Microbiological Method Verification vs Validation: A Strategic Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on navigating the critical distinctions between method verification and validation in microbiological analysis.

Microbiological Method Verification vs Validation: A Strategic Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on navigating the critical distinctions between method verification and validation in microbiological analysis. It clarifies foundational definitions, outlines step-by-step methodological protocols based on CLSI, ISO, and pharmacopoeial standards, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, and offers a comparative framework for strategic decision-making. By synthesizing current regulatory requirements and practical applications, this resource aims to ensure data integrity, regulatory compliance, and operational efficiency in biomedical and clinical research.

Verification vs Validation: Defining the Cornerstones of Microbiological Quality

In laboratory environments, particularly within pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and food safety, the demand for accurate and reliable testing is non-negotiable [1]. Two cornerstone processes ensure the fitness of analytical methods: method validation and method verification. While both aim to confirm that a method is suitable for its intended purpose, they fulfill distinct roles within the product and method lifecycle [1]. A clear understanding of these concepts is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to ensure regulatory compliance, data integrity, and ultimately, product safety and efficacy.

Method validation is the comprehensive process of proving that an analytical method is acceptable for its intended use, typically during development or when transferring methods between labs [1]. In contrast, method verification is the process whereby a laboratory confirms that a previously validated method performs as expected under its specific conditions [1]. This distinction is crucial in regulated environments where reproducibility and compliance are paramount. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 16140 series provides a standardized framework for these processes in microbiological testing, detailing protocols for both the initial validation of alternative methods and their subsequent verification in user laboratories [2].

Defining Method Validation

Core Concept and Purpose

Method validation is a documented process that proves an analytical method is reliable and acceptable for its intended purpose [1]. It is a comprehensive exercise involving rigorous testing and statistical evaluation to demonstrate that the method's performance characteristics meet predefined acceptance criteria. In the context of microbiology, this process is extensively detailed in standards such as ISO 16140-2, which provides the base protocol for the validation of alternative (proprietary) methods against a reference method [2]. The essential question validation answers is: "Is this method fundamentally fit-for-purpose?" [1].

When is Validation Required?

Validation is not a perpetual state; it is required in specific scenarios [1]:

- Development of a new analytical method.

- Significant modification of an existing method.

- Transfer of a method between laboratories or instruments.

- When required by regulatory bodies for novel methods or submissions.

Key Validation Parameters and Experimental Protocols

A full validation assesses multiple performance characteristics through defined experimental protocols. The table below summarizes the core parameters typically evaluated for both qualitative and quantitative microbiological methods, many of which are outlined in the ISO 16140 series [2].

Table 1: Key Parameters Assessed During Method Validation

| Parameter | Description | Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between a test result and the accepted reference value [1]. | Analysis of samples with known microbial concentrations (e.g., using certified reference materials) and comparison of results to the reference value. |

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between independent test results obtained under stipulated conditions [1]. | Repeatability: Multiple analyses of the same sample by the same analyst, same day. Intermediate Precision: Multiple analyses by different analysts, different days, different equipment. |

| Specificity | Ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components [1]. | Testing the method with samples containing likely interfering substances or non-target microorganisms to demonstrate no impact on detection. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest quantity of the analyte that can be detected [1]. | For qualitative methods, testing serial dilutions of low-level inocula to determine the point at which the target microorganism is consistently detected. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | Lowest quantity of the analyte that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy [1]. | For quantitative methods, determining the lowest level at which the count can be accurately enumerated, with defined precision and accuracy. |

| Linearity | Ability of the method to obtain test results proportional to the analyte concentration. | Testing a range of samples with different concentrations of the target microorganism to demonstrate a direct, proportional relationship. |

| Robustness | Capacity of the method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | Introducing minor changes in procedural parameters (e.g., incubation temperature, time, reagent lots) to evaluate the method's reliability. |

Defining Method Verification

Core Concept and Purpose

Method verification is the process of confirming that a previously validated method performs as expected in a specific laboratory setting [1]. It is typically employed when a laboratory adopts a standard method—such as a compendial method from the USP, EP, or AOAC—that has already undergone full validation. The process provides assurance that the method functions correctly with the laboratory's specific instruments, analysts, and environmental conditions. As per the ISO 16140-3 standard, verification involves two key stages: implementation verification and (food) item verification [2].

When is Verification Required?

Verification is a more targeted process than validation and is applicable in specific situations [1]:

- Implementing a compendial or previously validated method in a laboratory for the first time.

- Demonstrating competency in performing a standardized method for accreditation standards like ISO/IEC 17025.

- Confirming that a validated method works for specific sample matrices under local conditions.

Key Verification Parameters

Verification does not re-assess every validation parameter. Instead, it focuses on confirming critical performance characteristics to ensure the method works as intended in the user's laboratory. The ISO 16140-3 standard provides a structured protocol for this process [2].

Table 2: Typical Parameters Assessed During Method Verification

| Parameter | Verification Focus |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | Confirm published accuracy claims are achievable under the lab's specific conditions [1]. |

| Precision | Demonstrate that the laboratory can achieve the method's stated precision with its personnel and equipment [1]. |

| Specificity | Confirm the method correctly identifies and/or detects the target microorganism in the presence of normal sample flora. |

| LOD/LOQ | Verify that the published detection or quantification limits can be achieved in the lab [1]. |

Comparative Analysis: Validation vs. Verification

Understanding the differences between validation and verification is a strategic necessity for efficient laboratory operation and regulatory compliance.

Table 3: Summary Comparison: Method Validation vs. Method Verification

| Comparison Factor | Method Validation | Method Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Prove the method is fit-for-purpose [1]. | Confirm the lab can perform the validated method correctly [1]. |

| Context | Method development, transfer, or significant change [1]. | Adoption of an existing, standardized method [1]. |

| Scope | Comprehensive assessment of all performance parameters [1]. | Limited assessment of critical parameters under local conditions [1]. |

| Resource Intensity | High (time, cost, personnel) [1]. | Moderate to low [1]. |

| Regulatory Driver | Required for new method submissions [1]. | Required for using compendial methods [1]. |

| Result Applicability | Broad (method can be used universally) [1]. | Specific to the performing laboratory [1]. |

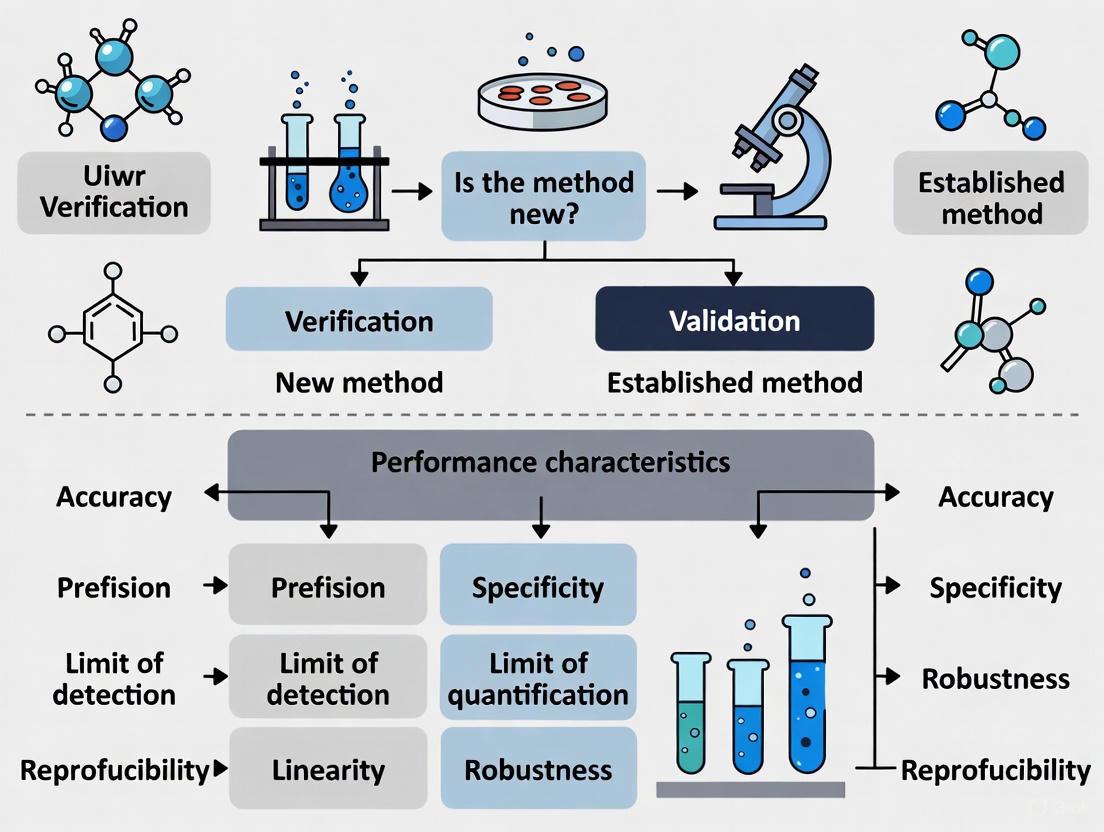

The relationship between validation and verification, and their place in the method lifecycle, can be visualized as a sequential workflow.

The Regulatory and Standards Framework: ISO 16140

The ISO 16140 series, "Microbiology of the food chain - Method validation," is the internationally recognized standard for the validation and verification of microbiological methods [2]. This series provides detailed protocols for different scenarios, guiding laboratories, test kit manufacturers, and regulatory authorities.

The series consists of multiple parts, each addressing a specific aspect of validation or verification [2]:

- ISO 16140-1: Vocabulary - Defines key terms.

- ISO 16140-2: Protocol for the validation of alternative (proprietary) methods against a reference method. This is the core validation standard.

- ISO 16140-3: Protocol for the verification of reference and validated alternative methods in a single laboratory.

- ISO 16140-4: Protocol for method validation in a single laboratory.

- ISO 16140-5: Protocol for factorial interlaboratory validation for non-proprietary methods.

- ISO 16140-6: Protocol for the validation of alternative methods for microbiological confirmation and typing procedures.

- ISO 16140-7: Protocol for the validation of identification methods of microorganisms.

The Pathway from Validation to Verification

The ISO 16140 framework clearly delineates the journey from a new method to its routine use in a laboratory. The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting the appropriate ISO standard based on the method's status and the laboratory's goal.

Essential Reagents and Materials for Method Assessment

The execution of robust validation and verification studies relies on well-characterized biological materials and reagents. These tools are fundamental for generating reliable and reproducible data.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Validation and Verification

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation/Verification |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Well-characterized materials used for determining method accuracy, precision, and linearity. They provide a known, traceable value for comparison [3]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Organisms | Well-characterized microbial strains with defined profiles. Used for growth promotion testing, monitoring test methodologies, and serving as positive controls [3]. |

| In-House Isolates | Microbial strains isolated from the laboratory's own environment or products. Critical for demonstrating that a method can detect relevant, "wild" contaminants [3]. |

| Stressed Microorganisms | Cultures that have been subjected to sub-lethal stress (e.g., heat, desiccation). Used to challenge the method and ensure it can detect microorganisms that may be injured in a process [4]. |

| Selective and Non-Selective Media | Culture media used for the reference method and for resuscitating microorganisms. Their performance is crucial for a fair method comparison [2]. |

In the highly regulated world of microbiological testing, a precise understanding of method validation and method verification is not merely academic—it is a practical necessity for ensuring product safety and regulatory compliance. Validation is the comprehensive process of establishing that a method is fundamentally fit-for-purpose, while verification is the targeted process of confirming that a laboratory can successfully implement that validated method.

The structured framework provided by standards such as the ISO 16140 series offers a clear pathway for laboratories to follow, from the initial validation of a new method to its routine verification and use. By adhering to these principles and utilizing appropriate reagents and controls, researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals can ensure the reliability, accuracy, and defensibility of their microbiological data, ultimately supporting the development and release of safe and effective products.

In the highly regulated fields of clinical diagnostics and pharmaceutical development, robust regulatory frameworks are essential for ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of products and services. For researchers and drug development professionals, navigating the complex landscape of these standards is particularly crucial when establishing the reliability of microbiological methods. The distinction between method verification (confirming that a method works as intended in a specific laboratory) and validation (providing objective evidence that a method meets the requirements for its intended use) forms the cornerstone of analytical quality. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of four key regulatory frameworks—CLIA, ICH, ISO 17025, and Pharmacopoeial requirements—focusing on their specific implications for microbiological method verification and validation practices within research and development settings.

Scope, Focus, and Legal Status

Various regulatory standards govern laboratory testing, each with distinct primary focuses, from technical competence to patient safety and product quality.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Laboratory and Quality Standards

| Standard | Primary Focus & Scope | Legal Status & Application | Governance Body |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLIA | Patient testing accuracy and reliability in clinical diagnostics [5]. | U.S. federal regulation; legally mandatory for clinical laboratories testing human specimens in the U.S. [6] [7]. | Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) [7]. |

| ISO/IEC 17025 | Technical competence and impartiality of testing and calibration labs; general requirements for all types of labs [8] [9]. | International standard; voluntary accreditation demonstrating operational competence [5] [9]. | International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) [9]. |

| ISO 15189 | Quality and competence specific to medical laboratories; focuses on the continuum of care and patient safety [6]. | International standard; voluntary accreditation that incorporates QMS and technical competence [5] [6]. | International Organization for Standardization (ISO) [6]. |

| ICH Guidelines | Pharmaceutical product quality, safety, and efficacy, including stability testing (Q1) and analytical validation (Q2) [10]. | International technical standards; adopted by regulatory authorities in different countries/regions (e.g., Europe, Japan, U.S.) [10]. | International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). |

| USP | Quality, purity, and identity of medicines and dietary supplements; specifies microbiological test methods and acceptance criteria [11]. | Recognized in U.S. law; compliance is often required by national regulations for marketing authorization [11]. | U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) [11]. |

Core Requirements and Relevance to Method Assurance

Table 2: Core Requirements and Application to Method Verification & Validation

| Standard | Core Technical & Quality Requirements | Relevance to Microbiological Method V&V |

|---|---|---|

| CLIA | Personnel qualifications, quality control, proficiency testing, inspection and accreditation [5] [7]. | Mandates that laboratories must verify the performance specifications of non-FDA approved methods (laboratory-developed tests) before reporting patient results. |

| ISO/IEC 17025 | Impartiality, confidentiality, personnel competence, method validation, measurement uncertainty, equipment calibration, and reporting [12] [9]. | Requires labs to validate non-standard and laboratory-developed methods, and verify their ability to correctly perform standard methods. |

| ISO 15189 | Quality management system, technical competence, pre-and post-examination processes, personnel, equipment, and assay validation [5] [6]. | Emphasizes the validation of examination procedures, including accuracy, precision, measurement uncertainty, and biological reference intervals. |

| ICH Q2(R2) | Validation of analytical procedures for pharmaceuticals, defining key validation characteristics like specificity, accuracy, and robustness [10]. | Provides the definitive framework for validating analytical methods (including microbiological assays) during pharmaceutical development and registration. |

| USP | Standardized test methods, acceptance criteria, and quality attributes for compendial articles [11]. | Methods like <61>, <62>, and <71> must be verified under actual conditions of use. Chapters like <1223> and <1227> provide guidance on validation of alternative and microbiological recovery methods [11]. |

Implementation and Workflow

Pathways to Compliance and Accreditation

The process for implementing these standards and achieving compliance or accreditation varies significantly. CLIA compliance is a legal requirement for clinical laboratories in the U.S., enforced through inspections and sanctions [7]. For voluntary standards like ISO 15189, laboratories typically follow a structured journey towards accreditation.

Figure 1: The ISO 15189 accreditation process involves multiple stages from initial commitment to ongoing surveillance over a three-year cycle [6].

Method Validation and Verification Workflow

A risk-based approach is central to modern quality systems like ISO/IEC 17025:2017 [12]. The decision to verify or validate a method depends on its source and standardization.

Figure 2: A risk-based decision workflow for method verification versus validation, crucial for regulatory compliance.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful method validation and verification require specific, high-quality reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiological V&V

| Reagent/Material | Critical Function in V&V | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Serves as the benchmark for calibrating equipment and validating methods; ensures metrological traceability [11]. | USP Endotoxin Reference Standard for LAL tests; Certified microbial cultures for identification assays [11]. |

| Competency Testing Kits | Verifies technician proficiency and method performance in routine practice; required for ongoing quality assurance [11]. | Enverify Viable Surface Sampling Kits for environmental monitoring competency [11]. |

| Characterized Microbial Strains | Used to establish accuracy, precision, and specificity of microbiological methods during validation [11]. | Instant Inoculator reference microorganisms for antimicrobial effectiveness testing (USP <51>) [11]. |

| Quality Control Cultures | Monures the ongoing performance and robustness of the method with each run or at defined intervals. | Using ATCC strains for daily QC of microbial enumeration tests (USP <61>) [11]. |

| Growth Media & Supplements | Supports microbial recovery and growth; formulation and performance are critical to method accuracy. | Validated soybean-casein digest medium for sterility testing (USP <71>); selective media for specified microorganisms (USP <62>) [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for Microbiological Method Validation

The following protocols outline core experiments for validating microbiological methods according to ICH, USP, and ISO principles.

Protocol for Specificity and Selectivity

1. Objective: To demonstrate that the method can accurately distinguish and detect the target microorganism(s) in the presence of other potentially interfering components, such as the product formulation, resident flora, or related species [11].

2. Materials:

- Test Strains: Pure cultures of target microorganism(s) (e.g., E. coli, S. aureus, C. albicans).

- Interfering Strains: Cultures of non-target microorganisms likely to be present.

- Sample Matrix: The product formulation without antimicrobial activity (or neutralized) and a placebo if available.

- Culture Media: Appropriate non-selective and selective media as required by the method.

3. Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Prepare separate inocula of each test and interfering strain to a defined density (e.g., 10^1-10^2 CFU/mL for enrichment tests, 10^4-10^5 CFU/mL for enumeration).

- Spiking Experiment: Spike the sample matrix and a negative control (e.g., saline or buffer) with the target and non-target strains, both individually and in combination.

- Testing and Analysis: Perform the test method on all spiked samples and controls. The method should detect the target organism in all relevant samples with no detection in the negative controls. For enumeration methods, recovery of the target from the product matrix should be statistically equivalent to recovery from the control.

Protocol for Accuracy and Recovery

1. Objective: To quantify the closeness of agreement between the value found by the test method and the known accepted reference value, often expressed as percent recovery [11].

2. Materials:

- Test Microorganism: A qualified working stock of a relevant microorganism.

- Sample Matrix: The product under test, neutralized if antimicrobial.

- Reference Material: Same as used for specificity.

3. Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a homogeneous sample of the product matrix. Spike the sample with a known, low level of the microorganism (e.g., 50-150% of the specification limit). Perform this in multiple replicates (n≥3).

- Control Preparation: Prepare an identical inoculum in a neutralizer or diluent without the product matrix to represent the "theoretical" 100% recovery.

- Testing and Analysis: Perform the test method on all spiked samples and controls. Calculate the percent recovery for each replicate: (Count from spiked sample / Count from control) × 100. The mean recovery and acceptance criteria should be established based on product type and method requirements (e.g., 70-130% for enumeration methods).

Protocol for Precision (Repeatability and Intermediate Precision)

1. Objective: To measure the degree of scatter between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under defined conditions. Repeatability is assessed under same conditions (same analyst, day, equipment), while intermediate precision includes variations (different days, analysts) [11].

2. Materials: As per the Accuracy protocol.

3. Methodology:

- Repeatability: One analyst prepares a single homogeneous sample spiked with a target microorganism at a specific level (e.g., near the specification limit). The analyst tests this sample in multiple replicates (n≥6) in one session using the same equipment and reagents.

- Intermediate Precision: A second analyst, and/or the first analyst on a different day, repeats the repeatability experiment using a newly prepared inoculum and reagents.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the mean, standard deviation (SD), and relative standard deviation (%RSD) for each set of results. The %RSD for the intermediate precision set should be comparable to or only slightly higher than the repeatability %RSD, demonstrating method robustness against minor operational variations.

Navigating the regulatory landscape of CLIA, ICH, ISO 17025, and pharmacopoeial requirements is a fundamental requirement for ensuring data integrity and patient safety in research and drug development. While these frameworks originate from different sectors—clinical diagnostics, international standardization, and pharmaceutical quality—they converge on a common principle: the critical importance of demonstrated analytical reliability. A thorough understanding of the specific requirements for method verification and validation under each standard enables scientists to design efficient, compliant studies. By integrating these principles into the laboratory's quality management system, organizations can effectively bridge the gap between research and regulation, ensuring that microbiological methods are not only scientifically sound but also meet the stringent demands of global regulatory bodies.

In the rigorous world of drug development and microbiological research, the processes of method validation and method verification are critical pillars of quality assurance and regulatory compliance. Though often confused, they serve distinct purposes. Verification confirms that a laboratory can correctly perform a pre-existing, validated method, answering the question, "Are we performing the test correctly?" [13] [14]. In contrast, Validation establishes, through extensive objective evidence, that a method is fit for its intended purpose, answering the question, "Does the test method work as intended?" [13] [15] [1].

This distinction is not merely semantic; it is foundational to data integrity, patient safety, and the successful approval of new therapeutics. This guide provides researchers and scientists with a structured framework for making this critical decision, complete with experimental protocols and data presentation standards.

Core Concepts and Decision Framework

Fundamental Definitions and Distinctions

The core difference lies in the purpose and scope of each activity:

- Method Validation is the process of proving that an analytical method is acceptable for its intended use [1]. It is a comprehensive exercise performed to demonstrate that the method's performance characteristics—such as accuracy, precision, and specificity—meet predefined criteria for a specific analyte and matrix [13]. Validation is typically required for new methods, laboratory-developed tests (LDTs), or when an existing method is significantly modified [15] [1].

- Method Verification is the process of confirming that a previously validated method performs as expected in a specific laboratory [13] [1]. It demonstrates that the laboratory's personnel, equipment, and environment can successfully replicate the method's validated performance characteristics. Verification is performed when a laboratory adopts an unmodified, FDA-cleared or compendial method (e.g., from USP or AOAC) for the first time [15] [14].

A useful analogy from systems and software engineering further clarifies this distinction: Verification checks "Are we building the product right?" (i.e., according to specifications), while Validation checks "Are we building the right product?" (i.e., fulfilling user needs) [16] [17] [18].

Decision Logic for Microbiological Methods

The following workflow provides a step-by-step guide for determining whether validation or verification is required for a given microbiological method in a drug development context.

When is Full Method Validation Required?

Method validation is a foundational activity in research and development. It is mandated in scenarios where the reliability of the method itself has not been previously established for its new context.

Key Application Scenarios

- Development of Novel Methods or Assays: When a new microbiological method is created from scratch, such as a novel PCR assay for a specific pathogen or a new biomarker detection method, full validation is required to establish all its performance characteristics [1].

- Laboratory-Developed Tests (LDTs): Any test that is developed and performed within a single laboratory is considered an LDT. Since these are not commercially distributed or reviewed by the FDA, they require intensive internal validation before they can be used for patient testing or critical research data [15].

- Significant Modification of an Existing Method: If a laboratory makes a change to an FDA-cleared or validated method that falls outside the manufacturer's acceptable parameters—such as using a different specimen type, changing sample dilutions, or altering critical test parameters like incubation times—the modified method must be validated [15].

- Method Transfer to a New Matrix or Category: When a validated method is applied to a new type of sample (matrix) that it was not originally validated for, a validation study (often called a "fitness-for-purpose" or matrix extension study) is required. For instance, using a method validated for raw meat to test cooked chicken requires validation to account for potential inhibitors or microbial load differences [13].

- Regulatory Submissions for New Products: Data submitted to regulatory bodies like the FDA or EMA in support of new drug applications (NDAs), investigational new drugs (INDs), or medical devices must be generated using fully validated methods [1].

Validation Experimental Protocol and Parameters

A full method validation requires a multi-parameter experimental approach. The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics, their definitions, and common experimental methodologies, particularly for qualitative/semi-quantitative microbiological assays.

Table 1: Core Parameters for Microbiological Method Validation

| Parameter | Definition | Experimental Protocol Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Agreement between the test result and the true value [14]. | Test a minimum of 20 positive and negative samples (e.g., clinical isolates, spiked samples) against a reference method. Calculate as: (Number of agreements / Total tests) × 100 [15]. |

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between independent test results under specified conditions (repeatability and reproducibility) [14]. | Test a minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative samples in triplicate over 5 days by 2 different operators. Calculate agreement as for accuracy [15]. |

| Specificity | Ability to measure the analyte accurately in the presence of interfering substances [14]. | Test samples with known interfering substances or non-target microorganisms to demonstrate no cross-reactivity. |

| Sensitivity | Proportion of true positives correctly identified [14]. | Calculated as: a / (a + b), where a = true positives, b = false negatives [14]. |

| Detection Limit (LOD) | Lowest amount of analyte that can be detected. | Test serial dilutions of the target microorganism to determine the lowest concentration that yields a positive result ≥95% of the time. |

| Reportable Range | Range of analyte values over which the method provides accurate results. | Verify using a minimum of 3 samples with values at the upper and lower limits of the expected range [15]. |

| Robustness | Capacity of the method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | Deliberately alter parameters like incubation temperature, time, or reagent lot to assess impact on results. |

When is Method Verification Sufficient?

Method verification is an efficiency-focused process that leverages prior validation work. It is sufficient in scenarios where the fundamental soundness of the method is already established, and the goal is to confirm its proper implementation in a new setting.

Key Application Scenarios

- Implementation of a Standard Compendial Method: When a laboratory adopts a well-established, published method from a recognized authority such as the US Pharmacopeia (USP), European Pharmacopoeia (EP), AOAC International, or a standard EPA method for the first time, verification is typically sufficient [1].

- Adoption of an Unmodified FDA-Cleared Test: Introducing a commercially available, FDA-cleared test kit (e.g., a new commercial cartridge-based molecular test) into the laboratory's test menu requires verification, not full validation, provided it is used exactly as specified by the manufacturer [15].

- Routine Re-confirmation in Quality Systems: While not a direct replacement for the initial verification, ongoing checks as part of a quality management system (e.g., after instrument servicing) are based on the principles of verification.

Verification Experimental Protocol and Parameters

Verification is a more targeted process than validation. The CLIA regulations require verification of several key performance characteristics for non-waived tests [15]. The scope is narrower, focusing on confirming that the lab can meet the manufacturer's or method's stated claims.

Table 2: Core Parameters for Microbiological Method Verification

| Parameter | Verification Protocol Summary | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Test a minimum of 20 positive and negative samples and compare results to a reference method or known values [15]. | Results must meet the manufacturer's stated claims or lab-defined criteria (e.g., ≥95% agreement) [15]. |

| Precision | Test a minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative samples in triplicate, typically over 3-5 days. If the system is not fully automated, include a second operator [15]. | The results should demonstrate acceptable variance as per manufacturer's claims or lab-defined criteria [15]. |

| Reportable Range | Verify the upper and lower limits by testing samples with values near these limits [15]. | The method should correctly identify samples within the reportable range. |

| Reference Range | Test a minimum of 20 samples representative of the laboratory's patient population to confirm the normal or expected result [15]. | The established reference range must be appropriate for the lab's specific patient population. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of robust validation and verification studies relies on high-quality, traceable materials. The following table details essential reagents and their functions in these processes.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Method V&V

| Reagent/Material | Function in V&V | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Serves as the primary standard for assigning a value to an analyte. Used for establishing accuracy and calibrating equipment. | Purity, stability, and metrological traceability to an international standard. |

| Quality Control (QC) Strains | Used to verify precision (repeatability/reproducibility) and monitor ongoing method performance. | Genetically defined, viability, purity, and known reactivity in the test system. |

| Characterized Clinical Isolates | Provide real-world samples for accuracy and specificity studies. Help confirm the method works with diverse strain variants. | Well-characterized identity and phenotype (e.g., antibiotic resistance profile). |

| Inhibitor/Interference Substances | Used in specificity and robustness studies to challenge the method and ensure it is not affected by common interferents (e.g., pectin, fats, blood) [13]. | High purity, prepared at clinically relevant concentrations. |

| Molecular Grade Water | Serves as a negative control and a diluent for preparing samples and standards. | Confirmed to be nuclease-free and sterile to prevent false results. |

| Palmitoleyl palmitate | Palmitoleyl palmitate, MF:C32H62O2, MW:478.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 9Z,12Z,15Z-octadecatrienoyl-CoA | 9Z,12Z,15Z-octadecatrienoyl-CoA, MF:C39H64N7O17P3S, MW:1028.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the highly regulated and scientifically rigorous field of drug development and microbiology, understanding the distinction between method validation and verification is not optional—it is essential. The choice between them hinges on a simple but critical question: Are you establishing that a method works at all, or confirming that it works in your hands?

To ensure compliance, data integrity, and patient safety, scientists must adhere to the following principle: Validation is required for novel, modified, or laboratory-developed methods, while Verification is sufficient for implementing standard, unmodified methods. By applying the decision framework, experimental protocols, and reagent standards outlined in this guide, researchers can navigate these requirements with confidence, ensuring their methods are both scientifically sound and regulatorily compliant.

Standardizing Concepts like Method Transfer and Suitability Testing

In the highly regulated pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical industry, the precision of analytical terminology is not merely academic—it is a fundamental requirement for ensuring product quality, patient safety, and regulatory compliance. Concepts such as method validation, method verification, method transfer, and method suitability testing form the backbone of analytical quality control. However, inconsistent application of these terms can lead to significant compliance risks, operational inefficiencies, and miscommunication during regulatory inspections. This guide provides a standardized framework for these core concepts, specifically contextualized within microbiological quality control, to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the clarity needed to navigate this complex landscape. A foundational understanding begins with distinguishing between the two most frequently contrasted processes: method validation and method verification.

Core Terminology: Validation, Verification, and Suitability

Method Validation vs. Method Verification

Method Validation is the comprehensive, documented process of establishing through laboratory studies that an analytical method's performance characteristics are suitable for its intended purpose [19] [20]. It provides proof that a newly developed method is reliable, accurate, and robust for a specific application.

Method Verification, in contrast, is the documented evidence that a laboratory can competently execute a previously validated method (e.g., a compendial method from USP, Ph. Eur., or JP) under its specific conditions [1] [19]. It confirms that the method performs as expected for a specified product in a given laboratory, without repeating the entire validation exercise.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Method Validation and Method Verification

| Comparison Factor | Method Validation | Method Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | To prove a method is fit-for-purpose [20] | To confirm a lab can perform a pre-validated method [19] |

| Typical Context | Newly developed in-house methods; significant modifications [19] | Adoption of compendial (USP, Ph. Eur.) or transferred methods [21] [19] |

| Scope | Full assessment of all relevant performance characteristics [20] | Limited assessment of critical parameters (e.g., precision, accuracy) [1] [15] |

| Regulatory Basis | ICH Q2(R2), USP <1225> [19] [20] | USP <1226>, CLIA regulations [15] [20] |

| Resource Intensity | High (time, cost, personnel) [1] | Moderate to low [1] |

Method Suitability Testing

Method Suitability Testing is a compendial concept, often serving as the verification of a pharmacopoeial method for a specific product [22]. It demonstrates that the compendial method is suitable under actual conditions of use and that the product to be tested does not interfere with the method [22]. A prime example is the Sterility Test Method Suitability Test (MST), which proves that the product itself does not possess antimicrobial properties that would lead to false-negative results [22]. In a microbiological context, this test is the verification that the specific product being tested does not inhibit the growth of microorganisms, thereby ensuring the reliability of the sterility test result.

Method Suitability Testing: A Deep Dive into the Sterility Test

Purpose and Principle

The Sterility Test Method Suitability Test is performed to verify under the actual test conditions that the product to be examined does not inhibit the growth of microorganisms. In simple terms, it ensures that any contaminating microorganisms present in the product would be detected and not masked by the product's inherent antimicrobial properties [22]. Without a successful suitability test, a passing sterility test result is invalid, as it could be a false negative [22].

Experimental Protocol

The MST is performed according to pharmacopoeial chapters (e.g., Ph. Eur. 2.6.1, USP <71>, JP 4.06) and must be conducted under aseptic conditions [22]. The following workflow and protocol detail the process for the membrane filtration method, which is preferred when the product is filterable.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Test Preparation: The test is performed under aseptic conditions, such as in a sterile test isolator. A filtration unit with a membrane pore size of ≤ 0.45 µm is used [22].

- Filtration and Rinsing: The membrane is wetted with an appropriate buffer. The product to be tested is filtered, and the membrane is rinsed with a suitable buffer (typically three times with 100 mL) to remove any antimicrobial properties of the product [22].

- Inoculation with Challenge Microorganisms: During the last rinsing step, the membrane is inoculated with a defined inoculum (not more than 100 CFU) of each of the following compendial microorganisms: Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Clostridium sporogenes, Candida albicans, and Aspergillus brasiliensis [22]. These represent potential contaminants from the manufacturing environment.

- Culture Media Addition: Two different liquid culture media are added to the filtration units: Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) for aerobes and fungi, and Fluid Thioglycollate Medium (FTM) for aerobes and anaerobes [22].

- Incubation and Examination: The units are incubated at temperatures specified by the pharmacopoeia (e.g., 20-25°C or 30-35°C) for a maximum of 3 days for bacteria and 5 days for yeasts and molds. They are examined daily for turbidity, which indicates microbial growth [22].

- Interpretation of Results: The growth in the test preparation (with product) is compared to a positive control (inoculated media without product). The test is successful only if the culture media with the product shows growth comparable to the positive control, demonstrating that the product does not inhibit growth [22]. If growth is inhibited, the test conditions (e.g., rinsing volume, use of neutralizing agents) must be modified.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Sterility Test Suitability

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Critical Attribute |

|---|---|---|

| Test Microorganisms | Challenge strains (e.g., S. aureus, B. subtilis, P. aeruginosa, C. sporogenes, C. albicans, A. brasiliensis) to demonstrate growth recovery [22]. | Viable count must be ≤ 100 CFU per strain. |

| Culture Media | TSB and FTM to support the growth of a wide spectrum of bacteria and fungi [22]. | Must have proven growth-promoting properties and be sterile. |

| Membrane Filter | Retains any microorganisms present in the product solution during filtration. | Pore size ≤ 0.45 µm with proven bacterial retention. |

| Rinsing Fluid | Buffered solutions (e.g., Fluid A, D, or K) to remove residual product from the membrane [22]. | Must effectively neutralize or remove antimicrobial properties without harming potential microbes. |

Analytical Method Transfer

Definition and Scope

Analytical Method Transfer is the documented process that qualifies a receiving laboratory (which could be internal or external) to use an analytical method that originated in a transferring laboratory [20] [23]. The goal is to ensure the method produces equivalent results in the receiving lab's environment, with its specific analysts, equipment, and reagents. It applies to previously validated, non-compendial methods. For compendial methods, a method verification is typically performed upon transfer [23].

Approaches and Protocol

The transfer process is governed by a pre-approved protocol that clearly defines objectives, materials, procedures, and acceptance criteria [24] [20]. Common transfer approaches include:

- Comparative Testing: The most common strategy, where the sending and receiving laboratories each conduct replicate testing of the same homogeneous sample(s), and the results are statistically compared for equivalence [24] [23].

- Co-validation: The receiving laboratory participates in the original validation study, performing a part of the validation (e.g., intermediate precision) [21].

- Transfer Waiver: Under specific, justified circumstances (e.g., the receiving lab has a proven history with a very similar method), a full transfer might be waived [20].

A successful transfer requires meticulous planning and assessment of the receiving lab's capabilities, including equipment qualification, analyst training, and availability of reference standards [24].

Regulatory Frameworks and Practical Applications

Guidance and Standards

Adherence to regulatory guidelines is non-negotiable. Key documents include:

- ICH Q2(R2): Provides the international standard for the validation of analytical procedures [19] [20].

- USP General Chapters <1225> (Validation), <1226> (Verification), <1224> (Transfer): Provide detailed requirements for compendial methods [19].

- ISO 16140 Series: Dedicated to the validation and verification of microbiological methods in the food and feed chain, offering a robust model for methodological rigor [2].

Application in Microbiological Testing

The concepts of verification and suitability testing are particularly relevant for established microbiological methods. For instance:

- Bacterial Endotoxin Testing (BET): As a compendial method, transferring the LAL test to a new lab or changing a key reagent (e.g., lysate supplier) does not require full validation. Instead, a comparative testing is performed to verify that the laboratory can construct a satisfactory standard curve and that the product can be tested without interference at the established dilution [24].

- Compendial Verification in Clinical Microbiology: For unmodified, FDA-cleared tests in a clinical lab, verification is required per CLIA regulations. This involves demonstrating accuracy, precision, reportable range, and reference range for the lab's specific patient population [15].

In the rigorous world of pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical development, standardized terminology is the linchpin of quality and compliance. Method Validation is the foundational act of proving a method works for its purpose, while Method Verification confirms a laboratory's ability to implement a pre-validated method. The Method Suitability Test is a critical, product-specific verification for compendial methods, ensuring the product does not interfere with the test. Finally, Method Transfer is the structured process of moving a validated method between laboratories. By adhering to these precise definitions and their associated experimental protocols, organizations can ensure data integrity, streamline regulatory submissions, and ultimately safeguard patient health.

Implementing compliant Protocols: A Step-by-Step Guide to Verification and Validation

Method validation is a documented process that proves an analytical method is acceptable for its intended use [1]. It is a comprehensive exercise involving rigorous testing and statistical evaluation, typically required when developing new methods or transferring methods between labs and instruments [1]. For microbiological methods, validation specifically tests a method's ability to detect target organisms under a particular range of conditions and for particular matrix categories [13]. Unlike method verification, which confirms that a previously validated method performs as expected in a specific laboratory, validation establishes the fundamental performance characteristics of the method itself [1] [13].

Core Validation Parameters and Experimental Protocols

A robust validation protocol systematically assesses key performance parameters. The following table summarizes the essential characteristics, their definitions, and experimental approaches for microbiological methods.

Table 1: Core Parameters for Microbiological Method Validation

| Parameter | Definition | Recommended Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The agreement of results between the new method and a comparative method [15]. | Use a minimum of 20 clinically relevant isolates [15]. For qualitative assays, use a combination of positive and negative samples. Calculate as (number of results in agreement / total number of results) × 100 [15]. |

| Precision | The acceptable within-run, between-run, and operator variance [15]. | Use a minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative samples tested in triplicate for 5 days by 2 operators [15]. For fully automated systems, user variance may not be needed. |

| Specificity | The ability to detect the target organism without interference from other microorganisms or matrix components [1] [13]. | Test against a panel of related and unrelated non-target strains to demonstrate no cross-reactivity. Include samples with potential matrix interferents (e.g., high fat, acidity, or inhibitors like pectin) [13]. |

| Detection Limit | The lowest number of microorganisms that can be reliably detected by the method [1]. | Perform serial dilutions of the target organism to determine the lowest level that yields a positive result ≥95% of the time. |

| Quantitation Limit | The lowest number of microorganisms that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [1]. | For quantitative methods, determine the lowest level at which precision and accuracy targets are met. |

| Linearity | The ability of the method to obtain results directly proportional to the analyte concentration in the sample. | Test across a specified range using reference materials. |

| Robustness | A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [1]. | Introduce small changes in critical parameters (e.g., incubation temperature ±1°C, time ±10%, reagent lot variations) and assess impact on results. |

| Reportable Range | The acceptable upper and lower limits of the test system that can be reported [15]. | Verify using a minimum of 3 samples. For qualitative assays, use known positive samples; for semi-quantitative, use samples near the manufacturer's cutoffs [15]. |

Detailed Protocol: Accuracy and Precision Studies

Accuracy Experimental Methodology:

- Sample Selection: Obtain a minimum of 20 clinically relevant bacterial isolates. For a qualitative assay, this should include a combination of strains known to be positive and negative for the target analyte [15].

- Source Material: Acceptable specimens can be sourced from certified reference materials, proficiency test samples, or de-identified clinical samples that have previously been tested with a validated comparator method [15].

- Testing Procedure: Test all samples using the new method (test method) and the validated comparative method in parallel.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage agreement: (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100. The acceptance criteria should meet the manufacturer's stated claims or what the laboratory director determines is acceptable [15].

Precision Experimental Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Select a minimum of 2 positive and 2 negative control samples. For semi-quantitative assays, use samples with a range of values from high to low [15].

- Testing Schedule: Test each sample in triplicate, over the course of 5 non-consecutive days, using 2 different qualified operators to incorporate between-run and operator variance [15].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percent agreement for each sample type across all replicates and days. The results should meet the pre-defined acceptance criteria for variance.

Method Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key decision points in the method validation process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful method validation relies on high-quality, well-characterized materials. The following table details key reagents and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Microbiological Method Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Strains | Provide a traceable, reliable source of target microorganisms for accuracy, precision, and detection limit studies. |

| Inactivated Clinical Isolates | Broaden the assessment of method specificity by testing against a diverse panel of related and non-target organisms. |

| Matrix-Matched Controls | Assess the impact of the sample background (e.g., food, clinical specimen) on assay performance, crucial for fitness-for-purpose. |

| Selective & Non-Selective Growth Media | Used for culture-based comparator methods and to ensure the method can detect viable organisms in the presence of inhibitors. |

| Sample Preparation Buffers & Reagents | Critical for liberating microorganisms from complex matrices and neutralizing potential interferents like enzymes or antibiotics. |

| Molecular-Grade Water & Negative Controls | Establish the baseline for specificity and ensure no false positives arise from contaminated reagents or environmental background. |

| Anteisopentadecanoyl-CoA | Anteisopentadecanoyl-CoA, MF:C36H64N7O17P3S, MW:991.9 g/mol |

| 10-MethylHexadecanoyl-CoA | 10-MethylHexadecanoyl-CoA, MF:C38H68N7O17P3S, MW:1020.0 g/mol |

Navigating Regulatory and Matrix Considerations

Method validation is required by international regulatory bodies for new drug submissions, diagnostic test approvals, and environmental monitoring protocols [1]. Guidelines from organizations like the FDA, ICH, USP, AOAC, and ISO provide frameworks for validation protocols [1] [13].

A critical concept in microbiological validation is "fitness-for-purpose," which demonstrates that the method delivers expected results in a specific sample matrix [13]. If a method has been validated for a particular matrix, it is considered fit-for-purpose. If not, the laboratory must evaluate whether a matrix extension study is needed [13]. The first step is to consider the food matrix grouping, where products are categorized based on similar characteristics (e.g., AOAC guidelines consider eight food categories divided into 92 subcategories) [13]. The extent of additional testing required depends on the public health risk and the detection risk associated with the new matrix [13].

In the context of microbiological testing, the implementation of a compendial method or a method validated by a third party requires a laboratory to perform method verification. This process is distinct from method validation; verification confirms that a pre-validated method performs as expected in your specific laboratory environment, with your analysts, equipment, and reagents [25] [19]. It is a targeted assessment to demonstrate suitability under actual conditions of use, not a repeat of the full validation process [26]. Framed within a broader methodology, verification is a critical step that ensures the ongoing reliability and regulatory compliance of established methods upon their adoption into a new setting.

Method Verification vs. Validation: A Foundational Distinction

Understanding the distinction between verification and validation is crucial for selecting the correct protocol. The following table summarizes the key differences.

Table 1: Core Differences Between Method Verification and Method Validation

| Aspect | Method Verification | Method Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Confirming a previously validated method performs suitably in a specific laboratory [1] [26]. | A comprehensive process to establish and document that a method is fit for its intended purpose [19] [1]. |

| Core Question | "Can we use this existing method successfully in our lab?" | "Is this new method reliable and fit for its purpose?" |

| Scope | Limited assessment of critical performance characteristics [19]. | Full assessment of all relevant performance characteristics [19]. |

| When Performed | When adopting a compendial (e.g., USP, Ph. Eur.) or a transferred method [19] [1]. | When developing a new method or significantly modifying an existing one [19] [26]. |

| Regulatory Basis | USP General Chapter <1226> "Verification of Compendial Procedures" [25] [19]. | ICH Q2(R2) "Validation of Analytical Procedures" [19] [1]. |

The relationship between these processes and other related activities can be visualized in the method lifecycle workflow below.

Designing the Verification Protocol

A robust verification protocol is a pre-approved document that specifies the objectives, methodology, acceptance criteria, and responsibilities for the study.

Determining the Verification Scope

The extent of verification is not one-size-fits-all. It depends on factors such as the complexity of the procedure, the training and experience of the analyst, the type of equipment, and the specific article being tested [25]. For a standard compendial microbiological method like sterility testing or bioburden determination, the verification typically focuses on demonstrating precision and specificity under the new laboratory's conditions [25] [19]. Accuracy may also be assessed, depending on the specific situation of the sample being tested [25].

Key Performance Characteristics for Verification

The following characteristics are typically evaluated during verification, with the selection tailored to the method's intended use.

Table 2: Key Performance Characteristics for Method Verification

| Characteristic | Definition | Typical Verification Approach in Microbiology |

|---|---|---|

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample. | Analyze multiple aliquots (e.g., n=6) of a homogeneous sample. Calculate the standard deviation and relative standard deviation. |

| Specificity | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of components that may be expected to be present. | Demonstrate that the method can detect the target microorganism in the presence of the product's matrix and normal flora. |

| Accuracy/Trueness | The closeness of agreement between the accepted reference value and the value found. | Use spiked samples with known concentrations of the target microorganism and calculate recovery. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified. | Confirm the method can detect a low-level inoculum of the target microorganism that is near the expected detection limit. |

Experimental Methodology: The Comparison Study

A core experiment in many verification protocols is the comparison of method results against a reference or the documented method performance.

Protocol for a Quantitative Comparison Study

This methodology is critical for estimating the systematic error, or inaccuracy, of the method when implemented in your lab [27].

- Sample Preparation: Select a minimum of 40 different patient specimens or samples [27]. These should be selected to cover the entire working range of the method and represent the expected sample matrix [27].

- Testing Period: The experiment should be performed over a minimum of 5 different days to account for day-to-day variability [27].

- Analysis: Analyze each specimen using the new method (test method) and the comparative method. Common practice is to analyze each specimen singly by both methods, but duplicate measurements are advantageous for identifying discrepancies [27].

- Data Analysis:

- Graph the Data: Create a difference plot (test result minus comparative result vs. comparative result) or a comparison plot (test result vs. comparative result) to visually inspect the data for patterns and outliers [27].

- Calculate Statistics: For data covering a wide analytical range, use linear regression analysis to determine the slope, y-intercept, and standard deviation about the regression line (s~y/x~). The systematic error (SE) at a critical decision concentration (X~c~) is calculated as: SE = (a + bX~c~) - X~c~, where 'a' is the y-intercept and 'b' is the slope [27].

The workflow for executing this core experiment is detailed below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table outlines key materials required for a typical microbiological method verification study.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiological Verification

| Item | Function in Verification |

|---|---|

| Reference Strains | Certified microbial strains (e.g., from ATCC) used to demonstrate specificity, precision, and accuracy by serving as a known positive control. |

| Culture Media | Growth media specified in the compendial method. Used to support the growth and detection of microorganisms; performance must be verified. |

| Neutralizers/Inactivators | Critical for antimicrobial effectiveness testing and bioburden methods to neutralize disinfectants or antimicrobial agents in the sample. |

| Sample Matrix (Placebo) | The product or material without the active ingredient. Used to prepare negative controls and to spike with reference strains for recovery studies. |

| Validated Spiking Inoculum | A suspension of reference microorganisms with a known and verified concentration, used in accuracy/recovery experiments. |

| 10(Z)-Heptadecenyl acetate | 10(Z)-Heptadecenyl acetate, MF:C19H36O2, MW:296.5 g/mol |

| (10Z,13Z,16Z)-3-oxodocosatrienoyl-CoA | (10Z,13Z,16Z)-3-oxodocosatrienoyl-CoA, MF:C43H70N7O18P3S, MW:1098.0 g/mol |

Data Analysis and Acceptance Criteria

The data generated from verification experiments must be evaluated against pre-defined, scientifically justified acceptance criteria. These criteria should be based on the intended use of the method and any regulatory guidance.

Table 4: Example Acceptance Criteria for Key Verification Parameters

| Parameter | Example Acceptance Criterion for a Quantitative Method |

|---|---|

| Precision (Repeatability) | Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) ≤ 15% for biological methods. |

| Accuracy (Recovery) | Mean recovery of the target microorganism between 70% and 130%. |

| Specificity | No interference from the sample matrix; clear detection of the target organism. |

| Linearity | Correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.98 over the specified range. |

For the comparison of methods experiment, the estimated systematic error at a medically or functionally critical decision level should be less than the allowable total error based on the method's intended use [27] [28].

A well-executed method verification protocol is a cornerstone of quality assurance in a microbiological laboratory. It provides documented evidence that a pre-validated method is under control and suitable for its intended use within a specific laboratory's environment. By following a structured approach—defining the scope, executing targeted experiments, and analyzing data against strict acceptance criteria—researchers and drug development professionals can ensure the generation of reliable, high-quality data that supports product safety and regulatory compliance.

Within pharmaceutical development and clinical diagnostics, the reliability of microbiological testing is paramount for ensuring drug safety and patient health. This reliability hinges on two distinct but complementary laboratory processes: method validation and method verification [13] [1]. Method validation is the comprehensive process of proving that an analytical method is acceptable for its intended use, establishing its performance characteristics during development or transfer [1]. Method verification, by contrast, is the process whereby a laboratory confirms that a previously validated method performs as expected in its specific environment, with its personnel and equipment [13] [29].

The distinction, while subtle, is critical. Validation asks, "Does this method work for its intended purpose in general?" while verification asks, "Can our laboratory perform this method correctly?" [14]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this difference is a strategic necessity for regulatory compliance and scientific integrity [1].

This guide provides an in-depth examination of the four core performance parameters—Accuracy, Precision, Detection Limit, and Reportable Range—within the context of method verification, offering a practical framework for their assessment in a laboratory setting.

Core Performance Parameters in Method Verification

When a laboratory implements a new, previously validated method (e.g., an FDA-cleared or compendial method), it must verify key performance characteristics as required by standards such as the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) [29]. The following parameters are central to this verification process for qualitative and semi-quantitative microbiological assays.

Accuracy

Accuracy measures the agreement between the results from the new method and those from a comparative method, confirming the method's ability to correctly identify the target analyte [29]. It is a fundamental indicator of a method's freedom from error.

Experimental Protocol for Verifying Accuracy:

- Sample Number and Type: A minimum of 20 clinically relevant isolates or samples should be used. These should include a combination of positive and negative samples for qualitative assays, or a range of samples with high to low values for semi-quantitative assays [29].

- Sample Sources: Acceptable specimens can be sourced from reference materials, proficiency test samples, standardized controls, or de-identified clinical samples that have previously been tested with a validated method [29].

- Testing Procedure: Each sample is tested in parallel using the new method (the test method) and the established comparative method.

- Calculation: Accuracy is calculated as the percentage of results where the new method agrees with the comparative method.

Accuracy (%) = (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100[29]. - Acceptance Criteria: The calculated percentage of agreement should meet or exceed the performance claims made by the method's manufacturer or a threshold determined by the laboratory director [29].

Precision

Precision, or reliability, evaluates the degree of agreement among repeated measurements from the same homogeneous sample. It assesses the random error of a method and is typically broken down into within-run (repeatability) and between-run (reproducibility) variance [1] [29].

Experimental Protocol for Verifying Precision:

- Sample Number and Type: A minimum of two positive and two negative samples are tested. For semi-quantitative assays, samples should cover a range from high to low values [29].

- Testing Procedure: The selected samples are tested in triplicate over the course of five days by two different operators. If the test system is fully automated, testing for operator variance may not be necessary [29].

- Calculation: Precision is calculated for each level of sample as the percentage of agreement between the replicate results.

Precision (%) = (Number of results in agreement / Total number of results) × 100[29]. - Acceptance Criteria: As with accuracy, the results should conform to the manufacturer's stated claims or the laboratory's predefined acceptance criteria [29].

Detection Limit

The Limit of Detection (LOD) is the lowest quantity or concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from its absence. For a qualitative method, this is the smallest amount of target microorganism that yields a positive result [1].

Experimental Protocol for Verifying the LOD:

- Objective: To confirm that the LOD stated by the method's manufacturer can be achieved under the laboratory's specific conditions.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare samples spiked with the target microorganism at a concentration near the claimed LOD. Serial dilutions may be used to bracket the manufacturer's stated detection limit.

- Testing Procedure: The spiked samples are tested repeatedly (e.g., in multiple replicates) using the new method.

- Evaluation: The LOD is verified as the lowest concentration at which ≥95% of the replicates test positive [1]. The laboratory confirms that its results are consistent with the validation data provided by the manufacturer.

Reportable Range

The reportable range defines the upper and lower limits of the analyte that the method can directly measure without modification, such as dilution or concentration. It establishes the bounds of what constitutes a valid, reportable result [29].

Experimental Protocol for Verifying the Reportable Range:

- Sample Number and Type: A minimum of three samples is recommended. For qualitative methods, use known positive samples. For semi-quantitative assays, use samples with values near the upper and lower cutoffs established by the manufacturer [29].

- Testing Procedure: Test the selected samples using the new method.

- Evaluation: The reportable range is verified by confirming that the results for all tested samples fall within the limits defined by the manufacturer and that they are reported appropriately (e.g., "Detected," "Not detected," or a specific cycle threshold value) [29].

Table 1: Summary of Core Verification Parameters and Protocols

| Parameter | Definition | Experimental Protocol Summary | Key Calculations/Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Agreement with a reference method [29] | - 20 samples (pos/neg mix)- Test vs. comparative method | % Agreement = (Agreements/Total) x 100Meet mfr. claims or lab criteria [29] |

| Precision | Closeness of repeated measurements [29] | - 2 pos & 2 neg samples- Triplicate, 5 days, 2 operators | % Agreement between replicatesMeet mfr. claims or lab criteria [29] |

| Detection Limit | Lowest detectable analyte level [1] | - Samples spiked near claimed LOD- Multiple replicate tests | Lowest concentration with ≥95% positive rateConfirm mfr.-stated LOD [1] |

| Reportable Range | Range of reportable results [29] | - 3 samples across the range- Test with new method | Results fall within mfr.-defined limits and are reported correctly [29] |

The Experimental Workflow for Method Verification

Executing a method verification study requires careful planning. The following workflow diagram and accompanying explanation outline the key stages, from initial planning to final implementation for routine use.

Diagram 1: Method Verification Workflow

1. Define Purpose and Assay Type: The first step is to confirm that the study is a verification (for an unmodified, previously validated method) and not a validation (required for laboratory-developed tests or modified methods) [29]. The assay type—qualitative, quantitative, or semi-quantitative—must be defined, as this determines the specific verification protocols [29].

2. Create a Written Verification Plan: Before beginning experimental work, a detailed plan must be drafted and signed off by the laboratory director. This plan is a blueprint for the entire study and should include [29]:

- The purpose of the test and a description of the method.

- The study design, specifying the number and types of samples, quality controls, number of replicates, analysts, and the performance characteristics to be evaluated (e.g., Accuracy, Precision) along with their acceptance criteria.

- A list of all required materials, equipment, and resources.

- Safety considerations and an expected timeline for completion.

3. Conduct Verification Experiments: The laboratory executes the experiments as outlined in the verification plan. This involves testing the specified samples for accuracy, precision, reportable range, and other relevant parameters according to the predefined methodology [29].

4. Analyze Data and Compile Report: The data collected from the experiments are analyzed and compared against the acceptance criteria. The results, along with a detailed description of the process, are compiled into a verification report [14].

5. Director Review and Approval: The final verification report is submitted to the laboratory director for formal review and approval. Once approved, the method can be released for routine diagnostic use [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successfully conducting a verification study requires access to well-characterized biological and chemical materials. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions in the process.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Verification Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Verification |

|---|---|

| Reference Strains (QC Strains) | Well-characterized microbial strains used as positive controls, for spiking studies to assess accuracy and LOD, and for precision testing [29]. |

| Clinical Isolates / De-identified Samples | Provide real-world, complex matrices to confirm method performance correlates with the validated comparative method during accuracy testing [29]. |

| Proficiency Test (PT) Samples | Blinded samples of known value from an external provider; provide an objective assessment of accuracy and help identify potential systematic errors [29]. |

| Quality Controls (QC) | Includes positive, negative, and internal controls. They are run with each batch to monitor the test system's performance and ensure day-to-day reliability [29]. |

| Selective Agar Media | Used for the isolation and confirmation of target microorganisms, forming part of the comparative method against which a new method is verified [2]. |

| Molecular Detection Kits (e.g., PCR) | Commercial kits (e.g., for Salmonella or Listeria detection) provide the core reagents for the test method itself and must be used as specified by the manufacturer [30]. |

| (2E,9Z)-octadecadienoyl-CoA | (2E,9Z)-octadecadienoyl-CoA, MF:C39H66N7O17P3S, MW:1030.0 g/mol |

| (2R)-2-methyltetradecanoyl-CoA | (2R)-2-methyltetradecanoyl-CoA, MF:C36H64N7O17P3S, MW:991.9 g/mol |

The rigorous assessment of accuracy, precision, detection limit, and reportable range forms the bedrock of a reliable microbiological method verification. This process, distinct from the broader scope of method validation, provides documented evidence that a laboratory can successfully implement a standardized method within its own operational environment. For researchers and professionals in drug development, mastering these concepts and protocols is not merely a regulatory hurdle but a fundamental component of quality assurance. It ensures that the data generated in the laboratory is scientifically sound, reproducible, and ultimately fit for making critical decisions regarding product safety and public health.

Within the framework of microbiological method verification and validation research, a foundational distinction dictates all subsequent study design: verification is for unmodified, FDA-approved tests to confirm that a test performs as established in your laboratory, while validation is a more extensive process to establish that a new or modified test works as intended for its specific purpose [15]. International standards like ISO 15189:2022 and the European In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR) have intensified the need for robust, well-documented procedures for both verification and validation [31]. The choice between a qualitative and quantitative assay is the primary determinant of the statistical approach, sample size, and experimental protocols required to satisfy these regulatory and scientific demands. This guide provides a detailed examination of the minimum requirements for study design and sample size, contextualized for researchers and drug development professionals establishing reliability in microbiological testing.

Core Differences Between Qualitative and Quantitative Assays

Understanding the fundamental distinctions between qualitative and quantitative methods is essential for selecting the correct validation pathway. The table below summarizes the key characteristics.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Qualitative and Quantitative Microbiological Assays

| Aspect | Qualitative Assays | Quantitative Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Data Type | Descriptive, categorical (e.g., Present/Absent, Detected/Not Detected) [32] | Numerical, measurable (e.g., CFU/g, CFU/mL) [32] |

| Primary Objective | Detection or identification of a specific microorganism or attribute [33] | Enumeration or precise measurement of microorganism population [33] |

| Reportable Result | "Positive/25g" or "Not Detected/375g" [33] | Numerical value, such as "1.5 x 10³ CFU/g" [33] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Very low, theoretically 1 CFU per test portion [33] | Higher, typically 10-100 CFU/g for plate counts [33] |

| Common Examples | Tests for Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, STEC [33] | Aerobic Plate Count (APC), Staphylococcus aureus enumeration, yeast and mold counts [33] |

| Statistical Analysis | Percent agreement, sensitivity, specificity, positive/negative predictive value [34] | Standard deviation, coefficient of variation, confidence intervals, regression analysis [32] [34] |