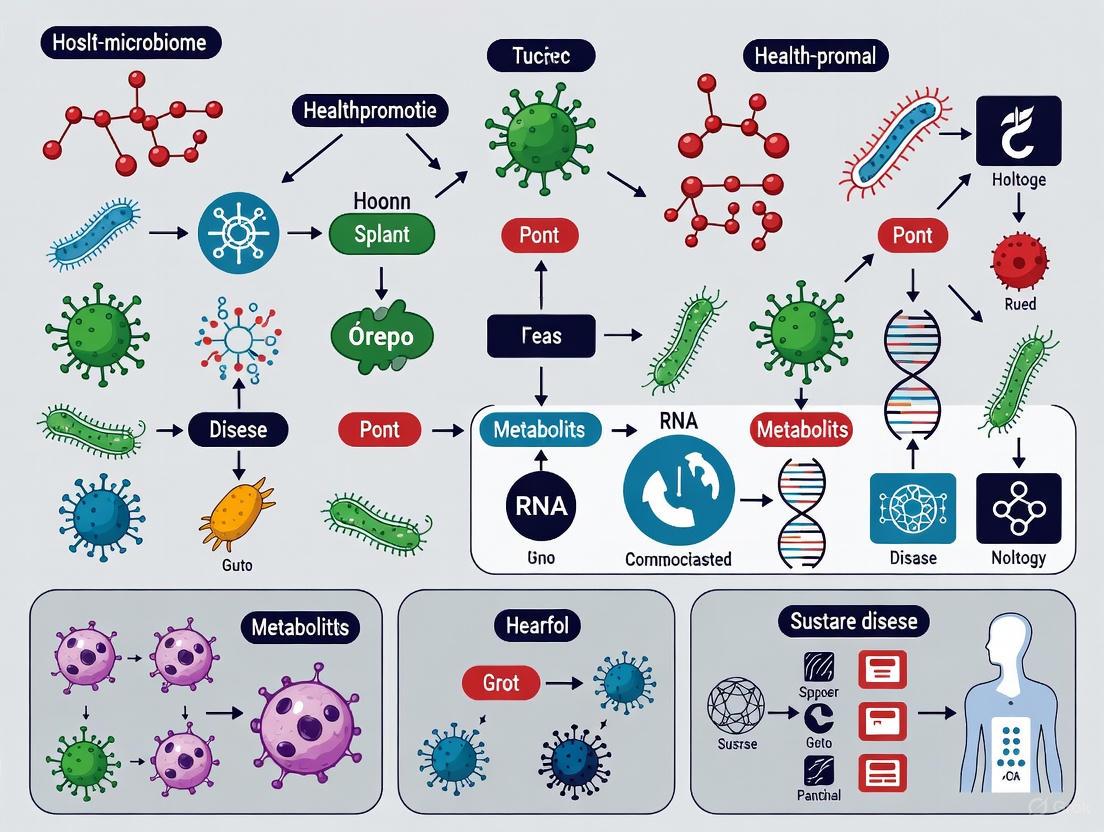

Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Applications of Host-Microbiome Interactions in Health and Disease

This article synthesizes current research on the intricate molecular dialogues between the host and its microbiome, exploring their profound impact on health and disease pathogenesis.

Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Applications of Host-Microbiome Interactions in Health and Disease

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the intricate molecular dialogues between the host and its microbiome, exploring their profound impact on health and disease pathogenesis. We delve into foundational mechanisms, including immune modulation via microbial metabolites and signaling pathways, and examine the causal role of dysbiosis in conditions from inflammatory bowel disease to preterm birth. The review critically assesses advanced methodological tools—from multi-omics to physiologically relevant tissue models and gnotobiotic systems—for investigating these interactions. Furthermore, we evaluate the translational potential of microbiome-based therapeutics, such as fecal microbiota transplantation and probiotics, while addressing the challenges of establishing causality and the imperative for standardized models to bridge the gap between basic research and clinical application for precision medicine.

The Molecular Language of Host-Microbiome Symbiosis and Dysbiosis

The human microbiome, once regarded as a passive passenger, is now recognized as a dynamic and essential determinant of human physiology, shaping immunity, metabolism, and host defense across the lifespan [1]. A healthy microbiome is not defined by a universal taxonomic blueprint but rather by the core functional capabilities that promote host homeostasis. These core functions—metabolic regulation, immune education, and colonization resistance—are maintained through complex host-microbe and microbe-microbe interactions [1] [2]. Advances in multi-omic technologies and analytical frameworks have shifted the focus from "who is there" to "what are they doing," revealing mechanistic insights into how microbial communities modulate host systems [1] [3]. This technical guide synthesizes current evidence on the defining functional attributes of a healthy microbiome, providing researchers and drug development professionals with structured data, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks for investigating host-microbiome interactions in health and disease.

Core Functional Pillars of a Healthy Microbiome

Metabolic Regulation and Nutrient Processing

A cornerstone of microbiome health is its metabolic capacity to transform dietary components into signaling molecules that regulate host physiology. The gut microbiota functions as a bioreactor, converting complex carbohydrates and other indigestible fibers into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) including acetate, propionate, and butyrate [1]. These metabolites serve as crucial energy sources for colonocytes and play fundamental roles in systemic metabolic regulation.

Table 1: Key Microbial Metabolites and Their Physiological Roles in Host Health

| Metabolite | Primary Producers | Physiological Functions | Association with Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp. | Primary energy source for colonocytes, enhances gut barrier function, anti-inflammatory properties [1] | Reduced in IBD, metabolic syndrome [4] |

| Propionate | Bacteroides spp., Akkermansia muciniphila | Gluconeogenesis precursor, regulates appetite, cholesterol synthesis inhibitor | Depleted in obesity, type 2 diabetes [4] |

| Acetate | Bifidobacterium spp., Lactobacillus spp. | Cross-feeds other bacteria, systemic metabolic regulator, modulates immune function | Altered in inflammatory conditions [1] |

Beyond SCFA production, microbial metabolism influences bile acid transformation, vitamin synthesis (B vitamins, vitamin K), and the bioavailability of phytonutrients. The integration of microbial metabolic functions with host pathways creates a symbiotic relationship where the host provides substrate and the microbiota provides metabolic outcomes that the host cannot achieve alone [1]. Metabolic dysfunction, characterized by shifts in these microbial metabolic pathways, has been implicated in conditions ranging from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) to metabolic syndrome and cancer [4].

Immunomodulation and Immune System Education

The microbiome serves as a foundational instructor for the developing and mature immune system, shaping both mucosal and systemic immunity through continuous dialogue with host immune cells [1]. From the neonatal period onward, microbial colonization is critical for proper immune maturation, with specific windows of opportunity where microbial exposure has lasting effects on immune function.

Microbial immunomodulation occurs through multiple mechanisms:

- Pattern Recognition Receptor Signaling: Microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) interact with host pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), regulating immune tone and inflammatory responses [1].

- T Cell Polarization: Specific microbial taxa influence the differentiation of naive T cells into regulatory (Treg), helper (Th1, Th2, Th17), or other effector subsets, balancing pro-inflammatory and tolerogenic responses [1].

- Cytokine and Chemokine Regulation: Microbial metabolites, including SCFAs, modulate the production of inflammatory mediators and homing molecules that recruit immune cells to mucosal sites [1].

The critical importance of early-life microbial exposure is demonstrated by studies showing that neonatal antibiotic exposure significantly impairs vaccine-induced antibody responses, an effect attributed to the depletion of beneficial Bifidobacterium species during critical windows of immune programming [1]. Similarly, breastfeeding facilitates the transfer of maternal microbes and human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) that selectively support the growth of immunoregulatory taxa like Bifidobacterium infantis, which promotes immune homeostasis by suppressing pro-inflammatory Th2 and Th17 cytokines [1].

Colonization Resistance and Pathogen Exclusion

A healthy microbiome provides protection against pathogenic organisms through the principle of colonization resistance—the ability of resident microbial communities to limit the expansion and invasion of pathogens. This function is mediated through multiple complementary mechanisms:

- Resource Competition: Commensals compete with pathogens for nutrients and physical binding sites on the mucosal surface [1].

- Production of Antimicrobial Compounds: Beneficial bacteria produce bacteriocins, defensins, and other antimicrobial substances that directly inhibit pathogens [4].

- Environmental Modification: Microbial metabolism alters local pH, oxygen tension, and other environmental conditions to create an unfavorable niche for pathogens [1].

- Immune System Priming: By maintaining appropriate immune system tone, a healthy microbiome ensures rapid pathogen clearance upon exposure [1].

The therapeutic implications of colonization resistance are exemplified by the success of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection, where restoration of a diverse microbial community displaces the pathogen [4]. However, research is now moving beyond traditional FMT toward precisely defined consortia of core probiotics that can reconstitute this protective function with reduced risk [4].

Methodological Framework for Microbiome Research

Diversity Metrics and Analytical Approaches

Robust assessment of microbiome health requires appropriate analytical tools that capture the ecological features of microbial communities. Alpha diversity metrics, which describe within-sample diversity, are commonly used but often misapplied without understanding their mathematical assumptions and biological interpretations [3]. These metrics can be categorized into four complementary classes, each capturing different aspects of microbial ecology:

Table 2: Categories and Applications of Alpha Diversity Metrics in Microbiome Research

| Metric Category | Key Metrics | Biological Interpretation | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | Chao1, ACE, Observed ASVs | Estimates total number of species/ASVs in a sample | Highly dependent on sequencing depth; Chao1 and ACE account for unobserved species [3] |

| Phylogenetic Diversity | Faith's PD | Incorporates evolutionary relationships between organisms | Depends on both number of features and singletons; requires phylogenetic tree [3] |

| Evenness/Dominance | Simpson, Berger-Parker, Gini | Measures distribution abundance across species | Berger-Parker has clear interpretation (proportion of most abundant taxon) [3] |

| Information Indices | Shannon, Pielou's | Combines richness and evenness into single value | Sensitive to both number of ASVs and their distribution [3] |

Recent guidelines recommend that microbiome analyses should include metrics from multiple categories to provide a comprehensive characterization of microbial communities [3]. For instance, while richness estimators quantify the number of taxa, dominance metrics like Berger-Parker reveal whether the community is dominated by a few taxa or exhibits balanced distribution—a feature particularly relevant in dysbiotic states where pathobionts may expand to dominate the community.

Experimental Workflows for Functional Characterization

Comprehensive functional analysis of the microbiome requires integrated multi-omic approaches that move beyond taxonomic profiling to capture the functional potential and activities of microbial communities.

Detailed Protocol for Integrated Multi-omic Analysis:

Sample Collection and Preservation:

- Collect fresh stool samples in DNA/RNA stabilizing buffer or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen

- For metabolomics, preserve samples at -80°C with cryoprotectants

- Record comprehensive metadata including host diet, medications, and clinical parameters [3]

Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Use mechanical lysis with bead beating to ensure disruption of tough bacterial cell walls

- Employ extraction kits validated for microbiome studies to minimize bias

- Include extraction controls to monitor for contamination [3]

Sequencing and Metabolomic Profiling:

- For 16S rRNA sequencing: Amplify V4 region using 515F/806R primers with dual-indexing approach

- For shotgun metagenomics: Sequence on Illumina platform to minimum depth of 10 million reads per sample

- For metabolomics: Use LC-MS/MS with reverse-phase chromatography for broad metabolite detection [4]

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process 16S data with DADA2 or DEBLUR for amplicon sequence variant (ASV) calling

- Analyze shotgun data with HUMAnN2 or MetaPhlAn for taxonomic and functional profiling

- Integrate datasets using multi-omics factor analysis (MOFA) or similar integration frameworks [3]

Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Science

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Microbiome Function

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | MoBio PowerSoil Kit, QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit | Standardized microbial DNA isolation | Bead beating step critical for Gram-positive bacteria [3] |

| 16S rRNA Primers | 515F/806R (Earth Microbiome Project) | Amplification of hypervariable regions for taxonomic profiling | Covers most bacterial and archaeal diversity; minimizes host amplification [3] |

| Standards for Metabolomics | Stable isotope-labeled SCFAs, bile acids | Quantification of microbial metabolites using LC-MS/MS | Enables absolute quantification; corrects for matrix effects [4] |

| Gnotobiotic Mouse Models | Germ-free C57BL/6, Humanized microbiota mice | In vivo functional validation of microbial communities | Essential for establishing causal relationships; requires specialized facilities [1] |

| Bacterial Cultivation Media | YCFA, Gifu Anaerobic Medium, M2GSC | Cultivation of fastidious anaerobic gut bacteria | Pre-reduced media with oxygen-free atmosphere essential for strict anaerobes [4] |

| Live Biotherapeutic Products | Defined consortia (e.g., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Akkermansia muciniphila) | Targeted microbiome modulation for functional restoration | Addresses limitations of traditional FMT; requires optimized cryopreservation [4] |

Translational Applications and Future Directions

From Microbial Functions to Targeted Therapies

The functional understanding of a healthy microbiome is driving the development of novel therapeutic strategies that target specific microbial activities rather than overall composition. Precision microbiome interventions are evolving beyond traditional probiotics and FMT toward defined consortia of core probiotics with specific functional attributes [4]. These live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) represent a new class of medicines designed to restore specific microbial functions rather than simply altering community composition.

Promising candidates include:

- Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: Associated with IBD maintenance through its impact on gut mucosal immunity and butyrate production [4].

- Akkermansia muciniphila: Linked to metabolic health through improvement of gut barrier function and insulin sensitivity [4].

- Lactobacillus reuteri: Recommended by World Gastroenterology Organisation for pediatric acute gastroenteritis and infant colic [4].

The future of microbiome-based therapeutics lies in matching specific functional deficiencies with targeted microbial interventions. This requires deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying microbial influence on host pathways and the development of robust diagnostic biomarkers to identify patients most likely to respond to specific microbiome-directed therapies [4].

Methodological Considerations for Robust Science

Microbiome research faces several methodological challenges that must be addressed to advance the field:

Standardization of Diversity Metrics: The field suffers from a proliferation of diversity metrics without clear biological interpretation. Guidelines now recommend reporting a comprehensive set of metrics including richness, phylogenetic diversity, entropy, dominance, and an estimate of unobserved microbes to capture different aspects of microbial communities [3].

Appropriate Use of Population Descriptors: Research identifying "race-based" differences in microbiome composition often mistakenly attributes these to biological rather than socio-environmental factors [2]. Race is a social construct, not a biological determinant, and differences between racial groups likely reflect variation in environmental exposures, diet, socioeconomic factors, and structural inequities [2]. Study designs should directly measure these specific variables rather than using race as a proxy.

Integration of Multi-omic Data: Combining metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, and metabolomic data remains challenging but is essential for connecting microbial community structure to function. Computational frameworks like the iProbiotics machine learning platform can facilitate rapid probiotic screening and identification of core functional members of the gut microbiota [4].

A healthy microbiome is defined by its functional capacity to maintain metabolic equilibrium, educate the immune system, and provide colonization resistance against pathogens. These core functions are conserved across different microbial community structures and represent the ultimate therapeutic targets for microbiome-based interventions. As research moves toward precision microbiome medicine, the focus will increasingly shift from taxonomic composition to functional capabilities, enabling development of targeted therapies that restore specific microbial functions in a personalized manner. The integration of advanced multi-omic technologies, standardized analytical frameworks, and appropriate consideration of socio-environmental factors will be essential for translating our understanding of microbiome function into effective interventions for human health.

The gut microbiome exerts a profound influence on host physiology and disease susceptibility through a complex network of molecular interactions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of three fundamental classes of microbial mediators: short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), tryptophan derivatives, and microbial antigens. We examine their production pathways, receptor interactions, signaling mechanisms, and functional impacts on host immunity, metabolism, and barrier function. Within the framework of host-microbiome interactions in health and disease, this review synthesizes current mechanistic understandings and presents standardized methodological approaches for investigating these key molecular players, offering researchers a comprehensive resource for advancing therapeutic development in microbiome-mediated conditions.

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts trillions of microorganisms that continuously communicate with host systems through molecular signaling. This dialogue is essential for maintaining homeostasis but, when disrupted, can contribute to disease pathogenesis across multiple organ systems [5] [6]. The molecular mediators of this cross-talk can be categorized into three primary classes: short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced from dietary fiber fermentation, tryptophan derivatives generated through host and microbial metabolism of essential amino acids, and microbial antigens that directly interface with host pattern recognition receptors. These mediators orchestrate a broad spectrum of host responses, from immune cell differentiation and epithelial barrier maintenance to neuroendocrine signaling and metabolic regulation [7] [8] [9]. Understanding their precise mechanisms of action provides crucial insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies for inflammatory, metabolic, autoimmune, and neoplastic diseases.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

Production and Basic Properties

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), primarily acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4), are produced by anaerobic bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers and resistant starch in the colon [7] [10]. Their production depends on gut microbiota composition, with key producers including Bacteroides spp., Blautia spp., Ruminococcus, and Bifidobacterium [7] [11]. The molar ratio of acetate, propionate, and butyrate in colonic contents is approximately 60–70:20–30:10–20, reflecting acetate as the most abundant SCFA [7] [10]. In peripheral blood, this ratio shifts dramatically to approximately 91:5:4 due to significant hepatic metabolism of propionate and butyrate, while acetate bypasses hepatic clearance [7].

More than 90% of SCFAs are absorbed from the intestinal lumen. Colonocytes utilize butyrate as their primary energy source, providing 60–70% of their energy requirements [7]. SCFAs not metabolized by colonocytes enter the portal circulation and are transported to the liver, where propionate and butyrate are almost entirely extracted [7]. The concentration of SCFAs in the colon is approximately 100 mM, while plasma concentrations range from 0.1 mM to 10 mM, with fecal concentrations providing a reliable indicator of colonic production [12].

Table 1: SCFA Concentrations Across Biological Compartments

| Compartment | Total SCFAs | Acetate | Propionate | Butyrate | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon Contents | ~100 mM | 60-70% | 20-30% | 10-20% | Molar ratio | [7] [12] |

| Peripheral Blood | Variable | ~91% | ~5% | ~4% | Molar ratio | [7] |

| Adult Feces | ~543.4 µmol/g | Predominant | Secondary | Tertiary | Concentration | [11] |

| Neonate Feces (1-month) | ~267.6 µmol/g | Predominant | Secondary | Tertiary | Increases with microbiome maturation | [11] |

| Preterm Neonate Feces | Significantly lower | ~75.6 µmol/g | ~17.0 µmol/g | ~0.5 µmol/g | At 1 month old | [11] |

Receptors and Signaling Pathways

SCFAs mediate their effects through multiple mechanisms: activation of specific G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs), and metabolic integration as energy substrates [7].

GPCR Activation: Three primary SCFA receptors have been characterized:

- GPR41 (FFAR3): Couples to Gαi/o subunits, shows preference for propionate > butyrate > acetate, and is expressed in intestine, lymph nodes, sympathetic ganglia, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells [7] [12].

- GPR43 (FFAR2): Couples to both Gαi/o and Gαq subunits, responds to acetate ≥ propionate ≥ butyrate, and is highly expressed on immune cells including neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes [7] [12].

- GPR109A (HCAR2): Couples to Gαi/o, is activated exclusively by butyrate, and is expressed on intestinal epithelial cells, adipocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells [7].

HDAC Inhibition: Butyrate and, to a lesser extent, propionate function as potent histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, particularly affecting HDAC1, HDAC3, and HDAC4 [7]. This inhibition increases histone acetylation, altering gene expression patterns in immune and epithelial cells, which contributes to anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effects.

Cellular Uptake: SCFAs enter cells via passive diffusion and active transport through monocarboxylate transporters (MCT1, MCT2, MCT4) and sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transporters (SMCT1 and SMCT2) [7] [10].

Figure 1: SCFA Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms of Action

Quantitative Analysis of SCFA Receptors

Table 2: SCFA Receptor Characteristics and Signaling Properties

| Receptor | Aliases | SCFA Affinity | Gα Subunit Coupling | Primary Tissue/Cellular Expression | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPR41 | FFAR3 | Propionate > Butyrate > Acetate | Gαi/o | Intestine, lymph nodes, sympathetic ganglia, peripheral blood mononuclear cells | Regulation of energy homeostasis, sympathetic nervous system activity, PYY secretion |

| GPR43 | FFAR2 | Acetate ≥ Propionate ≥ Butyrate | Gαi/o, Gαq | Immune cells (neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes), intestine, spleen | Neutrophil chemotaxis, inflammatory cytokine regulation, Treg differentiation, metabolic regulation |

| GPR109A | HCAR2 | Butyrate exclusively | Gαi/o | Colon, adipocytes, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils | Anti-inflammatory effects, induction of Treg cells, maintenance of epithelial barrier |

Experimental Protocols for SCFA Research

SCFA Quantification in Fecal Samples:

- Sample Collection: Collect fresh fecal samples in pre-weighed sterile tubes, immediately freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C.

- Extraction: Homogenize 50-100 mg of fecal material in ultrapure water (1:10 w/v). Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C.

- Derivatization: Transfer supernatant to GC vials and derivative with N-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-N-methyltrifluoroacetamide (MTBSTFA) at 70°C for 60 minutes.

- GC-MS Analysis: Separate derivatives using gas chromatography with a DB-5MS column and detect with mass spectrometry in selected ion monitoring mode. Use isotope-labeled internal standards for quantification.

SCFA Receptor Signaling Assay:

- Cell Transfection: Transfect HEK293 cells with plasmids encoding GPR41, GPR43, or GPR109A along with a CRE-luciferase or NFAT-luciferase reporter.

- Stimulation: Treat cells with SCFAs at varying concentrations (0.1 μM to 10 mM) for 6-8 hours.

- Detection: Measure luciferase activity using a luminometer. For calcium flux assays, use calcium-sensitive dyes in FLIPR systems.

HDAC Inhibition Assay:

- Nuclear Extract Preparation: Isolate nuclei from treated cells and extract nuclear proteins.

- Enzyme Activity: Incubate extracts with fluorogenic HDAC substrate (e.g., Ac-Lys(Ac)-AMC) in HDAC assay buffer for 1-2 hours at 37°C.

- Detection: Stop reaction with developer containing trichostatin A and nicotinamide, then measure fluorescence (excitation 360 nm, emission 460 nm).

Tryptophan Derivatives

Metabolic Pathways and Key Metabolites

Tryptophan, an essential amino acid obtained from dietary protein, is metabolized through three major pathways: the host kynurenine pathway, host serotonin pathway, and various microbial metabolic pathways [8] [9]. The kynurenine pathway, initiated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1) or tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), accounts for over 90% of tryptophan catabolism and generates multiple immunologically active metabolites [8] [13]. The serotonin pathway produces the neurotransmitter serotonin in enterochromaffin cells and central nervous system neurons [8]. Gut microbiota metabolize tryptophan into various indole derivatives through different enzymatic pathways [8] [9].

Table 3: Major Tryptophan Metabolites and Their Microbial Producers

| Metabolite Class | Specific Metabolites | Producing Bacteria | Key Enzymes | Reported Concentrations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoles | Indole | Escherichia coli, Clostridium spp., Bacteroides spp. | Tryptophanase (TnaA) | Feces: ~2.6 mM [9] |

| Indole Derivatives | IAA, IAld, ILA | Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Clostridium spp. | Aromatic amino acid aminotransferase, ILDH | Serum IAA: ~1.3 μM; Serum ILA: ~0.15 μM [9] |

| Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Ligands | IPA, IA | Clostridium sporogenes, Peptostreptococcus spp. | Phenyllactate dehydratase gene cluster (fldAIBC) | Serum IPA: ~1.0 μM (50 nM reported recently) [9] |

| Neuroactive Amines | Tryptamine | Ruminococcus gnavus, Clostridium spp. | Tryptophan decarboxylase (TrpD) | Urine (pregnant women): ~9 μM [9] |

Receptor Interactions and Signaling Mechanisms

Tryptophan metabolites signal through multiple receptors with diverse downstream effects:

Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AHR) Activation: Multiple microbial tryptophan catabolites including IAld, IAA, ILA, and IPA function as AHR ligands [9]. AHR activation regulates immune cell differentiation, enhances epithelial barrier function, and modulates xenobiotic metabolism. In intestinal immunity, AHR signaling promotes IL-22 production by type 3 innate lymphoid cells, supporting epithelial repair and antimicrobial defense [9].

GPCR Signaling: Several tryptophan metabolites activate specific GPCRs:

- Kynurenic acid activates GPR35, influencing energy expenditure and gastrointestinal motility [13].

- Tryptamine activates trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) and 5-HT4 receptors, modulating serotonin signaling and gut motility [8].

Neuroendocrine Modulation: Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) synthesized in enterochromaffin cells regulates gut motility, secretion, and platelet function [8]. Although peripheral serotonin cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, it influences the gut-brain axis via vagal afferent signaling.

Immune Regulation: Kynurenine pathway metabolites, particularly kynurenine itself, regulate T cell differentiation and function. High kynurenine levels promote regulatory T cell differentiation while suppressing effector T cell responses, creating an immunotolerant environment [8] [13].

Figure 2: Tryptophan Metabolic Pathways and Signaling Mechanisms

Experimental Protocols for Tryptophan Metabolite Research

Quantification of Tryptophan Metabolites:

- Sample Preparation: Extract metabolites from serum, feces, or cell culture supernatant using methanol precipitation (2:1 methanol:sample). Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Separate metabolites using reverse-phase chromatography (C18 column) with a water-acetonitrile gradient containing 0.1% formic acid. Detect using multiple reaction monitoring on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer.

- Quantification: Use stable isotope-labeled internal standards for each metabolite (e.g., d5-tryptophan, d4-kynurenine) for precise quantification.

AHR Activation Assay:

- Reporter Cell Line: Use HepG2 or other cell lines stably transfected with an AHR-responsive luciferase construct (e.g., XRE-luciferase).

- Treatment: Incubate cells with tryptophan metabolites or test compounds for 16-24 hours.

- Detection: Measure luciferase activity using a luminometer. Include known AHR ligands (e.g., FICZ) as positive controls and AHR antagonists (e.g., CH223191) as specificity controls.

IDO1 Activity Assay:

- Cell Culture: Stimulate human dendritic cells or macrophages with IFN-γ (100 ng/mL) for 24 hours to induce IDO1 expression.

- Incubation: Add tryptophan (100 μM) and test compounds for additional 24 hours.

- Measurement: Quantify kynurenine in supernatant by HPLC or spectrophotometrically (kynurenine absorbs at 360 nm). Calculate IDO1 activity as kynurenine production normalized to total protein.

Microbial Antigens

Classification and Immune Recognition

Microbial antigens represent a diverse category of structural components, secreted factors, and metabolic products that directly interface with the host immune system. They can be broadly classified into inflammatory commensals that stimulate effector immune responses and immunoregulatory commensals that promote tolerance [6]. These antigens engage pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and C-type lectin receptors on host immune cells [5].

Key microbial antigens include:

- Polysaccharide A (PSA) from Bacteroides fragilis: Signals through TLR2/TLR1 and Dectin-1 to promote anti-inflammatory responses and regulatory T cell development [5].

- Segmented Filamentous Bacteria (SFB) antigens: Adhere to intestinal epithelium and induce potent Th17 cell responses through antigen-specific mechanisms [6].

- Bacteroidetes β-hexosaminidase: Recognized by CD4 T cells as a conserved antigen driving their differentiation into CD4+CD8αα+ intraepithelial lymphocytes [14].

Mechanisms of Immune Modulation

Microbial antigens shape host immunity through several mechanisms:

T Cell Polarization: Specific commensal antigens direct T cell differentiation into distinct functional subsets. SFB antigens promote Th17 differentiation, while PSA from B. fragilis and Clostridium clusters promote regulatory T cell development [5] [6].

Innate Immune Training: Microbial antigens prime innate immune cells for enhanced or tempered responses to subsequent challenges. This trained immunity involves epigenetic reprogramming and metabolic alterations in myeloid cells [5].

Mucosal Barrier Reinforcement: Certain microbial antigens strengthen epithelial barrier function by enhancing tight junction expression and promoting mucus production. For instance, indole metabolites from microbial tryptophan metabolism upregulate tight junction proteins [5].

Compartmentalization: The immune system maintains compartmentalization of microbial antigens to the mucosal surface through multiple mechanisms including IgA coating, antimicrobial peptide production, and mucus layer maintenance [5].

Experimental Protocols for Microbial Antigen Research

Bacterial Antigen Preparation:

- Polysaccharide Isolation: Culture bacteria in appropriate medium, harvest supernatant, and precipitate polysaccharides with ethanol (3:1 v/v). Purify using ion-exchange chromatography and confirm structure by NMR.

- Cell Wall Fraction Preparation: Lyse bacteria by sonication, treat with DNase/RNase, and extract cell wall components using detergent-based methods.

- Protein Antigen Purification: Clone genes of interest into expression vectors, express in E. coli, and purify using affinity chromatography.

T Cell Polarization Assay:

- Antigen Presentation: Isolate naive CD4+ T cells from mouse spleen or human PBMCs using magnetic bead separation.

- Differentiation Culture: Co-culture naive T cells with bone marrow-derived dendritic cells pulsed with microbial antigens (1-10 μg/mL) in the presence of polarizing cytokines:

- Th17: TGF-β (2 ng/mL), IL-6 (20 ng/mL), anti-IFN-γ, anti-IL-4

- Treg: TGF-β (5 ng/mL), IL-2 (100 U/mL)

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: After 5 days, restimulate cells with PMA/ionomycin, stain for intracellular cytokines (IL-17A for Th17, FoxP3 for Treg) and analyze by flow cytometry.

Epithelial Barrier Function Assay:

- Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER): Culture epithelial cells (Caco-2 or T84) on transwell inserts until differentiated. Treat with microbial antigens and measure TEER daily using volt-ohm meter.

- Paracellular Permeability: Add FITC-dextran (4 kDa) to the apical compartment and measure flux to the basolateral compartment after 4 hours using a fluorometer.

- Immunofluorescence: Stain for tight junction proteins (ZO-1, occludin) and visualize by confocal microscopy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Microbial Mediators

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Key Applications | Supplier Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCFA Standards & Inhibitors | Sodium butyrate, Sodium propionate, Acetate, GPR41/43 antagonists (CATPB, GLPG0974) | Receptor signaling studies, HDAC inhibition assays, in vitro and in vivo functional studies | Sigma-Aldrich, Tocris, Cayman Chemical |

| Tryptophan Metabolites & Modulators | Kynurenine, Kynurenic acid, Indole-3-carbinol, FICZ, AHR antagonist CH223191, IDO1 inhibitor Epacadostat | AHR activation assays, T cell polarization studies, metabolic pathway analysis | Sigma-Aldrich, Enzo Life Sciences, MedChemExpress |

| Microbial Antigens | Bacteroides fragilis PSA, SFB antigens, LPS, Flagellin, Peptidoglycan | Immune cell activation studies, antigen-specific T cell responses, barrier function assays | InvivoGen, ATCC, laboratory isolation |

| Receptor Expression Constructs | GPR41/43/109A overexpression plasmids, AHR reporter constructs, TLR expression vectors | Receptor signaling studies, high-throughput compound screening, mechanism of action studies | cDNA ORF clones, Addgene |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-GPR41/43, Anti-AHR, Anti-FoxP3, Anti-IL-17A, Phospho-specific antibodies for signaling | Flow cytometry, Western blot, immunohistochemistry, ELISA development | BioLegend, Cell Signaling Technology, R&D Systems |

| Analytical Standards | 13C-labeled SCFAs, d5-Tryptophan, d4-Kynurenine, Isotope-labeled indole derivatives | Mass spectrometry quantification, internal standards for metabolomics | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Sigma-Aldrich |

| Regaloside E | Regaloside E, MF:C20H26O12, MW:458.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| fusarisetin A | fusarisetin A, MF:C22H31NO5, MW:389.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The molecular mediators produced by the gut microbiota—SCFAs, tryptophan derivatives, and microbial antigens—form a complex signaling network that fundamentally shapes host physiology and disease susceptibility. These mediators operate through defined receptors and signaling pathways to regulate immune responses, maintain barrier integrity, and modulate metabolic processes. Their integrated study requires sophisticated methodological approaches spanning molecular biology, immunology, and metabolomics. As research in this field advances, targeting these microbial mediators offers promising therapeutic opportunities for a wide range of conditions, including inflammatory diseases, metabolic disorders, cancer, and neurological conditions. The experimental frameworks and technical resources provided in this whitepaper offer researchers a foundation for advancing our understanding of host-microbiome interactions and developing novel microbiome-based therapeutics.

Barrier tissues—the gut, skin, and lungs—form the critical interface between the external environment and the internal body. They are not passive shields but dynamic ecosystems where host epithelial and immune cells engage in constant, complex communication with commensal microorganisms to maintain immune homeostasis. This equilibrium is orchestrated through a sophisticated network of epithelial sensing, immune cell regulation, and microbial metabolite signaling. Disruption of this delicate balance, termed dysbiosis, is a hallmark of numerous inflammatory, allergic, and infectious diseases. This whitepaper synthesizes the core mechanisms governing immune homeostasis at barrier tissues, detailing the tissue-specific cellular players, molecular pathways, and the pivotal role of the microbiome. Framed within the context of host-microbiome interactions, it provides a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, integrating current experimental models, key reagents, and quantitative data to inform future therapeutic innovation.

Barrier tissues, including the gastrointestinal tract, skin, and respiratory system, provide the first line of defense against environmental insults, pathogens, and toxins. Their primary function is to establish a physical barrier while simultaneously enabling selective absorption and sensing. The integrated ecosystem of a barrier tissue comprises the epithelial layer, a diverse population of resident and recruited immune cells, the commensal microbiota (bacteria, fungi, viruses), and their collective metabolite milieu [15] [16]. The immune system at these sites must therefore perform a delicate balancing act: mounting robust protective responses against genuine threats while maintaining tolerance to harmless antigens, food particles, and beneficial commensals. This state of controlled alertness is immune homeostasis.

The host-microbiome interaction is a cornerstone of this homeostatic regulation. The human body harbors a vast community of commensal microbes, with the gut microbiota alone being referred to as a "second genome" due to its profound influence on host physiology [17]. The microbiome is now understood to be a key environmental factor shaping the development, function, and tuning of the host immune system at barrier sites and beyond [18] [19]. This review will dissect the mechanisms of immunomodulation that sustain homeostasis, explore the consequences of their breakdown, and outline the experimental tools driving discovery in this field.

Core Mechanisms of Homeostasis at Barrier Tissues

The Epithelial Layer: More Than a Physical Barrier

The epithelium is the foundational cellular component of all barrier tissues. Far from being a simple wall, it is an active sensory and signaling organ equipped with an arsenal of pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) and mechanisms for direct microbial interaction.

- Innate Immune Sensing: Epithelial cells express a diverse array of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and cytosolic sensors (e.g., NLRs, inflammasomes) that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [20]. The localization of these sensors is critical. In the intestinal epithelium, certain TLRs are strategically positioned apically or basolaterally to distinguish between luminal commensals (requiring tolerance) and invasive pathogens (eliciting a strong defense) [20].

- Secretory Functions: Epithelial cells secrete a multitude of factors that shape the barrier environment. These include:

- Mucus: Goblet cells in the gut and airway produce mucus layers that trap microbes and particulates, preventing direct contact with the epithelium [15].

- Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs): Paneth cells in the intestinal crypts and keratinocytes in the skin produce defensins, cathelicidins, and other AMPs that directly inhibit or kill microorganisms, thereby controlling microbial colonization [15] [21].

- Cytokines and Alarmins: Epithelial-derived cytokines like TSLP, IL-25, and IL-33 alert the underlying immune system to barrier damage and help polarize subsequent immune responses [15] [22].

The Microbiome and Its Metabolites: Instructive Signals for Immunity

The commensal microbiota is essential for the proper development and regulation of the immune system. Germ-free (GF) mice exhibit significant immune deficiencies, including underdeveloped lymphoid structures and reduced immune cell populations, which can be partially rescued by microbial colonization [21] [18]. The microbiome exerts its immunomodulatory effects through two primary mechanisms: direct molecular interaction and metabolite production.

- Direct Molecular Interaction: Microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) from commensals engage host PRRs, providing tonic signals that maintain baseline immune readiness and promote homeostasis. For instance, commensal bacteria can promote the expansion of anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells (Tregs) via TLR2 signaling [18].

- Microbial Metabolites: The fermentation of dietary fiber by gut bacteria produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. SCFAs are potent immunomodulators with systemic effects [21]. They function by:

- Inhibiting histone deacetylases (HDACs), thereby influencing gene expression in immune cells and promoting Treg differentiation [18].

- Signaling through G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) like GPR41 and GPR43 on immune and epithelial cells, modulating inflammatory cytokine production and enhancing barrier integrity [21] [18].

Table 1: Key Immunomodulatory Metabolites from the Microbiome

| Metabolite | Primary Microbial Producers | Immunological Functions | Target Barrier Tissues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) | Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes | Promote Treg differentiation; inhibit HDAC; strengthen epithelial barrier; modulate macrophage function | Gut, Lung, Skin |

| Tryptophan derivatives | Various commensal bacteria | Activate Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR); promote IL-22 production; maintain barrier function | Gut, Skin |

| Secondary bile acids | Certain Clostridium species | Anti-inflammatory; regulate innate immune responses | Gut |

Tissue-Resident and Recruited Immune Cells: The Executors of Homeostasis

A specialized repertoire of immune cells resides in or patrols barrier tissues, executing the commands issued by the epithelium and the microbiome.

- Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILCs): These tissue-resident cells respond rapidly to cytokine signals from epithelia. ILC2s, for instance, are activated by IL-25 and IL-33 to produce type 2 cytokines, which are important for anti-helminth defense and tissue repair but also drive allergic pathology when dysregulated [15]. The microbiota shapes the composition and function of ILC populations [18].

- T Lymphocytes: Barrier tissues harbor diverse T cell populations. Tissue-resident memory T cells (Trm) provide localized protection against re-infection. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are critical for enforcing tolerance to commensals and food antigens, preventing inappropriate inflammation. Specific commensals, such as Clostridium species, are known to induce colonic Tregs [18].

- Macrophages and Dendritic Cells (DCs): These professional antigen-presenting cells sample the environment and dictate the nature of the T cell response. Intestinal macrophages and DCs are particularly adept at inducing Tregs in a steady state, a process influenced by retinoic acid and TGF-β [15]. They also transport gut-derived antigens to mesenteric lymph nodes, shaping systemic immune tolerance.

The following diagram illustrates the core cellular and molecular interactions that maintain homeostasis at a typical barrier tissue, such as the gut or lung.

Core Homeostatic Circuitry at Barrier Tissues

Tissue-Specific Immune Adaptations

While the core principles of barrier immunity are shared, the gut, skin, and lungs have evolved unique anatomical and immunological adaptations tailored to their distinct environmental challenges.

The Intestinal Barrier

The gut mucosa represents the body's largest barrier surface and hosts the densest microbial community. Its homeostasis relies on extreme specialization.

- Cellular Diversity: The intestinal epithelium is a single cell layer comprising absorptive enterocytes and several secretory lineages: Goblet cells (mucus production), Paneth cells (AMP secretion in the small intestine), Enteroendocrine cells (hormone secretion), and Tuft cells (sensing and initiating type 2 immunity) [15] [20].

- Compartmentalization: The mucus layer physically separates the bulk of the microbiota from the epithelium. In the colon, this layer is structured as an inner, sterile stratum and an outer, microbially colonized stratum [15].

- Immune Induction Sites: Structures like Peyer's patches and isolated lymphoid follicles serve as specialized sites for antigen sampling and the initiation of adaptive immune responses, including the generation of IgA-producing B cells, which is the most abundant antibody isotype in the gut and crucial for microbiota control [18].

The Skin Barrier

The skin epidermis is a multi-layered, keratinizing epithelium that must withstand physical, chemical, and biological trauma.

- Stratified Epithelium: Epidermal stem cells (EpdSCs) generate a stratified squamous epithelium, with terminally differentiated, enucleated corneocytes (squames) forming the outermost, waterproof barrier sealed by lipid bilayers [15].

- Resident Immune Sentinels: The epidermis is patrolled by Dendritic Epidermal T Cells (DETCs), a specialized population of resident γδ T cells, and Langerhans cells, tissue-resident macrophages. These cells work with EpdSCs to mount rapid responses upon barrier breach [15].

- Inflammatory Memory: Following an inflammatory experience, skin epithelial stem cells can retain an epigenetic memory, allowing for a more robust response to subsequent challenges. This "trained immunity" in parenchymal cells is a key adaptation [15].

The Pulmonary Barrier

The lungs present a unique challenge, requiring a thin epithelium for efficient gas exchange while being continuously exposed to inhaled antigens and microbes.

- Dynamic Microbiome: Unlike the gut, the healthy lung microbiome is low-biomass and transient, continually seeded by microaspiration from the upper respiratory tract and removed by mucociliary clearance and host immune mechanisms [21] [23]. The core healthy lung bacteriome includes genera like Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, and Veillonella [23].

- The Gut-Lung Axis: There is a well-established gut-lung axis, where gut-derived metabolites, particularly SCFAs, can modulate lung immunity. SCFAs can suppress allergic inflammation in the lung and enhance resistance to respiratory pathogens [21]. This explains how diet and gut dysbiosis can influence the susceptibility and severity of respiratory diseases like asthma [24] [21].

Table 2: Comparative Overview of Barrier Tissue Homeostasis

| Feature | Gut | Skin | Lung |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epithelial Structure | Single layer | Stratified squamous | Single layer, ciliated |

| Key Microbial Habitat | Dense, diverse community | Less dense, site-specific | Low biomass, dynamic |

| Dominant Commensals | Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes | Staphylococcus, Cutibacterium | Pseudomonas, Streptococcus |

| Specialized Immune Cells | Paneth cells, IELs | DETCs, Langerhans cells | Alveolar macrophages |

| Critical Secretions | Mucus, AMPs (defensins) | AMPs (defensins), sebum | Surfactant, mucus |

| Primary Communication Axis | Gut-Lung, Gut-Brain | Gut-Skin | Gut-Lung |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Investigating barrier immunity requires sophisticated models that recapitulate the complexity of host-microbe interactions. The following section details key experimental approaches and their associated protocols.

In Vivo and In Vitro Models

- Germ-Free (GF) and Gnotobiotic Mice: GF mice, raised in sterile isolators with no resident microbiota, are the gold standard for establishing the microbiome's causal role in immune phenotypes. These mice can be colonized with a single or defined consortium of microbes (gnotobiotic) to dissect specific host-microbe relationships [21] [18].

- Protocol Outline: 1) Maintain breeding colony in flexible film isolators. 2) Verify sterility via regular culturing and 16S rRNA PCR of feces. 3) For colonization experiments, transfer GF mice to a separate isolator and introduce a bacterial suspension via oral gavage. 4) Monitor microbial engraftment and host immune responses over time.

- 3D Human Mucosal Models: Advanced in vitro systems that mimic human disease pathology. For example, a 3D model of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) integrates epithelial cells, stromal fibroblasts, and immune elements within a scaffold, replicating barrier dysfunction, immune activation, and stromal remodeling [16].

- Protocol Outline: 1) Seed human intestinal epithelial cells onto a collagen scaffold with embedded fibroblasts. 2) Culture at an air-liquid interface to promote polarization and differentiation. 3) Introduce immune cells (e.g., peripheral blood mononuclear cells) into the system. 4) Stimulate with TNF-α or other cytokines to induce disease-like pathology. 5) Assess outcomes via transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER), cytokine ELISAs, and RNA sequencing.

- Antibiotic-Induced Dysbiosis: A common method to deplete the host microbiota and study its functional impact.

- Protocol Outline: 1) Administer a broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail (e.g., ampicillin, vancomycin, neomycin, metronidazole) in the drinking water of specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice for 2-4 weeks. 2) Confirm depletion of gut microbiota via 16S rRNA sequencing of fecal samples. 3) Challenge mice with an allergen (e.g., house dust mite for lung inflammation) or pathogen and compare immune responses to untreated controls [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table catalogues essential reagents and their applications in studying barrier tissue immunology.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Barrier Immunity Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Key Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD3ε / Anti-IL-10R mAb | T cell activation / IL-10 signaling blockade | Inducing T cell-driven colitis model in mice to study gut inflammation and tolerance. |

| Recombinant Cytokines (TSLP, IL-25, IL-33) | Activate ILC2s and type 2 immunity | Studying the role of epithelial alarmins in allergic asthma or atopic dermatitis models. |

| TLR Agonists (e.g., LPS, Poly(I:C)) | Activate specific PRR pathways (TLR4, TLR3) | Probing innate immune sensing mechanisms in primary epithelial cells or in vivo. |

| SCFAs (Butyrate, Propionate) | HDAC inhibitors; GPCR agonists | In vitro treatment of T cells to induce Treg differentiation; in vivo administration to suppress inflammation. |

| Clostridium spp. clusters | Induce colonic Tregs | Gnotobiotic colonization of GF mice to study mechanisms of peripheral tolerance induction. |

| FTY720 (Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator) | Sequesters lymphocytes in lymph nodes | Distinguishing between tissue-resident and recirculating immune cell populations in barrier tissues. |

| DSS (Dextran Sodium Sulfate) | Epithelial toxicant | Chemically inducing colitis in mice to model IBD and study wound repair mechanisms. |

| Fluorescently-labeled ZO-1/Occludin Antibodies | Tight junction proteins | Visualizing and quantifying epithelial barrier integrity via immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. |

| Neohesperidose | Neohesperidose, CAS:19949-48-5, MF:C12H22O10, MW:326.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Villocarine A | Villocarine A, MF:C22H26N2O3, MW:366.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The workflow for a typical experiment investigating the role of the gut-lung axis in allergic asthma is depicted below.

Gut-Lung Axis Experiment Workflow

The study of immunomodulation at barrier tissues has evolved from a focus on static defense to a dynamic understanding of a deeply integrated, multi-kingdom ecosystem. The mechanisms that maintain homeostasis—epithelial sensing, microbial metabolite signaling, and educated immune cell responses—are interconnected and finely tuned. Dysregulation at any point in this network can lead to a breakdown of tolerance and the emergence of disease, as seen in the atopic march (the progression from atopic dermatitis to food allergy and asthma) [24] and in chronic inflammatory conditions like IBD.

Future research and therapeutic development will be guided by several key frontiers:

- Spatio-Temporal Dynamics: Advanced imaging and single-cell multi-omics will reveal how immune responses are organized with micron-level precision within tissues and how they evolve over time.

- Personalized Microbiome Interventions: Moving beyond broad-spectrum probiotics, next-generation therapies will involve defined microbial consortia or microbiome-derived metabolites tailored to an individual's microbial and immune profile [18].

- Barrier-Strengthening Strategies: Therapies aimed not only at suppressing inflammation but actively restoring epithelial barrier function—through SCFAs, tight junction stabilizers, or stem cell therapies—hold great promise [16].

- Systemic Axis Targeting: Acknowledging the interconnectedness of barriers via axes like the gut-lung and gut-skin will enable novel treatments for remote inflammatory diseases by targeting the gut microbiome.

A deep understanding of the immunomodulatory mechanisms at barrier tissues is no longer a niche field but a central pillar of immunology, indispensable for developing the next generation of therapeutics for allergic, autoimmune, infectious, and neoplastic diseases.

The human body exists in a state of intricate symbiosis with trillions of microorganisms, collectively known as the microbiome, which contribute over 150 times more genetic information than the human genome itself [25]. This complex ecosystem, particularly within the gastrointestinal tract, functions as a metabolic organ essential for host homeostasis, contributing to nutrient extraction, immune system maturation, and protection against pathogens [25] [26]. In a state of health, the gut microbiota exhibits remarkable stability, resilience, and taxonomic diversity, dominated primarily by the phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, which account for approximately 90% of all gut microbial species [27] [28]. This symbiotic relationship represents a finely tuned equilibrium where microbial communities engage in beneficial cross-talk with host systems through the production of metabolites, immune modulation, and maintenance of epithelial barrier integrity.

The transition from this symbiotic state to dysbiosis—defined as an alteration in the ecosystem associated with pathology—represents a critical juncture in disease pathogenesis [29]. Dysbiosis manifests through multiple mechanisms: reduced microbial diversity, altered functional capacities, outgrowth of pathobionts, and diminished production of beneficial metabolites [27] [29]. While the precise definition of a "healthy" microbiome remains elusive due to considerable interindividual variation, the dysbiotic state has been consistently linked to a range of chronic inflammatory and metabolic conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), type 2 diabetes, and obesity [27] [30] [31]. This shift from mutualism to dysfunction involves a complex interplay between host genetics, environmental exposures, and microbial community dynamics that disrupts homeostatic mechanisms and propagates disease processes throughout the host system.

Mechanisms of Dysbiosis-Driven Pathogenesis

Metabolic Network Disruption in Host-Microbiome Crosstalk

Advanced metabolic modeling of host-microbiome interactions in IBD has revealed concomitant changes in metabolic activity across multiple data layers, highlighting profound disruptions in NAD, amino acid, one-carbon, and phospholipid metabolism [32]. During inflammatory flares, microbiome metabolic modeling demonstrates reduced within-community metabolic exchange, particularly affecting key metabolites including amylotriose, glucose, propionate, oxoglutarate, succinate, alanine, and aspartate [32]. These disruptions directly impact the host through multiple interconnected pathways:

- NAD Biosynthesis Impairment: Elevated host tryptophan catabolism during inflammation depletes circulating tryptophan pools, thereby impairing NAD biosynthesis—a cofactor fundamental to cellular energy production and redox homeostasis [32].

- Nitrogen Homeostasis Disruption: Reduced host transamination reactions disrupt nitrogen balance, subsequently impairing polyamine and glutathione metabolism essential for cellular protection and proliferation [32].

- One-Carbon Cycle Suppression: The suppressed one-carbon metabolism in patient tissues alters phospholipid profiles due to limited choline availability, affecting cellular membrane integrity and signaling [32].

Simultaneously, the microbiome exhibits complementary metabolic shifts in NAD, amino acid, and polyamine metabolism that exacerbate these host metabolic imbalances, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of metabolic dysfunction that perpetuates the inflammatory state [32].

Immunological Consequences of Microbial Dysbiosis

The gut microbiome plays an indispensable role in the education and regulation of the host immune system, with dysbiosis directly contributing to inappropriate immune activation in chronic inflammatory conditions. The intestinal epithelium serves as the primary interface for interactions between immune cells and gut microbes, with dendritic cells sampling microbial antigens to induce gut-resident Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) [28]. This process depends significantly on specific Clostridia species that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate, which enhances the integrity of intestinal epithelial cells and promotes anti-inflammatory responses [28].

Dysbiosis disrupts this delicate immunoregulatory balance through several mechanisms:

- Barrier Function Compromise: Dysbiosis is associated with altered physical epithelial barrier function, a thinner mucus layer, and impaired responses to endoplasmic reticulum stress, facilitating microbial translocation and immune activation [27].

- Pathobiont Expansion: Inflammatory conditions favor the expansion of pathobionts such as adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC), which can survive within macrophages and exert potent proinflammatory effects [29].

- SCFA Reduction: Diminished production of SCFAs, particularly butyrate and propionate, reduces their anti-inflammatory effects and impairs maintenance of colonic homeostasis [27].

The resultant immune dysregulation features inappropriate activation of both innate and adaptive immunity against gut antigens, with characteristic increases in proinflammatory cytokines and recruitment of inflammatory cells that perpetuate tissue damage and disease progression [27].

Table 1: Key Microbial Metabolites in Health and Disease

| Metabolite | Role in Symbiosis | Change in Dysbiosis | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain fatty acids (Butyrate, Propionate) | Primary energy source for colonocytes; Anti-inflammatory; Strengthen epithelial barrier | Reduced [27] | Impaired barrier function; Increased inflammation |

| Tryptophan metabolites | NAD biosynthesis; Immune regulation | Depleted circulating tryptophan [32] | Impaired NAD production; Disrupted cellular energy |

| Polyamines | Cell proliferation; Tissue repair | Disrupted metabolism [32] | Impaired mucosal healing |

| Bile acids | Lipid digestion; Antimicrobial effects | Altered composition; Reduced deconjugation [32] | Digestive dysfunction; Altered microbial composition |

Visceral Hypersensitivity and Neurological Implications

Beyond local intestinal inflammation, dysbiosis significantly impacts neurological function and pain perception through the gut-brain axis. Up to 30-50% of IBD patients in remission experience chronic abdominal pain despite the absence of active inflammation, suggesting altered sensory neuronal processing [33]. The gut microbiome influences visceral hypersensitivity through the production of neuroactive molecules including neurotransmitters (GABA, serotonin) and microbial metabolites such as SCFAs [33]. These molecules can directly interact with nociceptors to modulate hypersensitivity or indirectly influence pain signaling through immune stimulation [33].

Metabolomic approaches have identified approximately 5,000 low molecular weight molecules that mediate host-microbiome dynamics in pain perception [33]. The "sensitization" of nociceptors—characterized by a decreased threshold for stimulation and increased response magnitude—represents a key mechanism through which dysbiosis contributes to chronic pain states even in the absence of ongoing inflammation [33].

Methodological Approaches for Investigating Host-Microbiome Interactions

Metabolic Modeling and Multi-Omic Integration

To unravel the complex metabolic interactions between host and microbiome in inflammatory diseases, researchers have developed sophisticated modeling approaches that integrate multi-omic datasets:

- Constraint-Based Metabolic Modeling: This approach uses genome-scale metabolic models of the gut microbiome and host intestine to study host-microbiome metabolic cross-talk in the context of inflammation [32]. The modeling framework incorporates both coupling-based (MicrobiomeGS2) and agent-based (BacArena) approaches to predict flux distributions within bacterial communities [32].

- Context-Specific Metabolic Model (CSMM) Reconstruction: Using bulk RNA from colon biopsies and blood samples, researchers reconstruct tissue-specific metabolic models to calculate metabolic potential [32]. Reaction activity is estimated through multiple approaches: reaction-level expression activities (rxnExpr), reaction presence/absence in CSMM (PA), and flux variability analysis to determine upper and lower flux bounds (FVA.center, FVA.range) [32].

- Longitudinal Multi-Omic Profiling: Dense profiling of microbiome, transcriptome, and metabolome signatures from longitudinal IBD cohorts before and after drug therapy initiation allows identification of dynamic changes across biological layers [32].

Table 2: Experimental Models for Host-Microbiome Research

| Model System | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germ-free mice | Establishing causality in microbiome-disease relationships | Microbiome can be controllably manipulated; Absence of confounding microbes | Immune system develops abnormally without microbial exposure |

| Humanized microbiota mice | Studying human-relevant microbial communities | Human-derived microbiota in controlled environment | Limited translation due to host-specific differences |

| Organoids | Host-microbe interactions at epithelial interface | Human-derived; High-throughput capability | Lack full complexity of intestinal microenvironment |

| Cohort studies (Human) | Identifying disease-associated signatures | Direct human relevance; Assessment of real-world diversity | Correlation does not equal causation; Confounding factors |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Host-Microbiome Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | PacBio HiFi full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing [34] | Microbiome composition analysis | High-resolution taxonomic classification |

| Metagenomic shotgun sequencing [27] | Functional potential assessment | Identifies microbial genes and pathways | |

| Metabolomics Platforms | LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) [33] | Metabolite identification and quantification | Broad detection of polar and non-polar metabolites |

| GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) [33] | Volatile compound analysis | Ideal for SCFA measurement | |

| Animal Models | TNBS-induced colitis mouse model [34] | IBD pathophysiology studies | Chemically-induced intestinal inflammation |

| Germ-free mice [27] [26] | Causality establishment | Absence of native microbiome | |

| Computational Tools | MicrobiomeGS2 [32] | Metabolic modeling | Coupling-based approach emphasizing cooperation |

| BacArena [32] | Agent-based metabolic modeling | Individual-based simulation of microbial competition | |

| Bupleuroside XIII | Bupleuroside XIII, MF:C42H70O14, MW:799.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Kuwanon O | Kuwanon O | Kuwanon O is a natural resorcinol polyphenol from Morus australis. It is For Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications

Microbiome-Based Biomarkers and Diagnostic Approaches

The identification of specific microbial signatures associated with disease states enables the development of microbiome-based biomarkers for diagnostic and prognostic applications. In IBD, consistent alterations include reduced abundance of anti-inflammatory commensals such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and increased representation of Proteobacteria members including Escherichia coli [27]. Specific pathobionts such as adherent-invasive E. coli (AIEC) have been isolated from 21.7% of Crohn's disease chronic lesions compared to 6.2% of controls, suggesting their potential utility as diagnostic markers [29].

Functional biomarkers beyond taxonomic composition show particular promise for clinical application:

- Reduced Metabolic Exchanges: Inflammation-associated decreases in microbial cross-feeding of key metabolites including glucose, succinate, and aspartate may serve as functional indicators of dysbiosis [32].

- SCFA Production Deficits: Diminished production of butyrate and propionate represents a quantifiable functional deficiency in IBD microbiota [27].

- Microbial Diversity Metrics: Lower Shannon diversity indices have been associated with accelerated IBD onset (HR = 0.58 [0.49; 0.71]), highlighting the prognostic value of diversity measures [30].

Diagnosis of gut microbial dysbiosis typically involves comprehensive digestive stool analysis to determine bacterial types and quantities, though these analyses remain complex to perform and interpret [31]. Emerging approaches incorporate multi-parameter assessment including microbial composition, functional potential, and metabolic output to provide a more complete picture of the dysbiotic state.

Microbiome-Targeted Therapeutic Interventions

Current therapeutic approaches targeting the microbiome focus on restoring symbiotic relationships through multiple mechanisms:

- Dietary Interventions: High-quality nutrition significantly delays disease onset in both IBD (HR = 0.81 [0.66; 0.98]) and type 2 diabetes (HR = 0.45 [0.28; 0.72]) [30]. Dietary patterns that increase fiber intake support SCFA production and microbial diversity.

- Prebiotics and Probiotics: These interventions aim to directly modulate microbial community composition by introducing beneficial microorganisms or substrates that promote their growth [28].

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): Transfer of entire microbial communities from healthy donors has shown efficacy particularly for ulcerative colitis, though evidence for Crohn's disease remains less convincing [29].

- Novel Therapeutic Compounds: Plant-derived compounds such as galloyl-lawsoniaside A and uromyrtoside have demonstrated ability to restore microbial balance in colitis models by modulating key bacterial pathways including peptidoglycan biosynthesis [34].

- Pharmaceutical Modulation: Advanced metabolic models of host and microbe metabolism can predict dietary interventions that remodel the microbiome to restore metabolic homeostasis, suggesting novel therapeutic strategies for IBD [32].

The investigation of host-microbiome interactions has evolved from descriptive associations to mechanistic understandings of how microbial communities influence host physiology in health and disease. The transition from symbiosis to dysbiosis represents a critical pathway in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory and metabolic disorders, characterized by complex disruptions in metabolic cross-talk, immune regulation, and barrier function. Advanced multi-omic approaches and metabolic modeling have revealed the profound interconnectedness of host and microbial metabolic networks, demonstrating how inflammation induces complementary disruptions in both systems that perpetuate disease states.

Future research directions must focus on:

- Causality Establishment: While numerous associations between dysbiosis and disease are established, determining primary causal relationships remains challenging [29].

- Spatiotemporal Dynamics: Understanding how microbial communities vary along the gastrointestinal tract and over time will provide critical insights into disease mechanisms [33] [28].

- Personalized Interventions: Developing microbiome-based therapeutics tailored to individual microbial and host metabolic profiles represents the next frontier in precision medicine [32] [34].

- Standardization of Methodologies: Establishing consistent protocols for microbiome analysis and dysbiosis quantification will enhance reproducibility and clinical translation [29] [31].

As our understanding of host-microbiome interactions continues to deepen, the potential for targeting these relationships to prevent and treat chronic diseases offers promising avenues for therapeutic development. The integration of multi-omic data, advanced computational modeling, and targeted interventions positions microbiome research at the forefront of personalized medicine, with the potential to fundamentally reshape our approach to inflammatory and metabolic disorders.

The human body exists as a supraorganism, comprising human cells and a vast consortium of commensal microorganisms. Complex communication networks, known as microbial axes, facilitate crucial host-microbiome interactions that maintain systemic homeostasis. This whitepaper examines the core mechanisms and systemic implications of the gut-brain, gut-lung, and oral-systemic axes. We synthesize current understanding of how these axes influence pathophysiology across organ systems through neural, immune, endocrine, and metabolic pathways. Emerging therapeutic strategies targeting these axes, including precision microbiota interventions and barrier-strengthening approaches, are discussed alongside detailed experimental methodologies and reagent solutions for research applications.

The human microbiome represents a functional interface between host physiology and environmental factors. The gastrointestinal tract harbors the most dense and diverse microbial community, with the gut microbiota playing a crucial role in regulating host metabolism, immunity, and neurological function [18]. The conceptual framework of microbial axes has emerged as a fundamental paradigm for understanding how bidirectional communication between distant organ systems contributes to both health and disease.

The gut-brain axis, gut-lung axis, and oral-systemic axis represent distinct yet interconnected pathways through which microbial communities influence systemic physiology. These axes form dynamic, integrated networks involving neural signaling, immune modulation, metabolite transport, and microbial translocation. Disruption of homeostasis along these axes—through dysbiosis, barrier dysfunction, or immune dysregulation—has been implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous conditions, including neurodegenerative diseases, respiratory infections, metabolic disorders, and cancer [18] [35] [36].

This review integrates findings from microbiology, immunology, and neurobiology to elucidate the mechanistic basis of these systemic axes and their translational relevance for drug development.

The Gut-Brain Axis (GBA)

Core Components and Communication Pathways

The gut-brain axis constitutes a multichannel communication system linking emotional and cognitive centers of the brain with peripheral intestinal functions. Key components include the gut microbiota, intestinal mucosal barrier, enteric nervous system (ENS), vagus nerve, neuroendocrine signaling systems, and the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [36].

Communication occurs through several integrated pathways:

- Neural Pathways: The vagus nerve serves as a direct neural highway between gut and brainstem, transmitting sensory information about gut state and microbial metabolites to the central nervous system (CNS) [36].

- Immune Signaling: Gut microbes shape host immunity from development through adulthood. Microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) can activate Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in peripheral tissues and the brain, influencing neuroinflammation [18] [36].

- Endocrine Pathways: Enteroendocrine cells detect luminal contents and release neuroactive hormones and peptides that influence brain function [36].

- Metabolic Signaling: Microbiota-derived metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), tryptophan derivatives, and bile acids, circulate systemically and can cross the BBB to influence CNS physiology [18] [36].

Mechanisms of Interaction and Systemic Effects

Microbial metabolites function as key messengers along the GBA. SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate) produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber exert profound effects on both peripheral and central physiology. They function as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors and activate G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) to modulate inflammation, epithelial barrier integrity, and neurotransmitter synthesis [18].

The gut microbiota also directly produces or precursors a range of neuroactive molecules, including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin, dopamine, and acetylcholine, which can influence brain function and behavior [36]. Additionally, gut microbes regulate the metabolism of tryptophan, the primary precursor for serotonin synthesis, thereby influencing serotonin availability in the brain [18].

Immune activation represents another critical pathway. Gut microbiota composition regulates the differentiation of pro-inflammatory T helper 17 (Th17) cells versus anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells (Tregs). These immune cells can traffic to the CNS, influencing neuroinflammation in conditions like multiple sclerosis [36].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Research on the GBA employs sophisticated models to elucidate causal mechanisms:

- Germ-Free (GF) Animals: Mice raised without any microorganisms provide a controlled system to study microbiota contributions to neurodevelopment and behavior. Colonization of GF mice with specific microbiota reveals microbial influences on stress responses, neurotransmitter levels, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [18].

- Gnotobiotic Models: Animals colonized with defined microbial communities allow reductionist studies of specific host-microbe interactions. A landmark Drosophila melanogaster study with all 32 combinations of five core bacterial species revealed that microbial interactions shape host fitness through life history tradeoffs [37].

- Chemical and Genetic Manipulation: Antibiotic-induced microbiota depletion, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), and genetically engineered bacterial strains enable functional studies of microbial contributions to brain function and behavior.

Table 1: Key Microbial Metabolites in Gut-Brain Communication

| Metabolite | Primary Producers | Receptors/Targets | Neurological Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) | Bacteroides, Firmicutes | GPCRs (GPR41, GPR43, GPR109a), HDACs | Enhance blood-brain barrier integrity, regulate microglia homeostasis, influence neuroinflammation |

| Tryptophan metabolites | Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) | Regulate astrocyte activity, influence neuroinflammation, precursor for serotonin synthesis |

| Secondary bile acids | Bacteroides, Clostridium | Farnesoid X receptor (FXR), TGR5 | Modulate neuroinflammation, influence blood-brain barrier function |

| GABA | Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium | GABAâ‚ and GABAâ‚ receptors | Primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in CNS; microbial production may influence anxiety-related behaviors |

The Gut-Lung Axis

Mechanisms of Cross-Talk

The gut-lung axis represents a bidirectional communication network wherein gut microbiota influences respiratory immunity and function, while lung inflammation can reciprocally affect gut homeostasis. This axis operates primarily through immune cell trafficking and microbial metabolite distribution [38].

Key mechanisms include:

- Immune Cell Priming: Gut microbiota shapes the development and function of mucosal-associated immune tissues (MALT). Dendritic cells sample gut microbiota and migrate to mesenteric lymph nodes where they initiate immune responses; subsequently, primed immune cells travel to distant mucosal sites, including the lungs [38].

- Metabolite Signaling: SCFAs produced by gut microbiota enter circulation and influence lung immunity by regulating neutrophil and macrophage function, inhibiting HDACs, and promoting regulatory T-cell differentiation [38].

- Systemic Inflammation: Gut barrier dysfunction permits translocation of microbial products into circulation, potentially triggering low-grade systemic inflammation that compromises pulmonary function [38].

Implications for Respiratory Health

The gut microbiota plays a particularly crucial role in early-life immune programming that establishes lifelong respiratory health trajectories. Children with asthma demonstrate distinct gut microbiota compositions, with reduced abundance of Lachnospira, Veillonella, Faecalibacterium, and Rothia, alongside disordered SCFA profiles [38]. This dysbiosis before age three correlates with increased asthma risk, highlighting the developmental window of vulnerability.