Key Factors Influencing Microbial Community Composition: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the multifaceted factors governing microbial community composition, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Key Factors Influencing Microbial Community Composition: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the multifaceted factors governing microbial community composition, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational ecological principles and environmental drivers shaping microbiomes, examines cutting-edge molecular and computational methodologies for community profiling and prediction, addresses challenges in community management and optimization for clinical outcomes, and discusses validation frameworks for comparative analysis across diverse ecosystems. By synthesizing insights from natural and engineered environments, the content aims to bridge microbial ecology with therapeutic discovery and biomedical innovation.

The Core Drivers: Unraveling Environmental and Biological Factors Shaping Microbial Ecosystems

In microbial ecology, understanding the drivers of community composition is fundamental for predicting ecosystem functioning and responses to environmental change. While biotic interactions undeniably shape these communities, the foundational framework is established by abiotic factors—the non-living chemical and physical components of an environment. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to three pivotal abiotic factors: pH, nutrient availability, and substrate properties. Framed within the context of a broader thesis on microbial community composition, this document synthesizes current research to elucidate how these factors serve as master variables, filtering for specific microbial taxa, modulating metabolic potential, and ultimately governing community assembly and function. The insights herein are critical for researchers and scientists aiming to manipulate microbial systems for applications in drug development, where controlling the microbial microenvironment can be paramount to success.

Core Abiotic Factors and Their Microbial Impacts

The soil and aquatic environments host complex microbial communities whose structure and function are profoundly influenced by abiotic conditions. Key among these are soil pH, nutrient availability, and the physical properties of the substrate, each acting as a selective pressure that shapes the microbial landscape.

Soil pH

Soil pH is widely regarded as one of the most dominant factors influencing microbial community composition and diversity. It exerts a broad influence on the solubility of minerals, the chemical speciation of nutrients and toxins, and the physiological functioning of microbial cells.

- Microbial Diversity and Composition: Numerous studies have established a strong correlation between pH and microbial diversity. Research on Larix plantations demonstrated that soil temperature and NHâ‚„âº-N, both indirectly influenced by soil conditions including pH, were key drivers of microbial biomass C:N:P stoichiometry [1]. pH's effect extends to determining the relative dominance of major microbial phyla. For instance, the second most abundant bacterial phylum, Acidobacteria, is aptly named for its prevalence in acidic soils, where its role in the soil carbon cycle becomes crucial [2] [3].

- Functional Consequences: The pH gradient directly affects microbial functional potential. A study on acidic tea garden soils revealed that in strongly acidic soil (pH 4.12), the interaction between soil pH and carbon chemistry was the primary determinant of microbial community composition [4]. This interplay significantly influences processes like soil organic carbon (SOC) decomposition and the enzymatic activities that drive nutrient cycling.

Nutrient Availability

The availability of essential macro- and micronutrients, particularly nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P), forms a critical template upon which microbial communities are built. Nutrient levels act as a bottom-up control, determining the carrying capacity of the environment and selecting for taxa with specific life-history strategies and metabolic capabilities.

- Nitrogen and Phosphorus Dynamics: The ecological success of Heliotropium arboreum in coastal ecosystems was linked to nutrient availability, which significantly shaped its associated microbial communities [5]. Quantitative correlations showed that specific bacterial genera like Bryobacter (r = 0.810) and Stenotrophobacter (r = 0.496) exhibited strong positive correlations with nitrogen availability. Similarly, fungal genera such as Preussia (r = 0.585) and Metacordyceps (r = 0.616) were positively correlated with nutrient levels [5]. This suggests that these taxa may serve as bioindicators of nutrient-rich conditions.

- Carbon-to-Nitrogen (C/N) Stoichiometry: The balance of nutrients is equally important. An incubation experiment using crop residues with varying C/N ratios found that rapeseed cake (C/N ratio of 7.6) was particularly effective in enhancing soil multifunctionality and mitigating acidification in acidic soils [4]. This low C/N residue likely provided a balanced nutrient source, promoting microbial activity and altering community composition, notably reducing the fungal-to-bacterial ratio in slightly acidic soil.

Table 1: Correlation of Microbial Genera with Nutrient Availability in Coastal Ecosystems [5]

| Microbial Group | Genus | Correlated Nutrient | Correlation Coefficient (r) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Bryobacter | Nitrogen | 0.810* |

| Bacteria | Stenotrophobacter | Nitrogen | 0.496* |

| Fungi | Preussia | Nutrients (N/P) | 0.585* |

| Fungi | Metacordyceps | Nutrients (N/P) | 0.616* |

Substrate Properties

The physical and chemical nature of the substrate, encompassing soil structure, texture, porosity, and soil depth, creates a three-dimensional matrix that defines the microbial habitat. These properties influence the movement of gases, water, nutrients, and the microbes themselves.

- Soil Depth and Gradients: Soil is a highly heterogeneous environment with pronounced vertical gradients. Key physicochemical properties such as bulk density, porosity, and water content change significantly with depth [2]. Subsoils tend to have higher bulk density and lower porosity, which restricts the movement of gases, leading to more anaerobic conditions and selecting for microbial communities adapted to low oxygen availability [2]. Furthermore, nutrient contents like organic carbon and nitrogen generally decrease with depth, resulting in a parallel decline in microbial abundance and overall activity [2].

- Physical Structure and Microbial Life: The physical structure, defined by soil aggregation and pore spaces, is critical. Soil porosity determines the connectivity of habitats and the ease with which microbes can disperse. Smaller, less frequent pores in deeper soils impede the movement of not only microbes but also substrates and nutrients, thereby limiting microbial activity [2]. Calcium promotes the formation of soil aggregates, which create diverse metabolic niches for microbes, while also sequestering carbon and potentially limiting its availability [2].

Table 2: Changes in Soil and Microbial Properties with Depth [2]

| Property | Trend with Increasing Soil Depth | Impact on Microbial Community |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk Density | Increases | Restricts root growth and gas diffusion; favors anaerobes. |

| Porosity | Decreases | Impedes movement of microbes, substrates, and Oâ‚‚. |

| Organic Carbon & Nitrogen | Decrease | Leads to lower microbial biomass and overall activity. |

| Microbial Activity | Decreases | Slower nutrient cycling; longer carbon residence times. |

| EPS (Extracellular Polymeric Substances) Content | Generally decreases | Reduced soil aggregation and biomineralization potential. |

Experimental Protocols for Disentangling Abiotic and Biotic Effects

A critical challenge in microbial ecology is distinguishing the direct effects of abiotic factors from the indirect effects mediated through biotic interactions. The following protocol outlines a controlled mesocosm approach to address this challenge.

Objective: To disentangle the effects of abiotic (nutrients, micropollutants) and biotic (microorganisms) factors in treated wastewater on the antibiotic resistance gene abundance in natural stream biofilms.

Methodology:

- Experimental Setup: A flow-through channel system is established with two buffer tanks. The system is fed with different mixtures of a peri-urban stream and wastewater effluent.

- Treatment Design:

- Water Source Mixtures: Stream water is mixed with wastewater effluent at 0% (control), 30%, and 80% concentrations.

- Filtration Manipulation: For the 30% and 80% wastewater treatments, two conditions are created:

- Non-ultrafiltered WW: Contains both abiotic factors and biotic inoculum from wastewater.

- Ultrafiltered WW (UF): Passed through a 0.4 µm filter to remove microorganisms and particles, retaining the abiotic factors.

- Biofilm Cultivation: Glass slides are placed in each channel to allow for natural biofilm colonization over a four-week period.

- Monitoring and Sampling:

- Physicochemical Parameters: Flow rate, conductivity, and temperature are monitored online. A broad panel of nutrients and micropollutants is measured weekly.

- DNA Extraction: After the incubation period, biofilms are scraped from the slides, and genomic DNA is extracted for downstream analysis.

- Metagenomic Analysis: Shotgun metagenomic sequencing is performed on the DNA extracts. Taxonomic and functional profiling (including ARG abundance) is conducted using bioinformatic tools. Differences in the biofilm microbiome and resistome between the UF and non-UF treatments are attributed to the biotic factor (inoculum), while changes across dilution percentages are linked to the abiotic factor (nutrient/contaminant concentration).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting experiments in microbial ecology, particularly those focused on abiotic factors.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Microbial Ecology Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerBiofilm Kit (QIAGEN) | Extraction of high-quality genomic DNA from complex biofilm samples. | DNA extraction from stream biofilms grown on glass slides in flume experiments [6]. |

| Illumina NovaSeq Platform | High-throughput shotgun metagenomic sequencing for comprehensive taxonomic and functional profiling. | Sequencing of biofilm DNA to analyze resistome and microbiome composition [6]. |

| Ultrafiltration System (0.4 µm pore size) | Physical separation of microorganisms and particles from liquid samples to isolate abiotic factors. | Creation of ultrafiltered wastewater effluent for disentangling biotic and abiotic effects [6]. |

| Crop Residues (Varying C/N Ratios) | Amendment to soil to investigate the effects of carbon chemistry and nutrient stoichiometry on microbial communities. | Studying the mitigation of soil acidification and shifts in microbial composition [4]. |

| Soil Auger and Sieve (2 mm mesh) | Collection of standardized soil samples and removal of large plant debris for homogeneous analysis. | Collection of soil cores from different depths and plots in forest plantation studies [1]. |

| Temperature and Moisture Loggers | Continuous in-situ monitoring of microclimatic conditions in soil or water. | Measuring soil temperature and water content at 0-10 cm depth in Larix plantations [1]. |

| Notoginsenoside T5 | Notoginsenoside T5, MF:C41H68O12, MW:753.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (R)-O-isobutyroyllomatin | (R)-O-isobutyroyllomatin | Get high-purity (R)-O-isobutyroyllomatin for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

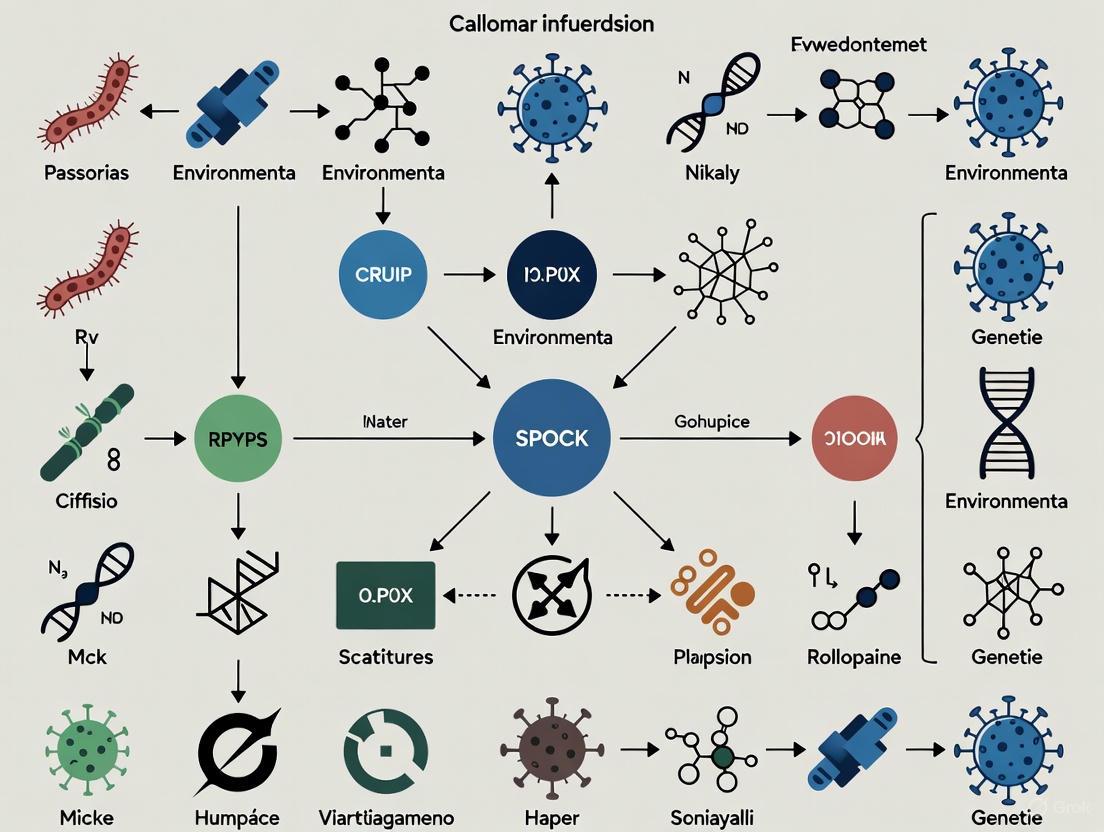

Conceptual Framework of Abiotic Factor Interactions

The abiotic factors discussed do not operate in isolation but interact in complex ways to shape microbial communities. The following diagram synthesizes these relationships into a conceptual framework.

The roles of pH, nutrient availability, and substrate properties as abiotic factors are foundational to the study of microbial community composition. As this whitepaper has detailed, these factors are not merely environmental backdrop but are active, interconnected drivers that filter for specific taxa, shape functional potential, and constrain ecosystem processes. The experimental protocols and conceptual frameworks presented provide researchers with the tools to dissect these complex interactions. For professionals in drug development, a deep understanding of these principles is invaluable, whether for sourcing novel biocatalysts from extreme environments, understanding the microenvironment of a production fermenter, or combating antibiotic resistance by tracking ARG dissemination in the environment. Mastering the abiotic context is, therefore, a critical step in predicting and harnessing the power of microbial systems.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the core biotic interactions—mutualism, competition, and predation—within the context of contemporary microbial community research. Understanding these interactions is fundamental to deciphering the complex assembly rules, stability, and functional outputs of microbial ecosystems. The field is increasingly moving beyond simple taxonomic catalogs toward a mechanistic, process-oriented understanding of how microorganisms interact with each other and their environment. This paradigm shift is critical for multiple applied fields, including drug development, where microbial interactions represent a largely untapped reservoir of bioactive compounds and therapeutic targets. Framed within the broader thesis of factors influencing microbial community composition, this whitepaper details the experimental and analytical frameworks required to move from correlation to causation in microbial interaction studies, enabling researchers to precisely quantify these dynamics and harness them for scientific and clinical innovation.

Theoretical Foundations of Biotic Interactions

Biotic interactions are fundamental forces that shape the structure, dynamics, and function of all biological communities. In microbial systems, these interactions occur at multiple spatial and temporal scales, from direct cell-to-cell contact to diffuse interactions mediated through chemical signals and environmental modifications.

Mutualism describes an interaction between two or more species where all participants derive a fitness benefit. This interdependence is crucial for the survival and success of many organisms within ecosystems [7]. A classic macrobiological example is the obligate mutualism between certain ants and acacia trees, where ants protect the tree from herbivores in exchange for shelter and food [7]. In microbial systems, mutualism often takes the form of cross-feeding, where one organism consumes the metabolic byproducts of another, or syntrophy, a specific form of metabolic cooperation that allows partners to degrade substrates neither could process alone. These interactions can be obligate, where species are entirely dependent on each other for survival, or facultative, where species benefit but can survive independently [7].

Competition is an interaction wherein organisms or species vie for the same limited resources, such as nutrients, space, or light, resulting in harm to all competitors [7]. The intensity of competition is often highest among phylogenetically similar organisms due to niche overlap. Competition is classically divided into:

- Intraspecific Competition: Occurs between individuals of the same species [7].

- Interspecific Competition: Occurs between individuals of different species [7]. The outcome of sustained interspecific competition is often governed by the Competitive Exclusion Principle, which states that two species with identical ecological niches cannot coexist indefinitely; one will eventually outcompete and displace the other [7]. This can lead to evolutionary divergence in resource use, a process known as resource partitioning.

Predation is an interaction where one organism (the predator) consumes another (the prey) [7]. In microbial contexts, this includes bacterivory by protists and nematodes, and the activities of bacterial predators like Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, which invades and lyses other bacterial cells. A special case is parasitism, where one organism (the parasite) benefits at the expense of a host, often without immediate lethal effects [8]. The complex relationship between the Red-billed Oxpecker and large mammals illustrates how a single interaction can have mutualistic, commensalistic, and parasitic components depending on context [8].

Table 1: Core Types of Biotic Interactions in Microbial Ecology

| Interaction Type | Definition | Impact on Species A | Impact on Species B | Microbial Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Both species benefit from the association | + | + | Syntrophic metabolism in anaerobic digesters |

| Competition | Species vie for the same limiting resources | - | - | Quorum sensing-mediated interference competition |

| Predation | One species consumes another | + | - | Bdellovibrio preying on gram-negative bacteria |

| Parasitism | One species benefits by living on or in a host | + | - | Bacteriophage infection and lysis of a bacterial cell |

| Commensalism | One species benefits, the other is unaffected | + | 0 | One species utilizing siderophores produced by another |

Methodologies for Studying Microbial Interactions

Translational research on the microbiome relies on a sophisticated toolkit of culture-independent molecular methods, culture-based techniques, and experimental designs that collectively link microbial community data to ecological functions and host health [9]. The choice of technology is critical; if a bioactivity is driven by a specific microbial strain or transcript, it is unlikely to be identified by low-resolution methods like 16S amplicon sequencing alone [9].

Culture-Independent Molecular Profiling

- 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing: This workhorse method profiles microbial community composition by amplifying and sequencing a phylogenetic marker gene. While cost-effective and sensitive, it is limited to taxonomic profiling (primarily bacteria and archaea), suffers from amplification biases, and generally cannot resolve strains [9]. Newer algorithms like DADA2 and Deblur distinguish biological sequence variants from sequencing error, allowing for strain-level differentiation within the 16S region down to single-nucleotide differences [9].

- Shotgun Metagenomics: This approach sequences the entirety of genomic DNA in a sample, providing a view of the community's functional genetic potential and enabling higher-resolution taxonomic profiling. For strain-level resolution, metagenomic analysis employs:

- Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs): Calling SNVs by mapping sequences to reference genomes (extrinsically) or by comparing sequences across metagenomes (intrinsically) requires deep coverage (typically 10x or more per strain) but offers high precision [9].

- Presence/Absence of Genes: Identifying variable genomic regions, such as gained or lost genes, requires less sequencing depth but is less effective for very closely related strains [9].

- Metatranscriptomics: RNA sequencing reveals the genes actively being transcribed under specific conditions, moving beyond functional potential to actual activity. This requires meticulous sample collection with immediate RNA stabilization and is highly sensitive to technical variability [9]. Data interpretation typically requires a paired metagenome to distinguish changes in transcription from changes in DNA copy number [9].

- Metaproteomics and Metabolomics: These methods characterize the final functional outputs of a community by profiling all proteins or small-molecule metabolites, respectively. They directly identify molecular bioactives but face challenges in compound identification and quantification [9].

Experimental Designs and Perturbation Studies

Controlled manipulation of microbial communities is essential for establishing causal relationships. A key design is the drought intensity experiment on grassland mesocosms, which demonstrated that increasing drought intensity persistently shifts bacterial and fungal community composition, with effects remaining two months after re-wetting [10]. This study also highlighted the role of plant community traits (e.g., leaf dry matter content) as mediators of microbial responses to abiotic stress [10]. Similarly, geographical surveys, such as the analysis of snow microbial communities across Northern China, can disentangle the effects of environmental factors (e.g., NO₃â», COD) and geographic distance on microbial assembly [11]. These studies underscore the need to measure environmental covariates (diet, medications, pollutants) that can confound or mediate the relationship between microbial interactions and host outcomes [9].

Diagram 1: A multiomics workflow for characterizing microbial community interactions, integrating metagenomics and metatranscriptomics.

Quantitative Analysis and Data Integration

The complex, high-dimensional data generated from multiomics studies require specialized computational and statistical approaches to reliably infer biotic interactions and their outcomes.

Inferring Interaction Networks and Dynamics

Microbial interactions are often represented as networks, where nodes represent taxa and edges represent statistically inferred interactions (positive, negative, or neutral). The stability of these co-occurrence networks can be an indicator of community robustness; for example, suburban snow microbiomes were found to have higher network stability than their urban counterparts, suggesting greater resilience to disturbance [11]. For predator-prey dynamics, the Lotka-Volterra model provides a foundational mathematical framework for describing cyclical population fluctuations, though it requires adaptation for multi-species microbial communities [7]. Differential equation-based models are increasingly being combined with machine learning to predict community behavior from compositional data.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Models for Analyzing Biotic Interactions

| Model/Approach | Primary Interaction | Core Formula / Principle | Application in Microbial Ecology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lotka-Volterra | Predation | dN/dt = rN - aNPdP/dt = -sP + bNP [7] | Modeling dynamics of protist bacterivory; phage-host interactions |

| Co-occurrence Network Analysis | All | Correlation (e.g., SparCC, SPIEC-EASI) between taxa across samples [11] | Inferring potential mutualistic (positive edge) or competitive (negative edge) relationships |

| Strain-Level Variant Calling | Competition, Parasitism | Mapping metagenomic reads to reference genomes to identify SNVs [9] | Tracking competitive exclusion or dominance of specific strains within a species |

The Critical Role of Strain-Level Resolution

It is increasingly clear that ecological and functional dynamics are often driven at the strain level. Different strains within a single species can have vastly different genomic content and phenotypic effects. For instance, the pangenome of Escherichia coli contains over 16,000 genes, with fewer than 2000 universal across all strains [9]. This variation has direct consequences for health, as seen in the difference between probiotic E. coli Nissle and uropathogenic E. coli CFT073 [9]. Similarly, specific gene differences in Prevotella copri strains have been correlated with new-onset rheumatoid arthritis [9]. Therefore, analytical pipelines must be capable of resolving this infra-species diversity to accurately link microbial community composition to function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in modern microbial ecology studies for probing biotic interactions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Community Analysis

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Shield | A proprietary reagent that immediately stabilizes microbial community nucleic acids at the point of sample collection, preserving an accurate snapshot of genomic DNA and labile RNA for metatranscriptomics [9]. |

| 16S rRNA PCR Primers | Degenerate oligonucleotide primer sets (e.g., 515F/806R) targeting conserved regions of the 16S rRNA gene for amplification and subsequent sequencing of the hypervariable regions, enabling taxonomic profiling [9]. |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | A widely used commercial kit for preparing multiplexed, sequence-ready libraries from gDNA for shotgun metagenomic sequencing. |

| SOC Medium | A rich bacterial growth medium used for the outgrowth of transformed bacteria following cloning procedures, such as when constructing metagenomic libraries for functional screening. |

| Polycarbonate Membrane Filters | Filters with precise pore sizes (e.g., 0.22 µm) used to concentrate microbial cells from environmental or aqueous samples (e.g., snow meltwater) prior to nucleic acid extraction [11]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | A defined mock community of known bacterial and fungal strains with validated genomic sequences, used as a positive control and for benchmarking the accuracy of wet-lab and bioinformatic protocols. |

| 8,8''-Biskoenigine | 8,8''-Biskoenigine, MF:C38H36N2O6, MW:616.7 g/mol |

| Myricanol triacetate | Myricanol Triacetate |

The systematic dissection of mutualism, competition, and predation within microbial communities is a cornerstone of understanding the factors that govern their composition and function. By employing an integrated strategy that leverages multiomics technologies, controlled perturbations, and sophisticated computational models, researchers can transition from observing patterns to elucidating mechanistic principles. This advanced understanding is a critical prerequisite for the rational manipulation of microbiomes in clinical, agricultural, and industrial settings. For drug development professionals, this opens the door to novel therapeutic strategies, such as leveraging competitive exclusion to displace pathogens or harnessing mutualistic interactions to enhance the resilience and function of probiotic consortia. The future of microbial ecology lies in embracing this complexity, recognizing that the functional units of the microbiome are often specific strains engaged in dynamic, context-dependent interactions.

Host Influence and Compartmentalization in Plant and Animal Microbiomes

The composition of microbial communities, or microbiomes, associated with plant and animal hosts is not random. It is the result of a complex interplay of host-specific factors and ecological processes that lead to distinct microbial assemblages in different host compartments. Understanding host influence—how a host's genetics, physiology, and immune system shape its microbial partners—and compartmentalization—the phenomenon where specific body sites or plant organs select for unique microbial communities—is fundamental to microbial ecology. Framed within the broader thesis of factors influencing microbial community composition, this guide examines the mechanisms by which hosts exert control over their microbiomes and the consequences of this spatial organization for host health, disease, and evolution. Evidence from the Human Microbiome Project has demonstrated that an individual's microbiota are more similar to another individual's microbiota from the same body site than to the microbiota from a different site within the same body, highlighting the power of compartment-specific selective processes [12].

Core Ecological Principles of Microbiome Assembly

The assembly of host-associated microbiomes is governed by four fundamental ecological processes, which provide a framework for understanding observed patterns of composition and compartmentalization [12].

- Dispersal: This refers to the immigration and emigration of microbes from one local habitat to another. Each host is an "island" that draws its microbes from a broader meta-community. The initial colonization of an infant's gut, for instance, is largely determined by dispersal from maternal and environmental sources [12].

- Selection: This deterministic evolutionary force ensures that microbial variants better adapted to a specific host environment (e.g., due to pH, nutrient availability, or host immunity) will outcompete and displace less adapted variants. Selection acts as a "habitat filter," creating the body-site-specific signatures characteristic of compartmentalization [12].

- Drift: Ecological drift describes random fluctuations in microbial abundances due to stochastic birth and death events. This process can be particularly influential in small populations or after a perturbation, such as a course of antibiotics, and can lead to the loss of rare species even if they are well-adapted [12].

- Diversification: This process generates new genetic variation within a microbial population through mutation, recombination, and horizontal gene transfer. The rapid generation times of microbes allow for swift adaptation to selective pressures within a host, such as the evolution of antibiotic resistance [12].

Table 1: Ecological Processes in Microbiome Assembly

| Process | Description | Example in Host-Associated Microbiomes |

|---|---|---|

| Dispersal | Immigration/emigration of microbes between habitats [12]. | Initial neonatal gut colonization from maternal and hospital environment microbes [12]. |

| Selection | Deterministic survival of better-adapted microbial variants [12]. | Body site-specific conditions (e.g., gut anaerobiosis, vaginal acidity) filtering for specific taxa [12]. |

| Drift | Stochastic changes in population size due to random birth/death events [12]. | Loss of low-abundance bacterial species following antibiotic treatment [12]. |

| Diversification | Generation of new genetic variation via mutation or gene transfer [12]. | In-host evolution of Bacteroides fragilis or rapid acquisition of antibiotic resistance genes [12]. |

Host Influence and Compartmentalization in Animal Microbiomes

Mammalian Gastrointestinal Tract

The mammalian gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is a prime example of profound compartmentalization, hosting the body's most abundant and diverse microbiota [12]. This compartmentalization is driven by rostral-caudal gradients in pH, oxygen tension, antimicrobial agents, and bile salts, which create distinct ecological niches from the stomach to the colon. The gut microbiome is not a passive passenger; it plays an active role in host intestinal metabolic processes, including the digestion of complex carbohydrates, production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and regulation of nutrient absorption [13].

A powerful demonstration of host influence comes from a 2025 experimental evolution study in mice, which showed that host behavioral traits can be shaped solely through microbiome selection, independent of host genomic evolution [14]. Researchers performed a one-sided microbiome selection experiment, serially transferring gut microbiomes from donor mice with low locomotor activity into germ-free recipients over four rounds.

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings from Microbiome Selection in Mice [14]

| Experimental Component | Finding | Quantitative / Qualitative Result |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Phenotype Transfer | Locomotor activity (distance traveled) is transmissible via gut microbiome. | Significant difference between recipients of high- vs. low-activity donor microbiomes (Wilcoxon test, uncorrected p = 0.031) [14]. |

| Microbiome Selection | Selection for low-activity microbiome significantly reduced host locomotion. | The selection line, but not the random control line, showed a significant decrease in median distance traveled over 4 rounds of transfer [14]. |

| Key Microbial Driver | Enrichment of Lactobacillus and its metabolite, indolelactic acid, linked to reduced activity. | Administration of Lactobacillus or indolelactic acid alone was sufficient to suppress locomotion in recipient mice [14]. |

| Community Analysis | Donor microbiome differences were partially transferred to recipients. | PERMANOVA analysis confirmed significant difference in recipient microbiomes based on donor origin (F = 15.5, p < 0.001) [14]. |

Detailed Methodology: One-Sided Microbiome Selection Experiment

Objective: To determine if selection on a host behavioral trait (locomotor activity) can shift the host phenotype through microbiome transmission alone, without changes to the host genome [14].

Experimental Workflow:

- Donor Selection: Wild-derived, inbred mouse strains (SAR and MAN lines) exhibiting significant natural variation in locomotor activity were used as initial microbiome donors [14].

- Recipient Conventionalization: Germ-free C57BL/6NTac male mice (3-4 weeks old) were conventionalized via fecal transfer from the donor strains to confirm the microbiome's role in the trait [14].

- Selection Line Setup:

- Selection Line: The two male mice with the least distance traveled after 24h at 5-6 weeks of age were chosen as fecal microbiome donors for the next round of germ-free recipients.

- Control Line: Two mouse donors were selected at random for each round [14].

- Serial Transfer: Microbiomes were serially transferred over four rounds (N0 to N4), with each round lasting two weeks. Recipients were inoculated at 3-4 weeks of age via coprophagy [14].

- Phenotyping and Analysis: Locomotor activity (distance traveled) was measured for all recipients. Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses were performed to identify microbial taxa and metabolites associated with the selected phenotype [14].

Other Body Sites and Local Microenvironments

Compartmentalization extends beyond the gut. The skin, respiratory tract, and reproductive organs all harbor distinct microbial communities shaped by local conditions such as humidity, salinity, temperature, and pH [12]. Recent research also highlights the importance of local tumor microbiomes. Once considered sterile, tumors have been shown to harbor specific microbial communities that can influence the tumor microenvironment, modulate anticancer immunity, and affect responses to therapies like immune checkpoint inhibitors [15]. These intratumoral microbes can originate from the gut (via systemic circulation) or from the local tissue site, creating a unique compartment with significant clinical implications [15].

Host Influence and Compartmentalization in Plant Microbiomes

Plants also host complex microbiomes on their surfaces (phyllosphere) and in the root zone (rhizosphere), with distinct communities compartmentalized to different plant organs. The rhizosphere, in particular, is a hotspot of microbial activity, influenced by root exudates—a complex mixture of carbohydrates, amino acids, and organic acids secreted by plant roots that serve as nutrients and signaling molecules for microbes.

A 2025 multi-laboratory ring trial demonstrated the power of standardized systems to achieve reproducible results in plant microbiome research [16]. The study investigated the assembly of a synthetic microbial community (SynCom) in the rhizosphere of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon grown in sterile EcoFAB 2.0 devices.

Table 3: Key Experimental Findings from a Multi-Lab Plant Microbiome Study [16]

| Experimental Component | Finding | Quantitative / Qualitative Result |

|---|---|---|

| Standardization | Use of standardized habitats (EcoFAB 2.0) and protocols enabled high inter-laboratory reproducibility. | Less than 1% (2/210) of sterility tests showed contamination across five independent labs [16]. |

| Dominant Colonizer | A single bacterial strain, Paraburkholderia sp. OAS925, dominated the root microbiome. | In SynCom17, Paraburkholderia dominated roots with 98 ± 0.03% average relative abundance across all labs [16]. |

| Community Shift | The presence of the dominant colonizer dramatically shifted overall microbiome composition. | Ordination plots showed clear separation between SynCom16 (without Paraburkholderia) and SynCom17 (with Paraburkholderia) [16]. |

| Plant Phenotype | Inoculation with the full SynCom (including Paraburkholderia) caused a consistent decrease in plant shoot biomass. | Significant decrease in shoot fresh and dry weight for SynCom17-inoculated plants relative to axenic controls [16]. |

Detailed Methodology: Reproducible Plant Microbiome Assembly

Objective: To test the reproducibility of synthetic community assembly, plant phenotype, and root exudate composition across five independent laboratories using standardized fabricated ecosystems (EcoFAB 2.0) [16].

Experimental Workflow:

- Standardized Materials: All labs received identical core materials: EcoFAB 2.0 devices, Brachypodium distachyon seeds, and frozen glycerol stocks of the defined 17-member bacterial SynCom (or a 16-member variant lacking Paraburkholderia sp. OAS925) [16].

- Plant Growth and Inoculation:

- Seeds were dehusked, surface-sterilized, stratified, and germinated on agar plates.

- Seedlings were transferred to sterile EcoFAB 2.0 devices and grown for 4 days.

- After a sterility check, plants were inoculated with a defined density of the SynCom (final 1 × 10^5 bacterial cells per plant) [16].

- Monitoring and Sampling: Plants were grown for 22 days after inoculation. Water was refilled, and roots were imaged at multiple timepoints. At harvest, plant biomass was measured, and root/media samples were collected for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and metabolomic analysis [16].

- Centralized Analysis: To minimize analytical variation, all sequencing and metabolomic analyses were performed by a single organizing laboratory [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Microbiome Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Germ-Free (Gnotobiotic) Animals | Enables establishment of causal links between a defined microbiome and a host phenotype in the absence of a confounding resident microbiome [14]. | Used as recipients for fecal microbiome transplants in selection experiments [14]. |

| Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs) | Reduces complexity of natural microbiomes to a defined set of isolates, allowing mechanistic study of community assembly and function [16]. | A 17-member SynCom was used to study reproducible root colonization in plants [16]. |

| Standardized Fabricated Ecosystems (e.g., EcoFAB) | Provides a sterile, controlled habitat for studying host-microbiome interactions under reproducible conditions [16]. | Used in a multi-lab ring trial to study Brachypodium distachyon microbiome assembly [16]. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing | A targeted amplicon sequencing method to identify and quantify the bacterial composition of a microbiome sample [17]. | Profiling of gut or root-associated bacterial communities before and after experimental manipulation [14] [16]. |

| Shotgun Metagenomics | Untargeted sequencing of all microbial DNA in a sample, allowing for taxonomic profiling at higher resolution and functional gene analysis [17]. | Identifying which microbial genes are present in a community and inferring metabolic potential [17]. |

| Metabolomics | Profiling of small-molecule metabolites produced by the host and microbiome, providing a functional readout of microbial activity [17]. | Linking a specific microbial metabolite (e.g., indolelactic acid) to a host phenotype (e.g., reduced locomotion) [14]. |

| Nudaurine | Nudaurine, MF:C19H21NO4, MW:327.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| visamminol-3'-O-glucoside | visamminol-3'-O-glucoside, MF:C21H26O10, MW:438.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Analytical Techniques and Signaling Pathways

Key Analytical Methods

Microbiome research relies on a suite of culture-independent 'omics technologies.

- Marker Gene Analysis (e.g., 16S rRNA, ITS): This is the most common method for characterizing microbial composition. It involves PCR amplification and sequencing of evolutionarily conserved marker genes to assign taxonomy and relative abundance. Data are often processed using bioinformatics pipelines like QIIME, mothur, or DADA2 to group sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) or amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [17].

- Shotgun Metagenomics: This method sequences all DNA in a sample, providing not only taxonomic information but also insights into the functional potential of the microbial community by identifying genes present in the metagenome. Tools like MetaPhlAn2 and Kraken are used for taxonomic binning, while de novo or reference-guided assembly (e.g., with metaSPAdes) allows for gene and pathway annotation [17].

- Metatranscriptomics, Metaproteomics, and Metabolomics: These methods move beyond "who is there" to "what are they doing." Metatranscriptomics sequences total RNA to profile gene expression, metaproteomics identifies and quantifies proteins, and metabolomics profiles the small-molecule metabolites. Together, they provide a multi-layered functional profile of the microbiome [17].

Host-Microbiome Metabolic Signaling Pathways

The gut microbiome exerts a profound influence on host intestinal metabolic processes through the production of metabolites that interact with host signaling pathways [13].

A key mechanism involves microbial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) from fiber fermentation, binding to host G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) like GPCR41 and GPCR43 on enteroendocrine cells (EECs) [13]. This binding triggers the secretion of gut hormones (e.g., incretins) that regulate metabolism and appetite. These metabolites and signaling pathways are crucial for maintaining intestinal barrier integrity, modulating local immune responses, and influencing systemic metabolic health [13]. Disruption of this delicate cross-talk can lead to dysbiosis and contribute to metabolic diseases.

Spatial and Temporal Dynamics in Community Assembly

Microbial community assembly represents a fundamental process in microbial ecology, governing the structure, function, and stability of populations across diverse ecosystems. Understanding the spatial and temporal dynamics of these communities provides crucial insights into ecological resilience, biogeochemical cycling, and host-microbe interactions. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on microbial community assembly processes, focusing specifically on patterns observed across spatial gradients and temporal scales, and explores the implications for scientific research and therapeutic development. The assembly of microbial communities is not random but follows ecological principles that can be distilled into four fundamental processes: selection, dispersal, diversification, and drift [18]. These processes operate simultaneously across multiple scales, creating complex patterns that reflect both deterministic and stochastic forces. Within the context of microbial community composition research, understanding these dynamics enables researchers to predict community responses to environmental change, engineer communities for desired functions, and develop interventions that modulate microbial assemblages for therapeutic benefit.

Theoretical Framework of Community Assembly

The Four Fundamental Processes

Community assembly can be understood through a conceptual framework that distills myriad influencing factors into four core processes [18]:

- Diversification: The generation of new genetic variation through mutation, horizontal gene transfer, and recombination, providing the raw material for community assembly.

- Dispersal: The movement of organisms across space, including immigration and emigration, which determines the pool of potential community members.

- Selection: Deterministic factors related to environmental conditions and biological interactions that favor certain taxa over others, including both abiotic (pH, temperature, nutrients) and biotic (competition, cooperation) factors.

- Drift: Stochastic changes in species abundance due to random birth and death events, which become particularly important in small populations and when selective pressures are weak.

These processes do not operate in isolation but interact in complex ways across spatial and temporal scales to shape community structure [18]. The relative importance of each process varies depending on environmental context, ecosystem type, and the spatial and temporal scale of observation.

Unique Characteristics of Microbial Communities

Microorganisms possess several attributes that distinguish their community assembly processes from those of macroorganisms [18]:

- Enhanced Dispersal Potential: Due to their small size, microbes can disperse passively over great distances via wind, water, and animal vectors, potentially leading to cosmopolitan distributions for some taxa.

- Dormancy Capability: Many microorganisms can enter reversible states of reduced metabolic activity, creating seed banks that can persist under unfavorable conditions and resuscitate when conditions improve.

- Metabolic Plasticity: Microbes exhibit remarkable diversity in their metabolic capabilities, allowing rapid responses to shifting environmental gradients on timescales (hours to days) not attainable by macrobes.

- Rapid Evolution: Short generation times and horizontal gene transfer enable microbial populations to adapt quickly to changing conditions through evolutionary processes.

These unique characteristics mean that microbial community assembly often operates at different temporal and spatial scales compared to plant and animal communities, with implications for studying and interpreting patterns.

Spatial Dynamics in Microbial Community Assembly

Spatial dynamics in microbial communities refer to the variation in community composition across different geographic locations and physical scales. These patterns emerge from the interplay between environmental heterogeneity and microbial dispersal limitations.

Patterns Across Ecosystem Types

Spatial patterns in microbial community composition have been documented across diverse ecosystems, demonstrating consistent relationships with environmental gradients and geographic distance:

Table 1: Spatial Patterns of Microbial Communities Across Different Ecosystems

| Ecosystem | Spatial Pattern | Key Influencing Factors | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban River (Fuhe River) | Significant spatial differences in surface water; Proteobacteria highest in high-nutrient areas, Bacteroidetes higher upstream than downstream | NH₃-N, TN, TP concentrations; heavy metals in sediments | [19] |

| Temperate Stream Network | Headwater streams show high compositional diversity with soil/sediment taxa; downstream increase in freshwater taxa in 3 of 5 seasons | Cumulative upstream dendritic distance; landscape-scale disruptions | [20] |

| Hanford Unconfined Aquifer | Distinct communities at different depths; stronger temporal changes near water table | Hydraulic conductivity; river water intrusion; electron donor/acceptor fluxes | [21] |

Mechanisms Driving Spatial Patterns

The observed spatial patterns in microbial communities are driven by several interconnected mechanisms:

Environmental Filtering: Abiotic conditions such as temperature, pH, nutrient availability, and heavy metal concentrations act as selective filters that determine which taxa can persist in a given location [19]. For example, in the Fuhe River, microbial communities in surface water showed significant spatial differences explained by variations in ammonia nitrogen (NH₃-N), total nitrogen (TN), and total phosphorus (TP) concentrations [19].

Dispersal Limitations: Despite the high dispersal potential of many microorganisms, geographic distance and physical barriers can still limit microbial exchange between habitats. The concept of "everything is everywhere, but the environment selects" requires modification to account for documented dispersal limitations in various ecosystems.

Mass Effects: The influx of microorganisms from connected habitats can influence local community composition. In river systems, microbial communities in headwater streams show higher representation of soil and sediment-associated taxa, while downstream areas are increasingly dominated by freshwater microbial taxa [20].

Temporal Dynamics in Microbial Community Assembly

Temporal dynamics refer to changes in microbial community composition, structure, and function over time, which can occur across scales ranging from diel cycles to seasonal and interannual patterns.

Temporal Patterns Across Ecosystems

Microbial communities exhibit predictable temporal dynamics in response to both regular environmental fluctuations and discrete disturbance events:

Table 2: Temporal Patterns in Microbial Community Composition

| Ecosystem | Temporal Pattern | Key Influencing Factors | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban River (Fuhe River) | Significant seasonal differences in distributions of Cyanobacteria, Actinomycetes, Firmicutes (water) and Actinomycetes, Planctomycetes (sediments) | Temperature; TP concentration; metabolic gene abundances | [19] |

| Temperate Stream Network | Phylotype richness and compositional heterogeneity generally decreased seasonally while freshwater taxa increased; pattern disrupted in 2 of 5 samplings | Temperature; precipitation; watershed-scale disturbances | [20] |

| Hanford Unconfined Aquifer | Strong temporal changes near water table during seasonal river rise; river water intrusion altered community structure | Columbia River stage fluctuation; electron donor/acceptor availability | [21] |

Mechanisms Driving Temporal Patterns

Temporal dynamics in microbial communities are governed by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors:

Seasonal Environmental Variation: Regular seasonal changes in temperature, precipitation, and resource availability drive cyclical shifts in microbial community composition. In the Fuhe River, temperature was identified as a critical factor influencing temporal dynamics, with microbial communities showing distinct seasonal patterns [19].

Successional Processes: Microbial communities often follow predictable successional trajectories after disturbances or during colonization of new habitats. In stream networks, a successional pattern was observed where phylotype richness and compositional heterogeneity decreased while the proportion of known freshwater taxa increased with increasing cumulative upstream dendritic distance [20].

Stochastic Events: Unpredictable disturbance events such as floods, droughts, or nutrient pulses can disrupt established temporal patterns. In the temperate stream network, the expected successional pattern was disrupted in two out of five seasonal samplings, suggesting that external factors can override established temporal dynamics [20].

Biological Interactions: Changes in predator-prey dynamics, competition, and facilitation can drive temporal fluctuations. The Hanford aquifer study noted that temporal dynamics in eukaryotic 18S rRNA gene copies and the dominance of protozoa suggest that bacterial community dynamics could be affected by top-down biological control [21].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Assembly Dynamics

Methodological Framework

Investigating spatial and temporal dynamics in microbial communities requires integrated approaches combining field observations, molecular analyses, and experimental manipulations:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

A comprehensive toolkit is required for investigating microbial community assembly dynamics, encompassing field sampling equipment, molecular biology reagents, and computational resources:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Community Assembly Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | DNA/RNA extraction kits; PBS buffers; preservatives | Isolation of high-quality genetic material from complex samples | Extraction from water, sediments, biofilms for downstream analysis [19] |

| Amplification & Sequencing | 16S/18S rRNA primers; PCR reagents; high-throughput sequencers | Target gene amplification and sequencing for community composition | 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacterial community analysis [19] [21] |

| Quantification | qPCR reagents; standard curves; fluorescent dyes | Absolute quantification of specific taxonomic groups or functional genes | 16S and 18S rRNA gene copy number analyses [21] |

| Bioinformatics | QIIME; Greengenes database; chimerachecking tools | Processing raw sequence data; taxonomic assignment; diversity calculations | Chimera detection and removal in 16S rRNA datasets [21] |

| Statistical Analysis | R packages (vegan, phyloseq); PERMANOVA; null models | Statistical testing of spatial and temporal patterns; multivariate analysis | Testing seasonal and spatial community differences [19] [20] |

Analytical Techniques for Temporal Dynamics

Investigating temporal dynamics requires specialized analytical approaches:

Time-Series Analysis: Statistical methods including autoregressive models, wavelet analysis, and state-space modeling to identify periodic patterns and directional changes in community composition over time.

Rate Measurements: Quantification of community change rates using metrics such as Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, Jaccard distance, or UniFrac distances between consecutive time points.

Trajectory Analysis: Assessment of whether communities follow predictable successional pathways or exhibit alternative stable states through visualization in ordination space.

Environmental Driver Identification: Statistical approaches including Mantel tests, distance-based redundancy analysis, and variance partitioning to quantify the relative importance of different environmental factors in explaining temporal variation.

Engineering Microbial Community Dynamics

Molecular Signaling for Temporal Control

Synthetic biology approaches enable precise manipulation of microbial community dynamics through engineered signaling systems:

Engineering Strategies for Community Control

Several innovative approaches have been developed to engineer temporal dynamics in microbial communities:

Quorum Sensing (QS) Systems: Engineered QS systems enable density-dependent control of gene expression, allowing coordinated behaviors across microbial populations. Inducible QS (iQS) systems combine QS with external inducers for enhanced temporal control [22]. Orthogonal QS systems with minimal cross-talk enable independent control of multiple strains within a community.

Two-Component System (TCS) Engineering: Natural signal transduction pathways can be rewired to create biosensors for specific environmental signals. For example, thiosulfate (ThsSR) and tetrathionate (TtrSR) sensors have been developed to detect inflammation in the mammalian gut [22]. These can be interfaced with synthetic gene circuits for complex signal processing and computation.

Optogenetic Control: Light-responsive systems such as CcaSR enable precise spatiotemporal induction of bacterial functions. This system has been used to induce gut bacteria to produce colanic acid, which increased longevity in a C. elegans model of aging [22].

Temperature-Responsive Circuits: The TlpA repressor from Salmonella typhimurium has been engineered as a temperature-sensitive transcriptional regulation system, allowing control of gene expression using focused ultrasound for heat induction [22].

Electronically Controlled Systems: Redox-responsive genetic circuits using the SoxRS regulon have been engineered to control gene expression using external electronic inputs, enabling population-level bioelectronic communication networks [22].

Implications for Research and Therapeutic Development

Predictive Modeling of Community Dynamics

Computational approaches play an increasingly important role in understanding and predicting microbial community assembly:

Mechanistic Models: Dynamic models that incorporate microbial growth, metabolism, and interactions can predict community assembly under different environmental conditions.

Network Analysis: Inference of interaction networks from temporal data can identify key species and relationships that drive community dynamics.

Machine Learning Approaches: Predictive models trained on high-temporal resolution data can forecast community responses to environmental changes or perturbations.

Therapeutic Applications

Understanding temporal dynamics enables novel therapeutic approaches targeting microbial communities:

Timed Interventions: Knowledge of cyclical dynamics can optimize timing of probiotic administration, antibiotic treatments, or fecal microbiota transplants to enhance efficacy.

Engineered Therapeutics: Synthetic microbial consortia with programmed population dynamics can deliver sustained therapeutic benefits, such as continuous drug production or toxin degradation.

Dysbiosis Correction: Identifying and modifying disrupted temporal dynamics associated with disease states (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease) can help restore healthy community configurations [22].

Environmental and Industrial Applications

Beyond human health, understanding microbial community assembly has broad applications:

Bioremediation: Managing microbial community dynamics to enhance degradation of pollutants in contaminated environments.

Agricultural Management: Optimizing soil microbial communities to support plant health and productivity through understanding of seasonal dynamics.

Industrial Processes: Controlling microbial consortia in biotechnological applications for consistent production of biofuels, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals.

The spatial and temporal dynamics of microbial community assembly represent a complex interplay of ecological processes that operate across multiple scales. The framework of diversification, dispersal, selection, and drift provides a powerful lens for understanding these patterns, while molecular tools and engineering approaches enable unprecedented investigation and manipulation of community dynamics. Future research will increasingly focus on integrating across scales—from molecular mechanisms to ecosystem-level patterns—and developing predictive models that can inform management and engineering of microbial communities for human health, environmental sustainability, and industrial applications. As our understanding of these dynamics deepens, we move closer to the goal of rationally designing and steering microbial communities toward desired functions and stable states.

The Impact of Geographical Isolation and Ecosystem Size

The assembly and function of microbial communities are governed by a complex interplay of ecological and evolutionary processes. Among these, geographical isolation and ecosystem size are two fundamental factors that critically shape microbial diversity, composition, and functional potential. Geographical isolation creates barriers to microbial dispersal, leading to distinct community structures through drift and localized adaptation [23]. Concurrently, ecosystem size influences environmental stability and habitat heterogeneity, thereby modulating the relative influences of deterministic selection and stochastic drift on community assembly [24]. Understanding the synergistic effects of these factors is paramount for predicting microbial responses to environmental change and for harnessing microbial communities in applied contexts such as drug discovery from natural products [25]. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence and provides a technical guide for investigating these dynamics, offering methodologies and analytical frameworks tailored for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Conceptual Framework and Key Principles

The theoretical foundation for understanding how geographical isolation and ecosystem size influence microbial communities draws from both macroecological theory and microbial ecology. The Theory of Island Biogeography, which posits that species richness is governed by the balance between immigration and extinction rates as determined by island size and isolation, provides a robust framework for microbial systems [5] [24]. When applied to microbes, "islands" can represent any isolated habitat, from literal islands to host-associated microbiomes or discrete soil aggregates.

Geographical isolation impacts microbial communities primarily through dispersal limitation. Despite the presumed vast dispersal capabilities of microorganisms, geographical barriers—such as mountain ranges, open ocean, or simply distance—can restrict the movement of microbial taxa, leading to distance-decay relationships where community similarity decreases with increasing geographical distance [23]. This isolation promotes the influence of ecological drift, which is the change in community composition due to stochastic birth-death processes, particularly in smaller populations [24] [23].

Ecosystem size interacts with isolation by modulating environmental conditions. Larger ecosystems typically exhibit greater environmental stability with buffered fluctuations in physicochemical parameters, while smaller ecosystems experience more pronounced environmental fluctuations [24]. This stability gradient influences the relative importance of assembly processes: larger, more stable environments allow for stronger species sorting (deterministic selection by environmental conditions), whereas smaller, fluctuating environments experience regular disruptions to species sorting, giving greater relative importance to drift and dispersal limitation [24]. Furthermore, larger ecosystems often provide greater habitat heterogeneity, supporting higher microbial diversity through niche partitioning.

Table 1: Key Ecological Processes and Their Relationship with Geographical Isolation and Ecosystem Size

| Ecological Process | Definition | Relationship with Geographical Isolation | Relationship with Ecosystem Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dispersal Limitation | Restricted movement of organisms between habitats | Increases with greater isolation | Greater effect in smaller, isolated ecosystems |

| Ecological Drift | Stochastic changes in community composition due to random birth-death events | Stronger influence in more isolated communities | Stronger influence in smaller ecosystems |

| Species Sorting | Deterministic selection by environmental factors | May be masked by dispersal limitation in highly isolated systems | Stronger in larger, more stable ecosystems |

| Habitat Heterogeneity | Spatial variation in environmental conditions | Interacts with isolation to create unique selective pressures | Generally increases with ecosystem size |

Quantitative Evidence and Empirical Data

A growing body of empirical evidence demonstrates the profound effects of geographical isolation and ecosystem size on microbial communities across diverse habitats. The following table synthesizes key findings from recent studies:

Table 2: Empirical Evidence of Geographical Isolation and Ecosystem Size Effects on Microbial Communities

| Ecosystem Type | Geographical Isolation Effect | Ecosystem Size Effect | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese Lakes | Bacterial composition significantly varied across three climatic regions (Northern China, Southern China, Tibetan Plateau); geographical factors dominated at national scale | Sediment communities showed higher α-diversity and stronger distance-decay relationships than water communities | Temperature-driven selection was stronger for water communities, while geographical factors more strongly influenced sediment communities at regional scales | [23] |

| Antarctic Lakes | Microbial communities distinct from temperate freshwater systems; structured by both isolation and local environmental conditions | Environmental gradients (salinity, sulfate, methane, organic carbon) shaped community differences among lakes | Hybrid ASVs ubiquitous in both water and sediment, indicating dispersal processes alongside environmental filtering jointly structure communities | [26] |

| Aquatic Mesocosms | Dispersal limitation varied with mesocosm size and disturbance | Larger mesocosms (200L) more environmentally stable; showed increasing species sorting over time and transient priority effects | Small mesocosms (24.5L) had regular disruptions to species sorting, greater importance of ecological drift and dispersal limitation | [24] |

| Coastal Island Soils | Microbial communities of H. arboreum varied significantly across isolated islands in the South China Sea | Bacterial diversity positively correlated with nutrient availability (N, P); higher in pristine environments like Zhaoshu Island | Fungal diversity more sensitive to human disturbance; Ascomycota dominated but declined in areas with higher human activity | [5] |

| Agricultural Soils | Body size influenced dispersal capability and environmental resistance | Smaller microorganisms had stronger community resistance to environmental changes than larger organisms | Smaller microorganisms had higher diversity, broader niche breadth, and greater metabolic flexibility | [27] |

The quantitative relationships extend to functional attributes. A meta-analysis of litter decomposition studies found that microbial community composition had effects on decay rates rivaling the influence of litter chemistry itself [28]. This structure-function relationship is mediated by ecosystem size and isolation, as smaller, more isolated communities may exhibit reduced functional redundancy due to drift-driven loss of key taxa.

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Field Study Design and Sampling Strategies

For investigating geographical isolation, employ a space-for-time substitution design across multiple isolated habitats (e.g., islands, fragmented landscapes, isolated lakes). Include sampling sites across a gradient of isolation distances and ecosystem sizes [5] [26]. For ecosystem size manipulations, establish mesocosm experiments with varying volumes or areas while controlling for other factors [24].

Sample Collection Protocol:

- Soil/Water Collection: For soil samples, collect from multiple points within each habitat using a sterile corer and composite samples. For water samples, use sterile bottles or filtration systems [26].

- Rhizosphere Sampling: For plant-associated studies, collect the tightly adhering soil fraction (0-0.5 cm) from root surfaces using a soft brush to focus on the root-microbe interface [29].

- Spatial Replication: Collect a minimum of three biological replicates per site/habitat, with each replicate comprising composited material from multiple sub-samples [5] [29].

- Preservation: Immediately freeze samples at -80°C for DNA/RNA work, or preserve in appropriate fixatives for morphological analyses.

Molecular Analyses and Sequencing

DNA Extraction and Amplification:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Use commercial kits optimized for environmental samples (e.g., FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil, PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit) following manufacturer's protocols with modifications for difficult matrices [25] [26].

- Marker Gene Amplification: Amplify the 16S rRNA gene V3-V4 region for bacteria (primers 341F/805R) and ITS region for fungi [5] [26]. Use a minimum of PCR duplicates to control for stochastic amplification.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare libraries using dual indexing strategies to enable multiplexing. Sequence on Illumina platforms (MiSeq, HiSeq) with at least 10,000-50,000 reads per sample after quality control [5] [26].

Metagenomic/Metatranscriptomic Approaches: For functional insights, employ shotgun metagenomic sequencing, which requires greater sequencing depth (typically 5-10 Gb per sample) but provides information on functional genes and metabolic potential [9]. For active community assessment, perform RNA-based metatranscriptomic analyses with prior DNase treatment and cDNA synthesis [9].

Physicochemical Analyses

Concurrent with biological sampling, measure key environmental variables:

- Soil/Water Chemistry: pH, organic matter, total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), available phosphorus (AP), available potassium (AK), ammonium nitrogen (NHâ‚„âº), nitrate nitrogen (NO₃â») [5]

- Additional Parameters: Salinity/conductivity, sulfate, methane, organic carbon, chlorophyll-a, total organic carbon (TOC) [24] [26]

- Spatial Metrics: GPS coordinates, habitat area, distance to nearest similar habitat, connectivity indices

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for studying geographical isolation and ecosystem size effects on microbial communities

Computational and Statistical Approaches

Bioinformatics Processing Pipeline

Process raw sequencing data through established pipelines:

- Quality Filtering: Use DADA2 for amplicon data to infer amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) or KneadData for metagenomic data [24] [26]

- Taxonomic Assignment: Classify sequences against reference databases (SILVA for 16S, UNITE for ITS, RefSeq for metagenomes) [24]

- Functional Profiling: For metagenomic data, use HUMAnN2 or SUPER-FOCUS; for amplicon data, use PICRUSt2 or FUNGuild for functional predictions [9]

Statistical Analyses

Community Analyses:

- Alpha Diversity: Calculate Shannon, Chao1, and Faith's Phylogenetic Diversity indices. Compare across groups using ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis tests [23]

- Beta Diversity: Calculate Bray-Curtis, weighted/unweighted UniFrac distances. Visualize with PCoA or NMDS. Test group differences with PERMANOVA [5] [26]

- Distance-Decay Relationships: Analyze the relationship between geographical distance and community similarity using Mantel tests [23]

Modeling Approaches:

- Variance Partitioning: Quantify the relative contributions of geographical distance, environmental variables, and ecosystem size to community variation [23]

- Path Analysis: Test causal relationships among geographical isolation, ecosystem size, environmental conditions, and community properties [24]

- Neutral Community Models: Estimate the relative importance of stochastic versus deterministic processes [27]

Figure 2: Conceptual diagram of how geographical isolation and ecosystem size affect microbial community assembly and function

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microbial Community Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals) | DNA extraction from diverse environmental samples | Effective for difficult soils; includes inhibitors removal |

| PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio) | Standardized DNA extraction from soils | Widely used for comparative studies; includes bead beating | |

| RNA Preservation | RNAlater Stabilization Solution | RNA preservation for metatranscriptomics | Prevents RNA degradation during sample transport and storage |

| Library Preparation | Illumina Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Amplicon and metagenomic library prep | Enables dual indexing for sample multiplexing |

| Sequencing | Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 | 16S/ITS amplicon sequencing | 2×300 bp chemistry ideal for 16S V3-V4 region |

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S4 Flow Cell | Deep metagenomic sequencing | Enables high coverage for complex communities | |

| Primer Sets | 341F (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) / 805R (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) | Bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplification | Covers V3-V4 region; well-established for microbiota studies |

| ITS1F (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′) / ITS2 (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′) | Fungal ITS region amplification | Specific for fungi; reduces host plant co-amplification | |

| Quality Control | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | DNA quantification | Fluorometric method more accurate for environmental DNA than spectrophotometry |

| Bioinformatics | DADA2 (R package) | Amplicon Sequence Variant inference | Error-correcting algorithm superior to OTU clustering |

| QIIME 2 pipeline | Integrated microbiome analysis | Reproducible workflow from raw sequences to statistical analyses |

The integrated effects of geographical isolation and ecosystem size create predictable patterns in microbial community assembly, with significant implications for ecosystem functioning and potential applications in drug discovery. Future research should focus on multi-omics integration to connect community structure with functional outputs across isolation and size gradients [9] [25]. Additionally, longitudinal studies tracking microbial communities through time will reveal dynamic responses to environmental changes and dispersal events. From an applied perspective, understanding these principles enables better design of microbial cultivation strategies and bioprospecting efforts targeted at unique microbial lineages from isolated, extreme environments that may produce novel bioactive compounds [25]. The methodologies and frameworks presented here provide a foundation for advancing research in microbial ecology and translating these insights into pharmaceutical applications.

Advanced Tools and Models: Profiling, Predicting, and Engineering Microbial Communities

The study of microbial communities has been revolutionized by high-throughput sequencing technologies that allow researchers to investigate microorganisms in their natural environments without the need for cultivation. These omics approaches provide complementary insights into the composition, function, and activity of microbial ecosystems across diverse habitats, from the human body to environmental samples. Understanding the factors influencing microbial community composition requires integrating multiple analytical frameworks that capture different aspects of microbial life. Metagenomics reveals the genetic potential of microbial communities, metatranscriptomics captures actively expressed functions, and single-cell sequencing resolves heterogeneity at the finest biological scale. Together, these technologies form a powerful toolkit for deciphering the complex relationships between microbial community structure, function, and their environmental determinants, enabling advances in human health, environmental science, and biotechnology.

The three omics technologies provide distinct yet complementary insights into microbial communities, each with unique applications, strengths, and limitations.

Metagenomics involves the comprehensive sequencing and analysis of all genetic material (DNA) recovered directly from an environmental sample. This approach enables researchers to profile taxonomic composition and infer the functional potential of microbial communities without prior cultivation [30]. By capturing the collective genome of all microorganisms present, metagenomics can identify both culturable and unculturable microorganisms, providing a extensive view of microbial diversity and genetic capability [30]. Recent advances include genome-resolved long-read sequencing, which has expanded known microbial diversity across terrestrial habitats by enabling recovery of high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from highly complex environments [31].

Metatranscriptomics focuses on sequencing and analyzing the collective RNA content of a microbial community. This approach identifies which genes are actively expressed under specific conditions, providing insights into real-time microbial functions and metabolic activities [32] [33]. Unlike metagenomics which reveals functional potential, metatranscriptomics reveals which metabolic pathways and processes are actually operating, bridging the gap between genetic capability and observable phenotype. This technology has proven valuable for understanding in vivo gene expression in diverse contexts, from human skin and urinary tract infections to soil and aquatic ecosystems [32] [34].

Single-cell sequencing isolates individual microbial cells before sequencing, enabling genomic analysis at the finest possible resolution. This approach bypasses the averaging effect of bulk sequencing methods and allows researchers to explore genetic heterogeneity within microbial populations, identify rare taxa, and analyze uncultured microorganisms [35]. By separating individual cells from complex communities before genomic analysis, this method provides access to genomic information that might be obscured in bulk sequencing approaches, particularly for low-abundance community members.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Microbial Omics Technologies

| Feature | Metagenomics | Metatranscriptomics | Single-Cell Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Target | DNA | RNA | DNA/RNA from individual cells |

| Primary Information | Taxonomic composition, functional potential | Active gene expression, regulatory networks | Genomic heterogeneity, rare taxa, uncultured microbes |

| Key Applications | Community profiling, gene cataloging, biodiversity assessment | Functional activity, metabolic modeling, host-microbe interactions | Strain variation, microdiversity, genome reconstruction |

| Technical Challenges | Host DNA contamination, low microbial biomass, data complexity | RNA stability, low microbial mRNA, rRNA depletion | Cell isolation, amplification bias, cell wall disruption |