Microbial Community Assembly and Succession: Ecological Drivers, Methodological Advances, and Biomedical Applications

This article synthesizes current research on microbial community assembly and succession, exploring the foundational ecological principles that govern these processes.

Microbial Community Assembly and Succession: Ecological Drivers, Methodological Advances, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on microbial community assembly and succession, exploring the foundational ecological principles that govern these processes. It delves into the methodological toolkit used for investigation, from high-throughput sequencing to network analysis, and addresses key challenges in predicting and manipulating microbiomes. By comparing assembly patterns across diverse ecosystems—from the human body to engineered and natural environments—this review validates core ecological theories and highlights their profound implications for developing microbiome-based therapeutics and diagnostics. The content is tailored to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding and harnessing microbial communities for biomedical innovation.

The Ecological Principles Governing Microbial Assembly and Succession

Microbial Community Succession refers to the predictable and gradual changes in the types of microbial species inhabiting a particular environment over time [1]. This process is characterized by directional, predictable change in community structure as time passes over years to centuries, involving significant shifts in the presence and relative abundance of different species [2]. While often considered in the context of plant communities, succession fundamentally involves coordinated shifts in microbial populations including bacteria, archaea, fungi, and other microorganisms [2] [3].

In essence, microbial community succession represents the dynamic story of how microbial populations change in a habitat over time, driven by environmental shifts and biological interactions [1]. These successional patterns are governed by a complex interplay of deterministic environmental pressures and stochastic biological events, resulting in predictable transitions in community structure and function [1]. The study of these patterns has evolved significantly from classical ecological theories to modern molecular approaches that can quantify absolute abundance and functional changes throughout succession [4] [3].

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Classical Succession Theory

The conceptual foundation of succession traces back to Henry Cowles' 1899 study of sand dunes along Lake Michigan, where he first characterized successional patterns using a chronosequence approach - a "space-for-time" substitution that predicts temporal vegetation patterns based on spatial gradients representing different succession ages [2]. This work established the fundamental principle that ecological communities develop in predictable sequences over time.

Frederick Clements later championed the concept of a climax state, proposing that after disturbance, ecosystems would eventually return to a characteristic, stable end-stage community [2]. Clements viewed this climax community through a super-organism concept, where all species worked together to maintain stable composition [2]. This perspective emphasized the extreme predictability of successional pathways.

In contrast, Henry Gleason argued for an individualistic concept of succession, viewing communities as fortuitous assemblies of species with no predetermined climax state [2]. Gleason emphasized that environmental conditions and species movement regulated community assemblages, making succession less predictable than Clements proposed [2]. This historical debate continues to influence modern microbial ecology, with contemporary research recognizing elements of both predictability and stochasticity in microbial succession patterns.

Modern Ecological Perspectives

Current understanding acknowledges that while successional processes are less deterministic than originally proposed by Clements, several predicted patterns generally hold true across ecosystems [2]. Species diversity tends to increase with successional age, as observed after the eruption of Mount St. Helens, where ecologists documented a steady increase in species diversity over time [2].

Eugene Odum described predictable differences between early and late successional systems, where early successional systems typically feature smaller plant biomass, shorter plant longevity, faster nutrient consumption rates, and lower stability compared to late successional systems [2]. Similarly, Fakhri Bazzaz characterized physiological differences, with early successional plants having high rates of photosynthesis and resource uptake, while late successional plants exhibit opposite characteristics [2].

Modern microbial ecology recognizes succession as a context-dependent trajectory influenced by both predictable environmental forces and stochastic biological events, leading to contingent community states rather than a singular, deterministic climax [1]. This perspective integrates both niche-based processes and neutral processes to explain the complex dynamics observed in microbial systems.

Stages of Microbial Succession

Microbial community succession typically progresses through distinct stages characterized by specific microbial groups and functional attributes. The progression through these stages represents a fundamental ecological process with far-reaching implications for ecosystem resilience, functional stability, and response to perturbations [1].

Table 1: Characteristics of Successional Stages in Microbial Communities

| Successional Stage | Key Characteristics | Microbial Life Strategies | Environmental Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pioneer Stage | Initial colonization by stress-tolerant species; fast growth; low diversity | r-strategists; generalist metabolisms; rapid reproduction | Pioneer species alter pH, nutrient availability, and soil structure |

| Intermediate Stage | Increasing diversity and biomass; specialized metabolic guilds establish | Mix of r- and K-strategists; diverse functional capabilities | Enhanced nutrient cycling; complex interactions develop |

| Climax Stage | Relatively stable community; high diversity; efficient resource utilization | K-strategists; specialist metabolisms; competitive dominance | Stable micro-environments; efficient nutrient cycling |

Pioneer Stage

The pioneer stage represents the initial phase of succession, characterized by the arrival and establishment of pioneer species [1]. These pioneer microbes are typically well-adapted to harsh or nutrient-poor conditions and are often fast-growing organisms capable of utilizing readily available resources [1]. In newly formed habitats, such as recently sterilized soil or freshly exposed substrates, these pioneers might include bacteria that can utilize atmospheric carbon dioxide or simple inorganic compounds [1].

Pioneer species play a crucial role in modifying the environment to make it more hospitable for subsequent colonizers. For example, in Glacier Bay, Alaska, following glacier retreat, pioneer communities consisting of lichens, liverworts, and forbs initially colonize the newly exposed terrain [2]. These organisms begin the process of soil formation and nutrient accumulation that enables later successional stages to establish.

Intermediate Stage

As pioneer species modify the environment, conditions become more favorable for other microbial groups, initiating the intermediate stage of succession [1]. This stage sees a significant increase in microbial diversity and biomass as different microbial guilds with specialized metabolic capabilities establish themselves [1]. The intermediate stage typically features a more complex community structure with more intricate biological interactions.

In the classic example of Glacier Bay succession, the pioneer community gives way to creeping shrubs such as Dryas, followed by larger shrubs and trees like alder [2]. Each of these transitions represents a shift in the associated microbial communities, with different functional groups dominating at different stages. The intermediate stage often features a mix of facilitation and inhibition mechanisms that regulate the pace and trajectory of succession [2].

Climax Stage

In theory, succession can lead to a relatively stable climax community, characterized by high diversity, complex interactions, and efficient resource utilization [1]. The climax community is considered to be in equilibrium with prevailing environmental conditions, though in microbial ecology, the concept of a fixed climax stage is debated due to constantly changing environments and frequent disturbances [1].

In the Glacier Bay succession sequence, the climax community is represented by spruce forest that establishes over approximately 1,500 years [2]. However, modern ecological understanding recognizes that climax states may be transient and context-dependent, with microbial communities continually adapting to environmental changes rather than reaching a permanent stable state [1].

Mechanisms Driving Succession

The progression through successional stages is governed by multiple ecological mechanisms that operate simultaneously to shape community development. These mechanisms can be broadly categorized into niche-based processes and neutral processes, though in reality, both often operate simultaneously to influence successional trajectories [1].

Table 2: Mechanisms Driving Microbial Community Succession

| Mechanism Type | Specific Process | Impact on Succession | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Niche-Based Processes | Environmental Filtering | Selects for microbes with advantageous traits under specific conditions | Oxygen availability filtering for aerobes; pollution gradients selecting resistant strains |

| Resource Competition | Alters community composition based on competitive abilities | Primary substrate depletion creating advantages for alternative metabolisms | |

| Facilitation | One species positively influences establishment of another | Nitrogen fixation by pioneers benefiting subsequent colonizers | |

| Neutral Processes | Dispersal Limitation | Random arrival or non-arrival of species impacts early community | Geographical barriers influencing which species colonize new habitats |

| Ecological Drift | Random birth, death, and colonization events change composition | Stochastic population fluctuations in high-diversity communities | |

| Historical Contingency | Sequence of events and initial conditions have lasting impacts | Different starting communities leading to divergent trajectories |

Fundamental Mechanisms

Connell and Slatyer (1977) proposed three fundamental mechanisms by which communities progress through successional sequences: facilitation, tolerance, and inhibition [2]. Facilitation occurs when early colonizers alter the environment in ways that make it more habitable for later successional species [2]. This represents the most common mechanism proposed to explain succession.

In Glacier Bay succession, both facilitation and inhibition act as mechanisms regulating the process [2]. For example, both Dryas and alders increase soil nitrogen through facilitation, which enhances establishment and growth of spruce seedlings [2]. Simultaneously, both species produce leaf litter that can inhibit spruce germination and survival, demonstrating how multiple mechanisms can operate concurrently [2].

Niche-Based Processes

Environmental filtering represents a deterministic process where environmental conditions select for microbes with traits that are advantageous under those specific conditions [1]. This filtering effect strongly influences successional trajectories by determining which species can persist at different stages. Examples include oxygen availability selecting for aerobic bacteria in oxygenated environments, or pollution gradients favoring microbes with resistance mechanisms [1].

Resource competition intensifies as communities develop, with species competing for limited nutrients and space [1]. As pioneer microbes consume readily available substrates, they create competitive disadvantages for species that rely on these same resources while creating opportunities for microbes capable of utilizing byproducts or less accessible compounds [1]. This competition drives functional diversification throughout succession.

Stochastic Processes

Dispersal limitation represents a key stochastic factor in succession, where the random arrival or non-arrival of certain species can significantly impact early community assembly [1]. The ability of microbes to reach a new habitat is not unlimited but is influenced by geographical barriers, wind, water currents, and animal vectors [1].

Ecological drift describes how microbial community composition can change over time due to random birth, death, and colonization events, even in the absence of strong environmental selection [1]. This effect is particularly relevant in communities with high diversity and functional redundancy, where many species may be functionally similar [1].

Methodologies for Studying Microbial Succession

Modern approaches to studying microbial succession integrate sophisticated laboratory techniques with computational analyses to characterize community structure, function, and dynamics. These methodologies have evolved significantly from early observational approaches to current high-throughput molecular methods.

Community Composition Analysis

16S rRNA gene sequencing represents the gold standard in microbial ecology for assessing community composition [3]. This high-throughput approach involves sequencing amplicons obtained using universal primers targeting specific variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene, enabling identification and measurement of the relative abundance of phylotypes in a sample [3]. For eukaryotic communities, Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) sequencing provides analogous information for fungi and other microbial eukaryotes [4].

Quantitative Microbiome Profiling (QMP) has emerged as a crucial advancement beyond relative abundance measurements [4]. QMP provides absolute abundance data that can reveal strikingly different, even opposing successional trends compared to relative abundance profiling [4]. For example, during carcass decomposition, Pseudomonadota displayed a decreasing trend based on relative abundance profiling, whereas QMP revealed an increasing trend [4].

Absolute Abundance Quantification

Several methods enable quantification of absolute population counts, which are essential for accurate understanding of microbial dynamics [3]. These include:

- Optical density measurements providing a fast, inexpensive proxy for cell density, though subject to limitations from cellular traits like adhesion, shape, and size [3]

- Direct cell counts using fluorescent stains and cell-counting chambers or flow cytometry, offering greater precision with live/dead discrimination capabilities [3]

- qPCR normalization against host-derived housekeeping genes in host-associated communities [3]

- Microbial panorama profiling program (MP3) methods that integrate high-throughput sequencing, spike-in standards, and 16S/18S rRNA gene copy correction for cross-kingdom abundance quantification [5]

Functional Assessment

Metagenomics involves sequencing all DNA extracted from a sample, cataloging the full complement of genes from an entire community and revealing the potential functions that can be expressed [3]. There is generally good correspondence between gene and transcript relative abundances in microbial communities [3].

Metatranscriptomics provides more accurate assessment of gene expression by sequencing RNA transcripts, pinpointing genes being actively expressed at a given moment and allowing observation of phenotypic adaptation [3]. This approach reveals the functional response of microbial communities to changing environmental conditions throughout succession.

Microbial Succession Analysis Workflow

Experimental Approaches and Research Reagents

The study of microbial succession employs diverse experimental approaches and specialized reagents to elucidate community assembly patterns. These methods range from field observations to controlled laboratory experiments, each with specific advantages for addressing different research questions.

Experimental Designs

Chronosequence studies represent a fundamental approach where researchers examine sites of different ages since disturbance but with similar environmental conditions [2]. This "space-for-time" substitution allows prediction of temporal patterns based on spatial gradients representing different succession ages [2]. This approach was pioneered by Henry Cowles in his 1899 study of sand dune succession along Lake Michigan [2].

Long-term temporal sampling involves repeated sampling of the same location over time to directly observe successional changes [6]. This approach was used in studies of straw return practices in agricultural ecosystems, where researchers monitored bacterial communities over multiple years to understand long-term effects of different management practices [6]. Such longitudinal designs provide the most direct evidence of successional patterns but require substantial time investments.

Manipulative experiments allow researchers to test specific mechanisms by intentionally altering environmental conditions or community composition [3]. These approaches can range from microcosm studies in controlled laboratory settings to field manipulations that modify factors like nutrient availability, disturbance regimes, or initial community composition [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Succession Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application in Succession Research | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Soil DNA extraction kits; PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit | Obtain high-quality DNA from complex environmental samples for sequencing | Efficiency varies by sample type; may require optimization for different matrices |

| PCR and Sequencing Reagents | 16S/18S/ITS PCR primers; sequencing library preparation kits | Amplify and prepare biomarker genes for high-throughput sequencing | Primer selection critical for taxonomic coverage; may introduce amplification bias |

| Quantitative Standards | Spike-in standards; internal reference materials | Normalize for technical variation in sample processing and sequencing | Must be phylogenetically distant from sample community to avoid interference |

| Cell Staining Reagents | DAPI, SYBR Green, propidium iodide; FISH probes | Microscopic enumeration and identification of specific microbial groups | FISH allows phylogenetic identification but limited to cultivable reference strains |

| Metabolomic Analysis Kits | Metabolite extraction kits; derivatization reagents | Characterize metabolic profiles and functional changes during succession | Requires careful sample preservation to maintain metabolite integrity |

Applications and Research Implications

Understanding microbial community succession has profound implications across diverse fields, from ecosystem management to biotechnology and medicine. The predictable nature of successional patterns enables researchers to manipulate these processes for beneficial outcomes.

Restoration Ecology

The principles of microbial succession are directly applied in restoration ecology, where managers attempt to accelerate successional processes to reach desired climax communities [2]. For example, prairie restoration efforts try to recreate prairie climax communities within 10 years, a process that would naturally take several hundred years [2]. Restoration managers manipulate succession mechanisms by increasing seed availability, reducing competition by early-successional species, and amending soil to better match late-succession conditions [2].

In agricultural systems, understanding succession informs practices like straw return, where different incorporation methods significantly alter bacterial community structure and function [6]. Research has shown that deep plowing with straw incorporation (DPR) and no-tillage straw covering (NTR) enhance bacterial adaptation to environmental stress by improving soil conditions, demonstrating how management can steer successional trajectories toward desired outcomes [6].

Biogeochemical Cycling

Microbial succession plays crucial roles in global element cycling, with different successional stages characterized by distinct metabolic processes [5]. In landfill systems, research has revealed that microbial abundance, assembly, and interactions are primarily governed by reducing equivalents derived from organic matter degradation [5]. Early successional stages in landfills are characterized by extensive organic matter fermentation and multi-pathway methanogenesis driven by fermenters and methanogenic archaea [5].

As succession progresses in these systems, aerobic heterotrophs become increasingly important in element cycling, while archaea-mediated methanogenic activities diminish [5]. In later stages, heterotrophic bacteria and fungi may synergistically degrade recalcitrant organic matter, demonstrating how successional changes directly influence ecosystem-scale biogeochemical processes [5].

Forensic Applications

Microbial succession patterns have found applications in forensic science, particularly in estimating postmortem intervals (PMI) [4]. During carcass decomposition, microbial communities undergo predictable successional changes that can be used to model time since death [4]. Research has shown that quantitative microbiome profiling (QMP) approaches may provide different successional trends compared to relative abundance profiling, highlighting the importance of methodological considerations in applied contexts [4].

However, recent research indicates that using QMP does not substantially enhance the accuracy of PMI estimation compared to relative abundance approaches, suggesting that relative microbial patterns may contain sufficient information for this application despite their limitations [4]. This demonstrates how understanding the practical limitations of succession-based models is crucial for their appropriate application.

Microbial community succession represents a fundamental ecological process that follows predictable patterns while retaining elements of context-dependent variability. From initial colonization by pioneer species to the development of complex climax communities, successional trajectories are shaped by the interplay of deterministic environmental filtering, biological interactions, and stochastic events including dispersal limitation and ecological drift. Modern methodological advances, particularly in absolute abundance quantification and functional profiling, have revolutionized our understanding of these processes, revealing both conserved patterns and system-specific variations across different habitats.

The study of microbial succession has evolved significantly from early observational approaches to current mechanistic investigations that integrate sophisticated molecular techniques with ecological theory. This progression has enabled applications across diverse fields including ecosystem restoration, agriculture, biogeochemistry, and forensic science. As research continues to unravel the complex rules governing microbial community assembly, our ability to predict, manage, and manipulate these processes for beneficial outcomes will continue to advance, highlighting the enduring importance of succession as a central concept in microbial ecology.

A central goal in microbial ecology is to establish the importance of deterministic and stochastic processes for community assembly, which is crucial for explaining and predicting how diversity changes across different temporal and spatial scales [7]. In any ecosystem, the composition of a microbial community is the result of a complex interplay between these fundamental forces. Deterministic processes, also known as niche-based processes, are the result of selection imposed by the abiotic environment (environmental filtering) and by biotic interactions, such as competition, mutualism, and antagonism [7] [8]. Conversely, stochastic processes, or neutral-based processes, incorporate randomness and uncertainty, including chance colonization, random extinction, ecological drift, and unpredictable dispersal events [7] [9].

Understanding the balance between these processes is not merely theoretical; it provides a mechanistic and predictive framework for understanding microbial biogeography. This is particularly relevant in applied fields such as drug development, where the human microbiome's response to interventions can determine efficacy, and in environmental science, for managing ecosystems and predicting their responses to anthropogenic disturbances [10] [8]. This guide synthesizes current research to unravel the blueprint governing microbial community assembly and succession.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Deterministic Processes

Deterministic processes suggest that community composition can be predicted from the environmental conditions and species traits.

- Homogeneous Selection: A deterministic process where consistent environmental conditions across locations or times lead to low compositional turnover (i.e., communities become more similar) by selecting for the same taxonomic composition [7].

- Heterogeneous Selection (Variable Selection): A deterministic process where differing or shifting environmental factors lead to high compositional turnover (i.e., communities become more dissimilar) by selecting for different taxa in different conditions [10] [7].

Stochastic Processes

Stochastic models acknowledge inherent randomness, where the same set of initial conditions can lead to an ensemble of different outputs [11] [9].

- Homogenizing Dispersal: A stochastic process where high rates of dispersal and successful migration between communities lead to low compositional turnover, making communities more similar [7].

- Dispersal Limitation: A stochastic process where a low rate of dispersal leads to high compositional turnover, as communities become more different due to isolation [7].

- Ecological Drift: Changes in species abundance resulting from random birth-death events, which have a disproportionately strong effect in small populations [7].

Table 1: Core Ecological Processes in Microbial Community Assembly

| Process Type | Specific Process | Underlying Mechanism | Impact on Community Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic | Homogeneous Selection | Consistent environmental filters select for similar species. | Decreases compositional turnover (community similarity increases) |

| Heterogeneous Selection | Divergent environmental filters select for different species. | Increases compositional turnover (community similarity decreases) | |

| Stochastic | Homogenizing Dispersal | High rate of successful migration of organisms between communities. | Decreases compositional turnover (community similarity increases) |

| Dispersal Limitation | Limited exchange of organisms between isolated communities. | Increases compositional turnover (community similarity decreases) | |

| Ecological Drift | Random changes in population sizes due to chance birth-death events. | Causes unpredictable fluctuations in species abundances. |

Empirical Evidence from Diverse Ecosystems

Large-scale ecological studies have quantified the relative importance of deterministic and stochastic processes across different biomes, revealing that their balance is not static but depends on environmental context, temporal scale, and the biological traits of the organisms involved.

Soil Ecosystems

A nationwide study of 622 soil samples across six terrestrial ecosystems in the United States found that the assembly processes governing soil bacteria depend heavily on their ecological traits, or "ecotypes" [10].

- Abundant Taxa and Generalists: The assembly of these groups was primarily shaped by deterministic processes [10].

- Rare Taxa and Specialists: The assembly of these groups was predominantly governed by stochastic processes [10].

- Ecosystem Sensitivity: Shrubland bacterial communities exhibited the strongest local environmental selection (a deterministic process) and were identified as particularly sensitive to environmental changes, evidenced by the lowest diversity and least connected co-occurrence network [10].

Freshwater Lakes

Research on an alpine oligotrophic lake and a subalpine mesotrophic lake demonstrated that the relative importance of assembly processes shifts dramatically across time scales [7].

- Annual Scale: Homogeneous selection (a deterministic process) was the dominant assembly process, explaining 66.7% of bacterial community turnover in both lakes [7].

- Short-Term Scale (Daily/Weekly): In the alpine lake, homogenizing dispersal (a stochastic process) became the most important driver, explaining 55% of community turnover [7].

- Trophic State Influence: The bacterial community in the oligotrophic lake showed greater seasonal stability than the community in the more productive mesotrophic lake [7].

Engineered and Stressed Systems

The formation of Black-Odor Waters (BOWs), a result of heavy organic pollution in urban rivers, is a process driven by microbial succession. Laboratory experiments simulating BOWs found that the assembly process was initially dominated by stochastic processes (88%), but as the blackening process progressed, the influence of deterministic processes increased, reducing the stochastic contribution to 51% [8]. This demonstrates a dynamic shift from stochastic to deterministic dominance during ecosystem degradation.

Early Successional Habitats

Succession patterns, or the temporal change in community structure, are also governed by this balance. A study on the epilithic algal matrix (EAM) in coral reefs identified a "chaotic aggregation stage" of approximately one month, characterized by stochastic assembly, before the community transitioned to a more deterministic expansion stage and finally stabilized [12]. Similarly, a ten-year canopy manipulation experiment demonstrated that increased canopy openness significantly altered bacterial community composition in fine woody debris and soil, with decomposition time being the main deterministic factor shaping the community [13].

Table 2: Dominant Assembly Processes Across Ecosystem Types and Conditions

| Ecosystem / Context | Condition / Community Type | Dominant Process | Key Driver or Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil [10] | Abundant Taxa & Generalists | Deterministic | Environmental selection (e.g., soil pH, calcium) |

| Rare Taxa & Specialists | Stochastic | Ecological drift and dispersal limitation | |

| Shrubland Ecosystems | Deterministic | Strong local environmental selection | |

| Freshwater Lakes [7] | Annual Scale | Deterministic | Homogeneous selection (66.7% of turnover) |

| Short-Term (Daily/Weekly) Scale | Stochastic | Homogenizing dispersal (55% of turnover) | |

| Black-Odor Waters [8] | Early Blackening Stage | Stochastic | 88% of community assembly |

| Late Blackening Stage | Stochastic & Deterministic | Stochastic contribution drops to 51% | |

| Temperate Grassland [14] | Nitrogen Addition & Fencing | Deterministic | Alters both composition and structure |

| Mowing | Stochastic | Promotes stochastic change in community structure |

Methodologies for Quantifying Assembly Processes

Experimental Workflow for Microbial Community Analysis

A standard workflow for investigating microbial community assembly and succession, as applied across the studies cited, involves a sequence of field and laboratory procedures [10] [12] [7].

Key Analytical Frameworks

To move from descriptive community data to inferential process quantification, researchers employ specific analytical frameworks:

- Null Model Analysis: This is a core technique for quantifying assembly processes. It compares observed β-diversity (compositional dissimilarity between communities) to a distribution of expected β-diversity values generated from a null model that assumes purely stochastic assembly. Significant deviation from the null expectation indicates the influence of deterministic processes [10] [7] [8].

- Neutral Community Model (NCM): This model predicts species occurrence and abundance based on dispersal limitation and ecological drift. The fit of the NCM to observed data indicates the portion of community assembly that can be explained by these neutral, stochastic processes [8].

- Phylogenetic-Based Approaches: Methods like the β-Nearest Taxon Index (βNTI) and Raup-Crick metric use phylogenetic information to disentangle processes. |βNTI| > 2 indicates phylogenetic turnover significantly different from chance, suggesting deterministic selection (homogeneous if βNTI < -2, variable if βNTI > +2). When |βNTI| < 2, stochastic processes are inferred, and the Raup-Crick metric can further distinguish between homogenizing dispersal and dispersal limitation [10] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Community Assembly Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| 0.22 µm Pore Size Filters | Concentration of microbial biomass from water samples onto a solid surface for subsequent DNA extraction. | Used for filtering 800-1000 ml of lake water [7]. |

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Preserves RNA and DNA integrity in biological samples immediately after collection, preventing degradation during transport and storage. | Filters were stored in RNAlater at -20°C [7]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Standardized protocols for high-throughput lysis of microbial cells and purification of total genomic DNA from complex samples (soil, water, biofilms). | Manufacturer protocols were followed for DNA extraction [12]. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | Amplification of specific hypervariable regions (e.g., V4) of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene for high-throughput sequencing and taxonomic profiling. | Primers targeting the V4 region were used for amplicon sequencing [12]. |

| Illumina Sequencing Platform | Next-generation sequencing technology that generates millions of paired-end reads for deep characterization of microbial community composition. | Illumina MiSeq/Novaseq platforms were used [12] [8]. |

| HOBO Pendant Data Logger | Continuous in-situ monitoring of environmental parameters such as temperature and light intensity throughout an experiment. | Deployed at different depths to monitor conditions during a succession experiment [12]. |

| Neophytadiene | Neophytadiene (CAS 504-96-1)|Research Compound | High-purity Neophytadiene, a diterpene with anti-inflammatory, neuropharmacological, and cardioprotective research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Totaradiol | Totaradiol|CAS 3772-56-3|High-Purity Reference Standard | High-purity Totaradiol (C20H30O2) for laboratory research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

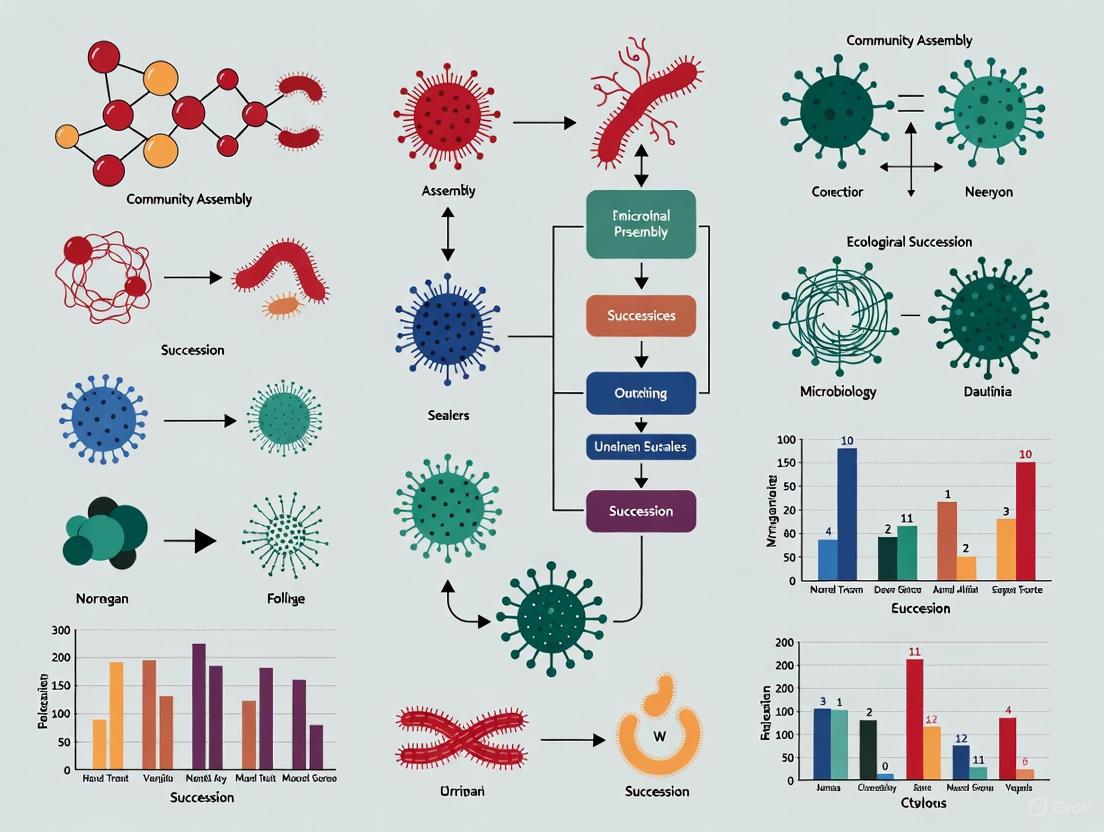

Conceptual Synthesis and Visual Framework

The interplay between deterministic and stochastic processes can be conceptualized as a continuum, where the position of a community is influenced by specific contextual filters. The following diagram integrates the key findings from recent research into a unified framework for predicting process dominance.

The blueprint of nature is not exclusively deterministic nor stochastic; it is a complex and dynamic interplay of both. The evidence is clear: the balance between these processes is context-dependent, varying with environmental conditions (e.g., trophic state, pollution), temporal scale, and the ecological traits of the organisms themselves. For researchers and drug development professionals, this nuanced understanding is critical. It suggests that manipulating a microbiome, whether in the human gut or a polluted river, requires a dual strategy: modifying the environmental conditions to impose deterministic selection while also accounting for the inherent stochasticity of rare taxa and the profound influence of time scales. Future research, leveraging the standardized methodologies and reagents outlined herein, will continue to refine our predictive models, ultimately enhancing our ability to manage and restore microbial ecosystems for human and environmental health.

The assembly of microbial communities is a central focus in microbial ecology, driven by the need to predict and manage ecosystems ranging from the human gut to environmental bioremediation sites. Within this framework, niche-based theory provides a deterministic perspective, asserting that community composition is shaped by non-random processes. Two of the most critical mechanisms within this paradigm are environmental filtering and resource competition. Environmental filtering acts as a selective force, allowing only species with traits suited to the prevailing abiotic and biotic conditions to establish and persist. Following this initial filtering, resource competition further structures the community by determining which species can coexist based on their ability to exploit limited nutritional resources. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to provide an in-depth technical guide on the roles of these two processes, detailing quantitative assessment methods, experimental protocols, and their implications for fields such as pharmaceutical development and ecosystem restoration.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

The Niche-Based Perspective in Community Ecology

Niche-based theory posits that community assembly is primarily deterministic, governed by environmental conditions and biological interactions. This contrasts with neutral theory, which emphasizes stochasticity and ecological equivalence among species. The modern synthesis acknowledges that both deterministic and stochastic processes operate simultaneously, but their relative importance varies across ecosystems and contexts. The conceptual framework of community assembly has been unified into four high-level processes: selection (deterministic processes), dispersal, diversification, and drift (stochastic processes). In this framework, environmental filtering and resource competition are key components of "selection" [15].

Environmental Filtering: The Abiotic Gatekeeper

Environmental filtering refers to the process by which abiotic factors—such as pH, temperature, moisture, salinity, and nutrient availability—prevent species lacking appropriate traits from establishing in a particular habitat. It sets the initial template upon which biological interactions act. For instance, in reclaimed mine soils, factors like soil organic matter (SOM), total nitrogen (TN), and pH were found to directly shape the succession of microbial communities by filtering for taxa capable of surviving in the prevailing conditions [16]. Similarly, in aquatic systems, salinity and total suspended solids have been identified as critical environmental filters that explain a significant portion of microbial community variation [17].

Resource Competition: The Biotic Sculptor

Once species pass the initial environmental filter, resource competition further structures the community. This occurs when multiple species require the same limited resources, such as nutrients, space, or light. The outcomes are governed by species' competitive abilities and niche differences. Mathematical models reveal that for an invading strain to successfully establish in a community, it must have access to resources not fully exploited by residents—a concept known as "private nutrients" [18]. Furthermore, the principle of competitive exclusion dictates that species with identical niche requirements cannot coexist indefinitely. However, coexistence becomes possible through niche differentiation, where species differentially utilize resources, or through trade-offs in competitive abilities [18].

Quantitative Evidence from Diverse Ecosystems

The relative importance and combined effects of environmental filtering and resource competition have been quantified across diverse microbial habitats. The table below summarizes key findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence of Environmental Filtering and Resource Competition Across Ecosystems

| Ecosystem | Key Environmental Filters Identified | Impact on Community Structure | Role of Resource Competition | Quantitative Measurement Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reclaimed Farmland (Coal Mining) [16] | Soil organic matter (SOM), total nitrogen (TN), available phosphorus (AP), pH | 2.1-fold increase in SOM led to significant shifts in bacterial and fungal composition; deterministic processes (heterogeneous selection) dominated bacterial assembly. | Increased network complexity and functional potential (chemoheterotrophy, nitrification) over time. | Null model analysis of β-nearest taxon index (βNTI); partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM). |

| River-Lake Continuum [17] | Salinity, total suspended solids (TSS) | Pure environmental factors explained 13.7% of community variation; pure spatial factors 5.6%. | Co-occurrence network analysis revealed more complex correlations in the lake, indicating stronger species interactions. | Variation partitioning analysis (VPA); co-occurrence network topology. |

| Black-Odor Water Bodies [8] | Total organic carbon (TOC), ammonia nitrogen (NHâ‚„âº-N), dissolved oxygen (DO) | Microbial assembly shifted from stochastic to deterministic processes (up to 88% stochasticity) as blackening progressed. | Ecological niche differentiation driven by these factors determined the rate of the blackening process. | Null model analysis (βNTI & RC metrics); SourceTracker. |

| Grassland Soil (Experimental Warming) [15] | Soil temperature, moisture, drought | Homogeneous selection accounted for 38% of assembly processes, primarily imposed on Bacillales. | Warming enhanced homogeneous selection, correlated with drought and plant productivity. | iCAMP (Phylogenetic bin-based null model analysis). |

Methodologies for Disentangling Assembly Processes

Analytical Frameworks: Null Models and Phylogenetic Metrics

A critical advancement in microbial ecology has been the development of quantitative frameworks to disentangle the relative influences of deterministic and stochastic processes. Key analytical approaches include:

- Phylogenetic Bin-Based Null Model Analysis (iCAMP): This robust framework quantifies the relative importance of different assembly processes, including homogeneous and heterogeneous selection (deterministic), and dispersal limitation, homogenizing dispersal, and drift (stochastic). iCAMP performs better than whole-community-based approaches by grouping taxa into phylogenetic bins before analysis, achieving high accuracy (0.93–0.99) and precision (0.80–0.94) [15]. The workflow is detailed in the diagram below.

- Consumer-Resource Models: These mechanistic mathematical models explicitly simulate population dynamics based on resource uptake and conversion. They can predict the conditions for successful microbial invasion and displacement, showing that weak resource competition enables invasion, while strong interference competition (e.g., via antimicrobial production) enables displacement [18].

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

- Site Selection & Sampling: Establish a chronosequence of reclaimed farmlands in a coal mining area (e.g., 0, 1, 6, and 10 years post-reclamation). Include nearby undisturbed farmland as a control. Collect soil samples (0-15 cm depth) using a five-point sampling method within replicated plots.

- Soil Physicochemical Analysis: Air-dry and sieve soils. Analyze:

- pH: Using a glass electrode with a water-soil ratio of 2.5:1.

- SOM: Via the potassium dichromate-external heating method.

- TN: By Kjeldahl determination.

- AP: By colorimetric method after extraction with 0.5 M NaHCO₃.

- AK: Using a flame spectrophotometer.

- Enzyme Activities (BG, NAG, LAP): Based on the hydrolysis of MUB-conjugated substrates to produce fluorescent MUB.

- Microbial Community Profiling:

- DNA Extraction: Use a commercial kit (e.g., E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit).

- Amplification & Sequencing: Amplify the bacterial 16S rRNA gene (V3-V4 region with primers 338F/806R) and fungal ITS region (with primers ITS1F/ITS1R). Sequence on an Illumina HiSeq platform.

- Bioinformatics: Process raw sequences in QIIME2. Cluster reads into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at 97% similarity using Usearch.

- Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate alpha-diversity indices (Shannon, Chao1) in QIIME2.

- Perform Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) using the

veganpackage in R. - Construct co-occurrence networks and identify keystone taxa.

- Perform null model analysis to infer community assembly processes.

- Strain Engineering:

- Create a resource competition mutant (e.g., E. coli ∆srlAEB that cannot metabolize sorbitol) to manipulate niche overlap.

- Equip an invading strain with an interference competition mechanism (e.g., a plasmid-borne colicin E2 gene).

- Invasion Assay:

- Pre-culture the resident strain(s) in an appropriate medium to establish a stable community.

- Introduce the invading strain at a low starting density (e.g., 1:1000 invader-to-resident ratio).

- Culture under well-mixed conditions (batch or chemostat) with a defined medium. The medium should contain a "private nutrient" (e.g., sorbitol) that only the invader can use, and/or shared nutrients.

- Monitoring and Analysis:

- Monitor population densities of resident and invading strains over time using flow cytometry or selective plating.

- Fit data to consumer-resource models to parameterize growth and competition rates.

- Validation: Confirm that invasion succeeds only when the invader has a private nutrient. Confirm that displacement (outcompetition of the resident) occurs when successful invasion is coupled with strong interference competition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Studying Niche-Based Processes

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| MUB-conjugated Substrates | Fluorogenic compounds used to measure extracellular enzyme activities. | Quantifying β-glucosidase (BG), N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase (NAG), and leucine aminopeptidase (LAP) activity in soils, indicative of nutrient cycling potential [16]. |

| Primers 338F/806R | PCR primers targeting the V3-V4 hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. | Profiling bacterial community composition and diversity in environmental samples via high-throughput sequencing [16]. |

| Primers ITS1F/ITS1R | PCR primers targeting the fungal Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region. | Profiling fungal community composition and diversity in environmental samples [16]. |

| E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit | Optimized protocol for extracting high-quality metagenomic DNA from soil samples. | Overcoming humic acid inhibition to obtain pure DNA for downstream PCR and sequencing [16]. |

| Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs) | Defined mixtures of microbial strains. | Testing specific hypotheses about resource competition and invasion dynamics in a controlled, gnotobiotic system [18]. |

| Colicin E2 Plasmid | A well-characterized bacteriocin used as a tool for interference competition. | Genetically engineering an E. coli strain to study the role of toxin-mediated competition in strain displacement [18]. |

| Paeonilactone C | Paeonilactone C | High-Purity Reference Standard | Paeonilactone C, a bioactive monoterpene glucoside. Explore its research applications in inflammation & neuroscience. For Research Use Only. |

| Paeonilactone A | Paeonilactone A | High Purity Reference Standard | Paeonilactone A for research. Explore its anti-inflammatory & neuroprotective applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

Implications and Future Directions

Understanding the roles of environmental filtering and resource competition is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound practical implications. In drug development, there is growing recognition of bidirectional drug-microbiome interactions. Hundreds of human-targeted drugs alter the gut microbiome composition (a form of environmental filtering), while the microbiome can metabolize drugs, altering their pharmacokinetics and efficacy [19] [20]. Incorporating these principles into pre-clinical screening could lead to more predictable drug outcomes and personalized dosing regimens. In ecosystem restoration, as demonstrated in reclaimed mine soils, managing environmental filters (e.g., by adding organic matter) can steer microbial succession toward a healthy, functional state that supports plant growth and ecosystem stability [16].

Future research will be bolstered by the integration of more sophisticated mathematical models, such as those incorporating game theory and stable marriage models to understand competition and coexistence [21], and a greater focus on strain-level dynamics, which represent a critical ecological unit where much of the competition actually occurs [22] [18]. Furthermore, combining observational studies with highly controlled, trackable experiments will be essential for moving beyond correlation to establish causal mechanisms in microbial community assembly [22].

The Impact of Disturbance Gradients on Successional Trajectories

Understanding the mechanisms that govern ecological succession is fundamental to restoration ecology. This review examines the impact of disturbance gradients on the successional trajectories of soil microbial communities, with a specific focus on the divergent assembly processes of abundant and rare taxa. Drawing on a 53-year restoration chronosequence from the Tengger Desert, we synthesize evidence that disturbance intensity and duration shape microbial community structure and function through distinct ecological processes. The assembly of abundant taxa is primarily governed by stochastic processes, while deterministic selection strongly influences rare taxa. These divergent pathways underpin a dual mechanism through which microbial communities drive ecosystem multifunctionality, offering a refined framework for predicting restoration outcomes and designing targeted interventions.

Ecological succession, the process by which the structure of a biological community evolves over time, is fundamentally reshaped by disturbance gradients. In the context of global desertification, understanding the successional dynamics of soil microbial communities—the unseen engines of ecosystem functioning—has never been more critical [23]. Disturbance gradients, ranging from acute physical disruption to chronic environmental stress, create heterogeneous templates upon which ecological communities assemble. For microbial communities, these gradients filter species based on their ecological strategies, ultimately determining the trajectory and pace of ecosystem recovery.

Theoretical frameworks in community ecology have historically emphasized the assembly of macrobial communities, but recent advances reveal that microbial life follows distinct principles. A pivotal insight is the unbalanced distribution of microbial taxa, where a small number of abundant taxa coexist with a long tail of rare taxa [23]. These groups exhibit divergent ecological characteristics: abundant taxa often display broad niche breadth and high metabolic versatility, while rare taxa possess specific habitat preferences and narrow niche breadth but contribute significantly to functional diversity and potential [23]. Understanding how disturbance gradients filter these distinct ecological groups is essential for predicting successional trajectories.

This technical guide synthesizes recent advances from long-term restoration chronosequences to build a mechanistic framework linking disturbance gradients to microbial succession. By integrating concepts of community assembly, niche theory, and ecosystem multifunctionality, we provide researchers with both the theoretical foundation and practical methodologies for quantifying and interpreting these complex ecological patterns. Our focus on microbial communities within the broader thesis context of community assembly and succession research highlights the micro-scale processes that ultimately govern macro-scale restoration outcomes.

Theoretical Framework: Disturbance and Microbial Community Assembly

Defining Disturbance Gradients in Microbial Systems

In microbial ecology, disturbance gradients encompass any relatively discrete event in time that disrupts community structure, substrate availability, or the physical environment. Key dimensions of microbial disturbance include:

- Intensity: The magnitude of physical or chemical disruption (e.g., carbon source alteration, pH shift, moisture fluctuation)

- Frequency: The recurrence interval of disruptive events

- Duration: The temporal extent of the disturbance event

- Scale: The spatial extent relative to microbial dispersal capabilities

These gradients act as environmental filters that selectively favor taxa with particular trait combinations, thereby shaping the successional trajectory from the onset of disturbance through to community recovery.

Ecological Processes Governing Assembly

Microbial community assembly is governed by the balance between deterministic (niche-based) and stochastic (neutral) processes:

- Deterministic Processes: Environmental filtering and biotic interactions that predictably shape community composition based on species traits. This includes variable selection, where environmental conditions differentially select for species across habitats.

- Stochastic Processes: Ecological drift, random birth-death events, and probabilistic dispersal that create unpredictable variation in community composition. This includes dispersal limitation, where geographic isolation limits microbial exchange.

The balance between these processes shifts along disturbance gradients, creating predictable successional dynamics. A null-modeling framework quantitatively partitions the relative influence of these processes by comparing observed community similarity patterns to those expected under random assembly [23].

The Abundant-Rare Taxon Paradigm

A foundational concept in contemporary microbial ecology is the recognition that abundant and rare subcommunities exhibit fundamentally different ecological characteristics and responses to disturbance:

Table: Characteristics of Microbial Subcommunities Along Disturbance Gradients

| Characteristic | Abundant Taxa | Intermediate Taxa | Rare Taxa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Abundance | High (55.54% of sequences) | Moderate (33.59% of sequences) | Low (10.87% of sequences) |

| Niche Breadth | Broad | Intermediate | Narrow |

| Occupancy Frequency | 53.24% found in >50% of samples | Intermediate distribution | 70.92% appear in only one sample |

| Response to Disturbance | More resistant, rapid recovery | Variable response | More sensitive, slow recovery |

| Phylogenetic Diversity | Lower (18 phyla) | Intermediate (30 phyla) | Higher (56 phyla) |

This paradigm reveals that successional trajectories must be understood as the composite of multiple subcommunity trajectories, each responding uniquely to disturbance gradients through distinct assembly mechanisms.

Quantitative Synthesis: Microbial Succession Along Restoration Chronosequences

Data from a 53-year restoration chronosequence following straw checkerboard barrier implementation in the Tengger Desert, China, provides unprecedented insight into microbial successional dynamics [23]. Analysis of 55 soil samples across 11 restoration stages revealed clear temporal patterns in microbial diversity and composition.

Temporal Diversity Dynamics

Table: Richness Changes Along the Restoration Chronosequence

| Restoration Phase | Abundant Taxa Richness | Intermediate Taxa Richness | Rare Taxa Richness | Dominant Phyla |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial (0-5 years) | Low, rapidly increasing | Low, rapidly increasing | Low, slowly increasing | Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria |

| Mid (5-15 years) | Reaching asymptotic stability | Reaching asymptotic stability | Linear increase | Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi |

| Late (>15 years) | Stable at elevated levels | Stable at elevated levels | Continued linear increase | Increased phylogenetic representation |

The analysis revealed markedly different temporal patterns: abundant and intermediate taxa richness increased rapidly, reaching asymptotic stability after approximately 15 years, while rare taxa richness showed a sustained, linear increase throughout the 53-year sequence [23]. This suggests that rare taxa accumulate more slowly but continuously throughout succession, potentially contributing to the long-term functional resilience of the ecosystem.

Community Assembly Processes

Quantitative null modeling revealed fundamentally different assembly processes governing the abundant and rare subcommunities:

- Abundant Subcommunities: Primarily governed by stochastic processes (69.3%), especially dispersal limitation (45.19%), with variable selection exerting a moderate influence (26.6%) [23]

- Rare Subcommunities: Mainly structured by deterministic processes (73.53%), particularly variable selection [23]

- Intermediate Subcommunities: Showed an intermediate pattern, with deterministic processes dominating (70.37%) but with a significant stochastic component [23]

These findings demonstrate that disturbance gradients filter abundant and rare taxa through distinct mechanistic pathways, creating a successional dynamic where stochastic processes dominate the recovery of core community functions while deterministic processes shape the accumulation of rare diversity.

Compositional Turnover and Temporal Variability

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination and analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) based on Bray-Curtis distances revealed significant compositional differences across restoration durations for all subcommunities [23]. However, the temporal variability and turnover mechanisms differed substantially:

- Compositional Difference vs. Time Interval: Compositional differences in all subcommunities increased significantly with longer restoration duration intervals [23]

- Temporal Variability: Abundant subcommunities exhibited lower temporal variability compared to rare subcommunities [23]

- Turnover Mechanisms: β-diversity partitioning revealed that species replacement (turnover) rather than richness differences accounted for the majority of community composition variation across all subcommunities [23]

These patterns suggest that successional trajectories are driven primarily by species replacement rather than simple accumulation, with rare taxa contributing disproportionately to temporal β-diversity.

Methodological Framework: Experimental Protocols for Assessing Microbial Succession

Field Sampling Design Along Chronosequences

Establishing a robust sampling framework is essential for capturing successional dynamics along disturbance gradients:

- Site Selection: Identify restoration sites with documented implementation dates to create a space-for-time substitution chronosequence. The Tengger Desert study utilized 11 stages across a 53-year gradient [23]

- Sample Collection: Collect composite soil samples (e.g., 10-15 cores per plot) from consistent soil depths (typically 0-15 cm for microbial communities)

- Replication: Include sufficient biological replication (n=5 per time point in the Tengger Desert study) to account for spatial heterogeneity [23]

- Environmental Covariates: Measure key edaphic variables including pH, soil moisture, texture, organic carbon, total nitrogen, and available phosphorus

Molecular Analysis of Microbial Communities

Standardized molecular protocols ensure comparable data across studies:

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial soil DNA extraction kits with bead-beating for comprehensive cell lysis

- Marker Gene Amplification: Amplify the 16S rRNA gene (bacteria/archaea) or ITS region (fungi) using primers with sample-specific barcodes for multiplexing

- Sequencing: Utilize high-throughput sequencing platforms (Illumina MiSeq/HiSeq) with sufficient depth (>20,000 sequences per sample after quality control)

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Process raw sequences through quality filtering, denoising, and chimera removal (DADA2, USEARCH, QIIME2)

- Cluster sequences into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) or operational taxonomic units (OTUs)

- Taxonomic classification using reference databases (SILVA, Greengenes, UNITE)

Defining Abundant and Rare Taxa

Operational definitions of abundance categories enable standardized comparisons:

- Abundance Thresholds: Apply multivariate cutoff level analysis (MultiCoLA) to define subcommunities based on relative abundance distributions [23]

- Typical Thresholds:

- Abundant taxa: >0.1% relative abundance in the overall dataset

- Intermediate taxa: 0.01%-0.1% relative abundance

- Rare taxa: <0.01% relative abundance

- Occupancy Considerations: Consider incorporating occupancy frequency (number of samples where a taxon appears) to distinguish between consistently rare and transiently abundant taxa

Quantifying Assembly Processes

Null model analysis provides a quantitative framework for inferring ecological processes:

- Null Model Construction: Create randomized communities using appropriate null models (e.g., swap algorithms that maintain row and column sums)

- Beta-Diversity Metrics: Calculate Bray-Curtis dissimilarities for both observed and null communities

- Process Inference:

- Compare observed β-diversity to null expectation using the β-nearest taxon index (βNTI) and Raup-Crick metrics

- |βNTI| > 1.96 indicates homogeneous or variable selection (deterministic processes)

- |βNTI| < 1.96 with RCbray > 0.95 indicates dispersal limitation

- |βNTI| < 1.96 with RCbray < -0.95 indicates homogenizing dispersal

Ecosystem Function Assessment

Comprehensive ecosystem function assessment captures multifunctionality:

- Function Selection: Measure processes representing key ecosystem services (e.g., carbon cycling, nutrient transformation, decomposition)

- Standardized Assays:

- Soil enzyme activities (hydrolases, oxidases)

- Organic matter decomposition rates (litter bags)

- Nutrient transformation potentials (incubation assays)

- Microbial metabolic profiles (Biolog EcoPlates)

- Multifunctionality Index: Calculate a composite index based on the average of standardized individual functions, or apply threshold-based approaches

Visualizing Successional Trajectories and Assembly Processes

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz with the specified color palette, illustrate key concepts and relationships in disturbance-driven microbial succession.

Diagram 1: Conceptual framework of disturbance effects on microbial assembly and function.

Diagram 2: Successional timeline showing divergent trajectories of microbial subcommunities.

Diagram 3: Experimental workflow for analyzing microbial succession.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Succession Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Field Sampling | Soil corers, sterile containers, coolers, GPS units, environmental sensors | Standardized collection of soil samples and associated metadata |

| DNA Analysis | Commercial soil DNA extraction kits, PCR reagents, barcoded primers, quality control equipment (Nanodrop, Qubit) | High-quality genetic material extraction and preparation for sequencing |

| Sequencing | 16S rRNA gene primers (515F/806R), ITS primers, sequencing kits (Illumina), library preparation reagents | Targeted amplification and sequencing of microbial marker genes |

| Bioinformatics | QIIME2, DADA2, USEARCH, R packages (phyloseq, vegan), SILVA/Green genes databases | Processing raw sequence data into analyzed community data |

| Statistical Analysis | R or Python with specialized packages (vegan, picante, nlme), null model algorithms | Quantifying diversity patterns, assembly processes, and temporal dynamics |

| Pentosidine | Pentosidine | Advanced Glycation End-Product (AGE) | High-purity Pentosidine for research into AGEs, diabetes & aging. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Kaerophyllin | Kaerophyllin Reference Standard|For Research Use | High-purity Kaerophyllin for laboratory research. Explore its applications in phytochemical and pharmacological studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The examination of microbial successional trajectories along disturbance gradients reveals a sophisticated ecological narrative where abundant and rare taxa follow divergent paths through distinct assembly mechanisms. This refined understanding moves beyond monolithic community perspectives to recognize the functional complementarity between microbial groups with different abundance strategies.

The practical implications for restoration ecology are substantial. The recognition that abundant taxa—governed primarily by stochastic processes—drive coordinated functions suggests that initial restoration efforts should focus on creating conditions that facilitate stochastic establishment and growth. Conversely, the finding that rare taxa—shaped mainly by deterministic selection—contribute independent functions indicates that long-term restoration strategies should emphasize environmental heterogeneity to support diverse specialized niches.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies that track microbial succession in real time rather than through space-for-time substitutions, integrate multi-omic approaches to link taxonomic succession with functional gene dynamics, and develop manipulation experiments that explicitly test the role of identified processes. Such advances will further refine our ability to predict and guide ecological recovery in an era of unprecedented environmental change.

The assembly of ecological communities, a process dictating the structure and function of every microbiome, is governed by the interplay of deterministic and stochastic forces. Among deterministic processes, the biotic interactions of competition, cooperation, and facilitation are critical drivers of microbial community composition, diversity, and succession [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these interactions is paramount, as they underpin host health, ecosystem stability, and the functional output of microbial systems. While environmental filtering selects for organisms capable of surviving abiotic conditions, biotic interactions act as a subsequent filter, determining which species can persist together [25]. Recent research has increasingly shown that biotic interactions can be a more significant force than environmental factors or geographic distance in shaping microbial community patterns [24]. This technical guide synthesizes current theoretical frameworks, quantitative findings, and experimental methodologies for dissecting the roles of competition and cooperation in microbial community assembly, providing a foundational resource for advanced research in microbial ecology and therapeutic development.

Theoretical Foundations of Biotic Interactions

Biotic interactions are fundamental ecological forces that can be categorized based on their effects on the interacting partners.

Competition (-/- interaction): An interaction between species that vies for the same limited resources, such as nutrients or space. This leads to a reduction in the growth, survival, or reproduction of at least one of the species involved. In microbial communities, competition primarily occurs through exploitative competition for shared carbon sources and other nutrients [26].

Cooperation & Facilitation (+/+ or +/0 interaction): Cooperation (mutualism) is an interaction where all participating species derive a benefit. Facilitation, often used in a broader sense, occurs when one species modifies the environment in a way that benefits another, which can include by-product sharing without a direct cost to the facilitator. A quintessential example of microbial facilitation is cross-feeding, where metabolic by-products (e.g., leaked metabolites) from one species serve as essential resources or "public goods" for others [26]. This creates positive feedback loops that enhance community cohesion.

The balance between these opposing forces—competitive exclusion versus cooperative integration—is a primary determinant of community trajectories and properties. Theoretical models and experimental data suggest that cooperative and facilitative interactions can increase community speciation (diversity), robustness (resistance to invasion), and functional efficiency (resource use) [26].

Quantitative Dynamics and Community Outcomes

The relative strengths of competitive and cooperative interactions have measurable and divergent impacts on community-level properties. These impacts can be quantified through both modeling and empirical observation, providing a predictive framework for understanding community assembly outcomes.

Table 1: Community-Level Outcomes of Dominant Interaction Types

| Interaction Type | Impact on Species Richness | Impact on Community Cohesion/ Robustness | Impact on Resource Use Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Competition | Decreases | Increases resistance to invasion but reduces functional stability | High for primary resources, but may leave by-products underexploited |

| High Cooperation/ Facilitation | Increases | Increases resistance to invasion and overall stability | More complete depletion of diverse resources, including metabolic by-products [26] |

The quantitative dynamics of these interactions are further elucidated by community coalescence events, where two or more independent communities merge. Simulations using consumer-resource models with cross-feeding reveal that:

- In a coalescence event, the parent community with a lower degree of competition and a higher degree of cooperation contributes a disproportionately larger fraction of species to the new, combined community [26].

- This advantage is attributed to the superior ability of cooperative communities to deplete resources and resist invasions. Consequently, when a community is subjected to repeated coalescence events, it evolves over time to become less competitive, more cooperative, more speciose, more robust, and more efficient in its resource use [26].

Table 2: Relative Contribution of Different Processes to Bacterial Community Assembly

| Assembly Process | Category | Reported Contribution to Community Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Biotic Interactions | Deterministic | Dominant driver; contributes more than environmental factors and geographic distance in arid soil systems [24] |

| Environmental Filtering | Deterministic | Significant, but secondary to biotic interactions in some arid systems; salinity is a key factor for prokaryotes [24] |

| Dispersal Limitation | Stochastic | A contributing factor, but its influence is weaker than that of biotic interactions and environmental selection in studied arid ecosystems [24] |

Furthermore, the influence of biotic interactions varies between microbial domains. Research on soil prokaryotic and fungal communities has demonstrated that while both are shaped by the interplay of deterministic and stochastic processes, prokaryotic community assembly is more deterministic and more strongly influenced by biotic interactions and environmental variables. In contrast, fungal community assembly is more influenced by stochastic processes [24].

Methodologies for Disentangling Biotic Interactions

A critical challenge in microbial ecology is methodologically separating the effects of biotic interactions from other assembly processes like environmental filtering and dispersal limitation. Several advanced techniques have been developed to address this.

Experimental Separation of Filters

A direct approach to disentangling abiotic and biotic filters involves seed/transplant experiments with a gap treatment [25].

- Protocol: Candidate species (as seeds or pre-grown transplants) are introduced into two types of experimental plots within the target environment: competition-free gaps (e.g., created by physical removal of vegetation) and intact vegetation.

- Analysis: Successful establishment in the gap indicates that the abiotic environment is suitable. A significantly higher survival rate in gaps compared to intact vegetation indicates exclusion by biotic competition in the latter. This method has revealed that many species absent in a community under natural conditions can, in fact, survive the abiotic conditions but are excluded by competition [25].

Computational Inference from Sequence Data

For complex microbial communities where manual experimentation is infeasible, computational methods can infer putative biotic interactions from amplicon sequencing data.

The QCMI (Quantifying Community-level Microbial Interactions) Workflow [27]:

- Network Construction: Infer co-occurrence networks using correlation (e.g., Pearson, Spearman) or covariance-based methods (e.g., Spiec-Easi) from an Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) table.

- Link Assignment: Subject significant associations to sequential link tests. An association is classified as driven by dispersal limitation if taxa abundances correlate with geographic distance. If not, it is tested for correlation with environmental dissimilarity (environmental selection).

- Biotic Association Identification: Associations that cannot be explained by space or environment are classified as putative biotic interactions [27].

Leveraging Eukaryotic Community Proxies: A novel approach to quantify inter-domain interactions uses the characteristics of microbial eukaryotic communities (from metabarcoding or flow cytometry) as proxies for their interactions with bacteria. Statistical modeling can then partition the variation in bacterial diversity explained by different interaction types, such as parasitism (27%), fungi-bacterial competition (32%), and trophic structure/bacterivory (13%) [28].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for inferring biotic interactions from observational data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, tools, and computational packages essential for research into biotic interactions and community assembly.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Studying Biotic Interactions

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| General Consumer-Resource Model | Mathematical Model | A computational framework for simulating community dynamics, including competition for resources and cooperative cross-feeding via leaked metabolites [26]. |

| Spiec-Easi | Computational Package | Infers reliable microbial ecological networks from amplicon data using sparse inverse covariance estimation, helping to avoid detection of indirect associations [27]. |

qcmi R Package |

Computational Workflow | A structured workflow to identify and quantify community-level putative biotic associations by filtering out abiotic-driven co-occurrences [27]. |

| Beals Index | Statistical Index | Predicts the probability of species co-occurrence based on community data; used as a proxy for habitat suitability and to assess experimental establishment success [25]. |

| Gap-Plot Experiment | Experimental Design | A field-based method to create competition-free microhabitats, allowing direct testing of abiotic environmental suitability versus biotic competition [25]. |

| Benzydamine N-oxide | Benzydamine N-oxide | High-Purity Research Grade | Benzydamine N-oxide is a key metabolite for pharmacological research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Dihydroferulic Acid | 3-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)propionic Acid | High-purity 3-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)propionic acid for research. Explore its applications in biochemistry and inflammation studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |