provides context for predicted promoters within genomic operon structures. | DOOR database [16] offers predicted operons for >2000 prokaryotic genomes. |

| Benchmark Datasets | For training and validating custom promoter prediction models. | Curated sequences from RegulonDB [15] can serve as reliable positive samples. |

| Sequence Alignment Tool | Essential for preparing multiple binding site sequences for de novo PWM creation. | Tools like MEME [17] can be used for motif discovery and alignment. |

| Background Genome Sequence | Provides a null model for calculating log-odds scores in the PWM and for statistical testing. | The genome of the organism under study, or a representative non-coding sequence set. |

Position Weight Matrices (PWMs) have served as a fundamental model for representing transcription factor (TF) binding specificity for decades. A PWM is a model for the binding specificity of a transcription factor and can be used to scan a sequence for the presence of DNA words that are significantly more similar to the PWM than to the background [2]. The model assumes independent contributions from each nucleotide position within the binding site, where the score of a given DNA word is calculated by summing the corresponding matrix elements for each nucleotide at each position [2]. This relatively simple approach has proven valuable for identifying potential transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) in DNA sequences, particularly in prokaryotic and lower eukaryotic organisms with compact genomes. However, the application of simple PWM scanning to complex eukaryotic genomes reveals significant limitations that fundamentally constrain its predictive power.

The core challenge, often termed the "futility theorem" in regulatory genomics, states that a genome-wide scan with a typical PWM could incur in the order of 1000 false hits per functional binding site [18] [2] [19]. This occurs because nearly every gene in a complex genome will have a match to the PWM of nearly every TF when considering sequence alone [2]. This theorem highlights a fundamental limitation: while PWMs can identify sequences with potential binding affinity, they cannot distinguish functionally relevant binding events from the vast background of sequence-compatible but non-functional sites. The problem is particularly acute in metazoan genomes where simple PWM scanning, by itself, is not successful due to short, degenerate motifs distributed across large non-coding regions [2] [19].

The Core Problem: Quantitative Assessment of Limitations

Fundamental Limitations of Simple PWM Models

The limitations of PWM-based approaches stem from both conceptual simplifications in the model and the biological complexity of genomic regulation:

- Independence Assumption: PWMs assume that each nucleotide position contributes independently to binding affinity, ignoring interdependencies between positions that significantly influence TF-DNA interactions [20] [21].

- Lack of Contextual Information: Simple scanning fails to incorporate crucial genomic context including chromatin accessibility, nucleosome positioning, histone modifications, and cooperative interactions with other factors [18] [22].

- Static Representation: PWMs provide a static representation of binding specificity that cannot adapt to cell-type-specific conditions or environmental influences that alter TF binding behavior [22].

Performance Metrics in Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Contexts

The performance disparity of PWM scanning between prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes can be visualized through key quantitative metrics:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of PWM Scanning Across Organisms

| Organism Type | Genome Size | TFBS Length | False Positive Rate | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prokaryotes (e.g., E. coli) | ~4-5 Mbp | 10-20 bp | Moderate | Spacing constraints, accessory elements |

| Unicellular Eukaryotes (e.g., Yeast) | ~12 Mbp | 5-15 bp | High | Compact regulatory regions |

| Complex Eukaryotes (e.g., Human) | ~3 Gbp | 5-15 bp | Very High (≈1000:1 false:true ratio) | Large non-coding regions, chromatin effects |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework of the futility theorem in complex genomes:

Futility Theorem: PWM scanning in complex genomes yields approximately 1000 false predictions for every functional binding site [18] [2].

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies and Quantitative Data

Performance Benchmarks in Prokaryotic Promoter Prediction

In prokaryotic systems, PWM-based approaches have demonstrated more utility due to smaller genomes and better-defined promoter architectures. A study on σ70 promoters in E. coli K-12 developed a position-correlation scoring matrix (PCSM) algorithm that achieved 91% sensitivity and 81% specificity when tested on 683 experimentally verified promoters [23]. This performance substantially exceeds what is typically achievable in eukaryotic systems, though it still faces challenges with promoter variability and the presence of accessory elements such as UP sequences that modulate promoter strength [23].

Alternative approaches that incorporate DNA structural properties have shown particular promise in prokaryotic systems. Research demonstrates that promoter regions in bacteria exhibit characteristically lower DNA stability compared to flanking regions, with average free energy at the -20 position measured at -17.48 kcal/mol compared to -19.42 kcal/mol at -200 position and -20.19 kcal/mol at +200 position in E. coli [24]. This stability-based discrimination achieves sensitivity between 50-90% with precision rates of 1 false positive per 967-16214 nucleotides, depending on cutoff parameters [24].

Large-Scale Benchmarking of Motif Discovery Platforms

The Gene Regulation Consortium Benchmarking Initiative (GRECO-BIT) conducted a comprehensive analysis of 4,237 experiments for 394 human transcription factors across five experimental platforms [20]. This large-scale evaluation revealed that nucleotide composition and information content are not correlated with motif performance and do not help in detecting underperformers [20]. The study generated 219,939 PWMs, with 164,570 derived from approved experiments, providing an unprecedented resource for evaluating motif discovery tools [20].

Table 2: Cross-Platform Performance of Motif Discovery Tools

| Experimental Platform | Compatible Motif Discovery Tools | Key Technical Biases | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| HT-SELEX | DimontHTS, MEME, STREME | Saturates with strongest binding sequences | In vitro synthetic sequences |

| ChIP-Seq | HOMER, MEME, ChIPMunk | Cellular and genomic context influences | In vivo genomic context |

| Protein Binding Microarray (PBM) | Specialized adaptation from Weirauch et al. | Probe design constraints | In vitro defined sequences |

| GHT-SELEX | Autoseed, STREME, ExplaiNN | Genomic fragment representation | In vitro genomic fragments |

| SMiLE-Seq | RCade, MEME, HOMER | Microfluidics-specific artifacts | In vitro synthetic sequences |

Advanced Methodologies: Overcoming PWM Limitations

Integrated Workflow for Enhanced TFBS Prediction

The following workflow illustrates a modern approach that integrates multiple data types to overcome limitations of simple PWM scanning:

Integrated workflow combining positional priors, PWM scanning, and binding site clustering to improve prediction accuracy [18] [19].

Protocol: Enhanced Motif Discovery Using Positional Priors

Objective: Improve PWM-based TFBS prediction accuracy in complex genomes by incorporating positional prior information.

Materials and Reagents:

- PriorsEditor Software: Java-based application for constructing positional priors tracks [18]

- Genomic Coordinates of target regions (e.g., promoter sequences)

- Feature Data Tracks: Phylogenetic conservation scores, nucleosome occupancy, histone modifications, DNA physical properties

- Motif Discovery Tools: MEME version 4.2+ or PRIORITY that support positional priors [18]

- PWM Collections: JASPAR, TRANSFAC, or HOCOMOCO databases [18] [21]

Procedure:

Sequence Preparation

- Extract genomic sequences of interest (e.g., 1000-3000 bp upstream of transcription start sites)

- Annotate sequence boundaries relative to functional landmarks (TSS, etc.)

Positional Priors Construction Using PriorsEditor

- Import numeric data tracks (conservation scores, DNA stability profiles)

- Import region data tracks (known binding sites, chromatin accessibility regions)

- Combine multiple features using operations (extension, merging, normalization)

- Create a composite priors track weighted by feature importance

Motif Discovery with Integrated Priors

- Option A: Direct incorporation into compatible tools (MEME 4.2+)

- Option B: Sequence masking by replacing low-prior regions with Ns

- Execute motif discovery using appropriate algorithms

Result Validation and Filtering

- Filter predictions based on priors overlap

- Adjust prediction scores using priors values

- Validate with orthogonal data (comparative genomics, experimental evidence)

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For sparse data, use interpolation to create continuous priors tracks

- When using sequence masking, optimize the prior threshold to balance sensitivity and specificity

- For cross-species analysis, create species-specific background models [19]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PriorsEditor | Software Tool | Creates positional priors tracks from multiple genomic features | Focus motif discovery to functional regions [18] |

| HOCOMOCO Database | PWM Collection | Provides curated transcription factor binding models | Variant effect prediction, motif scanning [21] |

| JASPAR Database | PWM Collection | Open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles | De novo motif discovery, binding site prediction [2] [25] |

| motifDiff | Variant Effect Tool | Quantifies effects of sequence variants using PWM models | Interpretation of non-coding variants [21] |

| Codebook Motif Explorer | Motif Catalog | Catalogues motifs and benchmarking results | Exploration of verified binding specificities [20] |

| TFM-Explorer | Motif Discovery Tool | Identifies locally overrepresented TFBSs using comparative genomics | Finding regulatory motifs in co-regulated genes [19] |

Emerging Solutions and Alternative Approaches

Advanced Modeling Strategies

Recent approaches have moved beyond simple PWM models to address their fundamental limitations:

- Dinucleotide PWMs: motifDiff and similar tools incorporate dinucleotide parameters that capture dependencies between adjacent bases, providing more accurate binding affinity predictions [21].

- Machine Learning Integration: Random forest models combining multiple PWMs can account for multiple modes of TF binding, demonstrating the potential of ensemble approaches [20].

- Deep Learning Models: Interpretable deep learning frameworks can learn cell-type-specific sequence rules that govern TF binding, capturing complex interdependencies beyond PWM capabilities [22].

- Biophysical Models: Tools like motifDiff implement statistically rigorous normalization strategies that map motif scores to binding probabilities, enhancing variant effect prediction [21].

Experimental-Computational Integration

The most successful modern approaches tightly integrate computational prediction with experimental validation:

- Cross-Platform Validation: The GRECO-BIT initiative demonstrates the importance of approving experiments that yield consistent motifs across platforms and replicates [20].

- Allele-Specific Binding Analysis: Resources like ADASTRA and UDACHA provide large-scale in vivo validation datasets for benchmarking prediction tools [21].

- Multi-assay Framework: Combining in vitro (SELEX, PBM) and in vivo (ChIP-seq) approaches controls for technical biases while providing biological context [20].

While Position Weight Matrices remain valuable tools for initial characterization of transcription factor binding specificities, particularly in prokaryotic systems, their limitations in complex genomes are fundamental and well-documented. The "futility theorem" persists as a challenge because it reflects biological reality: functional transcription factor binding depends on contextual information beyond mere sequence compatibility. Successful modern approaches therefore integrate PWM scanning with additional genomic features, evolutionary conservation, chromatin accessibility data, and experimental validation to achieve biologically meaningful predictions. For prokaryotic promoter prediction, DNA stability-based methods and position-correlated scoring matrices offer promising alternatives that address specific limitations of traditional PWM approaches. The future of regulatory sequence analysis lies not in abandoning PWM models, but in strategically augmenting them with complementary data types and analysis techniques that capture the complexity of genomic regulation.

A Practical Workflow: How to Apply PWMs for Prokaryotic Promoter Identification

Within the broader context of developing accurate prokaryotic promoter prediction models, the Position Weight Matrix (PWM) stands as a fundamental and widely adopted method for representing the binding specificity of transcription factors (TFs) [2]. In prokaryotes, TFs bind to promoter regions to regulate transcription initiation, and characterizing these binding sites is crucial for understanding gene regulatory networks. A PWM provides a quantitative model that captures the nucleotide preferences at each position within a short DNA sequence motif, offering a significant advantage over simplistic consensus sequences by accounting for variability in TF binding [2]. This document provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for constructing a PWM from a set of experimentally validated binding sites, a critical skill for researchers and scientists engaged in the computational analysis of gene regulation.

Materials and Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials and Computational Tools

The following table lists key reagents, software, and data resources required for PWM construction and analysis.

| Item Name | Type/Category | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Experimentally Validated Binding Sites | Data | Core input data; typically derived from literature curation or high-throughput experiments like ChIP-seq, SELEX, or PBM [2] [26]. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tool | Software | To create a gapless multiple local alignment of confirmed binding site sequences (e.g., Clustal Omega, MUSCLE). |

| PWM Construction Script/Software | Software | To perform mathematical conversions from a Position Frequency Matrix (PFM) to a PWM (e.g., custom Python/R scripts, bioinformatics suites). |

| Genomic Sequence Data | Data | Provides the background nucleotide frequencies ((q_\alpha)) necessary for calculating log-odds scores [26]. |

| JASPAR/TRANSFAC Database | Data Repository | Source of curated, non-redundant PWMs for model validation and comparative studies [2] [26]. |

| Pseudo-count (μ) | Parameter | A small value (often 1) added to frequency counts to prevent undefined mathematical operations from zero values [26]. |

Experimental Protocol and Computational Methodology

Data Acquisition and Preparation

1. Gather Binding Site Sequences: Collect a set of DNA sequences confirmed to bind the transcription factor of interest. These can be obtained from:

- Literature Curation: Manually compiling sites from published studies [2].

- High-Throughput Experiments: Utilizing data from methods such as ChIP-seq (chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing), Protein Binding Microarrays (PBM), or SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment) [2] [26].

- Public Databases: Downloading pre-compiled sets from databases like JASPAR or TRANSFAC [26].

2. Perform Multiple Sequence Alignment: Create a gapless multiple local alignment (GMLA) of all collected sequences. The accuracy of the final PWM is highly dependent on this precise alignment, which ensures that corresponding nucleotide positions across all binding sites are correctly aligned [2]. The resulting alignment should have a consistent length, (L).

Constructing the Position Frequency Matrix (PFM)

From the GMLA, construct a Position Frequency Matrix (PFM). The PFM is a 4×(L) matrix (M), where each element (n_{\alpha, j}) contains the count of how many times nucleotide (\alpha) (where (\alpha \in {A, C, G, T})) appears at position (j) in the alignment [2].

Formula 1: PFM Representation [ M = \begin{bmatrix} n{A,1} & n{A,2} & \cdots & n{A,L} \ n{C,1} & n{C,2} & \cdots & n{C,L} \ n{G,1} & n{G,2} & \cdots & n{G,L} \ n{T,1} & n{T,2} & \cdots & n{T,L} \end{bmatrix} ]

Example PFM (L=5):

| Position (j) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| C | 5 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| G | 8 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 1 |

| T | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

Converting PFM to Position Probability Matrix (PPM)

Convert the PFM to a Position Probability Matrix (PPM), also known as a Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM). This step involves normalizing the frequency counts to probabilities and incorporating a pseudo-count to prevent issues with zero counts.

1. Apply Pseudo-count: Adjust counts using the formula below, where (f\alpha) is the background genomic frequency of nucleotide (\alpha), and (\mu) is the pseudo-count (typically (\mu=1)) [26]. [ v{\alpha,j} = \frac{n{\alpha,j} + f\alpha \cdot \mu}{\sum{x} n{x,j} + \mu} ]

2. Calculate Probabilities: Without a pseudo-count, the probability (p{\alpha,j}) of nucleotide (\alpha) at position (j) is simply (n{\alpha,j}/N), where (N) is the total number of sequences in the alignment [2].

Calculating the Position Weight Matrix (PWM)

The final step is to convert the PPM into a PWM by calculating the log-odds score for each nucleotide at each position. This score represents the log-likelihood ratio of the nucleotide appearing due to binding specificity versus random genomic background [2].

Formula 2: PWM Score Calculation [ S{\alpha,j} = \log2\left(\frac{v{\alpha,j}}{q\alpha}\right) = \log2\left(\frac{\frac{n{\alpha,j} + f\alpha \cdot \mu}{\sum{x} n{x,j} + \mu}}{q\alpha}\right) ] Here, (S{\alpha,j}) is the score in the PWM, and (q\alpha) is the background frequency of nucleotide (\alpha) in the target genome [2] [26].

Example PWM (log-odds, L=5):

| Position (j) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | -1.32 | 1.42 | -2.39 | -4.32 | 1.36 |

| C | -0.48 | -4.32 | 1.49 | -4.32 | -4.32 |

| G | 0.51 | -4.32 | -4.32 | 1.58 | -1.93 |

| T | -4.32 | 1.12 | -4.32 | -4.32 | 1.12 |

The relationship between the core matrices in PWM construction is visualized below.

Validation and Application in Prokaryotic Promoter Prediction

Scanning Genomic Sequences

To identify putative TF binding sites in a prokaryotic genome, slide the PWM along the DNA sequence. At each position (j), calculate a total score for the overlapping (L)-mer by summing the corresponding PWM values [2].

Formula 3: Sequence Score Calculation [ \text{score}(\text{word}) = \sum{j=1}^{L} S{\text{word}_j, j} ] A sequence word is considered a potential binding site if its score exceeds a predefined threshold. This threshold is often set as a percentage of the maximum possible score or based on statistical significance (p-value) [2].

Addressing Challenges and Limitations

- The Futility Theorem: In complex genomes, simple PWM scanning can yield excessive false positives because TF binding sites are short and variable [2]. Nearly every gene may have a match for every TF's PWM.

- Improving Specificity: To enhance prediction accuracy, combine PWM results with:

- Sequence conservation analyses across related species.

- Clustering of predicted sites (e.g., in prokaryotic enhancer-like regions).

- Overrepresentation of sites in promoters of co-regulated genes [2].

- Scaling and Energy Estimation: For quantitative studies, a scaling factor (λ) can be used to relate PWM scores to binding energy, allowing for comparison across different TFs [26]. The mismatch energy can be expressed as: [ E{\text{mismatch}, i, j} = (S{\text{max}, i} - S{i, j}) / \lambdai ] Where (S{\text{max}, i}) is the maximum possible score for TF (i), and (S{i, j}) is the observed score [26].

This protocol outlines the construction and application of a PWM, a cornerstone in the computational analysis of transcription factor binding sites. While powerful, it is crucial for researchers to be aware of its limitations, particularly the high rate of false positives when used in isolation. Integrating PWM-based predictions with evolutionary conservation data, binding site clustering, and other genomic information is essential for achieving reliable results in prokaryotic promoter prediction and gene regulatory network mapping. The continued development of advanced models, including those based on machine learning, builds upon this foundational PWM methodology to further increase predictive accuracy [2] [27].

Position-Specific Weight Matrices (PWMs) are a fundamental tool in computational genomics for identifying transcription factor binding sites and promoter elements in prokaryotes. This protocol details the practical application of PWMs for scanning DNA sequences to predict prokaryotic promoters, with a focused examination on establishing robust score thresholds and determining the statistical significance of predictions. The accurate mapping of promoter elements is a crucial step in microbial genomics and synthetic biology, where predicting the potential generation of new promoter sequences is critical when combining DNA elements into synthetic constructs [28]. Within the broader thesis on PWM-based prokaryotic promoter prediction, this document provides the essential methodological framework for transitioning from theoretical matrix construction to applied biological discovery.

Theoretical Background

Position-Specific Weight Matrices in Prokaryotic Promoter Prediction

A Position-Specific Weight Matrix quantitatively represents the nucleotide preferences at each position of a functional DNA element, such as a promoter's -10 and -35 boxes in E. coli [28]. PWMs evolved from simpler consensus sequences to provide a more nuanced model of binding affinity, capable of capturing subtle variations in transcription factor binding specificity. In prokaryotes, promoter prediction tools often utilize PWMs of the -10 (consensus TATAAT) and -35 (consensus TTGACA) boxes, considering their spacing and distance from the transcription start site (TSS) to identify putative promoters [28]. These matrices serve as the computational basis for scoring DNA sequences during scanning procedures.

The Scoring Framework

When scanning a DNA sequence, a sliding window approach is used to calculate a match score between a sequence segment and the PWM. This score, typically representing the log-likelihood ratio of the segment being a functional site versus random background, provides a quantitative measure of binding potential. The score calculation for a sequence S of length L against a PWM M is:

Score(S) = Σi=1L Mi(Si)

Where Mi(Si) is the matrix value for the nucleotide at position i in sequence S. Higher scores indicate a closer match to the consensus motif. The establishment of appropriate thresholds for these scores is critical for balancing prediction sensitivity and specificity, minimizing both false positives and false negatives [28].

Experimental Protocols

Workflow for Sequence Scanning and Threshold Optimization

Diagram 1: Sequence scanning and threshold optimization workflow.

Protocol 1: Data Set Preparation for PWM Training and Validation

Purpose: To curate high-quality sequence data for constructing reliable PWMs and establishing performance benchmarks.

Materials:

- Genomic sequences of target prokaryotic organisms

- Experimentally validated promoter sequences from databases (e.g., RegulonDB, DBTBS)

- Computing environment with bioinformatics tools (e.g., MEME, MOODS)

Procedure:

Positive Set Collection:

- Extract experimentally validated promoter sequences from curated databases such as RegulonDB for E. coli or DBTBS for B. subtilis [28] [29].

- For sigma-70 promoters in E. coli, include regions from -60 to +20 relative to the TSS to capture core promoter elements [28].

- Ensure sequence diversity by including promoters from various functional categories and genomic locations.

Negative Set Construction:

- Extract sequences from protein-coding regions (ORFs) to create a negative set with different nucleotide composition [28].

- Alternatively, generate random sequences with similar nucleotide distributions to the target genome [28].

- For rigorous validation, include intergenic regions lacking promoter activity.

Data Set Partitioning:

- Randomly divide sequences into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets while maintaining class balance.

- Ensure no significant sequence similarity between partitions using tools like CD-HIT.

Sequence Formatting:

- Convert all sequences to FASTA format with consistent identifiers.

- Maintain uniform sequence lengths through trimming or padding.

Troubleshooting:

- If performance is poor, check for sequence redundancy or biased nucleotide composition.

- For underrepresented promoter classes, consider data augmentation techniques.

Protocol 2: PWM Construction from Sequence Alignments

Purpose: To create a Position-Specific Weight Matrix from aligned promoter sequences.

Procedure:

Sequence Alignment:

- Perform multiple sequence alignment of known promoter sequences using tools like MUSCLE or MAFFT.

- For prokaryotic promoters, focus alignment on the -10 and -35 boxes with appropriate spacing consideration.

Frequency Calculation:

- Calculate position-specific nucleotide frequencies fi(b) for each position i and nucleotide b.

- Apply a small pseudocount (e.g., 0.5) to avoid zero frequencies: f'i(b) = [counti(b) + pseudocount] / [N + 4×pseudocount], where N is the number of sequences.

Background Model:

- Calculate genome-wide nucleotide frequencies p(b) for each nucleotide b.

- Alternatively, use sequence-specific background models when scanning genomic regions with varying composition.

Weight Matrix Calculation:

- Compute position-specific weights as log-likelihood ratios: Mi(b) = log2[f'i(b) / p(b)].

- Store the matrix in a standard format compatible with scanning tools (e.g., TRANSFAC, JASPAR).

Validation:

- Test the PWM's ability to recover training sequences.

- Compare with known consensus motifs for biological plausibility.

Protocol 3: Sequence Scanning and Threshold Optimization

Purpose: To identify putative promoters in genomic sequences and establish optimal score thresholds.

Procedure:

Sequence Scanning:

- Implement a sliding window approach across the target sequence(s) using the PWM dimensions.

- At each position, calculate the match score by summing the relevant position-specific weights.

- For prokaryotic promoters, consider scanning for -10 and -35 boxes with appropriate spacing constraints.

Initial Threshold Estimation:

- Calculate the score distribution for known positive and negative sequences.

- Set an initial threshold that captures a high percentage (e.g., 95%) of true positives.

- Alternatively, use percentiles of the background score distribution (e.g., 99th percentile).

Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Apply the current threshold to the validation set and calculate:

- Sensitivity (SN) = TP / (TP + FN)

- Specificity (SP) = TN / (TN + FP)

- Accuracy (ACC) = (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN)

- Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) = (TP×TN - FP×FN) / √[(TP+FP)(TP+FN)(TN+FP)(TN+FN)] [28]

- Apply the current threshold to the validation set and calculate:

ROC Analysis:

- Systematically vary the threshold across the range of observed scores.

- At each threshold, calculate the true positive rate (sensitivity) and false positive rate (1-specificity).

- Plot the ROC curve and calculate the area under the curve (AUC) as an overall performance measure.

Optimal Threshold Selection:

- Identify the threshold that maximizes the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) [28].

- Alternatively, use Youden's J statistic (J = sensitivity + specificity - 1).

- Consider application-specific requirements (e.g., high sensitivity for discovery, high specificity for validation).

Validation:

- Apply the optimized threshold to the independent test set.

- Compare performance with existing tools and benchmarks.

Protocol 4: Statistical Significance Assessment

Purpose: To calculate p-values for putative promoter predictions, estimating the probability of observing similar matches by chance.

Materials:

- Scoring matrix and optimized threshold

- Background sequence model (Markov chain of appropriate order)

- Computational resources for empirical null distribution generation

Procedure:

Theoretical p-value Calculation (if applicable):

- For certain score distributions, approximate p-values using extreme value distributions.

- Fit parameters to the background score distribution.

Empirical p-value Estimation:

- Generate a large number (e.g., 10,000) of random sequences with similar length and composition to the target genome.

- Scan these sequences with the PWM and record the maximum scores for each.

- Fit an empirical distribution to these maximum scores.

- For a candidate sequence with score S, calculate p-value as the proportion of random sequences with score ≥ S.

Multiple Testing Correction:

- Apply Bonferroni correction for genome-wide scans: padjusted = min(p × N, 1), where N is the number of positions scanned.

- Alternatively, use less conservative methods like Benjamini-Hochberg for false discovery rate control.

Confidence Assessment:

- Classify predictions based on significance levels: e.g., significant (padjusted < 0.05), highly significant (padjusted < 0.01).

- Report both raw scores and significance values in final predictions.

Performance Benchmarking of Prediction Tools

Systematic comparison of promoter prediction tools using standardized metrics and data sets provides essential guidance for threshold selection and performance expectations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Bacterial Promoter Prediction Tools on E. coli Data Sets [28]

| Tool | Method | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPROM | Weight matrices + linear discriminant analysis | Lower performance | Lower performance | Lower performance | Lower performance |

| bTSSfinder | PWMs, oligomer frequencies, physicochemical properties + neural network | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| BacPP | Weighted rules from neural network | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| CNNProm | Convolutional neural networks | High | High | High | High |

| iPro70-FMWin | 22,595 features + logistic regression | Highest | Highest | Highest | Highest |

| 70ProPred | SVM with trinucleotide tendencies | High | High | High | High |

| iPromoter-2L | Not specified | High | High | High | High |

Table 2: Tool Availability and Key Features [28]

| Tool | Availability | Sigma Factors | Input Sequence | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPROM | Web server | sigma70 | Genomic sequence | Basic scanning with known limitations |

| bTSSfinder | Stand-alone and Web server | 24, 28, 32, 38, 70 | [-200, +51] relative to TSS | Multiple sigma factors |

| BacPP | Web server | 24, 28, 32, 38, 54, 70 | [-60, +20] relative to TSS | Multiple sigma factors |

| Virtual Footprint | Web server | Various from databases | User-defined | Database-supported scanning |

| IBBP | Source code | sigma70 (expandable) | [-60, +20] relative to TSS | Image-based approach |

| iPro70-FMWin | Web server | sigma70 | [-60, +20] relative to TSS | Highest accuracy for sigma70 |

| 70ProPred | Web server | sigma70 | [-60, +20] relative to TSS | High predictive power |

| CNNProm | Web server | sigma70 | [-60, +20] relative to TSS | Deep learning approach |

| PePPER | Web server | Various | Genomic sequence | Prokaryote promoter elements |

Advanced Threshold Optimization Techniques

Diagram 2: Threshold optimization and significance assessment process.

Machine Learning-Enhanced Thresholding

Modern promoter prediction increasingly employs sophisticated machine learning approaches that integrate multiple sequence features beyond simple PWM scores:

Integrated Feature Analysis:

- Tools like iPro70-FMWin extract up to 22,595 features from sequence data, using AdaBoost to select the most representative features for logistic regression classification [28].

- These features may include k-mer frequencies, physicochemical properties, and structural descriptors that capture subtleties beyond position-specific nucleotide preferences.

Neural Network Approaches:

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), as implemented in CNNProm, automatically learn relevant features from sequence data, potentially discovering patterns missed by traditional PWMs [28].

- These methods generate classification probabilities that can be directly used as confidence scores, with thresholds typically set at 0.5 or optimized for specific performance metrics.

Ensemble Methods:

- Combining predictions from multiple tools or algorithms can improve overall performance and provide more robust significance estimates.

- Agreement between independent methods often indicates higher confidence predictions.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PWM-Based Promoter Prediction

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validated Promoter Sequences | Biological Data | Gold-standard positive set for training and validation | RegulonDB, DBTBS [29] |

| Background Genomic Sequences | Biological Data | Negative set and null model for statistical testing | NCBI GenBank, RefSeq |

| PWM Construction Tools | Software | Build position-specific weight matrices from aligned sequences | MEME Suite, MOODS [29] |