Optimizing DNA Extraction from Soil Samples: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize DNA extraction from complex soil matrices.

Optimizing DNA Extraction from Soil Samples: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize DNA extraction from complex soil matrices. It covers foundational principles, evaluates current methodological approaches, and offers advanced troubleshooting strategies. A strong emphasis is placed on validation and comparative analysis to ensure reliable, reproducible results for downstream applications like metagenomics and pathogen surveillance, which are critical for drug discovery and clinical research.

The Critical Foundation: Why Soil DNA Extraction Demands Specialized Strategies

Troubleshooting Guides

Humic Acid Interference and Inhibition of Molecular Procedures

Problem: Humic substances (HS) are complex organic polymers in soil with physicochemical properties similar to nucleic acids, leading to their co-extraction with DNA. This results in brown-colored DNA extracts and inhibition of downstream enzymatic reactions like PCR [1] [2]. Humic acids can inhibit PCR even at very low concentrations (e.g., as little as 10 ng) [3].

Solutions:

- During Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Commercial Kits with Inhibitor Removal: Use kits specifically designed for soil, such as those from Qiagen, which incorporate Inhibitor Removal Technology (IRT) to eliminate humic acids [4].

- Chemical Additives: Incorporate additives into the lysis buffer:

- Cetyl Trimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB): Helps to separate DNA from polysaccharides and humic acids [1] [5] [3].

- Polyvinyl Polypyrrolidone (PVPP): Binds to and precipitates phenolic compounds like humic acids [5].

- Vitamins: Innovative use of pyridoxal hydrochloride and thiamine hydrochloride (Vitamin B6 and B1) has been shown to selectively precipitate humic acids, yielding PCR-ready DNA [3].

- Skim Milk: Added during extraction to prevent DNA adsorption and degradation by humic substances [6].

- Post-Extraction Cleanup:

- Dilution: A simple tenfold dilution of the DNA extract can reduce inhibitor concentration below the inhibition threshold, though it may reduce sensitivity [4].

- DNA Cleanup Kits: Use standard silica-column or magnetic bead-based cleanup kits (e.g., AMPure XP beads) [4].

- Two-Stage Purification: A protocol using a silicon dioxide suspension (glass milk) followed by paramagnetic particles has been successful in concentrating DNA and removing inhibitors [4].

- During PCR Setup:

- Robust Master Mixes: Use specialized master mixes like Environmental Master Mix 2.0 (ThermoFisher) or Perfecta qPCR ToughMix, which are formulated to be tolerant of common inhibitors [4].

- PCR Enhancers: Add Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or skim milk powder to the PCR reaction to bind to and neutralize residual inhibitors [4].

Suboptimal DNA Yield and Quality Due to Sample Size

Problem: The amount of soil used for DNA extraction significantly impacts the assessment of microbial diversity and community structure, but not necessarily the determination of microbial abundance [7]. Inadequate soil sample sizes can lead to an underestimation of microbial richness and alter the observed co-occurrence patterns.

Solutions:

- Follow Recommended Sample Sizes: For most ecosystems, using at least 0.25 grams of soil is recommended to reflect the overall microbial diversity accurately [7] [8]. For soils with low microbial density, such as deserts, use 0.50 grams or more [7].

- Maintain Proper Soil-to-Container Volume Ratio: Ensure the sample size is appropriate for the extraction tube volume. For instance, using 0.2 g or 1 g of soil in a standard 2 mL tube for horizontal shaking is more effective and consistent than using 5 g in a larger tube with vertical shaking, which can lead to fluctuating DNA extraction efficiency and diversity metrics [6].

- Use Composite Sampling: For a representative profile of a larger area, collect and homogenize soil from multiple spots before subsampling for DNA extraction [9] [10].

Inconsistent Microbial Community Profiles from Different Sequencing Methods

Problem: The choice between amplicon sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA gene) and shotgun metagenomics can lead to variations in the observed microbial community structure due to technical biases like primer specificity, gene copy number variation, and differences in reference databases [8].

Solutions:

- Select the Appropriate Method for Your Goal:

- Use Optimized Bioinformatics: For shotgun data from complex soils, use classifiers like Kraken2 with curated databases (e.g., GTDB) and apply abundance thresholds to minimize false positives [8].

- Maintain Consistency: Use the same DNA extraction method, sequencing platform, and bioinformatic pipeline for all samples within a study to ensure comparability [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My soil DNA extract is brown and my PCR fails. What is the fastest solution? The quickest fix is to perform a tenfold dilution of your DNA template in the PCR reaction. This dilutes the humic acid inhibitors below their effective concentration. If sensitivity is critical, use a DNA cleanup kit or add BSA (0.1-0.5 μg/μL) to your PCR master mix [4].

Q2: How can I confirm that my PCR failure is due to inhibitors? Perform a PCR inhibition test. Spike a known amount of a control DNA (exogenous to your sample) into your reaction with and without your soil DNA extract. An increase in the Ct value for the control in the presence of your sample DNA indicates the presence of inhibitors [4].

Q3: What is the single most important factor in obtaining high-quality DNA from humus-rich soil? Using a robust, inhibitor-focused extraction method. While yield is important, purity is paramount for downstream applications. A method combining CTAB-based extraction with an additional purification step, such as a vitamin-based precipitation or a commercial inhibitor removal column, is most effective for humus-rich soils [1] [3].

Q4: My microbial diversity seems low compared to other studies. Could my soil sample size be too small? Yes. Studies show that DNA extraction from very small soil samples (e.g., 0.01 g or 0.025 g) can result in lower observed microbial richness and co-occurrence frequency compared to using 0.25 g or more. Ensure you are using a sufficient amount of soil, especially from low-biomass environments [7].

Q5: Should I use amplicon sequencing or shotgun metagenomics for my soil microbiome study? Your choice depends on your research question and resources. Amplicon sequencing is a cost-effective choice for comparing microbial community structure across many samples. Shotgun metagenomics is more expensive but provides deeper taxonomic resolution and direct access to functional genetic potential. Both methods can produce consistent patterns for major microbial phyla when analyzed with appropriate tools [8].

Table 1: Impact of Soil Sample Size on Microbial Diversity Analysis

This table summarizes findings on how the amount of soil used for DNA extraction influences the analysis of microbial communities [7].

| Soil Sample Size (g) | Microbial Abundance Determination | Microbial Richness | Microbial Community Composition | Co-occurrence Patterns | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 - 0.025 | Little to no effect | Lower than 0.25-1.00 g | Dramatic variations; not representative | Lower frequency; less robust | Study of microbial heterogeneity among microhabitats |

| 0.25 | Little to no effect | Representative and stable | Stable and representative | Robust patterns | Recommended minimum for overall diversity in most ecosystems |

| 0.50 - 1.00 | Little to no effect | Representative and stable | Stable and representative | Robust patterns | Soils with low microbial density; standard for some kits |

Table 2: Soil Properties and DNA Yield/Purity from Different Soil Types

This table illustrates how soil type and humic substance content affect DNA isolation success, based on a study of various Soil Reference Groups [1].

| Soil Reference Group | Land Use | Total Organic Carbon (g/kg) | Humic Substances Carbon (g/kg) | DNA Concentration (ng/μL) | A260/A280 (Purity) | A260/A230 (Purity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regosol | Plough field | 11.2 | 3.71 | 61.3 | 1.92 | 1.20 |

| Cambisol | Forest | 20.1 | 16.89 | 46.8 | 1.91 (2.07*) | 1.13 (1.40*) |

| Arenosol | Forest | 29.2 | 29.81 | 32.5 | 1.89 (1.95*) | 1.31 (1.90*) |

| Histosol | Meadow | 40.3 | 37.36 | 200.8 | 1.92 (1.95*) | 1.49 (1.53*) |

| Values in parentheses indicate purity ratios after an additional purification step, highlighting the need for extra cleaning in organic-rich soils. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Optimized High-Yield DNA Extraction from Soil

This is a modified CTAB-based protocol for manual DNA extraction from soil, incorporating steps to mitigate humic acid interference [5].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- CTAB Buffer: Cetyl Trimethylammonium Bromide; complexes with polysaccharides and humic acids, allowing their separation from nucleic acids.

- Proteinase K: A broad-spectrum serine protease; degrades proteins and helps in cell lysis.

- SDS: Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate; an ionic detergent that disrupts cell membranes and lyses cells.

- PEG: Polyethylene Glycol; promotes the precipitation of large DNA molecules.

- PCI: Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1); denatures and removes proteins from the lysate.

- Skim Milk: Binds to and neutralizes humic acids, preventing their co-purification with DNA.

Methodology:

- Lysis: Add 3 g of finely sieved soil to a tube containing 6 mL of extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 100 mM sodium, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1.5 M NaCl). Mix thoroughly.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Add 13 μL of proteinase K (10 mg/mL) and incubate horizontally at 37°C for 30 min on a platform shaker.

- Detergent Lysis: Add 750 μL of 20% SDS and incubate at 65°C for 90 min.

- Physical Lysis (Freeze-Thaw): To enhance lysis efficiency, freeze the tube in liquid nitrogen for 1 minute and immediately thaw it at 65°C for 90 minutes. Repeat this freeze-thaw cycle three times.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 10 min. Transfer the supernatant to a fresh tube. (Optional: Repeat lysis on the pellet to maximize yield).

- Precipitation: To the supernatant, add an equal volume of 30% PEG with 1.6 M NaCl. Incubate for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 20 min. Collect the aqueous layer.

- Organic Purification:

- Add an equal volume of PCI. Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. Transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube.

- Add an equal volume of Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (24:1). Mix by gentle inversion and centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 5 min.

- DNA Recovery: Carefully collect the aqueous layer (using a pipette tip with a cut end to avoid shearing). Add 0.6 volumes of chilled isopropanol, mix, and incubate at room temperature for 2 hours.

- Pellet Washing: Centrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 15 min. Discard the supernatant. Wash the pellet with 70% ethanol, air-dry, and resuspend in 50 μL of TE buffer.

- RNAse Treatment: Add heat-treated RNase A (0.2 μg/μL) and incubate at 37°C for 2 hours to remove RNA contamination.

Detailed Protocol: Rapid Vitamin-Based Purification for Inhibitor-Rich Soils

This protocol uses vitamins to precipitate humic acids, yielding high-purity DNA suitable for PCR without additional steps [3].

Methodology:

- Soil Lysis: Perform initial cell lysis on your soil sample using a bead-beating method with a suitable lysis buffer (e.g., TENNS buffer pH 9.5).

- Vitamin Purification: After lysis and initial centrifugation, add a mixture of pyridoxal hydrochloride and thiamine hydrochloride directly to the crude DNA extract.

- Precipitation of Humics: The vitamins will selectively interact with and precipitate humic acids.

- Separation: Centrifuge the sample to pellet the humic acid-vitamin complexes.

- Recovery: The supernatant now contains purified, PCR-ready genomic DNA and can be used directly or after standard ethanol precipitation.

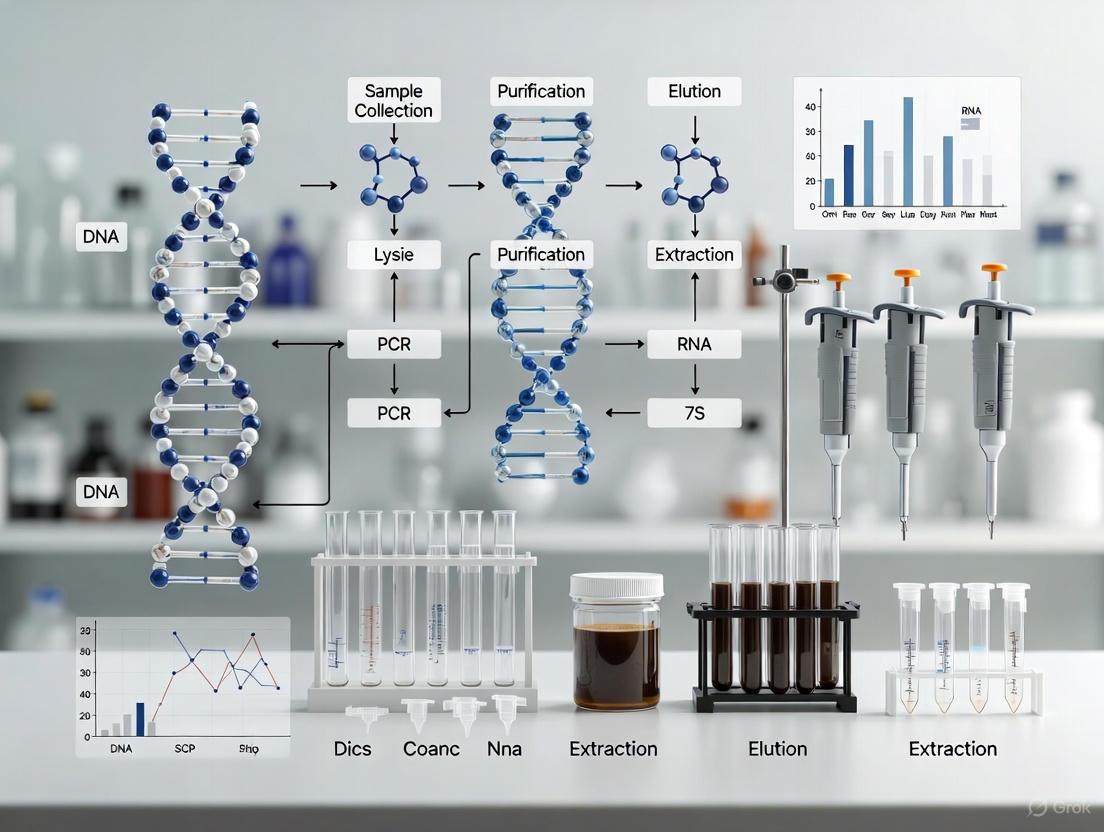

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Soil DNA Extraction Challenges and Solution Pathways. This workflow maps the primary challenges (red) encountered during DNA extraction from soil to their corresponding solutions (green), leading to successful outcomes for research.

Diagram 2: Selecting a Sequencing Method for Soil Microbiome Analysis. This decision guide compares the two primary sequencing approaches, highlighting their targets, advantages, and disadvantages to inform experimental design.

For researchers working with complex environmental samples like soil, the cell lysis step presents a significant challenge: how to break open robust cell walls efficiently without shearing the precious genetic material within. This guide addresses the core principles of cell lysis, framed within the context of optimizing DNA extraction from soil samples for downstream applications such as metagenomics and pathogen detection.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental trade-off in cell lysis for DNA extraction? The primary trade-off lies between DNA yield and DNA integrity. More intensive lysis methods (e.g., higher speed or longer duration of bead-beating) typically release more DNA from a higher proportion of cells, including those with tough walls. However, this increased physical force also shears the DNA into smaller fragments. Conversely, gentler lysis may preserve long, intact DNA strands but result in lower overall yield by failing to lyse more resistant cells [11] [12].

2. For soil samples, should I use mechanical or enzymatic lysis? Mechanical lysis (e.g., bead-beating) is generally more effective and reproducible for soil and environmental samples. While enzymatic lysis can yield higher quantities of DNA, the quality is often suboptimal and can lead to inconsistent microbial community profiles due to varying susceptibility of cell types. Mechanical lysis provides a more uniform and reliable disruption, which is crucial for representative community analysis [12].

3. My extracted DNA is fragmented. How can I get longer fragments for long-read sequencing? To obtain longer DNA fragments, you should optimize your mechanical lysis parameters by reducing the homogenization intensity. A study optimizing lysis for soil metagenomics found that using lower homogenization speed and shorter duration significantly increased DNA fragment length. For instance, a setting of 4 m sâ»Â¹ for 10 s produced fragments over 70% longer than more intensive protocols. Ensure your DNA purification steps afterward are gentle to avoid further shearing [11].

4. My downstream PCR is inhibited. How can I reduce carryover of contaminants? Soil contains substances like humic acids that can co-purify with DNA and inhibit enzymes. To mitigate this:

- Employ thorough washing steps with appropriate buffers during purification.

- Consider chemical treatments. For example, adding polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) can help adsorb phenolic compounds, and aluminum sulfate has been shown to be effective in removing persistent PCR inhibitors from clayed and sandy soils [13].

- Using phase-lock gel tubes during phenol-chloroform extraction can provide a cleaner separation of the aqueous DNA layer from organic solvents and contaminants [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low DNA Yield

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Inadequate Lysis: The lysis conditions may not be sufficient to break open all cells, particularly hardy microorganisms like Gram-positive bacteria or spores.

- Solution: Optimize your mechanical lysis protocol. Increase bead-beating intensity or duration systematically, but be aware of the trade-off with DNA integrity [15] [11].

- Solution: For highly resistant organisms, a combination of chemical (e.g., detergents) and mechanical lysis may be necessary. A universal protocol for mycobacteria, for example, combines chloroform treatment with bead-beating to overcome a tough, mycolic acid-rich cell wall [14].

Inefficient DNA Binding: The released DNA is not effectively binding to the purification column or magnetic beads.

- Solution: Ensure the binding buffer has the correct composition and pH. Optimize the incubation time and mixing steps to maximize contact between the DNA and the solid phase [15].

Problem: Degraded or Sheared DNA

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Overly Intensive Mechanical Lysis: Excessive mechanical force is physically breaking the DNA strands.

- Solution: Reduce the homogenization speed and time. Refer to the table below for data-driven optimization. Using a lower homogenization intensity has been proven to dramatically improve DNA integrity for long-read sequencing [11].

Nuclease Activity: Nucleases present in the sample are degrading the DNA after lysis.

Problem: Carryover of PCR Inhibitors

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Incomplete Removal of Contaminants: Washing steps were insufficient to remove humic substances, pigments, or other inhibitors common in soil.

- Solution: Incorporate additional wash steps with optimized buffers. For pigmented paddy soils, adding a Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) precipitation step (e.g., 20% PEG) was highly effective in removing carry-over pigments and yielding pure RNA/DNA [16] [13].

- Solution: Reduce the initial soil input mass, as overloading the purification system can saturate its capacity to remove inhibitors [13].

Experimental Data and Protocols

Quantitative Impact of Lysis Parameters on DNA

The following table summarizes key findings from a statistical design of experiments approach to optimize mechanical lysis for soil DNA, showing the clear trade-off between yield and integrity [11].

Table 1: Effect of Homogenization Parameters on DNA Yield and Fragment Length from Soil

| Homogenization Speed | Total Homogenization Time | Approx. Distance Travelled | DNA Yield (Total µg) | Mean DNA Fragment Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 m sâ»Â¹ | 5 s | 20 m | ~2.5 µg | 9,324 bp |

| 4 m sâ»Â¹ | 10 s | 40 m | Data not specified | 7,487 bp |

| 4 m sâ»Â¹ | 15 s | 80 m | Data not specified | 6,375 bp |

| 6 m sâ»Â¹ | 30 s | 180 m | Data not specified | 4,406 bp |

| 8 m sâ»Â¹ | 40 s | 960 m | ~15 µg | 3,418 bp |

Optimized Mechanical Lysis Protocol for Soil DNA

This protocol is adapted from research aimed at maximizing DNA length for long-read sequencing from diverse soil types [11].

- Sample Preparation: Weigh 0.3 - 0.5 g of soil.

- Initial Lysis: Add the soil to a tube containing lysis buffer and garnet beads (0.2 mm diameter).

- Mechanical Homogenization: Process the sample using a benchtop homogenizer (e.g., FastPrep-24) at 4 m sâ»Â¹ for 10 seconds.

- Incubation: Incubate the lysate on ice for 5 minutes to allow heat dissipation.

- Purification: Proceed with standard phenol-chloroform extraction or a commercial soil DNA kit purification, ensuring gentle pipetting to avoid shearing.

- Precipitation: Precipitate DNA with isopropanol and resuspend in elution buffer or nuclease-free water.

Workflow and Decision Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Cell Lysis and Inhibitor Removal in Soil DNA Extraction

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Lysis and Purification |

|---|---|

| Glass Beads (0.1-0.2 mm) | Provides mechanical disruption of cell walls through bead-beating. Critical for breaking open hardy microbial cells in soil [14] [11]. |

| Chloroform | A chemical lysis agent that disrupts lipid membranes. In a universal mycobacterial protocol, it sterilizes samples and efficiently removes cell wall lipids [14]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Adsorbs phenolic compounds and humic acids, which are common PCR inhibitors in plant and soil samples [13]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Used in precipitation steps to help remove pigments and other contaminants, thereby improving nucleic acid purity from complex samples like paddy soil [16]. |

| Aluminum Sulfate | Effectively flocculates and removes persistent PCR inhibitors from challenging, clay-rich soil matrices [13]. |

| Phase-Lock Gel Tubes | Facilitates easy and clean separation of the aqueous phase (containing DNA) from the organic phase (phenol-chloroform) during purification, minimizing carryover of inhibitors [14]. |

| β-Mercaptoethanol (β-ME) | A reducing agent that inhibits nucleases, helping to prevent the degradation of DNA and RNA during the extraction process [13]. |

| Ald-CH2-PEG5-Azide | Ald-CH2-PEG5-Azide, CAS:1446282-38-7, MF:C12H23N3O6, MW:305.33 g/mol |

| Ald-Ph-PEG6-acid | Ald-Ph-PEG6-acid, MF:C23H35NO10, MW:485.5 g/mol |

Impact of Soil Physicochemical Properties on Extraction Efficiency

The efficiency of DNA extraction from soil is a critical first step in molecular analysis, influencing all downstream results in microbial ecology, forensic science, and environmental monitoring. Soil is a complex and heterogeneous matrix where DNA molecules interact with various soil components, leading to significant challenges in obtaining high-quality, representative genetic material. The physicochemical properties of soil—including its texture, organic matter content, pH, and mineral composition—directly impact the yield, purity, and overall quality of extracted DNA. Understanding these interactions is essential for optimizing extraction protocols, ensuring reproducible results, and accurately interpreting molecular data. This technical support guide addresses the most common challenges researchers face when extracting DNA from diverse soil types, providing evidence-based troubleshooting strategies to enhance experimental outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How do soil texture and composition affect DNA extraction efficiency, and how can I adapt my protocol accordingly?

Soil texture, particularly clay and organic matter content, significantly impacts DNA extraction efficiency through multiple mechanisms that can inhibit downstream applications.

Clay Interactions: Clay minerals (e.g., montmorillonite, kaolinite) possess charged surfaces that strongly adsorb DNA molecules through cation bridging and hydrogen bonding, effectively sequestering them and reducing available yield [17]. Soils with high clay content (≥30%) present particular challenges for DNA recovery due to this binding capacity and increased soil particle surface area [18].

Organic Matter Interference: Soil organic matter (SOM), especially humic and fulvic acids, co-extracts with DNA and functions as a potent inhibitor in downstream molecular applications like PCR and quantitative PCR (qPCR) [17] [19]. These substances inhibit enzymatic reactions by interacting with DNA templates and polymerase enzymes [19]. Soils with high organic content (≥3%) typically require enhanced purification steps to remove these contaminants effectively [18].

Mitigation Strategies:

- Increased Washing: Implement additional wash steps during extraction to dissociate DNA from soil particles. The use of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) as a preliminary wash can help remove contaminants before cell lysis [20].

- Chemical Additives: Incorporate additives that compete for binding sites. Mannitol in the lysis buffer can help protect DNA integrity and improve yield [20]. The chemical reagents in commercial kits are specifically designed to disrupt DNA-soil particle interactions [17].

- Sample Mass Adjustment: For kits designed for small soil masses (e.g., 0.25 g), consider that this may not be representative of heterogeneous soil communities. For high-clay soils, using a kit designed for larger sample masses (e.g., 10 g) can improve representativity and capture higher species richness, though it may require additional purification [21].

FAQ 2: Which commercial DNA extraction kit should I choose for my specific soil type?

No single extraction kit performs optimally across all soil types. Kit selection should be based on your specific soil properties and research objectives, as different kits employ varied mechanisms for cell lysis and inhibitor removal.

Table: Comparison of Commercial DNA Extraction Kits for Different Soil Types

| Kit Name | Key Features | Optimal Soil Types | Inhibitor Removal | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIAGEN DNeasy PowerLyzer (PowerSoil) [21] [19] | - Based on 0.25 g soil mass- Two washing steps- Bead beating for lysis | - Low to moderate clay and OM- Standard microbial diversity | Chemical precipitation | Captures diversity comparable to indirect extraction methods; may be less representative for heterogeneous soils [21]. |

| QIAGEN DNeasy PowerMax [21] | - Based on 10 g soil mass- Designed for larger, more representative samples | - High clay or OM content- High microbial diversity studies | Chemical precipitation | Captures higher taxonomic richness from complex soils; may require additional purification due to higher inhibitor load [21]. |

| MP Biomedicals FastDNA SPIN [19] | - Fast protocol- Single washing step- High-temperature elution (55°C) | - Routine soils with low inhibitor content- Rapid processing needs | No dedicated column | Faster but may be less effective for soils with high inhibitor content [19]. |

| MACHEREY-NAGEL Nusoil Kit [19] | - Dedicated inhibitor removal column- Four washing steps | - Soils with very high humics/contaminants- Forensic or demanding applications | Silica column filtration | Most extensive purification; effective for recalcitrant soils but more time-consuming [19]. |

The performance of these kits varies significantly. A recent study found that despite extensive purification, kit selection introduced quantifiable discrepancies in qPCR-based gene quantification, especially in soils with high organic content or clay, underscoring that DNA template quality is kit-dependent [19]. For comprehensive biodiversity assessments, a combined approach using both direct DNA extraction from soil and DNA from previously extracted invertebrates (comDNA) has shown complementarity, capturing overlapping but distinct taxonomic profiles [21].

FAQ 3: What are the most effective methods to remove PCR inhibitors from soil DNA extracts?

PCR inhibitors commonly found in soil extracts include humic substances, polysaccharides, phenolic compounds, and metal ions, which can lead to false negatives or quantification errors in molecular assays [19].

Multiple Purification Strategies:

- Silica-Based Columns: Most commercial kits use selective DNA binding to silica membranes in the presence of chaotropic salts, followed by ethanol-based washes to remove contaminants. Kits with multiple wash steps (e.g., Nusoil with four washes) generally provide purer DNA than those with fewer washes [19].

- Chemical Precipitation: Some kits employ chemical reagents that precipitate inhibitors, leaving DNA in solution for further purification [17].

- Additive-Based Inhibition Management: Adding compounds like bovine serum albumin (BSA) to PCR reactions can bind to and neutralize residual inhibitors, improving amplification success [17].

- Dilution of DNA Extract: Simple dilution of the DNA template can reduce inhibitor concentration to sub-critical levels, though this also dilutes the target DNA and may not be suitable for low-abundance targets [17].

Addressing Specific Inhibitors:

- Cations (e.g., Mg²âº): While Mg²⺠is a necessary cofactor for PCR, excess concentrations can inhibit the reaction. Spiking experiments show that residual Mg²⺠ions in soil extracts, even after purification, can significantly interfere with qPCR accuracy [19].

- Humic Acids: These are particularly challenging due to structural similarity to DNA. The use of dedicated inhibitor removal columns (as in the Nusoil kit) or the inclusion of mannitol and PVPP in extraction buffers has been shown to improve humic acid removal [20].

FAQ 4: How should I handle and store soil samples before DNA extraction to preserve integrity?

Pre-extraction handling significantly impacts DNA recovery and the representativeness of the microbial community.

Best Practices for Sample Storage:

- Immediate Freezing: Store samples at -20°C or -80°C as soon as possible after collection to halt microbial activity and preserve the in situ microbial community structure [17] [22].

- Avoid Repeated Freeze-Thaw: Process samples into aliquots to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles, which can degrade DNA and lyse cells [17].

- Field Preservation: If immediate freezing is not possible, consider using commercial preservation solutions that stabilize DNA at room temperature.

Pre-processing Steps:

- Homogenization: Gently homogenize the soil sample (after removing stones and large debris) to create a representative subsample. Sieving through a 2 mm mesh is a common practice [22] [23].

- Contamination Control: Use sterile equipment during sampling and processing to prevent cross-contamination between samples, which is especially critical in forensic applications [17].

Diagram: Logical workflow for addressing common soil-related DNA extraction challenges. The diagram outlines the primary soil properties that create analytical problems and directs users toward appropriate solutions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Optimizing Soil DNA Extraction

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) [20] | Initial wash to remove soluble contaminants and loosely bound ions. | A 120 mM PBS wash prior to lysis effectively removes soil contaminants like polysaccharides and urea without lysing cells [20]. |

| Mannitol [20] | Osmotic stabilizer and inhibitor mitigant. | Inclusion in the lysis buffer helps protect DNA integrity and reduces co-extraction of humic substances. |

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) [20] | Detergent for cell lysis and precipitation of humic acids. | Effective in removing polysaccharides and humic contaminants, especially when combined with chloroform extraction. |

| Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) [20] | Binds and removes phenolic compounds. | Added to the extraction buffer to specifically target phenolic inhibitors, which are common in soils with high organic matter. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) [20] | Neutralizes negative charges on DNA backbone and soil particles. | Reduces DNA adsorption to soil particles (e.g., clay); used in precipitation steps. |

| Ethanol / Isopropanol | DNA precipitation and washing. | Standard for precipitating nucleic acids from aqueous solution and removing salts in wash steps. |

| Silica Membranes / Beads [19] | Selective DNA binding in the presence of chaotropic salts. | Foundation of most commercial kits; allows for separation of DNA from other contaminants through binding and washing. |

| Allantoin Ascorbate | Allantoin Ascorbate, CAS:57448-83-6, MF:C6H8O6.C4H6N4O3, MW:334.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Alprostadil sodium | Alprostadil sodium, CAS:27930-45-6, MF:C20H33NaO5, MW:376.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Optimization & Method Validation

Experimental Protocol: Comparative Evaluation of DNA Extraction Kits

To validate the optimal DNA extraction method for a specific soil type, a comparative evaluation is recommended.

- Soil Characterization: Analyze key physicochemical parameters of the soil, including pH, texture (sand, silt, clay %), total organic carbon (TOC), and moisture content [17] [22].

- Kit Selection: Select 2-3 commercial kits with different purification mechanisms (e.g., PowerSoil vs. Nusoil) [19].

- Spike-In Control: For quantitative studies, seed the soil with a known quantity of a model bacterium (e.g., Pseudomonas putida) prior to extraction. This allows for calculation of extraction efficiency and identification of inhibition [19].

- Extraction: Perform extractions in triplicate for each kit, strictly following manufacturer protocols.

- DNA Quality & Quantity Assessment:

- Spectrophotometry: Measure A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios. Ideal values are ~1.8 and >2.0, respectively. Low A260/A230 indicates residual humics or salts [20].

- Gel Electrophoresis: Check for high molecular weight DNA and RNA contamination.

- qPCR Analysis: Amplify a target gene (e.g., 16S rRNA) to assess inhibition. Compare cycle threshold (Ct) values between soil DNA extracts and a pure standard. A higher Ct indicates the presence of inhibitors [19].

Workflow Diagram: Soil DNA Extraction and Quality Control

Diagram: A comprehensive experimental workflow for soil DNA extraction, highlighting the critical steps from sample collection to quality control, with feedback loops for troubleshooting.

In conclusion, successful DNA extraction from soil requires a tailored approach that accounts for specific physicochemical properties. By understanding the interactions between soil components and DNA, selecting appropriate extraction methodologies, and implementing rigorous quality control, researchers can significantly improve the reliability and interpretability of their molecular data.

In the context of optimizing DNA extraction from soil samples, defining and measuring success is paramount. For downstream applications like metabarcoding, qPCR, or next-generation sequencing, the quality of the initial DNA extract is a critical determinant. Success is multi-faceted, hinging on four interdependent metrics: DNA Yield (quantity), Purity (freedom from contaminants), Fragment Size (molecular integrity), and Representativity (accurate reflection of the original community). This guide provides troubleshooting support to help you diagnose and resolve issues related to these key metrics in your soil DNA research.

FAQ: Understanding the Core Metrics

Q1: What are the target values for DNA purity, and how are they measured?

DNA purity is commonly assessed using spectrophotometric absorbance ratios [24] [25]. The table below outlines the ideal values and the implications of deviations.

| Purity Ratio | Ideal Value | Indication of Value Below Ideal | Indication of Value Above Ideal |

|---|---|---|---|

| A260/A280 | 1.7 - 2.0 [24] | Protein contamination (e.g., phenol) [24] | Not typically a concern for soil DNA. |

| A260/A230 | >1.5 [24] | Contamination with chaotropic salts, EDTA, or carbohydrates [24] [26] | Not typically a concern for soil DNA. |

Q2: How can I accurately determine the concentration of low-yield soil DNA extracts?

For low-yield samples, fluorescence methods are superior to spectrophotometry [25]. Fluorescence assays use dyes that selectively bind to double-stranded DNA, making them less susceptible to interference from common contaminants like salts, proteins, or free nucleotides [24] [27]. This results in a more accurate concentration measurement, which is crucial for normalizing downstream PCR reactions.

Q3: My downstream PCR is inhibited. What is the likely cause and how can I fix it?

Inhibition is a common challenge in soil DNA workflows due to co-extraction of substances like humic acids [28]. Purity ratios, particularly a low A260/A230, can signal this issue [24]. To resolve this:

- Re-purity the DNA: Use silica-column based purification or reagent kits specifically designed to remove soil-derived inhibitors [28] [21].

- Dilute the Template: A simple dilution of the DNA extract can reduce the concentration of inhibitors to a level that no longer affects the polymerase. The optimal dilution factor should be determined empirically.

- Use Inhibitor-Resistant Master Mixes: Specialized PCR buffers are available that can tolerate certain levels of common inhibitors.

Q4: How does my DNA extraction method affect representativity in metabarcoding studies?

The extraction method directly influences which organisms' DNA is recovered from the soil matrix. A study comparing two commercial kits from the same manufacturer found that the kit using a larger soil starting weight (10 g vs. 0.25 g) captured a higher taxonomic richness, whereas the smaller-scale kit captured diversity comparable to DNA from heat-extracted invertebrates [21]. This highlights that the choice of extraction kit and protocol can bias the apparent community structure. For the most comprehensive view, some studies suggest a complementary approach using multiple methods [21].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA Yield | Incomplete cell lysis [26]; Inefficient binding to purification matrix [29]; Inhibitors in soil [28]. | Optimize lysis: combine mechanical (e.g., bead beating [30] [21]) with chemical/enzymatic methods [29]; Use larger soil sample mass (e.g., 10 g) [21]; Add an extra wash step to remove inhibitors pre-binding [29]. |

| Poor DNA Purity (Low A260/A230) | Co-purification of humic acids, chaotropic salts, or other soil contaminants [28] [24]. | Use inhibitor-removal buffers [28]; Ensure wash buffers contain correct ethanol concentration [26]; Repeat silica-column purification [28]; Avoid over-vortexing or harsh mechanical disruption that shears DNA [30]. |

| Highly Fragmented DNA | Overly aggressive mechanical lysis [30]; Natural degradation in environmental sample [30]. | For ancient/degraded samples, use protocols optimized for short fragments [28]; For intact cells, homogenize at lower speeds or for shorter durations [30]; Use a homogenizer with temperature control to minimize heat damage [30]. |

| Non-Representative Community Profile | Lysis method fails to break tough spores or cysts [30]; Extraction kit bias [21]. | Employ a harsher mechanical lysis step (e.g., bead beating with ceramic beads) [30] [21]; Compare multiple extraction methods to validate findings [21]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in DNA Extraction from Soil |

|---|---|

| Power Bead Solution / Silica Beads | Mechanical lysis via bead beating to break open tough microbial and microarthropod cells [30] [28] [21]. |

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | Precipitates polysaccharides and other contaminants common in plant and soil samples [28]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | A strong anionic detergent used in chemical lysis to disrupt lipid membranes [28]. |

| Proteinase K | An enzyme that digests and removes proteins, including nucleases that could degrade DNA [28] [29]. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | A chelating agent that binds metal ions, inactivating DNase enzymes and inhibiting PCR [30] [28]. |

| Silica-based Columns | Selective binding of DNA in the presence of high-salt buffers, allowing for purification from contaminants [28] [26]. |

| Humic Acid Removal Buffers | Specialized reagents designed to bind or neutralize humic substances, common PCR inhibitors in soil [28]. |

| AMG-222 tosylate | AMG-222 tosylate, CAS:1163719-08-1, MF:C39H47N9O6S, MW:769.9 g/mol |

| AMG-3969 | AMG-3969, MF:C21H20F6N4O3S, MW:522.5 g/mol |

Experimental Workflow: From Soil to Quality-Checked DNA

The diagram below outlines a generalized workflow for soil DNA extraction and quality control, incorporating key decision points based on the success metrics.

Key Experimental Protocols for Validation

1. Assessing DNA Concentration and Purity via Spectrophotometry [24] [25]

- Blank Measurement: Use the DNA elution buffer to zero the spectrophotometer.

- Sample Measurement: Measure absorbance at 230nm, 260nm, 280nm, and 320nm (for turbidity correction).

- Calculations:

- Concentration (µg/ml) = (A260 - A320) × Dilution Factor × 50 µg/ml

- Purity (A260/A280) = (A260 - A320) / (A280 - A320)

- Purity (A260/A230) = (A260 - A320) / (A230 - A320)

2. Verifying DNA Integrity and Fragment Size via Agarose Gel Electrophoresis [24] [25]

- Gel Preparation: Prepare a 0.8% - 1.2% agarose gel in 1X TAE or TBE buffer, stained with a safe DNA dye.

- Sample Loading: Mix a small aliquot of DNA with loading dye and load alongside a DNA molecular weight marker.

- Electrophoresis: Run the gel at 5-10 V/cm until bands are sufficiently separated.

- Visualization: Image the gel under UV light. High-quality genomic DNA should appear as a tight, high-molecular-weight band. Smearing indicates degradation.

3. Optimizing for Challenging or Inhibitor-Rich Soils [28] [21]

- Protocol Selection: Consider a sediment-optimized protocol (e.g., using a reagent like Power Beads Solution) coupled with a silica-binding step to maximize recovery of fragmented aDNA and remove humic acid inhibitors [28].

- Scale: For low-biomass samples, using a larger starting mass of soil (e.g., 10 g with a PowerMax kit) can significantly improve the recovery of rare taxa and increase representativity [21].

Methodology in Action: Comparing Commercial Kits and Custom Protocols for Specific Goals

Comparative Analysis of Leading Commercial Soil DNA Kits (e.g., QIAGEN PowerSoil, Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin)

The efficacy of soil microbiome studies is fundamentally dependent on the quality and quantity of DNA extracted from environmental samples. Soil, as a complex and heterogeneous matrix, contains numerous substances—such as humic acids, polysaccharides, phenolic compounds, and cations—that can co-purify with nucleic acids and inhibit downstream molecular analyses like quantitative PCR (qPCR) and next-generation sequencing [19]. The choice of DNA extraction method can introduce significant biases, influencing the observed microbial community structure and potentially leading to erroneous conclusions [31] [32]. This technical guide provides a comparative analysis of leading commercial soil DNA kits, offering detailed protocols, troubleshooting advice, and data-driven recommendations to help researchers optimize their DNA extraction processes for more accurate and reproducible results in soil research.

Kit Performance and Selection Guide

The performance of a DNA extraction kit can vary significantly depending on the specific soil properties and the objectives of the downstream analysis. The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of several leading kits as reported in recent scientific literature.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Commercial Soil DNA Extraction Kits

| Kit Name | Recommended Sample Type | Key Strengths | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIAGEN DNeasy PowerSoil Pro (Kit A) [19] | General soil, complex environmental samples | Effective inhibitor removal; high reproducibility | "Best suitability for reproducible long-read WGS metagenomic sequencing" [32]. |

| Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin Soil (MNS) [31] | Diverse terrestrial ecosystem samples | High alpha diversity recovery; good DNA purity | "Associated with the highest alpha diversity estimates" and provided the best 260/230 purity ratios in most sample types [31]. |

| QIAGEN DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil [21] | Standard soil eDNA metabarcoding (0.25g samples) | Captures diversity comparable to invertebrate-derived DNA | Effective for soil fauna assessment via eDNA, showing results comparable to other methods [21]. |

| QIAGEN DNeasy PowerMax Soil [21] | Low-biomass or large-volume soil samples (10g samples) | Captures higher species richness from larger volumes | "PowerMax captured higher richness" in environmental DNA studies [21]. |

| MP Biomedicals FastDNA SPIN Kit (Kit B) [19] | Fast processing | Rapid protocol with a single washing step | Performance varies with soil type; may be less effective with high-inhibitor soils [19]. |

| Macherey-Nagel Nusoil Kit (Kit C) [19] | Soils with high inhibitor content | Extensive purification with four washing steps and a specific inhibitor removal column | Designed to remove challenging contaminants; multiple wash steps enhance purity [19]. |

Key Selection Criteria

- Soil Type and Inhibitor Content: Soils with high organic matter or clay content often require kits with robust inhibitor removal steps, such as the Macherey-Nagel Nusoil Kit [19].

- Downstream Application: For long-read metagenomic sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore), the QIAGEN PowerSoil Pro Kit has demonstrated superior performance [33] [32]. For 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing aiming to maximize observed diversity, the Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin Soil kit is a strong candidate [31].

- Biomass Availability: For low-biomass samples, kits designed for larger soil volumes, like the QIAGEN PowerMax Soil Kit, can improve recovery [21].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized Evaluation Protocol for Soil DNA Kits

To objectively compare the performance of different DNA extraction kits on your specific soil samples, follow this standardized evaluation protocol.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Soil DNA Extraction Evaluation

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Soil Samples | The test matrix. Include samples with varying properties (e.g., texture, organic matter). |

| Mock Community | A defined mix of known microorganisms (e.g., gram-positive and gram-negative strains) to evaluate extraction bias and efficiency [33] [31]. |

| Lysis Tubes with Beads | For mechanical disruption of tough microbial cell walls (e.g., gram-positive bacteria) and soil aggregates [33] [34]. |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme that digests proteins and degrades nucleases, aiding in cell lysis and protecting released DNA [34]. |

| Inhibitor Removal Solution/Buffer | Chemical solutions that precipitate or bind to common soil inhibitors like humic acids [19]. |

| Silica Membrane Columns / Magnetic Beads | Solid-phase matrices that bind DNA specifically, allowing for washing away of impurities [34] [19]. |

| Ethanol-Based Wash Buffers | Solutions used to remove salts, metabolites, and other contaminants from the bound DNA without eluting it. |

| Elution Buffer (TE or nuclease-free water) | A low-salt buffer or water used to release purified DNA from the silica membrane or magnetic beads. |

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize your soil samples. For a more controlled assessment, split a single soil sample and spike it with a commercial mock community [33].

- Parallel DNA Extraction: Extract DNA from identical aliquots of the prepared sample(s) using the kits you wish to compare. Adhere strictly to each manufacturer's protocol. Include multiple technical replicates for statistical robustness.

- DNA Quality and Quantity Assessment:

- Quantity: Measure DNA concentration using a fluorescence-based method (e.g., Qubit), as it is more accurate for complex mixtures than spectrophotometry [34].

- Purity: Use spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) to determine the 260/280 and 260/230 ratios. Ideal values are ~1.8 and >2.0, respectively. Low ratios indicate contamination with proteins/phenol or humic acids/carbohydrates [34] [31].

- Integrity: Check DNA fragment size using gel electrophoresis or a TapeStation system [34].

- Downstream Analysis:

- qPCR Inhibition Test: Perform qPCR on a conserved gene (e.g., 16S rRNA) using standardized DNA quantities from each kit. Higher Ct values indicate the presence of PCR inhibitors [19].

- Sequencing and Bioinformatics: Subject the DNA extracts to 16S rRNA gene amplicon or shotgun metagenomic sequencing. Analyze the data to compare alpha diversity (richness and evenness), beta diversity (community composition differences), and the recovery of the spiked mock community organisms [33] [31].

This standardized workflow for evaluating DNA extraction kits helps researchers identify the optimal method for their specific soil samples and research goals.

Optimized Protocol for Piggery Wastewater (Adapted from PMC)

The following optimized protocol for a challenging matrix like piggery wastewater, based on the QIAGEN PowerFecal Pro kit, highlights how manufacturer protocols can be modified for enhanced performance [33].

Method: Optimized QIAGEN PowerFecal Pro Protocol Sample Type: Piggery Wastewater (or other complex, inhibitor-rich environmental samples) Workflow:

Key Modifications from Standard Protocol [33]:

- Lysis Buffer Volume: Use 500 µL of CD1 lysis buffer instead of the recommended 800 µL.

- Mechanical Lysis: Extend bead-beating to 10 minutes at maximum speed on a Vortex-Genie 2.

- Wash Step: Perform the wash with solution C5 in two steps of 250 µL each, followed by incubation on ice for 5 minutes and centrifugation.

- Ethanol Removal: After the final wash, leave the spin column lids open for 10 minutes to ensure complete evaporation of residual ethanol before adding elution buffer.

- Elution Volume: Elute DNA in a small volume of 50 µL to increase final concentration.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My DNA yields are consistently low. What could be the cause and how can I improve this? A1: Low yields can result from incomplete cell lysis or DNA loss during purification. Ensure efficient mechanical lysis by using bead-beating, which is crucial for disrupting tough gram-positive bacterial cells [34] [31]. If your sample has low microbial biomass, consider using a kit designed for larger sample masses, such as the QIAGEN PowerMax Soil Kit, which processes up to 10 g of soil [21]. Also, confirm that you are not over-drying the silica membrane after washing, as this can reduce DNA elution efficiency.

Q2: My downstream PCR or qPCR reactions are inhibited. How can I better remove inhibitors? A2: The presence of co-extracted contaminants like humic acids is a common issue. Choose a kit with dedicated inhibitor removal steps, such as the Macherey-Nagel Nusoil Kit, which includes a specific inhibitor removal column [19]. You can also incorporate additional purification steps, such as using a kit with more extensive wash buffers (e.g., four washes in Kit C vs. one in Kit B) [19]. Furthermore, evaluate the 260/230 ratio; a low ratio indicates the presence of organic contaminants, and diluting the DNA template in the PCR reaction can sometimes help overcome mild inhibition.

Q3: How does the DNA extraction method affect my perceived microbial community composition? A3: The extraction method is a major source of bias. Different lysis methods (mechanical vs. enzymatic) can favor the recovery of certain taxa over others. For instance, kits without rigorous mechanical lysis may under-represent gram-positive bacteria [34] [31]. This bias can significantly impact alpha and beta diversity estimates. To account for this, it is critical to use the same DNA extraction kit throughout a study when comparing samples. For methodological development, using a mock community can help quantify these biases [33].

Q4: My DNA is sheared and not suitable for long-read sequencing. What should I check? A4: Excessive or harsh mechanical lysis can fragment genomic DNA. While bead-beating is necessary for cell disruption, optimizing the duration and intensity is key. The QIAGEN PowerSoil Pro Kit has been specifically noted for producing DNA with good integrity for long-read metagenomic sequencing [32]. Also, avoid excessive vortexing or pipetting of the lysate after the initial lysis step. Checking the DNA fragment size distribution using a TapeStation or similar instrument before proceeding with library preparation is highly recommended.

Q5: We process diverse sample types (soil, feces, water). Should we use a different kit for each? A5: While some kits are optimized for specific matrices, using a single kit for multiple sample types can reduce technical variation, making results more comparable. The Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin Soil kit, for example, has been shown to perform well across a range of terrestrial ecosystem samples, including bulk soil, rhizosphere soil, invertebrate taxa, and mammalian feces, and is associated with high alpha diversity recovery [31]. Standardizing on one well-performing, versatile kit is often preferable for cross-environmental studies.

Within the broader scope of research aimed at optimizing DNA extraction from soil samples, the bead beating process is a critical step for accessing the genetic material of a representative microbial community. Soil represents one of the most complex and challenging matrices from which to extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA. The efficacy of DNA extraction directly influences downstream analyses, including metabarcoding, metagenomic sequencing, and the construction of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [11] [35]. Mechanical lysis via bead beating is widely recognized for enhancing DNA yield and improving the representation of tough-to-lyse microorganisms, such as Gram-positive bacteria, which have rigid, multi-layered peptidoglycan cell walls [36] [37]. However, this method presents a fundamental trade-off: while insufficient lysis leads to low DNA yield and under-representation of resistant taxa, excessive lysis force or duration can cause severe DNA shearing, compromising its integrity and suitability for long-read sequencing technologies [11]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help researchers navigate the optimization of bead beating parameters—time, speed, and bead matrix selection—to achieve balanced and high-performance DNA extraction from diverse soil types.

Troubleshooting Common Bead Beating Issues

Q1: My soil DNA extraction is yielding sufficient quantity but the DNA is heavily sheared, making it unsuitable for long-read sequencing. What should I adjust?

- Problem: Excessive DNA fragmentation due to overly aggressive mechanical lysis.

- Investigation: Check the mean fragment length of your DNA using a bioanalyzer, TapeStation, or agarose gel electrophoresis. Compare your results with the input requirements of your intended long-read sequencing platform.

- Solution: Systematically reduce the homogenization intensity. A statistical Design of Experiments (DoE) approach has demonstrated that lower energy input into mechanical lysis significantly improves DNA integrity.

- Speed & Time: For a benchtop homogenizer, reducing the speed to 4 m sâ»Â¹ for 10 seconds has been shown to increase the mean DNA fragment length by approximately 70% compared to manufacturer's standard recommendations (e.g., 6 m sâ»Â¹ for 30 s) [11].

- Result: This optimized setting produced longer sequenced reads (N50) and longer contiguous sequences after assembly without introducing significant bias in microbial community composition [11].

Q2: I am consistently missing tough-to-lyse Gram-positive bacteria in my soil microbiome profiles. How can I improve their recovery?

- Problem: Incomplete lysis of microorganisms with robust cell walls, leading to biased community representation.

- Investigation: Review your current lysis method. If you are using only chemical lysis or a single bead type, your protocol may be insufficient for resistant cells.

- Solution: Optimize your bead beating strategy to enhance cell disruption.

- Bead Material and Size: A combination of grinding beads of different sizes has proven superior for recovering a wider diversity of taxa. One study on organic-rich sub-seafloor sediments found that a mixture of 0.5-mm and 0.1-mm glass beads yielded higher DNA quantities and recovered more unique taxa, including certain Gammaproteobacteria and Fusobacteria, compared to other combinations [36]. The study also cautioned that using only small beads may lead to an underestimation of some Gram-positive strains [36].

- Bead Beating Cycles: For pure cultures of Gram-positive bacteria, an optimized protocol using three bead beating cycles with glass beads significantly improved RNA yields (over 6- to 15-fold) while maintaining integrity [37]. This principle can be adapted for DNA extraction from soil to increase the lysis efficiency of resistant cells.

Q3: My DNA yield is unacceptably low, even though I am using a powerful bead beater. What are the potential causes?

- Problem: Inefficient cell lysis or DNA binding, resulting in low yield.

- Investigation: Confirm that your sample is being properly homogenized. Visually inspect the sample tubes after bead beating for incomplete mixing or intact material.

- Solution:

- Verify Bead and Sample Consistency: Ensure the sample is a fine slurry and that the beads are moving freely during beating. Overly thick or dry samples will not lyse efficiently.

- Review Bead Matrix: As above, using an optimized mix of bead sizes (e.g., 0.5-mm and 0.1-mm) can dramatically improve lysis efficiency and DNA yield from complex samples [36].

- Check for Over-drying: If your protocol includes an air-drying step for a pellet, over-drying can make DNA very difficult to resuspend, leading to low measured yields. Air-dry pellets briefly (≤5 minutes) and avoid vacuum drying with heat [38] [39].

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Optimizing Bead Beating for Long-Read Sequencing from Soil

This protocol is adapted from a statistical design of experiments (DoE) approach aimed at maximizing DNA fragment length for long-read sequencing while maintaining adequate yield and community representation [11].

- Objective: To obtain high-molecular-weight DNA from soil for long-read sequencing platforms (e.g., Oxford Nanopore Technologies, PacBio).

- Materials:

- Soil sample (0.25 g is often sufficient for temperate agricultural soils) [40].

- Commercial soil DNA extraction kit (e.g., Qiagen PowerSoil Pro Kit).

- Benchtop homogenizer (e.g., FastPrep-24).

- 2 ml lysing matrix tubes.

- Method:

- Sample Preparation: Transfer 0.25 g of soil to a 2 ml lysing matrix tube.

- Add Lysis Buffer: Add the appropriate lysis buffer from your kit to the tube.

- Mechanical Lysis: Homogenize the sample at 4 m sâ»Â¹ for 10 seconds.

- Complete Extraction: Continue with the remainder of the manufacturer's DNA extraction protocol (incubation, centrifugation, binding, washing, and elution).

- Key Findings: This low-intensity lysis setting was found to be the optimal balance, increasing DNA fragment length by 70% compared to standard protocols without significantly altering the observed microbial community structure [11].

Protocol: Enhanced Lysis for Diverse Microbial Communities

This protocol is designed to maximize the recovery of a broad range of microorganisms, including tough-to-lyse Gram-positive bacteria, from complex, organic-rich soil and sediment samples [36].

- Objective: To improve DNA yield and taxonomic diversity from challenging environmental samples.

- Materials:

- Soil or sediment sample.

- Commercial DNA extraction kit (e.g., FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil).

- Bead beater.

- Custom grinding bead mixture.

- Method:

- Prepare Bead Matrix: Instead of relying solely on the beads provided in a kit, prepare a tube containing a mixture of 0.6 g of 0.1-mm glass beads and 0.6 g of 0.5-mm glass beads (total 1.2 g) [36].

- Add Sample and Buffer: Combine your soil sample and lysis buffer with this custom bead matrix.

- Mechanical Lysis: Process the samples in a bead beater according to your established parameters (e.g., 6 m sâ»Â¹ for 30-45 s).

- Complete Extraction: Proceed with the standard kit protocol for the remaining steps.

- Key Findings: This bead combination provided higher DNA yields and recovered more unique microbial taxa than other bead combinations, including the proprietary ceramic/silica/glass mix of a commercial kit [36].

Data Presentation: Optimized Parameters

The following tables consolidate quantitative data from key studies to guide parameter selection.

Table 1: Optimized Bead Beating Parameters for Different Soil Research Goals

| Research Goal | Recommended Speed & Time | Recommended Bead Matrix | Key Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Read Sequencing (Maximize DNA length) | 4 m sâ»Â¹ for 10 s | Kit-standard beads | 70% increase in mean fragment length; sufficient yield for library prep. | [11] |

| Max Community Diversity (Organic-rich soils) | Standard speed (e.g., 6 m sâ»Â¹) | Mix of 0.5-mm & 0.1-mm glass beads | Higher DNA yield and recovery of more unique taxa vs. single-size beads. | [36] |

| Lysis of Gram-Positive Bacteria | Multiple cycles (e.g., 3 cycles) | Glass beads | Significantly improved nucleic acid yields (6- to 15-fold) from resistant cells. | [37] |

Table 2: Effect of Homogenization Intensity on DNA Yield and Fragment Length [11]

| Homogenization Speed (m sâ»Â¹) | Homogenization Time (s) | Approx. Distance Travelled (m) | DNA Yield (Total µg) | Mean Fragment Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 5 | 20 | ~2.5 | ~9,324 |

| 4 | 10 | 40 | ~4.0 | ~7,487 |

| 6 | 30 | 180 | ~7.5 | ~4,406 |

| 8 | 40 | 960 | ~10.0 | ~3,418 |

Workflow and Decision Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Bead Beating Optimization

| Item | Function / Application | Considerations for Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Glass Beads (0.1-mm) | Efficiently disrupts small and tough-to-lyse microbial cells. | Best used in combination with larger beads. Using alone may underestimate some taxa. [36] |

| Glass Beads (0.5-mm) | Provides larger impact energy for breaking cell clumps and tougher walls. | A mixture of 0.5-mm and 0.1-mm beads is recommended for maximal diversity. [36] |

| Ceramic/Silica Beads | Often included in commercial kits; dense material for effective grinding. | Compare performance against optimized glass bead mixtures for your specific soil type. |

| Bead Beater / Homogenizer | Provides consistent mechanical lysis. | Must allow control of speed (m sâ»Â¹) and time (s). Low energy input (4 m sâ»Â¹) favors long DNA fragments. [11] |

| Commercial Soil DNA Kit | Standardizes chemical lysis, binding, washing, and elution. | Kits like Qiagen PowerSoil are widely used. The starting soil weight (e.g., 0.25 g) may be sufficient, ensuring methodological consistency. [40] |

| Proteinase K | Enzymatic digestion of proteins, aiding cell lysis and removing contaminants. | Particularly important for samples with high organic content or humic acids. |

| AMG8380 | AMG8380, CAS:1642112-31-9, MF:C25H16ClF2N3O5S, MW:543.92 | Chemical Reagent |

| Aminooxy-PEG2-azide | Aminooxy-PEG2-azide, MF:C6H14N4O3, MW:190.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Within the context of optimizing DNA extraction from soil samples, obtaining high-quality data from long-read sequencing technologies is paramount. Soil samples present unique challenges, including the presence of inhibitors and difficult-to-lyse microorganisms, which can compromise the integrity and length of the extracted DNA. This technical support guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice and detailed protocols to help researchers overcome these obstacles, maximize read lengths, and achieve superior genome assemblies using platforms from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the most critical factor for successful long-read sequencing from soil samples? The most critical factor is the quality and integrity of the input DNA. For long-read sequencing, the DNA must be High Molecular Weight (HMW) and minimally degraded. It is recommended that at least 50% of the DNA is above 15 kb in length for optimal results. The DNA must also be free of common contaminants from the soil matrix, such as humic acids, which can inhibit downstream library preparation [41].

2. Which DNA extraction method is best for soil samples intended for long-read sequencing? Optimized commercial kits designed for environmental samples are generally most effective. One comparative study on complex environmental wastewater found that an optimized QIAGEN PowerFecal Pro protocol was the most suitable and reliable, providing high-quality bacterial DNA suitable for Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) sequencing [33]. Another resource recommends kits like the MP Biomedicals SPINeasy DNA Kit for Soil, which uses a unique lysing matrix and proprietary buffers to remove inhibitors and protect DNA integrity [42].

3. How should I preserve soil samples in the field if immediate freezing is not possible? If access to a -20°C or -80°C freezer is logistically challenging, drying with silica gel packs has been demonstrated as a cost-effective and easily applied method for short-term storage at room temperature. Research shows that this method leads to no significant differences in DNA concentration and microbial community structure compared to immediate extraction or freezing [43].

4. How much sequencing coverage do I need for a de novo genome assembly? For robust de novo genome assembly using long-read technologies, a coverage of 100x is recommended. For germline or frequent variant analysis, 20-50x coverage may be sufficient, while somatic or rare variant detection requires higher coverage, around 100x [41].

5. What are the current accuracy levels of modern long-read sequencing? This is a common area of misconception. Modern PacBio HiFi sequencing achieves a typical accuracy of >99.9% (Q20). According to Oxford Nanopore's specifications for current chemistry and flow cells, raw read accuracy is also >Q20 (>99%), with consensus accuracy typically greater than 99.99% [41] [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low DNA Yield and Purity from Soil Samples

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient lysis of tough microbial cells.

- Solution: Implement a robust mechanical homogenization step. Using an instrument like the Bead Ruptor Elite with a specialized lysing matrix (e.g., containing ceramic or stainless-steel beads) can efficiently disrupt difficult-to-lyse bacteria [33] [42]. Ensure homogenization parameters are optimized to balance effective lysis with minimizing DNA shearing.

- Cause: Co-extraction of inhibitors like humic acids.

- Solution: Use DNA extraction kits specifically designed for soil that include proprietary inhibitor removal systems [42]. After extraction, assess purity with spectrophotometry; the 260/280 ratio should be above 1.8, and the 260/230 ratio should fall between 2.0 and 2.2. If contaminated, clean up the sample using a Qiagen cleanup kit or AMPure XP beads [41].

- Cause: Suboptimal sample preservation before DNA extraction.

Problem: Short Read Lengths and Poor Assembly Quality

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: DNA fragmentation during extraction or handling.

- Cause: Presence of short DNA fragments in the final library.

- Solution: Perform a size-selection clean-up post-extraction. One effective protocol involves using a 4X diluted SPRISelect beads (35% volume by volume) to remove fragments smaller than 3-4 kb. This will enrich for longer fragments, improving assembly continuity, though it will reduce total DNA quantity [41].

- Cause: Insufficient sequencing coverage or data quality.

- Solution: Ensure you are generating enough data (e.g., 100x coverage for de novo assembly). For ONT, use the latest basecalling software (e.g., Dorado) to improve read accuracy. For all data, perform rigorous quality control (QC) using tools like LongQC or NanoPack to assess read length distribution and base quality before proceeding with assembly [45].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Comparative Analysis of DNA Extraction Methods for Complex Samples

The following table summarizes a methodology for evaluating DNA extraction kits, adapted from a study on piggery wastewater [33].

Objective: To identify the most effective DNA extraction method for obtaining high-quality, long-read sequencing data from a complex environmental matrix.

Methodology Summary:

- Samples: Pig farm wastewater (can be substituted with other complex environmental samples).

- Tested Kits: Six DNA extraction protocols, including QIAGEN QIAamp PowerFecal Pro (PF), QIAGEN DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil, and Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin Soil.

- Evaluation Criteria: Initial assessment based on DNA yield and quality.

- Spike-in Community: The top-performing methods are further tested on samples spiked with a known mock community of pathogens.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Sequenced on ONT MinION platform; effectiveness evaluated using the kraken2 taxonomic classifier and an in-house database.

Results Summary: The optimized QIAGEN PowerFecal Pro protocol was identified as the most suitable and reliable, demonstrating the importance of kit selection for effective pathogen surveillance in a complex matrix [33].

Long-Read Sequencing Platform Comparison

The table below summarizes key specifications of the two dominant long-read sequencing technologies to aid in platform selection [45] [46].

| Feature | Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) HiFi | Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 10-20 kb [46] | 10-60 kb (long); up to 100-200 kb (ultra-long) [46] |

| Read Accuracy | >99.9% (Q20) [44] | >99% (Q20) for current chemistries [41] |

| Primary Data Type | Circular Consensus Sequencing (HiFi reads) | Raw electrical signal (squiggles) basecalled to sequences |

| DNA Input | Higher input requirements [45] | Lower input requirements [45] |

| Methylation Detection | Yes, from native DNA | Yes, directly from native DNA |

| Strengths | Very high single-read accuracy, uniform coverage | Extremely long reads, real-time analysis, portability |

Workflow for Soil DNA Extraction and Long-Read Sequencing

The following diagram illustrates the complete optimized workflow, from sample collection to data analysis, integrating the protocols and recommendations discussed above.

Key Steps Explained:

- Field Preservation: Preserve sample integrity using silica gel drying (for room temperature) or flash-freezing at -80°C [43] [30].

- DNA Extraction & Purification: Use inhibitor-removal kits (e.g., QIAGEN PowerFecal Pro or MP Bio SPINeasy) with mechanical homogenization [33] [42].

- Quality Control (QC) 1: Quantify DNA concentration using fluorescence-based methods (e.g., Qubit). Assess purity via spectrophotometry (260/280 and 260/230 ratios). Check DNA size distribution using capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Fragment Analyzer) [41].

- Size Selection & Cleanup: Use magnetic bead-based clean-up (e.g., diluted SPRISelect beads) to remove short fragments and enrich for HMW DNA [41].

- Quality Control (QC) 2: Re-quantify the size-selected DNA to ensure sufficient material for library preparation.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Follow manufacturer protocols for PacBio or ONT, using the recommended DNA input for the chosen platform [45].

- Data Analysis & Assembly: Perform basecalling/demultiplexing, followed by quality control (LongQC, NanoPack), and proceed with genome assembly or variant calling using specialized long-read tools [45].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Equipment

The following table lists essential materials and their functions for successful long-read sequencing from challenging samples like soil.

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| QIAGEN PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | DNA extraction kit optimized for complex environmental samples; effective for removing PCR inhibitors like humic acids [33]. |

| MP Biomedicals SPINeasy DNA Kit | Soil DNA extraction kit featuring a unique Lysing Matrix E for thorough cell lysis and a proprietary inhibitor removal system [42]. |

| FastPrep Homogenizer | Instrument for rapid mechanical lysis (≤40 seconds) of tough samples, including soil and difficult-to-lyse bacteria [42]. |

| Bead Ruptor Elite Homogenizer | Provides precise control over homogenization parameters (speed, cycle duration) to maximize DNA recovery while minimizing shearing [30]. |

| SPRISelect / AMPure XP Beads | Magnetic beads used for post-extraction DNA clean-up and size selection to remove short fragments and salts [41]. |

| Dry & Dry Silica Gel Packs | Cost-effective desiccant for room-temperature preservation of soil samples, shown to maintain microbial DNA integrity [43]. |

| Qubit Fluorometer | Fluorescence-based instrument for accurate DNA quantification, preferred over spectrophotometry for HMW DNA [41] [43]. |

| Fragment Analyzer / Bioanalyzer | Capillary electrophoresis systems for qualitative assessment of DNA size distribution and integrity [41]. |

| Aminooxy-PEG3-azide | Aminooxy-PEG3-azide, MF:C8H18N4O4, MW:234.25 g/mol |

| Aminooxy-PEG4-azide | Aminooxy-PEG4-azide, CAS:2100306-61-2, MF:C10H22N4O5, MW:278.31 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issue 1: Low DNA Yield

Low DNA yield can halt downstream experiments and is a frequent challenge, particularly with complex samples like soil.

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Cell Lysis | Tough cell walls (e.g., in Gram-positive bacteria or plant tissues) prevent DNA from being released. [47] [48] | For soil and plants, combine physical and chemical methods: use bead beating with a robust lysis matrix and extend incubation time with lysis buffer. [49] [48] |

| DNA Pelt Over-drying | Over-dried DNA pellets, especially when using vacuum suction, become difficult or impossible to resuspend, leading to low yield. [38] | Air-dry pellets for less than 5 minutes. If the pellet is overdried, try rehydrating it with buffer and incubating at 37-55°C with periodic pipetting. [38] |

| Inhibitor Carry-over | Soil samples often contain humic acids, which can co-purity with DNA and inhibit downstream PCR. [47] | Use extraction methods designed for complex samples, such as the CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method, which effectively separates polysaccharides and polyphenols from DNA. [47] [48] |

| Sample Age and Degradation | Using old or improperly stored samples leads to DNA degradation by nucleases. [49] | Process samples immediately or freeze them at -80°C. For blood, use fresh samples within a week or add DNA stabilizing reagents. [49] |

Common Issue 2: Poor DNA Purity

Impure DNA with contaminants can severely inhibit sensitive applications like qPCR and sequencing.

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Contamination | Incomplete digestion or precipitation of proteins results in a low A260/A280 ratio. [38] [48] | Ensure sufficient Proteinase K digestion time and temperature. For salting-out methods, ensure adequate saturation. A second precipitation or phenol extraction may be needed. [38] [48] |

| Phenol or Reagent Carry-over | Residual phenol from extraction can absorb at A280, lowering the A260/A280 ratio and inhibiting enzymes. [38] | Perform additional ethanol precipitation steps to remove leftover phenol and salts. Ensure the final wash with 70% ethanol is complete. [38] |

| Polysaccharide Contamination | Plant and soil samples are rich in polysaccharides that co-precipitate with DNA, creating a viscous, impure solution. [47] | Optimize protocols with high-salt buffers (e.g., CTAB) to differentially precipitate polysaccharides. Adding PVP (polyvinylpyrrolidone) can help adsorb polyphenols. [47] |

| Hemoglobin Contamination | In blood samples, incomplete lysis of red blood cells can lead to hemoglobin contamination, clogging spin filters and reducing purity. [49] | Extend the lysis incubation time by 3–5 minutes. If precipitates form, remove them by centrifugation before applying the lysate to a purification column. [49] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the most important factor for successful DNA extraction from soil samples for pathogen detection?

The single most critical factor is effective and tailored cell lysis. Soil is a complex matrix containing diverse microorganisms with tough cell walls (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria, spores) and potent PCR inhibitors (e.g., humic acids). A generic lysis protocol will fail to release DNA from all microbial targets. Success requires a combination of physical disruption (e.g., bead beating) to break open resilient cells and chemical lysis with inhibitor-removing reagents (e.g., CTAB) to ensure the resulting DNA is pure and amplifiable in downstream qPCR. [47] [48]

How can I tell if my DNA extraction failed due to degradation versus the presence of inhibitors?

You can distinguish between these two issues through a combination of analysis techniques:

- Agarose Gel Electrophoresis: Degraded DNA will appear as a low molecular weight smear with no distinct high molecular weight band. DNA with inhibitors may look intact but will fail in enzymatic assays. [49] [48]

- Spectrophotometry (A260/A280 and A260/A230): While A260/A280 indicates protein contamination, the A260/A230 ratio is more sensitive to contaminants like salts, carbohydrates, and phenol. A low A260/A230 ratio (<2.0) often signals the presence of inhibitors. [38]

- Downstream PCR/qPCR Failure: Inhibited DNA typically causes reactions to fail completely (no amplification), or show abnormally high Ct values. Degraded DNA may amplify for small targets but fail for larger amplicons. [50]

My qPCR for pathogen detection shows inconsistent results. Could my DNA extraction method be the cause?

Yes, inconsistency in qPCR is frequently traced back to DNA extraction. The primary culprits are:

- Variable Lysis Efficiency: Inconsistent bead beating or homogenization across samples leads to different yields from the same starting material. [49]

- Inhibitor Carry-over: Fluctuating levels of co-extracted inhibitors (e.g., from soil) can cause variable PCR suppression, leading to inconsistent Ct values. [50] [47]