Mastering CLSI EP12: A Comprehensive Guide to Evaluating Qualitative Binary Test Performance

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for evaluating qualitative, binary output examinations based on the CLSI EP12 protocol.

Mastering CLSI EP12: A Comprehensive Guide to Evaluating Qualitative Binary Test Performance

Abstract

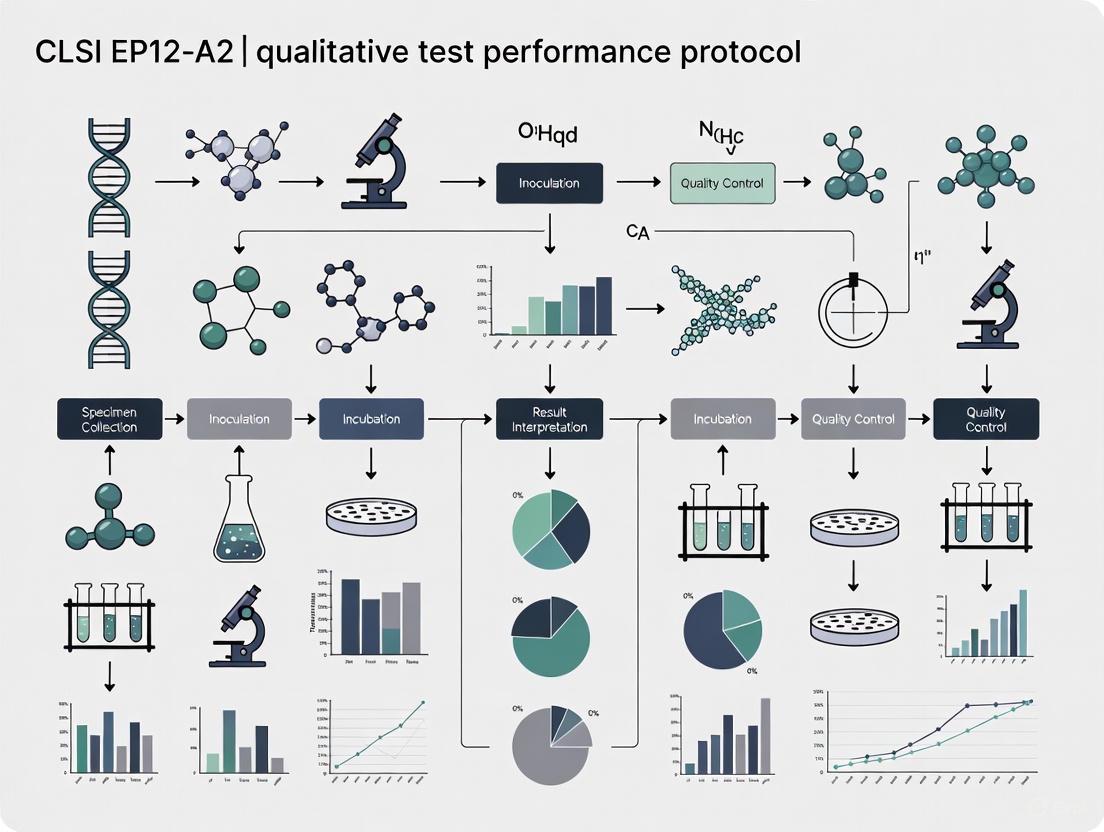

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for evaluating qualitative, binary output examinations based on the CLSI EP12 protocol. Covering foundational principles, methodological protocols, troubleshooting strategies, and validation techniques, it addresses the transition from the established EP12-A2 guideline to the current 3rd edition. The content synthesizes CLSI standards with practical applications, including precision estimation, clinical agreement studies, interference testing, and the assessment of modern assay types, to ensure reliable performance verification in both development and laboratory settings.

Understanding CLSI EP12: The Foundation of Qualitative Test Evaluation

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guideline EP12 - Evaluation of Qualitative, Binary Output Examination Performance provides a standardized framework for evaluating the performance of qualitative diagnostic tests that produce binary outcomes [1]. This protocol establishes rigorous methodologies for assessing key performance parameters of tests that yield simple "yes/no" results, such as positive/negative, present/absent, or reactive/nonreactive [2]. The guideline serves as a critical resource for ensuring the reliability and accuracy of qualitative tests across the medical laboratory landscape, from simple rapid tests to complex molecular assays.

The third edition of EP12, published in March 2023, represents a significant evolution from the previous EP12-A2 version published in 2008 [1] [2]. This updated standard has been officially recognized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in satisfying regulatory requirements for medical devices, underscoring its importance in the diagnostic regulatory landscape [3]. The guideline is designed for both manufacturers developing commercial in vitro diagnostics (IVDs) and medical laboratories creating laboratory-developed tests (LDTs), providing protocols applicable throughout the test life cycle [1].

Scope and Applications of EP12

CLSI EP12 provides comprehensive guidance for performance evaluation during the Establishment and Implementation Stages of the Test Life Phases Model of examinations [1]. The standard specifically characterizes a target condition with only two possible outputs, making it applicable to a wide range of qualitative tests used in clinical practice and research settings.

The scope of EP12 covers several critical areas essential for proper test evaluation. For test developers, including both commercial manufacturers and laboratory developers, EP12 offers product design guidance and performance evaluation protocols [1]. For end-users in medical laboratories, the guideline provides methodologies to verify examination performance in their specific testing environments, ensuring that performance claims are met in practice [1]. The standard also addresses multiple performance characteristics including imprecision, clinical performance (sensitivity and specificity), stability, and interference testing [1].

Notably, tests that fall outside EP12's scope include those providing outputs with more than two possible categories in an unordered set or those reporting ordinal categories [1]. The guideline's applications span diverse testing platforms, from simple home tests for detecting pathogens like the COVID-19 virus to complex next-generation sequencing assays for diagnosing specific cancers [2].

Table: Key Applications of CLSI EP12 Across Test Types

| Test Category | Examples | EP12 Application Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Simple Rapid Tests | Home tests (e.g., COVID-19 antigen tests) | Clinical performance verification, imprecision assessment |

| Molecular Assays | PCR-based detection methods | Lower limit of detection determination, precision evaluation |

| Complex Sequencing | Next-generation sequencing for cancer diagnosis | Precision evaluation, clinical performance validation |

| Laboratory-Developed Tests | Laboratory-developed binary examinations | Complete performance validation, stability assessment |

Core Components and Evaluation Framework

Precision and Imprecision Assessment

EP12 provides detailed methodologies for evaluating the precision of qualitative, binary output examinations, with a particular focus on estimating C5 and C95 values [1]. These statistical measures represent the analyte concentrations at which the examination produces positive results 5% and 95% of the time, respectively, effectively defining the concentration range where test results transition from consistently negative to consistently positive. Determining these transition points is crucial for understanding the reliability of a qualitative test across different analyte concentrations.

The guideline includes specific protocols for assessing observer precision, which is particularly relevant for tests involving subjective interpretation of results [2]. For advanced technologies like next-generation sequencing, EP12 provides specialized approaches for precision evaluation that account for the unique characteristics of these platforms [2]. The precision assessment framework helps developers and laboratories identify and quantify the random variation inherent in qualitative testing processes, enabling them to establish the reproducibility and repeatability of their examinations under defined conditions.

Clinical Performance Evaluation

The evaluation of clinical performance represents a cornerstone of the EP12 framework, focusing primarily on the assessment of sensitivity and specificity [1]. These fundamental metrics measure a test's ability to correctly identify true positives (sensitivity) and true negatives (specificity) when compared to an appropriate reference standard. The guideline provides standardized protocols for designing studies that generate reliable and statistically valid estimates of these parameters, ensuring that performance claims are substantiated by robust evidence.

EP12 emphasizes the importance of examination agreement in method comparison studies, providing methodologies for evaluating how well a new test aligns with established reference methods or clinical outcomes [1]. The clinical performance assessment protocols are designed to be flexible enough to accommodate different types of binary examinations while maintaining methodological rigor, whether the test is intended for diagnostic, screening, or monitoring purposes.

Stability and Interference Testing

The third edition of EP12 introduces expanded guidance on reagent stability testing, addressing the need to establish how long reagents maintain their performance characteristics under specified storage conditions [1] [2]. This component is critical for both manufacturers establishing shelf-life claims and laboratories verifying stability upon receipt of reagents. The standard provides systematic approaches for evaluating stability over time, helping to ensure that test performance remains consistent throughout a product's claimed shelf life.

The guideline also comprehensively addresses interference testing, providing methodologies to identify and quantify the effects of various interfering substances that may affect test performance [1]. These protocols help developers and laboratories understand how common interferents such as hemolysis, lipemia, icterus, or specific medications might impact test results, enabling them to establish limitations for the test or provide appropriate warnings to users.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Precision Study Design

EP12 outlines structured approaches for designing precision studies that generate meaningful, statistically valid data for qualitative tests. The precision evaluation protocol involves testing multiple replicates of samples with analyte concentrations spanning the anticipated transition zone between negative and positive results. This approach allows for comprehensive characterization of a test's imprecision profile across the clinically relevant concentration range.

A typical precision study following EP12 recommendations would include several key elements. Sample selection should include concentrations near the expected C5 and C95 points to adequately characterize the transition zone. Replication strategies involve testing multiple replicates (typically 60 or more as recommended in previous editions) across multiple runs, days, and operators to capture different sources of variation. For observer precision studies, the protocol incorporates multiple readers interpreting the same set of samples to assess inter-observer variability, which is particularly important for tests with subjective interpretation components [2].

Table: Key Components of EP12 Precision Evaluation

| Study Element | Protocol Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Concentration Levels | Multiple levels spanning negative, transition, and positive ranges | Characterize performance across analytical measurement range |

| Replication Scheme | Multiple replicates across runs, days, operators | Capture different sources of variation |

| Statistical Analysis | C5 and C95 estimation with confidence intervals | Quantify transition zone with precision |

| Observer Variability | Multiple readers, blinded interpretation | Assess subjectivity in result interpretation |

Clinical Performance Study Methodology

The clinical performance evaluation protocol in EP12 provides a rigorous framework for establishing the diagnostic accuracy of qualitative tests through method comparison studies. The fundamental approach involves testing a set of clinical samples with both the test method and a reference method, then comparing the results to calculate performance metrics including sensitivity, specificity, and overall agreement.

The recommended methodology encompasses several critical design considerations. Sample selection should include an appropriate mix of positive and negative samples reflecting the intended use population, with sample size calculations providing sufficient statistical power for reliability estimates. Reference method requirements specify that the comparator should be a well-established method with known performance characteristics, preferably a gold standard for the condition being detected. Blinding procedures ensure that operators performing the test method and reference method are blinded to each other's results to prevent interpretation bias. For tests with an internal continuous response, EP12 provides additional guidance on establishing appropriate cutoff values that optimize the balance between sensitivity and specificity [2].

Verification Protocols for Implementation

CLSI EP12 includes specific guidance for verification studies conducted by end-user laboratories to confirm that a test performs according to manufacturer claims or established specifications in their specific testing environment [1]. The companion document EP12IG - Verification of Performance of a Qualitative, Binary Output Examination Implementation Guide provides practical guidance for laboratories on conducting these verification studies [4].

The verification protocol focuses on confirming several key performance characteristics using a manageable number of samples. Precision verification typically involves testing negative, low-positive, and positive samples in replicates across multiple runs to confirm reproducible results. Clinical performance verification usually requires testing a panel of well-characterized samples to confirm stated sensitivity and specificity claims. Stability verification may involve testing reagents near their expiration date or under stressed conditions to confirm performance throughout the claimed shelf life. Interference verification often includes testing samples with and without potential interferents to confirm that common substances do not affect results.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of EP12 protocols requires specific research reagents and materials carefully selected to ensure comprehensive test evaluation. These reagents form the foundation of robust performance studies that generate reliable, reproducible data.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for EP12 Compliance Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in EP12 Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Characterized Clinical Samples | Positive samples with known concentrations, negative samples from healthy donors, borderline samples near cutoff | Serve as test materials for precision and clinical performance studies |

| Interference Substances | Hemolysed blood, lipid emulsions, bilirubin solutions, common medications | Evaluate test robustness against potential interferents |

| Stability Testing Materials | Reagents at different manufacturing dates, accelerated stability samples | Assess reagent stability over time and storage conditions |

| Reference Standard Materials | International standards, certified reference materials, well-characterized patient samples | Serve as comparator for method comparison studies |

| Quality Control Materials | Negative, low-positive, and high-positive control materials | Monitor assay performance throughout study duration |

Relationship with Other CLSI Standards

CLSI EP12 does not function in isolation but forms part of an interconnected ecosystem of standards that collectively support comprehensive test evaluation throughout the test life cycle. Understanding these relationships is essential for proper implementation of the guideline and for navigating the broader landscape of laboratory standards.

EP12 maintains a particularly important relationship with CLSI EP19 - A Framework for Using CLSI Documents to Evaluate Medical Laboratory Test Methods [1] [5]. EP19 provides the overarching Test Life Phases Model that defines the Establishment and Implementation stages for which EP12 provides specific guidance [2]. Laboratories are encouraged to use EP19 as a fundamental resource to identify relevant CLSI EP documents, including EP12, for verifying performance claims for both laboratory-developed tests and regulatory-cleared or approved test methods [5].

For laboratories implementing qualitative tests, CLSI offers EP12IG, a dedicated implementation guide that provides practical, step-by-step guidance for verifying the performance of qualitative, binary output examinations in routine laboratory practice [4]. This companion document helps laboratories apply the more comprehensive principles outlined in EP12 to their specific verification needs, outlining minimum procedures for assessing imprecision, clinical performance, stability, and interferences.

Regulatory Impact and Industry Significance

The recognition of CLSI EP12 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a consensus standard for medical devices significantly enhances its importance in the diagnostic industry [3]. This formal recognition means that manufacturers can use EP12 protocols to generate data that supports premarket submissions for FDA clearance or approval of qualitative tests, potentially streamlining the regulatory pathway for new diagnostic devices.

The FDA has evaluated EP12 and determined that it possesses the scientific and technical merit necessary to support regulatory requirements [3]. The standard is recognized in its entirety, reflecting the agency's confidence in the comprehensive nature of the guidance it provides [3]. Relevant FDA guidance documents that align with EP12 include "Statistical Guidance on Reporting Results from Studies Evaluating Diagnostic Tests" and "Appropriate Use of Voluntary Consensus Standards in Premarket Submissions for Medical Devices" [3].

For the global diagnostic industry, EP12 provides a harmonized approach to evaluating qualitative test performance, potentially facilitating international market access for tests developed according to its principles. The standard's comprehensive coverage of key performance parameters—including precision, clinical performance, stability, and interference—ensures that tests evaluated using its protocols undergo rigorous assessment comparable to international standards.

CLSI EP12 represents a comprehensive, scientifically robust framework for evaluating the performance of qualitative, binary output examinations throughout their development and implementation lifecycle. The third edition, published in 2023, incorporates significant advances in laboratory medicine since the previous 2008 edition, expanding its applicability to contemporary testing platforms from simple rapid tests to complex molecular assays [1] [2].

The guideline's structured approach to assessing precision, clinical performance, stability, and interference provides developers and laboratories with a standardized methodology for generating reliable performance data. Its recognition by regulatory bodies like the FDA further underscores its importance in the medical device ecosystem [3]. As qualitative tests continue to evolve in complexity and application, CLSI EP12 will remain an essential resource for ensuring their reliability, accuracy, and clinical utility in modern laboratory medicine.

Defining Qualitative, Binary Output Examinations and Their Scope

In the clinical laboratory, qualitative, binary output examinations are diagnostic tests designed to characterize a target condition with only two possible results [1] [2]. These outcomes are typically reported as dichotomous pairs such as positive/negative, present/absent, or reactive/nonreactive [1]. Within the framework of CLSI EP12 research, these tests are distinguished from quantitative assays (which provide a continuous numerical result) and other qualitative tests with more than two unordered output categories (nominal) or ordered outputs (ordinal or semi-quantitative), which fall outside the scope of the EP12 guideline [1] [6]. The fundamental objective of a binary examination is to deliver a straightforward "yes" or "no" answer regarding the presence of a specific analyte or condition, supporting critical clinical decisions in areas ranging from simple home testing to complex molecular diagnostics for diseases like cancer [2].

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) published the third edition of the EP12 guideline, "Evaluation of Qualitative, Binary Output Examination Performance," in March 2023 [2]. This document supersedes the earlier EP12-A2 version published in 2008 and provides an expanded framework for developers—including both commercial manufacturers and medical laboratories creating laboratory-developed tests (LDTs)—to design and evaluate binary examinations during the Establishment and Implementation stages of the Test Life Phases Model [1] [2]. The protocol is also intended to aid end-users in verifying examination performance within their specific testing environments, ensuring reliability and compliance with regulatory requirements recognized by bodies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [1].

The Evaluation Framework: Key Performance Parameters

Evaluating the performance of qualitative, binary tests requires a specific approach distinct from that used for quantitative assays. The CLSI EP12 guideline provides a structured framework for this evaluation, focusing on several critical parameters that collectively define a test's reliability and diagnostic utility [1].

Precision (Imprecision)

For qualitative tests, precision refers to the closeness of agreement between independent test results obtained under stipulated conditions, essentially measuring the test's random error and reproducibility [6]. In the context of binary outputs, precision evaluation often involves estimating the C5 and C95 thresholds—the analyte concentrations at which the test result is positive 5% and 95% of the time, respectively [1]. These thresholds help define the concentration range where the test response transitions from consistently negative to consistently positive, characterizing the assay's imprecision around its cutoff value. Precision studies may also include observer precision evaluations, particularly for tests that involve subjective interpretation of results [2].

Clinical Performance: Sensitivity and Specificity

The clinical performance of a binary test is primarily assessed through its sensitivity and specificity [1] [6]. These metrics evaluate the test's analytical accuracy or agreement with a reference method or clinical truth.

- Sensitivity (diagnostic sensitivity) measures the test's ability to correctly identify positive cases, calculated as the proportion of true positives detected among all actual positive samples.

- Specificity (diagnostic specificity) measures the test's ability to correctly identify negative cases, calculated as the proportion of true negatives detected among all actual negative samples.

Evaluation of clinical performance typically involves method comparison studies using contingency tables (2x2 tables) to compare the new test's results against a reference standard [6]. The experimental design must include appropriate clinical samples that adequately represent the intended use population and target condition.

Stability and Interference Testing

The updated EP12 guideline expands beyond precision and clinical performance to include evaluations of reagent stability and the effects of interfering substances [1] [2]. Stability testing determines the shelf-life of reagents and the test system's performance over time, while interference testing identifies substances that might adversely affect the test result, leading to false positives or false negatives. These additional parameters are crucial for ensuring the test's robustness under routine laboratory conditions and are particularly important for developers creating laboratory-developed tests or modifying existing commercial assays.

Table 1: Key Performance Parameters for Qualitative, Binary Output Examinations

| Parameter | Definition | Evaluation Method | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision (Imprecision) | Closeness of agreement between independent test results [6] | Estimation of C5 and C95 thresholds; reproducibility studies [1] | Measures random error and reproducibility |

| Sensitivity | Proportion of true positives correctly identified [6] | Method comparison with reference standard using contingency tables [6] | Ability to detect positive cases |

| Specificity | Proportion of true negatives correctly identified [6] | Method comparison with reference standard using contingency tables [6] | Ability to detect negative cases |

| Stability | Performance maintenance over time and under specified storage conditions [1] | Repeated testing of stored reagents at intervals [1] | Determines shelf-life and reliability |

| Interference | Effect of substances that may alter test results [1] | Testing samples with and without potential interferents [1] | Identifies sources of false positives/negatives |

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Methodologies

Integrated Protocol for Precision and Accuracy

A fundamental advancement in the evaluation of qualitative tests is the implementation of a single-experiment approach that simultaneously assesses both precision and accuracy [6]. This efficient protocol involves repeatedly testing a panel of samples that span the assay's critical range, particularly around the clinical cutoff point. The panel should include samples with known status (positive, negative, and near the cutoff) tested in multiple replicates across different runs, days, and operators if applicable. The resulting data allows for the construction of contingency tables that facilitate the calculation of both within-run and between-run precision (as percent agreement) and accuracy compared to the reference method [6]. This integrated approach provides a comprehensive view of the test's analytical performance while optimizing resource utilization.

Method Comparison Studies

When introducing a new binary test to replace an existing method, a method comparison study is essential [6]. This study involves testing an appropriate number of clinical samples (typically 50-100) by both the new and comparison methods, ensuring that the sample panel adequately represents the entire spectrum of the target condition, including positive, negative, and borderline cases. The results are then tabulated in a 2x2 contingency table, from which metrics such as overall percent agreement, positive percent agreement (analogous to sensitivity), and negative percent agreement (analogous to specificity) can be calculated. For complex tests such as those based on PCR methods or next-generation sequencing, the EP12 guideline provides supplemental information on determining the lower limit of detection and precision evaluation specific to these technologies [2].

Verification of Manufacturer Claims

For laboratories implementing commercially developed binary tests, the focus shifts from full validation to verification of the manufacturer's performance claims [6]. The CLSI EP12 protocol provides guidance for this verification process, which typically involves confirming the claimed sensitivity, specificity, and precision using a smaller set of samples tested in the laboratory's own environment with its personnel. This verification ensures that the test performs as expected in the specific setting where it will be used routinely and is required by accreditation standards such as CAP, ISO 15189, and ISO 17025 [6].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The evaluation of qualitative, binary output examinations requires specific materials and reagents to ensure accurate and reproducible results. The following table details key components essential for conducting performance assessments according to CLSI EP12 protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Evaluation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Specification | Application in Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Characterized Clinical Samples | Well-defined positive and negative samples for target analyte; should include levels near clinical cutoff [6] | Precision studies, method comparison, determination of sensitivity and specificity [6] |

| Reference Method Materials | Complete test system for comparison method (gold standard) [6] | Method comparison studies to establish accuracy and agreement [6] |

| Interference Test Substances | Potential interferents specific to test platform (e.g., hemoglobin, bilirubin, lipids, common medications) [1] | Interference testing to identify substances that may cause false positives or negatives [1] |

| Stability Testing Materials | Reagents stored under various conditions (temperature, humidity, light) and timepoints [1] | Stability evaluation to determine shelf-life and optimal storage conditions [1] |

| Quality Control Materials | Positive and negative controls with defined expected results [6] | Daily quality assurance, precision monitoring, lot-to-lot reagent verification [6] |

The CLSI EP12 guideline provides a standardized framework for defining and evaluating qualitative, binary output examinations, emphasizing their distinct nature from quantitative and semi-quantitative assays. The third edition, published in 2023, expands upon the previous EP12-A2 standard by incorporating broader test types, integrated protocols for design and validation, and additional evaluation parameters including stability and interference testing. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this scope and the corresponding evaluation methodologies is fundamental to ensuring the reliability and accuracy of binary tests across their development and implementation lifecycle. Proper application of these protocols—encompassing precision studies, clinical performance assessment, and interference testing—ensures that these clinically vital diagnostic tools perform consistently and meet regulatory requirements for their intended use.

Key Changes from EP12-A2 to the Current 3rd Edition

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guideline EP12, titled "Evaluation of Qualitative, Binary Output Examination Performance," serves as a critical framework for assessing the performance of qualitative diagnostic tests that produce binary outcomes (e.g., positive/negative, present/absent, reactive/nonreactive). The evolution from the Second Edition (EP12-A2) to the Third Edition (EP12-Ed3) represents a significant advancement in laboratory medicine protocols, reflecting the changing landscape of diagnostic technologies and regulatory requirements. Published on March 7, 2023, this latest edition incorporates substantial revisions that expand its applicability, enhance methodological rigor, and address emerging challenges in qualitative test evaluation [1].

The transition from EP12-A2 to EP12-Ed3 marks a paradigm shift from a primarily user-focused protocol to a comprehensive guideline serving both developers and end-users. While EP12-A2, published in 2008, provided "the user with a consistent approach for protocol design and data analysis when evaluating qualitative diagnostics tests" [7], the third edition substantially broadens this scope to include "product design guidance and protocols for performance evaluation of the Establishment and Implementation Stages of the Test Life Phases Model of examinations" [1]. This expansion acknowledges the growing complexity of qualitative examinations and the need for robust evaluation frameworks throughout the test lifecycle, from initial development through clinical implementation.

Expanded Scope and Application

Broadened Procedural Coverage

The third edition of EP12 significantly expands the types of procedures covered to reflect ongoing advances in laboratory medicine [1]. While EP12-A2 focused primarily on traditional qualitative diagnostics tests, EP12-Ed3 addresses the evaluation needs of contemporary binary output examinations, including laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) and advanced commercial assays. This expansion ensures the guideline remains relevant amidst rapid technological innovations in diagnostic testing.

The scope explicitly characterizes "a target condition (TC) with only two possible outputs (eg, positive or negative, present or absent, reactive or nonreactive)" [1]. The guideline maintains clear boundaries, excluding "examinations that provide outputs with more than two possible categories in an unordered (nominal) set or that report ordinal categories" [1]. This precise scope definition provides clarity for developers and laboratories in determining the appropriate evaluation framework for their specific tests.

Enhanced Target Audience

EP12-Ed3 is deliberately "written for both manufacturers of qualitative, binary, results-reporting or output examinations (referred to as qualitative, binary examinations throughout) and medical laboratories that create laboratory-developed, binary examinations (both termed developers)" [1]. This represents a substantial shift from EP12-A2, which primarily addressed laboratory personnel conducting verification studies. The expanded audience reflects the growing responsibility of both manufacturers and laboratories in ensuring test performance and reliability throughout the test lifecycle.

Table: Comparison of EP12-A2 and EP12-Ed3 Scope and Application

| Feature | EP12-A2 (2008) | EP12-Ed3 (2023) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | User evaluation of qualitative test performance [7] | Product design and performance evaluation for establishment and implementation stages [1] |

| Target Audience | Laboratory users conducting method evaluation [7] | Manufacturers and laboratories developing binary examinations (termed "developers") [1] |

| Procedures Covered | Qualitative diagnostic tests [7] | Expanded types reflecting advances in laboratory medicine [1] |

| Regulatory Recognition | FDA recognized [8] | FDA evaluated and recognized for regulatory requirements [1] [3] |

Key Technical Enhancements and Novel Content

Comprehensive Protocol Additions

EP12-Ed3 introduces substantial technical enhancements by adding "protocols to be used by developers, including commercial manufacturers or medical laboratories, during examination procedure design as well as for validation and verification" [1]. These protocols provide a structured framework for test development and evaluation that was not comprehensively addressed in the previous edition. The added protocols facilitate a more systematic approach to test design, potentially reducing development iterations and enhancing final product quality.

The third edition also incorporates "topics such as stability and interferences to the existing coverage of the assessment of precision and clinical performance (or examination agreement)" [1]. These additions address critical analytical performance characteristics that directly impact test reliability in real-world settings. Stability testing protocols help establish appropriate storage conditions and shelf-life determinations, while interference testing provides methodologies for identifying and quantifying substances that may affect test results.

Statistical Reorganization

A notable structural change in EP12-Ed3 involves "moving most of the statistical details, including equations, to the appendixes" [1]. This reorganization improves the document's usability by presenting essential methodological guidance in the main body while providing comprehensive statistical details in referenced appendices. This approach caters to both general users who require procedural overviews and statistical experts who need detailed computational methods.

The statistical foundation remains robust, with maintained focus on "imprecision, including estimating C5 and C95, clinical performance (sensitivity and specificity)" [1]. These statistical measures are essential for characterizing the analytical and clinical performance of qualitative tests, providing developers with standardized approaches for quantifying key performance parameters.

Enhanced Evaluation Framework

EP12-Ed3 Enhanced Evaluation Framework Diagram

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Precision Evaluation for Qualitative Tests

The precision evaluation protocols in EP12-Ed3 provide methodologies for assessing imprecision in qualitative, binary output examinations, including estimating C5 and C95 values [1]. These statistical measures help define the concentration levels at which a qualitative test has a 5% and 95% probability of producing a positive result, respectively. This approach allows for more nuanced understanding of test performance near the discrimination point.

The experimental design for precision studies typically involves:

- Sample Preparation: Selection or creation of samples with analyte concentrations spanning the expected decision point

- Repeated Testing: Multiple replicate measurements (typically 20-40) at each concentration level

- Data Analysis: Calculation of positive rates at each concentration level and determination of C5, C50, and C95 through probit or logit regression

- Contextual Interpretation: Consideration of precision estimates in relation to the clinical decision point

This methodology represents an advancement over EP12-A2 by providing more granular approaches for characterizing and quantifying imprecision in qualitative tests.

Clinical Performance Assessment

Clinical performance assessment, often described as examination agreement in qualitative tests, focuses on establishing sensitivity and specificity through method comparison studies [1]. EP12-Ed3 enhances these protocols to ensure robust determination of clinical utility.

The experimental workflow includes:

- Reference Method Selection: Identification of an appropriate reference method (gold standard) for comparison

- Sample Selection: Careful selection of clinical samples representing the entire spectrum of the target condition

- Blinded Testing: Parallel testing using both the new method and reference method without knowledge of results

- Statistical Analysis: Calculation of sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and likelihood ratios with confidence intervals

- Agreement Assessment: Evaluation of overall agreement and chance-corrected agreement using statistics like kappa

Table: Key Performance Characteristics in EP12 Evaluations

| Performance Characteristic | EP12-A2 Coverage | EP12-Ed3 Enhancements |

|---|---|---|

| Precision/Imprecision | Included with C5/C95 estimation [1] | Enhanced protocols with expanded statistical guidance [1] |

| Clinical Performance (Sensitivity/Specificity) | Method-comparison studies [7] | Comprehensive clinical performance assessment with stability and interference considerations [1] |

| Stability | Not explicitly covered | Added as a new topic with dedicated protocols [1] |

| Interference | Not explicitly covered | Added as a new topic with dedicated protocols [1] |

| Statistical Framework | Integrated in main text | Reorganized with equations in appendices [1] |

Stability and Interference Testing

The addition of stability and interference testing protocols represents one of the most significant enhancements in EP12-Ed3 [1]. These methodologies address critical real-world factors that impact test performance but were not comprehensively covered in the previous edition.

Stability Testing Protocol:

- Study Design: Implementation of real-time stability studies under intended storage conditions

- Time Points: Testing at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 3, 6, 9, 12 months) to establish performance degradation profiles

- Environmental Conditions: Evaluation of stability under various temperature, humidity, and light exposure conditions

- Reagent Performance: Assessment of critical reagent performance characteristics over time

- Data Analysis: Determination of expiration dates and storage requirements based on stability data

Interference Testing Protocol:

- Interferent Selection: Identification of potential interferents based on sample matrix and test methodology

- Sample Preparation: Creation of test samples with and without potential interferents at clinically relevant concentrations

- Experimental Comparison: Parallel testing of interferent-containing and control samples

- Result Analysis: Quantitative assessment of interference effects on test results

- Clinical Significance: Determination of whether observed interference has clinical significance

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for EP12 Protocol Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function in EP12 Evaluations |

|---|---|

| Characterized Clinical Samples | Serve as test materials for precision, clinical performance, and stability studies; must represent intended patient population [1] |

| Stability Testing Materials | Includes reagents, calibrators, and controls stored under various conditions for stability assessment [1] |

| Interference Testing Panels | Characterized samples containing potential interferents (hemolyzed, icteric, lipemic samples) at known concentrations [1] |

| Reference Standard Materials | Well-characterized materials for method comparison studies; serves as gold standard for clinical performance assessment [1] |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Specialized software supporting CLSI protocols for data analysis according to EP12 guidelines [9] |

| 2-Heptyl-4-quinolone-15N | 2-Heptyl-4-quinolone-15N, MF:C16H21NO, MW:244.34 g/mol |

| Cholesteryl isovalerate | Cholesteryl isovalerate, MF:C32H54O2, MW:470.8 g/mol |

Implications for Diagnostic Research and Development

The evolution from EP12-A2 to EP12-Ed3 has profound implications for diagnostic researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The enhanced framework supports more robust test development, potentially reducing late-stage development failures and facilitating regulatory submissions. The FDA's formal recognition of EP12-Ed3 "for use in satisfying a regulatory requirement" [1] [3] underscores its importance in the regulatory landscape.

For researchers implementing the updated guideline, the expanded scope necessitates earlier consideration of evaluation criteria during test design phases. The addition of stability and interference testing protocols requires allocation of additional resources during development but ultimately produces more comprehensive performance data. The reorganization of statistical content makes the guideline more accessible while maintaining technical rigor, potentially broadening its implementation across organizations with varying statistical expertise.

The continued focus on fundamental performance characteristics like sensitivity, specificity, and imprecision, while adding contemporary considerations, ensures that tests evaluated under EP12-Ed3 meet both traditional quality standards and modern performance expectations. This balanced approach facilitates the development of reliable qualitative diagnostics that can withstand the challenges of real-world clinical implementation.

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) EP12 guideline, titled "Evaluation of Qualitative, Binary Output Examination Performance," provides a critical framework for the performance assessment of qualitative diagnostic tests that produce binary results (e.g., positive/negative, present/absent, reactive/nonreactive). This protocol is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals involved in bringing in vitro diagnostic (IVD) tests to market or implementing them in clinical laboratories. The third edition of this guideline, published in March 2023, supersedes the EP12-A2 version and expands upon its predecessors by covering a broader range of modern procedures and providing more comprehensive guidance for the entire test life cycle [1] [2].

The core purpose of EP12 is to outline standardized methodologies for evaluating key analytical performance characteristics, ensuring that qualitative tests are reliable and clinically meaningful. Evaluations conducted according to EP12 are recognized by regulatory bodies, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), for satisfying regulatory requirements [1]. This guide focuses on the three pillars of performance characterization as defined within the EP12 framework: impression, clinical performance, and stability. A thorough understanding of these characteristics is fundamental to developing robust diagnostic tests and making evidence-based decisions about their adoption and use.

Evaluation of Imprecision

In the context of qualitative tests, imprecision refers to the random variation in test results upon repeated testing of the same sample. Unlike quantitative assays where imprecision is expressed as standard deviation or coefficient of variation, the evaluation of imprecision for binary output tests focuses on the consistency of the categorical result (positive or negative) [6].

Key Concepts and Protocols

A core concept in evaluating imprecision for qualitative assays is the estimation of the C5 and C95 concentrations. The C5 is the analyte concentration at which the test yields a positive result 5% of the time (the concentration where 5% of replicates are positive), while the C95 is the concentration at which 95% of replicates are positive. The range between C5 and C95 provides a measure of the assay's random error around its cutoff level [1]. Determining this range is crucial for understanding how an analyte's concentration near the decision threshold can lead to inconsistent categorical results.

CLSI EP12 recommends that precision studies be conducted over a period of 10 to 20 days to capture realistic sources of variation that might occur in the routine laboratory environment, such as different reagent lots, calibrators, operators, and environmental conditions [10]. This approach ensures that the estimated imprecision reflects the test's reproducibility in practice.

Experimental Design and Data Analysis

The experiment should include repeated testing of panels of samples with analyte concentrations known to be near the clinical decision point or the assay's cutoff. These samples should be tested in replicate over the designated time frame. The results are then analyzed to determine the proportion of positive and negative results at each concentration level.

The following workflow outlines the key steps for designing and executing an imprecision study according to EP12 principles:

Table 1: Key Reagents and Materials for Imprecision Studies

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Panel of Clinical Samples | Comprises the test specimens with analyte concentrations near the assay's cutoff, essential for defining the C5-C95 interval [10]. |

| Multiple Reagent Lots | Different manufacturing batches of the test kit reagents are used to incorporate inter-lot variation into the imprecision estimate [1]. |

| Quality Control Materials | Characterized samples with known expected results (positive and negative) used to monitor the assay's performance throughout the study duration. |

Evaluation of Clinical Performance

Clinical performance evaluation assesses a test's ability to correctly classify subjects who have the target condition (e.g., a disease) and those who do not. The primary metrics for this evaluation are diagnostic sensitivity and diagnostic specificity [1] [11] [10].

Sensitivity and Specificity

- Diagnostic Sensitivity is defined as the percentage of subjects with the target condition who test positive. It measures the test's ability to correctly identify true positives. A test with low sensitivity produces false negatives, which is critical to avoid in scenarios like blood donor screening or infectious disease diagnosis [11] [10].

- Diagnostic Specificity is the percentage of subjects without the target condition who test negative. It measures the test's ability to correctly identify true negatives. Low specificity leads to false positives, which can cause unnecessary anxiety and follow-up testing [11] [10].

To calculate these metrics, test results are compared against Diagnostic Accuracy Criteria (DAC), which represent the best available method for determining the true disease status (e.g., a gold standard reference method or a clinical consensus standard) [12] [10]. The comparison is typically presented in a 2x2 contingency table.

Table 2: 2x2 Contingency Table for Diagnostic Accuracy

| Diagnostic Accuracy Criteria (Truth) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Candidate Test Result | Positive | Negative |

| Positive | True Positive (TP) | False Positive (FP) |

| Negative | False Negative (FN) | True Negative (TN) |

| Sensitivity = TP / (TP + FN) x 100 | Specificity = TN / (TN + FP) x 100 |

Positive and Negative Percent Agreement (PPA/NPA)

In situations where a true gold standard is not available, and the candidate method is being compared to a non-reference comparative method, the terms Positive Percent Agreement (PPA) and Negative Percent Agreement (NPA) are used. The calculations are identical to those for sensitivity and specificity, but the context is different, as they measure agreement with a comparator rather than true diagnostic accuracy [12].

Experimental Design and Key Considerations

A robust clinical performance study requires careful planning. CLSI EP12 recommends testing a minimum of 50 positive and 50 negative specimens as determined by the DAC to reliably estimate sensitivity and specificity, respectively [11]. The samples must be representative of the intended use population and should account for various factors that can affect performance.

Several factors can significantly influence the observed sensitivity and specificity, and must be documented [11]:

- Reference Technique Used: The choice of DAC directly impacts the results.

- Type of Sample: The same test may perform differently with different sample matrices (e.g., nasal vs. nasopharyngeal swabs).

- Sample Group and Clinical Status: The stage of disease or patient demographics in the study group can affect performance.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Clinical Performance Studies

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Well-Characterized Clinical Samples | Banked specimens with disease status confirmed by Diagnostic Accuracy Criteria; the foundation for calculating sensitivity and specificity [11] [10]. |

| Reference Standard Method | The gold standard test or established clinical criteria used as the DAC to define the true positive and true negative status of every sample [12]. |

| Blinded Sample Panels | The set of samples, with identities concealed from the analyst, to prevent bias during testing with the candidate method [12]. |

Evaluation of Stability

Stability testing is critical for determining the shelf-life of reagents and the suitable storage conditions for samples, ensuring that test performance does not deteriorate over time. The third edition of EP12 has expanded its coverage of this topic, providing protocols for developers to establish and verify stability claims [1].

Types of Stability Evaluations

- Reagent Stability: This involves testing the performance of reagents throughout their proposed shelf-life, including the evaluation of real-time stability (storage under recommended conditions) and in-use stability (after first opening or reconstitution) [1].

- Sample Stability: This evaluation determines how long a sample can be stored before analysis without affecting the test result. Stability is assessed under different conditions (e.g., room temperature, refrigerated, frozen) and time points [1].

Experimental Protocol

The fundamental approach to stability testing is to compare the results obtained using aged reagents or stored samples against the results from fresh materials. The test samples used should include both positive and negative samples, with concentrations close to the clinical cutoff, as these are most sensitive to degradation.

A stability claim is generally supported when the agreement between the results from aged and fresh materials remains within a pre-defined acceptance criterion (e.g., ≥95% agreement) [1]. The point at which performance falls below this threshold defines the end of the stability period.

Table 4: Key Materials for Stability Evaluation

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Challenging Sample Panel | Includes weak positive samples and negative samples, which are most likely to show performance degradation due to reagent or sample instability [1]. |

| Aged Reagent Lots | Reagents stored for predetermined times under recommended and stress conditions (e.g., elevated temperature) to establish expiration dates [1]. |

| Stored Clinical Samples | Aliquots of patient samples stored for various durations and under different temperature conditions to establish sample stability claims [1]. |

The rigorous evaluation of impression, clinical performance, and stability is a non-negotiable requirement for the development and implementation of any reliable qualitative diagnostic test. The CLSI EP12 protocol provides a standardized, statistically sound framework for this characterization, ensuring that tests meet the necessary quality standards for clinical use. For researchers and drug development professionals, adherence to these guidelines is not merely a regulatory hurdle but a fundamental scientific process. It mitigates the risk of deploying unreliable tests, which can lead to misdiagnosis, patient harm, and inefficient use of resources. By systematically applying the principles and experimental designs outlined in CLSI EP12, the diagnostic industry can continue to advance, providing healthcare providers with the accurate and dependable tools essential for modern medicine.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's recognition of consensus standards represents a critical mechanism for streamlining the regulatory evaluation of medical devices, including in vitro diagnostic tests. This process allows manufacturers to demonstrate conformity with established standards, thereby providing a efficient pathway to market while ensuring device safety and effectiveness. The FDA Standards Recognition Program evaluates consensus standards for their appropriateness in reviewing medical device safety and performance, with technical and clinical staff throughout the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) participating in standards development and evaluation [13]. For researchers and developers working with qualitative test performance protocols, understanding this recognition process is essential for navigating regulatory requirements and optimizing product development strategies.

The recognition system operates under the authority of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), which enables the FDA to identify standards to which manufacturers may submit a declaration of conformity to demonstrate they have met relevant regulatory requirements [13]. This framework creates a predictable pathway for device evaluation, potentially reducing the regulatory burden on manufacturers while maintaining the FDA's rigorous standards for safety and effectiveness. The agency may recognize standards wholly, partially, or not at all based on their scientific and technical merit and relevance to regulatory policies [3].

FDA Recognition of CLSI EP12 Standards

Evolution from EP12-A2 to EP12 3rd Edition

The CLSI EP12 standard has undergone significant evolution, with the FDA formally recognizing the most recent version. The trajectory of this standard demonstrates the dynamic nature of regulatory science and the importance of maintaining current knowledge of recognized standards:

Table: Evolution of CLSI EP12 Standard

| Standard Version | Status | Publication Date | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| EP12-A2 | Superseded | 2008 | Provided protocol design and data analysis guidance for precision and method-comparison studies [14] |

| EP12 3rd Edition | Active & FDA-Recognized | March 7, 2023 | Expanded procedures, added developer protocols, included stability and interference topics [1] |

The FDA formally recognized CLSI EP12 3rd Edition on May 29, 2023, granting it recognition number 7-315 and declaring it relevant to medical devices "on its scientific and technical merit and/or because it supports existing regulatory policies" [3]. This recognition signifies that developers of qualitative, binary output tests can submit a declaration of conformity to this standard in premarket submissions, potentially streamlining the regulatory review process.

Key Technical Scope of CLSI EP12 3rd Edition

The recognized EP12 3rd Edition provides comprehensive guidance for evaluating qualitative tests with binary outcomes (e.g., positive/negative, present/absent, reactive/nonreactive). Its technical scope encompasses:

- Performance evaluation protocols for both establishment and implementation stages of the Test Life Phases Model [1]

- Assessment of imprecision through C5 and C95 estimation [1]

- Clinical performance evaluation including sensitivity and specificity determinations [1]

- Stability and interference testing to ensure reagent integrity and result accuracy [1]

- Framework verification for laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) and manufacturer-developed examinations [1]

The standard specifically excludes evaluation of tests with more than two possible output categories (nominal sets) or ordinal categories, focusing exclusively on binary outputs [3]. This focused scope ensures specialized guidance for the unique statistical and validation challenges presented by qualitative binary tests.

FDA Recognition Process Framework

Standards Recognition Pathway

The FDA has established a structured process for evaluating and recognizing consensus standards, which is critical for developers to understand when planning regulatory strategies. The recognition pathway follows a systematic approach with defined timelines and requirements:

FDA Standards Recognition Pathway

The recognition process begins when any interested party submits a request containing specific information, including the standard's title, reference number, proposed list of applicable devices, and the scientific, technical, or regulatory basis for recognition [13]. The FDA commits to responding to all recognition requests within 60 calendar days from receipt, demonstrating the agency's commitment to timely standardization [13].

Upon positive determination, the standard is added to the FDA Recognized Consensus Standards Database, where it receives a recognition number and a Supplemental Information Sheet (SIS) [13]. Importantly, manufacturers may immediately begin using the standard for declarations of conformity once it appears in the database, without waiting for formal publication in the Federal Register, though such publication does occur periodically [15] [13].

Implementation in Regulatory Submissions

For researchers and developers, the practical implementation of recognized standards in regulatory submissions represents a critical phase of the product development lifecycle. The FDA provides clear guidelines for leveraging recognized standards:

- Voluntary Conformity: Manufacturers may voluntarily choose to conform to FDA-recognized consensus standards, but conformance is not mandatory unless a standard is "incorporated by reference" into regulation [13]

- Declaration of Conformity: When manufacturers elect to conform to recognized standards, they may submit a "declaration of conformity" to satisfy relevant regulatory requirements [13]

- Premarket Submission Identification: Applicants should clearly identify any referenced standards in their CDRH Premarket Review Submission Cover Sheet (Form FDA 3514) [13]

This framework creates efficiencies in the device review process by reducing redundant testing and providing a common language for evaluating device performance. As noted by the FDA, "Standards are particularly useful when an FDA-recognized consensus standard exists that serves as a complete performance standard for a specific medical device" [13].

Implications for Qualitative Test Development

Practical Application of CLSI EP12 3rd Edition

The recognition of CLSI EP12 3rd Edition carries significant implications for developers of qualitative binary tests. The standard provides specific methodological guidance that aligns with regulatory expectations:

Table: CLSI EP12 Experimental Framework Components

| Component | Protocol Guidance | Regulatory Application |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Sensitivity | Protocols for limit of detection (LOD) determination, particularly for PCR-based methods [2] | Supports claims for test detection capabilities |

| Precision Evaluation | Procedures for estimating C5 and C95, including next-generation sequencing and observer precision studies [2] | Demonstrates test reproducibility under specified conditions |

| Clinical Performance | Framework for assessing sensitivity, specificity, and examination agreement [1] | Validates clinical utility and diagnostic accuracy |

| Interference Testing | Methodologies for identifying substances that may affect test performance [1] | Establishes test limitations and appropriate use conditions |

| Stability Assessment | Protocols for establishing reagent stability claims [1] | Supports labeled shelf life and storage conditions |

According to Jeffrey R. Budd, PhD, Chairholder of CLSI EP12, "The third edition of CLSI EP12 describes the different types of these tests, how to accurately provide yes/no results for each, and how to assess their analytical and clinical performance. It covers binary, qualitative examinations whether they have an internal continuous response or not" [2]. This comprehensive coverage makes the standard applicable across a wide range of technologies, from simple rapid tests to complex molecular assays.

Strategic Advantages for Test Developers

The use of FDA-recognized standards like CLSI EP12 3rd Edition provides strategic advantages throughout the product lifecycle:

- Streamlined Regulatory Review: Conformity with recognized standards facilitates the premarket review process for 510(k), De Novo, PMA, and other submission types [13]

- Reduced Submission Burden: Appropriate use of declarations of conformity may reduce the amount of supporting testing documentation typically needed [13]

- Early Regulatory Alignment: Engaging with recognized standards during development phases helps align products with regulatory expectations before submission

- Benchmarking Against Established Criteria: Provides objective performance criteria for evaluating test performance against market expectations

The FDA emphasizes that "Conformity to relevant standards promotes efficiencies and quality in regulatory review" [13], highlighting the mutual benefits for both developers and regulators.

Experimental Framework for Qualitative Test Evaluation

Core Methodological Approaches

CLSI EP12 3rd Edition establishes rigorous experimental frameworks for evaluating qualitative binary tests. The key methodological approaches include:

Experimental Framework for Qualitative Tests

The standard provides specific protocols for each evaluation dimension, with statistical details and equations moved to appendices in the current edition to improve usability [1]. This structure makes the standard more accessible while maintaining technical rigor.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of CLSI EP12 evaluation protocols requires specific reagent solutions with defined characteristics:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Qualitative Test Evaluation

| Reagent Category | Function in Evaluation | Performance Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard Panels | Establish ground truth for clinical sensitivity/specificity studies | Well-characterized specimens with known target status [16] |

| Interference Substances | Identify potential interferents affecting test performance | Common endogenous and exogenous substances relevant to specimen type [1] |

| Stability Materials | Support claimed reagent stability under various storage conditions | Representative production lots stored under controlled conditions [1] |

| Precision Panels | Evaluate within-run and between-run imprecision | Samples with analyte concentrations near clinical decision points [1] |

| Calibration Materials | Standardize instrument responses across testing platforms | Traceable to reference materials when available [16] |

These reagent solutions form the foundation for robust test evaluation according to recognized standards, enabling developers to generate reliable evidence of performance characteristics.

Regulatory Integration and Future Directions

Integration with Broader Regulatory Framework

CLSI EP12 3rd Edition does not exist in isolation but functions within a broader ecosystem of regulatory standards and guidances. The FDA recognition of this standard intersects with several important regulatory policies:

- Special Controls Guidance: For certain device types, such as reagents for detection of specific novel influenza A viruses, the standard functions alongside special controls that may include distribution restrictions to qualified laboratories [16]

- Multiple Submission Pathways: The standard supports various regulatory pathways, including traditional and abbreviated 510(k) submissions, where declarations of conformity can reduce submission burden [13]

- Postmarket Performance Validation: The standard's frameworks support both premarket evaluation and postmarket validation activities, creating continuity across the device lifecycle [16]

The FDA emphasizes that "While manufacturers are encouraged to use FDA-recognized consensus standards in their premarket submissions, conformance is voluntary, unless a standard is 'incorporated by reference' into regulation" [13]. This balanced approach encourages standards use while maintaining regulatory flexibility.

Emerging Trends in Standards Recognition

The field of standards recognition continues to evolve, with several emerging trends impacting how researchers and developers should approach qualitative test evaluation:

- Accelerated Recognition Process: The FDA has implemented a more responsive recognition system with mandated 60-day response timelines and immediate effectiveness upon database entry [13]

- ASCA Program Expansion: The Accreditation Scheme for Conformity Assessment (ASCA) program enhances confidence in declarations of conformity through qualified accreditation bodies and testing laboratories [13]

- Dynamic Standard Updates: The recognition of the EP12 3rd Edition just months after its publication demonstrates the FDA's commitment to maintaining current standards [3] [2]

- Global Harmonization: International alignment of standards reduces barriers to global market access and facilitates efficient test development

These trends highlight the increasing importance of standards conformity as a strategic tool in the medical device development process, particularly for complex qualitative tests requiring robust performance validation.

The FDA recognition of consensus standards like CLSI EP12 3rd Edition represents a cornerstone of the modern medical device regulatory framework. For developers of qualitative binary tests, understanding and implementing this recognized standard provides a pathway to demonstrating both analytical and clinical performance in alignment with regulatory expectations. The rigorous methodological framework offered by EP12, combined with the efficiency of the FDA recognition process, creates a predictable environment for test development and validation. As the field of diagnostic testing continues to evolve with emerging technologies and novel applications, the role of recognized standards in ensuring test reliability while facilitating efficient market access will remain increasingly important for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Implementing EP12 Protocols: A Step-by-Step Methodological Guide

Designing Precision Studies and Estimating the Imprecision Interval (C5 to C95)

Within the framework of CLSI EP12, the evaluation of qualitative, binary-output tests (e.g., positive/negative, present/absent) is foundational to clinical laboratory medicine [1]. Unlike quantitative tests, which report numerical values over a continuous range, qualitative tests classify samples into one of two distinct categories. The precision of these tests—the agreement between repeated measurements of the same sample—cannot be expressed by conventional statistics like the mean and standard deviation. Instead, precision is characterized by an imprecision interval, defined by the concentrations C5 and C95 [17]. This interval is a critical performance parameter, describing the inherent random error of a binary measurement process and the uncertainty in classifying a sample near its medical decision point.

This guide provides an in-depth technical exploration of designing precision studies and estimating the C5 to C95 imprecision interval, framed within the context of advanced research on the CLSI EP12-A2 protocol [18]. Although the EP12-A2 guideline has been superseded by a newer third edition, its foundational principles for precision evaluation remain highly relevant for scientists and drug development professionals designing robust validation studies for in vitro diagnostics [1] [18]. A thorough understanding of this protocol is essential for developing reliable tests, from rapid lateral flow assays to sophisticated PCR-based examinations.

Core Theoretical Concepts

The Imprecision Interval (C5 to C95)

For qualitative tests with an internal continuous response, a cutoff (CO) value is established to dichotomize the raw signal into a binary output. The C50 is the analyte concentration at which a test produces 50% positive and 50% negative results; it represents the medical decision level and often aligns with the test's stated cutoff [17]. However, due to analytical imprecision, there is not a single concentration that cleanly separates "positive" from "negative" results. Instead, there exists a range of concentrations around the C50 where the test result becomes probabilistic.

The imprecision interval quantifies this uncertainty:

- C5: The analyte concentration at which only 5% of test results are positive (and 95% are negative). This is the lower bound of the imprecision interval.

- C95: The analyte concentration at which 95% of test results are positive (and 5% are negative). This is the upper bound of the imprecision interval.

The range from C5 to C95 effectively captures the concentration band where the test result is uncertain. A narrower interval indicates a more precise and reliable test, while a wider interval signifies greater random error and more misclassification near the cutoff [17].

Relationship to Binary Data and Probability

The relationship between analyte concentration and the probability of a positive result is described by a cumulative distribution function, which produces an S-shaped curve [17]. This curve can be derived from the proportion of positive results observed at different analyte concentrations. The key idea is that random variation, or imprecision, in a binary measurement process can be fully characterized by this cumulative probability curve. The C5, C50, and C95 points are read directly from this curve, providing a complete description of the test's classification performance around its cutoff.

Table 1: Key Definitions for Imprecision Interval Estimation

| Term | Definition | Interpretation in Precision Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| C5 | Analyte concentration yielding 5% positive results. | Concentration where a sample is almost always negative; lower limit of misclassification. |

| C50 | Analyte concentration yielding 50% positive results. | The medical decision level or cutoff; point of maximal uncertainty. |

| C95 | Analyte concentration yielding 95% positive results. | Concentration where a sample is almost always positive; upper limit of misclassification. |

| Imprecision Interval | The concentration range from C5 to C95. | Quantifies the "gray area" where result misclassification occurs; a narrower interval indicates better precision. |

| Binary Output | A test result with only two possible outcomes (e.g., Positive/Negative). | Prevents use of traditional mean/SD; requires estimation of proportions for precision studies. |

Experimental Design and Protocol

Designing a robust precision study according to CLSI EP12 principles requires careful planning of sample selection, replication, and data collection.

Sample Panel Preparation

The core of the precision experiment is a panel of samples with analyte concentrations spanning the expected imprecision interval, with a particular focus on concentrations near the C50.

- Target Concentrations: The study must include samples at the stated cutoff (C50) and at least two additional concentration levels: one between C5 and C50, and one between C50 and C95 [1] [17]. If the C5 and C95 values are unknown initially, a preliminary experiment using samples at 70%, 90%, 100%, 110%, and 130% of the cutoff can help bracket the interval.

- Sample Matrix: The sample matrix should mimic real patient specimens as closely as possible to ensure the results are clinically relevant.

- Replication: Each concentration level must be tested repeatedly to reliably estimate the proportion of positive results. CLSI EP12 recommends a minimum of 20 replicates per concentration level, though larger replication (e.g., 40 or 60) will provide a more precise estimate of the proportion [17].

Data Collection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for conducting the precision experiment, from preparation to initial analysis.

Data Analysis and Estimation of C5 and C95

Fitting the Dose-Response Curve

The recorded data—consisting of concentrations and their corresponding observed proportions of positive results—must be fitted to a model to generate a smooth dose-response curve. The most common model used for this purpose is the logistic regression model (or probit model), which produces the characteristic S-shaped curve [17].

The logistic model is defined as: ( P(Positive) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(B0 + B1 \times \text{Concentration})}} ) where ( B0 ) and ( B1 ) are the intercept and slope parameters estimated from the data using statistical software.

Estimating C5, C50, and C95 from the Model

Once the logistic model is fitted, the C5, C50, and C95 concentrations are calculated by solving the model equation for the concentration (X) that yields probabilities (P) of 0.05, 0.50, and 0.95, respectively.

- C50 Calculation: Set ( P = 0.50 ). Since ( e^0 = 1 ), the equation simplifies to ( C50 = -B0 / B1 ).

- C5 and C95 Calculation: Set ( P = 0.05 ) and ( P = 0.95 ) respectively and solve for X. The general formula is: ( C = [ln(\frac{P}{1-P}) - B0] / B1 )

This analysis is typically performed with statistical software (e.g., R, SAS, Python) which can provide both the parameter estimates and confidence intervals for the estimated C5 and C95 points.

Table 2: Example Data and Results from a Simulated Precision Study

| Analyte Concentration | Number of Replicates | Number of Positive Results | Observed Proportion Positive |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8 × Cutoff | 40 | 3 | 0.075 |

| 0.9 × Cutoff | 40 | 12 | 0.300 |

| 1.0 × Cutoff (C50) | 40 | 21 | 0.525 |

| 1.1 × Cutoff | 40 | 32 | 0.800 |

| 1.2 × Cutoff | 40 | 37 | 0.925 |

| Calculated Parameter | Estimated Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| C5 | 0.82 × Cutoff | (0.78 - 0.86) × Cutoff | |

| C50 | 1.01 × Cutoff | (0.98 - 1.04) × Cutoff | |

| C95 | 1.20 × Cutoff | (1.16 - 1.24) × Cutoff | |

| Imprecision Interval | 0.38 × Cutoff |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following reagents and materials are critical for executing a precision study according to CLSI EP12.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Precision Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Precision Study |

|---|---|

| Characterized Panel of Samples | A set of samples with analyte concentrations spanning the C50. Used to challenge the test across its imprecision interval. |

| Negative Control (Blank) Matrix | The sample matrix without the target analyte. Essential for establishing the baseline response and for use in preparation of diluted samples. |

| Positive Control Material | A material with a known, high concentration of the analyte. Used to create the dilution series for the precision panel. |

| Stable Reference Material | A well-characterized control material used for long-term monitoring of the C50 and imprecision interval, ensuring consistency across multiple experiment runs. |

| Interference Substances | While primarily for specificity studies, these are used in related experiments to assess the robustness of the C50 against common interferents like lipids or hemoglobin [1] [17]. |

| GPhos Pd G6 | GPhos Pd G6, MF:C47H70BrO4PPdSi, MW:944.4 g/mol |

| Cholesteryl 11(Z)-Vaccenate | Cholesteryl 11(Z)-Vaccenate, MF:C45H78O2, MW:651.1 g/mol |

Integration with Broader Test Performance Validation

Estimating the imprecision interval is not an isolated activity; it is a core component of a comprehensive test validation strategy as outlined in CLSI EP12. The findings from the precision study directly inform other critical validation phases.

- Clinical Agreement Studies: The estimated C5 and C95 values help explain the test's performance at the "clinical gray zone," providing context for observed false positives and false negatives in method comparison studies [19] [17]. A sample with an analyte concentration near the C95, for instance, might be a true positive that is occasionally misclassified, impacting clinical sensitivity.

- Analytical Specificity (Interference) Studies: The precision interval should be re-evaluated in the presence of potential interferents. A stable C50 in the presence of interferents indicates a robust method, whereas a significant shift suggests vulnerability to interference [1] [17].

- Setting Quality Control Rules: Understanding the width of the imprecision interval is vital for designing a statistically sound QC plan. Laboratories can use this information to select appropriate QC concentrations and establish Westgard rules that effectively monitor for significant shifts in the test's calibration (C50) or precision (C5-C95 width) [17].

Designing rigorous precision studies and accurately estimating the C5 to C95 imprecision interval are fundamental to establishing the reliability of any qualitative, binary-output examination. The CLSI EP12-A2 protocol provides a structured, statistically sound framework for this process, guiding researchers through sample preparation, replicate testing, and sophisticated data analysis to quantify the "gray zone" of a test. In an era of rapidly evolving diagnostic technologies, from point-of-care tests to high-throughput automated systems, mastering these principles is indispensable for scientists and developers committed to delivering accurate and trustworthy diagnostic tools that support optimal patient care.