Navigating the Noise: A Researcher's Guide to Identifying and Overcoming Sequencing Artifacts in Microbial Genomics

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals tackling the pervasive challenge of sequencing artifacts in microbial data.

Navigating the Noise: A Researcher's Guide to Identifying and Overcoming Sequencing Artifacts in Microbial Genomics

Abstract

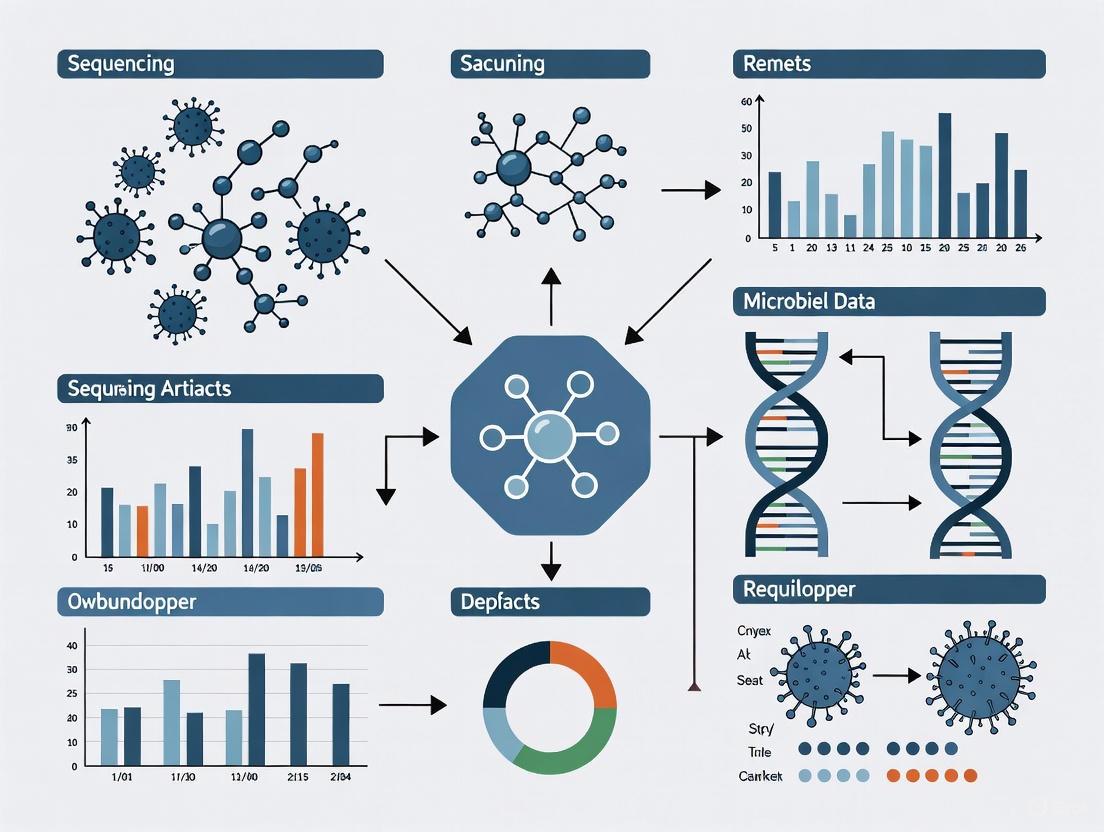

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals tackling the pervasive challenge of sequencing artifacts in microbial data. Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, it explores the origins and impacts of technical errors from sample preparation to bioinformatic analysis. The content synthesizes the latest methodological advances, including long-read sequencing and AI-powered tools, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing workflows. Through a critical evaluation of benchmarking studies and validation techniques, this guide equips scientists with the knowledge to enhance data fidelity, improve reproducibility in microbiome research, and accelerate the translation of genomic insights into reliable clinical and therapeutic applications.

Unraveling the Source: A Deep Dive into the Origins and Impact of Sequencing Artifacts

FAQs: Understanding and Troubleshooting Sequencing Artifacts

1. What are the most common sources of error in PCR before sequencing? PCR introduces several types of errors that can affect downstream sequencing results. The major sources include:

- PCR Stochasticity: The random sampling of molecules during amplification is a major force skewing sequence representation, especially in low-input samples like single-cell sequencing [1].

- Polymerase Errors: DNA polymerase can misincorporate bases during replication. While common in later PCR cycles, these errors often remain at low copy numbers [1] [2].

- Template Switching: This process can create novel chimeric sequences when a polymerase switches templates during amplification. It is a recognized source of inaccuracies, though often confined to low copy numbers [1] [2].

- PCR-Mediated Recombination: This occurs when partially extended primers anneal to homologous sequences in later cycles, generating artificial chimeras. Studies have found it can occur as frequently as base substitution errors [2].

- DNA Damage: Non-enzymatic DNA damage introduced during thermocycling can be a significant contributor to mutations in amplification products, particularly when using high-fidelity polymerases [2].

2. How do base-calling inaccuracies manifest in long-read sequencing technologies like nanopore sequencing? Base-calling inaccuracies in nanopore sequencing are often systematic and can be strand-specific. Common artifacts include:

- Repeat-Calling Errors in Telomeres: For example, human telomeric repeats

(TTAGGG)nare frequently miscalled as(TTAAAA)non one strand, while the reverse complement(CCCTAA)nis miscalled as(CTTCTT)nor(CCCTGG)n. These errors arise due to high similarity in the ionic current profiles between different 6-mers [3]. - Methylation-Induced Errors: Modified bases like 5-methylcytosine have a unique current signature that can cause basecallers to misclassify bases within a methylation motif (e.g.,

Gm6ATC), leading to systematic mismatches [4]. - Homopolymer Errors: Stretches of identical bases (homopolymers) are challenging because the unchanging current makes it difficult to call the exact length accurately. Homopolymers longer than 9 bases are often truncated by a base or two, potentially causing frameshifts [4].

3. What are the key validation parameters for a clinical NGS test to ensure it is fit-for-purpose? Validating a clinical NGS test requires demonstrating its performance across several key parameters [5]:

- Analytical Sensitivity: The test's ability to correctly identify true positive mutations.

- Analytical Specificity: The test's ability to correctly identify true negative results.

- Accuracy: The degree of agreement between the test's sequence data and a known reference sequence.

- Precision: The reproducibility of the results when the test is repeated.

- Reportable Range: The specific regions of the genome where the test can generate sequence data of acceptable quality.

4. My NGS library yield is low. What are the most likely causes? Low library yield can stem from issues at multiple steps in the preparation workflow [6]:

- Poor Input Sample Quality: Degraded DNA/RNA or contaminants like phenol, salts, or EDTA can inhibit enzymatic reactions.

- Fragmentation or Tagmentation Inefficiency: Over- or under-fragmentation will reduce the number of fragments in the desired size range for ligation.

- Suboptimal Adapter Ligation: An incorrect adapter-to-insert molar ratio, poor ligase performance, or suboptimal reaction conditions can drastically reduce yield.

- Overly Aggressive Purification: Incorrect bead-based clean-up ratios or over-drying beads can lead to significant sample loss.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting PCR Artifacts

Problem: Suspected chimeric sequences or skewed sequence representation in data from amplified samples.

Investigation and Solutions:

- Experimental Design:

- Data Analysis:

- Utilize Chimera Detection Tools: For metagenomics or 16S rRNA sequencing, use specialized bioinformatics tools designed to detect and remove chimeric sequences from your dataset [1].

- Account for Stochasticity: Be aware that in low-input experiments, PCR stochasticity is a major factor and can lead to significant quantitative distortions [1].

Guide 2: Addressing Nanopore Base-Calling Errors

Problem: Systematic mismatches in aligned sequencing data, particularly in repetitive regions or known modification sites.

Investigation and Solutions:

- Wet-Lab Protocol:

- Sequence to Appropriate Depth: Ensure sufficient coverage to empower downstream bioinformatic correction [4].

- Bioinformatic Correction:

- Re-basecall with Different Models: Re-running basecalling with updated or alternative models (e.g., Guppy's High-Accuracy "HAC" mode over "Fast" mode) can significantly improve accuracy, especially in strand-specific recovery [3].

- Use Methylation-Aware Pipelines: If studying organisms with known methylation patterns, use assembly polishing algorithms that are trained to recognize and correct for methylation-induced systematic errors [4].

- Manual Inspection of Homopolymers: For critical homopolymer regions, be aware that the called length may be inaccurate and may require manual correction based on experimental context [4].

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Low NGS Library Yield

Problem: Final library concentration is unexpectedly low after preparation.

Investigation and Solutions [6]:

- Verify Input Sample Quality:

- Method: Use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) over UV absorbance (NanoDrop) for accuracy. Check purity via 260/280 and 260/230 ratios.

- Solution: Re-purify the input sample if contaminants are suspected or if ratios are suboptimal (target 260/280 ~1.8, 260/230 > 1.8).

- Optimize Fragmentation:

- Method: Analyze fragmented DNA on a BioAnalyzer or TapeStation to visualize the size distribution.

- Solution: Adjust fragmentation time, energy, or enzyme concentration to achieve the desired fragment size distribution for your library prep kit.

- Titrate Adapter Concentration:

- Method: Test a range of adapter-to-insert molar ratios in a ligation test reaction.

- Solution: Identify the optimal ratio that maximizes ligation efficiency while minimizing the formation of adapter dimers.

- Review Clean-up Steps:

- Method: Double-check bead-based clean-up protocols, including bead-to-sample ratios and incubation times.

- Solution: Avoid over-drying beads, which makes resuspension inefficient. Precisely follow manufacturer instructions for buffer volumes and washing steps.

Data Presentation

| Error Type | Frequency / Error Rate | Key Characteristics | Impact on Sequencing Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Stochasticity | Major source of skew in low-input NGS [1] | Random sampling of molecules during amplification; not sequence-specific | Skews sequence representation and quantification; major concern for single-cell sequencing |

| Polymerase Base Substitution | Varies by polymerase: ~10â»âµ to 2x10â»â´ errors/base/doubling (Taq polymerase) [2] | Depends on polymerase fidelity (proofreading activity), dNTP concentration, buffer conditions | Introduces false single-nucleotide variants (SNVs); errors can propagate through cycles |

| PCR-Mediated Recombination | Can be as frequent as base substitutions; up to 40% in amplicons from mixed templates [2] | Generates chimeric sequences; facilitated by homologous regions and partially extended primers | Causes species misidentification (16S sequencing); incorrect genotype assignment (HLA genotyping) |

| Template Switching | Rare and confined to low copy numbers [1] | Can occur during a single extension event; induced by structured DNA elements | Creates novel, hybrid sequences that are not biologically real |

| DNA Damage | Can exceed error rate of high-fidelity polymerases (e.g., Q5) [2] | Non-enzymatic; introduced during thermocycling | Contributes to background mutation rate in amplification products |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Sequencing Workflow | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | PCR amplification prior to sequencing; target enrichment. | Select polymerases with proofreading (3'-5' exo) activity to minimize base substitution errors [2]. |

| Methylation-Aware Assembly Software | Bioinformatic correction of nanopore data. | Essential for resolving systematic base-calling errors in methylated motifs (e.g., Dam, Dcm in E. coli) [4]. |

| Fluorometric Quantification Kits (Qubit) | Accurate quantification of DNA/RNA input and final libraries. | More accurate than UV spectrometry for quantifying nucleic acids in complex buffers; prevents over/under-estimation [6]. |

| Size Selection Beads | Purification and size selection of NGS libraries. | Critical for removing adapter dimers and short fragments; ratio of beads to sample determines size cutoff [6]. |

| Reference Standard Materials (e.g., GIAB) | Benchmarking and validating sequencing workflow accuracy. | Provides a ground truth for establishing analytical validity, especially for clinical tests [7]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing PCR Polymerase Fidelity by Sequencing

This protocol outlines a method to evaluate error rates of different DNA polymerases, as described in studies using single-molecule sequencing [2].

Key Materials:

- Template DNA: A well-characterized, clonal DNA template (e.g., a plasmid containing a target gene like lacZ).

- DNA Polymerases: The polymerases to be tested (e.g., Taq, Q5).

- PCR Reagents: dNTPs, appropriate reaction buffers.

- Sequencing Platform: A platform capable of single-molecule sequencing (e.g., PacBio SMRT sequencing) or an Illumina-based method with unique molecular indexes (UMIs).

Methodology:

- Amplification: Perform PCR amplification of the target gene from the template using each polymerase under test. Use a minimal number of cycles (e.g., 25 cycles) to avoid excessive error propagation.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries directly from the PCR products. For PacBio SMRT sequencing, this allows for circular consensus sequencing (CCS) to generate highly accurate reads for each molecule [2] [3]. For Illumina, incorporate UMIs prior to amplification to distinguish true PCR errors from sequencing errors [2].

- Data Analysis:

- PacBio: Generate consensus sequences for each circular read and align to the reference template. Identify any mismatches as potential polymerase errors.

- Illumina with UMIs: Group reads by their UMI, generate a consensus sequence for each original molecule, and compare to the reference.

- Error Rate Calculation: Calculate the error rate as (Total Errors) / (Total Bases Sequenced). To compare different polymerases, normalize by the number of doublings: errors per base per doubling.

Protocol 2: Validating a Bioinformatics Workflow for Microbial Characterization

This protocol is adapted from validation strategies for whole-genome sequencing (WGS) workflows used in public health for pathogen characterization [8].

Key Materials:

- Validation Dataset: A set of microbial isolates (e.g., 100+ E. coli isolates) that have been extensively characterized using conventional molecular methods (e.g., PCR, Sanger sequencing) for attributes like AMR genes, virulence factors, and serotype.

- Sequencing Data: Whole-genome sequencing data (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) for all isolates in the validation set.

- Bioinformatics Workflow: The pipeline to be validated, which may include tools for assembly, AMR prediction, virulence gene detection, and serotyping.

Methodology:

- Run Bioinformatics Workflow: Process the WGS data of the validation isolates through the bioinformatics pipeline to generate in-silico predictions for all assays (AMR, virulence, etc.).

- Compare to Ground Truth: Compare the WGS-based predictions to the results from the conventional methods. Categorize results into True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN).

- Calculate Performance Metrics:

- Sensitivity = TP / (TP + FN)

- Specificity = TN / (TN + FP)

- Accuracy = (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN)

- Precision = TP / (TP + FP)

- Establish Performance Thresholds: The workflow is considered validated for a given assay if the performance metrics (e.g., sensitivity, specificity) meet predefined thresholds (commonly >95% for clinical or high-quality public health applications) [8].

Workflow Diagrams

PCR Error Formation Pathways

NGS Library Prep Troubleshooting Logic

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and error modes of Illumina, PacBio, and Oxford Nanopore sequencing platforms, particularly in the context of 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing for microbiome research.

| Platform | Primary Error Mode | Reported Raw Read Accuracy | Strengths | Key Challenges for Microbiome Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina (e.g., MiSeq, NextSeq) | Substitution errors (<0.1% error rate) [9]; Cluster generation failures [10] | >99.9% [9] | High accuracy; High throughput; Excellent for genus-level profiling [11] [9] | Shorter reads limit species-level resolution [11] [9]; GC bias [12] |

| PacBio (HiFi) | Relatively random errors, corrected via CCS [12] | >99.9% (after CCS) [13] | Long reads; High-fidelity (HiFi); Least biased coverage [12]; Excellent for full-length 16S [11] | Lower throughput; Requires more input DNA |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) | Deletions in homopolymers; Errors in specific motifs (e.g., CCTGG) [3] [14]; High error rates in repetitive regions [3] | ~99% (with latest chemistry & basecallers) [13] | Longest reads; Real-time sequencing; Enables full-length 16S sequencing [11] [9] | Higher raw error rate requires specific tuning for repetitive regions [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

Illumina-Specific Issues

Q: What does a "Cycle 1 Error" on the MiSeq mean, and how can I resolve it?

This error indicates the instrument could not find sufficient signal to focus after the first sequencing cycle, often due to cluster generation issues [10].

- Potential Causes:

- Library Issues: Under-clustered or over-clustered libraries, poor library quality/quantity, or incompatible custom primers [10].

- Reagent Issues: Use of expired or improperly stored reagents, or an issue with the NaOH dilution (pH should be >12.5) [10].

- Instrument Issues: Problems with fluidics, temperature control, or the optical system [10].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Perform a system check on the instrument to verify fluidics and motion systems [10].

- Check reagent expiration dates and storage conditions [10].

- Verify library quality and quantity using Illumina-recommended methods (e.g., fluorometry) [10].

- Ensure custom primers are compatible and added to the correct cartridge wells [10].

- Repeat the run with a 20% PhiX spike-in as a positive control [10].

PacBio-Specific Issues

Q: What are the primary sources of error in PacBio sequencing, and how are they mitigated?

PacBio's primary strength is its low bias and random error profile. Errors are mitigated through the Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) protocol, which generates High-Fidelity (HiFi) reads.

- Error Profile: PacBio has been shown to be the "least biased" sequencing technology, particularly in coverage uniformity across regions with extreme GC content [12]. Its errors are relatively random and not systematically context-dependent like other platforms [12].

- Mitigation Strategy: The CCS protocol sequences the same DNA molecule multiple times in a circular manner. The multiple sub-reads are used to generate a highly accurate consensus sequence with a quality score (QV) of around Q30 (99.9% accuracy) [11] [13]. This process effectively corrects random errors inherent in single-molecule sequencing.

Oxford Nanopore-Specific Issues

Q: My Nanopore data shows strange repeat patterns in telomeric/homopolymer regions. What is happening?

This is a known artifact where specific repetitive sequences are systematically miscalled during basecalling [3].

- The Problem: In telomeric regions, the canonical

TTAGGGrepeat is often miscalled asTTAAAA, and its reverse complementCCCTAAis miscalled asCTTCTTorCCCTGG[3]. Deletions in homopolymer stretches and errors at Dcm methylation sites (e.g.,CCTGG,CCAGG) are also common [14]. - Root Cause: The basecalling errors occur due to a high degree of similarity between the ionic current profiles of the true telomeric repeats and the artifactual error repeats, making it difficult for the basecaller to distinguish them [3].

- Solutions:

- Re-basecall with Updated Models: Use the most recent high-accuracy basecaller (e.g., Guppy or Dorado in "SUP" or "HAC" mode) as basecalling models are continuously improved [3] [9].

- Bioinformatic Correction: Perform reference-free error correction using tools like Canu, which uses an overlap-layout-consensus approach to correct reads against each other [15].

- Hybrid Correction: For maximum accuracy, use short-read Illumina data to polish the Nanopore assembly or reads using a tool like Pilon [15].

Q: How can I improve the accuracy of my Nanopore 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing results?

- Wet-Lab: Use high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA. Gel-based size selection can help remove contaminants and degraded DNA [14].

- Sequencing: Use the latest flow cells (e.g., R10.4.1) which have a dual reader head, improving basecalli ng accuracy [13].

- Basecalling: Always use the highest accuracy basecalling model available (e.g., "SUP" mode in Guppy/Dorado), not the "fast" mode, as the model significantly impacts strand-specific recovery and accuracy [3] [9].

- Bioinformatics: Use specialized pipelines designed for Nanopore 16S data, such as Emu or the EPI2ME 16S workflow, which can help reduce false positives and negatives [9] [13].

Experimental Protocol for Cross-Platform 16S rRNA Sequencing Comparison

The following workflow is synthesized from comparative studies that evaluated Illumina, PacBio, and ONT for microbiome profiling [11] [9] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Use Case & Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) | Isolates microbial genomic DNA from complex samples like feces and soil. | Used for standardizing DNA extraction in rabbit gut microbiota studies [11]. Critical for consistency in cross-platform comparisons. |

| QIAseq 16S/ITS Region Panel (Qiagen) | Targeted amplification and library preparation for Illumina sequencing of hypervariable regions. | Used for preparing V3-V4 16S libraries for respiratory microbiome analysis on the Illumina NextSeq [9]. |

| SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 (PacBio) | Prepares DNA libraries for PacBio sequencing by ligating SMRTbell adapters to double-stranded DNA. | Essential for generating the circularized templates required for HiFi sequencing of the full-length 16S rRNA gene [13]. |

| 16S Barcoding Kit (Oxford Nanopore) | Provides primers and reagents for amplifying and barcoding the full-length 16S gene for multiplexed ONT sequencing. | Used with the MinION for real-time, full-length 16S profiling of respiratory samples [9]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Gut Microbiome Standard | A defined microbial community with known composition used as a positive control. | Extracted alongside experimental samples to control for technical variability and benchmark platform performance [13]. |

| PhiX Control Library (Illumina) | A well-characterized control library used for quality control, error rate estimation, and calibration of cluster generation. | Spiking in 20% PhiX is a recommended troubleshooting step for runs failing with Cycle 1 errors [10]. |

| Ralinepag | Ralinepag, CAS:1187856-49-0, MF:C23H26ClNO5, MW:431.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2BAct | 2BAct, CAS:2143542-28-1, MF:C19H16ClF3N4O3, MW:440.8072 | Chemical Reagent |

In microbial genomics, accurately distinguishing true biological signals from technical noise is paramount. "Noise" encompasses both wet-lab artifacts introduced during library preparation and sequencing, and in-silico bioinformatic errors during analysis [16]. These artifacts can severely obscure the true picture of microbial diversity and function, leading to flawed ecological interpretations and clinical decisions. This technical support center provides a foundational guide for identifying, troubleshooting, and mitigating these issues, enabling researchers to produce more reliable data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common sources of sequencing artifacts in microbial studies? The most common sources originate early in the workflow. During library preparation, DNA fragmentation (whether by sonication or enzymatic methods) can generate chimeric reads due to the mishybridization of inverted repeat or palindromic sequences in the genome, a mechanism described by the PDSM model [16]. Adapter contamination and over-amplification during PCR are also major culprits, the latter leading to high duplicate rates and skewed community representation [6].

2. How can I tell if my low microbial diversity results are real or caused by technical issues? A combination of quality metrics can alert you to potential problems. Consistently low library yields or a high percentage of reads failing to assemble into contigs can indicate issues with sample input quality or complexity [17] [6]. In targeted 16S rRNA sequencing, a sharp peak around 70-90 bp in your electropherogram is a clear sign of adapter-dimer contamination, which will artificially reduce your useful data and diversity estimates [6].

3. My positive control for bacterial transformation shows few or no transformants. What went wrong? This is a classic sign of suboptimal transformation efficiency. The root causes can include [18]:

- Competent Cell Issues: Cells may have been damaged by improper storage, freeze-thaw cycles, or not being kept on ice.

- DNA Quality: The transforming DNA could be contaminated with phenol, ethanol, or salts that inhibit the process.

- Protocol Error: The heat shock or electroporation parameters may not have been followed correctly for the specific cell type.

4. How does the choice of sequencing technology influence the perception of microbial diversity? Different technologies have distinct strengths and weaknesses. Short-read sequencing (e.g., Illumina) is cost-effective for profiling dominant community members but struggles to resolve complex genomic regions and closely related species due to its limited read length [19]. In contrast, long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio) provides higher taxonomic resolution by spanning multiple variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene or enabling the recovery of more complete metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), thus revealing a broader and more accurate diversity [17] [19].

5. Can environmental factors like literal noise affect microbial growth and function? Yes, emerging evidence suggests so. Studies exposing bacteria to audible sound waves (e.g., 80-98 dB) have shown significant effects, including promoted growth in E. coli, increased antibiotic resistance in soil bacteria, and enhanced biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus [20]. In mouse models, chronic noise stress altered the gut microbiome's functional potential, increasing pathways linked to oxidative stress and inflammation [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Library Yield in 16S Amplicon or Shotgun Sequencing

Symptoms:

- Final library concentration is far lower than expected.

- Electropherogram shows a high proportion of small fragments (<100 bp) or adapter dimers.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Degraded/Dirty DNA Input | Check DNA integrity on a gel. Assess 260/230 and 260/280 ratios. | Re-purify the sample using clean columns or beads. Ensure wash buffers are fresh [6]. |

| Inefficient Adapter Ligation | Review electropherogram for a dominant ~70-90 bp adapter-dimer peak. | Titrate the adapter-to-insert molar ratio. Ensure ligase buffer is fresh and the reaction is performed at the optimal temperature [6]. |

| Overly Aggressive Size Selection | Check if the post-cleanup recovery rate is unusually low. | Optimize bead-based cleanup ratios. Avoid over-drying the bead pellet, which leads to inefficient elution [6]. |

| PCR Amplification Issues | Assess for over-amplification (high duplication) or primer dimer formation. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles. Use a high-fidelity polymerase. For 16S, consider a two-step indexing protocol [6]. |

Problem 2: Chimeric Reads and False Positive Variants

Symptoms:

- Anomalously high number of low-frequency SNVs and indels during variant calling.

- Visualization in IGV shows misalignments (soft-clipping) at the 5' or 3' ends of reads.

Root Cause: This is often due to the PDSM (Pairing of Partial Single Strands derived from a similar Molecule) mechanism during library fragmentation [16]. Sonication and enzymatic fragmentation can create single-stranded DNA fragments with inverted repeat (IVS) or palindromic sequences (PS) that mishybridize, generating chimeric molecules.

Mitigation Strategy:

- Wet-Lab: For critical applications, compare sonication vs. enzymatic fragmentation results, as the number and type of artifacts can differ [16].

- Bioinformatic: Use tools like ArtifactsFinder [16] to generate a custom "blacklist" of artifact-prone genomic regions based on IVS and PS. Manually inspect soft-clipped reads in IGV to confirm artifacts.

Problem 3: Poor Recovery of Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) from Complex Soils

Symptoms:

- Despite deep sequencing, few high-quality MAGs are binned.

- Assembled contigs are short and fragmented.

Root Cause: Soil is an exceptionally complex environment with enormous microbial diversity and high microdiversity (strain-level variation), which challenges assembly and binning algorithms [17].

Solution:

- Sequencing Strategy: Employ deep long-read sequencing (e.g., >90 Gbp per sample with Nanopore) [17]. Long reads produce longer contigs, improving binning accuracy.

- Bioinformatic Workflow: Use advanced binning workflows like mmlong2, which employs ensemble and iterative binning by combining multiple binners and using differential coverage from multi-sample datasets to dramatically improve MAG recovery from complex samples [17].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the Impact of Audible Sound on Bacterial Growth

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the effects of anthropogenic noise on microorganisms [20].

1. Equipment and Reagents:

- Sound Chamber: An acoustically insulated box.

- Sound Generator: Signal generator (e.g., BK 3560C, B&K Instruments), power amplifier, and loudspeaker.

- Bacterial Strains: Pure cultures (e.g., E. coli, P. aeruginosa).

- Growth Media: Standard broth and agar plates (e.g., LB).

- Incubator: Standard microbiological incubator.

2. Procedure:

- Preparation: Inoculate a fresh bacterial culture and grow to mid-log phase.

- Treatment Setup:

- Experimental Group: Place cultured plates or liquid broth in the sound chamber.

- Generate Sound: Expose cultures to a defined sound wave profile. A typical protocol uses 90 dB SPL with frequencies of 1, 5, and 15 kHz, applied for 1-hour periods with 3-hour intervals over a 24-hour treatment period [20].

- Control Group: Maintain identical cultures in a separate chamber with background noise (<40 dB).

- Analysis:

- Growth Measurement: After exposure, perform serial dilutions and plate on agar to count Colony Forming Units (CFUs). Compare CFU counts between experimental and control groups.

- Phenotypic Assessment: For specific bacteria, assess changes in pigment production (e.g., prodigiosin in Serratia marcescens) or biofilm formation, as these can be influenced by sound [20].

Protocol 2: Comparing Short- and Long-Read Sequencing for River Biofilm Microbiomes

This protocol outlines the method for a direct comparison of sequencing technologies [19].

1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collection: Collect epilithic biofilms by scrubbing the surfaces of stones or macrophytes with a sterile toothbrush into sterile river water.

- Preservation: Preserve the biofilm suspension in a DNA preservation buffer (e.g., ammonium sulphate, sodium citrate, EDTA).

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA using a specialized kit for soil/faecal microbes (e.g., Zymo Research Quick-DNA Faecal/Soil Microbe Kit), including a mechanical disruption step (e.g., TissueLyser II) and Proteinase K incubation for optimal yield [19].

2. Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Short-Read (Illumina):

- Target: Amplify the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene.

- Primers: Use primers 515F and 806R with Illumina adapter sequences.

- Platform: Sequence on an Illumina NextSeq (2x 150 bp).

- Long-Read (PacBio):

- Target: Amplify the nearly full-length V1-V9 region of the 16S rRNA gene.

- Protocol: Use a Kinnex protocol from Novogene for library prep.

- Platform: Sequence on a PacBio Sequel II system.

3. Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process reads using standard pipelines (DADA2 for Illumina, PacBio's SMRT Link tools).

- Compare the two methods based on:

- Taxonomic Resolution: The ability to classify reads to the species level.

- Community Structure: Similarity in relative abundance profiles of major taxa.

- Diversity Metrics: Richness and evenness estimates.

Visualizing the PDSM Model for Artifact Formation

The following diagram illustrates the PDSM model, which explains how chimeric reads are formed during library fragmentation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quick-DNA Faecal/Soil Microbe Kit (Zymo Research) | Efficiently extracts high-quality DNA from complex, inhibitor-rich samples like soil and biofilms. | DNA extraction for river biofilm microbiome studies [19]. |

| DNA/RNA Shield (Zymo Research) | Protects nucleic acids from degradation immediately upon sample collection, preserving true microbial profiles. | Sample preservation during field collection of environmental samples [19]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5, NEB) | Reduces PCR errors during library amplification, minimizing one source of sequencing noise. | Amplicon generation for both Illumina and PacBio 16S libraries [19]. |

| Rapid MaxDNA Lib Prep Kit & 5x WGS Fragmentation Mix | Enables direct comparison of sonication vs. enzymatic fragmentation to identify protocol-specific artifacts. | Investigating the origin of chimeric reads and false positive variants [16]. |

| SOC Medium | A nutrient-rich recovery medium that increases transformation efficiency after heat shock or electroporation. | Outgrowth of competent cells after transformation to ensure maximum colony yield [18]. |

| ArtifactsFinder Algorithm | A bioinformatic tool that identifies and creates a blacklist of artifact-prone genomic regions based on inverted repeats and palindromic sequences. | Filtering false positive SNVs and indels from hybridization capture-based sequencing data [16]. |

| Acid-PEG3-PFP ester | Acid-PEG3-PFP ester, MF:C16H17F5O7, MW:416.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Acid-PEG9-NHS ester | Acid-PEG9-NHS ester, MF:C26H45NO15, MW:611.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Understanding Over-Splitting and Over-Merging

Q1: What are over-splitting and over-merging in the context of 16S rRNA analysis?

Over-splitting and over-merging are two opposing errors that occur when processing 16S rRNA sequencing data into taxonomic units.

- Over-splitting happens when a single biological sequence is incorrectly divided into multiple distinct variants (e.g., ASVs). This is a common challenge for denoising algorithms, which can mistake true biological variation (like intragenomic 16S copy variants) for sequencing errors, thereby artificially inflating diversity metrics [21] [22].

- Over-merging occurs when sequences from genetically distinct biological taxa are incorrectly clustered into a single unit (e.g., an OTU). This is more typical of clustering-based algorithms and leads to an underestimation of true microbial diversity [21].

Q2: What is the fundamental trade-off between ASV and OTU approaches?

The core trade-off lies between resolution and error reduction.

- Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs): Denoising methods like DADA2 aim for single-nucleotide resolution. They produce consistent, reproducible labels across studies but are prone to over-splitting, especially when multiple, non-identical copies of the 16S rRNA gene exist within a single genome [21] [22].

- Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs): Clustering methods like UPARSE group sequences based on a similarity threshold (often 97%). This effectively dampens sequencing noise but at the cost of lower resolution, often leading to over-merging of distinct but closely related taxa [21].

Benchmarking studies using complex mock communities have shown that ASV algorithms, led by DADA2, produce a consistent output but suffer from over-splitting. In contrast, OTU algorithms, led by UPARSE, achieve clusters with lower errors but with more over-merging [21].

Q3: How do sequencing errors and chimera formation contribute to these problems?

Sequencing errors and chimeras are key sources of data distortion that exacerbate both issues.

- Sequencing Errors: Next-generation sequencing platforms have inherent error rates. Without proper correction, these errors make sequences appear unique, promoting over-splitting and the false detection of a "rare biosphere" [23].

- Chimeras: These are spurious sequences formed during PCR when an incomplete DNA extension from one template acts as a primer on another, related template. One study found that 8% of raw sequence reads can be chimeric [23]. Chimeras appear as novel sequences and directly lead to over-splitting and spurious OTUs/ASVs if not identified and removed.

Q4: What practical steps can be taken to mitigate these issues?

A robust data processing pipeline is critical for error mitigation.

- Use Mock Communities: Include a mock community (a sample of known bacterial composition) in your sequencing run. This provides a ground truth to benchmark your bioinformatics pipeline's performance, allowing you to quantify and correct for over-splitting and over-merging in your specific dataset [24] [25].

- Implement Strict Quality Control: Employ tools like PyroNoise or quality filtering to correct erroneous base calls before clustering or denoising. One study reduced the overall error rate from 0.0060 to 0.0002 through rigorous quality filtering [23].

- Apply Robust Chimera Removal: Use dedicated chimera detection software like UCHIME. With quality filtering and chimera removal, the chimera rate can be reduced from 8% to about 1% [23].

- Sequence the Full-Length 16S Gene: When possible, use long-read sequencing (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) to target the full-length (~1500 bp) 16S gene. In-silico experiments demonstrate that sub-regions like V4 cannot achieve the taxonomic resolution of the full gene, which provides more sequence information to accurately distinguish between closely related taxa and true intragenomic variants [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting for Over-Splitting

Problem: Your alpha diversity metrics (e.g., number of observed species) are unexpectedly high, and you suspect many ASVs are artifactual.

Diagnosis:

- Analyze a Mock Community: Process a sequenced mock community sample with your pipeline. A high number of observed ASVs compared to the known number of strains indicates over-splitting [21] [25].

- Check for Intra-genomic Variants: If multiple ASVs are assigned to the same species, investigate if they could be valid intragenomic 16S rRNA gene copy variants. Cross-referencing with databases like SILVA can help [22].

Solutions:

- Adjust Denoising Parameters: Re-run your denoising algorithm (e.g., DADA2) with more stringent error model learning or adjust the abundance threshold for calling true sequences.

- Re-cluster ASVs: If the biological question allows, consider re-clustering your ASVs at a 99% identity threshold to collapse likely technical duplicates or true intragenomic variants without losing excessive resolution [22].

- Validate with Long-Reads: Use full-length 16S sequencing to confirm whether split ASVs truly originate from the same genomic context [22].

Guide 2: Diagnosing and Correcting for Over-Merging

Problem: Your analysis fails to distinguish between known, closely related species, suggesting a loss of taxonomic resolution.

Diagnosis:

- Benchmark with a Mock Community: Process a mock community that includes closely related species. If these species are clustered into a single OTU, it confirms over-merging [21].

- Evaluate Region Specificity: Be aware that the common "97% identity" cutoff for OTUs is not universally optimal. The resolution of different 16S variable regions (V4, V1-V3, etc.) varies by taxonomic group [21] [22].

Solutions:

- Switch to a Denoising Pipeline: Transition from an OTU-based workflow (e.g., UPARSE) to an ASV-based workflow (e.g., DADA2) to achieve higher, single-nucleotide resolution [21].

- Use a More Stringent Clustering Cutoff: If sticking with OTUs, try clustering at a 99% identity threshold. However, note that this may increase over-splitting and is highly region-dependent [22].

- Target an Informative Variable Region: If using short-read sequencing, select a variable region known to provide better resolution for your taxon of interest. For example, the V1-V2 region is better for Escherichia/Shigella, while V6-V9 is better for Clostridium and Staphylococcus [22].

Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Analysis of Clustering and Denoising Algorithms

This protocol is derived from a 2025 benchmarking study that objectively compared eight OTU and ASV algorithms using a complex mock community [21].

1. Mock Community & Data Collection:

- Mock Community: Utilize the most complex available mock community, such as the HC227 community comprising 227 bacterial strains from 197 different species [21] [25].

- Sequencing: Amplify the V3-V4 region using primers 5’-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3’ (forward) and 5’-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATC-3’ (reverse). Sequence on an Illumina MiSeq platform in a 2×300 bp paired-end run [21].

2. Data Preprocessing (Unified Steps):

- Primer Stripping: Remove primer sequences using a tool like

cutPrimers[21]. - Read Merging: Merge paired-end reads using

USEARCH fastq_mergepairs[21]. - Quality Filtering: Discard reads with ambiguous characters and enforce a maximum expected error rate (e.g.,

fastq_maxee_rate = 0.01) usingUSEARCH fastq_filter[21]. - Subsampling: Subsample all mock samples to an equal number of reads (e.g., 30,000) to standardize error levels [21].

3. Algorithm Application:

- Process the preprocessed data through a suite of algorithms, including:

- ASV/Denoising algorithms: DADA2, Deblur, MED, UNOISE3.

- OTU/Clustering algorithms: UPARSE, DGC (Distance-based Greedy Clustering), AN (Average Neighborhood), Opticlust [21].

4. Performance Evaluation:

- Error Rate: Calculate the number of erroneous reads per total reads.

- Over-splitting/Over-merging: Compare the number of output OTUs/ASVs to the known number of reference sequences. Assess how often reference sequences are incorrectly split or merged [21].

- Community Composition Accuracy: Measure how closely the inferred microbial composition matches the known composition of the mock community using alpha and beta diversity measures [21].

Protocol 2: Computational Correction of Extraction Bias

This protocol is based on a 2025 study that used mock communities to correct for DNA extraction bias, a major confounder in microbiome studies [24].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Mock Communities: Use commercially available whole-cell mock communities (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS) with even and staggered compositions. Include a "spike-in" community with species alien to your sample type (e.g., human microbiome) for normalization [24].

- Extraction Protocols: Extract DNA from multiple replicates of the mock communities using different extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp UCP Pathogen Mini Kit vs. ZymoBIOMICS DNA Microprep Kit), lysis conditions, and buffers [24].

2. Sequencing and Basic Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Sequence the V1–V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene alongside your environmental samples.

- Process the raw sequences through a standard pipeline (e.g., including quality filtering, denoising with DADA2, and chimera removal with UCHIME) to obtain an ASV table [24].

3. Bias Quantification and Correction:

- Quantify Bias: For the mock community samples, compare the observed ASV abundances to the expected abundances. The difference represents the protocol-specific extraction bias for each taxon [24].

- Link Bias to Morphology: Correlate the observed extraction bias for each species with its bacterial cell morphology (e.g., Gram-stain status, cell shape, size). The study found this bias to be predictable by morphology [24].

- Apply Correction: Develop a computational model that uses the morphological properties of the bacteria in your environmental samples to correct their observed abundances, based on the bias measured in the mock communities [24].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials for 16S rRNA Amplicon Studies

| Item | Function & Application | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Complex Mock Community | Serves as a gold-standard ground truth with known composition for benchmarking bioinformatics pipelines and quantifying technical biases like over-splitting and over-merging. | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standards (e.g., D6300, D6310); HC227 community (227 strains) [24] [25]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Different kits have varying lysis efficiencies and DNA recovery rates for different bacterial taxa, introducing extraction bias. Comparing kits is essential for protocol optimization. | QIAamp UCP Pathogen Mini Kit (Qiagen); ZymoBIOMICS DNA Microprep Kit (ZymoResearch) [24]. |

| Standardized Sequencing Platform | Provides a controlled and reproducible source of sequencing data and errors. The Illumina MiSeq platform is widely used for 16S amplicon sequencing. | Illumina MiSeq (2x300 bp for V3-V4 region) [21]. |

| Full-Length 16S Sequencing Platform | Enables high-resolution analysis by sequencing the entire ~1500 bp gene, improving species and strain-level discrimination and helping to resolve intragenomic variants. | PacBio Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS); Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) platforms [22]. |

| Bioinformatics Software Pipelines | Algorithms for processing raw sequences into OTUs or ASVs, each with different propensities for over-splitting or over-merging. | DADA2 (ASV, prone to over-splitting); UPARSE (OTU, prone to over-merging); UCHIME (chimera removal) [21] [23]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Pipeline for Evaluating Over-Splitting and Over-Merging. This workflow shows the critical steps for processing 16S rRNA data, highlighting the divergent paths of ASV and OTU methods and the essential role of a mock community in benchmarking their performance and identifying errors [21] [23].

Diagram 2: Core Problem: How Errors Lead to Over-Splitting and Over-Merging. This diagram illustrates the fundamental issue: sequencing artifacts can cause denoising methods to generate too many units (over-splitting), while clustering can collapse distinct biological sequences into too few units (over-merging) [21] [23].

Advanced Tools and Techniques: Modern Pipelines for Cleaner Microbial Data

Harnessing Long-Read Sequencing for Improved Genome Recovery from Complex Samples

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary long-read sequencing technologies available for complex microbial genome recovery? Two dominant long-read sequencing technologies are currently available: Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) HiFi sequencing and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) nanopore sequencing. PacBio HiFi sequencing generates highly accurate reads (99.9% accuracy) of 15,000-20,000 bases through circular consensus sequencing (CCS), where the DNA polymerase reads both strands of the same DNA molecule multiple times. ONT sequencing measures ionic current fluctuations as nucleic acids pass through biological nanopores, providing very long reads (up to 2.3 Mb reported) with current accuracy exceeding 99% [26] [27].

Q2: Why does my genome assembly from a complex sample remain fragmented despite using long-read sequencing? Fragmentation in genome assembly is strongly correlated with genomic repeats that are the same size or larger than your read length. In complex microbial communities, this is exacerbated by high species diversity and uneven abundance, where dominant species are more completely assembled than rare species. Assembly algorithms may also make false joins in repetitive regions or break assemblies at repeats, leading to gaps. Higher microdiversity within species populations can further reduce assembly completeness [28] [17].

Q3: What specific challenges does long-read sequencing present for transcriptomic analysis in microbial communities? Long-read RNA sequencing captures full-length transcripts but faces challenges in accurately distinguishing real biological molecules from technical artifacts. A significant challenge is identifying "transcript divergency"—rare, often sample-specific RNA molecules that diverge from the major transcriptional program. These include novel isoforms with alternative splice sites, intron retention events, and alternative initiation/termination sites. Without careful analysis, these can be misinterpreted as technological errors or lead to incorrect transcript models [29].

Q4: How can I improve the detection of structural variants in complex microbial genomes using long-read sequencing? Long-read technologies excel at detecting structural variants (SVs)—genomic alterations of 50 bp or more encompassing deletions, duplications, insertions, inversions, and translocations. To improve SV detection: (1) ensure sufficient read length to span repetitive regions where SVs often occur, (2) use specialized SV calling tools designed for long-read data such as cuteSV, DELLY, or pbsv, and (3) leverage the ability of long reads to simultaneously assess genomic and epigenomic changes within complex regions [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Genome Recovery from Complex Terrestrial Samples

Problem: Despite deep long-read sequencing, the number of high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) recovered from complex environmental samples (e.g., soil, sediment) remains low.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Table 1: Solutions for Improving MAG Recovery from Complex Samples

| Problem Root Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High microbial diversity with no dominant species [17] | Low contig N50 (<50 kbp); Many short contigs; Low proportion of reads assembling | Increase sequencing depth (>100 Gbp/sample); Use differential coverage binning across multiple samples; Implement iterative binning approaches |

| High microdiversity within species [17] | Elevated polymorphism rates in assemblies; fragmented genomes | Apply multicoverage binning strategies; Use ensemble binning with multiple algorithms; Normalize for sequencing effort across samples |

| Suboptimal DNA extraction [17] | Low sequencing yield; Presence of inhibitors | Optimize extraction protocols for high-molecular-weight DNA; Include purification steps to remove contaminants |

| Inadequate bioinformatic workflow [17] | Poor binning results even with good assembly metrics | Implement specialized workflows like mmlong2; Combine circular MAG extraction with iterative refinement |

Experimental Protocol for Enhanced MAG Recovery: The mmlong2 workflow provides a comprehensive methodology for recovering prokaryotic MAGs from extremely complex metagenomic datasets [17]:

- Metagenome Assembly: Perform assembly using long-read assemblers (e.g., hifiasm, hicanu, flye)

- Polishing: Improve base-level accuracy using consensus methods

- Eukaryotic Contig Removal: Filter out non-prokaryotic sequences

- Circular MAG Extraction: Identify and extract circular genomes as separate bins

- Differential Coverage Binning: Incorporate read mapping information from multi-sample datasets

- Ensemble Binning: Apply multiple binners to the same metagenome

- Iterative Binning: Repeat binning multiple times to recover additional MAGs

Issue 2: Inaccurate Basecalling Affecting Downstream Analyses

Problem: Errors in basecalling reduce the quality of genome assemblies and variant detection, particularly in repetitive regions.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Table 2: Basecalling Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Root Cause | Technology Affected | Solutions & Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate basecaller training for specific sample types [30] | Both ONT & PacBio | Use sample-specific training when possible; For plants or non-standard organisms, retrain models |

| Suboptimal basecaller version or settings [30] [27] | Primarily ONT | Use production basecallers (Guppy, Dorado) for stability; Development versions (Flappie, Bonito) for testing features |

| Insufficient consensus depth for PacBio [30] | PacBio | Ensure adequate passes (≥4 for Q20, ≥9 for Q30); Optimize library insert sizes for CCS |

| Translocation speed variations [30] | ONT | Monitor read quality over sequencing run; Optimize sample preparation for consistent speed |

Experimental Protocol for Optimal Basecalling:

- Basecaller Selection: For production work, use stable production basecallers (Guppy for ONT, CCS for PacBio)

- Model Training: For non-standard samples (e.g., high GC content, unusual methylation), consider custom training

- Quality Control: Assess read length distribution, base quality, and other metrics with tools like LongQC or NanoPack

- Error Profiling: Characterize error patterns (indels vs. mismatches) to inform downstream correction

- Consensus Generation: For PacBio, ensure sufficient subread coverage for high-accuracy CCS reads

Issue 3: Genome Assembly Gaps and Misassemblies

Problem: Even with long-read sequencing, genome assemblies contain gaps and misassemblies, particularly in repetitive regions.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Diagnostic Signs:

- Assembly breaks at repetitive elements

- Missing single-copy genes in otherwise complete assemblies

- Discrepancies between different assemblers for the same dataset

- Inconsistent gene annotations across similar strains

Solutions:

- Multi-Assembler Approach: Generate assemblies using different tools (hifiasm, verkko, hicanu, flye) and merge contigs [31]

- Gap Identification and Filling: Use single-copy genes as markers to identify missing sequences in chromosome-level assemblies

- Biological Validation: Employ PCR verification of problematic regions (e.g., rrn operons, integrative conjugative elements)

- Hybrid Sequencing: Combine long reads with complementary data (mate-pair libraries, optical mapping) for scaffolding

Experimental Protocol for Gap Filling: This four-phase method improves completeness of chromosome-level assemblies [31]:

- Preparation Phase: Perform BUSCO evaluations on both merged contigs and chromosome-level assembly; align contigs to chromosomes and to original reads

- Location Phase: Identify precise positions of missing single-copy genes using BUSCO results and alignment data

- Recall Phase: Recruit reads aligned to contigs containing missing genes and reassemble them

- Replacement Phase: Align newly assembled sequences to chromosome-level assembly and replace gaps

Issue 4: Distinguishing Real Novel Transcripts from Technical Artifacts

Problem: Long-read RNA sequencing identifies tens of thousands of novel transcripts, but distinguishing genuine biological molecules from technical artifacts is challenging.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Diagnostic Framework:

- Full-Splice-Match (FSM): Transcripts matching reference at all splice junctions - likely real

- Incomplete-Splice-Match (ISM): Transcripts lacking junctions at 5' or 3' ends - potentially degradation or real alternative sites

- Novel-in-Catalog (NIC): New combinations of known splice sites - likely real

- Novel-not-in-Catalog (NNC): Transcripts with novel donor/acceptor sites - requires validation

Solutions:

- Multi-Tool Analysis: Use complementary tools (Bambu, IsoQuant, FLAIR, Lyric) with different detection strategies

- Experimental Validation: Employ PCR verification for problematic or biologically important transcripts

- Orthogonal Data Integration: Incorporate supporting evidence from other omics data

- Expression Level Consideration: Recognize that many valid novel transcripts are lowly expressed and sample-specific

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Bioinformatics Tools for Long-Read Data Analysis

| Tool Category | Tool Name | Technology | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basecalling [27] | Dorado | ONT | Converts raw current signals to nucleotide sequences |

| CCS | PacBio | Generates highly accurate circular consensus reads | |

| Read QC [27] | LongQC | ONT/PacBio | Assesses read length distribution and base quality |

| NanoPack | ONT/PacBio | Provides visualization and QC metrics for long reads | |

| Assembly [31] | hifiasm | PacBio HiFi | Assembles accurate long reads into contigs |

| hicanu | ONT/PacBio | Hybrid assembler combining long and short reads | |

| flye | ONT/PacBio | Specialized for repetitive genomes | |

| Variant Calling [27] | Clair3 | ONT/PacBio | Calls single nucleotide variants and indels |

| cuteSV | ONT/PacBio | Detects structural variants from long reads | |

| Binning & MAG Recovery [17] | mmlong2 | ONT/PacBio | Recovers prokaryotic MAGs from complex metagenomes |

| Apinocaltamide | Apinocaltamide, CAS:1838651-58-3, MF:C22H18F3N5O, MW:425.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Adh-503 | Adh-503, CAS:2055362-74-6, MF:C27H28N2O5S2, MW:524.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Table 4: Experimental Reagents and Kits for Long-Read Sequencing

| Reagent/Kits | Purpose | Considerations for Complex Samples |

|---|---|---|

| High-Molecular-Weight DNA Extraction Kits | Obtain long, intact DNA fragments | Optimize for environmental samples with inhibitors; Minimize shearing |

| PCR-Free Library Prep Kits | Avoid amplification bias | Essential for methylation analysis; Preserves modification information |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | Full-length transcript amplification | Minimize reverse transcription errors; Select for full-length coverage |

| Size Selection Beads | Remove short fragments and adapter dimers | Optimize bead-to-sample ratios; Avoid losing high-molecular-weight DNA |

In the analysis of microbial amplicon sequencing data, distinguishing true biological signal from technical noise is a fundamental challenge. Sequencing artifacts, including substitution errors, indel errors, and chimeric sequences, can drastically inflate observed microbial diversity and compromise downstream analyses [21]. Denoising pipelines have been developed to address this issue by inferring the true, biological sequences present in a sample, resulting in Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or clustering into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) [32]. This technical support guide focuses on benchmarking four widely used tools—DADA2, Deblur, UNOISE3, and UPARSE—within the broader thesis of addressing and mitigating sequencing artifacts to ensure the reliability of microbial data research. The choice of pipeline can significantly influence biological interpretation, making it essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to understand their specific strengths, weaknesses, and optimal application scenarios.

The featured denoising and clustering pipelines employ distinct algorithmic strategies to reduce data noise. DADA2 and Deblur are ASV-based methods that use statistical models to correct sequencing errors, producing reproducible, single-nucleotide resolution output without the need for clustering [32] [33]. UNOISE3 is also a denoising algorithm that produces ASVs (often referred to as ZOTUs) by comparing sequence abundance and using a probabilistic model to assess error probabilities [21]. In contrast, UPARSE is a clustering-based method that groups sequences at a fixed similarity threshold (typically 97%) into OTUs, operating on the assumption that variations within this threshold likely represent sequencing errors from a single biological sequence [21] [32].

Independent benchmarking studies on mock communities and large-scale datasets have revealed critical performance differences. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and benchmarked performance of each tool.

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Performance of Denoising Pipelines

| Tool | Algorithm Type | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 | Denoising (ASV) | High sensitivity, excellent at discriminating single-nucleotide variants [33]. | Can suffer from over-splitting (generating multiple ASVs from one strain); high read loss if not optimized [21] [34]. | Highest sensitivity [32] | Lower than UNOISE3 and Deblur [32] |

| Deblur | Denoising (ASV) | Conservative output, fast processing. | Tends to eliminate low-abundance taxa, potentially removing rare biological signals [35]. | Balanced | High [32] |

| UNOISE3 | Denoising (ASV) | Best balance between resolution and specificity; effective error correction [32]. | Requires high-sequence quality; may under-detect some true variants. | High | Best balance, highest specificity [32] |

| UPARSE | Clustering (OTU) | Robust performance, lower computational demand, widely used. | Lower specificity than ASV methods; rigid clustering cutoff can merge distinct biological sequences [21] [32]. | Good | Lower than ASV-level pipelines [32] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: I am using DADA2, but a very high percentage of my raw reads are being filtered out. What could be the cause and how can I address this?

A: Excessive read loss in DADA2 is a common issue, often related to stringent default quality filtering parameters. This is particularly pronounced with fungal ITS data or when sequence quality is suboptimal [34] [33].

- Solution 1: Fine-tune quality filtering parameters. The default

--p-trunc-qparameter (Phred score) might be too strict. Try lowering this value (e.g., from 20 to 10 or 2) to retain more reads, but monitor the resulting error rates [34]. - Solution 2: Use single-end reads. If merging of paired-end reads is failing due to low overlap or variable amplicon lengths (common in ITS sequencing), consider analyzing only the forward reads (R1) to avoid merge-related losses [34] [33].

- Solution 3: Disable chimera removal in DADA2. Run the denoising step with

--p-chimera-method noneand perform chimera removal separately using a tool like VSEARCH to see if the internal chimera check is overly aggressive [34].

Q2: My denoised data shows a spurious correlation between sequencing depth and richness estimates. Why does this happen and how can it be fixed?

A: This is a known issue when samples are processed individually (sample-wise processing) in DADA2. The denoising algorithm's sensitivity is dependent on the number of reads available to learn the error model, leading to more ASVs being inferred from deeper-sequenced samples [36].

- Solution: Use a pooled processing approach. Process all samples together in a single DADA2 run. This allows the algorithm to learn a unified error model from the entire dataset, preventing richness estimates from becoming confounded by per-sample sequencing depth [36].

Q3: Should I choose an ASV-based (DADA2, Deblur, UNOISE3) or an OTU-based (UPARSE) method for my study?

A: The choice depends on your research goals and the required taxonomic resolution.

- Choose ASV-based methods when you need the highest possible resolution (e.g., for strain-level differentiation, tracking specific sequence variants over time, or when studying closely related species) [32] [33]. Among them, UNOISE3 often provides the best balance of specificity and sensitivity, while DADA2 offers the highest sensitivity at the cost of potentially more false positives [32].

- Choose OTU-based methods like UPARSE for broader, community-level analyses where 97% similarity is sufficient, and when computational efficiency and a long history of use are priorities. Be aware that this approach may lump distinct biological sequences together [21] [32].

Q4: My fungal (ITS) amplicon data has highly variable read lengths. How can I optimize my denoising pipeline for this?

A: The high length heterogeneity in ITS regions requires adjustments from standard 16S rRNA gene protocols.

- Solution 1: Adjust or disable trimming. Avoid length truncation (

--p-trunc-len 0in QIIME2) during the denoising step to prevent losing sequences from species with longer ITS regions [33]. - Solution 2: Consider single-end analysis. If paired-end merging fails for long, variable amplicons, using only high-quality forward reads can yield more reliable and comprehensive results than forced merging [33].

- Solution 3: Optimize taxonomic classification. For fungal data, using a BLAST-based algorithm against the UNITE+INSD or NCBI NT databases often achieves more reliable species-level assignment compared to the naive Bayesian classifier default in DADA2 [33].

Workflow for Benchmarking and Selection

The following diagram illustrates a logical pathway for selecting and validating a denoising pipeline, based on common research objectives and known tool performance.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To objectively evaluate the performance of these denoising tools, the use of a mock microbial community with a known composition is considered the gold standard.

Key Experiment: Benchmarking with a Mock Community

Objective: To assess the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of DADA2, Deblur, UNOISE3, and UPARSE by comparing their output to the ground truth of a mock community.

Materials:

- Mock Community: Commercially available genomic DNA from a defined set of microbial strains (e.g., HM-782D from BEI Resources) or a custom-created community [32] [33].

- Sequencing Data: 16S rRNA gene (e.g., V4 region) or ITS1 amplicon sequencing data generated from the mock community. Replicate sequencing runs are highly recommended.

Methodology:

- Wet-Lab Preparation: Amplify and sequence the target genomic region (e.g., 16S V4, ITS1) from the mock community DNA using your standard laboratory protocol [32].

- Bioinformatic Processing: Process the raw sequencing data (in FASTQ format) through each of the four denoising pipelines (DADA2, Deblur, UNOISE3, UPARSE) using standardized, default, or optimally customized parameters.

- Example DADA2 command (R code, using paired-end data):

- Key Customization: For fungal ITS data, disable length truncation in DADA2 (

truncLen=0) and consider single-end analysis [33].

- Data Analysis:

- Sensitivity: Calculate the proportion of expected strains or sequence variants in the mock community that were successfully recovered by each pipeline.

- Specificity: Calculate the proportion of reported ASVs/OTUs that correspond to true, expected sequences. Spurious ASVs/OTUs not in the mock community are false positives.

- Quantitative Accuracy: Compare the relative abundance of each recovered taxon to its known, expected proportion in the mock community.

- Error Rate: Measure the number of erroneous sequences (e.g., chimeras, point errors) introduced by each pipeline [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Benchmarking Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Brief Description | Example & Source |

|---|---|---|

| Mock Community DNA | Provides a ground truth with known composition for validating pipeline accuracy. | "Microbial Mock Community B (Even, Low concentration)", v5.1L (BEI Resources, HM-782D) [32]. |

| Silva Database | A curated database of ribosomal RNA sequences used for alignment and taxonomic assignment of 16S data. | SILVA SSU rRNA database (Release 132 or newer) [21]. |

| UNITE Database | A curated database specifically for the fungal ITS region, used for taxonomic classification. | UNITE ITS database [33]. |

| NCBI NT Database | A comprehensive nucleotide sequence database; can be used for BLAST-based taxonomic assignment, especially for fungi. | NCBI Nucleotide (NT) database [33]. |

| Positive Control Pathogen | Verified infected samples used to test a pipeline's ability to identify known, truly present microbes in a complex background. | Clinical samples with PCR-verified infections (e.g., H. pylori, SARS-CoV-2) [37]. |

The benchmarking of denoising tools reveals that there is no universally "best" pipeline; the optimal choice is contingent on the specific research context. DADA2 offers high sensitivity ideal for detecting subtle variations, UNOISE3 provides an excellent balance for general purpose use, UPARSE is a robust and efficient choice for OTU-based studies, and Deblur offers a fast and conservative ASV alternative.

Based on the collective evidence, the following best practices are recommended:

- Validate with a Mock Community: Whenever possible, include a mock community in your sequencing run to empirically determine which pipeline performs best for your specific wet-lab and sequencing protocols [32] [33].

- Prefer Pooled Processing: When using DADA2, process all samples together in a pooled analysis to avoid spurious correlations between sequencing depth and richness [36].

- Customize for Your Target Locus: Adjust parameters for non-16S data (e.g., ITS). This includes modifying quality filtering, read length truncation, and taxonomic classification databases [33].

- Consider Algorithm Consensus: For critical applications, applying multiple pipelines and focusing on the consensus findings can increase confidence in the results.

By understanding the strengths and limitations of each tool and applying these troubleshooting and benchmarking protocols, researchers can make informed decisions that significantly enhance the reliability and interpretability of their microbial amplicon sequencing data.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: The pipeline fails during the initial dependency installation. What should I do?

Issue: Users frequently encounter failures when running the mmlong2 workflow for the first time, during the automated installation of its bioinformatic tools and software dependencies.

Solution:

- Run a Test Instance First: Before processing your primary data, perform a test run with the provided small Nanopore or PacBio read datasets. This helps verify the installation in a controlled manner. You can download these datasets using the command:

zenodo_get -r 12168493[38]. - Avoid Concurrent Runs: During the initial setup, launch only a single instance of mmlong2. Concurrent runs can interfere with the automated dependency installation process, which typically takes approximately 25 minutes [38].

- Use the Singularity Container: By default, mmlong2 downloads and uses a pre-built Singularity container to ensure a consistent environment. If you encounter issues with this method, you can try using the

--conda_envs_onlyoption to utilize pre-defined Conda environments instead [38].

FAQ 2: My run is consuming excessive memory or failing on a shared compute cluster.

Issue: The computational resources required by mmlong2 can be substantial, especially for complex datasets, leading to failed jobs on systems with limited memory.

Solution:

- Choose the Appropriate Test Mode: mmlong2 offers different testrun profiles. For a less memory-intensive test that completes in approximately 35 minutes with a peak RAM usage of 20 GB, use the Nanopore mode with the

myloasmassembler [38]. - Plan for Large-Scale Analyses: Be aware that a full analysis in PacBio HiFi mode using the

metaMDBGassembler can require up to 120 GB of peak RAM and take around 2 hours for the provided test data [38]. - Leverage Process Control: Use the

-por--processesparameter to control the number of processes used for multi-threading, which can help manage resource consumption on shared systems. The default is 3 processes [38].

FAQ 3: The pipeline cannot find the necessary taxonomic databases.

Issue: Errors related to missing databases (e.g., GTDB) prevent the pipeline from completing taxonomy and annotation steps.

Solution:

- Proactive Database Installation: To acquire all necessary prokaryotic genome taxonomy and annotation databases, run the command

mmlong2 --install_databasesbefore starting your analysis [38]. - Use Pre-installed Databases: If you have already installed the databases in a specific location, you can direct the workflow to reuse them without re-downloading by using options like

--database_gtdb[38]. - Consult Manual Installation Guide: The project provides a guide for manual database installation if the automated process is not suitable for your system configuration [38].

FAQ 4: I have a custom assembly or want to use a specific assembler. How do I integrate this?

Issue: Users may wish to incorporate their own pre-generated assemblies or deviate from the default assembler (metaFlye).

Solution:

- Incorporate Custom Assemblies: Use the

--custom_assemblyoption to provide your own assembly file. You can also supply an optional assembly information file in metaFlye format using the--custom_assembly_infoparameter [38]. - Select an Alternative Assembler: The pipeline supports multiple state-of-the-art assemblers. You can activate them using the respective flags [38]:

--use_metamdbgto use metaMDBG.--use_myloasmto use myloasm.

FAQ 5: How can I optimize MAG recovery from highly complex samples like soil?

Issue: Recovery of high-quality MAGs from extremely complex environments like soil is a recognized challenge in metagenomics.

Solution:

- Utilize Advanced Binning Features: The mmlong2 workflow is specifically optimized for complex datasets. It employs several strategies that contribute to increased MAG recovery [17] [39]:

- Differential Coverage Binning: Incorporates read mapping information from multiple samples.

- Ensemble Binning: Applies multiple binning tools to the same metagenome.

- Iterative Binning: The metagenome is binned multiple times to maximize recovery. In a major study, iterative binning alone recovered an additional 3,349 MAGs (14.0% of the total) [17] [39].

- Provide Sufficient Sequencing Depth: Deep sequencing is critical. A recent study successfully recovered over 15,000 novel species-level MAGs from terrestrial samples by generating a median of 94.9 Gbp of long-read data per sample [17] [39].

Key Experimental Protocols and Data

Performance Metrics from a Large-Scale Terrestrial Study

A study leveraging mmlong2 sequenced 154 complex environmental samples (soils and sediments) to evaluate the pipeline's performance. The table below summarizes key sequencing and MAG recovery metrics from this research [17] [39].

Table 1: mmlong2 Performance on Complex Terrestrial Samples

| Metric | Median Value (Interquartile Range) | Total Across 154 Samples |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Data per Sample | 94.9 Gbp (56.3 - 133.1 Gbp) | 14.4 Tbp |

| Read N50 Length | 6.1 kbp (4.6 - 7.3 kbp) | - |

| Contig N50 Length | 79.8 kbp (45.8 - 110.1 kbp) | 295.7 Gbp |

| Reads Mapped to Assembly | 62.2% (53.1 - 69.8%) | - |

| HQ & MQ MAGs per Sample | 154 (89 - 204) | 23,843 MAGs |

| Dereplicated Species-Level MAGs | - | 15,640 MAGs |

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput MAG Recovery

- Sample Selection & Sequencing: 154 samples (125 soil, 28 sediment, 1 water) from 15 distinct habitats were selected from a larger collection of over 10,000 samples [17] [39].

- DNA Sequencing: Deep long-read Nanopore sequencing was performed, generating a median of ~95 Gbp per sample [17] [39].

- mmlong2 Workflow Execution:

- Assembly: Metagenome assembly was performed, resulting in long contigs (median N50 >79 kbp) [17] [39].

- Processing & Binning: The workflow included polishing, removal of eukaryotic contigs, extraction of circular MAGs, and advanced binning strategies (differential coverage, ensemble, and iterative binning) [17] [39].

- Quality Assessment: Recovered MAGs were classified as high-quality (HQ) or medium-quality (MQ) based on standard genome quality metrics [17] [39].

- Analysis: The resulting MAGs were dereplicated to form a species-level genome catalogue and analyzed for their contribution to microbial diversity [17] [39].

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the mmlong2 pipeline for recovering prokaryotic MAGs from long-read sequencing data [38] [17] [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for an mmlong2 Analysis

| Item | Function / Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nanopore or PacBio HiFi Reads | Primary long-read sequencing data input. | The pipeline supports both technologies via the --nanopore_reads or --pacbio_reads parameters [38]. |

| GTDB Database | Provides a standardized microbial taxonomy for genome classification. | Can be installed automatically or provided via --database_gtdb if pre-downloaded [38]. |

| Bakta Database | Used for rapid, standardized annotation of prokaryotic genomes. | A key database for the functional annotation step [38]. |

| Singularity Container | Pre-configured software environment to ensure reproducibility and simplify dependency management. | Downloaded automatically on the first run unless Conda environments are specified with --conda_envs_only [38]. |

| Differential Coverage Matrix | A CSV file linking additional read files (e.g., short-read IL, long-read NP/PB) to the samples. | Enables powerful co-assembly and binning across multiple samples, improving MAG quality and recovery [38]. |

| ADX71743 | ADX71743, MF:C17H19NO2, MW:269.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AF64394 | AF64394, MF:C21H20ClN5O, MW:393.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main advantages of using Meteor2 over other profiling tools like MetaPhlAn4 or HUMAnN3? Meteor2 provides an integrated solution for taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling (TFSP) within a single, unified platform. It demonstrates significantly improved sensitivity for detecting low-abundance species, with benchmarks showing at least a 45% improvement in species detection sensitivity in shallow-sequenced datasets compared to MetaPhlAn4. For functional profiling, it provides at least a 35% improvement in abundance estimation accuracy compared to HUMAnN3 [40].

Q2: My primary research involves mouse gut microbiota. Is Meteor2 suitable for this? Yes. Meteor2 currently supports 10 specific ecosystems, including the mouse gut. Its database leverages environment-specific microbial gene catalogues, making it highly optimized for such research. Benchmark tests on mouse gut microbiota simulations showed a 19.4% increase in tracked strain pairs compared to alternative methods [40].